Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope's Construct of Foreign Language Anxiety

Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope's Construct of Foreign Language Anxiety

Uploaded by

hoshmin aliCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope's Construct of Foreign Language Anxiety

Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope's Construct of Foreign Language Anxiety

Uploaded by

hoshmin aliCopyright:

Available Formats

Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope's Construct of Foreign Language Anxiety:

The Case of Students of Japanese

Author(s): Yukie Aida

Source: The Modern Language Journal , Summer, 1994, Vol. 78, No. 2 (Summer, 1994),

pp. 155-168

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the National Federation of Modern Language Teachers

Associations

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/329005

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/329005?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

National Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations and Wiley are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Modern Language Journal

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz,

and Cope's Construct of Foreign

Language Anxiety: The Case of

Students of Japanese

YUKIE AIDA

Department of Oriental and African Languages and Literatures

University of Texas at Austin

2601 University Avenue

Austin, TX 78712

Email: aida@ccwf cc.utexas.edu

THE PRESENT STUDY CONCERNS HOW Lambert, it requires approximately 1320 hours

language anxiety is related to Japanese lan-in an intensive program in lan-

of instruction

guage learning. It uses Horwitz, Horwitz, and

guages like Japanese, Arabic, Chinese, and Ko-

Cope's theoretical model of foreign

rean language

to bring students to the same level of profi-

anxiety as a research framework. It has been

ciency reached after only about 480 hours of

reported that foreign language instruction

anxiety in is languages

a like French or Spanish.

rather pervasive phenomenon (14; 31; 32; 46;the

Therefore, 47;experiences that students have in

52). Although language anxiety could the be viewed

classroom with such difficult languages may

as positive energy (or facilitating be anxiety

different fromas the experiences of students in

called by Alpert and Haber) that languages motivates that are more similar to English.

learners, many language teachersDo and re- of Japanese feel anxious in their

students

searchers have been concerned about classrooms? If so, what are the sources of their

the possi-

bility that anxiety may function asanxiety? an affective

Are there gender differences in lan-

filter (28), preventing a learner from guageachieving

anxiety? Does anxiety interfere with their

a high level of proficiency in a foreign learninglanguage

ofJapanese? The present study was de-

(4; 7; 17; 25; 27; 39; 42; 56; 62). However, signed to most

answerofthese questions.

the research studies have involved Western lan- Due to the importance of the economic and

guages such as French, German, Spanish, and

political relationship between the US and Ja-

English, and there has been little investigation

pan, the number of students interested in learn-

of non-Western languages like Japanese.ing In Japanese has been growing at a rapid pace.

order to develop a fuller understanding of the

According to the results of the fall 1990 survey

nature of language anxiety and its implications

conducted by the Modern Language Associa-

for language education, future research should

tion, 45,717 college students were studyingJapa-

include non-Western languages. This study nese in United States institutions of higher edu-

takes a step in that direction. cation in 1990, representing a spectacular

As a Japanese educator, the author became increase of 94.9% from 1986 when 23,454 stu-

very interested in exploring the role of anxiety

dents were registered in Japanese language

in Japanese language learning among college

courses (6). Japanese became the fifth most

students. Learning Japanese is a very difficult

commonly taught language in 1990, rising from

task for Americans. According to Jorden and seventh position in 1986. Therefore, it is impor-

tant for language educators to identify the vari-

ables that may increase or decrease retention

and success in Japanese language learning. Lan-

The Modern LanguageJournal, 78, ii (1994)

0026-7902/94/155-168 $1.50/0

guage anxiety is one of these important

variables.

?1994 The Modern Language Journal

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

156 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

EARLY RESEARCH ON

that anxiety is not associated with achievement,

FOREIGN LANGUAGE ANXIETY

because we do not know whether the anxiety

measures

Early research on the role of anxiety in for- used in Young's study could accu-

eign language learning failed to demonstrate

rately capture students' anxiety levels in oral

any clear-cut relationship between anxiety and

production.

a learner's achievement in a foreign language.

For example, Chastain examined the relation-

HORWITZ, HORWITZ, AND COPE'S

ships between anxiety and course grades in

CONSTRUCT OF LANGUAGE ANXIETY

three language programs: French (audiolingual

or regular), German, and Spanish. While Horwitz

there (24) and Horwitz et al. have attrib-

was a significant negative correlation found be- inconclusive results of previous re-

uted the

tween course grades and test anxietysearch

in the

to the lack of a reliable and valid meas-

French audiolingual class, students in the ure of anxiety specific to language learning.

regu-

lar French, German, and Spanish classes They who

conceptualize foreign language anxiety as

experienced a higher level of anxiety were more

"a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs,

likely to receive better grades than students feelings, and behaviors related to classroom lan-

with a lower level of anxiety. Backman looked at

guage learning arising from the uniqueness of

the relationship between anxiety and language the language learning processes" (25: p. 31).

progress among Venezuelan students learning The Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale

English in the US. Students' progress measured (FLCAS, hereafter) was developed by Horwitz

by a placement test, a listening comprehension (24) in order to capture this specific anxiety

test, and teachers' ratings did not showreaction a sig- of a learner to a foreign language

nificant correlation with any of the learning anxiety setting. Horwitz et al. integrated three

measures.

related anxieties to their conceptualization of

In Kleinmann's 1977 study of Spanish-speak-

foreign language anxiety, i.e., communication

ing and Arabic-speaking ESL students, apprehension (35), test anxiety (19; 50), and

facilitat-

ing anxiety was found to be correlated fear of negativewith stu- (58).

evaluation

dents' oral production of linguistically According to McCroskey (34), communica-

difficult

(thus challenging) English structures (e.g.,is in-

tion apprehension defined as a person's level

finitive complements and passive of fear orsentences).

anxiety associated with either real or

However, there was no evidence that debilitat- anticipated communication with another per-

ing anxiety negatively influenced oral perfor- son or persons. McCroskey (33) points out that

mance. The facilitating and debilitating effects typical behavior patterns of communicatively

of anxiety were also observed by Bailey through apprehensive people are communication avoid-

her review of students' diaries. ance and communication withdrawal. Com-

Young (62) conducted a study to test whether pared to nonapprehensive people, commun

oral proficiency was negatively influencedcativelyby apprehensive people are more reluctan

anxiety in three languages, i.e., French, to Ger-

get involved in conversations with others an

man, and Spanish. She found some negative to seek social interactions. The extensive body

correlations between students' OPI (Oral Profi- of research in this area, summarized by Da

ciency Interview) scores and some of the anxi- and Stafford and by Richmond, supports Mc

ety measures. However, when language ability Croskey's claim. In 1985 McCroskey, Fayer, an

Richmond studied the relationships betwee

measured by a dictation test and a self-appraisal

measure of foreign language oral proficiency communication apprehension and self-perceive

competence in Spanish and English among

was controlled statistically (i.e., the variability

due to language ability was removed from Spanish-speaking

the Puerto Rican college stu-

relationship between anxiety and oral perfor- dents who had received instruction in Englis

mance), the correlations between anxiety meas- They found that students with low self-ratings

ures and OPI scores were nonsignificant. Such competency in English were more likely to r

port higher levels of English communicatio

results are very predictable since language abil-

apprehension. On the other hand, there was n

ity is likely to correlate with language achieve-

ment. When language ability is held constant suchas correlation found between self-perceive

was done in Young's (62) study, there is little competence

left in the native language, i.e., Span-

in the OPI scores to covary with anxiety. How- ish and Spanish communication apprehension

ever, these nonsignificant correlations obtainedSimilarly, Foss and Reitzel and Lucas report th

through the above procedure cannot warrant communication anxiety exists among student

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Yukie Aida 157

in the ESL classroom; it seems to function as a evaluation is applied to foreign language

block for students' mastery of English. It is very learners, we can easily imagine that students

likely that people experience anxiety and reluc- with fear of negative evaluation sit passively in

tance in communicating with other people or in the classroom, withdrawing from classroom ac-

expressing themselves in a foreign language in tivities that could otherwise enhance their im-

which they do not have full competence. provement of the language skills. In extreme

The second element of foreign language anx- cases, students may think of cutting class to

iety, test anxiety, is defined by Sarason (51) as avoid anxiety situations, causing them to be left

