Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Metaphysical Poets-2

Metaphysical Poets-2

Uploaded by

Ádám LajtaiCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Paz, Octavio - The Double Flame (Harcourt, 1995)Document288 pagesPaz, Octavio - The Double Flame (Harcourt, 1995)Andres100% (7)

- Igitabo Cy'imishingaDocument191 pagesIgitabo Cy'imishingaDr. Sixbert SANGWA100% (1)

- Shiv Kumar Batalvi: Punjabi KavitaDocument1 pageShiv Kumar Batalvi: Punjabi KavitaHarsh Kumar50% (2)

- John Donne As A Religious PoetDocument8 pagesJohn Donne As A Religious Poetabc def100% (3)

- Penny Ur A Course in Language Teaching Practice of TheoryDocument388 pagesPenny Ur A Course in Language Teaching Practice of TheoryThelearningHights100% (15)

- On The Death of Bejamin Franklin AnalysisDocument2 pagesOn The Death of Bejamin Franklin AnalysisAsmaa BaghliNo ratings yet

- John Donne As A Metaphysical PoetDocument17 pagesJohn Donne As A Metaphysical PoetAngielyn Montibon Jesus100% (1)

- The Flea by John DonneDocument2 pagesThe Flea by John Donnesayeraafia001No ratings yet

- Studying Metaphysical Poetry PDFDocument9 pagesStudying Metaphysical Poetry PDFArghya ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- CONCEITDocument5 pagesCONCEITJahangir AlamNo ratings yet

- The Flea - John DonneDocument12 pagesThe Flea - John DonneMazvitaishe MudamburiNo ratings yet

- John Donne - Poetry FoundationDocument19 pagesJohn Donne - Poetry FoundationCarlosNo ratings yet

- World University of Bangladesh: Elizabethan and Seventeenth Century Poetry ENG - 411Document8 pagesWorld University of Bangladesh: Elizabethan and Seventeenth Century Poetry ENG - 411Tashfeen AhmedNo ratings yet

- Literary PiecesDocument20 pagesLiterary PiecesAlyzza DhelNo ratings yet

- The Good MorrowDocument2 pagesThe Good MorrowPrantik RoyNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 John Donne The Good Morrow N The CanonizationDocument12 pagesUnit 4 John Donne The Good Morrow N The CanonizationQuratulain AnnieNo ratings yet

- The Double FlameDocument161 pagesThe Double FlameMilan Markovic MatthisNo ratings yet

- Metaphysical PoetryDocument37 pagesMetaphysical PoetryAmalia Mihaela GrososNo ratings yet

- Lesson Vietnam: LITR 102: ASEAN Literature Miss Krizel Joanne D. FainaDocument21 pagesLesson Vietnam: LITR 102: ASEAN Literature Miss Krizel Joanne D. FainaArneldNiguelAriolaNo ratings yet

- John Donne - Metaphysical PoetryDocument30 pagesJohn Donne - Metaphysical Poetryshambhawisingh8008No ratings yet

- Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry by Mujahid Jalil 03052965256Document4 pagesCharacteristics of Metaphysical Poetry by Mujahid Jalil 03052965256DDC RYKNo ratings yet

- The Principles of English Metaphysical Poetry Through The Eyes of John Donne in The Good-MorrowDocument6 pagesThe Principles of English Metaphysical Poetry Through The Eyes of John Donne in The Good-MorrowKva KhadarNo ratings yet

- Daryna Borovets Group 2.3 Definition of Conceit: Extended MetaphorDocument5 pagesDaryna Borovets Group 2.3 Definition of Conceit: Extended MetaphorDaria BorovetsNo ratings yet

- Prose and Poetry - Definition and SamplesDocument9 pagesProse and Poetry - Definition and Samplesjulie anne mae mendozaNo ratings yet

- Sonnets Latin Epigrams Elegies SermonsDocument5 pagesSonnets Latin Epigrams Elegies SermonsDiana Craciun100% (1)

- The CaninizationDocument22 pagesThe CaninizationIffat JahanNo ratings yet

- To His Coy Mistress by AndrewDocument15 pagesTo His Coy Mistress by Andrew2020311186No ratings yet

- The Good Morrow Analysis PDFDocument3 pagesThe Good Morrow Analysis PDFKatie50% (2)

