Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Negotiation of Meaning in CHILDRENS FOREIGN LANG ACQUIS

The Negotiation of Meaning in CHILDRENS FOREIGN LANG ACQUIS

Uploaded by

lizete.capelas8130Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Negotiation of Meaning in CHILDRENS FOREIGN LANG ACQUIS

The Negotiation of Meaning in CHILDRENS FOREIGN LANG ACQUIS

Uploaded by

lizete.capelas8130Copyright:

Available Formats

The negotiation of meaning in

children's foreign language

acquisition

Richard Young

This article is a result of work which has been done over a number of

years by the British Council in Hong Kong in curriculum development

for English as a foreign language in Hong Kong's primary schools. The

problem under consideration is how recent theoretical insights into the

acquisition of first and second languages by young children can be

drawn on in a workable methodology for teaching young learners a

foreign language in schools, and how syllabuses and teaching materials

can be designed to maximize the benefit of activity-based teaching

methods.

The article is in four parts: the first two parts outline two comple-

mentary theoretical approaches to children's foreign language

acquisition; in the third part, I consider three different teaching methods

in the light of theoretical insights; and lastly, I consider some issues in

syllabus and materials design which are particularly relevant to the

organization of the learning of foreign languages by young children in

schools.

The Monitor Theory Since 1975, Stephen Krashen and his associates have put forward a very

illuminating explanation for adult second language behaviour, which has

become known as the 'Monitor Theory'. This theory in its latest formula-

tion goes something like this (Krashen 1981): adults have two independent

ways of developing ability in second languages, subconscious language

acquisition and conscious language learning. And although these two systems

are interrelated in a definite way, subconscious acquisition appears to be

far more important than conscious language learning. The distinction

made by Krashen between the two terms acquisition and learning is not new.

It originated from the need to distinguish between the natural, informal

way in which children acquire their mother tongue, and the conscious,

formal way in which adults learn a foreign language.

The condition which is necessary in order to acquire a language, says

Krashen, is meaningful interaction in the target language, in which the

speakers are concerned not with theyorm of what they say, but rather with

the message that is being conveyed. As a result, the correction of errors and

the explicit teaching of rules are not relevant to language acquisition,

although parents and native speakers may modify what they say in speak-

ing to children or foreign acquirers, in order to help them to understand.

On the other hand, conscious language learning takes place when the

focus is placed on the form of the message, rather than the content. And

learning in this sense is greatly helped by judicious correction of errors and

the explicit formulation of rules.

Now, the fundamental claim of the Monitor Theory is that conscious

learning is available to the performer only as a Monitor. In general, utter-

ELTJournal Volume3773July 1983 197

ances are initiated through the acquired system, which is to say that our

productive ability in a foreign language is based on what we have 'picked

up' through active communication. The only function of what we have

consciously learned is to alter the output of the acquired system, some-

times before and sometimes after the utterance has been produced. The

conscious 'monitor' makes these changes in order to improve accuracy.

Krashen claims (Krashen 1977) that use of the monitor explains such

phenomena as discrepancies in oral and written second language per-

formance, and differences between careful classroom speech and students'

casual conversation. He also claims that it accounts for the observation that

certain students display a firm grasp of the structure of the target language

yet seem unable to function in the language, while others do poorly on

structure tests, but appear to be able to communicate quite well. He

develops the Monitor Theory in more detail, but we need go no further for

our purposes.

Krashen's hypodiesis relates specifically to adult second language

learning. The corollary for children learning second languages is that die

acquisition mode is far more important than the learning mode, the differ-

ence being even greater than for adults. From my experience, it is not true

to say that children do not monitor their own performances in a second

language, but it seems drat their degree of monitoring is far less than it

might be for adults. Krashen makes allowances for individual differences in

die use of the monitor, and on his scale of monitor users, I believe we

would probably find most children down at die 'Underuser' end of the

scale.1

What are die implications of diis in terms of teaching mediods? Most

important of all is surely that die major function of the second language

classroom is to provide intake for acquisition (Krashen 1981:101), and,

secondly, diat ways of teaching which concentrate on the form of language

do not provide the best intake for acquisition. One may infer, for example,

diat pattern practice drilling with a group of young children (chronic

'underusers' of die monitor) is likely to be more or less irrelevant to Uieir

acquisition and use of English as a foreign language, since it concentrates

on linguistic form, radier than on meaningful communication.

Negotiation Krashen's perspective on second language learning is a psychological one.

Let us now turn to die sociolinguistic perspective in die work of die British

educationist and linguist Gordon Wells at die University of Bristol.

Wells has been conducting a longitudinal study of die modier tongue

language development of a representative sample of young English

children, based on regular observations of die children's spontaneous

linguistic interaction at home and at school (Wells 1979). Wells' data are

collected by means of a radio microphone worn by die child. This

transmits the child's talk to a tape recorder diat is programmed to record

twenty-four ninety-second samples at approximately twenty-minute

intervals diroughout die day between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. In die evening the

tape is played back to die modier, who provides as much information as

possible about what was going on while the recordings were being made.

