Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 13.239.75.78 On Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 13.239.75.78 On Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

Uploaded by

Evan ChanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 13.239.75.78 On Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 13.239.75.78 On Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

Uploaded by

Evan ChanCopyright:

Available Formats

In Whose Interest?

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Environmental

Regulation

Author(s): Thomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

Source: Journal of Public Policy , Jan. - Apr., 2004, Vol. 24, No. 1, Markets and

Regulatory Competition in Europe (Jan. - Apr., 2004), pp. 99-126

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4007804

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Journal of Public Policy

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

?fnl Pubi. Pol., 24, I, 99-126 ? 2004 Cambridge University Press

DOI: 10.1017/S0143814X04000054 Printed in the United Kingdom

In Whose Interest?

Pressure Group Politics, Econommic Competition

and Environmental Regulation

THOMAS BERNAUER and LADINA CADUFF' Political Science,

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich

ABSTRACT

One school of thought in the literature on regulatory competition in

environmental and consumer policy argues that inter-jurisdictional com-

petition promotes regulatory laxity. The other highlights rent-seeking as a

major driving force, implying that regulatory laxity is rare because rent-

seeking is omnipresent. We observe that in most areas of environmental and

consumer policy in advanced industrialized countries regulation has become

much stricter since the I970s. What then has been driving environmental

and consumer risk regulation up? A popular explanation holds that large

green jurisdictions have been forcing their trading partners to trade or

ratchet up their regulation. In addition, political economists have developed

bottom up explanations focusing on interest group politics and corporate

behaviour. This article adds to the latter line by endogenising public

perceptions and by exploring the effects of corporate environmental

performance strategies on environmental and consumer risk policy. The

empirical relevance of propositions is illustrated with case studies on growth

hormones, electronic waste, and food safety.

Competition in laxit or rent-producing regulation?

The political economy literature on regulatory competition and its effects in

environmental and consumer policy is dominated by two opposing schools of

thought. One emphasizes competition in laxity, the other highlights rent-

seeking as a driver of regulation. Normatively, the first school tends to view

competition in laxity as a problem, whereas the second school highlights

problems of excessive regulation and associated economic inefficiency. In

this section we discuss the principal arguments of these two schools of

thought and assess their empirical relevance with regard to environmental

and consumer risk policy.

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IOO 77Tomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

Basic arguments

Many authors have argued that particularly in integrated (open) markets

states get drawn into a competition in regulatory laxity. Regulation, so the

argument, imposes costs on firms - in fact, states seem to be engaging more

and more in regulation instead of redistribution because the former allocates

the costs to those regulated whereas redistribution imposes costs on govern-

ments and taxpayers (see for example Majone I996; Kelemen 2000). Firms,

if burdened with costly regulation, are likely to vote with their feet, i.e., by

relocating to jurisdictions with laxer regulation, tax evasion, non-compliance

with regulation, and other types of behaviour. Policy-makers, for their part,

incur some of the costs of such corporate behaviour, e.g., voter dissatisfaction

due to higher unemployment when domestic firms relocate and foreign

direct investment dries up, or due to cuts in government programs when

corporate tax income declines. Because they are anxious to retain firms and

capital and attract new investments policy-makers tend to be responsive to

business demands for regulatory laxity (e.g., Daley I993; Donahue i994).

Strategic government behaviour at the international (or, inter-

jurisdictional) level is, in this line of theorizing, viewed in prisoner's dilemma

terms. In the extreme case, this argument predicts a race-to-the-bottom in

terms of ever laxer regulatory standards. In the not so extreme case, it

predicts 'regulatory chill', i.e., inability and/or unwillingness of governments

to raise existing standards.

The second school of thought was initiated by regulatory capture theory,

which challenged market failure justifications for and associated functionalist

explanations of government intervention (Bernstein I955; Stigler I97I;

Richards I999). Public choice theory has developed the capture argument

further. It treats regulation as a commodity (implying transfers of wealth)

that is sold by regulators to the politically most influential societal groups

(Stigler I971; Posner I974; Peltzman 1976; Becker I983). Public choice theory

does not argue that business will always capture regulators (Teske I99I).

However, drawing on Olson's Logic of Collective Action (I965) it holds that

industry is more likely than consumers or the wider public to be effective in

capturing regulators. Industry groups are comparatively smaller in number

and better endowed with resources. Hence they are more effective in

overcoming free rider and other organizational problems - these problems

are presumably a function of group size, resources, and per capita

stakes. Large and heterogeneous public (or civic) interest groups are at a

disadvantage in this respect (Chang I997).

Empirical relevance

In virtually all advanced industrialized countries environmental and con-

sumer risk standards have been raised substantially since the 1970s.

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation I01

Implementation of existing standards is by no means perfect, and many

environmental and consumer risk problems are far from being resolved. But

increased standards have contributed to improved environmental quality or

have at least slowed down environmental degradation. Examples include

water and air quality, waste management, energy efficiency, pesticide and

fertilizer use, carcinogenic substances in food, and deforestation. The avail-

able evidence also disconfirms claims that advanced industrialized countries

have become 'cleaner' by shifting polluting industrial activity and waste to

poorer countries with laxer environmental regulation (e.g., Wheeler 2000;

Levinson I996; WTO I999). As noted by Vogel and Kagan (2002) and many

other authors (e.g., Berger and Dore I996; Wheeler 2000), economic open-

ness has resulted neither in policy convergence nor in a race to the bottom.

Moreover, statistical analyses show that trade openness tends to have only

a very limited (and often negative) effect on emissions (e.g., Bernauer and

Koubi 2003; Sigman 2002; WTO I999). In some cases inter-jurisdictional

competition seems to have exerted a regulatory chill effect (e.g., in climate

change policy). But regulatory chill effects appear to be the exception and

not the rule, and there are extremely few examples of regulatory competition

leading to a lowering of environmental standards, for example in terms of

more inflow of foreign direct investment into 'pollution havens' (see for

example, WTO iggg; Jaffe et al. 1995; Revesz I992).

These observations challenge the first school of thought as applied to

environmental and consumer risk regulation. But they also challenge the

second school of thought, albeit in less obvious ways.

On the one hand, one may argue that deregulation and liberalization

reduce rent seeking across the board: more economic competition leads to

more heterogeneous, competing and thus politically less influential demands

for rent-producing regulations, and more liberal governments are less likely

to meet such demands. Assuming that rent seeking is a key driver of

environmental and consumer standards we should observe a stagnation or

lowering of such standards.

