Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Enunciation in LotR

Enunciation in LotR

Uploaded by

Krish ParwaniOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Enunciation in LotR

Enunciation in LotR

Uploaded by

Krish ParwaniCopyright:

Available Formats

Introductory note This paper was written for Journeys Across Media conference that took place at the

University of Reading in April 2004. Minor details have been adapted for this version.

Aspects of enunciation in The Lord of the Rings significance of medium specificity and hybridity

When part one of the film trilogy, The Fellowship of the Ring, first came out, many so called purist fans of the book thought it was the work Sauron, if not Morgoth himself! Which I think comes from a distorted conception of what a book to film transfer can achieve and what it cannot. And this is precisely what were trying to find out when talking about medium specificity: We are telling apart the elements that can be transferred from those that belong to only one medium. Narrative elements generally are transferable (although it might get a little awkward when it comes to omniscient narrators or internal monologue). Then, there are aspects like atmosphere, mood and tone, which are difficult to describe, but generally are transferable.1 Last but not least there are enunciative elements that need to be considered. In terms of literary adaptations this (very roughly) means to bring the book style to the silver screen. And this is where most purists would say Peter Jackson has failed. Because in most cases style needs not only to be adapted, but to be transformed in order for it to work in another medium. Passages where it can be simply transferred are rare. But lets take a look at an example.

In fact, it is precisely because of their evasive nature that they are more open to transfers. And it is my opinion that these are the elements (especially tone) which are key to successful literary adaptations.

(c) Tim Langer 2004, www.medienberater.de

The bridge of Khazad-dm aka the Balrog sequence.1 In the handout (see last page) youll find many passages that are pretty hard to translate from book to film. Almost at the end theres: From out of the shadow a red sword leapt flaming. Glamdring [Gandalfs sword] glittered white in answer. The answer could be translated to film by simply shooting a reverse angle which would a bit too much of a juxtaposition in my opinion, but apart from that would work fine. But how do you translate the paragraphs? Obviously, it was not enough for Tolkien just to write two sentences, but he emphasizes their relation to one another by giving them their own respective paragraphs. Or how do you translate the capital S in Flame of Udn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass! It is not quite clear to me why Tolkien used a capital letter in the first place The Shadow could be Sauron himself, it could be a synonym for the Black Pit where you Balrogs normally dwell, it could have been a mood of the author, but its one of the very Tolkien-typical things to just hint at things and to pretend there is a larger background.2 Elements like these, tiny details like a capital S, are simply impossible to translate into film. But there is another aspect about this passage which is far more important. The Bridge of Khazad-dm has been the source of much and heated debate ever since the book first came out, because here the world-shattering question originates whether or not Balrogs have wings. All that Tolkien does is to switch from a simile to metaphor: The Balrog reached the bridge. Gandalf stood in the middle of the span, leaning on the staff in his left hand, but in his other hand Glamdring gleamed, cold and white. His enemy halted again, facing him, and the shadow about it reached out like two vast wings. [] The Balrog made no answer. The fire in it seemed to die, but the darkness grew. It stepped forward slowly on to the bridge, and suddenly it drew itself up to a great height, and its wings were spread from wall to wall Peter Jackson is of course aware of the debate as such (although he is other than myself in favour of the wings), and instead of just giving the beast a pair of wings, he plays with the switching of stylistic means.

1 2

The Fellowship of the Ring, chapter #30 (Theatrical Version), A few pages prior to the Balrog passage, Aragorn says about Gandalf that he would find the way through the dark as safely as the cats of Queen Berthiel without ever mentioning neither queen nor cats ever again in any his works.

(c) Tim Langer 2004, www.medienberater.de

New Line Cinema 2001

But what happens is that elements which in the book belonged to enunciation (especially the metaphor) now turn into something that I would rather ascribe to the narrative. The enunciative aspect of the passage switches from the level of style to a meta level: Peter Jackson is playing games with the audience: now you see it, now you dont. The wings issue is not the only time this sort narratization happens. In both the book and the film, Balrogs are ominously described as Shadow and Flame, which for a book is a simple thing to say, but for a film a difficult thing to show, and I think the film-makers did an excellent job here. Shadow, the way Tolkien used it (although he is not using it in this passage), is more than just the absence of light, it is something that can be worn like a cloak, but taking a more active role. When so-called purists complain about a three meters tall Balrog with wings and horns aspects that undeniably can be argued about , they forget to take into account the points where the film definitely succeeded. The Bridge of Khazad-dm is one of these. And purists tend to look only for book enunciation in the film, instead of enjoying also the films own enunciation something the book cannot offer.

