Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hambrick 1982

Hambrick 1982

Uploaded by

nazninOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hambrick 1982

Hambrick 1982

Uploaded by

nazninCopyright:

Available Formats

Strategic Attributes and Performance in the BCG Matrix--A PIMS-Based Analysis of

Industrial Product Businesses

Author(s): Donald C. Hambrick, Ian C. MacMillan and Diana L. Day

Source: The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Sep., 1982), pp. 510-531

Published by: Academy of Management

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/256077 .

Accessed: 08/05/2014 22:02

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Academy of Management is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Academy

of Management Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

? Academy of Management Journal

1982, Vol. 25, No. 3, 510-531.

Strategic Attributes

and Performancein

the BCG Matrix-

A PIMS-Based Analysis of

Industrial Product Businesses

DONALD C. HAMBRICK

IAN C. MacMILLAN

DIANA L. DAY

Columbia University

Thispaper empiricallyexploresthe performanceten-

denciesand strategicattributesof businessesin thefour

cells of the Boston ConsultingGroupproductportfolio

matrix. Businesses differed in their performance and

strategicattributes,accordingto the two dimensionsof

the BCG matrix-product life cycle stage (growthrate)

and marketshare.

Most discussionsof business-levelstrategyfall into one of threegroups.

Firstare normativepropositionsabout whichstrategicactionsmake sense

under different conditions. These prescriptionstypicallyare set forth by

seasonedobserversof organizations(Andrews,1971;Glueck, 1976;Katz,

1970), but, so far, creationof these ideas has substantiallyoutpacedem-

piricaltests of theirvalidity.A second categoryof literatureis empirically

based, but aimedat demonstratinguniversal"laws" of strategy.Findings

on the pervasivepositiveeffects of marketshare(Chevalier,1972;Schoef-

fler, Buzzell,& Heany, 1974)and the experiencecurve(Boston Consulting

Group, 1968)are primaryexamples.The thirdgroup also is empiricalbut

concludesthat so manycontingentfactorsexist that strategymustbe high-

ly situational (Hatten, Schendel, & Cooper, 1978). In the latter vein,

Hofer (1975) set forth what he consideredto be a manageablelist of 20

contingent factors (narrowed down from 54) that affect strategy for

'The authors gratefully acknowledge sponsorship by the Strategy Research Center, Columbia Uni-

versity Graduate School of Business, and generous support from the Strategic Planning Institute,

Cambridge, Mass. Thomas Lenz, William Newman, Max Richards, Sidney Schoeffler, and Michael

Tushman made helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

510

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 511

mature businesses. All possible combinations of these (assuming only two

values per variable) result in over a million possible configurations.

What is needed are empirically based "mid-range" theories about busi-

ness-level strategy. As Bourgeois noted, "The solution is for the re-

searcher to abstract a smaller number of more encompassing conceptual

categories with a broader range of generalizability" (1980, p. 29). This

paper pursues that advice by focusing on only two key contingent varia-

bles-the product life cycle and market share-and identifying their rela-

tionships with different strategic attributes and performance. The term

"strategic attributes" is preferred to "strategic action" because this essen-

tially is a cross-sectional study in which an array of strategic variables, in-

cluding those that are controllable only in the longer term (e.g., capital in-

tensity, productivity) are examined.

In the literature on business-level strategy, probably no constructs have

been deemed more significant than market share and the product life

cycle. However, there is little empirical research treating these as contin-

gent factors. The choice of these two constructs has the added advantage

that, taken together, they form the framework for a widely known model

for analyzing corporate strategy-the Boston Consulting Group (BCG)

product portfolio matrix (Henderson, 1979). (Purely speaking, the vertical

dimension of the BCG matrix is "market growth." For most products,

growth rates closely correspond with certain stages of the life cycle. The

conceptual distinction is that each stage typically is attributed with charac-

teristics in addition to growth rate, for example, customer adoption rates

and the nature of competition. The emphasis here on life cycle stage is not

inconsistent with BCG's strict emphasis on market growth.) If both the

product life cycle and market share have major significance, and if many

firms actually conceive of businesses along these two dimensions, then this

study has the potential for generating empirically strong and managerially

meaningful results.

Two broad questions are addressed in this paper:

1) How do businesses in the four cells of the BCG matrix tend to differ

in their performance on various key criteria (profitability, risk, cash

flow, market share change)?

2) How do businesses in the four cells of the BCG matrix tend to differ

in their strategic attributes?

A third research question, which follows from the first two, is addressed

in a companion paper (MacMillan, Hambrick, & Day, 1982).

3) Which strategic attributes are associated with the various perfor-

mance measures in each cell of the matrix?

Theoretical Review

Business-Level Strategy

The distinction between corporate-level strategy (what businesses to be

in) and business-level strategy (how to compete in a given business) is

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

512 Academy of Management Journal September

established(Hofer & Schendel,1978;Vancil, 1976).This study focuses on

business-levelstrategy,whichis of interestto strategicunits(typicallydivi-

sions) in multibusinessfirms, or to single businessfirms. Although busi-

ness-level strategycenterson the conceptof "competing,"it is important

to stressthat it encompassesall the functionalareasof the business. Op-

tions in operations,marketing,distribution,R&D,finance, and personnel

all determinethe business'sbasis for competing.

ContingencyTheories

Contingencymodels, in whichthe appropriatenessof certainactionsare

deemedcontingenton particulargiven conditions, abound in the field of

organizationaltheory(Ford& Slocum, 1977).Relativelylittleprogresshas

been made in investigatingcontingent models of strategy. Hofer (1975)

made an eloquentcall for such research,and he also providedhis own no-

tions of what types of relationshipsmight exist. However,since his paper

appeared,essentiallyall empiricalinvestigatorsof business-levelstrategy

have had goals other than identifyingand testingcontingencies(Hattenet

al., 1978;Lenz, 1978;Miles& Snow, 1978).A notableexceptionis Harri-

gan's (1981)researchon factorsaffectingthe appropriatenessof different

strategiesin decliningindustries.

It is not clear which contingent variables will lead to the strongest

theory. Hofer (1975)lists 10 to 20 variables(dependingon life cycle stage)

in severalcategories:market,consumer,industrystructure,competition,

suppliers,macroenvironmental,and organizationalcharacteristics.Hofer

surmisedabout the importanceof each variablewithinits categorybut did

not suggestan overallpriority.He did proposethat "the most fundamen-

tal variablein determiningan appropriatebusinessstrategyis the stage of

the productlife cycle" (1975, p. 798).

ProductLifeCycle

The concept of the product life cycle is well established(Fox, 1973;

Hofer, 1975; Levitt, 1965; Wasson, 1974). Although scant empiricalre-

searchhas been done on the life cycle, theoristshave set forth an abun-

dance of prescriptionsabout which strategicbehaviorslead to success at

each stage.

For the early stages (introductoryand growth), theoristsgenerallylay

emphasison strategicactions aimed at gaininga strongcompetitivefoot-

hold, such as aggressivepricing, buildingcapacity, heavy marketingex-

penditures,and productR&D.For the laterstages(maturityand decline),

the emphasisis on extending/expandingthe productcategoryand seeking

efficienciesvia addingchannels,broadeningthe productline, verticallyin-

tegrating,avoidingpricecuts, and so on (Clifford, 1971;Fox, 1973;Hen-

derson, 1979;Wasson, 1974). Again, these prescriptionshave been based

more on seasonedobservationthan on systematicresearch.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 513

There are common threads, but there also are various prescriptivein-

consistenciesamong life cycle theorists.For example,Wasson(1974)calls

for cost cuttingaccompaniedby pricecuttingin the maturitystage, where-

as Fox (1973) encouragesprice maintenance.Clifford (1971) claims that

"vigorous" advertisingand sales efforts are crucialin the growth stage,

yet Patton says that "marketingsteps to the centerof the stage" during

the maturitystage (1959, p. 12). Not only are thereunresolveddifferences

among theorists, but there also are confusing stances within given

theorists' prescriptions.For example, Wasson encouragesmature busi-

nesses to seek new markets,productexpansions,productimprovements,

and cost reductions.This array of suggestionsis so encompassingas to

leavethe strategistwith little senseof priorities,or any senseof whatmight

actuallywork.

MarketShare

Marketsharewas selectedas the second contingentfactor in this study,

on the rationalethat marketshare has been demonstratedempiricallyto

be a key factoraffectingthe performanceof businessunits. Althoughit is

possiblefor businessesto have (or buy) moremarketsharethan is optimal

(Fruhan,1972),the weightof evidenceindicatesthat high sharebusinesses

have significantlyhigherearningsthan do low sharebusinesses(Chevalier,

1972; Schoeffler et al., 1974). Hofer (1975) endorsesthe importanceof

marketshareby listing it as dominantamong all the organizationalattri-

butes he would include in contingencymodels for all except brand new

businesses.

