Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Refiguring The Father

Refiguring The Father

Uploaded by

LinjiayiCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Gender by Jutta BurggrafDocument8 pagesGender by Jutta BurggrafRobert Z. CortesNo ratings yet

- Sedgwick 3AA3 RevDocument20 pagesSedgwick 3AA3 RevSNasc FabioNo ratings yet

- Karen Horney and FeminismDocument21 pagesKaren Horney and FeminismSimina ZavelcãNo ratings yet

- Examples of Positive Language PDFDocument2 pagesExamples of Positive Language PDFkalpesh100% (2)

- Femininities, Masculinities, Sexualities: Freud and BeyondFrom EverandFemininities, Masculinities, Sexualities: Freud and BeyondRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Lynne Layton (1998) Gender StudiesDocument11 pagesLynne Layton (1998) Gender StudiesatelierimkellerNo ratings yet

- Gender and Sexuality EssayDocument13 pagesGender and Sexuality EssayDestiny EchemunorNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalytic FeminismDocument6 pagesPsychoanalytic FeminismNithika DamodaranNo ratings yet

- Zotzi 3Document4 pagesZotzi 3Evangelist Kabaso SydneyNo ratings yet

- Gender or Sexual Identity TheoriesDocument5 pagesGender or Sexual Identity TheoriesJV Bryan Singson Idol (Jamchanat Kuatraniyasakul)No ratings yet

- Lennon - Gender and KnowledgeDocument12 pagesLennon - Gender and KnowledgeEmilseKejnerNo ratings yet

- Critical Femininities A New Approach To Gender TheoryDocument9 pagesCritical Femininities A New Approach To Gender Theoryzhoujinjia0724No ratings yet

- Genderchapter RutherfordDocument43 pagesGenderchapter Rutherfordbron sonNo ratings yet

- Saintly Influence: Edith Wyschogrod and the Possibilities of Philosophy of ReligionFrom EverandSaintly Influence: Edith Wyschogrod and the Possibilities of Philosophy of ReligionNo ratings yet

- Juliet Mitchell. Psychoanalysis and FeminismDocument11 pagesJuliet Mitchell. Psychoanalysis and FeminismScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- WWW Iep Utm EduDocument10 pagesWWW Iep Utm EduWawan WibisonoNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism and Gender Relations in Feminist TheoryDocument24 pagesPostmodernism and Gender Relations in Feminist Theorypanos stebNo ratings yet

- Davis, Jena - Beyond Castration, Recognizing Female Desire and Subjectivity in The Oedipus Complex - TEZADocument73 pagesDavis, Jena - Beyond Castration, Recognizing Female Desire and Subjectivity in The Oedipus Complex - TEZATiberiu SNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalytic Feminism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Document26 pagesPsychoanalytic Feminism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)janhavi poddarNo ratings yet

- Conway IntroductionConceptGender 1987Document11 pagesConway IntroductionConceptGender 1987puneya sachdevaNo ratings yet

- "Entering Boys' World" Relational MasculinitiesDocument5 pages"Entering Boys' World" Relational Masculinitiescagedo5892No ratings yet

- Social Construction of GenderDocument11 pagesSocial Construction of GenderKumar Gaurav100% (2)

- Gender StudiesDocument6 pagesGender StudiesElena ȚăpeanNo ratings yet

- Freud and Revolutionary Spirit in 20th Century ChinaDocument13 pagesFreud and Revolutionary Spirit in 20th Century ChinaYuri YuNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Queer TheoryDocument25 pagesUnit 1 Queer TheorypreitylaishramNo ratings yet

- Andrea Dworkin and The Social ConstructionDocument32 pagesAndrea Dworkin and The Social ConstructionXmahannahNo ratings yet

- R Kukla DECENTERING WOMEN PDFDocument26 pagesR Kukla DECENTERING WOMEN PDFDilek ZehraNo ratings yet

- Feminist Standpoint Theory - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyDocument17 pagesFeminist Standpoint Theory - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophySESNo ratings yet

- ArticleText 322348 1 10 20181202Document9 pagesArticleText 322348 1 10 20181202Myra CasapaoNo ratings yet

- Lindquist GENDER 2012Document19 pagesLindquist GENDER 2012Cliff CoutinhoNo ratings yet

- UGGS - Palina Samathuvam1Document14 pagesUGGS - Palina Samathuvam1selvakumar.uNo ratings yet

- Glligan,: Social SelfDocument1 pageGlligan,: Social SelfAikido EurogetNo ratings yet

- Mapping The Middle Way Thoughts On A Buddhist Contribution To A Feminist DiscussionDocument23 pagesMapping The Middle Way Thoughts On A Buddhist Contribution To A Feminist DiscussionGigapedia GigaNo ratings yet

- Book Review: Looking at Siblings Is Looking Anew at Sex and ViolenceDocument5 pagesBook Review: Looking at Siblings Is Looking Anew at Sex and ViolenceCagil Metin BalcıNo ratings yet

- Alterity-Marginality-Difference: On Inventing Places For WomenDocument12 pagesAlterity-Marginality-Difference: On Inventing Places For WomenDELHERBE PÉREZ DISARNo ratings yet

- Royal Institute of International Affairs, Oxford University Press International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)Document19 pagesRoyal Institute of International Affairs, Oxford University Press International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)selormmensah84No ratings yet

