Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Green Belt

Green Belt

Uploaded by

Brenda GarcíaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Green Belt

Green Belt

Uploaded by

Brenda GarcíaCopyright:

Available Formats

GREEN BELT

A green belt is a policy and land-use zone designation used in land-use planning to retain areas of

largely undeveloped, wild, or agricultural land surrounding or neighboring urban areas. Similar

concepts are greenways or green wedges, which have a linear character and may run through an

urban area instead of around it. In essence, a green belt is an invisible line designating a border

around a certain area, preventing development of the area and allowing wildlife to return and be

established.

Contents

1Purposes

2History

3Criticism

o 3.1House prices

o 3.2Increasing urban sprawl

o 3.3United Kingdom

4Notable examples

o 4.1Australia

o 4.2Brazil

o 4.3Canada

o 4.4Dominican Republic

o 4.5Iran

o 4.6Europe

o 4.7New Zealand

o 4.8Thailand

o 4.9South Korea

o 4.10United Kingdom

o 4.11United States

5See also

6References

Purposes[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve

this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced

material may be challenged and removed. (May 2016) (Learn

how and when to remove this template message)

In those countries which have them, the stated objectives of green belt policy are to:

Protect natural or semi-natural environments;

Improve air quality within urban areas;[1][2]

Ensure that urban dwellers have access to countryside, with consequent educational

and recreational opportunities;

Protect the unique character of rural communities that might otherwise be absorbed by

expanding suburbs.[3]

The green belt has many benefits for people:

Walking, camping, and biking areas close to the cities and towns.

Contiguous habitat network for wild plants, animals and wildlife.[4]

Cleaner air and water[1][2]

Better land use of areas within the bordering cities.

The effectiveness of green belts differs depending on location and country. They can often be

eroded by urban rural fringe uses and sometimes, development 'jumps' over the green belt area,

resulting in the creation of "satellite towns" which, although separated from the city by green belt,

function more like suburbs than independent communities.

History[edit]

In the 7th century, Muhammad established a green belt around Medina. He did this by prohibiting

any further removal of trees in a 12-mile long strip around the city.[5] In 1580 Elizabeth I of

England banned new building in a 3-mile wide belt around the City of London in an attempt to stop

the spread of plague. However, this was not widely enforced and it was possible to buy

dispensations which reduced the effectiveness of the proclamation.[6]

In modern times, the term emerged from continental Europe where broad boulevards were

increasingly used to separate new development from the centre of historic towns; most notably

the Ringstraße in Vienna. Green belt policy was then pioneered in the United Kingdom confronted

with ongoing rural flight. The term itself was first used in relation to the growth of London by Octavia

Hill in 1875.[7][8] Various proposals were put forward from 1890 onwards but the first to garner

widespread support was put forward by the London Society in its "Development Plan of Greater

London" 1919. Alongside the CPRE they lobbied for a continuous belt (of up to two miles wide) to

prevent urban sprawl, beyond which new development could occur.

The green belt around the city of York, in England

There are fourteen green belt areas in the UK covering 16,716 km² or 13% of England, and 164 km²

of Scotland; for a detailed discussion of these, see Green belt (UK). Other notable examples are

the Ottawa Greenbelt and Golden Horseshoe Greenbelt[9] in Ontario, Canada. Ottawa's 20,350-

hectare (78.6 sq mi) instance is managed by the National Capital Commission (NCC).[10] The more

general term in the United States is green space or greenspace, which may be a very small area

such as a park.

The dynamic Adelaide Park Lands, measuring approximately 7.6 km² surround, unbroken, the city

centre of Adelaide. On the fringe of the eastern suburbs, an expansive natural green belt in

the Adelaide Hills acts as a growth boundary for Adelaide and cools the city in the hottest months.

The concept of "green belt" has evolved in recent years to encompass not only "Greenspace" but

also "Greenstructure" which comprises all urban and peri-urban greenspaces, an important aspect of

sustainable development in the 21st century. The European Commission's COST Action

C11 (COST – European Cooperation in Science and Technology) is undertaking "Case studies in

Greenstructure Planning" involving 15 European countries.

An act of the Swedish parliament from 1994 has declared a series of parks in Stockholm and the

adjacent municipality of Solna to its north a "national city park" called Royal National City Park.

