Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adams 2011

Adams 2011

Uploaded by

utariCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Path of Ascension Book 1 Final Edit - TM1 DONEDocument470 pagesThe Path of Ascension Book 1 Final Edit - TM1 DONELeonardo Cruz Garcia100% (1)

- Fire Risk Assessment-Rev 001Document5 pagesFire Risk Assessment-Rev 001ramodNo ratings yet

- Angel of GroznyDocument348 pagesAngel of GroznySportyANK100% (1)

- Jurnal Vol 1 No 1Document58 pagesJurnal Vol 1 No 1bodiwenNo ratings yet

- s12966 019 0798 1Document15 pagess12966 019 0798 1hey rizkiNo ratings yet

- Literature PHDocument4 pagesLiterature PHNoel KalagilaNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Community-Based Nutrition Education On The Nutrition Status of Under-Five Children in Developing Countries. A Systematic ReviewDocument4 pagesThe Effectiveness of Community-Based Nutrition Education On The Nutrition Status of Under-Five Children in Developing Countries. A Systematic ReviewDesy rianitaNo ratings yet

- Muhoozi 2017Document11 pagesMuhoozi 2017Dewi PrasetiaNo ratings yet

- 2007 FoodNutrBull 375 RoySKDocument9 pages2007 FoodNutrBull 375 RoySKhafsatsaniibrahimmlfNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667268522000092 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S2667268522000092 MainveraNo ratings yet

- The Role of Schools in Preventing Childhood ObesityDocument4 pagesThe Role of Schools in Preventing Childhood ObesityEMMANUELNo ratings yet

- Feeding ArvedsonDocument10 pagesFeeding ArvedsonPablo Oyarzún Dubó100% (1)

- Situational Analysis of Nutritional Status Among 1989 Children Presenting With Cleft Lip Palate in IndonesiaDocument13 pagesSituational Analysis of Nutritional Status Among 1989 Children Presenting With Cleft Lip Palate in Indonesiacvdk8dc8sbNo ratings yet

- Effective Interventions To Address Maternal and Child Malnutrition: An Update of The EvidenceDocument18 pagesEffective Interventions To Address Maternal and Child Malnutrition: An Update of The EvidenceChris ValNo ratings yet

- Contextual Effect of "Posyandu" in The Incidence of Anemia in Children Under FiveDocument10 pagesContextual Effect of "Posyandu" in The Incidence of Anemia in Children Under FiveEgy SunandaNo ratings yet

- Research ReportDocument8 pagesResearch ReportAbid SherazNo ratings yet

- Assess The Effect of Nutritional Status, Food Consumption, Physical Activity Among School ChildrenDocument5 pagesAssess The Effect of Nutritional Status, Food Consumption, Physical Activity Among School ChildrenInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The First 1000 Days: A Critical Period of Nutritional Opportunity and VulnerabilityDocument3 pagesThe First 1000 Days: A Critical Period of Nutritional Opportunity and VulnerabilityEffika YuliaNo ratings yet

- Wong 2014Document10 pagesWong 2014eka wahyuni wahyuniNo ratings yet

- Clinical Nutrition: Feeding Difficulties in Children With Inherited Metabolic Disorders: A Pilot StudyDocument9 pagesClinical Nutrition: Feeding Difficulties in Children With Inherited Metabolic Disorders: A Pilot StudyGita Fajar WardhaniNo ratings yet

- Lectura Control 2 - Asignatura 3Document12 pagesLectura Control 2 - Asignatura 3CamilaGarridoNo ratings yet

- StuntingDocument9 pagesStuntingAnonymous q8VmTTtmXQNo ratings yet

- BMC Public Health: Irregular Breakfast Eating and Health Status Among Adolescents in TaiwanDocument7 pagesBMC Public Health: Irregular Breakfast Eating and Health Status Among Adolescents in TaiwanMiss LeslieNo ratings yet

- Seizure Disorders: School-Age Children and Adolescents 609Document30 pagesSeizure Disorders: School-Age Children and Adolescents 609Fahri GunawanNo ratings yet

- Bhutta Interventions LCAH 2021Document18 pagesBhutta Interventions LCAH 2021Angelica EstipularNo ratings yet

- NPT en PediatriaDocument22 pagesNPT en PediatriaFernanda Sanchez LozanoNo ratings yet

- 10 11648 J SJPH 20130102 12Document6 pages10 11648 J SJPH 20130102 12SukmaNo ratings yet

- Viewpoint Article: Childhood Obesity - Looking Back Over 50 Years To Begin To Look ForwardDocument5 pagesViewpoint Article: Childhood Obesity - Looking Back Over 50 Years To Begin To Look ForwardichalsajaNo ratings yet

- Neurodesarrollo y Reciperacion Despues de Desnutricion AgudaDocument10 pagesNeurodesarrollo y Reciperacion Despues de Desnutricion AgudaJesusMiguelCorneteroMendozaNo ratings yet

- Multilevel Intervention Model To Improve Nutrition of Mother and Children in Banyumas RegencyDocument9 pagesMultilevel Intervention Model To Improve Nutrition of Mother and Children in Banyumas RegencyVerawaty AwaludinNo ratings yet

- Sullivan, P 2010Document1 pageSullivan, P 2010Donna OhNo ratings yet

- Review (Lassi, 2020)Document21 pagesReview (Lassi, 2020)melody tuneNo ratings yet

- A Disseration Submitted As A Partial Fulfilment For Award of The Diploma in Community Nutrition.Document8 pagesA Disseration Submitted As A Partial Fulfilment For Award of The Diploma in Community Nutrition.Prince HakimNo ratings yet

- Mcpherson 2016Document11 pagesMcpherson 2016shafyd ramdanNo ratings yet

- An Interventional Study To Evaluate The Effectiveness of Selected Nutritional Diet On Growth of Pre Schooler at Selected Slums Area of Bhopal M.PDocument6 pagesAn Interventional Study To Evaluate The Effectiveness of Selected Nutritional Diet On Growth of Pre Schooler at Selected Slums Area of Bhopal M.PEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Healthcare: Nutritional Education Is An Effective Tool in Improving Beverage Assortment in Nurseries in PolandDocument13 pagesHealthcare: Nutritional Education Is An Effective Tool in Improving Beverage Assortment in Nurseries in PolandLa HusyainNo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding Is An Unsurpassed Method of Providing Ideal Food For The Healthy Growth and Development of InfantsDocument4 pagesBreastfeeding Is An Unsurpassed Method of Providing Ideal Food For The Healthy Growth and Development of InfantsSatra SabbuhNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 13 01712 v2Document21 pagesNutrients 13 01712 v2INFOKOM BPOMPALUNo ratings yet

- Dietary Inadequacy Is Associated With Anemia and Suboptimal Growth Among Preschool-Aged Children in Yunnan Province, ChinaDocument9 pagesDietary Inadequacy Is Associated With Anemia and Suboptimal Growth Among Preschool-Aged Children in Yunnan Province, ChinaDani KusumaNo ratings yet

- Developing and Implementing A Telehealth Enhanced Interdisciplinary Pediatric Feeding Disorders Clinic - A Program Description and EvaluationDocument18 pagesDeveloping and Implementing A Telehealth Enhanced Interdisciplinary Pediatric Feeding Disorders Clinic - A Program Description and EvaluationPaloma LópezNo ratings yet

- Child Eating Behaviors and Caregiver Feeding Practices in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument10 pagesChild Eating Behaviors and Caregiver Feeding Practices in Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderspedroNo ratings yet

- Poor Nutrition ProjectDocument60 pagesPoor Nutrition Projectaniamulu munachimNo ratings yet

- Stunted Growth RESEARCH PAPERDocument23 pagesStunted Growth RESEARCH PAPERRemelyn OcatNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document6 pagesChapter 1Geralden Vinluan PingolNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status of School Age Children in Private Elementary Schools: Basis For A Proposed Meal Management PlanDocument5 pagesNutritional Status of School Age Children in Private Elementary Schools: Basis For A Proposed Meal Management PlanIjaems JournalNo ratings yet