Verylittle systematicresearchhas been conductedon differentstrategies

for differentsharepositions. Bloom and Kotler(1975), drawingon anec-

dotal evidence,counseledhigh sharecompaniesto evaluatethe risks(pri-

marilyregulatoryand public pressure)of their dominantpositions and to

adjusttheirsharesin light of those risks. Conversely,Hamermesh,Ander-

son, and Harris(1978)outlinedstrategiesfor low sharebusinesses.Based

on anecdotes, they offered these suggestionsto underdogs:conduct nar-

rowly targeted R&D; limit growth; diversify cautiously; and recruit a

strong-willed,hands-onchief executive.Theseauthors'prescriptionshave

an intuitiveallure, yet they are neitherprecisenor systematicallyderived.

Foremost, there is no indicationwhy they have any more applicabilityto

high share(or low share)businessesthan to others. A recent, more syste-

matic study by Woo and Cooper (1980)identifiesdiscreteclustersof high

performing,low share businesses,and it contraststhem with clustersof

low performing,low share businessesand high performing,high share

businesses.Their paper is a step toward more accurateunderstandingof

issues associatedwith marketshare.

Combiningthe Two Dimensions:The BCG Matrix

The choice of the product life cycle and market share as the two contin-

gent variables has an added attraction. When combined, they form the

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

514 Academy of Management Journal September

framework for the BCG's product portfolio matrix (Henderson, 1979).

Although the matrix has limitations (Hofer & Schendel, 1978), it is widely

cited in academic and popular discussions of strategy. Other more refined

portfolio matrices, such as those used by Arthur D. Little (Patel &

Younger, 1978), Royal Dutch Shell (Robinson, Hickens, & Wade, 1978),

and General Electric (Taylor, 1976) generally are consistent with the BCG

framework, because they all incorporate an "attractiveness" dimension

(broader than, but encompassing, life cycle) and a "competitive position"

dimension (broader than, but encompassing, market share).

There is not unanimity as to what the dividing points on the two dimen-

sions of the matrix should be. BCG favors 10 percent real market growth

as the point of distinction between high and low market growth. The

group views market share in terms of the ratio of the share held by the

business relative to the share held by its leading competitor. A ratio of 1.0,

indicating highest market share, is commonly considered the dividing line

between high and low share. BCG also states that a ratio of 1.5 is neces-

sary to claim and exploit true dominance in a market (Hedley, 1977). In

the absence of systematic data on alternatives, the present study relies on

the 10 percent market growth rate and 1.0 relative market share as the

dividing points in the matrix.

Although a great deal has been written about the BCG matrix (and less

so about other portfolio matrices), the emphasis has been on how to allo-

cate resources among the four cells and what kinds of performance pat-

terns to seek for each. High share/low growth businesses (Cash Cows), for

example, should be managed for maximum generation of cash, and that

cash should be directed to newer, higher growth businesses (Wildcats and

Stars). Low growth/low share Dogs are seen as serious cash drains that

should be promptly harvested, liquidated, or divested.

No systematic evidence exists about whether the performance tenden-

cies of businesses in the four cells actually allow or warrant these prescrip-

tions. No information exists about the strategic tendencies of businesses in

the four cells. The goal of the present paper is to fill these voids in part. In

doing so, it will form the backdrop for a companion paper on the relation-

ships between strategic attributes and performance for each of the four

cells.

At this stage, it is not appropriate to set forth all plausible hypotheses.

However, two broad propositions may be stated: (1) Businesses in the

four cells will differ systematically in their performance (including in their

cash flow tendencies as argued by BCG); (2) Businesses in the four cells

will differ in their strategic attributes. Previous literature which should

contribute to more specific hypotheses has been speculative, imprecise,

and even contradictory. And the range of strategic variables and perfor-

mance measures to be examined make an inventory of hypotheses un-

wieldy. Thus, the approach will be to treat this as an exploratory study to

enhance understanding of a widely recognized but little-documented, stra-

tegic framework.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 515

Method

ThePIMSDataBase

The data used in this study weredrawnfrom the Profit Impactof Mar-

ket Strategies(PIMS)project, an ongoing study of environmental,strate-

gic, and performancevariablesfor individualbusiness units. About 200

corporationssubmitdata annuallyon a total of about 2,000 of theirbusi-

ness units. Each business, often a division, is a distinct product-market

unit. For a technical summaryof the PIMS data base, see Schoeffler

(1977).

Andersonand Paine (1978) providea comprehensivecriticalreviewof

the PIMS data base. Most of theirconcernsare about how the PIMS data

had been statisticallyanalyzed and presented in previous studies. Al-

thoughthey raiselimitedconcernsabout the qualityof the data, they gen-

erallyacknowledgethe data base to be of high qualityand reliability.Two

factors that previouscriticshave not noted especiallycommendthe data.

First, PIMS staffershelp each businessinterpretand answerthe questions,

thus assuringa high degreeof data comparability.This featureis missing

from conventionalquestionnairestudies. Second, each company pays a

substantialsum to participatein PIMS, and the softwareis orientedsuch

that theirabilityto derivemeaningfulconclusionsfrom the data is particu-

larly a function of the accuracyof their own data. The businesseswould

appearto have a commitmentto thoroughnessand accuracythat is miss-

ing in most surveystudies. No conventionaltests of the reliabilityof the

data base (e.g., test-retest,multiplerespondentconsistency)are knownto

have been conducted.

The data base does have some limitations,includingthose noted by An-

derson and Paine. Foremost, the businessesin the data base cannot be

viewed as typicalof businessunits in general.On average,the participat-

ing businessesprobably are more sophisticated,more dominant within

their markets,and more effective in generalthan the total populationof

businessin the United States.

Categorizing the Businesses

The studyreportedhere is based on the most recentfour yearsof PIMS

data for businesses that manufactureindustrial products. Further re-

search,in progress,will extendthe analysisto the consumerproductsec-

tor.

The businessesin the sample were classified into the four cells of the

BCG matrixaccordingto their life cycle stage (marketgrowth rate) and

relativemarketshare. PIMS respondentsindicatethe business'slife cycle

stage by answeringthis question: "How would you describethe stage of

developmentof the types of productsor servicessold by this businessdur-

ing the last three years?"

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

516 Academy of Management Journal September

-Introductory stage: Primary demand for product just starting to

grow; product/servicesstill unfamiliarto many potentialusers

-Growth stage:demandgrowingat 10 percentor moreannuallyin real

terms;technologyor competitivestructurestill changing

-Maturity stage:Productsor servicesfamiliarto vast majorityof pro-

spective users; technology and competitive structure reasonably

stable

-Decline stage: Productsviewedas commodities;weakercompetitors

beginningto exist.

Responsesto this straightforwardcategorizingquestionwereused in the

analysis. A more elaborate index for measuringlife cycle stages from

PIMS data has been shownto yield strikinglyequivalentresults(Christen-

sen, 1977).

The data base has relativelyfew businessesin the introductoryand de-

cline stages, so the study includedonly those in the growth and maturity

stages, a total of 1,028. Even though the label "life cycle" is being used,

the classificationis fully consistentwith BCG'sview of this as the "market

growth" dimension,becausepart of the PIMS definitionaldistinctionbe-

tween a growthbusinessand a maturebusinessis a realgrowthratein pri-

marydemandof 10 percent.

Relativemarketshareis defined as the ratio of the unit's marketshare

relativeto the shareof its leadingcompetitor(usinga four-yearaverage).

A relativemarketsharefigureof greaterthan 1.00 is consideredhigh rela-

tive marketshare; 1.00 or below is classifiedas low relativemarketshare.

The averagerelative share for the entire sample is 1.30 (supportingthe

speculationthat PIMS businessesare relativelydominant),and the stan-

dard deviationis 1.68, indicatingthat the businessesare not too heavily

clusteredaroundthe 1.0 dividingline. The four subsamplesare portrayed

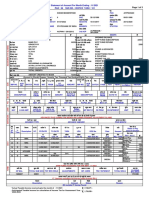

in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The Subsamples of Industrial Products Businesses Studied

Stars Wildcats

Growth N=114 N=181

Product Real

Life Growth

Cycle 10% Year

Mature Cash Cows Dogs

N=315

N=3418

High 1.0 Low

Relative Market Share

Variables

Two types of variables are distinguishedin this study-strategic at-

tributes and performance. Environmentalvariables are not included.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 517

As uncontrollables, they amount to additional contingent factors that

must be systematically treated in future studies.

