Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Money Inflow

Money Inflow

Uploaded by

Abubakr QomorudeenCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Sr. No Name Roll No Programme: Case Analysis Section 2 Toffee Inc. Course: Operations Management (Tod 221)Document6 pagesSr. No Name Roll No Programme: Case Analysis Section 2 Toffee Inc. Course: Operations Management (Tod 221)Harshvardhan Jadwani0% (1)

- DeFi Degens by Abubakr OlawaleDocument3 pagesDeFi Degens by Abubakr OlawaleAbubakr QomorudeenNo ratings yet

- Mgmi PDFDocument40 pagesMgmi PDFDaneshwer VermaNo ratings yet

- A Keynote Address of Dr. Subir Gokarn, Deputy Governor of RBI, During The Plenary Session of Confederation of Indian Industries Summit in 2011Document7 pagesA Keynote Address of Dr. Subir Gokarn, Deputy Governor of RBI, During The Plenary Session of Confederation of Indian Industries Summit in 2011ec_ecNo ratings yet

- Quality of Domestic Financial Market and Capital InflowDocument33 pagesQuality of Domestic Financial Market and Capital InflowEvan OktavianusNo ratings yet

- c4 PDFDocument20 pagesc4 PDFrichardck61No ratings yet

- International Financial Management: The Outlook of The World Through Domestic MarketsDocument49 pagesInternational Financial Management: The Outlook of The World Through Domestic MarketsSuryansh IvaturiNo ratings yet

- Palgrave Macmillan Journals International Monetary FundDocument45 pagesPalgrave Macmillan Journals International Monetary FundRamiro Gimenez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Multinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesMultinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro Solutions Manualdoughnut.synocilj084s100% (28)

- Group 9 FOREX Rate Determination and InterventionDocument37 pagesGroup 9 FOREX Rate Determination and InterventionShean BucayNo ratings yet

- Final Report International Financial System: Group MembersDocument6 pagesFinal Report International Financial System: Group MembersmohsinNo ratings yet

- Er and FD I Article GoldbergDocument7 pagesEr and FD I Article Goldberg0828yyangNo ratings yet

- Currency Rate PresentationDocument8 pagesCurrency Rate PresentationАнастасияNo ratings yet

- Multinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro Solutions ManualDocument24 pagesMultinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro Solutions ManualRobertCookynwk100% (30)

- The Bond Market and Interest RatesDocument3 pagesThe Bond Market and Interest RatesCobie VillenaNo ratings yet

- Case C8Document6 pagesCase C8Việt Tuấn TrịnhNo ratings yet

- M&B Topic 7 Session 2 Wider Aspects of The CrashDocument12 pagesM&B Topic 7 Session 2 Wider Aspects of The CrashdolapoNo ratings yet

- Dissertation - Literature Review and MethodologyDocument20 pagesDissertation - Literature Review and Methodologyshakila segavanNo ratings yet

- DissertationDocument17 pagesDissertationshakila segavanNo ratings yet

- Globalization of Financial MarketsDocument6 pagesGlobalization of Financial MarketsAlinaasirNo ratings yet

- Summary of Managing Volatile Capital Flows: Frederick Emmanuel Susanto 18/426585/EK/21916Document2 pagesSummary of Managing Volatile Capital Flows: Frederick Emmanuel Susanto 18/426585/EK/21916Freed DragsNo ratings yet

- Chapter # 1Document23 pagesChapter # 1Hamza RanaNo ratings yet

- Elucidate The Importance of International Finanace in This Era of GlobalisationDocument15 pagesElucidate The Importance of International Finanace in This Era of GlobalisationAnsariMohammedShoaibNo ratings yet

- Capital Flight in BussinesDocument3 pagesCapital Flight in BussinesFulki NurngaafinaNo ratings yet

- Role of Exchange Rate Markets in An EconomyDocument14 pagesRole of Exchange Rate Markets in An EconomyGohar KhalidNo ratings yet

- Full Download Foundations of Multinational Financial Management 6th Edition Shapiro Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesFull Download Foundations of Multinational Financial Management 6th Edition Shapiro Solutions Manualkyackvicary.n62kje100% (33)

- Dwnload Full Foundations of Multinational Financial Management 6th Edition Shapiro Solutions Manual PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Foundations of Multinational Financial Management 6th Edition Shapiro Solutions Manual PDFbologna.galleon7qhnrf100% (14)

- CH 6 NotesDocument19 pagesCH 6 NotesY SunNo ratings yet

- Random Walk Through Forex MarketsDocument30 pagesRandom Walk Through Forex MarketsJoseph ChukwuemekaNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Multinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro 1118572386 9781118572382Document36 pagesSolution Manual For Multinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro 1118572386 9781118572382christianjenkinsgzwkqyeafc100% (34)

- Q5. Which Is The Best Way To Control Prices/inflation, Which Policy Tool?Document1 pageQ5. Which Is The Best Way To Control Prices/inflation, Which Policy Tool?Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument4 pagesDownloadmanirajpoot45No ratings yet

- Bhasme NotesDocument13 pagesBhasme NotesRutvik DicholkarNo ratings yet

- Financial Crisis and Challenges For The FutureDocument16 pagesFinancial Crisis and Challenges For The FutureMaizatunisak Muhamad SaadNo ratings yet

- Many Shades of GreenbackDocument1 pageMany Shades of GreenbacknaikNo ratings yet

- RBI-An Assessment of Recent Macro Economic DevelopmentsDocument7 pagesRBI-An Assessment of Recent Macro Economic DevelopmentsAshwinkumar PoojaryNo ratings yet

- Libéralisation Du Compte CapitalDocument4 pagesLibéralisation Du Compte Capitalelyka.paintingNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Exchange RateDocument3 pagesFactors Affecting Exchange Rateparthiban25No ratings yet

