Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 89.24.47.157 On Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 89.24.47.157 On Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

Uploaded by

Martin DrlíčekCopyright:

Available Formats

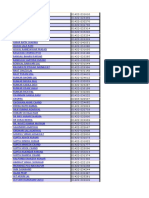

You might also like

- Tim Hortons - Market EntryDocument18 pagesTim Hortons - Market EntryParas KatariaNo ratings yet

- How Soon Is Now? by Carolyn DinshawDocument74 pagesHow Soon Is Now? by Carolyn DinshawDuke University Press100% (1)

- Living Like a Tudor: Woodsmoke and Sage: A Sensory Journey Through Tudor EnglandFrom EverandLiving Like a Tudor: Woodsmoke and Sage: A Sensory Journey Through Tudor EnglandNo ratings yet

- LOVEJOY (1924) On The Discrimination of RomanticismsDocument26 pagesLOVEJOY (1924) On The Discrimination of RomanticismsDaniela Paolini0% (1)

- Gaudio-Counterfeited According To The TruthDocument9 pagesGaudio-Counterfeited According To The TruthPedroHenriquePinheiroGomesNo ratings yet

- Gombrich - Renaissance and Golden AgeDocument5 pagesGombrich - Renaissance and Golden AgeJorge RasnerNo ratings yet

- Hulme, Edward - Symbolism in Christian Art (1891)Document243 pagesHulme, Edward - Symbolism in Christian Art (1891)sqweerty100% (1)

- Marie Delcourt - Hermaphrodite - Myths and Rites of The Bisexual Figure in Classical Antiquity (1961, Studio Books)Document131 pagesMarie Delcourt - Hermaphrodite - Myths and Rites of The Bisexual Figure in Classical Antiquity (1961, Studio Books)vgosenNo ratings yet

- Merchandise Planning: What Is A Six-Month Merchandise Plan?Document7 pagesMerchandise Planning: What Is A Six-Month Merchandise Plan?Varun SharmaNo ratings yet

- Roadworthiness Requirements AUDocument12 pagesRoadworthiness Requirements AUDrey GoNo ratings yet

- Mystery and Morality Plays - The Delphi Edition (Illustrated)From EverandMystery and Morality Plays - The Delphi Edition (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Crébillon, C. P. J. De. The Opportunities of A NightDocument227 pagesCrébillon, C. P. J. De. The Opportunities of A Nightrahojo1029No ratings yet

- Lovejoy - On The Discrimination of RomanticismsDocument26 pagesLovejoy - On The Discrimination of RomanticismsMarija PetrovićNo ratings yet

- Talvacchia, Classical Paradigms and Renaissance Antiquarianism in Giulio Romano's 'I Modi'Document40 pagesTalvacchia, Classical Paradigms and Renaissance Antiquarianism in Giulio Romano's 'I Modi'Claudio CastellettiNo ratings yet

- Greenblatt - Resonance and WonderDocument25 pagesGreenblatt - Resonance and WonderererrreeNo ratings yet

- Richard Stoneman - Greek Mythology PDFDocument196 pagesRichard Stoneman - Greek Mythology PDFEnikő Molnár100% (4)

- Byzantine Women and Their WorldDocument3 pagesByzantine Women and Their Worldsoar8353838No ratings yet

- Jewishcoins00reiniala BWDocument130 pagesJewishcoins00reiniala BWKerr CachaNo ratings yet

- V3006 Aspects of NudityDocument51 pagesV3006 Aspects of NudityClaudio CastellettiNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 193.0.118.39 On Sat, 14 Jan 2023 15:58:40 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 193.0.118.39 On Sat, 14 Jan 2023 15:58:40 UTCKatarzyna KaletaNo ratings yet

- The Warburg InstituteDocument25 pagesThe Warburg Institutecadu_riccioppoNo ratings yet

- Classical Mythology in Medieval ArtDocument54 pagesClassical Mythology in Medieval ArtZhennya SlootskinNo ratings yet

- What Is HistoryDocument5 pagesWhat Is HistoryAbdul NaeemNo ratings yet

- Bagnall - Alexandria: Library of DreamsDocument16 pagesBagnall - Alexandria: Library of DreamsMauro OrtisNo ratings yet

- Cutler A., From Loot To Scholarship, Changing Modes in The Italian Response To Byzantine Artifacts, CA.1200-1750 DOP49Document43 pagesCutler A., From Loot To Scholarship, Changing Modes in The Italian Response To Byzantine Artifacts, CA.1200-1750 DOP49Dina KyriaziNo ratings yet

- WA2.2 Assignment 4Document4 pagesWA2.2 Assignment 4Floor RoeterdinkNo ratings yet

- Memory Palaces and Masonic Lodges: Esoteric Secrets of the Art of MemoryFrom EverandMemory Palaces and Masonic Lodges: Esoteric Secrets of the Art of MemoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Cambridge University Press, British School at Rome Papers of The British School at RomeDocument21 pagesCambridge University Press, British School at Rome Papers of The British School at RomeSafaa SaiedNo ratings yet

- Classic Myths in ArtDocument386 pagesClassic Myths in Artdubiluj100% (3)

- Skrypt Medieval Dramatic FormsDocument10 pagesSkrypt Medieval Dramatic FormsMelania MądrzakNo ratings yet

- LOVEJOY, A. Discriminating RomanticismDocument26 pagesLOVEJOY, A. Discriminating RomanticismHelena MaiaNo ratings yet

- Diogenes and Cynics As A Way of LifeDocument14 pagesDiogenes and Cynics As A Way of LifeJorge Eliécer Guerrero Tarazona100% (1)

- PDF Memory Palaces and Masonic Lodges Esoteric Secrets of The Art of Memory Charles B Jameux Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Memory Palaces and Masonic Lodges Esoteric Secrets of The Art of Memory Charles B Jameux Ebook Full Chapterjessie.rife427100% (4)

- Speaking of WomenDocument20 pagesSpeaking of Womenapi-265406611No ratings yet

- Byzantine Illumination of The Thirteenth CenturyDocument77 pagesByzantine Illumination of The Thirteenth CenturyLenny CarlockNo ratings yet

- Green, Forty Years of Theatre Research, 2000Document20 pagesGreen, Forty Years of Theatre Research, 2000ankaradimaNo ratings yet

- Waite - Lenin in Las MeninasDocument39 pagesWaite - Lenin in Las MeninasKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Ancient Art and Ritual by Harrison, Jane Ellen, 1850-1928Document81 pagesAncient Art and Ritual by Harrison, Jane Ellen, 1850-1928Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Tempest PDFDocument6 pagesThe Tempest PDFBrooke WilsonNo ratings yet

- CIPRIAN IULIAN TOROCZKAI Alexandria at The Beginning of The Fifth Century St. Cyril and His OpponentsDocument13 pagesCIPRIAN IULIAN TOROCZKAI Alexandria at The Beginning of The Fifth Century St. Cyril and His OpponentsIrene GobbiNo ratings yet

- L'Illustration Des Psautiers Grecs Du Moyen Âge, II: Londres, Add. 19.352by Sirarpie Der NersessianDocument4 pagesL'Illustration Des Psautiers Grecs Du Moyen Âge, II: Londres, Add. 19.352by Sirarpie Der Nersessianzxspectrum48kNo ratings yet

- Mango 1963 StatuesDocument29 pagesMango 1963 StatuesSahrian100% (1)

- Černáková The Image of Byzantium in Twelfth-Century French Fiction - FictionDocument29 pagesČernáková The Image of Byzantium in Twelfth-Century French Fiction - Fictioniou12345No ratings yet

