Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Randomized Trial To Alleviate RT Induced Mucositis

Randomized Trial To Alleviate RT Induced Mucositis

Uploaded by

Ramses HerreraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Randomized Trial To Alleviate RT Induced Mucositis

Randomized Trial To Alleviate RT Induced Mucositis

Uploaded by

Ramses HerreraCopyright:

Available Formats

2193

A Randomized Trial of a Nonabsorbable Antibiotic Lozenge Given to Alleviate Radiation-Induced Mucositis

Scott H. Okuno, M.D.1 Robert L. Foote, M.D.1 Charles L. Loprinzi, M.D.1 Sunil Gulavita, M.D.2 Jeff A. Sloan, Ph.D.1 Julie Earle, R.N.1 Paul J. Novotny, M.S.1 Mary Burk, R.N.1 Albert R. Frank, M.D.3

1

BACKGROUND. The objective of this study was to determine whether a nonabsorbable antibiotic lozenge could alleviate radiation-induced oral mucositis. METHODS. Patients scheduled to receive radiation therapy to more than one-third of the oral cavity mucosa were selected for the study. After stratication, patients were randomized to receive either a nonabsorbable antibiotic lozenge or a placebo. Both groups were then evaluated for mucositis by health care providers and selfreport instruments. RESULTS. Fifty-four patients were randomized to receive the antibiotic lozenge and 58 to receive the placebo. There were no substantial differences or trends in mucositis scores between the two study arms as measured by the health care providers. However, the mean patient-reported mucositis score and the duration of patient-reported Grade 34 mucositis were both lower in the patients randomized to the antibiotic lozenge arm (P 0.02 and 0.007, respectively). CONCLUSIONS. This prospective, controlled trial provides evidence to suggest that a nonabsorbable antibiotic lozenge can decrease patient-reported radiation-induced oral mucositis to a modest degree. Nonetheless, this evidence does not appear to be compelling enough to recommend this treatment as part of standard practice. Cancer 1997;79:21939. 1997 American Cancer Society.

Mayo Clinic and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota.

2

Thunder Bay Regional Cancer Centre, Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada, an afliate of Duluth Community Clinical Oncology Program, Duluth, Minnesota.

3

Nebraska Oncology GroupCreighton University, University of Nebraska Medical Center, and Associates, Omaha, Nebraska.

KEYWORDS: mucositis, radiation, antibiotic lozenge, head and neck carcinoma, placebo-controlled trial.

M

Conducted as a collaborative trial of the North Central Cancer Treatment Group and Mayo Clinic. Presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, PA, May 1821, 1996. Supported in part by Public Health Service grants CA-25224, CA-37404, CA-15083, CA-35269, CA52352, CA-35101, CA-60276, CA-37417, CA35195, CA-35448, CA-35103, and CA-35415. Additional participating institutions include: Cedar Rapids Oncology Project CCOP, Cedar Rapids, Iowa (Martin Wiesenfeld, M.D.); Iowa On-

ucositis is a major toxicity associated with radiation therapy administered to the oral cavity.1 Mouth soreness and ulceration can be quite painful, frequently requiring the use of analgesic medications. It may interfere with a patients ability to maintain an adequate

cology Research Association CCOP, Des Moines, Iowa (Roscoe F. Morton, M.D.); Rapid City Regional Oncology Group, Rapid City, South Dakota (Larry P. Ebbert, M.D.); Mayo Clinic Scottsdale CCOP, Scottsdale, Arizona (Robert F. Marschke Jr., M.D.); Saskatoon Cancer Centre, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada (Andrew W. Maksymiuk, M.D.); CentraCare Clinic, St. Cloud, Minnesota (Harold E. Windschitl, M.D.); Meritcare Hospital CCOP, Fargo, North Dakota (Ralph Levitt, M.D.); Carle Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program, Urbana, Illinois (Alan K. Hateld, M.D.); Geisinger Clinical Oncology Program,

Danville, Pennsylvania (Suresh Nair, M.D.); Grand Forks Clinic, Ltd., Grand Forks, North Dakota (John A. Laurie, M.D.); Siouxland Hematology-Oncology Associates, Sioux City, Iowa (John C. Michalak, M.D.); and Toledo Community Clinical Oncology Program, Toledo, Ohio (Paul L. Schaefer, M.D.). Address for reprints: Charles Loprinzi, M.D., Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street, SW, Rochester, MN 55905. Received November 1, 1996; revision received January 23, 1997; accepted January 23, 1997.