- fiminism عياداتDocument7 pagesfiminism عياداتalkhalidiNo ratings yet

- Dumont 2008Document236 pagesDumont 2008DZCunuckNo ratings yet

- Feminist Critique of ScienceDocument16 pagesFeminist Critique of ScienceZikra MehjabinNo ratings yet

- Root of Women's Oppression/SubordinationDocument8 pagesRoot of Women's Oppression/SubordinationPrincess Janine SyNo ratings yet

- Weldon (2008) - LntersectionalityDocument14 pagesWeldon (2008) - Lntersectionalityangielo_bNo ratings yet

- Cap29-Feminist Standpoint TheoryDocument17 pagesCap29-Feminist Standpoint TheoryJessica Diaz GuadalupeNo ratings yet

- Feminist Standpoint TheoryDocument7 pagesFeminist Standpoint TheoryClancy Ratliff100% (1)

- Abbey Blog TwoDocument4 pagesAbbey Blog Twoapi-264972710No ratings yet

- In Search of Feminist EpistemologyDocument14 pagesIn Search of Feminist EpistemologyMichele BonoteNo ratings yet

- Gender Identity and PsychoanalysisDocument18 pagesGender Identity and PsychoanalysisDim AsNo ratings yet

- Feminism Is Not MonolithicDocument6 pagesFeminism Is Not MonolithicMavis RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 34 Standpoint Theory Presentation Elizabeth HeffnerDocument22 pagesChapter 34 Standpoint Theory Presentation Elizabeth Heffnerbmharvey100% (2)

- Gender Theory SummaryDocument10 pagesGender Theory SummaryDanar CristantoNo ratings yet

- Humana - Mente 22 Gender, Sex, Race, and The FamilyDocument270 pagesHumana - Mente 22 Gender, Sex, Race, and The FamilyambientiNo ratings yet

- Feminist Theory and Research1 PDFDocument19 pagesFeminist Theory and Research1 PDFআলটাফ হুছেইনNo ratings yet

- Queer TheoryDocument17 pagesQueer TheoryRoger Salvador100% (4)

- Dorothy Smith - The Everyday World As ProblematicDocument253 pagesDorothy Smith - The Everyday World As Problematicrffhr5fbpmNo ratings yet

- Sy BookReview CynthiaWeberDocument5 pagesSy BookReview CynthiaWeberjulia pioNo ratings yet

- Psychology and Freudian Sexual Theory in Early 20th Century ChinaDocument47 pagesPsychology and Freudian Sexual Theory in Early 20th Century ChinaYuri YuNo ratings yet

- Queer Theory: A Rough Introduction: DifferencesDocument3 pagesQueer Theory: A Rough Introduction: DifferencesmikiNo ratings yet

- Queer Theory: A Rough Introduction: DifferencesDocument4 pagesQueer Theory: A Rough Introduction: Differencessaqlain3210100% (1)

- The Process of Socialization Sociology Reference GuideDocument197 pagesThe Process of Socialization Sociology Reference Guiderosc8160% (5)

- Chapter 6 FeminismDocument20 pagesChapter 6 FeminismatelierimkellerNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 193.219.130.166 On Tue, 12 Oct 2021 10:40:58 UTCDocument29 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 193.219.130.166 On Tue, 12 Oct 2021 10:40:58 UTCIeva PaukštėNo ratings yet

- Case Study 148 169Document22 pagesCase Study 148 169Vonn GuintoNo ratings yet

- My First 10 Years ProjectDocument2 pagesMy First 10 Years ProjectahdyalNo ratings yet

- SeminarDocument29 pagesSeminarAkash shindeNo ratings yet

- CA Level 1Document43 pagesCA Level 1Cikya ComelNo ratings yet

- UPNMG Press Statement-Unemployed Nurses and MidwivesDocument1 pageUPNMG Press Statement-Unemployed Nurses and MidwivesClavia NyaabaNo ratings yet

- Change Order - Rev2 - 44873036-001Document5 pagesChange Order - Rev2 - 44873036-001Hugo MoralesNo ratings yet

- Ceramic Resonator - Ceralock - 312547Document43 pagesCeramic Resonator - Ceralock - 312547wayan.wandira8122No ratings yet

- The Role of Goverment in Ecotourism DevelopementDocument10 pagesThe Role of Goverment in Ecotourism DevelopementYunita MariaNo ratings yet

- Genetic Mutation LAB SHEET REVISEDDocument2 pagesGenetic Mutation LAB SHEET REVISEDyusufoyololaNo ratings yet

- Ede Micro Project For Tyco StudentsDocument10 pagesEde Micro Project For Tyco StudentsAditya YadavNo ratings yet

- Types of ShoringDocument9 pagesTypes of ShoringAzil14100% (10)

- ASX Announcement 2021 23 - CRU Conference PresentationDocument26 pagesASX Announcement 2021 23 - CRU Conference PresentationÂngelo PereiraNo ratings yet

- Advt 2013 Ver 3Document6 pagesAdvt 2013 Ver 3mukesh_mlbNo ratings yet

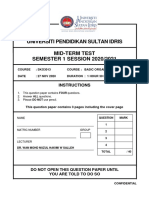

- Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris Mid-Term Test SEMESTER 1 SESSION 2020/2021Document3 pagesUniversiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris Mid-Term Test SEMESTER 1 SESSION 2020/2021rusnah chungNo ratings yet

- Nynas Transformer Oil - Nytro 10GBN: Naphthenics Product Data SheetDocument1 pageNynas Transformer Oil - Nytro 10GBN: Naphthenics Product Data SheetAnonymous S29FwnFNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Being Bilingual Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesBenefits of Being Bilingual Lesson PlanCristina BoantaNo ratings yet