- HAIKUDocument14 pagesHAIKUNieva Marie EstenzoNo ratings yet

- The Good Morrow NotesDocument7 pagesThe Good Morrow NotesRhea WyntersNo ratings yet

- Prose and PoetryDocument12 pagesProse and PoetryElaine Antonette RositaNo ratings yet

- Batter My HeartDocument5 pagesBatter My HeartAngelie MultaniNo ratings yet

- Annotated Reading List Literature 10Document27 pagesAnnotated Reading List Literature 10ajeccamaeNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 Poetry Booklet 20171Document15 pagesGrade 11 Poetry Booklet 20171RetuNo ratings yet

- To His Coy MistressDocument6 pagesTo His Coy MistressChie Ibay100% (1)

- Metaphysical Poetry On LoveDocument27 pagesMetaphysical Poetry On LovenichodemusNo ratings yet

- Kera Dukes Paper 2Document5 pagesKera Dukes Paper 2api-684490733No ratings yet

- Donne The FleaDocument22 pagesDonne The FleaRabia ImtiazNo ratings yet

- Assignment Canonization As A Metaphysical Poem - CompressDocument9 pagesAssignment Canonization As A Metaphysical Poem - CompressbozNo ratings yet

- Hum 1 MLG #4Document12 pagesHum 1 MLG #4Racquel BanaoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Romantic PoetryDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Romantic Poetrywgaaobsif100% (1)

- Sonnet 6Document4 pagesSonnet 6Brahmankhanda Basapara HIGH SCHOOLNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Metaphysical PoetryDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Metaphysical Poetryafedoeike100% (1)

- Andrew Marvell To His Coy Mistress SQDocument16 pagesAndrew Marvell To His Coy Mistress SQRania Al MasoudiNo ratings yet

- The Good-Morrow: Were We Not Weaned Till Then? To Be Weaned Is To Be Influenced From An Early Age To Be ADocument5 pagesThe Good-Morrow: Were We Not Weaned Till Then? To Be Weaned Is To Be Influenced From An Early Age To Be ATapi Sk100% (1)

- Latin Ame 2Document8 pagesLatin Ame 2Maria Niña BatulanNo ratings yet

- John Donne As A Religious PoetDocument5 pagesJohn Donne As A Religious Poetabc defNo ratings yet

- John DonneDocument5 pagesJohn Donneabc defNo ratings yet

- John DonneDocument5 pagesJohn Donneabc def100% (1)

- Cento Midterm PDFDocument6 pagesCento Midterm PDFapi-311856887No ratings yet

- John DonneDocument4 pagesJohn DonneInes AnnafNo ratings yet

- PoemsDocument30 pagesPoemsAneesh ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Knjiz 2 ParcijalaDocument19 pagesKnjiz 2 ParcijalaEminaNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Metaphysical PoetryDocument8 pagesCharacteristics of Metaphysical PoetrysvettelNo ratings yet

- Metaphysical Poetry: Metaphysical Conceit Is An Elaborate or Unusual Comparison - Especially One UsingDocument8 pagesMetaphysical Poetry: Metaphysical Conceit Is An Elaborate or Unusual Comparison - Especially One UsingP S Prasanth NeyyattinkaraNo ratings yet

- Second Analysis - The Flea and She Walks in BeautyDocument5 pagesSecond Analysis - The Flea and She Walks in BeautyFrankNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of IndifferntDocument3 pagesCritical Analysis of IndifferntYuffi Almi BinuliaNo ratings yet

- Poetry EssayDocument4 pagesPoetry EssayAlex HadfieldNo ratings yet

- THE ALCHEMY OF POETRY: A READER'S GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING POETRYFrom EverandTHE ALCHEMY OF POETRY: A READER'S GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING POETRYNo ratings yet

- 21st-CenturyLit Quarter2 Week4Document6 pages21st-CenturyLit Quarter2 Week4SHAINE UNGABNo ratings yet

- Good Morrow Analysis SparknotesDocument3 pagesGood Morrow Analysis SparknotesMichelleNo ratings yet

