Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BS5930-2015 152

BS5930-2015 152

Uploaded by

Ford cellOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BS5930-2015 152

BS5930-2015 152

Uploaded by

Ford cellCopyright:

Available Formats

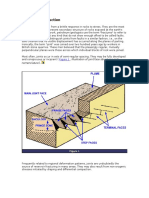

Discontinuities within the rock mass are, in most cases, of primary importance to

the rock's overall engineering properties and the maximum possible amount of

information from the investigation should be identified and reported as shown

in Table 30. A number of different types of discontinuity can be recognized as

given in Table 29. Full and accurate description of recovered cores should be

carried out and more frequent use should be made of the borehole itself with

downhole logging (geophysical, scanning, see Section 5) or cameras. In addition,

exposures, whether existing or created for the investigation, should be used

wherever practicable to inspect the in-situ mass.

NOTE 1 A distinction can be drawn between "mechanical discontinuities", which

are already open and present in the rock, and "incipient discontinuities", which are

inherent potential planes of weakness.

NOTE 2 Full recommendations for the recording of discontinuities are given

in DIN 4022-1, ISRM, 1978 [65], Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology, 1977 [66]

and ASTM D4879-89. Additional recommendations for describing discontinuities are

given in BS EN ISO 14689-1:2003, 4.3.3.

Free moisture or water flow visible at individual spots or from discontinuities

should be described as recommended in BS EN ISO 14689-1:2003.

Table 29 Types of discontinuity

Type of discontinuity Description

Joint A discontinuity in the body of rock along which there

has been no visible displacement. Joints are

synonymous with fissures in soils.

Fault A fracture or fracture zone along which there has

been recognizable displacement.

Bedding fracture A fracture along the bedding (bedding is a surface

parallel to the plane of deposition).

Cleavage fracture A fracture along a cleavage (cleavage is a set of

parallel planes of weakness often associated with

mineral realignment).

Induced fracture A discontinuity of non-geological origin, e.g. brought

about by coring, blasting, ripping, etc.

Incipient fracture A discontinuity which retains some tensile strength,

which might not be fully developed or which might

be partially cemented. Many incipient fractures are

along bedding or cleavage.

The recording of induced and incipient discontinuities is important as they can

indicate weakness within the mass, but they should not be included within the

assessment of fracture state, see 36.4.4. If incipient or induced fractures are

included in the fracture state, this should be clearly stated on the borehole log.

NOTE 3 The conventional exclusion of such integral discontinuities from reported

indices is conservative, but only for foundation studies; for bulk excavation studies,

for instance, it might be preferable to include them.

NOTE 4 Discontinuities usually occur in more than one direction in a rock mass, and

might be present as distinct sets. Borehole cores provide essentially one dimensional

data on discontinuity spacing; exposures or orientated cores are usually needed for

full evaluation of the discontinuity pattern.

The following features of discontinuities should be described

(see 36.4.3.2 to 36.4.3.9). The amount of detail included depends on the quality

of the exposure or core, whether it is representative and the requirements of

the problem in hand. The descriptive terms are summarized in Table 29, which

defines the terms in the order in which they should be used in a description.

You might also like

- De Freitas, M. H. Watters, R. J. (1973) - Some Field Examples of Toppling Failure.Document19 pagesDe Freitas, M. H. Watters, R. J. (1973) - Some Field Examples of Toppling Failure.Yonathan MolinaNo ratings yet

- Core Logging ProcedureDocument17 pagesCore Logging ProcedurePushpendra Chouhan100% (1)

- Core Logging Manual Template - 25july2017 - DraftDocument57 pagesCore Logging Manual Template - 25july2017 - DraftJuan Ricardo Torales100% (1)

- McClay, 1992-Glossary of Thrust Tectonics Terms PDFDocument15 pagesMcClay, 1992-Glossary of Thrust Tectonics Terms PDFhadi50% (2)

- Resúmen 2Document29 pagesResúmen 2moranrubyNo ratings yet

- ANGELIER, 1994. Fault Slip Analysis and Palaeostress Reconstruction. (HANCOCK, P.L., 1994. Continental Deformation, Pp. 53-100) PDFDocument48 pagesANGELIER, 1994. Fault Slip Analysis and Palaeostress Reconstruction. (HANCOCK, P.L., 1994. Continental Deformation, Pp. 53-100) PDFDedehrbc67% (3)

- Geology Field ReportDocument13 pagesGeology Field ReportSibeshKumarSingh100% (8)

- Rock SlopesDocument9 pagesRock SlopesAndrew ReidNo ratings yet

- Field ManualDocument37 pagesField ManualpleyvazeNo ratings yet

- Sibson, 1986 PDFDocument17 pagesSibson, 1986 PDFBrayamQuinteroNo ratings yet

- Identification and CharacterisationDocument7 pagesIdentification and Characterisationtie.wangNo ratings yet

