Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Insurance EGOS 2011

Insurance EGOS 2011

Uploaded by

Francesca CabidduCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Progressive Final PaperDocument16 pagesProgressive Final PaperJordyn WebreNo ratings yet

- Recruitment of Advisors in IciciDocument77 pagesRecruitment of Advisors in Icicipadamheena123No ratings yet

- Presentation of Hexagon Composites: Patrick Breuer Hannover, 26 April 2016Document23 pagesPresentation of Hexagon Composites: Patrick Breuer Hannover, 26 April 2016homer4No ratings yet

- Talonen Et Al, 2021 Mutual InsuranceDocument21 pagesTalonen Et Al, 2021 Mutual InsuranceΜάκης ΣαλασίδηςNo ratings yet

- Maas 2010Document20 pagesMaas 2010JuanCamiloGonzálezTrujilloNo ratings yet

- The European Insurance Industry: A PEST Analysis: Financial StudiesDocument20 pagesThe European Insurance Industry: A PEST Analysis: Financial StudiesAnonymous fRXyPY3No ratings yet

- Go Policy (Insurance Broker) : Student's Name: Student's Id: Date: Word Count: 2000Document12 pagesGo Policy (Insurance Broker) : Student's Name: Student's Id: Date: Word Count: 2000Mayur SoNo ratings yet

- The European Insurance Industry: A PEST Analysis: ReviewDocument20 pagesThe European Insurance Industry: A PEST Analysis: ReviewSheena GarciaNo ratings yet

- Accepted Date: 29 April 2018 To Cite This Document: Reschiwati, & Solikhah, R. P. (2018) - Random Effect ModelDocument17 pagesAccepted Date: 29 April 2018 To Cite This Document: Reschiwati, & Solikhah, R. P. (2018) - Random Effect Modelolivio yudarajatNo ratings yet

- The Insurance Agents'competencies As The Determinant of Efficiency of Life Insurance Companies - Relationship ApproachDocument10 pagesThe Insurance Agents'competencies As The Determinant of Efficiency of Life Insurance Companies - Relationship ApproachAndrzejDRNo ratings yet

- Insurance Accounting and Finance: Lecture#4 by Dr. Muhammad UsmanDocument8 pagesInsurance Accounting and Finance: Lecture#4 by Dr. Muhammad UsmanNoor MahmoodNo ratings yet

- L ReviewDocument18 pagesL ReviewMia SmithNo ratings yet

- General Insurance Marketing: A Review and Future Research AgendaDocument19 pagesGeneral Insurance Marketing: A Review and Future Research AgendasiddheshNo ratings yet

- Discussion Papers: Analysing The Determinants of Credit Risk For General Insurance Firms in The UKDocument43 pagesDiscussion Papers: Analysing The Determinants of Credit Risk For General Insurance Firms in The UKnely coniNo ratings yet

- Sariga.s - Insurance PresentationDocument13 pagesSariga.s - Insurance PresentationSasi KumarNo ratings yet

- Chapter - Iv Profitability Analysis of Indian Life Insurance IndustryDocument30 pagesChapter - Iv Profitability Analysis of Indian Life Insurance IndustryJenni PennyworthNo ratings yet

- Structure, Development and Actuarial Valuation of Unit-Linked Policies in Life InsuranceDocument55 pagesStructure, Development and Actuarial Valuation of Unit-Linked Policies in Life InsuranceRiccardo EspositoNo ratings yet

- Synopsis PHD Pacific UniversityDocument24 pagesSynopsis PHD Pacific UniversityanupmidNo ratings yet

- Profitability Determinants of The Insurance Sector in Small Pacific Island StatesDocument15 pagesProfitability Determinants of The Insurance Sector in Small Pacific Island Stateshoshyjoshy2001No ratings yet

- Broking Ops 1Document9 pagesBroking Ops 1MM MMNo ratings yet

- Risk Management With Help of InsuranceDocument22 pagesRisk Management With Help of InsuranceKurosaki IchigoNo ratings yet

- Iffco Tokio General Insurance CompanyDocument9 pagesIffco Tokio General Insurance CompanyShauvik GhoshNo ratings yet

- Topic Role of Private Players in Insurance SectorDocument13 pagesTopic Role of Private Players in Insurance SectorNandini JaganNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: D. Ramkumar (2003)Document7 pagesLiterature Review: D. Ramkumar (2003)ManthanNo ratings yet

- Chapter One 1.1 Background of The StudyDocument10 pagesChapter One 1.1 Background of The StudyAaron YakubuNo ratings yet

- 4.-Capítulo 2 - Productivity - and - Performance - in - InsuranceDocument9 pages4.-Capítulo 2 - Productivity - and - Performance - in - InsuranceCisco AlvarezNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Reinsurance For Insurance CompaniesDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Reinsurance For Insurance CompaniesAnwar AdemNo ratings yet

- 1311 Remuneration Structures Study en 0Document187 pages1311 Remuneration Structures Study en 0Andrei SavvaNo ratings yet

- 800 Assignment MethodologyofresearchDocument7 pages800 Assignment Methodologyofresearchrgaherwal098No ratings yet

- The Research On The Insurance Industry's Tax Burden in China Under The Background of Change From Business Tax To VATDocument16 pagesThe Research On The Insurance Industry's Tax Burden in China Under The Background of Change From Business Tax To VATAncuta AncutzaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Interest Rate On Profit of Insurance Companies in NigeriaDocument15 pagesEffect of Interest Rate On Profit of Insurance Companies in NigeriaTopArt Tân BìnhNo ratings yet

- A Usa Grenee Sfa 2004Document33 pagesA Usa Grenee Sfa 2004ridwanbudiman2000No ratings yet

- Insurance FINAL PDFDocument14 pagesInsurance FINAL PDFArushi SinghNo ratings yet

- In Sur SymposiumDocument30 pagesIn Sur Symposiumtsioney70No ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Unsaved 1Document5 pagesChapter 3 Unsaved 1Karan MistryNo ratings yet