- Chapte 1 2 - Group 5 1Document19 pagesChapte 1 2 - Group 5 1arlenetacla12No ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0250562Document16 pagesJournal Pone 0250562addanaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Nutritional Supplementation During The - 2022 - The Lancet RegDocument11 pagesEffectiveness of Nutritional Supplementation During The - 2022 - The Lancet RegCawee CawNo ratings yet

- Healthy Eating and Obesity Prevention For Preschoolers: A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesHealthy Eating and Obesity Prevention For Preschoolers: A Randomised Controlled TrialRiftiani NurlailiNo ratings yet

- Revised Chapter 1 3Document26 pagesRevised Chapter 1 3Noel BarcelonNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 (Food Supplement)Document26 pagesCHAPTER 1 (Food Supplement)Noel BarcelonNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S0002916522010693-Main InterDocument8 pages1-S2.0-S0002916522010693-Main InterAlimah PutriNo ratings yet

- 2022 9 4 9 RavivDocument12 pages2022 9 4 9 RavivSome445GuyNo ratings yet

- Lipid Based Suppl Vs CSB Mod Underwt Malawi 2010Document14 pagesLipid Based Suppl Vs CSB Mod Underwt Malawi 2010Fiqah KasmiNo ratings yet

- Breast vs. Bottle: Differences in The Growth of Croatian InfantsDocument9 pagesBreast vs. Bottle: Differences in The Growth of Croatian InfantsBernadette Grace RetubadoNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Education Programs Aimed at African Mothers of Infant Children A Systematic ReviewDocument19 pagesNutrition Education Programs Aimed at African Mothers of Infant Children A Systematic ReviewDicky Estosius TariganNo ratings yet

- Estreñimiento y TeaDocument9 pagesEstreñimiento y TeaElena Martin LopezNo ratings yet

- DietaryDiversity Mahmudionoetal2017Document10 pagesDietaryDiversity Mahmudionoetal2017ainindyaNo ratings yet

- Sdarticle 142 PDFDocument1 pageSdarticle 142 PDFRio Michelle CorralesNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Under Nutrition Among School Age Children in A Nairobi Peri-Urban SlumDocument10 pagesDeterminants of Under Nutrition Among School Age Children in A Nairobi Peri-Urban SlumJean TanNo ratings yet

- Adv Nutr 2011 Sharma 207S 16SDocument10 pagesAdv Nutr 2011 Sharma 207S 16SAlbert Lawrence KwansaNo ratings yet

- Maternal and Pediatric Nutrition JournalDocument6 pagesMaternal and Pediatric Nutrition JournalStacey CruzNo ratings yet

- Building Future Health and Well-Being of Thriving Toddlers and Young Children: 95th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, September 2020From EverandBuilding Future Health and Well-Being of Thriving Toddlers and Young Children: 95th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, September 2020No ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document28 pagesLecture 3Lovely ZahraNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Illustrated Anatomy of The Head and Neck 5th by FehrenbachDocument8 pagesSolution Manual For Illustrated Anatomy of The Head and Neck 5th by FehrenbachxewazixNo ratings yet

- IUPAC NomenclatureDocument17 pagesIUPAC Nomenclaturesurya kant upadhyay100% (3)

- Be-Pdp-Fr-07-E Papso Form Roanoke To Sa - j7Document2 pagesBe-Pdp-Fr-07-E Papso Form Roanoke To Sa - j7Ricardo Frank CordeiroNo ratings yet

- Critical RatioDocument13 pagesCritical RatioFatiima Tuz ZahraNo ratings yet

- MI31004 Economics of Mining Enterprises ES 2018Document2 pagesMI31004 Economics of Mining Enterprises ES 2018Taurai MudzimuiremaNo ratings yet

- Viscosity-1 Viscometer-2 Relation Between Viscosity &temperature-3 Vogel Equation-4 Programming ofDocument71 pagesViscosity-1 Viscometer-2 Relation Between Viscosity &temperature-3 Vogel Equation-4 Programming ofDr_M_SolimanNo ratings yet

- My Dream Hotel: By. YeongseoDocument7 pagesMy Dream Hotel: By. YeongseoYoutube whiteNo ratings yet

- Engine Failure WGBDocument33 pagesEngine Failure WGBRohan SinhaNo ratings yet

- Figure 1: Schematic Diagram of A Tray Dryer. (Geankoplis, 2003)Document2 pagesFigure 1: Schematic Diagram of A Tray Dryer. (Geankoplis, 2003)Nesha Arasu0% (1)

- 2020 OWS InfographicsDocument1 page2020 OWS InfographicsElisha PaloNo ratings yet

- Living A Life of LordshipDocument52 pagesLiving A Life of Lordshipmung_khatNo ratings yet

- Makerere Research FormatDocument7 pagesMakerere Research FormatMurice ElaguNo ratings yet

- I. Work/Practice Exercise: Hussin, Shadimeer Reyes Bs Biology 2-CDocument3 pagesI. Work/Practice Exercise: Hussin, Shadimeer Reyes Bs Biology 2-CScar ShadowNo ratings yet

- Trouble Shooting in Vacuum PumpDocument12 pagesTrouble Shooting in Vacuum Pumpj172100% (1)

- P-Value (Definition, Formula, Table & Example)Document1 pageP-Value (Definition, Formula, Table & Example)Niño BuenoNo ratings yet

- Graphing Quadratic Functions in Standard Form Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesGraphing Quadratic Functions in Standard Form Lesson Planapi-401400552100% (1)

- Abs Wabco HabsDocument20 pagesAbs Wabco HabsBom_Jovi_681No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Solutions DetailedDocument30 pagesChapter 1 Solutions DetailedYeonjae JeongNo ratings yet

- Shock AmbossDocument40 pagesShock AmbossAshraf AlbhlaNo ratings yet

- Paste Copy FTTXDocument8 pagesPaste Copy FTTXfttxjpr JaipurNo ratings yet

- 04a. Quadratics - The Quadratic Formula and The DiscriminantDocument1 page04a. Quadratics - The Quadratic Formula and The Discriminantjingcong liuNo ratings yet

- English Eald s6 Sample Paper 1 Stimulus BookletDocument5 pagesEnglish Eald s6 Sample Paper 1 Stimulus BookletHouston ChantonNo ratings yet

- Beadwork - November 2015 PDFDocument84 pagesBeadwork - November 2015 PDFIoan Cristian Popescu100% (24)

- 3492 0022 01 - LDocument16 pages3492 0022 01 - LJoe SmithNo ratings yet

- Pe Module Q1Document21 pagesPe Module Q1alexanlousumanNo ratings yet

- Question Bank-Unit 2: MATH 2300Document8 pagesQuestion Bank-Unit 2: MATH 2300ROHAN TRIVEDI 20SCSE1180013No ratings yet

Adams 2011

Adams 2011

Uploaded by

utariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adams 2011

Adams 2011

Uploaded by

utariCopyright:

Available Formats

Child:

Original Article

care, health and development

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01327.x

Feeding difficulties in children with cerebral palsy:

low-cost caregiver training in Dhaka, Bangladesh cch_1327 1..11

M. S. Adams,* N. Z. Khan,‡ S. A. Begum,‡ S. L. Wirz,* T. Hesketh* and T. R. Pring†

*Centre for International Health and Development, UCL Institute of Child Health

†City University London, London, UK, and

‡Child Development and Neurology Unit, Dhaka Shishu (Children’s) Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Accepted for publication 9 July 2011

Abstract

Background The majority of children with cerebral palsy have feeding difficulties, which, if not

managed, result in stressful mealtimes, chronic malnutrition, respiratory disease, reduced quality of

life for caregiver and child, and early death. In well-resourced countries, high- and low-cost medical

interventions, ranging from gastrostomy tube feeding to caregiver training, are available. In

resource-poor countries such as Bangladesh, the former is not viable and the latter is both scarce

and its effectiveness not properly evaluated. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness

of a low-cost, low-technology intervention to improve the feeding practices of carers of children

with moderate–severe cerebral palsy and feeding difficulties in Bangladesh.

Methods An opportunistic sample of 37 caregivers and their children aged 1–11 years were invited

to a six-session training programme following an initial feeding assessment with brief advice. During

home visits, pre- and post-measures of nutritional status, chest health and feeding-related stress

were taken and feeding practices were observed. A control phase was evaluated for 20 of the

participant pairs following initial assessment with advice, while awaiting full training.

