Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Comparison Paper 2

Comparison Paper 2

Uploaded by

emsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Comparison Paper 2

Comparison Paper 2

Uploaded by

emsCopyright:

Available Formats

Art of the Female’s Gaze

Edouard Manet’s Olympia and Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon are connected

with the main idea of confrontation. The paintings– which both depict “prostitutes1”– also both

depict these women as defiant, a stark address to the viewer in comparison to the false modesty

and helplessness women were normally depicted as in these times. This tension of the women

directly challenging the belittling male gaze is primarily achieved through how exactly these

women are portrayed to the viewer. For example, women in both paintings stray from the

socially acceptable (and expected) idea of false modesty. Despite the two oil paintings being

created over forty years apart (1863 and 1907, respectively), both seek to disrupt the social norm,

something that we still see today (and likely will continue to see in the future). Picasso and

Manet are not alone in doing so by confronting the audience with their views on women. Women

historically have, and still are, marginalized by the male-dominated hierarchy of the society

around us, and these paintings serve to teach and remind us of that. An unavoidable part of the

human experience is uncomfort. Equally as unavoidable, however, is creativity and the desire to

make art, whatever that may mean person to person. Throughout history, artists have always

found ways to express their pain, discomfort, and frustrations through their art, and seek to make

others feel (whether those feelings are positive or negative) and that is exactly what both Manet

and Picasso have done with Olympia and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, respectively.

Edouard Manet’s piece– Olympia (housed in the Musee d’Orsay in Paris) is an incredibly

influential work. The painting, done with oil paint on canvas, aligns with the style of realism

popular in the 1860s when it was created. This style arose as a result of the changing industry

1

The term “prostitutes” harbors a strong negative connotation which many women protest against. Henceforth, the more neutral

phrase “sex-worker” will be used in its place.

and society around Paris over the course of the 19th century. The rise of science and the decline

of Romanticism paved the way for a more realistic style of painting. Broadly considered the

beginning of modern art, the realism art movement captured the world as it actually appeared,

unlike the preceding idealistic imaging. This style rendered historical and religious works as

equal to depictions of everyday life. Manet’s painting shows a young woman (the titular

“Olympia”), lying relaxed on a bed. She appears in the nude, wearing only a ribbon around her

neck, a flower in her hair, and slippers on her feet in addition to the delicate earrings and bracelet

she wears. At the foot of her bed is a small black cat, standing on the edge of the decorated fabric

underneath her. Standing at her bedside is another woman, presumably a maid or servant, who

brings her a bouquet of flowers. These elements all serve as symbols of Olympia’s wealth and

sensuality. Manet continues to break societal norms in this piece. Rather than being fixed to the

nude form in front of her, Olympia’s servant divides her attention to the bouquet of flowers as

well. The drapery on the wall and bedding surrounding Olympia also appears uninterested in her,

drawing a line away from her rather than to her. Another line unexpectedly drawn is that of the

seam of the wall behind her. Rather than leading the gaze directly to the subject's genitalia (a la

Venus of Urbino), the seam falls just to the right. All of this serves to deemphasize the naked

body the viewer sees before them. The body itself, harshly lit with off-white skin, fulfills the

same service. Manet shows his audience a woman in the nude, but refuses to show her in an

idealized manner, even going so far as to make the body itself unattractive. He is confronting and

refusing to conform to the tradition and standards of “academic art”. At the time of this work, the

artistic environment in Paris served these rules about how art should look, be, and make one feel.

Manet protests these principles which he thought should be cast out for a progressive outlook in

a then modern France.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, a painting from Pablo Picasso in 1907, follows (or rather,

breaks) many of the same rules as Manet did forty years prior. Also a piece done in oil on

canvas, this artwork currently hangs in the MoMa, where it continues to confront its viewers

with its massive stature and revolutionary content. This piece, like many Picasso would become

known for, adopts a cubist style; a far cry from Manet’s realism. Cubism was an early

avant-garde movement of the 20th century wherein an object or figure is shown in an incredibly

abstracted form; sectioned and divided, then reassembled to create a distorted representation of

what it previously was. Cubist art was a protest against the structures of Renaissance art. This

piece depicts five female figures, who are also understood as sex-workers. Rather than

