Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

31 viewsThe Curse of White Oil Electric Vehicles Dirty Secret Electric Hybrid and Low Emission Cars The Guardian

The Curse of White Oil Electric Vehicles Dirty Secret Electric Hybrid and Low Emission Cars The Guardian

Uploaded by

hahaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Millions of Electric Cars Are Coming What Happens To All The Dead Batteries Science AAASDocument1 pageMillions of Electric Cars Are Coming What Happens To All The Dead Batteries Science AAAShahaNo ratings yet

- Electric Vehicles - Analysis IEADocument1 pageElectric Vehicles - Analysis IEAhahaNo ratings yet

- Compared To Gas Powered Electric Vehicles Cut Greenhouse Emissions Over 30Document1 pageCompared To Gas Powered Electric Vehicles Cut Greenhouse Emissions Over 30hahaNo ratings yet

- WWW Treehugger Com Do Electric Cars Make Noise 5205280 - Text Why 20are 20electric 20cars 20so The 20wind 20resistance 20while 20drivingDocument3 pagesWWW Treehugger Com Do Electric Cars Make Noise 5205280 - Text Why 20are 20electric 20cars 20so The 20wind 20resistance 20while 20drivinghahaNo ratings yet

- Fenvs 10 810342Document9 pagesFenvs 10 810342hahaNo ratings yet

- Ourworldindata Org Energy Mix Text Globally 20we 20get 20the 20largest Still 20dominated 20by 20fossil 20fuelsDocument14 pagesOurworldindata Org Energy Mix Text Globally 20we 20get 20the 20largest Still 20dominated 20by 20fossil 20fuelshahaNo ratings yet

- Quietest Cars Do Electric Cars Make Any SoundDocument1 pageQuietest Cars Do Electric Cars Make Any SoundhahaNo ratings yet

- WWW Iea Org Reports Electric Vehicles Fbclid IwAR2Hb0q3VT2zirqdJPECZntpL6UOdldZNbojqzuKVJ7qqH45Jfkn0X9Lu oDocument7 pagesWWW Iea Org Reports Electric Vehicles Fbclid IwAR2Hb0q3VT2zirqdJPECZntpL6UOdldZNbojqzuKVJ7qqH45Jfkn0X9Lu ohahaNo ratings yet

- Cars Are Going Electric What Happens To The Used BatteriesDocument1 pageCars Are Going Electric What Happens To The Used BatterieshahaNo ratings yet

- A Dead Battery Dilemma: News Home All News Scienceinsider News FeaturesDocument7 pagesA Dead Battery Dilemma: News Home All News Scienceinsider News FeatureshahaNo ratings yet

- Electric Vehicles A SmartDocument5 pagesElectric Vehicles A SmarthahaNo ratings yet

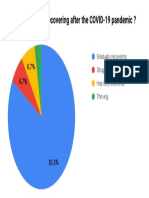

- How Tourism Is Recovering After The COVID-19 PandemicDocument1 pageHow Tourism Is Recovering After The COVID-19 PandemichahaNo ratings yet

The Curse of White Oil Electric Vehicles Dirty Secret Electric Hybrid and Low Emission Cars The Guardian

The Curse of White Oil Electric Vehicles Dirty Secret Electric Hybrid and Low Emission Cars The Guardian

Uploaded by

haha0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

31 views2 pagesOriginal Title

The curse of white oil electric vehicles dirty secret Electric hybrid and low emission cars The Guardian

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

31 views2 pagesThe Curse of White Oil Electric Vehicles Dirty Secret Electric Hybrid and Low Emission Cars The Guardian

The Curse of White Oil Electric Vehicles Dirty Secret Electric Hybrid and Low Emission Cars The Guardian