The PIMS data base includes data on dozens of strategic attributes.

Only variables that have been prominent in previous PIMS findings or in

other strategy studies (e.g., product quality, capital intensity, capacity

utilization) were included in this study.

The strategic attributes, as grouped for analysis and discussion, are as

follows:

Resources and Resource Usage Expense Structure

Investment/revenue Manufacturing/revenue

Plant and equipment newness Product R&D/revenue

Capacity utilization Process R&D/revenue

Capacity/market size Sales force/revenue

Sales/employee Advertising and promotion/revenue

Working Capital Management Competitive Devices

Receivables/revenue Sales from new products

Inventory/revenue Relative sales from new products

Domain Relative prices

Relative product line breadth Relative direct costs

Relative customer type breadth Relative image

Relative number of customers Relative services

Customer fragmentation Relative advertising expenses

Vertical Integration Relative promotion expenses

Value/added revenue Relative sales force expenses

Relative integration backward

Relative integration forward

The definitions of the strategic attributes can be obtained from the au-

thors. In all cases, four year averages were used. Four performance mea-

sures were examined:

(1) Return on investment (ROI) (average of last two years): Pretax net

income minus allocated corporate overhead costs, as a percent of average

investment including fixed and working capital at net book value.

(2) Cash flow on investment (CFOI) (average of last two years): After-

tax income (estimated at 50 percent of pretax income) minus changes in

net investment, as a percentage of average investment.

(3) Return per risk (RPR): Average ROI divided by the variability of

ROI (calculated as the sum of the absolute differences between the four-

year average ROI and each year's ROI).

(4) Market share change (MSC): The change (annualized via least

squares) in this business's average share of the market (expressed as a per-

centage of the market) for the four-year period.

The rationale for using two-year averages for ROI and CFOI bears pri-

marily on the analyses to be reported in the companion paper (MacMillan

et al., 1982) and will be discussed there. The two-year vs. four-year time-

frame has little effect on the tendencies reported in this paper.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

518 Academy of Management Journal September

Method of Analysis

Reportingof means, with two-way analysis of variance, was used to

identify any tendenciesfor the four types of businessesto differ in their

performanceor strategicattributes,eitheraccordingto life cycle stage or

marketshare. Zero-ordercorrelationsamong performancemeasuresfor

each cell also are reported.

Results and Discussion

Performance Across the Four Cells

This study empiricallycorroboratesthe primarytheme espousedby the

originatorsof the BCG matrix (see Table 1): namely, the four types of

businesseshave significantlydifferenttendenciesto consume or generate

cash. The averageWildcathas a negativecash flow (-2.67 percent)["re-

quireslargecash inputs that it cannot generateitself" (Henderson,1979,

p. 164)].The averageStaressentiallygeneratesas muchcash as it uses (.74

percent) ["may or may not generate all of its own cash" (Henderson,

1979, p. 166)]. Cash Cows are net cash generators(10.10 percent)["gen-

eratelargeamountsof cash" (Henderson,1979,p. 164)].Theseresultsare

preinterestcharges(whicharenot reportedin the PIMSdata), and so must

be regardedas suggestingpatternsratherthan absolute figures.

The resultspresenta somewhatmorepositiveview of Dogs than that ex-

pressedby Henderson,who said that a Dog gives "no cash throwoff. The

productis essentiallyworthless,exceptin liquidation"(1979, p. 164). The

Dogs examinedin this study had averagenet positivecash flow on invest-

ment of 3.4 percent,whileholdingtheirmarketshares.Thiscashflow rate

from Dogs is more than is requiredto meet the cash needs of the average

Table 1

Performance Levels of Businesses

in the Four Cells of the BCG Matrix

(Means Reported, with Standard Deviations in Parentheses)

2- Way Anova

(Main Effects)

Wildcats Stars Cash Cows Dogs Life Cycle Market

Performance Measure (N= 181) (N= 114) (N= 315) (N= 418) Stage Share

Return on investment 20.55 29.58 30.00 18.48 **

(24.53) (22.59) (22.67) (21.68)

Cash flow on investment -2.67 .74 10.01 3.41 ** **

(18.79) (18.26) (17.03) (16.17)

ROI/ROI variability 2.37 3.96 4.57 2.80 ** **

(return per risk) (3.53) (5.20) (4.15) (4.68)

Market share change .39 .72 .38 .14 * *

(1.76) (2.97) (2.30) (1.55)

*p< .05

**p< .001

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 519

Wildcat(-2.67percent). If one assumesthat the absolutesize of the aver-

age Dog is largerthan the typical Wildcat (often fledgling operations),

then the absolute cash throw-off from some Dogs may be sufficient to

fund two or morepromisingnew ventures.It also shouldbe noted that the

standarddeviationof CFOI for Dogs is 16 percent,indicatingthat some

Dogs generatesubstantialamounts of cash. And the modest correlation

(r=-.07) betweenCFOI and MarketShareChange(Table2) for Dogs in-

dicates that cash flow can come other than through "harvesting."It ap-

pearsthat Dogs outperformthe expectationsplacedon them by BCG. In-

stead of focusing solely on harvestingor liquidationstrategiesfor Dogs,

researchersshould start dealing more positively and creativelywith this

type of business(e.g., Hamermeshet al., 1978;Woo & Cooper, 1980).

Consistentwith previousPIMS findings, ROI (reflectingaccrualprof-

its, not cash flow) was higherfor high sharethan for low sharebusinesses

(Buzzell, Gale & Sultan, 1975).Therewereno significantROI differences

across the two life cycle stages. Specifically, Stars (29.58) and Cows

(30.00) were roughly equal in outperformingWildcats(20.55) and Dogs

(18.48) on the ROI measure.

When ROI is adjusted for risk (4-year ROI variability),differences

acrossthe four cells reflectboth the profitabilityof high marketshareand

the profit stability of maturity. Cows score highest (4.57), due to their

dominancein relativelystable markets. Stars follow (3.96), due to their

dominance,but in turbulentmarkets.Dogs are next highest(2.80). Wild-

cats are lowest (2.37), reflectingtheirmoderateprofitabilityand unsettled

markets.These resultssupportthe establishedconcept that growth busi-

nesses are more uncertainthan maturebusinesses.They also reemphasize

the soundnessof carefullytendingmaturebusinesses-including Dogs.

Marketshare change was one of the performancemeasuresexamined.

As expected, there were indications of greater share increases in the

growthbusinessesthan in the maturebusinesses,reflectingboth the rela-

tively entrenchedpositions in matureindustriesand the presumedcharter

of maturebusinessesto seek primarilycash, not share. Also, high share

businessestended to gain more share than did their low share counter-

parts. Apparently,"the strong get stronger."Yet, there is no indication

that businessesattemptto gain or succeedin gainingtruly large sharein-

creases.In absoluteterms,the averageshareincreasesare modest(highest

is .72 percentfor Stars), as are the standarddeviations(highestis 3.0 per-

cent for Stars).A quest for a 5 percentto 10 percentshareincreaseappar-

ently is unusual,unrealistic,or both.

The results(Table 2) also shed light on the tradeoffs presumedto exist

betweenperformancemeasures,particularlycash flow and marketshare

gain. Nil correlationsbetween these two performancemeasuressuggest

that no realtradeoffexists(exceptfor Stars, for whichr= -.27, p< .01) or

that unaccountedfactors may be maskingindicationsof such a tradeoff.

The resultsalso indicatenil relationshipsbetween ROI and share change

for each cell. It is beyondthe scope of this paperto identifycircumstances

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

520 Academy of Management Journal September

Table 2

Relationships Among Performance Measures

(Pearson Correlation Coefficients)

Wildcats (N= 181)

ROI CFOI RPR MSC

ROI

CFOI .68** -

RPR .45** .54** -

MSC .13 -.07 -.03

Stars (N= 114)

ROI CFOI RPR MSC

ROI

CFOI .61**

RPR .39** .53**

MSC -.15 -.27* -.07

Cash Cows (N= 315)

ROI CFOI RPR MSC

ROI

CFOI .61*

RPR .38** .46**

MSC -.04 -.07 -.12 -

Dogs (N=418)

ROI CFOI RPR MSC

ROI

CFOI .57**

RPR .39** .45**

MSC -.06 -.05 -.02

*p<.01

**p< .001

or strategiesthat will allow marketshare and cash flow or profits to in-

creasetogether.Factorssuch as the magnitudeof an attemptedsharein-

crease, competitors'strategiesand goals, and product differentiationno

doubt are among those that futureresearchshould includeas moderating

variablesin studyingtradeoffs between profits and share changing. The

presentresultssuggestthat a tradeoff may not alwaysexist. The findings

also raisequestionsabout the extentto whichmanagersshould be relieved

of profitabilityor cash flow goals whenthey also are chargedwith gaining

share.