The diing which I find most interesting in Wells' work is one of his pre-

liminary findings: the more opportunities die child has to experience

linguistic interacdon widi his or her parents before entering school, die

higher is die child's level of linguistic development when he or she enters

school; and diat diis is closely related to reading ability, even after two

198 Richard Young

years in school. To show the different types of interaction that he is talking

about, Wells quotes two young children interacting with their mothers. The

first child engages her mother in conversation, and each initiation on the

child's part is accepted and developed by the mother, so that a regular

process of negotiation of meaning occurs throughout. The second child's

mother, on the other hand, does not respond to her daughter's initia-

tions: there is none of the co-operative behaviour which characterized the

conversation of the first pair. When the second child's interests and inten-

tions conflict with her own, the mother makes no attempt to negotiate a

mutually agreed resolution. Wells claims that the first type of co-operative

interaction is a major aid to a child's linguistic development. It is negotia-

tion that Wells sees as crucial, the way in which, through interaction,

mutually agreed meanings and behaviour are arrived at.

How is this relevant to teaching English as a foreign language to children

at school ? If meaningful communicative interactions in which the par-

ticipants negotiate common ground by a process of give-and-take are so

important for first language development, then surely they must also have

an important role to play in the way children acquire a second language. I

am supported in this belief by Joseph Huang and Evelyn Hatch's remark-

able study (Huang and Hatch 1978) of the acquisition of English syntax by

a five-year-old Taiwanese-speaking child, who acquired English as a

second language naturally through interaction with his peer-group and the

teachers (who did not set out to teach him English) in a play-group in Los

Angeles. The child, Paul, in nineteen weeks proceeded from knowing his

native Taiwanese quite well, but knowing hardly any English, to a state

where 'it appeared that his language was indistinguishable from that of the

American children with whom he played' (Huang and Hatch 1978:131). In

other words, Paul learned a second language in nineteen weeks without

formal language training. One wonders how much longer it would have

taken him if he had gone to English classes! In teaching English to children

at school, as teachers plough relentlessly from one language item to

another, they may well be making progress from the point of view of the

syllabus, but they may be making very little progress in assisting the

acquisition of the second language by the pupils. Progress in language

development, as Wells suggests for children in their mother tongue and as I

would suggest for children learning a foreign language, can only be made

by allowing the children to experience a wide range of interactions in which

meaning and behaviour can be negotiated. If we do not figure out some

way for this to happen in the primary school classroom, then any

impression we have that pupils are making progress will be largely illusory.

Negotiation in Here, then, I believe, are two extremely valuable theoretical insights into

the classroom how young children learn a second language. Firstly, children do not use

their learned store anything like so much as adults are able to: children rely

to a very great extent on the language they have acquired while they have

been concentrating on meaning rather than form. It must then be our job

as teachers to provide our young pupils with inputs to their language

acquisition system, rather than inputs to their formal learning system.

Secondly, meaningful interaction implies more than just linguistic inter-

action, and it is indispensable to create the conditions for interactions in

which meaning can be negotiated if children are to make progress in

acquiring a second language.

These are the two insights. How, then, can we create the optimum con-

The negotiation ojmeaning 199

ditions in the primary school classroom for second language acquisition?

As far as I can see, there are at least three techniques which go some way

towards it.

Meaningful practice The first technique is meaningful language practice. The transcript below is

taken from a film that was made in Hong Kong in 1976 called The Four

Stage Approach. It shows four stages from presentation to production of the

first, second, and third person singular of the present perfect tense. The

extract is taken from the last part of the film, during the final stage of the

lesson.

(A Chinese teacher of English faces a class of 40 8- and 9-year-old children.

The children are sitting in rows facing the teacher.)

Teacher: Now let's begin. Whoever makes the correct guess will win an apple

for their team. Group A, who would like to come out? Tarn Lai-keung.

(Tarn walks towards the teacher.)

Teacher: Class, put down your heads.

(The class put their heads on their desks. They cannot see what is happen-

ing as Tarn Lai-keung closes the box on the teacher's table.)

Teacher: All right. Everybody look up. Group A.

(She conducts Group A in chorus.)

Group A: What has she done?

Teacher: Chan Man-fai,

Chan Man-fai: Has she touched the blackboard?

(Teacher conducts Group B in chorus.)

Group B: Have you touched the blackboard ?

Tarn Lai-keung: N o , I haven't.

(Teacher conducts Group A in chorus.)

Group A: No, she hasn't. She hasn't touched the blackboard. What has she

done?

Leung Tak-man: Has she closed the box?

(Teacher conducts Group B in chorus.)

Group B: Have you closed the box?

Tom Lai-keung: Yes, I have.

(Teacher conducts Group A in chorus.)

Group A: Yes, she has. She has closed the box.

Teacher: Very good, Group A. One apple for you.

(Teacher draws an apple on Group A's tree.)

Teacher (to Tarn Lai-kuen): Go back to your seat.

What can we say about this activity? How does it measure up to the

requirements of a meaningful communication activity in which meaning is

negotiated as a result of co-operative interaction?

The first thing we can say is that there is very little negotiation going on.