- Insurance Company ThesisDocument7 pagesInsurance Company Thesisdwt5trfn100% (2)

- Chapter-Ii Review of Literature and Research MethodologyDocument30 pagesChapter-Ii Review of Literature and Research MethodologyRidhima KatiyarNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument22 pagesDocument PDFMahedrz Gavali100% (1)

- Akbar Imp ProjectDocument32 pagesAkbar Imp ProjectAkbar AliNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Factors Affecting The Performance of Insurance Companies in ZimbabweDocument21 pagesAn Analysis of Factors Affecting The Performance of Insurance Companies in ZimbabweTroden MukwasiNo ratings yet

- CSR Project On InsuranceDocument69 pagesCSR Project On Insurancedhwani0% (1)

- International Review of Financial Analysis: Hala Abdul Kader, Mike Adams, Philip Hardwick, W. Jean KwonDocument3 pagesInternational Review of Financial Analysis: Hala Abdul Kader, Mike Adams, Philip Hardwick, W. Jean KwonTrisna Taufik DarmawansyahNo ratings yet

- Do Financial Experts On The Board Matter? An Empirical Test From The United Kingdom's Non-Life Insurance IndustryDocument28 pagesDo Financial Experts On The Board Matter? An Empirical Test From The United Kingdom's Non-Life Insurance IndustryCorolla SedanNo ratings yet

- Solvency 2Document8 pagesSolvency 2Daniel MateiNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument24 pagesArticleRituNo ratings yet

- Effectof Claims Paymenton ProfitabilityDocument8 pagesEffectof Claims Paymenton Profitabilitymercymoses102No ratings yet

- Marketing Techinques of Ing Vysya Life InsuranceDocument16 pagesMarketing Techinques of Ing Vysya Life InsurancethiagujtrNo ratings yet

- Finacial Performance of Life InsuracneDocument24 pagesFinacial Performance of Life InsuracneCryptic LollNo ratings yet

- Project On Web Based Application For Insurance ServicesDocument54 pagesProject On Web Based Application For Insurance ServicesNnamdi Chimaobi64% (11)

- International Journal For Research in Business, Management and Accounting ISSN: 2455-6114Document18 pagesInternational Journal For Research in Business, Management and Accounting ISSN: 2455-6114Shafici AliNo ratings yet

- P6Document6 pagesP6pardeshikanchan07No ratings yet

- R L L I - W H B D W N B D ?: Esearch On Apse in IFE Nsurance HAT AS EEN One and HAT Eeds TO E ONEDocument28 pagesR L L I - W H B D W N B D ?: Esearch On Apse in IFE Nsurance HAT AS EEN One and HAT Eeds TO E ONE3rlangNo ratings yet

- 175 Spigarska, MajerowskaDocument11 pages175 Spigarska, MajerowskaRadek PolonusNo ratings yet

- 19438role CA InsuranceDocument4 pages19438role CA InsuranceThaneesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Tiner Insurance ReportDocument44 pagesTiner Insurance ReportNikhil FatnaniNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 IntroductionDocument6 pagesCHAPTER 1 IntroductionPrerana AroraNo ratings yet

- Chaneel Case ArticleDocument6 pagesChaneel Case ArticleMangipudi SeshagiriNo ratings yet

- Impact of Liberlisation On The Insurance IndustryDocument46 pagesImpact of Liberlisation On The Insurance IndustryParag MoreNo ratings yet

- When Insurers Go Bust: An Economic Analysis of the Role and Design of Prudential RegulationFrom EverandWhen Insurers Go Bust: An Economic Analysis of the Role and Design of Prudential RegulationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Risk Management: How to Use Different Insurance to Your BenefitFrom EverandRisk Management: How to Use Different Insurance to Your BenefitNo ratings yet

- Sustainability and Financial Risks: The Impact of Climate Change, Environmental Degradation and Social Inequality on Financial MarketsFrom EverandSustainability and Financial Risks: The Impact of Climate Change, Environmental Degradation and Social Inequality on Financial MarketsMarco MigliorelliNo ratings yet

- Globalisation A2Document7 pagesGlobalisation A2Angel AngelNo ratings yet

- Alain de Botton - On Arguing More NakedlyDocument5 pagesAlain de Botton - On Arguing More NakedlyFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Automatic Plaster MachineDocument4 pagesAutomatic Plaster MachineIJMTST-Online JournalNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledapi-1549565660% (1)

- Resume ExampleDocument1 pageResume ExampleK I0NNo ratings yet

- SAT Final Database AlpaDocument261 pagesSAT Final Database AlpagowthamNo ratings yet

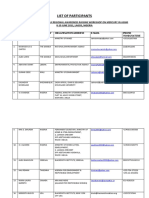

- Final List of Participants NigeriaDocument9 pagesFinal List of Participants NigeriaEtolo SoroNo ratings yet

- Thesis Report On BreastfeedingDocument7 pagesThesis Report On Breastfeedingiinlutvff100% (2)

- 3D Sex and Zen Extreme Ecstasy 2011Document77 pages3D Sex and Zen Extreme Ecstasy 2011kalyscoNo ratings yet

- Jesus of Levi and JudahDocument40 pagesJesus of Levi and JudahAntony Hylton100% (1)

- L A 1 L A 2 (PERSONAL LETTER) Devrina OliviaDocument9 pagesL A 1 L A 2 (PERSONAL LETTER) Devrina OliviaVina RohmatikaNo ratings yet

- Charles LyellDocument10 pagesCharles LyellNHNo ratings yet

- Jaydapinketsmithenwissam AvanzadoremiDocument6 pagesJaydapinketsmithenwissam AvanzadoremiGysht HwuNo ratings yet

- 1 Aloandro Ben Bakr - BeatrizDocument1 page1 Aloandro Ben Bakr - BeatrizDavid DayNo ratings yet

- Combined Knitting Conversion TableDocument1 pageCombined Knitting Conversion TableKatarina Ivic-UcovicNo ratings yet

