Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pages - Thesis - From Graybosch

Pages - Thesis - From Graybosch

Uploaded by

Sutan Adam0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views25 pagesOriginal Title

Pages _Thesis_ From Graybosch

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views25 pagesPages - Thesis - From Graybosch

Pages - Thesis - From Graybosch

Uploaded by

Sutan AdamCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 25

wr

|

Chaptor Fourloen Hislory of Philosophy Papers 281

3. Reference page or bibliography

Abstracts, tables of contents, and appendices are not normally needed.

14.5 ASAMPLE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY

PAPER

Hobbes, Locke, and the State of Nature Theories:

A Reassessment*

Michael P. Greeson

University of Central Oklahoma

Most of the great works in political philosophy were

written as a response to or as a result of a particular his-

torical context. As Hegel points out, whatever happens to

the philosopher, each individual is “a child of his time.-!

If this be true, the 17th century provided ample cause for

philosophic reflection: the turmoil of civil war and violent

shifts of political power, combined with a new intellectual

climate that emphasized science and reason over supernatural

explanation helped to cultivate the thoughts and passions of

many brilliant political philosophers.

‘Two of the most critical and influential of these

thinkers were Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. For both philoso-

phers, political society. in its most general sense, was the

result of certain fundamental human motivations, a natural

extension of certain metaphysical first principles of the

universe. Natural rights theorists from Hobbes to Kant (and

*This is the original paper submitted as 3 class asignment. A substantially revised version of this

Paper was published as “Hobbes, Locke, and the State of Nature Theones: A Reawessment” in Episteme

Vol. 5, May 1994, 1-15.

282

Part Four Specific Philosophy Writing Assignments

even more recently Rawls) typically have claimed to discover

the most universal features of human beings by means of a

kind of thought experiment, hypothetically stripping or peel-

ing away everything we have acquired through the influence of

custom, history, and tradition in order to discover the pre-

political state of nature and the natural man behind it,?

Both Hobbes and Locke utilize this “state of nature”

construct to elucidate their views on human nature and poli-

tics.’ Yet the common conception of their views of man‘s

original condition in the state of nature is usually con-

trasted: the political philosophy of the Second Treatise

paints man as a “pretty decent fellow,” far removed from the

quarrelsome, competitive, selfish creatures found in Hobbes’

Leviathan. Lockean man seems to be more naturally inclined

to civil society, supposedly more governed by reason. From

this interpretation of human nature, it follows logically

that the state of nature was no “condition of war" and anar-

chy as Hobbes has argued.‘

Locke states in the Second Treatise

Where we have the plain difference between the state

of nature and the state of war, however some men have

confounded [Locke’s reference here is probably to .

Hobbes’ concept of the state of nature as being

‘identical’ with the state of war], are as far dis-

tant as a state of peace, goodwill, mutual assistance

and preservation, and a state of enmity, malice, vio-

lence, and mutual destruction are one from another.*

It is my contention that although Locke painstakingly

attempts to disassociate himself with the Hobbesian notion

Chaplor Fourloon History of Philosophy Papers 283

of the “self-interested man” in a perpetual “state of war,”

the execution of this attempt falls short, and can even be

recognized to implicitly (not explicitly) contain the v

reasoning that Hobbes utilizes to advocate the movem:

tof

man from the “state of nature" to civil society.

In order to demonstrate the truth of this contention, I

will briefly outline the development of their philosophies,

and offer both a reinterpretation of the Hobbesian state of

nature, and a critical analysis of Locke’s view of the state

of nature in the Second Treatise.

Hobbes: Method and Problem

Thomas Hobbes is thought to have been influenced by such '

Enlightenment luminaries as Galileo, René Descartes, and

Francis Bacon. Though the influence of Bacon is often held

in highest standing, his teachings left little trace on 5

Hobbes’ own matured thought. Hobbes barely mentions Bacon in

his own writings and has no real place for “Baconian induc-

tion" in his own concept of scientific method.*

Scientific method, for Hobbes, has two branches: synthe- ;

sis, or deductive logic, and analysis, or inductive logic

[this is contrary to contemporary logical distinctions, in \

that “synthetic” truths are usually said to be the result of

inductive argument--"analytic” truths are said to be the re-

Sult of deductive relations]; only the former, the purely

deductive type of reasoning, is rigidly certain and yields

“perfectly determinate” conclusions.’ Hobbes was particu-

appropriated from Galileo. According to this method, complex

larly taken with the resolutio-compositive method, which he 1 !

|

phenomena are broken down into their simplest natural mo- |

,

i

|

F a

284

Part Four Specific Philosophy Writing Assignments

tions and components. Once these elements are understood,

the workings of complex wholes are easily derived. Hobbes’

intent was to develop a systematic study in three parts,

starting with simple motions in matter (De Corpore), moving

to the study of human nature (De Homine), and finally to

politics (De Cive), each based, respectively, on a lower

level of analysis.* Hence, reality for Hobbes is reducible

to mechanistic and material principles, or, simply stated,

bodies in motion. If we are to understand politics, we

should look at such phenomena in terms of the relationships

between men in motion.