- Blanchard 2017Document23 pagesBlanchard 2017Gülşah SütçüNo ratings yet

- Raiyan Sadid TP058328 Global FinanceDocument8 pagesRaiyan Sadid TP058328 Global FinanceFariha MaliyatNo ratings yet

- Dampening The Global Risk Appetite Cycle: Using Macro-Prudential ToolsDocument2 pagesDampening The Global Risk Appetite Cycle: Using Macro-Prudential ToolsKannan P NairNo ratings yet

- Currency DevaluationDocument16 pagesCurrency DevaluationTawfeeq Hasan100% (1)

- Liquidity Cascades - Newfound Research PDFDocument19 pagesLiquidity Cascades - Newfound Research PDFrwmortell3580No ratings yet

- Managing Sudden Stops, Eichengreen-Gupta 2016 WBDocument37 pagesManaging Sudden Stops, Eichengreen-Gupta 2016 WBmubbashiraNo ratings yet

- Capital Flows To Emerging MarketsDocument36 pagesCapital Flows To Emerging MarketsaflagsonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 The Economy and Business ActivityDocument29 pagesChapter 10 The Economy and Business ActivityLuis SilvaNo ratings yet

- Weekly Bond Bulletin: Inflation AheadDocument3 pagesWeekly Bond Bulletin: Inflation Aheaddbr trackdNo ratings yet

- IMF - Foreign Investors Under Stress - May 2013Document31 pagesIMF - Foreign Investors Under Stress - May 2013earthanskyfriendsNo ratings yet

- Gente 2015Document27 pagesGente 2015Very BudiyantoNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Multinational Finance 5th Edition Moffett Solutions Manual 1Document36 pagesFundamentals of Multinational Finance 5th Edition Moffett Solutions Manual 1paulwoodpiszdfckxy100% (30)

- Impact of The Currency Exchange RateDocument2 pagesImpact of The Currency Exchange RateLawrence JimenoNo ratings yet

- S02 - CH 2 - Determinants of Interest Rate PDFDocument79 pagesS02 - CH 2 - Determinants of Interest Rate PDFYasser TulbaNo ratings yet

- FDI and Stock Market DeevelopmentDocument52 pagesFDI and Stock Market DeevelopmentWasili MfungweNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rate and Capital Account Management For Developing CountriesDocument10 pagesExchange Rate and Capital Account Management For Developing CountriesJace BezzitNo ratings yet

- C: H T A C S: Ontagion OW HE Sian Risis PreadDocument17 pagesC: H T A C S: Ontagion OW HE Sian Risis PreadrohitkoliNo ratings yet

- International Business The Challenges of Globalization 8th Edition Wild Solutions ManualDocument17 pagesInternational Business The Challenges of Globalization 8th Edition Wild Solutions Manualalanfideliaabxk100% (33)

- International Business The Challenges of Globalization 8Th Edition Wild Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument37 pagesInternational Business The Challenges of Globalization 8Th Edition Wild Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFKathrynBurkexziq100% (14)

- Perspective On Real Interest Rates ImfDocument32 pagesPerspective On Real Interest Rates ImfsuksesNo ratings yet

- 024-article-A005-enDocument21 pages024-article-A005-entrangvnngn0308No ratings yet

- Singapore Property Weekly Issue 208Document17 pagesSingapore Property Weekly Issue 208Propwise.sgNo ratings yet

- International Monetary Financial Economics 1st Edition Daniels Solutions ManualDocument8 pagesInternational Monetary Financial Economics 1st Edition Daniels Solutions Manualhypatiadaisypkm100% (31)

- Financial Markets and Economic Performance: A Model for Effective Decision MakingFrom EverandFinancial Markets and Economic Performance: A Model for Effective Decision MakingNo ratings yet

- cadCAD Modelling ProcessDocument9 pagescadCAD Modelling ProcessAbubakr QomorudeenNo ratings yet

- Alpha HuntDocument4 pagesAlpha HuntAbubakr QomorudeenNo ratings yet

- NFT Terminologies by Abubakr OlawaleDocument3 pagesNFT Terminologies by Abubakr OlawaleAbubakr QomorudeenNo ratings yet

- Duong Thanh Uyen - k204090478 - Acr4.2Document48 pagesDuong Thanh Uyen - k204090478 - Acr4.2Thanh UyênNo ratings yet

- 9AKK105789 EN 06-2018 General Perf PDFDocument52 pages9AKK105789 EN 06-2018 General Perf PDFhari setiawanNo ratings yet

- Ficha Técnica - RPS Tyco ElectronicsDocument2 pagesFicha Técnica - RPS Tyco ElectronicsGalindo FivigaorNo ratings yet

- Assignment in Binomial Distribution PINEDA PLM (ATTEMPT 2)Document2 pagesAssignment in Binomial Distribution PINEDA PLM (ATTEMPT 2)Patrick PinedaNo ratings yet

- Rekonstruksi Pola Perilaku Ekonomi Dan Krisis Pesona Yang Dihadapi Produsen Di Masa Covid-19Document8 pagesRekonstruksi Pola Perilaku Ekonomi Dan Krisis Pesona Yang Dihadapi Produsen Di Masa Covid-19Alda OctaviaNo ratings yet

- Kaushal Parmar 22B3M063Document25 pagesKaushal Parmar 22B3M063Kaushal ParmarNo ratings yet

- MGMT2020 - Revision GuideDocument7 pagesMGMT2020 - Revision GuideChelsea FordeNo ratings yet

- Fake Invoice SSDocument24 pagesFake Invoice SSSUBHASH SHARMANo ratings yet

- Klein - The Life of John Maynard KeynesDocument10 pagesKlein - The Life of John Maynard KeyneseddieNo ratings yet

- Full Download Managerial Economics Foundations of Business Analysis and Strategy 11th Edition Thomas Test BankDocument36 pagesFull Download Managerial Economics Foundations of Business Analysis and Strategy 11th Edition Thomas Test Bankthuyradzavichzuk100% (41)