Uploaded by

hahaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 2

‘Thecurseof whiteoil:

clectricvehicles dirty

secret podcast

@xesdmore

Sed

WUCKee Mick ie

electric vehicles' dirty

re cai

The race ison to nda steady source of

lithium, a key component in rechargeable

electriccar batteries, But while the EU

focuses on emissions, the lithium gold rush

threatens environmental damageonan

industrial scale

by Oliver Balch

‘ven befor the new mine became the main topic of village

conversation, lo Cassote, a 44-year-old lvestock farmer, Was

thinking about making change. Living off the landin Ns

‘mountainous part of northern Portugal wasa grind. his close

childhood fiends, he was the only one whe hadnt gone oversasin search

of work- So, in 2017, when he heard of a British company prospecting for

lithium in the region of Tis os Montes, Cssote called hisbankand asked

fora €200,000 loan He bought John Deere tractor, an earthmoverand a

potable waterstorage tank.

"The exploration team ofthe UK-based mining company Savannah Resources

had spent months pring over geological maps and surveys ofthe ils that

pple out fom Casote's farm. nal calculation indicated that they could

‘onan mare than 280,000 tonnes of thm, a siverwhite alkali metal

‘enough for 10 years production. Cassotegotin touch with Savannah's local

ofc, andthe mining rm duly conzacedhim to supply water tothe test

‘months onthe company'sbooks, Cassotehad made what he would usually

team n five or sx years onthe farm,

Savanah isjust one of several mining companies withaneyeonthe ich

surtounding petro branco shite ol” derives rom an invention ately

Seen in these parts: he electric ca. itu sa key active materi inthe

‘rechargeable batteries that run elect cars, Iti found in rackand clay

‘epost asa slid mineral as well as dissolved in brine. es popular with

buatory manufactures because 35 the last dense meta, istres ala of

lectfying transport has become a top priority in the move toa lower

carbon fatten Europe, car ave accounts or atound 12% ofl the

continents carbon emision. To keepin ine with the Pars

‘missons from cars and vans will sed to drop by more than a third 37.5%)

'by2020. The EU has stan ambitious goa of reducing overl greenhouse gas

missions by 5% by the same date. To that end, Brussels and individual

ember tates re pouring millions of ears into incentvising at owners to

site to elec. Some ountres re gong even further, propesng9 ban

Sales of diese and petrol vehicles inthe near fate as erly 382025in the

‘ase of Norway. al goes to plan, European elect vehicle ownership

oul jump from around 2m today to gam by 2030.

Lithium s key to this energy wanstion. Lithium ion batteries are used to

power electric ars, a wel asto store gri-scale electricity (They ae also

‘sed insmartphones and laptops) But Europe asa problem. At preset,

almost every ounce of battery grade lithium imported. More than half

(65%) fglotallithium production ast year eiginatd in just one country

Australi. Other principal suppliers, such as Chile (2%), China 10%) and

Argentina (9, are equally fa-ung,

Lithium deposits have been discovered in Austria, Serbia and Finland, butt

'sin Portal that Europe's gest ithium hopes. The Portuguese

overnment preparing offer iene for tim ining tointerational

‘wn back yard not only offers Europe simpler lusts and lower pices, but

fewer tanspor-telated emisions.fralso promises Europe security of supply

~ anissve given greater urgency bythe coronavirus pandemic’ disruption of

sobal ade

‘Bven before the pandemic alarm was mounting about sourcing ium. De

Thea Rifrancos, a political economist at Providence College in Rhode ltd,

pointed to growing trade protectionism and th recent US-China trade spt.

(and that was before the trade ow between China and srl Whatever

‘ores BU poieymakers might have had before the pandemi, she a,

“now they must bea milion times higher”.

