Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Harter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Co

Harter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Co

Uploaded by

Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Asce 32-01Document32 pagesAsce 32-01Slobodan Djurdjevic100% (4)

- Labour Rate RecommendedDocument102 pagesLabour Rate RecommendedSarinNo ratings yet

- Wellman and Liu (2004)Document20 pagesWellman and Liu (2004)Gülhan SaraçaydınNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Piaget's Cognitive DevelopmentDocument11 pagesCase Study On Piaget's Cognitive DevelopmentJuvié BanaganNo ratings yet

- Slaughter Dennis Pritchard - 2002 - Theory of Mind and Peer Acceptance in Preschool ChildrenDocument20 pagesSlaughter Dennis Pritchard - 2002 - Theory of Mind and Peer Acceptance in Preschool ChildrenMilicaNo ratings yet

- Damon & HartDocument25 pagesDamon & Harttrain_xii15No ratings yet

- The Development of Self Concept PDFDocument9 pagesThe Development of Self Concept PDFLone SurvivorNo ratings yet

- Belsky - Steinberg - Draper - An Evolutionary Theory of SocializationDocument25 pagesBelsky - Steinberg - Draper - An Evolutionary Theory of SocializationPablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Harter 1981 SElf Report Scale of IntrinsicDocument13 pagesHarter 1981 SElf Report Scale of IntrinsicChristiane ArrivillagaNo ratings yet

- SITXFSA001 - Student AssessmentDocument31 pagesSITXFSA001 - Student AssessmentNiroj Adhikari100% (3)

- Wiley Society For Research in Child DevelopmentDocument15 pagesWiley Society For Research in Child DevelopmentCatarina RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Persepsi 22Document12 pagesPersepsi 22rizka fadhilllahNo ratings yet

- 2002 Cognitive DevDocument28 pages2002 Cognitive DevUshaNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Social and Emotional DevelopmentDocument7 pagesEarly Childhood Social and Emotional DevelopmentKANIA KUSUMA WARDANINo ratings yet

- Damon - Infancy To AdelocanceDocument25 pagesDamon - Infancy To AdelocanceRamani ChandranNo ratings yet

- Psych 2018070615171199Document25 pagesPsych 2018070615171199Francisca PuriceNo ratings yet

- William N. Bender and Maureen E. Wall: TraditionallyDocument8 pagesWilliam N. Bender and Maureen E. Wall: TraditionallyFajar HandokoNo ratings yet

- Cáceres Et Al. 2021 Longitudinal Social Competence ECRQDocument11 pagesCáceres Et Al. 2021 Longitudinal Social Competence ECRQAndré Pepe RobaloNo ratings yet

- Development Cocept of WarDocument18 pagesDevelopment Cocept of WarMario CordobaNo ratings yet

- Attention Structure, Sociometric Status, and Dominance: Interrelations, Behavioral Correlates, and Relationships To Social CompetenceDocument14 pagesAttention Structure, Sociometric Status, and Dominance: Interrelations, Behavioral Correlates, and Relationships To Social CompetencecmcfNo ratings yet

- Article - Child Development Theories and Teaching English For Young Learners in IndonesiaDocument6 pagesArticle - Child Development Theories and Teaching English For Young Learners in IndonesiaBagus Putra AsnadaNo ratings yet

- Konsep Diri 2Document14 pagesKonsep Diri 2fransisca dariniNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of Measures of Self-Esteem For Young ChildrenDocument20 pagesA Meta-Analysis of Measures of Self-Esteem For Young ChildrenkarinadapariaNo ratings yet

- Woo AnnualReview 220630Document45 pagesWoo AnnualReview 220630Karlo VizecNo ratings yet

- Concept Development in Preschool ChildrenDocument20 pagesConcept Development in Preschool ChildrenSERGIO ANDRES GONZALEZ LOZANONo ratings yet

- Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology: Tamara G. Halle, Kristen E. Darling-ChurchillDocument11 pagesJournal of Applied Developmental Psychology: Tamara G. Halle, Kristen E. Darling-ChurchillFiorela Arana BaldeónNo ratings yet

- Example of Research Paper On Human DevelopmentDocument8 pagesExample of Research Paper On Human DevelopmentwgaaobsifNo ratings yet

- Concept of WarDocument16 pagesConcept of WarRafael SOaresNo ratings yet

- Wertsch Adult Child Dyad ProblemSolving 1980Document8 pagesWertsch Adult Child Dyad ProblemSolving 1980Danny CrisNo ratings yet

- 1980 Development of Altruistic Behavior Dev Psych - PDF: Related PapersDocument10 pages1980 Development of Altruistic Behavior Dev Psych - PDF: Related PapersNur AeniNo ratings yet

- The Cognitive Structure of Parenthood Designing ADocument25 pagesThe Cognitive Structure of Parenthood Designing AClaudina PachecoNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Overview of Physical, Cognitive, and Moral Development in PsychologyFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Overview of Physical, Cognitive, and Moral Development in PsychologyNo ratings yet

- Social Status, School Performance and Behavioral Nature of Children in The Foster Home: Basis For Developing Intervention ActivitiesDocument8 pagesSocial Status, School Performance and Behavioral Nature of Children in The Foster Home: Basis For Developing Intervention Activitiesjautor59754No ratings yet

- The Development of Self-Conceptions From Childhood To AdolescenceDocument7 pagesThe Development of Self-Conceptions From Childhood To AdolescenceTina DevianaNo ratings yet

- Dev Dev0000548Document12 pagesDev Dev0000548Hoàng Nguyễn Ngọc GiangNo ratings yet

- Social Relationships and Social Skills: A Conceptual and Empirical AnalysisDocument49 pagesSocial Relationships and Social Skills: A Conceptual and Empirical AnalysisjmosyNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Approaches To Educational Research Assumptions, Scope and LimitationsDocument13 pagesUnit 4 Approaches To Educational Research Assumptions, Scope and Limitationsromesh10008No ratings yet

- Development and Content Validity of The Readiness For Filial Responsibility ScaleDocument16 pagesDevelopment and Content Validity of The Readiness For Filial Responsibility ScaleHuemer UyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Child Development TheoriesDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Child Development Theoriesmwjhkmrif100% (1)

- Wiley Society For Research in Child DevelopmentDocument14 pagesWiley Society For Research in Child DevelopmentMaría Inés AramburoNo ratings yet

- 9.2 Development TheoriesDocument6 pages9.2 Development TheoriesmaisytianyiNo ratings yet

- 626f PDFDocument20 pages626f PDFsacli.valentin mjNo ratings yet

- SIR2014Document17 pagesSIR2014Albina ScutaruNo ratings yet

- Do Attitudes Toward Societal Structure Predict Beliefs About Free Will and AchievementDocument70 pagesDo Attitudes Toward Societal Structure Predict Beliefs About Free Will and AchievementJohn BullNo ratings yet

- Applying Emotional Intelligence Exploring The PromDocument22 pagesApplying Emotional Intelligence Exploring The PromAndreea CristinaNo ratings yet

- Giftedness RethinkingDocument52 pagesGiftedness RethinkingManolis DafermosNo ratings yet

- U5 Wa Educ 5410-1Document7 pagesU5 Wa Educ 5410-1TomNo ratings yet

- Dion PhysicalAttractivenessPeer 1974Document13 pagesDion PhysicalAttractivenessPeer 1974gia-thanhphamNo ratings yet

- Age Related Changes in The Individual - Childhood and AdolescenceDocument9 pagesAge Related Changes in The Individual - Childhood and AdolescenceAira Mae MambagNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Transition From Early Childhood Education To SchoolDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Transition From Early Childhood Education To SchoolafdtyaxfvNo ratings yet

- The Development of SelfDocument9 pagesThe Development of SelfAkifa syahrirNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0010027720302602 MainDocument15 pages1 s2.0 S0010027720302602 MainAzmil XinanNo ratings yet

