Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Philippine Associations of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary (1955), Lacno, EH 201

Philippine Associations of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary (1955), Lacno, EH 201

Uploaded by

Earl Franco LacnoCopyright:

Available Formats

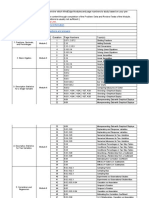

You might also like

- Global Business 4th Edition Ebook PDFDocument42 pagesGlobal Business 4th Edition Ebook PDFrobert.higa747100% (40)

- Swot AnalysisDocument3 pagesSwot AnalysisJasmin Celedonio Laurente100% (8)

- Quezon City PTCA v. Department of Education DigestDocument3 pagesQuezon City PTCA v. Department of Education DigestDanella Dimapilis100% (4)

- 5 Pimentel V, Legal Education BoardDocument2 pages5 Pimentel V, Legal Education Boardchristopher1julian1a100% (2)

- Pimentel Vs LebDocument2 pagesPimentel Vs LebJames Hydoe Elan80% (5)

- PACU Vs Secretary of Education, 97 Phil 806 1955Document13 pagesPACU Vs Secretary of Education, 97 Phil 806 1955Reginald Dwight Florido0% (1)

- Quaker Oats & SnappleDocument5 pagesQuaker Oats & SnappleemmafaveNo ratings yet

- Case #35 PACU v. Secretary of Education, G.R. No. L-5279, October 31, 1955Document15 pagesCase #35 PACU v. Secretary of Education, G.R. No. L-5279, October 31, 1955castorestelita63No ratings yet

- 1 Pacu Vs SEC of EducDocument2 pages1 Pacu Vs SEC of Educberryb_07No ratings yet

- Pacu V Secretary of EducationDocument2 pagesPacu V Secretary of EducationTanya IñigoNo ratings yet

- PACU Vs Secretary of EducationDocument5 pagesPACU Vs Secretary of EducationLizzy WayNo ratings yet

- Case Digest: Pimentel vs. Leb G.R. No. 230642 & 242954. September 10, 2019Document11 pagesCase Digest: Pimentel vs. Leb G.R. No. 230642 & 242954. September 10, 2019Jun Bill CercadoNo ratings yet

- Pacu VS Secretary of EducationDocument6 pagesPacu VS Secretary of EducationJHIM TEPASENo ratings yet

- PACU VS. SECRETATY OF EDUCATION G.R. No. L-5279 October 31, 1955Document5 pagesPACU VS. SECRETATY OF EDUCATION G.R. No. L-5279 October 31, 1955Harry BasadaNo ratings yet

- Judical Review FullDocument47 pagesJudical Review FullClarisse30No ratings yet

- 149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges And20210425-12-Qsa0k9Document10 pages149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges And20210425-12-Qsa0k9RHANDY MAEKHAEL LIBRADO ONGNo ratings yet

- Philippine Association of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary of Education, G.R. No. L-5279, 1955Document8 pagesPhilippine Association of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary of Education, G.R. No. L-5279, 1955JMae MagatNo ratings yet

- K To 12 Law Was Duly Enacted: Facts: IssueDocument33 pagesK To 12 Law Was Duly Enacted: Facts: IssueTherese JavierNo ratings yet

- 9 PACU V Secretary of EducationDocument3 pages9 PACU V Secretary of EducationAnonymous hS0s2moNo ratings yet

- 01 PACU v. Secretary of EducationDocument8 pages01 PACU v. Secretary of Educationlenard5No ratings yet

- 149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges andDocument9 pages149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges andVida MarieNo ratings yet

- PACU Vs Secretary of EducatinDocument1 pagePACU Vs Secretary of EducatinJessica SandiNo ratings yet

- PIMENTEL Vs LEBDocument7 pagesPIMENTEL Vs LEBAlyssa joy TorioNo ratings yet

- Pacu VS Sec. of EducDocument2 pagesPacu VS Sec. of EducBudoy0% (1)

- Consti 2 DigestsDocument4 pagesConsti 2 DigestsKatrizia FauniNo ratings yet

- 149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges andDocument16 pages149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges andTori PeigeNo ratings yet

- PACU v. Secretary of Education 97 Phil. 806Document11 pagesPACU v. Secretary of Education 97 Phil. 806Bea CapeNo ratings yet

