Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Specialist and Transitional Care Provision For Amelogenesis Imperfecta - A UK-wide Survey

Specialist and Transitional Care Provision For Amelogenesis Imperfecta - A UK-wide Survey

Uploaded by

Mohammad Abdulmon’emCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Management of Patients On Systemic Steroids - An Oral Surgery PerspectiveDocument7 pagesManagement of Patients On Systemic Steroids - An Oral Surgery PerspectiveMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Abas Mohamed SidowDocument3 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Abas Mohamed SidowAbas Mohamed Sidow50% (2)

- NSTP CertDocument4 pagesNSTP CertPoy Mariano AdesNo ratings yet

- Teaching Children With Disabilities - Emily GreenhalghDocument7 pagesTeaching Children With Disabilities - Emily Greenhalghapi-427319867No ratings yet

- The Role of Dental Hygienists and Therapists in Paediatric Oral Healthcare in ScotlandDocument6 pagesThe Role of Dental Hygienists and Therapists in Paediatric Oral Healthcare in ScotlandHarris SaeedNo ratings yet

- Attitudes To and Knowledge About Oral Health Care Among Nursing Home Personnel - An Area in Need of ImprovementDocument6 pagesAttitudes To and Knowledge About Oral Health Care Among Nursing Home Personnel - An Area in Need of ImprovementSaravanan ThangarajanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document7 pagesJurnal 1Liza MaisyuraNo ratings yet

- Acmph 1 101Document5 pagesAcmph 1 101Adnan SaffiNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge Attitude and Perception of Dental Students Towards Obesity in Kanpur CityDocument6 pagesAssessment of Knowledge Attitude and Perception of Dental Students Towards Obesity in Kanpur CityAdvanced Research PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics & TherapeuticsDocument7 pagesPediatrics & TherapeuticsAmit PasiNo ratings yet

- Factors in Uencing Satisfaction With The Process of Orthodontic Treatment in Adult PatientsDocument9 pagesFactors in Uencing Satisfaction With The Process of Orthodontic Treatment in Adult PatientsLikhitaNo ratings yet

- Attitude ArticleDocument9 pagesAttitude Articlemeena syedNo ratings yet

- Amhsr 2 14Document5 pagesAmhsr 2 14Archana KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Interceptive Orthodontic Treatment in Reducing MalocclusionsDocument8 pagesEffectiveness of Interceptive Orthodontic Treatment in Reducing MalocclusionsAriana de LeonNo ratings yet

- Alighieri 2020Document10 pagesAlighieri 2020Natalia AlberoNo ratings yet

- Use of EConsult To Enhance Genetics Service Delivery in PR 2022 Genetics inDocument8 pagesUse of EConsult To Enhance Genetics Service Delivery in PR 2022 Genetics inronaldquezada038No ratings yet

- Oralcareforin PatientsDocument7 pagesOralcareforin PatientsCristina MihaiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0882596322001294 IngDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0882596322001294 IngFlavio Augusto SerraNo ratings yet

- Junal Pico 1 KariesDocument9 pagesJunal Pico 1 KariesAnonymous 5qI7toeVzNo ratings yet

- Prevalencia y Distribución de HMI en CaracasDocument9 pagesPrevalencia y Distribución de HMI en CaracasDanitza GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- 10 1002@jdd 12254Document7 pages10 1002@jdd 12254Bernard HerreraNo ratings yet

- Ajnr 130Document16 pagesAjnr 130GRF PUBLISHERSNo ratings yet

- Ref 7Document19 pagesRef 7indah anggarainiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0882596321003262 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0882596321003262 Maingczywtxd4pNo ratings yet

- Dental Status of Children Receiving School Oral Health Services in TshwaneDocument7 pagesDental Status of Children Receiving School Oral Health Services in TshwaneTy WrNo ratings yet

- Factoring Patient Compliance PDFDocument11 pagesFactoring Patient Compliance PDFneetika guptaNo ratings yet

- Ipd 12715Document10 pagesIpd 12715Ayu DamayNo ratings yet

- Chen 2019Document9 pagesChen 2019Tiara HapkaNo ratings yet

- The Use of General Anesthesia For Pediatric Dentistry in Saskatchewan: A Retrospective StudyDocument9 pagesThe Use of General Anesthesia For Pediatric Dentistry in Saskatchewan: A Retrospective StudyAbi de la PeñaNo ratings yet

- Archive of SIDDocument6 pagesArchive of SIDBeuty SavitriNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Referral Patterns of General Dentists: Lessons For Dental EducationDocument12 pagesPeriodontal Referral Patterns of General Dentists: Lessons For Dental EducationVio VisanNo ratings yet

- Safeguarding Children in Dentistry: 2. Do Paediatric Dentists Neglect Child Dental Neglect?Document6 pagesSafeguarding Children in Dentistry: 2. Do Paediatric Dentists Neglect Child Dental Neglect?bkprosthoNo ratings yet

- BrazilDocument7 pagesBrazilkarinagitakNo ratings yet

- Previous Radiographic Experience of Children Referred For Dental Extractions Under General Anaesthesia in The UKDocument3 pagesPrevious Radiographic Experience of Children Referred For Dental Extractions Under General Anaesthesia in The UKLily BrostNo ratings yet

- Patient's Expectation of Orthodontic Treatment at A Tertiary Health Facility in Lagos, NigeriaDocument6 pagesPatient's Expectation of Orthodontic Treatment at A Tertiary Health Facility in Lagos, NigeriadochetNo ratings yet

- Adj 12749Document10 pagesAdj 12749Irfan HussainNo ratings yet

- HSDC QuintesenceDocument6 pagesHSDC QuintesenceDavid CasaverdeNo ratings yet

- Froh 02 656530Document11 pagesFroh 02 656530Alexandru Codrin-IonutNo ratings yet

- Parent Escalation of Care For The Deteriorating Child in Hospital: A Health Care Improvement StudyDocument11 pagesParent Escalation of Care For The Deteriorating Child in Hospital: A Health Care Improvement Studybhazferrer2100% (1)

- 7 - Quantitative Assessment of The EffectivenessDocument8 pages7 - Quantitative Assessment of The Effectivenessanhca4519No ratings yet

- P WorkforceissuesDocument5 pagesP WorkforceissuesfaizahNo ratings yet

- Swoope1977 PDFDocument8 pagesSwoope1977 PDFKrupali JainNo ratings yet

- India Evaluation of Public Awareness, Knowledge andDocument8 pagesIndia Evaluation of Public Awareness, Knowledge andMax FaxNo ratings yet

- Working Practices and Job Satisfaction of Victorian Dental HygienistsDocument6 pagesWorking Practices and Job Satisfaction of Victorian Dental Hygieniststea metaNo ratings yet

