Professional Documents

Culture Documents

David Braund

David Braund

Uploaded by

Taras AkhalaiaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- DISA Parts and Services Catalogue 2019Document141 pagesDISA Parts and Services Catalogue 2019Yanto Daryanto100% (2)

- SITXFSA001 - Student AssessmentDocument31 pagesSITXFSA001 - Student AssessmentNiroj Adhikari100% (3)

- Internship Report On Yummy Ice Cream Factory LahoreDocument64 pagesInternship Report On Yummy Ice Cream Factory LahoreFaizanHaroon50% (4)

- Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies: L'empire Perse: de Cyrus À Alexandre. 1248 PPDocument4 pagesBulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies: L'empire Perse: de Cyrus À Alexandre. 1248 PPSajad AmiriNo ratings yet

- Notices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverDocument2 pagesNotices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Reviews: History and The Homeric IliadDocument7 pagesReviews: History and The Homeric IliadFranchescolly RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Eco1389 3764Document4 pagesEco1389 3764Arlord MarieNo ratings yet

- Guðbrandur Vigfússon. Corpus Poeticum Boreale Vol. IIDocument724 pagesGuðbrandur Vigfússon. Corpus Poeticum Boreale Vol. IISveinaldr100% (1)

- Eco866 6663Document4 pagesEco866 6663Ilham BintangNo ratings yet

- Chem1047 1892Document4 pagesChem1047 1892Juan Alcazar RomeroNo ratings yet

- Levada 2012 Scandinavian-Crimean Contact PDFDocument5 pagesLevada 2012 Scandinavian-Crimean Contact PDFEarthtopusNo ratings yet

- Acc8685 3837Document4 pagesAcc8685 3837Fernandez, Rica Maye G.No ratings yet

- Eng7667 9496Document4 pagesEng7667 9496Quinn JacksonNo ratings yet

- Eng3562 6516Document4 pagesEng3562 6516ar gNo ratings yet

- Roman Penetration Into The Southern Red PDFDocument47 pagesRoman Penetration Into The Southern Red PDFAnonymous KxceunzKsNo ratings yet

- Lmaoxdxd9590 6876Document4 pagesLmaoxdxd9590 6876SeanBlahNo ratings yet

- Zeus - A Study in Ancient Religion - Vol III Part II - Cook PDFDocument360 pagesZeus - A Study in Ancient Religion - Vol III Part II - Cook PDFTornike Koroglishvili100% (2)

- Ancient Egyptian Ships and ShippingDocument36 pagesAncient Egyptian Ships and Shippingjaym43No ratings yet

- Cal8217 3826Document4 pagesCal8217 3826Michael JordanNo ratings yet

- From the Caves and Jungles of Hindostan: Letters to the HomelandFrom EverandFrom the Caves and Jungles of Hindostan: Letters to the HomelandNo ratings yet

- Bio1393 9345Document4 pagesBio1393 9345JA YZ ELNo ratings yet

- mkt2974 3801Document4 pagesmkt2974 3801syahidah adilahNo ratings yet

- Hiller - Mycenaeans in Black SeaDocument15 pagesHiller - Mycenaeans in Black SeaFrancesco BiancuNo ratings yet

- A Contribution To Dānishmendid History: The Figured Copper Coins / Estelle J. WhelanDocument37 pagesA Contribution To Dānishmendid History: The Figured Copper Coins / Estelle J. WhelanDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- The Southern Border of Caucasian AlbaniaDocument19 pagesThe Southern Border of Caucasian Albaniamv5805h3No ratings yet

- A Journey Round The Coast of The Black Sea in The Ninth CenturyDocument10 pagesA Journey Round The Coast of The Black Sea in The Ninth CenturyseckinevcimNo ratings yet

- Chem1200 3882Document3 pagesChem1200 3882Chris AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Acc8009 1684Document4 pagesAcc8009 1684German QuiterioNo ratings yet

- Eng877 2848Document4 pagesEng877 2848Tasya axNo ratings yet

- Alans in The 6th C.Document8 pagesAlans in The 6th C.pananosNo ratings yet

- From the Caves and Jungles of the HindostanFrom EverandFrom the Caves and Jungles of the HindostanRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- From The Caves And Jungles Of The HindostanFrom EverandFrom The Caves And Jungles Of The HindostanRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Econ1851 4523Document4 pagesEcon1851 4523Yosepine ZebuaNo ratings yet

- Psy9068 2600Document4 pagesPsy9068 2600Asentio Hedli TamaNo ratings yet

- North OdisseasDocument18 pagesNorth OdisseasparanormapNo ratings yet

- Acc6631 5551Document4 pagesAcc6631 5551Nathaniel “Nat” EsguerraNo ratings yet

- Los Siete DurmientesDocument1 pageLos Siete DurmientespabloNo ratings yet

- Scythia The Interpretation of The Data oDocument13 pagesScythia The Interpretation of The Data oDai ChaoticNo ratings yet

- Eco2874 597Document4 pagesEco2874 597Xonax PratiNo ratings yet

- Eng1056 7953Document4 pagesEng1056 7953Samantha GalizaNo ratings yet

- Maus de Rolley - Main DocumentDocument27 pagesMaus de Rolley - Main DocumentErick VarelaNo ratings yet

- Teatro Grecia y Roma. Asientos - BEARE, W. (1939)Document6 pagesTeatro Grecia y Roma. Asientos - BEARE, W. (1939)glorydaysNo ratings yet

- Math7881 7123Document4 pagesMath7881 7123Shilla Mae BalanceNo ratings yet

- Acc3937 2618Document4 pagesAcc3937 2618afiq1229No ratings yet

- Psy2780 5177Document4 pagesPsy2780 5177Mae Danica CalunsagNo ratings yet

- 8683Document4 pages8683Vidzdong NavarroNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledflorever maniaNo ratings yet

- Hist8671 7559Document4 pagesHist8671 7559muhammad zulfikarNo ratings yet

- The Mesha Stone - A Reappraisal of A ForgeryDocument6 pagesThe Mesha Stone - A Reappraisal of A ForgeryDavide VenturaNo ratings yet

