Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3 Consumer Choice

3 Consumer Choice

Uploaded by

Gretel MinayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3 Consumer Choice

3 Consumer Choice

Uploaded by

Gretel MinayaCopyright:

Available Formats

Consumer Choice

4-1 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Individual preferences determine the satisfaction people

derive from the goods and services they consume

Consumers face constraints or limits on their choices,

particularly because their budgets limit how much they can

buy.

Consumers seek to maximize the level of satisfaction they

obtain from consumption subject to the constraints they

face (“do the best with what they have”).

4-2 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.1 Consumer Preferences

A consumer faces choices involving many goods and must allocate his or

her available budget to buy a bundle of goods.

Would ice cream or cake make a better dessert? Is it better to rent a

large apartment or rent a single room and use the savings to pay for

concerts?

How do consumers choose the bundles of goods they buy?

One possibility is that consumers behave randomly and blindly choose

one good or another without any thought.

Another is that they make systematic choices.

To explain consumer behavior, economists assume that consumers have

a set of tastes or preferences that they use to guide them in choosing

between goods.

4-3 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.1 Consumer Preferences

Properties of Consumer Preferences

Completeness

When a consumer faces a choice between any two bundles of goods,

only one of the following is true. The consumer might prefer the first

bundle to the second, or the second bundle to the first, or be

indifferent between the two bundles. Indifference is allowed, but

indecision is not.

Transitivity

If a is strictly preferred to b and b is strictly preferred to c, it follows

that a must be strictly preferred to c. Transitivity applies also to weak

preference and indifference relationships.

More is better

All else being the same, more of a good is better than less. This is a

nonsatiation property.

4-4 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.1 Consumer Preferences

Preference Maps

A preference map is a complete set of indifference curves that summarize

a consumer’s tastes.

An indifference curve is the set of all bundles of goods that a

consumer views as being equally desirable.

Panel c of Figure 4.1 shows three of Lisa’s indifference curves: I1, I2,

and I3. In this figure, the indifference curves are parallel, but they

need not be.

Preferences and Indifference Curves

Bundles on indifference curves farther from the origin are preferred to

those on indifference curves closer to the origin.

There is an indifference curve through every possible bundle.

Indifference curves cannot cross.

Indifference curves slope downward.

4-5 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.1 Consumer Preferences

Figure 4.1 Bundles

of Pizzas and

Burritos That Lisa

Might Consume

4-6 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Figure 4.2 Impossible

Indifference Curves

4-7 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.1 Consumer Preferences

Willingness to Substitute Between Goods

The Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS) is the rate at which a

consumer is willing to substitute one good for another while remaining on

the same indifference curve.

Lisa’s marginal rate of substitution of burritos for pizza is MRS = ∆B/∆Z,

where ∆B is the number of burritos Lisa will give up to get ∆Z more

pizzas while staying on the same indifference curve.

The indifference curves are convex or “bowed in” toward the origin. This

willingness to trade fewer burritos for one more pizza reflects a

diminishing marginal rate of substitution.

Curvature of Indifference Curves

Convex indifference curves reflect imperfect substitutes.

Straight-line indifferences curves reflect perfect substitutes, goods that are

essentially equivalent for the consumer.

Right-angle indifference curves reflect perfect complements, goods

consumed only in fixed proportions.

4-8 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.1 Consumer Preferences

Figure 4.3 Marginal Rate of Substitution

4-9 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.1 Consumer Preferences

Figure 4.4 Perfect Substitutes, Perfect

Complements, Imperfect Substitutes

4-10 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.2 Utility

Utility Functions

Our consumer behavior model assumes that consumers can compare

bundles of goods and take the one with the greatest satisfaction.

If we knew the utility function—the relationship between utility measures

and every possible bundle of goods—we could summarize the information

in indifference maps succinctly.

𝑈(𝐵, 𝑍)

Ordinal and Cardinal Utility

Ordinal utility if we know only a consumer’s relative rankings of bundles.

Cardinal utility if we know absolute numerical comparisons.

Most of our discussion of consumer choice here holds if utility has only

ordinal properties. We care only about the relative utility or ranking of the

two bundles.

4-11 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.2 Utility

Marginal Utility (MU)

Marginal utility is the slope of the utility function as we hold the quantity

of the other good constant, MUZ = ∆U/∆Z.