The children are free to make their own guesses about what the child at the

front has done, and if their guess is incorrect they have to make another

one, but the teacher is controlling the interaction so tightly that it is she

who leads the children through the various steps of the negotiation. It is not

die children who are negotiating the outcome of the situation, but die

teacher. Moreover, although the teacher tries to motivate the class to par-

ticipate by transforming the activity into a competitive game in which each

team tries to win apples to put on their tree, it seems to me that die main

motivating force in die whole interaction is a desire to follow the teacher's

instructions, i.e. her gestures as she conducts the class through the different

200 Richard Young

stages of the interaction.

One other thing is that this type of interaction, in which large groups are

speaking in unison, is not very appropriate to a meaningful negotiating

activity, since the individual responses of the participants to the situation

are suppressed because of the need to present a united front. To sum up,

then, here we have the illusion of negotiation: the students are all speak-

ing, using the pattern that the teacher has presented, in a meaningful

activity, but the nature of the interaction is such that it does not create the

conditions in which language can be acquired. An illusion of relevance is

created, and if the children enjoyed the activity (which a good teacher

would ensure), we also have the illusion of success. However, it becomes

dear that diese are illusions if we measure the activity against our criteria of

genuine negotiation which provides input to the learners' language

acquisition system.

Communication games Let us now look at an example of a communication activity. Once again,

the example is taken from film made of a lesson in a Hong Kong primary

school.

The children in this class, aged nine and ten, are seated in small groups

of four or five around die room. The teacher has introduced the func-

tions: requesting simple objects and complying with or refusing the

requests. She has devised a card game to enable die children to perform

these functions in a realistic context. Each child in the group has four

cards: on two of the cards die name of an object is written; on die other

diere are pictures of objects, but no words. The aim of die game is for each

player to win pairs of cards—a word-card and die corresponding picture-

card—by requesting pictures from die odier players. Each player can ask

any odier player for die picture he or she needs to make a pair. When a pair

is formed, die two cards are placed side-by-side face down on die table. If

die odier player is unable to comply widi die request, die turn passes to

anodier child, and so on round die table. The game finishes when one

player has made all his or her pairs and has laid diem down on die table:

diis player is die winner. Aldiough die rules sound complicated, diey are

well known to die children playing die game, since diey are very similar to a

card game which is popular in Hong Kong. Four children are seated

around a table.

May: Will you give me a bag, please?

John: (hands bag picture to May) Here you are.

May: Thank you. (She lays her trick down on die table.)

John: Will you give me a watch, please ?

Bonnie: Sorry, I haven't got one. Will you give me a shoe, please?

Sandra .-'Sorry, I haven't got one. Will you give me a watch, please?

. . May: Sorry, I haven't got one. Will you give me a watch, please ?

John: (hands watch picture to May) Here you are.

May: Thank you.

John: (to Sandra) Will you give me a radio, please? (pause) Will you give me

a radio, please ?

Sandra: (hands radio picture to John) Here you are.

John: Thank you. (He lays his trick down on the table.)

Bonnie: Will you give me a car, please ?

Sandra: Sorry, I haven't got one. (pause) Will you give me a camera, please?

May: Sorry, I haven't got one. Will you give me a shoe, please?

Sandra: (hands shoe picture to May) Here you are.

The negotiation of meaning 201

May: Thank you. (She lays her third trick on the table and shows her empty

hands to the other players to show she is the winner.)

How does this measure up to our criteria? Although the children are

using only very simple language, they are involved in an activity which

allows each individual to negotiate his or her way through the interaction

in the way which suits the child best according to the rules of the game. The

focus of the children's attention is more on the game itself than on the

language required to play it. Thus, this kind of activity does provide input

to the children's language acquisition system, and not just to their

language learning system.

Children's games The last type of activity that I would like to discuss is children's games, the

sorts of games which children diemselves play in the playground and

outside school, which in their design have nothing whatsoever to do with

learning English. I think it is worth considering this sort of activity, because

children's games are, if you like, deliberately negotiable and com-

municative, and the focus of the activity is some non-linguistic outcome.

Three types of game seem to be promising. These are making models, music

and drama games, and what, for want of a better word, I call games for a rainy

day (cf. Huang et al. 1979). Under making models I include things like sailing

model boats, making plasticine or rice-flour figures, making dolls' houses,

matchstick furniture, melon seed animals, dolls' clothes, corn dollies, tree-

houses and paper hats, boats and buildings. Music and drama games include

puppet shows, dances, making masks, decorating your body, and many

more. Games for a rainy day are board games like snakes and ladders, pencil-

and-paper games (like noughts and crosses), collecting things, watching

television, and keeping pets.

In these sorts of games and activities, language may be a central part of

the interaction, and we can therefore perhaps adapt them to our purposes

for language learning. For example, in learning from someone else how to

build a model, quite a lot of language is used and it is put to some useful

non-linguistic purpose in the interaction.

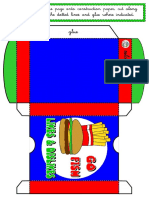

My last example of actual interaction activities is an adaptation of a

children's game for use in the classroom. The example here is the piece of

teaching material shown in Fig. 1, rather than a transcript of an actual

lesson. In this game a number of children stand around in a circle holding

on to a continuous piece of string threaded through a ring. By moving

dieir hands from side to side, they can pass die ring secretly from one

player to the next. One child stands in the middle of the circle and has to

try and guess which of the players is holding the ring. The player in the

middle points to whoever she thinks has got the ring and says, for example,

'Leung Wai-ming's got the ring'. Leung Wai-ming then has to open his

hands. If he has not got the ring, the rest of the players chorus, 'No, he

hasn't', and so on, until the player in die middle has found the ring. The

person who is caught holding the ring then changes places with the child in

die middle of the circle and the game can start again.