Keywords

caregiver education, Results A minimum of four training sessions showed significant improvements in the children’s

cerebral palsy, feeding respiratory health (P = 0.005), cooperation during mealtimes (P = 0.003) and overall mood

disorders, interventions,

low-income setting,

(P < 0.001). Improvements in growth were inconsistent. Dramatic reductions were observed in

maternal stress caregiver stress (P < 0.001). A significant difference in the outcomes following advice only compared

with advice plus training was also observed.

Correspondence:

Conclusions In situations of poverty, compliance is restricted by lack of education, finances and

Melanie S. Adams, City

University London, time. Nonetheless, carers with minimal formal education, living in conditions of extreme poverty

Northampton Square, were able to change feeding practices after a short, low-cost training intervention, with highly

London EC1V 0HB, UK

E-mail:

positive consequences. The availability of affordable food supplementation for this population,

mel.adams@uclmail.net however, requires urgent attention.

most common cause of disability in children. Globally, 2.5 in

Introduction

every 1000 children are born with CP (Stanley et al. 2000) with

Improvements in perinatal care over the past three decades have more developing it post-neonatally. In situations of poverty,

led to increased survival rates. This has meant, however, that inadequate obstetric care and risk factors such as low birth-

many children who would not previously have survived infancy weight can increase this figure to 40–50 per 1000 live births

are now living with conditions such as cerebral palsy (CP), the (Sullivan et al. 2000). In 2000, a population-based study of

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1

2 M.S. Adams et al.

children aged 2–9 years in Bangladesh (Mobarak et al. 2000) The aim of the intervention itself was to promote child health

estimated the prevalence of severe disability to be 22/1000. and well-being through maximizing children’s nutritional

In the developing world the burden of care for the child with intake, minimizing the risks of chest infection associated with

CP falls almost entirely on the family. Up to 90% of these feeding, and reducing the stress experienced by the children and

children are reported to have feeding difficulties (Reilly et al. their caregivers during mealtimes.

1996), leading to moderate–severe secondary malnutrition and

limited fluid intake, which in turn leads to a further decrease in Methods

level of functioning, health and well-being (Sullivan & Rosen-

bloom 1996). The impact is further exacerbated in the context Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical review commit-

of widespread malnutrition and in a study conducted in Bang- tees of The UCL Institute of Child, and The Bangladesh Insti-

ladesh, malnutrition was found to be the leading cause of death tute of Child Health, Dhaka. Consent was obtained from

for children with CP in urban and rural populations (Khan participants regarding involvement in the study, publication of

et al. 1998). the results, and for all photographs and video footage.

Difficulties with feeding also create a risk of aspiration, which The study was conducted in three slums of Dhaka and at the

predisposes children with CP to recurrent respiratory disease. In Child Development and Neurology Unit of the Dhaka Shishu

a study by Reddihough and colleagues (2001), the primary (Children’s) Hospital (a national centre of excellence). Three

cause of death in 155 children with severe CP in Australia was slums were targeted for their proximity to the hospital, in order

pneumonia. Feeding children with CP can be extremely chal- to facilitate home visiting and attendance at the training ses-

lenging and can take caregivers up to 7 h a day (Johnson & Deitz sions held in the hospital.

1985). Caregiver stress is consequently high (Reilly & Skuse

1992; Sullivan et al. 2002), which in turn promotes unrespon- Participants

sive feeding practices, feeding in a controlling and often abusive The participants were recruited by opportunistic sampling and

manner, which leads to further difficulties (Black 1999; Hurley identified mainly through a non-governmental organization

et al. 2008). Mealtimes are frequently distressing for the child (NGO) network of urban primary healthcare programmes.

and caregiver alike (Sullivan et al. 2000). Workshops were run for the NGO fieldworkers to inform them

Despite years of investigation into the problems of feeding in about the study, followed by four screening days arranged in

CP children, limited attention has been paid to this population different sub-centres, to make a preliminary selection of partici-

by health services, even in high-income countries (Sullivan et al. pants. Sixty children were screened, of which a total of 40 child–

2000). Nonetheless, in such countries, a range of services and caregiver pairs were identified. Of these, three subsequently

expertise exists to support these children, with an emphasis on declined participation.

high-technology medical procedures, such as the introduction Inclusion criteria were: moderate–severe CP (levels III–V on

of alternative feeding methods where required. This can result the Gross Motor Function Classification Scale; Palisano et al.

in significant improvements with regard to child weight, health 1997), reported or observed feeding difficulties, fully or semi-

and well-being, and reductions in time spent feeding, thus also weaned (i.e. not exclusively breastfeeding) and aged 1–11 years.

improving the quality of life of the caregivers (Sullivan et al. Children were excluded if they had a progressive or metabolic

2004, 2005). However, such services in resource-poor countries condition, were chronically sick (cardiac, renal, gastrointesti-

are very scarce (Mobarak et al. 2000) and little research has been nal), had a congenital syndrome, were taking steroids or thy-

conducted on the benefits of low-cost, low-technology solu- roxin or receiving feeding services elsewhere. Participants were

tions, essential for addressing these issues in the developing assessed prior to entering groups at which time basic advice was

world. given. As some degree of dropout was expected, it was decided

This study was therefore set up to design, implement and on ethical grounds that basic advice at initial assessment, to

evaluate a low-cost intervention, to address the feeding difficul- reduce the risks of aspiration and to promote nutritional intake,

ties of children with moderate–severe CP in Dhaka, Bangladesh, was essential.

with a view to informing appropriate service development for

this population and their caregivers. The intervention was based

Conduct of the study

on the most widely respected practices developed by healthcare

professionals in the West and supported by the literature (see Following recruitment, 37 child–caregiver pairs were visited

Table 1). at home to take baseline assessment data and subsequently

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

Management of feeding difficulties in Bangladesh 3

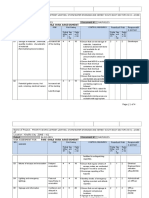

Table 1. Summary of training objectives and rationales

Training objective Rationale Related child outcomes Reference

1. Introduce high-calorie, balanced Increase nutritional intake through Weight gain. Gisel & Patrick (1988)

diet, given in small amounts improved diet and increased Reilly et al. (1996)

frequently. quantity of food consumed. Trier & Thomas (1998)

Socrates et al. (2000)

2. Adapt food consistency as Reduce risks of aspiration by enabling Reduction in chest-related illness. Gisel & Patrick (1988)

appropriate. more effective oral and pharyngeal Improved oral feeding skills. Rogers et al. (1994)

management of food. Increase Increased child cooperation. Trier & Thomas (1998)

nutritional intake through reduced Weight gain.

effort, increased calorie density of

food and encouragement of more

mature oral feeding patterns.

3. Use appropriate utensils. Reduce risks of aspiration by enabling Reduction in chest-related illness. Trier & Thomas (1998)

more effective oral and pharyngeal Reduced child distress.

management of food. Encourage Increased child cooperation.

more mature feeding patterns and Weight gain.

increase nutritional intake.

4.1 Adapt feeding method: Facilitate Decrease risks of aspiration. Reduction in chest-related illness. Trier & Thomas (1998)

appropriate trunk and head Facilitate maximization of physical Maximization of self-feeding skills. Waterman et al. (1992)

position during feeding. abilities. Increased child cooperation. Larnert & Ekberg (1995)

Weight gain. Selley et al. (2001)

Gisel et al. (2003)

West & Redstone (2004)

4.2 Adapt feeding method: Provide Reduce spillage and assist chewing/ Improved oral feeding skills. Haberfellner et al. (2001)

support for jaw stability where overall oral management of the Weight gain. Selley et al. (2001)

necessary. food.

4.3 Adapt feeding method: Foster Increase nutritional intake through Weight gain. Waterman et al. (1992)

self-feeding skills. increasing desire to eat and ability

to eat independently.

4.4 Adapt feeding method: Use Decrease risks of aspiration, increase Reduction in chest-related illness. Engle (2000)

sensitive, proactive and nutritional intake and decrease Weight gain. Selley et al. (2001)

responsive feeding methods distress to child through enabling Reduced risk of diarrhoeal disease. Moore et al. (2006)

(including hygienic cooking and the more effective management of Decreased child distress. Hurley et al. (2008)

feeding practices). food. Increased child cooperation.