- Development of Self ConceptDocument11 pagesDevelopment of Self ConceptDivya pathakNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 158.195.4.7 On Fri, 02 Dec 2022 10:35:40 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 158.195.4.7 On Fri, 02 Dec 2022 10:35:40 UTCZuzana KriváNo ratings yet

- U7 Wa 5410Document5 pagesU7 Wa 5410TomNo ratings yet

- Profiles of The Gifted and TalentedDocument7 pagesProfiles of The Gifted and TalentedjvasquezcNo ratings yet

- 2016 Siegler ContinuityDocument6 pages2016 Siegler ContinuityFrancis Thomas Pantaleta LimNo ratings yet

- Dahl Killen (2018)Document6 pagesDahl Killen (2018)Andrea BalboaNo ratings yet

- Patterns of Interaction - Grotevant & Cooper (1985)Document15 pagesPatterns of Interaction - Grotevant & Cooper (1985)Will ByersNo ratings yet

- Placing Emotional Self-Regulation in Sociocultural and Socioeconomic ContextsDocument9 pagesPlacing Emotional Self-Regulation in Sociocultural and Socioeconomic ContextsMaria Paula RojasNo ratings yet

- Darling Hammond2019 PDFDocument45 pagesDarling Hammond2019 PDFsantimosNo ratings yet

- Evidence Base For The DIR2-2011D CullinaneDocument11 pagesEvidence Base For The DIR2-2011D CullinanecirclestretchNo ratings yet

- Hudziak 2004Document9 pagesHudziak 2004Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Siu 2008Document12 pagesSiu 2008Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- American Educational Research Association Review of Educational ResearchDocument36 pagesAmerican Educational Research Association Review of Educational ResearchAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Kendall 2000Document13 pagesKendall 2000Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Holt 2013Document9 pagesHolt 2013Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Arslan 2021Document18 pagesArslan 2021Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Impact of Socio-Cultural Factors On Senior Secondary School Students" Academic Achievement in PhysicsDocument7 pagesImpact of Socio-Cultural Factors On Senior Secondary School Students" Academic Achievement in PhysicsAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Karani 2022 The Influence of Screen Time On ChiDocument7 pagesKarani 2022 The Influence of Screen Time On ChiAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Block-Oriented Programming With Tangibles: An Engaging Way To Learn Computational Thinking SkillsDocument4 pagesBlock-Oriented Programming With Tangibles: An Engaging Way To Learn Computational Thinking SkillsAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Retention: Academic and Behavioral Outcomes Through The End of Second GradeDocument17 pagesKindergarten Retention: Academic and Behavioral Outcomes Through The End of Second GradeAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Birthdates of Medical School ApplicantsDocument6 pagesBirthdates of Medical School ApplicantsAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Educational Research: To Cite This Article: Angus H. Thompson, Roger H. Barnsley & James Battle (2004) The RelativeDocument9 pagesEducational Research: To Cite This Article: Angus H. Thompson, Roger H. Barnsley & James Battle (2004) The RelativeAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- TheEffectOfAgeAtSchoolEntryOn PreviewDocument44 pagesTheEffectOfAgeAtSchoolEntryOn PreviewAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Alpha-Synuclein Locus Triplication Causes Parkinson's DiseaseSingleton 2003Document1 pageAlpha-Synuclein Locus Triplication Causes Parkinson's DiseaseSingleton 2003Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0190740916304467 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0190740916304467 Main PDFAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- A Crossover Randomised and Controlled Trial of TheDocument15 pagesA Crossover Randomised and Controlled Trial of TheAlar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- BBG ShortcutsDocument2 pagesBBG ShortcutsnikhilagaNo ratings yet

- French Ab Initio Writing Format Booklet: June 2018Document41 pagesFrench Ab Initio Writing Format Booklet: June 2018Marian Molina RuanoNo ratings yet

- C3g - 2 People v. NardoDocument2 pagesC3g - 2 People v. NardoAaron AristonNo ratings yet

- Lmz12008 8-A Simple Switcher Power Module With 20-V Maximum Input VoltageDocument34 pagesLmz12008 8-A Simple Switcher Power Module With 20-V Maximum Input VoltagediegooliveiraEENo ratings yet

- Aflac Claim FormDocument7 pagesAflac Claim FormThomas Barrett100% (2)

- Theory of Elasticity and Plasticity Model QuestionsDocument2 pagesTheory of Elasticity and Plasticity Model Questionsrameshbabu_1979No ratings yet

- AWNMag5 07Document68 pagesAWNMag5 07Michał MrózNo ratings yet

- Hasil Stok Opname Untuk Bap (Fix)Document35 pagesHasil Stok Opname Untuk Bap (Fix)WARDA NABIELANo ratings yet

- Parametric Study On Behaviour of Box Girder Bridges With Different Shape Based On TorsionDocument5 pagesParametric Study On Behaviour of Box Girder Bridges With Different Shape Based On TorsionOanh PhanNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Stuttering Foundations and Clinical Applications 0131573101Document24 pagesTest Bank For Stuttering Foundations and Clinical Applications 0131573101JimmyHaynessfmg100% (46)

- ICC ESR 4266 KB TZ2 Expansion Anchor Concrete ApprovalDocument16 pagesICC ESR 4266 KB TZ2 Expansion Anchor Concrete Approvalעמי עמרניNo ratings yet

- Grammaire - L1 G1+3+4+7 - M. Benkider - Corrigé Et CommentairesDocument3 pagesGrammaire - L1 G1+3+4+7 - M. Benkider - Corrigé Et CommentairesYssoufFahSNo ratings yet

- 3rd Quarterly ExamDocument8 pages3rd Quarterly ExamLeanmarx TejanoNo ratings yet

- Md. Rubel IslamDocument2 pagesMd. Rubel IslamJoss RonyNo ratings yet

- 31Document5 pages31iskricaman7No ratings yet

- Management Theories and Case StudyDocument5 pagesManagement Theories and Case StudyStephanie KrystelNo ratings yet

- Infinity Users GuideDocument172 pagesInfinity Users GuideSridhar DasariNo ratings yet

- Sumg100 GasDocument32 pagesSumg100 Gascomunicacion socialNo ratings yet

- Fly Ash Bricks PDFDocument46 pagesFly Ash Bricks PDFzilangamba_s4535100% (1)

- K DLP Week 22 Day 3 CarinaDocument6 pagesK DLP Week 22 Day 3 Carinacarina pelaezNo ratings yet

- Hydro OneDocument28 pagesHydro Onefruitnuts67% (3)

- NPCIL Electronics PaperDocument9 pagesNPCIL Electronics Papernetcity143No ratings yet

- Syllabus in Pec 106Document6 pagesSyllabus in Pec 106Clarisse MacalintalNo ratings yet

- SP7000M00W15 000 ADocument10 pagesSP7000M00W15 000 APedro Casimiro GámizNo ratings yet

- Answer:: Multiple ChoiceDocument17 pagesAnswer:: Multiple ChoiceQuenie Jeanne De BaereNo ratings yet

- 13 - Electronics and Sensor Design of AnDocument204 pages13 - Electronics and Sensor Design of AnRox DamianNo ratings yet

- Galanz Case AnalysisDocument10 pagesGalanz Case AnalysisAkshat DasNo ratings yet

Harter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Co

Harter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Co

Uploaded by

Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Harter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Co

Harter 1984 The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Co

Uploaded by

Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteCopyright:

Available Formats

The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance for Young Children

Author(s): Susan Harter and Robin Pike

Source: Child Development , Dec., 1984, Vol. 55, No. 6 (Dec., 1984), pp. 1969-1982

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the Society for Research in Child Development

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1129772

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Society for Research in Child Development and Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to Child Development

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence

and Social Acceptance for Young Children

Susan Harter and Robin Pike

University of Denver

HARTER, SUSAN, and PIKE, ROBIN. The Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and So

tance for Young Children. CHILD DEVELOPMENT, 1984, 55, 1969-1982. A new pictorial

ceived competence and social acceptance for young children, a downward extension

ceived Competence Scale for Children, is described. There-are 2 versions of this instru

preschoolers and kindergartners and a second for first and second graders, each ta

mains: cognitive competence, physical competence, peer acceptance, and maternal

Factor analyses reveal a 2-factor solution. The first factor, general competence, is def

cognitive and physical competence subscales. The second factor, social acceptance, co

peer and maternal acceptance subscales. The psychometric properties were found to be

Weak correlations between children's and teachers' judgments are discussed in terms o

child's tendency to confuse the wish to be competent or accepted with reality. It is urg

instrument not be viewed as a general self-concept scale but be treated as a measure of

constructs, perceived competence and social acceptance.

