Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jones, Caroline Ab Ex Ego

Jones, Caroline Ab Ex Ego

Uploaded by

Ara OsterweilOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jones, Caroline Ab Ex Ego

Jones, Caroline Ab Ex Ego

Uploaded by

Ara OsterweilCopyright:

Available Formats

Finishing School: John Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

Author(s): Caroline A. Jones

Source: Critical Inquiry , Summer, 1993, Vol. 19, No. 4 (Summer, 1993), pp. 628-665

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343900

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Critical Inquiry

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Finishing School: John Cage and the Abstract

Expressionist Ego

Caroline A. Jones

Meet the (De)Composer

Buckminster Fuller once described the breakfasts he enjoyed with

John Cage and Merce Cunningham during the summer of 1948, under

the groves of yellow pine at that experiment in American education, Black

Mountain College:

We really did have a great deal of fun because I spent that summer

with them on a fun, schematic new school [I called] "the finishing

school." We would finish anything.... We would really break down

all of the conventional ways of approaching school. And the finishing

school was going to be a caravan, and we would travel from city to city,

and it would be posted outside of the city that the finishing school was

coming.'

This paper originated in a talk given at the conference and symposium organized to

celebrate John Cage's eightieth birthday and visit to Stanford University in January of

1992. I am grateful to the organizers for including me, and to Wanda Corn for first sug-

gesting that I be asked to participate. For help with the substantial revisions needed before

publishing, I want to thank Marjorie Perloff for her preliminary criticisms. For their help-

ful insights and shared scholarship, I owe deep debts to Martin Brody, Arnold Davidson,

Peter Galison, Daniel Herwitz, Amelia Jones, and Stephanie Taylor; for moral support,

inspiration, and exemplary courage I thank Norman O. Brown.

1. Quoted in Mary Emma Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain College (Cambridge, Mass.,

1987), p. 156.

Critical Inquiry 19 (Summer 1993)

o 1993 by The University of Chicago. 0093-1896/93/1904-0005$01.00. All rights reserved.

628

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 629

The finishing school. School of finish, and of finishing off. This was the

summer Cage's aesthetic matured-the summer when Cage, Fuller, and

other agitating influences amused themselves by imagining what they

would finish next. After Western music (Beethoven) and Western archi-

tecture (the Greeks), they felt sure they could "finish anything" and imag-

ined hiring themselves out for the job.

It seems paradoxical to speak of Cage and "finish" in the same

breath-Cage, the champion of indeterminacy, open-endedness, and

chance. Particularly now, after his death, he will be canonized as the

staunchest leader of our heroic American avant-garde, opposed in every

way to the bourgeois notions of lefini seen to undergird academicism since

the days of Colbert and Bouguereau. And certainly Cage was opposed to

"finish" in his life and work, if by finish we mean the polishing of form to

effect a transparency of medium. It is this cosmetic and embalming finish

that he addressed in 1949 in the artist-run journal The Tiger's Eye, writing:

"A finished work is exactly that, requires resurrection."2 But the other

side of "finishing school" is echoed in Cage's comment, in the same essay

in The Tiger's Eye, that "schools teach ... classical harmony. Outside

school, ... a different and correct structural means reappears" ("F," p.

172). This finishing school-this caravan roaming at the outskirts of town,

at the boundaries of civilization-is a more appropriate vehicle for Cage's

early aims: to finish school and emerge into a new independence from aca-

demic forms; tofinish off the dead, the ossified, or the moribund; to resur-

rect only what remained capable of life.

This essay concerns just what it was that John Cage helped finish in

the late 1940s and early 1950s and what kinds of spaces he cleared before

he became the peaceful patron saint of our avant-garde heaven.3 My

observations here allude to much larger stories that can only be told

elsewhere-stories about the ending of Europe, the death of fathers, the

making of Americans.4 Norman O. Brown quoted Cage when he wrote

2. John Cage, "Forerunners of Modern Music," in Ann Eden Gibson, Issues in Abstract

Expressionism: The Artist-Run Periodicals (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1990), p. 173; hereafter abbre-

viated "E" Cage's essay originally appeared in The Tiger's Eye 7 (Mar. 1949): 52-56.

3. Or, as Paul Griffiths would have it, "the apostle of indeterminacy" (Paul Griffiths,

Cage [Oxford, 1981], p. 1; hereafter abbreviated C).

4. "The making of Americans" is, of course, Gertrude Stein's phrase, and it was used

by the organizers of the John Cage at Stanford conference for the title of the panel in

which a version of this paper was originally presented. The linkage of Stein and Cage as

avant-garde modernists was the conscious and approved significance of this reference; my

Caroline A. Jones is assistant professor in art history at Boston Uni-

versity where she teaches recent art and theory. Her books include Mod-

ern Art at Harvard (1985), Bay Area Figurative Art 1950-1965 (1988), and

Machine in the Studio (forthcoming).

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

630 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

that "we know all we need to know about Oedipus, Prometheus, Hamlet";

but, wisely, he preceded this by observing that "Cage in 1959 is not the

same as Cage in 1974."5 For my own essay (begun on the occasion of

Cage's eightieth birthday and finished shortly after his death), I want to

return to that earlier time lest we forget Oedipus, Prometheus, and Ham-

let. Americans in their making have rarely forgotten those fierce sons or

failed to emulate them in their struggles to carve a culture from within the

colonial outpost of an aging empire.

In his early compositions-verbal and musical-Cage engaged,

among other things, the problematic of the abstract expressionist ego.6

His critique was both explicit and implicit, operating by word, deed, and

negativity to address what would come to appear hegemonic in American

modernism of the 1950s: the cultural construction of the artist as a mascu-

line solitary, his artwork as a pure statement of individual genius and

autonomous will.7 Cage's critical modes, the how of his "finishing school,"

constitute the central subject of this essay. Pursuing the trajectory of his

career in its cultural context, I first view Cage's search for technology as a

way of countering, or complicating, the abstract expressionist ego in its

search for a natural sublime. Second, I examine the functions of Cagean

silence in addressing that same ego, exploring Cage's multiple equations

of silence with nothingness, death, life, the sound of Others, the with-

drawal of the body, the hiding of beauty, the absence of ego, and the birth

of unintention. Finally, I view the presence of silence in Cage's work in

relation to a potentially homosexual aesthetic, particularly as read in by

the younger visual artists attracted to his work and ideas.

Pilgrims of the Technological Sublime

From differing beginning points, towards possibly different goals,

technologists and artists ... meet by intersection ... imagining

thesis, which suggests covert linkages at the deeper level of a resistant gay/lesbian aes-

thetic, proved more problematic to the conference organizers and participants. I take this

problematic as my problematic: how an absence or negativity can function to convey mean-

ing in cultural texts.

5. Norman O. Brown, "John Cage," in John Cage at Seventy-Five, ed. Richard Fleming

and William Duckworth (Lewisburg, Pa., 1989), pp. 105, 104.

6. I use the term problematic because this discursively produced and culturally main-

tained subjectivity, with its countless historical shifts, could never be firmly secured. The

abstract expressionist ego should thus be read with scare quotes throughout this essay.

7. Michael Leja has offered a nuanced reading of this dominant abstract expressionist

subjectivity in his book, Reframing Abstract Expressionism: Subjectivity and Painting in the

1940s (New Haven, Conn., 1993). I am grateful to Leja for sharing his introductory essay

and helping establish the shifting terms negotiated in constructing what I term the abstract

expressionist ego.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 631

brightly a common goal in the world and in the quietness within each

human being.