- Dwnload Full Introductory Mathematical Analysis For Business Economics and The Life and Social Sciences 14th Edition Paul Test Bank PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Introductory Mathematical Analysis For Business Economics and The Life and Social Sciences 14th Edition Paul Test Bank PDFdheybarlowm100% (13)

- Ind Nifty RealtyDocument2 pagesInd Nifty RealtyParth AsnaniNo ratings yet

- An Approach To Determine The Health Index of Power TransformersDocument5 pagesAn Approach To Determine The Health Index of Power Transformersbaby MaNo ratings yet

- FPM1 Dunning - : Read The Document: 313121576-SAP-Collections-and-Disbursement-PDF-1Document20 pagesFPM1 Dunning - : Read The Document: 313121576-SAP-Collections-and-Disbursement-PDF-1HoNo ratings yet

- District Wise Exports of India - 2021Document13 pagesDistrict Wise Exports of India - 2021MNo ratings yet

- SUMMATIVE TEST in Statistics ProbabilityDocument2 pagesSUMMATIVE TEST in Statistics ProbabilitySpade Bun0% (1)

- D6053-Analysis Apprach Source Strategy General Studies Pre Paper I 2021 eDocument109 pagesD6053-Analysis Apprach Source Strategy General Studies Pre Paper I 2021 eSanjog MechuNo ratings yet

- MECH REC69 Magnetic Particle Dye Penetrant ReportDocument1 pageMECH REC69 Magnetic Particle Dye Penetrant ReporttinzarmoeNo ratings yet

- Power Feed-Thru Systems & ConnectorsDocument2 pagesPower Feed-Thru Systems & Connectorsclaudio godinezNo ratings yet

- Hortatory TextDocument2 pagesHortatory TextDaffa MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Working Towards A Better Brazil: National Strategy For Financial Education (Enef)Document164 pagesWorking Towards A Better Brazil: National Strategy For Financial Education (Enef)Carlos NetoNo ratings yet

- TDS TM SYSTEM POLIMAC - Rev. 02 - 20221107Document2 pagesTDS TM SYSTEM POLIMAC - Rev. 02 - 20221107xref akunNo ratings yet

- 46SV2N075T, 200gpm@120ftDocument4 pages46SV2N075T, 200gpm@120ftSajidNo ratings yet

- Instructional Module: Republic of The Philippines Nueva Vizcaya State University Bayombong, Nueva VizcayaDocument7 pagesInstructional Module: Republic of The Philippines Nueva Vizcaya State University Bayombong, Nueva VizcayaDaisy BuwacNo ratings yet

- Naipo MGF-701 Rechargeable Leg Compression MassagerDocument1 pageNaipo MGF-701 Rechargeable Leg Compression MassagerMd Aminul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Exercise IIDocument2 pagesTutorial Exercise IILemma MuletaNo ratings yet

- Floor InletDocument2 pagesFloor Inletmauro zarateNo ratings yet

- BUDGET Part & SERVICE 2024 PLBDocument32 pagesBUDGET Part & SERVICE 2024 PLBService JakartaNo ratings yet

Money Inflow

Money Inflow

Uploaded by

Abubakr QomorudeenCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Money Inflow

Money Inflow

Uploaded by

Abubakr QomorudeenCopyright:

Available Formats

Causes of Capital Inflows and

Policy Responses to Them

N A D E E M U L H AQ U E , D O N A L D M AT H I E S O N , A N D S U N I L S H A R M A

will fuel inflation and drive the real effec- country to country, and policies must be

Some developing and transi- tive exchange rate to unsustainably high tailored to the circumstances of individual

levels. countries.

tion countries are attracting Policymakers faced with the threat of

large inflows of foreign capital overheating in the wake of large capital Identifying the causes

inflows have to make difficult decisions on For the purposes of this article, the

that could destabilize their the magnitude, sequencing, and timing of causes of capital inflows can be grouped

economies. To design policies policy actions. These decisions need to be into three major categories: autonomous

based on the recipient country’s economic increases in the domestic money demand

that will enable them to guard objectives, exchange rate regime, institu- function; increases in the domestic produc-

against this danger, they need tional constraints, and, especially, the tivity of capital; and external factors, such

causes and composition of the inflows. In as falling international interest rates. The

to identify what is driving the

practice, however, it is difficult, at least first two are usually referred to as “pull”

inflows. in the early stages, to identify the causes factors, the third as “push” factors.

and to distinguish between temporary The economic impact of capital inflows

and sustainable inflows. Judgments must and the need, if any, for a policy response

I

N RECENT years, a number of devel- therefore be made on the basis of limited are likely to be determined by the forces

oping and transition countries have information. driving them, as well as by the recipient

enjoyed large inflows of foreign capi- This article sets out a stylized frame- country’s exchange rate regime. Under a

tal that have eased their financing work that addresses two questions. First, fully flexible exchange rate system, capital

constraints. Despite their obvious benefits which financial indicators would be most inflows (regardless of what is driving them)

—increased efficiency and a better alloca- useful to policymakers in identifying the will lead to appreciation of the recipient

tion of capital, and associated transfers of causes of capital inflows? Second, what country’s currency, a drop in the relative

technology—the inflows have aroused con- would the appropriate policy responses be price of imported goods, and a shift of con-

cern because of their potential effects on in different situations? This framework can sumption away from nontradables—all of

macroeconomic stability, the competitive- do no more than provide general guidelines, which tend to alleviate inflationary pres-

ness of the export sector, and external via- however. Capital inflows are determined by sures. Therefore, all other things being

bility. The most serious risks are that they a combination of causes that varies from equal, the more flexible the exchange rate,

Nadeem Ul Haque, Donald Mathieson, Sunil Sharma,

a Pakistani national, is Deputy Chief of the a US national, is Chief of the Emerging Markets an Indian national, is a Senior Economist in the

Monetary and Exchange Policy Analysis Studies Division of the IMF’s Research Emerging Markets Studies Division of the IMF’s

Division in the IMF’s Monetary and Exchange Department. Research Department.

