Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Treino 12

Treino 12

Uploaded by

Leonardo SilvaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Treino 12

Treino 12

Uploaded by

Leonardo SilvaCopyright:

Available Formats

EXERCISE ORDER INTERACTS WITH REST INTERVAL

DURING UPPER-BODY RESISTANCE EXERCISE

HUMBERTO MIRANDA,1 ROBERTO SIMÃO,2 PATRÍCIA DOS SANTOS VIGÁRIO,2

BELMIRO FREITAS DE SALLES,2 MARCOS T.T. PACHECO,1 AND JEFFREY M. WILLARDSON3

1

Institute of Research and Development, Vale do Para´ıba University, Sa˜o Jose´ dos Campos,

Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil; 2School of Physical Education and Sports, Federal University of

Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; 3Department of Kinesiology and

Sports Studies, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois

ABSTRACT vs. the beginning of a session, and the reduction in repetition

Miranda, H, Simão, R, dos Santos Vigário, P, de Salles, BF, performance is greater when using 1-minute vs. 3-minute rest

Pacheco, MTT, and Willardson, JM. Exercise order interacts interval between sets.

with rest interval during upper-body resistance exercise. KEY WORDS strength, fatigue, recovery, volume, repetition,

J Strength Cond Res 24(6): 1573–1577, 2010—The purpose performance

of this study was to compare repetition performance when

resting 1 minute vs. 3 minutes between sets and exercises for INTRODUCTION

an upper-body workout performed in 2 different sequences.

O

ne of the key variables in resistance exercise

Sixteen recreationally trained men completed 4 experimental prescription involves the order in which exercises

resistance exercise sessions. All sessions consisted of 3 sets are programmed during a workout. This can

with an 8–repetition maximum load for 6 upper-body exercises. determine the effectiveness of a workout in

Two different exercise sequences (i.e., A or B) were performed accomplishing different training goals. For example, when

with either 1- or 3-minute rest between sets and exercises, training for power, high velocity/ballistic style exercises are

respectively. For sequence A1 (SEQA1) and sequence A3 typically programmed at the beginning of a workout when

(SEQA3), resistance exercises were performed in the following the neuromuscular system is in a nonfatigued state and

order: lat pull-down with a wide grip (LPD-WG), lat pull-down capable of higher contractile velocities and rates of force

with a close grip (LPD-CG), machine seated row (SR-M), production (1,2).

The traditional recommendation regarding exercise order

barbell row lying on a bench (BR-B), dumbbell seated arm curl

has been to perform multijoint exercises before single-joint

(SAC-DB), and machine seated arm curl (SAC-M). Conversely,

exercises. Prior studies demonstrated that this approach

for sequence B1 (SEQB1) and sequence B3 (SEQB3), the

allowed for greater workout volume (load 3 repetitions)

exercises were performed in the opposite order. The results compared with when single-joint exercises were performed

demonstrated that the effect of exercise order was stronger first (3,11–13,15). Specifically, Sforzo and Touey (11) demon-

than the effect of rest interval length for LPD-WG (SEQA3 . strated a 22% decline in workout volume (load 3 repetitions)

SEQA1 . SEQB3 . SEQB1) and SAC-M (SEQB3 . SEQB1 on the first set of squats when preceded by leg curls and leg

. SEQA3 . SEQA1), whereas the effect of rest interval length extensions. Spreuwenberg et al. (15) demonstrated a 32%

was stronger than the effect of exercise order for LPD-CG, decline in total repetitions on the first set of squats when

SR-M, SAC-DB (SEQA3 = SEQB3 . SEQA1 = SEQB1), and preceded by the lunge, stiff leg deadlift, and hang pull. These

BR-B (SEQB3 . SEQA3 = SEQB1 . SEQA1). These results studies highlight the need to program the order of exercises

suggest that upper-body exercises involving similar muscle so that weak muscle groups or movement patterns in greatest

need of improvement are performed first in a sequence.

groups and neural recruitment patterns are negatively affected

Simao et al. (12,13) demonstrated that performing

in terms of repetition performance when performed at the end

exercises for either large or small muscle groups at the end

of a sequence resulted in significant reductions in repetition

Address correspondence to Jeffrey M. Willardson, jmwillardson@eiu.edu. performance. When exercises are performed at the end of

Study conducted at the Rio de Janeiro Federal University. a sequence, longer rest intervals between sets may help

24(6)/1573–1577 prevent fatigue-related reductions in repetition performance.