- Pace C., ''The Golden Age... The First and Last Days of Mankind. Claude Lorrain and Classical Pastoral, With Special Emphasis On Themes From Ovid's 'Metamorphoses'''Document31 pagesPace C., ''The Golden Age... The First and Last Days of Mankind. Claude Lorrain and Classical Pastoral, With Special Emphasis On Themes From Ovid's 'Metamorphoses'''raistlin majereNo ratings yet

- CuxaDocument36 pagesCuxaa1765No ratings yet

- Fowler - Formation of Genres in The Renaissance and AfterDocument17 pagesFowler - Formation of Genres in The Renaissance and AfterHans Peter Wieser100% (1)

- And Did Those FeetDocument29 pagesAnd Did Those FeetVoislavNo ratings yet

- The Burlington Magazine Publications LTDDocument8 pagesThe Burlington Magazine Publications LTDDravenSwannNo ratings yet

- The Complete Plays of Sophocles (The Seven Plays in English Verse)From EverandThe Complete Plays of Sophocles (The Seven Plays in English Verse)No ratings yet

- Tales From The Enchanted Forest, Introduction PDF, by Deborah Khora, Copyright 2012, Illustrated by Karen Hunziker, Copyright 2012Document19 pagesTales From The Enchanted Forest, Introduction PDF, by Deborah Khora, Copyright 2012, Illustrated by Karen Hunziker, Copyright 2012Deborah KhoraNo ratings yet

- Style and Ideology in Byzantine Imperial ArtDocument16 pagesStyle and Ideology in Byzantine Imperial ArtpeperugaNo ratings yet

- The Medieval Heritage of Elizabethan TragedyFrom EverandThe Medieval Heritage of Elizabethan TragedyRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Mythologies Dictionnaire Des Mythologies Et Des Religions Des Societes Traditionelles Et Dumonde Antique 1981 by Yves Bonnefoy Andwendy DonigerDocument4 pagesMythologies Dictionnaire Des Mythologies Et Des Religions Des Societes Traditionelles Et Dumonde Antique 1981 by Yves Bonnefoy Andwendy DonigerAtmavidya1008No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 80.251.40.39 On Wed, 06 Jan 2021 20:52:25 UTCDocument26 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 80.251.40.39 On Wed, 06 Jan 2021 20:52:25 UTCMina Kevser CandemirNo ratings yet

- Shagun Dissertation Report 2023Document76 pagesShagun Dissertation Report 2023tarun ranaNo ratings yet

- Abia State OneID - Staff Verification SummaryDocument2 pagesAbia State OneID - Staff Verification Summaryuche100% (2)

- HR Om11 Ism ch02Document7 pagesHR Om11 Ism ch02143mc14No ratings yet

- Biometric Service Provider (BSP) : John "Jack" Callahan VeridiumDocument20 pagesBiometric Service Provider (BSP) : John "Jack" Callahan VeridiumSamir BennaniNo ratings yet

- Dilip Kumar Behera-1Document3 pagesDilip Kumar Behera-1dilipbeheraNo ratings yet

- Nokia Deploying 5G Networks White Paper ENDocument16 pagesNokia Deploying 5G Networks White Paper ENIyesusgetanew100% (1)

- Iphone 15 - WikipediaDocument8 pagesIphone 15 - WikipediaaNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The External Environment of The FirmDocument16 pagesAnalyzing The External Environment of The FirmPrecious JirehNo ratings yet

- Corporate Fin. Chapter 10 - Leasing (SLIDE)Document10 pagesCorporate Fin. Chapter 10 - Leasing (SLIDE)nguyenngockhaihoan811No ratings yet

- CV - Ana MeskovskaDocument6 pagesCV - Ana MeskovskaShenka Mustafai0% (1)

- 'AJIRALEO - COM - Field Report - SAMPLEDocument25 pages'AJIRALEO - COM - Field Report - SAMPLEgele100% (1)

- UPDocument178 pagesUPDeepika Darkhorse ProfessionalsNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Capital BudgetingDocument38 pagesCase Study of Capital BudgetingZara Urooj100% (1)

- Shifting Intersections: Fluidity of Gender and Race in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's AmericanahDocument3 pagesShifting Intersections: Fluidity of Gender and Race in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's AmericanahSirley LewisNo ratings yet

- BC Pool Design GuidelinesDocument35 pagesBC Pool Design GuidelinesMohd Zulhairi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- Advisory Circular: U.S. Department of TransportationDocument22 pagesAdvisory Circular: U.S. Department of TransportationlocoboeingNo ratings yet

- 12 - Epstein Barr Virus (EBV)Document20 pages12 - Epstein Barr Virus (EBV)Lusiana T. Sipil UnsulbarNo ratings yet

- Villa Rey Transit Vs FerrerDocument2 pagesVilla Rey Transit Vs FerrerRia Kriselle Francia Pabale100% (2)

- E - L 7 - Risk - Liability in EngineeringDocument45 pagesE - L 7 - Risk - Liability in EngineeringJivan JayNo ratings yet

- Engleski Jezik Seminarski RadDocument11 pagesEngleski Jezik Seminarski RadUna SavićNo ratings yet

- Screenshot 2023-10-27 at 3.46.32 PMDocument60 pagesScreenshot 2023-10-27 at 3.46.32 PMnoordeepkaurmaan01No ratings yet

- Creating Racism: Psychiatry's BetrayalDocument36 pagesCreating Racism: Psychiatry's Betrayalapmendez317No ratings yet

- SRC, Ppsa, LocDocument7 pagesSRC, Ppsa, LocKLNo ratings yet

- Bill Evans Trio PaperDocument5 pagesBill Evans Trio PaperTimothy JohnNo ratings yet

- Censorship: AS Media StudiesDocument9 pagesCensorship: AS Media StudiesBrandonLeeLawrenceNo ratings yet

- Cre Form 1 2020 Schemes of WorkDocument12 pagesCre Form 1 2020 Schemes of Worklydia mutuaNo ratings yet

- A Study of Reasoning Ability of Secondary School Students in Relation To Their IntelligenceDocument3 pagesA Study of Reasoning Ability of Secondary School Students in Relation To Their IntelligenceIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

This Content Downloaded From 89.24.47.157 On Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 89.24.47.157 On Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

Uploaded by

Martin DrlíčekOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 89.24.47.157 On Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 89.24.47.157 On Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

Uploaded by

Martin DrlíčekCopyright:

Available Formats

Pilgrims and Prostitutes: Costume and Identity Construction in Twelfth-Century

Liturgical Drama

Author(s): Andrew J. Gibb

Source: Comparative Drama , Fall 2008, Vol. 42, No. 3, Special Memorial Issue in Memory

of Audrey Ekdahl Davidson (Fall 2008), pp. 359-384

Published by: Comparative Drama

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23038071

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Comparative Drama is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Comparative Drama

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pilgrims and Prostitutes: Costume and

Identity Construction in Twelfth-Century

Liturgical Drama

Andrew J. Gibb

Compiled sometime

Benedictine in the

monastery last quarter of the

at St.-Benoit-sur-Loire, thetwelfth century at the

Fleury Playbook

contains the record of a highly unusual theatrical event.1 It is found in

the Raising of Lazarus, a play that scholars believe may have originated

at Fleury.2 The action begins conventionally enough with Christ and his

disciples dining at the house of Simon. But not long after the play begins,

Mary Magdalen enters the scene "in habitu ... meretricio," or, "costumed

like a streetwalker."3 The dignified Latin of the original text does not

seem to capture fully the shocking quality of the staged performance it

describes, that of a pious cleric entering the church dressed like a prosti

tute. One might reasonably ask what the assembled congregation would

have made of such a spectacle. Or for that matter, what the monk-actors

could have been thinking by presenting it. The mystery deepens when

we consider the monks' peculiar staging choice in the context of the

heretofore established costuming techniques prescribed for liturgical

dramas. For at least two centuries, in tropes such as the visitatio sepulchri,

Mary Magdalen and other female characters had simply been represented

through the artistic draping of priestly vestments near to hand.4 But the

phrase "habitu meretricio" would seem to indicate clothing not likely to

be found in the sacristy, and therein lies the shock value of the didascalia.