Affairs Department.

Finance & Development / March 1997 3

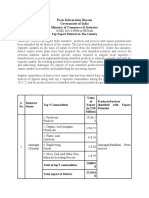

the less likely it is that capital inflows will Table 1

have an inflationary effect. How financial indicators behave can shed light on capital inflows

Under a managed float or a fixed

exchange rate system, whether or not capi- Increase in External factors—e.g.,

tal inflows create inflationary pressures productivity of falling international

Upward shift of domestic capital interest rates

will depend on whether the inflows reflect

Indicator money demand curve (sustained inflows) (temporary inflows)

an upward shift in the money demand func-

tion—that is, an increase in money de- Asset prices

manded for each interest rate level—or are Interest rates Increase Increase Decrease

Yield curve Flattens ? Becomes steeper

due to other factors, such as a drop in inter- Exchange rate Appreciates Appreciates Appreciates

national interest rates or an increase in the Equity prices Decrease Increase Increase

domestic productivity of capital. If capital Real estate prices Decrease Increase Increase

inflows are due primarily to a sustained Inflation Decreases Increases Increases

increase in domestic money demand, they

will not be inflationary. But if they increase Monetary and credit aggregates

Real money balances Increase Likely to decrease Increase

for other reasons, the accumulation of for- Base money Increases Increases Increases

eign exchange reserves will lead, in the International reserves Increase Increase Increase

absence of sterilization, to expansion of the Bank credit Likely to increase Increases Likely to increase

Foreign currency deposits Decrease ? May decrease

monetary base, heightened inflationary

pressures, and deterioration of the external Balance of payments

position. Foreign direct investment ? Increases ?

Financial indicators that may help policy- Portfolio investment Increases, especially Increases, in both Increases,

in short-term flows short- and long- especially in short-

makers differentiate between inflows caused term flows term flows

by a shift in the money demand function

and those driven by exogenous factors ? Indicates that the effect is uncertain.

include asset prices, monetary and credit

aggregates, balance of payments data, and

key international variables, such as interest will tend to put downward pressure on domestic productivity on foreign-currency

rates (Table 1). Data on asset prices, both domestic interest rates. Returns to foreign deposits is ambiguous: a greater need for

domestic and international, are likely to be investors can also provide useful informa- domestic currency will tend to result in

more timely than data on monetary and tion: real returns, which depend on the substitution away from foreign-currency

credit aggregates and the external accounts expected path of the exchange rate (and deposits, while the income effect will work

and, therefore, more useful as indicators in foreign, not domestic, inflation) can be a in the opposite direction.

this context. The usefulness of different key determinant. While the composition of capital inflows

domestic financial indicators depends on an The behavior of real money balances can provide information about their causes,

economy’s institutional structure and on the also may be informative. Capital inflows it is often difficult to distinguish between

sophistication of a country’s data-gathering driven by money demand will be associ- foreign direct investment flows and portfo-

and statistical reporting systems. ated with an increase in money balances lio investment flows, especially in the short

In countries with established financial but not accelerating inflation (and, thus, term. In general, an increase in money

and equity markets, relative asset price with rising real money balances). Capital demand is likely to attract short-term port-

movements may be particularly helpful in inflows generated by a decrease in interna- folio investment, whereas other changes,

identifying causes; it is assumed that there tional interest rates will initially drive up such as an increase in the domestic rate of

is less-than-perfect substitutability be- nominal and real money balances, but then, return on capital, will tend to attract longer-

tween domestic and foreign assets as well as inflation accelerates, real balances may term foreign direct investment. In these

as less-than-perfect capital mobility be- decline. Domestic prices will be slower to cases, also, there may be long delays

tween countries. An upward shift in the respond in low-inflation countries than in between the stimulus and the inflow of cap-

money demand function is likely to drive high-inflation countries. At least initially, ital, depending, among other things, on the

down prices of domestic bonds, equities, capital flows attracted by higher domestic regulatory environment and absorptive

and real estate as asset holders reallocate productivity are likely to take place in an capacity of the recipient country. Thus, an

their portfolios. In contrast, when inflows environment characterized by rising inter- increase in the domestic productivity of

are fueled by lower international interest est rates and domestic income; the net capital may initially lead to larger portfolio

rates or increases in the domestic produc- effect on money demand will depend on the inflows and only later attract greater

tivity of capital, prices of real and financial latter’s sensitivities to changes in interest amounts of foreign direct investment.

assets will probably go up. rates and income. It is probable, however, Although the indicators described above

Interest rates can be useful for determin- that desired holdings of real balances will provide information for guiding policy, two

ing whether capital inflows are caused by be reduced because of higher returns on important caveats apply. First, disentan-

“pull” or by “push” factors. Other things competing assets. gling the factors affecting the various indi-

being equal, inflows driven by “pull” fac- Foreign-currency deposits in the banking cators can be quite complex. Even in the

tors will be associated with upward pres- system should decline when the domestic simplest cases, the indicators often send an

sure on domestic nominal interest rates, money demand function shifts upward and ambiguous message about what is causing

while inflows due to “push” factors, such also, possibly, when international interest the capital inflows, and additional informa-

as a decline in international interest rates, rates fall. However, the effect of increased tion will generally be required. It is there-

4 Finance & Development / March 1997

fore also necessary to consider how broader policies. The ability to sterilize the effects measures—including restrictions on the

changes in economic conditions—for exam- of capital inflows on the monetary base foreign exchange exposure of domestic

ple, economic reforms that increase the pro- may be limited if suitable instruments are financial institutions—could be used to

ductivity of capital and enhance growth not available to the central bank and if limit intermediation of the inflows by the

prospects—may be driving capital inflows. domestic financial markets are not suffi- banking system, as well as to steer foreign