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research Previous studies that examined rest interval lengths ranging

Ó 2010 National Strength and Conditioning Association from 30 seconds to 5 minutes between sets consistently

VOLUME 24 | NUMBER 6 | JUNE 2010 | 1573

Exercise Order and Rest Interval

demonstrated significant reductions in repetition performance between sets and exercises, respectively. For sequence

and workout volume with shorter rest intervals (4,7–9,17–19). A1 (SEQA1) and sequence A3 (SEQA3), exercises were

Ratamess et al. (8) compared differences in workout performed in the following order: (a) lat pull-down with

volume over 5 sets of the bench press exercise when per- a wide grip (LPD-WG), (b) lat pull-down with a close grip

formed at 2 different intensities (i.e., 75 and 85%) and with (LPD-CG), (c) machine seated row (SR-M), (d) barbell row

5 different rest intervals between sets (i.e., 30 seconds and 1, lying on a bench (BR-B), (e) dumbbell seated arm curl (SAC-

2, 3, and 5 minutes). The findings demonstrated that DB), and (f ) machine seated arm curl (SAC-M). Conversely,

irrespective of the intensity, workout volume significantly for sequence B1 (SEQB1) and sequence B3 (SEQB3), the

decreased with each set in succession over 5 sets when exercises were performed in the opposite order. All exercises

30-second and 1-minute rest intervals were used. Workout in each session were performed for 3 sets to voluntary

volume was maintained over 2 sets for 2 minutes, 3 sets for exhaustion using the predetermined 8RM load. The total

3 minutes, and 4 sets for 5 minutes. Consequently, the authors number of repetitions completed for each exercise (over 3

recommended that if more than 2–3 sets of an exercise are sets) was recorded.

performed, then at least 2 minutes of rest might be needed to

minimize loading reductions and maintain repetition perfor- Subjects

mance for the sets performed at the end of a workout. Sixteen recreationally trained men (25 6 4.16 years; 175 6

However, a limitation of the study by Ratamess et al. (8) 5 cm; 77.37 6 4.96 kg; 9.86 6 2.34% body fat) participated

and similarly designed studies (4,7,9,17–19) was the exam- in this study. All subjects had previous resistance training

ination of single exercise, when workouts typically consist of experience (6.36 6 2.47 years), with a mean frequency of four

multiple exercises for the same muscle groups. Reductions 60-minute sessions per week, using 1- to 2-minute rest interval

in repetition performance might be more pronounced for between sets and exercises. All subjects were assessed via the

exercises performed at the end vs. the beginning of a workout, Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (i.e., PAR-Q) (14)

thus highlighting the importance of prioritizing the order and signed an informed consent in accordance with the

of exercises and the need to possibly include longer rest Declaration of Helsinki. Subjects were encouraged to report

intervals between sets at the end of a workout. No studies to for workout sessions fully hydrated and to be consistent in

date have examined the interaction between exercise order their food intake throughout the duration of the study.

and rest interval length. Therefore, the purpose of the current

study was to compare repetition performance when resting Eight–Repetition Maximum Testing

1 vs. 3 minutes between sets and exercises for an upper-body The 8RM tests were conducted over 3 nonconsecutive days

workout performed in opposite sequences. in the following order: LPD-WG, LPD-CG, SR-M, BR-B,

SAC-DB, and SAC-M. All machine-based exercises were

METHODS

performed on Life Fitness equipment (Brunswick Company,

Experimental Approach to the Problem Franklin Park, Illinois, USA). During the 8RM testing, each

A workout that involved entirely upper-body exercises was subject performed a maximum of three 8RM attempts for

examined during the current study because upper-body each exercise, with 5-minute rest between attempts (4) and

muscle groups are sometimes worked on different days from 10-minute rest between tests for different exercises (5).

lower-body muscle groups in program designs that in- Standard exercise techniques were followed for each exercise.

corporate split routines (2). We acknowledge that exercises No pause was allowed between the eccentric and concentric

for the upper and lower body are often combined within the phases of repetitions. For a repetition to be successful,

same workout. The current study was designed to examine a complete range of motion (as normally defined) for each

one of many commonly used training approaches and is thus exercise had to be completed.

applicable to workouts that involve similar muscle groups

and neural recruitment patterns for the upper body. Experimental Sessions

For the current study, data were collected on 7 non- Forty-eight to 72 hours after completing the third day of 8RM

consecutive days that were separated by 48–72 hours. The testing, subjects performed SEQA1, SEQA3, SEQB1, or

8 repetition maximum (8RM) for all exercises was determined SEQB3 in a randomized crossover design. Forty-eight to 72

on the first day and repeated on days 2 and 3. An 8RM load hours separated performance of each of the 4 sessions and all

was used to be consistent with prior studies that examined sessions were performed at the same time of day. Warm-up

repetition performance with different rest intervals at similar before each session consisted of 2 sets of 12 repetitions of the

intensities (4,7–9,17,18). A randomized crossover design was first exercise (i.e., LPD-WG in SEQA1 and SEQA3; SAC-M

used to determine the exercise sequence in combination with in SEQB1 and SEQB3) at 40% of the 8RM load. A 2-minute

the rest interval between sets and exercises for workout rest interval was allowed after the warm-up set before subjects

sessions performed on days 4, 5, 6, and 7. performed the assigned workout (SEQA1, SEQA3, SEQB1,