- Blackman, An Indirect Reference To Sesostris III Syrian CampaignDocument4 pagesBlackman, An Indirect Reference To Sesostris III Syrian Campaignwetrain123No ratings yet

- Math7881 7145Document4 pagesMath7881 7145Shilla Mae BalanceNo ratings yet

- Phys271 3507Document4 pagesPhys271 3507Yakobus Benyamin Renno ArwalembunNo ratings yet

- !generate5918 3329Document4 pages!generate5918 3329Alex ChávezNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egyptian Donation Stela in The Archaeological Museum of Florence (Inv. 7207)Document7 pagesAncient Egyptian Donation Stela in The Archaeological Museum of Florence (Inv. 7207)ALaa AhmedNo ratings yet

- Econ714 302Document4 pagesEcon714 302Davian GreyNo ratings yet

- Chem 8607Document4 pagesChem 8607Dinesh Venkata GoggiNo ratings yet

- Archaeologica: Vol. X FascDocument30 pagesArchaeologica: Vol. X Fascmark_schwartz_41100% (2)

- The Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionDocument8 pagesThe Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionAankh BenuNo ratings yet

- Black Ships and Sea Raiders History Arch PDFDocument16 pagesBlack Ships and Sea Raiders History Arch PDFNasai Littarru Sampedro100% (1)

- MNGT 6933Document4 pagesMNGT 6933NicoNo ratings yet

- Hist7013 1403Document4 pagesHist7013 1403Deniel DenamarcaNo ratings yet

- Math2341 7836Document4 pagesMath2341 7836IvanwbsnNo ratings yet

- Economic Efficiency of Smallholder Farmers in Tomato Production Inbakotibe District Oromia Region Ethiopia PDFDocument8 pagesEconomic Efficiency of Smallholder Farmers in Tomato Production Inbakotibe District Oromia Region Ethiopia PDFsolomon dejejenNo ratings yet

- 20102023-UnlockedDocument7 pages20102023-UnlockedMittun 3009No ratings yet

- D PK 0707398 BibliographyDocument7 pagesD PK 0707398 Bibliographyarwani majidNo ratings yet

- From Novice To Expert Theory - Lucille Alkhaldi BSN RNDocument11 pagesFrom Novice To Expert Theory - Lucille Alkhaldi BSN RNmaha_alkhaldi100% (1)

- Type 9, 12, 16, 20, 24 & 36 Brake Chamber (SD-02-1302)Document4 pagesType 9, 12, 16, 20, 24 & 36 Brake Chamber (SD-02-1302)Angel Dlsg100% (1)

- Answer:: Multiple ChoiceDocument17 pagesAnswer:: Multiple ChoiceQuenie Jeanne De BaereNo ratings yet

- The Nibbāna Sermons 1 To 11 by Bhikkhu K Ñā AnandaDocument24 pagesThe Nibbāna Sermons 1 To 11 by Bhikkhu K Ñā AnandaCNo ratings yet

- 8 Features of The Caste SystemDocument2 pages8 Features of The Caste SystemSaurabh TiwariNo ratings yet

- Hitler and GermanentumDocument17 pagesHitler and Germanentumlord azraelNo ratings yet

- Standard Practice (SP)Document9 pagesStandard Practice (SP)nizam1372No ratings yet

- EasyFile MANUALDocument29 pagesEasyFile MANUALRonald Luckson ChikwavaNo ratings yet

- GU Balance Routine Testing enDocument12 pagesGU Balance Routine Testing enasalazarsNo ratings yet

- Training Project ReportDocument62 pagesTraining Project ReportGaurav Singh Bhadoriya0% (1)

- Hastage Magazine's Latest DECEMBER Issue!Document66 pagesHastage Magazine's Latest DECEMBER Issue!HastagmagazineNo ratings yet

- G10-2nd-Q-review Sheets-Chem-Chap7, 8.1, 8.2Document8 pagesG10-2nd-Q-review Sheets-Chem-Chap7, 8.1, 8.2Karim Ahmed100% (1)

- Investors Sentiment in India SurveyDocument12 pagesInvestors Sentiment in India SurveyZainab FathimaNo ratings yet

- Delta Marketing TrendsDocument7 pagesDelta Marketing TrendsCandy SaberNo ratings yet

- 0606 Additional Mathematics: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2014 SeriesDocument6 pages0606 Additional Mathematics: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2014 SeriesKennedy Absalom ModiseNo ratings yet

- JutlandicDocument24 pagesJutlandicmorenojuanky3671No ratings yet

- Poverty 2Document9 pagesPoverty 2Camid AlanissahNo ratings yet

- Canteen Block - Report DailuxDocument106 pagesCanteen Block - Report Dailuxkailash kumar soniNo ratings yet

- Fourth Quarter-Grade-7-MathematicsDocument4 pagesFourth Quarter-Grade-7-MathematicsJosefina TabatNo ratings yet

- Ana&Physio 16 - Human DevelopmentDocument37 pagesAna&Physio 16 - Human DevelopmentShery Han Bint HindawiNo ratings yet

- Bella Luna (Jason Mraz With Chords)Document5 pagesBella Luna (Jason Mraz With Chords)Mario CorroNo ratings yet

- Grammaire - L1 G1+3+4+7 - M. Benkider - Corrigé Et CommentairesDocument3 pagesGrammaire - L1 G1+3+4+7 - M. Benkider - Corrigé Et CommentairesYssoufFahSNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Composition and Backtesting: Dakota WixomDocument34 pagesPortfolio Composition and Backtesting: Dakota WixomGedela BharadwajNo ratings yet

- Sewers For Adoption: - A Design and Construction Guide For Developers - Small Developments Version - September 2013Document48 pagesSewers For Adoption: - A Design and Construction Guide For Developers - Small Developments Version - September 2013humayriNo ratings yet

David Braund

David Braund

Uploaded by

Taras AkhalaiaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

David Braund

David Braund

Uploaded by

Taras AkhalaiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Collection « ISTA »

Anagranes the ΤΡΟΦΕΥΣ : the court of caucasian Iberia in the

second-third centuries AD

David Braund

Citer ce document / Cite this document :

Braund David. Anagranes the ΤΡΟΦΕΥΣ : the court of caucasian Iberia in the second-third centuries AD . In: Autour de la mer

Noire. Hommage de Otar Lordkipanidzé. Besançon : Institut des Sciences et Techniques de l'Antiquité, 2002. pp. 23-34.