"the tendency to view with alarm the conse- behind. Horwitz et al. believe that these three

quences of inadequate performance in an eval- anxieties, i.e., communication apprehension,

uative situation" (p. 214). Students worry about test anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation, are

failing to perform well. Culler and Holahan and important parts of foreign language anxiety

other researchers (22; 60) speculate that test and have an adverse effect on students' lan-

anxiety may be caused by deficits in students' guage learning.

learning or study skills. Some students experi- Horwitz (23) reported that the FLCAS had

ence anxiety during a test situation because correlation coefficient of .28 (p = .063, n = 4

they do not know how to process or organize the with communication apprehension (measur

course material and information. Since daily by McCroskey's Personal Report of Communic

evaluations of skills in foreign language class- tion Apprehension, 35), .53 (p < .01, n = 6

rooms are quite common, and making mistakes with test anxiety (measured by Sarason's Tes

is a normal phenomenon, students may suffer Anxiety Scale, 51), and .36 (p < .01, n = 56) wi

stress and anxiety frequently, which may pose a fear of negative evaluation (measured by Wa

problem for their performance and future im- son and Friend's Fear of Negative Evaluati

provement. Other researchers posit that test Scale). The FLCAS also correlated with final

anxiety occurs when students who have per- grades: r = -.49, p < .01 (n = 35) for two begin-

formed poorly in the past develop negative, ir- ning Spanish classes and r = -.54, p < .01 (n = 32)

relevant thoughts during evaluation situations for two beginning French classes. Higher

(40; 49; 59). Test-nervous students may not be FLCAS scores were associated with lower final

able to focus on what is going on in the class- grades. Price also reported in her dissertation

room because they tend to divide their atten- that the FLCAS scores of 106 students of

tion between self-awareness of their fears and second-semester French classes were posit

worries and class activities themselves.correlated They with test anxiety (r = .58, p <

may say to themselves, "I'll never be able to and public speaking anxiety (r = .43, p < .

pro-

nounce it correctly," "The teacher is ready The to FLCAS scores also correlated negat

correct me," or "Other students will laugh withat final grades (r = -.22, p < .05), final

me if I speak." They become distracted and (r = -.29, p < .01), and oral exam sc

scores

anxious during class, which interferes with(rtheir = -.27, p < .05). However, when stud

performance. Modern Language Aptitude Test scores

Lastly, fear of negative evaluation is definedcontrolled, only the correlation between

as "apprehension about others' evaluations, oral exam scores and the FLCAS scores re-

dis-

tress over their negative evaluations, andmained the significant.

expectation that others would evaluate oneself The main purpose of this study was to te

negatively" (58: p. 449). Research shows that

Horwitz et al.'s construct of foreign langu

people who are highly concerned about the im-

anxiety by validating an adapted FLCAS for

pressions others are forming of them tend dentsto ofJapanese. It was an exploratory stud

behave in ways that minimize the possibility discover

of the underlying structure of the FL

unfavorable evaluations. They are more likely and totoexamine whether or not the structure

avoid or prematurely leave social situations in

reflects the three kinds of anxiety presented

which they believe others might perceive earlier. them It also assessed the instrument's re-

unfavorably (29; 57; 58; 63). When they affiliateliability and the relationship of students' anx

with others, they often fail to initiate conversa-

ety levels to their performance in Japanese. I

tions or participate only minimally in the wascon-hoped that the results of this empiric

versation, as by just smiling and politelystudy nod- using a non-Western language woul

ding, or listening to others talk and only shed new light on the concept of foreign lan

interacting with occasional "uh-huh's" guage (8; 30; anxiety and would expand its scope and

43; 45). When this notion of fear of negative implications.

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

158 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

METHOD

agree", to (c) "neither agree nor disagree", to

(e) "strongly agree". A student's endorsement

in (a) were

Subjects. In the fall of 1992, students who "strongly disagree" was equated with a

enrolled in second-year Japanese I at the Uni-

numerical value of one; (b) "disagree" was two;

versity of Texas at Austin were asked to partici-

(c) "neither agree nor disagree," three; (d) "agree"

pate in this study. Ninety-six students four; and, (e) "strongly agree" was five.

(fifty-six

males and forty females) completed theFor ques-

each subject, an anxiety score was derived

tionnaires designed for this study. There

by summing

were his or her ratings of the thirty-

more than ninety-six students enrolled threein items.

the When statements of the FLCAS

were negatively

course, but some students failed to complete the worded, responses were re

versedstu-

questionnaires or to pass the course. Three and recoded, so that in all instances, a

dents did not pass the course because highthey

score represented high anxiety in theJapa-

nese classroom. The theoretical range of this

failed to attend class regularly and to complete

several important exams and/or assignments

scale was from thirty-three to 165.

(e.g., lesson quizzes, essay writing, oral The background questionnaire included

presen-

tation). Therefore, only data obtained fromon the student's age, sex, ethnicity,

questions

these ninety-six students were used foracademic

analysis.major and status, native language,

The mean age of this sample was 21.5 years.

reasons why he or she was taking a Japanese

There were sixty-four native speakers of course, whether or not he or she had been to

English

and thirty-two non-native speakers of Japan

English

and for how long, whether or not he or

(i.e., five Spanish speakers, six Chinese,shefour-

was pleased with the final course grade

teen Korean, five other Asian language given for the second-semester Japanese class,

speakers,

and two other non-Asian language speakers).

and whether or not he or she had other family

When the native speakers of English and members

non-who speak Japanese.

native speakers of English were compared Instructors

on provided subjects' final course

grades (in

the level of anxiety (see the Procedures section percentages) for the second-semester

for

how to obtain a subject's anxiety score), Japanese

a one-classes. The final course grade was se-

way ANOVA showed that there was no lected primarily because it had been used as a

signifi-

cant difference between the two groups: global measure of language proficiency by

F(1, 94) = .07, p = .79, X = 96.2 for native many researchers (e.g., 7; 9; 18; 25; 55).

speakers of English and X = 95.5 for non-native

speakers of English). In addition, a Bartlett-Box RESULTS

F test for homogeneity of the variance indicated

that the data of the present study satisfied the Reliability of the FLCAS. The present study,

assumption of equal variances: F = 1.21, p = .27. using ninety-six students ofJapanese, yielded in

Therefore, the two groups were treated as one ternal consistency of .94 (X = 96.7 and s.d. = 22.1)

sample. using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. As shown in

Procedures. On the very first day of the fall Table I, the reliability, mean, standard devia-

semester 1992, subjects were asked to complete tion, and range obtained in this study were ver

both a FLCAS and background questionnaire similar to those of Horwitz (23), who used stu-

(see Appendix). In this study, the term "for- dents enrolled in an introductory Spanish class

eign language" used in the original FLCAS The mean of this study, 96.7, was slightly higher

was replaced with "Japanese language." In re- than that of Horwitz's (23) study, X = 94.5. It i

sponding to the statements on the FLCAS, understandable that students may feel mor

subjects were asked to consider their experi- anxious in learning a non-Western, foreign lan

ences in the previous year's first-year Japanese guage like Japanese (26) than in learning com-

course. Therefore, students' FLCAS scores re- monly taught Western languages such a

flect their anxiety in the first-year Japanese Spanish.

classroom. The instructions read as follows: There was no significant gender difference

"In this section, we would like you to respond found in language anxiety: t(94) = .41, p = .69.

to each of the following statements based upon The mean scores for males (n = 56) and females

(n = 40) were 97.4 and 95.6, respectively. The

your experience in your last year's Japanese course

(JPN507). " results of this study suggest that the FLCAS is a

Instruments. The FLCAS contains thirty-three reliable tool regardless of whether the language

items, each of which is answered on a five-point is a European Western language.