StrategicAttributesof the Four Cells

The resultsindicatea host of significantdifferencesin the strategicattri-

butes of the four types of businesses.Some of the attributes,includingal-

most all those expressedin terms "relativeto competitors," varied pri-

marilyaccordingto marketshare. Severalothers variedaccordingto life

cycle stage. Still othersvariedaccordingto both dimensionsof the matrix.

Care must be taken in tryingto interpretthe attributesas eithercauses

or effects of the business'sposition in the matrix.For example,it will be

observedthat high sharebusinesseshave relativelybroaderproductlines

and customertypes than do low share businesses.Because the data are

cross-sectional,there is no way to disentanglethe extent to which broad

product/marketbases precede,accompany,or follow marketdominance.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 521

Futurelongitudinaltreatmentof the PIMS data base could yield such in-

formation.

Resources and Resource Usage

It comes as no surprisethat high share businesseshave substantially

more of their markets'productioncapacitythan do low sharebusinesses

(Table 3). High sharebusinessesalso utilizetheir capacityat a higherrate

than do low sharebusinesses,probablyreflectingthe leaders'relativeease

in securingordersto fill capacity.The lower utilizationratesof low share

businessesindicate that those businesseseither built capacity in earlier

days when they held or anticipatedhighersharesor built capacityrecently

as part of a plan to gain share. That plant and equipmentnewness(net

P&E/gross P&E) varies accordingto the product life cycle, but not ac-

cordingto marketshare, suggeststhat low sharebusinessestypicallyhave

not engaged in recent capacity buildups, but ratherthey simply do not

have the marketpower to fill earlierbuilt capacitythe way a high share

businesscan.

Table 3

Strategic Attributes of Businesses

in the Four Cells of the BCG Matrix

(Means Reported, with Standard Deviations in Parentheses)

Resources and Resource Usage

2-Way Anova

(Main Effects)

Wildcats Stars Cash Cows Dogs Life Cycle Market

Strategic Attributes (N= 181) (N= 114) (N=315) (N=418) Stage Share

Capacity/market 20.37 56.61 52.03 21.27 ***

(16.37) (25.85) (25.96) (15.40)

Capacity utilization 73.36 75.28 78.09 75.14 * **

(16.88) (15.60) (14.23) (16.04)

Plant and equipment 59.24 58.93 50.58 51.40 ***

newness (15.80) (14.09) (14.26) (14.84)

Investment/revenue 63.93 60.05 51.35 56.06 *** **

(36.12) (27.66) (24.72) (27.33)

Sales/employee 63.22 63.92 55.37 59.06 *** **

(44.29) (39.50) (36.49) (40.68)

**p< .01

***p<.001

Maturebusinesseshave highercapacityutilizationratesthan do growth

businesses.This may reflectthe relativestabilityand equilibriumthat ex-

ists in matureindustries(as indicatedby relativemarketsharestabilityas

discussed above), and perhaps also an efficiency orientation in mature

businesses.

Becausethe numeratorof investment/revenue(capitalintensity)is mea-

suredin termsof net investment,it is not surprisingthat growthbusinesses

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

522 Academy of Management Journal September

have higher scores on this attribute than do mature businesses. Growth

businesses, on average, have newer, less depreciated assets [the correlation

between plant and equipment newness and investment/revenue was .34

(p>.01) for the entire sample, indicating a strong relationship between

newness and capital intensity]. The high capital intensity figure for growth

businesses also may reflect their presumably smaller revenue bases over

which they must spread investment. The disguised dollar figures in the

data base prevent any test of this speculation. To some extent, the finding

of high capital intensity for growth businesses runs counter to conven-

tional thought of businesses becoming more capital intensive over time, as

competition shifts to a volume or efficiency orientation.

The high sales/employee figure for growth businesses, compared to ma-

ture businesses, suggests that mature businesses have not dramatically re-

placed labor with capital assets. The higher employee productivity figure

for growth businesses may be partly attributable to the relatively stronger

pricing structure that exists in growth businesses (gross margins in growth

businesses average 30 percent, compared to 27 percent in mature busi-

nesses-a significant difference at the .05 level), which inflates their reve-

nue figures. Or Parkinson's Law may be operating: mature businesses are

choked with people (presumably administrators/staff) who, on average,

generate relatively little salable output.

Capital intensity is less for high share than for low share businesses.

This may reflect the smaller revenue bases of the low share businesses, or it

may suggest that low capital intensity provides flexibility and market re-

sponsiveness which, in turn, can lead to high market share.

Working Capital Management

Wildcats have a significantly higher receivables/revenue ratio than do

any of the other types of businesses (Table 4). This may reflect their at-

tempts to attract customers via liberal credit terms. This relatively

Table 4

Strategic Attributes of Businesses

in the Four Cells of the BCG Matrix

(Means Reported, with Standard Deviations in Parentheses)

Working Capital Management

2-Way Anova

(Main Effects)

Wildcats Stars Cash Cows Dogs Life Cycle Market

Strategic Attributes (N= 181) (N= 114) (N= 315) (N= 418) Stage Share

Receivables/revenue 17.62 15.62 15.15 15.13

(11.77) (8.80) (7.47) (8.89)

Inventories/revenue 20.90 18.61 19.87 22.01

(11.71) (10.54) (10.59) (11.45)

*p< .01

**p< .001

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 523

mundaneway of competingas a low sharebusinessapparentlyis not the

norm for Dogs. A possibleexplanationis that rigidcreditnormsbuild up

over an industry'slife cycle, discouragingunusualcreditpractices.

An indictingexplanationfor the relativelyhigh inventoriesheld by low

sharebusinessesis that these businessesareless adeptat managingtheirin-

ventories,whichin turnraisesthe questionof whetherthey are morepoor-

ly managedin general.Theirlow sharescould promptsuch a speculation,

but the data from this study do not necessarilysupportit. Another, more

charitable,explanationfor the highinventoriesheld by Wildcatsand Dogs

is that they attemptto compete,usingthose inventoriesfor readydelivery.

This is anotherexampleof a relativelymundanecompetitivedevice, aimed

at what Katz(1970)would call "going for the crumbs"-those customers

in which the dominantplayershave little interest.

ExpenseStructure

This study also included an examinationof the expense structuresof

businesses,or how they add value (Table 5). Resultsindicatedifferences

primarilyaccordingto life cycle stage, and less so by marketshare.

Table 5

StrategicAttributesof Businesses

in the Four Cells of the BCG Matrix

(Means Reported, with StandardDeviationsin Parentheses)

ExpenseStructure

2- Way Anova

(Main Effects)

Wildcats Stars Cash Cows Dogs Life Cycle Market

Strategic Attributes (N= 181) (N= 114) (N= 315) (N=418) Stage Share

Manufacturing/revenue 26.31 25.08 28.45 28.30 **

(12.06) (9.99) (11.50) (11.33)

Product R&D/revenue 2.63 2.76 1.68 1.76 *

(2.66) (2.51) (2.08) (2.28)

Process R&D/revenue .87 1.10 .53 .52 *

(1.24) (1.32) (.81) (.84)

Sales force expenditures/ 6.48 5.45 4.99 5.32 ** *

revenue (4.17) (4.21) (4.15) (4.35)

Advertising and promo- 1.02 .85 .71 .81 ** **

tion expense/revenue (1.15) (.93) (.92) (1.07)

*p< .05

**p<.01

***p<.001

Growthbusinessestend to spend proportionatelymore on what might

be called "future-oriented"expenses, that is, product R&D, process

R&D, advertising,and sales force, than do maturebusinesses.Threefac-

tors may be creatingthis difference.First, managersof growthbusinesses

may tend to view their businessesas having longer, brighterfuturesthan

do the managersof maturebusinesses,and thus they are more willingto

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

524 Academy of Management Journal September

incur costs that will have an impactonly in the future. This is not a con-

vincing rationale. Sales force and advertisingexpensespresumablyhave

some importantnearand currenttermpayoffs even for maturebusinesses.