(c) Tim Langer 2004, www.medienberater.de

Mise-en-scne the painting sequence It seems a strange thing in analyses of book to film transfers that people tend to overlook anything that is not in the book. I think it is not only valid but absolutely necessary to also talk about elements proper to film, because in the end we are talking about a film, not about a book. And one of the stylistic means proper to film and film alone is, of course, mise-en-scne. Here, the director has absolute control over all spatial elements. In the second example, mise-en-scne which as a stylistic means Id rather attribute to enunciation, nevertheless has a very clear narrative purpose. As before, one has to look closely in order to decipher the passage and you need to be familiar with the background of the story. The passage is in its totality all but incomprehensible for a Tolkien-newbie.1 The sequence begins with Aragorn picking up the hilt of the sword which had been dropped a few seconds before.

New Line Cinema 2001

As long as Aragorn is alone in the frame, it is purely a family matter Aragorn is captured in the past of his ancestor: between the statue holding the shards, and the painting showing Isildur lying on the ground, almost defeated, before the Dark Lord. Sauron is concealed by the pillar to the right. The narrative background of this moving still-life is that Aragorn doubts his role as the future king, he is uncertain if he will be able to withstand Sauron.

Which is why a short overview over the characters involved in the sequence seems appropriate here. 3000 years ago, Isildur cut the Ring off Saurons hand. Unfortunately, he then did not destroy it, but kept it for himself. Thus, Evil was allowed to endure. The shards of the sword he used as well as a painting depicting the battle are being kept in Rivendell. Now his heir Aragorn is expected to take on Sauron, and by overthrowing him, become king otherwise he will not be allowed to marry the (immortal) elf Arwen, whose father fought alongside Isildur. Sequence taken from The Fellowship of the Ring (Theatrical Version), chapter 21.

(c) Tim Langer 2004, www.medienberater.de

New Line Cinema 2001

When Arwen arrives, the reverse movement of the camera stops, and we draw back in on the two, ending up with a renewed mise-en-scne: it no longer is a family matter we now have Aragorn, Sauron and Arwen in the frame. Here, Aragorns self-doubt becomes even clearer, as he totally identifies himself now with the failure Isildur, taking his place in the painting. Unfortunately, Sauron ominously floats between/above him and Arwen. In order for the two to come together, Sauron must be removed, the failure of Isildur must be undone, otherwise Arwens father will not let them get married. I think it is in passages like this unique to the medium where the film reveals its real beauty and depth.

Conclusion Whether a literary adaptation is the work of Morgoth or of genius in the end depends on ones personal likes and dislikes, and how much one is willing to let go of the book. Interestingly, no one complains about Mussorgsky, who adapted an art exhibition to a piano piece or Ravel adapting the same piano piece for orchestra. Quite the contrary this is art. The high degree of narrativity of film and seemingly low enunciative depth very often makes it seem flatter, less carefully told when compared to the book. At least if one does not take the time for a closer look and consider the aspects which are specific to the two media. Especially purists tend not to give film a chance by looking only for the book on screen instead of what the film as film has to offer. But the film can never replace the book or serve as a substitute. And neither can the book replace a film. Which I think, is a good thing.

(c) Tim Langer 2004, www.medienberater.de

The Balrog sequence1

The dark figure streaming with fire raced towards them. The orcs yelled and poured over the stone gangways. Then Boromir raised his horn and blew. Loud the challenge rang and bellowed, like the shout of many throats under the cavernous roof. Then the echoes died as suddenly as a flame blown out by a dark wind, and the enemy advanced again. Over the bridge! cried Gandalf, recalling his strength. Fly! This is a foe beyond any of you. I must hold the narrow way. Fly! Aragorn and Boromir did not heed the command, but still held their ground, side by side behind Gandalf at the far end of the bridge. The others halted just within the doorway at the halls end, and turned, unable to leave their leader to face the enemy alone. The Balrog reached the bridge. Gandalf stood in the middle of the span, leaning on the staff in his left hand, but in his other hand Glamdring gleamed, cold and white. His enemy halted again, facing him, and the shadow about it reached out like two vast wings. It raised the whip, and the thongs whined and cracked. Fire came from its nostrils. But Gandalf stood firm. You cannot pass, he said. The orcs stood still, and a dead silence fell. I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, Flame of Udn. Go back to the Shadow! You cannot pass. The Balrog made no answer. The fire in it seemed to die, but the darkness grew. It stepped forward slowly on to the bridge, and suddenly it drew itself up to a great height, and its wings were spread from wall to wall; but still Gandalf could be seen, glimmering in the gloom; he seemed small, and altogether alone: grey and bent, like a wizened tree before the onset of a storm. From out of the shadow a red sword leapt flaming. Glamdring glittered white in answer. There was a ringing clash and stab of white fire. The Balrog fell back and its sword flew up in molten fragments. The wizard swayed on the bridge, stepped back a pace, and then again stood still. You cannot pass! he said.