Likert scale, ranging from (a) "strongly dis- On the first day of the next semester (spring

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Yukie Aida 159

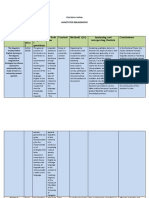

TABLE I nalities, and percent of the variance are shown

Reliabilities of The FLCAS in Two Studies in Table III. The solution accounted for 54.5%

Horwitz

of the total variance. Eighteen items were

loaded on the first factor, accounting for 37.9%

Present study et al., 1991

of the variance. Examples of the items included

Sample size 96 108 in this factor are item 3, "I tremble when I know

Students status first year first year

that I'm going to be called on in my Japanese

Language Japanese Spanish class," and item 13, "It embarrasses me to volun-

Cronbach's alpha .94 .93

Range 47-146 45-147 teer answers in my Japanese class." The factor

Mean 96.7 94.5 one was assigned a label of Speech Anxiety and

Standard 22.1 21.4 Fear of Negative Evaluation. The items in-

deviation cluded in this factor indicate a student's ap-

Test-retest r = .80, p < .01 r = .83, p <.01 prehension in speaking in aJapanese class and

reliability (n = 54; over (n = 108; over fear of embarrassment in making errors in

one semester) eight weeks) front of other students (see Table II). Two

items, 8 and 18, were negatively loaded on this

factor. In other words, item 8, "I am usually

1993), students who had passed second-year

Japanese I and were enrolled in second-year

at ease during tests in my Japanese class," and

Japanese II were asked to complete the FLCAS item 18, "I feel confident when I speak in my

again. Fifty-four students (thirty-one males Japanese

and class," are negatively associated with

twenty-three females) responded. Their two factor one. Unlike the speculation of previous

FLCAS scores were correlated to obtain test- researchers (e.g., 34; 58), speech anxiety and

retest reliability over one semester. Thefear of negative evaluation may not be totally

correla-

tion between the FLCAS scores in the fall and independent concepts, but rather are probably

those in the spring was .80, p < .01, ndifferent

= 54, labels describing one phenomenon

in a language learning situation. In their

indicating that the FLCAS measures a person's

factor analysis of various anxiety measures,

level of anxiety with high accuracy at different

times. This high correlation suggests that MacIntyre

the and Gardner (37) reported that

FLCAS may tap a person's persistent traitMcCroskey's

anxi- Personal Report of Communica-

tionlan-

ety (as called by Spielberger) in the foreign Apprehension measure (34) and Watson

guage classroom and not a temporary et condi-

al.'s Fear of Negative Evaluation measure

tion of state anxiety that is triggeredloaded

by a on the same factor. Their findings

specific moment or situation. are in accordance with those of the present

Factor Analysis. The second analysis was per-

study.

formed to detect an underlying structure of Thethe

second factor included four items (i.e., 10,

FLCAS's thirty-three items, i.e., students' 25, 26,

rat-and 22) and accounted for 6.3% of the

ings of the original (unreversed and unre- variance. Item 22 was negatively loaded on this

coded) thirty-three statements. Principal factor.

com- The author named this factor "Fear of

ponents analysis with varimax rotation was the Class" and considered that it showed

Failing

performed on the thirty-three items. Orthogo- a student's worry and nervousness about being

nal rotation was used because of the conceptual left behind in the class or failing the class

simplicity and ease of description. The initial altogether.

run produced seven factors with eigenvalue Items 32, 11, and 14 comprised the third fac-

greater than one. In a rotated matrix, however, tor, accounting for 5.6% of the variance. It was

there were only four factors with SSLs (the sum "Comfortableness in Speaking with Jap-

labeled

of squared loadings, which is equal to theanese eigen- People" by the author. In the interview

value in the unrotated matrix) greater withthan Young (61), Krashen says that foreign lan-

one. Therefore, the subsequent analysis spec-

guage learners need to think of themselves as

ified the number of factors as four. With a fac- the kind of people who speak the foreign lan-

tor loading of .50 (twenty-five percent of the guage very well. This idea is similar to Gardner'

variance) as a cutoff for inclusion of a variableconcept of integrativeness. It is likely that indi-

in interpretation of a factor, six items (itemsviduals

2, who do not see the language as truly

6, 15, 19, 28, and 30, see Table II) did not loadforeign and feel comfortable with the native

on any factor. None of the items loaded on more speakers of the language have a lower filter of

than one factor with a loading of .50 or greater.anxiety.

Loadings of variables on factors, commu- Lastly, two items, 5, "It wouldn't bother me at

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

160 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

TABLE II

FLCAS Items with Percentage of Students Selecting Each Alternative in Four Factors

SAa A N D SD

Factor One (Speech Anxiety and Fear of

3d I tremble when I know that I'

7b 24 20 35 14

13d It embarrasses me to volunteer answ

5 20 19 35 21

27 I get nervous and confused when

4 27 24 38 7

20d I can feel my heart pounding

8 28 21 28 15

24c I feel very self-conscious about

10 35 18 28 8

31d I am afraid that the other stu

3 12 13 45 28

7d I keep thinking that the other s

16 28 26 22 8

12 In Japanese class, I can get so

12 32 17 35 4

23d I always feel that the other stud

9 26 21 34 9

18c,f I feel confident when I speak

7 27 28 32 5

33c I get nervous when the Japan

12 44 21 23 1

16 Even if I am well prepared for

9 35 21 24 10

1 I never feel quite sure of mysel

14 28 13 34 12

21 The more I study for a Japanese

1 6 10 43 40

29c I get nervous when I don't u

6 27 23 37 7

4c It frightens me when I don't und

8 48 15 21 8

8f I am usually at ease during t

12 28 13 39 9

9c I start to panic when I have to s

14 32 23 22 9

Factor Two (Fear of Failing the Class)

10 I worry about the consequences

30 27 8 18 17

25 Japanese class moves so quickly I w

18 40 9 24 9

26 I feel more tense and nervo

23 29 12 23 14

22f I don't feel pressure to prepare ver

27 45 12 13 3

Factor Three (Comfortableness in Speaking

32 I would probably feel comfortab

5 26 42 19 8

11 I don't understand why some

6 35 33 21 4

14 I would not be nervous speak

10 47 19 17 7

Factor Four (Negative Attitudes Toward the

5f It wouldn't bother me at all to ta

1 5 14 35 45

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 , 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Yukie Aida 161

SAa A N D SD

17 I often feel like not going to

2 15 11 47 25

Items Not Included in the Factor Solution

2e I don't worry about making mistakes in my Japanese class.

16 47 12 19 7

6e During Japanese class, I find mys

course.

3 12 21 43 22

15 I get upset when I don't under

4 39 29 26 2

19e I am afraid that my Japanes

3 12 26 48 12

28 When I'm on my way to Jap

3 19 41 29 8

30 I feel overwhelmed by the n

5 35 22 29 8

aSA = strongly agree; A = agree

bPercentages in this table are ro

cItems that are classified by Hor

dItems that are classified by Hor

eltems that are classified by Hor

fltems that were negatively load

TABLE III

Factor Loadings, Communalities (h2), Percents of Variance for Four-Factor Principal

Analysis with Varimax Rotation on FLCAS Items.

Label Speech Fear of Comfort- Negative

Label Speech Fe

Anxiety Failing ableness Attitudes Anxiety Failin

with JPN with JPN

Item Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 h2 Item Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 h2

Item 3 .77 .69 Item 8 -.56 .48

Item 13 .76 .61 Item 9 .54 .49

Item 27 .75 .73 Item 10 .72 .54

Item 20 .73 .67 Item 25 .53 .60

Item 24 .73 .66 Item 26 .51 .56

Item 31 .71 .53 Item 22 -.51 .46

Item 7 .71 .60 Item 32 .74 .62

Item 12 .69 .58 Item 11 .60 .41

Item 23 .69 .57 Item 14 .59 .45

Item 18 -.67 .70 Item 5 -.77 .65

Item 33 .60 .42 Item 17 .73 .59

Item 16 .60 .59

% of

Item 1 .58 .60

variance 37.9 6.3 5.6 4.7

Item 21 .58 .53

Item 29 .57 .54 % of total variance accounted for

Item 4 .56 .62 solution 54.5

all more

In toJapan

their revie take

and often 17,

feel and

anxiety like l "I

nese class," constituted

Gardner the

(38)

was negatively loadedas

develops on a t

explained 4.7% of

studentthe

mayva

"Negative Attitudes

learningTowar

a new

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

162 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

supports their hypothesis. Students' beyond the required classes and that at-

negative the attri-

titudes toward the language tionclass

rate mightcanbe highcontrib-

at a transition point

ute to their overall levels of from foreign language

a lower division class to an upper division

anxiety. class'.