Investment decisions made by market par- ciently developed. It may also be limited capital toward assets with relatively longer

ticipants may also provide useful insights. if previous intervention by the central maturities. Capital controls can be progres-

Moreover, even when the message is clear, it bank has produced a large quasi-fiscal sively dismantled as the quality of surveil-

needs to be evaluated against a counterfac- deficit—the difference between the interest lance improves and the capacity of the

tual—in other words, the behavior of the earned on foreign exchange reserves and banking system to handle flows increases.

indicators has to be interpreted in relation the costs of financing the sterilization. The matrix in Table 2 shows the appro-

to what would have happened if the inflows Although some countries have appropri- priate use of each instrument for countries

had not occurred, although doing this is ately adopted tighter fiscal stances in the with balanced macroeconomic policies. It

very difficult. face of persistent capital inflows, fiscal pol- should be noted that many countries have

icy is somewhat unwieldy for short-term attracted large capital inflows while stabi-

Policy responses demand management because of the lags lization efforts are still in progress—and

The appropriate policy responses will be associated with the formulation and imple- some countries have received capital

determined not only by the causes of capi- mentation of specific measures. And inflows despite poor fundamentals. For the

tal inflows but also by the degree of flexi- exchange rate appreciation may be unac- sake of simplicity, however, the matrix does

bility allowed by the domestic institutional ceptable because it makes a country’s prod- not take into account all possible initial

structure and the existing policy stance. ucts less competitive. conditions and policy imbalances.

Countries that pursue relatively balanced It is sometimes argued that temporary When a capital inflow is associated with

macroeconomic policies have found it eas- capital controls may need to be considered an upward shift in the money demand func-

ier to deal with the disruptions caused by if the use of these three instruments is tion (induced, say, by financial deregula-

inflows than countries with unbalanced severely restricted or their effectiveness is tion), no policy action is required because,

policies (commonly, an excessively expan- limited. However, if capital controls are in in this case, the expansion of the monetary

sionary fiscal policy compensated for by a place for a long time, they tend to become base will not be inflationary or threaten

tight monetary policy). less effective with respect to flows and may external viability. It may be necessary, how-

Some countries can partly offset the hinder the development of the financial sys- ever, for the central bank to intervene in the

upward pressures that large capital inflows tem and undermine the efficiency of (relatively thin) money and foreign ex-

exert on exchange rates by accelerating resource allocation. Moreover, institutional change markets to smooth fluctuations in

the pace of trade and exchange liberaliza- factors can be pivotal in determining what the exchange rate and interest rates. One

tion, including easing controls on capital would be an appropriate response to capital possible cause for concern is that banking

outflows. Otherwise, countries have three inflows. With macroeconomic stabilization credit is likely to expand as money bal-

instruments at their disposal to deal with and deregulation, returns to investment ances increase. With a poorly supervised

the possible effects of large capital inflows: may rise sharply, while the banking system, and weak banking system, the increase in

sterilized intervention, fiscal tightening, which will intermediate the flows, may still commercial banks’ reserves could lead to

and exchange rate appreciation. The opti- have structural weaknesses and poor pru- excessive risk taking in lending activities,

mal mix of instruments depends on the dential supervision. In these circumstances, and measures may be needed to restrict

country’s institutional structure and past capital controls and prudential supervision bank intermediation.

Table 2

Instruments for managing capital inflows

A matrix for countries with balanced macroeconomic policies

Increase in productivity External factors—e.g., falling

Upward shift of domestic of domestic capital international interest rates

money demand curve (sustained inflows) (temporary inflows)

Sterilization May be needed to smooth fluctuations. May be needed to smooth fluctuations. Is appropriate.

Exchange rate appreciation Equilibrium real effective exchange The warranted appreciation of the equilibrium Equilibrium real exchange rate

rate does not change. real effective exchange rate can be achieved need not change. Temporary

partly through nominal appreciation and nominal appreciation of the

partly through increases in the prices of exchange rate may be warranted

nontraded goods. if there are constraints on

sterilization.

Fiscal policy No policy response is required. Fiscal policy tightening is generally required, If the constraints on sterilization

especially if the absorptive capacity of the are too severe and the external

economy is limited relative to the size of the competitive position is weak, then

inflows. some fiscal tightening may have

to be considered.

Finance & Development / March 1997 5

Policymakers need to fashion different large relative to the economy’s absorptive In countries with unbalanced financial

responses depending on whether capital capacity and in countries with pegged policies, short-term inflows are likely to be

inflows are likely to be sustained or tempo- exchange rates. influenced primarily by domestic interest

rary. For a sustained increase—due, say, to To limit the impact of a temporary rates and expected exchange rate move-

an increase in the productivity of domestic increase in capital inflows—for example, ments. Generally, the high domestic interest

capital—policymakers have to decide how one resulting from a decline in international rates that attract foreign capital are due to

best to achieve the appreciation of the interest rates—sterilization of the inflows, a mix of loose fiscal and tight monetary

equilibrium real effective exchange rate. if feasible, is the most appropriate policies; hence, making the appropriate fis-