J.R.R. Tolkien: The Lord of the Rings, London 2001, S. 322.

(c) Tim Langer 2004, www.medienberater.de

You might also like

- Middle-Earth Fall of The NecromancerDocument76 pagesMiddle-Earth Fall of The Necromancerememari100% (1)

- History of Middle Earth (All 12 Vols.)Document3,509 pagesHistory of Middle Earth (All 12 Vols.)Miloš Radman96% (24)

- Louis Gianetti Understanding MoviesDocument6 pagesLouis Gianetti Understanding Moviesasslii_83No ratings yet

- Tom Gunning - M. The City Hounted by Demonic DesireDocument19 pagesTom Gunning - M. The City Hounted by Demonic DesiremadamehulotNo ratings yet

- The Issue of Fidelity in Film AdaptationsDocument7 pagesThe Issue of Fidelity in Film Adaptationssebastian_stratan67% (3)

- White Wolf Magazine 36Document84 pagesWhite Wolf Magazine 36DatGuy100% (4)

- The Lord of The Rings - IntroductionDocument1 pageThe Lord of The Rings - IntroductionblackpichaNo ratings yet

- Chronological Middle-Earth Reading ListDocument3 pagesChronological Middle-Earth Reading ListNick Senger100% (15)

- Film Novel JamesonDocument4 pagesFilm Novel JamesonEzequielNo ratings yet

- Mohn and Watts PainDocument9 pagesMohn and Watts PainYesNo ratings yet

- Le Desert Des TartaresDocument34 pagesLe Desert Des Tartaresmichel kowalevskyNo ratings yet

- Weird Tales Vol. 58 No. 4 No. 328 PDFDocument51 pagesWeird Tales Vol. 58 No. 4 No. 328 PDFMarcelo Vianna100% (1)

- Benjamin, W. The Crisis of The NovelDocument7 pagesBenjamin, W. The Crisis of The NovelPaula LombardiNo ratings yet

- Leo Bersani Forms of Being Cinema Aesthetics SubjectivityDocument188 pagesLeo Bersani Forms of Being Cinema Aesthetics SubjectivityXinyi DONGNo ratings yet

- Article by Andrei TarkovskyDocument3 pagesArticle by Andrei TarkovskyOscar FizNo ratings yet

- Kubrick Country: Houston: The Shock in The Book IsDocument4 pagesKubrick Country: Houston: The Shock in The Book Islollypop1234No ratings yet

- Heart of DarknessDocument2 pagesHeart of Darknessanushkasadhukhan3No ratings yet

- Turkish DelightDocument9 pagesTurkish Delightemm teeNo ratings yet

- Kubrick Country: Houston: The Shock in The Book IsDocument4 pagesKubrick Country: Houston: The Shock in The Book IsjordanallwoodNo ratings yet

- 25227-Texto Do Artigo-98899-1-10-20070302Document9 pages25227-Texto Do Artigo-98899-1-10-20070302Maral SereeterNo ratings yet

- Anor 21Document24 pagesAnor 21kaizokuoninaruNo ratings yet

- 101 Best Scenes Ever Written: A Romp Through Literature for Writers and ReadersFrom Everand101 Best Scenes Ever Written: A Romp Through Literature for Writers and ReadersNo ratings yet

- Parallel Lines That Meet: Narrative Crossovers in "Memento Mori" and MementoDocument4 pagesParallel Lines That Meet: Narrative Crossovers in "Memento Mori" and Mementopeter.struppNo ratings yet

- The Shape Shifting Storyteller in Lemony Snicket S A Series of Unfortunate EventsDocument22 pagesThe Shape Shifting Storyteller in Lemony Snicket S A Series of Unfortunate EventslilapdsNo ratings yet