The factor solution of the present study pro- The Relationship between Anxiety and Perfor-

vided partial support for Horwitz et al.'s con- mance. In the subsequent analysis, the relation-

struct of foreign language anxiety. It has shown ship between foreign language anxiety and stu-

evidence that speech anxiety and fear of nega- dents' performance was investigated. First, the

tive evaluation are indeed important compo- correlation coefficient between anxiety and

nents of foreign language anxiety. Yet the pres- course grade was calculated with a Pearson

ent study did not support Horwitz et al.'s claim product-moment correlation. It produced a

that test anxiety is the third component of for- moderate negative correlation (r = -.38, p < .01)

eign language anxiety. Items 2, 6, and 19 which indicating that the higher the students' levels of

were considered by Horwitz et al. to be indica- anxiety, the more likely they are to receive low

tive of test anxiety, failed to load on any of the grades. For the second analysis, each student

factors. In addition, eighty-three percent of the was classified into either a high anxiety group

students rejected statement 21, "The more I or a low anxiety group by a median split pro-

study for a Japanese test, the more confused I cedure, based upon his or her total score on the

get." The subjects of the present study seem to FLCAS. The median score of anxiety for this

be less intimidated by the Japanese tests. These sample was ninety-five. A two by two ANOVA

findings are congruent with the results ob- was conducted using anxiety (high vs. low) and

tained by MacIntyre and Gardner (39), who gender (males vs. females) as the independent

found that test anxiety did not contribute to the variables and final course grade as the depen-

communicative anxiety of the language class- dent variable. There was a significant main effect

room. They concluded that test anxiety was a of anxiety: F(1, 92) = 7.35, p < .01 (see Table IV).

general anxiety problem; it was not specific to The high anxiety group received significantly

foreign language learning. Based on these find- lower grades (X = 85.6) than the low anxiety

ings, it appears clear that test anxiety is not con- group (X = 89.8). While students having a high

ceptually related to other components of foreign anxiety level were more likely to receive a grade

language anxiety as Horwitz et al. proposed, of B or lower, those with a low level of anxiety

and that items reflective of test anxiety could be were more likely to get an A.

eliminated from the FLCAS. Speech anxiety It was also found that there was a significant

and fear of negative evaluation are considered effect of gender on course grade: F(1, 92)

as relatively enduring personality traits (41), = 4.74, p < .05. Female students scored higher

whereas test anxiety is regarded as a state (X = 89.7) than did males (X = 86.1)2. There was

marked by temporary reactions (e.g., worry and no significant anxiety-gender interaction effect

nervousness) to an academic or evaluation situ- on course grade: F(1, 92) = 3.20, p > .05. In both

ation (51). This distinction might also partially male and female groups, highly anxious stu-

explain the results of this factor analysis. The dents were more likely to receive lower grades

present study suggests that other factors such as than students having a low level of anxiety.

a student's fear of failing the class, comfortable-

ness in speaking with native speakers of the lan-

TABLE IV

guage, and negative attitudes toward the lan-

Anxiety by Sex ANOVA Results on Achievement

guage class influence the level of anxiety in the (N = 96)

foreign language classroom.

The results show that a fair amount of anxiety Sum of Mean Sig.

exists in the Japanese classroom. A third or Source Squares df Squares F of F

more of the students in the sample showed anxi- Main Effects

ety agreement with items reflective of foreign Anxiety 376.6 1 376.6 7.35 .008

language anxiety. There were six items (4, 5, 10, Sex 243.1 1 243.1 4.74 .032

25, 26, and 33) that were endorsed by over half Interaction

of the students. Eighty percent of the students Anxiety

disagreed or strongly disagreed with statement 5, by sex 164.1 1 164.1 3.20 .077

"It wouldn't bother me at all to take more Japa-

Residual 4715.2 92 51.3

nese language classes." This suggests that stu- Total 5551.0 95 58.4

dents may be less likely to take a Japanese class

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Yukie Aida 163

students who are feeling good about

Association Bettheir

Data. grades are likely

A seriesto experience lower anxiety

ductedthan those

to who are not happy with their grades.

inves

language anxie

data.

DISCUSSION

Elective vs. Required Status. Students were clas-

sified into one of three groups: 1) Required The adapted Foreign Language Classroo

Group, including forty-one students who were Anxiety Scale was found to be a highly rel

taking the Japanese class to satisfy the univer-instrument to measure the anxiety level of

sity's language requirement, 2) Elective Group, dents learning Japanese in a college setting

including forty-four students who were taking ified by the University of Texas at Austin.

tors that had an impact on students' anxiety

the Japanese class for personal interest or enjoy-

ment, and 3) Major Group, including eleven learning Japanese were speech anxiety and

students who are majoring in Japanese or in of negative evaluation, fear of failing the J

nese class, degree of comfort when spea

Asian Studies with specialization in Japanese.

An ANOVA result shows that there were no dif- with native speakers of Japanese, and nega

ferences in anxiety among the three groups:

attitudes toward the Japanese class. In the p

F(2, 93) = 2.64, p > .05. However, when theent

Ma-sample of students ofJapanese, test anx

jor Group was removed from the analysis wasand not a factor contributing to students'

the Required Group was compared witheign

the language anxiety. The factors that w

Elective Group in the anxiety level, an ANOVAfound important in this study for explaining

yielded a significant difference: F(1, 83) = construct

5.5, of foreign language anxiety appea

p < .05. The Required Group had a significantly

support views of language anxiety propose

higher level of anxiety (X = 99.6) than the scholars

Elec- such as MacIntyre and Gardner

tive Group (X = 93.1). and Krashen and Terrell (cited in 61).

Consistent with research findings using W

Experience in Japan. Comparison in the anxiety

level was made between students who had been ern languages like French, German, and Sp

ish (e.g., 25; 32; 47; 55), language anxiety

to Japan (n = 36) and those who had never been

to Japan (n = 60). The result of a one-way found to be negatively related to students'

formance in Japanese. A recent article b

ANOVA was significant: F(1, 94) = 4.0, p < .05.

Gardner and MacIntyre reports that "the b

Those with experience in Japan showed a signif-

single correlate of achievement is Langu

icantly lower level of anxiety in the classroom

Anxiety" (p. 183). The author intends to ex

(X = 92.5) than those who had not been to Japan

(X = 98.1). Exposure to culture and peopleine in in a future study whether the Gardner

Japan may be a factor for this group difference.

MacIntyre statement stands true for the sa

of students studying Japanese. The pres

Family Who Speaks Japanese. There were twenty-

four students who had a family member with a

study used final course grades as the depend

command of Japanese. The anxiety levelsvariable

of to examine the relationship betw

these students were compared with the anxiety anxiety and language achievement. Since

levels of students whose family members did FLCASnot appears to measure anxiety prima

speak Japanese (n = 72). There was no anxiety related to speaking situations, use of a spec

difference found between the two groups: measure of oral skills may yield more profo

F(1, 94) = .1, p = .77. The presence of a familyrelationships between language anxiety

member who speaks Japanese does not seemachievement.

to

be related to the individual's level of anxiety in Although the present study was successful in

the Japanese classroom. producing partial support for the findings of

previous research studies using Western lan-

Satisfaction with Grade in Japanese. Sixty-nine

students indicated that they were pleased with guages, certain limitations of this study need to

the grade they received for the second semester be considered. First of all, the subjects were

of first-year Japanese. Twenty-seven students only those who had completed two semesters of

said that they were not pleased. A comparison Japanese. A study using students with a longer

of the anxiety levels of these two groupshistory re- ofJapanese language learning may pro-

vealed a significant difference: F(1, 94) = 12.7,

duce different results. In their 1991 article, Mac-

p < .01. Satisfied students exhibited a much Intyre and Gardner (38) cited the results of sev-

lower level of anxiety (X = 93.1) than non- eral studies, indicating that as "experience and

satisfied students (X = 103.4). It appears that proficiency increase, anxiety declines in a fairly

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 20Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

164 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

consistent manner" (p. 111).dents' needs, language

Therefore, teachers can make it

anxiety

may play a different role in foreign

possible for anxious language

students to maximize their

learning for advanced students.

language learning by building a nonthreaten-

Secondly, subjects of this study were

ing and positive asked

learning to

environment, as well

recall their experiences in as

the first-year

by helping them acquire Japa-

effective study and

nese classes and to indicate learning

theirstrategies.