I diink it is clear that here, too, is an activity which fits quite well into the

mould diat we require. We have a game, the main purpose of which is to

find the ring, but in order to achieve that, the situation has to be nego-

tiated by means of language. The language used is simple in the extreme

(just die diird person singular of have got) and is well within the com-

petence of children in Hong Kong towards die end of dieir first year in

primary school.

202 Richard Young

Figure 1.

Let's play Ringaround. j

Joe's got the ring. \s

Y\p Siu-lan's got the ring.

No, she hasn't*

No, she hasn't got the ring.

I've got thering!J

Here then we have three examples of activities in the primary school

English classroom: rather rigid teacher-centred language practice, a com-

munication game, and an adapted children's game. I believe that only the

last two are of any use in allowing children to acquire English through a

natural process of negotiating meanings in interaction. The language

practice activity merely creates an illusion that the children are learning,

whereas in fact very little useful learning is taking place.

Negotiation and If communication activities and children's games are so useful in teaching

syllabus design English to young children, how dien is it possible for us to organize our

syllabus and materials to make the most of these kinds of activity? Before

answering this question, I would like to follow Wilkins (1976) in drawing a

distinction between synthetic and analytic language teaching syllabuses. The

distinction has to do with how the target language is presented to the

learner. If the language is chopped up into litde bits and the bits are dien

The negotiation of meaning 203

fed one by one to die learners, the teaching materials are said to be

organized according to a 'synthetic' syllabus. If, on die other hand, diere is

no attempt at diis careful linguistic control of the learning environment,

but language is presented in a form which is limited in scope simply by the

amount of time available to teach it, and if the presentation of different

units is sequenced on purely non-linguistic grounds, we have materials

which are organized according to an 'analytic' syllabus.

The great majority of teaching materials available for beginners reflect

an underlying syndietic syllabus, rather than an analytic one. Most of die

previous generation of beginners' courses had grammatical structure as

dieir organizing principle. In diese materials, each unit is defined in terms

of die grammatical patterns to be covered, and die order of presentation of

new material is regulated by considerations of grammatical complexity. A

new generation of materials is now available whose organizing principle is

no longer grammatical patterns, but radier communicative function:

instead of having a unit on, say, die present continuous tense, you will have

one whose aim is to teach, say, requests. The units in a functional course

are not subject to die rigid ordering implied by a grammatical syllabus, but

nevertheless considerations of linguistic simplicity may apply. A diird

category of materials for beginners aims to effect a compromise between

functional and structural organization, and to exploit the fact diat, at die

very lowest level of linguistic and communicauve competence, one function

tends to be realized uniquely in terms of one structure (for example, for

beginners die function of asking permission is most conveniendy covered

by one grammatical pattern, 'Can I . . ., please?'). Here, the question of

whedier the function or die structure is die principal objective is largely

irrelevant, since die grammatical structure is taught in order to perform die

communicative function and die communicative function is uniquely

realized by that grammatical structure.

In diese diree types of syllabuses for beginners—structural, functional,

and functional-structural—discrete linguisdc or behavioural items are die

basis of die syllabus organization. They are therefore, in Wilkins' terms, all

syndietic syllabuses. Recently, synthetic syllabuses have come to be criti-

cized independently by applied linguists working in Lancaster (Breen,

Candlin, and Waters 1979) and in Hong Kong (Tongue and Gibbons 1982),

and a genuine alternative to diem has been put forward in Soudi India by

N. S. Prabhu and D. Carrol.

Breen, Candlin, and Waters make die point diat, whereas structural

materials are easy to organize, communicauve materials are not. In dieir

words, given die present state of dieory and research into language as com-

munication, it seems diat such data are not amenable to die kind of systematic

organization or categorization which have been applied when presendng

language as form.

These writers suggest diat 'teachers and designers need be far less con-

cerned with die prior selection and organization of the data and much

more concerned widi the ways learners may act upon and interact with such data!

(Breen et at. 1979). The main point is that communicauve materials will be

more concerned with the teaching-learning process dian widi die content

of teaching and learning. These audiors also make a distinction between

what diey call 'content materials' on die one hand, and 'process materials'

on die other. By 'content materials' diey mean either audientic spoken or

written language, or else reference materials such as dictionaries and

grammar books. 'Process materials', on die odier hand, are units or frame-

204 Richard Young

works of activity. Each unit or framework would outline an activity and a

range of appropriate tasks within the activity, and each task would be

designed to activate the learner's process competence through com-

municative acts.

Tongue and Gibbons deal specifically with syllabus design for young

beginners and maintain that a synthetic syllabus specified in either struc-

tural or linguistic terms is unnecessary and undesirable for young children.