-CAGE, "Forerunners of Modern Music" (1949)

Cage was photographed at Black Mountain in 1948, that summer of

breakfasts for the "finishing school," sporting a spiky outgrown brushcut

(fig. 1). This distinctive haircut, determined by a wartime military culture

but located raffishly outside its disciplined parameters, later earned him

the sobriquet "Frankenstein" among an adoring Italian public.8 Was

Frankenstein Cage, manipulating tapes in a Milanese radio station, or his

"monstrous" progeny, the odd electronic music broadcast through town?

Was Frankenstein the mechanical monster, or his scientist-maker? Both, in

any case, were pilgrims of the technological sublime, that romance Leo

Marx has explicated as part and parcel of the American dream.9 The ten-

sion between the hushed, primordial wilderness and the noisy technolo-

gies we bring to "improve" it is the fueling dynamic of American culture,

and it occupied Cage from the very beginning: "'[I saw] my function ... as

an inventor and research worker rather than as an artist. I had been very

much influenced by ... the need to apply modern technology to music' "

(BB, pp. 90-91). Cage's famous production of the prepared piano in 1940

exemplifies the intervention of the mechanical into the organic. Despite

the piano's highly technological manufacture, it presents a body that con-

ceals a metallic, mechanical interior in a sheath of organic wood and ivory

(an android rather than a cyborg). Modest Victorians saw the piano's body

in such anthropomorphic terms, clothing its naked legs in decent draper-

ies.'0 Cage's determination to open the piano's cabinet and to reveal

and manipulate its steel strings with a variety of foreign objects was an

8. The full nickname "the good-looking Frankenstein" was given him by the Italian

press in 1958 when Cage was in Milan, composing experimental music on tape and compet-

ing on a televised quiz show (quoted in Calvin Tomkins, The Bride and the Bachelors: Five

Masters of the Avant-Garde [New York, 1965], p. 132; hereafter abbreviated BB). Clearly

meant to be affectionate, the nickname is nonetheless revealing of European attitudes

toward postwar Americans (creators of the A-bomb), whose technophilia could assume

monstrous proportions.

9. See Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America

(Oxford, 1964). See particularly Marx's discussion of Melville's Ahab and the technologi-

cal sublime (pp. 294-95) and his argument that Melville, by using machine imagery to

relate the butchery of whaling to the violence of Western civilization, speaks to "the contra-

diction at the heart of a culture that would deify the Nature it is engaged in plundering" (p.

301). As Marx put it more recently, "'the rhetoric of the technological sublime' " is "a rhet-

oric designed to invest secular images of technology with the capacity to evoke emotions-

awe, wonder, mystery, fear-formerly reserved for images of boundless nature or for

representing a response to divinity" (Marx, "Does Pastoralism Have a Future?" in The Pasto-

ral Landscape, ed. John Dixon Hunt [Washington, D.C., 1992], p. 225).

10. For one discussion of the piano's technology, see Edwin M. Good, Giraffes, Black

Dragons, and Other Pianos: A Technological History from Cristofori to the Modern Concert Grand

(Stanford, Calif., 1982).

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

632 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

FIG. 1.-John Cage at Black Mountain, Summer 1948. Photo: Hazel Larsen

Archer. Courtesy Mary Emma Harris.

aggressive, mechanistic intervention. His technical intrusion into the "nat-

urally" organic was characteristic of American culture, but it was also sug-

gestive of earlier possibilities in European and American modernism that

would be largely suppressed in the postwar hegemony of American

abstract expressionist art."I As against the expansive abstract expressionist

11. I'm thinking here of the musical experiments of Edgard Varese and the machine

concerts of the dadaists.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 633

discourse of the natural sublime, with its emphasis on the awed individu-

al's relationship to primordial nature, Cage called for "the use of techno-

logical means" requiring "the close anonymous collaboration of a number

of workers," leading "not to self-knowledge ... [but] to selflessness" ("F,"

pp. 175-76).12 Cage's first mature statement, the prepared piano of 1940,

already exemplified this belief in a mechanistic antidote to ego. It was an

instrument built, in part, to speak the bold vernacular of the technological

sublime.

Cage, son of an inventor, brought this most American enterprise to

music. Several of his earliest compositions were titled "Inventions"; he

compares an early "claim" for his music to a patent specification claim.'3

But his earliest innovation, the prepared piano, suggested the creative tin-

kering celebrated as Yankee ingenuity rather than the entrepreneurial

capitalism of Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and the like. Others, notably

Cage's own mentor Henry Cowell, had experimented with the percussive

capabilities of the piano, but Cage concretized such whimsies, taking them

further away from improvisatory performance to embed them in the tech-

nology of the piano itself.'4 By inserting nuts, bolts, screws, and other

mechanical (Frankensteinian?) bits under the strings, Cage altered their

timbre and emphasized their percussive capabilities. He also rendered

them unsuitable as vehicles for the vocal and instrumental traditions of

Western harmony, putting listeners in mind of the Balinese gamelan.'5

The artificially normative consonance of the piano's steel strings, deter-

12. For an extended discussion of the technological sublime and its relation to the

abstract expressionists' natural sublime, see my "Machine in the Studio: Changing Con-

structions of the American Artist, 1945-1968" (Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1992),

and forthcoming in expanded form.

13. Cage composed "Six Short Inventions" in 1932-33. The notion of a musical

"invention" also has its source in Bach and other earlier composers celebrating authorial

creation over a mimicry of nature; Cage is playing with both senses here. "Claim," a section

of Cage's "Forerunners of Modern Music," reads: "Any sounds of any qualities and pitches

(known or unknown, definite or indefinite), any contexts of these, simple or multiple, are

natural and conceivable within a rhythmic structure which equally embraces silence. Such

a claim is remarkably like the claims to be found in patent-specifications for and articles

about technological musical means" ("F," p. 175).

14. Cage recalled seeing Cowell perform: "He used a darning egg, moving it length-

wise along the strings while trilling ... on the keyboard" (Cage, "How the Piano Came to

Be Prepared," Empty Words: Writings '73-'78 by John Cage [Middletown, Conn., 1979], p. 7).

Cowell's piece The Banshee (1925) was notable for its improvisatory use of the piano's

insides. Cowell wrote in 1952, Cage "got an idea by knowing my own things.... and he

took it up and prepared the strings, which I had never done" (quoted in David Revill, The

Roaring Silence: John Cage: A Life [New York, 1992], pp. 69-71).

15. "The prepared piano ... converted the piano to a percussion instrument without

harmonies" (Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain College, p. 154). See also Cage's view that

contemporary music composition was moving away from Western harmonics in Cage, "The

East in the West," Modern Music 23 (Spring 1946):115. It was Virgil Thomson who com-

pared the prepared piano to the "'Balinese gamelang orchestra'" (BB, p. 90).

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

634 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

mined by manufacturers and enforced by piano tuners, was irrevocably

disrupted. The sonorous piano was changed from a potentially tonal

instrument, evoking the harmonic range of a full orchestra, to a pinging,

chiming, gently clamorous sound machine. Arnold Sch6nberg, presum-

ably in reference to this feat, referred to his former student Cage not as a

composer but as "'an inventor-of genius' " (BB, p. 85).16

If the prepared piano emerged from Cage's Frankensteinian search

for the technological sublime-"imagining brightly a common goal" with

technologists-it also had other contexts. For the altered instrument was

invented specifically to provide accompaniment for the choreography of

Syvilla Fort, an African-American dancer at the Cornish School in Seattle

where Cage was working at the time. The ballet, called Bacchanale, was to

be held in March 1940, and Cage recalled it as "'rather primitive, almost

barbaric' " (BB, p. 89).17 In search of a correspondingly "primitive" effect,

he wanted to use the all-percussion orchestra he had assembled out of tin

cans, hubcaps, brake drums, and other mechanical detritus (rattletrap

American good-enough engineering versus cultured European crafts-

manship).18 But these gustatory and vehicular remnants required several

performers and more space than Fort could spare on stage. Cage's solu-

tion, the percussive prepared piano, was simple and technological. It pro-

duced the unsettling effects required, in a fixed yet portable device

capable of repetition and control. Cage's first mature act of artistic inde-

pendence from European music (represented in its rarified avant-garde

form by Schonberg's twelve-tone system) was thus achieved via

primitivism, through a lowly tinkerer's technology of nuts, bolts, and

wires. Despite Fort's mythological title for her dance, with its echoes of

the scandalous European high modernism of Nijinsky's L'Apreis-Midi d'un

faune, the "primitivism" and "technologism" of the music could be identi-

fied by the participants as authentically native to the American soil.