Two different exercise sequences (i.e., A or B) were or SEQB3). Subjects were verbally encouraged to perform all

performed with either a 1-minute or a 3-minute rest interval sets to voluntary exhaustion. No attempt was made to control

the TM

1574 Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

the TM

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research | www.nsca-jscr.org

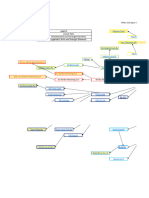

Figure 1. Repetition performance SEQA1, SEQB1, SEQA3, and SEQB3 (mean 6 SD). *Significant difference repetitions vs. SEQA1. †Significant difference

repetitions vs. SEQB1. ‡Significant difference repetitions vs. SEQA3. #Significant difference repetitions vs. SEQB3.

the repetition velocity; however, subjects were required to DISCUSSION

use a smooth and controlled motion. The total number of

The key finding from the current study was that the effect of

repetitions for each exercise (over 3 sets) was recorded and

exercise order was stronger than the effect of rest interval

later compared between sessions. length for the LPD-WG and the SAC-M, whereas the effect of

Statistical Analyses rest interval length was stronger than the effect of exercise

The statistical analysis was initially done by the Shapiro-Wilk order for the LPD-CG, SR-M, BR-B, and SAC-DB. These

normality test and by the homoscedasticity test (Bartlett results suggest that upper-body exercises involving similar

criterion). All variables presented normal distribution and muscle groups and neural recruitment patterns are negatively

homoscedasticity. To compare repetition performance (de- affected in terms of repetition performance when performed

pendent variable) for each exercise, a 1-way repeated analysis at the end vs. the beginning of a session and the reduction

of variance was conducted for each of the 6 exercises during in repetition performance is greater when using 1-minute vs.

the 4 sessions (SEQA1, SEQA3, SEQB1, and SEQB3), 3-minute rest interval between sets.

followed by Bonferroni post hocs. An alpha level of p # 0.05 These results highlight the importance of carefully pro-

was used to determine the significance of comparisons. The gramming the order of exercises and rest intervals between

statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 13.0 software sets to maximize repetition performance. For example, when

(SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). using 3-minute rest interval between sets, performing the

LPD-WG or SAC-M at the beginning of a session resulted in

RESULTS greater total repetitions (e.g., 23.0 6 1.4 and 24.5 6 2.9) vs.

The 8RM load intraclass coefficients for each exercise were performing these exercises at the end of a session (e.g., 12.1 6

as follows: LPD-WG = 0.94, LPD-CG = 0.95, SR-M = 0.93, 2.2 and 14.1 6 2.1). Therefore, the total repetitions completed

BR-B = 0.93, SAC-DB = 0.95, and SAC-M = 0.96. The total nearly doubled when the LPD-WG or SAC-M was placed at

repetitions completed for each exercise of SEQA1, SEQA3, the beginning vs. the end of the workout. The same trends

SEQB1, and SEQB3 are presented in Figure 1. Based on the were noted when using 1-minute rest intervals in performing

exercise order, there were significant differences (p , 0.05) LPD-WG or SAC-M at the beginning of a session (e.g., 19.1 6

in the total repetitions completed for LPD-WG (SEQA3 . 1.7 and 20.0 6 1.4) vs. the end of a session (e.g., 6.5 6 1.3 and

SEQA1 . SEQB3 . SEQB1) and for SAC-M (SEQB3 . 10.4 6 2.5).

SEQB1 . SEQA3 . SEQA1). Based on the rest interval, When considering exercises performed in the middle of

there were significant differences (p , 0.05) in the total a session, longer rest intervals between sets and exercises

repetitions completed for LPD-CG, SR-M, and SAC-DB resulted in greater total repetitions. For example, the SR-M

(SEQA3 = SEQB3 . SEQA1 = SEQB1) and for BR-B was the third exercise performed during sequence A and the

(SEQB3 . SEQA3 = SEQB1 . SEQA1). fourth exercise performed during sequence B. During

VOLUME 24 | NUMBER 6 | JUNE 2010 | 1575

Exercise Order and Rest Interval

sequence A, greater repetitions were performed for the SR-M PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

when resting 3 minutes vs. 1 minute between sets and The implications of this study are applicable to the design

exercises (19.1 6 2.6 vs. 15.0 6 2.9). Similarly, during of upper-body workouts with the goal of maximizing

sequence B, greater repetitions were performed for the SR-M repetition performance in recreationally trained men. For

when resting 3 minutes vs. 1 minute between sets and exercises programmed toward the end of a workout,

exercises (18.5 6 3.3 vs. 12.0 6 3.4). Therefore, when training

reductions in repetition performance might be negated by

for upper-body strength, longer rest intervals between sets

using longer rest intervals between sets. However, long-term

and exercises may provide a superior stimulus because of training with shorter rest intervals, as in programs designed

greater total repetitions performed with a given load and for hypertrophy or muscular endurance, may allow for

consequently greater workout volume. greater fatigue resistance: a topic that should be examined in