Lisa’s marginal utility from increasing her consumption of pizza from 4

to 5 in Figure 4.5 is MUZ = ∆U/∆Z = 20/1 = 20

Marginal Rates of Substitution (MRS)

The MRS depends on the negative of the ratio of the marginal utility of

one good to the marginal utility of another good.

Lisa’s MRS depends on the negative of the ratio of the MU of pizza to

the MU of burritos, MRS = - MUZ/MUB

𝑀𝑈𝑍 𝛥𝑍 + 𝑀𝑈𝐵 𝛥𝐵 = 0

𝑀𝑈𝐵 𝛥𝐵 = −𝑀𝑈𝑍 𝛥𝑍

𝛥𝐵 𝑀𝑈𝑍

=−

𝛥𝑍 𝑀𝑈𝐵

4-12 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.2 Utility

Figure 4.5 Utility

and Marginal Utility

4-13 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.3 The Budget Constraint

Consumers maximize their well-being subject to constraints, and the most

important is the budget constraint.

The budget constraint or budget line shows the bundles of goods that

can be bought if the entire budget is spent on those goods at given

prices.

Lisa’s budget constraint is pBB + pZZ = Y, where pBB and pZZ are the

amounts she spends on burritos and pizzas.

4-14 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

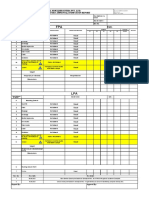

Table 4.1 Allocations of a $50 Budget

Between Burritos and Pizza

If pZ = $1, pB = $2, and Y = $50,

4-15 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.3 The Budget Constraint

Figure 4.6 Budget Line

4-16 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Table 4.1 Allocations of a $50 Budget

Between Burritos and Pizza

The opportunity set is all the bundles a consumer can buy, including all

the bundles inside the budget constraint and on the budget constraint.

The opportunity set are all those bundles of positive Z and B such

that pBB + pZZ Y.

Slope of the Budget Line

It is determined by the relative prices of the two goods and is called the

marginal rate of transformation (MRT = -pZ/pB)

Lisa’s MRT = -1/2. She can “trade” an extra pizza for half a burrito or

give up two pizzas to obtain an extra burrito.

4-17 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.3 The Budget Constraint

Effects of a Change in Price on the Opportunity Set

If the price of pizza doubles but the price of burritos is unchanged, the

budget line swings in toward the origin.

The new budget line is steeper and lies inside the original one. Unless Lisa

only wants to eat burritos, she is unambiguously worse off, she can no

longer afford the combinations of pizza and burritos in the shaded “Loss”

area.

Effects of a Change in Income on the Opportunity Set

If the consumer’s income increases, the consumer can buy more of all

goods.

A change in income affects only the position and not the slope of the

budget line.

If Lisa’s income increases and relative prices do not change, her budget

line shifts outward (away from the origin) and is parallel to the original

constraint.

4-18 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.3 The Budget Constraint

Figure 4.7 Changes in the Budget Line

4-19 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.4 Constrained Consumer Choice

The Consumer’s Optimal Bundle

The optimal bundle must lie on an indifference curve that touches

the budget line but does not cross it.

There are two ways to reach this outcome, interior and corner

solutions.

4-20 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.4 Constrained Consumer Choice

Interior Solutions

An interior solution occurs when the optimal bundle has positive quantities

of both goods and lies between the ends of the budget line.

Bundle e on indifference curve I2 is the optimum interior solution.

4-21 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.4 Constrained Consumer Choice

The Consumer’s Optimal Bundle

Consumer’s utility is maximized at the bundle where the rate at which she

is willing to trade the two goods equals the rate at which she can trade:

Rearranging the terms

Thus, consumer’s utility is maximized if the last dollar she spends on good

gets her as much extra utility as the last dollar she spends on the other

good.

4-22 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.4 Constrained Consumer Choice

Corner Solutions

A corner solution occurs when the optimal bundle is at one end of the

budget line, where the budget line forms a corner with one of the axes.

Bundle e on indifference curve I2 is a corner solution.

4-23 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.4 Constrained Consumer Choice

Promotions

Managers induce consumers to buy more units with promotions. The two most used

are buy one, get one free (BOGOF) and buy one, get the second at a half price.