Primitivism has often been the avant-garde's first recourse to the

problem of cultural tradition, of course, a "primitivism" read into the art

of colonized, conquered, or merely Other cultures. But unlike the alien

exoticism that Europeans sought for their paintings-for example, those

African Grebo masks Picasso encountered in the Trocadero Museum and

16. Sch6nberg's comment was apparently made to critic Peter Yates. Cage repeated

the remark to interviewer Jeff Goldberg in 1976; see Jeff Goldberg, "John Cage Inter-

view," in Conversing with Cage, ed. Richard Kostelanetz (New York, 1988), p. 6.

17. Tomkins dates the composition of Bacchanale to 1938, but both Griffiths and

Revill give the date of March 1940, from notations on the score. See C, p. 13 and Revill,

Roaring Silence, p. 69. Griffiths notes the composition calls for a piano prepared with "one

small bolt, one screw with nuts, and eleven pieces of fibrous weather stripping" (C, p. 13).

18. To the phrase "the use of technological means" Cage appends a footnote citing the

Swiss painter Paul Klee: "I want to be as though new-born, knowing nothing, absolutely

nothing about Europe." Thus, at this point, technology was identified as the absolute nega-

tion of European culture and tradition (quoted in "F," p. 175).

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 635

painted "as a kind of exorcism" into his Les Demoiselles d'Avignon-Cage

and contemporary painters such as Jackson Pollock found "barbarism" in

their own country's past.19 At this point they were not so sensitive to the

barbarism of the white invaders (although later Cage would feel this

keenly). Their works echoed instead the great percussion traditions of

African-American slave music (remanent in American jazz) and the pow-

erful geometries of native American art.20 Particularly in this early part of

his career, Cage was clearly aware of the parallels between his chosen revo-

lution in music-self-described as durational rather than harmonic-and

the rhythmic basis ofjazz.21 In 1949, he praised the work "outside scho

by Satie and Webern, arguing that their "different and correct structur

means" were based on lengths of time rather than classical harmony; in

footnote, he explains, "This [durational basis] never disappeared fr

jazz and folk-music. On the other hand, it never developed in them, f

they are not cultivated species, growing best when left wild" ("F," p. 172

3). Although Cage rarely appropriated such "wild" sources directly, hi

very efforts to shift Western music from tonality and functional harmony

to an emphasis on indeterminacy and duration suggests a sophisticated

recognition of the differences fueling American vernacular culture and

understanding of the momentum gained from harnessing such differ

ences for "high" art.22

19. On Picasso's "exorcism" via African art, see "Primitivism" in Twentieth-Century Art

Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern, ed. William Rubin, 2 vols. (New York, 1984), 1:2

With specific reference to Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, see Leo Steinberg, "The Philosophi

Brothel, Part 1," Art News 71 (Sept. 1972): 20-29, and Mary Mathews Gedo, Picasso: Art

Autobiography (Chicago, 1980).

20. The issue of tribal or minority cultures as sources for "high" art is a vexatious on

which Jim Clifford addressed directly in his critique of the Museum of Modern Ar

"Primitivism" exhibition and catalogue. See James Clifford, The Predicament of Cultur

Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, Mass., 1988). See also Joh

Yau, "Please Wait by the Coatroom" and other essays in Out There: Marginalization and C

temporary Cultures, ed. Russell Ferguson et al. (New York, 1990), and The Myth

Primitivism: Perspectives on Art, ed. Susan Hiller (London, 1991). What is needed now i

nuanced reading of the cultural interplay in tribal art and a recognition of these suppose

"native" styles as sophisticated Creole systems operating between a dominant culture an

multiple source vocabularies. This reading would make room, for example, for the pres

sures of the market on tribal art, exercised from the beginning through trading betwe

tribes and, later, through Western-run trading posts. There is a reason why Navajo blank

styles are often named for the trading post with which they are associated (for examp

Ganado), and jazz emanated from cities with great immigrant populations (Chicago, N

Orleans, New York). The presence of klezmer in jazz, aniline-dyed red flannel fiber

Ganado chief blankets, or Venetian glass beads on Chippewa moccasins should complicat

any reading of "native" American or African American art forms.

21. "Of the four characteristics of sound, only duration involves both sound an

silence. Therefore, a structure based on durations... is correct, ... whereas harmonic structur

is incorrect" ("F," p. 172 n. 2; emphasis added).

22. Cage, like the cultural critics of the Frankfurt school, was not drawn to jazz in p

formance; as I note below, his interest in vernacular noise always stopped at the establish

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

636 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

It was in this spirit that Pollock praised "the formal qualities" of

Navaho sand painters, and Barnett Newman celebrated the bold designs

of Northwest Coast cultures such as the Kwakiutl. However problematic it

may seem now to adapt and transform the art of dominated cultures for

the production of an avant-garde aesthetic that sought its own kind of

domination, adventurous Americans emerging from the self-perceived

provincialism of the 1930s into the globalism during and after the Second

World War thought of jazz and "American Indian" art as their own. They

turned to "the primitive" not to escape from Europe (as had Picasso) but

to discover and create (through a similar appropriation) the formal means

for a truly American art.23

That said, however, there remained the perfume of exoticism in these

works-primitivism without the quotes. Thus Cage's barbaric piano was

inspired by an African American's dance, and thus Pollock and others

sought to escape the rational and civilized through some shamanistic, ritu-

alized, bodily engaged art.24 Contemporary journals such as Life and Art

News published photographs of Pollock's rhythmic "dance" around the

canvas. His unconventional engagement with the painting's surface, his

boundaries of "high" culture. But in 1952, during this early period of his career, Cage actu-

ally composed a piece by fragmenting jazz recordings (as in, I note, the practice of 1980s

and 1990s African-American rap composers/break dancers/hip-hop musicians). The

piece, Imaginary Landscape No. 5, was his first on tape. Griffiths writes of Cage's '"jazz-

tinged piano" in compositions from the early 1940s, around the same time that Bacchanale

was written (C, p. 15). For a discussion of the ambivalent relationship between American

intellectuals and jazz, see Andrew Ross, "Hip, and the Long Front of Color," No Respect:

Intellectuals and Popular Culture (New York, 1989), pp. 65-101.

23. Of course, as white male artists, painters such as Stuart Davis and musicians such as

Tommy Dorsey were empowered to produce this "American" art and their black colleagues

were not. On the presence of a generalized (and generative) "blues aesthetic" in American

culture, see Houston A. Baker, Jr., Blues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature: A Vernacular

Theory (Chicago, 1984).

24. That Cage was directly responding to Syvilla Fort and her dance in his composition

should be clear. Even at the end of his life, when years of simultaneous but uncdnnected

music for Merce Cunningham's dances suggested some kind of indifference, Cage

recounted a telling anecdote about himself and Karlheinz Stockhausen: "once i was with

karlheinz we were just walking in cologne and he said if you were writing a song would you

write music or would you write for the singer i said i would write for the singer he said well

that's the difference between us i would write music" (Cage, I-VI [Cambridge, Mass., 1990],

pp. 10-11). Cage did not see himself as primitive, of course; in this respect he was quite dif-

ferent from Pollock, who flirted with a Brandoesque "caveman" image despite the

intellectualism of his supporters. See Ellen G. Landau,Jackson Pollock (New York, 1989), p.

