Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Maple Bear - Responsive Differentiated Instruction Handbook

Maple Bear - Responsive Differentiated Instruction Handbook

Uploaded by

Paulo JuniorOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Maple Bear - Responsive Differentiated Instruction Handbook

Maple Bear - Responsive Differentiated Instruction Handbook

Uploaded by

Paulo JuniorCopyright:

Available Formats

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

RESPONSIVE DIFFERENTIATED

INSTRUCTION

BEST PRACTICES

Handbook

1 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

How Do Educational Experts Frame Differentiation?

Differentiation isn’t more work, it’s different work. – Shelley Moore

Students need to know that effort plus perseverance leads to success. This will foster a growth

mindset.

– Dweck, 2010; Gregory & Kuzmich, 2014

When kids are engaged at appropriate levels of challenge, the habits of persistence and curiosity

are developed. [They] are then willing to take intellectual risks. Continuously working with [them]

at their level of readiness is a general education strategy that can help prevent the need for

additional interventions. – Carol Ann Tomlinson

Differentiated instruction is a way “to shake things up” in the classroom, changing how students

learn and how teachers teach. – Thousand, Villa, & Nevin, 2014

Effective differentiation is built on a foundation of engaging, relevant, student-friendly targets that

clearly define expectations for learning. – EL Education, 2021a

Differentiated instruction is a way of thinking about teaching and learning. It is also a collection of

strategies that help [teachers] better address and manage the variety of learning needs in [the]

classroom. – Heacox & Strickland, 2012

The best differentiation is proactively planned. – Carol Ann Tomlinson

When we know our learners, we can make informed choices and adjust . . . teaching processes so

that all students have an optimal chance of succeeding. That is what it is about. – Gregory &

Kuzmich, 2014

Teachers are designers. An essential act of our profession is the design of curriculum and learning

experiences to meet specified purposes. – Wiggins & McTighe, 2005

Differentiation is a complex [endeavour] that requires a range of sophisticated [pedagogical] skills

that are developed over time and with practice. – Tennessee Department of Education, 2018

Differentiating instruction [DI] is rooted in “good teaching” tenets. It is about doing what is fair,

equal, and developmentally appropriate to promote growth for all students. DI involves a

compendium of best practices that teachers consistently and deliberately use to boost learning;

these tools can be employed to adapt anything that is “undifferentiated.” It requires us to do

different things for different students some, or a lot, of the time. It is whatever works to advance

students along the learning continuum.

– Rick Wormeli, 2018

2 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

There is not one single universally designed route for all learners. Treat diversity with flexibility.

– Understood for All, 2019

We need greater curricular focus on what matters most—powerful ideas with transfer.

– Wiggins & McTighe, 2005

Preface

“We believe that nothing is more important than the education of our children.”

Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd [MBGS]. is dedicated to promoting success for all children

through an inclusive school philosophy and program, that meet the requirements of the

mandated educational legislation in each region. Students are welcomed and equitably

supported within differentiated learning communities where they are encouraged to explore,

discover, contribute, and participate in all aspects of school life. The aim is for all students to feel

accepted, valued, and safe. As learners progress, Maple Bear teachers adapt instructional-

assessment approaches to build on student strengths and facilitate maximum academic and

emotional growth. Their teaching approaches are based on differentiation principles and are

highly effective in diverse educational environments. This handbook provides teachers with a

flexible road map for developing programs that are both challenging and responsive to

individual needs. The Responsive Differentiated Instruction: Best Practices document is designed

to help teachers create more opportunities for Maple Bear students to reach their full potential.

3 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Table of Contents

Preface .......................................................................................................................................... 3

List of Tables................................................................................................................................. 6

List of Figures ............................................................................................................................... 6

Section 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7

Inclusion at Maple Bear Schools .......................................................................................................... 7

Maple Bear Core Values and Beliefs .................................................................................................... 7

Maple Bear Teaching Staff.................................................................................................................... 7

Section 2: Model for Addressing Diversity .................................................................................. 9

The Three-Tiered Pyramid Model....................................................................................................... 9

Features of the Three-Tiered Pyramid Model ........................................................................................................... 9

Application of the Three-Tiered Pyramid Model in Practice ................................................................................. 10

Section 3: Differentiation ........................................................................................................... 12

Introduction to Differentiation ......................................................................................................... 13

Philosophy of Differentiation ............................................................................................................ 13

Definition and Rationale .................................................................................................................... 13

Benefits of Differentiated Instruction............................................................................................... 14

Good Teachers ..................................................................................................................................... 14

Constructive Teacher Feedback ........................................................................................................ 14

Equal Access to the Curriculum ......................................................................................................... 14

The Differentiated Learning Continuum .......................................................................................... 15

Hallmarks of Supportive Differentiated Classrooms ...................................................................... 15

What Differentiated Instruction “Is” and “Is Not” ............................................................................ 15

(A) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Where to Begin? ....................................................... 17

(B) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: 4 Key Features .......................................................... 19

Content [The “what” of teaching] ............................................................................................................................. 19

Process [The “how” of teaching] .............................................................................................................................. 20

Product [The end result of learning]........................................................................................................................ 21

Learning Environment (Affect) [How students feel in class] ................................................................................. 22

(C) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Data Collection Measures ........................................ 23

Readiness ................................................................................................................................................................... 24

Readiness refers to students’ knowledge and skills in relation to a specific curricular objective; it is not the

same as intellectual capacity or ability. Readiness levels are affected by an individual’s background

knowledge, experiences, and previous exposure to the topic. Hence, these levels can seesaw markedly across

subject areas (Tomlinson, 2014). Readiness differentiation is at work when teachers present developmentally

appropriate educational activities that are “in advance” of children’s current stage of mastery (Zone of

4 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Proximal Development-ZPD, Vygotsky, 1978); this means “raising the ceiling” for all students by supplying

legitimate levels of scaffolding and challenge. One tangible benefit is that they can directly connect their

persistent efforts to positive academic results (Byrdseed, 2009; Dweck, 2010; Utah State Board of Education

& Hanover Research, 2019). These tailored activities also help learners to bridge the gap between

dependence and independence. ............................................................................................................................... 24

Interests ..................................................................................................................................................................... 25

Learning Profiles ....................................................................................................................................................... 26

(D) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Backward Design Framework ................................ 27

Three Stages of Backward Design ............................................................................................................................ 29

(E) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Universal Design for Learning (UDL) ..................... 31

UDL Principles & Guidelines ..................................................................................................................................... 31

Role of Technology .................................................................................................................................................... 32

(F) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Assessment................................................................ 36

Purposes of Differentiated Assessment ................................................................................................................... 36

Principles of Differentiated Assessment.................................................................................................................. 36

Teacher Responsibilities in Differentiated Assessment ......................................................................................... 38

Three Types of Assessment Techniques .................................................................................................................. 38

(G) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Lesson Development ................................................ 41

(H) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Strategy Selection .................................................... 43