- The Wars of 1541-1568 - BasicDocument10 pagesThe Wars of 1541-1568 - BasicÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- The Ethnic and Religious Makeup of Transylvania - Basic-2Document6 pagesThe Ethnic and Religious Makeup of Transylvania - Basic-2Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Old and Middle English Literature-6Document6 pagesOld and Middle English Literature-6Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- 1660-1890 Poetry-2Document8 pages1660-1890 Poetry-2Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Byron - Don Juan-3Document2 pagesByron - Don Juan-3Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Tudor Era PoetryDocument2 pagesTudor Era PoetryÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- The Reign of Charles IDocument19 pagesThe Reign of Charles IÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- History 11 Book p3Document15 pagesHistory 11 Book p3Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Athenian Democracy - Part 2Document14 pagesAthenian Democracy - Part 2Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- History 9 Book - 2022-2Document5 pagesHistory 9 Book - 2022-2Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- The Great Depression PDFDocument19 pagesThe Great Depression PDFÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Strategies in EFL Vocabulary AcquisitionDocument48 pagesThe Importance of Strategies in EFL Vocabulary AcquisitionÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Edgar Allan Poe and The GothicDocument5 pagesEdgar Allan Poe and The GothicÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- STILTSDocument21 pagesSTILTSjemima stonesNo ratings yet

- W1 Intro To LitDocument23 pagesW1 Intro To LitDenverrsNo ratings yet

- Passage Sept-Oct 2017 FINAL 11Document1 pagePassage Sept-Oct 2017 FINAL 11NANTHA KUMARANNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - DaffodilsDocument16 pagesUnit 5 - DaffodilsHaris HafeezNo ratings yet

- Aunt Jennifer's Tigers by Adrienne Rich Analysis PDFDocument3 pagesAunt Jennifer's Tigers by Adrienne Rich Analysis PDFKhalil AbdulhameedNo ratings yet

- Ii M.A. English Men 33 - Contemporary Literary Theory-IDocument16 pagesIi M.A. English Men 33 - Contemporary Literary Theory-IsasoikumarNo ratings yet

- House On Mango Street 3 3 3Document3 pagesHouse On Mango Street 3 3 3DudzNo ratings yet

- Make A Comparative Study On The Idea of Spiritual Movement in Sailing To Byzantium and The Force That Through The Green Fuse Drives The Flower.Document2 pagesMake A Comparative Study On The Idea of Spiritual Movement in Sailing To Byzantium and The Force That Through The Green Fuse Drives The Flower.Arafat ShahriarNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 9 DLL NewDocument37 pagesENGLISH 9 DLL NewLORAINE LACERNA GAMMAD0% (1)

- EvaluationDocument6 pagesEvaluationMasters EDRUNo ratings yet

- 20 Example of Figures of SpeechDocument2 pages20 Example of Figures of SpeechCarmie Lactaotao DasallaNo ratings yet

- Bertolt BrechtDocument14 pagesBertolt BrechtPaa Larbi Aboagye-LarbiNo ratings yet

- Slides Aula 1 Literatura Lingua INGLESADocument7 pagesSlides Aula 1 Literatura Lingua INGLESARonaldo Silva de MouraNo ratings yet

- XDDXDocument19 pagesXDDXMehul AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Jeff PFT 21STDocument8 pagesJeff PFT 21STJeff Buna IIINo ratings yet

- (The Pelican Guide To English Literature, Vol. 6) Boris Ford-The Pelican Guide To English Literature 6 - From Dickens To Hardy-Penguin BooksDocument524 pages(The Pelican Guide To English Literature, Vol. 6) Boris Ford-The Pelican Guide To English Literature 6 - From Dickens To Hardy-Penguin Booksdrsaleem92% (13)

- Modernist Poetry: Reading Material Tulips and ChimneysDocument5 pagesModernist Poetry: Reading Material Tulips and ChimneysalinaNo ratings yet

- 0 KONTRAK KULIAH ProsaDocument3 pages0 KONTRAK KULIAH ProsaBlue SkyNo ratings yet

- New Customer? Start HereDocument3 pagesNew Customer? Start HereGulshan DubeyNo ratings yet

- крDocument5 pagesкрАнастасия СтавроваNo ratings yet

- OthelloDocument107 pagesOthello9D BoomNo ratings yet

- HIndi PoemsDocument24 pagesHIndi PoemsSujit DwiNo ratings yet

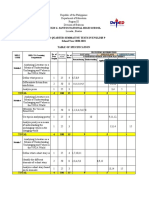

- Tos Quarter 3Document2 pagesTos Quarter 3Belle Herminigildo AngelesNo ratings yet

- CXC Past Paper Type Reading Comprehension QuestionsDocument13 pagesCXC Past Paper Type Reading Comprehension QuestionsKenan Cain60% (5)