Adjustments in goods, factor, and asset response, since it can limit or prevent a cal and monetary adjustments to rebalance

prices will ultimately induce a real appreci- deterioration in external competitiveness, the policy mix is clearly the best policy

ation regardless of the exchange rate and some appreciation of the exchange rate response. Reducing interest rates while

regime, and the policy response should not might also be appropriate. However, the decreasing the incentive for speculative

inhibit this appreciation. In economies with ability to sterilize inflows is likely to be lim- inflows, however, could stimulate domestic

flexible exchange rate arrangements, ited and short-lived if the substitutability demand and lead to overheating. In those

appreciation of the real exchange rate can between domestic and international assets situations where a correction of an unbal-

be achieved through a nominal apprecia- is high or the exchange rate is pegged. anced policy mix is expected, the response

tion rather than an inflation of the prices of Adjustments in fiscal policy may not be should be similar to that for a temporary

nontraded goods. Over the medium term, a necessary unless constraints on steriliza- external shock—namely, sterilized inter-

tightening of fiscal policy may be needed tion are severe and the economy’s competi- vention combined with some exchange rate

to control increases in domestic absorp- tive position is weak. Moreover, fiscal appreciation. However, these measures

tion, to prevent an excessive appreciation policy may not be an appropriate instru- would clearly not be effective when funda-

of the real effective exchange rate, and to ment in these cases, because it may involve mental policy adjustments are unlikely to

contain the external deficit. A tighter fiscal lengthy legislative processes, and frequent be forthcoming, especially if high domestic

stance has been necessary in countries con- changes in the tax structure and govern- interest rates are driven by excessive public

fronted with sustained capital inflows, ment spending might impose substantial sector borrowing. F&D

especially when the inflows have been adjustment costs on the economy.

The World Debt Tables hasn’t

disappeared—it’s been renamed!

In Global Development Finance, you’ll find all the information you’re used to seeing in

the World Debt Tables—external debt and financial flows data for 150 countries,

including the 136 that report to the Bank’s Debtor Reporting System. Only the name has

changed for this two-volume annual reference work. Global Development Finance is a

must for economists, bankers, country risk analysts, financial consultants, and anyone

involved in international trade, payments, and capital flows. April 1997. Volume 1:

Stock no. 13788 (ISBN 0-8213-3788-2) $40.00. Two-volume set (Volume 2 not sold

separately): Stock no. 13789 (ISBN 0-8213-3789-0) $300.00.

Global Development Finance is also available on CD-ROM and diskette. View,

select, and extract the data you need through the World Bank’s Socioeconomic Time-series

Access and Retrieval System (*STARS*). Contains data from both volumes and text from Volume 1. Files may be

exported to other databases, Lotus 1-2-3™, or ASCII. CD-ROM individual version: Stock no. 13792 (ISBN 0-8213-3792-0)

$300.00. CD-ROM network version: Stock no. 13793 (ISBN 0-8213-3793-9) $825.00. Diskette individual version: Stock no.

13790 (ISBN 0-8213-3790-4) $200.00. Diskette network version: Stock no. 13791 (ISBN 0-8213-3791-2) $545.00.

The World Bank

PO Box 7247-8619 • Philadelphia, PA 19170-8619 • USA

1240 telephone 202.473.1155 • fax 202.522.2627

6 Finance & Development / March 1997

You might also like

- Sr. No Name Roll No Programme: Case Analysis Section 2 Toffee Inc. Course: Operations Management (Tod 221)Document6 pagesSr. No Name Roll No Programme: Case Analysis Section 2 Toffee Inc. Course: Operations Management (Tod 221)Harshvardhan Jadwani0% (1)

- DeFi Degens by Abubakr OlawaleDocument3 pagesDeFi Degens by Abubakr OlawaleAbubakr QomorudeenNo ratings yet

- Mgmi PDFDocument40 pagesMgmi PDFDaneshwer VermaNo ratings yet

- A Keynote Address of Dr. Subir Gokarn, Deputy Governor of RBI, During The Plenary Session of Confederation of Indian Industries Summit in 2011Document7 pagesA Keynote Address of Dr. Subir Gokarn, Deputy Governor of RBI, During The Plenary Session of Confederation of Indian Industries Summit in 2011ec_ecNo ratings yet

- Quality of Domestic Financial Market and Capital InflowDocument33 pagesQuality of Domestic Financial Market and Capital InflowEvan OktavianusNo ratings yet

- c4 PDFDocument20 pagesc4 PDFrichardck61No ratings yet

- International Financial Management: The Outlook of The World Through Domestic MarketsDocument49 pagesInternational Financial Management: The Outlook of The World Through Domestic MarketsSuryansh IvaturiNo ratings yet

- Palgrave Macmillan Journals International Monetary FundDocument45 pagesPalgrave Macmillan Journals International Monetary FundRamiro Gimenez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Multinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesMultinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro Solutions Manualdoughnut.synocilj084s100% (28)

- Group 9 FOREX Rate Determination and InterventionDocument37 pagesGroup 9 FOREX Rate Determination and InterventionShean BucayNo ratings yet

- Final Report International Financial System: Group MembersDocument6 pagesFinal Report International Financial System: Group MembersmohsinNo ratings yet

- Er and FD I Article GoldbergDocument7 pagesEr and FD I Article Goldberg0828yyangNo ratings yet

- Currency Rate PresentationDocument8 pagesCurrency Rate PresentationАнастасияNo ratings yet

- Multinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro Solutions ManualDocument24 pagesMultinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro Solutions ManualRobertCookynwk100% (30)

- The Bond Market and Interest RatesDocument3 pagesThe Bond Market and Interest RatesCobie VillenaNo ratings yet

- Case C8Document6 pagesCase C8Việt Tuấn TrịnhNo ratings yet

- M&B Topic 7 Session 2 Wider Aspects of The CrashDocument12 pagesM&B Topic 7 Session 2 Wider Aspects of The CrashdolapoNo ratings yet

- Dissertation - Literature Review and MethodologyDocument20 pagesDissertation - Literature Review and Methodologyshakila segavanNo ratings yet

- DissertationDocument17 pagesDissertationshakila segavanNo ratings yet

- Globalization of Financial MarketsDocument6 pagesGlobalization of Financial MarketsAlinaasirNo ratings yet