feelings about

those classes. There was a threeHowever, month gap anxiety

foreign language be- may not

tween the time when they be completed

alleviated simplythe

throughfirst-

certain teaching

year course (spring 1992) and the time

methodologies. Comeauof their

points out in her thesis

anxiety assessment (fall 1992). For some

that the Natural Approach stu-

(54) which is de-

dents, the strong anxiety reactions signed to lessen anxietyhad

they in theex-

classroom has

perienced in the first-year not been proven

class may successful

have been in achieving this

lessened by fall 1992. Therefore, goal. In the studyaccuracy

the done by Koch andof Terrell in

their recall of their anxiety 1991experience

(cited by Comeau), cannot

sixty percent of their

be completely guaranteed. subjects with previous classroom language

Thirdly, readers should interpret study indicatedthe results

that they felt more anxious or

of the factor analysis, keeping equally

the anxious under the Natural

following lim- Approach

itation in mind. The size of the variances for than under other methods. In her own study,

factors, two, three, and four was very smallcompared the anxiety levels of two

Comeau

(6.3%, 5.6%, 4.7%, respectively), comparedgroupstoof Spanish students: one hundred stu-

that of factor one, speech anxiety and fear

dents of

attending a school that uses the Natural

evaluation (37.9%). This suggests the possibility

Approach and 116 students attending a school

that there was actually no more than onethat uses an eclectic/proficiency-based ap-

mean-

proach.

ingful factor in the present data. This study didThere was no significant difference in

not perform a data transformation to reduce

the level of anxiety between students in the two

potential skewness in distributions of theschools,

items.indicating no special advantage of the

If there were some items with skewed distribu- Natural Approach over other methods in reduc-

tions, the results could have been different. ing the anxiety levels of students. She suggested

Lastly, readers should note that due to the that anxiety interacts with learner variables

correlational nature of this study, the results of such as students' expectation of grades and

the ANOVA do not prove that a cause-effect their own perception of language ability rather

relationship exists between anxiety and achieve- than with methodology itself.

ment in Japanese. It is possible that some uni- Therefore, future research should look into

dentified variables caused high anxiety and low potential interactions between anxiety and

achievement among students of Japanese. For other student characteristics such as learners'

example, a student's help-seeking behavior may beliefs about their own language ability, self-

influence both anxiety and achievement. Stu- esteem, help-seeking behaviors, and knowledge

dents who are not comfortable in seeking help and use of language learning strategies. Anx-

from their instructors or teaching assistants ious students may be anxious in the classroom

may experience a high level of anxiety in the because they may not know how to ask ques-

classroom; and their failure to seek help may, in tions to clarify their assignments or how to

turn, result in lower levels of achievement. organize and process information to enhance

The findings of the present study and those their understanding of the material. Some stu-

of other language researchers suggest the im- dents may need assistance from the instructor,

portant role of teachers in lessening classroom but do not ask for help because they might view

tension and in creating a friendly, supportive help-seeking as a manifestation of weakness,

atmosphere that can help reduce students' fear immaturity, or even incompetence. They might

of embarrassment of making errors in front of feel lost in the language classroom and anxious

peers. Students will appreciate and learn more about the teacher discovering their problem.

from teachers who are able to identify students It is also possible that anxious students may

experiencing foreign language anxiety and be able to handle anxiety-provoking situations

take proper measures to help them overcome if they possess high self-esteem. Greenberg and

that anxiety. In 1990, Appleby reported that stu- his colleagues (20; 21) proposed a terror man-

dents are most irritated by teachers who are un- agement theory, which posits that "people are

empathetic with their needs and who are poor motivated to maintain a positive self-image be-

communicators. Being responsive to the stu- cause self-esteem protects them from anxiety"

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Yukie Aida 165

(21: p. 913). A

who are NOTES high i

anxious; and threats to self-esteem cause anxi-

ety. Horwitz et al. noted that foreign language

learning could pose a threat to learners' self- 'The author does not imply that the potentially

esteem because it deprives the learners of their high attrition rate is due solely to language anxiety.

normal means of communication (since mak- could be influenced by other factors. Seniors wou

ing errors are common in the language class- not likely delay their graduation by taking addition

room) and thus of the ability to behave fully as Japanese classes. Many juniors and seniors have

take their major courses and may not have room fo

normal people. Then, people with a sure sense

an extra Japanese course. Some students may be i

of self-worth could manage more effectively the

terested in learning Japanese art, culture, or histor

threats caused by the language learning en- but not necessarily the language.

vironment than those with low self-esteem. In a

2 A possible explanation for this gender differenc

study using a small group (n = 57) of students of

in achievement may be the use of different langua

Japanese, Aida, Allemand, and Kawashima learning strategies by men and women. In their stud

found that students with high anxiety and high involving 1200 college students, Oxford and Nyik

self-competence received slightly higher final found that females reported more frequent use tha

course grades (X = 83.0) and oral skills scores males of three of the five learning strategies studie

(X = 88.7) than did students with high anxiety formal rule-related practice strategies, general stud

strategies, and conversational input elicitation strat

and low self-competence (X = 79.6 for course

gies. On the other hand, males reported no mo

grade and X = 86.0 for oral scores), although

frequent use than females on any of the five strateg

the differences were not statistically significant. categories. Similar gender differences in the use

Among students with high anxiety, those with learning strategies were found in Ehrman and Ox

high self-esteem might be handling their anxi- ford's study using seventy-eight sophisticated la

ety better than those with low self-esteem, re- guage learners as their subjects (e.g., Foreign Servic

sulting in their higher scores on both course Officers, military officers, professional langua

grades and oral skills grades. Future research trainers, and language instructors). Therefore, it

employing a larger number of subjects may be possible that females in the present study might ha

able to produce a clearer pattern of the rela- used more language learning strategies than males a

did the females in the studies by Oxford and her co

tionship between self-esteem and anxiety.

leagues. Greater use of learning strategies may ha

This study focused on issues pertaining to

positively influenced achievement levels for the f

anxiety in Japanese language learning. Since male students in Japanese courses.

the research area of foreign language anxiety is

still young, future investigators have much to

explore. The studies examining the relation-

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ship between anxiety and the learner charac-

teristics mentioned above will help us increase

our understanding of language learning from

the learner's perspective and provide a wider 1. Aida, Yukie, Carolyn Allemand & Hana Kaw

range of insights. shima. "The Role of Anxiety and Social Compe

tence in Japanese Language Learning." Pape

7th International Conference on Pragmati

and Language Learning, Champaign, IL, Apr

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1993.

2. Alpert, Richard & Ralph N. Haber. "Anxiety in Ac-

ademic Achievement Situations." Journal of Ab-

I wish to express my sincere appreciation to Dr. and Social Psychology 61 (1960): 207-15.

normal

Elaine Horwitz, who read an earlier version of this 3. Appleby, Drew C. "Faculty and Student Perceptions

manuscript and provided me with valuable sugges- of Irritating Behaviors in the College Class-

tions, and to Carolyn Allemand, Hana Kawashima, room." The Journal of Staff Program, and Organiza-

and Lin Yan Chan, who assisted me in data coding tion Development 8 (1990): 41-46.

and library research. Preparation of this paper was 4. Backman, Nancy. "Two Measures of Affective Fac-

partially supported by a grant from the Northeast tors as They Relate to Progress in Adult Second

Asia Council of the Association for Asian Studies. Language Learning." Working Papers in Bilingual-

Requests for reprints should be sent to Yukie Aida, ism 10 (1976): 100-22.

Department of Oriental and African Languages and 5. Bailey, Kathleen M. "Competitiveness and Anxiety

Literatures, the University of Texas at Austin, 2601 in Adult L2 Learning: Looking at and through

University Avenue, Austin, TX 78712. the Dairy Studies." Classroom Oriented Research in

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

166 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

Second Language Acquisition. Ed. H.

dence W.

That Seliger

Self-Esteem &an Anxiety Buff-

Serves

M. H. Long. Rowley, MA: Newbury House,

ering Function." 1983:

Journal of Personality and Social

67-103. Psychology 63 (1992): 913-22.

6. Brod, Richard & Bettina J. Huber. "Foreign Lan-21. - , Tom Pyszczynski & Sheldon Solomon.

guage Enrollments in United States Institu- "The Causes and Consequences of a Need for

tions of Higher Education, Fall 1990." ADFL Self-Esteem: A Terror Management Theory."

Bulletin 23, 3 (1992): 6-10. Public Self and Private Self Ed. R. F Baumeister.

