Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Scelsi 4 String Quartet - Halbreich

Scelsi 4 String Quartet - Halbreich

Uploaded by

Angel Arranz MorenoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Scelsi 4 String Quartet - Halbreich

Scelsi 4 String Quartet - Halbreich

Uploaded by

Angel Arranz MorenoCopyright:

Available Formats

Enlace a la grabación con partitura:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QSHSBwUqP-Y

String Quartet No. 4 (1964) Composer: Giacinto Scelsi (1905 - 1988)

Performers: Arditti String Quartet: Irvine Arditti, violin; David Alberman, violin; Levine

Andrade, viola; Rohan de Saram, cello.

__________________________________________________

Barely a year separates the Third Quartet from the Fourth, and yet the latter, composed in

1964, demonstrates a huge step forward. The score's material aspect alone reveals it: this

single movement nine minutes long needs forty-four printed pages, whereas the Second

Quartet's five movements only demand twenty-eight. Indeed, the endlessly increasing

subtleness of the sounds' differentiation leads the composer to treat (and hence to notate) each

string separately, on its own stave. The third part of the great Trilogy for Cello, Ygghur

(1965), Xnoybis for Violin (1964) or Elegia per Ty for Viola and Cello (1966) are other

examples of this creative phase, of which, however, the Fourth Quartet remains the most

extraordinary witness: not at all a quartet in fact, but an "orchestral" composition for sixteen

strings (sometimes notated on thirteen or fourteen staves) where each string is treated as an

instrument with its own colour. Therefore, it is not surprising that Scelsi produced in 1967 a

slightly amplified variant for eleven stringed instruments, Natura Renovatur, which, no

doubt, slightly eases the performers' task, but which does not really surpass the quartet

version in brilliance or richness of tone. For indeed, it seems as if we were listening to a

whole orchestra!

The great form unfolds like a fan, the sounds broadening up until the greatest possible vertical

total before tightening up again. The Golden Section is found at the first fortissimo (bar 143),

sustained from then on until just before the end. Here too, low notes are extremely rare, and

the cello's fourth string is only heard once, at bars 107 to 109 (low E). Here too, the music in

some places recalls a kind of tonality (c-sharp minor from bar 40, d-minor at bar 140's

(Golden Section) great climax, and rather f-minor towards the end). The work begins "on C"

and then follows a great, slowly ascending curve, reaching A at bar 139, without managing to

maintain it for more than an instant. At bar 158, we are back to F. A second rise again reaches

A, first in an unsteady state (219), and quite at the end, in a steady one at last, fading away

into silence.

Scelsi was particularly proud of his Fourth Quartet, and it is indeed a crowning achievement

in his work, as well as in all quartet literature. In the beginning of the seventies, Scelsi's music

reaches an ultimate state of spirituality, with extremely concise pages in which any outer

gesture has become well nigh imperceptible. Now everything happens in materially the most

restricted space, the range being sometimes reduced to a mere interval of a second, but that

which emerges is of extraordinarily concentrated energy. These late works, in fact, witness

the ultimate goal of a creative itinerary pursued without the slightest concession: it is only in a

state of apparent immobility that the energy within the sound rises through implosion to

incandescence! Such "borderline" music, the old master's most radical advance into the next

century, demands a new way of listening, for which an accomplished training in

"contemporary music" is utterly useless, but which lies open to the well-disposed and open-

minded amateur, also receptive in mind and spirit. This is why the musical pundits fear and

hate Scelsi and his music: has he, have they, not broken a secular curse?"

Harry Halbreich

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Bach - Ciaconna From Partita in D Minor - Joaquin Clerch - Tonebase Guitar WorkbookDocument10 pagesBach - Ciaconna From Partita in D Minor - Joaquin Clerch - Tonebase Guitar WorkbookKarol AquilinaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Design Project One: A Music and Microphone Mixer Circuit ObjectiveDocument19 pagesDesign Project One: A Music and Microphone Mixer Circuit ObjectiveAtif khan100% (1)

- Alvamar Overture - 02 C Flute IIDocument4 pagesAlvamar Overture - 02 C Flute IIArwen TurnerNo ratings yet