A second possibilityis that many of these mature businessesare being

managedfor cash throwoff, accordingto BCG prescriptions,and there-

fore nondirectexpensesare minimized.A thirdinterpretationstems from

the semifixed, rather than variable, nature of most of these "future-

oriented"expenses.Thus, in growth businesses,which may have smaller

revenuebases than maturebusinesses,these expensestake on dispropor-

tionate magnitudewhen expressedas a percentageof sales. This line of

reasoningalso may explainwhy low sharebusinesses(withrelativelysmall

revenuebases) have higher sales force and advertisingexpensesthan do

high sharebusinesses.

Mature businesses add more value through manufacturingthan do

growthbusinesses.This is an indicationof the relativeemphasisof mature

businesseson the "core technology"(Thompson, 1967)or "engineering"

(Miles& Snow, 1978)aspectsof the businessratherthan on the "domain"

or "entrepreneurial"aspects. In light of this emphasis, it could be ex-

pected that maturebusinesseswould spend a relativelyheavy amount on

processR&D,in an attemptto maketheirthroughoutfunctionseven more

efficient (Utterback& Abernathy, 1975).As alreadyobserved,the oppo-

site is true. Maturebusinesses,on average,spend about half as much of

their sales dollarson processR&Das do growthbusinesses.One explana-

tion is that organizationalstructures,climates,and technologicalorienta-

tions either foster R&Din general,or they do not. That is, productR&D

and processR&Dtend to go hand in hand. This speculationpales in light

of the only moderatecorrelation(r= .24, p > .01) betweenthe two typesof

R&Dexpensesfor the entiresample.

Anotherpossibleexplanationfor the relativelylow processR&Dexpen-

dituresby maturebusinessesis that thesebusinessesarebeingmanagedfor

cash throwoff in industrieswith severeprice competition,such that even

expenditureson processR&Dare viewedas profit detractors.

Domain

The term "domain" is used as Thompson(1967)did, to referto the ar-

ray of productsand marketsa businessstakes out for itself. Becausethe

main domainvariablesin the PIMS data base are expressedin termsrela-

tive to the competition,no differenceswere expectedacross stages of the

life cycle and, in fact, none were observed(Table 6).

Differencesin the domain breadthsof low and high share businesses

weresignificant.Starsand Cash Cows reportedmore relativeproductline

breadth, customertype breadth, and relativenumberof customersthan

did their low share counterparts.Becausethis is a cross-sectionalstudy,

thereis no way of determiningwhethera broaddomainis a meansof gain-

ing share, or whetherdomain broadeningis an activitytypicallypursued

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 525

Table 6

Strategic Attributes of Businesses

in the Four Cells of the BCG Matrix

(Means Reported, with Standard Deviations in Parentheses)

Domain

2-Way Anova

(Main Effects)

Wildcats Stars Cash Cows Dogs Life Cycle Market

Strategic Attributes (N= 181) (N= 114) (N=315) (N=418) Stage Share

Relative product line 1.81 2.39 2.42 1.85 *

breadtha (.81) (.75) (.72) (.75)

Relative customer type 1.81 2.28 2.29 1.89 *

breadth (.62) (.65) (.66) (.59)

Relative number of 1.47 2.35 2.47 1.68 *

customers (.65) (.81) (.69) (.74)

Customer fragmentation 12.91 13.94 13.33 13.54

(10.32) (12.14) (11.51) (11.53)

aFor the sake of brevity and interpretability, means and ANOVA results are reported for ordinal

variables. A display of response distributions and chi-square statistics for the ordinal variables does

not suggest different patterns or conclusions.

*p < .001

by businesses that have already achieved dominance in a segment of a mar-

ket. What is clear is that the low share businesses tended toward "market

concentration" (Hofer & Schendel, 1978) or "focused" (Abell, 1980) stra-

tegies. They concentrated their efforts either because they recognized their

weak positions or were constrained by their weak positions.

There were no significant differences across the four cells in the

amounts of customer fragmentation, the variable that taps the extent to

which the business avoids relying on a few key customers. It could have

been expected that Wildcats, in particular, would have a small set of cus-

tomers with which they were establishing themselves. And, in fact, the

customer fragmentation score for Wildcats is the lowest (though not sig-

nificantly) of the four types. On average, though, none of the types has ex-

traordinarily more or less customer fragmentation than the others.

Vertical Integration

Just as high share businesses have broader domains than low share busi-

nesses, so do they also tend to be more vertically integrated (Table 7).

Their value added/revenue figures are higher than for low share busi-

nesses. And they indicate significantly more vertical integration (both

backward and forward), relative to their competition, than do low share

businesses.

As with domain breadth, there is no way of knowing from these data

whether vertical integration is a cause or an effect of high market share. A

reasonable speculation is that high share businesses tend to integrate ver-

tically to perpetuate their growth and that they integrate because their

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

526 Academy of Management Journal September

Table 7

Strategic Attributes of Businesses

in the Four Cells of the BCG Matrix

(Means Reported, with Standard Deviations in Parentheses)

Vertical Integration

2- Way Anova

(Main Effects)

Wildcats Stars Cash Cows Dogs Life Cycle Market

Strategic Attributes (N= 181) (N= 114) (N= 315) (N=418) Stage Share

Value added/revenue 56.13 61.14 59.57 54.77 **

(16.58) (13.63) (14.19) (14.84)

Relative V.I. backward 1.83 1.98 2.04 1.78 **

(.60) (.62) (.60) (.59)

Relative V.I. forward 1.89 1.97 1.99 1.92 *

(.52) (.50) (.49) (.47)

*p<.05

**p< .001

scale of operationsmakes it relativelydifficult to be assuredof outside

suppliesin the quantitiesand at the pricesthey desire(Williamson,1975;

Kreiken,1980).

Devices

Competitive

In examiningthe tendenciesof the four types of businessesto use vari-

ous competitivedevices,some strikingdifferencesare observed(Table 8).

Understandably,growth businesseshave highersales from new products

than do maturebusinesses.(Businessesin all four cells claim to have, on

average,highersales from new productsthan their competitors.This can

be reconciledonly by returningto the earliercontention that the PIMS

businessesare likelyto be more aggressive,and henceperhapsmore prone

to new productactivity, than are their non-PIMScompetitors.)Wildcats

have the highestnew productsales, and Dogs the lowest. This may reflect

a kind of self-fulfillmentof the BCG doctrine, in which Wildcats are

viewed, eitherby their own managersor their parentfirms' strategists,as

havingthe potentiallylongest and most rewardinghorizonsof any of the

four types, and thus most deservingof a new productorientation.Dogs,

typically viewed as having no promisingfuture (Henderson, 1979), are

viewed as not warrantingthe outlays associatedwith new products.

High sharebusinessesindicatethe relativelylow directcosts that should

accrue to them due to their accumulatedexperience(Henderson, 1979;

Hofer & Schendel, 1978). The typical prescriptionfor high share busi-

nesses in the growthstage is for them to drivecosts down and to price at

discouraginglylow levels. However,the Starsin the data base had relative-

ly high prices,perhapsreflectingthat they alreadywereestablishedleaders

insteadof strugglingfor leadership.Morebroadly,it warrantsnoting that

both Starsand Cash Cows are reapingdouble benefits from their market

power: relativelylow costs and relativelyhigh prices.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 527

Table 8

Strategic Attributes of Businesses

in the Four Cells of the BCG Matrix

(Means Reported, with Standard Deviations in Parentheses)

Competitive Devices

2- Way Anova

(Main Effects)

Wildcats Stars Cash Cows Dogs Life Cycle Market

Strategic Attributes (N= 181) (N= 114) (N= 315) (N=418) Stage Share

Sales from new products 18.66 18.16 7.31 7.82

(20.69) (20.73) (12.97) (13.68)

Relative sales from new 4.01 2.08 .79 .50

products (11.80) (10.19) (6.21) (7.08)

Relative prices 103.20 105.00 104.30 102.70

(7.02) (7.40) (6.37) (5.13)

Relative direct costs 104.30 99.52 100.20 103.20

(7.68) (8.38) (7.13) (6.93)

Relative product quality 22.03 45.12 34.25 17.64 * *

(29.18) (29.77) (28.56) (25.38)

Relative image 3.21 4.06 3.96 3.26

(.86) (.71) (.78) (.81)

Relative services 3.27 4.00 3.83 3.28

(.80) (.83) (.82) (.79)

Relative advertising 2.19 2.75 2.82 2.29

expenses (.99) (1.11) (.96) (.93)

Relative sales promotion 2.39 3.03 2.99 2.51

expenses (.93) (1.07) (.89) (.86)

Relative sales force 2.76 3.09 3.12 2.79

expenses (1.01) (1.04) (1.02) (.93)

*p< .001

Stars and Cows apparently command their high prices through a broad

array of superiorities. They claim to have higher average product quality,

image, and services than their low share competitors. They claim to spend

relatively more on advertising, sales promotions, and sales forces than

their lesser adversaries. All of these measures are ordinal and somewhat

impressionistic, so there is some likelihood that the market leaders falsely

attribute to themselves strength in all categories (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977).

