Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3.lisa Van Eyndhoven Knowledge Attitudes and Practice

3.lisa Van Eyndhoven Knowledge Attitudes and Practice

Uploaded by

Joel TelloCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Some Guiding Models of Voice Therapy For ChildrenDocument15 pagesSome Guiding Models of Voice Therapy For ChildrenCarlos ValenciaNo ratings yet

- The Late Talker: What to Do If Your Child Isn't Talking YetFrom EverandThe Late Talker: What to Do If Your Child Isn't Talking YetRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Effects of Creatine Supplementation On Renal Function - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesEffects of Creatine Supplementation On Renal Function - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisNaiara CaramuruNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics 2007 Reilly E1441 9Document11 pagesPediatrics 2007 Reilly E1441 9Putu Agus GrantikaNo ratings yet

- Debonis 2008Document17 pagesDebonis 2008waslacson17No ratings yet

- Pediatrics 2013Document9 pagesPediatrics 2013Bella AgiusselaNo ratings yet

- Otorhinolaryngology: Epidemiology of Communication Disorders in Childhood Phoniatric Clinical PracticeDocument6 pagesOtorhinolaryngology: Epidemiology of Communication Disorders in Childhood Phoniatric Clinical PracticeCarolina UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Speech Language Pathology-QuantiDocument12 pagesSpeech Language Pathology-QuantiHans BalingueNo ratings yet

- 9 - Done - Early Identification of Children With Speech and Language Disorder in Primary Health Care Centers Using A Paediatric Screening InstrumentDocument6 pages9 - Done - Early Identification of Children With Speech and Language Disorder in Primary Health Care Centers Using A Paediatric Screening InstrumentAndreia TavaresNo ratings yet

- Jenny Abanto, Georgios Tsakos, Saul Martins Paiva, Thiago S. Carvalho, Daniela P. Raggio and Marcelo BöneckerDocument10 pagesJenny Abanto, Georgios Tsakos, Saul Martins Paiva, Thiago S. Carvalho, Daniela P. Raggio and Marcelo BöneckerTasya AwaliyahNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Recruitment & Retention of Speech-Language Pathology 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: Recruitment & Retention of Speech-Language Pathology 1api-285442943No ratings yet

- Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics: Inger Lundeborg Hammarström, Rose-Marie Svensson & Karin MyrbergDocument15 pagesClinical Linguistics & Phonetics: Inger Lundeborg Hammarström, Rose-Marie Svensson & Karin MyrbergRafael AlvesNo ratings yet

- The Clinician's Guide To Treating Cleft Palate Speech 2nd EdDocument605 pagesThe Clinician's Guide To Treating Cleft Palate Speech 2nd EdAliaa Wameedh Ramzi AL-OmariNo ratings yet

- Are Needed Screening For Speech and Language Delay in Preschool Children: More AnswersDocument4 pagesAre Needed Screening For Speech and Language Delay in Preschool Children: More Answerswilsen_thaiNo ratings yet

- Ebd12r PDFDocument8 pagesEbd12r PDFVera Dyah SaputriNo ratings yet

- Latetalkers: Why The Wait-And-See Approach Is OutdatedDocument17 pagesLatetalkers: Why The Wait-And-See Approach Is OutdatedGrethell UrcielNo ratings yet

- 2007 Trastornos de La Comunicación Prevalencia yDocument10 pages2007 Trastornos de La Comunicación Prevalencia ytoril281bNo ratings yet

- Orofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtDocument8 pagesOrofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtMario Ruiz RuizNo ratings yet

- ScreeningDocument26 pagesScreeningLuiza BragaNo ratings yet

- Dorothy V.M. Bishop-David McDonald-2009Document16 pagesDorothy V.M. Bishop-David McDonald-2009Inma MéndezNo ratings yet

- 10.1055@s 0039 1677758Document2 pages10.1055@s 0039 1677758Verónica Gómez LópezNo ratings yet

- What OtolarDocument7 pagesWhat OtolarGiePramaNo ratings yet

- Comparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaresDocument6 pagesComparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaressdanobeitiaNo ratings yet

- J Jfludis 2021 105843Document21 pagesJ Jfludis 2021 105843ANDREA MIRANDA MEZA GARNICANo ratings yet

- Jaber 2011Document6 pagesJaber 2011Alvaro LaraNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Autis PDFDocument7 pagesOral Hygiene Autis PDFNoviyana Idrus DgmapatoNo ratings yet

- Summer 2016 Research PaperDocument19 pagesSummer 2016 Research Paperapi-317265239No ratings yet

- Factores Determinantes en El Desarrollo de Habilidades Auditivas en Ninos HipoacusicosDocument7 pagesFactores Determinantes en El Desarrollo de Habilidades Auditivas en Ninos HipoacusicosRocío AcostaNo ratings yet

- Module 2A Introduction To Motor Based Assessment HandoutDocument20 pagesModule 2A Introduction To Motor Based Assessment HandoutJohanna Steffie Arun KumarNo ratings yet

- Training Adults and Children With An Autism Spectrum Disorder To Be Compliant With A Clinical Dental Assessment Using A TEACCH-Based ApproachDocument10 pagesTraining Adults and Children With An Autism Spectrum Disorder To Be Compliant With A Clinical Dental Assessment Using A TEACCH-Based ApproachSpecial CareNo ratings yet

- A Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Disorders in Children With Repaired Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate in Hospital Universitisains MalaysiaDocument9 pagesA Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Disorders in Children With Repaired Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate in Hospital Universitisains MalaysiaSaera Hafiz NikitaNo ratings yet

- 2016, Oliveira Et Al, PEED, Validation Brasilian Version The Voice Disability Coping Questionnaire, J Voice Art TeseDocument9 pages2016, Oliveira Et Al, PEED, Validation Brasilian Version The Voice Disability Coping Questionnaire, J Voice Art TeseCarol PaesNo ratings yet

- When Will He Talk? An Evidence-Based Tutorial For Measuring Progress Toward Use of Spoken Words in Preverbal Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument18 pagesWhen Will He Talk? An Evidence-Based Tutorial For Measuring Progress Toward Use of Spoken Words in Preverbal Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderPaulina Guerra Santa MaríaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Article 2817Document7 pages2021 Article 2817EVAN GUSTIANSYAHNo ratings yet