‘he urgency in geting Ithium supply has unleashed a mining boom, and

the race for “white oi threatens to cause damage tothe natural

‘environment wherever is found, But becuse they are helping to drive

dove emissions the mining companies have BU environmental pelicy on

consumption and production that we now have, whichis simply not

sustainable" sad Riofances. “Everyone havingan electric vehicle

In thetiny hamlet of ur in Trs-o8 Montes, Cassot as concerns of his

‘own, The prospecting phase ended earlier his year, and his expensive new

‘machinery is standing ile nhs Farmyard Savannah is waiting or the Ral

len ight rom the Portuguese government fr thium mine. I

approved, the companys promising to invest 105m inthe projec. twill

‘mind, He ust wants tobe back on his earthmover

‘fer three decades ving in Amsterdam, Maro Inacio, a 50-year

‘old profesional dancer, recently returned this home in

Portugal with plans to Bila yoga etreat deep inthe

‘Countryside - somewhere icolicand isolated whete gues could wake to

the sound ofbirdsong,

Inacio and his partner, Miko Prins, had identified the perfect pot an

abandoned farmstead setin 47 acresof grassy wilderness in central Portugal

The main house would requ considerable renovation, but the rest was

forthe fst time nace dreamed ofthe changes they coukd make extending

the house of othe ide, converting the outhouses into private ving |

quarters, carving out natural poo in the rocks. He pinpointed the spt for

‘he yos studio: a smal ise with expansive views over the grounds and out

Six years after the couple firs set yes onthe place, Cinta Dasa Nova i

ow ead to open its doors to paying guests The global pandemics

‘eating shortage of iteratonal lens and making dificult tl

fine rooms, buta much greter worry hangs over the business in which

Inacio has invested his fe savings. Moving to one ofthe lage ground-floor

windows ofhisnew heme, he peinted tthe lsh expanse of open county

outside. “Any ofthis could be exploited fr lithium soon Possible

‘exploration onder hang aver all of.>

‘mn the pas few years, smal groups of ansious residents have come together

across Portugal, concerned about he government's itium plans. With ew

facts inthe public domain thes groups started making inquires to local

planning departments and town alls In Inacio case, he sid that he was

told his requests would be passed on, Henever heard any mor,

tthe same time, ey stage exploration works, led by the es of Savanna

country. An objector unearthed a technica assessment of Portugal's ithium

resources commissioned by the energy ministry in 2016, Eventually. a

{overnment spokesperson confimed that sessions were under way with

‘aos mining companies, but sid nom decisions fad yet ben made.

‘Then, in January 2920, 2 map began cltclating among the vious WhatsApp

and Facebook groupe set up by concerned residents like Inacio. The map, put

together by a local software developer specialising in cartography, appeared

toconfitm their worst feats. A tapestry of geometric shapes spread across the

country’s inteio abutting designated nature reserves. eres of lca and

‘ational protest, including a march in Lisbon lst year, sought orale

‘awareness about the impacts of modern mining on the natural envionment,

Including potential industrial scale habitat destruction chemical

contamination and noise pollution 25 wellas high lvels of water

onstmption, They alzo raised concetns ao the impact on ours - an

«comomic mainstay forthe country's nero, with an anual turnover of

‘exs.abnin 2019.

‘All these concerns appear in “national manifesto” recently publshedby

cealtion of civic movements. Despite vociferous local media coverage, they

have made litle impact so fa. In part, this reflects the relative weakness of

‘he national envonmental movement. Prtgalis nef the Fev countries

in Europe not tohave a Greenpeace ails for instance, an accordngtoan

pty more for eeo-branded products

For Maria Carmo, a 43-year-old university lecturer fom the village of Barco,

Inthe contral district of caste Branco, sch ack of engagement reveal the

alienation that most urban or coastal-dweling Portuguese fel towards the

country’s rural heartlands. The trend in the pas 0 years ors hasbeen one

of continued rural depopulation, Hundreds of thousands of people have lft

Portugal's poor and already nder-populated interior for new ives abroad or

Inthe country's coastal cites, Few of them return,

fa mining licences ranted in their region, nacioand small coreof

dichad supporters ae prepared to fight it inthe courts. Carmo s ss sue

er campaign group in Cartel Branco has aleady split, with alts

‘members now open the possibilty ofan open-pit ithium mineaboveher

village. twill happen anyway, they ay, so why not negotiate some

arantes? Barco wed tohave tin mine, the vllgers ase, and it wasnt

sobad

befreit closed in the early 1960s. Back then, mining was small-scale and

subterranean. Anew mine, in contrast, could se hal the hil disappear

poteialy damaging th resin of « ease age seticuret on ts pre

‘Villagers also fear that chemical runof wl polite by Zener eve

‘which they depend on for thei cops.