Furthermore, Hobbes adopted the Galilean proposition

that that which is in motion continues in motion until al-

tered by some other force [of course, this is a theoretical

assumption which, independently, cannot be proven true or

false, since all we do observe are bodies that are acted upon

by such forces]. Likewise, Hobbes assumed that human beings

act voluntarily based upon their passions, until resisted by

another force or forces. This outward motion of the individ-

ual is the first beginning of voluntary motion, which Hobbes

calls “endeavor.” Insofar as this voluntary motion creates

vital, physical motion, endeavor is directed toward an ob-

ject, as so is called “appetite” or "desire." Insofar as this

voluntary motion hinders vital motion, endeavor is directed

away from the object, and is called “aversion. *?

The several passions of man are “species” of desires and

aversion, and directed toward those objects whose effects

enhance vital motion, and away from those objects which im-

pede vital motion. Thus, Hobbes conceives men to be self-

—_ . . =. =. -

Chapler Fourteen History of Philosophy Popors 285

maintaining engines whose motion is such that it enables

them to continue to "move" as long as continued motion is

possible.”

From this account of vital and voluntary motion, it log-

ically follows, at least according to Hobbes, that each man

in the state of nature seeks, and seeks only, to preserve

and strengthen himself. A concern for continued well-being

is both the necessary and sufficient ground of human action;

hence, man is necessarily selfish."' :

It is this perpetual endeavor for self-preservation

within the state of nature which gives rise to a condition

of war. Hobbes believes that men, being originally all equal

in the “faculties of the body and mind,*"? equally hope to

fulfill their ends of vital motion. Hence, if "two men de-

sire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both

enjoy, they become enemies,’ for both, knowing natural law

(i.e., natural moral law, as opposed to natural physical

law), would be privy to the unconditional, absolute, and

categorical command (or right) to preserve oneself at all

cost. This state of war encompasses all, “everyone against

everyone.“!* And without a common power to police them and

settle disputes, man is in a perpetual condition of war:

“war consisting not only in battle, or in the act of fight-

ing, but in a willingness to contend by battle being suffi-

ciently recognized.*'* The state of nature is seen as a con-

ition in which the will to fight others is known, fighting

not infrequent, and each individual perceives that his life

and well-being are in constant danger.” Accordingly, men in

the state of nature live without security, other than their

286

Part Four Specific Philosophy Writing Assignments

own strength; this is argued to be the natural condition

of mankind, and leads Hobbes to the conclusion that such ex-

istence is “natural” to man, but not rational [whereas soci-

ety is seen as rational, but not natural, contra

Aristotle] .’”

It is within this irrational condition of “war,* or

Hobbesian “fear- or “despair,” in which human beings find

little hope of attaining their ends without conflict, that

mortal men are compelled to elect a sovereign and move out

of the state of nature; only then can the imperative of

self-preservation be truly fulfilled through peace.** It is

important to note that the “state of nature," for Hobbes, is

a@ philosophic device employed as a means of hypothesizing

about human behavior in a pre-political and pre-social

state, i.e., a state without any external constraint on be-

havior. As Hobbes indicates, it is not necessary to presume

such a state actually existed, only that it captures essen-

tial features human beings would naturally exhibit.

Hobbes political philosophy was greeted in his own day

by nearly universal rejection, being more often renounced

than actually read. Hobbes was labeled an atheist, the “mon:

ster of Malmesbury,” a schemer, a heretic, and a

blasphemer.* His advocacy of an absolute monarch as the so-

lution to man’s inherent condition further distanced him

from the ‘enlightened’ mainstream of 17th century political

thought, including the philosophy of John Locke. It is a

commonly held view that although Locke makes no specific

mention of Hobbes in the Second Treatise, it may nonetheless

be interpreted as an attempt to systematically refute both

Choplor Fourteen History of Philosophy Papers 287

the notion of absolute monarchy and Hobbes’ description of

the state of nature.”

2. John Locke: Method and Problem

In the words of George Santayana, John Locke ‘at home

was the ancestor of that whole school of polite moderate

opinion, which can unite liberal Christianity with mechani

cal science and psychological idealism. He was invincibly

rooted in prudential morality, in a rationalized Protes-

tantism, in respect for liberty and law.**' Locke adopted

what he himself called a ‘plain, historical method,” fit, in

his own words, “to be brought into well-bred company and po-

lite conversation."*? (Not the personality to let truth be

an offending factor!)

Philosophy, Locke tells the reader in the introduction

of his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, is ‘nothing but

true knowledge of things." Properly, philosophy contains the

whole of knowledge, which Locke himself divides into three

parts: a physics or natural philosophy (the study of things

as they are), practice or moral philosophy, and logic, the

“doctrine of signs." The aim of the philosopher is to erect

as complete a system as he possibly can within these three

categories.”