- 13 Mechanical Properties of RocksDocument18 pages13 Mechanical Properties of RocksSlim.BNo ratings yet

- Summary Report Rock LoggingDocument8 pagesSummary Report Rock LoggingJoshua DiazNo ratings yet

- Prehensive Fracture Evaluation Using Wireline Borehole Imager and Array Acoustic ToolsDocument17 pagesPrehensive Fracture Evaluation Using Wireline Borehole Imager and Array Acoustic ToolsHerry SuhartomoNo ratings yet

- WWW - MINEPORTAL.in: Online Test Series ForDocument31 pagesWWW - MINEPORTAL.in: Online Test Series ForSheshu BabuNo ratings yet

- WWW - MINEPORTAL.in: Online Test Series ForDocument31 pagesWWW - MINEPORTAL.in: Online Test Series ForSusil SenapatiNo ratings yet

- Joints & FracturesDocument14 pagesJoints & Fracturesfiqia nchaNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 148Document1 pageBS5930-2015 148Ford cellNo ratings yet

- Topic 2: Ground Geological Faults and Their Effects On BuildingDocument8 pagesTopic 2: Ground Geological Faults and Their Effects On BuildingVincent NG'ETICHNo ratings yet

- Kuliah 7. DiscontinuitiesDocument55 pagesKuliah 7. DiscontinuitiestrumanNo ratings yet

- Geo PrefiDocument8 pagesGeo PrefiAirish ArgoncilloNo ratings yet

- Fault and FoldDocument42 pagesFault and FoldUtkarsh Sharma100% (1)

- Reinforcement of Rock Slopes With Plane Wedge FailureDocument12 pagesReinforcement of Rock Slopes With Plane Wedge FailureJampani HymavathiNo ratings yet

- Brittle MicrotectonicsDocument19 pagesBrittle MicrotectonicsPaul Quispe SolanoNo ratings yet

- 14448Document12 pages14448CgpscAspirantNo ratings yet

- Strike-Slip Basins - Nilson & Sylvester - 1995Document32 pagesStrike-Slip Basins - Nilson & Sylvester - 1995geoecologistNo ratings yet

- JL-85-March-April The Cause of Cracking in Post-Tensioned Concrete Box Girder Bridges and Retrofit Procedures PDFDocument58 pagesJL-85-March-April The Cause of Cracking in Post-Tensioned Concrete Box Girder Bridges and Retrofit Procedures PDFAnonymous DlVrxSbVk9100% (1)

- Extensional Fault Arrays in Strike-Slip and Transtension: John W.F. WaldronDocument12 pagesExtensional Fault Arrays in Strike-Slip and Transtension: John W.F. WaldronIvan Hagler Becerra VasquezNo ratings yet

- 12 - Chapter 4 PDFDocument61 pages12 - Chapter 4 PDFMd Imroz AliNo ratings yet

- 1111 MergedDocument12 pages1111 MergedMA. ANGELINE GRANADANo ratings yet

- Wilsonetal 2009 JSGNukhul NormalfaultsDocument18 pagesWilsonetal 2009 JSGNukhul Normalfaultsakun laptopNo ratings yet

- SPWLA 1980 vXXIn2a1Document11 pagesSPWLA 1980 vXXIn2a1amin peyvandNo ratings yet

- Topic 5 June 2016 V3Document23 pagesTopic 5 June 2016 V3Nicat SəfərliNo ratings yet

- 10 Detection and Prediction of FracturesDocument80 pages10 Detection and Prediction of Fracturesh ang q zNo ratings yet

- Rel Pub Mewer14 3Document19 pagesRel Pub Mewer14 3Tufan TığlıNo ratings yet

- 02 Rock Mass Classification PDFDocument23 pages02 Rock Mass Classification PDFAlexer HXNo ratings yet

- Listric Normal FaultsDocument15 pagesListric Normal FaultsVaibhavSinghalNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Blocky RocksDocument69 pagesGroup 3 Blocky RocksArlene Joy UbaldoNo ratings yet

- Brittle Microtectonics Principles and PR PDFDocument21 pagesBrittle Microtectonics Principles and PR PDFMartin GriffinNo ratings yet

- 1998 Mitra Foreland Basement-Involved StructuresDocument40 pages1998 Mitra Foreland Basement-Involved StructuresLucas ContalbaNo ratings yet

- Huang Et Al-2017-Journal of Geophysical Research - Solid EarthDocument20 pagesHuang Et Al-2017-Journal of Geophysical Research - Solid EarthOlvi meltiNo ratings yet

- Active Fault Crossings: Quantifying Surface Faulting Hazard For Lifeline DesignDocument10 pagesActive Fault Crossings: Quantifying Surface Faulting Hazard For Lifeline DesignMohammad AshrafyNo ratings yet