‘Aer a three-year struggle, Carmo is exhausted and ready to given. she ees

‘the government s deaf, and tha er fellow citizens aren interested. “So

‘much destruction” she sald. “And fr what? So eco-minded urbanites in

voeates of Portas hopes lithium boom are that aca

They point out tat innovation uch as windfarms, sla energy

parks and hydrolects plans, whe contebuting towering

CCozemissions inthe longterm, all ave ome impact on local populations.

{ma noteto investors, Savannah observes tha is proposed mine which

boasts projected revenues of USS15sbn overt intial 1-year lifespan) will

contribute to enough battery packs to prevent the emission of 100m tonnes

‘earbon dene

Savanah’ chit executive, David Archer, goes even father. Speaking fom

his London office, he pitched his firm's maltimiion-lise investment 5

lose imple: thlum equal batteries, which equal electri crs, which

‘uals an end transport emissions, which equals a wordless vulnerable to

today’s climate emergency He adds the prospect of new obs in thelocal area

(up t0800 in Trés-os-Monts, higher taxrevenues anda €¢37m boos to

brainer

‘The Portuguese government concurs. Ina promotional vdeo targeted at

foreign investors, the secretary af state or the envionment named his

‘country “ane of the world’s eaders in energy tanstion, The shor fm

stresses the current governments strong commitment” toa policy of eco-

lnmpacte are akost always overlooked. The same lea has setback

International climate talks fo decades, sad Mayet Sigh, global imate

ea forthe campaign group ActionAid. The global north wants stricter

missions tages: the global south wants economic development nov. and

reasonably feolsthat te burden of tackling the climate criss should fllon

the post-industrial societies primarily response for causing it. "Green

technologies ar eatentil or the transition to renewable energy? Singh sid,

“but they ae not without negative impacts and] we need to ensure these

don't always fallon the poorest and most marginalised communities”

‘In chile, the bate over the impact of mining has been gong on for years.

‘Born and brought upin the copper-poducing region of Oggi in ent:

Chile, community activist Ramen Balzar, now 36, became avare ofthe

potential damage of age scale mining at an sey age Lona-ninning

disputes overland use, water rights and chemical contamination - provided

the background this youth nthe 90s. Then, sx years ago, he moved tthe

northern tpost of Sn Po de Atacama, On the lip ofthe cues famed

‘hy, Balzar finally fl abet breathe feely

‘He did not know it bute ad walked nto another bate zone. San Pero

lies on the westernmost pint of aiming aea that spreads north across he

‘Atacama desert to Bolivia and east int Argentina. Fifty times drier han

California's Death valley the area's parched surface conceals an underworld

"chm minerals. Historically, mining companies have exploited its lucrative

Aeposis of copper and toa lesser extent, odin and nitrates. By some

estimates, also contains as muchas hal the world’ thium reserves. nthe

‘aly to mid2o%0s, when alk of itlum-on batteries Began culating in

‘every mining town, ara new licences were requested, investments

‘made, and extraction facitios expanded, Thearea became known a the

“ham rangle’