- Aoe Readers Writers TextsDocument7 pagesAoe Readers Writers Textsapi-521174998No ratings yet

- Autumn and Today Sample AnswerDocument2 pagesAutumn and Today Sample AnswerPIRIYANo ratings yet

- 1st Quarter Exam - 21st Century LitDocument4 pages1st Quarter Exam - 21st Century LitRosette EvangelistaNo ratings yet

Metaphysical Poets-2

Metaphysical Poets-2

Uploaded by

Ádám LajtaiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Metaphysical Poets-2

Metaphysical Poets-2

Uploaded by

Ádám LajtaiCopyright:

Available Formats

The metaphysical poets

Who were the metaphysical poets? What is metaphysical in this context?

The metaphysical poets were a group of 17th-century English poets who are characterized by their

intellectual, often intellectually challenging poetry that often made use of unusual and extended

metaphors called “conceits”. The term "metaphysical poets" was coined by the poet and critic

Samuel Johnson to describe a loose group of poets whose work was characterized by the use of

elaborate and intricate conceits, and a focus on themes of love, desire, and the relationship between

the soul and the body. Some of the most famous metaphysical poets include John Donne, Andrew

Marvell, George Herbert, and Henry Vaughan.

John Donne (1572-1631)

John Donne was an English poet, preacher, and a major representative of the metaphysical poets of the

period. He is known for his complex and highly intellectual poetry that deals with themes of love,

spirituality, and mortality. Donne's work is notable for its use of paradox, wit, and elaborate conceits.

He is also known for his love poetry, which is often characterized by its sensual and erotic language.

Some of John Donne's most important and well-known poems include:

● "The Flea" (published in the 1630s, probably written in the 1590s)

○ Basic content: This erotic poem uses the conceit of a flea sucking the blood of both the

speaker and his lover as a metaphor for sexual intimacy. The speaker argues that having

(premarital) sex is no different or no more dishonorable than being bitten by the same

flea.

○ Structure and content: The poem is written in three stanzas, with the first stanza

introducing the flea as the central conceit. In the second stanza, the speaker expands

upon the metaphor, arguing that the flea has "brought together" the two lovers by

sucking their blood and that they are therefore "linked by nature." The final stanza

presents a counterargument to the speaker's lover, who is trying to resist his advances.

The speaker says that the fact that they have already been "linked" by the flea means

that there is no harm in giving in to their desires and consummating their relationship.

○ Other ideas:

■ Despite the obvious erotic nature of the poem, Donne succeeds in covering his

true intentions with the conceit.

■ The poem can also be seen as a carpe diem poem in which the speaker urges the

lady to “seize the moment” and become intimate with him.

“The Flea”

But this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou deniest me is;

It sucked me first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea our two bloods mingled be;

Thou know’st that this cannot be said

A sin, nor shame, nor loss of maidenhead,

Yet this enjoys before it woo,

And pampered swells with one blood made of two,

And this, alas, is more than we would do.

Oh stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where we almost, nay more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is;

Though parents grudge, and you, w'are met,

And cloistered in these living walls of jet.

Though use make you apt to kill me,

Let not to that, self-murder added be,

And sacrilege, three sins in killing three.

Cruel and sudden, hast thou since

Purpled thy nail, in blood of innocence?

Wherein could this flea guilty be,

Except in that drop which it sucked from thee?

Yet thou triumph’st, and say'st that thou

Find’st not thy self, nor me the weaker now;

’Tis true; then learn how false, fears be:

Just so much honor, when thou yield’st to me,

Will waste, as this flea’s death took life from thee.

● "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning" - This poem is a farewell to a loved one and employs the

conceit of a compass to describe the separation of two lovers.

● "Death, Be Not Proud" - This poem is a meditation on the nature of death and uses the conceit

of death as a person to argue that it is not something to be feared.

● "The Good-Morrow" - This poem celebrates the start of a new day and the beginning of a new

love, using the conceit of two lovers as newly discovered worlds.

● “The Ecstasy” - A longer and more complex seduction poem that explores the theme of

spiritual and physical union through the conceit (metaphor) of two souls becoming one.

○ Basic content: The title “Ecstasy” comes from the Greek, ekstasis, meaning literally

‘outside standing’: in the poem, the souls of the man and the woman leave their body to

unite during physical intimacy, but at the end of the poem, the souls return to their

respective bodies. The poem is probably the best representation of Donne’s conception

of love.