They give a few examples of 'activities' which could be items in an analytic

English syllabus for beginners. They mention, for example, activities like

'solving simple problems and puzzles', 'responding to signs and symbols',

and 'making surveys of pupils' habits and tastes'.

The most thoroughgoing support for an analytic syllabus based on

activities is given by N. S. Prabhu and David Carrol in their interesting

work in the Regional Institute of English in Bangalore, South India. N. S.

Prabhu has designed what he calls a 'procedural syllabus' (Prabhu and

Carrol 1980). The basic idea is that the pupils should learn English through

the performance of certain tasks and activities, rather than by focusing on

the language itself. However, the pupils in the classes in the Bangalore

Project are not absolute beginners; they are secondary schoolchildren who

have already had a number of years of learning English in primary schools.

They have learned English before, according to a structural syllabus, so it

could be said that they have learned (in Krashen's sense) rather than

acquired the major grammatical patterns of English, as well as some

vocabulary. The Bangalore Project, therefore, is to some extent concerned

with the activation of this learned grammar.

Conclusions The problem that remains is, I think, this: with zero beginners, with young

children in primary schools, is it possible in English lessons to organize

communicative activities which focus on meaning rather than on linguistic

form? The answer to this question, I think, can be found if we make a clear

distinction between syllabus and methodology. Those who advocate

abandoning entirely a structural or funaional syllabus and replacing it by

one based on activities are, I feel, over-reacting to one particular defect in

audio-lingual methodology, and in so doing are throwing the baby out

with the bathwater. Grammarians over the years, and sociolinguists for the

last twenty years, have given us extremely valuable insights into the way in

which language functions as a formal system, and the way in which

language is used for communication. Surely, if we organize our language

teaching programme for beginners in terms of these insights, we can only

gain in terms of coverage of all the necessary grammatical patterns and

communicative functions, in terms of how deeply we go into a particular

area of grammar or of communication, and in terms of the necessary

recycling of elements in order that they are retained.

It is not crucial whether we mention grammatical or functional items in

our syllabus. The crucial question is how we arrange them and then, in our

teaching materials, how we create the circumstances whereby those gram-

matical or funaional items are contextualized in activities which are

genuinely communicative in the sense that they permit individual children

to negotiate meaning in order to perform the activity. What we need is a

multi-dimensional syllabus in which linguistic and communicative

elements are clustered together around a particular classroom or out-of-

class attivity. If our students are young children unable to use their

'monitors' much, then the successful completion of the activity will become

The negotiation of meaning 205

the objective of that particular teaching unit. If, on the other hand, we are

dealing with older children or adults who may benefit from input into their

learning system (in Krashen's sense), then let us by all means also do exer-

cises which practise the linguistic forms and communicative functions

which we have used in the activity.

There are, therefore, two extreme positions to be avoided. According to

the first, linguistic structure is the sole aim and arbiter of everything which

goes on in the classroom. In the second, all insights from linguistics and

communicative theory are purposely ignored, and activities are designed

with no concern at all for linguistic or communicative features. In teaching

English to young beginners, an activity-based methodology combined with

a structural/functional syllabus is the best way of organizing input to the

children's acquisition system. D

Received May 1982

Note

1 Krashen and his collaborators talk of 'underusers' as communication—proposals for syllabus design,

of the monitor (those who take little account of the methodology, evaluation'. Regional Institute of English

rules they know when actually producing language), (South India) Newsletter Special Series 1.4. Bangalore.

'overusers' of the monitor (who are inhibited by the Regional Institute of English (South India). 1980.

rules they have learnt), and 'optimum users' of die Report on Bangalore Project. Bulletin No. 4.

monitor. Tongue, R. and J. Gibbons. 1982. 'Structural

syllabuses and the young beginner'. Applied

References Linguistics 111/1:60-70.

Breen, M., C. Candlin and A. Waters. 1979. 'Com- Wells, G. 1979. 'Describing children's linguistic

municative materials design'. RELCJournal 10/2. development at home and at school'. British Educa-

The British Council, Hong Kong. 1980. Pair Work and tion Research Journal 5/1.

Group Work (film). Widdowson, H. G. 1978. Teaching Language as Com-

Hong Kong Government Information Services. 1976. munication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The Four Stage Method (film). Wilkins, D. A. 1976. Notional Syllabuses. Oxford:

Huang, Joseph and Evelyn Hatch. 1978. 'A Chinese Oxford University Press.

child's acquisition of English' in E. Hatch (ed.). Young, R., E. Laine, P. Gibbons and L. Bradnack.

Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, Mass: Newbury 1983. Lmk Up: The British Council English Course for

House. Primary Schools. H o n g Kong: Evans.

Huang Yongsong et al. 1979. Games Chinese Children

Play (Zhongguo Tongwan). Taiwan: Echo (Han- The author

sheng Congshu). Richard Young has taught English, trained teachers,

Krashen, S. D. 1977. The Monitor Model for adult and written materials in Italy, London, Hong Kong,

second language performance' in M. Burt, H. and China. Since 1979 he has been Materials and

Dulay, and M. Finocchiaro (eds.). Viewpoints on Methodology Officer for the British Council in Hong

English as a Second Language. New York: Regents. Kong, where he directs refresher courses for primary

Krashen, S. D. 1981. Second Language Acquisition and and secondary school teachers and is leading a team of

Second Language Learning. Oxford: Pergamon. authors to produce a new course of English for Hong

Prabhu, N. S. and D. Carrol. 1980. Teaching English Kong primary schools—Link Up.