proportional bodies, these women appear as an angular mosaic of fractured and overlapping

parts. Each figure presents herself to the audience. The centermost two lock eyes with the

viewer, hands above their heads to show their chests. The left-most figure pushes back the

curtain– both metaphorically, with her direct eye contact, and physically, as she pushes a corner

of the background. Mirroring her on the right, one woman leans against the background while

the woman in front of her squats with her hands on her knees. All five figures share a dead-set

gaze at the audience of the painting. Intimidating already with their expressionless stare and

active poses, these women are also larger than life-size, with the canvas itself measuring in at

some eight feet by eight feet. Much like Manet did, Picasso also uses the women’s skin as

another controversy. The color of their skin makes their nudity much more abrasive and stark,

rather than a mere lack of clothes. Through all of this, Picasso aimed to challenge the viewer’s

comfort and standards. The size of the women and the painting itself, their locked-in stares, the

flat and splintered imagery all fulfills the main point of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon: to create a

sense of anarchy, both visually and contentwise.

Historically, paintings of women in the nude were depicted with some homage to their

shame or desire to cover up, such as a hand over their genitals, or a face that turns away from the

viewer. In both Olympia and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, however, the women seem to be

flaunting themselves to the audience, enticing them to look rather than shielding themselves from

sight. In Picasso’s painting, for example, the two center-most women stand with their arms

raised, showing off their chests, and their faces turned to look directly at the viewer. The figure at

the bottom right is crouched down with her legs spread, and also meets the eye of the viewer.

Even the figures in the back, with their heads turned, have an eye facing the audience. Similarly,

the titular figure in Manet’s Olympia does not look off to the side as many similar content

paintings at this time do. She also holds eye contact with the viewer. This small detail breaks the

invisible wall separating the viewer from the subject, no longer allowing the viewer to simply

look, but placing them in a two-sided interaction with what they’re looking at. By turning the act

of passively viewing their bodies into an involved action, both Manet and Picasso address that

these female bodies are not there to just be looked at– to just be consumed– but they are the

bodies of people, painted or not. In comparing Olympia and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, we can

see that throughout history, addressing the disparaging treatment of women (and especially sex

workers) is important in order to evolve as a society, and that the art that inspires such evolution

can be done in a powerful and thought-provoking way, and that part of being human is to feel,

which is what both Manet and Picasso want their audiences to do with these pieces.

You might also like

- Richard Martin - The Architecture of David LynchDocument273 pagesRichard Martin - The Architecture of David LynchJp Vieyra Rdz100% (9)

- Bouguereau at WorkDocument43 pagesBouguereau at WorkMassimiliano Failla100% (3)

- Tadanori YokooDocument5 pagesTadanori Yokoosoph sanNo ratings yet

- Feminized Comodities 33pDocument30 pagesFeminized Comodities 33pGabyGaribelloNo ratings yet

- Tos 1st Quarter Mapeh 10Document2 pagesTos 1st Quarter Mapeh 10Dhan Mark Barlintangco100% (1)

- MendietaDocument32 pagesMendietaJoyce LainéNo ratings yet

- Tracing Shadows: Reflections On The Origins of PaintingDocument12 pagesTracing Shadows: Reflections On The Origins of PaintingFrank Hobbs100% (1)

- The Three Curricula That All Schools TeachDocument22 pagesThe Three Curricula That All Schools TeachAhli Sarjana50% (2)

- Arts Integration Lesson PlanDocument9 pagesArts Integration Lesson Planapi-298360094No ratings yet

- Les Demoiselles D'avignon by Pablo Picasso (1907)Document3 pagesLes Demoiselles D'avignon by Pablo Picasso (1907)Rachel Ann BellosoNo ratings yet

- 19th Century Art FinalDocument8 pages19th Century Art FinalPhoebeNo ratings yet

- Les Demoiselles D'avignon - Painting On The Left - Was Created by World-RenownedDocument2 pagesLes Demoiselles D'avignon - Painting On The Left - Was Created by World-RenownedKATRINA PEARL VILLARETNo ratings yet