- Clear As MudDocument6 pagesClear As MudLivia Almeida RamalhoNo ratings yet

- Dr. Jennifer Marshall Dr. Barbara Sheller Dr. Brian J. Williams Dr. Lloyd Manci Dr. Charles CowanDocument28 pagesDr. Jennifer Marshall Dr. Barbara Sheller Dr. Brian J. Williams Dr. Lloyd Manci Dr. Charles CowanYogesh KumarNo ratings yet

- CDH 4550barasuol05Document5 pagesCDH 4550barasuol05Deepakrajkc DeepuNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Oral Habits Among Health Care ProfessionalsDocument8 pagesAssessment of Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Oral Habits Among Health Care ProfessionalsKrishna KadamNo ratings yet

- Parents and Children TogetherDocument21 pagesParents and Children TogetherDanica JerotijevicNo ratings yet

- Delayed Referral in Children With Speech and Language Disorders For Rehabilitation ServicesDocument6 pagesDelayed Referral in Children With Speech and Language Disorders For Rehabilitation ServicesubayyumrNo ratings yet

- 2008 Mashima Overview of Telehealth Activities inDocument17 pages2008 Mashima Overview of Telehealth Activities inLucia CavasNo ratings yet

- Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesDocument8 pagesOral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesJuliana MoroNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Sentence Recall and Past Tense Measures For Identifying Children 'S Language ImpairmentsDocument17 pagesDiagnostic Accuracy of Sentence Recall and Past Tense Measures For Identifying Children 'S Language Impairmentsmaham mehmoodNo ratings yet

- Cochrane: LibraryDocument3 pagesCochrane: LibraryApriansyah Arfandy AzisNo ratings yet

- Communication Disorders Prevalence and Comorbid Intellectual Disability, Autism, and Emotiona-Behavioral DisordersDocument9 pagesCommunication Disorders Prevalence and Comorbid Intellectual Disability, Autism, and Emotiona-Behavioral DisordersLídia YoshiharaNo ratings yet

- Uoi 142 FDocument9 pagesUoi 142 FbkprosthoNo ratings yet

- Speech Delay in Toddlers Are They Only Late TalkersDocument8 pagesSpeech Delay in Toddlers Are They Only Late TalkersDini Sefi Zamira HarahapNo ratings yet

- 7 - Shriberg 2017 Estimates of The Prevalence of Speech and Motor Speech Disorders in Persons With Complex Neurodevelopmental DisordersDocument31 pages7 - Shriberg 2017 Estimates of The Prevalence of Speech and Motor Speech Disorders in Persons With Complex Neurodevelopmental DisordersJanieri BrazNo ratings yet

- Speech-Language Pathologists and Prosody Clinical Practices andDocument15 pagesSpeech-Language Pathologists and Prosody Clinical Practices andDigilindaNo ratings yet

- Dental Caries Status in Autistic Children: A Meta Analysis: Yujian Zhang Ling Lin Jianbo Liu Ling Shi Jianping LuDocument9 pagesDental Caries Status in Autistic Children: A Meta Analysis: Yujian Zhang Ling Lin Jianbo Liu Ling Shi Jianping Luzsazsa nissaNo ratings yet

- Teste de Rastreamento de Alterações de Fala para CriançasDocument6 pagesTeste de Rastreamento de Alterações de Fala para CriançassandrmrNo ratings yet

- Organization of The Referral and Counter-Referral System in A Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology Clinic-SchoolDocument6 pagesOrganization of The Referral and Counter-Referral System in A Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology Clinic-SchoolCarolina UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Oral HealthDocument50 pagesOral HealthJelena JacimovicNo ratings yet

- 9146-Article Text-36113-4-10-20221215Document6 pages9146-Article Text-36113-4-10-20221215Dinda Tryana SembiringNo ratings yet

- Thaut1984 AutismoDocument7 pagesThaut1984 AutismoMax MonteroNo ratings yet

- Prevalence, Severity and Associated Factors of Dental Caries in 3-6 Year Old Children - A Cross Sectional StudyDocument7 pagesPrevalence, Severity and Associated Factors of Dental Caries in 3-6 Year Old Children - A Cross Sectional StudysaravananspsNo ratings yet

- Final DNH PH Paper 1Document9 pagesFinal DNH PH Paper 1api-598493568No ratings yet

- Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific ReseqrchDocument14 pagesMinistry of Higher Education and Scientific ReseqrchkhawlabedraNo ratings yet

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder HandoutDocument2 pagesFetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Handoutapi-753995548No ratings yet

- Early Language Processing EfficiencyDocument18 pagesEarly Language Processing Efficiencydesimaulia upgrisNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment of Communication DisordersFrom EverandClinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment of Communication DisordersNo ratings yet

- 6.visconti AnkyloglossiaDocument11 pages6.visconti AnkyloglossiaJoel TelloNo ratings yet

- 1.fundagul Rapid Maxillary ExpansionDocument6 pages1.fundagul Rapid Maxillary ExpansionJoel TelloNo ratings yet

- 2.garima Speech EvaluationDocument5 pages2.garima Speech EvaluationJoel TelloNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Caries and Iron Deficiency Anaemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesEarly Childhood Caries and Iron Deficiency Anaemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisJoel TelloNo ratings yet

- Step by Step Guide To Critiquing Research Part 2Document7 pagesStep by Step Guide To Critiquing Research Part 2michael ndlovuNo ratings yet

- L&D ScriptDocument5 pagesL&D ScriptNishtha RahejaNo ratings yet

- Thesis 2021Document2 pagesThesis 2021abikeerthuNo ratings yet

- TFN Chapter 2Document97 pagesTFN Chapter 2mx odd100% (1)

- Mandatory Public Disclosure 1Document4 pagesMandatory Public Disclosure 1Manikanta SatishNo ratings yet

- SKILL: Oropharyngeal and Nasopharyngeal SuctioningDocument3 pagesSKILL: Oropharyngeal and Nasopharyngeal SuctioningCherry Rose Arce SamsonNo ratings yet

- OBSTETRICS AND GYNAECOLOGY CollectionDocument12 pagesOBSTETRICS AND GYNAECOLOGY CollectionAhmad Syahmi YZNo ratings yet

- OPT EP Kimber Student Insurance BrochureDocument20 pagesOPT EP Kimber Student Insurance BrochureKanakamedala Sai Rithvik ee18b051No ratings yet

- Summary Evaluation SetDocument161 pagesSummary Evaluation SetDavide VencoNo ratings yet