But in addition to appearing somewhat bizarre to the modern eye, they

also document a contemporary costuming revolution: they are the first

known examples in medieval theater of a prescribed costume that was

not a liturgical vestment.

359

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

360 Comparative Drama

The monks of Fleury did not restrict their costuming innovation

to Lazarus alone. In another of the Playbooks scripts, Peregrini, a male

character appears "ad modem Peregrini"—in the manner of a pilgrim—an

outfit that includes a tunic, a hat, a staff, and significantly, a leather purse

or wallet.5 Representing a pilgrim with that particular accessory is another

innovation attributable to the monks of St.-Benoit-sur-Loire.6 With its ap

pearance in the didascalia, the mystery of the Fleury costuming practices

grows not only deeper, but darker—for the researcher is confronted with

the intriguing and disturbing fact that, in the long history of medieval

liturgical theater, the first two characters ever represented through secular

costume are a prostitute and a man with a wallet.

Why nonliturgical costuming arose when it did, and why the practice

was inaugurated in such a seemingly unexpected fashion, is the subject

of this essay. The tendency among medieval theater scholars has been to

situate the Fleury plays within a progressivist narrative that charts suc

cessive attempts toward "realism." Dunbar Ogden labels the Fleury inno

vations "realistic touches." Similarly, Theodore Komisarjevsky speaks of

"more realism in the matter of costumes" as the Middle Ages progressed.

Karl Young writes of other plays in which liturgical vestments were

"supplemented by realistic or symbolic objects," and about how in one

case "realism is increased when the angels are provided with wings."7 But

that interpretation attributes modern aesthetic sensibilities to medieval

dramatists and denies the highly symbolic nature of medieval theater. A

desire for realism is not a suitable explanation of a choice by medieval

monks suddenly to incorporate individualized costuming into their the

atrical presentations. Fleury's revolutionary theatrical conventions must

have arisen from conditions and concepts unique to twelfth-century

France. I argue that the Fleury monks' choice to forego universalizing

liturgical vestments in favor of particularized secular garments reflected

a contemporary fascination with identity construction. I further contend

that the characters of the pilgrim and the prostitute served as gendered

role models for contemporary audiences in their construction of new

social identities.

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 361

I. The Twelfth-Century French Renaissance

Twelfth-century Europeans experienced a host of economic and political

changes that generally improved their material conditions, while simul

taneously undermining many of their traditional social arrangements.

A critical development of the period was a significant increase in trade.

Partly driven by the Mediterranean exchange spurred by the Crusades,

the rise in commerce was also facilitated by a greatly strengthened system

of roads.8 Manufacturing became increasingly viable with the expansion

of trade.9 All of those developments contributed to the growth of cities.

At the same time, advances in agriculture led to a lessening of feudal

restrictions on peasants. The result was a more mobile workforce, many

of whom migrated to the new centers of trade and manufacturing.10 The

concentrated wealth of the urban hubs made possible great centers of

learning, where scholars began to mine the wisdom of the ancients and

explore new ways of looking at the world. Primarily due to geography,

twelfth-century France benefited the most from all of those developments.

For that reason, what some historians have labeled "the Renaissance of

the Twelfth Century" is sometimes referred to more specifically as "the

French Renaissance."11

The average twelfth-century Frenchman and Frenchwoman were

thus recent arrivals to the city, were engaged in a new trade, and enjoyed

a surplus of wealth that, no matter how meager, would have staggered

their parents. They were also regularly exposed to the learning of the new

schools through the sermons of preaching clerics.12 As they experienced

both unimagined opportunities and the swift erosion of their traditional

way of life, they doubtless thought a great deal about how they fit into the

new order of things, and how they ought to represent themselves. One

would expect to find evidence of a good deal of such soul-searching in the

artistic and philosophical expressions of the time. And in fact, many liter

ary historians have done so. Colin Morris, for example, argues that twelfth

century Europeans were preoccupied to an unprecedented extent with

explorations of personal identity, a phenomenon he sees as a crucial step

in the development of European Individualism. He is careful to distinguish

between what he calls "political individualism," which arose at a later date

out of concerns about the rights of individuals vis-a-vis their government,

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

362 Comparative Drama

and a twelfth-century individualism that he defines as "self-awareness

and self-expression ... the freedom of man to declare himself without

paying excessive attention to the demands of convention or the dictates

of authority."13 Morris finds evidence of that brand of individualism in a

wide range of twelfth-century artistic and philosophical developments,

including autobiography, private confession, portraits, romances, satire,

and mystical theology. Although he does not directly address theater, his

thesis might easily be applied to that art form. "Individualism" of course

is a famously debatable and debated concept, but fortunately for the

purposes of the present study, no definitive assertions need be made.

Whether or not the social developments of the period were critical to

the rise of Western Individualism, they certainly afforded twelfth-century

Europeans unprecedented freedom in the self-construction of new identi

ties. The particularization of costuming in the Fleury plays can be read as

a dramatic manifestation of a wider twelfth-century preoccupation with

identity construction.

But just why that preoccupation should manifest itself theatrically

through the figures of the pilgrim and the prostitute is a problem that

requires deeper analysis, though one can begin with a consideration of

the same economic conditions that drove the timing of the innovation.

The changes afoot in the twelfth century allowed for an unprecedented

increase in physical and social mobility for Europeans in general, though

some benefited more than others. Those who were positively affected

pursued their newfound mobility in a number of ways, many of which

reflected and reinforced the contemporary interest in the exploration and

expression of personal identity. Two such practices, pilgrimages and con

spicuous fashion displays, are dramatically represented in the Fleury scripts

through the figures of the pilgrim and the prostitute. What is more, the

specific emphases on the pilgrim and the prostitute in the Fleury Playbook

indicate the gendered nature of the twelfth-century's project of identity

construction. Prostitution was an occupation almost solely identified with

women in the Middle Ages.14 By contrast, pilgrimage was largely a male

endeavor.15 The two character types represented dramatic paradigms of

identity construction: the pilgrim specifically male and the prostitute

specifically female. That men should be provided with an ostensibly holy

example and women a seemingly sinful one is a problematic arrangement

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 363

that I will address at length. It is also important to note that, although the

two characters are both manifestations of the same cultural developments,

they never actually meet in the pages of the Fleury Playbook. They inhabit

the same space but never side-by-side, like two faces of a single coin. It

is therefore useful to treat them each more or less individually, before

considering them together.

II. Meretrix

Any understanding of the importance of the Fleury Mary Magdalen

to scenographic history is hampered by the fact that we have no hard

proof of exactly how she was represented onstage. Unlike most medieval

costuming rubrics, which detail the vestimentary items to be used and

specify how they are to be arranged, the Fleury manuscript simply states

"in habitu ... meretricio."16 The lack of elaboration seems to assume that

the reader needs no further description; that anyone will know what a

prostitutes attire should look like. One could assume that the writer does

not imply a familiarity with the appearance of actual prostitutes, but rather

an acquaintance with hagiographic imagery of the pre-conversion Mary.