- Summary of Managing Volatile Capital Flows: Frederick Emmanuel Susanto 18/426585/EK/21916Document2 pagesSummary of Managing Volatile Capital Flows: Frederick Emmanuel Susanto 18/426585/EK/21916Freed DragsNo ratings yet

- Chapter # 1Document23 pagesChapter # 1Hamza RanaNo ratings yet

- Elucidate The Importance of International Finanace in This Era of GlobalisationDocument15 pagesElucidate The Importance of International Finanace in This Era of GlobalisationAnsariMohammedShoaibNo ratings yet

- Capital Flight in BussinesDocument3 pagesCapital Flight in BussinesFulki NurngaafinaNo ratings yet

- Role of Exchange Rate Markets in An EconomyDocument14 pagesRole of Exchange Rate Markets in An EconomyGohar KhalidNo ratings yet

- Full Download Foundations of Multinational Financial Management 6th Edition Shapiro Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesFull Download Foundations of Multinational Financial Management 6th Edition Shapiro Solutions Manualkyackvicary.n62kje100% (33)

- Dwnload Full Foundations of Multinational Financial Management 6th Edition Shapiro Solutions Manual PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Foundations of Multinational Financial Management 6th Edition Shapiro Solutions Manual PDFbologna.galleon7qhnrf100% (14)

- CH 6 NotesDocument19 pagesCH 6 NotesY SunNo ratings yet

- Random Walk Through Forex MarketsDocument30 pagesRandom Walk Through Forex MarketsJoseph ChukwuemekaNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Multinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro 1118572386 9781118572382Document36 pagesSolution Manual For Multinational Financial Management 10th Edition Shapiro 1118572386 9781118572382christianjenkinsgzwkqyeafc100% (34)

- Q5. Which Is The Best Way To Control Prices/inflation, Which Policy Tool?Document1 pageQ5. Which Is The Best Way To Control Prices/inflation, Which Policy Tool?Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument4 pagesDownloadmanirajpoot45No ratings yet

- Bhasme NotesDocument13 pagesBhasme NotesRutvik DicholkarNo ratings yet

- Financial Crisis and Challenges For The FutureDocument16 pagesFinancial Crisis and Challenges For The FutureMaizatunisak Muhamad SaadNo ratings yet

- Many Shades of GreenbackDocument1 pageMany Shades of GreenbacknaikNo ratings yet

- RBI-An Assessment of Recent Macro Economic DevelopmentsDocument7 pagesRBI-An Assessment of Recent Macro Economic DevelopmentsAshwinkumar PoojaryNo ratings yet

- Libéralisation Du Compte CapitalDocument4 pagesLibéralisation Du Compte Capitalelyka.paintingNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Exchange RateDocument3 pagesFactors Affecting Exchange Rateparthiban25No ratings yet

- Blanchard 2017Document23 pagesBlanchard 2017Gülşah SütçüNo ratings yet

- Raiyan Sadid TP058328 Global FinanceDocument8 pagesRaiyan Sadid TP058328 Global FinanceFariha MaliyatNo ratings yet

- Dampening The Global Risk Appetite Cycle: Using Macro-Prudential ToolsDocument2 pagesDampening The Global Risk Appetite Cycle: Using Macro-Prudential ToolsKannan P NairNo ratings yet

- Currency DevaluationDocument16 pagesCurrency DevaluationTawfeeq Hasan100% (1)

- Liquidity Cascades - Newfound Research PDFDocument19 pagesLiquidity Cascades - Newfound Research PDFrwmortell3580No ratings yet

- Managing Sudden Stops, Eichengreen-Gupta 2016 WBDocument37 pagesManaging Sudden Stops, Eichengreen-Gupta 2016 WBmubbashiraNo ratings yet

- Capital Flows To Emerging MarketsDocument36 pagesCapital Flows To Emerging MarketsaflagsonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 The Economy and Business ActivityDocument29 pagesChapter 10 The Economy and Business ActivityLuis SilvaNo ratings yet

- Weekly Bond Bulletin: Inflation AheadDocument3 pagesWeekly Bond Bulletin: Inflation Aheaddbr trackdNo ratings yet

- IMF - Foreign Investors Under Stress - May 2013Document31 pagesIMF - Foreign Investors Under Stress - May 2013earthanskyfriendsNo ratings yet

- Gente 2015Document27 pagesGente 2015Very BudiyantoNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Multinational Finance 5th Edition Moffett Solutions Manual 1Document36 pagesFundamentals of Multinational Finance 5th Edition Moffett Solutions Manual 1paulwoodpiszdfckxy100% (30)

- Impact of The Currency Exchange RateDocument2 pagesImpact of The Currency Exchange RateLawrence JimenoNo ratings yet

- S02 - CH 2 - Determinants of Interest Rate PDFDocument79 pagesS02 - CH 2 - Determinants of Interest Rate PDFYasser TulbaNo ratings yet

- FDI and Stock Market DeevelopmentDocument52 pagesFDI and Stock Market DeevelopmentWasili MfungweNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rate and Capital Account Management For Developing CountriesDocument10 pagesExchange Rate and Capital Account Management For Developing CountriesJace BezzitNo ratings yet

- C: H T A C S: Ontagion OW HE Sian Risis PreadDocument17 pagesC: H T A C S: Ontagion OW HE Sian Risis PreadrohitkoliNo ratings yet

- International Business The Challenges of Globalization 8th Edition Wild Solutions ManualDocument17 pagesInternational Business The Challenges of Globalization 8th Edition Wild Solutions Manualalanfideliaabxk100% (33)

- International Business The Challenges of Globalization 8Th Edition Wild Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument37 pagesInternational Business The Challenges of Globalization 8Th Edition Wild Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFKathrynBurkexziq100% (14)

- Perspective On Real Interest Rates ImfDocument32 pagesPerspective On Real Interest Rates ImfsuksesNo ratings yet

- 024-article-A005-enDocument21 pages024-article-A005-entrangvnngn0308No ratings yet