- NEP Syllabus PG YogaDocument30 pagesNEP Syllabus PG YogajaindynikeNo ratings yet

- Penilaian IlmiahDocument12 pagesPenilaian IlmiahJoko Purnomo HNo ratings yet

- Tench Facnav Letter Jan22Document1 pageTench Facnav Letter Jan22api-371944008No ratings yet

- Worksheet - Reliability, Validity, and NormsDocument3 pagesWorksheet - Reliability, Validity, and NormsRHIZZA MAE BONGHANOY HITOSISNo ratings yet

- Quim. Nova,: Callistemon Viminalis PolandiiDocument5 pagesQuim. Nova,: Callistemon Viminalis PolandiiArchana JoshiNo ratings yet

- 2019 - 04 - 22 - The Historic Judgment of The Madras High Court Madurai Bench Which Banned Intersex Sex-Selective Surgeries in Tamil Nadu State of IndiaDocument29 pages2019 - 04 - 22 - The Historic Judgment of The Madras High Court Madurai Bench Which Banned Intersex Sex-Selective Surgeries in Tamil Nadu State of IndiaIntersex AsiaNo ratings yet

- Radiation Safety SOP: Scope/PurposeDocument4 pagesRadiation Safety SOP: Scope/Purposezen AlkaffNo ratings yet

- Church, Dawson - The Heart of HealingDocument316 pagesChurch, Dawson - The Heart of HealingRenato CamarãoNo ratings yet

- Dignity in Death and Dying: Joyce D. Cajigal, RNDocument14 pagesDignity in Death and Dying: Joyce D. Cajigal, RNWendell Gian GolezNo ratings yet

- Metabolism Clinical and ExperimentalDocument4 pagesMetabolism Clinical and ExperimentalusingwebNo ratings yet

- Administration and Management Skills Needed by Physical Therapist Graduates in 2010Document21 pagesAdministration and Management Skills Needed by Physical Therapist Graduates in 2010Vicente Agredo SNo ratings yet

- Role of Government in Health NotesDocument3 pagesRole of Government in Health NotesHarika CNo ratings yet

- Transkrip Tugas Percakapan Bahasa InggrisDocument3 pagesTranskrip Tugas Percakapan Bahasa InggrisZhincan 07No ratings yet

- DAFTAR OBAT LASA (Lampiran 4)Document3 pagesDAFTAR OBAT LASA (Lampiran 4)iid fitriaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Treatment of Venous UlcersDocument14 pagesGuidelines For The Treatment of Venous UlcerssorinmoroNo ratings yet

- Annexure I Crash Cart ArrangementDocument2 pagesAnnexure I Crash Cart ArrangementSnehal Sharma100% (1)

- Peripheral Retinal Degenerations: EditorDocument241 pagesPeripheral Retinal Degenerations: EditorFelipe AlarcónNo ratings yet

- Ultrasoundfor AURClin TerDocument8 pagesUltrasoundfor AURClin TerLyka MahrNo ratings yet

- Rigel 333 Instruction ManualDocument37 pagesRigel 333 Instruction ManualTerraTerro Welleh WellehNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Tips : FibrereducesrisksofDocument1 pageNutrition Tips : FibrereducesrisksofharzuNo ratings yet

3.lisa Van Eyndhoven Knowledge Attitudes and Practice

3.lisa Van Eyndhoven Knowledge Attitudes and Practice

Uploaded by

Joel TelloOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3.lisa Van Eyndhoven Knowledge Attitudes and Practice

3.lisa Van Eyndhoven Knowledge Attitudes and Practice

Uploaded by

Joel TelloCopyright:

Available Formats

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of

Pediatric Dentists Regarding Speech

Evaluation of Patients: Implications for

Dental Education

Lisa Van Eyndhoven, DDS, MS; Steven Chussid, DDS; Richard K. Yoon, DDS

Abstract: The aim of this cross-sectional study was to determine pediatric dentists’ attitudes about speech evaluation in the dental

setting and assess their knowledge of speech development and pathology. In October 2013, members of the American Academy

of Pediatric Dentistry were invited to participate in an electronic questionnaire. Categories of questions were demographics, atti-

tudes and conidence in speech pathology, and theoretical and practical knowledge of speech development and speech pathology.

Theoretical knowledge was assessed using questions about phonetics and speech milestones. Practical knowledge was determined

with three 30-second interview-style video clips. A total of 539 responses were received for a response rate of 10.4%. The major-

ity of respondents reported feeling that speech evaluation should be part of the pediatric dental visit (72.8%) and felt conident in

their ability to detect speech issues (73.2%). However, they did poorly on the theoretical knowledge questions (41.9%) as well

as the practical knowledge questions (8.5%). There was a statistically signiicant difference in theoretical score between gender

and type of occupation (p<0.05). This difference was not observed when examining practical knowledge. This study suggests that

although pediatric dentists are in an ideal position to aid in the detection of speech issues, they currently have insuficient training

and knowledge to do so.

Dr. Van Eyndhoven is an associate pediatric dentist in private practice, New York, NY, and former postdoctoral resident fellow,

Columbia University Medical Center; Dr. Chussid is Associate Professor of Dental Medicine and Chair, Section of Growth and

Development, Columbia University Medical Center; and Dr. Yoon is Associate Professor of Dental Medicine and Program Direc-

tor, Advanced Specialty Education in Pediatric Dentistry, Columbia University Medical Center. Direct correspondence to Dr.

Richard K. Yoon, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine, 630 W. 168th Street, New York, NY 10032; 212-305-1043;

rky1@cumc.columbia.edu.