- UntitleddocumentDocument2 pagesUntitleddocumentapi-344643746No ratings yet

- Art History 4Document6 pagesArt History 4api-329407515No ratings yet

- Lippard Sweeping Exchanges SmithDocument4 pagesLippard Sweeping Exchanges SmithA Guzmán MazaNo ratings yet

- Reassessment of An Accessory: The Fans of Mary Cassatt in The 4th and 5th Impressionist ExhibitionsDocument20 pagesReassessment of An Accessory: The Fans of Mary Cassatt in The 4th and 5th Impressionist Exhibitions詹憶琳No ratings yet

- 07 Nude AwakeningDocument4 pages07 Nude AwakeningdelfinovsanNo ratings yet

- Pablo PicassoDocument7 pagesPablo PicassoRicky SinghNo ratings yet

- Edouard Manet OXFORD UniversityDocument5 pagesEdouard Manet OXFORD UniversityJulia StateriNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Art Research ProjectDocument7 pagesUnit 2 Art Research Projectapi-462907176No ratings yet

- Why Culture Has Come To A Standstill - The New York TimesDocument5 pagesWhy Culture Has Come To A Standstill - The New York TimesCHrisNo ratings yet

- John Searle Las Meninas and The ParadoxDocument7 pagesJohn Searle Las Meninas and The ParadoxcrispasionNo ratings yet

- African ArtDocument16 pagesAfrican Art20his023 Roobini. DNo ratings yet

- 115 121 Ap Art HistoryDocument1 page115 121 Ap Art Historyapi-345465146No ratings yet

- Venus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in Twentieth-century ArtFrom EverandVenus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in Twentieth-century ArtNo ratings yet

- What You Don't Know About Authentic ImpressionismDocument1 pageWhat You Don't Know About Authentic Impressionism2A23 LEE MAN FEINo ratings yet

- Pablo Picasso (25 October 1881 - 8 April 1973)Document35 pagesPablo Picasso (25 October 1881 - 8 April 1973)Shafaq NazirNo ratings yet

- Sexing The CanvasDocument6 pagesSexing The CanvasSofía KalágaNo ratings yet

- Gilman, Sander L. - Black Bodies, White BodiesDocument40 pagesGilman, Sander L. - Black Bodies, White BodiesAndi TothNo ratings yet

- Critique Essay DraftDocument4 pagesCritique Essay DraftАни СафарянNo ratings yet

- Why Art Became Ugly - Stephen HicksDocument6 pagesWhy Art Became Ugly - Stephen HicksMarcel AntonioNo ratings yet

- Different Adaptions of The Female Figure - 1500 Word EssayDocument3 pagesDifferent Adaptions of The Female Figure - 1500 Word Essayapi-278926841No ratings yet

- 01 Readings 5Document2 pages01 Readings 5Michael Vince MasangkayNo ratings yet

- John R. Searle - Las Meninas and The Paradoxes of Pictorial RepresentationDocument13 pagesJohn R. Searle - Las Meninas and The Paradoxes of Pictorial RepresentationCristina TofanNo ratings yet

- Question: Assess The Effect of Time On The Practice of Artists. Nick DenisonDocument4 pagesQuestion: Assess The Effect of Time On The Practice of Artists. Nick DenisonBec TurnbullNo ratings yet

- Roland Barthes On PopDocument5 pagesRoland Barthes On PopjbalviarNo ratings yet

- Alias Olympia: A Woman's Search for Manet's Notorious Model and Her Own DesireFrom EverandAlias Olympia: A Woman's Search for Manet's Notorious Model and Her Own DesireRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (15)

- Cubism: Symbolism in The PaintingDocument3 pagesCubism: Symbolism in The PaintingShale PilapilNo ratings yet

- Benjamin2Document12 pagesBenjamin2sachnish123No ratings yet

- The American Society For Aesthetics and Blackwell Publishing Are Collaborating With JSTOR To DigitizeDocument15 pagesThe American Society For Aesthetics and Blackwell Publishing Are Collaborating With JSTOR To DigitizeMattos CorreiaNo ratings yet

- Semiotics and Western Painting: An Economy of SignsDocument4 pagesSemiotics and Western Painting: An Economy of SignsKavya KashyapNo ratings yet