Section 4: Glossary of Differentiated Concepts and Strategies ................................................ 46

Section 5: References ................................................................................................................. 61

Section 6: Appendices – Teacher Resources.............................................................................. 77

Appendix A: Planning Template I ...................................................................................................... 77

Appendix B: Planning Template II .................................................................................................... 78

Index ........................................................................................................................................... 80

5 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

List of Tables

Table 1. What Differentiated Instruction Is and Is Not

Table 2. Differentiated Activities Requiring Low-Prep and High-Prep

Table 3. The Three UDL Principles

Table 4. Student-Friendly UDL Learning Activities

Table 5. Differentiated Instruction Technology-Based Tools

Table 6. How to Plan for Differentiation

Table 7. Differentiating in Testing Situations

Table 8. Strategy Instruction Step-By-Step

Table 9. Differentiated Teaching Strategies

List of Figures

Figure 1. The Three-Tiered Pyramid Planning Model

Figure 2. Features of Differentiated Instruction

Figure 3: Bloom’s Taxonomy

Figure 4. Learner Characteristics Guide Differentiation

Figure 5. Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development

Figure 6. Learning Preferences Continuum Assessment Chart

Figure 7. Stages of Backward Design

Figure 8. Lesson & Unit Planning Sequence: Stages 1 – 3

Figure 9. The Universal Design for Learning Guidelines

Figure 10. Characteristics of Effective Assessment

Figure 11. Differentiated Lesson Planning Summary: What Teachers Do

Figure 12. Backward Design Lesson Planning Template I

Figure 13. Backward Design Lesson Planning Template II

6 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Section 1: Introduction

Inclusion at Maple Bear Schools

Maple Bear schools are inclusive communities, that are continuously evolving to address the

changing needs of students. Each school embraces inclusion as a means of enhancing the well-

being of every member of its population. Ongoing professional development and on-site,

collaborative efforts help Maple Bear school teams to bolster their capacity to provide the

foundation for a richer future for ALL.

At Maple Bear [MBGS], children with diverse learning and behavioural needs will experience

school in much the same way as their peers. In order to increase accessibility for every student,

MBGS educational professionals:

• Nurture school and classroom communities where all students, including those with

diverse needs and abilities, have a sense of personal belonging and achievement.

• Identify and foster practices by which students, with a wide range of learning needs, can

be taught together effectively.

• Enhance, through modelling and instruction, student abilities to cope with diversity.

• Offer students an environment that provides potential for dignified, meaningful

relationships.

• Provide all students with appropriate supports to develop their “personal best” within a

context that respects their abilities (MBGS Planning for Students with Special Needs).

Maple Bear Core Values and Beliefs

In most cases, Maple Bear programming consists of the regular curricular outcomes. However,

some students may also require individual or student-specific adaptations to fully access

classroom activities and achieve optimal levels of school success. All of our programs are

delivered in a positive educational setting, that include resources and services which are

responsive to the learning, social-emotional, and behavioural needs of all students. Maple Bear

emphasizes a preventative, proactive, and supportive process to develop the most effective

approaches to teaching and learning (MBGS Planning for Students with Special Needs).

Maple Bear Teaching Staff

Maple Bear teachers are committed to providing high-quality instruction to a broad range of

diverse students. To encourage optimal achievement and engagement, teachers:

(1) consider the scope of student abilities and learning styles;

(2) use flexible goals, methods, materials, and assessments to accommodate learner differences;

(3) focus on creating educational environments matched to students’ learning preferences,

abilities, and interests;

(4) create classroom conditions that encourage all students to take educational risks, stretch

their skills, and attain maximum school success; and

7 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

(5) embrace responsive, proactive strategies, informed by the principles of Universal Design for

Learning [UDL] and Differentiated Instruction [DI] (MBGS Planning for Students with Special

Needs).

8 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Section 2: Model for Addressing Diversity

Maple Bear [MBGS] classrooms are diverse communities that include students with varied

interests, abilities, needs, learning styles, and cultural backgrounds. Implementation protocols

linked to accessibility, differentiated instruction [DI], inclusion, backward design, and Universal

Design for Learning [UDL] guide our efforts to create educational contexts where all students

can learn together and thrive (MBGS Planning for Students with Special Needs). MBGS teachers

consistently use an array of evidence-based learning continuums, strategies, and methodologies

to propel development, limit educational barriers, and increase success for all students.

The Three-Tiered Pyramid Model

The Three-Tiered Pyramid Model (Fox et al., 2003) also serves as a planning template to

facilitate student learning at Maple Bear schools. This three-level intervention tool provides a

continuum of scaffolds and services designed to support “typically developing” students and

those who may experience educational challenges along the way [Tier 1: “Universal” supports

for all students; Tier 2: “Targeted” supports for some students; and Tier 3: “Intensive” supports

for a few students].

The Three-Tiered Pyramid Model is:

• built on the premise that most learners will thrive if responsive, timely, universal

supports are readily available to ALL (Learn Alberta, 2010);

• focused on proactively addressing academic and behaviour challenges before learning

and success are derailed;

• highly effective when the key tenets of the approach are enacted with rigour and fidelity;

• linked to data-driven approaches (UDL, DI, ZPD, Backward Design); and

• centred around structures that embrace a collaborative, team-based orientation to

support service delivery (MBGS Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for

Schools).

Features of the Three-Tiered Pyramid Model

This powerful framework: (1) represents a continuum that can be used in many contexts

(school-wide, classroom, individual); (2) involves a systematic process; (3) applies to multiple,

evidence-based learning, socio-emotional, and behavioural strategies and interventions, to

support varying ages and developmental levels; (4) includes assessment “for, of, as” learning, as

well as individual and classroom profiles; (5) emphasizes strengths, needs, priorities, and

proactive planning for all students; (6) can be strategically used; (7) provides access to

programming aimed at academic, behavioural, and socio-emotional development; (8) begins

with universal curricular entry points and gradually introduces appropriate degrees of

complexity, based on student needs; and (9) adheres to the principles of “good teaching” (MBGS

Planning for Students with Special Needs).

9 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Application of the Three-Tiered Pyramid Model in Practice

The Three-Tiered Pyramid Model is designed to identify strengths, needs, and priorities; it

offers a continuum of proactive, responsive strategies applicable to all students. This framework

can be readily adapted to changes in academic learning, behaviour, and social-emotional

development (universal, targeted, intensive). Thus, a range of needs can be successfully

addressed by fine-tuning the complexity and intensity of supports. A student’s placement in a

tier is fluid; fluctuations are expected because competency and skill vary across subject areas

(over time).