1997 American Cancer Society

/ 7b57$$1102

05-05-97 13:35:53

canxas

W: Cancer

2194

CANCER June 1, 1997 / Volume 79 / Number 11

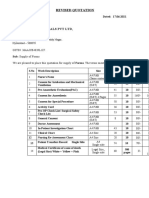

TABLE 1 Mucositis Grading Criteria

Grade 0 1 2 3 4 Criteria No mucositis Soreness/erythema Erythema/ulcers/able to eat solids Ulcers/required liquid diet only Alimentation not possible

TABLE 2 Distribution of Baseline Factors

Antibiotic lozenge (n 54) Placebo preparation (n 58)

Baseline factors Denturesa Yes No Smoking historya None Yes, currently Past only Planned radiation dose (grays) 30.0044.99 45.0050.00 50.0160.00 60.00 Planned uoride usea Yes No Amount of oral mucosa in the radiation elda 1/3 to 2/3 2/3 Gender Female Male Alcohol use None Social Heavy Age (yrs) Median Mean

a

P value

27 27 13 5 36

27 31 15 8 35

0.85

0.72

1 4 15 34 33 21

0 4 20 34 36 22

0.77

FIGURE 1. Mean mucositis score as determined by health care providercompleted questionnaires for patients in (A) the four treatment arms and (B) the pooled antibiotic lozenge and placebo groups.

0.99

43 11 17 37 28 22 4 61 59

45 13 19 39 25 29 4 65 62

0.82

0.99

0.44

0.38

Stratication factors.

of certain human tumors, particularly squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck region.2 12 There are no established measures for preventing radiation-induced mucositis in humans. A recent pilot trial involving a lozenge containing a combination of three relatively nonabsorbable antibiotics (tobramycin, polymyxin E, and amphotericin B) in 15 patients undergoing radiation therapy to their oral cavities reported strikingly less mucositis relative to comparable historic controls.13 Additional pilot information with this approach was also promising.14 This article describes the results of a trial designed to prospectively evaluate this potential therapy in a placebo-controlled manner.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

intake of food and liquids. Severe mucositis may require temporary or permanent cessation of radiation therapy prior to completion of the planned radiation treatment program. There is strong clinical and radiobiologic evidence that protraction of overall treatment time has an adverse inuence on the radiocurability

Patient Eligibility Adult patients considered for entry onto this clinical trial must have been scheduled to receive radiation therapy at a North Central Cancer Treatment Groupapproved radiation oncology facility. At least one-third of the oral cavity mucosa needed to be included in the

/ 7b57$$1102

05-05-97 13:35:53

canxas

W: Cancer

Antibiotic Lozenge for Radiation-Induced Mucositis/Okuno et al.

2195

FIGURE 3. Mean mucositis scores as determined by patient-completed FIGURE 2.

Percent of patients with severe or very severe mucositis as determined by health care provider-completed questionnaires for patients in (A) the four treatment arms and (B) the pooled antibiotic lozenge and placebo groups. questionnaires for patients in (A) the four treatment arms and (B) the pooled antibiotic lozenge and placebo groups.