- LESSON 2.1 - Methods of Pressenting Arts Subjects PDFDocument39 pagesLESSON 2.1 - Methods of Pressenting Arts Subjects PDFChena Berna RolloNo ratings yet

- Primitivism and Twentieth Century ArtDocument9 pagesPrimitivism and Twentieth Century ArtJulian WoodsNo ratings yet

- Why Culture Has Come To A StandstillDocument15 pagesWhy Culture Has Come To A Standstillyuliana.restrepomNo ratings yet

- Modern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting. The Chic Parsienne. Pgs 198-211 255-258Document44 pagesModern Women and Parisian Consumer Culture in Impressionist Painting. The Chic Parsienne. Pgs 198-211 255-258Danica VasiljevićNo ratings yet

- David Foster Wallace Was RightDocument5 pagesDavid Foster Wallace Was RightdragosandrianaNo ratings yet

- Compare and Contrast1111Document2 pagesCompare and Contrast1111api-345131820No ratings yet

- Schubert 1980, Woman and SymbolismDocument7 pagesSchubert 1980, Woman and SymbolismAmber TillijNo ratings yet

- Havens or Prisons: Are Women-Only Exhibitions Still Needed? - Art BaselDocument9 pagesHavens or Prisons: Are Women-Only Exhibitions Still Needed? - Art Baselmaura_reilly_2No ratings yet

- Artartart LiveArt APril09Document30 pagesArtartart LiveArt APril09Nermin Nino KasupovićNo ratings yet

- AP19 - 056-059 Chris AerfeldtDocument2 pagesAP19 - 056-059 Chris AerfeldtaerfeldtNo ratings yet

- What Is Modern Art?: ImpressionismDocument7 pagesWhat Is Modern Art?: ImpressionismKhim KimNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Modern Art in São Paulo, An Introduc!onDocument17 pagesThe Origins of Modern Art in São Paulo, An Introduc!onPriscilaNo ratings yet

- Juan Luna 1884 Pesetas Pambansang Museo NG Pilipinas Roma GladiatorDocument4 pagesJuan Luna 1884 Pesetas Pambansang Museo NG Pilipinas Roma GladiatorjglustadoNo ratings yet

- Reading Beyond Alphonse Mucha in Quest oDocument16 pagesReading Beyond Alphonse Mucha in Quest oj rp (drive livros)No ratings yet

- Synopsis: Futurism DadaDocument5 pagesSynopsis: Futurism DadaAleksandra ButorovicNo ratings yet

- Appel EB VADocument3 pagesAppel EB VAVerónica Stedile LunaNo ratings yet

- Analysis On The New MoMADocument10 pagesAnalysis On The New MoMAartemis burgosNo ratings yet

- Searle Las MeninasDocument13 pagesSearle Las MeninastsebbenNo ratings yet

- Escala, Eng 41, NB, Page61Document2 pagesEscala, Eng 41, NB, Page61Stephanie Joy EscalaNo ratings yet

- Marcel Duchamp FunnyDocument6 pagesMarcel Duchamp FunnyLacie PiconeNo ratings yet

- Arts 10 1st WeekDocument84 pagesArts 10 1st WeekjasminNo ratings yet

- HADA FinalDocument11 pagesHADA FinalemaanlmaoNo ratings yet

- Art Final ProjectDocument11 pagesArt Final ProjectFernanda Guizar ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Pecha KuchaDocument21 pagesPecha KuchaemsNo ratings yet

- ELEM1 - Sem1 Study GuideDocument8 pagesELEM1 - Sem1 Study GuideemsNo ratings yet

- Costume Des. + Prod.Document1 pageCostume Des. + Prod.emsNo ratings yet

- Design ProcessDocument1 pageDesign ProcessemsNo ratings yet

- Production OrganizationDocument2 pagesProduction OrganizationemsNo ratings yet

- Lighting DesignDocument6 pagesLighting DesignemsNo ratings yet

- Tech. Theatre HistoryDocument5 pagesTech. Theatre HistoryemsNo ratings yet

- Costume Des. + Prod.Document1 pageCostume Des. + Prod.emsNo ratings yet

- Lighting DesignDocument5 pagesLighting DesignemsNo ratings yet

- Theatre Midterm EssayDocument2 pagesTheatre Midterm EssayemsNo ratings yet

- Comparison PaperDocument2 pagesComparison PaperemsNo ratings yet

- Scenic Des. + Prod.Document11 pagesScenic Des. + Prod.emsNo ratings yet

- Art History Visual Analysis EssayDocument3 pagesArt History Visual Analysis EssayemsNo ratings yet