10 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Figure 1. The Three-Tiered Pyramid Planning Model

Tier 3 [Intensive Individual Instruction]

• Intensive Intervention

• 5-10% of students [FEW]

• IEPs (modifications)

• Intensive, systematic, daily intervention over a long period of time

• Students who are not progressing are referred for additional assessment

Tier 2 [Targeted Group Intervention]

• Supplementary, Targeted Intervention

• Students with demonstrated gaps in learning

• Adaptations of regular education curriculum

• 15-20% of students [SOME]

• Targeted, systematic, 3-5 times/week for a term or portion of the year

• Students who are not progressing move to “temporary” Tier 3 interventions

Tier 1 [Universal Programming, School-Wide Supports]

• Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

• Differentiated Instruction (DI)

• Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

• Proactive planning with common entry points for ALL

• Regular education programs, including strategic scaffolding

• Implementation of research-based, best practices

• Use of learning continuums

• Emphasis on frequent, formative assessment & valid feedback for students & parents

• Students who are not progressing move to “temporary” Tier 2 intervention

Sources: Adapted from Edmonton Public Schools. 2013; MBGS Planning for Students with Special Needs; Ontario

Ministry of Education, 2011

11 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Section 3: Differentiation

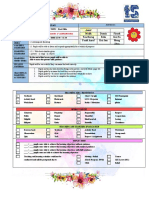

Figure 2. Features of Differentiated Instruction

MBGS teachers see DI as a proactive, growth-oriented approach that includes:

backward design; flexible groupings & choice; UDL; responsive programs tied to student variances;

respectful/ purposeful tasks; the 3-tiered pyramid model; a safe, supportive learning climate; equitable

access to curriculum; adaptable management structures & routines; and ongoing assessment driving

instruction.

Teachers differentiate

Content Process Product Learning Environment

The information & ideas How students How students show How students “feel” in the

students wrestle with to internalize & process what they can do, classroom

reach learning goals content material know & understand

based on students’ individual

Readiness Interests Learning Profiles

specific student learning goals inclinations, passions, & preferred learning modes

affinities

through a range of instructional & management strategies including:

• multiple intelligences • small group instruction • mix of questioning techniques

• jigsaws • tiered lessons • curriculum compacting

• recorded materials • stations & products • scaffolded teaching

• anchor activities • independent studies • different levels of complexity

• graphic organizers • learning contracts • varied interest centres,

• varied texts/support material • orbitals homework tasks & groupings

• literature circles • group investigations • journaling prompts

12 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Sources: Adapted from EL Education, 2021a; Newfoundland & Labrador Department of Education, n.d.; Ontario

Ministry of Education, 2013; Tomlinson & Moon, 2013

Introduction to Differentiation

The chief job of schools is to increase the capacity of all individuals (Tomlinson, 2000). Helping

students to become self-directed learners, independent thinkers, and productive problem-

solvers is central to the process (Costa & Kallick, 2000, cited in Chapman & King, 2009).

Differentiated instruction allows teachers to proactively consider each aspect of the child,

including the unique intelligences, learning styles, and emotional predispositions (Chapman &

King, 2009). To be effective, educators must establish a careful balance between academic

content and student needs (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). The ultimate goal of differentiation is

to underscore differences and strengths, not mask them. This information is vital for designing

effective, flexible curricular content, learning activities, and formative-summative assessments

(The Iris Center, 2012; Tomlinson, 2017).

Philosophy of Differentiation

Differentiated instruction [DI] is one of the ways with which educators establish supportive

learning conditions that promote success for all students (Manitoba Education & Youth, 1996).

It is a research-based, flexible model of classroom practice intended to assist practitioners in

developing meaningful curriculum and instructional approaches that maximize the capacity of

diverse groups of learners (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). Simply put, DI is both a “frame of mind”

and a philosophy founded on the premise that teachers must adapt instruction to match

students’ intrinsic differences. Why? Because a rigid, “one-size-fits-all” orientation is likely to

fail (Tomlinson, 2015). Supporters of differentiation believe that: (1) students’ brains are as

distinctive as their fingerprints; (2) teacher and student attitudes matter, (3) continuous,

informal assessment is necessary, and (4) opportunities for learning are always present (Dweck,

2010; Gregory & Kuzmich, 2014).

Definition and Rationale

Differentiated Instruction [DI] is recognized as a compilation of many, evidence-based theories

and practices that is fully embraced at Maple Bear schools (i.e., UDL, Inclusion, ZPD, etc.). This

teaching approach involves a series of instructional (and assessment) techniques that are

designed to be systematically applied, so that all children can participate in engaging classrooms

and feel part of the learning community (Hall et al., 2004). When these kinds of curricular

recalibrations are in place, educators are able to more intentionally respond to learning

proclivities, readiness, cultures, interests, and strengths and, in so doing, positively contribute to

student success (Manitoba Education & Advanced Learning, 2015; MBGS Planning for Students

with Special Needs). At its most rudimentary level, differentiation is all about the efforts of

teachers to address individual differences and to successfully educate as many students as

possible (Lombardi, 2019; Tomlinson, 2000).

13 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Benefits of Differentiated Instruction

• Research shows that differentiated instruction is effective for high-ability students and

for those with mild to severe disabilities.

• When students have several options for processing content material, they take on more

responsibility for their own learning.

• Differentiated classrooms increase opportunities for students to actively engage in

learning; fewer unproductive behaviours surface in such environments.

• Using the reading, writing, and math continuums and grouping students for ‘just right’

instruction-assessment are effective ways to differentiate practice (MBGS Understanding

& Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools).

Good Teachers

Good teachers understand that they have content and skills to cover, students who need to learn

those skills, and noticeable variances among the members of the classroom community. This, in

essence, is differentiation (Doubet & Hockett, 2017). At Maple Bear schools, we accept that all

educators differentiate to some extent. It is in the nature of teaching to recognize individual

learning behaviours and to shape instruction and classroom organization accordingly (MBGS

Planning for Students with Special Needs). In their role as adept, professional “designers,”

teachers are able to effectively respond to any group of multi-dimensional learners.

Nevertheless, experts admit that there is no “silver bullet” when it comes to making sound

differentiated-based decisions (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2020). In the early implementation phases,

the general consensus is to start small (Gregory & Kuzmich, 2014; Heacox & Strickland, 2012).

Constructive Teacher Feedback

Constructive (descriptive) feedback is one of the important features of a rich differentiated

class. At Maple Bear schools, educators are encouraged to consistently respond to children in

ways that are fair, predictable, clear, respectful, and helpful (MBGS Understanding & Guiding

Behaviour: A Resource for Schools). When students receive affirmative “messages of possibility”

from teachers, they tend to be more optimistic, persistent, and confident in their learning

abilities (i.e., growth mindset). Without meaningful, frequent reassurance, students may see

themselves as incapable and simply withdraw (i.e., fixed mindset) (Dweck, 2010). Thus, high-

calibre feedback is a key ingredient on the path to school success (Gregory & Kuzmich, 2014;

Tomlinson, Moon, & Imbeau, 2015).

Equal Access to the Curriculum

Differentiated programming is inherently flexible, rigorous, varied, relevant, and complex

(Heacox & Strickland, 2012). It forms a seamless part of everyday planning and classroom

practice. Student access to curricular content, in a manner best-suited to performance levels,

learning styles, and interests is prioritized; individual needs are “honoured” and learning

capacity is accelerated (The Iris Center, 2021; Tomlinson & Strickland, 2005).

