Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Koppes The Good Neighbor Policy and The Natonalization of Mexican Oil A Reinterpretation

Koppes The Good Neighbor Policy and The Natonalization of Mexican Oil A Reinterpretation

Uploaded by

pedroCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Test Bank For Microeconomics 10th EditionDocument4 pagesTest Bank For Microeconomics 10th EditionStan Mcclellan100% (34)

- Lummis Bill DraftDocument70 pagesLummis Bill DraftMike McSweeney100% (3)

- No Higher Law: American Foreign Policy and the Western Hemisphere since 1776From EverandNo Higher Law: American Foreign Policy and the Western Hemisphere since 1776No ratings yet

- Horn 1973Document19 pagesHorn 1973EfrainNo ratings yet

- Allied Policy Toward Germans, Italians and JapaneseDocument18 pagesAllied Policy Toward Germans, Italians and JapaneseXinJeisan100% (1)

- 世界政治动荡的年代:拉丁美洲对美国和西方霸权的挑战Document35 pages世界政治动荡的年代:拉丁美洲对美国和西方霸权的挑战ee SsNo ratings yet

- A Feast of Flowers: Race, Labor, and Postcolonial Capitalism in EcuadorFrom EverandA Feast of Flowers: Race, Labor, and Postcolonial Capitalism in EcuadorNo ratings yet

- Diplomacy and Capitalism: The Political Economy of U.S. Foreign RelationsFrom EverandDiplomacy and Capitalism: The Political Economy of U.S. Foreign RelationsNo ratings yet

- Chomsky Middle EastDocument19 pagesChomsky Middle Easthome143No ratings yet

- Brown OilCompaniesMexVenez1920s 1985Document25 pagesBrown OilCompaniesMexVenez1920s 1985Alexandra BejaranoNo ratings yet

- Nye (1988) Neorealism and NeoliberalismDocument18 pagesNye (1988) Neorealism and NeoliberalismVinícius JanickNo ratings yet

- Amerika NovijeDocument17 pagesAmerika Novijeradoslav micicNo ratings yet

- Middle East and The United StatesDocument26 pagesMiddle East and The United StatesniranjaneratNo ratings yet

- Oil, Banks, and Politics: The United States and Postrevolutionary Mexico, 1917–1924From EverandOil, Banks, and Politics: The United States and Postrevolutionary Mexico, 1917–1924No ratings yet

- OHMAN Statistical Turn in Early American POlitical EconomyDocument31 pagesOHMAN Statistical Turn in Early American POlitical EconomyFederico Ariel LópezNo ratings yet

- Hunting For History Unit ThreeDocument5 pagesHunting For History Unit ThreeBryan InganzoNo ratings yet

- Neorealism and NeoliberalismDocument18 pagesNeorealism and NeoliberalismFarjad TanveerNo ratings yet

- A Special Relationship America, Britain and The International Order Since The Second World War - DAVID REYNOLDSDocument21 pagesA Special Relationship America, Britain and The International Order Since The Second World War - DAVID REYNOLDSpietrod21100% (1)

- An Economic Interpretation of The American RevolutionDocument31 pagesAn Economic Interpretation of The American RevolutionShiva GuptaNo ratings yet

- Kissinger, Shultz 71 73Document28 pagesKissinger, Shultz 71 73Muhammad AliNo ratings yet

- Eichengreen 1996Document3 pagesEichengreen 1996geolabros100% (3)

- Hackett AgrarianReformsMexico 1926Document9 pagesHackett AgrarianReformsMexico 1926naomigouveiaNo ratings yet

- Wiley History: This Content Downloaded From 193.194.76.5 On Sun, 19 Mar 2017 22:45:14 UTCDocument3 pagesWiley History: This Content Downloaded From 193.194.76.5 On Sun, 19 Mar 2017 22:45:14 UTCandersphemNo ratings yet