Increase nutritional intake through

physically facilitating feeding, and

by increasing child’s desire to eat

and their enjoyment of mealtimes.

Reduce risk of food contamination

through increased hygiene.

enrolled into training groups of four to five pairs (a total of The intervention programme, comprising training and

eight groups) consisting of six fortnightly sessions. The number support, was informed by the literature (see Table 1), by reports

of participants was limited by the researchers’ capacity for con- on previous training programmes conducted in similar settings,

ducting home visits and the hospital unit’s capacity for running including nutrition programmes in Bangladesh, and through

groups. These were led by generic therapists already working in consultation with other carers of children with CP.

the unit who had received specific training in delivering the The programme focused on improving dietary intake and

programme and were supervised by the primary author ease and efficiency of feeding through the following key com-

throughout. Follow-up home visits to review outcomes took ponents: (1) introduce a calorie-dense, balanced diet, given in

place immediately after training (first review) and again after small amounts frequently; (2) adapt food consistency to be

4–6 months (second review). Some degree of control was orally manageable; (3) use appropriate utensils; and (4) feed

achieved by reviewing 20 pairs following initial advice (3–4 the child in a sensitive and responsive manner, providing

months after their initial assessment and advice session), while appropriate postural and physical support for positioning and

awaiting intervention. self-feeding (see Table 1).

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

4 M.S. Adams et al.

The recommended diet was based on two local recipes (one Analysis of the qualitative data followed the constant com-

rice-based and one milk-based) which had been modified for parative approach used in Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss

children with moderate–severe malnutrition by ICDDR,B (The 1967) in order to identify key themes in relation to caregivers’

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bang- perceptions of feeding and the outcomes of the training.

ladesh) and were thus high in nutritional value, especially in

calories. The consistencies of these two recipes were also easy to

manage orally, as they were smooth, soft and moist when cooked. Results

Each training session included educational content as well as

Characteristics of the participants and the mealtime experi-

supervised feeding. Teaching methods included traditional

ence before intervention are summarized in Table 2. Using the

pedagogy, discussion, participatory and experiential activities

World Health Organization growth standards (2006) and

and the use of visual aids including a 20-min video drama

comparative values obtained from the Bangladesh Child and

created especially for the programme. Each child was given a

Mother Nutrition Survey 2005 (BBS/UNICEF 2007), the study

low-cost seat ($5) made of reinforced cardboard using the tech-

children were 2.1 z-scores below their non-disabled peers with

niques of Appropriate Paper-based Technology (Packer 1995),

regard to mean weight-for-age (WAZ), 0.97 z-scores below for

and a plastic teaspoon and cup bought in the local market1.

height-for-age (HAZ) and 2.27 z-scores below for weight-for-

height (WHZ). Seventy-four per cent of caregivers scored

Outcome measures above the threshold of 7 points for psychological disturbance

on The Self-Reporting Questionnaire 20 items (SRQ20)

Effectiveness of the intervention in relation to nutritional status

anxiety scale (Harding et al. 1980). Mean fluid intake, through

was assessed through anthropometric measurement using rec-

drinks, was 201.8 mL (SD 178.9). Caregiver comments regard-

ommended measures of growth (Sullivan et al. 2002; Yousafzai

ing their experience of the feeding process were almost exclu-

et al. 2003) including weight, mid-upper-arm circumference and

sively negative and included admissions of abusive behaviour,

demi-arm span2 as well as 24-h and monthly food and fluid recall

as follows.

charts completed verbally by carers. Chest health was monitored

through carer reports on the frequency of respiratory illness, I feel angry sometimes and hit him when I have to force

while child feeding skills and affect during feeding were rated him hard to eat. At that time I have to hold all his limbs

using video footage of observed mealtimes. Overall child mood down in lying position.

was assessed through carer reports. Caregiver outcomes were I beat her because it’s hard work for me and it takes a long

evaluated through semi-structured interviews in which they time.

were asked to rate their feelings with regard to their child’s

feeding difficulties and recall the amount of time spent in I always feel impatient because he cries a lot, so I shout at

feeding. Carer compliance with the training recommendations him and bite him.

was also assessed through interview and observation. In order to

enable the systematic scoring of child and caregiver behaviours

Post-intervention outcomes

during mealtimes, a checklist was developed. This was tested for

inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s Kappa (Cohen 1960), which Of the 37 participant pairs recruited to the study, 13 dropped

for the majority of variables was ‘good’ (60–75%) or ‘excellent’ out at various stages. The main reason was due to the family

(>75%) according to the categories of Fleiss (1981). moving away, usually back to the village because of financial

difficulties (n = 7). Other reasons included lack of caregiver

Analysis motivation or time (n = 3), caregiver sickness (n = 1) and child

sickness (n = 2). A further two participants only received one

Statistical analysis was conducted using spss (version 15.0). follow-up review, again because of sickness (see Fig. 1).

Data were analysed using independent and paired samples Complete data were thus collected on 22 child–caregiver pairs,

t-tests where appropriate. For non-parametric data, the Fried- 17 of whom attended four to six training sessions. Significant or

man test, the Wilcoxon signed ranks test and the McNemar test highly significant improvements were observed at follow-up in

were used. several areas. At the second review (see Table 3), these included

1

For further details on the intervention, please contact the main author. significant improvements in chest health (P = 0.005), nutritional

2

Used as a proxy for length, due to deformities of the spine and limbs. status (P = 0.02), child feeding skills (P < 0.001) and child mood

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

Management of feeding difficulties in Bangladesh 5

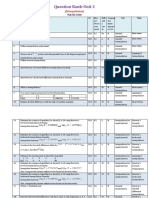

Table 2. Participant data prior to intervention

Children

Age Mean Range SD

3 years, 11 months 19–129 months 2 years, 3 months

Gender n

Male 8

Female 14

CP type n

Spastic 17

Hypotonic 3

Athetoid 1

Mixed 1

Severity of CP n

Level III (moderate) 3

Level IV (severe) 3

Level V (severe) 16

Anthropometrics (Cole et al. 1998) Mean SD

WAZ -4.83 1.84

HAZ -2.70 1.98

BMIZ -4.08 2.86

Chest-related illnesses n

Weekly 2

Monthly 7

2–3 monthly 7

<3 monthly 6

Daily fluid intake (through drinks) Mean Range SD

168.1 mL 0–375 mL 108.2

Discomfort/distress during feeding n

Any observed discomfort/distress 14

Caregivers

Overall anxiety (SRQ20) Mean SD Score >7*

10.0 4.5 16 (72.7)

Caregiver stress re-feeding n

Very stressed 19

Somewhat stressed 3

*Score above threshold for psychological disturbance (Mari & Williams 1985).

CP, cerebral palsy; WAZ, weight-for-age; HAZ, height-for-age; BMIZ, body mass index z-score; SRQ20, The

Self-Reporting Questionnaire 20 items.

(P < 0.001). Improvements in child affect during feeding were He was screaming before with all food and I had to force

almost significant (P = 0.059). Benefits to caregivers included him, but now he eats without screaming and I don’t have

decreased stress with regard to feeding (P < 0.001), and a per- to force him.

ceived reduction in mealtime length (P < 0.001). For the pur-

My child laughs now. Before, she cried a lot. Now when I

poses of comparing overall compliance between individuals, a

feed my child she responds well. She finds eating is easier.

measure scoring carer behaviour change on a number of indices

Before, she used to get annoyed.

was devised. Using this measure, carers who received advice plus

training achieved significantly higher scores than those who Before, I couldn’t imagine my child would be able to eat

received initial advice only [t(40) = 6.82, P < 0.001]. rice and now I’m so surprised that he can.

Qualitative statements from caregivers focused mainly on

changes in child affect (improved mood, cooperation and An illustration of the overall changes during mealtimes is

decreased distress during feeding) and the ability to eat and shown in Fig. 2. Other reported changes included improve-

drink more easily with a greater range of textures, as illustrated ments in communication, interaction, participation and general

in the following comments: mobility.