14. Sufficiently discomfited by this tendency of Pollock's, Cage declined to write the music

for Hans Namuth's documentary on the painter, recommending Morton Feldman for the

job. See Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, Jackson Pollock: An American Saga (New

York, 1989), p. 663. My argument is not that the two men were similar in their use or

approach to the primitive but rather that both participated in this pervasive theme of

American modernism.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 637

entry into what critics termed "the arena" of the canvas, is witnessed fur-

ther by the handprints appearing on the wall-sized canvases he was pro-

ducing around 1948 (in particular, Number One, 1948). The handprints'

link to ritual art lay in their evocation of the neolithic cave paintings

recently exposed at Lascaux and Peche Merle; art world cognoscenti knew

also of Pollock's statements praising native American sand paintings and

read of his desires to be "more a part of the painting.., literally [to] be in

the painting."25 This famous quote, in fact, is from the one and only issue

of Possibilities, the journal founded by Robert Motherwell, Cage, and oth-

ers that appeared in the winter of 1947-48.26 It is an indication of the flu-

idity and expansiveness of avant-garde aesthetics at the time that both

Cage and Pollock could occupy the same platform and seem to articulate

related sensibilities.27 Neither the fluidity nor the expansiveness would

last. Pollock would remain a central figure within the abstract expression-

ist canon, and Cage would become the mentor for a younger generation

now seen to oppose it.

Cage, "the Club," and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

That Cage was an important member of the abstract expressionist

community went unsaid in 1948, but it needs emphasizing now. "I had,"

he recalled in 1965, "in the late '40s and the early 50s, been part and par-

cel of the Artists Club."28 Described as "a loose social and aesthetic organi-

zation where artists could meet to discuss issues of common interest," the

25. Jackson Pollock, "My Painting," Possibilities 1 (Winter 1947-48): 79. Cage makes

reference the following year to Pollock's "sand painting" in "Forerunners of Modern

Music," where he writes: "Just as art as sand-painting (art for the now-moment rather than

for posterity's museum-civilization) becomes a held point of view, adventurous workers in

the field of synthetic music ... find that for practical and economic reasons work with mag-

netic wires (any music so made can quickly and easily be erased, rubbed-off) is preferable to

that with film" ("F," p. 175).

26. The periodical was edited by Robert Motherwell (art), Harold Rosenberg (writ-

ing), Pierre Chareau (architecture), and John Cage (music). Despite its survival for only

one issue, Possibilities is described as "occup[ying] a pivotal position in the periodical lit-

erature of Abstract Expressionism" (Gibson, "Possibilities: 'The Thing-without Theory,'"

in Issues in Abstract Expressionism, p. 33). In addition to Possibilities, Cage's contribution to

which Motherwell found uncharacteristically disappointing (see ibid., p. 34), Cage contrib-

uted "Forerunners of Modern Music" to The Tiger's Eye and was himself the subject of Leon

A. Kochnitzky, "The Three Magi of Contemporary Music," The Tiger's Eye 1 (Oct. 1947):

77-81.

27. On the fluidity of early abstract expressionism and the problem of defini

"avant-garde," see Leja, "The Formation of an Avant-Garde in New York," in Ab

Expressionism: The Critical Developments, ed. Michael Auping (exhibition cata

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, N.Y., 19 Sept.-29 Nov. 1987), pp. 13-33.

28. Michael Kirby and Richard Schechner, "An Interview" (1965), in Conversing

Cage, p. 21.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

638 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

club began as the "Subjects of the Artist" school, evolving into "Studio 35"

and finally "the Club." At its inception in the fall of 1949, the club had

twenty members, swelling to eighty in less than a year.29 It became the pri-

mary arbiter of what would be called abstract expressionism, its members

even reluctantly endorsing the movement's name in a series of panel dis-

cussions held in 1952.30 Cage was invited to contribute to important peri-

odicals run by club members (such as The Tiger's Eye and, of course,

Possibilities); he was twice asked to speak to club members on a subject of

his choice.

But the club, that loose affiliation of bohemians that was the closest

thing to a New York school academy, was nonetheless ambivalent in its

relation to Cage, and he to it. If the prepared piano had participated in an

aesthetics of primitivism and sublimity (albeit a technophilic sublimity)

that linked Cage to his generation of artists in New York, his subsequent

move to silence and indeterminacy proved deeply alienating to the

abstract expressionists attempting to hold onto the banner of the Ameri-

can avant-garde. In the perpetual contest to control the meaning(s) of

modernism, Cage came to occupy a radically different perspective from

his cohort, serving to open a space for younger male artists whose names

are legion (the list begins with Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns but

continues to include Allan Kaprow, Robert Smithson, Robert Morris,

Walter De Maria, and countless others).31 As I shall argue further below, it

was the effigy of the Individual Ego that Cage burned in his meteoric rise

to avant-garde heaven. It was only an effigy because criticism and the art

world both work tirelessly to recuperate, protect, and construct a stable

or "real" artistic ego forever fortified against efforts to deconstruct it.

Indeed, it was the group of painters gathering at the club who struggled

perhaps the most manfully to make this subjectivity real. As Michael Leja

argues persuasively, the study of abstract expressionist subjectivities is par-

ticularly rich, given that "this art took subjectivity as its explicit subject

matter [and] offers an exceptionally clear picture of the dialectic within

which subjects, including cultural producers, are shaped by various dis-

courses and representations they encounter in their culture, which they

then go on as active agents to inflect, reshape, and (mis)represent."32 My

thesis in this essay is this: the critique of abstract expressionism by subse-

quent generations of American artists was engaged primarily with this

29. Gibson, introduction, Issues in Abstract Expressionism, p. 59 n. 1.

30. See Irving Sandler, The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expres-

sionism (New York, 1970), p. 2.

31. That these are all male artists may follow from the particular kind of space opened

by Cage; the fact is also a function of the historical period (the 1960s), since women did not

emerge with any force in the New York art world until the generalized climate of a feminist

critique (in the 1970s) empowered them to do so.

32. Leja, "Introduction: Framing Abstract Expressionism," Reframing Abstract Expres-

sionism, unpaginated galleys.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 639

subjectivity-a complex, discursively constructed, and ever-shifting

interpellation I term here the abstract expressionist ego. This ego was

held to be highly individualized, albeit barely the master of its id; given

prominence by the postwar power and prestige of America itself, it was

dominant and pervasive in the culture of the time. John Cage offered

some of the first tools for its critique, which first took place, I argue,

within a specific homosexual aesthetic.33

Cage came with his own perspective to the New York art scene of the

late 1940s, having already made friends and traded ideas with West Coast

avant-gardists Mark Tobey and Morris Graves. Their interest in Oriental

philosophies and tribal cultures, and Tobey's all-over, calligraphic "white

writing," gave Cage a particularly sophisticated angle on the abstract

expressionist interest in a native, American primitivism (achieved via a

native American "primitivism"). Seattle, where Cage met Tobey and

Graves (as well as Cunningham, who would become his lifelong compan-

ion), is far from Europe and its anxieties about tradition; it is a misty sea

town, named for an Indian chief and full of spectacular tribal art. Graves,

like the Northwest tribal cultures he studied, believed that the spirits of

animals could be summoned by art; he retained representation in his work

long after the New York school painters had become resolutely abstract.