On the other hand, one may argue that when subsidies, price fixing,

import quotas, tariffs, and other government measures for limiting compe-

tition are dismantled firms will increasingly try to substitute these traditional

measures for more complex regulation that is easier to defend. Environ-

mental and consumer risk regulation may, in this context, serve to transfer

wealth from consumers to industry, for example by mandating higher quality

and thus more expensive products (e.g., low emission vehicles, refrigerators

without CFCs). However, the public is likely to view such measures as more

legitimate than traditional measures for limiting competition. This argument

holds that increased economic competition has not eliminated rent seeking.

But it has driven firms into new forms of rent seeking, notably rent seeking

through stricter environmental and consumer risk regulation.

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I02 7homas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

The evidence on increased environmental and consumer risk standards

and on improved environmental and public health outcomes obviously casts

doubts on the first type of rent seeking argument. In this article's section

on industrial competition we will also challenge the second rents-focused

argument by claiming that straightforward rent seeking in environmental and

consumer policy is very rare and usually unsuccessful. Viewing the stringency

of environmental and consumer standards as a function of opportunities for

rent seeking is too simplistic and probably wrong. In other words, we agree

with both arguments that increased economic competition has reduced

opportunities for crass rent seeking. But we disagree with the first argument

that this has had a negative effect on environmental and consumer risk

regulation. And we disagree with the second argument that this has promoted

rent providing environmental and consumer risk regulation - instead we

argue that corporate environmental performance strategies, which rarely

provide rents, defined as socially costly pursuit of income and wealth transfer

(Drazen 2000: 335),2 but enhance firms' competitive position, are increasingly

important driving forces in environmental and consumer policy.

M4/hy is there vegy little competition in laxity?

Political economists and political scientists have offered a plethora of

explanations for why competition in laxity remains rare in environmental

and consumer policy.

Some political economists have pointed to the limited effect of environ-

mental and consumer risk regulation on firms' production costs (usually

around I-5 per cent) -to the extent that this effect is weak firms are

obviously less likely to fight for laxer standards (e.g., WTO I999; Wheeler

2000). Others have pointed to the so-called Kuznets effect, i.e., that

economic growth, stimulated by deregulation and liberalization, has a

positive impact in many areas of environmental and public health protection

as richer consumers and voters, particularly those in democratic countries,

successfully demand higher standards (e.g., Bernauer and Koubi 2003).

While these analyses are useful in terms of producing highly generalizable

insights, explained variance in environmental and public health outcomes

remains rather low. Moreover, policy processes that lead to particular

outcomes are not illuminated.

In explaining variation in the form and stringency of environmental and

consumer risk regulation political scientists have stressed the role of political

entrepreneurs (Wilson I980; Moe I980; Meier I989; Majone I996), the

influence of ideas (Derthick and Quirk I985; Vogel I996), and characteristics

of institutions and/or policy issues (Gormley I983, I986). They have,

notably, been interested in explaining when and how majoritarian politics

wins over concentrated business interests (Teske I99I).

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation I03

Yet other political scientists have focused on interactions between juris-

dictions, with work by Dale Murphy, Fritz Scharpf and David Vogel

providing the starting point for a growing body of literature on 'trading up'

processes and regulatory federalism in environmental and consumer policy.3

Early versions of this theory (see Vogel I996; Murphy I995) claimed that in

open markets large and green jurisdictions transmit their environmental

preferences to their trading partners. Particularly in the case of product

regulation they can force exporters to lift their standards up to the level

demanded by importing jurisdictions (e.g., Swire I996; Scharpf I996, see also

figure i, conclusion). Examples include automobile emission, food safety

standards, and CFC-free appliances.

More recent versions of this argument (e.g., Vogel and Kagan 2002;

Bernauer 2003) assume that in highly integrated markets, such as those of the

EU or the United States, where goods are by law allowed to flow freely

across the boundaries of the subunits (e.g., EU member states, US states),

differences in product and process regulation can be problematic (see also

Holzinger and Knill, this issue).

Interest group politics

All of the above explanations involve assumptions about 'bottom up' forces

in regulatory policy. For example, theories of competition in regulatory

laxity and public choice theory assume that industry interests tend to

dominate over consumer (or public) interests. In the former theories,

industry is assumed to favour laxer regulation because laxer regulation

increases firms' international competitiveness. In the latter theory, industry

is assumed to favour stricter regulation because such regulation offers rents.

Trading-up arguments, for their part, assume 'green' public preferences

in large importing jurisdictions and their transmission to firms (and

governments) abroad via international trade and multinational corporations.

We propose to refine these rather simplistic assumptions about consumer

and producer preferences and their effects on regulation and environmental

or public health outcomes along two lines. First, we develop an interest

group politics argument that endogenises public perceptions, regulators'

preferences and other factors largely ignored in theories of this nature. The

empirical relevance of this argument is illustrated with a case study on

growth hormones. Second, in the subsequent section we disentangle the

aforesaid contradictions between public choice and regulatory laxity argu-

ments with regard to producer preferences by exploring why and how firms

may seek stricter regulation to enhance their competitiveness. We also assess

the effects on regulatory policy. The empirical relevance of this argument is

illustrated with case studies on electronic waste and HACCP (a system for

controlling food safety).

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

104 TIhomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

In this section we illuminate interactions between interest groups, voters,

and politicians. We begin with a discussion of conditions under which NGOs

can organize effectively, with a focus on the effect of public perception on

NGO behaviour. We then explore interest group strategies for influencing

politicians and voters, in particular informational activities aimed at the

larger public and policy-makers.

Public concerns over environmental or consumer issues

The starting point for an answer to why the producer dominance hypothesis

appears to be inconsistent with the empirical evidence in many cases of

environmental and consumer regulation can be found in Mancur Olson's

'Logic of Collective Action'.4

Olson observed that some groups are more likely to organize collectively

because they are more adept at overcoming free-rider problems than others.

Specifically, he hypothesized that large (latent) groups are difficult to

mobilize. The underlying logic is as follows. Consumer and environmental

organizations are pressure groups that offer a 'collective good', that is,

consumer or environmental protection. The production of collective goods

is usually plagued by a free-rider problem.

We pick up at this point and assume that NGOs are aware of their

collective action problem, and that they follow a rational strategy (such as to

try and maximize their budget or other utility). NGOs will, therefore, tend

to focus on issues that allow for maximum mobilization of membership,

fundraising, and public support more generally. Public concerns or risk

perceptions are likely to be decisive in determining the 'winability' of an

issue from an NGO perspective (Meins 2003; Gormley I986).