TABLE 3 Measures of Mucositis Evaluated by Health Care Provider

Antibiotic lozenge (n 54) (n 49) 7 21 17 4 (n 49) 1.48 Placebo preparation (n 58) (n 54) 6 16 27 5 (n 54) 1.56

Efcacy variable Maximum mucositis Mild Moderate Severe Very severe Overall mean weekly mucositis scorea Mean number of weeks of severe and very severe mucositis

P value 0.16

radiation therapy elds, and the planned dose must have been the following values: 1) 45 grays (Gy) using 1.20 2.20 Gy per fraction, or 2) 30 Gy using 3.0 Gy per fraction. Patients were required to be entered onto the study before the fourth fraction of radiation therapy. Patients were ineligible for this study if they had open mouth sores at study entry, had received prior radiation therapy to the oral mucosa, were receiving concomitant chemotherapy, or were using other prophylactic drugs or mouthwashes (with the exception of alkaline saline solutions).

0.85

(n 49) 1.04

(n 54) 1.31

0.18

Mean weekly mucositis score was the sum of all weekly mucositis scores divided by the total number of weeks reported.

Study Design Patients were stratied before randomization by the following: 1) whether they wore dentures; 2) smoking history; 3) planned total radiation therapy dose; 4) planned use of uoride (more than using a uoride toothpaste); and 5) the amount of the oral mucosa in the radiation eld ( vs. two-thirds). In addition, information was collected regarding the use of alcohol, although this was not used as a stratication factor. Patients were subsequently randomized to 3 treatment arms: 1) a chlorhexidine mouthwash, 15 mL, 4 times daily (used as a 30-second mouth rinse, then

/ 7b57$$1102

05-05-97 13:35:53

canxas

W: Cancer

2196

CANCER June 1, 1997 / Volume 79 / Number 11 TABLE 4 Measures of Mucositis Evaluated by Patients

Antibiotic lozenge (n 54) (n 52) 2 5 6 35 4 (n 52) 1.61 (n 52) 2.71 Placebo preparation (n 58) (n 56) 4 3 2 39 8 (n 56) 1.95 (n 56) 3.70

Efcacy variable Maximum mucositis None Mild Moderate Severe Very severe Overall mean weekly mucositis scorea Mean number of weeks of severe and very severe mucositis

P value 0.21

0.02

0.04

Mean weekly mucositis score was the sum of all weekly mucositis scores divided by the total number of weeks reported.

FIGURE 4. Percent of patients with severe or very severe mucositis as

determined by patient-completed questionnaires for patients in (A) the four treatment arms and (B) the pooled antibiotic lozenge and placebo groups.

expectorated without swallowing) throughout the period of radiation therapy and for 2 weeks thereafter; 2) a placebo mouthwash, which appeared identical to the chlorhexidine mouthwash and was used in the same schedule; or 3) an oral nonabsorbable antibiotic lozenge comprised of 10 mg of amphotericin B, 1.8 mg of tobramycin, and 20 mg of polymyxin E. Patients were instructed not to eat or drink for 30 minutes after each lozenge or mouthwash. If the treatment assignment was to either of the mouthwash arms, only a coded bottle number was communicated to the treatment center. A planned interim analysis performed after 75 patients (50% of planned accrual) had been entered discovered that the chlorhexidine arm appeared detrimental. This portion of the study subsequently was closed and reported.15 The protocol was then modied to delete the mouthwash arms but to assess the lozenge in a double-blinded manner because results for the nonblinded antibiotic lozenge arm appeared promising (compared with the placebo mouthwash). An identical-appearing placebo lozenge was developed, and subsequent patients were randomized to receive anti-

biotic versus placebo lozenges in a traditional doubleblinded, two-arm design. Lozenges were to be sucked until they completely dissolved and were to be administered four times daily throughout radiation therapy and for two subsequent weeks. Nothing was to be taken orally for 30 minutes after each dose. Each patient was given oral and written instructions at study entry regarding standard mouth care procedures during the course of radiation therapy. These included instructions to drink 6 to 8 glasses of water per day, to brush the teeth after each meal with a soft toothbrush and a noncommercial toothpaste, to rinse and cleanse the oral cavity every 2 hours throughout the day with either the study mouthwash (for 4 doses per day for those assigned to receive a mouthwash) or a solution containing one-half teaspoon salt and one-half teaspoon baking soda mixed in a large glass of warm water, and to avoid such products as commercial mouthwashes, tobacco, alcoholic beverages, very hot, cold, or spicy foods, acidic foods, fruit drinks, and hard or coarse foods. It was recommended that patients be evaluated by a dentist prior to beginning radiation therapy. Patients were to be examined by a radiation oncologist or radiation oncology nurse at least weekly to grade their oral mucositis according to World Health Organization criteria (Table 1).16 In addition, patients were requested to ll out questionnaires (by which they scored their own mucositis) on a weekly basis throughout the course of radiation therapy and for 4 weeks thereafter. The patients weight, use of analgesic agents, antibiotics, antifungal agents, mouthwashes