Yet Locke persuasively argues in the Essay that

mankind's ability to gain true knowledge is significantly

limited, and set himself the task of determining the demar-

cations of human knowledge. To help mankind rid itself of

this “unfortunate” failing, he argues that man has been

blessed with capacities and talents sufficient to enable hin

&

|

|

288

a

Part Four Specific Philosophy Writing Assignments

to live a useful and profitable life. The Essay is severely

practical and utilitarian: we should concentrate on what we

can know, and not waste our energy or effort searching for

knowledge of things which lie beyond us.’ (For Locke, there

exists very little knowledge that is certain.)

It is exactly these practical and utilitarian ends that

motivated the construction of his moral and political phi-

losophy; although political and moral philosophy are not re-

ducible to metaphysical principles that apply outside of

their respective herds of inquiry, in all of his writings

Locke assumes, fundamentally, that man knows enough to live

a good and righteous life if he so chooses.

Locke‘s political philosophy is to be found in his Two

Treatises of Civil Government. Locke directs his writing

against two lines of absolutist argument: the First Treatise

was directed against the patriarchal theory of divine right

monarchy given by Sir Robert Filmer; the Second Treatise, as

previously indicated, against the line of argument for abso-

lutism presented in Hobbes’ Leviathan.*® My focus will con-

cern itself primarily with Locke’s Second Treatise

Locke argued that the state of nature was not identical

to the state of war, and that although it was “inconve-

nient," nature was governed by a natural law known by rea-

son, the “common rule and measure God has given mankind.*

Furthermore, the natural law “teaches all mankind who will

but consult it that, being all equal and independent, no one

ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or prop-

erty.°?* If the law of nature is observed, the state of na-

ture remains peaceful; conventional wisdom defines this con-

Chopter Fourteen History of Philosophy Papers 289

dition as one of mutual-love (via the "judicious Hooker),

from whence are “derived the great maxims of justice and

charity.*?”

Yet, according to Locke, God has instilled in natural

man “strong obligation of necessity, convenience, and incli-

nation to drive him into society**; hence, men quit their

natural power, resigned it up into the hands of the comnu-

nity’®? for the assurance that property, in the Lockean

sense, will be preserved, for that is the aim of all govern-

ment .?°

Men being, as has been said, by nature free, equal, and

independent, no one can be put out of this estate and sub- |

jected to the political power of another without his own

consent. The only way whereby any one divests himself of his

natural liberty and puts on the bonds of civil society is by

agreeing with other men to join and unite into a community 4

for their comfortable, safe, and peaceable living one $

amongst another, in a secure enjoyment of their properties

and a greater security against any that are not of it.’? (A

classic statement of libertarianism!) ;

An equally important factor motivating men to forfeit

the perfect freedom of the state of nature, is that within

this environment, each man has a right to interpret natural

law for himself, and to punish what he judges to be viola~

tions of it.*? Anyone who violates another‘s right to life,

liberty, or property, has placed himself in a state of war,

and the innocent party has the right to destroy those who

act against him because those that are waging war do not

live under the rule of reason, and, as a result, have no

290

rr

Part Four Specific Philosophy Writing Assignmonts

other rule but that of force and violence; furthermore,

this state of war would be perpetual if justice could not be

fairly administered.

Therefore, in order to avoid a state of war, Locke sug-

gests that one must forfeit the state of nature, creating an

environment where disputes can be decided upon by an impar-

tial authority.*® It would seem, at least upon prima facie

analysis, that although both thinkers utilize a “state of

nature’ device to demonstrate political necessity, their

similarities would end there. Hobbes’ state of nature would

seem to be populated by self-interested egoists whose per-

sonal gain is ultimately important; whereas, Locke appears

to suggest that a “civil” nature permeates pre-civil society

to such an event that man is voluntarily obliged to respect

his fellow human beings, and the formation of civil society

soon follows.

‘The common conception regarding the state of nature the-

ories of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke is thus presented. TI

shall now turn to the arguments as to why this conception is

invalid, beginning with a reassessment of Hobbes’ position,

followed by specific arguments regarding Locke’s notion of

pre-political man’s motivation to pursue civil ends.

3. Reassessing Hobbes

To understand morality and politics, Hobbes argues that

you

the

must understand man qua man: hence, psychology becomes

necessary foundation of moral and political science. and

the only way to view mankind in its most natural condition

is to assume a hypothetical state of nature in which men act

purely out of passion, void of reason (at least initially).

= ®

Chopler Fourteen History of Philosophy Popers 291

Hobbes’ account of the state of nature, as shown in Chapter

seventeen of Leviathan, was expressly designed to provide a

glimpse of man without the garb of convention, tradition, or

society, so as to uncover the underlying principles of the

mundane equity of natural man, without assuming an transcen-

dent purpose or will.”