- Childhood Caries Management in The European UnionDocument10 pagesChildhood Caries Management in The European Unionrossanamns622No ratings yet

- 3 - Reco Anglaise Lyell EnfantsDocument34 pages3 - Reco Anglaise Lyell Enfantsedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Article 12Document6 pagesArticle 12ROSANo ratings yet

- Other Journals in Brief: Research InsightsDocument1 pageOther Journals in Brief: Research InsightsyoiNo ratings yet

- Longetivity of DentureDocument9 pagesLongetivity of DentureShyam DangarNo ratings yet

- JPM 11 00452Document12 pagesJPM 11 00452Putu Gyzca PradyptaNo ratings yet

- 2022 Article 721Document8 pages2022 Article 721cosadedubsNo ratings yet

- NHS England Paediatric DentistryDocument15 pagesNHS England Paediatric DentistryDina ElkharadlyNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Level of Medical-Emergency-RelatedDocument10 pagesMeasuring The Level of Medical-Emergency-RelatedVidyandika PermanasariNo ratings yet

- 03 Knowledge Attitudes and Behavior Towards Oral Health Among A Group of Staff Caring For Elderly People in Long Term Care Facilities in Bangkok ThailandDocument16 pages03 Knowledge Attitudes and Behavior Towards Oral Health Among A Group of Staff Caring For Elderly People in Long Term Care Facilities in Bangkok ThailandFadli AlwiNo ratings yet

- F1000research 9 55792Document22 pagesF1000research 9 55792Tsaniya KamilahNo ratings yet

- archivev3i3MDIwMTMxMDIy PDFDocument9 pagesarchivev3i3MDIwMTMxMDIy PDFLatasha WilderNo ratings yet

- Implementation of A Was Not Brought' Pathway in Paediatric DentistryDocument5 pagesImplementation of A Was Not Brought' Pathway in Paediatric DentistryYaman HassanNo ratings yet

- AAPD Teledentistry 2021Document2 pagesAAPD Teledentistry 2021Francisca Abarca CifuentesNo ratings yet

- Atraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART) in Pediatric Dentistry Residency Programs: A Survey of Program DirectorsDocument7 pagesAtraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART) in Pediatric Dentistry Residency Programs: A Survey of Program DirectorsrizkiNo ratings yet

- Reforming Dental Health Professions EducationDocument25 pagesReforming Dental Health Professions EducationSanaFatimaNo ratings yet

- Non-pharmacological behaviour management - 副本Document37 pagesNon-pharmacological behaviour management - 副本刘雨樵No ratings yet

- Children - Free Full-Text - Importance of Desensitization For Autistic Children in Dental PracticeDocument2 pagesChildren - Free Full-Text - Importance of Desensitization For Autistic Children in Dental Practicestivensumual0701136055No ratings yet

- Phadraig Et Al 2019 - Systematic DesensitizationDocument16 pagesPhadraig Et Al 2019 - Systematic DesensitizationCarlindo e CarlindoNo ratings yet

- Treatment Planning in Restorative Dentistry and Implant ProsthodonticsFrom EverandTreatment Planning in Restorative Dentistry and Implant ProsthodonticsNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Impact of COVID-19 On Dental Antibiotic Prescribing Across England - 'It Was A Minefield'Document6 pagesUnderstanding The Impact of COVID-19 On Dental Antibiotic Prescribing Across England - 'It Was A Minefield'Mohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- The Versatility of Flowable Composites. Part 2 - Clinical UsesDocument4 pagesThe Versatility of Flowable Composites. Part 2 - Clinical UsesMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- The Dental Effects of Head and Neck Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment - A Case SeriesDocument6 pagesThe Dental Effects of Head and Neck Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment - A Case SeriesMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation Challenge in Patient With High Smile Line: Case Report and Review of Surgical ProtocolsDocument8 pagesRehabilitation Challenge in Patient With High Smile Line: Case Report and Review of Surgical ProtocolsMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue Calcification Seen On Dental RadiographsDocument4 pagesSoft Tissue Calcification Seen On Dental RadiographsMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Pub BassamHassan YMPR2177Document12 pagesPub BassamHassan YMPR2177Mohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Is There Clinical Evidence To Support Alveolar Ridge Preservation Over Extraction Alone? A Review of Recent Literature and Case Reports of Late Graft FailureDocument6 pagesIs There Clinical Evidence To Support Alveolar Ridge Preservation Over Extraction Alone? A Review of Recent Literature and Case Reports of Late Graft FailureMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Recognition and Management of Drug-Associated Oral Ulceration - A ReviewDocument5 pagesRecognition and Management of Drug-Associated Oral Ulceration - A ReviewMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Intentional Replantation - An Underused Modality?Document7 pagesIntentional Replantation - An Underused Modality?Mohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Disease - The Profession's ChoicesDocument2 pagesDiabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Disease - The Profession's ChoicesMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- A 5-Year Observation of The Dahl Principle To Manage Localized Anterior Tooth WearDocument5 pagesA 5-Year Observation of The Dahl Principle To Manage Localized Anterior Tooth WearMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- An Update On Record KeepingDocument4 pagesAn Update On Record KeepingMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Flangeless Horseshoe Maxillary Complete Denture - A Prosthodontic Solution To Maxillary ToriDocument3 pagesFlangeless Horseshoe Maxillary Complete Denture - A Prosthodontic Solution To Maxillary ToriMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Broken Needle - A Rare Complication of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block - A Report of Two CasesDocument4 pagesBroken Needle - A Rare Complication of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block - A Report of Two CasesMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Improving A Classroom-Based Assessment TestDocument27 pagesImproving A Classroom-Based Assessment TestRodel Yap100% (1)

- Kampamba Kasamba Possition PaperDocument5 pagesKampamba Kasamba Possition PaperCLANSIE BUXTON CHIKUMBENo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment E-Marketing July 2020Document2 pagesIndividual Assignment E-Marketing July 2020Hafsah Ahmad najibNo ratings yet

- Mã đề 103Document5 pagesMã đề 103yangyang2k4No ratings yet

- At The End of The Lesson, The Learners Should Be Able ToDocument4 pagesAt The End of The Lesson, The Learners Should Be Able ToHarold Nalla HusayanNo ratings yet

- How Social Workers WomanDocument22 pagesHow Social Workers WomanSheroze DogerNo ratings yet

- Tugasan KK TSLB3163 2020Document4 pagesTugasan KK TSLB3163 2020Sri Darsshane Raj Sivasubramaniam100% (1)

- Expectation and Motivation of Maritime Students in Pursuing Maritime EducationDocument51 pagesExpectation and Motivation of Maritime Students in Pursuing Maritime EducationJullie Carmelle ChattoNo ratings yet