Keywords: advanced dental education, graduate dental education, pediatric dentistry, speech, pathology, oral examination,

continuing education

Submitted for publication 1/23/15; accepted 5/12/15

A

ccording to the American Speech-Language- language pathologists (SLPs) work with physicians,

Hearing Association (ASHA), approxi- occupational therapists, and early childhood educa-

mately 17% of Americans suffer from a com- tors.4 However, there is currently little interaction

munication disorder, and about 7% of children have between SLPs and pediatric dentists.

speciic language impairment.1 Early identiication of Basic speech and language milestones are

speech disorders is important because they may prog- available in the Handbook of Pediatric Dentistry

ress to lifelong communicative impairments if left published by the American Academy of Pediatric

untreated. Often a precursor for learning disabilities, Dentistry (AAPD) although it is unclear how much

there is a concurrence between speech disorder and knowledge pediatric dentists have in this ield or have

autism, behavior disorders, and neurologic impair- received during their clinical training.5 Furthermore,

ments.2 Language issues can also lead to problems it is unclear how much speech and language training

with self-esteem and “maladaption of emotional and pediatric dentists receive in their specialty through

social reactions.”3 continuing education. Awareness of speech delay

According to ASHA, early speech and lan- and speech pathology can aid pediatric dentists in

guage intervention with expressive language and determining the best way to treat a child, not only

vocabulary issues has a positive effect.1 Although in treatment planning but also in behavior manage-

this connection suggests that early diagnosis is ben- ment.6 A irm understanding of the linguistic matu-

eicial to the child, most speech pathology is in fact rity of the child helps pediatric dentists adjust their

not recognized until school age. To aid in the early techniques to reduce miscommunication, which has

identiication of children with speech issues, speech been linked to misbehavior.7

November 2015 ■ Journal of Dental Education 1279

While pediatric dentists play a critical role in about the incorporation of speech evaluation in the

evaluation of the developing oral structures and the dental recall examination.

diagnosis of oral pathology in the young child and Theoretical knowledge was assessed with ques-

also rely heavily on communication to perform ade- tions about phonetics, speech and oral milestones

quate treatment, it is unclear what their role should be (e.g., drooling and swallowing), and speech therapy.

in the diagnosis, referral, and treatment of speech pa- These questions were derived from the AAPD hand-

thology. The aims of this cross-sectional study were book and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

therefore to 1) determine pediatric dentists’ attitudes Bright Futures guidelines.5,8

about training in speech and language pathology; 2) Practical knowledge was assessed with three

determine their attitudes regarding incorporation of 30-second interview-style video clips obtained from

speech evaluation in the routine dental examination; a video-sharing web-based server. The irst video

and 3) evaluate their knowledge of normal speech featured a three-year-old girl with apraxia (a speech

development and speech pathology. production disorder), the second a normally devel-

oping four-year-old girl, and the third a ten-year-old

boy with autism and social language impairment.

Methods Participants were asked whether the child would

beneit from a referral to an SLP and to identify any

All study procedures and waiver of consents speech issues if any. All videos and questions were

were approved by The Research Compliance and reviewed and veriied by a registered SLP on the

Administration System at Columbia University craniofacial team.

Medical Center, protocol number AAAL4850. The The respondents remained anonymous, and no

research team developed and beta tested a survey identifying information was obtained. Descriptive

instrument. Survey testing was accomplished with 12 statistical analysis was conducted using the Qualtrics

pediatric dentists (eight in clinical practice and four web-based survey and SPSS Statistics for Windows,

in academe) with various years of clinical experience. Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to gen-

The beta test was used to clarify and reine survey erate percentages, t-tests, ANOVA, and linear regres-

questions and eliminate unclear items. sion analysis. Statistical signiicance was set at 0.05.

In October 2013, 5,200 active non-retired

members of the AAPD who had graduated from a

postdoctoral program in the U.S. or abroad were in-

vited via email to participate in a 33-item electronic

Results

questionnaire hosted and administered by Qualtrics A total of 539 responses were received for a

Survey Software and Research Suite (Qualtrics, response rate of 10.4%. Approximately 50% of the

Provo, UT, USA). Questionnaire items contained respondents identiied themselves as female (N=278),

questions regarding demographics, attitudes and and the majority (75.7%, N=408) identiied as being

confidence in speech pathology, and theoretical white/Caucasian with the second most predominant

knowledge and practical knowledge of speech de- ethnic group being Asian (10.2%, N=55). Ages varied

velopment and speech pathology. from <30 years (5%), 30-40 years (38%), to 40-50

Demographic questions asked about respon- years (22%); the remaining respondents were above

dents’ gender, birth year, race/ethnicity, type of the age of 50. Approximately 40% had graduated

postdoctoral program attended, year of graduation from their postdoctoral program after 2005, and 53%

from program, diploma obtained, occupation, and graduated from a hospital-based program afiliated

training in speech pathology including participa- with a dental school. During their postdoctoral pro-

tion in a craniofacial team. Survey recipients were gram, 70% had participated in a craniofacial team.

asked how conident they felt in their training in The majority of the respondents (87.6%, N=472)

speech pathology and whether they felt conident reported their primary occupation as clinical practice,

in their ability to identify speech issues. Attitudes with the majority in practice in a private dental ofice

were determined by inquiring about the respondents’ (81.0%, N=437). Of the remaining respondents, 51%

interest in attending continuing education courses in identiied themselves as dental educators (N=51);

speech pathology, how strongly they agreed with the only one reported being a dental researcher.

incorporation of speech pathology in dental training Approximately 73% of the responding pedi-

(predoctoral and postdoctoral), and how they felt atric dentists agreed that speech evaluation should

1280 Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 79, Number 11

be part of the routine pediatric dental examination, education course led to an increase in theoretical and

and 73.2% said they felt conident in their ability to practical knowledge, but this increase was not statisti-

identify speech delays in the clinical pediatric dental cally signiicant (Figure 3). There was also no sta-

setting. While 95.4% reported feeling that training tistically signiicant difference in one-way ANOVA

in speech and language development was important analysis of the effect of quantity of training in speech

during their postdoctoral program, only 41.2% felt pathology on theoretical and practical knowledge.

their training suficiently prepared them to identify

common speech pathologies. In addition, 45.1% said

they were likely to attend a continuing education Discussion

course in speech pathology (Table 1).