- Amerika I Konfliktot - Teza AngliskiDocument133 pagesAmerika I Konfliktot - Teza AngliskiSlavica GadzovaNo ratings yet

- EL NINO Phenomenon by Latin American Countries (Communist Countries)Document31 pagesEL NINO Phenomenon by Latin American Countries (Communist Countries)cmeppieNo ratings yet

- America, Oil, and War in The Middle East: Toby Craig JonesDocument11 pagesAmerica, Oil, and War in The Middle East: Toby Craig JonesSohrabNo ratings yet

- Analyze The Responses of Franklin D Roosevelts Administration DBQ ThesisDocument4 pagesAnalyze The Responses of Franklin D Roosevelts Administration DBQ Thesisrebeccabordescambridge100% (2)

- Declaration of IndependenceDocument39 pagesDeclaration of IndependenceThủy LêNo ratings yet

- Colonialism and Hegemony in Latin America An IntroDocument13 pagesColonialism and Hegemony in Latin America An IntroGabriela RoaNo ratings yet

- LaFeber's "The New Empire" Book ReviewDocument5 pagesLaFeber's "The New Empire" Book ReviewGregg100% (1)

- Scaned AP US Free Response Questions BlackmonDocument35 pagesScaned AP US Free Response Questions BlackmonmrsaborgesNo ratings yet

- Ted Celis Period 2: Hapter HE Onservative Scendency UestionsDocument3 pagesTed Celis Period 2: Hapter HE Onservative Scendency UestionsTed EcilsNo ratings yet

- Eirv17n24-19900608 008-Rockefeller Kissinger Bush PushDocument2 pagesEirv17n24-19900608 008-Rockefeller Kissinger Bush PushLucas LopesNo ratings yet

- The Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications: ArticlesDocument12 pagesThe Monroe Doctrine: Meanings and Implications: ArticlesTreblif AdarojemNo ratings yet

- A Grave Offense of Significant Consequences''Document23 pagesA Grave Offense of Significant Consequences''serenity_802No ratings yet

- Ada522378 PDFDocument71 pagesAda522378 PDFcondorblack2001No ratings yet

- Diego Garcia Conference PaperDocument28 pagesDiego Garcia Conference PaperAmit SinghNo ratings yet

- Unit - Unit 05 - The Early Republic - 20210129115840Document7 pagesUnit - Unit 05 - The Early Republic - 20210129115840Matthea HessNo ratings yet

- Democracy Versus The National Security StateDocument32 pagesDemocracy Versus The National Security Stateferlo89901263No ratings yet

- Neorealism and Neoliberalism Nye IPTDocument18 pagesNeorealism and Neoliberalism Nye IPTElena SinelNo ratings yet

- Review For Test 3 Spring 2024Document4 pagesReview For Test 3 Spring 2024babyj.conlyNo ratings yet

- David S. Painter (2012), "Oil and The American Century", The Journal of American History, Vol. 99, No. 1, Pp. 24-39. DOI:10.1093/jahist/jas073.Document16 pagesDavid S. Painter (2012), "Oil and The American Century", The Journal of American History, Vol. 99, No. 1, Pp. 24-39. DOI:10.1093/jahist/jas073.Trep100% (1)

- The Rise of Conservativism Writing SampleDocument9 pagesThe Rise of Conservativism Writing SampleCharlotte ClarkeNo ratings yet

- US EMpire EssayDocument9 pagesUS EMpire EssayJamesNo ratings yet

- APUSH DBQ Doc AnalysisDocument5 pagesAPUSH DBQ Doc Analysisanirudhminecraft987No ratings yet

- The Marshall Plan Policy AnalysisDocument31 pagesThe Marshall Plan Policy AnalysisEddieTNo ratings yet

- Significant To Whom - GutierrezDocument22 pagesSignificant To Whom - GutierrezCarlos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Long-Prospectus Oct 29 2010Document17 pagesLong-Prospectus Oct 29 2010Tom LongNo ratings yet

