Professional Documents

Culture Documents

IRNOPBODIESOFKNOWLEDGE

IRNOPBODIESOFKNOWLEDGE

Uploaded by

pilar gamaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Project Management Book PDFDocument55 pagesProject Management Book PDFSerigne Mbaye Diop94% (16)

- Project Management Body of KnowledgeDocument5 pagesProject Management Body of KnowledgeYael LevíNo ratings yet

- PMBOK For DummiesDocument18 pagesPMBOK For Dummiesingeamv100% (1)

- Front Office Executive - KRA & KPI - Example-13.05.2019Document4 pagesFront Office Executive - KRA & KPI - Example-13.05.2019Vinodkanna R100% (1)

- Communications Plan and TemplateDocument6 pagesCommunications Plan and TemplateBrittani Bell100% (1)

- Project Management StandardsDocument18 pagesProject Management Standardschandcs2000No ratings yet

- Research Updating The APM Body of Knowledge 4th Edition: Project ManagementDocument13 pagesResearch Updating The APM Body of Knowledge 4th Edition: Project ManagementTomasz WiatrNo ratings yet

- What Is Project Management?: Project Management-A Managerial Approach, 1995, by Jack R. Meredith and Samuel J. Mantel JRDocument28 pagesWhat Is Project Management?: Project Management-A Managerial Approach, 1995, by Jack R. Meredith and Samuel J. Mantel JREnes DenizdurduranNo ratings yet

- Development and Comparative Analysis of The Project Management Bodies of KnowledgeDocument6 pagesDevelopment and Comparative Analysis of The Project Management Bodies of KnowledgeGeorge PereiraNo ratings yet

- Project Management Paper - 131010 Ver 01Document5 pagesProject Management Paper - 131010 Ver 01Abubaker Sami AliNo ratings yet

- PMBOK 6th EditionDocument6 pagesPMBOK 6th EditionLuz GiraldoNo ratings yet

- PMF TextbookDocument154 pagesPMF TextbookFabian GomezNo ratings yet

- 01-03 Framework (PMP 6)Document139 pages01-03 Framework (PMP 6)Ahmed AshrafNo ratings yet

- PM-00-Introductory SessionDocument11 pagesPM-00-Introductory SessionHesam XYNo ratings yet

- 1.PM1 PmbokDocument12 pages1.PM1 Pmbokn jhaNo ratings yet

- Project Management Is Not NewDocument2 pagesProject Management Is Not NewQueen ValleNo ratings yet

- 1.PM1 - PMBOKDocument12 pages1.PM1 - PMBOKn jhaNo ratings yet

- Project Management: HistoryDocument13 pagesProject Management: Historyadeel rafiqNo ratings yet

- Intro To Pmbok PDFDocument3 pagesIntro To Pmbok PDFLaurence SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Enhance PMBOK® by Comparing It With P2M, ICB, PRINCE2, APM and Scrum Project Management StandardsDocument77 pagesEnhance PMBOK® by Comparing It With P2M, ICB, PRINCE2, APM and Scrum Project Management Standardssriram84No ratings yet

- Minggu Ke 2-Pengenalan Kepada Pengurusan ProjekDocument20 pagesMinggu Ke 2-Pengenalan Kepada Pengurusan ProjekNur'Aina Farhana NorzelanNo ratings yet

- Project Management - Session 1 PPT C1QaoR7cBgDocument58 pagesProject Management - Session 1 PPT C1QaoR7cBgHriday AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Assessing and Moving On From The Dominant Project Management Discourse in The Light of Project OverrunsDocument12 pagesAssessing and Moving On From The Dominant Project Management Discourse in The Light of Project OverrunsFarid KaskarNo ratings yet

- Project Management Principles Applied in Academic Research ProjectsDocument16 pagesProject Management Principles Applied in Academic Research ProjectsMuteeb KhanNo ratings yet

- P2M Promoted by PMAJDocument8 pagesP2M Promoted by PMAJOnofrei AndreiNo ratings yet

- The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) : Get The PDF VersionDocument7 pagesThe Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) : Get The PDF VersionIram HabibNo ratings yet

- Project Management Institute:: Analysis On The Role of Standardized Project Management On Project PerformanceDocument24 pagesProject Management Institute:: Analysis On The Role of Standardized Project Management On Project PerformanceAli MalikNo ratings yet

- Comparison of PM FrameworksDocument77 pagesComparison of PM Frameworkstico1_200067% (3)

- ICB - IPMA Competence Baseline Version 3.0Document212 pagesICB - IPMA Competence Baseline Version 3.0alex_parra100% (1)

- Overview of PM 20-01-2018Document59 pagesOverview of PM 20-01-2018Asad SaleemNo ratings yet

- CMP - Ref - Ipma - Icb3 v3.0Document212 pagesCMP - Ref - Ipma - Icb3 v3.0Kamel GuenatriNo ratings yet

- Mankon 01Document36 pagesMankon 01joseNo ratings yet

- Project Supervision and AdministratioinDocument17 pagesProject Supervision and AdministratiointaridanNo ratings yet

- Project Management Institute PyramidDocument4 pagesProject Management Institute PyramidsangeethNo ratings yet

- Subject Name: Operation ManagementDocument29 pagesSubject Name: Operation ManagementDhaval BhandariNo ratings yet

- TheLogicalFrameworkApproach MillenniumDocument15 pagesTheLogicalFrameworkApproach MillenniumBirhanuNo ratings yet

- Pmbok Guide Underneath The SurfaceDocument90 pagesPmbok Guide Underneath The Surfacealinakakaif100% (2)

- 01 C1-C2 Project Management For Entrepreneurs v03Document57 pages01 C1-C2 Project Management For Entrepreneurs v03Georgiana IlieNo ratings yet

- Integrated Project Control ID AgendaDocument8 pagesIntegrated Project Control ID Agendaody anjarNo ratings yet

- Ipma Icbv3 UsDocument212 pagesIpma Icbv3 Usinformarcio10No ratings yet

- Value & Risk ManagementDocument204 pagesValue & Risk ManagementlucioprovenzaniNo ratings yet

- 2 5237981465244871054 PDFDocument13 pages2 5237981465244871054 PDFاميرة الشمريNo ratings yet

- PMP Training Success GuideDocument32 pagesPMP Training Success GuidePrajaktaNo ratings yet

- 1: The Concept of Project ManagementDocument14 pages1: The Concept of Project ManagementAhmed SaigolNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Project Management: Unit 1: Chapter 1Document241 pagesIntroduction To Project Management: Unit 1: Chapter 1Vaibhav Bahel100% (1)

- w1 - Introduction To Sustainable Project ManagementDocument213 pagesw1 - Introduction To Sustainable Project ManagementAmanu PramonoNo ratings yet

- Vaskimo-Projektinhallinnan Metodologiat PDFDocument35 pagesVaskimo-Projektinhallinnan Metodologiat PDFBela Ulicsak100% (1)

- Project Management Competence For The New MilleniumDocument5 pagesProject Management Competence For The New MilleniumKannan PkNo ratings yet

- NL1 Introduction To Course ContentDocument24 pagesNL1 Introduction To Course ContentMikaelAdnanNo ratings yet

- Project Management Body PDFDocument3 pagesProject Management Body PDFRodrigo H Bustos MNo ratings yet

- Manajemen Konstruksi Lanjut (TM1)Document16 pagesManajemen Konstruksi Lanjut (TM1)kinoyNo ratings yet