/ 7b57$$1102

05-05-97 13:35:53

canxas

W: Cancer

Antibiotic Lozenge for Radiation-Induced Mucositis/Okuno et al.

2197

other than the study mouthwash, and tube feedings, as well as treatment interruptions and length of interruptions, were documented. The original accrual goal was to enter 50 assessable patients into each of the study arms so that a onesided 0.02-level Wilcoxon test comparing the study agent against a placebo would have 90% power to detect reductions in mucositis severity considered clinically meaningful. Specically, a clinically signicant effect was dened as obtaining results such that half the study agent mucositis grades were identical to the placebo grades and the other half were one class less severe, e.g., mild rather than moderate. The distributions of baseline factors were compared between the two treatment arms using Fishers exact test for categoric variables and Wilcoxon tests for ordinal level data. Between May 1991 and April 1993, 29 patients were randomized to receive the unblinded antibiotic lozenge, 25 patients were randomized to receive the chlorhexidine mouthwash, and 31 patients were randomized to receive a placebo mouthwash. Between October 1993 and July 1994, another 26 patients were randomized to receive the blinded antibiotic lozenge, whereas 27 patients were assigned to receive the blinded placebo lozenge. One patient on the unblinded antibiotic lozenge arm was determined to be ineligible. Hence a total of 112 eligible patients were randomized to receive antibiotic lozenges (54 patients) versus a placebo preparation (58 patients). Toxicity and efcacy measures were compared between the blinded placebo lozenge (n 27) and blinded antibiotic lozenge (n 26) groups. Subsequent comparisons were made between the blinded and unblinded antibiotic lozenge to determine whether blinding had any impact on efcacy or toxicity. Cross-validation of placebo results were performed by comparing the placebo lozenge and placebo mouthwash groups. Finally, pooling of both of the placebo groups (mouthwash and lozenge) and both of the antibiotic lozenge groups (blinded and unblinded) was performed because no signicant differences were found in the previous two procedures. This allowed for an omnibus verication of placebo versus antibiotic lozenge with increased sample size and power. Toxicity was measured by the incidence of patient-reported or health care provider-observed side effects and by measures derived from the patient questionnaires. These were comprised of 1) the maximum grade of burning, discomfort, or pain caused by the study medication; 2) the maximum grade of taste alteration; 3) the maximum grade of teeth staining; and 4) an incidence measure as to whether the patient be-

lieved that the study medication was producing any side effects. Treatment efcacy was compared in terms of the maximum severity and duration of mucositis and the average daily level of mucositis. The percentage of time with severe or very severe mucositis and area under the curve (AUC) of reported mucositis over the course of the study were also used as measures of treatment effectiveness. The distributions of these effect variables were compared among the treatment arms by log rank testing for the duration of mucositis, Fishers exact test for categoric variables, and Wilcoxon tests for the ordinal level data. Because multiple variables were used to assess efcacy, the authors applied the OBrien Global Test17 to provide a single P value simultaneously comparing the two pooled arms with respect to maximum mucositis severity reported by the patient and the health care provider, the average weekly mucositis grade reported by the patient and the health care provider, the percentage of days with severe/very severe pain reported by the patient and the health care provider, the area under the patient-reported mucositis curve, and the number of breaks in radiation therapy.