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

6 M.S. Adams et al.

Cohort 1 Baseline 1st 2nd

(BSL) Review Review

Training No input

groups

10 months

Initial 2.5 4–5 months 2nd post-

assessment months 1st post- training

& advice training review

review

n =16 n =13 n =11 n =10

Cohort 2 Baseline Post- 1st 2nd

(BSL) advice Review Review

No input review Training No input

groups

14 months

3–4 months Post-advice 2.5 4–6 months 2nd post-

Initial review & months 1st post- training

assessment advice training review

& advice reiterated review

n =21 n =20 n =15 n =13 n =12

Figure 1. Study design.

In terms of benefits to the caregivers, all but two reported Before, I felt really annoyed and I used to slap him. Now

feeling less worried and more optimistic about their child’s I feel good. I feel that if I continue in this way, he will be

problems. They were happy with their increased competence, able to eat like other children.

being able to feed their child in more normal and convenient

Twelve caregivers reported positive changes in the attitude

ways (e.g. sitting up) and in their child’s improved feeding

and behaviour of other family members towards the child or

abilities. Comments illustrating this include the following:

caregiver. One mother commented:

Because I’ve been through the training I know how to

They are more interested in her and take her on their lap

feed her and how much to feed her . . . and I’m happy and

more because they see she is less sick now and more lively

she’s happy . . . we’re both happy.

because of the training.

I feel good because my child has stopped vomiting when

he eats because you advised me to sit my child up for feeding.

And now he has less fever as a result and I feel good. Discussion

I feel good because now when we’re having our food he A comparison of the results with those from other studies

asks for food – and that makes me feel good. (Reilly & Skuse 1992; Reilly et al. 1996; Sullivan et al. 2000)

revealed that the issues for children with feeding difficulties and

There was also a reduction in the number of complaints

their caregivers are universal. However, in situations of poverty,

about feeding taking a long time and there was a marked

problems are exacerbated by factors such as lack of resources to

decrease in the number of negative feelings expressed towards

buy nutritious food, limited time and facilities for cooking

the children during feeding (from 50 to 28 in total), as reflected

special recipes and the lack of access to rehabilitation and health

in the following statements:

services to deal with associated complications. Further prob-

Before I felt annoyed and angry during mealtimes lems arise for individuals living in a hot climate such as in

but now I feel that if I feed my child in the new way, Bangladesh, where the risk of dehydration is high, and in slums,

slowly he will improve. I don’t feel annoyed or angry where infection, especially gastrointestinal and respiratory, is

anymore. common.

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

Management of feeding difficulties in Bangladesh 7

Table 3. Quantitative outcomes of the intervention

Baseline Follow-up (second review)

Children (n = 22)

Chest health n n P-value

Frequency of chest-related illness occurring at least once every 3 months 15 6 0.005

Nutritional status Mean Mean P-value

Mean WAZ (Cole et al. 1998) -4.83 (SD 1.84) -4.07 (SD 2.45) 0.02

MUAC raw scores (cm) 14.75 (SD 1.41) 15.46 (SD 1.57) 0.001

Fluid intake Mean Mean P-value

Mean intake through drinks (mL) 173.7 (SD 107.48) 300.2 (SD 218.33) <0.01

Child affect during feeding n n P-value

Discomfort/distress during feeding – observed

Distressed mostly 3 0 0.06

Sometimes/occasionally 2 0

Discomfort mostly 1 2

Sometimes/occasionally 8 6

Neither 8 13

Fussiness – reported yes/no 14 6 0.005

Food refusal – reported

Always 9 1 0.003

Sometimes 12 15

Never 1 6

Child feeding skills n n P-value

Maturity of oral feeding manner – observed number munching or chewing 6 18 <0.001

Involvement in self-feeding – observed yes/no 0 6 0.02

Additional benefits n n P-value

General mood – reported number with predominantly negative mood 15 2 <0.001

Caregivers

Stress n n P-value

Stress regarding feeding – reported

Very 18 2 <0.001

Somewhat 4 2

A little 0 5

Not at all 0 13

Time spent feeding (n = 16) n n P-value

Observed >30 min per meal 0 3 0.005

Reported >30 min per meal 14 6 0.005

WAZ, weight-for-age; MUAC, mid-upper-arm circumference.

Nonetheless, this study has shown positive outcomes in a reduce the amount of time the mother spends caring for the

number of child and maternal variables, including (1) a child, as well as reduce the resources needed for medical con-

marked reduction in the risk of aspiration during feeding and sultations and medication. This low-cost intervention is there-

the number of chest-related illnesses; (2) improved or main- fore anticipated to have additional benefits in these very poor

tained nutritional status in 13 children; (3) a noticeable households, both in terms of increased carer availability for

increase in child cooperation during mealtimes and overall other members of the family as well as available financial

mood; (4) a marked reduction in caregiver stress regarding resources.

their child’s feeding difficulties; and (5) a clear reduction in Despite improvements in dietary intake and successful

distress experienced by the child and caregiver during meal- feeding, it should be noted that improvements in growth were

times. The outcomes of this low-cost, easily replicable inter- modest and inconsistent. The maintenance of growth trajecto-

vention therefore have important implications for countries ries alone is a huge challenge in this population (Gisel et al.

with limited resources. 2003) and catch-up growth is hampered by the physical inability

While this study concentrated on the mother–child dyad, it is to ingest sufficient calories (Gisel & Patrick 1988). According to

anticipated that the improved health experienced by the child Gisel and Patrick (1988), in order to compensate for the poten-

with CP due to improved carer feeding practices would, in turn, tial detrimental effect of oromotor dysfunction on nutritional

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

8 M.S. Adams et al.

Pre-training Post-training

Figure 2. Child–caregiver pairs pre- and post-training. The photographs show children and their caregiver at their baseline assessment (column 1), and

at follow-up (column 2).

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

Management of feeding difficulties in Bangladesh 9

intake, daily feeding times would need to be longer than normal ability and can impact significantly on child health as well as

waking hours. Fluid intake in the current study, which remained child and caregiver well-being.

severely inadequate, was likely to have been restricted by physi-

cal limitations, in the same way.

The calorific content of the food for this population there- Key messages

fore needs to be much higher in order to compensate.

However, special diets are difficult to provide as they are • Children with moderate–severe cerebral palsy frequently

expensive and require extra cooking time. This is a particular experience extreme difficulties with eating and drinking,

problem for poor families who often share stoves with other which if not managed, result in stressful mealtimes,

families and where caregivers are already short of time. chronic malnutrition, respiratory disease, reduced quality

According to Brown and colleagues (1993), to close the energy of life for caregiver and child, and early death.

gap would cost 8% of the parents’ daily wage for a normally • Significant improvements to child health and child–

developing Bangladeshi child. The cost is likely to be higher to caregiver well-being can be achieved after a minimum of

breech the gap for disabled children who are more severely four low-cost training sessions.

malnourished. Karim and colleagues (2005) showed that • Advocacy is urgently required to increase awareness and

powdered micronutrient mixes would amount to a fraction support among governments, health service commission-

of the cost of buying additional fresh foods required to ers and health providers at all levels, regarding the needs of

meet the micronutrient gap for malnourished children in children with disabilities and feeding difficulties and their

Bangladesh. They add that the bulk of fresh food necessary caregivers, in order for services to be made available.

would exceed the intake capacity of young children. This is, • The assessment of growth and growth monitoring should

of course, is greatly exacerbated in children with feeding always coexist alongside training on the management of

difficulties. feeding difficulties.

Ultimately, a combination of caregiver education and food • Research is urgently needed to investigate the appropriate-

supplementation is likely to provide a better opportunity ness, effectiveness and sustainability of providing locally

for greater catch-up growth as, even in non-disabled Bang- produced food supplements to this population, in addi-

ladeshi children, a combination of dietary education and food tion to education on diet.

supplementation has been found to be more effective than

caregiver education alone (Roy et al. 2005). This needs to be

investigated along with the possibility of access to free supple-

mentation. Free supplements are often available to non- Conflict of interest statement

disabled children through mainstream services in countries

The authors declare that the submitted work and its essential

such as Bangladesh. However, children with disabilities do not

substance have not previously been published and are not being

access these services either because of lack of awareness of the

considered for publication elsewhere. They also declare that the

need for their inclusion or because of the fact that nutrition

work being submitted is their own and that copyright has not

units target those suffering from diarrhoeal disease only. This

been breached in seeking its publication. They confirm that the

is a shortfall which violates the rights of the disabled and

funder had no involvement in the study design, data collection

which should be addressed by policy makers as a matter of

and analysis, and manuscript preparation.

urgency.