Introduction perceptions across these domains. This ap-

proach is based on the assumption that chil-

Constructs such as self-concept and self-

dren do not view themselves as equally ade-

esteem have had a long history within the

quate in all domains; rather, we have assumed

field of psychology, although in recent years

that they are capable of making meaningful

there has been a revival of interest in topics

distinctions between different domains.

involving the self and self-description (see

Harter, 1983; Harter, in press). Despite thisSupport for this assumption has been ob-

tained

interest, relatively little attention has been de- in measurement efforts with children

voted to the sensitive measurement of such and adolescents between the ages of 8 and 18.

In the construction of the Self-Perception

constructs, particularly in the young child (see

also Wylie, 1979). The present article de- Profile for Children (Harter, Note 1), we dem-

scribes the construction of a new scale de- onstrated that children differentiate the fol-

signed to assess perceived competence and

lowing five domains as revealed through

factor-analytic procedures: scholastic com-

social acceptance in young children, ages 4-7.

petence, athletic competence, ,'eer accep-

Our conceptual approach to the assess-

tance, physical appearance, and conduct or

ment of self-judgments has been domain-

behavior. In addition to judgments in these

specific, unlike the frameworks adopted by

specific domains, children aged 8 and older

other test constructors (e.g., Coopersmith,

can also make reliable judgments about their

1967; Piers & Harris, 1969), who have sought

general worth as a person. Thus, the current

to assess self-concept or self-esteem primar-

structure of the Self-Perception Profile for

ily through the calculation of a single score,

older children contains five separate domain-

summing items across diverse domains. In

specific subscales as well as a sixth subscale

contrast, we have sought to assess children's

tapping self-worth.

self-judgments separately within specific

domains in order to provide a profile of self- In more recent efforts to devise a self-

The research necessary for the development of this scale was supported by grant HD-09613

from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare. The authors would like to acknowledge the extensive cooperation of both

the school personnel and pupils from the following school systems, without whose assistance this

scale could not have been constructed: the Cherry Creek, Denver, and Jefferson County public

school systems, the Jewish Community Center of Denver, the Evergreen Children's Center, St.

Timothy's Preschool, Wellshire Preschool, and Parker Preschool. The authors also thank the research

personnel in our group, who worked extensively on the development of the scale, including Carole

Efron, Christine Chao, and Beth Ann Bierer. Reprints and information on obtaining materials can be

obtained by writing to Susan Harter, Department of Psychology, 2040 S. York Street, Denver,

Colorado 80208.

[Child Development, 1984, 55, 1969-1982. ? 1984 by the Society for Research in Child Development, Inc.

All rights reserved. 0009-3920/84/5506-0020$01.00]

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1970 Child Development

report instrument for young children,butwe more scholastically oriented skills such as

adopted a similar approach in that we soughtbeing able to spell, read, or add are better

measures of cognitive competence in the first

to identify meaningful domains in the child's

life and to construct separate subscalesand forsecond grades.

each. We also opted for utilization of a similar

The younger children's instrument also

type of question format that (a) provides a from the older version in that it con-

differs

greater range of responses for each item (four

tains no self-worth subscale. Both theory (see

choices rather than the more typical two-

Harter, 1983) and empirical findings have led

choice true/false format) and (b) reduces chil-

to the conclusion that children are not capable

dren's tendency to give the socially desirable

of making judgments about their worth as per-

response (see Harter [1982] for a more com-

sons until approximately the age of 8. The

plete description).

very concept of "personness" is not yet firmly

However, in devising a developmentally established among younger children, nor is

appropriate downward extension of the scale the notion that the self, so defined, can be

evaluated as a global entity.

for 4-7-year-olds, several aspects of our proce-

dure were different from those used with the

There is another developmental contrast

older children. First, a pictorial format was de-

that involves the degree to which we can ex-

vised rather than a written questionnaire. Ex-

pect children's self-judgments to be accurate.

perience shows that, on questionnaires, young

Developmental frameworks such as those of-

children's inability to read as well as to under-

fered by Piagetians or the proponents of

stand the items, coupled with related atten-

psychoanalytic theory would alert us that the

tional problems, attenuates both the reliability

judgments of the young child may not be real-

and validity of such instruments. In contrast,

istic. That is, young children confuse the wish

the pictorial format engages the young child's

to be competent with reality; they blur the

interest, is understandable, sustains the distinction between their ideal self-image and

child's attention, and leads to more meaning-

the real self (Stipek, 1981). Related findings

ful responses.

by Ruble and her colleagues (see Ruble, 1983)

The pictorial format also allows us to de-indicate that it is not until approximately 9

years of age that children make use of social

pict skills and specific activities concretely.

comparison for the purposes of judging their

Whereas, at older ages, trait labels and general

descriptions of skill or adequacy can be em- own competence. Thus, certain cognitive lim-

ployed-such as terms like smart, popular, itations appear to interfere with the young

child's ability to make realistic judgments

athletic, and good-looking-the young child

about the self.

has not yet acquired these forms of self-

description (see Harter [1983] for a theoretical

discussion of these developmental shifts). Given that young children may not be

Rather, the young child's self-judgmentsvery

in- accurate judges of their competence or

social acceptance, comparisons of their scores

volve the behavioral description of their

specific abilities, such as completing puzzles,

with objective indexes should not be exam-

ined as an index of the validity of the instru-

running fast, and playing with friends. There-

ment. This lack of convergence is an inter-

fore, the graphic presentation of these actions

and activities facilitates the young child'sesting finding, in and of itself, one that bears

on the self-descriptive capabilities during this

understanding of the task since these forms of

developmental period. Other forms of valid-

self-description are developmentally appro-

priate.

ity-such as discriminant, convergent, and

predictive validity-would appear to be more

Another difference involves the number appropriate, as will be demonstrated.

of versions of the scale required. At older

ages, one version can be utilized across a wide The specific content of the scale to be

range of ages. For the younger ages, however, described involves two general constructs,

it was necessary to devise one version for pre- perceived competence and perceived social

schoolers and kindergartners (4- and 5-year- acceptance. The measure contains two

olds) and a separate version for first and sec- subscales within each of these domains. Per-

ond graders (6- and 7-year-olds). This was ceived competence is divided into two sub-

necessitated by the fact that the specific skills scales, cognitive competence and physical

that define or connote competence and social competence. Social acceptance is divided into

acceptance change rather dramatically within two subscales, peer acceptance and maternal

this 4-year age range. For example, puzzles acceptance. While these particular subscales

may be indicative of cognitive competence appear to define salient domains in the life of

during the preschool and kindergarten years, the young child, obviously there are others,

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Harter and Pike 1971

three of which (paternal acceptance,

dren teacher

were white, with the remaining 4% His-

acceptance, and conduct) will appear inblack,

panic, sub- and Oriental.

sequent versions of this scale.