RESULTS

Because the initial study goal was to have 50 patients per study arm, the major planned analysis was a comparison between the patients who were randomized to receive the antibiotic lozenge arm (n 54) versus those randomized to receive the placebo (n 58). That is, the unblinded lozenge data from the rst study would be combined with the blinded lozenge data from the second study and the placebo mouthwash data from the rst study would be combined with the placebo lozenge data from the second study unless there was convincing evidence of their noncomparability. Table 2 summarizes the baseline patient characteristics of the two pooled treatment groups. No substantial differences in any of these characteristics were found. Moreover, equivalent proportions (64%) of the patients in the two groups completed the planned study therapy. Mucositis severity data reported by the health care providers are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 and summarized in Table 3. These show that there were no substantial differences or substantive trends in mucositis scores as measured by health care providers either among the four treatment arms or between the two pooled treatment groups. Furthermore, there were no differences in the number or duration of radiation therapy interruptions.

/ 7b57$$1102

05-05-97 13:35:53

canxas

W: Cancer

2198

CANCER June 1, 1997 / Volume 79 / Number 11

Patient-reported mucositis scores are illustrated in Figures 3 and 4 and summarized in Table 4. Although the mucositis scores in the unblinded lozenge arm were generally lower that those in the other arms, they were not quite signicantly different from those in the blinded lozenge arm (AUC P 0.06). Because there was no signicant difference in the mucositis scores in the 2 placebo arms (AUC P 0.14), the planned pooled analysis was performed. The mean weekly mucositis score of the patients in the pooled lozenge group was 1.6 versus 2.0 for the pooled placebo group (P 0.02). In addition, the antibiotic lozenge patients scored themselves as having a shorter duration of Grade 3 4 mucositis (median 2.7 weeks vs. 3.7 weeks; P 0.04). The OBrien Global Test17 combining the results of all the efcacy measures into a single comparison between the pooled antibiotic lozenge and pooled placebo groups indicated a statistically superior efcacy for the pooled antibiotic lozenge group (P 0.02). Toxicities were assessed primarily by open-ended questions on the weekly questionnaires. The few nausea/upset stomach reports were observed in equivalent numbers in both pooled groups. There were no reports of diarrhea on any of the treatment arms. Currently, there is no established prophylactic method to decrease radiation-induced oral mucositis. Furthermore, despite preliminary data suggesting that chlorhexidine could decrease radiation-induced mucositis,18,19 the authors recently reported doubleblind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial failed to determine any benet for the chlorhexidine mouthwash.15 Pilot data from two sources suggested that nonabsorbable antibiotic lozenges, similar to those utilized in this trial, could reduce radiation-induced mucositis.13,14 In the current trial, the authors did not observe any signicant trend in the mucositis scores judged by the health care providers, and the antibiotic lozenges did not alter the incidence or duration of radiation therapy interruptions. However, signicantly lower mucositis scores were reported by the patients in the pooled lozenge group. The magnitude of patient-reported benet for the antibiotic lozenge was modest, reducing the patient-reported mucositis score by one ordinal level (e.g., from moderate to mild) and shortening the duration of severe mucositis by 1 week. Similar results were observed by Symonds et al.20 In their study using antibiotic lozenges versus placebo in 275 patients undergoing radiation therapy, they found improved patient-reported maximum mucositis; a decrease in the severity of dysphagia, distribution, and

area of mucositis; and less weight loss in the antibiotic lozenge arm. In summary, although the magnitude of benet appears modest at best, there is some evidence suggesting that the use of nonabsorbable antibiotic lozenges may alleviate patient-reported mucositis associated with radiation therapy. However, it is not clear whether these antibiotic lozenges should be established as part of standard clinical practice, given the modest patient-reported benet, the lack of health care provider-reported benet, and the unblinded study design for the rst half of this trial.