14 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

To maximize accessibility, accommodate differences, and cultivate success, teachers must

nimbly weave a combination of instructional strategies, curricular lessons, and performance-

based assessments into their daily classroom activities (Huebner, 2010, cited in Utah State

Board of Education & Hanover Research, 2019).

The Differentiated Learning Continuum

It is anticipated that teachers begin “where the students are” (i.e., what they know & what they

need to know). For learners to thrive, instructional and assessment practices must be

thoughtfully introduced; these practices must “capitalize” on individual interests and strengths,

in order to fuel significant growth (Heacox & Strickland, 2012; Tomlinson, 1999). In

differentiated classrooms, multiple openings for exploring, sense-making, and demonstrating

understanding are available to students as they advance through the various stages of the

designated learning continuum.

Hallmarks of Supportive Differentiated Classrooms

At Maple Bear schools, education practitioners create welcoming, inclusive school communities

that are designed to meet students’ academic and social needs. In these settings, it is expected

that everyone will make gains across an array of skill areas (MBGS Planning for Students with

Special Needs). Educators play a crucial role in building robust schools that function optimally

and challenge all learners. In differentiated classrooms, teachers: (1) acknowledge students’

idiosyncratic differences, interests, strengths, creativity, and learning inclinations; (2) use

flexible student groupings to complete classroom tasks; (3) realize the role of motivation, effort,

confidence, and belonging in the educational process; (4) encourage independence and personal

responsibility for learning; and (5) construct activities that provide several avenues to success

(Heacox & Strickland, 2012; Wormeli, 2018). All of these elements are interrelated and

symbiotic (Tomlinson, & Moon, 2013).

What Differentiated Instruction “Is” and “Is Not”

Differentiated instruction is a dynamic, student-centred, inclusive teaching approach; it is

underpinned by the belief that everybody is able to learn (Manitoba Education & Youth, 1996).

Student learning can be dramatically influenced when DI is well executed (Hall et al., 2004). But

this involves more than a few decision-making procedures and instructional activities

(Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015). Rather, “the . . . more elegant truth is that effective teaching is a

system composed of interdependent elements. [Like] all systems, each part is enhanced when

others are [fortified] and each part is diminished when any part is weakened” (Tomlinson &

Moon, 2013, p. 1).

15 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Table 1. What Differentiated Instruction Is and Is Not

DI is . . .

- a philosophy or set of beliefs for diversifying teaching and learning

- proactive, dynamic, and “organic”

- fine-tuned to all students’ readiness, interests, learning styles, and prior experiences

- aligned with the principles of inclusion, backward design, and UDL

- about creating “ideal” learning conditions for all individuals

- responsive to all students’ need for support or challenge

- more qualitative than quantitative

- a collaborative endeavour

- driven by ongoing assessment and high expectations

- about adjusting content, process, work products, and learning environments to promote

growth

- student-centred

- designed to include multiple pathways to success (strategic scaffolding & structured choices)

- about using a rich repertoire of individual, small group, and whole-class instructional

strategies

- most effective when it is engaging, relevant, and interesting

- rooted in good teaching

DI is not . . .

- about “dumbing down” the curriculum

- individualized instruction

- an isolated component of the teaching process

- about placing struggling students in separate “pull-out” programs

- a classroom “add-on”

- standardized instruction geared towards the “allegedly average” learner (“teach to the

middle”)

- a sequence of fragmented educational activities

- about affixing labels to students

- a pre-determined “recipe” for teaching and learning

- about organizing students into fixed, ability groupings

- a reactive response to learner difficulty

- about “all students doing the same thing, in the same way, at the same time”

- a “one-size-fits-all” methodology

- what teachers do when they have extra time

- designed only for particular grades, subjects, or students (special needs)

Sources: Adapted from Edugains, 2016b; Lombardi, 2019; Thousand et al., 2014; Tomlinson, 2000, 2014, 2017

16 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

(A) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Where to Begin?

An important underlying belief is that children can learn, given suitable classroom conditions.

But there is no “silver bullet” when it comes to transforming schools into inclusive,

differentiated hubs. The conventional wisdom is to seek out the support of like-minded

colleagues and “start small.” It is also wise to analyze existing practices and select an area of

accessibility that is of concern (Heacox & Strickland, 2012; Tomlinson, 2000a, 2004). Newly

designed approaches often target one of the four key DI features: content, process, product, or

learning environment. Nonetheless, any instructional choices should be balanced, coherent,

deliberate, challenging, and tightly blended with students’ readiness (needs, prior knowledge),

interests (choices, background), or learning profiles (styles, multiple intelligences) (Heacox &

Strickland, 2012). In a nutshell, this process involves a cycle of continuous assessment, planning,

instructing, reflecting, and adjusting; the aim is to promote maximum growth and success.

Fortunately, there is a plethora of responsive, “low- and high-prep” activities, materials, and

exercises with which to experiment; teachers are urged to take calculated pedagogical “risks,” to

establish the best fit for individual learners.

17 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Table 2. Differentiated Activities Requiring Low-Prep and High-Prep

DI Activities Requiring Minimal Prep DI Activities Requiring more Prep

- Activity options [design-a-day, let’s make a deal] - Assessment options

- Assistive technology - Centres/stations [readiness, interest, profile]

- Book choices - Choice boards

- Computer buddies - Community mentorships

- Cooperative team-building tasks - Curriculum compacting

- Demonstration of knowledge options - Cubing

- Digital curriculum [if MBGS approved] - End-of-chapter pretest

- Exit cards - Entry points (universal)

- Explorations [based on interests] - Flipped classroom

- Games to practise [mastery] - Graduated rubrics

- Goal setting [student-teacher] - Graphic organizers

- Graffiti wall - Group investigations

- Homework options - Hands-on activities

- Jigsaws - Independent studies

- Journal-prompt variations - Interest groups

- Levelled questions [Bloom’s Taxonomy] - Interview students

- Manipulatives - Learning contracts

- Mentors [computer, math, etc.] - Literature circles

- Mini lessons [re-teach/extend skills] - Low-floor high-ceiling tasks (math)

- Modes of “expression” variations - Menus

- Negotiated criteria - Multiple-intelligence options

- One-to-one chats - Oral tests/exams

- Open-ended activities - Personal agendas

- Orbitals - Problem-based learning

- Pacing variations [with anchor options] - Reading format options

- RAFTs - Recorded materials

- Reading buddies - Simulations (“simulated authenticity”)

- Scaffolding variations - Study guides/handouts

- Seating flexibility - Surveys

- Software/learning app options - Student-centered [design a project]

- Student-teacher activity negotiations - Task cards

- Supplementary material options - Text options [choice]

- Think-pair-share - Tic-Tac-Toe

- Timeline variations - Tiered complexity [tasks, centres, labs, products]