- MGT471 - IPM - Course OutlineDocument6 pagesMGT471 - IPM - Course OutlineSRUTISMITA PATTANAIKNo ratings yet

- PMP 1Document46 pagesPMP 1Abdl Rahman GaberNo ratings yet

- CM651 Proj MGT Module 1 (061916)Document34 pagesCM651 Proj MGT Module 1 (061916)Rei Mark CoNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document14 pagesUnit 1Ahmed HeibaNo ratings yet

- Project Management Is TheDocument15 pagesProject Management Is TheBhargav NaiduNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S026378631630120X MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S026378631630120X MaingrkorosidisNo ratings yet

- Project Management ISO 21500-2012 KonermagDocument75 pagesProject Management ISO 21500-2012 KonermagerlanggaNo ratings yet

- Getting Started with Project Management: Managing Projects in Small BitesFrom EverandGetting Started with Project Management: Managing Projects in Small BitesNo ratings yet

- PROJECT MONITORING AND EVALUATION- A PRIMER: Every Student's Handbook on Project M & EFrom EverandPROJECT MONITORING AND EVALUATION- A PRIMER: Every Student's Handbook on Project M & ENo ratings yet

- 1.02 Stakeholder RegisterDocument1 page1.02 Stakeholder Registerpilar gamaNo ratings yet

- Global PM Competency Standards Status Report November 2001Document6 pagesGlobal PM Competency Standards Status Report November 2001pilar gamaNo ratings yet

- Partner TocDocument3 pagesPartner Tocpilar gamaNo ratings yet

- IPMbrochure2012 13Document34 pagesIPMbrochure2012 13pilar gamaNo ratings yet

- Site - Iugaza.edu - Ps Aschokry Files 2011 09 Introduction ToOperations and Production Management Chap 11Document32 pagesSite - Iugaza.edu - Ps Aschokry Files 2011 09 Introduction ToOperations and Production Management Chap 11Sana BhittaniNo ratings yet

- Article 6 - Differences Between A RFI RFQ and RFPDocument1 pageArticle 6 - Differences Between A RFI RFQ and RFPSibusiso Buthelezi100% (1)

- An Introduction To System Analysis and DesignDocument55 pagesAn Introduction To System Analysis and DesignedflookeNo ratings yet

- Requirement AnalysisDocument3 pagesRequirement AnalysisRohit ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Architectures Chapter 04Document9 pagesEnterprise Architectures Chapter 04palakNo ratings yet

- A20 Midterm ReviewerDocument2 pagesA20 Midterm ReviewerEy EmNo ratings yet

- Required Curriculum - MBA - Harvard Business SchoolDocument4 pagesRequired Curriculum - MBA - Harvard Business SchoolJerryJoshuaDiazNo ratings yet

- CH 10 AuditingDocument31 pagesCH 10 AuditingPutri Ayu Dwi LestariNo ratings yet

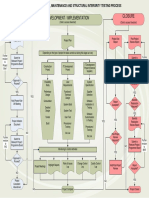

- Fundamental Test ProcessDocument4 pagesFundamental Test ProcessKamir ShahbazNo ratings yet

- GE - Nine CellDocument12 pagesGE - Nine CellNikita SangalNo ratings yet

- Total Quality Management Question PaperDocument4 pagesTotal Quality Management Question Papervpsravi67% (3)

- 5 Strategy Generation and SelectionDocument55 pages5 Strategy Generation and SelectionAhmad EkoNo ratings yet

- Eight P's in Marketing TourismDocument2 pagesEight P's in Marketing TourismInés PerazzaNo ratings yet

- U of A: Emergency Response RecommendationsDocument7 pagesU of A: Emergency Response RecommendationsEmily MertzNo ratings yet

- Project Initiation To CompletionDocument4 pagesProject Initiation To CompletionjesusgameboyNo ratings yet

- Role of Doctors and Nurses in Material MDocument1 pageRole of Doctors and Nurses in Material MPrakash kumar gourNo ratings yet

- 1030 Stephen Brobst Semantic Data ModelingDocument16 pages1030 Stephen Brobst Semantic Data ModelinghaiderabbaskhattakNo ratings yet

- Talent Mgt.Document37 pagesTalent Mgt.UMAMA UZAIR MIRZANo ratings yet

- Kra (Key Resulted Area) Based Incentice Scheme: Part - I To Be Filled by Human Resource DepartmentDocument8 pagesKra (Key Resulted Area) Based Incentice Scheme: Part - I To Be Filled by Human Resource DepartmentShivaramvarma MandapatiNo ratings yet

- 00 - 39 - 32 Earned Value Management PMP Exam Questions - MilestoneTaskDocument8 pages00 - 39 - 32 Earned Value Management PMP Exam Questions - MilestoneTaskLucky EdjenekpoNo ratings yet

- 7 SCM WastesDocument9 pages7 SCM WastesUswatun MaulidiyahNo ratings yet

- Maintainability Analysis.Document14 pagesMaintainability Analysis.Mary GwimileNo ratings yet

- NCE100 Gold Book PDFDocument60 pagesNCE100 Gold Book PDFAnonymous kRIjqBLkNo ratings yet

- Presentation of Le Mans UniversityDocument18 pagesPresentation of Le Mans UniversityTempus WebsitesNo ratings yet

- Transaction CyclesDocument2 pagesTransaction CyclesAdan NadaNo ratings yet

- Collaborative Planning, Forecasting & Replenishment (CPFR)Document16 pagesCollaborative Planning, Forecasting & Replenishment (CPFR)Seema HaloiNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Management at Accenture: Katia Arrus Jonathan Hayes Cristian Orellana Jay Bashucky Suresh JayaramanDocument38 pagesKnowledge Management at Accenture: Katia Arrus Jonathan Hayes Cristian Orellana Jay Bashucky Suresh JayaramannarcisalotruNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management ScorecardDocument11 pagesSupply Chain Management ScorecardAjay Kumar100% (1)

IRNOPBODIESOFKNOWLEDGE

IRNOPBODIESOFKNOWLEDGE

Uploaded by

pilar gamaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

IRNOPBODIESOFKNOWLEDGE

IRNOPBODIESOFKNOWLEDGE

Uploaded by

pilar gamaCopyright:

Available Formats

INDECO Ltd – International Management Consultants & Project Managers

UPDATING THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT BODIES OF KNOWLEDGE

Peter W.G. Morris

Centre for Research in the Management of Projects, UMIST

Summary

Project management Bodies of Knowledge (BoKs) have been published by the

professional project management associations now for ten to fifteen years. They are

enormously influential. Not only do they provide standards against which the

associations’ certification programmes are run, they are used by many practitioners and

companies as Best Practice guides to what the discipline comprises. Yet there are two or

three different BoKs, and all need updating. This paper reviews the status of BoKs and

reports on research on what topics should be included in the BoK (1) conducted at CRMP

using data from 117 companies and (2) through on-going work sponsored by NASA.

Introduction

Project management has grown from the early initiatives in the US defence/aerospace

sectors in the late 1950s/60s into a core competency that is widely recognised across most

industry sectors.

Initial formulations of project management – largely by the US Department of Defense

and NASA – consisted of internally promulgated policies, procedures and practices.

Later, books, articles, seminars and training programmes explored and expanded project

management practice. Much of this centred around the use of tools and techniques – such

as network scheduling and performance measurement – and organisational issues –

particularly middle management ones such as conflict management and teamwork [1].