After all, the Magdalen was one of the most beloved saints of the medieval

period. But as Katherine Ludwig Jansen has pointed out in The Making of

the Magdalen: "Although a popular theme in sermons and sacred drama

of the Middle Ages, and unlike the baroque period, the Magdalen's vani

ties were not well represented in medieval art. In only two Italian fresco

cycles [from the fifteenth century] is her voluptuous pre-conversion life

depicted, and then, with reserve."17 Given such a scarcity of contempo

rary sacred imagery, it would appear that readers and/or audiences of the

Fleury Raising of Lazarus had a more direct knowledge of the appearance

of streetwalkers. And indeed, although the audience at Fleury may well

have found a prostitute an unusual sight within the church, they most

likely would have considered her a familiar one outside of it.18 Historians

of medieval prostitution generally agree that the trade was common in

the twelfth century, and that it was generally, if reluctantly, accepted by

society and the ecclesiastical establishment.19 From the twenty-first

century perspective, conditioned as it is by centuries of state regulation and

religious condemnation of sex work, it may seem strange that the starkly

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

364 Comparative Drama

authoritarian and deeply religious society of medieval Europe should

condone prostitution. And indeed, at no time in the Middle Ages was the

activity celebrated or encouraged; it was always considered a sin and a

disreputable practice. But medieval views of sexuality generally did not

stress the individual responsibility that is such an important component

of today's mores. In the Middle Ages, many people subscribed to what

Ruth Mazo Karras has called the "hydraulic model" of human sexual

ity: the dangers inherent in trying to dam the uncontrollable torrent of

sexuality justified prostitution as a "lesser evil." Without the safety valve

of prostitution, men might be tempted to engage in rape or homosexual

ity.20 In addition to such philosophical imperatives, financial interest on

the part of authorities often played an important role in the acceptance

of prostitution. Many towns during the Middle Ages operated public

brothels, institutions that contributed considerable sums to city treasur

ies. At certain times and places the Church itself, acting in its capacity

as feudal landlord, took in rents from brothels, even as it denounced the

employees of such establishments from the pulpit.21 It should be noted

that no record exists of any such arrangement between the monastery at

St.-Benoit-sur-Loire and the local sex industry. But there is no reason to

believe that the Fleury monks and their lay congregation did not share

the age's ambivalent feelings about prostitution.

Whatever the local realities were, the manner in which Mary's costume

is prescribed is significant. The simple statement of the didascalia, "in

habitu ... meretricio," can be read as evidence that, in the area of twelfth

century St.-Benoit-sur-Loire, prostitutes could easily be identified by their

clothing. The historical record points to two possible explanations of that

apparent uniformity of dress among the regions sex workers. The first is

the presence of a distinctive badge. Modern scholars are probably most

familiar with medieval methods of segregating populations via badges

through the record of contemporary regulations aimed at Jews.22 Jeffrey

Richards has argued that those prescriptions, although not initially aimed

at prostitutes, encouraged a similar use against that group.23 Although

the legal prescription of badges for prostitutes was not common before

the fourteenth century, it is possible that such laws merely codified an

already established practice.24 Jacques Rossiaud has noted that by the

mid-thirteenth century, a red shoulder knot was a common badge in

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 365

French cities. Called the aiguillette, that cord was said to have a biblical

inspiration: it imitated the red rope used by the prostitute Rahab in the

Book of Joshua.25 The common use of such a badge would certainly have

made it easier for the Fleury monks to costume Mary Magdalen. The

actor could have worn the traditional cope and amice combination, and

simply attached the badge. Such a symbol might have sufficiently indicated

meretrix to the audience, without requiring the priest to wear anything

too racy.

A second possibility, potentially of greater interest, is that the costume

was of a much more elaborate nature. Perhaps prostitutes were easily

recognizable through clothing choice rather than a badge. If that was so,

what might such a costume have looked like? Although it is impossible to

know for certain, a contemporary description of French prostitutes can

provide us with some clues. A twelfth-century account, written by the

Arab observer Imad ad-Din, relates the arrival of a group of "Frankish"

prostitutes in the Holy Land. He describes them as "tinted and painted"

and says that "each one trailed the train of her robe behind her."26 An

other contemporary example of the association of a long-trained dress

with prostitution can be found in Richeut, a vernacular poem composed

sometime around 1170. It is frequently cited as an important text in the

development of the fabliau, an often bawdy popular form that took shape

in France during the latter part of the twelfth century.27 The poem re

lates the adventures of its title character, Richeut, a well-to-do prostitute.

In one episode, Richeut takes her illegitimate son to church to see him

christened. The local townsfolk are scandalized, but not so much by her

appearance in a holy place as by the excessively long train of her dress.28

Imad ad-Din's mention of cosmetics is also significant. Although the

Fleury Lazarus makes no specific mention of makeup, another script from

the Playbook indicates a need for pigments of some sort. The Peregrini

calls for Christ to display his wounds. In his discussion of the staging of

that play, Dunbar Ogden conjectures that "no doubt Mary Magdalen uses

such coloring when she appears in the Raising of Lazarus!'29 A number of

later medieval dramas that depict episodes from the Magdalen's life include

scenes in which she purchases beauty products.30 Katherine Ludwig Jansen

points out that the association of Mary with cosmetics was a medieval

innovation, a connection made by churchmen elaborating upon classical

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

366 Comparative Drama

and early church treatises on the sin of vanity, tracts that gendered the

vice as primarily female.31 Cosmetics also appear as an important plot

device in at least one of the episodes of Richeut,32 Such sources point to

the possibility that, far from appearing in a simple cope with a red cord

attached, the priest playing Mary may have entered the church fully rouged

and trailing an extended train. However remarkable that idea may seem,

it is nevertheless the case that the possibility better fits the dating of the

various documents. Imad ad-Din's account is older than, or contemporary

to, the Fleury manuscript, whereas there is no hard evidence for badges

of prostitution dated before the thirteenth century. Evidence of later me

dieval dramatic practice also supports this radical costuming possibility.

Jansen draws our attention to a fifteenth-century ecclesiastical vestment

that depicts Mary in an elaborately draped garment with fantastically

long sleeves. For Jansen, "[t] he theatricality of the scene suggests that its

representation was influenced by sacred plays."33

I have proposed what seem to be the two most likely scenarios for the

costuming of Mary in the Fleury Raising of Lazarus. But both possibili

ties only explain how audience members may have identified a character

as a prostitute through costume. Neither addresses the question of how

or if women viewing the presentation might have constructed their own

identity through the figure of the staged prostitute. At least two signifi

cant medieval discourses about women, one religious and the other legal,

worked to encourage that identification.

The genesis of those discourses can be located in twelfth-century

transformations in the status of women. The economic changes of the

twelfth century that gave rise to urbanization profoundly affected the

lives of women in all classes and occupations. Women were just as likely

to migrate to the cities as their male counterparts. Many came with a

husband or married soon after arriving, and they frequently labored

alongside their spouses. Medieval businesses were generally organized

along family lines, and the wives and daughters of tradesmen were in

many cases valued members of the workforce. The untimely death of a

male proprietor could and did sometimes lead to his wife's inheritance

of the business.34 Wealthy merchants' wives, who did not have to labor as

intensely, benefited from the greater freedom of movement and educa

tion that became possible through the profits from increased trade.35 For

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 367

the poorer classes of women, urbanization generally offered less positive

opportunities. The greatest proportion of city dwellers, men and women

alike, were poor former peasants, caught in a perpetual migration cycle

between the manors and the city slums.36 Many of these desperate souls

were women who chose (or were forced into) prostitution as a means of

breaking the cycle.37

Although the new agency afforded to women by the economic and

demographic changes of the twelfth century was unevenly distributed,

any gain was made at the expense of male hegemonic control. Men gener

ally did not take well to the lessening of their dominance, but they were

constrained to some extent in their retaliation, at least against women of

the nobility or the emerging bourgeoisie. But female prostitutes, doubly

marginalized by their gender and the nature of their work, were fair game.