- Job Vacancies at African Rural UniversityDocument4 pagesJob Vacancies at African Rural UniversityThe Campus TimesNo ratings yet

- Placemats: "They Are Not Just For Dining"Document7 pagesPlacemats: "They Are Not Just For Dining"Nor HazimahNo ratings yet

- Assignment Project Spring 2010 11Document3 pagesAssignment Project Spring 2010 11Andreas PittasNo ratings yet

- Department Of: ButationDocument140 pagesDepartment Of: ButationGLORIA VALERANo ratings yet

- For Social Innovation: Author Kyriaki PapageorgiouDocument72 pagesFor Social Innovation: Author Kyriaki PapageorgiouMonica Grau SarabiaNo ratings yet

- Eng PostgradDocument102 pagesEng PostgradKM_147No ratings yet

- 21 - PHAN Le Hai Ngan - CHALLENGES - CONSTRAINTS PDFDocument11 pages21 - PHAN Le Hai Ngan - CHALLENGES - CONSTRAINTS PDFWoo TungNo ratings yet

- Module 7.implementationDocument18 pagesModule 7.implementationBuried_Child100% (2)

- Application ProcessDocument2 pagesApplication ProcessMaheeshNo ratings yet

- Teaching Mathematics Using Blended Learning Model: A Case Study in Uitm Sarawak CampusDocument6 pagesTeaching Mathematics Using Blended Learning Model: A Case Study in Uitm Sarawak CampusfairusNo ratings yet

- Prepared By: Cabasag, Rubie C., MM, LPTDocument9 pagesPrepared By: Cabasag, Rubie C., MM, LPTGlaiza Kaye SalazarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Nigerian CultureDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Nigerian Culturevehysad1s1w3100% (1)

- Scholastic Aptitude Tests (Sats) & English Proficiency Tests (Toefl, Ielts)Document5 pagesScholastic Aptitude Tests (Sats) & English Proficiency Tests (Toefl, Ielts)Gayathri GayuNo ratings yet

- CV of M RajuDocument3 pagesCV of M RajuMd Zahidul AhsanNo ratings yet

- Talahanayan NG Ispesipikasyon: NilalamanDocument2 pagesTalahanayan NG Ispesipikasyon: NilalamanErna Mae AlajasNo ratings yet

- Principal'S Monthly Report On Enrolment and Other School Data (Enhanced Form 3)Document12 pagesPrincipal'S Monthly Report On Enrolment and Other School Data (Enhanced Form 3)Zion HillNo ratings yet

- Application No. 2024016946: Application Form For B.Tech. Admissions - 2024Document2 pagesApplication No. 2024016946: Application Form For B.Tech. Admissions - 2024sankarshanNo ratings yet

- GueorguievDocument8 pagesGueorguievAdel ToumiNo ratings yet

- FDP-2024 ScheduleDocument1 pageFDP-2024 Schedulelakshmi cnNo ratings yet

Specialist and Transitional Care Provision For Amelogenesis Imperfecta - A UK-wide Survey

Specialist and Transitional Care Provision For Amelogenesis Imperfecta - A UK-wide Survey

Uploaded by

Mohammad Abdulmon’emOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Specialist and Transitional Care Provision For Amelogenesis Imperfecta - A UK-wide Survey

Specialist and Transitional Care Provision For Amelogenesis Imperfecta - A UK-wide Survey

Uploaded by

Mohammad Abdulmon’emCopyright:

Available Formats

RESEARCH

Specialist and transitional care provision for

amelogenesis imperfecta: a UK-wide survey

Fiona Lafferty,*1 Sondos Albadri,2 Susan Parekh3 and Francesca Soldani4

Key points

Access to specialist paediatric dental care and There is a need to establish and improve care There is enthusiasm in the UK paediatric dentistry

transition to adult services is not readily available pathways for paediatric AI patients throughout the workforce for improvement to AI care pathways

nationally for amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) UK. to be made. Education, addressing workforce

paediatric patients. shortages and refining pathways are areas that

require further development.

Abstract

Background Amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) can be challenging to manage due to the complexity and variation of

presentation. Clear care pathways between general practice, specialist paediatric dentistry and adult services are

required.

Aim To assess the provision of specialist care and transitional care arrangements for paediatric patients with AI in the UK.

Method An online survey was disseminated to members of the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry in January 2020.

Descriptive analysis was used to interpret the quantitative and qualitative results.

Results In total, 115 clinicians across all four nations participated. Most respondents (54%; n = 66), were based in the

hospital dental service. Overall, 29% (n = 33) were consultants and 24% (n = 28) were specialists in paediatric dentistry.

The most common patient age group seen was 6–12 years old. No clear AI referral pathway into specialist care was

reported by 49% (n = 47). A clear transitional care pathway was deemed not to exist by 77% (n = 72), with 85.9%

(n = 73) indicating a need. Qualitative analysis themes included ‘unclear care pathways’ and ‘specialist care access

problems’.

Conclusion Access to specialist paediatric dental care and transition to adult services is not readily available throughout

the UK for AI patients. There is a clear need to establish and improve existing pathways.

Introduction AI is a rare, genetic condition affecting should also be dynamic and allow variations,

dental enamel, with a prevalence of 1 in 700 such as patients transitioning from primary

Paediatric patients with amelogenesis to 1 in 14,000, depending on the population care to adult specialist centres, whether or not

imperfecta (AI) often require a combination studied.1 The impact of AI is significant and paediatric dentistry had been involved.

of specialist dental input and care provision in includes functional, aesthetic and psychosocial Access to specialist paediatric dental care in

general dental practice. The role of the general problems, in addition to difficulties providing the UK is varied. There are workforce shortages

dental practitioner (GDP) is to provide routine effective treatment.1,2,3 There has recently and geographical challenges, with some areas

care and identify those patients who require been documented a high burden of care lacking access to specialist paediatric dental

further assessment by a specialist team. This for paediatric patients with AI in the UK teams.7,8,9 This results in some areas of the

amalgamation of care should be available NHS, with improvement in care for this UK where primary care clinicians may have

locally to families and include a smooth patient cohort essential. 4 In addition, a difficulty in obtaining local specialist care

transition to adult services. newly developed Patient-Reported Outcome access for patients. The challenges in providing

Measure for this condition demonstrates, treatment for these patients does not cease on

from the patient’s perspective, the range of reaching adulthood. There is a need for the

1

Glasgow Dental Hospital and School, Glasgow, Scotland,

problems, concerns and impact AI has on a paediatric team to have clear pathways for

UK; 2University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK; 3University

College London, London, UK; 4Community Dental Service, child.5 Opportunity to access early specialist transition of these patients to adult services.

Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust, Bradford, UK. assessments will improve management and aid Patients who are discharged from paediatric

*Correspondence to: Fiona Lafferty

Email address: fiona.lafferty2@nhs.scot transition of these patients to adulthood with services into primary care alone may face

Refereed Paper.

comfortable, functional dentitions.6 Robust challenges in referral acceptance back into

Submitted 16 February 2022 relationships and clear pathways between specialist care as an adult. There may then be a

Revised 31 May 2022 specialist centres and primary care can ensure financial burden put on these patients seeking

Accepted 9 June 2022 children and young people (CYP) receive care in the primary care setting and the GDP

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-5077-x

comprehensive, timely care. The pathway left unsupported in managing these patients,

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL | ONLINE PUBLICATION | SEPTEMBER 28 2022 1

RESEARCH

resulting in an overall increased burden of This method has been similarly used in other demonstrates the differences in responses

care. Inequalities and barriers to transitioning cross-sectional studies in the literature seeking to the number of AI patients under care.

paediatric patients to specialist adult dental views of the dental workforce.11 Treatment appointments for AI were not

services are required to be defined and reported as frequent, with 84.7% (n = 83/98) of

explored before improvements can be made. Results respondents reporting less than five treatment

The aim of this study was therefore to assess appointments for AI patients per month.

the provision of specialist care and transitional Respondents Another 12.2% (n = 12/98) reported they

care arrangements for paediatric patients with The survey was sent to 670 BSPD members, carry out between five and ten appointments

AI in the UK. with a response rate of 17.2% (n = 115). per month, with only 3.1% (n = 3/98) carrying

Respondents were from a mixture of all four out more than ten treatment appointments.

Materials and methods UK home nations and were mainly based The patient age group most commonly

in the hospital and community services, as seen was 6–12 years old (69.9%; n = 65/93).

An online survey was disseminated by email demonstrated in Figure 1. Most clinicians were The types of AI seen by respondents was

to members of the British Society of Paediatric based in England (72.6%; 82/113), followed by varied, with responses spread across all given

Dentistry (BSPD) in January 2020. A two- Scotland 13.3% (15/113), Wales 8.9% (10/113) definitions of: hypomature, hypoplastic,

month period was allowed for completion. and 5% (6/113) in Northern Ireland. The hypocalcified, hypoplasia/hypomaturation/

Further reminder emails were sent to both respondents were a mixture of consultants taurodontism and mixed appearance.

the consultants in paediatric dentistry and (28.7%; n = 33), specialists (24.4%; n = 28)

trainee groups. and other dentists with an interest in paediatric

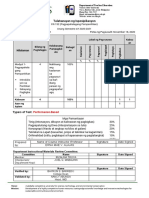

The survey was designed by members of dentistry through their BSPD membership Fig. 1 Survey respondents’ primary work

role

the AI Clinical Excellence Network (CEN). (47%; n = 54). All 115 respondents answered

This included three consultants in paediatric the primary work role question and where 2.6% 1.7%

dentistry from different units in the UK and the majority of their work was based. For 4.4%

1.7%

with backgrounds from both the hospital the remaining questions, there was a varied

and community service. The AI CEN was response rate as indicated in the text, with most

established in 2019 with an aim to promote questions answered by 93–99 clinicians.

clinical excellence for CYP with this condition.

As part of this remit, this survey was devised AI patients

to identify current care practices and aid The average number of new AI diagnoses

with future project design and work-streams seen per month was reported to be low. One

for the group. The questionnaire did not ask to two patients diagnosed per month was

any controversial questions (for example, the most common (48.5%; n = 48/99) but

challenging or difficult topics) and was directed many respondents would not see any new AI 53.9%

35.6%

to those clinicians who expressed willingness diagnoses (27.3%; n = 27/99), with only one

to engage in the CEN and was completely respondent reporting they would see more

anonymous at all stages. than ten each month.

Hospital service Community dental service

Ethical approval was not required for Current AI patients under care was also

NHS practice Private practice

this study as it was deemed to be a service reported as low, with the majority of clinicians Mixed practice Other

evaluation. The invitations to participate were (81.8%; n = 81/99) having between one

sent through the BSPD membership with and ten patients under their care. Figure 2

the authors of this paper having no access

to participant contact information or any Fig. 2 Bar chart demonstrating how many AI patients are currently under care

identifying information; consent to participate

was implied by proceeding with the survey. More than 20 patients

The survey consisted of 18 mixed format

questions, including free-text options, single Between 11 and 20 patients

answers and ranked options. These included

demographics of the respondents’ paediatric Between 6 and 10 patients

dentistry background, AI patients seen in their

service, and pathways including referral into Between 3 and 5 patients

specialist care and provisions for transitional

1–2 patients

care. Descriptive analysis was used to interpret

the results and analysis was completed of the

None

free-text data by a single-handed reviewer. The

analysis was based on a recognised six-stage 0 5 10 15 20 25 30

format, including familiarisation with the data,

No. of respondents

coding, identifying and reviewing of themes.10

2 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL | ONLINE PUBLICATION | SEPTEMBER 28 2022

RESEARCH

Pathways respondents, with only 22.6% (n = 21/93) of Specialist adult restorative services was the

No clear AI referral pathway into specialist respondents indicating there was. In terms most popular transition pathway, followed

care was reported by 49.5% (n = 47/95) of of obstacles to providing a transition service, by returning patients to primary care once

respondents, with another 19% (n = 18/95) there were only 15 responses to this question. treatment completed. Some respondents

unsure if there was a pathway. Of these 15 responses, 53.3% (n = 8/15) did (n = 11) indicated their patients would simply

The majority of patients were referred not think they were any obstacles. be discharged after a set period of care in

into specialist care by their GDP (93.6%; Dedicated AI clinics for adult patients were their service. Interestingly, the yellow bar in

n = 88/94), with small numbers referred by not known to exist in most cases (56.8%; Figure 4 demonstrates there were a number of

their general medical practitioner (1.1%; n = 54/95), with another 35.8% (n = 34/95) respondents who were unsure if some of the

n = 1/94), via self-referral (1.1%; n = 1/94) of respondents unsure if these were available. transition pathways were available to them. In

or through other means (4.3%; n = 4/94). A Respondents were asked whether their terms of justification for transition pathways,

dedicated AI or anomaly clinic for paediatric patients transitioned to a number of different this was asked in a subsequent question, with

patients was not common, with 72.6% settings and selected all that applied. There 85.9% (n = 73/85) of respondents thinking

(n = 69/95) of responses indicating there was a combination of multi-disciplinary, there is a need for a transition pathway for

were no dedicated clinics, as can be seen in general dental service and adult restorative AI patients.