(Collection « ISTA », 862);

https://www.persee.fr/doc/ista_0000-0000_2002_ant_862_1_1953

Fichier pdf généré le 06/05/2018

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé, 23-34

ANAGRANES THE ΤΡΟΦΕΥΣ : THE COURT OF CAUCASIAN IBERIA

IN THE SECOND-THIRD CENTURIES AD

Two new inscriptions from Georgia shed fresh light on the royal court of

Caucasian Iberia in the Roman period. They offer important new information

particularly about the titulature of the court and about relations between Iberia

and Armenia, including personages hitherto unknown. One such is Anagranes,

who bears the title τροφευς. It seems fitting to offer a study of such a man to

Otar Lordkipanidze, who over the years has provided intellectual τροφή for

so many foreigners engaged with Georgian antiquity, including myself.

The new inscriptions, both in Greek and both on stone plaques, hâve

been unearthed in the course of renewed excavation at Bagineti on the lower

slope of the fortified hill-cum-acropolis usually (and no doubt rightly) identi-

fied with the principal strongpoint of the sprawling city of Mtskheta, namely

the Harmozike of the literary tradition. They were found in association with

a bath-building, itself in close proximity to structures long since identified as

a palace of the Iberian kings, looking northwards across the River Cyrus (mod.

Mtkvari) to the hill of Jvari and the mouth of the River Aragus (mod. Aragvi).

The inscriptions hâve been published with admirable speed by Prof.

Tinatin Qaukhchishvili1. Since her publications are not readily accessible and

since some additional points may be contributed, I shall first consider the texts

in some détail.

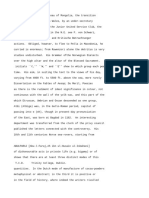

1. The better-preserved stone (henceforth, no.l) may be read without

difficulty :

.../ 'Αρμενίας Ούολο / γαίσου, γυναικΐ δε / βασιλέως Ιβήρων /

μεγάλου Άμαζάσ / που Άναγράνης ό / τροφευς και έπιτρ / <ο>πος ίδια

δυνάμ<ε>ι / το βαλανΐόν άφιε'ρω / σεν

* David Braund.

1. Qaukhchishvili 1996, 1998 and 1999. I am most grateful to Guram Qipiani, deputy director of

the Bagineti expédition, for providing me with photographs.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

24 David Braund

ττουανλπρ

1. Inscription n° 1.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

Anagranes the τροφευς: the court ofCaucasian Iberia... 25

2. Inscription n° 2.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

26 David Braund

Evidently the beginning of the inscription was eut on a separate stone,

for the extant stone is undamaged. Despite the initial lacuna, however, there is

no difficulty in translating the text as we hâve it :

To...(?daughter) ... of (...?king) Vologaeses (?...) of Armenia, and wife of

Amazaspus, king oflberians, great, Anagranes the foster-father (τροφεΰς) and steward

(επίτροπος) with his own resources dedicated the bath-building.

The bath-building in question must be that currently under excavation,

substantial in size. Although there are enfiladed baths of this period in Iberia

(at Dzalisi and elsewhere in Mtskheta itself), this bath-building seems to hâve

followed the more random plan typical of the Greek βαλανεΤον (or as our text

prefers, βαλανΤον)2.

2. The second stone (henceforth, no.2) has survived less well, having lost

its upper right-hand side. Nevertheless, there is enough to indicate that its

contents were substantially similar to those of no.l, as we shall see. Hère again

the beginning of the inscription was eut on a separate stone and has been lost.

Yet once more the loss can be overcome. The inscription is to be read as

f ollows :

...[βασι] / λέως [Άναγ]ράνης [τρο]φεί)[ς και επί] / τροπο[ς ίδια

δυ]νάμ[<ε>ι ? το βαλ]ανΐον αρτισας / ίδια τροφίμη / Δρακόντιδι βασ /

ιλισ(σ)η άφιερωσεν.

... of... king, Anagranes foster-father and steward with his own resources

having fitted ont (?) the bath-building (?) for his own nurtured Drakontis, queen,

dedicated (it).

Some explanations and cautionary observations are required. The resto-

ration [ Άναγ]ράνης may be made with some confidence, for we evidently hâve

the titles found in no.l : the letters which begin line 3 of no.2 can only be the

end of τροφεύς, while line 4 is therefore presumably the end of επίτροπος.

The coïncidence of titulature and the survival of the last five letters of the name

(line 2, where a rho may be read) establishes the présence of Anagranes, omitted

by Qaukhchishvili, and once more as dedicator. However, lines 5-6 are more

troubling. Qaukhchishvili may be right to read [βαλ]αν(ε)Τον κτΐσα[ς] , 'having

built the bath-building', though the final sigma is clear on the stone and requires

2. The bath-building will be published in due course. On the random βαλανεΤον, see Nielsen 1993, 9,

with Braund 1994 on baths in Iberia.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

Anagranes the τροφεύς : the court of Caucasian Iberia ... 27

no restoration3. Yet, although both Qaukhchishvili and I hâve proposed a

βαλανΤον, one could wish for greater certainty on the matter. The aorist parti-

ciple evidently dénotes construction or adornment, though its précise

identification too remains elusive. Be that as it may, we may be sure enough of [ιδία

δυ]νάμ[ει in Unes 4-5, given the use of the expression in no.l (line 7) ; there is no

need, pace Qaukhchishvili, to propose the odd νδμα (a poetic word for running

water), which would leave an awkward space at the end of line 4 in any case.