- Masterclass ReflectionDocument3 pagesMasterclass Reflectionapi-537874530No ratings yet

- En SATURNevo ZGS.10.20 User Manual 13Document1 pageEn SATURNevo ZGS.10.20 User Manual 13emadsafy20002239No ratings yet

- Syllabus For Applied ElectronicsDocument28 pagesSyllabus For Applied ElectronicsvinayakbondNo ratings yet

- Air Equipment Compressors Compressor 250 300CFM D XAS 125DD Operation ManualDocument34 pagesAir Equipment Compressors Compressor 250 300CFM D XAS 125DD Operation ManualFloyd MG100% (1)

- Cut Out ValveDocument64 pagesCut Out ValveHoang L A TuanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 03 - Louwers 5eDocument23 pagesChapter 03 - Louwers 5eMonique GordonNo ratings yet

- Hazcom ToolsDocument25 pagesHazcom ToolsAbdul hayeeNo ratings yet

- Rw15 ManualDocument314 pagesRw15 ManualpedrogerardohjNo ratings yet

- Classroom Management: Chapter 4 Richards/Renandya Methodology in Language Teaching. (Marilyn Lewis)Document4 pagesClassroom Management: Chapter 4 Richards/Renandya Methodology in Language Teaching. (Marilyn Lewis)Florencia CorenaNo ratings yet

- Moxon Sat AntDocument4 pagesMoxon Sat AntMaureen PegusNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Classroom Assessment PracticesDocument12 pagesTeachers' Classroom Assessment PracticesDaniel BarnesNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - Event Driven ProgrammingDocument22 pagesUnit 5 - Event Driven ProgrammingdharanyaNo ratings yet

- Quiz 01, MTH-501Document9 pagesQuiz 01, MTH-501Shining_900% (1)

Refiguring The Father

Refiguring The Father

Uploaded by

LinjiayiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Refiguring The Father

Refiguring The Father

Uploaded by

LinjiayiCopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Reviewed Work(s): Feminism and Psychoanalytic Theory by Nancy J. Chodorow:

Postmodernism in the Contemporary West by Jane Flax: Refiguring the Father: New

Feminist Readings of Patriarchy by Patricia Yaeger and Beth Kowaleski-Wallace

Review by: Ruth Perry

Source: Signs , Spring, 1991, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring, 1991), pp. 597-603

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3174592

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Signs

This content downloaded from

202.116.205.75 on Tue, 13 Dec 2022 00:57:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BOOK REVIEWS

Feminism and Psychoanalytic Theory. By NANCY J. CHODOROW.

Yale University Press, 1989.

Postmodernism in the Coittee,por-a-y West. By JANE FLAX. Berkele

University of California Press, 1989.

Refiguring the rather: New Feminist Readings of Patriarchy. Edite

YAEGER and BETH KOWALESKI-WALLACE. Carbondale: Southern Illinois U

1989.

Ruth Perry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

How is human identity constructed in different cultural contexts?

How do bodies come to have the meanings they have? How are

women and men socialized to think and feel and act, and how do

these cultural expectations fit into larger political and economic

structures? Questions like these, posed by feminist intellectuals for

the past twenty years, lately have been catching on in more

fashionable academic discourses such as "cultural studies" and

"new historicism." Ever since Simone de Beauvoir observed that

women are made and not born, and Betty Friedan noted the "click"

that went off in women's minds when they registered their deval-

uation as women, feminist intellectuals have been asking how

gender is constructed and perpetuated.

Nancy Chodorow made her original contribution to a theory of

gender difference remarkably early in the process, working with

Freudian theory and cultural anthropology. Building on Freud's

perception (elaborated by object-relations theorists such as D. W.

Winnicott and Melanie Klein) that female psychosexual identity

was formed in an earlier developmental sequence than that postu-

lated for male Oedipal conflict and resolution, Chodorow reimag-

ined the steps that led to female identity formation. She then

generalized her theory of how gendered subjects-boys and girls-

are produced, not on the basis of anatomical distinctions between

Permission to reprint a book review printed in this section may be obtained only from the author.

597

This content downloaded from

202.116.205.75 on Tue, 13 Dec 2022 00:57:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Book Reviews

the sexes, as Freud would have it, but on the basis of cross-cultural

data that women everywhere are the primary caretakers of children

of both sexes.

I remember vividly my own introduction to Chodorow in 1973,

when someone in my Cambridge women's group brought to our

attention "Family Structure and Feminine Personality," one of

Chodorow's graduate student papers written the year before at

Brandeis. I read it with growing excitement: here, at last, was a

rewriting of Freud's script for women's psychosexual development.

No longer did one have to struggle skeptically with the tortured

theory of the female Oedipus, whether "penis envy" or the difficult

and crippling transition from the clitoral to vaginal genital orienta-

tion. Chodorow, a year or two younger than we were, had explained

how women's universal role as the caretaker of children set in train

a process by which those children grew into their gendered

identities as boys and girls, men and women. Her theory located

difference in social process, not biology. Starting with women's

universal social role as mothers, Chodorow derived an explanation

for the "reproduction of mothering"-that is, how girl children are

conditioned to take responsibility for child rearing and other forms

of human intimacy and to define themselves as "relational" beings.

She suggested that the universal female backdrop to childhood

development had different consequences for girls than it did for

boys.