Figure 3. transitions pathways utilised as indicated

A clear transitional care pathway was by 22 respondents (Fig. 4). This was from Free-text analysis

deemed not to exist by 77.4% (n = 72/93) of a smaller number of respondents (19%). The final four questions of the survey

provided a free-text option to answer the

Fig. 3 Bar chart indicating whether there were dedicated AI or anomaly clinics questions concerning transitional services,

obstacles in providing these and any further

comments around AI care. The data were

analysed by the lead for the project. Five

Unsure

core themes were identified, as shown in

No

Table 1, with examples of quotes related to

the themes given.

Yes The four questions included:

• Please expand on the above (for example,

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 what transition pathway is most common

No. of respondents in your service? (18 responses)

• Are you facing any obstacles providing

such a transition service? Please specify

(15 responses)

Fig. 4 Bar chart indicating where the patients transition to following paediatric care • Do you feel there is a need for a transition

pathway? (85 responses)

• Are there any other comments you wish to

Unsure feed back around AI care? (37 responses).

Discussion

Refer to a multi-disciplinary

team with paediatric and

restorative dentistry This survey provides evidence towards

the improvements required in paediatric

pathways and transitional care arrangements

Refer to specialist adult for AI patients in the UK. For many

restorative services

clinicians the number of AI patients seen

regularly is small. This, therefore, suggests

Continue providing care in the optimum management pathways and

your service for a specific care decisions required are unfamiliar and

time and discharge

infrequently practised. In general, it was

found that no clear pathway into specialist

Return to general dental

care or a protocol for transitioning to adult

service once course of

treatment completed services exists. Clinicians in primary care

who encounter this rare condition are at

0 5 10 15 20 25 risk of inadequate specialist support. There

No. of respondents are several reasons for this identified, such

Don’t Know No Yes

as further education and awareness of AI

throughout the dental workforce is required.

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL | ONLINE PUBLICATION | SEPTEMBER 28 2022 3

RESEARCH

The respondents strongly felt there is a need

Table 1 Free-text analysis themes

for a transition pathway, with access to the

appropriate specialist workforce highlighted Theme Quotation examples

as an area requiring improvement. The AI

‘More GDPs should be aware of AI and its management and know to refer before problems’

phenotype and patient wishes were deemed to

AI education

be important considerations in the transition ‘Many GDPs do not recognise AI for what it is unless there is a family history’

required

to adult care. A flexible and locally adaptable ‘Should there be routine genetic testing for AI patients?’

pathway was highlighted as essential. ‘…needs to be a very flexible pathway as there are so many factors within the

The literature supports the uncertainty decision-making’

in providing the correct care for AI patients ‘…for all paediatric dental patients there is a need for a clear transition pathway’

Unclear care

and the need for lifelong care. 2,12 Early pathways

‘Restorative department have made referral criteria stricter’

diagnosis is important, with appropriate

and timely multi-disciplinary care key.13 The ‘Often patients reach 16 and it’s difficult to know where they should continue their care’

correct knowledge and skills in providing

‘…there is nowhere for them to go locally except GDS; no specialists or dental hospital’

good-quality care needs to be available to

Specialist care

all, with access to specialists when needed. ‘Our nearest paediatric consultant is 2–4 hours away and I work in a hot-spot for AI’

access problems

Anomalies associated with AI, such as open ‘Yes, shortage of paediatricians and restorative consultants’

bites, periodontal conditions, pulp stones

AI phenotype ‘Depends on severity and diagnosis’

and taurodontism, all complicate care. 14

affects

For provision of restorative care, indirect ‘It depends upon severity. The more severe the case, the more likely we are to arrange

transitional care

care with restorative dentistry’

restorations have been shown to be superior

to direct restorations for AI patients and Patient priorities ‘Depends on the individual patient treatment needs’

part of transition

should be provided as early as possible. 15 ‘Transition decisions are made on a case by case basis… and reported concerns during

pathway

the teenage years…’

Long-term follow-up has shown that ceramic

as a material choice can work well in young

adults. 16 Careful treatment planning in accessing care and unclear pathways, with other areas of paediatric dental care pathways

the growing patient is required to execute useful information gathered in this context. that require improvement and mirrors many

indirect restorative work well. Combined There is a low response rate to this survey; of the issues found in this study.11 Further

with the challenges in providing the correct however, it was sent to a large number of explorations into local challenges faced by

clinical care for AI patients, there is also clinicians associated with the speciality of services would be beneficial. This should be

known reservations surrounding newer paediatric dentistry. With the majority of alongside development of national protocols

aspects, such as genetic testing for AI, with respondents being either consultants or and guidelines to form a basis for service

further exploration and education required.17 specialists in paediatric dentistry, the results leads to refer to and mandate for certain

The complexities of managing a CYP with are still important to consider, with these types of care to be provided. Further research

AI can be well supported and addressed by clinicians being responsible for their transfer involving adult specialist service teams would

access to the correct local specialist services. from paediatric to adult services. also be beneficial, with consensus reached

Approximately half of the respondents Other limitations include that not all on national referral criteria and acceptance

were either specialists or consultants questions were completed in full by every for specialist care. In addition, discussion

in paediatric dentistry (53%), with the respondent, but all available data were with clinicians in primary care, along with

remaining having an interest in paediatric reported; excluding questionnaires with the patients and families themselves, will

dentistry. This allowed a well-rounded incomplete answers would have reduced be crucial in developing robust transition

perspective from both specialists and non- the volume of data available for analysis. pathways. Understanding the needs for

specialist care providers and how they work Reasons why some of the data were missing/ children with AI is complicated, with groups

together to provide care. The responses were questions not answered by all clinicians may such as the CEN for AI patients, formed

from clinicians based throughout the UK, have been that some respondents were not in 2019, being a method for strategic and

which allowed a diverse range of opinions to aware of the transition services available in multi-centred agendas to be discussed and

be gathered, with respondents able to express their department/locality or were unsure of researched. The overall aim of promoting

their views clearly through the 18 questions some of the answers. Furthermore, the small clinical excellence for young patients with

and further elaborate through the free-text quantity of qualitative data were analysed this condition ensures the importance of

comments in the final questions. using thematic analysis by a single-handed good AI care is recognised, with this group’s

Limitations of this survey include that, reviewer; the authors felt this process was aim being to drive forward the required

given it was voluntary, the respondents will adequate given the free-text sections were improvements nationally. The group are also

naturally have been those with a special limited. liaising with the UK Restorative Consultants

interest and investment in AI care for CYP. It is clear there are regional and local Group to identify colleagues who would like

This self-selected group could therefore be a variations in care and not one pathway or to lead in this area. Work towards arranging

biased representation. The results, however, care model will be appropriate for every a joint study day to discuss management and

do raise valid points about difficulties service. In the literature, there is evidence of transition issues is also ongoing.