Therefore, Hobbes’ prescription for stability was a de-

duction from the necessary behavior of man in a theoretical

society, not emphasizing how men ought to act, but rather

how they would act void of any relationships, whatsoever. It

is in this condition that our endeavors dispose us towards

pleasure or pain, man, being concerned with only those en- 4

deavors which serve to preserve himself, chooses those ob-

jects which meet this condition. Hence, man would find him- }

self often in competition with others for the same objects,

and a state of war would ensue, with each having the ‘right

to everything’ he wishes. (Keep in mind, the aim of Hobbes

is not to suggest that we can actually observe such a condi-

tion, or that it is even remotely possible; this is merely a

fundamental axiom in Hobbes’ thought experiment.) i

Historically, the negative interpretation of this condi-

tion of nature, being a “war of all against all,* has been

dominant in political and philosophical circles. Sterling

| Lamprecht defines the common conception of Hobbes’ descrip-

tive psychology as follows:

God made man such a beast and a rascal that he inclines

universally to malice and fraud. Man’s typical acts, un- 1

less he is restrained by force, are violent and ruthless, i

savagely disregarding the persons and property of his

292

a

Port Four Spoeific Philosophy Writing Assignments

fellows. His greatest longing is to preserve himself by

gaining power over others and exploiting others for his

own egoistic ends.”*

Lamprecht labels this view “Hobbism* and argues that in

this view of human nature, Hobbes is far from being a Hob-

bist. Hobbes gives, to be sure, a picture of man in the

state of nature which is far from flattering. But, Lamprecht

argues, Hobbes did not intend to say that his picture of man

in the state of nature is a complete account of human na-

ture. The concept of man in the state of nature enables us

to measure the extent to which reason and social pressures

qualify the expression of human passions. The idea of man in

the state of nature is for social science like that of nat-

ural body in physical science. Physical science holds that a

body continues in a state of rest or uniform motion in a

straight line unless influenced by outside forces. Actually,

there is no body which is not influenced by outside bodies;

but the idea of such a body enables us to measure the out-

side forces.”

Such a “natural man” would be observable whenever one

operates wholly under the dominion of passion, without the

“restraint,” or to use Hobbes’ language, “the opposing

force* of reason. Man, acting on his own, with no concern

for others’ self-preservation, guided by short-term consid-

erations only, is doomed to failure in a state of nature.

But if long-term moral, political, or social arrangements

enable them to maintain themselves without facing a war of

all against all, then the basic cause for hostility is re-

moved.*° In fact, the whole concern of Hobbes’ moral and po-

Chapter Fourteen History of Philosophy Papers 293

litical philosophy is to show men the way out of this short-

term condition of war and into a long-term condition of

peace. Whatever we may think of Hobbes’ theoretical view of

human nature, it must not be forgotten for a moment that its

object is not the repudiation of law and morality, but the

vindication of them as the only safeguards against general

anarchy and misery.!

David Gauthier, in his treatise entitled The Logic of

Leviathan, states this argument most eloquently:

In the beginning everyman has an unlimited right to do,

conceiving it to be for his preservation. But the exer-

cise of this unlimited right is one of the causes of the

war of all against all, which is inimical to preserva-

tion. Thus the unlimited right of nature proves contra-

dictory in its use; the man who exercises his right in

order to preserve himself contributes thereby to the war

of all against all, which tends to his own destruction.

And so it is necessary to give up some part of the unlin-

ited natural right.

The fundamental law of nature is

that every man ought to endeavor peace, as far as he has

hope of obtaining it. The law is the most general conclu-

Sion man derives from his experience of the war of all

against all. Clearly it depends on that experience,

Whether real or imagined. Although hypothetically a man

Might conclude that it was necessarily inimical to human

life, only an analysis of the human condition with all

Social bonds removed shows that peace is the primary req-

uisite for preservation."

294

Port Four Specilic Philosophy Writing Assignmants

The salvation of mankind, for Hobbes, depends on the

fact that though nature has placed him in an unpleasant con-

ition, it has also endowed him with the possibility to come

out of it, as revealed through the use of reason! It is not

merely the passion of fearing death, but the rational desire

to pursue those avenues ending in commodious living, in an

environment in which the hope of actually obtaining them is

real. Furthermore, reason suggests convenient articles of

peace, upon which men may be drawn to agreement and social

contract; to argue that the state of nature, for Hobbes, is

Gevoid of rationality or reason is to miss the point: it is

a necessary ingredient to lead man out of the state of na-

ture and into a civil society. Hobbes’ vision of nature

might be but a limited guide; his picture shows us an impor-

tant, but partial truth. It is a truth which we must en-

deavor to overcome--but we shall not overcome it if we mis-

understand it, deny it, or ignore it.