7. Chastain, Kenneth. "Affective and Ability Factors New York: Spring-Verlag, 1986: 189-207.

in Second Language Acquisition." Language 22. Hodapp, V. & A. Henneberger. "Test Anxiety,

Learning 25 (1975): 153-61. Study Habits and Academic Performance." Ad-

8. Cheek, Jonathan M. & Arnold H. Buss. "Shyness vances in Test Anxiety Research Vol. 2. Ed. H. M.

and Sociability." Journal of Personality and Social Vander Ploeg, R. Schwarzer & C. D. Spiel-

Psychology 41 (1981): 330-39. berger. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1983: 119-28.

9. Comeau, Jennifer L. "Foreign Language Anxiety23. Horwitz, Elaine K. "Preliminary Evidence for the

and Teaching Methodology." Master thesis., Reliability and Validity of a Foreign Language

Univ. of Texas at Austin, 1992. Anxiety Scale." TESOL Quarterly 20 (1986):

10. Cronbach, LeeJ. "Coefficient Alpha and the Inter- 559-64.

nal Structure of Tests." Psychometrika 6 (1951): 24. . "Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety

297-334. Scale." Unpublished manuscript, 1983.

25. - , Michael B. Horwitz & Jo Ann Cope. "For-

11. Culler, Ralph E. & Charles J. Holahan. "Test Anxi-

ety and Academic Performance: The Effects of eign Language Classroom Anxiety." Language

Study-Related Behaviors." Journal of Educational Anxiety: From Theory and Research to Classroom Impli-

Psychology 72 (1980): 16-20. cations. Ed. Elaine K. Horwitz & DollyJ. Young.

12. Daly, John A. & Laura Stafford. "Correlates and Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1991: 27-39.

Consequences of Social-Communicative Anxi- 26. Jorden, Eleanor H. & Richard D. Lambert. Japa-

ety." Avoiding Communication: Shyness, Reticence, nese Language Instruction in the United States: Re-

and Communication Apprehension. Ed.John A. Daly sources, Practice, and Investment Strategy. Washing-

& James C. McCroskey. Beverly Hills, CA: ton: The National Foreign Language Center,

SAGE, 1984: 125-43. 1991.

13. Ehrman, Madeline & Rebecca Oxford. "Effects of 27. Kleinmann, Howard H. "Avoidance Behavior in

Sex Differences, Career Choice, and Psycho- Adult Second Language Acquisition." Language

logical Type on Adult Language Learning Learning 27 (1977): 93-107.

Strategies." Modern Language Journal 73 (1989): 28. Krashen, Stephen D. Principles and Practice in Second

1-13. Language Learning. New York: Pergamon, 1982.

14. Foss, Karen A. & Armeda C. Reitzel. "A Relational 29. Leary, Mark R. Understanding Social Anxiety: Social,

Model for Managing Second Language Anxi- Personality, and Clinical Perspectives. Beverly Hills,

ety." TESOL Quarterly 22 (1988): 437-54. CA: Sage, 1983.

15. Gardner, Robert C. Social Psychological and Second 30. - , Paul D. Knight & Kelly A.Johnson. "Social

Language Learning: The Role ofAttitudes and Motiva- Anxiety and Dyadic Conversation: A Verbal Re-

tion. London: Edward Arnold, 1985. sponse Analysis." Journal of Social and Clinical Psy-

16. & Peter D. MacIntyre. "On the Measure- chology 5 (1987): 34-50.

ment of Affective Variables in Second Lan- 31. Lucas, Jenifer. "Communication Apprehension in

guage Learning." Language Learning 43 (1993): the ESL Classroom: Getting Our Students to

157-94. Talk." Foreign Language Annals 17 (1984): 593-98.

17. - , Padric C. Smythe, Richard Clement & 32. McCoy, Ingeborg R. "Means to Overcome the

Louis Gliksman. "Second Language Learning: Anxieties of Second Language Learners." For-

A Social Psychological Perspective." Canadian eign Language Annals 12 (1979): 185-89.

Modern Language Review 32 (1976): 198-213. 33. McCroskey, James C. "The Communication Ap-

18. Gliksman, Louis, Robert C. Gardner & Padric C. prehension Perspective." Avoiding Communica-

Smythe. "The Role of the Integrative Motive on tion: Shyness, Reticence, and Communication Appre-

Students' Participation in the French Class- hension. Ed.John A. Daly &James C. McCroskey.

room." Canadian Modern Language Review 38 Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE, 1984: 13-38.

(1982): 625-47. 34. - . "Validity of the PRCA As an Index of Oral

19. Gordon, Edward M. & Seymour B. Sarason. "The Communication Apprehension." Communication

Relationship Between Test Anxiety and Other Monograph 45 (1978): 192-203.

Anxieties." Journal of Personality 23 (1955): 35. - . "Measures of Communication-Bound

317-23. Anxiety." Speech Monographs 37 (1970): 269-77.

20. Greenberg, Jeff, Sheldon Solomon, Tom Pyszczyn- 36. - , Joan M. Fayer & Virginia P. Richmond

ski, Abram Rosenblatt, John Burling, Deborah "Don't Speak to Me in English: Communica

Lyon, Linda Simon & Elizabeth Pinel. "Why Do tion Apprehension in Puerto Rico." Communica

People Need Self-Esteem? Converging Evi- tion Quarterly 33 (1985): 185-92.

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Yukie Aida 167

37. MacIntyre, Pet

McCroskey. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE, 1984: 145-

guage 55.

Anxiety: Its

eties and to

49. Sarason, Irwin Proce

G. "Stress, Anxiety, and Cognitive

Languages." Langua

Interference: Reactions to Tests." Journal of Per-

38. & Robert C. Gardner. "Methods and Re- sonality and Social Psychology 46 (1984): 929-38.

sults in the Study of Anxiety and 50. Language

- . Test Anxiety: Theory, Research, and Applications.

Learning: A Review of the Literature." Language

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1980.

Learning 41 (1991): 85-117. 51. - . "The Test Anxiety Scale: Concept and Re-

39. - & Robert C. Gardner. "Anxiety and Sec- search." Series in Clinical and Community Psychol-

ond Language Learning: Toward a Theoretical ogy. Ed. Charles D. Spielberger & Irwin G. Sar-

Clarification." Language Learning 39 (1989): ason. Washington: Hemisphere Publishing

251-75. Corporation, 1978: 193-216.

40. McKeachie, Wilbert J., Donald Pollie & Joseph 52. Schumann, John H. "Affective Factor and the

Spiesman. "Relieving Anxiety in Classroom Ex- Problem of Age in Second Language Acquisi-

aminations." Journal of Abnormal and Social Psy- tion." Language Learning 25 (1975): 209-35.

chology 50 (1985): 93-98. 53. Spielberger, Charles D. Manual for the State-Trait

41. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes. Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Con-

Ed. John P. Robinson, Phillip R. Shaver & Law- sulting Psychologists Press, 1983.

rence S. Wrightsman. San Diego, CA: Aca- 54. Terrell, Tracy D. "A Natural Approach to Second-

demic Press, 1991. Language Acquisition and Learning." Modern

42. Mettler, Sally. "Acculturation, Communication Language Journal 61 (1977): 325-36.

Apprehension, and Language Acquisition." 55. Trylong, Vicki L. "Aptitude, Attitudes, and Anxi-

Community Review 8 (1987): 5-15. ety: A Study of Their Relationships to Achieve-

43. Natale, Michael, Elliot Entin & Joseph Jaffe. "Vo- ment in the Foreign Language Classroom."

cal Interruptions in Dyadic Communication as Diss., Purdue Univ., 1987.

a Function of Speech and Social Anxiety." Jour- 56. Tucker, Richard E., Else Hamayan & Fred H. Gen-

nal of Personality and Social Psychology 37 (1979): esee. "Affective, Cognitive, and Social Factors

865-78.

in Second Language Acquisition." Canadian

44. Oxford, Rebecca & Martha Nyikos. "Variables Af- Modern Language Review 32 (1976): 214-26.

fecting Choice of Language Learning Strate-

57. Twentyman, Craig T. & Richard M. McFall. "Be-

gies by University Students." Modern Language havioral Training of Social Skills in Shy Males."

Journal 73 (1989): 291-300. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 43

45. Pilkonis, Paul A. "The Behavioral Consequences (1975): 384-95.

of Shyness." Journal of Personality 45 (1977):

58. Watson, David & Ronald Friend. "Measurement

596-611.

of Social-Evaluative Anxiety." Journal of Consult-

46. Powell, Jo Ann C. "Foreign Language Classroom

ing and Clinical Psychology 33 (1969): 448-57.