- Chomsky - World Orders Old and NewDocument39 pagesChomsky - World Orders Old and NewDavid PrivadoNo ratings yet

- American History To 1865Document4 pagesAmerican History To 1865JeffersonNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez IntelectsConstiticion1824Document13 pagesRodriguez IntelectsConstiticion1824Ramiro JaimesNo ratings yet

- The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World OrderFrom EverandThe Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World OrderRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Culture and Economic BehaviorDocument19 pagesCulture and Economic BehaviorthoughtprojectilesNo ratings yet

- The Past, Present, and Future of Bankruptcy Law in AmericaDocument18 pagesThe Past, Present, and Future of Bankruptcy Law in AmericaRicharnellia-RichieRichBattiest-CollinsNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 USADocument13 pagesUnit 3 USAishikachauhan.bah.2023.ipcwNo ratings yet

- 14 The Resurrection and Death of The Cold War 1977 1988Document7 pages14 The Resurrection and Death of The Cold War 1977 1988lwwfdjgyrubbfyrlnvNo ratings yet

- Examination of The Nineteenth Century Inter-War YearsDocument4 pagesExamination of The Nineteenth Century Inter-War YearsDavid SpencerNo ratings yet

- Read - US Policy Towards The Islamic WorldDocument10 pagesRead - US Policy Towards The Islamic WorldAkh Bahrul Dzu HimmahNo ratings yet

- Cohen Caught in The MiddleDocument24 pagesCohen Caught in The MiddleGerardo MedranoNo ratings yet

- A - KennedyDocument19 pagesA - KennedyVanessa CianconiNo ratings yet

- Brittain (2005) A Theory of Accelerating Rural Violence Lauchlin Currie S Role in Underdeveloping ColombiaDocument27 pagesBrittain (2005) A Theory of Accelerating Rural Violence Lauchlin Currie S Role in Underdeveloping ColombiajavierdavidangelNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement Monroe DoctrineDocument4 pagesThesis Statement Monroe Doctrinerobynndixonevansville100% (2)

- GHGGVG Data UploadedDocument3 pagesGHGGVG Data Uploadedshriya shettiwarNo ratings yet

- Standard Operating Procedure For Media DestructionDocument3 pagesStandard Operating Procedure For Media DestructionMohsin AliNo ratings yet

- Eco261 Banking IndustryDocument25 pagesEco261 Banking IndustryAHMAD FILZA ADIRANo ratings yet

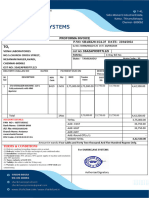

- Acct Statement - XX6782 - 23012024Document5 pagesAcct Statement - XX6782 - 23012024Thejesh tejuNo ratings yet

- Vdna LabDocument1 pageVdna Labnaveen kumarNo ratings yet

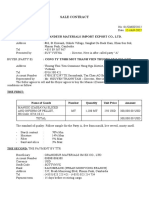

- Sale Contract:: Cong Ty TNHH Mot Thanh Vien Thuong Mai Gia LocDocument2 pagesSale Contract:: Cong Ty TNHH Mot Thanh Vien Thuong Mai Gia LocNiron CompanyNo ratings yet

- TableOfIncomeTaxable EPF SOCSO EISDocument7 pagesTableOfIncomeTaxable EPF SOCSO EISMohd ShamNo ratings yet

- The Vampire Economy - Doing Business Under FascismDocument288 pagesThe Vampire Economy - Doing Business Under FascismSouthern FuturistNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Tinjauan Keselamatan Perlintasan Sebidang Dampak Rencana Operasi Kereta Penumpang Di Lintas Padang-Pauh LimaDocument10 pagesJurnal Tinjauan Keselamatan Perlintasan Sebidang Dampak Rencana Operasi Kereta Penumpang Di Lintas Padang-Pauh Limahead unitNo ratings yet