From the late 60s to early 70s project management societies began to provide

professional forums for communication on the discipline, basically through journals,

conferences and seminars. This continued until the mid 1980s when first PMI, the US

based Project Management Institute, and later APM, the UK based Association for

Project Management, embarked on programmes to test whether people met their

standards of project management professionalism.

To be tested requires that there be a curriculum or similar reference work that can be used

as the basis of the test. PMI, as first in the field with this initiative [2], established its first

Project Management “Body of Knowledge” (BoK) in 1976 but it was not until the mid

1980s that PMI’s BoK became the basis of its standards and certification programme. As

shall be seen shortly, PMI’s BoK was revised several times during the 1980s and 90s.

Other professional bodies followed with their own BoKs in the late 80s and early 90s.

Several followed PMI, either using the PMI BoK as the knowledge element of their

competency assessment, as in the case of the Australian Institute of Project Management,

Peter Morris Page 1 1999

INDECO Ltd – International Management Consultants & Project Managers

IRNOP

or, as many have done, taking PMI’s package in toto as the basis of their project

management standards. (These associations generally in fact being Chapters of PMI.)

APM on the other hand, when it launched its certification programme in the early 90s,

felt that the then PMI BoK did not adequately reflect the knowledge base that project

management professionals needed. Hence APM developed its own BoK which differs

markedly from PMI’s.

APM’s certification programme was then adopted, and the APM BoK translated and

adapted, by several European countries. Austria, France, Germany, Switzerland, and The

Netherlands all had their own BoKs by the mid 1990s, largely reflecting the APM model.

In 1998 IPMA, the International Project Management Association, produced an amalgam

of these national BoKs – not including PMI’s however since it is not a member of IPMA

– with versions in French, English and German, together with proposals for harmonising

the various national project management qualifications [3].

The aim of all this activity on defining BoKs has thus, in short, been for the professional

associations to define what a project management practitioner ought to be knowledgeable

in, and through this, to provide a professional qualification in the discipline. (And as

such, incidentally, they also provide the project management component of many

enterprise-wide competency schemes.)

But in fact they do more than this. For in effect the Body of Knowledge should reflect the

purpose and provide the set of topics, relationships and definitions of project

management.

However, the fact that there are at least two (or three) quite different versions of the BoK

– PMI’s and APM’s (IPMA’s) – implies confusion at the highest level on what the

philosophy and content of the profession is. Basically the two (three) models reflect

different views of the discipline. PMI’s is basically focussed on the generic processes

required to accomplish a project “on time, in budget, to scope”. APM’s reflects a wider

view of the discipline, addressing both the context of project management and the

technological, commercial and general management issues which it believes are

important to successfully accomplishing projects.

Not only are there fundamentally differing models of the project management Body of

Knowledge, both PMI and APM have admitted that their BoKs are in need of updating

and do not fully reflect current perceptions of project management practice.

The situation, in short, is somewhere between being intellectually and professionally

inadequate and, at best, being in need of urgent revision! This paper reports on recent

work to address this state of affairs. It:

• reviews the status of the PMI, APM and IPMA Bodies of Knowledge;

Peter Morris Page 2 2000

INDECO Ltd – International Management Consultants & Project Managers

IRNOP

• then describes a major research programme conducted by the Centre for Research in

the Management of Projects at UMIST to investigate industry’s, academia’s, and UK

government’s view of the Body of Knowledge;

• then discusses work recently begun under the auspices of NASA to try and develop

an “expert” view of a global BoK;

• and finally discusses the relevance of all this work to efforts to define and develop

Best Practice in project management.

1. The PMI, APM, and IPMA Bodies of Knowledge

PMI’s PMBOK™

PMI established its first Project Management BoK in 1976 on the premise that there were

many management practices that were common to all projects and that codification of this

"Body of Knowledge" would be helpful not just to practising project management staff

but to teachers and certifiers of project management professionalism. It was not until

1981, however, that PMI’s Ethics, Standards and Accreditation Committee submitted its

recommendations for a BoK to the PMI Board of Directors. These were published in the

August 1983 issue of the Project Management Quarterly, and this subsequently formed

the basis for PMI’s initial accreditation and certification programmes. A revised

document was published in the August 1986 issue of the Project Management Journal

and approved by the PMI board in August 1987 as the “Project Management Body of

Knowledge”. Further work by PMI’s Standards Committee resulted in a revised

document titled “A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge”. This was

done to emphasise that even though the document defines the PMBoK as all those topics,

subject areas, and intellectual processes which are involved in the application of sound

management principles to projects – a claim which this paper will question – it will never

be able to contain the entire PMBoK which is out there in the universe of project

management. A further revised and updated version was published in 1996.

Trademarking of the term PMBoK was recently sought by PMI.

Currently, the structure of the PMI’s PMBOK™ document consists of “generally

accepted project management practices” represented by 37 component processes (Figure

1). It also includes a description of what the PMI defines as the “project management

framework”: definitions of key terms, a description of pertinent general management

skills, and an introduction to the concept of a project management process model.

APM’s BoK

In 1986 discussions in the UK led to the then Professional Standards Group (PSG) of

APM, the Association of Project Managers (now the Association for Project

Management,) developing an outline of what was to become the APM’s Body of

Knowledge. At this time, there was considerable debate both nationally and

internationally about whether "certification" of project managers should be based on

examination of knowledge or assessment of competence. The APM BoK was initially

developed specifically for candidates to assess their level of project management

Peter Morris Page 3 2000

INDECO Ltd – International Management Consultants & Project Managers

IRNOP

Project

Management

Project Integration Project Scope Management Project Time Management

Management •Initiation •Activity Definition

• Project Plan Development •Scope Planning •Activity Sequencing

•Project Plan Execution •Scope Definition •Activity Duration Estimating

•Overall Change Control •Scope Verification •Schedule Development

•Scope Change Control •Schedule Control

Project Cost

Management

Project Quality Project Human Resource

•Resource Management Management

Management

•Cost Estimating •OrganiztionalPlanning

•Cost Budgeting

•Quality Management

•Staff Acquisition

•Cost Control •Quality Assurance

•Team Development

•Quality Control

Project Communications Project Procurement

Management Management

Project Risk Management

•Communications Planning •Procurement Planning

•Risk Identification

•Information Distribution •Solicitation Planning

•Risk Quantification

•Performance Reporting •Solicitation

•Risk Response Development

•Administrative Closure •Source Selection

•Risk Response Control

•Contract Administration

•Contract Close-out

Figure 1: PMI PMBoK Structure

knowledge for the Certificated Project Manager (CPM) qualification then being

introduced by APM. The initial version of the APM’s BoK was published in April 1992.

(We shall turn to the question of why APM did not just adopt the PMI BoK in a moment.)

It was first. It was revised in July 1993, and then reviewed by the APM Education,

Training and Research Committee for a 1994 update. The current issue was revised in

January 1995.

The structure of the current APM Body of Knowledge is organised into four “key

competencies”: project management, organisation and people, processes and procedures,

and general management (Figure 2). Each of these competencies, in turn, is composed of

six to thirteen competency topics, there being 40 in all. Under each of the competency

topics, a “definition” can be found, examples of “knowledge” and “experience” levels,

and a list of or references.