Anxiety: Institutional Response." Language 59.

Anx-Wine, Jeri D. "Test Anxiety and the Direction of

iety: From Theory and Research to Classroom Implica-Attention." Psychological Bulletin 76 (1971): 92-104.

tions. Ed. Elaine K. Horwitz & Dolly J. Young.

60. Wittmaier, Bruce. "Test Anxiety and Study

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1991: Habits." Journal of Educational Research 46 (1972):

169-76. 929-38.

47. Price, Mary L. "The Subjective Experience of For-

61. Young, Dolly J. "Language Anxiety from the For-

eign Language Anxiety Interviews with High eign Language Specialist's Perspective: Inter-

Anxious Students." Language Anxiety: From Theory views with Krashen, Omaggio Hadley, Terrell,

and Research to Classroom Implications. Ed. Elaine and Rardin." Foreign Language Annals 25 (1992):

K. Horwitz & DollyJ. Young. Englewood Cliffs, 157-72.

NJ: Prentice Hall, 1991: 101-8. 62. - . "The Relationship Between Anxiety and

48. Richmond, Virginia P. "Implications of Quiet- Foreign Language Oral Proficiency Ratings."

ness: Some Facts and Speculations." Avoiding Foreign Language Annals 19 (1986): 439-45.

Communication: Shyness, Reticence, and Communica-

63. Zimbardo, Philip G. Shyness: What It Is, What to Do

tion Apprehension. Ed. John A. Daly & James C. About It. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1977.

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

168 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

Are you taking this course to satisfy the university's

APPENDIX foreign language requirement?

1 YES 2 NO 3 My major (Asian Studies

or Japanese)

Other reasons:

BACKGROUND QUESTIONNAIRE (please print)

What is your native language?

Your Last Name First Name

Are any of your family members of Japanese

heritage?

1 YES 2 NO

Home phone number Work phone number

If yes, who?

Do any of your family members speak Japanese?

1 YES 2 NO

age sex single married children (ages)

If yes, who?

ETHNICITY: Circle one.

Have you been to Japan? 1 YES 2 NO

1 White (not Hispanic) 2 Black (not Hispanic) If yes, how long in total? (Include every occasion

3 Hispanic 4 American Indian or when you were in Japan.)

5 Asian or Pacific Alaskan Native

How many Japanese people do you know

Islander (include 6 Other Specify personally?

Asian Americans) How many of them do you consider as your close

What year are you in? friends?

1 Freshman 2 Sophomore 3 Junior 4 Senior How well do you expect to do in this class?

5 Graduate 6 other Specify (Place a check on the line.)

Double major? 1 YES 2 NO Very Very

If yes, please list your majors / well . ...- poorly

If no, give the name of your single major

Errata

THE MLJ APOLOGIZES FOR MISSPELLING PROFESSORJAVORSKY'S NAME ON HIS AR

in the last issue. The correct spelling appears in the citation below.

Ganschow, Leonore, Richard L. Sparks, Reed Anderson,JamesJavorsky, Sue Skinner &Jon P

"Differences in Language Performance among High-, Average-, and Low-Anxious College Fo

Language Teachers." MLJ78,1 (1994): 41-55.

We would also like to correct the authors of the citation number 51 (page 54). The correct

are Sparks, Richard and Leonore Ganschow.

We thank Leonore Ganschow for bringing these errors to our attention.

This content downloaded from

152.94.26.12 on Fri, 10 Feb 2023 16:54:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- School Leadership Capability Framework - State of NSW, Department of Education and Training - Professional Learning and Leadership Development DirectorateDocument1 pageSchool Leadership Capability Framework - State of NSW, Department of Education and Training - Professional Learning and Leadership Development Directorateadamjohntaylor80% (5)

- Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety PDFDocument9 pagesForeign Language Classroom Anxiety PDFsolsticeangelNo ratings yet

- Beginners Guide On How Speak English Fluently and ConfidentlyDocument12 pagesBeginners Guide On How Speak English Fluently and ConfidentlyKaruna KaranNo ratings yet

- Intro To Lingusitics PDFDocument51 pagesIntro To Lingusitics PDFTootsie Misa Sanchez100% (2)

- IATEFL Harrogate 2014 Conference SelectionsDocument243 pagesIATEFL Harrogate 2014 Conference SelectionsStudent of English100% (1)

- Examination of Horwitz Horwitz and CopesDocument14 pagesExamination of Horwitz Horwitz and CopesLejla MostićNo ratings yet

- Is The Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) Measuring Anxiety or Language Skills?Document29 pagesIs The Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) Measuring Anxiety or Language Skills?munaNo ratings yet

- Problems in Conversational EnglishDocument23 pagesProblems in Conversational EnglishMa. Nikka floan RamirezNo ratings yet

- The Role of Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety in English Speaking Courses (#59690) - 50092Document13 pagesThe Role of Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety in English Speaking Courses (#59690) - 50092Eden RempilloNo ratings yet

- Measuring Foreign Language Anxiety Among LearnersDocument16 pagesMeasuring Foreign Language Anxiety Among LearnersArben Anthony Quitos SaavedraNo ratings yet

- AMeasureof Chinese Language Learning Anxiety ScaleDocument29 pagesAMeasureof Chinese Language Learning Anxiety ScaleCharsley PhamNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Anxiety and Oral Exam Performance: A Replication of Phillips's MLJ StudyDocument20 pagesForeign Language Anxiety and Oral Exam Performance: A Replication of Phillips's MLJ StudyNguyễn Phước Hà ThiênNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Anxiety and English Achievement in Taiwanese Undergraduate English-Major StudentDocument14 pagesForeign Language Anxiety and English Achievement in Taiwanese Undergraduate English-Major StudentChelsea Sharon Miranda SiregarNo ratings yet

- Language LearningDocument9 pagesLanguage Learningomaramalak433No ratings yet

- Berowa LanguageanxietyDocument12 pagesBerowa Languageanxietymaryann.lopezNo ratings yet

- 61-Article Text-119-1-10-20180503Document6 pages61-Article Text-119-1-10-20180503Vanessa FloresNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Students PerspectiveDocument15 pagesAn Investigation of Students PerspectivePaung PwarNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Educational Level On Learner Anxiety: An Investigation of Iranian LearnersDocument7 pagesThe Effects of Educational Level On Learner Anxiety: An Investigation of Iranian LearnersIJ-ELTSNo ratings yet

- (15507076 - Heritage Language Journal) Chinese Language Learning Anxiety - A Study of Heritage LearnersDocument26 pages(15507076 - Heritage Language Journal) Chinese Language Learning Anxiety - A Study of Heritage LearnersBienne JaldoNo ratings yet

- Exploring English Language AnxietyDocument19 pagesExploring English Language AnxietyPrimo AngeloNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Students PerspectiveDocument15 pagesAn Investigation of Students PerspectiveRoffi ZackyNo ratings yet

- Horwitz 1988 L2 Beliefsabout Lang LearningDocument13 pagesHorwitz 1988 L2 Beliefsabout Lang LearningpmacgregNo ratings yet

- 1997 Motivation and Language LearningDocument17 pages1997 Motivation and Language LearningIsmail BoudineNo ratings yet

- Measuring Language Anxiety in An EFL ContextDocument14 pagesMeasuring Language Anxiety in An EFL ContextChoudhary Zahid Javid100% (1)

- Anxiety in Oral E ClassroomsDocument19 pagesAnxiety in Oral E ClassroomsSuaad GatusNo ratings yet

- AnxietyDocument8 pagesAnxietyRidwan NadirNo ratings yet

- Liu - Anxiety 4Document19 pagesLiu - Anxiety 4Danang SaputraNo ratings yet

- Literature Review - Learning ToolDocument10 pagesLiterature Review - Learning Tooldulce crissNo ratings yet

- Influence of Anxiety On English Listening Comprehension Zhai 2015Document8 pagesInfluence of Anxiety On English Listening Comprehension Zhai 2015Lê Hoài DiễmNo ratings yet

- Iranian Pre-University Student's Retention of CollocationsDocument12 pagesIranian Pre-University Student's Retention of CollocationsUMUT MUHARREM SALİHOĞLUNo ratings yet

- Language Learning and TeachingDocument29 pagesLanguage Learning and TeachingShahzeb JamaliNo ratings yet