Although Tobey's "white writing" was more readily assimilated to the

abstract expressionist model of all-over painting, he, too, held onto repre-

sentation, burying small figures in his webs of paint as if loathe to give up

entirely the blooming, buzzing physical world. This set the Western avant-

gardists apart from the New York painters' all-but-iconoclastic rejection

of the outside world. Where West Coast painters retained their interest

in an external referent, the New York school artists were seen to have

abandoned referentiality in favor of a deeply imagined inner state

of being.

Briefly put, the subjectivity of the New York school abstract expres-

sionist was constructed in the American culture of the late 1940s and early

1950s as that of an isolated, autochthonic, angst-ridden male genius, alter-

nating between bouts of melancholic depression and volcanic creativity.

Although early modernism contained many alternative modes of produc-

tion, including collective and anarchic ones, the variant of modernism

that became canonical in the United States during the cold war period cel-

ebrated the artist as a masculine solitary whose staunchly heterosexual

libido drove his brush.34 Pollock was the quintessential hero of this power-

33. See below for my discussion of the implications of the term homosexual aesthetic and

my efforts to use it in a nonessentializing way.

34. Such constructions were always unstable. Even during the mid-1950s, when

abstract expressionism was well on its way to becoming the American national (heterosex-

ual) style, the club included figures such as Frank O'Hara, who was fairly open about his

homosexuality. But as gay theorists have established (and I am thinking here of the work of

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick in her books Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

640 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

ful mythos, but even the hyperintellectual Ad Reinhardt could be por-

trayed in such terms."5 The gestural paintings of such artists as Franz

Kline and Willem de Kooning built on this romantic scaffolding and were

understood at the time as records of a spontaneous encounter with the

canvas, existential acts summoned with great courage from the depths of

the subconscious self. As Pollock said, "Painting is self-discovery. Every

good artist paints what he is."36

Another position was occupied by the abstract expressionist field

painters, whose visual and verbal works constructed the creative ego

somewhat differently. Still emphasizing the isolation of the creative act

and the awesome, even Nietzschean power of will required to conquer the

forces of destruction, such painters as Newman and Reinhardt saw their

paintings as opening the viewer to a deepened sense of self. In Newman's

words:

The painting should give man a sense of place: that he knows he's

there, so he's aware of himself. In that sense he relates to me when I

made the painting because in that sense I was there.... I hope that

my painting has the impact of giving someone, as it did me, the

feeling of his own totality, of his own separateness, of his own

individuality.37

A few quotes from journalists and essayists, writing in both big and

little magazines of the day, further suggest the dominance of this mode of

interpellation; even hostile critics in the popular press reinforced the ide-

ology of supersaturated individualism: "Until psychology digs deeper into

the workings of the creative act the spectator can only respond, in one way

or another, to the gruff, turgid, sporadically vital reelings and writings of

Pollock's inner-directed art"; or, even less sympathetic, "In fleeing from

the machine and the terrors of the man-made world, we have plunged into

Desire [New York, 1985] and Epistemology of the Closet [Berkeley, 1990]), the presence of

homosexuality within an intensely homosocial masculinist discourse should not surprise us.

On the social construction of all these categories, see Forms ofDesire: Sexual Orientation and

the Social Constructionist Controversy, ed. Edward Stein (New York, 1990). Without interro-

gating the sexual identities or gender aspects of the abstract expressionists, Serge Guilbaut

does an excellent job of charting the canonization and depoliticization of modernism in

postwar America in his polemical How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expres-

sionism, Freedom, and the Cold War (Chicago, 1983).

35. See my "Machine in the Studio" for this argument in its full form; see also my essay

"Andy Warhol's 'Factory': The Production Site, Its Context, and Its Impact on the Work of

Art," Science in Context 4 (Spring 1991): 101-32.

36. Pollock, interview with Selden Rodman (1956), quoted in Beryl Wright, "Chronol-

ogy," in Abstract Expressionism, p. 271.

37. Barnett Newman, interview with David Sylvester, in Sylvester, "The Ugly Duck-

ling," in Abstract Expressionism, p. 144.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 641

the dimly lit corridors of man's own psyche. ... Every least gesture of the

brush becomes a revelation, and our pessimism regarding the psyche is

such that, the cruder the gesture, the greater the revelation.""38 Even more

sophisticated authors, such as Clement Greenberg, who sought to distance

themselves from psychological analyses of the new art, reinforced the pre-

vailing image of the lonely, marginalized artist. Here is Greenberg, writ-

ing for British readers in 1947:

The fate of American art is being decided ... by young people, few of

them over forty, who live in cold-water flats and exist from hand to

mouth.... [They] have no reputations that extend beyond a small

circle of fanatics, art-fixated misfits who are as isolated in the United

States as if they were living in Paleolithic Europe. ... What we have

... is the ferocious struggle to be a genius.... Alas, the future of

American art depends on them. That it should is fitting but sad. Their

isolation is inconceivable, crushing, unbroken, damning.39

Harold Rosenberg, whose commitment to existentialism led him,

famously, to declare that the abstract expressionist painting was "not a pic-

ture but an event," extended the metaphor of isolation to include the art

as well as the artist: "The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation

from Value-political, esthetic, moral.... The lone artist did not want the

world to be different, he wanted his canvas to be a world."40 The painter

William Baziotes had earlier articulated such a position, writing in 1949:

"when the demagogues of art call on you to make the social art, the intelli-

gible art, the good art-spit down on them, and go back to your dreams:

the world-and your mirror.'"41

To round out this sketch of the subjectivities identified here as the

abstract expressionist ego, I turn to Robert Motherwell, historian and

intellectual of the New York school, and Cage's collaborator on Possibili-

ties. Motherwell had also founded, with Clyfford Still, the famous Subjects

of the Artist school discussed above, the source for all subsequent discus-

sion groups of the abstract expressionist avant-garde in New York.42 The

38. Quoted in Leja, Reframing Abstract Expressionism, unpaginated galleys.

39. Clement Greenberg, "The Present Prospects of American Painting and Sculp-

ture," Horizon 16 (Oct. 1947): 29, 30; emphasis added.

40. Harold Rosenberg, "The American Action Painters" (1952), The Tradition of the

New (New York, 1960), pp. 25, 30; emphasis added.

41. William Baziotes, "The Artist and His Mirror," quoted in New York School: The First

Generation, ed. Maurice Tuchman (exhibition catalogue, Los Angeles County Museum of

Art, Los Angeles, 16 July-i Aug. 1965), p. 11.

42. The school remains only vaguely documented; Motherwell does not cite Still and

includes William Baziotes, Mark Rothko, and the sculptor David Hare as founding mem-

bers. Still's participation in founding the school is documented only in the biographical

notes prepared for his 1959 retrospective; see my Bay Area Figurative Art 1950-1965

(Berkeley, 1989), pp. 164-65 n. 30.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

642 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

t~ 1 ~' I'

~~ q;

1L 'L~d

? I j i

:a ~?r

~?

?'