The extent to which public concerns become politically relevant is largely

a matter of public risk perceptions5 and the problem solving capacity of

regulators, particularly as expressed by the effectiveness of previous risk

management policies (Caduff 2003). If the public in a given country is more

critical or fearful of a particular technology (or risk more generally), in ways

and for reasons to be identified, NGOs are likely to be more successful in

mobilizing their memberships if they decide to campaign for more regu-

latory restrictions. Furthermore, if particular risk regimes are characterized

by weak institutional rules for addressing public distrust, low transparency in

decision making, delayed action in the face of critical events, and severe

implementation failures, public trust in regulatory institutions and the

creators of risk, that is, industry, will erode, whereas NGOs' credibility with

the public will increase (see also Jacobsen 2002). In other words, we expect

that NGOs will organize around a particular policy issue and campaign for

regulatory restrictions more extensively and successfully if public concerns or

fears about a given technology or consumer or environmental risk are strong

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation I05

and public trust in the risk management capacity of regulatory institutions is

low.

Whether public concerns are a cause or a consequence of NGO activities,

or whether the relationship is interactive, remains unresolved in theorizing

and empirical research on environmental and consumer policy (Bernauer

2003, Berry 2ooo, Rawcliffe I998). Many analysts of environmental and

consumer policy assume that NGOs have often been the principal instigators

of public concerns over consumer or environmental risks. The above

argument suggests, however, that the cause-effect relationship may also

work the other way around, namely, that NGOs are predominantly

opportunistic actors piggy-backing on pre-existing public risk perceptions.

The propositions outlined below allow for both types of effects.

NGOs as public opinion leaders

Access to and ability to provide policy-relevant information are important

sources of interest group influence in regulatory processes. Policy-makers

tend to value such information in calculating the costs and benefits of

regulatory options and in deciding whether to change the status quo, and if

so, whether to move toward stricter or laxer regulation. Moreover, because

the average voter has little incentive to incur the cost of studying regulatory

issues in detail, the public tends to be receptive to information provided by

interest groups (Grossman and Helpman 200I: 7).

Though it can be very costly for interest groups to acquire and

communicate information on regulatory issues they have strong incentives to

do so, that is, to supply information to policy-makers and the public when

they perceive promising opportunities for shaping public opinion and

influencing policy decisions. However, interest groups find themselves in an

'informational competition' with one another. Each interest group is trying

to convince policy-makers that its favoured policy is beneficial or at least not

politically damaging to them. In addition, each interest group is trying to

convince voters who tend to update their preferences only when they trust a

given interest group's information and when that information is relevant to

voter concerns (see also Grossman and Helpman 2001: I87).

We now connect these assumptions to the above proposition on the

impact of public perceptions on NGO strategies. Specifically, we submit that

NGOs tend to become more important as an informational source of the

general public relative to industry interest groups when public concerns over

a consumer or environmental risk are strong. The stronger public concerns

are, the more effective NGOs are likely to be in shaping public opinion. And

it is primarily through their influence on public opinion that NGOs are able

to influence policy-decisions.

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

io6 Thomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

Information provided by NGOs tends to be particularly relevant to the

average voter (consumer) when it pertains to risk regulation with direct,

tangible and short-term benefits. Risks of this nature and benefits of

regulation mitigating such risks are largely individualized (Caduff 2003). In

some empirical cases it even turns out that the benefits of such risk regulation

are not public but private in character - such benefits involve private

health-related consumption goods (Reinhardt 2000). Typically, voters and

consumers tend to be more aware of such risks than of risks of a more diffuse

nature whose mitigation produces diffuse benefits for society as a whole.

While regulation on food safety tends to focus on risks and benefits of the

former nature, many environmental statutes centre on risks that materialize

mostly over the long-term and whose mitigation produces more diffuse and

indirect benefits.

Organizing around an issue of strong concern to the average voter or

consumer enables NGOs to obtain or enhance a reputation as defenders of

important public interests. It increases their credibility with the public and

therefore also their capacity to attract public trust. Public trust, in turn, is one

of the most powerful assets of NGOs in the political and market place (Aerni

2002, 2003; Rawcliffe I998). Under such conditions, the mass media can

amplify NGO influence, for it tends to have stronger incentives to provide

publicly trusted environmental and consumer organizations with a broader

platform for publicizing their statements. In some cases, the media may also

join hands with NGOs and actively support NGO demands. Increased

media coverage tends to increase public awareness and public concerns,

which increases NGOs ability to raise funds, mobilize members and

eventually attract new supporters of their cause. By using the mass media as

a low-cost vehicle for informational activities NGOs can often act as

opinion-leaders, with evident implications for voters' preferences with regard

to environmental and consumer policy issues. Interest groups opposing

stricter regulation tend to be disadvantaged in this struggle for public

support. They usually receive smaller media coverage and enjoy less public

trust than NGOs because they are perceived by the average voter as seeking

private and not public benefits. Hence they are more likely to lose on the

'information front'.

Because of their increased capacity to organize, and because they tend to

enjoy more public trust than industry interest groups, NGOs can also take

more effective action against producers. They can, for example, organize

boycotts of specific products, firms, or even entire industries, or launch

public campaigns aimed at tarnishing the image of firms, industries, or

products.6 The stronger public concerns over a particular issue are, and the

more information on this issue NGOs are able to provide, the larger the

boycott will be and the earlier it will occur (see also Baron 2002). Through

such action environmental and consumer groups can bring about changes in

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation I07

producers' preferences and behaviour in the market place, with evident

implications for regulatory processes.7

To summarize, focusing on an issue of high relevance to the average voter

enables NGOs to acquire more public trust than industry interest groups,

and to act as the public's principal source of information. As a consequence,

voter preferences with respect to the issue of concern tend to shift towards

the policy proposed by NGOs, usually toward preferences for stricter

regulation. Policy-makers know that the average voter is being informed

(and influenced) by environmental and consumer groups (Grossman and

Helpman 200I: 29). Concerned with their re-election policy-makers thus feel

obliged to opt for stricter environmental or consumer protection, no matter

whether stricter regulation increases aggregate welfare or not, and no matter

whether stricter regulation is fully consistent with policy-makers' preferences.

If NGOs can team up with producer groups, not moving towards greater

regulatory stringency would be even more politically damaging to policy-

makers. In the next section we will focus on when and why producer groups

join hands with NGOs.

Interests and influence ofproducer groups

The conventional political economy model of regulation holds that stricter

environmental or consumer protection standards are more likely to be

enacted if producers can benefit economically (in terms of rents) from the

particular regulation. In principle, stricter regulation can yield at least two

types of benefits to producers, the expectation of which motivates firms to

seek stricter regulation.

Protectionist benefits. Environmental and consumer protection will tend

towards greater stringency particularly in areas where regulation can be

designed to shield import-competing domestic firms from foreign competi-

tion. The assumption here is that producer demand for import-restricting

regulation is likely to attract more political support if justified in terms of

protecting public health and the environment, rather than in terms of

protecting domestic firms. The latter is more difficult to justify and defend

because it transfers wealth from domestic consumers to domestic producers.8

Domestic economic benefits. Similar to the argument on protectionist rents,

this argument assumes that firms' interests are shaped by industrial structure

and that firms seek to improve their competitive position through regulation.