4 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL | ONLINE PUBLICATION | SEPTEMBER 28 2022

RESEARCH

Conclusion invitations to participate were sent through the BSPD 8. Scottish Dental. Oral Health and Dental Services for

Children Needs Assessment Report. 2017. Available

membership with the authors of this paper having at https://www.scottishdental.org/library/oral-

Access to specialist paediatric care and the no access to participant contact information or any health-and-dental-services-for-children-needs-

assessment-report/ (accessed March 2020).

transition to adult services is not readily identifying information; consent to participate was

9. Mills R W. Workforce planning: The specialist map. Br

available throughout the UK for AI patients. implied by proceeding with the survey. Dent J 2016; 220: 221.

10. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in

Access to specialist care and appropriate

psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2008; 3: 77–101.

transition options for the individual patient is References 11. Morgan E, Fox K, Jarad F et al. An investigation

essential. There is a clear need to establish and 1. Crawford P J M, Aldred M, Bloch-Zupan A. Amelogenesis of transitional care pathways for young people

imperfecta. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007; 2: 17. following traumatic dental injuries. Br Dent J 2021;

improve existing care pathways and this should DOI: 10.1038/s41415-021-3471-4.

2. Dashash M, Yeung C A, Jamous I, Blinkhorn A.

be approached nationally and adapted locally. Interventions for the restorative care of amelogenesis 12. Patel M, McDonnell S T, Iram S, Chan M F W-Y.

imperfecta in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Amelogenesis imperfecta – lifelong management.

Syst Rev 2013; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007157.pub2. Restorative management of the adult patient. Br Dent

Author contributions 3. Parekh S, Almehateb M, Cunningham S J. How do J 2013; 215: 449–457.

children with amelogenesis imperfecta feel about their 13. Ortiz L, Pereira A M, Jahangiri L, Choi M.

Sondros Albadri, Susan Parekh and Francesca Management of Amelogenesis Imperfecta in

teeth? Int J Paediatr Dent 2014; 24: 326–335.

Soldani approved the survey questions and reviewed 4. Lafferty F, Al Siyabi H, Sinadinos A et al. The burden Adolescent Patients: Clinical Report. J Prosthodont

of dental care in Amelogenesis Imperfecta paediatric 2019; 28: 607–612.

the results and manuscript. Fiona Lafferty led the 14. Poulsen S, Gjørup H, Haubek D et al. Amelogenesis

patients in the UK NHS: a retrospective, multi-centred

survey roll out, analysis and manuscript writing. analysis. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2021; 22: 929–936. imperfecta – a systematic literature review of

5. Lyne A, Parekh S, Patel N et al. Patient-reported associated dental and oro-facial abnormalities and

outcome measure for children and young people with their impact on patients. Acta Odontol Scand 2008;

Acknowledgements amelogenesis imperfecta. Br Dent J 2021; DOI: 10.1038/ 66: 193–199.

s41415-021-3329-9. 15. Strauch S, Hahnel S. Restorative Treatment in

Many thanks to the members of the British Society of Patients with Amelogenesis Imperfecta: A Review.

6. Ayers K M S, Drummond B K, Harding W J, Salis S G,

Paediatric Dentistry who participated in this survey. Liston P N. Amelogenesis imperfecta – multidisciplinary J Prosthodont 2018; 27: 618–623.

management from eruption to adulthood. Review and 16. Lundgren G P, Vestlund G-I M, Dahllöf G. Crown

case report. N Z Dent J 2004; 100: 101–104. therapy in young individuals with amelogenesis

Ethics declaration 7. UK Parliament. Written evidence submitted by the imperfecta: Long term follow-up of a randomized

controlled trial. J Dent 2018; 76: 102–108.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (COH0014).

2015. Available at http://data.parliament. 17. McDowall F, Kenny K, Mighell A J, Balmer R C.

Ethical approval was not required for this study Genetic testing for amelogenesis imperfecta:

uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/

as it was deemed to be a service evaluation. The evidencedocument/health-committee/childrens-oral- knowledge and attitudes of paediatric dentists. Br

health/written/18127.html (accessed March 2020). Dent J 2018; 225: 335–339.

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL | ONLINE PUBLICATION | SEPTEMBER 28 2022 5

You might also like

- Management of Patients On Systemic Steroids - An Oral Surgery PerspectiveDocument7 pagesManagement of Patients On Systemic Steroids - An Oral Surgery PerspectiveMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Abas Mohamed SidowDocument3 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Abas Mohamed SidowAbas Mohamed Sidow50% (2)

- NSTP CertDocument4 pagesNSTP CertPoy Mariano AdesNo ratings yet

- Teaching Children With Disabilities - Emily GreenhalghDocument7 pagesTeaching Children With Disabilities - Emily Greenhalghapi-427319867No ratings yet

- The Role of Dental Hygienists and Therapists in Paediatric Oral Healthcare in ScotlandDocument6 pagesThe Role of Dental Hygienists and Therapists in Paediatric Oral Healthcare in ScotlandHarris SaeedNo ratings yet

- Attitudes To and Knowledge About Oral Health Care Among Nursing Home Personnel - An Area in Need of ImprovementDocument6 pagesAttitudes To and Knowledge About Oral Health Care Among Nursing Home Personnel - An Area in Need of ImprovementSaravanan ThangarajanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document7 pagesJurnal 1Liza MaisyuraNo ratings yet

- Acmph 1 101Document5 pagesAcmph 1 101Adnan SaffiNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge Attitude and Perception of Dental Students Towards Obesity in Kanpur CityDocument6 pagesAssessment of Knowledge Attitude and Perception of Dental Students Towards Obesity in Kanpur CityAdvanced Research PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics & TherapeuticsDocument7 pagesPediatrics & TherapeuticsAmit PasiNo ratings yet

- Factors in Uencing Satisfaction With The Process of Orthodontic Treatment in Adult PatientsDocument9 pagesFactors in Uencing Satisfaction With The Process of Orthodontic Treatment in Adult PatientsLikhitaNo ratings yet

- Attitude ArticleDocument9 pagesAttitude Articlemeena syedNo ratings yet

- Amhsr 2 14Document5 pagesAmhsr 2 14Archana KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Interceptive Orthodontic Treatment in Reducing MalocclusionsDocument8 pagesEffectiveness of Interceptive Orthodontic Treatment in Reducing MalocclusionsAriana de LeonNo ratings yet

- Alighieri 2020Document10 pagesAlighieri 2020Natalia AlberoNo ratings yet

- Use of EConsult To Enhance Genetics Service Delivery in PR 2022 Genetics inDocument8 pagesUse of EConsult To Enhance Genetics Service Delivery in PR 2022 Genetics inronaldquezada038No ratings yet

- Oralcareforin PatientsDocument7 pagesOralcareforin PatientsCristina MihaiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0882596322001294 IngDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0882596322001294 IngFlavio Augusto SerraNo ratings yet