These findings were consistent with previous studies that future research.

demonstrated greater repetitions when using longer rest

intervals between sets (4,7–9,17–19). However, a limitation of ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

these studies was the evaluation of 1 or 2 exercises; thus,

Ms. H. Miranda is grateful to CAPES for the financial support.

potential differences for a typical workout that involves

Dr. R. Simão would like to thank the Brazilian National Board

multiple exercises could not be evaluated. The potential

for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and

reductions in repetition performance during a typical

Research and Development Foundation of Rio de Janeiro

workout likely depend on factors such as the muscle mass

State (FAPERJ).

involved, the movements examined, and especially long-term

training practices. REFERENCES

Kraemer et al. (6) compared 9 competitive bodybuilders

1. American College of Sports Medicine. Position stand on progression

and 8 competitive power lifters on a 10-station resistance models in resistance exercise for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc

exercise circuit. Three consecutive sets of each exercise were 34: 364–380, 2002.

performed with a 10RM load; subjects rested 10 seconds 2. Fleck, SJ and Kraemer, WJ. Designing Resistance Training Programs.

between sets and 30–60 seconds between exercises. The key Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2004.

finding was that the bodybuilders demonstrated less re- 3. Gentil, P, Oliveira, E, Rocha Junior, VA, Do Carmo, J, and Bottaro, M.

Effects of exercise order on upper-body muscle activation and exercise

duction in repetition performance. The authors concluded performance. J. Strength Cond Res 21: 1082–1086, 2007.

that the bodybuilders demonstrated greater fatigue resistance 4. Kraemer, WJ. A series of studies: The physiological basis for strength

because of adaptations associated with the bodybuilding style training in American football: Fact over philosophy. J Strength Cond

of training (e.g., moderate to high repetition sets combined Res 11: 131–142, 1997.

with shorter rest intervals). Although not assessed, these 5. Kraemer, WJ and Fry, AC. Strength testing: Development and

evaluation of methodology. In: Physiological Assessment of Human

adaptations likely involved development of the fast glycolytic Fitness. Maud, P and Foster, C, eds. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics,

energy system, with higher activities of anaerobic enzymes 1995. pp. 115–138.

(e.g., phosphorylase, phosphofructokinase, and lactate de- 6. Kraemer, WJ, Noble, BJ, Clark, MJ, and Culver, BW. Physiologic

hydrogenase), thus delaying proton accumulation and responses to heavy-resistance exercise with very short rest periods.

metabolic acidosis (10,16). Int J Sports Med 8: 247–252, 1987.

An important point is that the results of the current study 7. Larson, GD and Potteiger, JA. Comparison of three different rest

intervals between multiple squat bouts. J Strength Cond Res 11: 115–

may not apply to lower-body exercises. Prior research demon- 118, 1997.

strated greater fatigue resistance for lower-body exercises vs. 8. Ratamess, RA, Falvo, MJ, Mangine, GT, Hoffman, JR, Faigenbaum, AD,

the upper-body exercises. Willardson and Burkett (17) and Kang, J. The effect of rest interval length on metabolic responses

examined repetition performance for recreationally trained to the bench press exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 100: 1–17, 2007.

men over 4 sets of bench press and back squat with an 8RM 9. Richmond, SR and Godard, PM. The effects of varied rest periods

between sets to failure using the bench press in recreationally trained

load and 1-minute rest intervals between sets. For the bench men. J Strength Cond Res 18: 846–849, 2004.

press, subjects performed 7.47 6 1.06 repetitions on the first 10. Robergs, RA, Ghiasvand, F, and Parker, D. Biochemistry of exercise

set, followed by 4.40 6 1.64, 2.87 6 1.30, and 2.40 6 1.18 induced metabolic acidosis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol

repetitions on the second, third, and fourth sets, respectively. 287: R502–R516, 2004.

For the backs squat, subjects performed 7.87 6 0.52 repetitions 11. Sforzo, GA and Touey, PR. Manipulating exercise order affects

on the first set, followed by 5.93 6 1.90, 4.47 6 1.85, and 4.20 muscular performance during a resistance exercise training session.

J Strength Cond Res 10: 20–24, 1996.

6 1.94 repetitions on the second, third, and fourth sets,

12. Simao, R, Farinatti, PTV, Polito, MD, Maior, AS, and Fleck, SJ.

respectively. Greater fatigue resistance was demonstrated for Influence of exercise order on the number of repetitions performed

the back squat vs. the bench press, as evidenced by less and perceived exertion during resistance exercises. J Strength Cond

discrepancy in repetition performance between the first and Res 19: 152–156, 2005.

the last sets. However, future research should examine a lower- 13. Simao, R. Farinatti, PTV, Polito, MD, Viveiros, L, and Fleck, SJ.