?r - ; '~1

14*

i:

i

*;'"

'

'I ?i

i,- ?1'

:H;1

:d

rt ;9 ? '

~~ ~?9 ??

e

I

.J

a

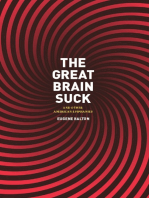

FIG. 2.-Robert Motherwell, Pancho Villa, Dead and Alive, 1943. Gouache and oil with

collage and cardboard. 28 in. X 35%/e in. Collection: The Museum of Modern Art, New

York.

small cooperative school was named, according to Motherwell, "to empha-

size that abstract art, too, has a subject," and Cage was among the artists

invited to speak on Friday evenings.43 Perhaps drawn together by their

common California roots, or their position as highly articulate intellectu-

als, Motherwell and Cage made an odd couple-Cage searching for a

technologically mediated selflessness and Motherwell for a way to paint

"what I have already discovered, what I know to be mine."44 For Motherwell,

the lone abstract expressionist genius was not only male, he was macho. In

his signature works (figs. 2 and 3), the still-vital genitals of Pancho Villa

(Mexico's romantic revolutionary outlaw) become enlarged to gigantic

scale to form the cojones of Motherwell's "Elegy to the Spanish Republic"

series.45 The subject of the artist, here, is the subjugated but latent

43. Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt, introduction to "Artists' Sessions at

Studio 35 (1950)," ed. Robert Goodnough, in Gibson, Issues in Abstract Expressionism,

p. 314.

44. Motherwell, in "Artists' Sessions at Studio 35 (1950)," p. 339; emphasis

added.

45. Motherwell actually referred to these forms as bull testicles, which have a privi-

leged function in the bullfighting rituals of Spain; the American Motherwell, lik

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 643

45

FIG. 3.-Robert Motherwell, Elegy to Spanis

80 in. X 100 in. Collection: Albright-Knox

Seymour H. Knox (1957).

potency of creative (and procreative) m

fused with seminal, powerful id.

How superbly ironic, then, that Cag

to speak to the prestigious Artists Club,

Subjects of the Artists school, chos

Among the listeners were aging dadai

who would not have blinked at Cage's

abstract expressionists in the group m

bull's-eye in Cage's target. To that aud

offered subjectlessness; to men captiv

bodies' parts, a bodiless philosophy; to

the New York school, an exercise in Z

with his sometimes impish, sometimes

evening. Acting as the Zen master to t

can avant-garde, he answered all ques

Hemingway before him, never surpassed the inte

twin traditions of republican politics and bru

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

644 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

prepared answers regardless of the question asked."'46 "I have nothing to

say/ and I am saying it."47 We can practically hear the cleansing fire crack-

ling through the underbrush.

But Cage's madness (his anger and his dadaist folly) had its method (as

always). To his less-than-rapt auditors-one of whom "stood up part way

through, screamed, and then said, 'John, I dearly love you, but I can't

bear another minute' "48-Cage intoned: "Arizona/ is ... almost too

interesting/,/ especially/ for a New-Yorker/ who is being interested/ in

spite of himself/ in everything" ("LN," p. 110). Here, Cage's private Ari-

zona might be an artist like Still, self-styled pioneer from the Dakota

plains, whose paintings figured the dramatic crags and escarpments of the

natural sublime, a landscape identified with the body of the artist and writ

large on the abstract expressionist canvas.49 Against such epic egotism,

Cage reminded his listeners that the subjects being obsessed about were

not trapped within the subconscious, in need of extrication, or figured in

the body of the artist; rather, they were all around, to be discovered in sim-

ple, silent wonder at the world.

The "nothing" in Cage's lecture was, preeminently, silence: "What we

re-quire / is silence" ("LN," p. 109), and silence was actively, even

maddeningly, inserted between words and phrases, breaking them out of

meaning into an ordered but nonsyntactical rhythm, a light snowfall of

phonemes falling in empty space. Without duplicating the columnar

typography that Cage used in his text to enforce visual equivalents for his

verbal silence, I suggest the space here through slashes, which should be

read as beats, gaps, and caesurae measuring the text: "But/ now/ there

are silences/ and the/ words/ make/ help make/ the/ silences" ("LN," p.

109). The function of silence is thus the central theme of the "Lecture on

Nothing"; Cage chose it to characterize his first major collection of writ-

ings in which "Lecture" is included, the eponymous Silence of 1961. "We

need not fear these/ silences,-/ we may love them" ("LN," pp. 109-10; my

emphasis).

There were other nothings beside Cage's in 1949 and gaps other than

silence that his audience might have expected to encounter that night.

Most obviously, there was the existential abyss figured by Jean-Paul

Sartre's Being and Nothingness (1943)-the great absence figured by

death. Existentialism, which had "replaced Freudian andJungian dogmas

as an intellectual frame of reference" among New York school painters,

46. Cage, foreword, Silence: Lectures and Writings by John Cage (Middletown, Conn.,

1961), p. ix.

47. Cage, "Lecture on Nothing," Silence, p. 109; hereafter abbreviated "LN."

48. Cage, describing the reaction of Jeanne Reynal, foreword, Silence, p. ix.

49. In addition to Motherwell's phallus and testicles, I am thinking of Still's cryptic

self-portrait, 1946-L (now at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) as ready examples

of the covert priapic figure in abstract expressionist paintings.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 645

gave meaning to nothingness, as Sartre's title suggests, precisely through a

juxtaposition with Being, a contrast between action and death (which

enforces the ultimate withdrawal of the body from action and serves as the

terminus of possibility represented by Being).50 As Lithuanian-French

philosopher Emmanuel Levinas put it in the discussion of existentialism

published in the New York artist-run journal Instead, "do not the catego-

ries of potency and act suffice to express this new notion of existence? ...

Because every other possibility is fulfilled and becomes act, .... death

becomes the non-reality, the non-being."51 The popular understanding of

existentialism that operated in the abstract expressionist communities on

both coasts was established by such writers as Levinas and Sartre, whose

ideas were propagated in the New York artist-run journals; they were fur-

ther popularized and given tremendous force by Rosenberg in his famous

essay on "action painting"-a call for a quintessentially embodied gesture

against the void of death's disembodiment.52 Above all, the abstract

expressionist reading of existentialism emphasized the heroic individual

artist, whose work would be a virtual instantiation of "potency and act." As

one American writer in 1958 summarized it, existentialism forced a con-

frontation with "the impotence of reason confronted with the depths of

existence; the threat of Nothingness, and the solitary and unsheltered condition

of the individual before this threat."53

50. See Sandler, The Triumph of American Painting, p. 98.

51. Emmanuel Levinas, in discussion with Jean Wahl, "An Essential Argument within

Existentialism" (1946), trans. and ed. the editors of Instead, in Gibson, Issues in Abstract

Expressionism, p. 303. This discussion originally appeared in volume 7 of Instead (ca. 1948).

L vinas goes on to answer his own question in the negative, "I do not think so," and his sub-

sequent statement about death is meant to gloss this position. As Levinas is at pains to make

clear in this late 1940s defense of Heidegger as the "one and only existentialist," being is

utterly at odds with death, since being and possibility are one, "so much so that at the

moment of [possibility's] exhaustion we have death" (ibid., pp. 301, 303). Thus potency

(as possibility) would, in Levinas's reading of Heidegger, be fully detached from the neces-

sity for act. We now read Levinas very differently, seeing him through Derridean eyes as

the rejector of Heidegger's view of death as "the ultimate test of virility and authenticity"

and the alternative to Husserl's redefinition of phenomenology as "'egology' " (Se in Hand,

introduction, The Livinas Reader, ed. Hand [Oxford, 1989], pp. 4, 2). We take instead the

post-1950s Levinas as model, his ethical philosophy summarized by the elegant statement,

"the idea of the Infinite is to be found in my responsibility for the Other" (Levinas,

"Beyond Intentionality," in Philosophy in France Today, ed. Alan Montefiore [Cambridge,

1983], p. 113).

52. Apparently Pollock fed Rosenberg the idea of abstract expressionist painting as

existentialist gesture; he himself got it from Newman, who presumably gleaned it from his

voracious reading of the artist-run periodicals of the time. This is according to Rosenberg's

rival, Clement Greenberg, interview with the author, 9 Oct. 1987.