‘The mining companies insist their operations are sustainable. alcizat,

speaking from Mexico City, where hes studying fora raduate esearch

lithium extraction on sucha large scale wll have onthe Atacama’ fagle

natural ecosystem. Unlike Portugal lithium here isfound in brine so the

‘mining operations use no dynamite and no earthmovers, and threaten to

leave no unsightly crater. Instead, they consi ofa series of age, neatly

Searegated evaporation pools le with milion of ites of brine that have

been pumped from below the surface and left evaporate i

The fears of esidents like Baledzar ae focused onthe areas cavernous,

subterranean aquifers from where the brine pumped Here, they maintain,

‘sate isunfoding, Theresa risk thatthe eserves ean water, which

‘contaminated

Balefat hasbeen working withthe Plurinatonal Observatory of Andean Sat

Fats, a network of expert scentiss ad concerned ciizes,tochat changes

tothelocal ecology. The weight oftheir evidence shrinking pasturelands

failing crops, ésappearing flora and fauna all pont towardsa process of

eseriicaton which they believe is exacerbated by lithium extraction. The

impact of disturbing "huge, complex hydrological system” isnot visible

fom one day to the next, said Baeza. "Bu the two ate interlinked, without

any dob

Plans Iithivm mining firm SOM to expand its operations were recently

‘locked by acilean court on environmental grounds, but almost every

othe efor to get the backing ofthe autho has fale. tn Chile, Baleszar

‘ld certain teritores and natural environments have always Ben

“actifienble” inthe name of prowess.

ie mining rms scour the world’s deserts and countryside

forlithium concentrate, a parallel search son to ind waysof

‘avony, Chistian Hanlch set out t discover aoltion in teeyeling. “What

instead of extracting ving ithiu fom the ground, we use what we

slready have" he said, lf millon tonnes of ehiumn hasbeen extracted

and refined inthe pat decade, much of which now sts in dscaded mobile

Ins modest fis or office at Duesenfeld, the company hecofounded

while working on his PhD at Braunschweig University of Technology,

Hanisch, 37, admitted thatthe logistics are challnging. The lithium-ion

batoris in everyday devices are typically small and fly soto make is

venture viable, Hanisch decided to start bg, with used electricear batteries

(hich each contain about Sk of reusable ith) He pointe out of the

tarmac outside the factory next doo, each the sz fa chunky matte.

‘Removing the batery'sheavy plastic casing is easy enough the challenges

how to acess the lithium inside the battery cel isl. Current, wo main

options exis either heat the components to about 300C to evaporate the

lithium, or apply acdsanothereucing agents to leach it Both

exploding) adits amalgamation wth ater metals hich te added in or

beter conductivity

‘With market analysts predicting a potential 12 old increase inthe value of

the global ithium recycling industry over next decade, to more than $186n

'by2020, competition among eeytng innovators is ottng up n Germany

lithium recyclers, Across the border in Belgium, former smting fi

tured urban waste recycler, Umicore is developing its own technology, but

releasing no details. Another sigiicant European player i Snam, in France,

anischis confident that his procedure hasan edge. Rather than smelting

(hich sgh energy intensive) or leaching etremely toxic, DuesenFelé's

approach ishased on mechanical separation. This method involves

physialy breaking the battery down into its component partsandthen

crating the residual lithium viaa combination of magntisation and

Aisttaion,

Inthe company’s fictry amida cacophony of whiting and clanking, a

sulbmarine-ke cylindrical contraption that's the usher, shouted

Hanisch through the ear protectors clamped to my head) occupies the back

belts punctuated by worktops Quite where the production ie begins or

ends isunclear. Hanisch regarded his invention with Bssfuexpresio,

“tsmoisy he conceded, “But t's the greenest way of recycling tum there

background that ingpred his envconmental ambitions, Earths yar he

launched consultancy venture, No Canary, advising on low-carbon

‘methods fo producing not just battery butan entire cectrc vehicle from

thematevals stage through to final disposal Greta(Thunberg waht",

enough on decanbonisation”™

Sifting away from petrol and desl snot the only concern. Manufacturing

any ca, elector aterwise cases carbon emiesion, be

used to smelt the sce! for is body work or the diesel oll burned when

shipping lectronic components across oceans. The extra materials and

present, the carbon emissions associated with producing an

higher than those fora vehicle running on peta dlesel-by as much as

‘3, according to some cleulatlons, Un the electricity in matinal gid

ently renewable, recharging the battery wil ivolvea degre of

dependence on coal or gas fired power stations,

Lithium acounts fora small pot ofthe battery'scost, which means there is

less incentive for manufactuters to findanaltenative sits, ecyeling

lithium costs mare than digging it out ofthe ground, For Hanisch, one ofthe

chit costs comes atthe end ofthe process: converting the recovered lithium.