- Whole-to-part explanations - Tournaments

- Work in partners, small groups (pods), alone - Web inquiries

Sources: Adapted from Alberta Education, 2010; Chapman & King, 2005; Edugains, 2016b; Enome, Inc., 2021;

Heacox & Strickland, 2012; Learn Alberta, 2013; MB Effective Differentiation PowerPoint: Patti Rodger, 2021;

McTighe & Wiggins, 2011; NL Department of Education. n.d.; The Iris Center, 2013; Tomlinson, 2000, 2004, 2014

18 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

(B) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: 4 Key Features

Effective differentiated approaches call for the flexible delivery of tailored instruction, to optimize

individuals’ knowledge acquisition and skill development. Experts agree that translating DI

principles into diverse classrooms cannot be accomplished without assessment data and careful,

proactive planning; this planning is predicated on students’ readiness, interests, and learning

profiles (Manitoba Education & Training, 2015; Thousand et al., 2014; Tomlinson, 2014;

Tomlinson & Strickland, 2005). Four key features inform the differentiated decision-making

process: (1) content, (2) process, (3) products, and (4) learning environment. Differentiating

instruction involves the deliberate manipulation of one or more of these features. Teachers

must continually assess; reflect; and adjust content, process, product, or learning environment

to meet student needs.

Content [The “what” of teaching]

Content refers to the curricular concepts, principles, and skills that students must consolidate.

In DI classes, everyone explores the same “big ideas” (core program goals). Appropriate

scaffolding and presentation modes, (tied to needs), accompany this teaching approach

(Tomlinson, 1999). Maple Bear schools have a prescriptive and well-researched curriculum

extending from early childhood to high school. However, students’ competencies deviate greatly

(MBGS Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools). It is recommended that

teachers avoid “watering down” subject matter. Rather, attention should be placed on

instructional methods and materials that enhance students’ access to “essential” information

(Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010).

Figure 3. Bloom’s Taxonomy

Sources: Adapted from Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001; Armstrong, 2010, Ontario Ministry of Education, Literacy &

Numeracy Secretariat, 2011

19 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Examples of Differentiating Content:

• Ask students to match vocabulary words to definitions

• Introduce content activities that are compatible with students’ prior knowledge and

needs

• Dive into the Bloom’s Taxonomy toolkit to design differentiated tasks

• Use audio-recordings of learning materials

• Assign a reading passage with questions for students to answer

• Organize reading buddy pairs

• Prepare readiness-appropriate vocabulary and spelling lists

• Adapt instruction of curricular topics for struggling to advanced students

• Present abstract concepts and ideas through visual-auditory means

• Encourage students to create a PowerPoint presentation summarizing the lesson

• Introduce concept-focused, “considerate” texts with different readability levels

• Have learners identify the author’s position and provide evidence to support this

viewpoint

• Provide text-to-speech software to ease access to print-based activities

• Tell students to create an alternate ending for a story (or add a new character)

• Ensure that learning tasks correspond directly with curricular outcomes, standards, and

goals

• Ask students to differentiate fact from opinion in a story or expository-text selection

• Accentuate the same “essential” concepts, principles, and skills for ALL (adjust

complexity) (Hall et al., 2004; Heacox & Strickland, 2012; MBGS Understanding & Guiding

Behaviour: A Resource for Schools; Tomlinson, 1999, 2000a).

Process [The “how” of teaching]

Process refers to a range of engaging, skill-building activities that teachers incorporate into their

lessons (Tomlinson, 1999). The process-related activities contain layers of support and

difficulty that are adjusted in response to student challenges, interests, and preferences. Maple

Bear teachers understand that they can enrich student learning by offering support based on

individual needs (MBGS Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools). When DI

processes are deployed strategically, learners are able to more easily understand and assimilate

the ideas under study. The ultimate goal is for students to: (1) be fully engaged, (2) take

calculated academic risks, and (3) gain greater autonomy as self-directed learners (Tomlinson &

Imbeau, 2010; Tomlinson & Moon, 2013).

Examples of Differentiating Process:

• Supply textbooks for visual and word learners

• Give auditory learners opportunities to utilize audiobooks

• Provide kinesthetic learners with access to interactive tasks online (models, dioramas,

etc.)

• Teach new concepts using tiered activities

• Develop interest centres to facilitate exploration of subsets within class topics

• Generate personal agendas (task lists) with flexible deadlines

• Leverage technology to overcome print-related barriers

20 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

• Provide manipulatives and other scaffolds, based on student needs

• Adjust assignment depth and timelines to accommodate struggling and advanced

learners

• Organize dynamic student groupings, including whole-class introductory lessons (“big

ideas”), small-group configurations, and paired work

• Design classroom management strategies, including organizational and instructional-

delivery procedures, that are based on differentiation principles

• Introduce a mixture of tasks, materials and equipment, aimed at honing students’

divergent levels of critical-creative thinking skills

• Present the “low-floor high-ceiling” strategy (Jo Boaler) to promote access and advanced

skill development [Math] (Hall et al., 2004; Heacox & Strickland, 2012; MBGS

Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools; Tomlinson, 1999, 2000a).

Product [The end result of learning]

Product refers to projects that are completed at the end of a unit. In differentiated contexts,

teachers develop culminating assignments based on three characteristics: readiness, interests,

and learning profiles (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). Thus, opportunities are provided for

students to show mastery of the same conceptual material (in various ways). Final products also

evaluate whether individuals can “apply and extend” new knowledge in unpredictable

situations, beyond the schoolhouse doors (MBGS Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource

for Schools; Tomlinson, 1999).

Examples of Differentiating Products:

• Allow students to produce a range of tangible, hands-on products such as: puppet shows,

dances, letters, murals, brochures, models, dialogues, speeches, skits, debates, or mock

trials

• Employ rubrics that help students to stretch their skill development and show

competency

• Permit the class to work independently or in small groups

• Give learners a chance to submit original works that express their knowledge and skills

• Offer choices, scaffolds, and “menus of projects,” adapted to diverse needs and interests

• Provide strategic access for students to do interviews, surveys, and performance

evaluations

• Ensure that learning tasks are interesting, engaging, and accessible; they should be

geared towards improving students’ “essential” skills and understandings

• Design assignments with flexible procedures, evaluation tools, degrees of complexity,

and means of expression

• Encourage students to demonstrate conceptual mastery, based on learning styles

• Give varied opportunities for students to read and write reports on preferred books

• Invite visual learners to create graphic organizers to depict elements of self-selected

texts

• Urge auditory learners to complete oral accounts of favourite stories

21 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

• Provide openings for kinesthetic learners to construct dioramas that illustrate “special”

books (Hall et al., 2004; Heacox & Strickland, 2012; MBGS Understanding & Guiding

Behaviour: A Resource for Schools; Tomlinson, 1999, 2000a).