○ Structure: The poem comprises 19 four-lined stanzas (or quatrains). Through the poem,

there’s a gradual change from a peaceful, pure and pastoral understanding of love

towards clear seduction.

○ Other ideas: The poem is the first in John Donne’s poetry to clearly include the word

“sex”.

This ecstasy doth unperplex,

We said, and tell us what we love;

We see by this it was not sex,

We see we saw not what did move;

● “To His Mistress Going to Bed” - Another erotic poem by John Donne that celebrates the act

of physical intimacy between the speaker and his mistress.

○ Basic content: The poem is written as a seduction, with the speaker attempting to

persuade his mistress to give in to his advances and go to bed with him. In the poem, the

speaker uses a series of elaborate conceits to describe the various stages of sexual

intimacy.

■ The conceit of the map and travelling: he compares his mistress's body to a map

of a new land that he will explore and the journey as the intercourse with the

woman

● O my America! my new-found-land,

My kingdom, safeliest when with one man mann’d,

My Mine of precious stones, My Empirie,

How blest am I in this discovering thee!

To enter in these bonds, is to be free;

Then where my hand is set, my seal shall be.

● This conceit can be understood as an allusion to the discovery of

America during the late Elizabethan/early Jacobite era

■ The poem ends with a famous double entendre (a phrase with two

interpretations, one is often sexual) where he says that now that he is naked, the

woman does not need to be “covered” by anything else than a man.

● “To teach thee, I am naked first; why then,

What needst thou have more covering than a man?”

○ Structure: The poem comprises one long stanza, in rhyming couplets. The metrical

rhythm is iambic pentameter.

○ Other ideas:

■ Originally, it was titled Elegy XIX.

■ The poem was rejected for publishing in the 1630s, and was only printed in an

anthology in the 1650s.

Andrew Marvell (1621-1678) and “To His Coy Mistress”

Andrew Marvell was an English poet, satirist, and politician who was a major figure in the metaphysical

poetry movement of the seventeenth century. He is known for his complex and intellectually challenging

poetry, which often deals with themes of love, politics, and the natural world. Marvell's poetry is

notable for its use of wit, irony, and paradox to explore complex ideas and themes. Marvell is perhaps

best known for his metaphysical poem "To His Coy Mistress”.

● The meaning of the word “coy”: pretending to be shy and modest as a way of being alluring or

seductive

● Basic ideas: "To His Coy Mistress” is a seduction poem that uses the conceit of the passage of

time to argue for the urgency of physical intimacy. The poem is one of the most famous carpe

diem poems in English literature as the speaker urges his mistress to seize the moment and

give in to their desires.

● Structure and content: The poem is written in three stanzas, with each stanza representing a

different stage in the passage of time. The poem is made up of 23 rhyming couplets: the first

stanza is made up of 10, the second of 7, and the third of 6.

○ In the first stanza (“Had we but …”), the speaker imagines a scenario in which they have

an eternity to be together, and he would take the time to praise and adore every part of

her body.

Had we but World enough, and Time,

This coyness, Lady, were no crime. [...]

And you should if you please refuse

Till the Conversion of the Jews.

My vegetable Love should grow

Vaster than Empires, and more slow.

○ In the second stanza (“But …”), the speaker acknowledges that this scenario is not

possible and that they must deal with the reality of their limited time together. The

speaker argues that when they are dead, they do not have the opportunity to enjoy each

other (“The Grave's a fine and private place, but none I think do there embrace.”)

My ecchoing Song: then Worms shall try

That long preserv'd Virginity:

And your quaint Honour turn to dust;

And into ashes all my Lust.

○ In the final stanza (“Now therefore …”), the speaker urges his mistress to "make use" of

their remaining time and give in to their desires, arguing that the only way to truly

possess and enjoy each other's bodies is through physical intimacy.

Rather at once our Time devour,

Than languish in his slow-chapt pow'r.