- Investment Pattern Amongst The Residents of Navi Mumbai PGDM 2011-13Document35 pagesInvestment Pattern Amongst The Residents of Navi Mumbai PGDM 2011-13Ishu Rungta تNo ratings yet

- Your Morrisons ReceiptDocument2 pagesYour Morrisons ReceiptRegina Vivian BarliNo ratings yet

- Laroche Landscaping Has Collected The Following Data For The December PDFDocument1 pageLaroche Landscaping Has Collected The Following Data For The December PDFhassan taimourNo ratings yet

- IET Automotive Cyber-Security TLR LR PDFDocument16 pagesIET Automotive Cyber-Security TLR LR PDFPanneerselvam KolandaivelNo ratings yet

- Article Critique Opm 633Document5 pagesArticle Critique Opm 633Fatin AqilahNo ratings yet

- Internal Scraper ComparisonDocument11 pagesInternal Scraper ComparisonHarshGuptaNo ratings yet

- CS615-MidTerm MCQs With Reference Solved by ArslanDocument16 pagesCS615-MidTerm MCQs With Reference Solved by ArslanHabib AhmedNo ratings yet

- Hellbound, The Blood WarDocument256 pagesHellbound, The Blood WarErick SebrianNo ratings yet

- YSR Navasakam Social Audit Survey Format For Fee ReimbursementDocument1 pageYSR Navasakam Social Audit Survey Format For Fee ReimbursementManohar DattNo ratings yet

- Architectural Heritage Course Outline. 2021. by Biniam SHDocument2 pagesArchitectural Heritage Course Outline. 2021. by Biniam SHYe Geter Lig NegnNo ratings yet

- Application Form For Electrical Wiremen Competency To Work (Exemption) Grant or Renewal Form "A"Document2 pagesApplication Form For Electrical Wiremen Competency To Work (Exemption) Grant or Renewal Form "A"RAHUL KumarNo ratings yet

- NiCad Trans 11 - A03Document4 pagesNiCad Trans 11 - A03danielliram993No ratings yet

- The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus by Christopher MarloweDocument8 pagesThe Tragical History of Doctor Faustus by Christopher MarloweJOSUE BARRIOSNo ratings yet

- Dialogues in The RestaurantDocument2 pagesDialogues in The RestaurantZsuzsa SzékelyNo ratings yet

Insurance EGOS 2011

Insurance EGOS 2011

Uploaded by

Francesca CabidduOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Insurance EGOS 2011

Insurance EGOS 2011

Uploaded by

Francesca CabidduCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Sub-theme 53: Dynamics and Change in and between Organizations

The impact of organizational transformation on the relationship between the insurance agents and the company

FRANCESCA CABIDDU Researcher of Management University of Cagliari, Facolty of Economics Viale S. Ignazio, 74 070/6753382 fcabiddu@unica.it

MARIA CHIARA DI GUARDO Professor of Organization Theory University of Cagliari, Facolty of Economics Viale S. Ignazio, 74 070/6753360 diguardo@unica.it

The impact of organizational transformation on the relationship between the insurance agents and the company Introduction Insurance organizations in Italy have changed radically and deeply in the past twenty years. Deregulation, globalization of insurance institutions, intensified competition, electronic commerce, and the emergence of new risks are among the challenges faced by insurance organizations. Among the most important changes that are affecting the Italian insurance market it is important to emphasize the peculiar role played by the Law n. 40/2007 (the socalled "Riforma Bersani"), which came into force on January 1st, 2008 and dramatically changed the long-term relationships between insurance companies, and customers by repealing a previous clause regarding exclusive agents in the field of non-life insurance sector1. In fact, the Law n. 40/2007 establishes the professional figure of independent agent (or, an independent seller working for more than one insurance company at the same time) whom, unlike exclusive agents, is entitled for insurance distribution in the behalf of each single firm he represents, thus revoking previous agreements between insurance companies and exclusive agents. Considering the fact that among all the working insurance agents in Italy (about 22.600) exclusivity has always been the main characteristic underlying agency relations while a mere 8.4% of them, in 2007, were independent agents (multifirm agents) it is easy to assume that after the coming into force of the Law n. 40/2007 a whole organization transformation is set for both insurance companies and agents, with new competitive challenges regarding the re-planning of the relationships inside the organizations. This paper provides an exploratory analysis of insurance organization transformation following the introduction of the opportunity for the Italian insurance agents to represent more than one insurance company at the same time through a multiple players relations model (Suarez F.F., 2005; Cook K.S., 1977; Katz M., Shapiro C., 1985). This change involves the creation of new disciplinary regimes that produce new kinds of structures of work organization inside the insurance sector in Italy. Based on the detailed study of one of the insurance division of the Allianz Group (Allianz-Lloyd Adriatico) and her company (Allianz S.P.A.), one of the biggest insurance company in Italy and in Europe, our paper tackles this

1

The insurance industry consists of the non-life insurance sector and the life insurance sector. The value of the market is shown in terms of gross premium incomes. The life insurance market consists of mortality protection and retirement savings plans. The non-life insurance market consists of accident and health, and property and casualty insurance segments.