Buy One, Get One Free Promotion(BOGOF)

The BOGOF promotion creates a kink in the budget line and its acceptance depends

on the shape of the indifference curves.

In Figure 4.10, with the BOGOF promotion “buy 3 nights, get the 4th free” the

new budget line is L2 for both Angela and Betty.

In panel a, without the promotion, Angela’s indifference curve I1 is tangent to L1

at point x, so she chooses to spend two nights at the resort. With the BOGOF

promotion, her indifference curve I1 cuts the new budget line L2. There’s a

higher indifference curve, I2, that touches L2 at point y, where she chooses to

stay four nights.

In panel b, without the promotion, Betty chooses to stay two nights at x where

her indifference curve I3 is tangent to L1. Because I3 does not cut the new

budget line L2, no higher indifference curve can touch L2, so Betty stays only

two nights, at x, and does not take advantage of the BOGOF promotion.

4-24 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.4 Constrained Consumer Choice

Figure 4.10 BOGOF Promotion

4-25 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.4 Constrained Consumer Choice

BOGOF versus a Half-Price Promotion

Consumers accept BOGOF promotions only if the pre-promotion

indifference curve crosses the new budget line. However, BOGOF does not

work will all consumers.

A half-price promotion may be more effective than BOGOF if a manager

can design a promotion such that consumers’ indifference curves must

cross the new budget line so that consumers will definitely participate.

In Figure 4.11, the BOGOF budget line is L2 but Betty’s original

indifference curve, I3 does not cross L2, so she will not take advantage

of the BOGOF promotion. However, because I3 crosses the half-price

promotion budget line L3, Betty takes advantage of it. Betty’s optimal

bundle is y to stays three nights, which is located where her

indifference curve I4 is tangent to the half-price promotion line L3.

4-26 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.4 Constrained Consumer Choice

Figure 4.11 Half-Price Versus BOGOF

Promotions

4-27 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

4.5 Deriving Demand Curves

We use consumer theory to show how much the quantity demanded of a

good falls as its price rises.

An individual chooses an optimal bundle of goods by picking the point on

the highest indifference curve that touches the budget line.

In panel a of Figure 4.12 , e1 is the highest indifference curve that

touches L1

A change in price causes the budget line to rotate, so that the consumer

chooses a new optimal bundle.

In panel a of Figure 4.12, a price change from £2 to £1 makes the

budget line to rotate from L1 to L2. The new optimal bundle is e2.

By varying one price and holding other prices and income constant, we

determine how the quantity demanded changes as the price changes,

which is the information we need to draw the demand curve.

In panel b of Figure 4.12, E1, E2 and E3 are the points of the demand

curve derived from price changes, budget lines and indifference

curves in panel a.

4-28 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Deriving an Individual’s Demand

Curve

4-29 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Price-Consumption Curve

The price-consumption curve

(PCC) traces the set of optimal

bundles on an indifference

curve map as the price of one

good varies (holding income

and other prices constant).

If the price-consumption

curve is downward sloping,

the two goods can be

considered substitutes.

If the price-consumption

curve is upward sloping,

the two goods can be

considered complements.

4-30 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Income-Consumption Curve

The income-consumption

curve (ICC) traces the set of

optimal bundles on an

indifference curve map as

income varies (holding all

prices constant).

If the income-consumption

curve is upward sloping,

the good is normal.

If the income-consumption

curve is downward sloping,

the good is inferior.

4-31 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Engel Curve

The Engel curve plots the

relationship between

quantity demanded and the

income.

If the Engel curve is

upward sloping

Normal good.

If the Engel curve is

downward sloping

Inferior good.