REFERENCES

1. Rothwell BR, Haglund W, Morton TH. Prevention and treatment of the orofacial complications of radiotherapy. J Am Dent Assoc 1987;114:31622. Budihna M, Skrk J, Smid L, Furland L. Tumor cell repopulation in the rest interval of split-course radiation treatment. Strahlenther Onkol 1980;156:4028. Trott KR. Cell population and overall treatment time. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1990;19:10715. Withers HR, Taylor JM, Maciejewski B. The hazard of accelerated tumor clonogen repopulation during radiotherapy. Acta Oncol 1988;27:1316. Parsons JT, Bova FJ, Million RR. A re-evaluation of splitcourse technique for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1980;6:164552. Awwad HK, Khafagy Y, Barsoum M, Ezzat S, el-Attar I, Farag H, et al. Accelerated versus conventional fractionation in the postoperative radiation of locally advanced head and neck cancer: inuence on patient tumor proliferation. Radiother Oncol 1992;25:2616. Amdur RS, Parsons JT. Split-course versus continuouscourse irradiation in the postoperative setting for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989;17:27985. Cox JD, Pajak TF, Asbell S, Russell AH, Pederson J, Byhardt RW, et al. Interruptions adversely affect local control and survival with hyperfractionated radiation therapy of carcinomas of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts. New evidence of accelerated proliferation from Radiation Therapy Oncology Group protocol 8313. Cancer 1992;69:27448. Overgaard J, Hjelm-Hansen M, Johansen LV, Andersen AP. Comparison of conventional and split-course radiotherapy as primary treatment in carcinoma of the larynx. Acta Oncol 1988;27:14752. Fowler JF, Lindstrom MJ. Loss of local control with prolongation in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1992; 23:45763. Pajak TF, Laramore GE, Marcial VA, Fazekas JT, Cooper J, Rubin P, et al. Elapsed treatment days a critical time for radiotherapy quality control review in head and neck trials: RTOG report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991; 20:13 20. Maciejewski B, Preuss-Bayer G, Trott KR. Head and neck tumors: decreased local control by elongation of treatment time. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1983;9:3218. Spijkervet FK, Vermey A, Panders AK. Prevention of irradiation mucositis in head and neck cancer patients. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1990;9:174.

2.

3. 4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

/ 7b57$$1102

05-05-97 13:35:53

canxas

W: Cancer

Antibiotic Lozenge for Radiation-Induced Mucositis/Okuno et al.

14. Spijkervet FK, Van Saene HK, Van Saene JJ, Panders AK, Vermey A, Mehta DM, et al. Effect of selective elimination of the oral ora on mucositis in irradiated head and neck cancer patients. J Surg Oncol 1991;46:16773. 15. Foote RL, Loprinzi CL, Frank AR, OFallon JR, Gulavita S, Tewk HH, et al. Randomized trial of a chlorhexidine mouthwash for alleviation of radiation-induced mucositis. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:26303. 16. Spijkervet FK, Van Saene HK, Panders AK, Vermey A, Mehta DM. Scoring irradiation mucositis in head and neck cancer patients. J Oral Pathol Med 1989;18:16771. 17. OBrien PC. Procedures for comparing samples with multiple endpoints. Biometrics 1984;40:107987.

2199

18. Samaranayake LP, Robertson AG, MacFarlane TW, Hunter IP, MacFarlane G, Soutar DS, et al. The effect of chlorhexidine and benzydamine mouthwashes on mucositis induced by therapeutic irradiation. Clin Radiol 1988;39:2914. 19. Ferretti GA, Ash RC, Brown AT, Parr MD, Romond EH, Lillich TT. Control of oral mucositis and candidiasis in marrow transplantation: a prospective, double-blind trial of chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse. Bone Marrow Transplant 1988;3:48393. 20. Symonds RP, McIlroy P, Khorrami J, Paul J, Pyper E, Lindemann E, et al. The reduction of radiation mucositis by selective decontamination antibiotic pastilles: a placebo-controlled double-blind trial. Br J Cancer 1996;74:3127.