Influence of exercise order on the number of repetitions performed

body workout (and other large muscle mass exercises) and perceived exertion during resistance exercise in women.

performed in succession. J Strength Cond Res 21: 23–28, 2007.

the TM

1576 Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research

the TM

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research | www.nsca-jscr.org

14. Shephard, RJ. PAR-Q, Canadian home fitness test and exercise 17. Willardson, JM and Burkett, LN. A comparison of 3 different rest

screening alternatives. Sports Med 5: 185–195, 1988. intervals on the exercise volume completed during a workout.

15. Spreuwenberg, LPB, Kraemer, WJ, Spiering, BA, Volek, JS, Hatfield, DL, J Strength Cond Res 19: 23–26, 2005.

Silvestre, R, Vingren, JL, Fragala, MS, Hakkinen, K, Newton, RU, 18. Willardson, JM and Burkett, LN. The effect of rest interval length on

Maresh, CM, and Fleck, SJ. Influence of exercise order in a resistance- bench press performance with heavy versus light loads. J Strength

training exercise session. J Strength Cond Res 20: 141–144, 2006. Cond Res 20: 400–403, 2006.

16. Weiss, LW. The obtuse nature of muscular strength: The 19. Willardson, JM and Burkett, LN. The effect of rest interval length on

contribution of rest to its development and expression. J Appl Sports the sustainability of squat and bench press repetitions. J Strength

Sci Res 5: 219–227, 1991. Cond Res 20: 396–399, 2006.

VOLUME 24 | NUMBER 6 | JUNE 2010 | 1577

You might also like

- Fit Well Core Concepts and Labs in Physical Fitness and Wellness 15Th Edition Thomas D Fahey Full ChapterDocument67 pagesFit Well Core Concepts and Labs in Physical Fitness and Wellness 15Th Edition Thomas D Fahey Full Chapterlina.philpott914100% (14)

- 12-Week Menopause Strength Training Program: But If You're Reading This, I'm Here To Tell You: There Is HOPEDocument21 pages12-Week Menopause Strength Training Program: But If You're Reading This, I'm Here To Tell You: There Is HOPEMJ RocherNo ratings yet

- 2013-Power Output and Electromyography Activity of The Back Squat Exercise With Cluster SetsDocument9 pages2013-Power Output and Electromyography Activity of The Back Squat Exercise With Cluster SetsA man about townNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Designing Relative Strength ProgramsDocument35 pagesFundamentals of Designing Relative Strength ProgramsFlorian WolfNo ratings yet

- 2nd SHS-Exam-in-PE-and-Health-11-Midterm-Exam-SY-2017-2018-Answer-SheetDocument2 pages2nd SHS-Exam-in-PE-and-Health-11-Midterm-Exam-SY-2017-2018-Answer-Sheetkathryn soriano86% (7)

- BodybuildingDocument3 pagesBodybuildingakramshhaideh0% (1)

- (18997562 - Journal of Human Kinetics) Influence of Exercise Order On Electromyographic Activity During Upper Body Resistance TrainingDocument8 pages(18997562 - Journal of Human Kinetics) Influence of Exercise Order On Electromyographic Activity During Upper Body Resistance TrainingGOVARDHANNo ratings yet

- Treino 14Document5 pagesTreino 14Leonardo SilvaNo ratings yet

- Senna2011 PDFDocument7 pagesSenna2011 PDFAlexandre FerreiraNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Rest Interval Length On Multi and Single-Joint Exercise Performance and Perceived ExertionDocument7 pagesThe Effect of Rest Interval Length On Multi and Single-Joint Exercise Performance and Perceived ExertionAlexandre FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Effects of Static Stretching On Repeated Sprint and Change of Direction PerformanceDocument7 pagesEffects of Static Stretching On Repeated Sprint and Change of Direction Performancemehdi.chlif4374No ratings yet

- Supersets and Pre-Exhaustion: Advanced Training PracticesDocument47 pagesSupersets and Pre-Exhaustion: Advanced Training PracticesHamada MansourNo ratings yet

- Paz Et Al. 2019 - CIrcuit, Paired Set and Trad J Sports Med Phys FitnessDocument12 pagesPaz Et Al. 2019 - CIrcuit, Paired Set and Trad J Sports Med Phys Fitnessjk trainerNo ratings yet

- Volume Load and Neuromuscular Fatigue During An Acute Bout of Agonist-Antagonist Paired-Set vs. T Raditional-Set TrainingDocument8 pagesVolume Load and Neuromuscular Fatigue During An Acute Bout of Agonist-Antagonist Paired-Set vs. T Raditional-Set TrainingjepoNo ratings yet