- Philippine Association of Colleges and Universities, Etc vs. Secretary of Education and The Board of TextbooksDocument2 pagesPhilippine Association of Colleges and Universities, Etc vs. Secretary of Education and The Board of TextbooksRiffy OisinoidNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-5279Document11 pagesG.R. No. L-5279kai lumagueNo ratings yet

- Admin Law Case DigestDocument29 pagesAdmin Law Case DigestIcee Genio93% (15)

- G.R. No. 78385 August 31, 1987 Philippine Consumers Foundation, Inc., Petitioner, vs. The Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports, RespondentDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 78385 August 31, 1987 Philippine Consumers Foundation, Inc., Petitioner, vs. The Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports, Respondentwenny capplemanNo ratings yet

- CoTeSCUP Vs Secretary of EducationDocument12 pagesCoTeSCUP Vs Secretary of EducationsundaeicecreamNo ratings yet

- Ponente: Bengzon, J. Statement of Facts and Procedural HistoryDocument2 pagesPonente: Bengzon, J. Statement of Facts and Procedural HistoryKarminnCherylYangotNo ratings yet

- 8.quezon City PTCA Vs DepEdDocument2 pages8.quezon City PTCA Vs DepEdA M I R ANo ratings yet

- PACU vs. Secretary of Education, 97 Phil. 806 (1955)Document6 pagesPACU vs. Secretary of Education, 97 Phil. 806 (1955)noemi alvarezNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - PACU v. Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806Document2 pagesCase Digest - PACU v. Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806Nilfpe SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Consti Cases Judicial DeptDocument3 pagesConsti Cases Judicial DeptDon YcayNo ratings yet

- Marbury Vs Madison: Cases: Origin of Judicial ReviewDocument7 pagesMarbury Vs Madison: Cases: Origin of Judicial ReviewTrishNo ratings yet

- Pimentel Vs LEBDocument3 pagesPimentel Vs LEBPATRICIA MAE CABANA80% (5)

- Case Digest: Pimentel vs. Leb G.R. No. 230642 & 242954. September 10, 2019Document4 pagesCase Digest: Pimentel vs. Leb G.R. No. 230642 & 242954. September 10, 2019Lou Angelique Heruela0% (2)

- PACU VS Sec of EducDocument7 pagesPACU VS Sec of EducjazrethNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-5279.PDF Pacu Vs Sec of EducDocument7 pagesG.R. No. L-5279.PDF Pacu Vs Sec of EducAronJamesNo ratings yet

- Pimentel V LebDocument15 pagesPimentel V LebAIL REGINE REY MABIDANo ratings yet

- Pimentel Vs LebDocument2 pagesPimentel Vs LebJames Hydoe Elan100% (4)

- HomewerkDocument3 pagesHomewerkFay FernandoNo ratings yet

- PACU Vs Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806 1955Document16 pagesPACU Vs Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806 1955DanielNo ratings yet

- Case 1 Dumlao vs. Comelec: Pacu vs. Secretary of EducationDocument13 pagesCase 1 Dumlao vs. Comelec: Pacu vs. Secretary of Educationharrison SajorNo ratings yet

- Mota Presented. Any Attempt at Abstraction Could Only Lead To Dialectics and Barren Legal Questions and ToDocument2 pagesMota Presented. Any Attempt at Abstraction Could Only Lead To Dialectics and Barren Legal Questions and ToNash LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Pimentel Vs LEBDocument3 pagesPimentel Vs LEBChloe Hernane100% (1)

- Pimentel vs. LEBDocument3 pagesPimentel vs. LEBjovani emaNo ratings yet

- Pacu VS Secretary of Education Gr. No. L 5279Document1 pagePacu VS Secretary of Education Gr. No. L 5279Jay Ar Lanon EgangNo ratings yet

- Pimentel v. Leb (Philsat Issue)Document9 pagesPimentel v. Leb (Philsat Issue)Jett ChuaquicoNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - Pimentel VS LebDocument12 pagesCase Digest - Pimentel VS LebKirsten SazonNo ratings yet

- Pacu Vs Secretary of Education Digest and Full TextDocument10 pagesPacu Vs Secretary of Education Digest and Full TextKing BautistaNo ratings yet

- Pimentel V LEBDocument4 pagesPimentel V LEBZaira Mae Awat100% (4)

- ABAKADA Guro Party List V PurisimaDocument7 pagesABAKADA Guro Party List V PurisimaMaria Lourdes Dator100% (1)