4-32 © 2018 Pearson Education, Ltd. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Economics 11th Edition Michael Parkin Solutions Manual 1Document29 pagesEconomics 11th Edition Michael Parkin Solutions Manual 1jackqueline100% (49)

- Project Title:: Checklist For PlasteringDocument2 pagesProject Title:: Checklist For Plasteringalfie100% (6)

- Possibilites, Preferences, and Choices: Answers To The Review QuizzesDocument16 pagesPossibilites, Preferences, and Choices: Answers To The Review QuizzesWeko CheangNo ratings yet

- Exercises Chapter 3Document21 pagesExercises Chapter 3Katia Ibrahim100% (1)

- BCA ECR Documentation Fase IIIDocument70 pagesBCA ECR Documentation Fase IIIliko anas setyawatiNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics and Strategy: Third EditionDocument37 pagesManagerial Economics and Strategy: Third EditionNanthakumar SubramanianNo ratings yet

- Indifference Curves and Utility Maximization: 6 AppendixDocument19 pagesIndifference Curves and Utility Maximization: 6 AppendixPrashantNo ratings yet

- Economics 11Th Edition Michael Parkin Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesEconomics 11Th Edition Michael Parkin Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFjoshua.king500100% (11)

- Consumer Choice: Answers To Textbook QuestionsDocument7 pagesConsumer Choice: Answers To Textbook Questions蔡杰翰No ratings yet

- ETP Econ Lecture Chapter 14Document49 pagesETP Econ Lecture Chapter 14nebiyuNo ratings yet

- Parkin 13ge Econ IMDocument10 pagesParkin 13ge Econ IMDina SamirNo ratings yet

- Week 1 Ch3 Consumer BehaviorDocument31 pagesWeek 1 Ch3 Consumer BehaviorKok SiangNo ratings yet

- SlidesDocument54 pagesSlidesMohsin AliNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Lecture PresentationDocument49 pagesChapter 8 Lecture PresentationDina SamirNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics Canada in The Global Environment Canadian 9th Edition Parkin Solutions ManualDocument20 pagesMacroeconomics Canada in The Global Environment Canadian 9th Edition Parkin Solutions Manualroryhungzad6100% (35)

- Consumer Behavior: Chapter OutlineDocument34 pagesConsumer Behavior: Chapter Outlineabhinanda_22No ratings yet

- Chapter 4. Consumer ChoiceDocument59 pagesChapter 4. Consumer ChoiceTomik ZhNo ratings yet

- 04 PreferencesDocument36 pages04 PreferencesVinod KumarNo ratings yet

- Park - 7e - SM - ch09 Possibilities Preferences and ChoicesDocument20 pagesPark - 7e - SM - ch09 Possibilities Preferences and ChoicesAhmad Osama MashalyNo ratings yet

- Principles of Economics 3Document34 pagesPrinciples of Economics 3reda gadNo ratings yet

- LESSON 02 Consumer-BehDocument27 pagesLESSON 02 Consumer-BehSarthak RajNo ratings yet

- Mod. 4A Theory of Ind. BehaviorDocument25 pagesMod. 4A Theory of Ind. BehaviorPatricia AtienzaNo ratings yet

- 05 Best Choice PointDocument19 pages05 Best Choice PointVinod KumarNo ratings yet

- A152 Beeb2013 Ch3 Theory of Consumer Behavior Pindyck8eDocument36 pagesA152 Beeb2013 Ch3 Theory of Consumer Behavior Pindyck8eying huiNo ratings yet

- Intermediate MicroeconomicsDocument20 pagesIntermediate MicroeconomicsInésNo ratings yet

- Consumer Theory: Kazi Zayana Arif BSS (Economics), MSS (Economics) University of DhakaDocument26 pagesConsumer Theory: Kazi Zayana Arif BSS (Economics), MSS (Economics) University of DhakaHussein MubasshirNo ratings yet

- Demand AnalysisDocument10 pagesDemand AnalysisBarno NicholusNo ratings yet

- 9na LecturaDocument2 pages9na LecturaEdú F. Mamani PaccoNo ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviorDocument15 pagesConsumer BehaviorSamia RasheedNo ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviourDocument44 pagesConsumer BehaviourYosep Erjuandi SilabanNo ratings yet

- ch03 Pindyck 1195344570812710 2Document116 pagesch03 Pindyck 1195344570812710 2ruchit2809No ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Consumer BehaviourDocument17 pagesChapter 3 - Consumer BehaviourRitesh RajNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics and Business Strategy - Ch. 4 - The Theory of Individual BehaviorDocument26 pagesManagerial Economics and Business Strategy - Ch. 4 - The Theory of Individual BehaviorRayhanNo ratings yet

- Besanko and Braeutigam Microeconomics 4 PDFDocument33 pagesBesanko and Braeutigam Microeconomics 4 PDFSteve Schmear100% (3)