issue with an unprecedented richness of data. The objective is to considers how organizational insurance transformation can be explained and in doing so the paper fits with the sub-theme Organizational Transformation: Power, Resistance and Identity. The principals-agents-customers relations: Problem description The traditional relationship between the insurance agent and the insurance company can be described as a typical principal-agent relationship (Holmstrom, and Milgrom, 1987) as the one drawn in the agency theory. The agency theory focuses on the analysis of the relationship between a principal and an agent, where the principal asks an agent for satisfying the principals demands or, in general, for performing a certain act and rewarding the agent for taking negotiating effectively on his behalf. The survival and the success of an agency relation depends on the principals ability to establish a set of rules which can control and promote the agents' activities, but also relies on the principal's ability to coordinate the team work and to adopt efficient strategies and effective policies. The costs of an agency relation might arise from diverging interests between the principal and the agent, and from the need of a set of obligations (which may be implicit agreements) establishing rules and incentives, consequently avoiding moral hazard. The principal, therefore, should aim to stipulate a contract which maximizes his own expected utility while meeting and satisfying the interests of the agent, motivating him to comply with honor the contractual agreements through a system of incentives and penalties. Before the Law Bersani took effect, what characterized the relationship between the insurance agent and the insurance company could have been effectively represented using the agency theory scheme, insofar as it was mainly a relation between two 'subjects': the principal (dealer), or the insurance company in the behalf of whom the local agency is run by; and the insurance agent, who works permanently in a professional and autonomous way to provide at his own risk and operating expenses for the administration and management of the agency's business, paid completely or partially on commission. The abolition of exclusive sales contracts in the field of non-life insurances has deep consequences in agency relations, because it dramatically changes the balance between the actors involved, therefore requiring a transformation of both the companies' and the agents' competitive strategies. As a result, the peculiar relationship that is established between the agent and the insurance companies in such a system, cannot allow an analysis of the relationship based simply on the results accomplished by agency theory, but requires the use

3

of a different model, the common agency one, that allows us to study the multipart relationship established between several principals and one agent, as well as the relationships established between different principals. Each agent can establish a relation with more principals (with the latter becoming direct competitors as a result), and each company may get in touch with new agents who previously worked -or currently work- for other companies, and who are potentially dynamic, innovative and interested in increasing the number of their collaboration agreements. Methods Research design Given the nature of this type of research, a case study methodology is appropriate. In fact, the qualitative case study approach is particularly useful when concepts and contexts are not well defined because it enables in-depth understanding and explanation (Eisenhardt, 1989). In particular, a case study is as an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within a real-life context, especially when the boundaries between the phenomena and the context are not clearly defined (Yin, 2003) . Research setting The Allianz Group is one of the leading integrated financial services providers worldwide. With approximately 152,000 employees worldwide, the Allianz Group serves approximately 75 million customers in about 70 countries. On the insurance side, Allianz is the market leader in the German market and has a strong international presence. In fiscal 2009 the Allianz Group achieved total revenues of over 97.4 billion euros. Allianz is also one of the world's largest asset managers, with third-party assets of 926 billion euros under management at year end 2009. Lloyd Adriatico is a division of the Allianz Group. Lloyd Adriatico led by Enrico Tomaso Cucchiani. Lloyd Adriatico, in the last years, was able to transfer to its customers the savings obtained from improved efficiency. The motor third party liability (TPL) costs for customers without accidents were reduced and further cuts are expected in the coming months. Savings can reach 30 percent on motor TPL and 85% on fire and theft.

Also in life business, the creation of value for customers was testified by the excellent performances of all Lloyd Adriatico investment lines and the ability to avoid the negative impact of the several crises that hit the financial markets. Data collection We collected data through phone interviews, observations, and secondary sources. The primary source was semi-structured interviews with individual respondents (manager of Allianz S.P.A and insurance agents). 275 interviews were conducted over the telephone between July and October 2008, and between July and September 2010. All agents were located in Italy. We described the topic of the research to each participant before the interview. Participants were told that their responses would be kept confidentially. To conduct the semi-structured interviews, one common protocols were adopted. The protocol was employed for the interviews administered to Allianz S.p.A. managers. We structured this protocol as follow: In the first part of the protocol, a number of questions concerning the role of the interviewee were asked; in the second part, we asked questions regarding the relationship between the company and the insurance agents. Interviews lasted from 1 hour to 2 hours. All interviews were recorded and the recordings were transcribed. Interview transcripts were verified for accuracy by the managers. Each transcript was analyzed immediately following the interview and used as a basis to explore emerging themes in subsequent interviews. We collected also demographic information from insurance agents. Among the insurance agents, 91 percent were male, and 51 percent of them were aged 36 to 49 years old; 33 percent had an age ranging from 50 to 60; while 8 percent were over 60 years old. Finally, 8% were under 35. 60 percent of the insurance agents sample was from Northern Italy, 25 percent from the South and Islands and 15 percent from Central Italy. Follow-up interviews were conducted with several managers to verify themes that emerged in subsequent interviews. A literature search was conducted in tandem with data collection and analysis in order to ground the analysis theoretically. Data analysis The first question, aimed at understanding the agents evaluation (be it positive or negative) of the early effects of the insurance market reform (Bersani law), gave the following

5

results: more than half of agents (55%) assessed the effects of reform as positive, 13% of respondents said that the effects of the reform were negative and, finally, 32% of respondents claimed they didnt know how to evaluate, to date, the real implications of the reform.

The second question, logically related to the first, sought to focus attention on the agent's intention to become a multi-firm agent. 17% of respondents said they had already become multi-firm, 8% said they would become multi-firm during the year. Finally, 32% of the agents, more than one third of the total, said they would remain one-firm. The unsure were 43% of the total. The leading obstacle to become multi-firm agent is the lack of understanding of the opportunities and threats related to this law.

Interesting information can be obtained by comparing these results with those collected three years ago, by administering to the same agents, a questionnaire aimed at understanding their opinions before the introduction of the Bersani Law. The number of agents who have chosen to become multi-firm agent is lower than the statements they made three years ago (17% versus 33%). There was, however, a slight increase in agents' determination to maintain a one-firm (now 28% against 33% in the past). The adoption barriers that agents face most are managerial and cultural rather than those related to the Bersani Law. The third question was aimed at understanding whether the agent had given their firm sales network the opportunity to become a multi-firm agent, developing what can be considered a "hidden" multi-firm agreement. In fact, 20% of respondents said that they had access to other mandates through their sales network. The mandates obtained by the sales network were mainly related to the auto industry, and in a very limited number to retail and corporate damage. The fourth question was aimed to understand if the agent considered the opportunity given to their sales network was perceived positively. The result was surprising. 43% firmly believed that the above mentioned opportunity was an advantage for both agents and sales network. On the other hand, 57% stated that it was a risky decision. They once again clearly pointed out their uncertainty towards the effects of Bersani law.