Problematic as thèse matters may be, however, they do not affect the

présent discussion in any significant fashion. The key observation must be

(pace Qaukhchishvili) that both inscriptions name Anagranes as dedicator,

apparently of the bath-building, but possibly of the bath-building as a whole

(no.l) and of some part or feature thereof (no.2).

II

We may now turn to personages and titulature. In no.l the dedicatee is

a female, indeed a royal female. In no.2, where one could wish for the lost

opening Unes, the dedicatee seems also to be a royal female. Given that in both

cases the dedicator is Anagranes there is a strong prima facte case for identifying

the two royal ladies. I suggest that we must consider the possibility that

Drakontis of no.2 is the daughter (as it seems) of Vologaeses of Armenia and

wife of Amazaspus found in no.l. One may wonder why the dedication should

be inscribed twice in that case, but so much is not implausible in so large a

structure and (it is to be stressed once more) we cannot be sure that no.2 refers

to the whole bath-building and not some part or feature thereof, in which case

the two dedications would be distinct.

In both inscriptions Anagranes boasts the title(s) τροφευς και επίτροπος,

"foster-father and steward". The latter term may well indicate financial

responsibility, but it is a title of broad applicability. Indeed it has long been

known in the Iberian royal court for it occurs on the epitaph of Serapeitis, where

it seems to encompass also a military rôle4.

By contrast, this is the first τροφεύς known at the Iberian court. The title

and position are more familiar elsewhere and rather earlier, in the courts of the

3. Pace Qaukhchishvili 1999, 31.

4. On this inscription, see Braund 1994, 213.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

28 David Braund

Seleucids and Ptolemies, where they hâve prompted a good deal of scholarly

discussion. Naturally, we cannot assume blithely that the τροφεΰς Anagranes

was entirely the same in status or function as his earlier Seleucid and Ptolemaic

counterparts. However, it seems worthwhile to consider those counterparts

and possible similarities, especially in view of the (rather neglected) fact that

hellenistic Iberia (as also Armenia) had fallen within the impérial sphère of the

Seleucids. It is entirely likely that Iberian and Armenian court structures owed

something to Seleucid institutions. There is even some reason to suspect that

the Iberian kings were proud of the Seleucid link, which may be hinted at in the

epitaph of an Iberian prince early in the second century AD5.

Our fullest information on the workings of the relationship between the

τροφεΰς and his ward is Polybius' narrative of the résidence in Rome of the

future Demetrius I Soter of Syria in the second century BC. Demetrius had been

sent to Rome from Syria as a boy of some ten years of âge. It has often been

thought that he had been accompanied to Rome by his τροφεΰς, one Diodorus,

whom Polybius describes acting as a key agent of Demetrius after he had

reached adulthood, coming to report to the prince in Rome upon the situation

in Syria. According to Polybius, who was himself very closely involved in thèse

events, it was the arguments of Diodorus the τροφεύς which convinced

Demetrius to escape from Rome and to seize for himself the kingdom of Syria.

And it was Diodorus whom Demetrius sent on ahead (Polyb. 31.12). Polybius'

account nicely illustrâtes the fact that the τροφεύς could retain a spécial

relationship with his ward well after the ward had reached an âge at which

he or she was capable of independent action. A range of inscriptions tends to

confirm the point and to underline the prominent position that a τροφεΰς could

continue to hold, especially no doubt as one particularly trusted by his former

charge. For example, an honorific inscription from Athens orders the érection of

a bronze statue to a τροφεΰς named as [Me]nodorus (or [Ze]nodorus or the like)

in the agora, beside the statue of his former charge, Antiochus (IV ?)6. Similar is

another Seleucid instance from Delos, where Craterus the τροφεύς was

honoured with a statue on the same base as the statue of his former charge

Antiochus IX, in the period 130-117 BC7.

5. IGRR 1. 192, with Braund 1994, 230-1.

6. Meritt 1967, 59-63, no.6, improved by Robert 1969, 6.

7. Durrbach 1921, no. 109-110 ; OGIS 255-6.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

Anagranes the τροφεύς : the court ofCaucasian Iberia.. . 29

Thèse cases concern rulers who were brought up outside their

paternal realms, whether in Rome (Demetrius, following Antiochus IV) or

elsewhere (Antiochus IX was brought up at Cyzicus). Yet, as the classic

discussion of Corradi insists, while the rôle of the τροφεύς doubtless took

on particular importance in cases where the future ruler was brought up

abroad, we should not imagine that the τροφεύς was only important in such

circumstances8.

Be that as it may, the key point for the présent discussion must be

the continued prominence of the τροφεύς even after his ward had become

a ruler. This is attested elsewhere for royal females : the eunuch τροφεύς

of the Tarcondimotid princess Julia boasted both his own title and the

royal title of his former charge in his epitaph around the end of the first

century BC (βασιλίδος 'Ιουλίας νεωτέρας τροφεύς)9. It is well attested

also at the court of the Ptolemies, both in Egypt and in other of their

possessions : note especially from Ptolemaic Cyprus c. 100 BC the case

of Helenus τροφεύς του βασιλέως10. The potential power of the τροφεύς is

not to be underestimated : as Bikerman observed long ago, the Seleucid

king might well leave power at home in the hands of his τροφεύς when he went

off on campaign11.

There is nothing remarkable in the survival of this important institution

into the Roman period : a third century AD case happens to be known for the

king of Tanukh, also influenced no doubt by Seleucid predecessors12. Indeed,

even in non-royal circles the τροφεύς continued to be significant and to retain a

spécial link with his ward into adulthood : around AD 100, for example, at

Salamis on Cyprus the τροφεύς Boethus set up a statue for a member of the

local élite, evidently his former charge13. The concept of τροφεία had long since

entered the discourse too of civic benefaction14.

8. Corradi 1929, 277-81.

9. On the dynasty, see Sullivan 1990, 405.

10. Bernand 1975, 24-9, no.5 (c. 130 BC), with Mooren 1975, 86-7 ; Mitford and Nicolaou 1974, 18-19

no. 6, with Mitford 1959, on Helenus ; cf. Mooren 1975, 208 ; Robert 1963, 74-5.