As a target they symbolized not only female economic power, but also

female sexual independence. Attributing the supposed sins of prostitutes

to womankind in general could and did become an effective method of

ideological control. As Ruth Mazo Karras has written:

It was not only the distrust of money (and hence the fear of feminine venal

ity) that made the prostitute such an important figure in medieval culture's

control of women. It was also her independence. Any woman who was not

under the direct control of a man—any woman who remained single and

earned her own living, or indeed any married woman who earned her own

living as well—was a threat to masculine control.... Labeling some women as

prostitutes was a way of deterring others from undesirable behaviour.38

A prime example of such "undesirable behavior" was the conspicu

ous display of fine clothing. The same economic forces that drove the

geographical and social migration of twelfth-century women exposed

them to previously inaccessible supplies of goods, including a wealth of

fabrics and apparel items. Women in a position to explore and reinvent

their identities could and did choose to express themselves through

clothing. Those who did so most often possessed enough ready cash for

such luxury items. Thus, respectable women of the noble and merchant

classes habitually wore cosmetics and long trains.39 There is consider

able evidence to suggest that men in power were displeased with such

conspicuous demonstrations of increasing female independence and, as

might be expected, churchmen led the way in the ideological response.

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

368 Comparative Drama

Recall the sumptuously attired Magdalen embroidered onto the vestment

of the fifteenth-century cleric as the archetypical image of vanity.40 A

textual example from the same period is the conduct manual titled The

Book of the Knight of La Tour Landry, a collection of stories believed to

have originated in earlier church exempla, or short narratives inserted

into a sermon to illustrate a point.41 The book is full of misogynist tales

about sinful women, a pertinent example being the story of "A Priest's

Vision of His Mother." In that story, a priest is confronted with a vision of

his deceased mother, who is now suffering torment because of her many

earthly sins. She explains the reason for one of the painful tortures she

endures: "my burning skin is drawn off me and trailing behind because

while I lived on earth I wore dresses with excessively long trains."42 The

graphically violent imagery of the piece is common in such clerical at

tacks on medieval female vanity. The exemplum is also typical in that it

links that vanity to female sexuality: the priest s mother also confesses her

"lecherous kissing" and "the two children I bore in adultery."

The preachers' task of associating conspicuous dress with deviant

sexuality was made easier by the well-documented tendency of prosti

tutes to join their social betters in indulgent display. As Nickie Roberts

writes: "A prostitutes earnings often enabled her to adopt the trappings

of a comfortable, middle-class lifestyle; this was a social sin as much as

a sexual one, in the eyes of the scandalized burghers."43 The supposed

difficulty in distinguishing the streetwalker from the society matron was

often cited as an argument for the regulation of the prostitute's dress.44

That regulation often took the form of sumptuary laws. The primary intent

of those legal codes was to discourage conspicuous consumption and to

shore up increasingly blurred class distinctions, but they often included

clauses specifically aimed at legislating the clothing of prostitutes. In

some cases, the laws prescribed badges or specific fabric colors in order

to visually segregate prostitutes. Elsewhere statues denied prostitutes

the right to wear particular items of clothing. Leah Lydia Otis cites a

decree issued by the bailiff of Pezanas in 1320, by which prostitutes were

forbidden to wear "long dresses trailing on the ground."45 But the legal

restrictions placed upon prostitutes also served to define the boundaries

of suitable behavior for the respectable women who were the purported

beneficiaries of the prostitutes' marginalization. Nowhere is that double

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 369

purpose more evident than in the example, cited by James Brundage, of

the city of Perpignan. In that southern French town, civic leaders enacted

a sumptuary code that specifically exempted prostitutes. Such a tactic

was no doubt intended to force respectable women to forgo conspicuous

display, lest they be mistaken for prostitutes.46

Through such negatively inflected discourses as church exempla and

legal codes, both of which associated fine clothing with prostitution, the

male power structure sought to subvert one of the most readily avail

able tools by which women could express their increased social status.

But neither respectable women nor prostitutes were obliged to accept

those negative associations, and the continued appearance of such texts

throughout the Middle Ages indicates that many women refused to do so.

Nevertheless, evidence of women's interiorization of those discourses can

also be cited. The thirteenth-century clergyman Jacques de Vitry wrote

and preached often about proper gender roles and sexual deviance.47 One

of de Vitry's favorite subjects was the life of Marie d'Oignies, a twelfth

century saint who proudly refused to wear hair braids, jewelry, or fashion

able clothing, choosing instead to dress in a hair shirt and simple wool

garments.48 But women disposed to accept the sinfulness of conspicuous

display did not need the example of a contemporary saint. After all, they

already had the premier archetype of redeemed modesty near to hand in

the figure of Mary Magdalen, the first woman to renounce her vanity for

the love of Christ. The status of Mary Magdalen as Christianity's most

representative penitent was growing in the twelfth century, as is testified

to by the increasing number of penitential hymns composed for her feast

day.49 Perhaps because the Magdalen's symbolic power relied upon her

reputation as a past sinner, her specific connection to prostitution was

not downplayed as she rose to prominence, but rather amplified. As the

penitent prostitute Mary came to increasingly dominate the popular

mind, a Pan-European movement arose that was aimed at redeeming sex

workers. Twelfth-century preachers endorsed various redemptive projects,

many of which focused on marrying off prostitutes. In the early thirteenth

century, the high-ranking churchman Rudolph of Worms founded a mo

nastic order that recruited exclusively from among repentant prostitutes.

The Penitent Sisters of Blessed Mary Magdalen received papal approval

in 1227, and soon houses appeared in cities all over Europe, particularly

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

370 Comparative Drama

in France and Germany. The white habits worn by the former prostitutes

became vestmentary symbols of redeemed womanhood.50

It is worth returning to the two possibilities I have advanced for the

costuming of Mary, in order to conjecture how they may have acted upon

female audience members. In the first instance, which I will term the "ai

guillette scenario," women spectators would have been presented with the

traditional costuming of the redeemed Mary in simple cope, but with the

addition of a red cord. The aiguillette was the sign of a very specific sin,

but could also act as a general indication of a sinful state. It could func

tion as a simple yet powerful semiotic device, as all that would separate

Mary from her redeemed self would be the badge. The ease with which

she could remove the badge mirrors the ease with which the twelfth

century Christian woman could remove her sin through confession. It is

no coincidence that, although she is costumed as a prostitute, the audience

sees Mary in her moment of conversion. She rushes onstage, throwing

herself at Christ's feet, begging for forgiveness.51 She thus models through

her actions the behavior of a properly penitent and submissive woman

Through the traditional costume underneath the badge, she would also

model an interior identity as a modest and pious woman, despite the

outward sign of her sin.

The second, or "long-train," scenario models identity much more

ambiguously. The congregation was aware of the details of the story

being presented and knew that they were viewing an impersonation of

a prostitute. In the aiguillette scenario, an idealized vision of a redeemed

Mary is presented; her only mark of shame is the badge that is obviously

not the accessory of a respectable merchant s wife. By contrast, the long

train scenario presents the bourgeoise with a prostitute in her own image.

Mary is represented through exactly those outward signs that most signal

women's newfound social influence, her clothing. And while costume

prompts the female audience member to self-recognition and identifica

tion with the sinning woman, the plot situates Mary at her moment of

redemption. Through this one-two punch, the meaning is conveyed: your

sinful extravagances are Mary's, give them up just as Mary is doing.

In either case, the redeemed (or at least redeemable) Mary was the

model the twelfth-century monks of St.-Benoit-sur-Loire provided to

female parishioners who were fashioning a new identity within a rapidly

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 371

changing society. The choice of a prostitute as an exemplar was critical to

their project, a mission that might almost be described as psychological

warfare. Of course, many medieval women, like their male counterparts,

probably sought exactly such clear-cut instruction from their church. They

may well have identified closely with the Fleury Mary, especially after her

redemption and later appearance at the tomb of Lazarus, by which time her

sinful tresses would surely have been exchanged for more modest ones. In

her dual role of quintessential sinner and archetypal penitent, Mary could

fulfill a wide range of functions for playwrights and spectators alike.