This early paper is reprinted in Feminism and Psychoanalytic

Theory, along with other Chodorow essays published between

1972 and 1990 on subjects such as personality formation, psycho-

analytic theories of difference, and psychoanalytic practice. The

collection documents Chodorow's twenty-year dialogue with psy-

choanalysis. For her, psychoanalysis is first and foremost a theory of

the construction of heterosexuality-of femininity and masculinity

as they are conventionally understood. For others, psychoanalysis

has been a theory of childhood sexuality, or a theory about the

operations of the unconscious, or a theory about psychic structure-

the economy of id, ego, and superego. But what Chodorow credits

to Freud is providing "an account of the genesis of psychological

aspects of gender and sexuality in their social context" (170). Her

readings of Freud redirect attention from the body-its anatomy

and drives-to perceptions about the self in relation to other selves.

The chapters take up various aspects of the difference gender

makes in psychoanalytic theory and practice: the professional

debate, for example, about boys' and girls' perceptions of their

genitals; the problem of asymmetrical cross-gender countertrans-

ference (the way male analysts may be "less likely to recognize

598

This content downloaded from

202.116.205.75 on Tue, 13 Dec 2022 00:57:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Spring 1991 / SIGNS

maternal transference [from older women patients] whereas they

easily recognize an erotic transference from a younger woman"

[183]); the intellectual differences among feminist psychoanalytic

theorists-Jean Baker Miller, Jane Flax, Jessica Benjamin-or be-

tween object-relations theorists and Lacanians. Her writing in

these essays is exemplary social science writing (unlike her con-

gested Reproduction of Mothering). It has the strange colorlessness

of all social science writing, but there is a satisfying accuracy in the

verbs positioning the ideas, indicating the relations among them.

There is no backing off from what she has to say, no wasted motion,

no feints or hedging. Her quiet clarity is comforting.

Feminists with more activist political orientations tend to get

irritated by what they consider to be "trivial" about psychoanalytic

approaches. Why study middle-class constructs such as individual-

ism, selfhood, relationships, or family dynamics rather than the

material facts of life, the brute forces that dominate the lives of the

disenfranchised: poverty, racism, and the unequal distribution of

power? Why read about Freud and object-relations theory when

real problems stalk the earth?

The reason is that the family is where one first experiences

social relations based on negotiated power; one's earliest political

realities are family power struggles. By exploring the primal

experience of growing up in a family, psychoanalytic theory can

account for the construction and "tenacity of people's commitment

to our social organization of sex and gender" (171), how a culturally

constructed sex/gender system takes hold in the unconscious,

showing itself in intractable emotional responses or retrograde

erotic fantasies that no amount of rational analysis can eradicate.

Chodorow has also come in for criticism, along with other white

middle-class academics of her generation, for "essentializing" the

experience of women-for not taking into account the ways in

which class, race, and ethnicity complicate models of difference

and for not facing up to the problem of theorizing about "Woman"

in a world with an astounding variety of women. In her introduction

to this collection, Chodorow indirectly responds to this charge by

noting that her early work reflects her "early training as a culture

and personality anthropologist" (15) (evident in references to

family structure in India, Kenya, Java, Atjeh [Indonesia], and

Morocco). On the other hand, she herself acknowledges that this

early work reflects "the early feminist search for universals and

single-cause theories of male dominance" (14-15).

In Chodorow's last chapter, "Seventies Questions for Thirties

Women," these political issues take an unexpected turn. Reading

the results of a study Chodorow began in 1984 in which she

599

This content downloaded from

202.116.205.75 on Tue, 13 Dec 2022 00:57:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Book Reviews

interviewed leading women in the first generation of analysts, on

begins to see how the commitment of the "seventies" generation o

feminists to social change made the crucial difference in reinte

preting Freud. Asking "thirties" women how they felt about su

Freudian concepts as "penis envy," or why they thought so ma

women went into the psychoanalytic profession, Chodorow learned

that this earlier generation of women analysts believed that

gender differences they perceived were natural, innate, and immu

table. They did not challenge the gendered division of labor in

family or investigate the perpetuation of male-dominant soc

organization. Interested in reconstructing gender relations, n

simply fine-tuning them to the existing society, Chodorow saw th

implications for social change in Freud's theory of how the psycho

logical is constructed by the social. If the social arrangements t

relegated all child rearing to women could be altered, the psych

logical processes creating gender identity as we know it, she

suggested, might also be altered.

Formatted as questions and answers so as to present the re

sponses of pioneering women psychoanalysts in their own wor

this chapter also makes the point that gender was not so salient

that earlier generation of women as to Chodorow's own. For

thing, quite a number of women participated in the early psyc

analytic movement relative to other professional circles, and th

gave it a more egalitarian feel. Then, too, Europeans accept

intellectual women as intellectuals; it was not until they came

the United States that they were dismissed as women. Severa

her respondents remarked that "they did not notice the phallocen

tricism of the theory until they were in the context of a sex

culture" (210). Chodorow also conjectures that other social

categorizations-such as that of European Jew in the context of

World War II-made gender less significant in these women's lives.

The recognition that gender is not always the dominant identity

factor in relation to other social factors is a significant move in

feminist theory at present because it creates the conceptual space to

examine the intersections of gender with other social factors such as

race or class.