But in contrast to the regulatory capture and rent-seeking argument in

conventional economic theories of regulation9 this second argument does not

assume that there is a single industry with homogeneous interests within a

given country. Individual firms or groups of firms within a specific industry

may lobby for stricter or laxer regulation, and for harmonized or particu-

laristic regulation, depending on differences in industrial structure and

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

io8 Thomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

competitive position. For example, some large firms may lobby for stricter

environmental or consumer regulation that would be too costly for smaller

firms to implement, whereas smaller firms within the same industry and the

same country oppose such regulation.'0

We now connect these arguments to the above proposition on the political

power of NGOs. An issue of high concern to the average voter and

associated campaigns by environmental and consumer groups can exert

'pull' and 'push' effects on producers (industry). Public concerns and NGO

campaigns can act as facilitators for rent-seeking by producers. 'Strange

bedfellow' coalitions of environmental/consumer and producer interests that

lobby for the same stricter regulation, but for different reasons, are

expressions of this possibility. Such pull effects can weaken producer

coalitions that oppose stricter regulation to the extent that incentives to

'piggy-back' on public concerns and NGO campaigns differ across firms or

types of producers in a given industry. Public concerns and NGO campaigns

can also exert 'push' effects by coercing producers that do not expect to

benefit from stricter regulation into supporting or tolerating such regulation.

Again, differences in industrial structure and competitive position of firms

are likely to determine the extent to which particular producers in a given

industry are more or less susceptible to push effects. For example, some

producers may be more vulnerable to public pressure and NGO campaigns

than others because they have valuable brands to protect, or simply because

they are bigger, which makes them a more attractive target for NGOs. In

addition, organizational and economic rigidities in particular economic

sectors may also shape the extent to which push effects translate into changes

in industry behaviour. For example, low economic concentration and poor

political organization may (paradoxically, at first glance) make certain

industrial sectors less vulnerable to NGO campaigns.

In summary, the argument outlined here holds that public concerns and

NGO campaigns generate pull and push effects on producers. Contingent on

differences in industrial structure, the extent to which these effects weaken

producers' political power will vary across issues and countries.

Empirical illustration: growth hormones in beefproduction

Hormones can be administered to animals to promote faster growth and

muscle build-up. " On average, a hormone-treated animal will grow faster by

I5 percent. The associated decrease of production costs for the farmer is io

to I5 percent. The economic benefits of growth hormone administration are

most substantial in large-scale meat production, where the amount of feed

and the attainment of the proper slaughter weight within a fixed time-period

are crucial in determining profits.

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation I09

In I985 the EU banned the use of hormones for purposes of growth

promotion in beef production. The relevant regulations have been justified

as reducing health risks posed by the banned practices. The EU's regulatory

activity in this area started in I980, when hormone use in livestock breeding

developed into a controversial public health issue that culminated in the veal

hormone scandal of I980, the so-called 'Italian infant scandal'. This case,

and others which became public in Europe around that time, were traced

back to the injection of prohibited anabolics into the edible tissues of calves

(European Parliament 1995/W12:7). This practice had contaminated entire

foodstuffs, for example, baby food produced in Italy, which contained traces

of diathylstilboestrol (DES), an illegal synthetic hormone (Die Zeit I988/44).

The press soon thereafter reported that DES-enriched veal in baby food had

led to abnormally large genitals and the onset of menstruation among young

children.

European consumer organizations immediately organized around the

issue and began campaigning for a ban on growth hormones. Taking

advantage of pre-existing public concerns about food safety they followed a

strategy of amplifying public concerns over hormone treated beef. In so

doing, NGOs engaged in a broad range of informational activities: they

released several scientific reports on the health risks of hormone use,

published a substantial amount of articles in the daily press, and invested in

TV campaigns aimed at informing the public of the risks of hormone treated

meat. The media largely supported NGOs in their lobbying against growth

hormone use, arguing that the long-term health effects of these hormones

were not known, and that the hormone scandals had clearly shown that

existing regulations could not sufficiently protect consumers. NGOs also

received support from the European Parliament (EP), which, as many

observers have noted, took advantage of the controversial and highly

publicised debate on consumer protection to establish a stronger position

within the EU system (see for example Eichener I996). By confronting

the obvious abuse of growth hormones, consumer organizations, supported

by the media and the European Parliament, positioned themselves as

trustworthy promoters of 'the public interest'.

Consumer organizations also engaged in more costly forms of lobbying

activity, including the initiation of boycotts against hormone treated meat.

When NGOs realized that many consumers began boycotting veal products

on their own (Die Zeit ig8o/No.44), they started to take direct action against

producers. In France and Germany, the French Consumers Union organ-

ized a veal boycott, which, with the help of the European Consumer

Organization (BEUC), spread to the whole of Europe. As a consequence,

food product chains like Alete and Hipp pulled their veal products off the

market (Der Spiegel I985/46: I53). Veal prices dropped by I3 per cent in

France, and fell in Belgium, West Germany, Ireland and the Netherlands

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I1I0 Thomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

(Cohen I980: 2). Sales of meat dropped by 50 per cent in France and West

Germany during the boycott (Der Spiegel I982/3:76). Since the agricultural

policy of the EU at that time provided for guaranteed fixed purchases, the

unsold veal of that year resulted in a loss of io million ECU to the EU's

budget (Europe Daily Bulletin I985/4042:8).

European producers of growth hormones, organized in the Federation of

Animal Health (FEDESA),12 tried to convince the public and policy-makers

not to prohibit growth hormones, but to begin more systematic scientific

investigation of their public health effects (Economist I984, Feb 25). FEDESA

even tried, unsuccessfully, to shape public opinion by warning regulators and

the public that banning growth hormones could lead to more illegal and

dangerous growth hormone use: 'Remember the US alcohol prohibition

laws? Contraband was rife and the black market flourished!' (FEDESA

campaign, quoted in Brand and Ellerton I989: 4,5).

Producers were clearly disadvantaged in competing for influence on

public opinion, mainly for two reasons. First, highly publicised hormone

scandals and associated NGOs campaigns had led to an erosion of public

trust in producers and regulatory institutions, whereas NGOs' credibility

with the public increased. FEDESA's large investments in public relations

campaigns failed in turning this trend around (Brand and Ellerton I989).

Moreover, government authorities failed to fully inform the public on the

issue, which added substantially to escalating public fears of growth

hormones (European ParliamentWI2/I995:8). Second, FEDESA's position

on the issue was weakened by the fact that some producer groups joined

hands with NGOs. Through boycotts and lobbying activity, consumer

groups exerted 'pull' and 'push' effects on producers. On the one hand,

public concerns and NGO campaigns facilitated rent-seeking by some

producer groups, notably, import-competing, family-owned farmers in Italy,

France, and some other countries, which did not use growth hormones.