The average score of correctly answered theo- Speech is produced when sounds are formed

retical questions was 41.9%, and less than 1% of the by the vocal chords and are altered by the movement

respondents correctly identiied all speech and oral of the lips, tongue, and teeth. Speech therapists iden-

milestones. Only 8.5% provided correct referrals to tify problems with this process and diagnose delays

an SLP to all three children in the videos, while only and pathologies such as apraxia, dysarthria, and

2.8% correctly identiied speech issues (if any) in the articulation disorders. They use various techniques

three children (Table 1). to overcome these issues and also collaborate with

There was a statistically signiicant difference other health care professionals such as pediatricians

in theoretical score between type of occupation and and physicians who specialize in ear, nose, and throat

gender. The average theoretical score for clinical pe- as well as occupational therapists and early childhood

diatric dentists was 4.08 (out of a possible 12), and the educators.

average theoretical score for pediatric dentists who Predy and Meintzer reviewed the role of speech

identiied themselves as dental educators/dental re- evaluation in the well-child visit with the pediatri-

searchers/other was 5.27 with a mean score difference cian/family physician in 1982.3 They described how

of 1.19 (p<0.05). This difference was not observed speech and language development is often a precursor

when comparing practical knowledge scores (Figure for learning disabilities and that most speech pathol-

1). The average theoretical score for female pediatric ogy is not recognized until school age. Since such

dentists was 4.57 (out of a possible 12), and the aver- issues can lead to problems with self-esteem and

age theoretical score for male pediatric dentists was “maladaption of emotional and social reactions” and

3.95 with a mean score difference of 0.62 (p<0.05). since the family physician is often the irst person

This difference was not observed when comparing consulted about speech issues, they argued that there

practical knowledge scores (Figure 2). should be greater awareness of speech evaluation on

There was no statistically signiicant correla- the part of the family physician.

tion between theoretical or practical score with regard The meta-analysis done by Law et al. con-

to race or ethnicity, type of postdoctoral program, or cluded that there was a positive effect of speech and

graduation year. Exposure to speech pathology train- language therapy interventions for children with ex-

ing in either postdoctoral training or via a continuing pressive phonological and vocabulary issues.2 They

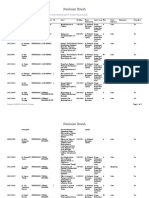

Table 1. Descriptive data for attitudes and knowledge of participating pediatric dentists

Number (Total Respondents) Percentage

Attitudes

Likely to attend a continuing education course in speech pathology 243 (539) 45.1%

Agreed that training in speech pathology should be part of postdoctoral training 501 (525) 95.4%

Theoretical knowledge

Average of correctly answered theoretical questions 226 (539) 41.9%

Participants who correctly identified all speech and oral milestones 3 (539) 0.6%

Practical knowledge

Participants who provided correct referrals to children from the videos 46 (539) 8.5%

Participants who correctly identified any speech issues in children from the videos 15 (539) 2.8%

November 2015 ■ Journal of Dental Education 1281

Figure 1. Mean theoretical and practical scores of participating clinical pediatric dentists in comparison with dental

educators/researchers/other

Note: Scores on both theoretical and practical questions are out of a possible 12.

*Mean score difference=-1.19 (p<0.05)

Figure 2. Mean theoretical and practical scores of participating female pediatric dentists in comparison with male

pediatric dentists

Note: Scores on both theoretical and practical questions are out of a possible 12.

*Mean score difference=-0.62 (p<0.05)

1282 Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 79, Number 11

Figure 3. Mean theoretical and practical scores of participants with and without formal training in postdoctoral

program or continuing education courses

Note: Scores on both theoretical and practical questions are out of a possible 12. No statistically significant difference was found.

also described a concurrence between speech disor- duction.11,12 This connection suggests a larger role for

der and autism, behavior disorder, and neurologic the pediatric dentist in the detection of early speech

impairment. This relationship suggests that early pathology. Since pediatric dentists are involved in

diagnosis and treatment in certain circumstances treating young children and since communication is

would beneit the child. Lawrence and Bateman in essential for cooperation and effective treatment, they

their literature review described a 12-minute method are in a good position to help identify any delays.6

that would aid in early diagnosis and can be incor- Awareness of speech delay and speech pathol-

porated into any pediatric practice.4 ogy can aid pediatric dentists in determining the best

Dentists learn how the proper alignment of way to treat a child. For instance, Pinkham describes

teeth helps with the phonation. Disciplines such as how misbehavior is often linked to miscommu-

prosthodontics and orthodontics address these struc- nication.7 A better understanding of the linguistic

tural issues to help aid functional ones. Both Fawcus maturity of their patients will help pediatric dentists

and Hopkin described the effect of malocclusions determine the child’s behavior in a treatment setting,

and skeletal disharmony on speech development.9,10 allowing them to adjust their behavior management

Those studies promoted the role of the orthodontist techniques. Since pediatric dentists have such a direct

through the use of interceptive and traditional ortho- impact on the developing dentition and also play such

dontics in combination with speech therapy to guide a pivotal role in the overall development of the child,

the speech development of the child. they should be more aware of language milestones

Pediatric dentists are trained in how the oral and language disorders.

structures of a child develop. They are aware in how Though most pediatric dentists (73.2%) in our

they can affect these structures. For instance, the early study said they were conident in their ability to diag-

extraction of primary incisors can affect speech pro- nose speech issues, on average they did not perform

November 2015 ■ Journal of Dental Education 1283

well on either the theoretical or the practical speech to view the videos and therefore unable to answer the

pathology questions. Pediatric dentists performed the questions pertaining to them. Though this problem

best on the section analyzing knowledge of speech further reduced the amount of usable data, the use of

therapy and oral milestones (such as drooling and embedded electronic media has the ability to enhance

swallowing) with an average score of 48.9%, while both education and evaluation.

they performed the worst on the section evaluating

knowledge of phonemes and phonetics (22.6%). It

was expected that they would perform well on the Conclusion

section of speech and language milestones since

those are listed in the AAPD handbook; however, Because pediatric dentists are in a good posi-

the average score was a 30.2% with only 13.1% of tion to detect early speech pathology, the aim of this

the sample scoring higher than 50%. study was to determine their attitudes about speech

There was no statistically significant cor- evaluation in the dental setting and assess their

relation between theoretical or practical score and knowledge of speech development and pathology.

ethnicity, type of postdoctoral program, graduation Although only 10.4% of the total sample (members

year, or exposure to speech pathology in continuing of the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry)

education, postdoctoral, or predoctoral courses. It participated in the survey, the results suggest that

appears that the pediatric dentists were unilaterally pediatric dentists have insuficient knowledge and

unprepared to detect speech issues, and their race/ training to evaluate their patients’ speech develop-

ethnicity, type of training they received, or amount ment and pathology. However, while the participants’

of clinical experience seemed to have no impact on performance on both the theoretical and practical

their ability to do so. evaluations was poor, the majority agreed that train-

There was a statistically signiicant difference ing in speech pathology is an important component

in theoretical score between gender and type of oc- of the education of the pediatric dentist. They also

cupation. The average theoretical score for clinical agreed that speech evaluation should be in the diag-

pediatric dentists was 4.08 (out of a possible 12), nostic scope of the pediatric dentist and should be a

and the average theoretical score for pediatric den- part of the dental examination.

tists who identiied themselves as dental educators/

dental researchers/other was 5.27, for a mean score Disclosure

difference of 1.19 (p<0.05). This difference was The authors reported no conlicts of interest.

not observed when comparing practical knowledge

scores (Figure 1). The average theoretical score for REFERENCES

female pediatric dentists was 4.57 (out of a possible 1. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Speech

12), and the average theoretical score for male pedi- language pathology: medical review guidelines—inci-

atric dentists was 3.95, for a mean score difference dence and prevalence of communication disorders and

hearing loss in children. 2008. At: www.asha.org/upload-

of 0.62 (p<0.05). This difference was not observed

edFiles/SLP-Medical-Review-Guidelines.pdf. Accessed 4

when comparing practical knowledge scores (Figure Sept. 2014.