While Chodorow's essays document her feminist interrogation

of psychoanalytic theory and practice over the past twenty years,

Jane Flax's book examines the work of about a dozen theorists-

including Chodorow-who together constitute the postmodern

critique of Enlightenment subjectivity and epistemology. Accord-

ing to Flax, the collapse of Enlightenment certainties about the

nature of personhood, rational and irrational sources of knowledge,

objectivity, and the uses of instrumental reason have left a gulf, into

600

This content downloaded from

202.116.205.75 on Tue, 13 Dec 2022 00:57:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Spring 1991 / SIGNS

which have rushed the waters of feminist theory, psychoanalytic

theory, and postmodern philosophy. Each of these streams has its

tributaries, Flax explains. Economic determinism, structural an-

thropology, and psychological theory supply feminist theory; psy-

choanalysis, since its source in Freud, has been fed by Winnicott

and Lacan; the wellsprings of postmodernism are to be found in

Derrida, Foucault, and, according to Flax, Lyotard and Rorty.

With diagrammatic clarity Flax details the contributions and

blind spots of these schools of thought. She wants practitioners

within each movement to pay attention to the others. She thinks

each orientation to reality insufficient by itself; each "unwittingly

provides reasons for and proof of the inadequacy of some of the

ideas it posits but cannot abandon" (225). Keenly aware of ambigu-

ity and contradiction, Flax is best known for having written about

one of the central ambiguities to evolve from Chodorow's paradigm

of the reproduction of mothering: the conflict between nurturance

and autonomy in mother-daughter relationships. Thinking Frag-

ments (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press,

1989) explains why psychoanalysis needs to take seriously the

realpolitik of gender-"the social origins of gender and gender-

based asymmetries of power" (105)-and why postmodern philos-

ophers (all white men, in her account) need to add the feminist

story line to their cultural narratives and women subjects to their

concepts of subjectivity before they "destabilize" the concept of

personhood. She asks feminists to recognize the profound change

in the philosophical bases of life in this postmodern era, the radical

uncertainty of what we know, the failure of rationality to increase

power, and the insufficiency of knowledge to bring greater freedom

or greater happiness.

Despite Flax's brilliant analysis of male bias in psychoanalytic

thought, this is in many ways a depressing book-another feminist

theorist paying respect to an intellectual establishment that re-

mains oblivious to feminist insight. Another feminist drawn off

course by the siren song of postmodern ambiguity, abandoning the

project of understanding how gender itself is constructed and how

it might be re-constructed.

Refiguring the Father, edited by Patricia Yaeger and Beth

Kowaleski-Wallace, is a collection of essays committed to the

combined feminist, psychoanalytic, and postmodernist methodol-

ogy that Flax recommends. A set of literary readings about the

representation of the father in texts from Euripides' Hippolytos to

Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye, this anthology draws heavily on

psychoanalytic and postmodern formulations to complicate femi-

nism's relation to the father. The introduction announces that it is

601

This content downloaded from

202.116.205.75 on Tue, 13 Dec 2022 00:57:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Book Reviews

time to stop homogenizing all fathers as "the patriarchy" and to sto

automatically identifying the father with disembodied authority

the law, the "gaze," the power that exchanges and represents women

and appropriates their sexual services to reproduce itself. We nee

to dismantle these formulations, say the editors, and to "invoke the

father's self-division and plurality" (xv). It should be added that we

need to compare these theoretical formulations to lived experience.

Indeed, Nancy Miller's afterword does just that, with its hilariou

(and familiar) evocation of her father in his string pajamas.

It is high time to particularize the way in which fathers have

been represented in our literary tradition, to analyze them with

more complicated grid, to work out the complexities of "authority,"

"the law," "the symbolic," and to ask how the category of the

paternal has been constituted by women. Adrienne Munich's "Law

of the Mother," for example, points out that Virgil portrays Aeneas's

father, Anchises, as a burden, while his mother, the immortal Venus,

with an anti-Oedipal gesture, seduces Vulcan so that he will forg

arms for her son. Gwin Montrose foregrounds the feminine within

the father by showing how Faulkner takes the daughter's subjec

position and thus is both father and daughter of his text.

Once feminists would have argued that it was counterproductive

to study the father. Wasn't the whole Western tradition already

about fathers? Wasn't it the feminist intellectual's task to fill in the

experiences, perceptions, and contributions of women? Yet so long

as fathers figure in women's lives, they need to be part of that

analysis. Fathers are definitely on the feminist intellectual agenda

just now. Last year another anthology on the subject was published,

containing a number of excellent essays.1

Not all the essays in Refiguring the Father are about fathers and

daughters, however; a number are about fathers and sons. In fact,

this collection represents a somewhat new mood in academic

feminism with regard to male participation, printing essays by male

scholars and treating male themes. Heather Hathaway's "Maybe

Freedom Lies in Hating," for example, treats white father/mulatto

son relations in the fiction of Charles Chesnutt and Langston

Hughes. Nancy Sorkin Robinowitz reads Hippolytos as a text in

which the mother is destroyed and the son is reunited with a loved

father. Joseph Boone scrutinizes certain feminist contentions about

Absalom, Absalom! and concludes that the Oedipal male is "a

vulnerable man caught in the middle of a story that he has indeed

helped create but cannot control" (232).

1 Daughters and Fathers, ed. Lynda E. Boose and Betty S. Flowers (Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989).