These producers tried to capture protectionist rents vis-'a-vis foreign com-

petitors as well as domestic economic benefits vis-'a-vis more efficient,

large-scale EU meat producers. On the other hand, market developments

made clear that consumers demanded 'natural' products. This had evident

implications for farmers using growth hormones, wholesalers, and retailers.

Fearing further losses, these producers decided to provide higher beef

quality, that is, hormone free beef. To avoid competitive disadvantages

(hormone use lowers production costs), however, they demanded strict

implementation of the ban in all EU member states, as well as an

internationalization of EU policy, i.e., an import ban on hormone-treated

meat from third countries. These demands were met in I989.

When, in I989, the EU's hormone ban was extended to imports from

third countries, US meat producers began to experience annual losses in

the order of $I30 million per year. Though this loss has amounted to only

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation III

o.I per cent of the EU-US annual trade volume, the EU's hormone ban has

led to one of the longest and most acrimonious transatlantic trade disputes.

By I999, the dispute had moved through the WTO's dispute settlement

mechanism. The final verdict supported the US claim that the European ban

on hormone' treated meat was not based on sufficient scientific evidence. The

US and Canada have since been retaliating against the EU's restrictions.

To summarize, by means of their various informational and lobbying

activities, NGOs offered an effective avenue for translating widespread

consumer concerns into political and market initiatives. Taking advantage of

pre-existing public concerns, they were largely successful in amplifying these

concerns. As market developments made clear, many consumers in Europe

perceived hormone-free beef as offering a health benefit to the individual

consumer. And policy makers and producers in Europe had to acknowledge

that fact. As noted by the EU's Council of Ministers: 'Because of campaigns

by consumer organizations, the consumption of meat had, in the past, at

various times, noticeably declined. These campaigns are not just based on

concerns as regards the health hazards of hormones, but express a general

tendency in public opinion, namely the aversion to the use of chemicals in

agriculture. A legalization of hormones would, therefore, lead to an even

more extensive wave of protest and an even greater decline in meat

consumption' (quoted in European Court ofJustice I988: 4045).

Industrial competition and regulation

Conventional political economy theories of regulation as well as the interest

group explanation developed in the previous section offer very litde analysis

of the strategic behaviour of firms and its implications for environmental and

consumer risk regulation. Most theoretical work along these lines focuses on

industry-wide behaviour and relies on simple assumptions about corporate

interests (notably, rent seeking).'3 In this section we offer a more sophisti-

cated view of corporate interests and behaviour and its effects on regulatory

policy.

In the mid-iggos Porter, van der Linde and others'4 suggested that stricter

environmental regulation, rather than providing (inefficient) rents, promotes

technological innovation and competitiveness. In the meantime, a large body

of literature has emerged that seeks to test what has come to be called the

Porter hypothesis.'5 The evidence available thus far suggests that stricter

regulation may at least in some cases be beneficial to regulated firms and the

environment. The innovation-inducing effect of regulation highlighted by

the Porter hypothesis implies that firms may benefit from stricter regulation

in ways entirely different from the conventional rent seeking assumption.

One may argue in fact that because economic liberalization is making crass

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

112 Thomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

rent seeking harder (see also above) firms are increasingly using environ-

mental performance strategies to enhance their competitive position in

domestic and international markets (Hoffman 2000).

As a starting point we submit that firms are increasingly engaging in

environmental performance strategies and are pushing for stricter govern-

ment regulation to back these strategies. We also submit that these processes

have, under conditions to be specified, positive effects on environmental and

public health outcomes. Analysis of this hypothesis requires answers to two

questions. First, what is motivating firms to pursue environmental perform-

ance (or, 'beyond compliance') strategies, and when and why are firms

pushing for stricter public regulation to back these strategies? Second, when

and why do corporate environmental performance strategies and stricter

public regulation improve corporate competitiveness and/or environmental

(or public health) outcomes. In this article we concentrate on the first

question because we are interested in the driving forces of increasing

regulatory stringency.'6

Our research to date suggests that firms engage in corporate environ-

mental performance strategies (which may involve over-compliance with

public regulation) for several reasons, including the following:

to cut production costs and thereby improve competitiveness on the supply side: strategies to that

end focus on reducing materials and energy use and waste, on more efficient

product and production process design, on developing environmentally friendly

product substitutes, and on reducing business risks and their financial implications

(e.g., reducing exposure to product liability or compensation claims, shielding

against non-insurable risks, reducing insurance costs);

to improve competitiveness on the demand side: measures to that end focus on product

development programmes intended to meet consumer demand for green and/or

healthier products, and on corporate marketing and public education programmes

designed to meet existing or create new demand for green and/or healthier

products. They also focus on promoting industry standards that require green

and/or healthier products and/or create or enhance beneficial market segmenta-

tion for particular products - e.g., through labelling standards and/or product

quality standards that define niche segments offering price premiums (e.g., sustain-

ably produced timber, organic food). They also focus on creating good will and

increasing the value of brands.

Moreover, and crucial from the viewpoint of public interests and regula-

tion, firms may push for public regulation that supports supply- and demand-side

environmental perfornance strategies. Such regulatory strategies may permit par-

ticular firms to capitalize on proprietary technologies, product qualities,

or advantages in marketing and distribution, for example, by requiring

specific products (e.g., substitutes for pollutants, as in the CFC case). Also,

they may help firms in defining market segments for products, in creating

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation II3

cost differentials (e.g., in implementation costs of public regulation), and in

shifting liability burdens and insurance costs. Note that such regulatory

strategies are hard to locate within the conventional regulatory capture

argument. In fact it appears difficult to find empirical examples where such

strategies have - from a business viewpoint - been successfully pursued at

the expense of consumers (the public) and the environment. In most cases we

know of, attempts at crass rent-seeking dressed up as environmental perform-

ance strategies have been blocked by regulators and courts at local, national

and international levels.'7 These regulatory strategies also go much beyond

the narrow focus by most authors (e.g., Reinhardt 2000) on corporate

regulatory strategies as instruments for imposing costs on competitors.i8

Firms can choose between the environmental performance strategies just

described. In making their choices they will usually try to determine which

of these strategies, or combinations thereof, are most likely to succeed, that

is, create and capture value for the firm. In that decision process firms will

consider the economics of the respective industry, the position of the firm

within this industry, its organizational capabilities, and other socio-economic

and political factors.'9

Theorizing and empirical research on when and why firms are engaging

in environmental performance strategies, and how the pursuit of such

strategies affects public regulation, is at the very beginning. It is building on

existing market and non-market theories of the firm and theories of

regulation.'0 As illustrated by the case studies on electronic waste and

HACCP (see below), firm size and sectoral characteristics (e.g. industrial

concentration, competition over prices or quality) are likely to play a key

role. Firms using strategies aimed at influencing their competitive environ-

ment must be able to induce changes in competitors' behaviour in ways that

create first mover advantages for early adopters of environmentally superior

products or processes. To capitalize on proprietary technologies, product

qualities, or advantages in marketing and distribution firms must be in a

position to compel their rivals to follow in their footsteps, whether through

market pressure or through public regulation, or both (see also Reinhardt

2000). Preliminary evidence also suggests that there are scale economies in

implementing regulation: smaller firms incur higher costs in implementing

public regulation than larger firms. To the extent that this holds true,

corporate support for stricter rules that back advantages derived from

unilateral environmental performance strategies will often be driven by the

interest of large firms.