/ 7b57$$1102

05-05-97 13:35:53

canxas

W: Cancer

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Review Test #1-Malinda SirueDocument2 pagesReview Test #1-Malinda SirueEsmareldah Henry SirueNo ratings yet

- Grievance Status RMLDocument1 pageGrievance Status RMLMayankNo ratings yet

- Preoperative ReportDocument33 pagesPreoperative ReportJay VillasotoNo ratings yet

- Arjun Pts Orem - Sumitra DeviDocument13 pagesArjun Pts Orem - Sumitra DeviChandan PradhanNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1713249Document13 pagesNihms 1713249Achilles Fkundana18No ratings yet

- Inj July 2010Document37 pagesInj July 2010TamilNurse.comNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation of Sports Injuries - Scientific BasisDocument338 pagesRehabilitation of Sports Injuries - Scientific Basisjimitkapadia100% (3)

- Lecture 10 - ICF International Classification of Functioning, Disability & HealthDocument6 pagesLecture 10 - ICF International Classification of Functioning, Disability & HealthSarahNo ratings yet

- TOEIC - Intermediate Anatomy, Health, and Beauty Vocabulary Set 2 PDFDocument6 pagesTOEIC - Intermediate Anatomy, Health, and Beauty Vocabulary Set 2 PDFNguraIrunguNo ratings yet

- CM-1092-01 - Module 07Document38 pagesCM-1092-01 - Module 07Hoa Linh GMPNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae 2013Document5 pagesCurriculum Vitae 2013Sharif CruzNo ratings yet

- Mun CV 09-2021Document12 pagesMun CV 09-2021api-564004041No ratings yet

- NCO-codes: Occupation Name Family - NameDocument4 pagesNCO-codes: Occupation Name Family - NameVasavi ComputersNo ratings yet

- Pengetahuan Dan Persepsi Peserta Prolanis Dalam Menjalani Pengobatan Di PuskesmasDocument7 pagesPengetahuan Dan Persepsi Peserta Prolanis Dalam Menjalani Pengobatan Di PuskesmasUmmulAklaNo ratings yet

- Topic Outline: - Put Forth A Set of HealthDocument4 pagesTopic Outline: - Put Forth A Set of HealthJohannaNo ratings yet

- Brungi Hospital QuotationDocument2 pagesBrungi Hospital QuotationPurchase PNo ratings yet

- Welch Allyn Home Hypertension Program Infographic PosterDocument1 pageWelch Allyn Home Hypertension Program Infographic PosterBerto YomoNo ratings yet

- Public Health Nurse-District Family Welfare Bureau: Job DescriptionDocument7 pagesPublic Health Nurse-District Family Welfare Bureau: Job DescriptionNamgay LhamNo ratings yet

- Verification of Medical Condition(s) : Instructions For The Customer Information For The DoctorDocument3 pagesVerification of Medical Condition(s) : Instructions For The Customer Information For The DoctorElise SloperNo ratings yet

- Roles of Pharmacist in Different Practice SettingDocument7 pagesRoles of Pharmacist in Different Practice Settingamber castilloNo ratings yet

- Evolving Regulatory Perspectives On Digital Health Technologies For Medicinal Product DevelopmentDocument11 pagesEvolving Regulatory Perspectives On Digital Health Technologies For Medicinal Product DevelopmentNot 8No ratings yet

- ECA Cancel Client List Updated 27th MarchDocument3 pagesECA Cancel Client List Updated 27th MarchChaitali DegavkarNo ratings yet

- IMAP Citizens Charter FinalDocument9 pagesIMAP Citizens Charter FinalphenorenNo ratings yet

- Admission LetterDocument1 pageAdmission LetterSam Udayakumar BinithaNo ratings yet

- Florence NightingaleDocument33 pagesFlorence NightingaleTisay CantalNo ratings yet

- Lec 10 MidtermsDocument1 pageLec 10 MidtermsMitzi AngelaNo ratings yet

- Short Assignment 2 by ITPPDocument5 pagesShort Assignment 2 by ITPPumair dogarNo ratings yet

- Various Attachments Used in Prosthodontics-A Review: November 2018Document5 pagesVarious Attachments Used in Prosthodontics-A Review: November 2018harshita parasharNo ratings yet

- Letter 1Document4 pagesLetter 1YeetクモNo ratings yet