11. Bikerman 1938, 21.

12. Bellinger and Welles 1935, 126 n.21.

13. Mitford and Nicolaou 1974, 148-9, no.lll.

14. Robert 1960 ; 1967, 66-7 ; Engelmann and Merkelbach 1972, 161.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

30 David Braund

Thèse brief remarks are suggestive for our Iberian case. Anagranes

présents himself as τροφεΰς of royal Drakontis in no.2, in particular15. As we

hâve seen, it was quite usual for the τροφεΰς to retain not only his title but also

much of his significance into the adult life of his former charge. More

challenging is the question of the circumstances in which Anagranes had been

her τροφεΰς at ail. Had he played the rôle in her father's kingdom or abroad ?

Or both ? If Drakontis was indeed the royal female of no.l, as I tend to believe,

and if, as is the likeliest hypothesis16, she is named there as daughter of

Vologaeses, then her father's realm was (or at least included) Armenia. Should

we then consider Anagranes to be an Armenian who accompanied his former

charge to the court of her husband in Iberia, enjoying some prominence there ?

Possibly so, but we are at (indeed, beyond) the limits of our évidence,

particularly as we cannot be completely sure that Drakontis is indeed the royal

female of no.l. And, in any case, we cannot assume that a king would always

appoint a τροφεύς from within his kingdom : an outsider might well be

préférable. Indeed, Anagranes might even be an Iberian !

The identification of Vologaeses and Amazaspus would no doubt

improve our understanding of thèse relationships. Of course, in very gênerai

terms, it is well known that the rulers of Iberia and Armenia often enjoyed close

relations, not only in antiquity, but also in later periods17. The fact that thèse

relations could also become hostile scarcely affects the matter18. However, we

need to identify thèse particular rulers, if we are to make further historical use

of thèse new inscriptions.

As Qaukhchishvili rightly notes19, the name Amazaspus is attested for

several différent personages among the rulers of Iberia, both in the classical

évidence and in the Georgian mediaeval tradition. The évidence for a ruler of

Armenia with the name Vologaeses (Valarsh in the Armenian tradition) is

hardly more restricted. It seems now to be orthodox to date the reign of Valarsh

I as AD 116-144 and Valarsh II as AD 186-198. Qaukhchishvili may well be right

15. It is perhaps worth noting in that context the ambivalence of the adjective τρόφιμος, which can

encompass not only Anagranes' nurturing of Drakontis but also in adulthood her nurturing of him,

for the adjective can be both active and passive in force, as LSJ observes.

16. So too Qaukhchishvili 1998, 12.

17. Qaukhchishvili 1998, 13.

18. For example, see Braund 1994, 224 on the évidence of Tacitus' Annals.

19. Qaukhchishvili 1998, 13.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

Anagranes the τροφεύς : the court ofCaucasian Iberia.. . 31

in opting for the latter, which would place the inscriptions and the baths in the

late second or early third centuries AD. The letter forms of the two inscriptions

(evidently eut by différent masons) cannot be pressed to provide a date,

especially in view of the scanty epigraphical record from the area20, but they

seem to be consonant with a date c. AD 200. On broad historical grounds too,

it is easy enough to imagine development and prosperity in Iberia around this

date, when, for example, the diplomatie silverware of Marcus Aurelius found

its way into a burial at Mtskheta, indeed at Bagineti itself, hard by our bath-

building21. However, for ail that, we need also to find an appropriate

Amazaspus ; indeed a prominent one, if his grandiloquent title is to be given

any substance. Perhaps, as Qaukhchishvili seems to believe, he is to be

identified as the Amazaspus mentioned in the so-called Res Gestae of Shapur I

in the middle of the third century, around AD 26222.

The essential difficulty, which is worth recognizing explicitly, is that we

simply do not hâve information on the rulers of Iberia or Armenia in thèse years

of a type sufficient to provide strong chronology, notwithstanding the efforts

of many fine scholars. While there are a very few firm landmarks in thèse

dynasties, the great mass is a matter of hypothesis and spéculation.

If we accept Qaukhchishvili's reasonable hypothesis on the identity

of Amazaspus, we need a Vologaeses who could be described as king of

Armenia. There is a wide range of possibilities, in part discussed by

Qaukhchishvili, but we should consider also those kings for whom we hâve

no name : it is likely enough that one or two of them were also called

Vologaeses. It is perhaps worth considering in particular the king of Armenia

who was removed by Caracalla around AD 214. The emperor had tricked

him into visiting Rome in the expectation that a dispute between the king

and his children might be settled. Instead Caracalla detained him. It would not

be surprising if at least some of his family accompanied the king to Rome,

for there was a dispute within the family to be settled and subsequently there

is no mention of the king's children playing a rôle in the Armenian

uprising against Caracalla which ensued. We happen to be told that an (the ?)

20. Compare the wide variation in modem dating of the Greek inscription from Aparan in

Armenia : Chaumont 1976, esp. 185-8.

21. Braund 1994, 235-7, with illustration.

22. Braund 1994, 239-41, with the literature there cited.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

32 David Braund

Armenian queen was among those detained, as well as the king23. Was this

the immédiate family of Drakontis ? Are we to identify her father Vologaeses as

the king dethroned and detained by Caracalla24 ? We cannot know, but the

possibility abides.

If Vologaeses was in place in Armenia until removed by Caracalla around

AD 214, his daughter might well hâve married (whether before or after

her father's removal) the man mentioned in Shapur's court around AD 262.

Moreover, the prominence of Amazaspus at Shapur's court would accord well

with the title "Great", accorded to him in no.l. Accordingly, on thèse arguments,

we might wish to date the inscriptions and the construction of the bath-building

at Bagineti rather later than Qaukhchishvili's c. AD 200, perhaps by several

décades. We need not suppose that Vologaeses was still alive at the time that

the inscriptions were eut. It is to be hoped that the completion and publication

of the more récent excavations at Bagineti will give a stronger idea of the date

at which the bath-building was built.

And what of the relationship between our principal personages ?

Was Drakontis held in Rome with her father and the rest of her family ?