53. William Barrett, Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy (Garden City, N.Y.,

1958), p. 31; emphasis added. This passage is quoted by Sandler, The Triumph of American

Painting, p. 98; Sandler goes on to comment, "But it must also be remembered that a man,

no matter how vulnerable and anxious, who makes himself is something of a hero, even if a

pathetic one."

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

646 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

But although death was certainly part of Cage's bodiless "nothing," it

was not all of it. Inactivity on the part of the artist, which amounted to

death in the thinking of the "existence philosophers" (as Livinas called

them), for Cage opened onto the untrammelled activity of the world.

Writing for a lecture at Juilliard a few years after the famous "Lecture

on Nothing," Cage presented fellow composer Morton Feldman as a

coconspirator in the new search for silence and nothingness:

The nothing/ that/ goes on/ is/ what/ Feldman/ speaks/ of/

when/ he speaks of/ being/ sub-merged/ in/ silence. / The/

acceptance/ of/ death/ is the source/ of/ all/ life./ ... Not one

sound/ fears/ the silence/ that ex-tinguishes it./ And/ no silence/

exists/ that is not/ pregnant/ with/ sound.54

To the yawning existentialist void, Cage merely yawned. The death of

action was to be confronted not with a terrified gesture of individual hero-

ism but placid restraint. Nothingness was to be met not with a scream but

with a "pregnant" silence. What gestated within that "pregnancy" and the

location of the silent but gravid body itself are complex questions whose

gender and sexual implications this essay can only begin to explore.

Noise, Silence, and the Body

"The highest responsibility of the artist is to hide beauty."

-JOHN CAGE, quoting W. H. Blythe's Haiku, in

"Juilliard Lecture" (1952)

The first part-on what Cage finished-is finished. The second

part-on what he began-is beginning. I turn from the prophylactic

"nothing" to the celebratory "something" that ensued.

In the 1949 "Lecture on Nothing," Cage already indicated what he

would enjoy in the early work of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

He wrote (and presumably said): "I used noises/. / They had not been/

in-tellectualized;/ the ear could hear them/ directly/ and didn't have to

go through any abstraction/ a-bout them/.... Noises, too/ , / had been

dis-criminated against/; / and being American, ... I fought/ for noises"

("LN," pp. 116-17). What is the difference between music and noise? As

Cage taught us, only the intervention of culture claims the one for amuse-

54. Cage, "Juilliard Lecture" (1952), A Year from Monday: New Lectures and Writings by

John Cage (Middletown, Conn., 1967), p. 98; emphasis added. Cage's reading of Feldman

was, of course, highly willful. Feldman led a notoriously heterosexual life and remained

much more closely identified with the abstract expressionists than Cage, culminating with

his musical homage to Rothko, composed for the opening of the Rothko Chapel in Hous-

ton, which was completed in 1979.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 647

ment and decries the other as annoying. Silence gives form to them both

and room for the sounds and activities of others. This was Cage's revela-

tion, and the work of these two younger painters struck, as it were, sympa-

thetic chords.

As against the natural, heroic sublime of the abstract expressionist

painters, Johns and Rauschenberg moved toward the quotidian. They

substituted found objects and found images, bracketed and made

strange to convey the violence of the everyday. In Rauschenberg's devas-

tated, unmade Bed (fig. 4), and the strange casts of body parts in Johns's

Target with Plaster Casts (fig. 5), there is a potential for indeterminacy

(always subverted by the institutional structures that frame our experi-

ence of the visual arts). Couldn't that bed be made up, the covers drawn

to conceal the torrid marks of the loaded brush? Couldn't those body

parts be thoughtfully lidded over, that shooting gallery converted to a

laconic row of plain trap doors? Rauschenberg put radios in his paint-

ings; Johns wanted to have sounds emerge with the opening of each trap

door. Agency slips from the maker to the passerby; as in Cage's works

(and those of his model, the heroic antihero and sexually ambiguous

"father" of postmodernism, Marcel Duchamp), the actions of the audi-

ence become part of the piece.55

When we speak of Cage's affinity for, and significance to, younger

artists, we recognize that influences go both ways. Already by 1949, when

he barely knew Cage, Rauschenberg was limiting his palette to mono-

chrome and using numbers to generate a kind of autonomous, depersona-

lized discipline in his work (for example, White Painting with Numbers [The

Lily White], 1949). His all-black paintings of 1951-52, which preceded the

all-white ones by a few months, used a ground of "found objects"-in this

case, newspapers-for their unreadable texture, their active silences.

When Cage and Rauschenberg found each other at Black Mountain again

during the summer of 1952, their friendship deepened, and both were

ready for further departures.

Cage writes, punctiliously, in Silence: "To Whom It May Concern:

The white paintings [of Rauschenberg] came first; my silent piece came

later."56 That summer of 1952, Cage saw Rauschenberg's apparently

blank canvases, each white, each apparently identical to its neighbor.

Rauschenberg held these canvas panels to be "hypersensitive," tender

membranes registering the slightest phenomenon on their blanched white

55. On the engendering of Duchamp as a feminized "father" for postmodernism, and

on the links between Cage's silences and Duchamp's "indifference," see Amelia Jones,

Duchamp and Postmodernism (forthcoming). I have benefitted greatly from Amelia's trench-

ant comments on this paper and from our ongoing conversations about the intertwined his-

tories of modernism and postmodernism.

56. Cage, prefatory comment to "On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, and His Work,"

Silence, p. 98.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L 0?1~?.:b?~~: ?~aD~? ~ilPI~i:

?'41

7111

kAl

Bi? M#A,

;B? Il~a~ F 3~~as~~: ~ i~~?lEAicl~ c

i i .rfit

g&W. ;r

FIc. 4.-Robert R

paint and pencil on

8 in. Collection: T

of Leo Castelli in

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 649

..i

.. .....;

i: :':.

? i

???: .?: ...

e .'I

: "'' ?"9,.r.::

FIG. 5.-Jasper Johns, Target with Plaster Casts, 1955. E

vas with plaster casts in wood construction. 51 in. X 4

Castelli.

skins.57 Cage described them as "airports for the lights, shadows, and par-

ticles," characteristically transposing Rauschenberg's semiotics of a

tender, almost invisible, but deeply sensate body into a technological met-

57. Quoted in Tomkins, Off the Wall: Robert Rauschenberg and the Art World of Our Time

(New York, 1980), p. 71.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

650 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

aphor for communication from the external world.58 Rauschenberg's

focus on the membrane's sensations and registrations gave way in Cage's

reading to a mechanically hardened body-nerve-laden integument

become inert runway, skin become concrete.59

Cage's experience of the white paintings encouraged him to proceed

with his "Silent Piece." Its title, 4' 33", referred to increments of time,

but the numbers were often read, to Cage's amusement, as measurements

of a still body in space (see BB, p. 118). The question posed by the three-

part piece was straightforward but opened onto great complexity: why not

see what happens in that place, in that space of time, unintended by the

artist? Although in one sense Cage looked outward, to other bodies, to

generate content (where Rauschenberg was interested in what registered,

internally, from the touches of photons on his paintings' membranous sur-

faces), 4' 33" can also be seen as a fundamentally disembodied piece.

Rather than Rauschenberg's white objects, which remained three-

dimensional bodies in the world, Cage offered a bracket of silence, the

only body being the unmoving one of the performer, whose stillness

inverted the customary athletics of virtuosity into a model of inert, if

attentive, quiescence. The only body acoustically present in 4' 33" is the

body of sound; the withdrawal of the performer's body from action para-

doxically authorizes our recognition of ambient noise.