602

This content downloaded from

202.116.205.75 on Tue, 13 Dec 2022 00:57:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Spring 1991 / SIGNS

If

If Nancy

NancyChodorow

Chodorowdemonstrated

demonstrated thethe

centrality

centrality

of mothers

of mothers

in in

women's

women'srepresentation

representation ofof

themselves,

themselves,

directing

directing

us tousexamine

to examine

these

these relationships

relationshipsasas

well

well

as as

thethe

nature

nature

of women's

of women's

relationships

relationships

with

with other

otherwomen,

women,this this

newnew

work

workbidsbids

us pay

us pay

attention

attention

to fathers.

to fathers.

Completing

Completingananessentially

essentiallyFreudian

Freudianresearch

research

program,

program,

feminists

feminists

are are

investigating

investigatingallallthe

therelations

relations

of of

thethe

family:

family:

the the

father

father

as well

as as

well

theas the

mother,

mother,and andintra-generational

intra-generational as well

as wellas cross-generational

as cross-generationalrela- rela-

tionships.

tionships.Despite

Despitepostmodernist

postmodernist disclaimers

disclaimers aboutabout

the instability

the instability

and

and unknowability

unknowabilityofof the

theself,

self,

we we

stillstill

cannot

cannot

afford

afford

to explode

to explode

gender

gender asasaacategory

categoryofof analysis-not

analysis-notuntil until

it noitlonger

no longer

existsexists

as a as a

category

categoryof ofpolitical

politicaland

andeconomic

economicdiscrimination.

discrimination. And And

the family

the family

remains

remainsourourbest

bestguess

guessas as

to to

howhow thethe

culture

culture

constructs

constructs

and repro-

and repro-

duces

duces existing

existingforms

formsofof masculinity

masculinity andand

feminity,

feminity,

how how

it manages

it manages

sexual

sexual relations

relationswithin

within this

this

political

political

andand

economic

economicsystem.

system.

As family

As family

forms

forms change

changeandandour

ourculture

culture experiences

experiencesa wider

a wider

variety

variety

of child-

of child-

rearing

rearing practices,

practices,perhaps

perhaps wewewillwill

refine

refine

our our

understanding

understanding

of theof the

relationship

relationshipbetween

betweenfamily

family structure

structureandand

the the

particular

particular

formsforms

of of

gender

gender with

withwhich

whichwewe arearefamiliar

familiarin the

in the

late late

twentieth

twentieth

century.

century.

Toward

Toward aaFeminist

FeministTheory

Theoryof of

thethe

State.

State.

By CATHARINE

By CATHARINE

A. MACKINNON.

A. MACKINNON.

Cambridge,

Cambridge,

Mass.:

Mass.: Harvard

HarvardUniversity

UniversityPress,

Press,

1989.

1989.

Justice

Justice and

andGender.

Gender.ByBy

DEBORAH

DEBORAH

L. RHODE.

L. RHODE.

Cambridge,

Cambridge,

Mass.:Mass.:

Harvard

Harvard

University

University

Press, Press,

1989.

Carrie Menkel-Meadow, University of California, Los Angeles

How has law constructed "woman"? How has feminism changed

law? What contributions have legal feminism made to political

feminism and to feminist theory? Is a feminist theory of the state or

its rules of law possible? The authors of these books on legal

feminism take on these important questions, if somewhat obliquely.

MacKinnon's answers are crisp, radical, elegant, and eloquent, if

also dated, essentialist, and somewhat unsatisfying. Rhode's an-

swers are more textured, socially situated, contingent, measured,

and also somewhat unsatisfying. Read as historical documents,

these books capture both the exciting new theories (sexual harass-

ment, civil rights approaches to pornography) and the old ap-

proaches ("formal" versus "special" equality, the Equal Rights

Amendment) that have fueled the second wave of feminism in its

legal forms. But read as efforts to provide an organizing theoretical

structure for the role of law in modern feminism, both books fail to

transcend the current impasses in feminist legal theory.

603

This content downloaded from

202.116.205.75 on Tue, 13 Dec 2022 00:57:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Gender by Jutta BurggrafDocument8 pagesGender by Jutta BurggrafRobert Z. CortesNo ratings yet

- Sedgwick 3AA3 RevDocument20 pagesSedgwick 3AA3 RevSNasc FabioNo ratings yet

- Karen Horney and FeminismDocument21 pagesKaren Horney and FeminismSimina ZavelcãNo ratings yet

- Examples of Positive Language PDFDocument2 pagesExamples of Positive Language PDFkalpesh100% (2)

- Femininities, Masculinities, Sexualities: Freud and BeyondFrom EverandFemininities, Masculinities, Sexualities: Freud and BeyondRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Lynne Layton (1998) Gender StudiesDocument11 pagesLynne Layton (1998) Gender StudiesatelierimkellerNo ratings yet

- Gender and Sexuality EssayDocument13 pagesGender and Sexuality EssayDestiny EchemunorNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalytic FeminismDocument6 pagesPsychoanalytic FeminismNithika DamodaranNo ratings yet

- Zotzi 3Document4 pagesZotzi 3Evangelist Kabaso SydneyNo ratings yet

- Gender or Sexual Identity TheoriesDocument5 pagesGender or Sexual Identity TheoriesJV Bryan Singson Idol (Jamchanat Kuatraniyasakul)No ratings yet

- Lennon - Gender and KnowledgeDocument12 pagesLennon - Gender and KnowledgeEmilseKejnerNo ratings yet

- Critical Femininities A New Approach To Gender TheoryDocument9 pagesCritical Femininities A New Approach To Gender Theoryzhoujinjia0724No ratings yet

- Genderchapter RutherfordDocument43 pagesGenderchapter Rutherfordbron sonNo ratings yet