- Supreme Court: Custom SearchDocument6 pagesSupreme Court: Custom SearchJenny Mary DagunNo ratings yet

- The 1987 Administrative Code Defines A Government Instrumentality As FollowsDocument5 pagesThe 1987 Administrative Code Defines A Government Instrumentality As FollowsNesty Perez IIINo ratings yet

- Case 21 - PACU V DepEdDocument2 pagesCase 21 - PACU V DepEdChristine NamucoNo ratings yet

- Dpacu Vs Sec of Educ.Document2 pagesDpacu Vs Sec of Educ.jaysraelNo ratings yet

- 1 Philippine Association of Colleges and Universities Vs Secretary of Education - The Welfare of The People Shall Be The Supreme LawDocument2 pages1 Philippine Association of Colleges and Universities Vs Secretary of Education - The Welfare of The People Shall Be The Supreme LawKhenna Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Weak Courts, Strong Rights: Judicial Review and Social Welfare Rights in Comparative Constitutional LawFrom EverandWeak Courts, Strong Rights: Judicial Review and Social Welfare Rights in Comparative Constitutional LawRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Persuasive Essay - Project 4Document6 pagesPersuasive Essay - Project 4api-302893696No ratings yet

- PGD-SelList-R3 - 12.05.2018Document18 pagesPGD-SelList-R3 - 12.05.2018Samir SharmaNo ratings yet

- FidBond Enrolment Form Template Pinaka Bago PassiNHSDocument7 pagesFidBond Enrolment Form Template Pinaka Bago PassiNHSJoji Marie Castro PalecNo ratings yet

- Eni MP Grease 2 - 1720 - 5.0 - ENDocument16 pagesEni MP Grease 2 - 1720 - 5.0 - ENMuhammad Abdul RehmanNo ratings yet

- Peis and MmisDocument8 pagesPeis and MmisErjan ManaliliNo ratings yet

- Mikrotik Basic Internet Sharing With Bandwidth LimitingDocument8 pagesMikrotik Basic Internet Sharing With Bandwidth LimitingMuhammad Abdullah ButtNo ratings yet

- Resilience Definitions Theory and ChallengesDocument14 pagesResilience Definitions Theory and ChallengesRaji Rafiu BoyeNo ratings yet

- FS4 Exploring The CurriculumDocument57 pagesFS4 Exploring The CurriculumLoynalen MaturanNo ratings yet

- ResumeDocument1 pageResumeBecca SmartNo ratings yet

- Foreign Direct Investment in Nepal: Social Inquiry: Journal of Social Science ResearchDocument20 pagesForeign Direct Investment in Nepal: Social Inquiry: Journal of Social Science Researchjames smithNo ratings yet

- Social Cognitive Theory and Physical ActivityDocument13 pagesSocial Cognitive Theory and Physical ActivityMega AnggraeniNo ratings yet

- Acoustic Legends:: Key PlanDocument1 pageAcoustic Legends:: Key PlanFaheem MushtaqNo ratings yet

- CHECKLIST OF REQUIREMENTS Annex CDocument1 pageCHECKLIST OF REQUIREMENTS Annex CLaarni RamirezNo ratings yet

- Unit 10: Values: Lesson A Objective: Learn To Talk About Moral DilemmasDocument7 pagesUnit 10: Values: Lesson A Objective: Learn To Talk About Moral DilemmasLiss PeñafielNo ratings yet

- Installation Guide T-Marc 3306 MN100280 Revision ADocument43 pagesInstallation Guide T-Marc 3306 MN100280 Revision AMarco Ur100% (1)

- C955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Document3 pagesC955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Robert Allen Rippey0% (1)

- In Re Hill Trustees Preliminary Recommendation On Sanctions For Leslie PUIDA and GMM 17 Nov 2010Document9 pagesIn Re Hill Trustees Preliminary Recommendation On Sanctions For Leslie PUIDA and GMM 17 Nov 2010William A. Roper Jr.No ratings yet

- Computer Systems Servicing: 3 Quarter Week 1Document7 pagesComputer Systems Servicing: 3 Quarter Week 1Romnick PortillanoNo ratings yet

- Unit-4-Electrical Machines: Lecture-3 Starting methods of 3-Φ Induction MotorDocument13 pagesUnit-4-Electrical Machines: Lecture-3 Starting methods of 3-Φ Induction MotorPratik SarkarNo ratings yet