- 133 590075 0129 COM1 UHF Radio Flight Supplement Chg00Document16 pages133 590075 0129 COM1 UHF Radio Flight Supplement Chg00Henry GoHe DexterNo ratings yet

- Grade 10 Music First Quarter PPT1 SC 2023Document56 pagesGrade 10 Music First Quarter PPT1 SC 2023Kian CamaturaNo ratings yet

- Scales Cheat SheetDocument2 pagesScales Cheat SheetJeffry Lim100% (1)

- Enunciación y Anunciación Del Proyecto IlustradoDocument4 pagesEnunciación y Anunciación Del Proyecto IlustradoMarNo ratings yet

- Melhor de Mim - MarizaDocument1 pageMelhor de Mim - MarizaJoão Pedro OficialNo ratings yet

- Liveschool - Course Information & Syllabus 2020Document18 pagesLiveschool - Course Information & Syllabus 2020Daniel del RíoNo ratings yet

- 2.3 New Total English - Pre-Intermediate (Photocopiables)Document136 pages2.3 New Total English - Pre-Intermediate (Photocopiables)Lize HubnerNo ratings yet

- Project Report OnDocument29 pagesProject Report Onhrithika DhawleNo ratings yet

- Schools Division of Zamboanga Del Norte Ubay National High School Labason Ii DistrictDocument4 pagesSchools Division of Zamboanga Del Norte Ubay National High School Labason Ii DistrictAndevie Balili Iguana100% (1)

- Antenna SpecificationsDocument3 pagesAntenna SpecificationsRobert100% (1)

- Yuvarang 2023 RulebookDocument31 pagesYuvarang 2023 RulebookAshish sawantNo ratings yet

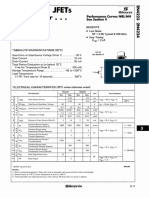

- Designed: JfetsDocument1 pageDesigned: JfetsLuis Carlos OrtegaNo ratings yet

- AgogoDocument3 pagesAgogoAlejo Caveira100% (1)

- Workshop BrochureDocument1 pageWorkshop BrochureRajanikanth ArNo ratings yet

- Solucionario Capitulo 14 Física Serway and FaughnDocument14 pagesSolucionario Capitulo 14 Física Serway and FaughnRafael ColindresNo ratings yet

- MIMO Stadium Antenna: Electrical SpecificationsDocument3 pagesMIMO Stadium Antenna: Electrical SpecificationsСергей МирошниченкоNo ratings yet

- Love Me or Live Me NinaDocument4 pagesLove Me or Live Me Ninaace4castroNo ratings yet

- QST 07 2022Document136 pagesQST 07 2022Sathawit100% (1)

- Posicionamiento de AntenaDocument9 pagesPosicionamiento de AntenaGustavo PradoNo ratings yet

- OutlineDocument1 pageOutlineKOH KIAT HUNG MoeNo ratings yet

- E-Band Trouble Shooting Guide v.07C PDFDocument45 pagesE-Band Trouble Shooting Guide v.07C PDFКурбан УмархановNo ratings yet

- Digital Radio Systems On A Chip - A Systems Approach by Charles ChienDocument534 pagesDigital Radio Systems On A Chip - A Systems Approach by Charles ChienijokyNo ratings yet

- Public Relation VocabularyDocument7 pagesPublic Relation VocabularyKerri-Ann PRINCENo ratings yet

- Self-Invented Notation Systems Created by Young Children: Music Education ResearchDocument15 pagesSelf-Invented Notation Systems Created by Young Children: Music Education ResearchIntan MeeyorNo ratings yet

- Avalon Tab by Mississippi John Hurt - Acoustic Guitar (Nylon) - Songsterr Tabs With Rhythm PDFDocument2 pagesAvalon Tab by Mississippi John Hurt - Acoustic Guitar (Nylon) - Songsterr Tabs With Rhythm PDFTasso SavvopoulosNo ratings yet

- 時間的初衷 周國賢 Endy Chow ToNick FingerstyleDocument3 pages時間的初衷 周國賢 Endy Chow ToNick FingerstyleBrian LiNo ratings yet

- Book ListDocument2 pagesBook ListwernyuhNo ratings yet