Learning Environment (Affect) [How students feel in class]

The learning environment refers to the routines, physical organization, and “climate” of the

educational space. Supportive, stimulating spaces reflect a belief that a student’s IQ is not a

static entity (Hattie, 2012). Given the brain’s innate “plasticity,” intelligence can “ebb and flow”

depending on the quality of the learning context; if conditions are ideal, the flame of curiosity

will be ignited, not attenuated. Strong teacher-student relationships are also central to a positive

learning experience (Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015). Without the security of “trusting” classrooms,

attuned to student idiosyncrasies, differentiating content, process, and product is more difficult

to accomplish; the desired academic outcomes may be stalled (The Iris Center, 2021; Tomlinson,

2003; Tomlinson, & Moon, 2013). To “reach and teach” everyone and build success, Maple Bear

teachers must create productive, structured, pliable, “invitational” learning settings (Hattie,

2012; MBGS Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools; Tomlinson & Moon,

2013). Different types of furniture and classroom arrangements can also be incorporated to

facilitate individual and small-group work (MB Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource

for Schools). For “real” learning to occur, the “feel” and functioning of the classroom count

(Manitoba Education & Training, 2015).

Examples of Differentiating the Learning Environment:

• Place some students into assigned groups to discuss common tasks

• Allow independent learners to work alone (if preferred)

• Create quiet zones in the classroom that are comfortable and distraction-free

• Incorporate a balance of teacher-assigned and student-selected activities

• Create collaborative areas in the room where students can work together quietly

• Develop tasks that are challenging, stimulating, and valuable

• Communicate clear guidelines for independent work (matched to needs)

• Offer culturally sensitive materials

• Generate motivating lessons that include student choice (lecture, discussion, practice)

• Provide materials that reflect a variety of home settings

• Design structured, predictable, student routines for solving problems, seeking help,

managing learning materials, and moving around the class, etc.

• Establish classroom conditions that set a respectful, non-judgemental tone

• Ensure that high expectations for learning are maintained

• Operationalize ongoing assessment protocols to drive instructional decision-making

(Hall et al., 2004; MBGS Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools; The

Iris Center, 2021; Tomlinson, 1995, 1999, 2000a).

It is important for teachers to observe and communicate with students as they undertake the

activities outlined above. “Successive approximations” of the targeted behaviours can be

reinforced or rectified immediately. To push learning even further, Maple Bear educators must

“tweak” their approaches to achieve closer alignment with students’ distinctive readiness,

interest, and learning profile characteristics.

22 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

(C) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Data Collection Measures

Differentiation is a cyclical process [assess, reflect, adjust] aimed at uncovering learners’

particular attributes (in three areas) and then responding appropriately to these variations.

Many pre-assessment tools are used to identify students’ readiness, interests, and learning

profiles. These tools can also spotlight particular misconceptions that students may harbour.

Without corrective feedback, progress and understanding will be hampered (Wiggins &

McTighe, 2005). The accumulated data also help teachers to make informed instructional

modifications to the content, process, product, and learning environment (Edugains, 2016b; Hall

et al., 2004). Thus, practical data collection systems must be seamlessly merged into “the daily

flow” of class routines (Lingo, Barton-Arwood, & Jolivette, 2011). Maple Bear teachers view this

step as a crucial starting point to ensure that students’ strengths and needs are addressed with

greater precision and effectiveness (MBGS Training Video: Cathy Gamble, 2021).

Figure 4. Learner Characteristics Guide Differentiation

DIFFERENTIATE

KNOW THE STUDENT RESPONSIVELY

Gather evidence about Adjust content, processes,

individuals' readiness, products & learning

interests & learning environments based on

profiles using multiple individuals' strengths &

assessment tools needs

Sources: Adapted from Doubet & Hockett, 2017; Edugains, 2016b; Heacox & Strickland, 2012; Wiggins & McTighe,

2005

23 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Readiness

Readiness refers to students’ knowledge and skills in relation to a specific curricular objective; it

is not the same as intellectual capacity or ability. Readiness levels are affected by an individual’s

background knowledge, experiences, and previous exposure to the topic. Hence, these levels can

seesaw markedly across subject areas (Tomlinson, 2014). Readiness differentiation is at work

when teachers present developmentally appropriate educational activities that are “in advance”

of children’s current stage of mastery (Zone of Proximal Development-ZPD, Vygotsky, 1978);

this means “raising the ceiling” for all students by supplying legitimate levels of scaffolding and

challenge. One tangible benefit is that they can directly connect their persistent efforts to

positive academic results (Byrdseed, 2009; Dweck, 2010; Utah State Board of Education &

Hanover Research, 2019). These tailored activities also help learners to bridge the gap between

dependence and independence.

The ZPD is defined as the distance between what students can do with and without assistance; it

is also known as “the sweet spot for learning” (Bell & Freeman, n.d.). Experts have indicated that

pinpointing “the student’s ZPD is of paramount importance if differentiated instruction is to

achieve its maximum impact” (Ontario Ministry of Education, Literacy & Numeracy Secretariat,

2008, p. 61). Therefore, it is imperative that appropriate supports and a viable route to success

are within reach; diluting content and lowering expectations are strongly discouraged (MBGS

Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools; Tomlinson, Moon, & Imbeau, 2015).

Maple Bear teachers grasp these realities and regularly “course-correct,” based on student

needs (Gregory & Kuzmich, 2014). They construct stimulating lessons that include choice and

varying degrees of complexity, but the learning targets remain essentially the same (EL

Education, 2021b; Hall et al., 2004; The Iris Center, 2021). Equitable access to educational

activities and resources is a consistent priority. Vygotsky’s findings suggest that exemplary

curriculum: (1) integrates “real-life” learning tasks into the classroom, and (2) provides ample

opportunity for students to “flex” both their cognitive and social muscles (Daniels, 2017).

Figure 5. Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development

24 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Sources: Adapted from EL Education, 2021b; Future Learn & National STEM Learning Centre, n.d.

Differentiating for Readiness

Planning for differentiation can be vastly simplified if practitioners begin by scrutinizing

students’ unique traits from many angles (assessment for learning) (Gregory & Kuzmich, 2014).

Reliable data- gathering mechanisms are a must. The use of pre-assessment (diagnostic) tools

allows teachers to anticipate how children will respond to new concepts and to make timely,

proactive plans. In short, these tools uncover students’ prior knowledge and experiences, reveal

each individual’s readiness level(s), and locate a suitable entry point for instruction (Chapman &

King, 2005; Edugains, 2016b). Other basic differences may also be unveiled: abilities,

motivations, interests, emotions and desires, multiple intelligences, attitudes toward topics, and

“hidden” talents (Chapman & King, 2005).