- PDF Abstrak-20335667Document1 pagePDF Abstrak-20335667hirukihealNo ratings yet

- Opt 101Document31 pagesOpt 101Diego AraújoNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Satellite Constellations For The Continuous Coverage of Ground RegionsDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Satellite Constellations For The Continuous Coverage of Ground RegionsOksana VoloshenyukNo ratings yet

- PMBOK Guide 5th Edition - NotesDocument50 pagesPMBOK Guide 5th Edition - NotesJoaoCOS100% (1)

- The Philippine Marketing Environment: Bruto, Ivy Marijoyce Magtibay, Sarah Jane Guno, RhizaDocument26 pagesThe Philippine Marketing Environment: Bruto, Ivy Marijoyce Magtibay, Sarah Jane Guno, Rhizakenghie tv showNo ratings yet

- Computers in Human Behavior: Stacy Horner, Yvonne Asher, Gary D. FiremanDocument8 pagesComputers in Human Behavior: Stacy Horner, Yvonne Asher, Gary D. FiremanArindra DwisyadyaningtyasNo ratings yet

- History of BankingDocument14 pagesHistory of Bankingrajeshpathak9No ratings yet

- Prelim Quiz 2 - Attempt Review PDFDocument4 pagesPrelim Quiz 2 - Attempt Review PDFPeter EcleviaNo ratings yet

Philippine Associations of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary (1955), Lacno, EH 201

Philippine Associations of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary (1955), Lacno, EH 201

Uploaded by

Earl Franco LacnoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Philippine Associations of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary (1955), Lacno, EH 201

Philippine Associations of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary (1955), Lacno, EH 201

Uploaded by

Earl Franco LacnoCopyright:

Available Formats

PHILIPPINE ASSOCIATION OF COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES,

ETC., petitioner, vs. SECRETARY OF EDUCATION and the BOARD

OF TEXTBOOKS, respondents, G.R. No. L-5279, 31 October, 1955,

FIRST DIVISION, BENGZON, J.

Digest by: Earl Franco P. Lacno, EH 201

Principle in sum:

“Bona fide suit. — Judicial power is limited to the decision of actual cases

and controversies. The authority to pass on the validity of statutes is

incidental to the decision of such cases where conflicting claims under the

Constitution and under a legislative act assailed as contrary to the

Constitution are raised. It is legitimate only in the last resort, and as

necessity in the determination of real, earnest, and vital controversy

between litigants.”

FACTS:

1. Act No. 2706 approved in 1917 is entitled, "An Act making the

inspection and recognition of private schools and colleges obligatory

for the Secretary of Public Instruction."

2. Under its provisions, the Department of Education has, for the past 37

years, supervised and regulated all private schools in this country

apparently without audible protest, nay, with the general acquiescence

of the general public and the parties concerned.

ISSUES:

A. Whether or not they deprive owners of schools and colleges as well as

teachers and parents of liberty and property without due process of

law;

B. WON their provisions conferring on the Secretary of Education

unlimited power and discretion to prescribe rules and standards

constitute an unlawful delegation of legislative power?

C. WON the assessment of 1 per cent levied on gross receipts of all

private schools for additional Government expenses in connection

with their supervision and regulation is unconstitutional?

D. Whether the law may be enacted in the exercise of the State's

constitutional power (Art. XIV, sec. 5) to supervise and regulate

private schools?

RULING:

A. Deprive owners of schools and colleges as well as teachers and

parents of liberty and property without due process of law

1. No, An unprejudiced consideration of the fact presented under the

caption Private Adventure Schools leads but to one conclusion, viz.:

the great majority of them from primary grade to university are

money-making devices for the profit of those who organize and

administer them. The people whose children and youth attend them

are not getting what they pay for. It is obvious that the system

constitutes a great evil. That it should be permitted to exist with

almost no supervision is indefensible. The suggestion has been made

with the reference to the private institutions of university grade that

some board of control be organized under legislative control to

supervise their administration. The Commission believes that the

recommendations it offers at the end of this chapter are more likely to

bring about the needed reforms.

2. In view of these finding and recommendations, can there be any doubt

that the Government in the exercise of its police power to correct "a

great evil" could validly establish the "previous permit" system

objected to by petitioners? This is what differentiates our law from the

other statutes declared invalid in other jurisdictions. And if any doubt

still exists, recourse may now be had to the provision of our

Constitution that "All educational institutions shall be under the

supervision and subject to regulation by the State." (Art. XIV, sec. 5.)