- MDGQ CD3 WBFX Fs T16Document15 pagesMDGQ CD3 WBFX Fs T16Sukhdeo RathodNo ratings yet

- Essay On The Influence of Microfinance On The Business Development of Merchants in The San José International Market in The City of JuliacaDocument4 pagesEssay On The Influence of Microfinance On The Business Development of Merchants in The San José International Market in The City of JuliacaEvelyn CastilloNo ratings yet

- Circular No. 449 - Modified Guidelines On The Pag-IBIG Fund Calamity Loan ProgramDocument8 pagesCircular No. 449 - Modified Guidelines On The Pag-IBIG Fund Calamity Loan ProgramJaybie SabadoNo ratings yet

- Topic 1-Overview of Business To Business MarketingDocument11 pagesTopic 1-Overview of Business To Business MarketinggregNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - Global City, Demography and MigrationDocument8 pagesUnit 5 - Global City, Demography and MigrationNorlyn Esmatao BaladiaNo ratings yet

- Agri Business NKDocument34 pagesAgri Business NKKunal GuptaNo ratings yet

- SripurDocument8 pagesSripurSuresh ShNo ratings yet

- Coal Industry ResearchDocument14 pagesCoal Industry ResearchSURABHI SUSHREE NAYAKNo ratings yet

- New FGE Chapter I and IIDocument18 pagesNew FGE Chapter I and IImubarek kemalNo ratings yet

- Zimbabwe Banking Swift Codes: Here For AfricaDocument1 pageZimbabwe Banking Swift Codes: Here For AfricaTadiwanashe BurukaiNo ratings yet

- The Global Interstate System Pt. 3Document4 pagesThe Global Interstate System Pt. 3Mia AstilloNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument9 pages1 SMReuben RichardNo ratings yet

- BERDocument8 pagesBERacealloysllp.accNo ratings yet

- Wa0004.Document50 pagesWa0004.pradhanraja05679No ratings yet

- Week2 - AMORTIZATION, MORTGAGE, AND INTEREST (Modular)Document59 pagesWeek2 - AMORTIZATION, MORTGAGE, AND INTEREST (Modular)angel annNo ratings yet

- Summative-TestDocument2 pagesSummative-TestChristian DequilatoNo ratings yet

- 67597225eco 24 AlokDocument3 pages67597225eco 24 AlokAlok GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Charbel NahasDocument64 pagesCharbel NahasmoudshahineNo ratings yet

- Commodities ExchangeDocument59 pagesCommodities ExchangesherazhassannNo ratings yet

Koppes The Good Neighbor Policy and The Natonalization of Mexican Oil A Reinterpretation

Koppes The Good Neighbor Policy and The Natonalization of Mexican Oil A Reinterpretation

Uploaded by

pedroOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Koppes The Good Neighbor Policy and The Natonalization of Mexican Oil A Reinterpretation

Koppes The Good Neighbor Policy and The Natonalization of Mexican Oil A Reinterpretation

Uploaded by

pedroCopyright:

Available Formats

The Good Neighbor Policy and the Nationalization of Mexican Oil: A Reinterpretation

Author(s): Clayton R. Koppes

Source: The Journal of American History , Jun., 1982, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Jun., 1982), pp.

62-81

Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of Organization of American

Historians

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1887752

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Organization of American Historians and Oxford University Press are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of American History

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Good Neighbor Policy and the

Nationalization of Mexican Oil:

A Reinterpretation

Clayton R. Koppes

The Mexican government's nationalization of the foreign oil companies on

March 18, 1938, is a landmark in relations between the industrialized and the

developing countries. A turning point in Mexican economic development, the

nationalization became a model of economic self-determination for other

developing countries of whatever political systems. But the nationalization

posed a seminal challenge to the preferential economic and political position

of the United States and Great Britain in Latin America. For the first time a

country from the bloc that would become known as the Third World had

seized control of a basic sector of its economy held by the capitalist center.'