The famous "Happening"-Theater Piece #1 (1952)-was another

development of Cage's interest in a neutral bracket for varied and unpre-

dictable experiences. Staged at Black Mountain by Cage with Rauschen-

berg, Cunningham, and others during the summer Cage found such

inspiration in Rauschenberg's work, the event has been recalled with

Rashomon intensity and incommensurability: performers, audience,

dogs, weather, and white paintings all participating in an uncoordinated

accretion of events.60

The aesthetics of accretion and accumulation further linked Cage

with the younger painters, who gave each thing its autonomy within their

ultimately mysterious bricolages. They also shared with Cage the aesthet-

ics of the handyman, the tinkerer, the practical engineer. Cage had

admonished in the "Lecture on Nothing": "But beware of/ that which is/

breathtakingly/ beautiful, /for at any moment/ the telephone /may

ring/ or the airplane/ come down in a/ vacant lot" ("LN," p. 111). This

58. Cage, "On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, and His Work," p. 102.

59. Martin Brody has suggested that "airports" may also be "air ports," or openings in

the air. In my reading the technological side of Cage dominates the whimsical.

60. In part it included Rauschenberg's white paintings and scratchy Edith Piaf

records; Cage, M. C. Richards, and Charles Olson reading from the tops of two ladders;

Cunningham dancing with the unexpected accompaniment of a stray dog; David Tudor

playing a prepared piano and a radio; and someone projecting films and slides upside-

down. The event terminated with the serving of coffee. See Harris, The Arts at Black Moun-

tain College, pp. 226-28.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 651

suggests, again, the technological sublime: a directive to find pleasure in

the aesthetics of an irrevocably altered environment, to celebrate, as

Whitman had, the "great achievements of the present ... the strong light

works of engineers."6' These are paintings that come with handy direc-

tions (Rauschenberg's Coca-Cola Plan, 1958), or moving parts that allow

them to make themselves, as if automatically (Johns's Device Circle, 1959).

As in Cage's music, the viewer, the auditor, and the environment each

enter in; the piece does not exist until experienced in time by another. In

place of the artist's body figured by the abstract expressionist canvas,

these works implied activity on the part of others' bodies-activity that

shielded, deflected, or displaced references to the artists' own.

But, as my comments on the place of the body in these works sug-

gest, there are distinctions to be made. Cage was never wholly commit-

ted to the suggestions of membranes and bodies that remain palpable in

Rauschenberg's work and rhetoric; similarly, he was not partisan to

Johns's and Rauschenberg's low-life technological sublime. Cage still

held out for an authentic high culture that would be "independent/ at

least from/ Life, Time and /Coca-Cola" ("LN," p. 117). He celebrated

creation versus reproduction, believing it important to "remove the

records from Texas/ [so that] someone/ will learn to sing" ("LN,"

p. 126).62 This stood in contrast to Rauschenberg (the Texan) and his

Coca-Cola optimism, where reproductions were reinvested with aura

(amidst the fetishizing tawdriness of Odalisk or in one of his later manip-

ulations of photographic silkscreens). Rauschenberg's erotic humor is

also un-Cagean. In the "combine painting" Odalisk (1955-58), both title

and assemblage work the joke. The punning of obelisk (that perfected

monumental lingam), with odalisque (its voluptuous female repository)

is complex. The pun operates with the work's electrified empty center

and tacky cheesecake photos to produce a more "pointed" critique of

heterosexism than Cage would ever tolerate in his rigorously dispassion-

ate art.

Although I earlier suggested a relationship between Ra

Bed, Johns's Target, and Cage's vernacular noises, distinct

made here as well. These objects fascinate us, as they fascin

questions present themselves: whose bed? (Rauschenberg's, a

And what happened there? Confronted byJohns's work, we

body parts, and why fetishized, collected, shut away? This

different sort-what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick terms the "clo

61. Walt Whitman, "Passage to India" (1870), Complete Poetry and Col

York, 1982), 11. 2-3, p. 531.

62. Their learning to sing suggests to me that Cage is not calling here

folk culture, which, presumably, Texans could generate on their own. I

pursuing a model of the cultural elite that will tell Texans what to lear

them-part of the "finishing school" caravan, perhaps.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

652 Caroline A. Jones Cage and the Abstract Expressionist Ego

a certain type of homosexual aesthetic.63 It is clear in such works that some-

thing happened, that there are meanings to conceal behind those trap

doors and between those ravished sheets.64 The body parts in John's

assemblage are not the mysogynist surrealist synecdoches of pendulous

breast, rouged lips, or furred female parts. Instead we see one smooth

male pectoral with its trim nipple, an angular ankle, long fingers, a recum-

bent penis. As against Allen Ginsberg's contemporaneous Howl (1956),

with its exuberant homoeroticism and its savage outcry at the repression

of Otherness in America, Rauschenberg and Johns allude only tan-

gentially to their lives as gay artists in New York.65 Secrets become the

engine of their art, but that engine's autobiographical chuffing can be

heard, however faint. The younger, gay-identified artists' muting of the

self-confessional abstract expressionist ego still had its function in a

homophobic 1950s America. In that context, icons of homoerotic body

parts could never be as welcome as heterosexist ones.

My shorthand reference to Johns and Rauschenberg as "gay artists,"

and the discussion that follows of a potentially homosexual aesthetic

operating in Cage's work, should be seen as unavoidable linguistic essen-

tializations of what are instead shifting fabrics of historically determined,

socially constructed, and discursively maintained sexual differences.

These and other artists of the time did not "come out" in the post-

Stonewall sense (see Johns's statement in 1978 that, early in his career, he

preferred to "hide my personality, my psychological state, my

emotions").66 But their homosexuality was inferred and constructed none-

theless; it became sufficiently salient so that there was paranoid talk of a

"homintern" among the aggressively masculinist painters of abstract

expressionism, who feared "a network of homosexual artists, dealers, and

museum curators in league to promote the work of certain favorites at the

expense of 'straight' talents."''67 As gay theorists (such as Sedgwick, Ed

Cohen, Byrne Fone, Michael Moon, and Thomas Yingling) have

explored, the homophobia of our dominant culture must be seen not just

63. See Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet, in particular "Proust and the Spectacle of

the Closet," p. 222.

64. When this paper had already been written, Patricia Hills drew my attention to the

work ofJonathan Katz, who has come to similar conclusions about such works by Johns and

Rauschenberg. To my knowledge, Katz's paper has yet to be published; it was delivered at

the 1991 College Art Association conference in Washington, D.C., as "Subculture Repre-

sentations in the Art of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg: Identity and Community

among Postwar New York Artists." See also my chapter on Warhol for a discussion of his

homosexual aesthetic in "Machine in the Studio."

65. Even Howl was censored in its first publication, the overt homoerotic pas

altered. See my Bay Area Figurative Art, p. 135.

66. Quoted in Mark Rosenthal, Jasper Johns: Work since 1974 (exhibition catalog

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, 23 Oct. 1988-8 Jan. 1989), p. 60.

67. Tomkins, Off the Wall, p. 260, speaking of "Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenb

Johns, Warhol and others."

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.12 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 16:51:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Critical Inquiry Summer 1993 653

in political terms, as one body politic striving to deprive other collectivities

of political influence. It must also be read as a cultural text; homosexuality

then becomes the unconscious within that text, the ultimate difference

that must be repressed in order to achieve a national, literary, or visual

American tradition. Homosexuality "becomes the unconscious ... , that

which the text may not speak, for as a discourse it contradicts the very

things [it] is called into being to address." 68For such gay theorists, homo-

sexuality is not some essentialist discourse based on bodily sex acts; it is

discursively produced by "gay" and "straight" alike as a negativity within a

dominant heterosexist culture.69 It is this negativity that I want to explore

in the work of John Cage.

What is the connection, then, between Cage's famous silences (which

contain so much that they are pregnant with unheard sounds) and these