The power to regulate establishments or business occupations implies

the power to require a permit or license. (53 C. J. S. 4.)

3. What goes for the "previous permit" naturally goes for the power to

revoke such permit on account of violation of rules or regulations of

the Department.

B. Their provisions conferring on the Secretary of Education

unlimited power and discretion to prescribe rules and standards

constitute an unlawful delegation of legislative power.

1. No, despite such alleged vagueness the Secretary of Education has

fixed standards to ensure adequate and efficient instruction, as shown

by the memoranda fixing or revising curricula, the school calendars,

entrance and final examinations, admission and accreditation of

students etc.; and the system of private education has, in general, been

satisfactorily in operation for 37 years. Which only shows that the

Legislature did and could, validly rely upon the educational

experience and training of those in charge of the Department of

Education to ascertain and formulate minimum requirements of

adequate instruction as the basis of government recognition of any

private school.

2. It is clear in our opinion that the statute does not in express terms give

the Secretary complete control. It gives him powers to inspect private

schools, to regulate their activities, to give them official permits to

operate under certain conditions, and to revoke such permits for cause.

This does not amount to complete control. If any of such Department

circulars or memoranda issued by the Secretary go beyond the bounds

of regulation and seeks to establish complete control, it would surely

be invalid. Conceivably some of them are of this nature, but besides

not having before us the text of such circulars, the petitioners have

omitted to specify. In any event with the recent approval of Republic

Act No. 1124 creating the National Board of Education, opportunity

for administrative correction of the supposed anomalies or

encroachments is amply afforded herein petitioners. A more

expeditious and perhaps more technically competent forum exists,

wherein to discuss the necessity, convenience or relevancy of the

measures criticized by them. (See also Republic Act No. 176.)

C. The assessment of 1 per cent levied on gross receipts of all private

schools for additional Government expenses

1. There are good grounds in support of the Government's position. If

this levy of 1 per cent is truly a mere fee — and not a tax — to finance

the cost of the Department's duty and power to regulate and supervise

private schools, the exaction may be upheld; but such point involves

investigation and examination of relevant data, which should best be

carried out in the lower courts. If on the other hand it is a tax,

petitioners' issue would still be within the original jurisdiction of the

Courts of First Instance.

D. Law may be enacted in the exercise of the State's constitutional

power

1. In this connection we do not share the belief that section 5 has added

new power to what the State inherently possesses by virtue of the

police power. An express power is necessarily more extensive than a

mere implied power. For instance, if there is conflict between an

express individual right and the express power to control private

education it cannot off-hand be said that the latter must yield to the

former — conflict of two express powers. But if the power to control

education is merely implied from the police power, it is feasible to

uphold the express individual right, as was probably the situation in

the two decisions brought to our attention, of Mississippi and

Minnesota, states where constitutional control of private schools is not

expressly produced.

2. However, as herein previously noted, no justiciable controversy has

been presented to us. We are not informed that the Board on

Textbooks has prohibited this or that text, or that the petitioners

refused or intend to refuse to submit some textbooks, and are in

danger of losing substantial privileges or rights for so refusing.

xxx

You might also like

- Global Business 4th Edition Ebook PDFDocument42 pagesGlobal Business 4th Edition Ebook PDFrobert.higa747100% (40)

- Swot AnalysisDocument3 pagesSwot AnalysisJasmin Celedonio Laurente100% (8)

- Quezon City PTCA v. Department of Education DigestDocument3 pagesQuezon City PTCA v. Department of Education DigestDanella Dimapilis100% (4)

- 5 Pimentel V, Legal Education BoardDocument2 pages5 Pimentel V, Legal Education Boardchristopher1julian1a100% (2)

- Pimentel Vs LebDocument2 pagesPimentel Vs LebJames Hydoe Elan80% (5)

- PACU Vs Secretary of Education, 97 Phil 806 1955Document13 pagesPACU Vs Secretary of Education, 97 Phil 806 1955Reginald Dwight Florido0% (1)

- Quaker Oats & SnappleDocument5 pagesQuaker Oats & SnappleemmafaveNo ratings yet

- Case #35 PACU v. Secretary of Education, G.R. No. L-5279, October 31, 1955Document15 pagesCase #35 PACU v. Secretary of Education, G.R. No. L-5279, October 31, 1955castorestelita63No ratings yet