206 Richard Young

You might also like

- Language Play by Cook PDFDocument8 pagesLanguage Play by Cook PDFjuliaayscoughNo ratings yet

- 3.MTiny Discover Getting Started ActivitiesDocument58 pages3.MTiny Discover Getting Started ActivitiesLegado OnlineNo ratings yet

- Essential Linguistics CH 1 PDFDocument22 pagesEssential Linguistics CH 1 PDFAfni RikaNo ratings yet

- Pitch Anything - An Innovative Method For Presenting, Persuading, and Winning The Deal Oren KlaffDocument9 pagesPitch Anything - An Innovative Method For Presenting, Persuading, and Winning The Deal Oren KlaffJon LecNo ratings yet

- Linguistic and Literacy Development of Children and AdolescentsDocument37 pagesLinguistic and Literacy Development of Children and AdolescentsJona Addatu77% (13)

- Stages of Language Acquisition in The Natural ApproachDocument17 pagesStages of Language Acquisition in The Natural ApproachTanzeela KousarNo ratings yet

- Second Language Acquisition and Bilingualism at An Early Age and The Impact On Early Cognitive DevelopmentDocument4 pagesSecond Language Acquisition and Bilingualism at An Early Age and The Impact On Early Cognitive DevelopmentEric YeNo ratings yet

- LILIAN INGRID MASUNGO Evaluation of Two Language Acquisition TheoriesDocument6 pagesLILIAN INGRID MASUNGO Evaluation of Two Language Acquisition TheoriesnyashanuemNo ratings yet

- Teaching English As A Second Language Theory + Methods + CreativityDocument9 pagesTeaching English As A Second Language Theory + Methods + CreativityالمدربحسنأيتعديNo ratings yet

- The Scope of Psycholinguistics Studies and The SigDocument9 pagesThe Scope of Psycholinguistics Studies and The SigAdhi Jaya Chucha ChoChesNo ratings yet

- Language Acquisition Dissertation TopicsDocument7 pagesLanguage Acquisition Dissertation TopicsPurchaseCollegePapersUK100% (1)

- ELT 1 Module 3Document4 pagesELT 1 Module 3Kristine CantileroNo ratings yet

- TESOL Diploma Assignmen1Document7 pagesTESOL Diploma Assignmen1harmeen virmaniNo ratings yet

- The Acquisition-Learning DistinctionDocument9 pagesThe Acquisition-Learning DistinctionNatalisa Krisnawati100% (1)

- First and Second Language Acquisition TheoriesDocument7 pagesFirst and Second Language Acquisition TheoriessincroniaensenadaNo ratings yet

- Lightbown - Moja SkriptaDocument27 pagesLightbown - Moja SkriptaAnonymous eLcaZeRNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Language Exposure and Artificial Linguistic Environment On Students' Vocabulary AcquisitionDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Language Exposure and Artificial Linguistic Environment On Students' Vocabulary AcquisitionGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Theories of Second Language AcquisitionDocument14 pagesTheories of Second Language AcquisitionDiana Leticia Portillo Rodríguez75% (4)

- Language Acquisition Theories and ResearchDocument4 pagesLanguage Acquisition Theories and ResearchAnnette JohnNo ratings yet

- Interference of First Language in Second Language AcquisitionDocument6 pagesInterference of First Language in Second Language AcquisitionCarlos Alberto Cabezas Guerrero100% (1)

- EL103 Module 4Document9 pagesEL103 Module 4Zandra Loreine AmoNo ratings yet

- Beed 36 Content and Pedagogy For The Mother Tongue TopicsDocument8 pagesBeed 36 Content and Pedagogy For The Mother Tongue TopicsJaibel Borbe100% (1)

- Influence of Behaviourist and Cognitivist Theories in Adult Language AcquisitionDocument7 pagesInfluence of Behaviourist and Cognitivist Theories in Adult Language AcquisitionDhiya HaniffaNo ratings yet

- EL103 Module 3Document11 pagesEL103 Module 3Zandra Loreine AmoNo ratings yet

- Theory Unit 2 - Teorias Generales Sobre El Aprendizaje y La Adquisicion de Una Lengua Extranjera.Document11 pagesTheory Unit 2 - Teorias Generales Sobre El Aprendizaje y La Adquisicion de Una Lengua Extranjera.Carlos Lopez CifuentesNo ratings yet

- What Is Language AcquisitionDocument6 pagesWhat Is Language AcquisitionIva AlvinaNo ratings yet

- Language Acquisition Aspect of LanguageDocument38 pagesLanguage Acquisition Aspect of LanguageVerlandi PutraNo ratings yet

- 690 2704 1 PBDocument5 pages690 2704 1 PBAniz SofeaNo ratings yet

- Term Paper Second Language AcquisitionDocument4 pagesTerm Paper Second Language Acquisitionea85vjdw100% (1)

- Krashens Language Acquisition HypothesesDocument6 pagesKrashens Language Acquisition HypotheseskiranNo ratings yet