Scale Description

Given the structure of this scale, we

Scale structure.-The scale contains four

strongly urge that the scale not be viewed

separate as

subscales-cognitive competence,

physical

an index of self-concept or self-esteem percompetence,

se. peer acceptance, and

That is, certain judgments such as maternal

the percep- acceptance. Each subscale contains

tion of one's cognitive or physical sixcompetence

items. There are two versions of the scale,

or one's behavior may well reflect one judgments

for preschool-kindergarten and one for

about the self's capabilities. However,

first andper- second grades. These two versions

ceptions concerning the degree toare which one

not completely unique. Rather, for certain

has friends or obtains support from parentsthere

subscales, or are overlapping or common

teachers do not necessarily imply items judgments

across the two versions. Table 1 pro-

about the adequacy of the self. For example,

vides a master list of all items for each version,

one may conclude that something grouped about the according to subscale. Asterisks next

self is responsible for one's lack of to the item On

friends. number indicated which items are

the other hand, the cause may reside common in to both forms.

cer-

tain characteristics of one's peers; that is, they

As can be seen in Table 1, none of the

are not nice or are not friendly. Similarly, lack

items that define the cognitive subscales at

of parental support might be because one per-

the two developmental levels overlap. The

ceives the self as unlovable, yet, on the other

preschool-kindergarten form contains a num-

hand, one may perceive one's parents as un-

ber of rudimentary readiness skills (knowing

loving. Thus, the very basis on which chil-

colors, the alphabet, being able to count) in

dren make such judgments is an interesting

addition to performance on puzzles and ob-

empirical issue itself. However, until further

taining stars on papers. The first-second grade

research has clarified this issue, we would

version do those scholastic skills ini-

includes

well not to assume that all of these seeming

tially encountered in the early primary grades

self-judgments are based on characteristics

(reading, writing, and arithmetic).

that reside in the self. For this reason we have

For theof

urged that the scale be treated as a measure domain of physical skills, four

items

what the title indicates, perceived occur on both versions (swinging,

compe-

climbing,

tence and perceived social acceptance, skipping, and running). Two of the

rather

preschool-kindergarten

than treating it as a singular measure of "self- skills (tying shoes and

concept" or "self-esteem." hopping), however, are replaced by more ad-

vanced physical skills for the first-second

Method grade version (bouncing a ball and jumping

rope).

This particular instrument has undergone

numerous revisions in terms of scale struc- Within the domain of peer acceptance,

ture, item content, and question format, based four of the items involving friends are com-

on extensive piloting with large numbers ofmon across the two versions. Two of the items

subjects. In this article, we will restrict ouron the preschool-kindergarten version (stay-

description to the final version of the four-ing overnight and eating at friends' houses)

subscale instrument. are replaced at the first-second grade level by

others sharing toys and others sitting next to

Subjects

you. These particular social overtures in the

Subjects were 90 preschoolers (mean age

early primary grades would appear to be im-

= 4.45), 56 kindergartners (mean age = 5.54),

portant indexes of popularity.

65 first graders (mean age = 6.32), and 44 sec-

ond graders (mean age = 7.41), approximately For the domain of maternal acceptance,

equally divided by gender within each group. there are four activities or maternal behaviors

These samples provided the primary data for in common across the two age-graded ver-

the factor analyses, means, standard devia- sions (Mom takes you places you like, cooks

tions, internal consistency reliability data, and "your favorite foods, reads to you, and talks to

subscales intercorrelations reported. For an you). Two preschool-kindergarten items drop

additional sample of 77 preschoolers, 28 kin- out (Mom smiles and Mom talks to you) for the

dergartners, and 38 first and second graders, first-second grade version and are replaced by

scores for both self-report and teacher ratings Mom lets you eat at friends' and stay over-

were available. All subjects were drawn from night. These maternal acceptance items were

schools in middle-class neighborhoods. In generated from a list of the most commonly

terms of ethnic composition, 96% of the chil- mentioned behaviors by young children in re-

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1972 Child Development

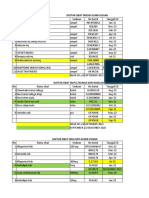

TABLE 1

ITEMS GROUPED ACCORDING TO SUBSCALE FOR EACH FORM

Subscale and Item No. Preschool-Kindergarten First-Second Grades

Cognitive competence:

1 ................... Good at puzzles Good at numbers

5 .................... Gets stars on paper Knows a lot in school

9 .................... Knows names of colors Can read alone

13 .................... Good at counting Can write words

17 ..................... Knows alphabet Good at spelling

21 ................ ..... Knows first letter of name Good at adding

Physical competence:

3 ..................... Good at swinging Good at swinging

7* ..................... Good at climbing Good at climbing

11 ................... Can tie shoes Good at bouncing ball

15* .................. Good at skipping Good at skipping

19* ..................... Good at running Good at running

23 ................... Good at hopping Good at jump-roping

Peer acceptance:

2* .................. Has lots of friends Has lots of friends

6 ................... Stays overnight at friends' Others share their toys

10* .................. .. Has friends to play with Has friends to play with

14* ................. .. Has friends on playground Has friends on playground

18* ..................... Gets asked to play with others Gets asked to play with othe

22 ..................... Eats dinner at friends' house Others sit next to you

Maternal acceptance:

4 ................... Mom smiles Mom lets you eat at friends'

8* .................. Mom takes you places you like Mom takes you places you like

12*" ........................ Mom cooks favorite foods Mom cooks favorite foods

16* ....................... Mom reads to you Mom reads to you

20 .................... Mom plays with you Mom plays with you

24* .................. Mom talks to you Mom talks to you

NOTE.-Item number refers to position of the item in the order administered to t

items common to both forms.

sponse to the question, "Tell me thethe

ple item, things

female subject would be told that

the girlthat

your mother does that let you know on theshe

child's left is good at puzzles

likes or loves you." but the child on the right is not very good at

puzzles. The child's first task is to indicate

Picture plates.-The pictures accom-

which of the two girls she is most like. After

panying each version are bound separately, as

making that decision, the child is then asked

are sets for boys and girls. Thus, there are four

to think only about the picture on that side

books of plates, both a boys' and girls' set for

and indicate whether she is a lot like that girl

the preschool-kindergarten and first-second

(the big circle) or just a little bit like that girl

grade versions. The activities depicted in

(the smaller circle). For each item there are

each item are identical for girls and boys.

more specific descriptive questions that ac-

Only the gender of the target child is differ-

company each circle, such as "Are you just

ent, so that a subject can respond to pictures

pretty good at puzzles [small circle] or really

depicting a same-gender child.

good [large circle]?" The book of plates is

Items occur in the order of cognitive com- constructed so that, as the picture for a given

petence, social acceptance, physical compe- item is presented to the child, the item de-

tence, and maternal acceptance, and continue scription to be read by the examiner sitting

to repeat themselves in that order. Withinopposite the child is printed on the back of the

each subscale, items are counterbalanced sopreceding picture (see manual [Harter & Pike,

that three of the pictures depict the most com- Note 2] for more specific instructions).

petent or accepted child on the left and three

Scoring.-Each item is scored on a four-

of them depict the more competent or ac-

point scale, where a score of 4 would be the

cepted child on the right.

most competent or accepted and a score of 1

Sample item.-The scale is individually would designate the least competent or ac-

administered. A sample item is presented in cepted. Thus, for the sample item, the child

Figure 1. The child is first read a brief state- who indicates that she is a lot like the girl on

ment about each child depicted. For the sam- the left who is good at puzzles would receive

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Harter and Pike 1973

FIG. 1.-Sample item

a score of 4. If she chose the smaller circle on Subscale reliabilities, in the form of internal

the left, she would get a 3. If she indicates that consistency coefficients, will then be pre-

she is a little like the girl on the right who is sented, followed by subscale means and stan-

not very good at puzzles, she would receive a dard deviations. Intercorrelations among sub-

2. And if she is a lot like that girl, she would scales, as well as correlations between child

get a score of 1. (These scores are designated and teacher ratings, will then be described.

on a scoring key under the verbal descriptions

provided for the examiner for each item in the Factor Pattern

picture plates.) Item scores are averaged Tables 2 and 3 present the factor pattern

across the six items for a given subscale, and based on an oblique (promax) rotation, a solu-

these four means provide the child's profile of tion that allows the factors to intercorrelate.

perceived competence and social acceptance. This solution was considered the most appro-

priate given our expectation, based on previ-

Teacher rating scale.-A teacher rating

ous findings, that there would be moderate

scale parallels the child's instrument.