- 1 Pacu Vs SEC of EducDocument2 pages1 Pacu Vs SEC of Educberryb_07No ratings yet

- Pacu V Secretary of EducationDocument2 pagesPacu V Secretary of EducationTanya IñigoNo ratings yet

- PACU Vs Secretary of EducationDocument5 pagesPACU Vs Secretary of EducationLizzy WayNo ratings yet

- Case Digest: Pimentel vs. Leb G.R. No. 230642 & 242954. September 10, 2019Document11 pagesCase Digest: Pimentel vs. Leb G.R. No. 230642 & 242954. September 10, 2019Jun Bill CercadoNo ratings yet

- Pacu VS Secretary of EducationDocument6 pagesPacu VS Secretary of EducationJHIM TEPASENo ratings yet

- PACU VS. SECRETATY OF EDUCATION G.R. No. L-5279 October 31, 1955Document5 pagesPACU VS. SECRETATY OF EDUCATION G.R. No. L-5279 October 31, 1955Harry BasadaNo ratings yet

- Judical Review FullDocument47 pagesJudical Review FullClarisse30No ratings yet

- 149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges And20210425-12-Qsa0k9Document10 pages149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges And20210425-12-Qsa0k9RHANDY MAEKHAEL LIBRADO ONGNo ratings yet

- Philippine Association of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary of Education, G.R. No. L-5279, 1955Document8 pagesPhilippine Association of Colleges and Universities v. Secretary of Education, G.R. No. L-5279, 1955JMae MagatNo ratings yet

- K To 12 Law Was Duly Enacted: Facts: IssueDocument33 pagesK To 12 Law Was Duly Enacted: Facts: IssueTherese JavierNo ratings yet

- 9 PACU V Secretary of EducationDocument3 pages9 PACU V Secretary of EducationAnonymous hS0s2moNo ratings yet

- 01 PACU v. Secretary of EducationDocument8 pages01 PACU v. Secretary of Educationlenard5No ratings yet

- 149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges andDocument9 pages149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges andVida MarieNo ratings yet

- PACU Vs Secretary of EducatinDocument1 pagePACU Vs Secretary of EducatinJessica SandiNo ratings yet

- PIMENTEL Vs LEBDocument7 pagesPIMENTEL Vs LEBAlyssa joy TorioNo ratings yet

- Pacu VS Sec. of EducDocument2 pagesPacu VS Sec. of EducBudoy0% (1)

- Consti 2 DigestsDocument4 pagesConsti 2 DigestsKatrizia FauniNo ratings yet

- 149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges andDocument16 pages149299-1955-Philippine Associations of Colleges andTori PeigeNo ratings yet

- PACU v. Secretary of Education 97 Phil. 806Document11 pagesPACU v. Secretary of Education 97 Phil. 806Bea CapeNo ratings yet

- Philippine Association of Colleges and Universities, Etc vs. Secretary of Education and The Board of TextbooksDocument2 pagesPhilippine Association of Colleges and Universities, Etc vs. Secretary of Education and The Board of TextbooksRiffy OisinoidNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-5279Document11 pagesG.R. No. L-5279kai lumagueNo ratings yet

- Admin Law Case DigestDocument29 pagesAdmin Law Case DigestIcee Genio93% (15)

- G.R. No. 78385 August 31, 1987 Philippine Consumers Foundation, Inc., Petitioner, vs. The Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports, RespondentDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 78385 August 31, 1987 Philippine Consumers Foundation, Inc., Petitioner, vs. The Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports, Respondentwenny capplemanNo ratings yet

- CoTeSCUP Vs Secretary of EducationDocument12 pagesCoTeSCUP Vs Secretary of EducationsundaeicecreamNo ratings yet

- Ponente: Bengzon, J. Statement of Facts and Procedural HistoryDocument2 pagesPonente: Bengzon, J. Statement of Facts and Procedural HistoryKarminnCherylYangotNo ratings yet

- 8.quezon City PTCA Vs DepEdDocument2 pages8.quezon City PTCA Vs DepEdA M I R ANo ratings yet

- PACU vs. Secretary of Education, 97 Phil. 806 (1955)Document6 pagesPACU vs. Secretary of Education, 97 Phil. 806 (1955)noemi alvarezNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - PACU v. Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806Document2 pagesCase Digest - PACU v. Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806Nilfpe SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Consti Cases Judicial DeptDocument3 pagesConsti Cases Judicial DeptDon YcayNo ratings yet