2). In general, participants with training in speech 2. Law J, Garrett Z, Nye C. Speech and language therapy in-

pathology either in postdoctoral education or continu- terventions for children with primary speech and language

ing education courses did better on both theoretical delay or disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003(3).

and practical portions although the difference was 3. Predy G, Meintzer J. Communication disorders in chil-

dren: the role of the family physician. Can Fam Physician

not statistically signiicant (Figure 3). 1982;28:981-4.

The limitations to this study were primarily the 4. Lawrence R, Bateman N. 12 minute consultation: an

small number of participants. With a 10.4% response evidence-based approach to the management of a child

rate, this study represents only a small proportion of with speech and language delay. Clin Otolaryngol

pediatric dentists in the United States. In addition, 2013;38(2):148-53.

5. Nowak AJ, Casamassimo PS. American Academy of

technical dificulties further limited the usable sample Pediatric Dentistry handbook of pediatric dentistry. 4th

size. The electronic questionnaire had both embed- ed. Chicago: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry,

ded video-sharing web-based clips and links to the 2011.

videos and due to limitations of various software 6. Shetty P. Speech and language delay in children: a review

programs, a large number of respondents were unable and the role of a pediatric dentist. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev

Dent 2012;30(2):103-8.

1284 Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 79, Number 11

7. Pinkham JR. Linguistic maturity as a determinant of child 11. Adewumi A, Horton C, Guelmann M, et al. Parental

patient behavior in the dental ofice. J Am Dent Assoc perception vs. professional assessment of speech changes

1977;94(4):708-12. following premature loss of maxillary primary incisors.

8. American Academy of Pediatrics. Bright futures tool Pediatr Dent 2012;34(4):295-9.

and resource kit. 2010. At: http://brightfutures.aap.org/ 12. Lamberghini F, Kaste L, Fadavi S, et al. An association

tool_and_resource_kit.html. Accessed 4 Sept. 2014. of premature loss of primary maxillary incisors with

9. Fawcus R. Dental problems in speech pathology. Proc R speech production of bilingual children. Pediatr Dent

Soc Med 1968;61(6):619-22. 2012;34(4):307-11.

10. Hopkin GB. Orthodontic aspects of the diagnosis and

management of speech defects in children. Proc R Soc

Med 1972;65(4):409-14.

November 2015 ■ Journal of Dental Education 1285

You might also like

- Some Guiding Models of Voice Therapy For ChildrenDocument15 pagesSome Guiding Models of Voice Therapy For ChildrenCarlos ValenciaNo ratings yet

- The Late Talker: What to Do If Your Child Isn't Talking YetFrom EverandThe Late Talker: What to Do If Your Child Isn't Talking YetRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Effects of Creatine Supplementation On Renal Function - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesEffects of Creatine Supplementation On Renal Function - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisNaiara CaramuruNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics 2007 Reilly E1441 9Document11 pagesPediatrics 2007 Reilly E1441 9Putu Agus GrantikaNo ratings yet

- Debonis 2008Document17 pagesDebonis 2008waslacson17No ratings yet

- Pediatrics 2013Document9 pagesPediatrics 2013Bella AgiusselaNo ratings yet

- Otorhinolaryngology: Epidemiology of Communication Disorders in Childhood Phoniatric Clinical PracticeDocument6 pagesOtorhinolaryngology: Epidemiology of Communication Disorders in Childhood Phoniatric Clinical PracticeCarolina UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Speech Language Pathology-QuantiDocument12 pagesSpeech Language Pathology-QuantiHans BalingueNo ratings yet

- 9 - Done - Early Identification of Children With Speech and Language Disorder in Primary Health Care Centers Using A Paediatric Screening InstrumentDocument6 pages9 - Done - Early Identification of Children With Speech and Language Disorder in Primary Health Care Centers Using A Paediatric Screening InstrumentAndreia TavaresNo ratings yet

- Jenny Abanto, Georgios Tsakos, Saul Martins Paiva, Thiago S. Carvalho, Daniela P. Raggio and Marcelo BöneckerDocument10 pagesJenny Abanto, Georgios Tsakos, Saul Martins Paiva, Thiago S. Carvalho, Daniela P. Raggio and Marcelo BöneckerTasya AwaliyahNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Recruitment & Retention of Speech-Language Pathology 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: Recruitment & Retention of Speech-Language Pathology 1api-285442943No ratings yet

- Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics: Inger Lundeborg Hammarström, Rose-Marie Svensson & Karin MyrbergDocument15 pagesClinical Linguistics & Phonetics: Inger Lundeborg Hammarström, Rose-Marie Svensson & Karin MyrbergRafael AlvesNo ratings yet

- The Clinician's Guide To Treating Cleft Palate Speech 2nd EdDocument605 pagesThe Clinician's Guide To Treating Cleft Palate Speech 2nd EdAliaa Wameedh Ramzi AL-OmariNo ratings yet

- Are Needed Screening For Speech and Language Delay in Preschool Children: More AnswersDocument4 pagesAre Needed Screening For Speech and Language Delay in Preschool Children: More Answerswilsen_thaiNo ratings yet

- Ebd12r PDFDocument8 pagesEbd12r PDFVera Dyah SaputriNo ratings yet

- Latetalkers: Why The Wait-And-See Approach Is OutdatedDocument17 pagesLatetalkers: Why The Wait-And-See Approach Is OutdatedGrethell UrcielNo ratings yet

- 2007 Trastornos de La Comunicación Prevalencia yDocument10 pages2007 Trastornos de La Comunicación Prevalencia ytoril281bNo ratings yet

- Orofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtDocument8 pagesOrofacial Dysfunction Nonnutritive Sucking Hab 2022 American Journal of OrtMario Ruiz RuizNo ratings yet

- ScreeningDocument26 pagesScreeningLuiza BragaNo ratings yet

- Dorothy V.M. Bishop-David McDonald-2009Document16 pagesDorothy V.M. Bishop-David McDonald-2009Inma MéndezNo ratings yet

- 10.1055@s 0039 1677758Document2 pages10.1055@s 0039 1677758Verónica Gómez LópezNo ratings yet

- What OtolarDocument7 pagesWhat OtolarGiePramaNo ratings yet

- Comparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaresDocument6 pagesComparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaressdanobeitiaNo ratings yet

- J Jfludis 2021 105843Document21 pagesJ Jfludis 2021 105843ANDREA MIRANDA MEZA GARNICANo ratings yet

- Jaber 2011Document6 pagesJaber 2011Alvaro LaraNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Autis PDFDocument7 pagesOral Hygiene Autis PDFNoviyana Idrus DgmapatoNo ratings yet

- Summer 2016 Research PaperDocument19 pagesSummer 2016 Research Paperapi-317265239No ratings yet

- Factores Determinantes en El Desarrollo de Habilidades Auditivas en Ninos HipoacusicosDocument7 pagesFactores Determinantes en El Desarrollo de Habilidades Auditivas en Ninos HipoacusicosRocío AcostaNo ratings yet

- Module 2A Introduction To Motor Based Assessment HandoutDocument20 pagesModule 2A Introduction To Motor Based Assessment HandoutJohanna Steffie Arun KumarNo ratings yet

- Training Adults and Children With An Autism Spectrum Disorder To Be Compliant With A Clinical Dental Assessment Using A TEACCH-Based ApproachDocument10 pagesTraining Adults and Children With An Autism Spectrum Disorder To Be Compliant With A Clinical Dental Assessment Using A TEACCH-Based ApproachSpecial CareNo ratings yet

- A Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Disorders in Children With Repaired Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate in Hospital Universitisains MalaysiaDocument9 pagesA Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Disorders in Children With Repaired Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate in Hospital Universitisains MalaysiaSaera Hafiz NikitaNo ratings yet

- 2016, Oliveira Et Al, PEED, Validation Brasilian Version The Voice Disability Coping Questionnaire, J Voice Art TeseDocument9 pages2016, Oliveira Et Al, PEED, Validation Brasilian Version The Voice Disability Coping Questionnaire, J Voice Art TeseCarol PaesNo ratings yet

- When Will He Talk? An Evidence-Based Tutorial For Measuring Progress Toward Use of Spoken Words in Preverbal Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument18 pagesWhen Will He Talk? An Evidence-Based Tutorial For Measuring Progress Toward Use of Spoken Words in Preverbal Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderPaulina Guerra Santa MaríaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Article 2817Document7 pages2021 Article 2817EVAN GUSTIANSYAHNo ratings yet

- Clear As MudDocument6 pagesClear As MudLivia Almeida RamalhoNo ratings yet

- Dr. Jennifer Marshall Dr. Barbara Sheller Dr. Brian J. Williams Dr. Lloyd Manci Dr. Charles CowanDocument28 pagesDr. Jennifer Marshall Dr. Barbara Sheller Dr. Brian J. Williams Dr. Lloyd Manci Dr. Charles CowanYogesh KumarNo ratings yet

- CDH 4550barasuol05Document5 pagesCDH 4550barasuol05Deepakrajkc DeepuNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Oral Habits Among Health Care ProfessionalsDocument8 pagesAssessment of Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Oral Habits Among Health Care ProfessionalsKrishna KadamNo ratings yet

- Parents and Children TogetherDocument21 pagesParents and Children TogetherDanica JerotijevicNo ratings yet

- Delayed Referral in Children With Speech and Language Disorders For Rehabilitation ServicesDocument6 pagesDelayed Referral in Children With Speech and Language Disorders For Rehabilitation ServicesubayyumrNo ratings yet

- 2008 Mashima Overview of Telehealth Activities inDocument17 pages2008 Mashima Overview of Telehealth Activities inLucia CavasNo ratings yet

- Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesDocument8 pagesOral Health-Related Quality of Life of Schoolchildren: Impact of Clinical and Psychosocial VariablesJuliana MoroNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Sentence Recall and Past Tense Measures For Identifying Children 'S Language ImpairmentsDocument17 pagesDiagnostic Accuracy of Sentence Recall and Past Tense Measures For Identifying Children 'S Language Impairmentsmaham mehmoodNo ratings yet

- Cochrane: LibraryDocument3 pagesCochrane: LibraryApriansyah Arfandy AzisNo ratings yet

- Communication Disorders Prevalence and Comorbid Intellectual Disability, Autism, and Emotiona-Behavioral DisordersDocument9 pagesCommunication Disorders Prevalence and Comorbid Intellectual Disability, Autism, and Emotiona-Behavioral DisordersLídia YoshiharaNo ratings yet

- Uoi 142 FDocument9 pagesUoi 142 FbkprosthoNo ratings yet

- Speech Delay in Toddlers Are They Only Late TalkersDocument8 pagesSpeech Delay in Toddlers Are They Only Late TalkersDini Sefi Zamira HarahapNo ratings yet

- 7 - Shriberg 2017 Estimates of The Prevalence of Speech and Motor Speech Disorders in Persons With Complex Neurodevelopmental DisordersDocument31 pages7 - Shriberg 2017 Estimates of The Prevalence of Speech and Motor Speech Disorders in Persons With Complex Neurodevelopmental DisordersJanieri BrazNo ratings yet

- Speech-Language Pathologists and Prosody Clinical Practices andDocument15 pagesSpeech-Language Pathologists and Prosody Clinical Practices andDigilindaNo ratings yet

- Dental Caries Status in Autistic Children: A Meta Analysis: Yujian Zhang Ling Lin Jianbo Liu Ling Shi Jianping LuDocument9 pagesDental Caries Status in Autistic Children: A Meta Analysis: Yujian Zhang Ling Lin Jianbo Liu Ling Shi Jianping Luzsazsa nissaNo ratings yet

- Teste de Rastreamento de Alterações de Fala para CriançasDocument6 pagesTeste de Rastreamento de Alterações de Fala para CriançassandrmrNo ratings yet