- Conversation Between Andrei Tarkovsky and Tonino GuerraDocument7 pagesConversation Between Andrei Tarkovsky and Tonino GuerraMarcelo GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter The MovieDocument5 pagesHarry Potter The MovieAyesha Faraz bsengbt5No ratings yet

- Filming Dracula: Vampires, Genre, and CinematographyDocument9 pagesFilming Dracula: Vampires, Genre, and CinematographySouvik NahaNo ratings yet

- EndGame SlidesDocument17 pagesEndGame SlidesSayed Taimoor Ali Shah0% (1)

- Elements of Fiction Writing - DescriptionDocument115 pagesElements of Fiction Writing - DescriptionAzhar AhmadNo ratings yet

- 10 Nostromo, Panoramic, All-Inclusive Authorial NarrativeDocument30 pages10 Nostromo, Panoramic, All-Inclusive Authorial NarrativeBartłomiej OlszewskiNo ratings yet

- Bram Stoker "Dracula's Guest"Document3 pagesBram Stoker "Dracula's Guest"Антон ЮхимчукNo ratings yet

- Mark Le Fanu On EditingDocument10 pagesMark Le Fanu On EditingVladimir NabokovNo ratings yet

- Lord of The Rings PHD ThesisDocument4 pagesLord of The Rings PHD Thesisvaivuggld100% (2)

- 7 - Heart of DarknessDocument5 pages7 - Heart of DarknessLena100% (1)

- Pardon PDFDocument21 pagesPardon PDFredcloud111No ratings yet

- Esharp Is An International Online Journal For Postgraduate Research in The ArtsDocument18 pagesEsharp Is An International Online Journal For Postgraduate Research in The ArtsXander ClockNo ratings yet

- Lord of The Rings Bachelor ThesisDocument4 pagesLord of The Rings Bachelor Thesisbspq3gma100% (3)

- The Hound of The Baskervilles Revisited Adaptation in ContextDocument17 pagesThe Hound of The Baskervilles Revisited Adaptation in ContextSithusha SNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Lower DepthsDocument2 pagesAn Analysis of Lower DepthsNadine EsternonNo ratings yet

- Thomas Hardy and Cinematographic FormDocument10 pagesThomas Hardy and Cinematographic FormPaul MathewNo ratings yet

- Setting and Description in Horror Fiction Extended Short Story WorkshopDocument6 pagesSetting and Description in Horror Fiction Extended Short Story WorkshopMinaEmadNo ratings yet

- A Phuulish FellowDocument13 pagesA Phuulish FellowStrannik RuskiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics For Lord of The RingsDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Topics For Lord of The Ringskgtsnhrhf100% (1)

- League of Extraordinary Gentlemen - Century 1910 AnnocommentationsDocument43 pagesLeague of Extraordinary Gentlemen - Century 1910 AnnocommentationsTomasHamNo ratings yet

- Voice and Narration in Postmodern DramaDocument15 pagesVoice and Narration in Postmodern DramaaaeeNo ratings yet

- Analysis FileDocument6 pagesAnalysis FileKarina SavinovaNo ratings yet

- ABC ArriettaDocument5 pagesABC ArriettaVale AlfaroNo ratings yet

- Tolkien in the Twenty-First Century: The Meaning of Middle-Earth TodayFrom EverandTolkien in the Twenty-First Century: The Meaning of Middle-Earth TodayNo ratings yet

- 阻变存储器材料与器件 2014th Edition 潘峰 陈超 full chapter download PDFDocument57 pages阻变存储器材料与器件 2014th Edition 潘峰 陈超 full chapter download PDFnanbasinian100% (3)

- (Meridian - Crossing Aesthetics) Maurice Blanchot, Charlotte Mandell - The Work of Fire-Stanford University Press (1995)Document356 pages(Meridian - Crossing Aesthetics) Maurice Blanchot, Charlotte Mandell - The Work of Fire-Stanford University Press (1995)Andrei GabrielNo ratings yet

- The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy Novellas 2016: The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy Novellas, #2From EverandThe Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy Novellas 2016: The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy Novellas, #2Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Digressions On A Scanner Darkly (Kipple 31)Document11 pagesDigressions On A Scanner Darkly (Kipple 31)Frank BertrandNo ratings yet