Let us roll all our Strength, and all

Our sweetness, up into one Ball:

You might also like

- Paz, Octavio - The Double Flame (Harcourt, 1995)Document288 pagesPaz, Octavio - The Double Flame (Harcourt, 1995)Andres100% (7)

- Igitabo Cy'imishingaDocument191 pagesIgitabo Cy'imishingaDr. Sixbert SANGWA100% (1)

- Shiv Kumar Batalvi: Punjabi KavitaDocument1 pageShiv Kumar Batalvi: Punjabi KavitaHarsh Kumar50% (2)

- John Donne As A Religious PoetDocument8 pagesJohn Donne As A Religious Poetabc def100% (3)

- Penny Ur A Course in Language Teaching Practice of TheoryDocument388 pagesPenny Ur A Course in Language Teaching Practice of TheoryThelearningHights100% (15)

- On The Death of Bejamin Franklin AnalysisDocument2 pagesOn The Death of Bejamin Franklin AnalysisAsmaa BaghliNo ratings yet

- John Donne As A Metaphysical PoetDocument17 pagesJohn Donne As A Metaphysical PoetAngielyn Montibon Jesus100% (1)

- The Flea by John DonneDocument2 pagesThe Flea by John Donnesayeraafia001No ratings yet

- Studying Metaphysical Poetry PDFDocument9 pagesStudying Metaphysical Poetry PDFArghya ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- CONCEITDocument5 pagesCONCEITJahangir AlamNo ratings yet

- The Flea - John DonneDocument12 pagesThe Flea - John DonneMazvitaishe MudamburiNo ratings yet

- John Donne - Poetry FoundationDocument19 pagesJohn Donne - Poetry FoundationCarlosNo ratings yet

- World University of Bangladesh: Elizabethan and Seventeenth Century Poetry ENG - 411Document8 pagesWorld University of Bangladesh: Elizabethan and Seventeenth Century Poetry ENG - 411Tashfeen AhmedNo ratings yet

- Literary PiecesDocument20 pagesLiterary PiecesAlyzza DhelNo ratings yet

- The Good MorrowDocument2 pagesThe Good MorrowPrantik RoyNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 John Donne The Good Morrow N The CanonizationDocument12 pagesUnit 4 John Donne The Good Morrow N The CanonizationQuratulain AnnieNo ratings yet

- The Double FlameDocument161 pagesThe Double FlameMilan Markovic MatthisNo ratings yet

- Metaphysical PoetryDocument37 pagesMetaphysical PoetryAmalia Mihaela GrososNo ratings yet

- Lesson Vietnam: LITR 102: ASEAN Literature Miss Krizel Joanne D. FainaDocument21 pagesLesson Vietnam: LITR 102: ASEAN Literature Miss Krizel Joanne D. FainaArneldNiguelAriolaNo ratings yet

- John Donne - Metaphysical PoetryDocument30 pagesJohn Donne - Metaphysical Poetryshambhawisingh8008No ratings yet

- Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry by Mujahid Jalil 03052965256Document4 pagesCharacteristics of Metaphysical Poetry by Mujahid Jalil 03052965256DDC RYKNo ratings yet

- The Principles of English Metaphysical Poetry Through The Eyes of John Donne in The Good-MorrowDocument6 pagesThe Principles of English Metaphysical Poetry Through The Eyes of John Donne in The Good-MorrowKva KhadarNo ratings yet

- Daryna Borovets Group 2.3 Definition of Conceit: Extended MetaphorDocument5 pagesDaryna Borovets Group 2.3 Definition of Conceit: Extended MetaphorDaria BorovetsNo ratings yet

- Prose and Poetry - Definition and SamplesDocument9 pagesProse and Poetry - Definition and Samplesjulie anne mae mendozaNo ratings yet

- Sonnets Latin Epigrams Elegies SermonsDocument5 pagesSonnets Latin Epigrams Elegies SermonsDiana Craciun100% (1)

- The CaninizationDocument22 pagesThe CaninizationIffat JahanNo ratings yet

- To His Coy Mistress by AndrewDocument15 pagesTo His Coy Mistress by Andrew2020311186No ratings yet

- The Good Morrow Analysis PDFDocument3 pagesThe Good Morrow Analysis PDFKatie50% (2)

- HAIKUDocument14 pagesHAIKUNieva Marie EstenzoNo ratings yet

- The Good Morrow NotesDocument7 pagesThe Good Morrow NotesRhea WyntersNo ratings yet

- Prose and PoetryDocument12 pagesProse and PoetryElaine Antonette RositaNo ratings yet