- Structural Styles, Their Plate-Tectonic Habitats, and Hydrocarbon Traps in Petroleum ProvincesDocument43 pagesStructural Styles, Their Plate-Tectonic Habitats, and Hydrocarbon Traps in Petroleum ProvincesGhassen Laouini100% (1)

- Some Practical Crack Path Examples: Les P. PookDocument7 pagesSome Practical Crack Path Examples: Les P. PookCarlos Ramón Plazaola LorioNo ratings yet

- Lect 4 Discontinuities 2021Document47 pagesLect 4 Discontinuities 2021nik amriNo ratings yet

- Fractures & Brittle Deformation: Dept. of GeologyDocument33 pagesFractures & Brittle Deformation: Dept. of GeologynikenNo ratings yet

- Effect of Formations Anisotropy On Directional Tendencies of Drilling SystemsDocument10 pagesEffect of Formations Anisotropy On Directional Tendencies of Drilling SystemsMejbahul SarkerNo ratings yet

- Global Extraction Sequences in Sublevel Stoping: E VillaescusaDocument9 pagesGlobal Extraction Sequences in Sublevel Stoping: E Villaescusaazimi32No ratings yet

- Design of Caving SystemsDocument4 pagesDesign of Caving SystemsYojan Ccoa CcopaNo ratings yet

- QJEGH - 2021 - CHALK All We Need Is A Fracture LogDocument28 pagesQJEGH - 2021 - CHALK All We Need Is A Fracture LogJack WelchNo ratings yet

- Materi - Rock Mass ClassificationDocument17 pagesMateri - Rock Mass ClassificationAdella SyaviraNo ratings yet

- Ch5 Structural Geology Folds Faults Joints For 2022 2023 OnlyDocument4 pagesCh5 Structural Geology Folds Faults Joints For 2022 2023 OnlyYousif MawloodNo ratings yet

- Failure Modes of Rocks Under Uniaxial Compression Tests - HBRP PublicationDocument8 pagesFailure Modes of Rocks Under Uniaxial Compression Tests - HBRP PublicationVijay KNo ratings yet

- Structural Geology LabDocument54 pagesStructural Geology Lab20pwmin0871No ratings yet

- Nomenclature and Geometric Classification of Cleavage Transected Folds-T.e. JohnsonDocument14 pagesNomenclature and Geometric Classification of Cleavage Transected Folds-T.e. JohnsonEdilberAntonyChipanaPariNo ratings yet

- Cruden 1977 - Describing The Size of DiscontinuitiesDocument5 pagesCruden 1977 - Describing The Size of DiscontinuitiesKukuh Vivian Tri AdhitamaNo ratings yet

- Balancing IN MAPPINGDocument34 pagesBalancing IN MAPPINGGEOLOGIST_MTA100% (1)

- Jurnal Asing Geostruk Acara 1 Bagian 2Document17 pagesJurnal Asing Geostruk Acara 1 Bagian 2efendidahlan964No ratings yet

- RSR (Rock Structure Rating)Document7 pagesRSR (Rock Structure Rating)resky_pratama_99AdeNo ratings yet

- Vasilev2016 Interference TestDocument28 pagesVasilev2016 Interference TestAmr HegazyNo ratings yet

- Tectonic PlatesDocument43 pagesTectonic PlatesPaul Quispe Solano0% (1)

- Fault Zone Dynamic Processes: Evolution of Fault Properties During Seismic RuptureFrom EverandFault Zone Dynamic Processes: Evolution of Fault Properties During Seismic RuptureMarion Y. ThomasNo ratings yet

- Earthquake isolation method with variable natural frequencyFrom EverandEarthquake isolation method with variable natural frequencyNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 235Document1 pageBS5930-2015 235Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 238Document1 pageBS5930-2015 238Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 234Document1 pageBS5930-2015 234Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 233Document1 pageBS5930-2015 233Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 305Document1 pageBS5930-2015 305Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 312Document1 pageBS5930-2015 312Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 236Document1 pageBS5930-2015 236Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 223Document1 pageBS5930-2015 223Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 307Document1 pageBS5930-2015 307Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 311Document1 pageBS5930-2015 311Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 306Document1 pageBS5930-2015 306Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 310 PDFDocument1 pageBS5930-2015 310 PDFFord cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 227Document1 pageBS5930-2015 227Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 308Document1 pageBS5930-2015 308Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 231Document1 pageBS5930-2015 231Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 230Document1 pageBS5930-2015 230Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 232Document1 pageBS5930-2015 232Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 225Document1 pageBS5930-2015 225Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 224Document1 pageBS5930-2015 224Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 215Document1 pageBS5930-2015 215Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 226Document1 pageBS5930-2015 226Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 218Document1 pageBS5930-2015 218Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 220Document1 pageBS5930-2015 220Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 219Document1 pageBS5930-2015 219Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 222Document1 pageBS5930-2015 222Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 221Document1 pageBS5930-2015 221Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 217Document1 pageBS5930-2015 217Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 216Document1 pageBS5930-2015 216Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 212Document1 pageBS5930-2015 212Ford cellNo ratings yet