European BoKs

Following its launch in the UK, several European countries became interested in

providing their own versions of APM’s CPM qualification. One of the first was the Dutch

Peter Morris Page 4 2000

INDECO Ltd – International Management Consultants & Project Managers

IRNOP

Project Management Organisation & People Techniques & Procedures General Management

—Systems Management —Organisation Design —Work Definition —Operational/Technical

Management

—Programme Management —Control & Co-ordination —Planning

—Project Management —Marketing & Sales

—Communication —Scheduling

—Project Life Cycle —Finance

—Leadership —Estimating

—Project Environment

—Information Technology

—Project Strategy —Delegation —Cost Control

—Law

—Project Appraisal —Team Builduing —Performance Measurement

—Project Success / —Procurement

Failure Criteria —Conflict Management —Risk Management

—Quality

—Integration —Negotiation —Value Management

—Systems & Procedures —Safety

—Management Development —Change Control

—Close Out —Industrial Relations

—Mobilisation

—Post Project Appraisal

Figure 2: APM Body of Knowledge Structure, revised 3rd Version'

association, PMI. (Confusingly, no relation to the US PMI.) The Swiss project

management association, SPM, and the German project management association, GPM,

also looked at the CPM and in doing so the APM BoK. This they translated, making

some changes as they did, though retaining the basic structure of the APM model. The

French society, AFITEP, translated an abbreviated version of the BoK.

By the mid 1990s, the International Project Management Association (IPMA), the

federation of national project management associations to which all these European

societies, as well as many others – but not PMI – belong, felt that it should attempt some

kind of coordination of the various national BoKs, not least so that those national

associations that had not yet their own version might have something to use.

Accordingly, work began in 1996 on producing a coordinated set of definitions. This was

published in English, French and German in 1998.

The IPMA BoK structure is shown in Figure 3. It adopted the term, “The Sunflower”, to

describe its structure. The sunflower structure was adopted specifically in recognition of

the major issue which bedevils all attempts to produce a BoK: the structuring of the BoK

elements. (People have not too much difficulty agreeing the topics to be put in the BoK

but they have enormous difficulty in dealing with the way these topics are structured -

strange, because one would think it the less important of the two issues, but in reality

reflecting the very great importance people put on the way they address a subject.) The

great advantage of the sunflower is that the regular and symmetrical arrangements of the

BoK elements minimises the difficulty of finding a structure that is acceptable to a wide

range of different national societies.

Peter Morris Page 5 2000

INDECO Ltd – International Management Consultants & Project Managers

IRNOP

Figure 3: "Sunflower" Structure of IPMA Competence Baseline (Version 1)

But why didn’t APM use the PMI BoK models?

If project management is genuinely a professional activity, underpinned by an accepted

body of knowledge, why did APM not use PMI’s Body of Knowledge?

APM’s model was strongly influenced by research then being carried out into the issue of

what it takes to deliver successful projects [4]. The question being asked was, what

factors have to be managed if a project is to be delivered successfully? This is an

important, and difficult, question. It is important because it addresses the question of

what the professional ethos is of project management. Put simply, is it to deliver projects

“on time, in budget, to scope”, as the traditional view has had it [5] or is it to deliver

projects successfully to the project customer/sponsor? In essence it has to be the latter,

because if it is not, project management is a useless profession that in the long-term no

one is going to get very excited about.

Yet all the research evidence [6] shows that in order to deliver successful projects,

managing scope, time, cost, resources, quality, risk, procurement, etc. – the PMI BoK

factors – alone is not enough. Just as important – sometimes more important – are issues

of technology and design management, environmental and external issues, people

matters, business and commercial issues, and so on. Further, the research shows that

defining the project is absolutely central to achieving project success. The job of

managing projects begins early in the project, at the time the project definition is

beginning to be explored and developed, not just after the scope, schedule, budget and

other factors have been defined.

PMI’s BoK dealt insufficiently, it was felt, with these matters. APM thus looked for a

structure which gave more recognition to them.

2. Research updating the APM BoK

While the APM model has worked well over the decade since its formulation, it currently

contains several areas in need of revision. (As, PMI recognises, its BoK does too). Hence

work was initiated in mid 1997 by UMIST’s Centre for Research in the Management of

Projects1 to conduct research aimed at providing empirical data upon which APM could

decide how it wished to update its BoK. The research lasted 14 months and was financed

both by APM and by industry2.

1

CRMP is a leading academic group in project management. Offering three full-time M.Sc.s, it currently

has over a dozen faculty, 50-60 postgraduate students (including about a dozen on research programmes)

and over £1.5million in contracted research

2

The research was funded by APM, AMEC, BNFL, Duhig Berry, GEC (Dunchurch), Unilever, and

Unisys, with additional support from Bechtel.

Peter Morris Page 6 2000

INDECO Ltd – International Management Consultants & Project Managers

IRNOP

The aim of the CRMP work was to:

• identify the topics that project management professionals consider need to be known

and understood by anyone claiming to be competent in project management;

• define what is meant by those topics at a generically useful level;

• update the body of literature that supports these topic areas;

• develop a BoK structure that best represents the revised BoK.

The research findings were based on interviews and data collection in over 117

companies. The findings provide a valuable insight into what practitioners and academics

believe project management professionals ought to be knowledgeable in. It is, we believe,

the only empirical evidence available that does this.

What we found.

Respondents showed considerable agreement on most of the topics that they felt project

management professionals ought to be knowledgeable about. A particularly important

finding is that the survey endorses the breadth of topics in the APM BoK: in fact the

survey results argue for an even broader scope of topics than the original BoK.

Specifically, we found:

• 100% agreed on the need for Leadership, Legal Awareness, Procurement to be

included,

• 99% on Safety Health and Environment,

• 98% on Life Cycles,

• 96% on Purchasing,

• 95% on Risk Management,

• 94% on Financial Management,

• 93% on Industrial Relations and on Scheduling,

• 89% on the Business Case, Project Organisation, and on Testing, Commissioning &

Hand-over,

• 87% on the Project Context,

• 86% on Close-out,

• 85% on Programme Management,

• 84% on Quality Management and on Teamwork,

• 81% on Project Management Plan,

• 80% on (Post-) Project Evaluation Review,

• 79% on Contract Planning and Administration and on Project Management as a

general topic,

• 78% on Monitoring & Control,

• 77% on Resources Management and on Project Launch,

• 75% on Configuration Management and Change Control.

There were a number of topics however that they felt were not necessary, some of which

are surprising and possibly reflect an under-appreciation of the relationship of project

management with the business basis of the project.

Peter Morris Page 7 2000

INDECO Ltd – International Management Consultants & Project Managers

IRNOP

• 28% only agreed on Goals, Objectives and Strategies (surprising considering how

important these are),

• 32% on Requirements Management (ditto),

• 33% on Integrative Management (not surprising: it is covered by Project

Management),

• 36% on Systems Management (not surprising: this has long caused difficulty),

• 42% on Success Criteria (relatively surprising),

• 44% on Performance Measurement – i.e. Earned Value (this is very interesting

considering how central to project management theory and “Best Practice” it is

considered by writers and experts),

• 46% on Information Management.

When the data was split by industry sectors there were some further revealing findings.

• Construction and Information Systems (IS) rated Marketing and Sales 40%, and

Goals, Objectives and Strategies only 20%. This may be a reflection simply of the

jobs/life experience of those who responded. It has a wry correlation however with

the reputation of those industries to concentrate on implementation and less on how to

relate the project to the customer’s real needs.

• Similarly IS rated Requirements Management only 22% - incredible considering (a)

the generally high rate of IS project failures, often associated with poor Requirements

Management and Front-End Definition [7] (b) that the term is particularly associated

with systems projects. (The 32% for Requirements Management in Construction is

more understandable since the term is not well known in Construction.)

• Performance Measurement (Earned Value) scored only 29% in IS too (and 21% in

Facilities Management – high everywhere else): again an interesting comment on the

information systems sector.