‘fom its recycle state ithium sulphate) into abatery-ready form dthium

aoa). Without the resources to bul his oe chemical plan,

Duesenfed sends his end produc 2 grainy compost of precious metals

Gaines an exper in battery recycling systems at Argonne National

Laboratory i lini. As she sa: “The main purpose eto recover the

colt, as wellas nickel and copper. The ith doesnt add much:

swith wind turbines and solar panel, the price f recycled lithium wll

‘roves true, theresa huge supply: demand imbalance to get over. Before the

pandemic, otal sales ofelectre vehicles wee projected to more than

«quadruple in the next five years to more than lim units. Demand frlithium

vllsise accordingly, with one industry estimate suggesting annual

consumption could easly each 700,000 tonnesby the middle ofthis

decade. So, even if Duesenfeld and its competitors were able to recycle evry

last ounce ofithium produced inthe last decade, come 2025 it weuld only

tbe enough to power new let vehicle batteries for nine months.

sitturs out the ocesion caused by the pandemic may have

sranted campaignersa reprieve, halting the immediatenced to

‘open new lithium mines. With the word facing prolonged

tsi, ne ers ever eco-friendly anes-are not tthe top of

‘most people's prionities. As manufacture as slowed dawn, aglutfithium

‘on global markets has dampened the white oi boom, fon temporal.

‘ut investors remain bullish about thu’ long-term prospects With a

change of regime nthe White Hous, there is hope fr renewed support for

measures to tackle the climate criss. nthe fortnightfter the US election,

{he stock pice of Chile-based thm mine company Albermarle rove by

‘more than 20%. Inthe UK, Bots Johnsons announcement about binging

forwatd.aban on new desl and petrol cars to 2020 gave the market boost

‘The European commission sill wants ithium industy toca tsown. In

September, the Slovak diplomat and a commission vice president Marob

Scléwi publicly endorsed Portaga®s pans necessary” forthe

automotive sector. What's more the European investment Bank would be on

hand to help he promised is comment chimed with the lunch ofa new

EU strategy on aw materials, which, among other goals, seeks to increase

Ewope’ lithium supply 18-old by 2030, while reducing Europes

dependence on third-party counties.

Seféovié offered them a crumb of comfort, The decision to mine has tobe

taken in dialogue “with local communities" easerted, adding that we

‘eed to asure these communities that these rojectare nat only ofthe

‘sreatest importance, but willalso benefit the region and the county”

‘The modern corporate responsibilty movements ult on such loge ust,

| docs not promis to climinate ll negative industrial impacts Instead

pledges to “manage” them, and then tobalance out any damage with

compensatory “benefits fouse Seféovi's phrase. In the case of Savannah's

‘mine in northern Portugal, the company concedes ere willbe local

‘environmental impact, bat argues that wil be outweighed by the upsides

(Gnward investment, jobs, community projects).

‘Smile rtoyaptnen College of Artin London i sceptical. Hs ist-hand observations ofthe

‘Sirona exploitation of Chile's st flats suggest that oes of dialogue can be

‘uperical. ven in Atacama, where international aco give indigenous

‘sroups the right to “ie, pir, informed consent, detractors such as

Balczar strugle tobe heard Instead, the view of pro-mining community

|roupsis taken as universal If necessary, the obligation to gain consent

be weakened simply by defining ium asa mineral of "strategie" or

extcal” national value - which easy enough, given ithium’scotebuton

toslowing global heating and cleaner a.

"Nor, very often do the promised trade-offs tm out tobe quite what they

Intaly eem, according to Peet The voluntary nature of corporate

responsiblity means mining firms ean bcktackift suits them. Even when

local groups succeed in negotiating axed royalty (2% ofsales, inthe ase

of one major extractor in Atacama), communities frequent splitin the

subsequent fight forthe spoils.