- Marbury Vs Madison: Cases: Origin of Judicial ReviewDocument7 pagesMarbury Vs Madison: Cases: Origin of Judicial ReviewTrishNo ratings yet

- Pimentel Vs LEBDocument3 pagesPimentel Vs LEBPATRICIA MAE CABANA80% (5)

- Case Digest: Pimentel vs. Leb G.R. No. 230642 & 242954. September 10, 2019Document4 pagesCase Digest: Pimentel vs. Leb G.R. No. 230642 & 242954. September 10, 2019Lou Angelique Heruela0% (2)

- PACU VS Sec of EducDocument7 pagesPACU VS Sec of EducjazrethNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-5279.PDF Pacu Vs Sec of EducDocument7 pagesG.R. No. L-5279.PDF Pacu Vs Sec of EducAronJamesNo ratings yet

- Pimentel V LebDocument15 pagesPimentel V LebAIL REGINE REY MABIDANo ratings yet

- Pimentel Vs LebDocument2 pagesPimentel Vs LebJames Hydoe Elan100% (4)

- HomewerkDocument3 pagesHomewerkFay FernandoNo ratings yet

- PACU Vs Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806 1955Document16 pagesPACU Vs Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806 1955DanielNo ratings yet

- Case 1 Dumlao vs. Comelec: Pacu vs. Secretary of EducationDocument13 pagesCase 1 Dumlao vs. Comelec: Pacu vs. Secretary of Educationharrison SajorNo ratings yet

- Mota Presented. Any Attempt at Abstraction Could Only Lead To Dialectics and Barren Legal Questions and ToDocument2 pagesMota Presented. Any Attempt at Abstraction Could Only Lead To Dialectics and Barren Legal Questions and ToNash LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Pimentel Vs LEBDocument3 pagesPimentel Vs LEBChloe Hernane100% (1)

- Pimentel vs. LEBDocument3 pagesPimentel vs. LEBjovani emaNo ratings yet

- Pacu VS Secretary of Education Gr. No. L 5279Document1 pagePacu VS Secretary of Education Gr. No. L 5279Jay Ar Lanon EgangNo ratings yet

- Pimentel v. Leb (Philsat Issue)Document9 pagesPimentel v. Leb (Philsat Issue)Jett ChuaquicoNo ratings yet

- Case Digest - Pimentel VS LebDocument12 pagesCase Digest - Pimentel VS LebKirsten SazonNo ratings yet

- Pacu Vs Secretary of Education Digest and Full TextDocument10 pagesPacu Vs Secretary of Education Digest and Full TextKing BautistaNo ratings yet

- Pimentel V LEBDocument4 pagesPimentel V LEBZaira Mae Awat100% (4)

- ABAKADA Guro Party List V PurisimaDocument7 pagesABAKADA Guro Party List V PurisimaMaria Lourdes Dator100% (1)

- Supreme Court: Custom SearchDocument6 pagesSupreme Court: Custom SearchJenny Mary DagunNo ratings yet

- The 1987 Administrative Code Defines A Government Instrumentality As FollowsDocument5 pagesThe 1987 Administrative Code Defines A Government Instrumentality As FollowsNesty Perez IIINo ratings yet

- Case 21 - PACU V DepEdDocument2 pagesCase 21 - PACU V DepEdChristine NamucoNo ratings yet

- Dpacu Vs Sec of Educ.Document2 pagesDpacu Vs Sec of Educ.jaysraelNo ratings yet

- 1 Philippine Association of Colleges and Universities Vs Secretary of Education - The Welfare of The People Shall Be The Supreme LawDocument2 pages1 Philippine Association of Colleges and Universities Vs Secretary of Education - The Welfare of The People Shall Be The Supreme LawKhenna Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Weak Courts, Strong Rights: Judicial Review and Social Welfare Rights in Comparative Constitutional LawFrom EverandWeak Courts, Strong Rights: Judicial Review and Social Welfare Rights in Comparative Constitutional LawRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Persuasive Essay - Project 4Document6 pagesPersuasive Essay - Project 4api-302893696No ratings yet

- PGD-SelList-R3 - 12.05.2018Document18 pagesPGD-SelList-R3 - 12.05.2018Samir SharmaNo ratings yet