The policy adopted by the United States, which took the lead in the crisis,

has usually been viewed as the chief test of the Good Neighbor policy. A schol-

arly consensus has emerged which argues that, after three years of fruitless

support for the expropriated oil companies, the State Department broke with

those interests in 1941 and concluded an agreement with Mexico that settled

the issue on terms prejudicial to the firms. The immediate reason adduced for

the settlement was the United States's desire to improve relations with Mex-

ico in view of the Nazi threat to the hemisphere. But some historians have

Clayton R. Koppes is assistant professor of history at Oberlin College. He wishes to acknowl-

edge the financial support of Oberlin's Research and Development Committee and the Harry S.

Truman Library Institute.

I For the continuing vitality of the Mexican oil nationalization as a turning point for the Third

World, see Lorenzo Meyer, Mexico and the United States in the Oil Controversy, 1917-1942,

trans. Muriel Vasconcellos (Austin, Tex., 1977), 233; Pablo Gonzalez Casanova, "The Economic

Development of Mexico," Scientific American, 243 (Sept. 1980), 192; Paul E. Sigmund, Multina-

tionals in Latin America: The Politics of Nationalization (Madison, Wis., 1980), 48; Richard B.

Mancke, Mexican Oil and Natural Gas: Political, Strategic, and Economic Implications (New

York, 1979), 5; and Peter R. Odell, "Oil and State in Latin America," International Affairs, 40

(Oct. 1964), 659-73. The Mexican example probably played an important role in the creation of

the Brazilian anomaly-the formation of a state petroleum monopoly before oil had been

discovered. The Brazilian government of Getdlio Vargas, all too aware of the problems in imposing

regulation on prosperous private companies, set up the National Petroleum Council to control the

oil industry on April 29, 1938, six weeks after the Mexican nationalization. See Peter Seaborn

Smith, Oil and Politics in Modern Brazil (Toronto, 1976), 35.

62 The Journal of American History Vol. 69 No. 1 June 1982

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Good Neighbor Policy and Mexican Oil 63

argued that the rapprochement signifies a more fundamental shift away from

support for United States capital in Latin America. As Bryce Wood puts it: the

United States "curbed its finance capital"; support for private investment

abroad no longer ranked as a matter of "high national policy." The Mexican

oilcase thus represents the apogee of the Good Neighbor policy. 2

This consensus is open to question. Historians have stopped too soon. They

have assumed that the Cooke-Zevada commission agreement of 1942 marked a

settlement of the oil controversy, which had bedeviled relations between the

United States and Mexico since 1917. In this article I argue, however, that the

1942 agreement was but a tactical interruption in an essentially consistent

policy of support for United States oil firms in Mexico from 1901 through

1950. Despite some intragovernmental jockeying, Washington policy was

devoted to reversal of the nationalization. A reinterpretation of the oil dispute

therefore modifies the meaning of that masterpiece of protean political phrase-

making, the Good Neighbor.

The nationalization directly challenged the hoary United States petroleum

policy-the Open Door for oil. Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes struck

close to the mark when he noted tartly that Washington had "no international

oil policy . .. except to protect the interests of our nationals. " Since the turn of

the century the State Department had applied the principles of reciprocity and

2 Bryce Wood, The Making of the Good Neighbor Policy (New York, 1961), 344, 360. This stan-

dard work on the Good Neighbor policy, as well as the most recent book-length study, Irwin F.

Gellman, Good Neighbor Diplomacy: United States Policies in Latin America, 1933-1945

(Baltimore, 1979), are generally laudatory, although Irwin F. Gellman is more critical of the State

Department's actions in the Mexican nationalization crisis than is Bryce Wood. See ibid., 55-58.