Digging up Portugal's mountains inthe name of green technology may stil

bbeavoidable. An alternative ess controversial technology could break onto

the sene. Green hydrogen, for instance could help ost up to 10% af

"Euope’semissions. A more immediate solution would be to rethink how we

setafound. As Thes Rofancos at Providence Callege pointed out,

everyone were to adopt “rational forms of transport -such as trains, trams,

‘e-buses, yeing ad car-sharing then demand fr passenger vehicles of all

tainds would shrink overnight.

For Portugal's ant-nining groups, however, the clocks ticking. Gadotiedo

augue tat etizens must demand dialogue, in onder "gota conversation

joing about what model of development we want I people were attr

Informe he reasoned it's jst posible tat public opinion could swing to

their sie, and the country's itm mining plans could et shelved. tn this

regard recent demands by Portuals Green prt for anational impact

‘valuation of mining policy is promising.

‘Portugal protesters can sce tha blocking green growth wont get them ft

"These interior regions need investment. Hence the banner hanging fom the

playground fence inode Casote's neighbouring village, which reads “Sima

Vide" Ves tole) beside “Nao Mina” (No tothe Mine). “Lie” fr opponents

ofthe mine, including Mario Inacio an Maria Carmo, is eco-tourism,

living For Cassote, it means a decent wagefora decent dy's work Fora

{green future, t's going tobe vital to accommodate both visions.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Millions of Electric Cars Are Coming What Happens To All The Dead Batteries Science AAASDocument1 pageMillions of Electric Cars Are Coming What Happens To All The Dead Batteries Science AAAShahaNo ratings yet

- Electric Vehicles - Analysis IEADocument1 pageElectric Vehicles - Analysis IEAhahaNo ratings yet

- Compared To Gas Powered Electric Vehicles Cut Greenhouse Emissions Over 30Document1 pageCompared To Gas Powered Electric Vehicles Cut Greenhouse Emissions Over 30hahaNo ratings yet

- WWW Treehugger Com Do Electric Cars Make Noise 5205280 - Text Why 20are 20electric 20cars 20so The 20wind 20resistance 20while 20drivingDocument3 pagesWWW Treehugger Com Do Electric Cars Make Noise 5205280 - Text Why 20are 20electric 20cars 20so The 20wind 20resistance 20while 20drivinghahaNo ratings yet

- Fenvs 10 810342Document9 pagesFenvs 10 810342hahaNo ratings yet

- Ourworldindata Org Energy Mix Text Globally 20we 20get 20the 20largest Still 20dominated 20by 20fossil 20fuelsDocument14 pagesOurworldindata Org Energy Mix Text Globally 20we 20get 20the 20largest Still 20dominated 20by 20fossil 20fuelshahaNo ratings yet

- Quietest Cars Do Electric Cars Make Any SoundDocument1 pageQuietest Cars Do Electric Cars Make Any SoundhahaNo ratings yet

- WWW Iea Org Reports Electric Vehicles Fbclid IwAR2Hb0q3VT2zirqdJPECZntpL6UOdldZNbojqzuKVJ7qqH45Jfkn0X9Lu oDocument7 pagesWWW Iea Org Reports Electric Vehicles Fbclid IwAR2Hb0q3VT2zirqdJPECZntpL6UOdldZNbojqzuKVJ7qqH45Jfkn0X9Lu ohahaNo ratings yet

- Cars Are Going Electric What Happens To The Used BatteriesDocument1 pageCars Are Going Electric What Happens To The Used BatterieshahaNo ratings yet

- A Dead Battery Dilemma: News Home All News Scienceinsider News FeaturesDocument7 pagesA Dead Battery Dilemma: News Home All News Scienceinsider News FeatureshahaNo ratings yet

- Electric Vehicles A SmartDocument5 pagesElectric Vehicles A SmarthahaNo ratings yet

- How Tourism Is Recovering After The COVID-19 PandemicDocument1 pageHow Tourism Is Recovering After The COVID-19 PandemichahaNo ratings yet