4. Locke and Political Motivation

What follows are several arguments which independently

suggest that the Lockean state of nature implicitly admits

of a Hobbesian condition of war, for Locke himself views

conflict as the primary motivating factor that necessarily

compels man to leave the state of nature, and enter civil

society. Initially, is important to establish a fundamental

point of difference between these two theories: Locke’s

‘state of nature’ was pre-political (i.e., prior to common

authority), whereas, for Hobbes, it was pre-social. Locke

refers to a situation in which a collection of men living

within a given region are not subject to political author-

ma

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Choplor Fourtoan History of Philosophy Popors 295

ity, not a situation in which there exists no form of rudi-

mentary organization, much less an organized society.‘

Hobbes uses the expression "state of nature” to denote a

situation in which men do not live in any form of eociety at

all, regardless of how fundamental. Furthermore, his defini-

tion tells us what people would be like if they could be di-

vested of all their learned responses or culturally induced

behavior patterns, especially those such as loyalty, patrio-

tism, religious fervor or class honor that frequently could

override the “fear” that Hobbes speaks of so dramatically in

pre-civil society.*

If we were to assume man as existing pre-socially, as

Hobbes does (a condition without trade, without the arts,

without knowledge, without any account of time, without so-

ciety itself), it seems a rather intuitive implication that

he might be motivated by only self-centered drives, for that

would be the extent of his learned behavior within this con-

dition. Locke, on the other hand, takes social and cultural

bonds for granted, and argues purely from a pre-political

position. Even a hypothetical Lockean might act a bit more

selfishly in a Hobbesian state of nature; once semantic dis-

crepancies are taken into account, these definitions already

begin to appear closer to agreement. **

Secondly, Locke’s position seems to be a normative pre-

scription, as opposed to a factual or theoretical descrip-

tion. For example: in Chapter 11, Section 6 of the Second

Treatise, Locke argues that through reason, those wha con-

sult the law of nature will learn that no one "ought" to

harm another's life, liberty or possessions. This phrasing

seems to suggest a normative position, prescribing how man

296

ee

Port Four Specllic Philosophy Wriling Assignments

should live in a state of nature, versus the descriptive ac-

count that Hobbes constructs upon his theoretical premises,

These positions are not mutually exclusive: one can still

observe pre-civil man in a Hebbesian state of nature, and

morally prescribe a Lockean state of nature as a more

vcivil’ alternative,

Thirdly, Locke seems to provide evidence for the Hobbe-

sian assumption that man often acts out of selfishness and

criminal intent.

Initially, Locke seems somewhat ambiguous about pre-

cisely what motivates the man of nature to move to civil so-

ciety: he states that God has instilled a “strong obligation

of necessity, convenience and inclination to drive him into

society." But why would man leave a state of nature that, at

least according to Locke, provides him the ultimate liberty

and power over his destiny, a condition that he likens to “a

state of peace, good-will, mutual assistance and preserva-

tion"?

If man in the state of nature be so free, as has been

said, if he be absolute lord of his own person and posses-

sions, equal to the greatest, and subject to nobody, why

will he part with his freedom, why will he give up his em-

ize and subject himself to the dominion and control of any

other power? To which it is obvious to answer that though in

the state of nature he has such a right, yet the enjoyment

of it is very uncertain and constantly exposed to the inva-

sion of others; for all being king as much as he, every man

his equal, and the greater part no strict observers of eq-

uity and justice, the enjoyment of property he has in this

state is very unsafe, very unsecure. This makes him willing

—— apa eGR

Chopter Fourloan History of Philosophy Papers 297

to quit a condition which, however free, is full of fear and

continual dangers.””

He continues: "Were it not for the corruption and vi-

ciousness of degenerate men, there would be no need of any

other [law], no necessity that men should separate from this

great and natural community."

If Locke’s state of nature is truly as “rational” and

“concerned” as he suggests, why is the only motivating fac-

tor powerful enough to move men out of this condition that

which he so vehemently denies exists: a Hobbesian condition

of “war”? Locke clearly states in the Second Treatise that

one of the natural rights that must be granted to all men in

the state of nature, equally, is that since there exists no

common judge to settle controversies between men, man should

interpret this natural law for himself and decide upon ap-

Propriate punishment for the offenders. This is a fundamen-

tal natural right for Locke, and it is precisely this intu-

itive and pre-political knowledge of the natural law that is

said to enlighten man to the burdens of civil society.

Yet Locke argues persuasively that any knowledge of a

natural law is more often than not hindered due to mankind’s

inherent epistemic limitations. Man’s own unquenchable and

boundless curiosity itself becomes a hindrance. Richard

Aaron uses the words of Locke’s Essay to demonstrate this

Point:

Thus men, extending their inquiries beyond their capaci-

ties and letting their thoughts wander into chese depths

where they can find no sure footing, ‘tis no wonder they

aise questions and multiply disputes, which never coming

298 Part Four Specific Philosophy Writing Assignments

to any clear resolution, are proper only to continue and

increase their doubts and to confirm then at last in per-

fect skepticism.”