Teachers rate the child in three of the four and meaningful correlations among self-

judgments in these domains. Cattell's "scree"

areas tapped on the child's version: cognitive

text, based on the magnitude of the eigen-

competence, physical competence, and peer

values, as well as interpretability, indicated

acceptance. (We did not feel that it was appro-that a two-factor solution best described the

priate to have teachers rate the maternal ac-

data from both the combined preschool-

ceptance of the child.) On this scale, teachers

kindergarten samples as well as the combined

are given a brief verbal description of each

first-second grade samples.'

item (e.g., good at puzzles, has lots of friends,

good at swinging) and then rate how true that As can be seen in Tables 2 and 3, for both

statement is on a four-point scale (really true,

groups, items generally have moderate to high

pretty true, only sort of true, and not very loadings on their designated factor, and with

true). Thus, these scores can be comparedtwo exceptions for the preschool-kindergarten

with the child's scores, depending on the pur-

sample, items do not cross-load on the other

poses of the study. factor. Loadings are somewhat higher for the

Results

first-second grade samples. (Loadings less

than .19 are not presented, for the sake of clar-

The primary results bear upon the ity.) Factor 1 is defined by the two compe-

psychometric properties of the scale. To de- tence subscales, cognitive and physical; thus

termine the factorial validity of the scale, theit is considered to reflect perceptions of gen-

factor pattern will first be presented, along eral competence. Factor 2 is defined by the

with item means and standard deviations. peer acceptance and maternal acceptance sub-

1 Initially we performed the more traditional orthogonal rotation, which also revealed a tw

factor solution. However, the oblique rotation not only seemed more appropriate conceptually b

provided a somewhat better fit.

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1974 Child Development

TABLE 2

FACTOR PATTERN AND ITEM MEANS AND STANDARD DEVIATIONS FOR THE PRESCHOOL AND

KINDERGARTEN SAMPLES COMBINED

Subscale, Item No., and Item Factor 1 Factor 2 Mean SD

Cognitive competence:

1. Good at puzzles .................... .39 3.2 .77

5. Gets stars on paper ................. .37 3.1 .95

9. Knows names of colors .............. .57 3.6 .60

13. Good at counting .................. .43 3.6 .61

17. Knows alphabet ................... .48 3.6 .67

21. Knows first letter of name ........... .58 -.33 3.6 .62

Physical competence:

3. Good at swinging .................. .19 3.6 .84

7. Good at climbing .................. .33 3.4 .77

11. Can tie shoes ..................... .42 2.8 1.12

15. Good at skipping ................ .34 3.4 .84

19. Good at running .................... .23 3.4 .76

23. Good at hopping ................... .22 .30 3.4 .75

Peer acceptance:

2. Has lots of friends .................. .36 3.2 .79

6. Stays overnight at friends'. .......... .47 3.1 .92

10. Has friends to play games with ...... .23 3.1 .86

14. Has friends on the playground ....... .36 3.2 .79

18. Gets asked to play with others....... .44 3.1 .81

22. Eats dinner at friends' house ........ .61 2.7 1.01

Maternal acceptance:

4. Mom smiles .................. .... .52 3.3 .67

8. Mom takes you places you like ...... .52 3.1 .80

12. Mom cooks favorite foods ........... .53 3.0 .75

16. Mom reads to you ................ .61 3.0 .96

20. Mom plays with you ................ .70 2.5 1.04

24. Mom talks to you ................... .62 3.1 .91

NOTE.-N = 145.

It should be noted that, since the item

scales; it is considered to reflect perceptions

of social acceptance. means for the competence subscales, in par-

Item Means a'nd Standard Deviations ticular, were skewed toward the upper end of

the scale, the range of scores was restricted,

As can be seen in Tables 2 and 3, the

which in turn attenuated the magnitude of

majority of means are in the range of 3.0-3.6,

these reliability estimates. That is, the over-

indicating that young children tend to report

whelming majority of children's item scores

relatively positive feelings of competence and

were either 3 or 4. Paradoxically, therefore,

acceptance. Standard deviations indicate that

although children responded consistently to

there is still considerable variability, even

these items in terms of scores at the upper end

though judgments are being made in the up-

of the scale, the restricted range necessarily

per ranges of the scale. The use of the upper

leads to lower statistical estimates of reliability.

ranges is not thought to reflect social desirabil-

ity response tendencies so much as the Subscale

young Means and Standard Deviations

child's blurring of the boundaries between There-

subscale means and standard devia-

ality and the wish to be competent tions

or are

ac-presented in Table 5. These subscale

cepted, as anticipated. means, like the item means, are skewed in the

direction of positive judgments, reflecting the

Reliability

tendency for young children to report rela-

Subscale reliabilities, presented in Table

tively positive feelings of competence and so-

4, were assessed by employing coefficient oa cial acceptance. Scores are somewhat higher

that provides an index of internal consistency.

for the two competence subscales, compared

If one looks at individual subscales, it can be

to the two social acceptance subscales. Con-

seen that these values range from .50 to .85.

sistent with this pattern, the standard devia-

When one combines subscales according to

tions are somewhat lower for the competence

their designated factors, these reliabilities in-

than the social acceptance subscales.

crease substantially, falling within a range of

.75-.89. The reliability of the total scale, all 24 A 4 x 4 (group x subscale) analysis of

items, is in the mid- to high .80s. variance, with subscale as a repeated mea-

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Harter and Pike 1975

TABLE 3

FACTOR PATTERN AND ITEM MEANS AND STANDARD DEVIATIONS FOR THE FIRST- AND

SECOND-GRADE SAMPLES COMBINED

Subscale, Item No., and Item Factor 1 Factor 2 Mean SD

Cognitive competence:

1. Good at numbers ................ .51 3.2 .73

5. Knows a lot in school ............. .63 3.5 .64

9. Can read alone .................. .50 3.4 .73

15. Can write words ................. .65 3.6 .58

17. Good at spelling ................. .51 3.4 .65

21. Good at adding .................. .40 3.5 .62

Physical competence:

3. Good at swinging ................ .22 3.7 .60

7. Good at climbing ................ .48 3.4 .80

11. Good at bouncing ball............ .43 3.5 .71

15. Good at skipping................. .33 3.7 .63

19. Good at running ................ .50 3.4 .70

23. Good at jumping rope ............ .40 3.1 1.02

Peer acceptance:

2. Has lots of friends ............... .67 3.1 .85

6. Others share their toys ........... .27 3.3 .78

10. Has friends to play games with ... .60 3.0 .90

14. Has friends on the playground .... .67 3.2 .89

18. Gets asked to play with others .... .72 3.1 .85

22. Others sit next to you ............ .67 3.1 .81

Maternal acceptance:

4. Mom lets you eat at friends' ...... .44 2.8 .89

8. Mom takes you places you like ... .58 3.1 .95

12. Mom cooks favorite foods ......... .63 3.1 .77

16. Mom reads to you................ .61 2.7 1.13

20. Mom lets you stay overnight...... .51 2.9 1.01

24. Mom talks to you ................ .50 3.0 .94

NOTE.-N = 104.

sure, revealed a significant effect for

calsubscale,

competence and the two social accepta

F(3,693) = 92.02, p < .001. As can be seen infor the second graders, howe

subscales

Table 5, this primarily indicates thatdid scores

not fit this pattern.