- A Repeated Power Training Enhances Fatigue Resistance While Redu 2018Document11 pagesA Repeated Power Training Enhances Fatigue Resistance While Redu 2018RobertoNo ratings yet

- JSCR 2011 Stretching FDDocument8 pagesJSCR 2011 Stretching FDJonatas GomesNo ratings yet

- JSC 0b013e3181c7c5fdDocument6 pagesJSC 0b013e3181c7c5fdKeep AskingNo ratings yet

- RM System Tri-SetDocument10 pagesRM System Tri-SetJudson BorgesNo ratings yet

- Effects of Horizontal and Incline Bench Press On Neuromuscular Adaptations in Untrained Young MenDocument14 pagesEffects of Horizontal and Incline Bench Press On Neuromuscular Adaptations in Untrained Young MenAndré Evandro MartinsNo ratings yet

- The Effect of An Upper-Body Agonist - Antagonist Resistance Training Protocol On Volume Load and EfficiencyDocument9 pagesThe Effect of An Upper-Body Agonist - Antagonist Resistance Training Protocol On Volume Load and EfficiencyjepoNo ratings yet

- (18997562 - Journal of Human Kinetics) Heavy Vs Light Load Single-Joint Exercise Performance With Different Rest IntervalsDocument10 pages(18997562 - Journal of Human Kinetics) Heavy Vs Light Load Single-Joint Exercise Performance With Different Rest IntervalsIgor CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Postactivation Potentiation Effects AfteDocument4 pagesPostactivation Potentiation Effects AfteQuốc HuyNo ratings yet

- Paz 2020 - Paired Set EMG Vs TraditionalDocument6 pagesPaz 2020 - Paired Set EMG Vs Traditionaljk trainerNo ratings yet

- Acute Effect of Two Aerobic Exercise ModesDocument5 pagesAcute Effect of Two Aerobic Exercise Modeswander_dukaNo ratings yet

- 2011 - Boutcher - High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise and Fat LossDocument8 pages2011 - Boutcher - High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise and Fat LossJuanNo ratings yet

- Effects of 8 Weeks Equal-Volume Resistance TrainingDocument7 pagesEffects of 8 Weeks Equal-Volume Resistance TrainingChimpompumNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Compensatory Acceleration On Upper-Body Strength and Power in Collegiate Football PlayersDocument7 pagesThe Effects of Compensatory Acceleration On Upper-Body Strength and Power in Collegiate Football PlayersDeepak SinghNo ratings yet

- Chest Press Exercises With Different Stability Requirements Result PDFDocument9 pagesChest Press Exercises With Different Stability Requirements Result PDFPaulo CavalcantiNo ratings yet

- JSCR 08 8500Document9 pagesJSCR 08 8500alexandremagnopersonalNo ratings yet

- Burke Et Al - Treinamento, Método - 2024Document34 pagesBurke Et Al - Treinamento, Método - 2024alexandremagnopersonalNo ratings yet

- E R I L A B R E M: Ffects of EST Nterval Ength On Cute Attling OPE Xercise EtabolismDocument13 pagesE R I L A B R E M: Ffects of EST Nterval Ength On Cute Attling OPE Xercise EtabolismJúnior Alvacir CamargoNo ratings yet

- Paz Et Al. 2016 - Static Stretching Intraset - Science and SportsDocument8 pagesPaz Et Al. 2016 - Static Stretching Intraset - Science and SportsAnonymous MBhnGoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Different Recovery Patterns On Repeated-Sprint Ability andDocument10 pagesEffect of Different Recovery Patterns On Repeated-Sprint Ability andCharisNo ratings yet

- Ações ExcentricasDocument5 pagesAções ExcentricasJonatas GomesNo ratings yet

- Ratings of Perceived Exertion in Active Muscle During High-Intensity and Low-Intensity Resistance ExerciseDocument5 pagesRatings of Perceived Exertion in Active Muscle During High-Intensity and Low-Intensity Resistance ExerciseSimra ZahidNo ratings yet

- Short Term Effects of Complex and ContrastDocument6 pagesShort Term Effects of Complex and ContrastKoordinacijska Lestev Speed LadderNo ratings yet

- Effects of Single Versus Multiple Bouts of Resistance Training On Maximal Strength and Anaerobic PerformanceDocument10 pagesEffects of Single Versus Multiple Bouts of Resistance Training On Maximal Strength and Anaerobic Performancemarian osorio garciaNo ratings yet

- Acute Effects of Antagonist Static Stretching in The Inter-Set Rest Period On Repetition Performance and Muscle ActivationDocument14 pagesAcute Effects of Antagonist Static Stretching in The Inter-Set Rest Period On Repetition Performance and Muscle Activationamirreza jmNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Back Squat & Safety Squat Bar On Measures of Strength, Speed, and Power in NCAA Division I Baseball PlayersDocument8 pagesA Comparison of Back Squat & Safety Squat Bar On Measures of Strength, Speed, and Power in NCAA Division I Baseball Playerstadao.andoNo ratings yet