Was Anagranes there too, acting as τροφεύς ? Ail dépends on the date of her

marriage to Amazaspus and the attendant circumstances, about which we can

only wonder. If she was not yet married at the time of her father's (on this

argument) déposition, she will either hâve journeyed with him to Rome and

been kept there for some time, or she will hâve been left in Armenia, unless the

dispute in the family mentioned by Dio was sufficient to send her elsewhere,

even to Iberia. Whatever the case Anagranes will hâve been with her. The

political significance of her marriage is similarly unclear. We might imagine

that her marriage to a king so well-connected with Shapur is to be linked with

anti-Roman tendencies in her family, especially perhaps if the marriage took

place after her father's removal.

With the king dethroned, Anagranes the τροφεύς was no doubt ail

the more significant. That may give a particular meaning to his other title,

επίτροπος. Once again earlier hellenistic practice may be instructive, for we find

single individuals holding both positions in that context too, whether in

23. Dio 78.27.4, with Chaumont 1976, 155-7, esp. 156 n.481.

24. If so, then this was presumably not the king mentioned under Severus : see Chaumont 1976, 155.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

Anagranes the τροφεύς : the court of Caucasian Iberia ... 33

the perhaps-imprecise terminology of the literary tradition25 or in the probably

more considered language of the inscriptions26.

There is every reason to suppose that Anagranes was a man of the first

importance in the kingdom of Amazaspus, however we imagine his ethnicity.

His close bond with Amazaspus' queen aside, the very scale and prime location

of the baths he dedicated provide clear évidence of that. It was usual enough in

antiquity for such baths to be known by the names of those who built them :

perhaps thèse baths were known as "the baths of Anagranes"27. Yet there was a

price to be paid : those who built such baths might be expected to pay not only

for their construction but also for their maintenance and running costs, for

example by providing oil for bathers (presumably a costly commodity in Iberia,

whish is rich in vines but not in olive trees)28. Or was the bath-building known

rather as "the baths of Drakontis", conceivably a bath-building especially

for females, as are attested elsewhere29 ? Answers are elusive, but the questions

are worthy of considération. For, as Otar Lordkipanidze has always shown,

scholarship proceeds best by a judicious mixture of hard-headed research and

controlled use of the well-informed imagination.

Bibliography

Bellinger, A.R., and Welles, C.B. 1935, "A third century contract of sale from Edessa", Yale Classical

Studies 5. 95-156.

Bernand, E. 1975, Recueil des inscriptions grecques du Fayoum I (Leiden).

Bikerman, E. 1938, Institutions des Séleucides (Paris).

Braund, D. 1994, Georgia in antiquity : a history ofColchis and Transcaucasian Iberia, c.550 BC-AD 562

(Oxford).

Chaumont, M.-L. 1976, "L'Arménie entre Rome et l'Iran (I)", in W. Haase and H. Temporini (eds.),

Aufstieg und Niedergang der roem.isch.en Welt II.9.1 (Berlin), 71-194.

Corradi, G. 1929, Studi ellenistici (Turin).

Crampa, J. 1972, Labraunda III.2 (Stockholm).

25. Polyb. 28. 21 with Diod. Sic 30.15 on Eulaeus at the Ptolemaic court ; see Walbank 1979, 355-6

and the literature he cites.

26. OGIS 141 with Mooren 1975, 207.

27. Nielsen 1993, 120 n.ll.

28. Crampa 1972, 134.

29. Ginouvès 1962, 220-4 ; Nielsen 1993, 7, esp. n.l7.This article owes much to the help of Joyce

Reynolds ; faults are my own.

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidze

34 David Braund

Durrbach, F. 1921, Choix d'inscriptions de Délos (Paris).

Engelmann, H., and Merkelbach, R. 1972, Die Inschriften von Erythrai und Klazomenai I (Bonn).

Ginouvès, R. 1962, Balaneutike : recherches sur le bain dans l'antiquité grecque (Paris).

Meritt, B.D. 1967, "Greek inscriptions", Hesperia 36. 57-101.

Mitford, T.B. 1959, "Helenos governor of Cyprus", Journal ofHellenic Studies 79. 94-131.

Mitford, T.B., and Nicolaou, I. K. 1974, The Greek and Latin inscriptions front Salamis (Nicosia).

Mooren, L. 1975, The aulic titulature in Ptolemaic Egypt (Brussels).

Nielsen, 1. 1993, Thermae et balnea (Aarhus, 2nd. edn.).

Qaukhchishvili, T. 1996, "Akhali berdznuli tsartserebi armazistsikhe-baginetidan (New Greek

inscriptions from Armazistsikhe-Bagineti)", Mtskheta 11. 81-92.

Qaukhchishvili, T. 1998, "Akhali berdznuli tsartsera armazistsikhe-baginetidan (II) (A new Greek

inscription from Armazistsikhe-Bagineti)", Narkvevebi (khelovnebis sakhelmtsipo muzeumis) (Essays

ofthe State Muséum of Art) 1998. 11-14.

Qaukhchishvili, T. 1999, "Dzveli berdznuli tsartserebis shesakheb sakartveloshi (On ancient Greek

inscriptions in Georgia)", in Kalakebi da saMako tskhovreba dzvel sakartveloshi I (Cities and city life

in ancient Georgia : abstracts of a conférence in honour of A. Apakidze) (Tbilisi), 27-32.

Robert, L. 1960, "τροφεύς et άριστευς", Hellenica 11-12. 569-76.

Robert, L. 1963, Review of P.M. Fraser, Samothrace 11.1, Gnomon 35. 50-79.

Robert, L. 1967, Monnaies grecques (Geneva-Paris).

Robert, L. 1969, "Inscriptions d'Athènes et de la Grèce Centrale. I. Décret d'Athènes pour un

courtisan Séleucide", Αρχαιολογική Εφημερις 1-58, esp. 1-6.

Sullivan, R.D. 1990, Near eastern royalty and Rome, 100-30 BC (Toronto)

Walbank, F.W. 1979, A Historical Commentary on Polybius III (Oxford).