were significantly higher for the two compe-

Correlations

tence subscales, where most means were at orbetween Child and Teacher

Ratings

close to 3.4, than for the two social acceptance

The intercorrelations between child and

subscales where the means ranged from 2.8 to

3.1. While there was no group effect,teacher judgments were calculated across all

there

was a group x subscale interaction subjects

that since

ap- differences between age groups

were

pears primarily to be because, for the small.

first and These values were .37 (p < .001)

forscores

second graders only, peer acceptance cognitive competence, .30 (p < .005) for

physical

were higher than maternal acceptance competence, and .06 for social accep-

scores,

which was not the case for the tance. While these correlations are moder-

younger

groups, F(9,693) = 5.85, p < .01. ately weak, the pattern indicates that agree-

ment between pupil and teacher is highest in

Intercorrelations among Subscales the cognitive competence domain, next high-

Table 6 presents the intercorrelations

est in the physical domain, and virtually negli-

among the four subscales for each of thefor

gible four

peer acceptance.

groups. The clearest patterns obtained, consis-

Validity

tent with the factor analysis, are for Data

the two

Convergent validity.-As one index of

competence scales to intercorrelate moder-

ately for each group and for the two social of children's judgments, we con-

the validity

acceptance subscales to intercorrelate some-

ducted an inquiry after the measure had been

what more highly. Among preschoolers,administered

kin- asking children the bases for

dergartners, and first graders, peer their responses in the two competence do-

acceptance

also correlates moderately with bothmains. Children were asked, "How do you

cognitive

and physical competence, as does know maternal

you are good at/not good at [depending

acceptance. The correlations between on physi-

the child's initial response] this [activity

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

[ e

1J

Se - rt c

z oO C~CoO fx 4

?

SC

[-,

C/2

V

U

0

U

"0

z

o / )"a

C1 1

EzJ 4 U

0z

a, r r"0..~c

*3 * V.

p;a

z

,<

U "0

o cc b"

?r o Wu0 V~ a" c~

ZL~Z

.e . (

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Harter and Pike 1977

TABLE 5

SUBSCALE MEANS AND STANDARD DEVIATIONS FOR EACH GROUP

COMPETENCE SUBSCALES ACCEPTANCE SUBSCALES

Cognitive Physical Peer Maternal

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

Preschool (N = 90) ........ 3.4 .45 3.2 .49 3.0 .56 3.1 .59

Kindergarten (N = 56) ..... 3.6 .41 3.4 .35 2.9 ,56 2,9 ,58

Preschool and

kindergarten combined .. 3.5 ,43 3.3 .46 2.9 .56 3.0 .59

First grade (N = 65) ....... 3.4 .37 3.4 .38 3.1 .55 2.8 .60

Second grade (N = 44) .... 3.5 .31 3.4 .40 3.1 .55 2.8 .56

First and second

grades combined ...... 3.4 .35 3.4 .39 3.1 .55 2.8 .58

TABLE 6

INTERCORRELATIONS AMONG SUBSCALES FOR EACH GROUP

Cognitive Physical Peer

Competence Competence Acceptance

Physical competence:

Preschool .............. .56***

Kindergarten ........... .43***

First grade ............. .55***

Second grade............ .43**

Peer acceptance:

Preschool ............... .56*** .48***

Kindergarten ........ .... .45*** .42***

First grade ............. . 59*** ,50***

Second grade........... .32* 08

Maternal acceptance:

Preschool ...........,. .48*** .43*** .64***

Kindergarten ........... .27* .50*** .62***

First grade ............. .51"** ,48*** .66***

Second grade ........... .32* .00 .80***

* p < .025,

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

specified]? How can you tell?" The purpose words right on a test," "the teacher tells me";

of this procedure was to determine (a) (b) possess/perform component skills (11%):

whether children could give reasons, and if "I sound out the letters," "I memorize the

so, (b) whether they were compelling in the words," "I draw straight letters"; (c) specific

sense that they bolstered or supported the par- demonstrations (32%): "I started reading

ticular self-judgment they had given previ- when I was 3," "I can write words like 'cat'

ously. and 'dog,' " "I can read two whole books," "I

can write in handwriting," "I don't have to

Systematic data (Chao, Harter, Adams, &

read out loud, I can think it up in my mind";

Strop, Note 3) were available for a sample of 43

(d) routes to developing skills (20%): "I prac-

first graders and 48 second graders who were

tice a lot," "I can spell 'cause I read a lot," "I

asked about three cognitive skills (reading,

practice on my flash cards," "My mom and

spelling, and writing) and two physical skills

(climbing and running). For the cognitive dad helped me learn how"; and (e) habitual

activity (14%): "I read a lot at home," "I do

skills, 96% of the children readily gave

writing every day," "I've spelled a lot before."

specific reasons for why they felt that they

were competent or not competent. These fell In the physical domain, the categories

into the following five categories for which differed somewhat from the cognitive domain,

sample responses are provided: (a) perfor- and there were also within-domain differ-

mance feedback (19%): "I get the hardest ences in the percentage of responses for

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1978 Child Development

climbing and running. The categories, includ-significantly lower than the scores (mean =

ing sample responses, were as follows: (a) 3.3)

so- of those who were promoted, t(22) = 3.5,

cial comparison (51% for running, 2% pfor < .005.

climbing): "I got to race a lot and win," "I wasFor the social domain, we examined the

first place in running in gym," "The boys say

perceived peer acceptance scores for kinder-

they can run faster but at races I can beat

gartners and first and second graders who re-

them," "I'm the best in climbing races"; (b)

cently moved and who had attended this par-

habitual activity (18% for running; 31% for ticular school for less than 2 months. We

climbing): "I run a lot," "I practice jogging,"

hypothesized that these children would have

"I do a lot of feet work in the gym," "I climb a

lower peer acceptance scores than children

lot on bars," "I've been climbing for a longwho had been in the school for a minimum of

time"; (c) specific demonstrations (26% and

1 year. The scores of the 10 "new" children

52%, respectively): "I can run around were the significantly lower (mean = 2.9) than a

block a couple of times," "I run a lot in foot-

comparison group of children, matched for

ball and tag 'em down," "I climb up to my

age and gender, whose scores (mean = 3.3)

treehouse," "I can do chin-ups"; (d) some- indicated greater peer acceptance, t(18) = 2.7,

body teaches (1% and 40%, respectively):

p< .01.

"Mom taught me," "Somebody taught me to

climb the jungle gym"; and (e) don't injureIn the physical domain, we have exam-

self (4% and 3%, respectively): "I hardly ever

ined the validity issue with regard to the

trip and fall," "I don't fall off and scratch my-

scores of children who were preterm infants.

self." (A total of 96% of the responses about

Prematurity is frequently associated with de-

running and 97% of the responses about velopmental lags in gross motor skills. From

climbing could be coded in these categories.)

preschools that had participated in our stud-

ies, we were able to obtain information from

Therefore, for both the cognitive and teachers as to which of the children they were

physical domains, the findings demonstratecertain had been born preterm. These were

that children can provide very definite rea-

compared with a sample of preschoolers who

sons for their alleged competencies; more-

were known to have been full-term infants.

over, they volunteer these readily. Although

Group differences in teacher ratings for the

we do not have systematic data for the youn-

physical domain were considerably lower for

ger ages, many of these children spontane-

the preterm group (mean = 2.3) compared

ously elaborated on (and sometimes demon-with the full-term group (mean = 3.1), t(14) =

strated) their prowess during the course of the

3.4, p < .005. Correspondingly, the physical

normal administration, and these comments competence scores of the eight children who

reveal that they too have specific reasons had

for been preterm infants were found to be

their judgments. Furthermore, although lower

the (mean = 2.8) than the scores (mean =

sample responses presented were those 3.3) of-of children who had been full-term in-

fered by children judging themselves to be fants, t(14) = 2.9, p < .01.

competent, children rating themselves as in-

competent also gave plausible responses (e.g., We have begun to examine the validity of