Although both studies devote much attention to economic issues, they treat them primarily in the

context of particular United States property interests, not an overall economic system. See

Frederick C. Adams, Economic Diplomacy: The Export-Import Bank and American Foreign

Policy, 1934-1939 (Columbia, Mo., 1976), 224-25. Gellman and Wood write from a "security"

stance; they emphasize the nonintervention pledge of the Good Neighbor policy and hemispheric

solidarity during World War II. Writing from an "economic" stance may be more productive,

however, for understanding not only the Good Neighbor policy, but United States Latin American

policy in general. A study that does this, with a more critical stance towards Washington policy, is

David Green, The Containment of Latin America: A History of the Myths and Realities of the

Good Neighbor Policy (Chicago, 1971). His rather brief treatment of the Mexican oil nationaliza-

tion is somewhat surprising in view of the. subject's importance for hemispheric economic rela-

tions. Ibid., 36-39. Much useful light is shed on the Good Neighbor policy in E. David Cronon,

Josephus Daniels in Mexico (Madison, Wis., 1960). There are two major historical works devoted

to petroleum's role in United States-Mexican relations. Lorenzo Meyer is especially useful for his

Mexican perspective and emphasizes that country's ability to capitalize on United States preoccu-

pation with other considerations in two world wars to advance control of its oil resources. Meyer,

Mexico and the United States, 232-33. By essentially ending his study in 1942, Meyer overlooks

the subsequent United States efforts to reverse the nationalization. Indispensable for under-

standing the origins of the controversy is Robert Freeman Smith, The United States and Revolu-

tionary Nationalism in Mexico, 1916-1932 (Chicago, 1972). See also Robert Freeman Smith's

review of Meyer, Mexico and the United States, "Who's Afraid of SONJ? Energy and Nationalism

in International Relations," Reviews in American History, 6 (Sept. 1978), 394-99. Paul E. Sig-

mund's summary of the nationalization controversy is especially good on internal Mexican devel-

opments and the oil case's relationship to the larger issues of hemispheric economic policy. In the

end, however, he adopts the national security interpretation. Sigmund, Multinationals in Latin

America, 82-83. Of general works on foreign policy in the 1930s and 1940s, perhaps the most use-

ful for understanding United States relations with Latin America is Lloyd C. Gardner, Economic

Aspects of New Deal Diplomacy (Madison, Wis., 1964), 109-32, 194-216.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

64 The Journal of American History

the Open Door. American oil companies should be able to explore for and ex-

tract oil on a basis of equality with the firms of any nation. Materially aided by