- Saintly Influence: Edith Wyschogrod and the Possibilities of Philosophy of ReligionFrom EverandSaintly Influence: Edith Wyschogrod and the Possibilities of Philosophy of ReligionNo ratings yet

- Juliet Mitchell. Psychoanalysis and FeminismDocument11 pagesJuliet Mitchell. Psychoanalysis and FeminismScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- WWW Iep Utm EduDocument10 pagesWWW Iep Utm EduWawan WibisonoNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism and Gender Relations in Feminist TheoryDocument24 pagesPostmodernism and Gender Relations in Feminist Theorypanos stebNo ratings yet

- Davis, Jena - Beyond Castration, Recognizing Female Desire and Subjectivity in The Oedipus Complex - TEZADocument73 pagesDavis, Jena - Beyond Castration, Recognizing Female Desire and Subjectivity in The Oedipus Complex - TEZATiberiu SNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalytic Feminism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Document26 pagesPsychoanalytic Feminism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)janhavi poddarNo ratings yet

- Conway IntroductionConceptGender 1987Document11 pagesConway IntroductionConceptGender 1987puneya sachdevaNo ratings yet

- "Entering Boys' World" Relational MasculinitiesDocument5 pages"Entering Boys' World" Relational Masculinitiescagedo5892No ratings yet

- Social Construction of GenderDocument11 pagesSocial Construction of GenderKumar Gaurav100% (2)

- Gender StudiesDocument6 pagesGender StudiesElena ȚăpeanNo ratings yet

- Freud and Revolutionary Spirit in 20th Century ChinaDocument13 pagesFreud and Revolutionary Spirit in 20th Century ChinaYuri YuNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Queer TheoryDocument25 pagesUnit 1 Queer TheorypreitylaishramNo ratings yet

- Andrea Dworkin and The Social ConstructionDocument32 pagesAndrea Dworkin and The Social ConstructionXmahannahNo ratings yet

- R Kukla DECENTERING WOMEN PDFDocument26 pagesR Kukla DECENTERING WOMEN PDFDilek ZehraNo ratings yet

- Feminist Standpoint Theory - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyDocument17 pagesFeminist Standpoint Theory - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophySESNo ratings yet

- ArticleText 322348 1 10 20181202Document9 pagesArticleText 322348 1 10 20181202Myra CasapaoNo ratings yet

- Lindquist GENDER 2012Document19 pagesLindquist GENDER 2012Cliff CoutinhoNo ratings yet

- UGGS - Palina Samathuvam1Document14 pagesUGGS - Palina Samathuvam1selvakumar.uNo ratings yet

- Glligan,: Social SelfDocument1 pageGlligan,: Social SelfAikido EurogetNo ratings yet

- Mapping The Middle Way Thoughts On A Buddhist Contribution To A Feminist DiscussionDocument23 pagesMapping The Middle Way Thoughts On A Buddhist Contribution To A Feminist DiscussionGigapedia GigaNo ratings yet

- Book Review: Looking at Siblings Is Looking Anew at Sex and ViolenceDocument5 pagesBook Review: Looking at Siblings Is Looking Anew at Sex and ViolenceCagil Metin BalcıNo ratings yet

- Alterity-Marginality-Difference: On Inventing Places For WomenDocument12 pagesAlterity-Marginality-Difference: On Inventing Places For WomenDELHERBE PÉREZ DISARNo ratings yet

- Royal Institute of International Affairs, Oxford University Press International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)Document19 pagesRoyal Institute of International Affairs, Oxford University Press International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-)selormmensah84No ratings yet

- fiminism عياداتDocument7 pagesfiminism عياداتalkhalidiNo ratings yet

- Dumont 2008Document236 pagesDumont 2008DZCunuckNo ratings yet

- Feminist Critique of ScienceDocument16 pagesFeminist Critique of ScienceZikra MehjabinNo ratings yet

- Root of Women's Oppression/SubordinationDocument8 pagesRoot of Women's Oppression/SubordinationPrincess Janine SyNo ratings yet

- Weldon (2008) - LntersectionalityDocument14 pagesWeldon (2008) - Lntersectionalityangielo_bNo ratings yet

- Cap29-Feminist Standpoint TheoryDocument17 pagesCap29-Feminist Standpoint TheoryJessica Diaz GuadalupeNo ratings yet

- Feminist Standpoint TheoryDocument7 pagesFeminist Standpoint TheoryClancy Ratliff100% (1)

- Abbey Blog TwoDocument4 pagesAbbey Blog Twoapi-264972710No ratings yet

- In Search of Feminist EpistemologyDocument14 pagesIn Search of Feminist EpistemologyMichele BonoteNo ratings yet

- Gender Identity and PsychoanalysisDocument18 pagesGender Identity and PsychoanalysisDim AsNo ratings yet

- Feminism Is Not MonolithicDocument6 pagesFeminism Is Not MonolithicMavis RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 34 Standpoint Theory Presentation Elizabeth HeffnerDocument22 pagesChapter 34 Standpoint Theory Presentation Elizabeth Heffnerbmharvey100% (2)

- Gender Theory SummaryDocument10 pagesGender Theory SummaryDanar CristantoNo ratings yet

- Humana - Mente 22 Gender, Sex, Race, and The FamilyDocument270 pagesHumana - Mente 22 Gender, Sex, Race, and The FamilyambientiNo ratings yet

- Feminist Theory and Research1 PDFDocument19 pagesFeminist Theory and Research1 PDFআলটাফ হুছেইনNo ratings yet