Even if one accepted that a natural law existed, Locke's

clear rejection of man's ability to know this law with any

degree of certainty, combined with his suggestion that fore-

knowledge of such a law does not guarantee moral action,

would seem to suggest a condition of skepticism and dis-

agreement. (Note: this position is strikingly similar to

Hobbes’ argument that although human reason is capable of

discerning the laws of nature, mankind is unable to consis-

tently follow the dictates of such reason.*°) In fact, one

of the strongest arguments that Locke proposes to reject the

divine right theory of Sir Robert Filmer in the First Trea-

tise is based upon the notion that even if a right of suc-

cession had been determined by a law of nature, our knowl-

edge of natural law is limited to such a degree that there

remains no persuasive reason to accept one explanation over

another.

Furthermore, such subjective interpretations of the nat-

ural law would logically imply an unfairly administered and

inconsistent justice. Locke continues:

For every one in the state of nature being both judge and

t executioner, of the laws of nature, men being partial to

themselves, passion and revenge is very apt to carry them

too far with too much heat in their own cases, as well as

negligence and unconcernedness to make them remiss in

other men‘s.**

Chapler Fourteen History of Philosophy Papers 299

This seems contradictory to an environment of peace and

fellowship, and Locke strongly suggests that a state of war

would exist if justice could not be fairly administered.

Consider this: for Locke, in the absence of a neutral

judge, no one can accurately know truthfully whether his

cause is right or wrong. Thus, everyone is at liberty to be-

lieve himself right. Patrick Colby provides a case in point:

If one person fears his neighbor, whether with cause or

without (for only an individual can judge), by this par-

tial and subjective determination the neighbor becomes a

wild beast and is lawfully destroyed But when the neigh-

bor, now the target of attack, might understandably con-

clude that his assailant is the wild beast and so en-

deavor to execute the law of nature against hin.” '

But this means that Locke’s state of nature will not di-

vide neatly into groups of “upright law-abiders and selfish

malefactors.” And if a distinction cannot be made between

such individuals, it would seem impossible for justice to be

administered effectively. Locke provides such a conclusion:

“The inconveniences that they are therein exposed by the ir-

regular and uncertain exercise of the power every man has of

punishing the transgressions of others make them take sanc-

tuary under the law of government."®

Locke makes it clear from the beginning of his argument

and increasingly as he progresses that because judgment and

punishment are in the hands of every man, the state of na-

ture works very poorly.** And in the state of nature, con-

flict (or a willingness to contend by conflict), once begun,

and once unable to achieve a satisfactory resolution, would

Port Four Specific Philosophy Writing Assignmonts

tend to continue to a harsh ending, because there exists no

authority to subject both parties to the fair determination

of the law.**

This potential inconsistency in the application of nat-

ural law seems, for Locke, to create significant enough

hardships to motivate man to civil society:

easily grant that civil government is the proper remedy

for the inconveniences of the state of nature, which must

ceztainly be great where men may be judges in thief own

case; since it is easy to be imagined that he who was to

be unjust as to do his brother an injury will scarce be

so just as to condemn himself for it.**

Clearly, Locke’s state of nature, if not absolutely

equivalent to Hobbes’ state of nature, is at the very least

a place of extreme anxieties, inconveniences, inequality,

and fear of the potential outbreak of war. Locke provides

convincing evidence that the state of nature would be so

dangerous and unhappy, and the preservation of one’s right

to life so precarious, that the law of nature commands that

the state of nature be abandoned for civil society.*’ Though

Locke suggests that his state of nature is not a Hobbesian

condition of "war," a closer examination of this argument

would tend to suggest that without the failure of nature to

guarantee a secure peace, mankind would never voluntarily

choose to forfeit his absolute freedom. Jean Faurot provides

support :

But (Locke’s) state of nature also includes a condition

scarcely distinguishable from that which Hobbes describes

Chopter Fourteen History of Pl

sophy Popers 301

as a state of war--all that is needed is for some ran to

act contrary to reason, because in the state nature every

man is obligated to punish evildoers in this way, war be-

gins, with the right on the side of the innocent to de-

stroy the evildoer, or, if he prefers, to enslave hin.

Nor is there any end to this condition in the state of

nature, where every man is both judge and executioner.

‘The slightest disagreement is enough to set men fighting,

and the victory of the righteous is never secure. There-

fore, men have the strongest reasons for leaving the

state of nature and entering civil society.

Hence, not only do I argue that this state of nature

corresponds to Hobbes’ notion of a condition of perpetual

fear, or the “state of war,” but it actually becomes the

identical catalyst by which Lockean man justifies movement

to civil society.