The research also compared BoK topics with coverage in The International Journal of

Project Management and the Project Management Journal and with the IPMA and PMI

conference proceedings [8]. In the journals we found that:

• academic writing on the BoK is not even in coverage: there are some topics that have

a huge amount written about them; some have next to nothing. Technical and

commercial issues in particular receive little coverage compared with the traditional

areas of planning and monitoring – i.e. control, organisation, leadership, teamwork,

etc.;

• US coverage of marketing & sales, integrative management, resources, and cost

management is higher than European; European coverage of the early stages of

project formation, the project context, project management plan, project launch and

risk is higher than American.

Coverage in the conferences was broader though still tending to reflect a traditional

implementation orientation.

Peter Morris Page 8 2000

INDECO Ltd – International Management Consultants & Project Managers

IRNOP

The CRMP BoK

Figure 4 shows the final version of the CRMP BoK model

The topics are grouped into seven sections.

• The first section deals with a number of General and introductory items.

The remaining six sections deal with topics to do with managing:

• the project’s Strategic framework, including its basic objectives;

• the Control issues that should be employed;

• the definition of the project’s Technical characteristics;

• the Commercial features of its proposed implementation;

• the Organisation structure that should fit the above;

• issues to do with managing the People that will work on the project.

Peter Morris Page 9 2000

IRNOP

FIGURE 4: THE CRMP BODY OF KNOWLEDGE

Note: This in of course only the BoK structure. The BoK is really this plus the definitions of the topics, together with appropriate references. The BoK can be

obtained from CRMP [0161 200 4590; www.UMIST.ac.UK/CRMP. The CRMP BoK is meant as a research BoK only and is not meant to replace the APM

BoK unless or until APM so decides.

General

1.0 Project Management 3.0 Project Context

2.0 Programme Management

Strategic

4.0 Project Success Criteria 7.0 Risk Management

5.0 Strategy/ Project Management Plan 8.0 Quality Management

6.0 Value Management 9.0 Safety, Health & Environment

Control Technical Commercial Organisational People

10.0 Work Content & 17.0 Design, Production 23.0 Business Case 28.0 Life Cycle Design & 31.0 Communication

Scope Management & Hand -Over 24.0 Marketing & Sales Management 32.0 Teamwork

11.0 Time Scheduling/ Management 25.0 Financial 28.1 Opportunity 33.0 Leadership

Phasing 18.0 Requirements Management 28.2 Design & 34.0 Conflict

12.0 Resource Management 26.0 Procurement Development Management

Management 19.0 Technology 27.0 Legal Awareness 28.3 Production 35.0 Negotiation

13.0 Budgeting & Management 28.4 Hand-over 36.0 Personnel

Cost Management 20.0 Value Engineering 28.5 (Post) Project Management

14.0 Change Control 21.0 Modelling & Evaluation Review

15.0 Earned Value Testing [O&M/ILS]

Management 22.0 Configuration 29.0 Organisation

16.0 Information Management Structure

Management 30.0 Organisational

Roles

Opportunity Design & Production Hand-over Post-Project

Identification Development Evaluation

Design, Test, Operation & Maintenance /

Concept/ Feasibility/ Modelling Make, Build Commission, Integrated Logistics;

Marketing Bid & Procurement & Test Start-up Project Reviews/ Learning

From Experience

Peter Morris Page 10 1999

IRNOP

Areas of significant difference compared with previous versions of the APM BoK [9]

include the following.

• Tighter definition of Success Criteria.

• Value Management split from Value Engineering (because VM is Strategic and

VE is basically Technical/configuration/engineering).

• New emphasis on Technical with several new topics – Design, Production &

Hand-over; Requirements Management; Technology Management; Modelling &

Testing.

• Better description of Procurement.

• Better description of Life Cycle Design and Management.

• Organisational Roles in addition to Organisation Structure.

How valid are the findings?

An important finding of the research is that the breadth of topics was so strongly

endorsed by the empirical data. Though this may comfort the original authors of the

APM BoK, and indeed does fit with the research data on success and failure etc., there

is an obvious word of caution. Since most of those providing data (though not all)

were APM members, they would be biased to accepting the APM BoK view of

project management. A more interesting result would be to find what topics a cross

section of project management professionals thought should be included. Work has

begun on extending the research to incorporate this.

For a long time CRMP resisted proposing any structure at all. For the reasons already

noted, we felt that the important thing was the list of topics to be included and their

textual definition. (And references.) Nevertheless as the research got towards its final

stages, it became clear that most people needed a clear structure by which they could

clearly apprehend the logic of the discipline – its ontology. (Max Wideman reminded

us of the work of the psychologist, Miller, who found in the 1950s that most people

respond best to a numerical structuring scheme of 7, plus or minus 2 [10].)

There are some features underlying the structure of the CRMP BoK that are

particularly important:

• there is a process basis;

• the structure is meant to be as simple and cogent as possible;

• too much should not be read into the actual position of a topic under a heading –

many topics could arguably be put under other headings3.

There was great discussion about whether there should be a “Technical” heading.

Indeed the debate about how much technical knowledge a project manager has to have

is a very old one. We were persuaded of its importance not least by the weight of

research data that shows that technical matters and their management can be major

sources of projects failing to meet their planned requirements.

3

Many Control topics in the CRMP model for example are arguably Strategic; Configuration

Management could have gone under Control, as could Testing. people’s minds). Similarly Value

Management is, in the CRMP BoK, strategic while Value Engineering is technical.

Peter Morris Page 11 1999

IRNOP

The heart of the BoK is in fact the text that describes each of the topics. Use of plain

English has been the objective, both because this is sensible and because this is what

our research showed people very much want. It is not as easy a challenge as it might

sound. Surprisingly, in many ways, there are very few models on which to base such

short, general and yet useful definitions. (Copies of the BoK can be obtained from

CRMP – www.UMIST.ac.co/CRMP – meanwhile APM has agreed to use the CRMP

BoK as the basis for its new BoK which should be released in 2000.)

3. The NASA sponsored enquiry into a Global BoK

Stimulated by the unsatisfactory situation of the project management profession

having two or more different models of the project management Body of Knowledge,

a small group of experts met in Los Angeles in 1998 and agreed that a larger group of

internationally recognised experts should be invited to a workshop to define:

• first, what topics should be included in a project management BoK,

• second, what structure might be employed to represent these topics.

NASA generously agreed to sponsor the experts’ meeting which took place in June

1999 at Norfolk Beach, Virginia.

The exercise was not easy. In a two-day workshop the 33 experts critically reviewed a

list of 703 project management terms that had been culled from the project

management literature and that could form the elements of the BoK. Invitations were

then made for further potential candidate words and the list expanded to 1,000.

Two groups then assembled the lists into two possible BoK structures. One group’s

major headings comprised the following (listed in no particular order):

• Type of Project

• Context

• Client

• Requirements Management

• Strategy

• Project Management Integration

• Planning

• Life Cycle

• Risk

• People

• Procurement

• Control

• Organisation

• Vocabulary

As an illustration of the range and breadth of topics, the following items were

included in “Planning”.