- FidBond Enrolment Form Template Pinaka Bago PassiNHSDocument7 pagesFidBond Enrolment Form Template Pinaka Bago PassiNHSJoji Marie Castro PalecNo ratings yet

- Eni MP Grease 2 - 1720 - 5.0 - ENDocument16 pagesEni MP Grease 2 - 1720 - 5.0 - ENMuhammad Abdul RehmanNo ratings yet

- Peis and MmisDocument8 pagesPeis and MmisErjan ManaliliNo ratings yet

- Mikrotik Basic Internet Sharing With Bandwidth LimitingDocument8 pagesMikrotik Basic Internet Sharing With Bandwidth LimitingMuhammad Abdullah ButtNo ratings yet

- Resilience Definitions Theory and ChallengesDocument14 pagesResilience Definitions Theory and ChallengesRaji Rafiu BoyeNo ratings yet

- FS4 Exploring The CurriculumDocument57 pagesFS4 Exploring The CurriculumLoynalen MaturanNo ratings yet

- ResumeDocument1 pageResumeBecca SmartNo ratings yet

- Foreign Direct Investment in Nepal: Social Inquiry: Journal of Social Science ResearchDocument20 pagesForeign Direct Investment in Nepal: Social Inquiry: Journal of Social Science Researchjames smithNo ratings yet

- Social Cognitive Theory and Physical ActivityDocument13 pagesSocial Cognitive Theory and Physical ActivityMega AnggraeniNo ratings yet

- Acoustic Legends:: Key PlanDocument1 pageAcoustic Legends:: Key PlanFaheem MushtaqNo ratings yet

- CHECKLIST OF REQUIREMENTS Annex CDocument1 pageCHECKLIST OF REQUIREMENTS Annex CLaarni RamirezNo ratings yet

- Unit 10: Values: Lesson A Objective: Learn To Talk About Moral DilemmasDocument7 pagesUnit 10: Values: Lesson A Objective: Learn To Talk About Moral DilemmasLiss PeñafielNo ratings yet

- Installation Guide T-Marc 3306 MN100280 Revision ADocument43 pagesInstallation Guide T-Marc 3306 MN100280 Revision AMarco Ur100% (1)

- C955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Document3 pagesC955 Pre-Assessment - MindEdge Alignment Table - Sheet1Robert Allen Rippey0% (1)

- In Re Hill Trustees Preliminary Recommendation On Sanctions For Leslie PUIDA and GMM 17 Nov 2010Document9 pagesIn Re Hill Trustees Preliminary Recommendation On Sanctions For Leslie PUIDA and GMM 17 Nov 2010William A. Roper Jr.No ratings yet

- Computer Systems Servicing: 3 Quarter Week 1Document7 pagesComputer Systems Servicing: 3 Quarter Week 1Romnick PortillanoNo ratings yet

- Unit-4-Electrical Machines: Lecture-3 Starting methods of 3-Φ Induction MotorDocument13 pagesUnit-4-Electrical Machines: Lecture-3 Starting methods of 3-Φ Induction MotorPratik SarkarNo ratings yet

- PDF Abstrak-20335667Document1 pagePDF Abstrak-20335667hirukihealNo ratings yet

- Opt 101Document31 pagesOpt 101Diego AraújoNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Satellite Constellations For The Continuous Coverage of Ground RegionsDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Satellite Constellations For The Continuous Coverage of Ground RegionsOksana VoloshenyukNo ratings yet

- PMBOK Guide 5th Edition - NotesDocument50 pagesPMBOK Guide 5th Edition - NotesJoaoCOS100% (1)

- The Philippine Marketing Environment: Bruto, Ivy Marijoyce Magtibay, Sarah Jane Guno, RhizaDocument26 pagesThe Philippine Marketing Environment: Bruto, Ivy Marijoyce Magtibay, Sarah Jane Guno, Rhizakenghie tv showNo ratings yet

- Computers in Human Behavior: Stacy Horner, Yvonne Asher, Gary D. FiremanDocument8 pagesComputers in Human Behavior: Stacy Horner, Yvonne Asher, Gary D. FiremanArindra DwisyadyaningtyasNo ratings yet

- History of BankingDocument14 pagesHistory of Bankingrajeshpathak9No ratings yet

- Prelim Quiz 2 - Attempt Review PDFDocument4 pagesPrelim Quiz 2 - Attempt Review PDFPeter EcleviaNo ratings yet