Criticism[edit]

House prices[edit]

When paired with a city which is economically prospering, homes in a green belt may have been

motivated by or result in considerable premiums. They may also be more economically resilient as

popular among the retired and less attractive for short-term renting of modest homes.[11] Where in the

city itself demand exceeds supply in housing, green belt homes compete directly with much city

housing wherever such green belt homes are well-connected to the city.[11] Further, they in all cases

attract a future-guaranteed premium for protection of their views, recreational space and for the

preservation/conservation value itself.[11] Most also benefit from higher rates of

urban gardening and farming, particularly when done in a community setting, which have positive

effects on nutrition, fitness, self-esteem, and happiness, providing a benefit for both physical and

mental health, in all cases easily provided or accessed in a green belt.[12] Government planners also

seek to protect the green belt as its local farmers are engaged in peri-urban agriculture which

augments carbon sequestration, reduces the urban heat island effect, and provides

a habitat for organisms.[13] Peri-urban agriculture may also help recycle urban greywater and other

products of wastewater, helping to conserve water and reduce waste.[14]

The housing market contrasts with more uncertainty and economic liberalism inside and immediately

outside of the belt:[11] green belt homes have by definition nearby protected landscapes.[11] Local

residents in affluent parts of a green belt, as in parts of the city, can be assured of preserving any

localized bourgeois status quo present and so assuming the green belt is not from the outset an

area of more social housing proportionately than the city, it naturally tends toward greater economic

wealth. In a protracted housing shortage, reduction of the green belt is one of the possible solutions.

All such solutions may be resisted however by private landlords who profit from a scarcity of

housing, for example by lobbying to restrain new housing across the city. The stated motivation and

benefits of the green belt might be well-intentioned (public health, social gardening and agriculture,

environment), but inadequately realised relative to other solutions.

Inherently partial critics include Mark Pennington and the economics-heavy think tanks such as

the Institute of Economic Affairs who would see a reduction in many green belts. Such studies focus

on widely inherent limitations of green belts. In most examples only a small fraction of the population

uses the green belt for leisure purposes. The IEA study claims that a green belt is not strongly

causally linked to clean air and water. Rather, they view the ultimate result of the decision to green-

belt a city as one to prevent housing demand within the zone to be met with supply,[15] thus

exacerbating high housing prices and stifling competitive forces in general.

Increasing urban sprawl[edit]

Another area of criticism comes from the fact that, since a green belt does not extend indefinitely

outside a city, it spurs the growth of areas much further away from the city core than if it had not

existed, thereby actually increasing urban sprawl.[16] Examples commonly cited are

the Ottawa suburbs of Kanata and Orleans, both of which are outside the city's green belt, and are

currently undergoing explosive growth (see Greenbelt (Ottawa)). This leads to other problems, as

residents of these areas have a longer commute to work places in the city and worse access

to public transport. It also means people have to commute through the green belt, an area not

designed to cope with high levels of transportation. Not only is the merit of a green belt subverted,

but the green belt may heighten the problem and make the city unsustainable.

There are many examples whereby the actual effect of green belts is to act as a land reserve for

future freeways and other highways. Examples include sections of Ontario Highway 407 north

of Toronto and the Hunt Club Road and Richmond Road south of Ottawa. Whether they are

originally planned as such, or the result of a newer administration taking advantage of land that was

left available by its predecessors is debatable.

You might also like

- The Saturn Time Cube SimulationDocument67 pagesThe Saturn Time Cube Simulationtriple7inc100% (3)

- Green Infrastructure Planning GuideDocument45 pagesGreen Infrastructure Planning Guideshakeelnadaf100% (3)

- Principles of Brownfield Regeneration: Cleanup, Design, and Reuse of Derelict LandFrom EverandPrinciples of Brownfield Regeneration: Cleanup, Design, and Reuse of Derelict LandNo ratings yet

- EU Guidelines Green InfrastructureDocument4 pagesEU Guidelines Green InfrastructureNeven TrencNo ratings yet

- Technical Note Guidance On Corrosion Assessment of Ex EquipmentDocument7 pagesTechnical Note Guidance On Corrosion Assessment of Ex EquipmentParthiban NagarajanNo ratings yet