Peter Morris Page 12 1999

IRNOP

Ladder, Lagging, Link, Start to finish SF, Subnet, Late start, Late Finish, Hangar,

Hammock, Early effort, Loop, Node, Calendar, Module, Free float, Re-schedule,

Collapsing, Forecast, Evaluate, PERT activity, CPM Critical path, Float, Latest

Finish, Successor, Flow, Graphical, MOG time, Early start, Start splitting, Arrow

(activity on arrow), Barchart, Biogramming, Split relationship, Finish to start, Work

breakdown structure, Product breakdown structure, Deliverable breakdown structure,

Master schedule, Charter, Network diagram, Strategic Systems Plan (SSP), Synergy,

Methodology, Perimeters, The Value Management, Bills and Methods Matrix,

Crashing, Dangle, Lag, Sub-task, Responsibility Assignment Matrix, Predecessor

Risk Analysis, Quality Assurance, Work Package, Project Plan, Project Planning,

Rolling Wave, Project Execution Plan, Project Implementation Plan, Organisation

Breakdown Structure, Linear Responsibility Chart, Plan, Planning, Manufacturing

Resource Planning (MRP), Dummy, Finish to Finish, Bragnet, Fuzzy Front End,

Dependency Management, Dependency, Total Float, IJ, Start to Start, Levelling, Half

Critical, Duration, Task, Scheduled, Scheduling, Time, Slack, Stage, Phase, M

Milestone, Success, Deliverables Management, Haste, Facts, Assumptions,

Boundaries, Limitations, Cycle time, Staffing, Safety and Health, Quality Control,

Budgeting, Budget, Suppliers, Integrated Supply Chain, Fast Tracking, Estimating,

Problem Solving, Cause and Effect, Date, Lifecycle Costing, Elements, Linear, List,

Network, Breadboarding, GERT, GANTT, Line of Balance ,Tree, Instruction, Chart,

Cost-Benefit, Timing , Tools, Technique, Curve, Rapid Implementation, Decision

making, Decision, Debating , Replanning, Approach, Action, Management Reserve,

Certainty equivalent estimates, Pessimistic, Transition, Sub-project Working, Total,

Manual, Engineer, Informal, Continuous.

The other group’s list was as follows.

Cluster 1 General Management Project Success

Legal Aspects Organisation

Environment Taxonomy

General Terms Program Management

Context

Cluster 2 Start-Up Implementation

Procurement Completion

Cluster 3 Structuring Quality

Scope Modelling

Timing And Schedule Cost

Estimating Risk

Cluster 4 Operations Productions/Operations/

Manufacturing

Cluster 5 Forecast Life Cycle

Project Control Monitoring

Tracking

Cluster 6 Human Aspects Learning

Leadership Teams

Conflict Management

Cluster 7 Technique Documentation

Technology Application Area

Peter Morris Page 13 1999

IRNOP

Note that it was a condition of the exercise that the listing had to be inclusive – if

someone felt that a word was relevant this was to be a potential candidate. And in the

case of the first group, words/topics could appear under more than one heading.

The crucial point, in terms of the history and general work in the development of

BoKs as undertaken so far, and as described above, is the breadth of topics that the

experts considered should be covered in any BoK. As can be seen, the breadth is more

similar to that of the APM, IPMA, CRMP models than the existing PMI BoK. Hence

the PMIBOK™ clearly does not summarise “all those topics etc...that summarise the

application of sound management principles to the management of projects”.

The other important observation to be drawn from the NASA sponsored meeting is

the difficulty everybody still experiences in agreeing a BoK structure. No real attempt

was made at Virginia Beach to begin serious work on a structure but subsequent e-

mail discussions have illustrated clearly the difficulty people have in rationalising a

valid basis for one structure (model/map) over another. One suggestion has been to

perform surveys and computer analyses of “affinities” between topics/words. Whether

such a bottom-up, textual approach would be any more satisfactory than a top-down

structuring based on experience is questionable, but in any event is certainly an

interesting and wholly valid research topic.

The NASA work is continuing, with both virtual team working and a further

workshop planned for 1Q 2000.

4. Benchmarking and the BoKs

Benchmarking is a discipline that enables an organisation continuously to improve –

to continuously identify, understand and creatively evolve superior products, services,

processes and practices. It comprises the activities of:

• identifying items to be benchmarked

• identifying best practices

• understanding the processes behind these

• redesigning and improving the above.

It is widely seen as a critical activity to generating improved performance. It should

be as relevant to the profession of project management as to the companies that

manage projects.

Clearly one of the items that the profession of project management ought to be

comparing, in an attempt to find best models, is that of the Body of Knowledge. The

work described in this paper – past, recent, and current – is important in this regard.

However, given the centrality of the PMI, APM and IPMA BoKs, and their

widespread usage by practitioners, one cannot but wish that such work were

accelerated and given greater support. The importance of the linkage between such

work and standards bodies such as ISO and the various national standards

organisations should also be emphasised. The NASA sponsored work could prove

particularly important, especially if it generates some acceptance at the global level of

professional association coordination.

Peter Morris Page 14 1999

IRNOP

What we should really be benchmarking in the BoKs are the topics; the issue of

structure is much less important. The focus should be on getting agreement on what

the principal topics in the BoK should be, and that the descriptions of these are robust,

accurate and conform to accepted good practice. The 1000 topics identified by the

NASA experts are probably at too detailed a level: interesting in the sense of a

dictionary of terms but too specific for guiding the general reader to the topics with

which a project management practitioner ought, at a minimum, be familiar.

Judging by previous experience, there is a danger that the discussion will dwell too

much on the BoK structure. This cannot be right. Texts on law, say, or medicine or

engineering and similar professions do not insist on there being an agreed ordering of

chapter headings. We are, afterall, talking about a social science construct: there is no

objective, external structure that can be “mapped”. What we are looking for are the

key concepts, techniques, practices and tools, with descriptions/definitions and

guidance to further information (references etc.). The way these topics are combined

is basically what works best for comprehension. Such models will fit different groups’

minds in different ways: arguing over which is best is secondary – almost a luxury.

What is key is ensuring we have the right scope of contents and the right

understanding and guide to knowledge for the topic elements.

The BoK is often thought of as providing guidance to the topics that Best Practice

benchmarking studies should concentrate on. This is not necessarily the case, although

they should be aligned. The BoK topics are those that a project management

practitioner should be knowledgeable in; the benchmarking items are more likely to

be those that lead to improved performance. There is a linkage, not least through the

application of BoK topics as practice areas, but the benchmarking topics will often be

more practice orientated and specific. Ultimately, though, project management as a

profession is going to have show, in much better ways than we are currently able to,

how competency in the formal practices of project management really affect and

improve project performance.

Summary

This paper has reviewed recent and on-going research aimed at identifying what

topics should be included in the project management Body of Knowledge. There

seems to be wide agreement that the scope of topics should be broader than those

currently incorporated in the PMBOK™. The work at CRMP was specifically

focussed on updating the APM BoK. Ongoing work sponsored by NASA is

concerned with the topics to be included in a global BoK. It is suggested that in

general the emphasis should be on defining appropriate topics rather than worrying

overly with the BoK structure.

References

1. Morris, P W G, The Management of Projects, Thomas Telford, 1998.

2. Cook, D L, “Certification of Project Managers – Fantasy or reality?” Project

Management Quarterly 8(2) pp.32-34, 1977

3. Caupin, G, Knopfel, H, Morris, P W G, Motzel, E, Pannenbacker, O, ICB IPMA

Competence Baseline, International Project Management Association, Zurich,

1998

Peter Morris Page 15 1999

IRNOP

4. Morris, P W G, and Hough, G H, The Anatomy of Major Projects, Wiley, 1987;

PMI, Measuring Success, Proceedings of the 1986 Project Management Institute

Seminar/Symposium, Montreal; Pinto, J K and Slevin D P, “Project success:

definitions and measurement techniques” Project Management Journal 19(1) pp.