Conclusion

The point of this presentation is clear: the common con-

ception of John Locke as the political propounder of the po-

lite school of positive, optimistic descriptive psychology

is an inaccurate characterization. Furthermore, the also-

common contrasting of Locke’s view of man in the state of

nature with Hobbes’ theoretical consideration of natural man

has traditionally been misunderstood. Hobbes did not concern

himself with a “plain, historical method,” or with impress-

ing “well-bred company” with “polite conversation.” His con-

cerns were with discovering the true nature of mankind so as

to devise a system of government (albeit monarchial) that

would best serve mankind's inherent drive for both self-

Preservation and peace.

302

Part Four Specific Philosophy Writing Assignments

Men enter civil society because the state of nature

tends to deteriorate into a condition of unrest and insecu-

rity if all men were rational and virtuous, apprehending and

obeying a natural law, there would be no problem. The pres-

ence of merely a few men acting in opposition to reason cre-

ates a condition of instability and provides the necessary

impetus for, in Locke’s words, “reasonable part of positive

agreement,’ a social contract.*”

Whether one accepts a reinterpretation of Hobbes’ theo-

retical state of nature construct, or a closer examination

of Locke's arguments, it is clear that, although not identi-

cal, their analyses offer many striking similarities. And,

more importantly, without the instability and fear in the

state of nature, neither philosopher could logically infer

movement from nature to civil society: it becomes the neces-

sary, perhaps sufficient cause for any social contract.

Therefore, the classical juxtaposition of Hobbes’ and

Locke’s “state of nature” theories is at best questionable,

and far from convincing.

Notes

1. G. W. F. Hegel, Hegel's Philosophy of Right, trans.

T. M. Knox (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1967), 2.

2. The use of terminology such as “man” or “mankind”

within the context of this paper is not intended to be

gender-specific (i.e, to exclude feminine denotations). Due

to the language of both Hobbes and Locke in their discussion

of political philosophy, I felt it best to likewise utilize

such wording.

Chapter Fourteen History of Philosophy Papers 303

3. Lewis P. Hinchman, “The Origin of Human Rights: A

Hegelian Perspective," Western Political Quarterly 37 (March

1984): 9.

4. John Locke, The Second Treatise of Government, ed.

Thomas P. Peardon (New Yor!

5. Ibid., 12.

Bobbs-Merill, 1952), XII.

6. A. E. Taylor, Thomas Hobbes (Port Washington, NY:

Kennikat Press, 1970), 6.

7. Ibid., 34.

8. Joseph Lasco and Leonard Williams, Political Theory:

Classic Writings, Contemporary Views (New York: St Martin’s,

1992), 230.

9. David P, Gauthier, The Logic of Leviathan (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1969), 6.

10. Ibid., 10.

11. Ibid., 7.

12. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, intro. Richard S. Peters

(New York: Macmillan, 1962), 100.

13. Ibid., 98.

14. Roman M. Lemos, Hobbes and Locke (Atlanta: Univ. of

Georgia Press, 1978), 73.

15. Hobbes, Leviathan, 100.

16. Ibid., 100.

17. Gregory S. Kavka, “Hobbes’ War Against All," Ethics

83 (1983): 292.

18. Lemos, 24.

19, Sterling P. Lamprecht, Introduction to De Cive, by

Thomas Hobbes (New York: Appleton-Century-krofts, 1949), xx.

20. Lemos, 74.

ee, mh —————

304 Part Four Spe Philosophy Writing Assignmonis

21. George Santayana, “Locke and the Frontiers of Common

Sense* in Some Turns of Thought in Modern Philosophy (New

York: Books for Libraries Press, 1933), 4.

22. Ibid.. 6.

23, Richard Aaron, John Locke (Oxford: Clarendon Press,

1967), 77.

24, Tbid., 77.

25. Though conventional wisdom validates this line of

reasoning, recent scholarship has brought forth historical,

biographical, and philosophic evidence to suggest that both

Treatises were written as a call to revolution prior to the

Glorious Revolution of 1688, and not as a response to

Hobbes’ philosophy. See Peter Laslett’s introduction to

Locke’s Two Treatises (Cambridge, 1967), and Ruth Grant's

John Locke's Liberalism (Chicago, 1987).

26. Locke, 4.

27. Ibid., 4.

28. Ibid., 44.

29. Ibid., 48.

30. Ibid., 53.

31. Ibid., 53.

32. Lemos, 85.

33. Locke, 11.

34. Ibid., 11.

35. Tbid., 13.

36. Ibid., 14.

37, Lasco and Williams, 252.

38. Lamprecht, xx.

39. Ibid., xi.

Chopler Fourteen History of Philosophy Papers 305

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

Gauthier, 18.

Ibid., 161; Taylor, 71.

Gauthier, 51.

Ibid., 52.

Lemos, 89.

Hinchman, 10.

A. John Simmons, “Locke’s State of Nature,” Politi-

cal Theory 17 (1989): 450.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

Locke, 71.

Ibid., 72.

Aaron, 77.

Lamprecht, 37.