- Clinical Assessment of Child and Adolescent Intelligence - Randy W Kamphaus PDFDocument685 pagesClinical Assessment of Child and Adolescent Intelligence - Randy W Kamphaus PDFCamilo Suárez100% (1)

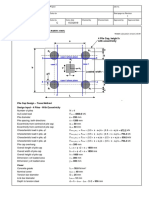

- 4 Piles Cap With Eccentricity ExampleDocument3 pages4 Piles Cap With Eccentricity ExampleSousei No Keroberos100% (1)

- Green Belt ProjectDocument5 pagesGreen Belt ProjectIeva ValpētereNo ratings yet

- Green BeltDocument5 pagesGreen BeltRemya R. KumarNo ratings yet

- 4 Guidelines - Redevloping - Greenbelts of JharkhandDocument3 pages4 Guidelines - Redevloping - Greenbelts of JharkhandDr Raju EVRNo ratings yet

- Potentials of Creating Pocket Parks in High Density Residential Neighborhoods: The Case of Rod El Farag, Cairo CityDocument20 pagesPotentials of Creating Pocket Parks in High Density Residential Neighborhoods: The Case of Rod El Farag, Cairo CityGreen100% (1)

- Green City: Town Planning (Nar-804) Semester ViiiDocument60 pagesGreen City: Town Planning (Nar-804) Semester ViiiAr Siddharth AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Environmental Challenges of Urbanization - A Case Study For Open Green Space ManagementDocument6 pagesEnvironmental Challenges of Urbanization - A Case Study For Open Green Space ManagementNatinael AbrhamNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Greenbelt DesignDocument19 pagesApproaches To Greenbelt DesignTarun jajuaNo ratings yet

- PAPER 2 Cognitive Question Cards P2Document5 pagesPAPER 2 Cognitive Question Cards P2Mary Ann MaherNo ratings yet

- Ecological FootprintDocument17 pagesEcological Footprintmanishabajpayee19No ratings yet

- Sustainable Design - Ecology, PDFDocument45 pagesSustainable Design - Ecology, PDFtaoNo ratings yet

- Office of The State ComptrollerDocument20 pagesOffice of The State Comptrollerjon_wnbzNo ratings yet

- Garden City ConceptDocument8 pagesGarden City ConceptMuhd SamhanNo ratings yet

- ASI PlanninginafreesocietyDocument11 pagesASI PlanninginafreesocietyCharlesOJNo ratings yet

- By E-Mail Only: Natural England Consultation Service Hornbeam House Electra Way Crewe Business Park Crewe Cw1 6GjDocument7 pagesBy E-Mail Only: Natural England Consultation Service Hornbeam House Electra Way Crewe Business Park Crewe Cw1 6GjMohammed Fathy AhmedNo ratings yet

- L03 Ecological PlanningDocument31 pagesL03 Ecological PlanningYohans EjiguNo ratings yet

- Examples of Environmental Plans Are:: Public Open Space (POS)Document3 pagesExamples of Environmental Plans Are:: Public Open Space (POS)Nathan BerhanuNo ratings yet

- Sustainable ArchitectureDocument47 pagesSustainable ArchitecturePavithravasuNo ratings yet

- Greenbelts: The Importance of Greenbelts in Urban AreasDocument1 pageGreenbelts: The Importance of Greenbelts in Urban AreasPREETHI M ANo ratings yet

- Urban Growth Management Best Practices Towards Implications For The Developing WorldDocument16 pagesUrban Growth Management Best Practices Towards Implications For The Developing WorldBenjamin L SaitluangaNo ratings yet

- North East Green Infrastructure Planning GuideDocument46 pagesNorth East Green Infrastructure Planning GuideShemeles MitkieNo ratings yet

- SDG NO. (11) Sustainable Cities and CommunitiesDocument15 pagesSDG NO. (11) Sustainable Cities and CommunitiesMUHAMMAD IFTIKHAR UD DINNo ratings yet

- Sanitary LandfillDocument5 pagesSanitary LandfillAnonymous 7J96P4ANNo ratings yet

- Landscape Urbanisim 1Document3 pagesLandscape Urbanisim 1Lakshana AdityanNo ratings yet

- Disposal of Solid WastesDocument9 pagesDisposal of Solid WastesBhaskar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Unit V - Sustainable CitiesDocument15 pagesUnit V - Sustainable CitiesPrabha Karen PalanisamyNo ratings yet