- Series para MMII e MMSS PDFDocument6 pagesSeries para MMII e MMSS PDFJúnior Alvacir CamargoNo ratings yet

- Articulo 3Document9 pagesArticulo 3Camilo RinconNo ratings yet

- The Effects of A 7-Week Heavy Elastic Band and Weight Chain Program On Upper-Body Strength and Upper-Body Power in A Sample of Division 1-AA Football PlayersDocument9 pagesThe Effects of A 7-Week Heavy Elastic Band and Weight Chain Program On Upper-Body Strength and Upper-Body Power in A Sample of Division 1-AA Football PlayersKeijoNo ratings yet

- Mtorc1 Complex1Document8 pagesMtorc1 Complex1Ffabio DeangelisNo ratings yet

- Push Ups Vs Bench Press Differences in RDocument9 pagesPush Ups Vs Bench Press Differences in RManuel Geronimo Solorzano ChavarroNo ratings yet

- Asjsm 21649Document5 pagesAsjsm 21649Daniel FreireNo ratings yet

- Journal of Bodywork & Movement TherapiesDocument6 pagesJournal of Bodywork & Movement TherapiesGabrielDosAnjosNo ratings yet

- Tufano2017 - Cluster SetDocument20 pagesTufano2017 - Cluster Setjk trainerNo ratings yet

- Experimental Gerontology: Short ReportDocument6 pagesExperimental Gerontology: Short ReportratnaNo ratings yet

- 3sets TrainingDocument5 pages3sets TrainingNeuNo ratings yet

- 2019 Frigotto - Gluteus Medius and Tensor Fascia Latae Muscle ActivationDocument7 pages2019 Frigotto - Gluteus Medius and Tensor Fascia Latae Muscle ActivationGabriel BeloNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Home-Based Stretching Program On Bench Press Maximum Strength and Shoulder FlexibilityDocument8 pagesEffects of A Home-Based Stretching Program On Bench Press Maximum Strength and Shoulder Flexibilitycesar saucedoNo ratings yet

- KORAK at Al, 2018 Effect of A Rest Pause Vs Traditional Squat OnDocument6 pagesKORAK at Al, 2018 Effect of A Rest Pause Vs Traditional Squat OnalexandremagnopersonalNo ratings yet

- Lacerda 2016 - Variations in Repetition Duration and Repetition Numbers Influence Muscular Activation and Blood Lactate ResponseDocument8 pagesLacerda 2016 - Variations in Repetition Duration and Repetition Numbers Influence Muscular Activation and Blood Lactate ResponseMarcelo Teixeira de AndradeNo ratings yet

- K A S V P - U: Inetic Nalysis of Everal Ariations of USH PSDocument4 pagesK A S V P - U: Inetic Nalysis of Everal Ariations of USH PSNicolás ManonniNo ratings yet

- University of Edinburgh College of Humanities and Social ScienceDocument26 pagesUniversity of Edinburgh College of Humanities and Social ScienceKineseba SANo ratings yet

- Effect of 3 Different Active Stretch Durations On Hip Flexion Range of MotionDocument7 pagesEffect of 3 Different Active Stretch Durations On Hip Flexion Range of MotionchrisNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Direct SupervisionDocument10 pagesThe Influence of Direct SupervisionKennedyOliverNo ratings yet

- E Vect of High Versus Low-Velocity Resistance Training On Muscular Wtness and Functional Performance in Older MenDocument8 pagesE Vect of High Versus Low-Velocity Resistance Training On Muscular Wtness and Functional Performance in Older MenRenata SouzaNo ratings yet

- 07 - JSCR - Effect of Short Term Equal Volume Resistance Training With Different Workout Frequency On Muscle Mass and Strength in Untrained Men and WomenDocument4 pages07 - JSCR - Effect of Short Term Equal Volume Resistance Training With Different Workout Frequency On Muscle Mass and Strength in Untrained Men and WomenEmerson AlissonNo ratings yet

- Farias, 2017 - Bench Press EMG Implements - JSCRDocument9 pagesFarias, 2017 - Bench Press EMG Implements - JSCRAbimael Corrêa da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Captura de Tela 2023-09-09 À(s) 06.38.44Document7 pagesCaptura de Tela 2023-09-09 À(s) 06.38.44jotta de lima BragaNo ratings yet

- D - S - S W U: T E P A P: Ynamic Vs Tatic Tretching ARM P HE Ffect On Ower and Gility ErformanceDocument8 pagesD - S - S W U: T E P A P: Ynamic Vs Tatic Tretching ARM P HE Ffect On Ower and Gility Erformancefelci.oscarNo ratings yet