- BS5930-2015 210Document1 pageBS5930-2015 210Ford cellNo ratings yet

- Geo Technical Data Collection ManualDocument48 pagesGeo Technical Data Collection ManualRaja LaikopanNo ratings yet

- Brady-Brown1985 Chapter RockMassStructureDocument38 pagesBrady-Brown1985 Chapter RockMassStructureJustice MachiwanaNo ratings yet

- Laboratory 4 - Rock Slope StabilityDocument14 pagesLaboratory 4 - Rock Slope StabilitySky FireNo ratings yet

- Tawaeli - Toboli LinkDocument8 pagesTawaeli - Toboli LinkIrianto UnoNo ratings yet

- Clasification of Structural DiscontinuitiesDocument25 pagesClasification of Structural DiscontinuitiesVinny NiniNo ratings yet

- Manual de LogueoDocument137 pagesManual de LogueoEdgar Saenz LizarbeNo ratings yet

- Assessing Prediction Models of Advance Rate in Tunnel Boring Machines - A Case Study in IranDocument9 pagesAssessing Prediction Models of Advance Rate in Tunnel Boring Machines - A Case Study in IranahsanNo ratings yet

- 1111 MergedDocument12 pages1111 MergedMA. ANGELINE GRANADANo ratings yet

- 505105.07a Petrovic Toth Stranjik Determination Rock Parameters For Effective Blasting Using GSI PDFDocument4 pages505105.07a Petrovic Toth Stranjik Determination Rock Parameters For Effective Blasting Using GSI PDFerlangga septa kurniaNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Geotechnical Investigation and Design Tables: Burt G. LookDocument12 pagesHandbook of Geotechnical Investigation and Design Tables: Burt G. LookAlex YNo ratings yet

- Granite Shear StrengthDocument5 pagesGranite Shear Strengthdafo407No ratings yet

- Rock Mass ClassificationDocument59 pagesRock Mass ClassificationUsmanAshrafNo ratings yet

- Excavatability Assessment of Rock Masses Using The Geological Strength Index (GSI)Document15 pagesExcavatability Assessment of Rock Masses Using The Geological Strength Index (GSI)paulocouceiroNo ratings yet

- Core Logging GuideDocument23 pagesCore Logging GuideAliAl-naqaNo ratings yet

- 2006 Hack Discontinuous Rock Mech5Document233 pages2006 Hack Discontinuous Rock Mech5Danyel Hidalgo BrunaNo ratings yet

- Engineering Geology and Rock Engineering: JACK, Christopher D., PARRY, Steve & HART, Jonathan RDocument8 pagesEngineering Geology and Rock Engineering: JACK, Christopher D., PARRY, Steve & HART, Jonathan RSEDIMNo ratings yet

- A GUIDE TO ROCK CORE LOGGING Part 1Document19 pagesA GUIDE TO ROCK CORE LOGGING Part 1CocoNo ratings yet

- Rock Mechanics and Tunneling Course Outline: Part One Rock MechanicsDocument39 pagesRock Mechanics and Tunneling Course Outline: Part One Rock MechanicsMulugeta DefaruNo ratings yet

- Measurement and Analysis of Rock Mass Fractures and Their Applications in Civil EngineeringDocument24 pagesMeasurement and Analysis of Rock Mass Fractures and Their Applications in Civil EngineeringSlobodan Petric100% (1)

- Rock Bolts - Improved Design and Possibilities by Capucine Thomas-Lepine PDFDocument105 pagesRock Bolts - Improved Design and Possibilities by Capucine Thomas-Lepine PDFSaphal LamichhaneNo ratings yet

- Rock Mass Structure and CharacteristicDocument8 pagesRock Mass Structure and CharacteristicRiezxa ViedzNo ratings yet

- Lecture3 NotesDocument18 pagesLecture3 NotestejeswarNo ratings yet

- 8 Influence of Geological Discontinuities Upon Fragmentation by Blasting - 2013Document7 pages8 Influence of Geological Discontinuities Upon Fragmentation by Blasting - 2013ME-MNG-15 RameshNo ratings yet

- PDF Geologic Fracture Mechanics 1St Edition Richard A Schultz Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Geologic Fracture Mechanics 1St Edition Richard A Schultz Ebook Full Chapterrobert.colvin661100% (3)

- Geological Structures - 2020Document34 pagesGeological Structures - 2020ASAMENEWNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Rock MassDocument22 pagesChapter 4 Rock MassadiblazimNo ratings yet