The study has a number of limitations, most importantly,

that of small sample size because of logistical constraints, with

Acknowledgements

additional losses at follow-up. Ethical considerations also meant

that a conventional non-treatment control could not be The authors gratefully acknowledge a grant from Citycell

employed. Nevertheless, the comparison of the trained group mobile phone company, Dhaka, which funded the fieldwork

and the advice only group was highly significant as were other component of this study, support from the Centre for the Reha-

results in the study and detailed data collection on each child– bilitation of the Paralysed, Savar, and contributions from staff at

caregiver pair provided valuable information. The study does the Child Neurology and Development Unit, Dhaka Shishu

demonstrate clearly that changes in feeding practices alone can Hospital, including Dr Das Kumar Uzzal, Dilara Begum, Shelina

make a dramatic difference to child cooperation and feeding Akhter, Yasmin Tanaka and Sheikh Zadi Rezina. The authors are

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

10 M.S. Adams et al.

also grateful to Dr Aisha Yousafzai, for her assistance in the supplements: a case study from the Bangladesh Integrated

original design of the study and to Carlos Grijalva-Eternod, for Nutrition Project. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 23,

his assistance in the analysis of the anthropometric data. 369–376.

Khan, N. Z., Ferdous, S., Munir, S., Huq, S. & McConachie, H. (1998)

Mortality of urban and rural young children with cerebral palsy in

References Bangladesh. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 40,

749–753.

BBS/UNICEF (2007) Child and Mother Nutrition Survey 2005. Larnert, G. & Ekberg, O. (1995) Positioning improves the oral and

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and UNICEF, Dhaka, Bangladesh. pharyngeal swallowing function in children with cerebral palsy.

Available at: http://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/Child_and_ Acta Paediatrica, 84, 689–692.

Mother_Nutrition_Survey.pdf (last accessed 2 October 2011). Mari, J. J. & Williams, P. (1985) A comparison of the validity of two

Black, M. M. (1999) Commentary: Feeding problems: an ecological psychiatric screening questionnaires (GHQ-12 and SRQ-20) in

perspective. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 24, 217–219. Brazil, using Relative Operating Characteristic (OC) analysis.

Brown, L. V., Rogers, B. L., Zeitlin, M. F., Gershoff, S. N., Huq, N. & Psychological Medicine, 15, 651–659.

Peterson, K. E. (1993) Comparison of the costs of compliance with Mobarak, R., Khan, N. Z., Munir, S., Zaman, S. S. & McConachie, H.

nutrition education messages to improve the diets of Bangladeshi (2000) Predictors of stress in mothers of children with cerebral

breastfeeding mothers and weaning-age children. Ecology of Food palsy in Bangladesh. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 25, 427–433.

and Nutrition, 30, 99–126. Moore, A. C., Akhtar, S. & Aboud, F. E. (2006) Responsive

Cohen, J. (1960) Coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. complementary feeding in rural Bangladesh. Social Science &

Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46. Medicine, 62, 1917–1930.

Cole, T. J., Freeman, J. V. & Preece, M. A. (1998) British 1990 growth Packer, B. (1995) Appropriate Paper-Based Technology (APT). A

reference centiles for weight, height, body mass index and head Manual. Intermediate Technology Publications, Rugby, UK.

circumference fitted by maximum penalized likelihood. Statistics in Palisano, R., Rosenbaum, P., Walter, S., Russell, D., Wood, E. &

Medicine, 17, 407–429. Galuppi, B. (1997) Development and reliability of a system to

Engle, P. (2000) Responsive feeding practices. Health Child Dialogue, classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy.

20, 5–6. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 39, 214–223.

Fleiss, J. L. (1981) Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. Wiley, Reddihough, D. S., Baikie, G. & Walstab, J. E. (2001) Cerebral palsy

New York, NY, USA. in Victoria, Australia: mortality and causes of death. Journal of

Gisel, E. G. & Patrick, J. (1988) Identification of children with Paediatrics and Child Health, 37, 183–186.

cerebral palsy unable to maintain a normal nutritional state. Reilly, S. & Skuse, D. (1992) Characteristics and management of

Lancet, 1, 283–286. feeding problems of young children with cerebral palsy.

Gisel, E. G., Tessier, M. J., Lapierre, G., Seidman, E., Drouin, E. & Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 34, 379–388.

Filion, G. (2003) Feeding management of children with severe Reilly, S., Skuse, D. & Poblete, X. (1996) Prevalence of feeding

cerebral palsy and eating impairment: an exploratory study. problems and oral motor dysfunction in children with cerebral

Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 23, 19–44. palsy: a community survey. Journal of Pediatrics, 129, 877–882.

Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Rogers, B., Arvedson, J., Buck, G., Smart, P. & Msall, M. (1994)

Theory. Aldine Publishing, Hawthorne, NY, USA. Characteristics of dysphagia in children with cerebral palsy.

Haberfellner, H., Schwartz, S. & Gisel, E. G. (2001) Feeding skills and Dysphagia, 9, 69–73.

growth after one year of intraoral appliance therapy in moderately Roy, S. K., Fuchs, G. J., Mahmud, Z., Ara, G., Islam, S., Shafique, S.,

dysphagic children with cerebral palsy. Dysphagia, 16, 83–96. Akter, S. S. & Chakraborty, B. (2005) Intensive nutrition education

Harding, T. W., de Arango, M. V., Baltazar, J., Climent, C. E., Ibrahim, with or without supplementary feeding improves the nutritional

H. H., Ladrido-Ignacio, L. & Wig, N. N. (1980) Mental disorders in status of moderately-malnourished children in Bangladesh. Journal

primary health care: a study of their frequency and diagnosis in of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 23, 320–330.

four developing countries. Psychological Medicine, 10, 231–241. Selley, W. G., Parrott, L. C., Lethbridge, P. C., Flack, F. C., Ellis, R. E.,

Hurley, K. M., Black, M. M., Papas, M. A. & Caulfield, L. E. (2008) Johnston, K. J., Foumeny, M. A. & Tripp, J. H. (2001) Objective

Maternal symptoms of stress, depression and anxiety are related measures of dysphagia complexity in children related to suckle

to non-responsive feeding styles in a statewide sample of WIC feeding histories, gestational ages, and classification of their

participants. The Journal of Nutrition, 138, 799–805. cerebral palsy. Dysphagia, 16, 200–207.

Johnson, C. B. & Deitz, J. C. (1985) Time use of mothers with Socrates, C., Grantham-McGregor, S. M. & Harknett, S. A. J. (2000)

preschool children: a study. The American Journal of Occupational Poor nutrition is a serious problem in children with cerebral palsy

Therapy, 39, 578–583. in Palawan, the Philippines. The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical

Karim, R., Desplats, G., Schaetzel, T., Ahmed, F., Salamatullah, Q., Medicine and Public Health, 28, 50–68.

Shahjahan, M., Akhteruzzaman, M. & Levinson, J. (2005) Seeking Stanley, F. J., Blair, E. & Alberman, E. (2000) Cerebral Palsies:

optimal means to address micronutrient deficiencies in food Epidemiology and Causal Pathways. Mac Keith Press, London, UK.

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

Management of feeding difficulties in Bangladesh 11

Sullivan, P. B. & Rosenbloom, L. (1996) Feeding the Disabled Child. N. & Thomas, A. G. (2005) Gastrostomy tube feeding

Mac Keith Press (Cambridge University Press), UK. in children with cerebral palsy: a prospective, longitudinal

Sullivan, P. B., Lambert, B., Rose, M., Ford-Adams, M., Johnson, A. & study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 47,

Griffiths, P. (2000) Prevalence and severity of feeding and 77–85.

nutritional problems in children with neurological impairment: Trier, E. & Thomas, A. G. (1998) Feeding the disabled child.