67- 75, 1989. See also Lim, C S, and Mohamed, M Z, “Criteria of project success:

an exploratory re-examination” International Journal of Project Management

16(4), 1998, pp. 243-248.

5. See for example Archibald, R, Managing High-Technology Programs and

Projects, Wiley, 1997; Meredith, J R, and Mantel, S J, Project Management: A

Managerial Approach” Wiley, 1995; etc.

6. Baker N R, Green S G and Bean A S, “Why R&D projects succeed or fail”

Research Management Nov-Dec 1986 pp. 29-34; Baker N R, Murphy, D C, and

Fisher, D, Determinants of Project Success, National Technical Information

Services N-74-30392, 1974 – see also “Factors affecting Project Success” in

Project Management Handbook Cleland, D I and King, W R, Van Nostrand

Reinhold 1988; Cooper, R G, Winning at New Products, Addison Wesley, 1993;

General Accounting Office: various reports on US defence projects’ performance;

Morris, P W G, op.cit.; National Audit Office: various reports on UK defence

projects’ performance; World Bank Operations Evaluation Department: various

reports on World Bank project performance.

7. Standish Group: see www.standishgroup.com

8. Themistocleous, G, and Wearne, S H., “Project management topic coverage n

journals”, International Journal of Project Management, in publication; Zobel, A

M, and Wearne, S H, “Project management topic coverage in recent conferences”,

paper submitted for publication. (Both available from CRMP.)

9. Morris, P W G, Wearne, S H, and Patel, M.: a series of four articles on the CRMP

BoK in Project, April – July, 1999

10. Miller, G A M, Processing Information, Psychological Review, 63(1), pp. 81-97,

1956

11. Morris, P W G, “Project Management in the Twenty-First Century – Trends

across the Millennium.” Keynote speech, IPMA/Sovnet Congress, Moscow,

September 1999.

Peter Morris Page 16 1999

You might also like

- Project Management Book PDFDocument55 pagesProject Management Book PDFSerigne Mbaye Diop94% (16)

- Project Management Body of KnowledgeDocument5 pagesProject Management Body of KnowledgeYael LevíNo ratings yet

- PMBOK For DummiesDocument18 pagesPMBOK For Dummiesingeamv100% (1)

- Front Office Executive - KRA & KPI - Example-13.05.2019Document4 pagesFront Office Executive - KRA & KPI - Example-13.05.2019Vinodkanna R100% (1)

- Communications Plan and TemplateDocument6 pagesCommunications Plan and TemplateBrittani Bell100% (1)

- Project Management StandardsDocument18 pagesProject Management Standardschandcs2000No ratings yet

- Research Updating The APM Body of Knowledge 4th Edition: Project ManagementDocument13 pagesResearch Updating The APM Body of Knowledge 4th Edition: Project ManagementTomasz WiatrNo ratings yet

- What Is Project Management?: Project Management-A Managerial Approach, 1995, by Jack R. Meredith and Samuel J. Mantel JRDocument28 pagesWhat Is Project Management?: Project Management-A Managerial Approach, 1995, by Jack R. Meredith and Samuel J. Mantel JREnes DenizdurduranNo ratings yet

- Development and Comparative Analysis of The Project Management Bodies of KnowledgeDocument6 pagesDevelopment and Comparative Analysis of The Project Management Bodies of KnowledgeGeorge PereiraNo ratings yet

- Project Management Paper - 131010 Ver 01Document5 pagesProject Management Paper - 131010 Ver 01Abubaker Sami AliNo ratings yet

- PMBOK 6th EditionDocument6 pagesPMBOK 6th EditionLuz GiraldoNo ratings yet

- PMF TextbookDocument154 pagesPMF TextbookFabian GomezNo ratings yet

- 01-03 Framework (PMP 6)Document139 pages01-03 Framework (PMP 6)Ahmed AshrafNo ratings yet

- PM-00-Introductory SessionDocument11 pagesPM-00-Introductory SessionHesam XYNo ratings yet

- 1.PM1 PmbokDocument12 pages1.PM1 Pmbokn jhaNo ratings yet

- Project Management Is Not NewDocument2 pagesProject Management Is Not NewQueen ValleNo ratings yet

- 1.PM1 - PMBOKDocument12 pages1.PM1 - PMBOKn jhaNo ratings yet

- Project Management: HistoryDocument13 pagesProject Management: Historyadeel rafiqNo ratings yet

- Intro To Pmbok PDFDocument3 pagesIntro To Pmbok PDFLaurence SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Enhance PMBOK® by Comparing It With P2M, ICB, PRINCE2, APM and Scrum Project Management StandardsDocument77 pagesEnhance PMBOK® by Comparing It With P2M, ICB, PRINCE2, APM and Scrum Project Management Standardssriram84No ratings yet

- Minggu Ke 2-Pengenalan Kepada Pengurusan ProjekDocument20 pagesMinggu Ke 2-Pengenalan Kepada Pengurusan ProjekNur'Aina Farhana NorzelanNo ratings yet

- Project Management - Session 1 PPT C1QaoR7cBgDocument58 pagesProject Management - Session 1 PPT C1QaoR7cBgHriday AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Assessing and Moving On From The Dominant Project Management Discourse in The Light of Project OverrunsDocument12 pagesAssessing and Moving On From The Dominant Project Management Discourse in The Light of Project OverrunsFarid KaskarNo ratings yet

- Project Management Principles Applied in Academic Research ProjectsDocument16 pagesProject Management Principles Applied in Academic Research ProjectsMuteeb KhanNo ratings yet

- P2M Promoted by PMAJDocument8 pagesP2M Promoted by PMAJOnofrei AndreiNo ratings yet

- The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) : Get The PDF VersionDocument7 pagesThe Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) : Get The PDF VersionIram HabibNo ratings yet

- Project Management Institute:: Analysis On The Role of Standardized Project Management On Project PerformanceDocument24 pagesProject Management Institute:: Analysis On The Role of Standardized Project Management On Project PerformanceAli MalikNo ratings yet

- Comparison of PM FrameworksDocument77 pagesComparison of PM Frameworkstico1_200067% (3)

- ICB - IPMA Competence Baseline Version 3.0Document212 pagesICB - IPMA Competence Baseline Version 3.0alex_parra100% (1)

- Overview of PM 20-01-2018Document59 pagesOverview of PM 20-01-2018Asad SaleemNo ratings yet

- CMP - Ref - Ipma - Icb3 v3.0Document212 pagesCMP - Ref - Ipma - Icb3 v3.0Kamel GuenatriNo ratings yet

- Mankon 01Document36 pagesMankon 01joseNo ratings yet

- Project Supervision and AdministratioinDocument17 pagesProject Supervision and AdministratiointaridanNo ratings yet

- Project Management Institute PyramidDocument4 pagesProject Management Institute PyramidsangeethNo ratings yet

- Subject Name: Operation ManagementDocument29 pagesSubject Name: Operation ManagementDhaval BhandariNo ratings yet

- TheLogicalFrameworkApproach MillenniumDocument15 pagesTheLogicalFrameworkApproach MillenniumBirhanuNo ratings yet

- Pmbok Guide Underneath The SurfaceDocument90 pagesPmbok Guide Underneath The Surfacealinakakaif100% (2)

- 01 C1-C2 Project Management For Entrepreneurs v03Document57 pages01 C1-C2 Project Management For Entrepreneurs v03Georgiana IlieNo ratings yet