- Chap - 21 The Theory of Consumer ChoiceDocument97 pagesChap - 21 The Theory of Consumer Choiceruchit2809100% (1)

- Parkin Econ Ch09-NotesDocument8 pagesParkin Econ Ch09-Notesbarros8811No ratings yet

- 02 UtilityDocument20 pages02 UtilitypriyankaNo ratings yet

- Perilaku KonsumenDocument59 pagesPerilaku KonsumenhanxzraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Consumer BehaviorDocument8 pagesChapter 3 Consumer BehaviorIsbah Z OmerNo ratings yet

- Principles and Preferences: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument34 pagesPrinciples and Preferences: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinAnugragha SundarNo ratings yet

- Model QuestionDocument16 pagesModel Questionarpitas16No ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior Approaches Consumer EquilibriumDocument44 pagesConsumer Behavior Approaches Consumer EquilibriumNanda Kumar100% (2)

- Chapter 21Document5 pagesChapter 21Gia HânNo ratings yet

- ch03 08-31 08Document22 pagesch03 08-31 08ruchit2809No ratings yet

- Theory of Consumer ChoiceDocument9 pagesTheory of Consumer ChoiceAbhijit SarkarNo ratings yet

- Ecn 8Document36 pagesEcn 8Heidi HanaNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Indifference Curve Analysis (Part 1)Document26 pagesUnit 5 Indifference Curve Analysis (Part 1)Kashif JavedNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Lecture PresentationDocument63 pagesChapter 5 Lecture PresentationMonica ZHENGNo ratings yet

- Indifference Curve Theory Notes 2022Document16 pagesIndifference Curve Theory Notes 2022derivlimitedsvgNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior PDFDocument43 pagesConsumer Behavior PDFSanjay SethiaNo ratings yet

- Economics Lecture III: The Theory of Consumer BehaviourDocument9 pagesEconomics Lecture III: The Theory of Consumer BehaviourAditya kumar guptaNo ratings yet

- Consumer TheoryDocument21 pagesConsumer TheorynadiyaaliNo ratings yet

- A. Theory:: 1. The Budget Constraint - What The Consumer Can AffordDocument3 pagesA. Theory:: 1. The Budget Constraint - What The Consumer Can AffordHuong Mai VuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4, David Besanko Microeconomics. Assignment - KobraDocument8 pagesChapter 4, David Besanko Microeconomics. Assignment - KobrabaqirNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics Exam Study GuideDocument29 pagesMicroeconomics Exam Study GuideAndrew HoNo ratings yet

- Consumer Choice and Demand DecisionsDocument40 pagesConsumer Choice and Demand DecisionsNelly OdehNo ratings yet

- Document From Hassan RazaDocument14 pagesDocument From Hassan RazaAli RazaNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Demand and PricingDocument7 pagesModule 4 Demand and PricingWinnie ToribioNo ratings yet

- FoE Unit IIDocument43 pagesFoE Unit IIDr Gampala PrabhakarNo ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviorDocument7 pagesConsumer BehaviorWondimu Mekonnen ShibruNo ratings yet

- 7 Competitive Firms and MarketsDocument36 pages7 Competitive Firms and MarketsGretel MinayaNo ratings yet

- 4 ProductionDocument24 pages4 ProductionGretel MinayaNo ratings yet

- 2 Supply Demand and ElasticityDocument43 pages2 Supply Demand and ElasticityGretel MinayaNo ratings yet

- ZimmererDocument33 pagesZimmererGretel MinayaNo ratings yet

- Website Info Final 2Document2 pagesWebsite Info Final 2Arpit KumarNo ratings yet

- Economic Theories of The Firm - Past, Present, and Future PDFDocument16 pagesEconomic Theories of The Firm - Past, Present, and Future PDFJeremiahOmwoyoNo ratings yet

- Vimal Moulders India Pvt. Ltd. First/Last Part Approval Inspection ReportDocument1 pageVimal Moulders India Pvt. Ltd. First/Last Part Approval Inspection ReportartiNo ratings yet

- Risk Management in ConstructionDocument10 pagesRisk Management in ConstructionNiharika SharmaNo ratings yet