Still, some of the apparent differences are substantial, and they tend to

square with expectations. Businesses with various strengths would be ex-

pected to gain market share and, once dominant, they would be expected

to reinforce and add strengths with the slack generated from market lead-

ership (Cyert & March, 1963).

Conclusions

This paper has attempted to test and extend the BCG product portfolio

matrix. The primary theme of BCG-that the four cells of the matrix have

quite different tendencies to generate or consume cash-has been cor-

roborated. Significant differences among the four cells on other perfor-

mance measures-return on investment, return per risk, and market share

change-also were observed. Thus, each of the four types in the matrix-

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

528 Academy of Management Journal September

Wildcats,Stars, Cows, and even Dogs-contributes in its own way to the

balancedperformanceof the corporation.Of particularnote is the finding

that the averageDog has a positive cash flow, even greaterthan the cash

needsof the averageWildcat.BCG'sschematic(Henderson,1979, p. 165)

portrayingoptimalcash flows could be revised,as in Figure2, on the basis

of these results.

Figure2

Cash Flows Within the BCG Matrix

Stars .Wildcats

'

avT 4

) I

Cows-" Dogs

BCG Prescription(Henderson,1979)

Revised, based on study - - - -

The results do not support BCG's advice that Dogs should be promptly

harvested or liquidated. This should come as a relief to many managers,

because more and more of their industries are maturing and because all

but the market leaders qualify as Dogs. What is needed is creative, positive

research and thinking about how Dogs can be managed for maximum long

term performance.

Another key, tentative conclusion to come from the study is that busi-

nesses may not always face sharp tradeoffs between share building and

cash flow or profitability. Only among Stars was there an inverse relation-

ship between market share change and any of the measures of returns.

Otherwise the relationships were nil, suggesting that multiple, seemingly

incompatible objectives can be pursued in tandem. More research is

needed on the circumstances that favor such "well-rounded" effectiveness

and on the internal features that can promote or stymie it.

The four types of businesses differ markedly in thgir strategic attributes.

Some attributes (e.g., R&D expenses, plant and equipment newness) vary

according to life cycle stage. Some (e.g., domain breadth, vertical integra-

tion, relative marketing expenditures) vary according to market share

position. Still others (e.g., capacity utilization, sales/employee) vary ac-

cording to both dimensions.

What emerges is an expanded understanding of the strategic profile of

each type of business:

Relative to the other cells, Wildcats tend to have low capacity utiliza-

tion, new plant and equipment, high current asset levels, high capital

intensity, high R&D expenses, high marketing expenses, narrow do-

mains, heavy new product activity, high direct costs, and competitive

devices that lag Star competitors on all fronts.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 529

Stars tend to have new plant and equipment,high capacityutilization,

high R&D expenses, broad domains, high sales per employee, high

value added, and superiorityon a numberof competitivedevices.

Cows tend to haveveryhigh capacityutilization,dated plantand equip-

ment, low capital intensity, low sales per employee, low R&D and

marketingexpenditures,broad domains, and superiorityon essen-

tially all competitivedevicesexamined.

Dogs tend to havedatedplantand equipment,mediumcapitalintensity,

high inventorylevels, low R&D expenses, moderate marketingex-

penses, narrowdomains, low value added, and competitivedevices

that lag Cow competitorson all fronts.

Overall,thereis a clearindicationthat businessesdiffer in their perfor-

manceand strategicattributes,accordingto theirlife cyclestagesand mar-

ket shares.The importanceattachedto these two key constructsby Hofer

(1975) and others appearsnot to have been ill-placed.

This paper sheds empiricallight on an important,but heretofore ill-

documentedstrategicframework,but it also raises many questions. For

example, would consumer products or service businessesyield findings

differentfrom the industrialbusinessesstudiedhere?Would a sampleof

non-PIMSbusinessesyield similarfindings?

The only contingencyvariablesincludedwerelife cycle stageand market

share. Many othershave been suggestedin the literature(Hofer, 1975). If

businessesweresubdividedfurtherwithinthe four BCG cells accordingto

additionalcontingentfactors(e.g., concentrationrates, frequencyof pur-

chase, or advertisingintensity), what new findings would emerge?The

presentstudy should serveas a springboardfor addingcontingentfactors

towardthe goal of full scale contingencymodels as advocatedby Hofer.

The cross-sectionalnatureof this studyposes an obviousproblem.How

businessesmove among the four cells of the matrixor how their strategic

attributestend to changeas they move from cell to cell has not been exam-

ined. This shortcominghighlightsa key opportunityfor future PIMS re-

search.The data base has been in existencelong enoughthat some longitu-

dinal analysesshould now be possible.

Empiricalanalysisof the BCG matrixhas long been overdue, as have

analysesof many other normativeand conceptualdevices in the field of

strategy.This paperhas corroboratedand extendedthe publishedideas of

the Boston ConsultingGroup. It servesas an importantbackdropto an

accompanyingstudy of the relationshipsbetweenstrategicattributesand

performancein each of the four cells (MacMillanet al., 1982).

References

Abell, D. Defining the business. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1980.

Anderson, C. R., & Paine, F. I. PIMS: A reexamination. Academy of Management Review, 1978, 3,

602-612.

Andrews, K. R. The concept of corporate strategy. Homewood, Ill.: Dow Jones-Irwin, 1971.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

530 Academy of Management Journal September

Bloom, P. E., & Kotler, P. Strategies for high market-share companies. Harvard Business Review,

1975, 53(6), 63-72.

Boston Consulting Group. Perspectives on experience. Boston: The Boston Consulting Group, 1968.

Bourgeois, L. J. Performance and consensus. Strategic Management Journal, 1980, 1, 227-248.

Buzzell, R. D., Gale, B. T., & Sultan, R. G. M. Market share: A key to profitability. Harvard Busi-

ness Review, 1975, 53(1), 97-106.

Chevalier, M. The strategy spectre behind your market share. European Business, 1972, 34, 63-72.

Christensen, K. H. Product, market, and company influences upon the profitability of business unit

research and development expenditures. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Columbia University,

1977.

Clifford, D. K., Jr. Managing the product life cycle. In R. Mann (Ed.), The arts of top management:

A McKinsey anthology. New York: McGraw Hill, 1971, 216-226.

Cyert, R., & March, J. A behavioral theory of the firm. New York: Prentice-Hall, 1963.

Ford, J. D., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. Size, technology, environment, and the structure of organizations.

Academy of Management Review, 1977, 2, 561-575.

Fox, H. W. A framework for functional coordination. Atlanta Economic Review, 1973, 23, 8-11.

Fruhan, W. E., Jr. Pyrrhic victories in fights for market share. Harvard Business Review, 1972, 50(5),

100-107.

Glueck, W. G. Business policy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976.

Hamermesh, R. G., Anderson, M. J., & Harris, J. E. Strategies for low market share businesses. Har-

vard Business Review, 1978, 56(3), 95-102.

Harrigan, K. R. Strategies for declining industries. Journal of Business Strategy, 1981, 2(2), 20-34.

Hatten, K. J., Schendel, D. E., & Cooper, A. C. A strategic model for the U.S. brewing industry:

1952-1971. Academy of Management Journal, 1978, 21, 592-610.

Hedley, B. Strategy and the "business portfolio." Long-Range Planning, 1977, 10, 9-15.

Henderson, B. D. Henderson on corporate strategy. Cambridge, Mass.: Abt Books, 1979.

Hofer, C. W. Toward a contingency theory of business strategy. Academy of Management Journal,

1975, 18, 784-810.

Hofer, C. W., & Schendel, D. Strategy formulation: Analytical concepts. St. Paul: West, 1978.

Katz, R. L. Cases and concepts in corporate strategy. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1970.

Kreiken, J. Effective vertical integration and disintegration strategies. In W. Glueck (Ed.), Business

policy and strategic management. New York: McGraw Hill, 1980, 256-263.

Lenz, R. T. Strategic interdependence and organizational performance: Patterns in one industry. Un-

published doctoral dissertation, Indiana University, 1978.

Levitt, T. Exploit the product life cycle. Harvard Business Review, 1965, 43(6), 81-94.

MacMillan, I. C., Hambrick, D. C., & Day, D. L. The association between strategic attributes and

profitability in the four cells of the BCG matrix-A PIMS-based analysis of industrial-product

businesses. Academy of Management Journal, 1982, forthcoming.

Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. Organizational strategy, structure, and process. New York: McGraw-

Hill, 1978.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. Telling more than we know: Verbal reports on a mental process. Psy-

chological Review, 1977, 84, 231-259.

Patel, P., & Younger, M. A frame of reference for strategy development. Long Range Planning,

1978, 11, 6-12.

Patton, A. Stretch your products' earning years. Management Review, 1959, 48(6), 9-14.

Robinson, S. J. Q., Hickens, R. E., & Wade, D. The directional policy matrix-Tool for strategic

planning. Long Range Planning, 1978, 10, 17-27.

Schoeffler, S. Cross-sectional study of strategy, structure, and performance: Aspects of the PIMS

program. In H. Thorelli (Ed.), Strategy and structure performance. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana

University Press, 1977, 108-121.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1982 Hambrick, MacMillan, and Day 531

Schoeffler, S., Buzzell, R. D., & Heany, D. F. Impact of strategic planning on profit performance.

Harvard Business Review, 1974, 52(2), 137-145.

Taylor, B. Managing the process of corporate development. Long-Range Planning, 1976, 9, 81-100.

Thompson, J. D. Organizations in action. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967.

Utterback, J., & Abernathy, W. A dynamic model of process and product innovation. OMEGA,

1975, 3, 639-656.

Vancil, R. F. Strategy formulation in complex organizations. Sloan Management Review, 1976, 17,

83-90.

Wasson, C. R. Product management. St. Charles, Ill.: Challenge Books, 1974.

Williamson, 0. Markets and hierarchies: Analysis and antitrust implications. New York: Free Press,

1975.

Woo, C. Y. Y., & Cooper, A. C. Strategies of effective low market share businesses. Academy of

Management Proceedings, 1980, 21-25.

Donald C. Hambrick is Associate Professor, Graduate School

of Business, Columbia University.

lan C. MacMillan is Associate Professor, Graduate School of

Business, Columbia University.

Diana L. Day is a doctoral student at the Graduate School of

Business, Columbia University.

This content downloaded from 169.229.32.137 on Thu, 8 May 2014 22:02:32 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and CompetitorsFrom EverandCompetitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and CompetitorsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (31)

- A Model For Diversification - Ansoff - 1958Document24 pagesA Model For Diversification - Ansoff - 1958SebastianCaballeroNo ratings yet

- Application - Regular Income Tax On Individuals and CorporationsDocument8 pagesApplication - Regular Income Tax On Individuals and CorporationsElla Marie Lopez0% (1)

- Competitive Strategy by Michael E. PorterDocument4 pagesCompetitive Strategy by Michael E. Portercallmeshani1No ratings yet

- 1982 Strategic Attributes and Performance in The BCG Matrix. A PIMS-Based AnalysisDocument23 pages1982 Strategic Attributes and Performance in The BCG Matrix. A PIMS-Based Analysiscarla_chagas690No ratings yet

- Greenwood 1990Document32 pagesGreenwood 1990FandiNo ratings yet

- The Contribution of Industrial Organization To Strategy ManagementDocument13 pagesThe Contribution of Industrial Organization To Strategy ManagementPangeran Henrajostanhidajat SastrawidjajaNo ratings yet

- Resumen RumeltDocument5 pagesResumen RumeltselerovsNo ratings yet

- (2004) (Mansfield & Fourie) Strategy and Business Models - Strange BedfellowsDocument10 pages(2004) (Mansfield & Fourie) Strategy and Business Models - Strange BedfellowsEverson PintoNo ratings yet

- Marketing's Contribution To The Implementation of Business StrategiesDocument15 pagesMarketing's Contribution To The Implementation of Business StrategiesavomoNo ratings yet

- Lane-Aom-03 BCG 12Document14 pagesLane-Aom-03 BCG 12Pratiksha SunagarNo ratings yet

- Wheelwright Steven Manufacturing Strategy 1984 MarDocument16 pagesWheelwright Steven Manufacturing Strategy 1984 MarHermanoCarlos ServandoNo ratings yet

- Musaib Sample PaperDocument19 pagesMusaib Sample PaperAsad Ali AliNo ratings yet

- 波特5力pdfDocument15 pages波特5力pdfrdtrinyNo ratings yet

- Wiley Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Strategic Management JournalDocument26 pagesWiley Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Strategic Management JournalTomy FitrioNo ratings yet

- 1997 - Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management - TEECE - Parei-Pag9Document26 pages1997 - Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management - TEECE - Parei-Pag9Kamila BortolettoNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Journal - 1998 - Teece - Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic ManagementDocument25 pagesStrategic Management Journal - 1998 - Teece - Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic ManagementKarla STRADENo ratings yet

- Armour and TeeceDocument18 pagesArmour and Teecea20236878No ratings yet

- Unit 6 Product Portfolio: ObjectivesDocument19 pagesUnit 6 Product Portfolio: ObjectivesAdil Bin KhalidNo ratings yet

- WilliamsDocument28 pagesWilliamsTony DumfehNo ratings yet

- Introduction 130407092142 Phpapp01Document69 pagesIntroduction 130407092142 Phpapp01Pari Savla100% (1)

- 多样化与绩效联系的曲线:对三十多年研究的审查Document20 pages多样化与绩效联系的曲线:对三十多年研究的审查miaomiao yuanNo ratings yet

- Revista Base (Administração e Contabilidade) Da Unisinos 1984-8196Document4 pagesRevista Base (Administração e Contabilidade) Da Unisinos 1984-8196abid hussainNo ratings yet

- Strategic Analysis On FMCG Goods: A Case Study On Nestle: Gedela Rakesh Varma Prof. Jaladi RaviDocument11 pagesStrategic Analysis On FMCG Goods: A Case Study On Nestle: Gedela Rakesh Varma Prof. Jaladi RaviPrayag DasNo ratings yet

- Strategic Assets and Organizational RentDocument14 pagesStrategic Assets and Organizational RentEduardo SantocchiNo ratings yet

- 111.00000002 Feldman V1N1 SMR 0002Document29 pages111.00000002 Feldman V1N1 SMR 0002Adit PNo ratings yet

- The Historical Development of The Market Segmentation ConceptDocument41 pagesThe Historical Development of The Market Segmentation ConceptDEBASWINI DEYNo ratings yet

- Dess e Davis (1984)Document23 pagesDess e Davis (1984)Guilherme MarksNo ratings yet

- Porter Generic StrategiesDocument23 pagesPorter Generic StrategiesSobia MurtazaNo ratings yet

- Portfolio AnalysisDocument20 pagesPortfolio AnalysisevaNo ratings yet

- Generic Strategies February 2009Document29 pagesGeneric Strategies February 2009Rahul DusejaNo ratings yet

- j.1540-5885.2012.00920 2.xDocument5 pagesj.1540-5885.2012.00920 2.xZuzana VojtekováNo ratings yet

- Marketing Theory With Strategic Orientation PDFDocument12 pagesMarketing Theory With Strategic Orientation PDFNarmin Abida0% (1)

- Evaluating Market Attractiveness: Individual Incentives vs. Industrial ProfitabilityDocument38 pagesEvaluating Market Attractiveness: Individual Incentives vs. Industrial ProfitabilityrerereNo ratings yet

- Supermarket Customers Segments Stability PDFDocument13 pagesSupermarket Customers Segments Stability PDFSyed Farjad AliNo ratings yet

- Covin 90 ClusterDocument27 pagesCovin 90 ClusterChiraz RosaNo ratings yet

- A Contingency Approach To StrategyDocument27 pagesA Contingency Approach To Strategyrangu007No ratings yet

- Corporate-Level Strategy, Business-Level Strategy, and Firm PerformanceDocument27 pagesCorporate-Level Strategy, Business-Level Strategy, and Firm PerformancedffdsfsfdsdNo ratings yet

- Academy of Management The Academy of Management JournalDocument23 pagesAcademy of Management The Academy of Management JournalMauvais TempsNo ratings yet

- Barney - Types of Competition and The Theory of Strategy...Document11 pagesBarney - Types of Competition and The Theory of Strategy...JimakozNo ratings yet

- Strategy and Performance - Asp PDFDocument5 pagesStrategy and Performance - Asp PDFJay Aubrey PinedaNo ratings yet

- A Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in The Diversified Major FirmDocument23 pagesA Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in The Diversified Major Firmshahmed999No ratings yet

- Strategic Management Journal - 1998 - Teece - Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic ManagementDocument25 pagesStrategic Management Journal - 1998 - Teece - Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic ManagementCamila LimaNo ratings yet