- Batter My HeartDocument5 pagesBatter My HeartAngelie MultaniNo ratings yet

- Annotated Reading List Literature 10Document27 pagesAnnotated Reading List Literature 10ajeccamaeNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 Poetry Booklet 20171Document15 pagesGrade 11 Poetry Booklet 20171RetuNo ratings yet

- To His Coy MistressDocument6 pagesTo His Coy MistressChie Ibay100% (1)

- Metaphysical Poetry On LoveDocument27 pagesMetaphysical Poetry On LovenichodemusNo ratings yet

- Kera Dukes Paper 2Document5 pagesKera Dukes Paper 2api-684490733No ratings yet

- Donne The FleaDocument22 pagesDonne The FleaRabia ImtiazNo ratings yet

- Assignment Canonization As A Metaphysical Poem - CompressDocument9 pagesAssignment Canonization As A Metaphysical Poem - CompressbozNo ratings yet

- Hum 1 MLG #4Document12 pagesHum 1 MLG #4Racquel BanaoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Romantic PoetryDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Romantic Poetrywgaaobsif100% (1)

- Sonnet 6Document4 pagesSonnet 6Brahmankhanda Basapara HIGH SCHOOLNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Metaphysical PoetryDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Metaphysical Poetryafedoeike100% (1)

- Andrew Marvell To His Coy Mistress SQDocument16 pagesAndrew Marvell To His Coy Mistress SQRania Al MasoudiNo ratings yet

- The Good-Morrow: Were We Not Weaned Till Then? To Be Weaned Is To Be Influenced From An Early Age To Be ADocument5 pagesThe Good-Morrow: Were We Not Weaned Till Then? To Be Weaned Is To Be Influenced From An Early Age To Be ATapi Sk100% (1)

- Latin Ame 2Document8 pagesLatin Ame 2Maria Niña BatulanNo ratings yet

- John Donne As A Religious PoetDocument5 pagesJohn Donne As A Religious Poetabc defNo ratings yet

- John DonneDocument5 pagesJohn Donneabc defNo ratings yet

- John DonneDocument5 pagesJohn Donneabc def100% (1)

- Cento Midterm PDFDocument6 pagesCento Midterm PDFapi-311856887No ratings yet

- John DonneDocument4 pagesJohn DonneInes AnnafNo ratings yet

- PoemsDocument30 pagesPoemsAneesh ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Knjiz 2 ParcijalaDocument19 pagesKnjiz 2 ParcijalaEminaNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Metaphysical PoetryDocument8 pagesCharacteristics of Metaphysical PoetrysvettelNo ratings yet

- Metaphysical Poetry: Metaphysical Conceit Is An Elaborate or Unusual Comparison - Especially One UsingDocument8 pagesMetaphysical Poetry: Metaphysical Conceit Is An Elaborate or Unusual Comparison - Especially One UsingP S Prasanth NeyyattinkaraNo ratings yet

- Second Analysis - The Flea and She Walks in BeautyDocument5 pagesSecond Analysis - The Flea and She Walks in BeautyFrankNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of IndifferntDocument3 pagesCritical Analysis of IndifferntYuffi Almi BinuliaNo ratings yet

- Poetry EssayDocument4 pagesPoetry EssayAlex HadfieldNo ratings yet

- THE ALCHEMY OF POETRY: A READER'S GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING POETRYFrom EverandTHE ALCHEMY OF POETRY: A READER'S GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING POETRYNo ratings yet

- 21st-CenturyLit Quarter2 Week4Document6 pages21st-CenturyLit Quarter2 Week4SHAINE UNGABNo ratings yet

- Good Morrow Analysis SparknotesDocument3 pagesGood Morrow Analysis SparknotesMichelleNo ratings yet

- The Wars of 1541-1568 - BasicDocument10 pagesThe Wars of 1541-1568 - BasicÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- The Ethnic and Religious Makeup of Transylvania - Basic-2Document6 pagesThe Ethnic and Religious Makeup of Transylvania - Basic-2Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Old and Middle English Literature-6Document6 pagesOld and Middle English Literature-6Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- 1660-1890 Poetry-2Document8 pages1660-1890 Poetry-2Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Byron - Don Juan-3Document2 pagesByron - Don Juan-3Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Tudor Era PoetryDocument2 pagesTudor Era PoetryÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- The Reign of Charles IDocument19 pagesThe Reign of Charles IÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- History 11 Book p3Document15 pagesHistory 11 Book p3Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Athenian Democracy - Part 2Document14 pagesAthenian Democracy - Part 2Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- History 9 Book - 2022-2Document5 pagesHistory 9 Book - 2022-2Ádám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- The Great Depression PDFDocument19 pagesThe Great Depression PDFÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Strategies in EFL Vocabulary AcquisitionDocument48 pagesThe Importance of Strategies in EFL Vocabulary AcquisitionÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- Edgar Allan Poe and The GothicDocument5 pagesEdgar Allan Poe and The GothicÁdám LajtaiNo ratings yet