- Queer TheoryDocument17 pagesQueer TheoryRoger Salvador100% (4)

- Dorothy Smith - The Everyday World As ProblematicDocument253 pagesDorothy Smith - The Everyday World As Problematicrffhr5fbpmNo ratings yet

- Sy BookReview CynthiaWeberDocument5 pagesSy BookReview CynthiaWeberjulia pioNo ratings yet

- Psychology and Freudian Sexual Theory in Early 20th Century ChinaDocument47 pagesPsychology and Freudian Sexual Theory in Early 20th Century ChinaYuri YuNo ratings yet

- Queer Theory: A Rough Introduction: DifferencesDocument3 pagesQueer Theory: A Rough Introduction: DifferencesmikiNo ratings yet

- Queer Theory: A Rough Introduction: DifferencesDocument4 pagesQueer Theory: A Rough Introduction: Differencessaqlain3210100% (1)

- The Process of Socialization Sociology Reference GuideDocument197 pagesThe Process of Socialization Sociology Reference Guiderosc8160% (5)

- Chapter 6 FeminismDocument20 pagesChapter 6 FeminismatelierimkellerNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 193.219.130.166 On Tue, 12 Oct 2021 10:40:58 UTCDocument29 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 193.219.130.166 On Tue, 12 Oct 2021 10:40:58 UTCIeva PaukštėNo ratings yet

- Case Study 148 169Document22 pagesCase Study 148 169Vonn GuintoNo ratings yet

- My First 10 Years ProjectDocument2 pagesMy First 10 Years ProjectahdyalNo ratings yet

- SeminarDocument29 pagesSeminarAkash shindeNo ratings yet

- CA Level 1Document43 pagesCA Level 1Cikya ComelNo ratings yet

- UPNMG Press Statement-Unemployed Nurses and MidwivesDocument1 pageUPNMG Press Statement-Unemployed Nurses and MidwivesClavia NyaabaNo ratings yet

- Change Order - Rev2 - 44873036-001Document5 pagesChange Order - Rev2 - 44873036-001Hugo MoralesNo ratings yet

- Ceramic Resonator - Ceralock - 312547Document43 pagesCeramic Resonator - Ceralock - 312547wayan.wandira8122No ratings yet

- The Role of Goverment in Ecotourism DevelopementDocument10 pagesThe Role of Goverment in Ecotourism DevelopementYunita MariaNo ratings yet

- Genetic Mutation LAB SHEET REVISEDDocument2 pagesGenetic Mutation LAB SHEET REVISEDyusufoyololaNo ratings yet

- Ede Micro Project For Tyco StudentsDocument10 pagesEde Micro Project For Tyco StudentsAditya YadavNo ratings yet

- Types of ShoringDocument9 pagesTypes of ShoringAzil14100% (10)

- ASX Announcement 2021 23 - CRU Conference PresentationDocument26 pagesASX Announcement 2021 23 - CRU Conference PresentationÂngelo PereiraNo ratings yet

- Advt 2013 Ver 3Document6 pagesAdvt 2013 Ver 3mukesh_mlbNo ratings yet

- Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris Mid-Term Test SEMESTER 1 SESSION 2020/2021Document3 pagesUniversiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris Mid-Term Test SEMESTER 1 SESSION 2020/2021rusnah chungNo ratings yet

- Nynas Transformer Oil - Nytro 10GBN: Naphthenics Product Data SheetDocument1 pageNynas Transformer Oil - Nytro 10GBN: Naphthenics Product Data SheetAnonymous S29FwnFNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Being Bilingual Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesBenefits of Being Bilingual Lesson PlanCristina BoantaNo ratings yet

- Masterclass ReflectionDocument3 pagesMasterclass Reflectionapi-537874530No ratings yet

- En SATURNevo ZGS.10.20 User Manual 13Document1 pageEn SATURNevo ZGS.10.20 User Manual 13emadsafy20002239No ratings yet

- Syllabus For Applied ElectronicsDocument28 pagesSyllabus For Applied ElectronicsvinayakbondNo ratings yet

- Air Equipment Compressors Compressor 250 300CFM D XAS 125DD Operation ManualDocument34 pagesAir Equipment Compressors Compressor 250 300CFM D XAS 125DD Operation ManualFloyd MG100% (1)

- Cut Out ValveDocument64 pagesCut Out ValveHoang L A TuanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 03 - Louwers 5eDocument23 pagesChapter 03 - Louwers 5eMonique GordonNo ratings yet

- Hazcom ToolsDocument25 pagesHazcom ToolsAbdul hayeeNo ratings yet

- Rw15 ManualDocument314 pagesRw15 ManualpedrogerardohjNo ratings yet

- Classroom Management: Chapter 4 Richards/Renandya Methodology in Language Teaching. (Marilyn Lewis)Document4 pagesClassroom Management: Chapter 4 Richards/Renandya Methodology in Language Teaching. (Marilyn Lewis)Florencia CorenaNo ratings yet

- Moxon Sat AntDocument4 pagesMoxon Sat AntMaureen PegusNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Classroom Assessment PracticesDocument12 pagesTeachers' Classroom Assessment PracticesDaniel BarnesNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - Event Driven ProgrammingDocument22 pagesUnit 5 - Event Driven ProgrammingdharanyaNo ratings yet

- Quiz 01, MTH-501Document9 pagesQuiz 01, MTH-501Shining_900% (1)