- Junal Pico 1 KariesDocument9 pagesJunal Pico 1 KariesAnonymous 5qI7toeVzNo ratings yet

- Prevalencia y Distribución de HMI en CaracasDocument9 pagesPrevalencia y Distribución de HMI en CaracasDanitza GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- 10 1002@jdd 12254Document7 pages10 1002@jdd 12254Bernard HerreraNo ratings yet

- Ajnr 130Document16 pagesAjnr 130GRF PUBLISHERSNo ratings yet

- Ref 7Document19 pagesRef 7indah anggarainiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0882596321003262 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0882596321003262 Maingczywtxd4pNo ratings yet

- Dental Status of Children Receiving School Oral Health Services in TshwaneDocument7 pagesDental Status of Children Receiving School Oral Health Services in TshwaneTy WrNo ratings yet

- Factoring Patient Compliance PDFDocument11 pagesFactoring Patient Compliance PDFneetika guptaNo ratings yet

- Ipd 12715Document10 pagesIpd 12715Ayu DamayNo ratings yet

- Chen 2019Document9 pagesChen 2019Tiara HapkaNo ratings yet

- The Use of General Anesthesia For Pediatric Dentistry in Saskatchewan: A Retrospective StudyDocument9 pagesThe Use of General Anesthesia For Pediatric Dentistry in Saskatchewan: A Retrospective StudyAbi de la PeñaNo ratings yet

- Archive of SIDDocument6 pagesArchive of SIDBeuty SavitriNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Referral Patterns of General Dentists: Lessons For Dental EducationDocument12 pagesPeriodontal Referral Patterns of General Dentists: Lessons For Dental EducationVio VisanNo ratings yet

- Safeguarding Children in Dentistry: 2. Do Paediatric Dentists Neglect Child Dental Neglect?Document6 pagesSafeguarding Children in Dentistry: 2. Do Paediatric Dentists Neglect Child Dental Neglect?bkprosthoNo ratings yet

- BrazilDocument7 pagesBrazilkarinagitakNo ratings yet

- Previous Radiographic Experience of Children Referred For Dental Extractions Under General Anaesthesia in The UKDocument3 pagesPrevious Radiographic Experience of Children Referred For Dental Extractions Under General Anaesthesia in The UKLily BrostNo ratings yet

- Patient's Expectation of Orthodontic Treatment at A Tertiary Health Facility in Lagos, NigeriaDocument6 pagesPatient's Expectation of Orthodontic Treatment at A Tertiary Health Facility in Lagos, NigeriadochetNo ratings yet

- Adj 12749Document10 pagesAdj 12749Irfan HussainNo ratings yet

- HSDC QuintesenceDocument6 pagesHSDC QuintesenceDavid CasaverdeNo ratings yet

- Froh 02 656530Document11 pagesFroh 02 656530Alexandru Codrin-IonutNo ratings yet

- Parent Escalation of Care For The Deteriorating Child in Hospital: A Health Care Improvement StudyDocument11 pagesParent Escalation of Care For The Deteriorating Child in Hospital: A Health Care Improvement Studybhazferrer2100% (1)

- 7 - Quantitative Assessment of The EffectivenessDocument8 pages7 - Quantitative Assessment of The Effectivenessanhca4519No ratings yet

- P WorkforceissuesDocument5 pagesP WorkforceissuesfaizahNo ratings yet

- Swoope1977 PDFDocument8 pagesSwoope1977 PDFKrupali JainNo ratings yet

- India Evaluation of Public Awareness, Knowledge andDocument8 pagesIndia Evaluation of Public Awareness, Knowledge andMax FaxNo ratings yet

- Working Practices and Job Satisfaction of Victorian Dental HygienistsDocument6 pagesWorking Practices and Job Satisfaction of Victorian Dental Hygieniststea metaNo ratings yet

- Childhood Caries Management in The European UnionDocument10 pagesChildhood Caries Management in The European Unionrossanamns622No ratings yet

- 3 - Reco Anglaise Lyell EnfantsDocument34 pages3 - Reco Anglaise Lyell Enfantsedwin fernando pestana tiradoNo ratings yet

- Article 12Document6 pagesArticle 12ROSANo ratings yet

- Other Journals in Brief: Research InsightsDocument1 pageOther Journals in Brief: Research InsightsyoiNo ratings yet

- Longetivity of DentureDocument9 pagesLongetivity of DentureShyam DangarNo ratings yet

- JPM 11 00452Document12 pagesJPM 11 00452Putu Gyzca PradyptaNo ratings yet

- 2022 Article 721Document8 pages2022 Article 721cosadedubsNo ratings yet

- NHS England Paediatric DentistryDocument15 pagesNHS England Paediatric DentistryDina ElkharadlyNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Level of Medical-Emergency-RelatedDocument10 pagesMeasuring The Level of Medical-Emergency-RelatedVidyandika PermanasariNo ratings yet

- 03 Knowledge Attitudes and Behavior Towards Oral Health Among A Group of Staff Caring For Elderly People in Long Term Care Facilities in Bangkok ThailandDocument16 pages03 Knowledge Attitudes and Behavior Towards Oral Health Among A Group of Staff Caring For Elderly People in Long Term Care Facilities in Bangkok ThailandFadli AlwiNo ratings yet

- F1000research 9 55792Document22 pagesF1000research 9 55792Tsaniya KamilahNo ratings yet

- archivev3i3MDIwMTMxMDIy PDFDocument9 pagesarchivev3i3MDIwMTMxMDIy PDFLatasha WilderNo ratings yet

- Implementation of A Was Not Brought' Pathway in Paediatric DentistryDocument5 pagesImplementation of A Was Not Brought' Pathway in Paediatric DentistryYaman HassanNo ratings yet

- AAPD Teledentistry 2021Document2 pagesAAPD Teledentistry 2021Francisca Abarca CifuentesNo ratings yet

- Atraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART) in Pediatric Dentistry Residency Programs: A Survey of Program DirectorsDocument7 pagesAtraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART) in Pediatric Dentistry Residency Programs: A Survey of Program DirectorsrizkiNo ratings yet

- Reforming Dental Health Professions EducationDocument25 pagesReforming Dental Health Professions EducationSanaFatimaNo ratings yet

- Non-pharmacological behaviour management - 副本Document37 pagesNon-pharmacological behaviour management - 副本刘雨樵No ratings yet

- Children - Free Full-Text - Importance of Desensitization For Autistic Children in Dental PracticeDocument2 pagesChildren - Free Full-Text - Importance of Desensitization For Autistic Children in Dental Practicestivensumual0701136055No ratings yet

- Phadraig Et Al 2019 - Systematic DesensitizationDocument16 pagesPhadraig Et Al 2019 - Systematic DesensitizationCarlindo e CarlindoNo ratings yet