- 土木工程拓展署 綠化總綱圖Document33 pages土木工程拓展署 綠化總綱圖Albert 'Siu Yin' TsangNo ratings yet

- Wind Comfort in A Public Urban Space-Case Study Within Dublin DocklandsDocument17 pagesWind Comfort in A Public Urban Space-Case Study Within Dublin DocklandsMonaNo ratings yet

- Greening SCTEX Primer 09Document3 pagesGreening SCTEX Primer 09Jiggy MadrigalNo ratings yet

- Toward Permanent ParadiseDocument6 pagesToward Permanent ParadiseRich BrasherNo ratings yet

- Green Infrastructure: Concepts, Types & BenefitsDocument8 pagesGreen Infrastructure: Concepts, Types & BenefitsAshique V.V100% (1)

- Module-5-Environmental ScienceDocument4 pagesModule-5-Environmental ScienceAngel Gail Sornido BayaNo ratings yet

- Reference Green Blue Infrastructure Guidelines Feb17Document76 pagesReference Green Blue Infrastructure Guidelines Feb17ssajith123No ratings yet

- Green Space Depletion: DefinitionDocument2 pagesGreen Space Depletion: DefinitionBelle LaiNo ratings yet

- 4 Sustainable Planning Concepts at The Beginning of 21stDocument48 pages4 Sustainable Planning Concepts at The Beginning of 21stNeha SardaNo ratings yet

- Land Use Planning GROUP3Document6 pagesLand Use Planning GROUP3Mary Joy AzonNo ratings yet

- Waste Management - Wikipedia PDFDocument64 pagesWaste Management - Wikipedia PDFSanjib SarkarNo ratings yet

- Natres Finals 5Document24 pagesNatres Finals 5Janette TitoNo ratings yet

- Toronto Has Grown Into A ConurbationDocument5 pagesToronto Has Grown Into A ConurbationTreasure's TreasureNo ratings yet

- Components and Patterns of Urban Areas and Green InfrastructureDocument40 pagesComponents and Patterns of Urban Areas and Green InfrastructureFiraol NigussieNo ratings yet

- Planning Theory-2019Document23 pagesPlanning Theory-2019Sanjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Green Cover and Green CompositesDocument33 pagesGreen Cover and Green CompositesvermadeenNo ratings yet

- A Greener LondonDocument36 pagesA Greener LondonMatt Mace100% (1)

- Highway BeautificationDocument14 pagesHighway BeautificationKim GonocruzNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 12 07229 v2Document24 pagesSustainability 12 07229 v2danielNo ratings yet

- Pyramid City: Promoted by IP Direct Group October 2008Document30 pagesPyramid City: Promoted by IP Direct Group October 2008Shashank JainNo ratings yet

- SDP16031FU1Document11 pagesSDP16031FU1YEGAR SAHADUTA HEBZIBAH K 08211942000015No ratings yet

- Greencity1 170414084107Document10 pagesGreencity1 170414084107Bobinder chauhanNo ratings yet

- Agriculture: Sustainability of Urban Agriculture: Vegetable Production On Green RoofsDocument16 pagesAgriculture: Sustainability of Urban Agriculture: Vegetable Production On Green RoofsSakinah Rahma WardaniNo ratings yet

- An Urban Greening Action Plan To Foster Sustainable Development of South CitiesDocument33 pagesAn Urban Greening Action Plan To Foster Sustainable Development of South Citieskako2006No ratings yet

- Module 3 (Government Land Management Activities)Document9 pagesModule 3 (Government Land Management Activities)7-Idiots Future EngineersNo ratings yet

- English Heritage RisksDocument18 pagesEnglish Heritage RisksMateoNo ratings yet

- A Place For SuDS OnlineDocument40 pagesA Place For SuDS OnlinepaularupNo ratings yet

- CJS Focus On Urban GreenspaceDocument9 pagesCJS Focus On Urban GreenspaceCountrysideJobsNo ratings yet

- Greening South East Asian Capital CitiesDocument14 pagesGreening South East Asian Capital CitiesMuhammad HafidNo ratings yet