Tbid., 71.

Patrick Colby, “The Law of Nature in Locke’s Second

Treatise,” Review of Politics 49 (Winter 1987): 3.

53.

54.

Locke, 71.

Robert Godwin, “Locke's State of Nature in Political

Societies,” Western Political Quarterly 29 (March 1976):

126,

55.

56.

Bs.

58.

Ibid., 127.

Locke, 9.

Lemos, 18.

Jean H, Faurot, Problems of Political Philosophy

(Scranton, PA: Chandler Publishing, 1970), 75.

59.

Ibid., 75.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5833)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Peran Niat Dalam Menjaga Semangat Belajar Siswa Kelas 6 Sdit Khalid Bin Walid Menurut Idealisme PlatoDocument27 pagesPeran Niat Dalam Menjaga Semangat Belajar Siswa Kelas 6 Sdit Khalid Bin Walid Menurut Idealisme PlatoSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Cover, DLLDocument11 pagesCover, DLLSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Sutanadamkusumatanaka 479030 ResumeDocument3 pagesSutanadamkusumatanaka 479030 ResumeSutan AdamNo ratings yet

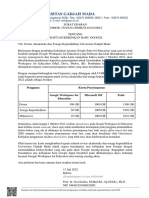

- Universitas Gadjah Mada Fakultas Filsafat Pengelola Mata Kuliah Wajib KurikulumDocument4 pagesUniversitas Gadjah Mada Fakultas Filsafat Pengelola Mata Kuliah Wajib KurikulumSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Kartu Ujian Akhir Semester Semester Genap 2021-2022Document1 pageKartu Ujian Akhir Semester Semester Genap 2021-2022Sutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Peran Niat Dalam Menjaga Semangat Belajar Menurut Idealisme PlatoDocument27 pagesPeran Niat Dalam Menjaga Semangat Belajar Menurut Idealisme PlatoSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- My CVDocument1 pageMy CVSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Screenshot 7Document1 pageScreenshot 7Sutan AdamNo ratings yet

- S1 2017 349520 TableofcontentDocument2 pagesS1 2017 349520 TableofcontentSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- 726-Article Text-2540-1-10-20220214Document11 pages726-Article Text-2540-1-10-20220214Sutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Bab IDocument32 pagesBab ISutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Ghandi: MahatmaDocument6 pagesGhandi: MahatmaSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Simple Red and Beige Vintage Illustration History Report PresentationDocument6 pagesSimple Red and Beige Vintage Illustration History Report PresentationSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Theallegoryofthecave FilingDocument17 pagesTheallegoryofthecave FilingSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Analisis Dampak Go-Jek Terhadap Pendapatan Tukang Becak Di Kota PadangsidimpuanDocument90 pagesAnalisis Dampak Go-Jek Terhadap Pendapatan Tukang Becak Di Kota PadangsidimpuanSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Surat GoogleDocument1 pageSurat GoogleSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- The Allegory of The CaveDocument17 pagesThe Allegory of The CaveSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- LPJ Departemen Sosial KemasyarakatanDocument44 pagesLPJ Departemen Sosial KemasyarakatanSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Bab Iii - 2Document10 pagesBab Iii - 2Sutan AdamNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument10 pages1 PBSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- 801-Article Text-3476-1-10-20210331Document8 pages801-Article Text-3476-1-10-20210331Sutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Kartu Ujian Tengah Semester Semester Gasal 2022-2023Document1 pageKartu Ujian Tengah Semester Semester Gasal 2022-2023Sutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Aliusman, Journal Manager, 04 Tantri WulandariDocument13 pagesAliusman, Journal Manager, 04 Tantri WulandariSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- FGD SlideDocument10 pagesFGD SlideSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Sutan AdamDocument8 pagesSutan AdamSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Keberadaan Tradisi Petung Weton Di Masyarakat Desa Grinting, Kecamatan Bulakamba, Kabupaten BrebesDocument54 pagesKeberadaan Tradisi Petung Weton Di Masyarakat Desa Grinting, Kecamatan Bulakamba, Kabupaten BrebesSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Universitas Gadjah Mada: Ujian Akhir SemesterDocument2 pagesUniversitas Gadjah Mada: Ujian Akhir SemesterSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Pentingnya Pendidikan Karakter Dalam Pembelajaran: AbstrakDocument10 pagesPentingnya Pendidikan Karakter Dalam Pembelajaran: AbstrakSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- Sutan Adam Kusuma Tanaka - Sosmas - Notula Riset - Wawancara Dengan Pengurus Tahun SebelumnyaDocument1 pageSutan Adam Kusuma Tanaka - Sosmas - Notula Riset - Wawancara Dengan Pengurus Tahun SebelumnyaSutan AdamNo ratings yet

- 8376-Article Text-28943-2-10-20220101Document10 pages8376-Article Text-28943-2-10-20220101Sutan AdamNo ratings yet