- Treatment Planning in Restorative Dentistry and Implant ProsthodonticsFrom EverandTreatment Planning in Restorative Dentistry and Implant ProsthodonticsNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Impact of COVID-19 On Dental Antibiotic Prescribing Across England - 'It Was A Minefield'Document6 pagesUnderstanding The Impact of COVID-19 On Dental Antibiotic Prescribing Across England - 'It Was A Minefield'Mohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- The Versatility of Flowable Composites. Part 2 - Clinical UsesDocument4 pagesThe Versatility of Flowable Composites. Part 2 - Clinical UsesMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- The Dental Effects of Head and Neck Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment - A Case SeriesDocument6 pagesThe Dental Effects of Head and Neck Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment - A Case SeriesMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation Challenge in Patient With High Smile Line: Case Report and Review of Surgical ProtocolsDocument8 pagesRehabilitation Challenge in Patient With High Smile Line: Case Report and Review of Surgical ProtocolsMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue Calcification Seen On Dental RadiographsDocument4 pagesSoft Tissue Calcification Seen On Dental RadiographsMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Pub BassamHassan YMPR2177Document12 pagesPub BassamHassan YMPR2177Mohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Is There Clinical Evidence To Support Alveolar Ridge Preservation Over Extraction Alone? A Review of Recent Literature and Case Reports of Late Graft FailureDocument6 pagesIs There Clinical Evidence To Support Alveolar Ridge Preservation Over Extraction Alone? A Review of Recent Literature and Case Reports of Late Graft FailureMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Recognition and Management of Drug-Associated Oral Ulceration - A ReviewDocument5 pagesRecognition and Management of Drug-Associated Oral Ulceration - A ReviewMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Intentional Replantation - An Underused Modality?Document7 pagesIntentional Replantation - An Underused Modality?Mohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Disease - The Profession's ChoicesDocument2 pagesDiabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Disease - The Profession's ChoicesMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- A 5-Year Observation of The Dahl Principle To Manage Localized Anterior Tooth WearDocument5 pagesA 5-Year Observation of The Dahl Principle To Manage Localized Anterior Tooth WearMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- An Update On Record KeepingDocument4 pagesAn Update On Record KeepingMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Flangeless Horseshoe Maxillary Complete Denture - A Prosthodontic Solution To Maxillary ToriDocument3 pagesFlangeless Horseshoe Maxillary Complete Denture - A Prosthodontic Solution To Maxillary ToriMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Broken Needle - A Rare Complication of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block - A Report of Two CasesDocument4 pagesBroken Needle - A Rare Complication of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block - A Report of Two CasesMohammad Abdulmon’emNo ratings yet

- Improving A Classroom-Based Assessment TestDocument27 pagesImproving A Classroom-Based Assessment TestRodel Yap100% (1)

- Kampamba Kasamba Possition PaperDocument5 pagesKampamba Kasamba Possition PaperCLANSIE BUXTON CHIKUMBENo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment E-Marketing July 2020Document2 pagesIndividual Assignment E-Marketing July 2020Hafsah Ahmad najibNo ratings yet

- Mã đề 103Document5 pagesMã đề 103yangyang2k4No ratings yet

- At The End of The Lesson, The Learners Should Be Able ToDocument4 pagesAt The End of The Lesson, The Learners Should Be Able ToHarold Nalla HusayanNo ratings yet

- How Social Workers WomanDocument22 pagesHow Social Workers WomanSheroze DogerNo ratings yet

- Tugasan KK TSLB3163 2020Document4 pagesTugasan KK TSLB3163 2020Sri Darsshane Raj Sivasubramaniam100% (1)

- Expectation and Motivation of Maritime Students in Pursuing Maritime EducationDocument51 pagesExpectation and Motivation of Maritime Students in Pursuing Maritime EducationJullie Carmelle ChattoNo ratings yet

- Job Vacancies at African Rural UniversityDocument4 pagesJob Vacancies at African Rural UniversityThe Campus TimesNo ratings yet

- Placemats: "They Are Not Just For Dining"Document7 pagesPlacemats: "They Are Not Just For Dining"Nor HazimahNo ratings yet

- Assignment Project Spring 2010 11Document3 pagesAssignment Project Spring 2010 11Andreas PittasNo ratings yet

- Department Of: ButationDocument140 pagesDepartment Of: ButationGLORIA VALERANo ratings yet

- For Social Innovation: Author Kyriaki PapageorgiouDocument72 pagesFor Social Innovation: Author Kyriaki PapageorgiouMonica Grau SarabiaNo ratings yet

- Eng PostgradDocument102 pagesEng PostgradKM_147No ratings yet

- 21 - PHAN Le Hai Ngan - CHALLENGES - CONSTRAINTS PDFDocument11 pages21 - PHAN Le Hai Ngan - CHALLENGES - CONSTRAINTS PDFWoo TungNo ratings yet

- Module 7.implementationDocument18 pagesModule 7.implementationBuried_Child100% (2)

- Application ProcessDocument2 pagesApplication ProcessMaheeshNo ratings yet

- Teaching Mathematics Using Blended Learning Model: A Case Study in Uitm Sarawak CampusDocument6 pagesTeaching Mathematics Using Blended Learning Model: A Case Study in Uitm Sarawak CampusfairusNo ratings yet

- Prepared By: Cabasag, Rubie C., MM, LPTDocument9 pagesPrepared By: Cabasag, Rubie C., MM, LPTGlaiza Kaye SalazarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Nigerian CultureDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Nigerian Culturevehysad1s1w3100% (1)

- Scholastic Aptitude Tests (Sats) & English Proficiency Tests (Toefl, Ielts)Document5 pagesScholastic Aptitude Tests (Sats) & English Proficiency Tests (Toefl, Ielts)Gayathri GayuNo ratings yet

- CV of M RajuDocument3 pagesCV of M RajuMd Zahidul AhsanNo ratings yet

- Talahanayan NG Ispesipikasyon: NilalamanDocument2 pagesTalahanayan NG Ispesipikasyon: NilalamanErna Mae AlajasNo ratings yet

- Principal'S Monthly Report On Enrolment and Other School Data (Enhanced Form 3)Document12 pagesPrincipal'S Monthly Report On Enrolment and Other School Data (Enhanced Form 3)Zion HillNo ratings yet

- Application No. 2024016946: Application Form For B.Tech. Admissions - 2024Document2 pagesApplication No. 2024016946: Application Form For B.Tech. Admissions - 2024sankarshanNo ratings yet

- GueorguievDocument8 pagesGueorguievAdel ToumiNo ratings yet

- FDP-2024 ScheduleDocument1 pageFDP-2024 Schedulelakshmi cnNo ratings yet