- Narrative and Casablanca GOL 2017Document26 pagesNarrative and Casablanca GOL 2017gftuNo ratings yet

- Double Visions, Double Fictions - The Doppelgänger in Japanese Film and LiteratureDocument262 pagesDouble Visions, Double Fictions - The Doppelgänger in Japanese Film and Literaturethiago marangonNo ratings yet

- A Note On Beren and Luthien S Disguise PDFDocument5 pagesA Note On Beren and Luthien S Disguise PDFeuclides21No ratings yet

- 21st Century LifetimeDocument3 pages21st Century LifetimeKahleeya Mang-oy QuanNo ratings yet

- The Witcher - Group 8Document22 pagesThe Witcher - Group 8João SantosNo ratings yet

- PDF of The Shadow Throne Takhta Bayangan Jennifer A Nielsen Full Chapter EbookDocument69 pagesPDF of The Shadow Throne Takhta Bayangan Jennifer A Nielsen Full Chapter Ebookgwandifezaan42100% (4)

- Polin, Greg - StalkerDocument21 pagesPolin, Greg - StalkerDavid A. Cruz CalderónNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Fellowship of The RingDocument4 pagesThesis Statement For Fellowship of The Ringgowlijxff100% (2)

- Tolkien S Rewritings From The Battle ofDocument56 pagesTolkien S Rewritings From The Battle ofJorge RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Years of The LampsDocument38 pagesYears of The LampsJonathan Ivor CoetzerNo ratings yet

- Middle-Earth - Tale of YearsDocument6 pagesMiddle-Earth - Tale of YearsErszebethNo ratings yet

- Epilogue GaladrielDocument2 pagesEpilogue GaladrielLady Jehann NaragNo ratings yet

- Tolkien 144Document2 pagesTolkien 144SpiderhNo ratings yet

- J.R.R. Tolkien - Middle-Earth Glossary (v2.1b)Document421 pagesJ.R.R. Tolkien - Middle-Earth Glossary (v2.1b)emineNo ratings yet

- History of Arda (Wikipedia)Document14 pagesHistory of Arda (Wikipedia)Fabien WeissgerberNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Population of Eriador and GondorDocument12 pagesIndigenous Population of Eriador and GondorFabien WeissgerberNo ratings yet

- Galadriel MonologueDocument1 pageGaladriel MonologueChristian WD TanNo ratings yet

- Isildur 01-03Document72 pagesIsildur 01-03Eric DubourgNo ratings yet

- LotR SBG Scenario 3-4Document1 pageLotR SBG Scenario 3-4Harold EdenNo ratings yet

- Fellowship of The BananaDocument55 pagesFellowship of The BananaEvan Leonardo AshNo ratings yet

- GuidetoMiddleEarth1 5Document43 pagesGuidetoMiddleEarth1 5JackNo ratings yet

- Armies of EriadorDocument39 pagesArmies of EriadorGiorgio BriozzoNo ratings yet

- Ormod2 02Document106 pagesOrmod2 02valiataNo ratings yet

- Lotr - Extras - Battle Companies - New Characters For The Second AgeDocument8 pagesLotr - Extras - Battle Companies - New Characters For The Second AgeRon Van 't VeerNo ratings yet

- List of LOTR Missions PDFDocument32 pagesList of LOTR Missions PDFsilenceindigoNo ratings yet

- The Silmarillion (Document8 pagesThe Silmarillion (Dharmesh patelNo ratings yet

- Middle EarthDocument32 pagesMiddle Earthbrkica2011100% (1)

- Ea d20 3.5 Races and Cultures 20120804lDocument123 pagesEa d20 3.5 Races and Cultures 20120804lJohn Strickler100% (1)

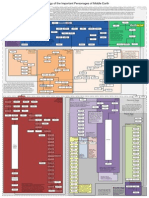

- Genealogy of The Important Personages of Middle Earth: Valian AgeDocument1 pageGenealogy of The Important Personages of Middle Earth: Valian AgelarskennedyNo ratings yet

- Last Alliance of Elves and MenDocument3 pagesLast Alliance of Elves and MenHenry MarshallNo ratings yet

- IsildurDocument213 pagesIsildurNuma BuchsNo ratings yet

- LOTR LCG Glossary Jun 14Document8 pagesLOTR LCG Glossary Jun 14ZeeallNo ratings yet

- Something in The WaterDocument55 pagesSomething in The WaterSue BridgwaterNo ratings yet