As concerns the interest expressed by other companies to acquire the Allianz sale network, 68% of agents stated that they were contacted by different companies (Aviva, Axa, Navale, Cattolica, Carige, Zurich, Sara, Reale mutua, Tua, Vittoria). In spite of this, few agents accepted to become multi-firm agents because they were uncertain about the advantages of this choice. This uncertainty was the same that they had shown during the previously administered questions. They seemed to be afraid of leaving the certainty of their present relationship with their company.

The above mentioned fear to change their present relationship was also expressed by the fact that 78% of the agents declared that they had not taken any action to become multi-firm agents. They showed little interest in acquiring new mandates.

Despite their reluctance to become multi-firm agents, they manifest interest when asked : in what sector would you like to receive offers from other companies. They predominantly chose the automobile sector that was followed by requests for the retail claims and specialist corporate ones. Another question concerned their thoughts about the possibility that a multi-firm agreement could have had major management costs. Only 14% of the sample believed that the Bersani reform had determined only major costs such as management cost, training etc., and expressed their negative perception about the multi-firm agreement. Once again, more than 55% of the sample expressed their inability to evaluate the opportunities given by multi-firm agreement. This result is in line with the high level of those that were uncertain (43% of the total) with the choice of multi-firm agreement.

10

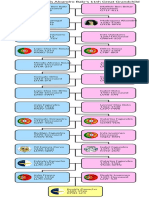

Very interesting is the view of the agents who believed that become multi-firm agent had brought benefits. The statements provided by one multi-firm agent are quite meaningful in this sense: The multi-firm agreement allows you to operate in the best of ways, this creates an advantage for your clients and for you. If through an exclusive mandate only 3 out of 10 contacts become customers, under the multi-firm agreement the percentage rises to 7 or 10. Findings Our findings are based on a sample of instances of Allianz S.p.A. mangers and insurance agents. As with any research study of this scope and complexity, our work has limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results. The bulk of our data is in the form of responses to interviews. In order to limit the impact of this single form of data, and to be able to triangulate our findings, we elicited multiple relevant perspectives in each organization. Moreover, when possible we corroborated the interview data with observations or follow up requests for specific information. Our first finding consisted in identifying the evolution from the traditional principal-agent model to a many-to-many relationship model between multiple agents and multiple companies- consequently re-establishing a balance in the relationship between agents and companies (figure 1). In fact, companies might discriminate against agents or discourage them in their choices, in order to preserve their sales network exclusiveness, or simply to promote policies that maximize expected utility.

10

11

Fig. 1 - Principals-agents-customers relations

Insurance Company

Insurance Company

Insurance Company

Agent (seller) Agent (seller )

Agent (seller ) Agent (seller)

Agent (seller )

Custo

Custo mer

mer

Custo mer

Custo mer

Secondly, we found that the customer compare and evaluate different products from the different companies the chosen agent works with: in this way, while of course it impossible for the agent to compare all the different products available on the market, he is nonetheless able to advise his customers in a more accurate way. Also, the relationship between customer and agent is not affected by the relationship between the different companies and the agent because the latter has a wider range of offers and, therefore, choose in a less constrained way. This competition should be assessed not only as regarding exclusively the final market, but also concerning the possible connections that an agent can establish with insurance companies, thus setting a number of multiple players relations (Suarez F.F., 2005; Cook K.S., 1977; Katz M., Shapiro C., 1985). The agents in fact, taking into account the changes brought to competition by the abolition of the clause on exclusivity, cannot be considered as separate and independent from each other. All the possible different ways of relating to insurance companies that each agent will choose,

11

12

have a direct and immediate effect on the different competitive options available to all the other players in the system. Actually, it is important for the agent to know if there are other multi-mandatory agents that sell the same policies for the same insurance companies in its own geographical area, especially to assess his possible positioning within that market. Moreover, the decisions and choices made by the majority of other agents working for the same company (even though in different geographical areas) will influence the agent's own decisions Future research can investigate the relationship with the customer. In particular, it would be interesting to understand whether the agents have incentives to place products or policies which are best suited for a certain customer, or if they choose those that are more profitable for him. These can happen because customers might find it difficult to properly assess and compare different products that offer different quality and coverage level. In addition, it would be interesting to understand if the agents could have difficulty to meet the demands made by different companies (this can happen, for example, when companies ask the agent to adopt the same criteria for clients' selection). Another topic that should be analized is the number of mandates that an agent is able to handle. . Discussion and conclusion Our model shows how insurance organization transformation are tied to externalities: in fact, each single agent is strongly influenced by the way in which all the other players that belong to the (same) system behave. Each agent, in fact, has to define a strategy that takes into account the possible choices other agent can opt for, and in particular they have to consider carefully the choices made by agents that belong to their same sales network and agency. Going further in detail, they face two alternatives: they can try to define a strategy aimed to maximize their utility, regardless of what others decide; or, they can opt for a solution that minimize losses that might be caused by other competitors or any relevant decision maker. As a matter of fact, opting for a multi-mandatory scheme can be rewarding not only for the intrinsic qualities and the opportunities it offers, but also depending on which and how other agents have already opted in (or are willing to do so): for sometimes it can be more profitable to choose for the option that is apparently -at least from a strategic point of view- less favorable, but is more profitable for the single depending on the other players' behavior and choices.