Autour de la mer Noire. Hommage à Otar Lordkipanidzé

You might also like

- DISA Parts and Services Catalogue 2019Document141 pagesDISA Parts and Services Catalogue 2019Yanto Daryanto100% (2)

- SITXFSA001 - Student AssessmentDocument31 pagesSITXFSA001 - Student AssessmentNiroj Adhikari100% (3)

- Internship Report On Yummy Ice Cream Factory LahoreDocument64 pagesInternship Report On Yummy Ice Cream Factory LahoreFaizanHaroon50% (4)

- Bulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies: L'empire Perse: de Cyrus À Alexandre. 1248 PPDocument4 pagesBulletin of The School of Oriental and African Studies: L'empire Perse: de Cyrus À Alexandre. 1248 PPSajad AmiriNo ratings yet

- Notices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverDocument2 pagesNotices of Books: of The Macedonian Army. Berkeley Etc.: UniverRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Reviews: History and The Homeric IliadDocument7 pagesReviews: History and The Homeric IliadFranchescolly RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Eco1389 3764Document4 pagesEco1389 3764Arlord MarieNo ratings yet

- Guðbrandur Vigfússon. Corpus Poeticum Boreale Vol. IIDocument724 pagesGuðbrandur Vigfússon. Corpus Poeticum Boreale Vol. IISveinaldr100% (1)

- Eco866 6663Document4 pagesEco866 6663Ilham BintangNo ratings yet

- Chem1047 1892Document4 pagesChem1047 1892Juan Alcazar RomeroNo ratings yet

- Levada 2012 Scandinavian-Crimean Contact PDFDocument5 pagesLevada 2012 Scandinavian-Crimean Contact PDFEarthtopusNo ratings yet

- Acc8685 3837Document4 pagesAcc8685 3837Fernandez, Rica Maye G.No ratings yet

- Eng7667 9496Document4 pagesEng7667 9496Quinn JacksonNo ratings yet

- Eng3562 6516Document4 pagesEng3562 6516ar gNo ratings yet

- Roman Penetration Into The Southern Red PDFDocument47 pagesRoman Penetration Into The Southern Red PDFAnonymous KxceunzKsNo ratings yet

- Lmaoxdxd9590 6876Document4 pagesLmaoxdxd9590 6876SeanBlahNo ratings yet

- Zeus - A Study in Ancient Religion - Vol III Part II - Cook PDFDocument360 pagesZeus - A Study in Ancient Religion - Vol III Part II - Cook PDFTornike Koroglishvili100% (2)

- Ancient Egyptian Ships and ShippingDocument36 pagesAncient Egyptian Ships and Shippingjaym43No ratings yet

- Cal8217 3826Document4 pagesCal8217 3826Michael JordanNo ratings yet

- From the Caves and Jungles of Hindostan: Letters to the HomelandFrom EverandFrom the Caves and Jungles of Hindostan: Letters to the HomelandNo ratings yet

- Bio1393 9345Document4 pagesBio1393 9345JA YZ ELNo ratings yet

- mkt2974 3801Document4 pagesmkt2974 3801syahidah adilahNo ratings yet

- Hiller - Mycenaeans in Black SeaDocument15 pagesHiller - Mycenaeans in Black SeaFrancesco BiancuNo ratings yet

- A Contribution To Dānishmendid History: The Figured Copper Coins / Estelle J. WhelanDocument37 pagesA Contribution To Dānishmendid History: The Figured Copper Coins / Estelle J. WhelanDigital Library Numis (DLN)100% (1)

- The Southern Border of Caucasian AlbaniaDocument19 pagesThe Southern Border of Caucasian Albaniamv5805h3No ratings yet

- A Journey Round The Coast of The Black Sea in The Ninth CenturyDocument10 pagesA Journey Round The Coast of The Black Sea in The Ninth CenturyseckinevcimNo ratings yet

- Chem1200 3882Document3 pagesChem1200 3882Chris AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Acc8009 1684Document4 pagesAcc8009 1684German QuiterioNo ratings yet

- Eng877 2848Document4 pagesEng877 2848Tasya axNo ratings yet

- Alans in The 6th C.Document8 pagesAlans in The 6th C.pananosNo ratings yet

- From the Caves and Jungles of the HindostanFrom EverandFrom the Caves and Jungles of the HindostanRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- From The Caves And Jungles Of The HindostanFrom EverandFrom The Caves And Jungles Of The HindostanRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Econ1851 4523Document4 pagesEcon1851 4523Yosepine ZebuaNo ratings yet

- Psy9068 2600Document4 pagesPsy9068 2600Asentio Hedli TamaNo ratings yet

- North OdisseasDocument18 pagesNorth OdisseasparanormapNo ratings yet

- Acc6631 5551Document4 pagesAcc6631 5551Nathaniel “Nat” EsguerraNo ratings yet

- Los Siete DurmientesDocument1 pageLos Siete DurmientespabloNo ratings yet

- Scythia The Interpretation of The Data oDocument13 pagesScythia The Interpretation of The Data oDai ChaoticNo ratings yet

- Eco2874 597Document4 pagesEco2874 597Xonax PratiNo ratings yet

- Eng1056 7953Document4 pagesEng1056 7953Samantha GalizaNo ratings yet

- Maus de Rolley - Main DocumentDocument27 pagesMaus de Rolley - Main DocumentErick VarelaNo ratings yet

- Teatro Grecia y Roma. Asientos - BEARE, W. (1939)Document6 pagesTeatro Grecia y Roma. Asientos - BEARE, W. (1939)glorydaysNo ratings yet

- Math7881 7123Document4 pagesMath7881 7123Shilla Mae BalanceNo ratings yet

- Acc3937 2618Document4 pagesAcc3937 2618afiq1229No ratings yet

- Psy2780 5177Document4 pagesPsy2780 5177Mae Danica CalunsagNo ratings yet

- 8683Document4 pages8683Vidzdong NavarroNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledflorever maniaNo ratings yet