Empirical illustrations: electronic waste and HACCP

The first of the following two case studies, which are used to illustrate the

above arguments, adopts a firm-level perspective, focusing on Electrolux.

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

114 T7homas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

The second case-study, which focuses on food safety regulation, adopts a

sectoral perspective.

Electronic waste

Electrolux is the world's largest producer of appliances and equipment for

kitchen, cleaning and outdoor use. In 2002 it announced a strategic

redefinition of its business: shifting from an 'appliance manufacturer to an

industrial cleaning service firm'.2' Its competitive advantages as an appliance

manufacturer lie primarily in its design capabilities and its efficient and clean

production capacity, and its extensive marketing and distribution system.

The firm has yet to demonstrate its advantages in industrial cleaning

services; but environmental performance and environmental regulation may

provide a basis for establishing competitive advantage.22

Electrolux has been a leader in mitigating environmental risks of elec-

tronic equipment. However, to this point in time, it has had limited success

in exploiting its efforts at superior environmental performance. As the firm

acknowledged, it has experienced considerable difficulty with its green

marketing efforts. The reason offered was that consumers lacked knowledge

of the environmental risks associated with electronics; in particular, con-

sumers were not adequately aware of the toxic components of such

equipment.23

In view of the limited success of its environmental initiatives, Electrolux

has turned to regulatory strategies to capture the benefits of its past efforts

to design, produce and market superior and environmentally friendly

products. The competitive advantage of Electrolux in pursuing this kind

of regulatory strategies lies in its first mover status, that is, in having already

developed products that can meet very stringent regulatory standards. A

new regulatory arena in which Electrolux could obtain regulatory advantage

is that of standards affecting electronic equipment waste - e-waste. E-

waste currently amounts to 4 per cent (or 7 million metric tons) of munici-

pal waste in Europe and the US, and is growing by 3-5 per cent annually.

It is now one of the fastest growing waste streams in the industrialized

world.24

In late 2002, the European Union issued draft Directives on 'Waste from

Electrical and Electronic Equipment' (WEEE) and 'Restriction on the Use of

Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronic Equipment' (RoHS). The

former requires manufacturers or importers of electronic equipment to take

back their products at the 'end of life' and to ensure sorting and recycling

without additional charge to the consumer.25 It thus makes businesses

responsible for funding the management, recycling and disposal of e-waste.

This regulation also reflects an advanced stage in the European Union's

efforts to implement the 'polluter pays' principle in the form of the so-called

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation I 15

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR).26 The RoHS directive prescribes

the phasing out of important hazardous components in electronics, such as

lead, mercury, cadmium, and brominated flame-retardants. These chemicals

will be banned in manufacture from 2007. Exceptions are granted in case no

substitutes are available.

In the United States, no similar laws exist at the federal level, and

electronics manufacturers have been rather reluctant to launch US recycling

programs. Many components in electronic equipment do not pass hazardous

waste tests, which makes them subject to the federal Resource Conservation

and Recovery Act (RCRA). But most states and federal agencies have

exempted e-waste from RCRA regulation under loosely defined waivers.27

Because much of the US e-waste, an estimated 6o-8o per cent, ends up in

developing countries or emerging markets, mainly Taiwan and China, the

US has lobbied Asian governments to include clauses in bilateral trade

agreements that allow the US to continue shipping its electronic waste

abroad.28 Nonetheless, several US states have passed e-waste recycling and

take-back legislation and other states are considering such legislation.29

Through early creation of recycling infrastructure and reduction of

hazardous materials in its products ahead of formal regulation, Electrolux

has minimized the cost and organizational implications of increasing

regulatory constraints. Electrolux, Braun, followed by HP and Sony have

taken the lead in redesigning products to enable recycling and to reduce end

of life waste, as well as developing substitutes for hazardous substances. They

have also announced that they will organize taking back and recycling old

equipment.

Because of its advantage in meeting the stricter standards that are

currently being introduced Electrolux is in a position to promote even more

stringent regulation that may provide an additional competitive edge. In

fact, Electrolux is the leading advocate of EPR. Whereas most companies in

the white and brown goods sectors prefer collective responsibility, i.e.,

sector-wide and non-profit collection schemes, Electrolux favours individual

responsibility. On the one hand, it views individual EPR as an incentive to

develop eco-designs. On the other hand, it fears that under a collective

system it would end up paying as much for the collection of e-waste as its

counterparts that have not yet invested heavily in environmentally friendly

designs.30 Henrik Sundstrom, VP of Environmental Affairs at Electrolux,

stated 'the company sees individual EPR as an opportunity to gain

competitive advantages by designing environmentally friendly products'.3'

Electrolux' position on EPR has been supported by the umbrella organiz-

ation of environmental groups in Europe, the European Environmental

Bureau (EEB), and the European consumer organization BEUC. This broad

coalition gave the European Parliament strong support for maintaining its

position on individual EPR.

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ii6 Thomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

Electrolux would clearly benefit from standards requiring EPR. Possibly

most important, it would benefit from more stringent e-waste regulation also

in the United States. In the United States, the leading electronics producers

have been opposed to EPR, be it in the US or in Europe. The American

Electronics Association (AEA), the largest trade association of electronic

companies in the US has launched a major offensive against the European

Union's WEEE and RoHS directives.32 These companies argue that the new

EU laws will pose 'a straightjacket for product innovation, and disadvantage

the consumer and the environment'.33 Rather than uniform mandatory

regulation, these US firms and organizations want industry-developed

voluntary, international guidelines to integrate environmental considerations

into product design, development and marketing. They clearly favour

voluntary responsibility for end-of-life products, which would be assigned to

a host of stakeholders, not to manufacturers and importers of electronic

equipment only.

As a first mover on EPR Electrolux has enhanced its ability to expand in

the US market as a growing number of US states move toward stricter

regulation while US competitors behave reactively rather than proactively.