12

13

As for insurance companies, they have to implement strategies directed towards loyalty building within their agencies sales network, eventually choosing to assess alternative sales networks, depending on their competitive positioning. In general, network externality weakens the strength of the mechanism that leads to opt for the best per se choice. Furthermore, agents externality leads to the definition of strong and weak ties. Two actors that belong to the same system, depending on the multiple player model adopted, can interact with each other either rarely, or extremely often. Applying this model to agents, there is a difference between the bindings that occur among agents belonging to the same agency network, and the weaker ones (generally based on mere competition): the first example is about strong bonds, while the latter exemplifies a weak bond. Inevitably, agents will give significant weight to strong bonds when choosing between different options, being therefore particularly influenced by this type of bonds. In other words, the fact that agents can be strongly influenced by other agents' choices might suggest that opting for a multi-mandatory scheme or not might be biased in favor of the choice made by the agents belonging to the same agency network, and not only on the choice made by the majority of the agents in general. The strength of the bond depends on the frequency of the contacts between players: in brief, the probability of an agent choosing to broaden his offering from other insurance companies (within a multi-mandatory agreement) depends on the number of other agents with whom he has established strong bonds who are willing to opt for his same choice. In fact, numerous researches have proved that as uncertainty within competitors increase, together with a growing complexity of the information available, the more strong bonds will bias the strategic choices of the players involved (Hansen, 1999). The same happens with insurance companies: they communicate with each other, observe each other and, in some cases, adopt imitative behaviors. Nevertheless, there can be strong or weak ties also between insurance companies (Suarez, 2005; Cook, 1977; Kraatz, 1998). References Marvel, Howard, 1982, Exclusive Dealing, Journal of Law and Economics, 25: 1-25. Grossman, Sanford and Oliver Hart, 1986, The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration, Journal of Political Economy, 94: 691-719.

13

14

Sass, Tim and Micha Gisser, 1989, Agency Costs, Firm Size, and Exclusive Dealing, Journal of Law and Economics, 32: 381- 400. Alchian A., Demsetz, H., Production , Information Costs, and Economic Organization, American Economic Review, vol. 62(5), pages 777-95, Dicembre, 1972. Cook K.S., Exchange and power in networks of interorganizational relationships, Sociological Quarterly, vol. 18, 1977. David P., Common Agency contracting and the emergence of open science institutions, American Economic Review, vol. 88, 1998. Dixit A., Grossman G., Helpman E., Common agency and coordination: General theory and application to government policy making, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 105, 1997. Eisenhardt, K. M. Building theories from case study research, Academy of Management Review 14, (1989): 488-511.Fraysse J., Common Agency: Exsistence of an equilibrium in the casa of two outcomes, Econometrica, vol. 61, 1993. Garen J.E., Executive Compensation and Principal-Agent Theory, The Journal of Political Economy, vol. 102, 1994. Holmstrom B., Milgrom P., Multitask Principal-Agent Analyses: Incentive Contracts, Asset Ownership, and Job Design, Journal of Law, Economics & Organization, vol. 7, 1991. Han S., Menu theorems for bilateral contracting problems, University of Toronto, working paper 2002. Hansen B., Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference, Journal of Econometrics, Elsevier, vol. 93(2), pages 345-368, 1999. Holmstrom, B. and Milgrom P. 1987. "Aggregation and Linearity in the Provision of Intertemporal Incentives," 55 Econometrica 303-28. Jensen M., Meckling W., Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs, and Ownership Structure, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 3, Nr. 4, 1976. Katz M., Shapiro C., Network externalities, competition and compatibility, American Economic Review, vol. 75, 1985. Martimort D., Exclusive dealing, common agency, and multiprincipals incentive theory, Rand Journal of Economics, vol. 27, 1996. Pavan, A., Calzolari G., A Markovian revelation principle for common agency games, Northwestern University Discussion Paper, 2001. Peters M., Pure strategy and no-externalities with multiple agents, Economic Theory, vol. 23, 2004.

14

15

Prat 2000.

A.,

Rustichini

A.,

Games

played

through

agents.

http://econ.lse.ac.uk/staff/prat/papers/mn00-7- 18.pdf, London School of Economics, WP, Rodriguez G.E., On the value of information in the presence of moral hazard, Review of Economic Design, vol. 10, 2007. Ross S.A., The Economic Theory of Agency: The Principals Problem, American Economic Review, vol. 63, 1973. Suarez F.F., Network Effects Revisited: The Role Of Strong Ties In Technology Selection, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 48, 2005. Yin, R. K. 1984. Case Study Research, Design and Methods, Beverly Hills, CA,Sage Publications.

15

You might also like

- Progressive Final PaperDocument16 pagesProgressive Final PaperJordyn WebreNo ratings yet

- Recruitment of Advisors in IciciDocument77 pagesRecruitment of Advisors in Icicipadamheena123No ratings yet

- Presentation of Hexagon Composites: Patrick Breuer Hannover, 26 April 2016Document23 pagesPresentation of Hexagon Composites: Patrick Breuer Hannover, 26 April 2016homer4No ratings yet

- Talonen Et Al, 2021 Mutual InsuranceDocument21 pagesTalonen Et Al, 2021 Mutual InsuranceΜάκης ΣαλασίδηςNo ratings yet

- Maas 2010Document20 pagesMaas 2010JuanCamiloGonzálezTrujilloNo ratings yet

- The European Insurance Industry: A PEST Analysis: Financial StudiesDocument20 pagesThe European Insurance Industry: A PEST Analysis: Financial StudiesAnonymous fRXyPY3No ratings yet

- Go Policy (Insurance Broker) : Student's Name: Student's Id: Date: Word Count: 2000Document12 pagesGo Policy (Insurance Broker) : Student's Name: Student's Id: Date: Word Count: 2000Mayur SoNo ratings yet

- The European Insurance Industry: A PEST Analysis: ReviewDocument20 pagesThe European Insurance Industry: A PEST Analysis: ReviewSheena GarciaNo ratings yet

- Accepted Date: 29 April 2018 To Cite This Document: Reschiwati, & Solikhah, R. P. (2018) - Random Effect ModelDocument17 pagesAccepted Date: 29 April 2018 To Cite This Document: Reschiwati, & Solikhah, R. P. (2018) - Random Effect Modelolivio yudarajatNo ratings yet

- The Insurance Agents'competencies As The Determinant of Efficiency of Life Insurance Companies - Relationship ApproachDocument10 pagesThe Insurance Agents'competencies As The Determinant of Efficiency of Life Insurance Companies - Relationship ApproachAndrzejDRNo ratings yet