- Tran - 2012 - Review of Horwitz - Theory of Foreign Language AnxietyDocument7 pagesTran - 2012 - Review of Horwitz - Theory of Foreign Language AnxietyRo Mi NaNo ratings yet

- Anxiety in EFL Classrooms: Causes and Consequences: Meihua LiuDocument20 pagesAnxiety in EFL Classrooms: Causes and Consequences: Meihua LiuEmpressMay ThetNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Author (S: Related PapersDocument10 pagesForeign Language Classroom Anxiety Author (S: Related Papersjohn huntNo ratings yet

- Investigating Foreign Language Learning Anxiety Among Students Learning English in A Public Sector University, PakistanDocument11 pagesInvestigating Foreign Language Learning Anxiety Among Students Learning English in A Public Sector University, PakistanSiti FauziahNo ratings yet

- Ej 1085922Document11 pagesEj 1085922Researchcenter CLTNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Learning Anxiety: The Case of Iranian Kurdish-Persian BilingualsDocument9 pagesForeign Language Learning Anxiety: The Case of Iranian Kurdish-Persian BilingualsPatricia María Guillén CuamatziNo ratings yet

- Results ExamplesDocument15 pagesResults ExamplesLUISA FERNANDA HERAZO DUVANo ratings yet

- International Journal of InstructionDocument16 pagesInternational Journal of InstructionWinda HardiyantiNo ratings yet

- Mary JoyceDocument10 pagesMary JoyceMary Joyce BahintingNo ratings yet

- P.75!90!10080 The Factors Cause Language Anxiety For ESLDocument16 pagesP.75!90!10080 The Factors Cause Language Anxiety For ESLJessy Urra0% (2)

- AReviewof Foreign Language AnxietyDocument25 pagesAReviewof Foreign Language AnxietyLUISA FERNANDA HERAZO DUVANo ratings yet

- ZHENG How Does Anxiety Influence LanguageDocument19 pagesZHENG How Does Anxiety Influence LanguageFlor de María Sh. LNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Anxiety: Past and Future: Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics December 2013Document25 pagesForeign Language Anxiety: Past and Future: Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics December 2013Juliance PrimurizzkiNo ratings yet

- Students' Perceptions of Language Anxiety in Speaking ClassesDocument19 pagesStudents' Perceptions of Language Anxiety in Speaking ClassesAlejo RamirezNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Anxiety and Students' Learning Motivation For Filipino Foreign Language (Korean) LearnersDocument13 pagesForeign Language Anxiety and Students' Learning Motivation For Filipino Foreign Language (Korean) LearnersIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)No ratings yet

- Second Language Anxiety and Distance Language Learning: Foreign Language Annals March 2009Document18 pagesSecond Language Anxiety and Distance Language Learning: Foreign Language Annals March 2009Hilal SoyerNo ratings yet

- Journal of Educational Psychology 2005, Vol. 97, No. 2, 246Document11 pagesJournal of Educational Psychology 2005, Vol. 97, No. 2, 246distanceprepNo ratings yet

- Pichette 2009 FLANDocument18 pagesPichette 2009 FLAN019WAFIYAH ASYIFAH FA'ADHILAHNo ratings yet

- Language Learning Anxiety Malay Undergra PDFDocument11 pagesLanguage Learning Anxiety Malay Undergra PDFMarisa Puspita DewiNo ratings yet

- Anxiety in Learning English As A Second Language at A Tertiary Stage Causes and SolutionsDocument20 pagesAnxiety in Learning English As A Second Language at A Tertiary Stage Causes and SolutionsAuliaurrahmah100% (1)

- Reflections On Speaking Anxiety in An EFL Classroom PDFDocument25 pagesReflections On Speaking Anxiety in An EFL Classroom PDFRaesa SaveliaNo ratings yet

- Bài 2 - An Exploration of Foreign Language Anxiety and English Learning MotivationDocument9 pagesBài 2 - An Exploration of Foreign Language Anxiety and English Learning MotivationTrúc ĐanNo ratings yet

- Language Research 2k17Document17 pagesLanguage Research 2k17John Lexter VillegasNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Anxiety and For PDFDocument7 pagesThe Relationship Between Anxiety and For PDFNoven VillaberNo ratings yet

- Quero Soria Barrozo DulatreDocument48 pagesQuero Soria Barrozo DulatreLolita QueroNo ratings yet

- IJSCL27001377977400 GGGDocument38 pagesIJSCL27001377977400 GGGRifka ZahiraNo ratings yet

- Tran ELT2012Document8 pagesTran ELT2012Carlo Dennis LozaritaNo ratings yet

- Cor Yell 2009Document22 pagesCor Yell 2009munaNo ratings yet

- Sy Tamco, Albyra Bianca R. (2021) - An Assessment of English Language Anxiety Among SHS Students and Its Effect On Their Academic AchievementDocument8 pagesSy Tamco, Albyra Bianca R. (2021) - An Assessment of English Language Anxiety Among SHS Students and Its Effect On Their Academic AchievementAlbyra Bianca Sy TamcoNo ratings yet

- 4 - The Audiolingual MethodDocument20 pages4 - The Audiolingual Methodtbritom100% (4)

- Language Teaching in the Linguistic Landscape: Mobilizing Pedagogy in Public SpaceFrom EverandLanguage Teaching in the Linguistic Landscape: Mobilizing Pedagogy in Public SpaceDavid MalinowskiNo ratings yet

- OAP - Basic CompetenciesDocument8 pagesOAP - Basic CompetenciesFe Marie JisonNo ratings yet

- Listado VerbosDocument8 pagesListado Verbosjonatan aguirre molinaNo ratings yet

- The Psychiatric InterviewDocument34 pagesThe Psychiatric InterviewPinkRose BrownSpiceNo ratings yet

- Forming and Using The Past Perfect TenseDocument4 pagesForming and Using The Past Perfect TenseIna ZainalNo ratings yet

- Touching Spirit Bear Extension Project Rita FavataDocument32 pagesTouching Spirit Bear Extension Project Rita FavataJCM176No ratings yet

- Expressions of Agreement: Important NotesDocument25 pagesExpressions of Agreement: Important NotesDwi indah ning tyasNo ratings yet

- Unit 7.1Document17 pagesUnit 7.1lephammydungNo ratings yet

- PP - Hong Qu Data Visualization Workshop HKS Fall 2021Document27 pagesPP - Hong Qu Data Visualization Workshop HKS Fall 2021Luis CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Testing Reading - Group 4Document13 pagesTesting Reading - Group 4Tran HauNo ratings yet

- The North Node in Your Chart: Twelve Doors To Spiritual GrowthDocument13 pagesThe North Node in Your Chart: Twelve Doors To Spiritual GrowthDequan Gambrell100% (2)

- P - 7 English Lesson Notes PDFDocument48 pagesP - 7 English Lesson Notes PDFsimbi yusuf50% (2)

- The Personal Essay Critiquing and WritingDocument12 pagesThe Personal Essay Critiquing and WritingErica Atienza - DalisayNo ratings yet

- PSLE 2021 (Oral) (Stimulus-Based Conversation) (Day 1-2)Document5 pagesPSLE 2021 (Oral) (Stimulus-Based Conversation) (Day 1-2)Aqil SubendiNo ratings yet

- MBA II BRM Trimester End ExamDocument3 pagesMBA II BRM Trimester End Examnabin bk50% (2)

- Unit 2 Lesson 3Document3 pagesUnit 2 Lesson 3api-240273723No ratings yet

- Brain Health Coaching Is An Exciting New Discipline. Look Inside and See How It Can Benefit You and Your Clients/patients.Document4 pagesBrain Health Coaching Is An Exciting New Discipline. Look Inside and See How It Can Benefit You and Your Clients/patients.Clint RumboltNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Learning LanguagesDocument13 pagesBenefits of Learning Languagesnefglobal91No ratings yet

- Small Group Action PlanDocument1 pageSmall Group Action Planapi-427436497No ratings yet

- EgoismDocument4 pagesEgoismKristel Tayam100% (1)

- DR Happy Life DMIT InformationDocument58 pagesDR Happy Life DMIT InformationscribdjaganNo ratings yet

- Evaluations That Help Teachers Learn - DanielsonDocument6 pagesEvaluations That Help Teachers Learn - DanielsonAdvanceIllinoisNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument2 pagesBackground of The Studyasif taj100% (1)

- Data Mining MCQDocument4 pagesData Mining MCQPRINCE soniNo ratings yet