Similarly, even more stringent EU regulation is likely to bolster Electrolux'

competitive position, as it could provide 'lock in' for Electrolux's techno-

logical and supply chain advantages and make it harder for smaller and

foreign companies to comply with complex new restrictions. This strategy is

costly but the benefits for Electrolux appear to outweigh the costs. Stringent

regulation will raise investment and production costs, and potentially reduce

margins, for all producers. But the biggest negative impact is likely to be on

mid-tier and small electronics vendors in Europe. Large firms will have a

competitive advantage insofar as they may have greater financial and

technology development capacity to meet stringent regulation. Strict EU

laws could also create a significant barrier to entry into European markets,

as few new manufacturers have adequate disposal and recycling strategies.

Food safety: hazard analysis and critical control point (HA CCP) systems

Many food processors and retailers in advanced industrialized countries

have in recent years established corporate food safety systems that exceed

formal government standards by a wide margin. They have done so at the

cost of billions of US dollars.34 Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point

(HACCP) systems are a key element in most of these measures. HACCP is

a process control technique based on total quality management principles.

Thus it is a business management tool and a food safety control measure at

the same time. Firms use this procedure to identify and evaluate hazards that

affect product safety, establish controls to prevent hazards, monitor perform-

ance of controls, and maintain records of such monitoring. Ongoing

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation I I7

research by the authors of this article is trying to establish why many firms

are exceeding government set standards, what the effect of these corporate

strategies is on public health, and how these measures are affecting

regulatory processes. Our research thus far has produced four arguments

explaining why firms may engage in over-compliance.

First, in many advanced industrialized countries the industrialization of

food production, longer supply chains, and periodic occurrences of food

safety problems have led to a consumer trust deficit. Food firms have sought

to address this deficit by adopting business strategies that enhance trust-

worthiness and enable firms to allocate blame and costs efficiently should one

of their products turn out to be unsafe or experience declining consumer

acceptance for other reasons. Many firms have addressed trust deficits

through branding, which involves a privatization of consumer trust. How-

ever, branding also involves a privatization of risk, particularly if firms move

from individual brand products to turning the entire firm into a brand. In

other words, branding shields food firms at least to some extent from food

safety problems caused by other firms - in the best case, brand producers

may even increase their market share as food safety problems with

non-brand products grow. On the downside, firms experiencing safety

problems with one of their own brand products cannot externalize the costs

involved to the entire food market. And they cannot free ride on positive

externalities generated by a generally safe food supply in the respective

market. This is why food firms relying on brand products are more interested

in tougher corporate food safety systems than non-brand firms and are more

willing to adopt strict HACCP and other food safety control measures. These

systems allow firms to partition, allocate, control and reduce risks throughout

the value chain. Surveys on the beef, poultry and dairy sectors in the United

States and other countries support the proposition that brand-product food

firms are the leaders in over-compliance.35

Firm size appears to play an important role in this context. Large firms,

particularly those in concentrated markets, have much more influence on

their suppliers than small firms. Thus they can impose quality standards

quicker, more effectively and at lower cost throughout their supply chain.

One indication for this is that HACCP has proven much harder to

implement in the seafood industry, which is less concentrated and more

disaggregated, than for example in the red meat and poultry sector. At the

same time, studies on the US meat and poultry sector show that only small

plants may at times benefit from skimping on food safety efforts. Larger

plants with poor quality controls have a higher probability of exiting the

market.36 Moreover, several studies have shown that marginal HACCP

implementation costs are lower for larger than for smaller firms. A I998

USDA study, for example, suggests that HACCP cost ratios for US

producers were 3:1 in the beef sector and io:i in pork production. At the

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

iI8 Thomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

same time, we observe a growing number of large plants at the expense of

small plants in both sectors, and large increases in margins. In the US

poultry sector, where HACCP implementation cost ratios are approximately

even, we observe less market concentration and a slower growth of

margins.37 Data such as this suggests that the introduction of HACCP may

be promoting industrial concentration. In any event we observe that in

concentrated markets, such as the food market, food safety systems of

advanced industrialized countries are increasingly driven by a few large

companies that are concerned about their brand reputation. Regulators are

struggling to follow up with formal standards that also smaller firms can

meet. Surveys on US and European food producers show that larger

companies have engaged in much more HACCP training of employees, are

more familiar with HACCP, have implemented HACCP earlier, and have

adopted HACCP at a much higher rate than smaller firms.38

Second, in the food market perceived safety problems are at least as

important as real risks because food is a credence good - consumers are

unable to reliably assess on their own the safety of such products. Firms may

thus have an incentive to enhance their competitiveness in this market by

signalling to consumers, through branding and other strategies, that my

products are safer than the products of other firms'. However, firms may also

have disincentives to pursue such a strategy. Emphasizing food safety as a

competitive issue could backfire by making consumers as a whole more

nervous about food safety. In addition, the firms involved may risk ending up

in an expensive race to the top in food safety standards. Interestingly, the

Global Food Safety Initiative (http://www.globalfoodsafety.com/) and other

private industry initiatives explicitly aim at limiting corporate competition on

food safety issues. This seems to indicate that at least some firms are

competing on food safety standards. Brand retailers also seem to worry that

if they excessively drive up standards by competing on food safety they may

lose market shares to food discounters - as long as governments are reluctant

to follow up and impose ever higher standards on all firms in the sector (see

also below).39

Third, in many countries sectoral consolidation has resulted in a small

number of very large food processors and retailers, often with global business

activity. Firms of this nature are forced to cope with multiple jurisdictions

involving a plethora of standards, tens of thousands of stores, and hundreds

of thousands of employees. Large firms thus have strong incentives to seek

private and/or public international food safety standards, such as HACCP,

so that they can implement the same standards in all plants and stores under

their control. Several studies suggest, furthermore, that implementing

HACCP may also produce economic efficiency gains for firms, notably, by

reducing costs of raw materials inspections, materials specification, raw

materials inventory and other input costs, as well as marketing and sales

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation i I9

costs. In any case, the preventive nature of HACCP appears more

cost-efficient than testing and then destroying or reworking products at the

end of the production and supply chain.40 While the first part of this

argument is reminiscent of propositions put forth by Vogel (I996), Murphy

(I995) and others, the latter part could be regarded as variant of the Porter

hypothesis.

Fourth, food firms may use private food safety standards (and over-

compliance more generally) to enhance their autonomy: adopting tougher

standards may motivate governments to 'leave firms alone' and not to adopt

and enforce tougher public standards - in other words, firms may buy

political legitimacy and public good-will through stricter private standards.