Teachers may choose to: assemble observational evidence (carousel or brainstorming activity);

analyze (in)formal test results (i.e., standardized test, unit pretest); review academic records;

check work samples; administer student self-audit measures; or ask the class to complete KWL

charts, graphic organizers, interviews, checklists, inventories, surveys, questionnaires, or

anticipation guides (Edugains, 2016b; Gregory & Chapman, 2012; The Iris Center, 2021). It is

vital that a variety of up-to-date information is assembled to inform and streamline classroom

management, curricular decision-making, and instructional approaches (Chapman & King,

2005). Readiness-based differentiation is highly malleable; it may include calculated changes in

scaffolding and challenge, task sophistication, tiering arrangements and organizational

structures, (in)dependent learning expectations, teacher-peer coaching, student (sub)groupings,

and lesson pacing (Doubet & Hockett, 2017; Edugains, 2016b; EL Education, 2021b; Gregory &

Chapman, 2012; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015). The notion of a “growth mindset” is at play here

once again (Tomlinson, & Moon, 2013).

Interests

Interest refers to any number of skills, activities, and themes that students view as captivating

and personally relevant. Once interest-based formative assessments are complete and

compelling topics are identified, teachers are able to establish starting points and orient

instruction or arrange groupings, in ways that excite and motivate learners (Doubet & Hockett,

2017; Edugains, 2016b; Tomlinson, Moon, & Imbeau, 2015; Utah State Board of Education &

Hanover Research, 2019). When curiosity is piqued, students are far more likely to engage

meaningfully with new, more difficult content and attain their learning goals (The Iris Center,

2021). Carefully selected curricular subjects, matched to student interests and values, also have

the power to dramatically accelerate progress, engross reluctant learners, improve behaviour,

increase independence, and steer students towards academic excellence (Heacox & Strickland,

2012; MBGS Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools; Tomlinson & Moon,

2013).

25 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

When Maple Bear teachers tap into students’ interests, they can more readily set strategic goals,

implement approaches that are responsive to their diverse needs, and provide opportunities for

individuals to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding (MBGS Planning for Students

with Special Needs). Similarly, teachers recognize that meaningful learning ensues when novel

ideas are connected to concepts that are already familiar to the class (Bartlett, 1932; Rumelhart,

1980 – Schema Theory).

Differentiating for Interests

To fully address learner diversity, inclusive-minded practitioners make ongoing, intentional

adjustments to their instructional and assessment activities. Early in the year, teachers typically

build a detailed “educational portrait” for each student, to aid in their pedagogical decision-

making (Manitoba Education & Advanced Learning, 2015); these portraits change over time as

students evolve and mature. Attending to individual interests, for example, is one of the key

determinants of student success (Hall et al., 2004; Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). Maple Bear

educators use this information to design engaging, “meaning-rich” programming that

harmonizes with the identified learner dimensions (strengths, cultures, prior experiences, etc.).

The goal of interest differentiation is to help students: (1) invest more time in their learning, (2)

“see themselves in the curriculum,” and (3) persevere when “the going gets tough” (Tomlinson

& Moon, 2013). Numerous differentiated data-collection instruments can be deployed for

planning purposes; a large repertoire of possibilities is available to classroom teachers: assistive

technology tools, anchor activities, interest inventories, the RAFT writing strategy, partner

introductions, Jigsaws, surveys, real-life/authentic assessments, ice breakers, small (expert)

groups, independent studies, open-ended questions, and interest stations (Strickland, 2007;

Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). Several of these techniques can also be used to explore students’

learning profiles.

Learning Profiles

Learning profile refers to the factors that affect how individuals: (1) absorb information; (2)

process, retain, and engage with content; and (3) demonstrate acquired knowledge and skills

(Sousa & Tomlinson, 2018; Tomlinson & Moon, 2013); student profiles are shaped by four

interrelated features (Tomlinson, 2004). These include learning styles, gender, culture, and

intelligence preferences. Thus, Maple Bear teachers believe that learning-profile differentiation

is an essential ingredient for teaching in ways that are proficient, meaningful, and effective

(MBGS Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools). They understand that any

classroom presents with a range of dynamic profile features; a mismatch between individuals’

learning tendencies and the delivery of instruction can hinder achievement (EL Education,

2021c; Sousa & Tomlinson, 2018). Helping students to discover what approaches and conditions

work best for them is also a key focus (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). To capture a personalized

snapshot of learner traits, teachers may choose to generate student profiles and class profiles

(Edugains, 2016b). These types of informal assessments serve a dual purpose; they act as a

“referencing” tool for planning subsequent lessons and as a tracking tool for checking progress

(Gregory & Kuzmich, 2014).

26 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Figure 6. Learning Preferences Continuum Assessment Chart

Conformity Creativity

Part-to-Whole Whole-to-Part

Competition Collaboration

On-Demand Response Reflective Response

Written Expression Multi-Modal Expression

Work Independently Work Together

Still or Silence Movement or Sound

Controlled Expressive

Concrete Abstract

Analytical Practical

Source: Adapted from Sousa & Tomlinson, 2018

Differentiating for Learning Profiles:

Differentiated instruction makes it easier for educators to reach all learners; wise interpretation

of “profile” data provides an invaluable lens for planning and presenting customized educational

activities (Heacox & Strickland, 2012). However, there is little benefit to affixing rigid labels to

students; most individuals respond quite readily to a variety of teaching and learning

approaches (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2018). By exposing students to a menu of differentiated

options, they are able to extend their learning repertoires and apply newly acquired strategies

more capably, across subject areas. To promote greater success, teachers might choose to:

(1) present material in visual, auditory, and kinesthetic modalities; (2) select exemplars,

applications, and images from a broad range of cultures, communities, and intelligences

(Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences); (3) employ “whole-to-part” and “part-to-whole” instructional

modes; (4) introduce “wait time” as a means to facilitate reflection; (5) engineer tasks that

enable participation and the sharing of diverse opinions; (6) arrange opportunities for students

to collaborate with peers (pairs, small groups); (7) develop flexible projects that permit

students to express their knowledge in different ways; (8) build assignments that have “real-

world” applications [problem-based learning]; (9) reconfigure the learning space to

accommodate identified preferences; and (10) invite students to brainstorm classroom

“climate” expectations, that affirm the notions of respect, acceptance, equity, safety, belonging,

and awareness of self and others (Edugains, 2016b; Sousa & Tomlinson, 2018; Strickland, 2007;

Tomlinson & Strickland, 2005).

(D) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Backward Design Framework

Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. has developed a continuum of effective supports to facilitate

learning for all students; the continuum is represented in the Three-Tiered Pyramid Model. As

noted earlier, this model is based on research tied to inclusion, differentiated instruction and

assessment, UDL, individual and classroom profiles, learning strategies, teamwork and

collaboration, and backward design (MBGS Planning for Students with Special Needs; MBGS

Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools).

27 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Sousa and Tomlinson (2011) suggest that If teachers expect students to apply their skills

prudently, memorization is an undependable way to realize that objective. Individuals often fail

to internalize information that is “drilled into their brains,” through rote recall (“superficial or

surface learning”). Students are also less likely to consistently connect, apply, or transfer any

“new knowledge” that they do not fully comprehend (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2011). The backward

design framework provides a viable path forward.