- Integrated Project Control ID AgendaDocument8 pagesIntegrated Project Control ID Agendaody anjarNo ratings yet

- Ipma Icbv3 UsDocument212 pagesIpma Icbv3 Usinformarcio10No ratings yet

- Value & Risk ManagementDocument204 pagesValue & Risk ManagementlucioprovenzaniNo ratings yet

- 2 5237981465244871054 PDFDocument13 pages2 5237981465244871054 PDFاميرة الشمريNo ratings yet

- PMP Training Success GuideDocument32 pagesPMP Training Success GuidePrajaktaNo ratings yet

- 1: The Concept of Project ManagementDocument14 pages1: The Concept of Project ManagementAhmed SaigolNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Project Management: Unit 1: Chapter 1Document241 pagesIntroduction To Project Management: Unit 1: Chapter 1Vaibhav Bahel100% (1)

- w1 - Introduction To Sustainable Project ManagementDocument213 pagesw1 - Introduction To Sustainable Project ManagementAmanu PramonoNo ratings yet

- Vaskimo-Projektinhallinnan Metodologiat PDFDocument35 pagesVaskimo-Projektinhallinnan Metodologiat PDFBela Ulicsak100% (1)

- Project Management Competence For The New MilleniumDocument5 pagesProject Management Competence For The New MilleniumKannan PkNo ratings yet

- NL1 Introduction To Course ContentDocument24 pagesNL1 Introduction To Course ContentMikaelAdnanNo ratings yet

- Project Management Body PDFDocument3 pagesProject Management Body PDFRodrigo H Bustos MNo ratings yet

- Manajemen Konstruksi Lanjut (TM1)Document16 pagesManajemen Konstruksi Lanjut (TM1)kinoyNo ratings yet

- MGT471 - IPM - Course OutlineDocument6 pagesMGT471 - IPM - Course OutlineSRUTISMITA PATTANAIKNo ratings yet

- PMP 1Document46 pagesPMP 1Abdl Rahman GaberNo ratings yet

- CM651 Proj MGT Module 1 (061916)Document34 pagesCM651 Proj MGT Module 1 (061916)Rei Mark CoNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document14 pagesUnit 1Ahmed HeibaNo ratings yet

- Project Management Is TheDocument15 pagesProject Management Is TheBhargav NaiduNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S026378631630120X MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S026378631630120X MaingrkorosidisNo ratings yet

- Project Management ISO 21500-2012 KonermagDocument75 pagesProject Management ISO 21500-2012 KonermagerlanggaNo ratings yet

- Getting Started with Project Management: Managing Projects in Small BitesFrom EverandGetting Started with Project Management: Managing Projects in Small BitesNo ratings yet

- PROJECT MONITORING AND EVALUATION- A PRIMER: Every Student's Handbook on Project M & EFrom EverandPROJECT MONITORING AND EVALUATION- A PRIMER: Every Student's Handbook on Project M & ENo ratings yet

- 1.02 Stakeholder RegisterDocument1 page1.02 Stakeholder Registerpilar gamaNo ratings yet

- Global PM Competency Standards Status Report November 2001Document6 pagesGlobal PM Competency Standards Status Report November 2001pilar gamaNo ratings yet

- Partner TocDocument3 pagesPartner Tocpilar gamaNo ratings yet

- IPMbrochure2012 13Document34 pagesIPMbrochure2012 13pilar gamaNo ratings yet

- Site - Iugaza.edu - Ps Aschokry Files 2011 09 Introduction ToOperations and Production Management Chap 11Document32 pagesSite - Iugaza.edu - Ps Aschokry Files 2011 09 Introduction ToOperations and Production Management Chap 11Sana BhittaniNo ratings yet

- Article 6 - Differences Between A RFI RFQ and RFPDocument1 pageArticle 6 - Differences Between A RFI RFQ and RFPSibusiso Buthelezi100% (1)

- An Introduction To System Analysis and DesignDocument55 pagesAn Introduction To System Analysis and DesignedflookeNo ratings yet

- Requirement AnalysisDocument3 pagesRequirement AnalysisRohit ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Architectures Chapter 04Document9 pagesEnterprise Architectures Chapter 04palakNo ratings yet

- A20 Midterm ReviewerDocument2 pagesA20 Midterm ReviewerEy EmNo ratings yet

- Required Curriculum - MBA - Harvard Business SchoolDocument4 pagesRequired Curriculum - MBA - Harvard Business SchoolJerryJoshuaDiazNo ratings yet

- CH 10 AuditingDocument31 pagesCH 10 AuditingPutri Ayu Dwi LestariNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Test ProcessDocument4 pagesFundamental Test ProcessKamir ShahbazNo ratings yet

- GE - Nine CellDocument12 pagesGE - Nine CellNikita SangalNo ratings yet

- Total Quality Management Question PaperDocument4 pagesTotal Quality Management Question Papervpsravi67% (3)

- 5 Strategy Generation and SelectionDocument55 pages5 Strategy Generation and SelectionAhmad EkoNo ratings yet

- Eight P's in Marketing TourismDocument2 pagesEight P's in Marketing TourismInés PerazzaNo ratings yet

- U of A: Emergency Response RecommendationsDocument7 pagesU of A: Emergency Response RecommendationsEmily MertzNo ratings yet

- Project Initiation To CompletionDocument4 pagesProject Initiation To CompletionjesusgameboyNo ratings yet

- Role of Doctors and Nurses in Material MDocument1 pageRole of Doctors and Nurses in Material MPrakash kumar gourNo ratings yet

- 1030 Stephen Brobst Semantic Data ModelingDocument16 pages1030 Stephen Brobst Semantic Data ModelinghaiderabbaskhattakNo ratings yet

- Talent Mgt.Document37 pagesTalent Mgt.UMAMA UZAIR MIRZANo ratings yet

- Kra (Key Resulted Area) Based Incentice Scheme: Part - I To Be Filled by Human Resource DepartmentDocument8 pagesKra (Key Resulted Area) Based Incentice Scheme: Part - I To Be Filled by Human Resource DepartmentShivaramvarma MandapatiNo ratings yet

- 00 - 39 - 32 Earned Value Management PMP Exam Questions - MilestoneTaskDocument8 pages00 - 39 - 32 Earned Value Management PMP Exam Questions - MilestoneTaskLucky EdjenekpoNo ratings yet

- 7 SCM WastesDocument9 pages7 SCM WastesUswatun MaulidiyahNo ratings yet

- Maintainability Analysis.Document14 pagesMaintainability Analysis.Mary GwimileNo ratings yet

- NCE100 Gold Book PDFDocument60 pagesNCE100 Gold Book PDFAnonymous kRIjqBLkNo ratings yet

- Presentation of Le Mans UniversityDocument18 pagesPresentation of Le Mans UniversityTempus WebsitesNo ratings yet

- Transaction CyclesDocument2 pagesTransaction CyclesAdan NadaNo ratings yet

- Collaborative Planning, Forecasting & Replenishment (CPFR)Document16 pagesCollaborative Planning, Forecasting & Replenishment (CPFR)Seema HaloiNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Management at Accenture: Katia Arrus Jonathan Hayes Cristian Orellana Jay Bashucky Suresh JayaramanDocument38 pagesKnowledge Management at Accenture: Katia Arrus Jonathan Hayes Cristian Orellana Jay Bashucky Suresh JayaramannarcisalotruNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management ScorecardDocument11 pagesSupply Chain Management ScorecardAjay Kumar100% (1)