The Raising of Lazarus is not the only text in the Fleury Playbook

that links respectable women with prostitution. The Tres Filice or "Three

Daughters," one of the manuscripts St. Nicholas plays, also makes that

connection. That script, however, does not draw a negative association

through costuming, but offers through plot an almost sympathetic under

standing of the hard economic factors that may have pressured contem

porary women into prostitution. An early mystery play, Tres Filice tells the

story of a recently impoverished man and his three devoted daughters. It

opens with the father's address to his daughters, in which he shares with

them the sad news that he has lost all of his fortune and does not know

how they will survive. His eldest suggests that the daughters support the

family through prostitution; the second argues that to do so would bring

damnation; the third implores her father to trust in the mercy of God.52

They are spared the necessity of endangering their mortal souls when

St. Nicholas makes a timely appearance. What is of particular interest to

this study, however, is not the play's happy ending, but the staging of the

debate. At one level, it is a theological discussion about the pros and cons

of prostitution. At another it is a burgher s nightmare of lost fortune and

respectability. And at yet another level, it speaks to the very real possibili

ties that could have faced members of the Fleury audience. In all three

interpretations, the play dramatizes the uncertainties generated by the

volatile social and economic changes of the day. One can argue that it

also models behavior, especially for the women in the crowd. But if so, the

message is a mixed one, due to an interesting dramaturgical choice. In an

earlier version of the play from Hildesheim, the debate happens exactly

as I have related it, at which point St. Nicholas intervenes to save them

all. That construction tends to favor the response of the third sister, as if

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

372 Comparative Drama

God is rewarding them all for finally arriving at the right decision.53 But

in the Fleury version, the narrative is expanded. The first daughter makes

her suggestion and convinces her father, at which point Saint Nicholas

anonymously tosses money into the house.54 Shortly thereafter a suitor

shows up and marries the first daughter, and the miraculous money must

be used for the dowry, leaving the father and the other two daughters

destitute again. This cycle begins again with the second daughter, and

after that the third. In this fashion, each viewpoint is equally rewarded,

including the first. In the Fleury adaptation, a daughter s offer to enter into

prostitution to save her family is treated as a sacrifice worthy of the saint's

grace. The moral of the story is thus murkier than it is in earlier versions.

The plot of the play encapsulates an understanding of prostitution that is

less dualistic and judgmental than that presented through the costuming

conventions of Lazarus. Although the play probably did not originate at

Fleury, the monks there chose it for adaptation. Its inclusion with the

Raising of Lazarus in the Fleury Playbook not only bears out Karras's

assertion that medieval attitudes about prostitution varied across cities

and time periods, but also demonstrates such variances within a single

place and time.55 Furthermore, the relatively large proportion of scripts

in the Fleury Playbook that feature past or potential prostitutes (two out

of only ten plays) indicates a particular fascination with the ambiguous

figure among the twelfth-century inhabitants of St.-Benoit-sur-Loire.

The Tres Filice is also significant to the present analysis because it

infers the use of money as a prop. Such money imaginatively connects,

on multiple levels, the prostitute represented by the long-trained dress or

red cord with the pilgrim represented by the purse. The first connection

is literal: money is what customers (including erring pilgrims) exchange

for the services of prostitutes. But money also symbolically represents the

accumulated wealth of contemporary Europe that made possible both con

spicuous fashion display and widespread pilgrimage. The new prosperity

that could be measured in part by an increase in available specie was what

enabled the twelfth-century project of identity construction.56 Money lay

at the center of a nexus of possibilities for both men and women, and all

kinds of paths—both good and evil—led from that nexus. Thus money

could bring salvation to a father and his three daughters, as in Tres Filice,

or could tempt a soul into sin, as is the case in another St. Nicholas drama

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 373

from the Fleury Playbook, Tres Clerici. Although that play contains no

prostitute, it does show a woman willing to commit sin for profit. It also

prominently features a pilgrim character.

III. Peregrinus

The plot of Tres Clerici revolves around the three titular scholars, who stop

at an inn for the night. The innkeeper is reluctant to let them stay, but his

wife urges him to do so, and he relents. That night, as the clerks are sleeping,

the innkeeper suggests to his wife that they rob their guests. She not only

agrees, but furthermore advocates killing the young men. No sooner is

that dastardly deed accomplished then St. Nicholas arrives at the door in

the guise of a pilgrim.57 He confronts them with their crime, which they

confess. He then performs a miracle by bringing the scholars back to life,

an act no doubt comforting to future generations of academic readers.58

In this play, as in Tres Filice, the figure of the pilgrim is identified with the

righteous St. Nicholas. The association was a natural one for the monks

of Fleury. As Otto Albrecht has noted, the rise in Nicholas's popularity in

northern Europe during the eleventh century was reflected in the library

at Fleury, which contained a number of works about the saint. A notable

example was the Vita by Johannes Diaconus, upon which several of the

Fleury Nicholas plays were based.59 Additionally, the monastery at St.

Benoit-sur-Loire was intimately familiar with pilgrims, as the abbey was

the repository of the relics of St. Benedict, beloved medieval saint and

foundational figure of Western monasticism. It therefore seems natural

that Fleury s signature plays should revolve around the apparition of

St. Nicholas as a pilgrim. But it is telling that these plays depict the popular

saint engaging in the predominantly male activity of pilgrimage. For in

addition to signifying religious piety, the pilgrim was also an exemplar

of mobility. Temporarily released from his network of social obligations,

the pilgrim's spiritual wandering imaginatively mirrored the search of

twelfth-century European men for new social identities. In choosing to

represent the pilgrim through very particular, nonliturgical costuming,

the monks of Fleury offered male audience members a model of iden

tity construction that fully accounted for the social complexities of the

contemporary age.

This content downloaded from

89.24.47fff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

374 Comparative Drama

By the late twelfth century, pilgrims had become a regular sight

on the roads of medieval Europe. The general accumulation of surplus

wealth not only paid for fine garments, but financed travel of a previously

unimaginable scope. The result was a twelfth-century popular boom in

pilgrimage.60 Pilgrims from all over Europe could finally afford to make

long trips to distant locations. Sites such as Fleury benefited tremendously

from the increased traffic. The shrine of Santiago Compostela on the far

western coast of Spain, together with Rome and the Holy Land, were

medieval Europe's three most significant pilgrim destinations during the

period.61 In each of those places, grand rituals and innumerable ancillary

activities served to mark the highpoint of the pilgrim's journey. But the

distances traversed in the trek to and from the shrine, the wealth of new

experiences along the way, and the considerable time spent away from

home also contributed to the popular interpretation of pilgrimage experi

ence as one of peripatetic movement. That association was so strong that

it entered into the popular and dramatic language of the day. Alan Kendall

has conjectured that the common medieval English name for pilgrims

bound for the Eternal City,"Romers,"is the source of the modern English

verb that implies wandering, "to roam."62 The naming of the Peregrini is

itself a measure of the extent to which medieval society imaginatively

linked journeying with pilgrimage. That liturgical play recounts the ap

pearance of the risen Christ to two of his followers. The source of the

drama is Luke 24:13-35, which begins "Now on that same day [the day

of the Resurrection] two of them were going to a village called Emmaus,

about seven miles from Jerusalem, and they were talking with each other

about all these things that had happened."63 Obviously these men are not

pilgrims. Not only are they unaware of the miraculous birth of their new

religion, they are on the road away from Jerusalem. But to the medieval

mind, this was a story of two men having a religious experience while on

a journey, and thus a story about pilgrims, or peregrini.