- Effective Management and Preservation of Grassland WoodlandsFrom EverandEffective Management and Preservation of Grassland WoodlandsNo ratings yet

- ToR For Individual Film Makers On LTADocument6 pagesToR For Individual Film Makers On LTARoshil VermaNo ratings yet

- The Kinston Waterfront Now!Document46 pagesThe Kinston Waterfront Now!Kofi BooneNo ratings yet

- Activities Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Step 5 - Final Assessment - Open Objective TestDocument9 pagesActivities Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Step 5 - Final Assessment - Open Objective TestWendy JaramilloNo ratings yet

- NEWS ARTICLE and SHOT LIST-Head of ATMIS Joins Ugandan Nationals in Somalia To Mark 61st Independence DayDocument5 pagesNEWS ARTICLE and SHOT LIST-Head of ATMIS Joins Ugandan Nationals in Somalia To Mark 61st Independence DayAMISOM Public Information ServicesNo ratings yet

- Transformer T1Document1 pageTransformer T1Vikash TiwariNo ratings yet

- Activity 3.module 1Document4 pagesActivity 3.module 1Juedy Lala PostreroNo ratings yet

- Manual Del Gemcom Surpac - Underground Ring DesignDocument43 pagesManual Del Gemcom Surpac - Underground Ring DesignDavid GarciaNo ratings yet

- BODIES BODIES BodiesDocument92 pagesBODIES BODIES BodiesNatalia Romero MedinaNo ratings yet

- Ep English Teachers GuideDocument180 pagesEp English Teachers GuideJessy ChrisNo ratings yet

- Bermundo Task 3 Iii-20Document2 pagesBermundo Task 3 Iii-20Jakeson Ranit BermundoNo ratings yet

- Washing MachineDocument6 pagesWashing MachineianNo ratings yet

- DD 20MDocument5 pagesDD 20Mlian9358No ratings yet

- Thesis Ethical HackingDocument6 pagesThesis Ethical Hackingshannonsandbillings100% (2)

- Num MethodsDocument160 pagesNum Methodsnoreply_t2350% (1)

- Sop-10 Dose Rate MeasurementDocument3 pagesSop-10 Dose Rate MeasurementOSAMANo ratings yet

- Shady Othman Nour El Deen: Doha, QatarDocument3 pagesShady Othman Nour El Deen: Doha, QatarHatem HusseinNo ratings yet

- Strad Pressenda v3Document6 pagesStrad Pressenda v3Marcos Augusto SilvaNo ratings yet

- Base Institute - Namakkal - PH: 900 37 111 66: - Mock - Ibpsguide.in - 1Document288 pagesBase Institute - Namakkal - PH: 900 37 111 66: - Mock - Ibpsguide.in - 1Kartik MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Training Regulations: Shielded Metal Arc Welding (Smaw) NC IiDocument61 pagesTraining Regulations: Shielded Metal Arc Welding (Smaw) NC IiKentDemeterio100% (2)

- List - Parts of Bahay Na Bato - Filipiniana 101Document7 pagesList - Parts of Bahay Na Bato - Filipiniana 101Eriellynn Liza100% (1)

- Executing / Implementing Agency: Financial Management Assessment Questionnaire Topic ResponseDocument6 pagesExecuting / Implementing Agency: Financial Management Assessment Questionnaire Topic ResponseBelle CartagenaNo ratings yet

- EDUC 3 Module 1-Lesson 1Document12 pagesEDUC 3 Module 1-Lesson 1Ma. Kristel OrbocNo ratings yet

- On Intuitionistic Fuzzy Transportation Problem Using Pentagonal Intuitionistic Fuzzy Numbers Solved by Modi MethodDocument4 pagesOn Intuitionistic Fuzzy Transportation Problem Using Pentagonal Intuitionistic Fuzzy Numbers Solved by Modi MethodEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- DS PD Diagnostics System PD-TaD 62 BAURDocument4 pagesDS PD Diagnostics System PD-TaD 62 BAURAdhy Prastyo AfifudinNo ratings yet

- TDS 202 Dura ProofDocument2 pagesTDS 202 Dura ProofGhulam WaheedNo ratings yet

- Consumers, Producers, and The Efficiency of MarketsDocument43 pagesConsumers, Producers, and The Efficiency of MarketsRoland EmersonNo ratings yet