Over-compliance may also help firms in shielding themselves from vagaries

associated with changing government regulation and variation in enforce-

ment over time and jurisdictions. This argument contradicts parts of the first

argument and remains to be tested more fully. On the one hand, we have

evidence showing that in the United States large food producers pushed for

mandatory HACCP standards and their phase-in in I998, after having first

supported their industry associations' resistance against mandatory public

standards. Smaller businesses resisted the Pathogen Reduction/HACCP rule

issued by the USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service. With a view to

HACCP implementation cost ratios and changes in plant numbers and

margins (see above) one might argue that large firms have been using public

HACCP standards as a strategy of regulatory competition. On the other

hand, the first and fourth argument may not be fully incompatible: large

firms may have been pushing for higher standards that smaller firms find

harder to meet, but they may have sought standards that are still below the

private standards adopted by large firms - which leaves the latter firms with

sufficient autonomy and other benefits involved in meeting higher private

standards.

The corporate strategies discussed here have operated primarily at the

domestic level, but to some extent have also produced international trading

up effects. For example, the United States, in its regulation mandating

HACCP for seafood processors, stated that foreign firms exporting seafood

to the United States must meet these standards. The European Union has

issued similar regulation. We return to this issue in the concluding section.

Conclusion

Empirical research on national and international environmental and con-

sumer risk regulation shows that cases of declining regulatory stringency are

extremely rare, and that standards in most countries and policy-areas tend

to move upward (e.g., Vogel and Kagan 2002). There is evidence for

'regulatory chill' effects in some environmental and consumer policy areas,

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I20 Thomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduff

though it is usually difficult to demonstrate that in the absence of deregula-

tory pressure emanating from international market integration and compe-

tition particular environmental regulation would ceteris paribus have been

stricter and/or more effective.

Regulatory capture theory, public choice theory, theories of regulatory

federalism and trading up, as well as various types of interest group theory

and theories focusing on the characteristics of risks and regulatory issues offer

a wide range of explanations for why the infamous race-to-the-bottom has

not materialized. They also offer explanations for why observed regulatory

trajectories in open economies are usually pointing in the opposite

direction - towards stricter regulation. These theories fill important gaps in

explanations focusing on more fundamental (or 'ultimate' as opposed to

'proximate') driving forces of stricter environmental regulation. Such forces

include in particular economic growth, democracy, and the 'rights revolu-

tion' (Sunstein I990) or 'total justice' (Friedman I987) trend (that is, growing

public demand for environmental and public health protection). These

driving forces are, in part, a result of growing density, frequency and speed

of social and economic interaction across national boundaries and over ever

longer distances. They do not vary much between advanced industrialized

countries. Hence it is difficult to explain existing variation in regulatory

stringency in environmental policy among these countries in such terms.

In this article we have focused on endogenising public perceptions in an

interest group model that explains regulatory outcomes from the bottom up.

We have also focused on another bottom up explanation that has thus far

been largely ignored in the political science literature on regulation, i.e.,

corporate environmental performance strategies and their effect on regula-

tion. These explanations, whose empirical plausibility was illustrated with

three case studies, will have to be developed further and tested more

systematically. They add to and refine rather than substitute for existing

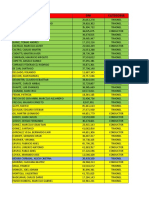

explanations. Figure i shows that more sophisticated explanations incorpor-

ating public perceptions, NGO activity, and corporate behaviour can help

not only in explaining increasing domestic regulatory stringency, but also

international trading up processes.

We have focused largely on processes summarized on the left side of

Figure II. However, the large box in the middle of the figure lists political and

market mechanisms as well as enabling conditions that contribute to the

diffusion of stricter environmental standards from one country to another.

Public perceptions, interest group politics and corporate behaviour play a

key role in several of these mechanisms.

Political mechanisms. (a) The willingness and ability of country A to

exclude products from countries with laxer regulation depends in large

measure on support by the public (consumers), environmental interest

groups, and 'green' companies in A. (b) As to process regulation, where

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Pressure Group Politics, Economic Competition and Regulation I21

Public concerns over an environmental or consumer issue

=> NGO pressure via politics and markets

+

Rent seeking by fmns through stricter regulation

+

Corporate environmental performance strategies

Stricter regulation in State A

Political mechanisms => trading up

> B's product exports to A suffer unless B adapts to A's regulation (this mechanism, which involves

enforcement through market access restrictions, is less effective in process regulation due to

WTO, EU and other international constraints, and because process regulation has primarily

indirect and less visible effects on production costs). B's incentive to adapt is a function of B's

cost of raising regulatory standards and the opportunity cost of reduced exports to A. Firms in B

that are able to meet higher standards of A push for stricter rules in B to lock in this advantage

vis-a-vis other firms in B, and to benefit from economies of scale in not having to produce

according to different standards in A and B.

> Firms in state A experience a competitive disadvantage vis-a-vis firms in state B because of strict

regulation in A and lax rules in B (contingent on the size of compliance costs). They push A's

government to establish an international level playing field. Firms from A will push for trading up

in B so that transaction cost benefits due to similar regulation in A and B and improvements in

competitive position due to forcing firms in B to comply with stricter rules are eventually higher

than production cost increases due to stricter regulation in state A.

> NGOs from A form coalitions with NGOs from B and, bilaterally or through international

institutions, push B's government toward stricter regulation.

> Laxer regulation in B creates externalities for the public in A (e.g., pollution). A's government

thus pressures government B bilaterally or through international institutions to install stricter

regulation.

> Firms from A operating in B push B's government toward establishing stricter regulation to obtain

a competitive advantage over firms in B (firms from A already have the necessary technology and

assets in place to comply).

Market mechanisms => trading up

> Firms from A operating in B have incentives to use the same strict standards in A and B because

of reputation costs (e.g., pressure by NGOs in A and/or B), liability reasons, or operational

reasons (e.g., economies of scale, reduced transactions costs, expected benefits from environmental

performance strategies).

> Firms in B emulate corporate environmental performance strategies of firms from A because they

anticipate competitive advantages over other firms in B (and A).

> For reputation, liability, operational or other reasons firms from A do not do business with "dirty"

firms from B. This motivates firms from B to adapt to industry standards and government

regulation in A.

Enabling conditions

> A has a larger market than B.

> B is able to monitor and enforce compliance with stricter regulation.

> The government and firms in B are able to meet the cost of stricter regulation. If not A is willing

to fund at least some environmental improvement measures in B.

> International or transnational institutions are available to reduce transactions costs of negotiating

and implementing international standards, and to exchange technical know-how, knowledge on

beneficial effects of environmental performance strategies, and environmental values.

> Relevant industry is concentrated.

> Moderate to high asset-specificity (sunk costs, low mobility).

Stricter regulation in State B

FIGURE I Trading Up Mechanisms

This content downloaded from

13.239.75.78 on Thu, 19 Jan 2023 07:00:16 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I22 Thomas Bernauer and Ladina Caduf