- Insurance Accounting and Finance: Lecture#4 by Dr. Muhammad UsmanDocument8 pagesInsurance Accounting and Finance: Lecture#4 by Dr. Muhammad UsmanNoor MahmoodNo ratings yet

- L ReviewDocument18 pagesL ReviewMia SmithNo ratings yet

- General Insurance Marketing: A Review and Future Research AgendaDocument19 pagesGeneral Insurance Marketing: A Review and Future Research AgendasiddheshNo ratings yet

- Discussion Papers: Analysing The Determinants of Credit Risk For General Insurance Firms in The UKDocument43 pagesDiscussion Papers: Analysing The Determinants of Credit Risk For General Insurance Firms in The UKnely coniNo ratings yet

- Sariga.s - Insurance PresentationDocument13 pagesSariga.s - Insurance PresentationSasi KumarNo ratings yet

- Chapter - Iv Profitability Analysis of Indian Life Insurance IndustryDocument30 pagesChapter - Iv Profitability Analysis of Indian Life Insurance IndustryJenni PennyworthNo ratings yet

- Structure, Development and Actuarial Valuation of Unit-Linked Policies in Life InsuranceDocument55 pagesStructure, Development and Actuarial Valuation of Unit-Linked Policies in Life InsuranceRiccardo EspositoNo ratings yet

- Synopsis PHD Pacific UniversityDocument24 pagesSynopsis PHD Pacific UniversityanupmidNo ratings yet

- Profitability Determinants of The Insurance Sector in Small Pacific Island StatesDocument15 pagesProfitability Determinants of The Insurance Sector in Small Pacific Island Stateshoshyjoshy2001No ratings yet

- Broking Ops 1Document9 pagesBroking Ops 1MM MMNo ratings yet

- Risk Management With Help of InsuranceDocument22 pagesRisk Management With Help of InsuranceKurosaki IchigoNo ratings yet

- Iffco Tokio General Insurance CompanyDocument9 pagesIffco Tokio General Insurance CompanyShauvik GhoshNo ratings yet

- Topic Role of Private Players in Insurance SectorDocument13 pagesTopic Role of Private Players in Insurance SectorNandini JaganNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: D. Ramkumar (2003)Document7 pagesLiterature Review: D. Ramkumar (2003)ManthanNo ratings yet

- Chapter One 1.1 Background of The StudyDocument10 pagesChapter One 1.1 Background of The StudyAaron YakubuNo ratings yet

- 4.-Capítulo 2 - Productivity - and - Performance - in - InsuranceDocument9 pages4.-Capítulo 2 - Productivity - and - Performance - in - InsuranceCisco AlvarezNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Reinsurance For Insurance CompaniesDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Reinsurance For Insurance CompaniesAnwar AdemNo ratings yet

- 1311 Remuneration Structures Study en 0Document187 pages1311 Remuneration Structures Study en 0Andrei SavvaNo ratings yet

- 800 Assignment MethodologyofresearchDocument7 pages800 Assignment Methodologyofresearchrgaherwal098No ratings yet

- The Research On The Insurance Industry's Tax Burden in China Under The Background of Change From Business Tax To VATDocument16 pagesThe Research On The Insurance Industry's Tax Burden in China Under The Background of Change From Business Tax To VATAncuta AncutzaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Interest Rate On Profit of Insurance Companies in NigeriaDocument15 pagesEffect of Interest Rate On Profit of Insurance Companies in NigeriaTopArt Tân BìnhNo ratings yet

- A Usa Grenee Sfa 2004Document33 pagesA Usa Grenee Sfa 2004ridwanbudiman2000No ratings yet

- Insurance FINAL PDFDocument14 pagesInsurance FINAL PDFArushi SinghNo ratings yet

- In Sur SymposiumDocument30 pagesIn Sur Symposiumtsioney70No ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Unsaved 1Document5 pagesChapter 3 Unsaved 1Karan MistryNo ratings yet

- Insurance Company ThesisDocument7 pagesInsurance Company Thesisdwt5trfn100% (2)

- Chapter-Ii Review of Literature and Research MethodologyDocument30 pagesChapter-Ii Review of Literature and Research MethodologyRidhima KatiyarNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument22 pagesDocument PDFMahedrz Gavali100% (1)

- Akbar Imp ProjectDocument32 pagesAkbar Imp ProjectAkbar AliNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Factors Affecting The Performance of Insurance Companies in ZimbabweDocument21 pagesAn Analysis of Factors Affecting The Performance of Insurance Companies in ZimbabweTroden MukwasiNo ratings yet

- CSR Project On InsuranceDocument69 pagesCSR Project On Insurancedhwani0% (1)

- International Review of Financial Analysis: Hala Abdul Kader, Mike Adams, Philip Hardwick, W. Jean KwonDocument3 pagesInternational Review of Financial Analysis: Hala Abdul Kader, Mike Adams, Philip Hardwick, W. Jean KwonTrisna Taufik DarmawansyahNo ratings yet

- Do Financial Experts On The Board Matter? An Empirical Test From The United Kingdom's Non-Life Insurance IndustryDocument28 pagesDo Financial Experts On The Board Matter? An Empirical Test From The United Kingdom's Non-Life Insurance IndustryCorolla SedanNo ratings yet

- Solvency 2Document8 pagesSolvency 2Daniel MateiNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument24 pagesArticleRituNo ratings yet

- Effectof Claims Paymenton ProfitabilityDocument8 pagesEffectof Claims Paymenton Profitabilitymercymoses102No ratings yet

- Marketing Techinques of Ing Vysya Life InsuranceDocument16 pagesMarketing Techinques of Ing Vysya Life InsurancethiagujtrNo ratings yet

- Finacial Performance of Life InsuracneDocument24 pagesFinacial Performance of Life InsuracneCryptic LollNo ratings yet

- Project On Web Based Application For Insurance ServicesDocument54 pagesProject On Web Based Application For Insurance ServicesNnamdi Chimaobi64% (11)

- International Journal For Research in Business, Management and Accounting ISSN: 2455-6114Document18 pagesInternational Journal For Research in Business, Management and Accounting ISSN: 2455-6114Shafici AliNo ratings yet