Oxford Feeding Study. Developmental Medicine and Child Nutrition, 14, 801–805.

Neurology, 42, 674–680. Waterman, E. T., Koltai, P. J., Downey, J. C. & Cacace, A. T. (1992)

Sullivan, P. B., Juszczak, E., Lambert, B. R., Rose, M., Ford-Adams, Swallowing disorders in a population of children with cerebral

M. E. & Johnson, A. (2002) Impact of feeding problems on palsy. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 24,

nutritional intake and growth: Oxford Feeding Study II. 63–71.

Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 44, 461–467. West, J. F. & Redstone, F. (2004) Alignment during feeding and

Sullivan, P. B., Juszczak, E., Bachlet, A. M., Thomas, A. G., Lambert, swallowing: does it matter? A review. Perceptual and Motor Skills,

B., Vernon-Roberts, A., Grant, H. W., Eltumi, M., Alder, N. & 98, 349–358.

Jenkinson, C. (2004) Impact of gastrostomy tube feeding on Yousafzai, A. K., Filteau, S. M., Wirz, S. L. & Cole, T. J. (2003)

the quality of life of carers of children with cerebral palsy. Comparison of armspan, arm length and tibia length as predictors

Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 46, 796–800. of actual height of disabled and non-disabled children in Dharavi,

Sullivan, P. B., Juszczak, E., Bachlet, A. M., Lambert, B., Mumbai, India. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57,

Vernon-Roberts, A., Grant, H. W., Eltumi, M., McLean, L., Alder, 1230–1234.

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Child: care, health and development

You might also like

- The Path of Ascension Book 1 Final Edit - TM1 DONEDocument470 pagesThe Path of Ascension Book 1 Final Edit - TM1 DONELeonardo Cruz Garcia100% (1)

- Fire Risk Assessment-Rev 001Document5 pagesFire Risk Assessment-Rev 001ramodNo ratings yet

- Angel of GroznyDocument348 pagesAngel of GroznySportyANK100% (1)

- Jurnal Vol 1 No 1Document58 pagesJurnal Vol 1 No 1bodiwenNo ratings yet

- s12966 019 0798 1Document15 pagess12966 019 0798 1hey rizkiNo ratings yet

- Literature PHDocument4 pagesLiterature PHNoel KalagilaNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Community-Based Nutrition Education On The Nutrition Status of Under-Five Children in Developing Countries. A Systematic ReviewDocument4 pagesThe Effectiveness of Community-Based Nutrition Education On The Nutrition Status of Under-Five Children in Developing Countries. A Systematic ReviewDesy rianitaNo ratings yet

- Muhoozi 2017Document11 pagesMuhoozi 2017Dewi PrasetiaNo ratings yet

- 2007 FoodNutrBull 375 RoySKDocument9 pages2007 FoodNutrBull 375 RoySKhafsatsaniibrahimmlfNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667268522000092 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S2667268522000092 MainveraNo ratings yet

- The Role of Schools in Preventing Childhood ObesityDocument4 pagesThe Role of Schools in Preventing Childhood ObesityEMMANUELNo ratings yet

- Feeding ArvedsonDocument10 pagesFeeding ArvedsonPablo Oyarzún Dubó100% (1)

- Situational Analysis of Nutritional Status Among 1989 Children Presenting With Cleft Lip Palate in IndonesiaDocument13 pagesSituational Analysis of Nutritional Status Among 1989 Children Presenting With Cleft Lip Palate in Indonesiacvdk8dc8sbNo ratings yet

- Effective Interventions To Address Maternal and Child Malnutrition: An Update of The EvidenceDocument18 pagesEffective Interventions To Address Maternal and Child Malnutrition: An Update of The EvidenceChris ValNo ratings yet

- Contextual Effect of "Posyandu" in The Incidence of Anemia in Children Under FiveDocument10 pagesContextual Effect of "Posyandu" in The Incidence of Anemia in Children Under FiveEgy SunandaNo ratings yet

- Research ReportDocument8 pagesResearch ReportAbid SherazNo ratings yet

- Assess The Effect of Nutritional Status, Food Consumption, Physical Activity Among School ChildrenDocument5 pagesAssess The Effect of Nutritional Status, Food Consumption, Physical Activity Among School ChildrenInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The First 1000 Days: A Critical Period of Nutritional Opportunity and VulnerabilityDocument3 pagesThe First 1000 Days: A Critical Period of Nutritional Opportunity and VulnerabilityEffika YuliaNo ratings yet

- Wong 2014Document10 pagesWong 2014eka wahyuni wahyuniNo ratings yet

- Clinical Nutrition: Feeding Difficulties in Children With Inherited Metabolic Disorders: A Pilot StudyDocument9 pagesClinical Nutrition: Feeding Difficulties in Children With Inherited Metabolic Disorders: A Pilot StudyGita Fajar WardhaniNo ratings yet

- Lectura Control 2 - Asignatura 3Document12 pagesLectura Control 2 - Asignatura 3CamilaGarridoNo ratings yet

- StuntingDocument9 pagesStuntingAnonymous q8VmTTtmXQNo ratings yet

- BMC Public Health: Irregular Breakfast Eating and Health Status Among Adolescents in TaiwanDocument7 pagesBMC Public Health: Irregular Breakfast Eating and Health Status Among Adolescents in TaiwanMiss LeslieNo ratings yet

- Seizure Disorders: School-Age Children and Adolescents 609Document30 pagesSeizure Disorders: School-Age Children and Adolescents 609Fahri GunawanNo ratings yet

- Bhutta Interventions LCAH 2021Document18 pagesBhutta Interventions LCAH 2021Angelica EstipularNo ratings yet

- NPT en PediatriaDocument22 pagesNPT en PediatriaFernanda Sanchez LozanoNo ratings yet

- 10 11648 J SJPH 20130102 12Document6 pages10 11648 J SJPH 20130102 12SukmaNo ratings yet

- Viewpoint Article: Childhood Obesity - Looking Back Over 50 Years To Begin To Look ForwardDocument5 pagesViewpoint Article: Childhood Obesity - Looking Back Over 50 Years To Begin To Look ForwardichalsajaNo ratings yet

- Neurodesarrollo y Reciperacion Despues de Desnutricion AgudaDocument10 pagesNeurodesarrollo y Reciperacion Despues de Desnutricion AgudaJesusMiguelCorneteroMendozaNo ratings yet

- Multilevel Intervention Model To Improve Nutrition of Mother and Children in Banyumas RegencyDocument9 pagesMultilevel Intervention Model To Improve Nutrition of Mother and Children in Banyumas RegencyVerawaty AwaludinNo ratings yet

- Sullivan, P 2010Document1 pageSullivan, P 2010Donna OhNo ratings yet

- Review (Lassi, 2020)Document21 pagesReview (Lassi, 2020)melody tuneNo ratings yet

- A Disseration Submitted As A Partial Fulfilment For Award of The Diploma in Community Nutrition.Document8 pagesA Disseration Submitted As A Partial Fulfilment For Award of The Diploma in Community Nutrition.Prince HakimNo ratings yet

- Mcpherson 2016Document11 pagesMcpherson 2016shafyd ramdanNo ratings yet

- An Interventional Study To Evaluate The Effectiveness of Selected Nutritional Diet On Growth of Pre Schooler at Selected Slums Area of Bhopal M.PDocument6 pagesAn Interventional Study To Evaluate The Effectiveness of Selected Nutritional Diet On Growth of Pre Schooler at Selected Slums Area of Bhopal M.PEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Healthcare: Nutritional Education Is An Effective Tool in Improving Beverage Assortment in Nurseries in PolandDocument13 pagesHealthcare: Nutritional Education Is An Effective Tool in Improving Beverage Assortment in Nurseries in PolandLa HusyainNo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding Is An Unsurpassed Method of Providing Ideal Food For The Healthy Growth and Development of InfantsDocument4 pagesBreastfeeding Is An Unsurpassed Method of Providing Ideal Food For The Healthy Growth and Development of InfantsSatra SabbuhNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 13 01712 v2Document21 pagesNutrients 13 01712 v2INFOKOM BPOMPALUNo ratings yet