As the practice of pilgrimage began to flourish, certain patterns of

standardization were established. Pilgrims guidebooks were composed,

such as the one found in the Liber Sancti Jacobi (1173), which provided

useful information for travelers bound to the great pilgrimage center

at Santiago Compostela.64 Of particular interest to the present study, a

uniform of sorts was developed, which marked the identity of the pilgrim

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 375

through costume. Primary components included a hat and a staff, as well

as a garment of a length short enough to facilitate walking.65 Something

very much like that outfit is indicated by the didascalia of the Fleury Per

egrini. That script begins with the entrance of the two disciples in "tunicis

solummodo et cappis, capuciis absconsis ad modum clamidis, pilleos

in capitibus habentes et baculos in manibus ferentes."66 Ogden loosely

translates the passage as "They wear simple tunics and copes, with felt

or fur hats, and they are carrying staffs; apparently the hoods are hidden

in the form of the chlamys, a cape associated with the peasantry."67 Due

to its institutionalization, contemporary audience members would have

immediately recognized the costume as that of a pilgrim. Male spectators

at St.-Benoit-sur-Loire, many of whom were likely pilgrims themselves,

would have experienced an immediate identification with the actors

before them. After all, they were literally wearing the same outfit. It is in

the Peregrini that the sharp difference between the Fleury modeling of

male and female identity appears most visible. In the case of the prostitute

characters, an uncomfortable identification is affected through costume,

but the discomfort is resolved through the plot, which clearly indicates a

proper path for women to take. The situation is reversed with respect to

the theatrical pilgrims. Male viewers were likely to proudly identify with

the pilgrim characters through a shared costume, but the main dramatic

action of the Peregrini is one of misrecognition: the disciples are on the

road away from Jerusalem when they meet the risen Christ, also in the

garb of a pilgrim, and they initially fail to recognize him. Only after the

Lord reveals himself do they reverse their course. Although the apostles

costumes indicate that they are engaged in a laudable activity, they nev

ertheless require divine guidance in order to set them on the right path.

A parallel misrecognition occurs in the Tres Clerici, when the innkeeper

and his wife are similarly blinded by St. Nicholas's pilgrim attire. In both

plays, a holy figure appears to the world dressed in the garb of a pilgrim.

Thus "pilgrim" and "saint" are equated, and distinctive costume encour

ages a positive male identity construction. But by the same token, the

plotting of the two plays configures the clothing of the pilgrim as a cloak

of disguise. When read against other contemporary discourses about

pilgrimage, the Fleury representations reveal a far more complex process

of identity construction.

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

376 Comparative Drama

The motivations for medieval pilgrimage were as numerous as the

pilgrims themselves. Some undertook the journey as penance, others as an

opportunity to experience sites of divinity and majesty and still others as an

adventure. Some pilgrims were convicted criminals who were compelled to

undertake the journey by local courts, who may have imposed the sentence

with the hope that the malefactor would never return.68 More often than

not, motives were multiple, and thus the figure of the pilgrim denoted piety

while connoting any number of possibilities. As William Melczer writes:

"[the] society of pilgrims consisted of a floating population living, for as

long as the pilgrimage lasted, on the margin of society at large, escaping

its rules by the very mobility and the relative blending of its component

social layers."69 The combination of ready cash and freedom that pilgrim

age entailed was no doubt exhilarating, and most likely did not lend itself

to the mortification of the flesh. Indeed, a whole cottage industry sprung

up around the main routes, one whose existence relied upon the moral

frailty of the pilgrims. Some of the enticements offered were of a relatively

aboveboard nature: a delicious meal or a soft, warm bed for the night. Oth

ers put the pilgrims soul in jeopardy, including prostitution. Prostitutes

were common along the pilgrim routes, some traveling with, and even as,

pilgrims.70 As Sydney Heath has noted: "There is little reason to doubt that

when pilgrimage became the fashion the scrip and staff were as frequently

assumed for the purpose of committing new sins as for the performance

of penance for old ones."71

Evidence that such attitudes about pilgrimage were widespread in

late twelfth-century France can be found in the extremely popular series

of narrative poems collectively titled Roman de Renart, a work begun by

clergyman Pierre de Saint-Cloud in exactly the same time period as the

transcription of the Fleury manuscript. The cycle chronicles the adven

tures of Renard the Fox, an amoral character who tricks his way through

life.72 Renard is sentenced to complete a pilgrimage to Rome for raping

Hersent, the wife of Ysengrin the wolf. Renard sets out, but soon becomes

distracted by the pleasures of the journey:

With staff in hand he is on his way

His long journey has begun.

He acts like a pilgrim and looks like one.

Around his neck hangs a handsome purse.

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 377

But he thinks it foolish to fare worse

Than he has to. If he must atone,

There's no need for doing it all alone.

He left the main road to Rome behind,

And took the first path he could find.73

What follows is a series of adventures, culminating in a hairbreadth

escape for Renard after he once again dupes his archnemesis Ysengrin.

Renard reflects upon his escapades, and decides not to continue with his

journey, for:

Visits to Rome were not required

Of many whose virtue is admired;

Worthy pilgrims, on the other hand,

May turn to sin in the Holy Land.74

Popular poets were not the only ones to question the efficacy of pilgrimage.

Twelfth-century theologian St. Bernard of Clairvaux felt that it would be

better for clergymen to find their spiritual identity at home, forsaking the

tempting road. He summed up his objection to pilgrimage with the phrase

"Your cell is Jerusalem."75 The late twelfth-century bishop of Paris agreed,

and chastised pilgrims for leaving their villages, but not their vices.76

In the light of such contemporary attitudes regarding pilgrimage, a

seemingly unimportant costuming detail from the Peregrini takes on new

significance. The disciples enter the playing space in the readily identifi

able costume of medieval pilgrims. But their uniforms are missing one

crucial symbolic piece, an accessory not seen onstage until Christ enters.

The didascalia describe the Saviors costume:"pera[m] cum longa palma

gestans, bene ad modum Peregrini paratus, pilleum in capite habens, hacla

vestitus et tunica, nudus pedes."77 The passage makes no mention of the

baculo, or staff, and does not indicate a chlamys, though Ogden thinks the

latter is probable as it would "better match his bare feet."78 Christ bears a

palm branch, symbol of the most distinguished pilgrims, "the palmers,"

who had made the journey to the Holy Land.79 But most strikingly, he

wears one item not found among the garments of the disciples: theperam,

translated by Ogden as "wallet" and Young as "purse."80

The peram refers to an accessory that was almost universally worn by

medieval pilgrims.81 Often called the scrip, this item was "a medium-size

sack or bag made usually of deer leather, surprisingly flat and hence of

questionable usefulness for holding food or anything else; normally of

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

378 Comparative Drama

trapezoid shape, it was narrower at the mouth than at the base and, thrown

across the shoulder, it was secured with a leather strap."82 Combined with

the staff, the two items came to define the pilgrim to such an extent that by

the twelfth century, they became central to a church ceremony conducted

at the departure of the wayfarers. In a rite similar to the initiation rituals

of medieval knights, the pilgrims knelt before the altar, presenting their

staff and scrip for blessing by the priest.83 For the pilgrim, the insignia

peregrinorum were the equivalent to the knights sword and shield. The

ritual language of the ceremony spoke of the staff as protection against

the devil and the scrip as a symbol of "the mortifications of the flesh."84

A sermon found in the Liber Sancti Jacobi elaborates on the symbolism

of the scrip. It prescribes that the scrip be small, allowing for very little

money, so that the pilgrim is forced to put his trust in God.85 In short,

the pilgrim is instructed to hit the road with a strong staff and an empty

wallet.