- TEYL 2 Zehra Elif KurtDocument3 pagesTEYL 2 Zehra Elif Kurtkurtze202No ratings yet

- Age and Learning Environment Are Children Implicit Second Language LearnersDocument24 pagesAge and Learning Environment Are Children Implicit Second Language LearnersRose WardNo ratings yet

- Winter87 88 2a2bDocument19 pagesWinter87 88 2a2bBaihaqi Zakaria MuslimNo ratings yet

- Educ 101 ReviewerDocument50 pagesEduc 101 ReviewerTom Cyrus VallefasNo ratings yet

- Applied Linguistics Workshop 1Document4 pagesApplied Linguistics Workshop 1OdisseusMerchanNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument10 pagesResearch Proposalmaulidarahmah723No ratings yet

- INTRO TO LINGUISTIC (REPORTER #5) Linguistic Theories and ModelsDocument20 pagesINTRO TO LINGUISTIC (REPORTER #5) Linguistic Theories and Modelsfrieyahcali04No ratings yet

- Thesis Language AcquisitionDocument6 pagesThesis Language Acquisitionpak0t0dynyj3100% (2)

- A Summary of Stephen Krashen's "Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition"Document10 pagesA Summary of Stephen Krashen's "Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition"Eka PajarwatiNo ratings yet

- Subject.docx مقالة 1Document4 pagesSubject.docx مقالة 1Ali Shimal KzarNo ratings yet

- Linguistics and Education: Mila Schwartz, Inas Deeb, Sujoud HijazyDocument11 pagesLinguistics and Education: Mila Schwartz, Inas Deeb, Sujoud HijazyAdina Alexandra BaicuNo ratings yet

- Paola Montero Martinez Group 28 SLA Assignment: February 27, 2011Document8 pagesPaola Montero Martinez Group 28 SLA Assignment: February 27, 2011Daniel Vilches FuentesNo ratings yet

- Makalah PsycholinguisticsDocument28 pagesMakalah PsycholinguisticsLita Trii Lestari100% (2)

- Essay: How Does Native Language Acquisition Influence Second Language Learning?Document9 pagesEssay: How Does Native Language Acquisition Influence Second Language Learning?Sofia GarciaNo ratings yet

- Module - Intreaction TheoryDocument5 pagesModule - Intreaction TheoryRICHARD GUANZONNo ratings yet

- Differences Between l1 and l2Document6 pagesDifferences Between l1 and l2edmundo1964No ratings yet

- SOP FinalDocument6 pagesSOP FinalJhun Mark Bermudez Bayang100% (1)

- Chapter 3Document9 pagesChapter 3aafNo ratings yet

- Thesis About First Language AcquisitionDocument8 pagesThesis About First Language Acquisitiongbwygt8n100% (2)

- Module 3 Linguistic and Literary Development of Children and AdolescentDocument8 pagesModule 3 Linguistic and Literary Development of Children and Adolescentjaz bazNo ratings yet

- Critical Review of Second Language AcquisitionDocument6 pagesCritical Review of Second Language Acquisitionamalia astriniNo ratings yet

- Chapter One: 1.1. Language Learning and AcquisitionDocument14 pagesChapter One: 1.1. Language Learning and AcquisitionMuhammad Naeem aka Ibn E HaiderNo ratings yet

- Reaction PaperDocument4 pagesReaction PaperLidia Escalona Vidal50% (2)

- Ed 545715Document24 pagesEd 545715ANGELICA BUENONo ratings yet

- Bilingualism and Second Language AcquisitionDocument15 pagesBilingualism and Second Language AcquisitionFimelNo ratings yet

- Makalah SlaDocument8 pagesMakalah SlaisnawitamNo ratings yet

- Bas ThesisDocument52 pagesBas ThesisRed ZepetoNo ratings yet

- The Quest For The LadDocument12 pagesThe Quest For The LadSofia CajicaNo ratings yet

- Shsconf Icepcc2023 02021Document5 pagesShsconf Icepcc2023 02021ANGELICA BUENONo ratings yet

- Linguistic and Literacy Development of Children and AdolescentsDocument11 pagesLinguistic and Literacy Development of Children and AdolescentsLizze Agcaoili ArizabalNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageNo ratings yet

- Connecting Right From the Start: Fostering Effective Communication with Dual Language LearningFrom EverandConnecting Right From the Start: Fostering Effective Communication with Dual Language LearningNo ratings yet