Figure 7. Stages of Backward Design

1. Identify Desired

• Big Ideas & Skills

Results

2. Establish • Culminating Assessment

Acceptable Activities

Evidence

3. Plan Learning

• Academic

Experiences &

Tasks

Instruction

Source: Adapted from Wiggins & McTighe, 2005

Backward design is not a teaching philosophy or approach; it is a flexible planning framework,

that places learning outcomes at the forefront. At its essence, backward design is a handy, goal-

oriented, curriculum development roadmap. The framework’s overarching idea of “beginning

with the end in mind” drives the structuring of curriculum, instruction, and assessment

(Wiggins & McTIghe, 2005). Inquiry-based planning is recommended; this means setting up

opportunities for students to read, experiment, research, discuss, debate, and construct

meaning, by zeroing in on the “essential questions” or “big ideas” contained in the unit or lesson

(Brownlie & Schnellert, 2009; Edugains, 2016b; McTighe & Wiggins, 2011). In differentiated

classrooms, teachers also ensure that all learners are exploring the same “essential” ideas or

core concepts; responsive layers of challenge and scaffolding are added to support each

individual’s developmental stage (Tomlinson & Moon, 2013). Thus, students can access the

curriculum in various ways and demonstrate their learning through multiple avenues of

representation (Edugains, 2016b; McTighe & Wiggins, 2011).

28 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Wiggins and McTighe (2005) offer a sequence of questions to support teachers’ decision-making

as they move through this process: (1) What do I want students to learn? (2) How will I know

they are learning? (3) How will I design instruction-assessment tasks to enhance learning? and

(4) What will I do when students are not learning?

Three Stages of Backward Design

The backward design framework includes three critical stages: (1) identify desired outcomes

(2) determine acceptable evidence; and (3) plan learning experiences and instruction. For each

of these steps, there are benchmarks to help guide design procedures. Nimble educational

professionals are able to use this straightforward, three-phase planning tool to underline clear

goals and expectations, connect learning tasks to the chosen outcomes, and gauge progress with

reliable success criteria (Doubet & Hockett, 2017; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015).

Figure 8. Lesson & Unit Planning Sequence: Stages 1 – 3

Stage 1: Identify Desired Results

- Identify learning goals & priorities

- Study content standards

- Review overarching curricular expectations

- Emphasize “big ideas” (core concepts)

Questions:

1. What should students know, understand & be able to

do?

2. What content is worthy of understanding?

3. What “enduring understandings” are sought?

Stage 2: Determine Acceptable Evidence

- “Think like an assessor” before designing

units/lessons

- Develop assessment criteria for each learning

goal

- Select formative & summative assessment tools

Questions:

1. How will I know if students achieve the desired

result?

2. What is suitable proof of understanding &

proficiency?

* It’s not about covering content & doing many

activities.

29 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

Continuum of Assessment Tools

Continuum activities differ in scope (simple to complex), duration (short- to long-term), setting

(decontextualized to authentic contexts), and form (from high- to non-structured). “Assessment for

understanding” is a data-gathering process, unfolding over time (not one test at the end of the unit).

Stage 3: Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction

- Plan with “the end in mind” (activities align with goals & assessment)

- Activate prior knowledge to maximize engagement

- Differentiate lesson sequence for successful completion of tasks

- Choose effective strategies, structures & processes for teaching, practice, feedback & self-audits

- Prepare students to experience & explore key ideas

- Tailor tasks & assessments to readiness, interests & profiles (to drive progress & next steps)

Questions:

1. What enabling knowledge (facts, concepts, principles) will students need to achieve the desired

results?

2. What enabling skills (processes, procedures, strategies) will students need to perform

effectively?

2. What differentiated activities will equip students with the key background knowledge & skills for

success?

3. What concepts will need to be taught, practised & re-taught?

5. What adaptive materials & resources are best suited to accomplish the target goals?

Sources: Adapted from Bowen, 2017; Heacox & Strickland, 2012; Wiggins & McTighe, 2002, 2004, 2005

Final Note About Backward Design:

Enhanced learning tends to occur if it is grounded in a limited number of “core concepts”

(Brownlie & Schnellert, 2009). Therefore, pedagogical decisions about methods, lesson

sequencing, and resource materials can be made more effectively, once educators understand

that “teaching is a means to an end.” Without a crystal-clear understanding of key learning

objectives and “good” assessment evidence and practices, it is much more difficult to proceed

with differentiated planning (Wiggins & McTighe, 2002). Throughout the learning process, we

must ensure that instructional-assessment methods correspond with the targeted knowledge,

skills, and lesson expectations (Edugains, 2016b).

30 All Rights Reserved - Maple Bear Global Schools Ltd. (2021)

Maple Bear Global Schools

Responsive Differentiated Instruction

Best Practices Handbook

(E) Planning for Differentiated Instruction: Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Given the unique nature of students in multi-dimensional classrooms, teachers must find novel

ways to reshape curriculum, tailor instructional delivery methods, and orchestrate assessment

procedures that allow all learners to be exposed to the same content and reach reasonable

levels of mastery of topics and skills. Ensuring that students are “firing on all cylinders” is not

easy, but it is achievable; Universal Design for Learning (UDL) offers a feasible solution.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a theoretical “blueprint” that is intended to guide the

design and development of educational environments, that accelerate growth and minimize

school barriers (Hall et al., 2004; Rose & Meyer, 2002; Thousand et al., 2014; UDL-IRN, 2020). It

is not an “add-on.” Rather, UDL-based planning involves the creation of curricular, instructional,

and assessment activities that are responsive to a potpourri of individual preferences and

challenges. Students of all stripes can reap the benefits.

UDL also stresses the idea of “beginning with the end in mind.” Backward design and UDL work

in tandem and intersect with the Three-Tiered Pyramid Model (MBGS Planning for Students with

Special Needs; MB Understanding & Guiding Behaviour: A Resource for Schools). This fusion of

foundational concepts serves as a “pedagogical anchor;” it is also compatible with Maple Bear’s

overarching commitment to crafting and implementing exemplary programs, maintaining high

expectations, and providing equal access for a full spectrum of students (MBGS Global Schools

Quality Assurance Handbook, 2021). MBGS teachers understand that UDL is one of the main

building blocks in lesson development and inclusion is the centrepiece.

UDL Principles & Guidelines

Unlike a retrofitted teaching process, which begins after lessons are underway and learning

problems arise, the UDL framework equips educators with a set of anticipatory “lenses” that can

be used to diversify educational goals, methods, materials, and assessments, at the outset

(Doubet & Hockett. 2017; Thousand et al., 2014). When used judiciously, UDL is a powerful

vehicle for strengthening decision-making and boosting success for a wider array of students

(CAST, 2021; Rose & Meyer, 2002). Thus, the development of “expert learners” can be facilitated

if teachers adhere to the suggested UDL principles (Gargiulo & Metcalf, 2017). More recently,

these principles have been supplemented with a set of additional recommendations: The

Universal Design for Learning Guidelines (Rose, Meyer, & Gordon, 2014). These versatile design