But an empty wallet, no matter how symbolic of poverty, cannot help

but invoke the possibility of its opposite: a full wallet. Indeed, in order to

make it to his final destination, a pilgrim would have had to start with

something very like Renards "handsome purse." Given the often ques

tionable motivations for pilgrimage, one might expect the Fleury monks

to leave out the scrip altogether. But not only did they choose to include

it, they in fact introduced it. Why would they do so? The answer to that

question can be induced from how the monks chose to incorporate their

costuming innovation into the play. As a recognized prop of pilgrimage,

the scrip would help audiences identify with a character who wore it, and

could denote the possibility of self-discovery. But as a sign it could also be

read as a license for debauchery. In the real world, the symbolism of the

script was controlled in part through the spectacular blessing ceremony.

When staged, however, a new tactic was needed to ensure the proper in

terpretation of the scrip. An obvious solution was to associate the symbol

with the most unambiguously holy figure onstage. The didascalia clearly

indicate that it is Christ alone who wears the scrip; the two disciples do

not. Only Christ can be trusted with such a volatile theatrical sign. The plot

of the play also addresses the general instability of the pilgrim costume

as a whole. Christ is first seen wearing the pilgrim's robes as a disguise, a

staging that tends to underline the questionable connotations of pilgrim

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb 379

garb. Following the biblical account, the disciples do not recognize Christ

until he repeats the gestures of the last supper, at which point he vanishes.

When he reappears, he has shed his pilgrim togs.86 Thus the highpoint of

the drama occurs with Christ's revelation of his resurrected, undisguised

self. The pilgrim's hat, cloak, and scrip are shown for the sole purpose of

being superseded, much like Mary's dress.

There is evidence to suggest, however, that pilgrims were not inclined

to lay aside their own garments so easily. Instead of joyfully shedding

the skins of their spiritual metamorphoses, pilgrims were more likely to

treat them as relics. Garments and insignia were carefully preserved, and

on rare occasions taken out and donned for special events. The humble

objects became signs of personal pride. And in the end, just as a knight

was buried with his sword, the pilgrim would be interred with his arms,

the staff and the scrip.87 Of course, such behavior need not be interpreted

as an act of resistance to church ideology, any more than was women's

continued indulgence in the luxury of fine clothing. But it does suggest

differences between clerical and lay interpretations of pilgrimage.

V. Gendering Choice

How twelfth-century Fleury audiences or readers may have interpreted

the Fleury plays is ultimately unknowable, as their responses are not re

corded. The frustration arising from such evidentiary ellipses is common

to theater historians. In this case the absence of evidence about audience

response is particularly vexatious to the modern scholar concerned

with the problematic nature of the gendered equations of "female" with

"prostitute" and "male" with "pilgrim." In the scripts of the Fleury Play

book, it is clear that those equations encapsulated more meanings than

the obvious positive and negative implications. The Raising of Lazarus

and the Tres Filice present prostitution in distinctly different lights, but

both ultimately represent women in the positive act of turning away

from sin and toward redemption. The hallowed costume of the pilgrim

is employed as disguise in the Fleury plays, a usage that echoes contem

porary concerns about the motivations behind pilgrimage. But despite

the complexity of representation, one important distinction between the

Fleury dramatizations of women and men almost always seems to prevail.

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

380 Comparative Drama

Although both the prostitute and the pilgrim serve as complex models

of identity construction for twelfth-century Europeans, a gender divide

is unquestionably apparent in the way that the act of choosing identity

is represented. Men are represented as characters with a choice before

them. But women have always already made their choice, and it is usu

ally the wrong one. Mary Magdalen first appears as a prostitute: she has

fallen long before The Raising of Lazarus ever begins. The only possible

dramatic action for her in the course of the play is to renounce her sinful

ways. The three daughters of the Tres Filice are perhaps afforded more

choice, but the first solution they light upon is the wrong one. For women

spectators, the representations of identity construction are cautionary in

nature. By contrast, the decision-making process of the men is almost

always fully represented, from the presentation of the problem, through

the consideration of various options, to a decision. When that decision is

a wrong one, as is the case with the father of the three daughters or the

innkeeper, divine intervention usually secures the man a second or even

third chance. The differences between the two gendered representations

of the decision-making process no doubt reflect certain realities of the

period. Despite a general expansion of opportunities for all, women still

had fewer choices than men, and the consequences of a wrong decision

were more dire for women. Accordingly, the monks provided women

with models for whom choice was a dangerous act, unless of course that

choice was to submit to male authority, which amounted to no real choice

at all. Of course choosing was not always portrayed as a welcome task for

men, either: witness the agonizing deliberations of the father in Tres Filice.

Nevertheless, the models for men were considerably more complex than

those provided for women.

Despite the clearly unequal power relations apparent in the plotting of

the plays, both the pilgrim and the prostitute supplied the Fleury dramas

with characters for whom choice was dramatically necessary. Ultimately,

that necessity explains the two characters' attraction for a society fascinated

with questions of identity. The choice of the Fleury monks to highlight

those characters through costuming reveals how important clothing is

to the project of identity construction in complex societies. In the eco

nomic milieu of twelfth-century France, the conscious construction and

reconstruction of identity was not only possible but necessary, and every

This content downloaded from

89.24.47.157 on Tue, 09 Nov 2021 12:33:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Andrew J. Gibb >81

day was filled with exciting and frightening choices. The radically new

costuming techniques introduced at Fleury dramatically reflected the

uncertainties of the day. Not only did particularized costumes model pos

sible identities, but those identities were by their very nature changeable:

it is no coincidence that, in addition to the innovation of nonliturgical

costuming, the Fleury Playbook also contains the first known examples

of theatrical costume changes.88

Miami University

NOTES

1 Scholarly uncertainties surround the Fleury document. Only one of its ten scripts, Filiu

Getronis, is definitely known to have been staged, according to Karl Young, The Drama of the Medie

Church, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1933), 2:351. Additionally, there is some controversy ab

Fleury s claim to the manuscript. Fletcher Collins's article "The Home of the Fleury Playbook,"

The Fleury Playbook: Essays and Studies, ed. Thomas P. Campbell and Clifford Davidson (Kalam

zoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1985), 26-34, is an excellent encapsulation of that debate. A

the only other major contender is another French monastery only sixty-five miles away, the ex

provenance of the text is not critical to my analysis of the play's social contexts. I therefore trust in

Collins and tradition and refer to the text throughout as "the Fleury Playbook."

2 Grace Frank identifies four plays as possibly original to Fleury, the Raising of Lazarus an

the three St. Nicholas plays, in The Medieval French Drama (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1954),

Young concurs with Frank regarding Filius Getronis (Young, 2:351), but cites earlier versions of

two other St. Nicholas plays from Hildesheim (2:311,324).

3 This translation is Dunbar Ogden's, from The Staging of Drama in the Medieval Churc

(Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2002), 131. Original text quoted appears in Young (2:200

who more decorously interprets the passage as "the courtesan, Mary Magdalen, appears" (2:208)

4 St. Ethelwold's Regularis Concordia, compiled sometime between 965 and 975, dictat

that the roles of the women in the visitatio sepulchri should be played in a simple cope. Later

matizations of the trope added an amice tied over the head to resemble female headgear (Young

1:249-50, Ogden, 127).

5 The original text of the Fleury Peregrini appears in Young (1:471-75). Ogden interpre

the "peram" of this passage as "wallet" (130), Young as "purse" (1:463). The traditional costumin

practice for pilgrim characters, consisting (like the women) of simple copes creatively draped, w

still being followed at other locations at the time of Fleury s experimentation with accessories

is indicated by a twelfth-century Peregrini from Sicily (Young, 1:459).

6 Ogden gives the honor to the thirteenth-century Peregrini from Rouen, but the Fleury v

sion obviously predates that manuscript (129-130).

7 Ogden, 129; Komisarjevsky, The Costume of the Theatre (New York: Holt, 1932), 56; Young

2:401-2.

8 C. Warren Hollister, Medieval Europe: A Short History, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990),

152; Robert L. Reynolds, Europe Emerges: Transition Toward an Industrial World-Wide Society,