- P6Document6 pagesP6pardeshikanchan07No ratings yet

- R L L I - W H B D W N B D ?: Esearch On Apse in IFE Nsurance HAT AS EEN One and HAT Eeds TO E ONEDocument28 pagesR L L I - W H B D W N B D ?: Esearch On Apse in IFE Nsurance HAT AS EEN One and HAT Eeds TO E ONE3rlangNo ratings yet

- 175 Spigarska, MajerowskaDocument11 pages175 Spigarska, MajerowskaRadek PolonusNo ratings yet

- 19438role CA InsuranceDocument4 pages19438role CA InsuranceThaneesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Tiner Insurance ReportDocument44 pagesTiner Insurance ReportNikhil FatnaniNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 IntroductionDocument6 pagesCHAPTER 1 IntroductionPrerana AroraNo ratings yet

- Chaneel Case ArticleDocument6 pagesChaneel Case ArticleMangipudi SeshagiriNo ratings yet

- Impact of Liberlisation On The Insurance IndustryDocument46 pagesImpact of Liberlisation On The Insurance IndustryParag MoreNo ratings yet

- When Insurers Go Bust: An Economic Analysis of the Role and Design of Prudential RegulationFrom EverandWhen Insurers Go Bust: An Economic Analysis of the Role and Design of Prudential RegulationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Risk Management: How to Use Different Insurance to Your BenefitFrom EverandRisk Management: How to Use Different Insurance to Your BenefitNo ratings yet

- Sustainability and Financial Risks: The Impact of Climate Change, Environmental Degradation and Social Inequality on Financial MarketsFrom EverandSustainability and Financial Risks: The Impact of Climate Change, Environmental Degradation and Social Inequality on Financial MarketsMarco MigliorelliNo ratings yet

- Globalisation A2Document7 pagesGlobalisation A2Angel AngelNo ratings yet

- Alain de Botton - On Arguing More NakedlyDocument5 pagesAlain de Botton - On Arguing More NakedlyFabián BarbaNo ratings yet

- Automatic Plaster MachineDocument4 pagesAutomatic Plaster MachineIJMTST-Online JournalNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledapi-1549565660% (1)

- Resume ExampleDocument1 pageResume ExampleK I0NNo ratings yet

- SAT Final Database AlpaDocument261 pagesSAT Final Database AlpagowthamNo ratings yet

- Final List of Participants NigeriaDocument9 pagesFinal List of Participants NigeriaEtolo SoroNo ratings yet

- Thesis Report On BreastfeedingDocument7 pagesThesis Report On Breastfeedingiinlutvff100% (2)

- 3D Sex and Zen Extreme Ecstasy 2011Document77 pages3D Sex and Zen Extreme Ecstasy 2011kalyscoNo ratings yet

- Jesus of Levi and JudahDocument40 pagesJesus of Levi and JudahAntony Hylton100% (1)

- L A 1 L A 2 (PERSONAL LETTER) Devrina OliviaDocument9 pagesL A 1 L A 2 (PERSONAL LETTER) Devrina OliviaVina RohmatikaNo ratings yet

- Charles LyellDocument10 pagesCharles LyellNHNo ratings yet

- Jaydapinketsmithenwissam AvanzadoremiDocument6 pagesJaydapinketsmithenwissam AvanzadoremiGysht HwuNo ratings yet

- 1 Aloandro Ben Bakr - BeatrizDocument1 page1 Aloandro Ben Bakr - BeatrizDavid DayNo ratings yet

- Combined Knitting Conversion TableDocument1 pageCombined Knitting Conversion TableKatarina Ivic-UcovicNo ratings yet

- Investment Pattern Amongst The Residents of Navi Mumbai PGDM 2011-13Document35 pagesInvestment Pattern Amongst The Residents of Navi Mumbai PGDM 2011-13Ishu Rungta تNo ratings yet

- Your Morrisons ReceiptDocument2 pagesYour Morrisons ReceiptRegina Vivian BarliNo ratings yet

- Laroche Landscaping Has Collected The Following Data For The December PDFDocument1 pageLaroche Landscaping Has Collected The Following Data For The December PDFhassan taimourNo ratings yet

- IET Automotive Cyber-Security TLR LR PDFDocument16 pagesIET Automotive Cyber-Security TLR LR PDFPanneerselvam KolandaivelNo ratings yet

- Article Critique Opm 633Document5 pagesArticle Critique Opm 633Fatin AqilahNo ratings yet

- Internal Scraper ComparisonDocument11 pagesInternal Scraper ComparisonHarshGuptaNo ratings yet

- CS615-MidTerm MCQs With Reference Solved by ArslanDocument16 pagesCS615-MidTerm MCQs With Reference Solved by ArslanHabib AhmedNo ratings yet

- Hellbound, The Blood WarDocument256 pagesHellbound, The Blood WarErick SebrianNo ratings yet

- YSR Navasakam Social Audit Survey Format For Fee ReimbursementDocument1 pageYSR Navasakam Social Audit Survey Format For Fee ReimbursementManohar DattNo ratings yet

- Architectural Heritage Course Outline. 2021. by Biniam SHDocument2 pagesArchitectural Heritage Course Outline. 2021. by Biniam SHYe Geter Lig NegnNo ratings yet

- Application Form For Electrical Wiremen Competency To Work (Exemption) Grant or Renewal Form "A"Document2 pagesApplication Form For Electrical Wiremen Competency To Work (Exemption) Grant or Renewal Form "A"RAHUL KumarNo ratings yet

- NiCad Trans 11 - A03Document4 pagesNiCad Trans 11 - A03danielliram993No ratings yet

- The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus by Christopher MarloweDocument8 pagesThe Tragical History of Doctor Faustus by Christopher MarloweJOSUE BARRIOSNo ratings yet

- Dialogues in The RestaurantDocument2 pagesDialogues in The RestaurantZsuzsa SzékelyNo ratings yet