- Dietary Inadequacy Is Associated With Anemia and Suboptimal Growth Among Preschool-Aged Children in Yunnan Province, ChinaDocument9 pagesDietary Inadequacy Is Associated With Anemia and Suboptimal Growth Among Preschool-Aged Children in Yunnan Province, ChinaDani KusumaNo ratings yet

- Developing and Implementing A Telehealth Enhanced Interdisciplinary Pediatric Feeding Disorders Clinic - A Program Description and EvaluationDocument18 pagesDeveloping and Implementing A Telehealth Enhanced Interdisciplinary Pediatric Feeding Disorders Clinic - A Program Description and EvaluationPaloma LópezNo ratings yet

- Child Eating Behaviors and Caregiver Feeding Practices in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument10 pagesChild Eating Behaviors and Caregiver Feeding Practices in Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderspedroNo ratings yet

- Poor Nutrition ProjectDocument60 pagesPoor Nutrition Projectaniamulu munachimNo ratings yet

- Stunted Growth RESEARCH PAPERDocument23 pagesStunted Growth RESEARCH PAPERRemelyn OcatNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document6 pagesChapter 1Geralden Vinluan PingolNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status of School Age Children in Private Elementary Schools: Basis For A Proposed Meal Management PlanDocument5 pagesNutritional Status of School Age Children in Private Elementary Schools: Basis For A Proposed Meal Management PlanIjaems JournalNo ratings yet

- Chapte 1 2 - Group 5 1Document19 pagesChapte 1 2 - Group 5 1arlenetacla12No ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0250562Document16 pagesJournal Pone 0250562addanaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Nutritional Supplementation During The - 2022 - The Lancet RegDocument11 pagesEffectiveness of Nutritional Supplementation During The - 2022 - The Lancet RegCawee CawNo ratings yet

- Healthy Eating and Obesity Prevention For Preschoolers: A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesHealthy Eating and Obesity Prevention For Preschoolers: A Randomised Controlled TrialRiftiani NurlailiNo ratings yet

- Revised Chapter 1 3Document26 pagesRevised Chapter 1 3Noel BarcelonNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 (Food Supplement)Document26 pagesCHAPTER 1 (Food Supplement)Noel BarcelonNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S0002916522010693-Main InterDocument8 pages1-S2.0-S0002916522010693-Main InterAlimah PutriNo ratings yet

- 2022 9 4 9 RavivDocument12 pages2022 9 4 9 RavivSome445GuyNo ratings yet

- Lipid Based Suppl Vs CSB Mod Underwt Malawi 2010Document14 pagesLipid Based Suppl Vs CSB Mod Underwt Malawi 2010Fiqah KasmiNo ratings yet

- Breast vs. Bottle: Differences in The Growth of Croatian InfantsDocument9 pagesBreast vs. Bottle: Differences in The Growth of Croatian InfantsBernadette Grace RetubadoNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Education Programs Aimed at African Mothers of Infant Children A Systematic ReviewDocument19 pagesNutrition Education Programs Aimed at African Mothers of Infant Children A Systematic ReviewDicky Estosius TariganNo ratings yet

- Estreñimiento y TeaDocument9 pagesEstreñimiento y TeaElena Martin LopezNo ratings yet

- DietaryDiversity Mahmudionoetal2017Document10 pagesDietaryDiversity Mahmudionoetal2017ainindyaNo ratings yet

- Sdarticle 142 PDFDocument1 pageSdarticle 142 PDFRio Michelle CorralesNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Under Nutrition Among School Age Children in A Nairobi Peri-Urban SlumDocument10 pagesDeterminants of Under Nutrition Among School Age Children in A Nairobi Peri-Urban SlumJean TanNo ratings yet

- Adv Nutr 2011 Sharma 207S 16SDocument10 pagesAdv Nutr 2011 Sharma 207S 16SAlbert Lawrence KwansaNo ratings yet

- Maternal and Pediatric Nutrition JournalDocument6 pagesMaternal and Pediatric Nutrition JournalStacey CruzNo ratings yet

- Building Future Health and Well-Being of Thriving Toddlers and Young Children: 95th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, September 2020From EverandBuilding Future Health and Well-Being of Thriving Toddlers and Young Children: 95th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, September 2020No ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document28 pagesLecture 3Lovely ZahraNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Illustrated Anatomy of The Head and Neck 5th by FehrenbachDocument8 pagesSolution Manual For Illustrated Anatomy of The Head and Neck 5th by FehrenbachxewazixNo ratings yet

- IUPAC NomenclatureDocument17 pagesIUPAC Nomenclaturesurya kant upadhyay100% (3)

- Be-Pdp-Fr-07-E Papso Form Roanoke To Sa - j7Document2 pagesBe-Pdp-Fr-07-E Papso Form Roanoke To Sa - j7Ricardo Frank CordeiroNo ratings yet

- Critical RatioDocument13 pagesCritical RatioFatiima Tuz ZahraNo ratings yet

- MI31004 Economics of Mining Enterprises ES 2018Document2 pagesMI31004 Economics of Mining Enterprises ES 2018Taurai MudzimuiremaNo ratings yet

- Viscosity-1 Viscometer-2 Relation Between Viscosity &temperature-3 Vogel Equation-4 Programming ofDocument71 pagesViscosity-1 Viscometer-2 Relation Between Viscosity &temperature-3 Vogel Equation-4 Programming ofDr_M_SolimanNo ratings yet

- My Dream Hotel: By. YeongseoDocument7 pagesMy Dream Hotel: By. YeongseoYoutube whiteNo ratings yet

- Engine Failure WGBDocument33 pagesEngine Failure WGBRohan SinhaNo ratings yet

- Figure 1: Schematic Diagram of A Tray Dryer. (Geankoplis, 2003)Document2 pagesFigure 1: Schematic Diagram of A Tray Dryer. (Geankoplis, 2003)Nesha Arasu0% (1)

- 2020 OWS InfographicsDocument1 page2020 OWS InfographicsElisha PaloNo ratings yet

- Living A Life of LordshipDocument52 pagesLiving A Life of Lordshipmung_khatNo ratings yet

- Makerere Research FormatDocument7 pagesMakerere Research FormatMurice ElaguNo ratings yet

- I. Work/Practice Exercise: Hussin, Shadimeer Reyes Bs Biology 2-CDocument3 pagesI. Work/Practice Exercise: Hussin, Shadimeer Reyes Bs Biology 2-CScar ShadowNo ratings yet

- Trouble Shooting in Vacuum PumpDocument12 pagesTrouble Shooting in Vacuum Pumpj172100% (1)

- P-Value (Definition, Formula, Table & Example)Document1 pageP-Value (Definition, Formula, Table & Example)Niño BuenoNo ratings yet

- Graphing Quadratic Functions in Standard Form Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesGraphing Quadratic Functions in Standard Form Lesson Planapi-401400552100% (1)

- Abs Wabco HabsDocument20 pagesAbs Wabco HabsBom_Jovi_681No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Solutions DetailedDocument30 pagesChapter 1 Solutions DetailedYeonjae JeongNo ratings yet

- Shock AmbossDocument40 pagesShock AmbossAshraf AlbhlaNo ratings yet

- Paste Copy FTTXDocument8 pagesPaste Copy FTTXfttxjpr JaipurNo ratings yet

- 04a. Quadratics - The Quadratic Formula and The DiscriminantDocument1 page04a. Quadratics - The Quadratic Formula and The Discriminantjingcong liuNo ratings yet

- English Eald s6 Sample Paper 1 Stimulus BookletDocument5 pagesEnglish Eald s6 Sample Paper 1 Stimulus BookletHouston ChantonNo ratings yet

- Beadwork - November 2015 PDFDocument84 pagesBeadwork - November 2015 PDFIoan Cristian Popescu100% (24)

- 3492 0022 01 - LDocument16 pages3492 0022 01 - LJoe SmithNo ratings yet

- Pe Module Q1Document21 pagesPe Module Q1alexanlousumanNo ratings yet

- Question Bank-Unit 2: MATH 2300Document8 pagesQuestion Bank-Unit 2: MATH 2300ROHAN TRIVEDI 20SCSE1180013No ratings yet