- Hist8671 7559Document4 pagesHist8671 7559muhammad zulfikarNo ratings yet

- The Mesha Stone - A Reappraisal of A ForgeryDocument6 pagesThe Mesha Stone - A Reappraisal of A ForgeryDavide VenturaNo ratings yet

- Blackman, An Indirect Reference To Sesostris III Syrian CampaignDocument4 pagesBlackman, An Indirect Reference To Sesostris III Syrian Campaignwetrain123No ratings yet

- Math7881 7145Document4 pagesMath7881 7145Shilla Mae BalanceNo ratings yet

- Phys271 3507Document4 pagesPhys271 3507Yakobus Benyamin Renno ArwalembunNo ratings yet

- !generate5918 3329Document4 pages!generate5918 3329Alex ChávezNo ratings yet

- Ancient Egyptian Donation Stela in The Archaeological Museum of Florence (Inv. 7207)Document7 pagesAncient Egyptian Donation Stela in The Archaeological Museum of Florence (Inv. 7207)ALaa AhmedNo ratings yet

- Econ714 302Document4 pagesEcon714 302Davian GreyNo ratings yet

- Chem 8607Document4 pagesChem 8607Dinesh Venkata GoggiNo ratings yet

- Archaeologica: Vol. X FascDocument30 pagesArchaeologica: Vol. X Fascmark_schwartz_41100% (2)

- The Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionDocument8 pagesThe Oracular Amuletic Decrees A QuestionAankh BenuNo ratings yet

- Black Ships and Sea Raiders History Arch PDFDocument16 pagesBlack Ships and Sea Raiders History Arch PDFNasai Littarru Sampedro100% (1)

- MNGT 6933Document4 pagesMNGT 6933NicoNo ratings yet

- Hist7013 1403Document4 pagesHist7013 1403Deniel DenamarcaNo ratings yet

- Math2341 7836Document4 pagesMath2341 7836IvanwbsnNo ratings yet

- Economic Efficiency of Smallholder Farmers in Tomato Production Inbakotibe District Oromia Region Ethiopia PDFDocument8 pagesEconomic Efficiency of Smallholder Farmers in Tomato Production Inbakotibe District Oromia Region Ethiopia PDFsolomon dejejenNo ratings yet

- 20102023-UnlockedDocument7 pages20102023-UnlockedMittun 3009No ratings yet

- D PK 0707398 BibliographyDocument7 pagesD PK 0707398 Bibliographyarwani majidNo ratings yet

- From Novice To Expert Theory - Lucille Alkhaldi BSN RNDocument11 pagesFrom Novice To Expert Theory - Lucille Alkhaldi BSN RNmaha_alkhaldi100% (1)

- Type 9, 12, 16, 20, 24 & 36 Brake Chamber (SD-02-1302)Document4 pagesType 9, 12, 16, 20, 24 & 36 Brake Chamber (SD-02-1302)Angel Dlsg100% (1)

- Answer:: Multiple ChoiceDocument17 pagesAnswer:: Multiple ChoiceQuenie Jeanne De BaereNo ratings yet

- The Nibbāna Sermons 1 To 11 by Bhikkhu K Ñā AnandaDocument24 pagesThe Nibbāna Sermons 1 To 11 by Bhikkhu K Ñā AnandaCNo ratings yet

- 8 Features of The Caste SystemDocument2 pages8 Features of The Caste SystemSaurabh TiwariNo ratings yet

- Hitler and GermanentumDocument17 pagesHitler and Germanentumlord azraelNo ratings yet

- Standard Practice (SP)Document9 pagesStandard Practice (SP)nizam1372No ratings yet

- EasyFile MANUALDocument29 pagesEasyFile MANUALRonald Luckson ChikwavaNo ratings yet

- GU Balance Routine Testing enDocument12 pagesGU Balance Routine Testing enasalazarsNo ratings yet

- Training Project ReportDocument62 pagesTraining Project ReportGaurav Singh Bhadoriya0% (1)

- Hastage Magazine's Latest DECEMBER Issue!Document66 pagesHastage Magazine's Latest DECEMBER Issue!HastagmagazineNo ratings yet

- G10-2nd-Q-review Sheets-Chem-Chap7, 8.1, 8.2Document8 pagesG10-2nd-Q-review Sheets-Chem-Chap7, 8.1, 8.2Karim Ahmed100% (1)

- Investors Sentiment in India SurveyDocument12 pagesInvestors Sentiment in India SurveyZainab FathimaNo ratings yet

- Delta Marketing TrendsDocument7 pagesDelta Marketing TrendsCandy SaberNo ratings yet

- 0606 Additional Mathematics: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2014 SeriesDocument6 pages0606 Additional Mathematics: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2014 SeriesKennedy Absalom ModiseNo ratings yet

- JutlandicDocument24 pagesJutlandicmorenojuanky3671No ratings yet

- Poverty 2Document9 pagesPoverty 2Camid AlanissahNo ratings yet

- Canteen Block - Report DailuxDocument106 pagesCanteen Block - Report Dailuxkailash kumar soniNo ratings yet

- Fourth Quarter-Grade-7-MathematicsDocument4 pagesFourth Quarter-Grade-7-MathematicsJosefina TabatNo ratings yet

- Ana&Physio 16 - Human DevelopmentDocument37 pagesAna&Physio 16 - Human DevelopmentShery Han Bint HindawiNo ratings yet

- Bella Luna (Jason Mraz With Chords)Document5 pagesBella Luna (Jason Mraz With Chords)Mario CorroNo ratings yet

- Grammaire - L1 G1+3+4+7 - M. Benkider - Corrigé Et CommentairesDocument3 pagesGrammaire - L1 G1+3+4+7 - M. Benkider - Corrigé Et CommentairesYssoufFahSNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Composition and Backtesting: Dakota WixomDocument34 pagesPortfolio Composition and Backtesting: Dakota WixomGedela BharadwajNo ratings yet

- Sewers For Adoption: - A Design and Construction Guide For Developers - Small Developments Version - September 2013Document48 pagesSewers For Adoption: - A Design and Construction Guide For Developers - Small Developments Version - September 2013humayriNo ratings yet