- Organization of The Referral and Counter-Referral System in A Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology Clinic-SchoolDocument6 pagesOrganization of The Referral and Counter-Referral System in A Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology Clinic-SchoolCarolina UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Oral HealthDocument50 pagesOral HealthJelena JacimovicNo ratings yet

- 9146-Article Text-36113-4-10-20221215Document6 pages9146-Article Text-36113-4-10-20221215Dinda Tryana SembiringNo ratings yet

- Thaut1984 AutismoDocument7 pagesThaut1984 AutismoMax MonteroNo ratings yet

- Prevalence, Severity and Associated Factors of Dental Caries in 3-6 Year Old Children - A Cross Sectional StudyDocument7 pagesPrevalence, Severity and Associated Factors of Dental Caries in 3-6 Year Old Children - A Cross Sectional StudysaravananspsNo ratings yet

- Final DNH PH Paper 1Document9 pagesFinal DNH PH Paper 1api-598493568No ratings yet

- Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific ReseqrchDocument14 pagesMinistry of Higher Education and Scientific ReseqrchkhawlabedraNo ratings yet

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder HandoutDocument2 pagesFetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Handoutapi-753995548No ratings yet

- Early Language Processing EfficiencyDocument18 pagesEarly Language Processing Efficiencydesimaulia upgrisNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment of Communication DisordersFrom EverandClinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment of Communication DisordersNo ratings yet

- 6.visconti AnkyloglossiaDocument11 pages6.visconti AnkyloglossiaJoel TelloNo ratings yet

- 1.fundagul Rapid Maxillary ExpansionDocument6 pages1.fundagul Rapid Maxillary ExpansionJoel TelloNo ratings yet

- 2.garima Speech EvaluationDocument5 pages2.garima Speech EvaluationJoel TelloNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Caries and Iron Deficiency Anaemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesEarly Childhood Caries and Iron Deficiency Anaemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisJoel TelloNo ratings yet

- Step by Step Guide To Critiquing Research Part 2Document7 pagesStep by Step Guide To Critiquing Research Part 2michael ndlovuNo ratings yet

- L&D ScriptDocument5 pagesL&D ScriptNishtha RahejaNo ratings yet

- Thesis 2021Document2 pagesThesis 2021abikeerthuNo ratings yet

- TFN Chapter 2Document97 pagesTFN Chapter 2mx odd100% (1)

- Mandatory Public Disclosure 1Document4 pagesMandatory Public Disclosure 1Manikanta SatishNo ratings yet

- SKILL: Oropharyngeal and Nasopharyngeal SuctioningDocument3 pagesSKILL: Oropharyngeal and Nasopharyngeal SuctioningCherry Rose Arce SamsonNo ratings yet

- OBSTETRICS AND GYNAECOLOGY CollectionDocument12 pagesOBSTETRICS AND GYNAECOLOGY CollectionAhmad Syahmi YZNo ratings yet

- OPT EP Kimber Student Insurance BrochureDocument20 pagesOPT EP Kimber Student Insurance BrochureKanakamedala Sai Rithvik ee18b051No ratings yet

- Summary Evaluation SetDocument161 pagesSummary Evaluation SetDavide VencoNo ratings yet

- NEP Syllabus PG YogaDocument30 pagesNEP Syllabus PG YogajaindynikeNo ratings yet

- Penilaian IlmiahDocument12 pagesPenilaian IlmiahJoko Purnomo HNo ratings yet

- Tench Facnav Letter Jan22Document1 pageTench Facnav Letter Jan22api-371944008No ratings yet

- Worksheet - Reliability, Validity, and NormsDocument3 pagesWorksheet - Reliability, Validity, and NormsRHIZZA MAE BONGHANOY HITOSISNo ratings yet

- Quim. Nova,: Callistemon Viminalis PolandiiDocument5 pagesQuim. Nova,: Callistemon Viminalis PolandiiArchana JoshiNo ratings yet

- 2019 - 04 - 22 - The Historic Judgment of The Madras High Court Madurai Bench Which Banned Intersex Sex-Selective Surgeries in Tamil Nadu State of IndiaDocument29 pages2019 - 04 - 22 - The Historic Judgment of The Madras High Court Madurai Bench Which Banned Intersex Sex-Selective Surgeries in Tamil Nadu State of IndiaIntersex AsiaNo ratings yet

- Radiation Safety SOP: Scope/PurposeDocument4 pagesRadiation Safety SOP: Scope/Purposezen AlkaffNo ratings yet

- Church, Dawson - The Heart of HealingDocument316 pagesChurch, Dawson - The Heart of HealingRenato CamarãoNo ratings yet

- Dignity in Death and Dying: Joyce D. Cajigal, RNDocument14 pagesDignity in Death and Dying: Joyce D. Cajigal, RNWendell Gian GolezNo ratings yet

- Metabolism Clinical and ExperimentalDocument4 pagesMetabolism Clinical and ExperimentalusingwebNo ratings yet

- Administration and Management Skills Needed by Physical Therapist Graduates in 2010Document21 pagesAdministration and Management Skills Needed by Physical Therapist Graduates in 2010Vicente Agredo SNo ratings yet

- Role of Government in Health NotesDocument3 pagesRole of Government in Health NotesHarika CNo ratings yet

- Transkrip Tugas Percakapan Bahasa InggrisDocument3 pagesTranskrip Tugas Percakapan Bahasa InggrisZhincan 07No ratings yet

- DAFTAR OBAT LASA (Lampiran 4)Document3 pagesDAFTAR OBAT LASA (Lampiran 4)iid fitriaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Treatment of Venous UlcersDocument14 pagesGuidelines For The Treatment of Venous UlcerssorinmoroNo ratings yet

- Annexure I Crash Cart ArrangementDocument2 pagesAnnexure I Crash Cart ArrangementSnehal Sharma100% (1)

- Peripheral Retinal Degenerations: EditorDocument241 pagesPeripheral Retinal Degenerations: EditorFelipe AlarcónNo ratings yet

- Ultrasoundfor AURClin TerDocument8 pagesUltrasoundfor AURClin TerLyka MahrNo ratings yet

- Rigel 333 Instruction ManualDocument37 pagesRigel 333 Instruction ManualTerraTerro Welleh WellehNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Tips : FibrereducesrisksofDocument1 pageNutrition Tips : FibrereducesrisksofharzuNo ratings yet