- Voss - 1995 - Alternative Paradigm For Manufacturing Strategy PDFDocument13 pagesVoss - 1995 - Alternative Paradigm For Manufacturing Strategy PDFMR7791No ratings yet

- The Strategic Management of Sudden Changes in The Competitive Environment The Case of The French Dairy IndustryDocument24 pagesThe Strategic Management of Sudden Changes in The Competitive Environment The Case of The French Dairy IndustryRamNo ratings yet

- On The Structural Dimension of Competitive StrategyDocument17 pagesOn The Structural Dimension of Competitive StrategyAus FirdausNo ratings yet

- Miles and Snow Ajbr180042Document25 pagesMiles and Snow Ajbr180042Biju MathewsNo ratings yet

- Lim and AcitoDocument27 pagesLim and AcitoMarit Owe TryggesetNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Journal - 1998 - Teece - Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic ManagementDocument25 pagesStrategic Management Journal - 1998 - Teece - Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic ManagementQie LuckyNo ratings yet

- SWOT AnalysisDocument9 pagesSWOT Analysispizzah001pNo ratings yet

- Porter-TowardsDynamicTheory-1991 (1) Ilovepdf (1) - 1Document6 pagesPorter-TowardsDynamicTheory-1991 (1) Ilovepdf (1) - 1Sifou SsiffouNo ratings yet

- A Strategic Process Guide: Article Relevant To Professional 1 Management & Strategy Author: Fergus McdermottDocument4 pagesA Strategic Process Guide: Article Relevant To Professional 1 Management & Strategy Author: Fergus McdermottGodfrey MakurumureNo ratings yet

- Revisiting Business Strategy Under Discontinuity: Management Decision September 2013Document34 pagesRevisiting Business Strategy Under Discontinuity: Management Decision September 2013Tekaya CyrineNo ratings yet

- Setting Manufacturing Strategy For A Factory-Within-A-FactoryDocument17 pagesSetting Manufacturing Strategy For A Factory-Within-A-FactoryTania Amórtegui ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Wheel of StrategyDocument7 pagesWheel of StrategyKalpesh Singh SinghNo ratings yet

- Strategic ManagementDocument59 pagesStrategic ManagementSharifMahmudNo ratings yet

- Regional Formation 27133-141Document10 pagesRegional Formation 27133-141Victor DiasNo ratings yet

- Alternative Paradigms For Manufacturing Strategy: C.A. VossDocument12 pagesAlternative Paradigms For Manufacturing Strategy: C.A. VosshwzoeNo ratings yet

- Herrigel. Autoparts-OEMcompetition PDFDocument35 pagesHerrigel. Autoparts-OEMcompetition PDFmateoNo ratings yet

- 6 Robic FinalDocument24 pages6 Robic FinalPratama Surya AdhityaNo ratings yet

- A Taxonomy of Manufacturing StrategiesDocument21 pagesA Taxonomy of Manufacturing StrategiesMarcos De Campos MaiaNo ratings yet

- Square FoodDocument39 pagesSquare FoodnazninNo ratings yet

- Jfra Idjfra 2018Document31 pagesJfra Idjfra 2018nazninNo ratings yet

- TAMANNA - List of Draft Internal Factors of UnileverDocument3 pagesTAMANNA - List of Draft Internal Factors of UnilevernazninNo ratings yet

- SM Industry Analysis Assignment 1Document11 pagesSM Industry Analysis Assignment 1nazninNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 14 13016 v2Document24 pagesSustainability 14 13016 v2nazninNo ratings yet

- Square Pharma AR 21 CompressedDocument157 pagesSquare Pharma AR 21 CompressednazninNo ratings yet

- Aci Annual Report 2020 2021Document333 pagesAci Annual Report 2020 2021nazninNo ratings yet

- Accounting Ratio Formula Excel TemplateDocument4 pagesAccounting Ratio Formula Excel TemplatenazninNo ratings yet

- Alfa Laval Repair For Aalborg BoilersDocument2 pagesAlfa Laval Repair For Aalborg Boilersmichall123No ratings yet

- Assignment On Permanent Settlement ActDocument3 pagesAssignment On Permanent Settlement ActAhnaf AliNo ratings yet

- Absapl-R150-27 06 2023Document1 pageAbsapl-R150-27 06 2023janinepretorius11No ratings yet

- "Export Procedure and Documentation": Bba 5 Semester By: Dr. Madhvi KushDocument28 pages"Export Procedure and Documentation": Bba 5 Semester By: Dr. Madhvi Kushekta singhNo ratings yet

- Business Administration 1: Operation ManagementDocument14 pagesBusiness Administration 1: Operation ManagementKerry CheeNo ratings yet

- Master in Business Administration (Mba) (Supply Chain and Logistics) 2021/2022Document6 pagesMaster in Business Administration (Mba) (Supply Chain and Logistics) 2021/2022AvinaNo ratings yet

- Appraisal and Assessment in The Government Sector Prelim Q1Document3 pagesAppraisal and Assessment in The Government Sector Prelim Q1Michelle EsperalNo ratings yet

- Veronika Donatta Maria - Makeup Exam - International Political EconomyDocument5 pagesVeronika Donatta Maria - Makeup Exam - International Political EconomyVeronika DonattaNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 BL Sample (Lbba)Document20 pagesUnit 7 BL Sample (Lbba)Rafiqul HoqueNo ratings yet

- ) in The Side of The Following Choices, Write It in The Space ProvidedDocument2 pages) in The Side of The Following Choices, Write It in The Space ProvidedBryan Cstr TumazarNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management-Collaborative and Network-Based Forms of StrategyDocument19 pagesStrategic Management-Collaborative and Network-Based Forms of StrategyNoemi G.No ratings yet

- Statement of Account For Month Ending: 11/2021 PAO: 56 SUS NO.: 0937012 TASK: 101Document4 pagesStatement of Account For Month Ending: 11/2021 PAO: 56 SUS NO.: 0937012 TASK: 101Dragon GamersNo ratings yet

- Magzine Forbes PDFDocument126 pagesMagzine Forbes PDFYOGENDER KUMAR100% (2)

- Tugas 1 AklDocument3 pagesTugas 1 Akledit andraeNo ratings yet

- Annual Report of IOCL 185Document1 pageAnnual Report of IOCL 185Nikunj ParmarNo ratings yet

- c311316a-f4ce-4ddf-b262-c91d2b9f1c32Document13 pagesc311316a-f4ce-4ddf-b262-c91d2b9f1c32Ciro Antonio Zuñagua LLanosNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Regional Carbon Allocation and Carbon Trading Based On Net Primary Productivity in China PDFDocument16 pagesAnalysis of Regional Carbon Allocation and Carbon Trading Based On Net Primary Productivity in China PDFDiogo AlvesNo ratings yet

- London School of Economics and Political Science: MSC in China in Comparative Perspective 2017/2018Document34 pagesLondon School of Economics and Political Science: MSC in China in Comparative Perspective 2017/2018PojPhetlorlianNo ratings yet

- Financial Management Essentials You Always Wanted To Know: 4th EditionDocument22 pagesFinancial Management Essentials You Always Wanted To Know: 4th EditionVibrant Publishers100% (2)

- Agreement - Diva Healthcare - 20march 2023Document2 pagesAgreement - Diva Healthcare - 20march 2023Hadrs ParmarNo ratings yet

- Jurusan Akuntansi Fakultas Ekonomika Dan Bisnis Universitas Diponegoro Jl. Prof. Soedharto SH Tembalang, Semarang 50239, Phone: +622476486851Document13 pagesJurusan Akuntansi Fakultas Ekonomika Dan Bisnis Universitas Diponegoro Jl. Prof. Soedharto SH Tembalang, Semarang 50239, Phone: +622476486851Anthon AqNo ratings yet

- LZ2316AJDocument1 pageLZ2316AJDavid ArgañarazNo ratings yet

- Yamazumi Chart 1.0Document1 pageYamazumi Chart 1.0Chelovek ParahodNo ratings yet

- 2002 Economics Paper 2 (Original)Document20 pages2002 Economics Paper 2 (Original)peter wongNo ratings yet

- FINA3070 Lecture Notes v6Document215 pagesFINA3070 Lecture Notes v6aduiduiduio.oNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 RPGTDocument24 pagesChapter 10 RPGTdiyana farhanaNo ratings yet

- CA Rest and Meal Break Training 2022Document12 pagesCA Rest and Meal Break Training 2022Nichole FishNo ratings yet

- What Are Notes ReceivableDocument2 pagesWhat Are Notes ReceivableDarlene SarcinoNo ratings yet