- Class Lang Dice2Document2 pagesClass Lang Dice2lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Heart GoldDocument1 pageHeart Goldlizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Million DollarsDocument1 pageMillion Dollarslizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Eggs BasketDocument1 pageEggs Basketlizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- ClassroomDocument16 pagesClassroomlizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- ConjunctionsDocument7 pagesConjunctionslizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Easter WS4Document1 pageEaster WS4lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Burn CandleDocument1 pageBurn Candlelizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Feel BlueDocument1 pageFeel Bluelizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- All EarsDocument1 pageAll Earslizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Body CrosswordDocument1 pageBody Crosswordlizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Big BootsDocument1 pageBig Bootslizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Cards Box NationalitiesDocument1 pageCards Box Nationalitieslizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Easter WS2Document1 pageEaster WS2lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Cards Box SchoolDocument1 pageCards Box Schoollizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Age 5Document1 pageAge 5lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Cards Box LikesDocument1 pageCards Box Likeslizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- EASTER ws1Document1 pageEASTER ws1lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Class Lang DiceDocument2 pagesClass Lang Dicelizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Cards Box WeatherDocument1 pageCards Box Weatherlizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Cards Box ToysDocument1 pageCards Box Toyslizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Birthdays 5Document1 pageBirthdays 5lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Birthdays 3Document1 pageBirthdays 3lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Birthdays 4Document1 pageBirthdays 4lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Birthdays 1Document1 pageBirthdays 1lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Birthdays 2Document1 pageBirthdays 2lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- Class Lang WS3Document1 pageClass Lang WS3lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- ANIMALS2Document1 pageANIMALS2lizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- ANIMDocument1 pageANIMlizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- PETSDocument2 pagesPETSlizete.capelas8130No ratings yet

- New TIP Course 4 (DepEd Teacher)Document67 pagesNew TIP Course 4 (DepEd Teacher)Eli Jad Capisonda100% (1)

- Human Person in The SocietyDocument8 pagesHuman Person in The Societysara marie bariaNo ratings yet

- PE 8 3Q April 11-14Document8 pagesPE 8 3Q April 11-14ivonne100% (1)

- Prof. Ed. 1 - Module 5Document5 pagesProf. Ed. 1 - Module 5Jomar NavarroNo ratings yet

- ProposalDocument3 pagesProposalMichelleNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment Report in BIG BROTHER BIG SISTER ProgramDocument37 pagesAccomplishment Report in BIG BROTHER BIG SISTER ProgramIvan Dyem C. San PedroNo ratings yet

- Mental DevelopmentDocument12 pagesMental DevelopmentKevin Paul TabiraoNo ratings yet

- Introducing Communication Research Paths of Inquiry 3rd Edition Treadwell Test BankDocument25 pagesIntroducing Communication Research Paths of Inquiry 3rd Edition Treadwell Test BankMatthewRosarioksdf100% (58)

- ACR Numeracy S.Y. 2021-2022Document7 pagesACR Numeracy S.Y. 2021-2022ROSALIE SOMBILON100% (1)

- Summary The Power of Your Subconscious MindDocument2 pagesSummary The Power of Your Subconscious Mindsearching4alphaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 ADocument4 pagesLesson 4 AMark John Casiban CamachoNo ratings yet

- Table of Specification Tos For Solo and Non Sy 22 23Document3 pagesTable of Specification Tos For Solo and Non Sy 22 23NANETTE JALON100% (1)

- ShekinahDocument21 pagesShekinahJoel VicenteNo ratings yet

- Tema 13 - RDocument12 pagesTema 13 - RAlicia Crevillén MorenoNo ratings yet

- FACILITATING LEARNER-CENTERED TEACHING Activity #1Document2 pagesFACILITATING LEARNER-CENTERED TEACHING Activity #1Kim EnriquezNo ratings yet

- TEYL Midterm Test - Agnes Adela Irawan (7B)Document1 pageTEYL Midterm Test - Agnes Adela Irawan (7B)Agnes AdelaNo ratings yet

- Ebook Strategies and Models For Teachers Teaching Content and Thinking Skills PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument39 pagesEbook Strategies and Models For Teachers Teaching Content and Thinking Skills PDF Full Chapter PDFannie.spring47397% (37)

- PsychologyDocument12 pagesPsychologySruthy MoorthyNo ratings yet

- Tute - Week 2 - BUSM2040 UEHDocument24 pagesTute - Week 2 - BUSM2040 UEHmyyyanx123No ratings yet

- Psychology and Its BranchesDocument5 pagesPsychology and Its Branchesumair_besst8827No ratings yet

- Reading Is One of The English Skills Which Are Essential To Be Mastered by The StudentsDocument4 pagesReading Is One of The English Skills Which Are Essential To Be Mastered by The StudentsRegs Cariño BragadoNo ratings yet

- FS2 Ep3Document9 pagesFS2 Ep3Kent BernabeNo ratings yet

- Learning To Coach: An Ecological Dynamics Perspective: International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching November 2022Document13 pagesLearning To Coach: An Ecological Dynamics Perspective: International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching November 2022kevinNo ratings yet

- Usborne 2014Document23 pagesUsborne 2014Gargi KhandweNo ratings yet

- Basis 1 THESIS - Chapter - 1-3Document43 pagesBasis 1 THESIS - Chapter - 1-3Nancy MoralesNo ratings yet

- DLL - Personal Dev.Document4 pagesDLL - Personal Dev.Agnes Ipanto BontilaoNo ratings yet

- MT1OL-Iei-5.1: Name/Triad: ScheduleDocument2 pagesMT1OL-Iei-5.1: Name/Triad: ScheduleTrisha Kate C. GeraldeNo ratings yet

- Dramatics Club Activity Plan - Jun To Aug 2023Document3 pagesDramatics Club Activity Plan - Jun To Aug 2023School MailNo ratings yet