- Singapore Property Weekly Issue 208Document17 pagesSingapore Property Weekly Issue 208Propwise.sgNo ratings yet

- International Monetary Financial Economics 1st Edition Daniels Solutions ManualDocument8 pagesInternational Monetary Financial Economics 1st Edition Daniels Solutions Manualhypatiadaisypkm100% (31)

- Financial Markets and Economic Performance: A Model for Effective Decision MakingFrom EverandFinancial Markets and Economic Performance: A Model for Effective Decision MakingNo ratings yet

- cadCAD Modelling ProcessDocument9 pagescadCAD Modelling ProcessAbubakr QomorudeenNo ratings yet

- Alpha HuntDocument4 pagesAlpha HuntAbubakr QomorudeenNo ratings yet

- NFT Terminologies by Abubakr OlawaleDocument3 pagesNFT Terminologies by Abubakr OlawaleAbubakr QomorudeenNo ratings yet

- Duong Thanh Uyen - k204090478 - Acr4.2Document48 pagesDuong Thanh Uyen - k204090478 - Acr4.2Thanh UyênNo ratings yet

- 9AKK105789 EN 06-2018 General Perf PDFDocument52 pages9AKK105789 EN 06-2018 General Perf PDFhari setiawanNo ratings yet

- Ficha Técnica - RPS Tyco ElectronicsDocument2 pagesFicha Técnica - RPS Tyco ElectronicsGalindo FivigaorNo ratings yet

- Assignment in Binomial Distribution PINEDA PLM (ATTEMPT 2)Document2 pagesAssignment in Binomial Distribution PINEDA PLM (ATTEMPT 2)Patrick PinedaNo ratings yet

- Rekonstruksi Pola Perilaku Ekonomi Dan Krisis Pesona Yang Dihadapi Produsen Di Masa Covid-19Document8 pagesRekonstruksi Pola Perilaku Ekonomi Dan Krisis Pesona Yang Dihadapi Produsen Di Masa Covid-19Alda OctaviaNo ratings yet

- Kaushal Parmar 22B3M063Document25 pagesKaushal Parmar 22B3M063Kaushal ParmarNo ratings yet

- MGMT2020 - Revision GuideDocument7 pagesMGMT2020 - Revision GuideChelsea FordeNo ratings yet

- Fake Invoice SSDocument24 pagesFake Invoice SSSUBHASH SHARMANo ratings yet

- Klein - The Life of John Maynard KeynesDocument10 pagesKlein - The Life of John Maynard KeyneseddieNo ratings yet

- Full Download Managerial Economics Foundations of Business Analysis and Strategy 11th Edition Thomas Test BankDocument36 pagesFull Download Managerial Economics Foundations of Business Analysis and Strategy 11th Edition Thomas Test Bankthuyradzavichzuk100% (41)

- Dwnload Full Introductory Mathematical Analysis For Business Economics and The Life and Social Sciences 14th Edition Paul Test Bank PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Introductory Mathematical Analysis For Business Economics and The Life and Social Sciences 14th Edition Paul Test Bank PDFdheybarlowm100% (13)

- Ind Nifty RealtyDocument2 pagesInd Nifty RealtyParth AsnaniNo ratings yet

- An Approach To Determine The Health Index of Power TransformersDocument5 pagesAn Approach To Determine The Health Index of Power Transformersbaby MaNo ratings yet

- FPM1 Dunning - : Read The Document: 313121576-SAP-Collections-and-Disbursement-PDF-1Document20 pagesFPM1 Dunning - : Read The Document: 313121576-SAP-Collections-and-Disbursement-PDF-1HoNo ratings yet

- District Wise Exports of India - 2021Document13 pagesDistrict Wise Exports of India - 2021MNo ratings yet

- SUMMATIVE TEST in Statistics ProbabilityDocument2 pagesSUMMATIVE TEST in Statistics ProbabilitySpade Bun0% (1)

- D6053-Analysis Apprach Source Strategy General Studies Pre Paper I 2021 eDocument109 pagesD6053-Analysis Apprach Source Strategy General Studies Pre Paper I 2021 eSanjog MechuNo ratings yet

- MECH REC69 Magnetic Particle Dye Penetrant ReportDocument1 pageMECH REC69 Magnetic Particle Dye Penetrant ReporttinzarmoeNo ratings yet

- Power Feed-Thru Systems & ConnectorsDocument2 pagesPower Feed-Thru Systems & Connectorsclaudio godinezNo ratings yet

- Hortatory TextDocument2 pagesHortatory TextDaffa MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Working Towards A Better Brazil: National Strategy For Financial Education (Enef)Document164 pagesWorking Towards A Better Brazil: National Strategy For Financial Education (Enef)Carlos NetoNo ratings yet

- TDS TM SYSTEM POLIMAC - Rev. 02 - 20221107Document2 pagesTDS TM SYSTEM POLIMAC - Rev. 02 - 20221107xref akunNo ratings yet

- 46SV2N075T, 200gpm@120ftDocument4 pages46SV2N075T, 200gpm@120ftSajidNo ratings yet

- Instructional Module: Republic of The Philippines Nueva Vizcaya State University Bayombong, Nueva VizcayaDocument7 pagesInstructional Module: Republic of The Philippines Nueva Vizcaya State University Bayombong, Nueva VizcayaDaisy BuwacNo ratings yet

- Naipo MGF-701 Rechargeable Leg Compression MassagerDocument1 pageNaipo MGF-701 Rechargeable Leg Compression MassagerMd Aminul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Exercise IIDocument2 pagesTutorial Exercise IILemma MuletaNo ratings yet

- Floor InletDocument2 pagesFloor Inletmauro zarateNo ratings yet

- BUDGET Part & SERVICE 2024 PLBDocument32 pagesBUDGET Part & SERVICE 2024 PLBService JakartaNo ratings yet