- TANAPatrika August 2022Document64 pagesTANAPatrika August 2022anushaNo ratings yet

- Repeat After Me 8 14 13Document15 pagesRepeat After Me 8 14 13api-221838643No ratings yet

- Management Programme: MFP-1: Equity MarketsDocument2 pagesManagement Programme: MFP-1: Equity MarketsDivey GuptaNo ratings yet

- Latest Bank State Ment...Document9 pagesLatest Bank State Ment...MUTHYALA NEERAJANo ratings yet

- Quality Checklist For Site Works: 17 Wet-Area Waterproofing TaskDocument1 pageQuality Checklist For Site Works: 17 Wet-Area Waterproofing Taskadnan-651358No ratings yet

- CHAPTER 3pdf - 211118 - 130431Document21 pagesCHAPTER 3pdf - 211118 - 130431Amalin IlyanaNo ratings yet

- Kendriya Vidyalaya Dipatoli Formative Assessment - III, (2015-16) Time-Class-V (FIVE) M.M - Grade A+ Subject - Environmental StudiesDocument5 pagesKendriya Vidyalaya Dipatoli Formative Assessment - III, (2015-16) Time-Class-V (FIVE) M.M - Grade A+ Subject - Environmental StudiesSUBHANo ratings yet

- Tender For Providing 39 Cleaner and 4 Office Boys For The Ministry of Justice & Islamic Affairs For The Period of 1 Year and 9 MonthsDocument2 pagesTender For Providing 39 Cleaner and 4 Office Boys For The Ministry of Justice & Islamic Affairs For The Period of 1 Year and 9 MonthsTina SubinNo ratings yet

- Statement1679393377960 PDFDocument5 pagesStatement1679393377960 PDFAaditya Vignyan VellalaNo ratings yet

- Gift Deed and Transfer Set Required at MumbaiDocument28 pagesGift Deed and Transfer Set Required at MumbaiSandeep DubeyNo ratings yet

- FLSmidth LUDOFLEX Rubber and Ceramic Lined Material Handling HosesBrochure ExternalDocument7 pagesFLSmidth LUDOFLEX Rubber and Ceramic Lined Material Handling HosesBrochure ExternalAbhi SinghNo ratings yet

- TA9 Unit 1: Local EnvironmentDocument7 pagesTA9 Unit 1: Local EnvironmentKhánh Nguyên TrầnNo ratings yet

- Housing Price TrackerDocument14 pagesHousing Price Trackervenu4u498No ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Microeconomics by David Besanko Ronald Braeutigam Test BankDocument26 pagesChapter 5 Microeconomics by David Besanko Ronald Braeutigam Test BankNupur KasliwalNo ratings yet

- Answer Key Quiz Chapter 12 MC All Variances PDF FreeDocument3 pagesAnswer Key Quiz Chapter 12 MC All Variances PDF FreeNikka Nicole ArupatNo ratings yet

- PNSMV025Document36 pagesPNSMV025Philippe Alexandre100% (1)

- Dividend Zakat & Tax Deduction ReportsDocument4 pagesDividend Zakat & Tax Deduction ReportsfahadullahNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips Oliver Velez Swing Core Guerrilla Options Trading Tactics (1) (001 078)Document78 pagesDokumen - Tips Oliver Velez Swing Core Guerrilla Options Trading Tactics (1) (001 078)Sergio MoralesNo ratings yet

- LK 2 - Perawatan BateraiDocument10 pagesLK 2 - Perawatan BateraiERWAN ABADI IBRAHIMNo ratings yet

- Critical SolvingDocument76 pagesCritical SolvingAdner CabaloNo ratings yet

- Deliveroo Order Receipt 10285722234Document2 pagesDeliveroo Order Receipt 10285722234Richie NubiNo ratings yet

- DuPont Kevlar Vehicle Armor BrochureDocument4 pagesDuPont Kevlar Vehicle Armor Brochure김영우No ratings yet

- Freefincal Stock Analyzer May 2017 SCR Edition Earnings Power Box 1Document1,257 pagesFreefincal Stock Analyzer May 2017 SCR Edition Earnings Power Box 1Positive ThinkerNo ratings yet

- Barrage BOQDocument19 pagesBarrage BOQPowerhouse ShaftNo ratings yet