- STILTSDocument21 pagesSTILTSjemima stonesNo ratings yet

- W1 Intro To LitDocument23 pagesW1 Intro To LitDenverrsNo ratings yet

- Passage Sept-Oct 2017 FINAL 11Document1 pagePassage Sept-Oct 2017 FINAL 11NANTHA KUMARANNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - DaffodilsDocument16 pagesUnit 5 - DaffodilsHaris HafeezNo ratings yet

- Aunt Jennifer's Tigers by Adrienne Rich Analysis PDFDocument3 pagesAunt Jennifer's Tigers by Adrienne Rich Analysis PDFKhalil AbdulhameedNo ratings yet

- Ii M.A. English Men 33 - Contemporary Literary Theory-IDocument16 pagesIi M.A. English Men 33 - Contemporary Literary Theory-IsasoikumarNo ratings yet

- House On Mango Street 3 3 3Document3 pagesHouse On Mango Street 3 3 3DudzNo ratings yet

- Make A Comparative Study On The Idea of Spiritual Movement in Sailing To Byzantium and The Force That Through The Green Fuse Drives The Flower.Document2 pagesMake A Comparative Study On The Idea of Spiritual Movement in Sailing To Byzantium and The Force That Through The Green Fuse Drives The Flower.Arafat ShahriarNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 9 DLL NewDocument37 pagesENGLISH 9 DLL NewLORAINE LACERNA GAMMAD0% (1)

- EvaluationDocument6 pagesEvaluationMasters EDRUNo ratings yet

- 20 Example of Figures of SpeechDocument2 pages20 Example of Figures of SpeechCarmie Lactaotao DasallaNo ratings yet

- Bertolt BrechtDocument14 pagesBertolt BrechtPaa Larbi Aboagye-LarbiNo ratings yet

- Slides Aula 1 Literatura Lingua INGLESADocument7 pagesSlides Aula 1 Literatura Lingua INGLESARonaldo Silva de MouraNo ratings yet

- XDDXDocument19 pagesXDDXMehul AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Jeff PFT 21STDocument8 pagesJeff PFT 21STJeff Buna IIINo ratings yet

- (The Pelican Guide To English Literature, Vol. 6) Boris Ford-The Pelican Guide To English Literature 6 - From Dickens To Hardy-Penguin BooksDocument524 pages(The Pelican Guide To English Literature, Vol. 6) Boris Ford-The Pelican Guide To English Literature 6 - From Dickens To Hardy-Penguin Booksdrsaleem92% (13)

- Modernist Poetry: Reading Material Tulips and ChimneysDocument5 pagesModernist Poetry: Reading Material Tulips and ChimneysalinaNo ratings yet

- 0 KONTRAK KULIAH ProsaDocument3 pages0 KONTRAK KULIAH ProsaBlue SkyNo ratings yet

- New Customer? Start HereDocument3 pagesNew Customer? Start HereGulshan DubeyNo ratings yet

- крDocument5 pagesкрАнастасия СтавроваNo ratings yet

- OthelloDocument107 pagesOthello9D BoomNo ratings yet

- HIndi PoemsDocument24 pagesHIndi PoemsSujit DwiNo ratings yet

- Tos Quarter 3Document2 pagesTos Quarter 3Belle Herminigildo AngelesNo ratings yet

- CXC Past Paper Type Reading Comprehension QuestionsDocument13 pagesCXC Past Paper Type Reading Comprehension QuestionsKenan Cain60% (5)

- Aoe Readers Writers TextsDocument7 pagesAoe Readers Writers Textsapi-521174998No ratings yet

- Autumn and Today Sample AnswerDocument2 pagesAutumn and Today Sample AnswerPIRIYANo ratings yet

- 1st Quarter Exam - 21st Century LitDocument4 pages1st Quarter Exam - 21st Century LitRosette EvangelistaNo ratings yet