- Art History Comparison PaperDocument4 pagesArt History Comparison PaperemsNo ratings yet

- Theatre Histories: Commedia Dell'ArteDocument3 pagesTheatre Histories: Commedia Dell'ArteemsNo ratings yet

- TWTK Final Draft 11-15-22Document96 pagesTWTK Final Draft 11-15-22emsNo ratings yet

- La Recepcion Del Decadentismo en HispanoamericaDocument21 pagesLa Recepcion Del Decadentismo en Hispanoamericabillypilgrim_sfeNo ratings yet

- Dave Liebman On Music EducationDocument18 pagesDave Liebman On Music Educationmaxmusic 121No ratings yet

- Laurie AndersonDocument5 pagesLaurie AndersonCeciBohoNo ratings yet

- SLK 2 For Mapeh (Arts) 9 Quarter 2 Week 3 I. PreliminariesDocument15 pagesSLK 2 For Mapeh (Arts) 9 Quarter 2 Week 3 I. PreliminariesAllenmay LagorasNo ratings yet

- 4545 1 11856 1 10 20150608Document13 pages4545 1 11856 1 10 20150608Jane Limsan PaglinawanNo ratings yet

- MAYA DEREN Deren Magic Is New 1946 PDFDocument8 pagesMAYA DEREN Deren Magic Is New 1946 PDFJuliano GomesNo ratings yet

- Op Art Movement: Mid Term AssignmentDocument8 pagesOp Art Movement: Mid Term Assignmentveekshi0% (1)

- P1ta18-Tessb Execution Schedule (Ta Defect) Painting Level 5 - 13062024Document12 pagesP1ta18-Tessb Execution Schedule (Ta Defect) Painting Level 5 - 13062024Tan Chen KiongNo ratings yet

- Paul Gauguin (1848-1903)Document6 pagesPaul Gauguin (1848-1903)kikikhushi0No ratings yet

- Francis Bacon FocusDocument9 pagesFrancis Bacon FocusleopoldoNo ratings yet

- Art of KoreaDocument15 pagesArt of KoreajunelleandreaNo ratings yet

- Cpar Answer Sheet Module 2Document5 pagesCpar Answer Sheet Module 2nicole catubiganNo ratings yet

- The Artist - June 2018Document3 pagesThe Artist - June 2018nehmehNo ratings yet

- Mediums in Various Forms of ARTDocument47 pagesMediums in Various Forms of ARTJanette Anne Reyes MacaraigNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Oswald Spengler - Steve KoganDocument78 pagesReflections On Oswald Spengler - Steve Koganfsvan100% (1)

- Modern Fiction Virginia WoolfDocument6 pagesModern Fiction Virginia Woolfeepshitahazarika12No ratings yet

- Kate Horsfield - Busting The TubeDocument9 pagesKate Horsfield - Busting The TubeMick KolesidisNo ratings yet

- 1st Quarter Exam in Contempo..Document2 pages1st Quarter Exam in Contempo..May-Ann S. CahiligNo ratings yet

- Introduction of Contemporary ArtsDocument29 pagesIntroduction of Contemporary ArtsFactura NeilNo ratings yet

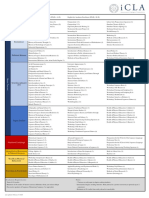

- iCLA Curriculum Course List: English For Academic ExcellenceDocument1 pageiCLA Curriculum Course List: English For Academic ExcellenceStephanie MiramónNo ratings yet

- Profed08 Chapter 2Document10 pagesProfed08 Chapter 2Monica Mae CodillaNo ratings yet

- Essays On Why I Want To Be A NurseDocument7 pagesEssays On Why I Want To Be A Nursegejjavbaf100% (2)

- Baroque and Rococ ArtDocument11 pagesBaroque and Rococ ArtStephen CamsolNo ratings yet