- JSSM 13 460Document9 pagesJSSM 13 460Bryan HuaritaNo ratings yet

- Tempo de Curso de Força e Recuperação de EnergiaDocument9 pagesTempo de Curso de Força e Recuperação de EnergiaThiago SartiNo ratings yet

- Enhancing the Benefits of Nauli with a Key Exercise for Abdominal Muscle Strength: Second EditionFrom EverandEnhancing the Benefits of Nauli with a Key Exercise for Abdominal Muscle Strength: Second EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ch05 Active Sports and Recreation PDFDocument12 pagesCh05 Active Sports and Recreation PDFRakkard R. NihupaNo ratings yet

- For This CompositionDocument1 pageFor This Compositionmagyi skaNo ratings yet

- Gym Training PDF V2Document47 pagesGym Training PDF V2Savannah AgarNo ratings yet

- My Fitness GoalsDocument10 pagesMy Fitness GoalsRegie C. LabostaNo ratings yet

- Health Optimizing Physical Education (Hope) 1 Grade 11 Exercise For FitnessDocument17 pagesHealth Optimizing Physical Education (Hope) 1 Grade 11 Exercise For FitnessPaul Francis LagmanNo ratings yet

- Division-Diagnostic Test-Pe 10Document3 pagesDivision-Diagnostic Test-Pe 10MaryfelBiascan-SelgaNo ratings yet

- Planning of The Training in Team Handball: November 2019Document10 pagesPlanning of The Training in Team Handball: November 2019Milan PančićNo ratings yet

- (Journal of Human Kinetics) A Review On The Effects of Soccer Small-Sided Games PDFDocument11 pages(Journal of Human Kinetics) A Review On The Effects of Soccer Small-Sided Games PDFsujiNo ratings yet

- Hope - 1 Grade 11: Exercise For FitnessDocument13 pagesHope - 1 Grade 11: Exercise For FitnessEZRA THERESE DE JESUSNo ratings yet

- The Effects of A Yoga Intervention On Balance Speed and Endurance of Walking Fatigue and Quality of Life in People With Multiple SclerosisDocument8 pagesThe Effects of A Yoga Intervention On Balance Speed and Endurance of Walking Fatigue and Quality of Life in People With Multiple SclerosisIsbah ShahidNo ratings yet

- Group 14 - A Life Plan For Effective Human RelationsDocument57 pagesGroup 14 - A Life Plan For Effective Human RelationsDennisBriones100% (1)

- Health-Eating-Habit Physical EducationDocument38 pagesHealth-Eating-Habit Physical EducationKc ManalastasNo ratings yet

- HOPE11 q4 Mod4 Healthrelatedfitnessphysicalactivityassessment v5Document14 pagesHOPE11 q4 Mod4 Healthrelatedfitnessphysicalactivityassessment v5Shiela Jane PechonNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3: Implementing The Safety and Physical Activity PlanDocument12 pagesLesson 3: Implementing The Safety and Physical Activity PlanJopit Olavario RiveraNo ratings yet

- Elements of Fitness: Siff and Verkhoshansky (2009)Document8 pagesElements of Fitness: Siff and Verkhoshansky (2009)P NocuNo ratings yet

- Pe1 Lesson 4 Cardiorespiratory and Muskuloskeletal FitnessDocument53 pagesPe1 Lesson 4 Cardiorespiratory and Muskuloskeletal Fitnessdario serranoNo ratings yet

- Training ProgramDocument6 pagesTraining ProgramChicco ChiggxNo ratings yet

- The Calisthenics Skill Tree (Template) 1.6.1Document50 pagesThe Calisthenics Skill Tree (Template) 1.6.1sdsaNo ratings yet

- Peter Herbert - Rugby Training GuideDocument28 pagesPeter Herbert - Rugby Training Guidealephillo100% (1)

- Lower Division: Health and Family Life Education (HFLE) Resource Guide For TeachersDocument150 pagesLower Division: Health and Family Life Education (HFLE) Resource Guide For TeachersAnteNo ratings yet

- The Intermediate 5K Training Plan: If You're A Runner With Some Experience, Give This Plan A TryDocument3 pagesThe Intermediate 5K Training Plan: If You're A Runner With Some Experience, Give This Plan A TryJaneneNo ratings yet

- Strength Hypertrophy (3x)Document11 pagesStrength Hypertrophy (3x)akljoanna95No ratings yet

- PE Module 4 AnswersDocument2 pagesPE Module 4 AnswersKrisha RosalesNo ratings yet

- Review of Literature For Physical FitnessDocument18 pagesReview of Literature For Physical FitnessKyla AmoyenNo ratings yet

- (2010) The 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test - 10 Year ReviewDocument9 pages(2010) The 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test - 10 Year Reviewvemigix162No ratings yet