"I can't spell words on tests," "I draw crooked

the maternal acceptance subscale in one study

letters," "I watch too much TV," "I can't doof childhood depression (Harter & Wright,

Note 4). Our prediction was that depression in

twirls on the jungle gym," "I'm the last when

we run"). Therefore, the overall pattern is young

one children (defined in terms of dysphoric

of convergence between the initial perceivedmood and lack of energy or interest) would be

competence judgments and the reasons chil- directly related to lack of maternal acceptance.

dren offered for these perceptions. In this study, we did not have a group of se-

verely depressed children. However, within

Discriminant validity.-As one test the of normal range of scores for kindergartners

validity in the cognitive domain, we made andthe first and second graders, we found the

prediction that children held back in first

correlation between our depression/cheer-

grade for academic reasons should score lower

fulness measure and maternal acceptance to

on the cognitive competence subscale than be .48, p< .001.

those who were promoted to the second

grade. Over a 2-year period we identified 12 Finally, although our new paternal accep-

children who had been held back, and we tance scale has not yet been integrated into

compared these children with a sample ofthe12 versions reported on in this paper, an in-

children, matched on age and gender, fromteresting study has just been completed on

the pool of those who had been promoted. young children with abusive fathers (Kelty,

The cognitive competence scores of those Note 5). Examining 11 such children, it was

held back (mean = 2.4) were found to found

be that their fathers' acceptance scores

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Harter and Pike 1979

quartiles

(mean = 2.6) were significantly lower than (3.6 and 2.3, respectively, for the

the scores (mean = 3.2) of a groupcognitive

of 13 domain), differences in the per-

ceived cognitive competence of these two

nonabused children from the same preschool,

t(22) = 3.4, p < .005. subgroups are highly significant (3.8 vs. 2.6),

t(102) = 5.9, p < .001. Thus, for children who

Predictive validity.-In one study, Bierer

fall at either end of the competence con-

(1981) examined the relationship between

tinuum, there is much more convergence be-

first and second graders' perceived cognitive

tween teacher and child ratings than for those

competence and their preference for chal-

falling within the mid-ranges of the distribu-

lenge on a behavioral task involvingtion.

subjects'

choice of puzzles, varying in difficulty level.

It was initially hypothesized that per- Discussion

ceived cognitive competence would predict

difficulty-level preferences. This correlation The attempt to devise a pictorial self-

(r = .42) was significant, p < .005. However, report measure of young children's percep-

further examination indicated that it was at- tions of their competence and social accep-

tenuated because a subgroup of children was tance would appear to have been successful.

present whose perceptions of their compe- Children eagerly respond to the pictorial for-

tence appeared to be inflated-that is, whose mat, they comprehend the items, and the

scores were at least 1.2 higher (on a four-point psychometric properties of the scale seem

scale) than their teacher's ratings of their cog- sound. The item scores and standard devia-

nitive competence on the same items. This tions revealed reasonable variability, indicat-

subgroup tended to select puzzles that were ing that the scale is sensitive to individual

much easier than one would expect, based on differences in perceived competence and ac-

their perceived competence, although theirceptance among young children.

choices were consistent with their actual

The reliability, as assessed through in-

competence, as judged by the teacher.dexes

In of internal consistency, was found to be

terms of the validity question, these findings

acceptable. Several forms of validity were also

revealed ti.-+ for pupils whose ratingsexamined.

are In normative samples, the reasons

either congruent or lower than the teachers,

children gave for their self-perceptions were

their perceived cognitive competence is pre-consistent with their judgments on the items

dictive of their actual behavior. That is, these

themselves and were quite plausible. This

perceptions appear to mediate their behav-

suggests that the ratings are valid, in the sense

ioral preference for challenge. However, the

that young children's self-perceptions of their

presence of overraters in the sample competencies

at- appear to be based on specific

tenuates the predictive validity of this sub-

behavioral referents.

scale.

Correlations between child and teacher The findings also indicated that scores on

the various subscales do discriminate be-

ratings.-In the introduction, it was sug-

tween groups of children predicted to differ in

gested that the tendency of young children to

be somewhat inaccurate observers of their each domain. For example, children new to a

own competencies does not necessarily indictschool setting reported lower peer acceptance

than those who have attended the school for a

the validity of the instrument. The findings

presented indicate that the correlations be-year or more. Children who have been held

tween self- and teacher ratings in the two back a grade for academic reasons reported

lower perceived cognitive competence than

competence domains are significant, although

those experiencing normal promotion. Chil-

they are moderately weak, at best, consistent

with our expectation. Nevertheless, we did dren who were preterm infants, with related

delays in motor development, had lower

find that, for the competence domains, teacher

and child ratings were more highly correlatedphysical competence scores than children

within the same domain (cognitive = .37, who had been born full-term. Thus, the vari-

ous subscales would appear to discriminate

physical = .30) than they were across the two

domains (teacher-cognitive/pupil-physical = clearly between a given subgroup for whom

there is reason to expect relatively low scores

.11; teacher-physical/pupil-cognitive = .16).

and children, matched for age and gender,

Thus, while we have not relied heavily on this

from

type of external validity, the pattern suggests the normative sample. In addition, chil-

that children's competence judgments are re- dren judged by teachers to be very competent

lated to their actual competence. scored considerably higher than those whom

teachers judged to be low in competence.

Moreover, when one examines the per-

ceived competence scores of children whom At a more theoretical level, the factor pat-

tern obtained with this instrument is of inter-

the teachers rate as in the top and bottom

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1980 Child Development

more critical of others than of the self (Gesell

est, since it provides certain clues with regard

to the structure of the young child's self-

& Ilg, 1946; Stipek, 1981).

descriptions. The two-factor solution revealed

With regard to competence judgments,

one factor comprised of the cognitivethe and

verbal interview data revealed that self-

physical competence subscales and a second

perceptions of skill were directly tied to

factor comprised of the peer and maternal ac-

ceptance subscales. We have labeled these

specific behaviors emitted by the self. We

have yet to inquire about the bases for judg-

factors "general competence" and "social ac-

ments concerning social acceptance. How-

ceptance." The single competence factor im-

ever, we have collected interview data on the

plies that young children do not make a clear

distinction between what we identified as perceived routes to both competence and so-

cial acceptance. We have systematically asked

cognitive and physical domains. Competence

children what the child depicted as incompe-

at one type of skill is associated with compe-

tent or socially unaccepted would have to do

tence at the other. One is either "good at do-

to become like the child pictured as compe-

ing things" or one is not. These skill domains,

tent or accepted. The responses to compe-

however, are distinguished from social accep-

tence involve self-improvement, primarily

tance by peers and by mother.

through instruction (I learn from the teacher),

The structure of young children's self- or personal effort (I practice a lot, try harder,

perceptions across these domains is less dif-etc.), with a gradual shift toward high levels of

ferentiated than the structure obtained for personal effort over the age span of 4 to 7

older children (Harter, 1982) where we find (Chao, Harter, Adams, & Strop, Note 3).

that cognitive and physical skills clearly In contrast, the routes to peer acceptance

define separate factors.2 This developmental

involve behaviors designed to influence

difference is consistent with findings indicat-

others. Here we find a gradual shift from rela-

ing that the structure of the self becomes more

tively naive solutions (find friends, just ask

differentiated with age (see Harter, Note 1). In

people to be your friends) to social strategies

addition, the self-structure would appear to be

such as being nice, helpful, polite, and kind.

more highly related to mental age than The spontaneous mention of these strategies

chronological age. In one study we employedincreases from a low of 18% among 4-5-year-

retarded children whose mental ages ranged olds to 46% in first graders and 65% in second

from 5 to approximately 8, the same range one

graders.

would expect for the young normal-IQ chil-

dren in the present study. Consistent with the These findings are interesting in light of

findings reported here, the retarded pupils the recent emphasis on social skills (see

did not make a distinction between the cogni-Asher, Oden, & Gottman, 1977; Bash &

tive and physical competence domains, Camp, 1980; Gottman, Gonso, & Rasmussen,

whereas social acceptance defined a separate 1975; Hartup, 1979, 1983; Ladd & Oden,

factor (Silon & Harter, in press). 1979; Spivack & Shure, 1974). Across these

studies it has been revealed that a variety of

Inspection of the subscale means indi- social skills are associated with peer popular-

cates a general tendency for scores to be ity and social acceptance. Moreover, they re-

skewed toward positive self-evaluations, al- veal that elementary school children possess

though this tendency was greater for the two an awareness of how social skills influence

competence subscales than for the two social

their acceptance by peers. Our own findings

acceptance subscales. This pattern appears suggest that, at the youngest ages, children

plausible since judgments about one's com- have not yet acquired the knowledge concern-

petencies may be more intimately related to ing this relationship in the social domain, al-

one's appraisal of the self, in contrast to judg-

though they do seem to appreciate the need

ments about social acceptance, which may be for skill development in the cognitive and

influenced by one's view of the characteristics

physical domains. Gradually, over the early

of these particular others. Since fantasies grades, they come to appreciate the need to

about the ideal self intrude upon judgments of employ social strategies in order to obtain

the real self at this age level, the competence friends.

scores are likely to be somewhat inflated. To

the extent that social acceptance items pull for This pattern raises numerous questions

judgments of others, these scores would be for further study. For example, in what ways

expected to be lower since findings have dem- are social skills different from those in the cog-

onstrated that young children are likely to be nitive and physical domains? Why should the

2 In the revision of the original perceived competence scale, we have determined that children

age 8 and older make distinctions among five domains (scholastic, athletic, appearance, social accep-

tance, and conduct), as revealed by a clean five-factor solution (Harter, 1983).

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Harter and Pike 1981

understanding of these two types ofand interest

skills pur- for age-appropriate activities. To

the extent

sue a different developmental course? In ad- that the child's mood and energy

level may beof

dition, how do the perceived characteristics critical mediators of behaviors

others influence one's judgments ofleading

social to ac-

the development of new skills, it

would be important

ceptance? In light of these considerations, we to assess these predictors

would urge that our instrument not as be

early as possible. Furthermore, a domain-

treated

specific

solely as a measure of "self-concept" sincemeasure

the allows one to determine

social acceptance construct tapped may

which in- best predict the mediators and

domains

behaviors be-

volve a number of dimensions extending of interest.

yond one's perceptions of the self per se.

Second, the degree to which a young

Differences between the two child's

compe-judgments are inaccurate might be im-

tence domains and the social domainportant to examine. Normative or age-

of peer

appropriate

acceptance were also revealed in the examina- distortions may not be cause for

tion of the accuracy of children's judgments.concern. However, it may be important to de-

The correlations between teacher and child tect either extreme inflation of one's abilities

ratings for the two competence domains were or the unrealistic portrayal of oneself as ex-

significant, though moderately weak; how- tremely incompetent. Furthermore, a child

ever, they were negligible in the social do- may show these inaccuracies in some domains

main. The greater congruence in the compe- more than others, and these particular distor-

tence domain may be because of clearer tions may well have behavioral correlates.

sources of information on which to base one's Findings with somewhat older children indi-

judgments. Our findings suggest that, in the cate that, by third and fourth grades, there are

cognitive domain, performance feedback is behavioral patterns associated with extreme

beginning to emerge as a criterion for perfor- tendencies to overrate or underrate one's cog-

mance, whereas in the physical domain, social nitive competence. For example, both of these

comparison is becoming the basis for judg- inaccurate subgroups tend to avoid behavioral

ments of competence. Of particular interest is preference for challenge compared with those

the finding that social comparison is used children who accurately rate their compe-

more frequently for the activity of running, tence (Bierer, 1981).

which appears to be a more competitive activ- Third, there would appear to be a need

ity, than for climbing. for an instrument to assess the self-

Our data are consistent with Ruble and perceptions among special subgroups of chil-

Frey's (Note 6) findings that, in the domain of dren who may be under particular types of

academic achievement, social comparison is stress. Children of divorce, of abusive parents

not consistently employed in the early grades. and with learning disabilities or physica

Our findings also indicate that social compari- handicaps are all special groups that have

son effects may be somewhat domain-specific come to the recent attention of basic research-

since social comparison does form the basis ers, clinicians, and those engaged in socia

for judgments of certain physical skills. We policy. However, as has been pointed out, no

have yet to examine the bases on which chil- all children necessarily suffer from events that

dren make judgments in the social domain. have been categorically identified as stressful

However, the lack of congruence between (Garmezy & Rutter, 1983). A variety of indi

child and teacher ratings of social acceptance vidual difference variables, including self

may result from several factors: performance concept, have been implicated as factors in-

feedback may be less salient, children may be fluencing the child's ability to withstand stress

less able to employ social comparison in this and cope adaptively. Thus, a domain-specific

domain, and/or children and adults may em- measure might well be useful in predicting

ploy different criteria. Further research in this children's reactions with an eye toward deter

area would be fruitful. mining which type of profile is associated

with resiliency and adaptation, or its

Finally, to what uses might such an in- counterpart. In conclusion, although there are

strument be put, particularly given the several theoretical issues requiring further re-

qualification that young children's judgments search, we believe that there are a number of

are not very accurate? First, among normative

uses to which this instrument might well be

samples, scores may be useful in predicting

put in order to illuminate our understanding

behaviors, motivations, and/or emotional reac-

of the young child.

tions of interest. Our own findings (Harter &

Wright, Note 4) indicate that the social accep- Reference Notes

tance subscales, particularly the maternal sub-

scale, are significantly correlated with the 1. Harter, S. Supplementary description of the

child's self-reported mood as well as energy Self-Perception Profile for Children: Revision

This content downloaded from

154.59.124.141 on Sun, 15 Jan 2023 02:38:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1982 Child Development

of the Perceived Competence Scale for Chil- in children. Child Development, 1975, 46, 709-

dren. Unpublished manuscript, University of718.

Denver, 1983. Harter, S. The perceived competence scale for chil-

2. Harter, S., & Pike, R. Procedural manual to ac-dren. Child Development, 1982, 53, 87-97.

Harter, S. Developmental perspectives on the self-

company the Pictorial Scale of Perceived Com-

petence and Social Acceptance for Young Chil- system. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), P. H.

dren. Unpublished manuscript, University ofMussen (Series Ed.), Handbook of child psy-

Denver, 1983. chology. (Vol. 4): Socialization, personality,

3. and social development. New York: Wiley,

Chao, C., Harter, S., Adams, P., & Strop, J. Di-

mensions underlying children's perceptions of1983.

competence. Unpublished data, University Harter,

of S. Competence as a dimension of self-

Denver, 1983. evaluation: Toward a comprehensive model of

4. Harter, S., & Wright, K. The relationship be- self-worth. In R. Leahy (Ed.), The development

tween social support, depression, and young of the self. New York: Academic Press, in

children's perceptions of competence and so-press.

Hartup, W. W. Peer relations and the growth of so-

cial acceptance. Unpublished manuscript, Uni-

versity of Denver, 1984. cial competence. In M. W. Kent & J. E. Rolf

5. Kelty, E. Perceived competence and social ac-(Eds.), The primary prevention of

ceptance in young children of abusive and non-psychopathology. (Vol. 3): Promoting social

abusive parents. Unpublished manuscript, competence and coping in children. Hanover,

University of Colorado, 1983. N.H.: University Press of New England, 1979.

6. Ruble, D. N., & Frey, K. S. Self-evaluation Hartup,

and W. W. Peer relations. In E. M. Hethering-

social comparison in children: Developmentalton (Ed.), P. H. Mussen (Series Ed.), Handbook