this policy, United States firms from the 1920s into the 1950s staked out im-

portant interests in Latin America, the Netherlands East Indies, and especially

the Middle East. "It was," said Robert Stobaugh and Daniel Yergin, "one of

the most stunning examples of economic expansion in history.' '3

Penetration of Mexico led the way. The republic became, in the words of

Josephus Daniels, United States ambassador to Mexico from 1933 to 1941,

"the victim of exploitation by its own recreant officials and foreigners. Much

of its natural resources-the patrimony of its people-found their way into the

hands of foreigners, some by honest methods and some in ways that could not

stand the light. "4

Ameican and British companies began pumping in 1901. A pattern quickly

developed in which their short-term interests overrode Mexico's long-range

benefits. They pushed production to 193 million barrels annually by 1921, sec-

ond only to that of the United States. As production costs rose and the quantity

and quality of the resource declined in the 1930s, the companies shifted their

capital to the more profitable and politically congenial environment of Vene-

zuela. By 1937 Mexican production had sunk to sixth place internationally at

47 million barrels per year. Exploration by American firms had virtually

ceased, and surface installations were deteriorating markedly. In the classic

pattern of capitalist penetration of the Third World, the companies' operations

were integrated with those at home. From 80 to 90 percent of the petroleum

was exported during the boom years, and 60 to 70 percent during the 1930s; the

firms' lush profits were mostly repatriated; and the key positions in the com-

panies were staffed almost entirely by American and British nationals. By con-

trast Mexican workers were paid half the wages of, and received poorer hous-

ing than, the foreigners, even when they performed identical work. Interested

primarily in export, the companies made little attempt to meet Mexican

needs; the internal market in the late 1930s remained about the size of that of

Des Moines, Iowa. As Mexico's natural resources were drained away to the

developed world, little corresponding internal economic development took

place. 5

Resentment of foreign investment had helped fuel the Mexican revolution of

1910-1920, the first of the great twentieth-century social revolutions. At-

tempting to reassert control over the national patrimony, the constitutional

3Harold L. Ickes to Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dec. 8, 1941, "Oil 1941" folder, official file 56,

Franklin D. Roosevelt Papers (Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, N.Y.); Robert Stobaugh

and Daniel Yergin, eds., Energy Future: Report of the Energy Project at the Harvard Business

School (New York, 1979), 20. For an overview of United States international oil policy before

1941, see Michael B. Stoff, Oil, War, and American Security: The Search for a National Policy on

Foreign Oil, 1941-1947 (New Haven, 1980), 1-6.

4Josephus Daniels to Cordell Hull, Sept. 3, 1938, "Daniels" folder, President's Secretary's file,

Roosevelt Papers.

I Meyer, Mexico and the United States, 3-19; J. Richard Powell, The Mexicai2 Petroleum In-

dustry, 1938-1950 (Berkeley, Calif., 1956), 201-04; George W. Grayson, The Politics of Mexican

Oil (Pittsburgh, 1980), 14; Harold Young to Henry A. Wallace, Nov. 19, 1940, Henry A. Wallace

Papers (University of Iowa Library, Iowa City).

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Good Neighbor Policy and Mexican Oil 65

convention of 1917 adopted the famous Article 27, which reserved subsoil

rights to the state. Although incompatible with Anglo-Saxon legal concepts,

Article 27 drew on Mexico's twin heritage-Spanish law with its reservation of

mineral rights to the crown and the Indian tradition of communal property

ownership. Implementation of Article 27 was, however, another matter entire-

ly. The Mexican government found that any attempt to tighten controls met

with determined opposition from the oil companies. They received strong sup-

port from the State Department, even to the point of serious consideration be-

ing given to armed intervention on two occasions. The situation eased with an

agreement reached between President Plutarco Elias Calles and United States

Ambassador Dwight Morrow in 1928. But Mexico paid a high price. The aims

of the revolution were set aside as the firms retained virtually complete con-

trol of the resource. 6

But when Laizaro Cardenas became president in 1934, Mexico and the

United States started on a collision course over oil. The republic's most radical

president, Cardenas intended to fulfill the revolution through a quasi-socialist

program. He emphasized programs to improve the lot of the lower classes, es-

pecially the Indians, through education, redistribution of land, collective

farms (ejidos), curbs on foreign capital, and a larger role for state-run enter-

prise. He expropriated some land held by United States citizens and was

bogged down in a long controversy over compensation. In 1937 he completed

the nationalization of most of the railroads. (Since these decrepit lines had

teetered on the verge of bankruptcy for years, their owners greeted the expro-

priation with indifference or even the hope that they might finally be bailed

out.)7

But none of these actions had the explosiveness of the petroleum issue.

Cardenas reopened that question in 1935 by attempting to impose higher

taxes, insure more production, and attain higher wages and better conditions

for Mexican workers. Contending that the very principle of their continued

operation was at stake, the companies bitterly fought each aspect of

Cardenas's program. The climactic struggle occurred when the companies

defied an order handed down by an arbitration board in the wage dispute. In an

electrifying golpe, Cardenas nationalized the oil industry on the night of

March 18, 1938. For him, and for millions of jubilant Mexicans who celebrated

with a six-hour parade through Mexico City, the nationalization represented a

blow for economic self-determination that was just as vital as political inde-

pendence.8

6 Meyer, Mexico and the United States, 54-74, 133-37; Harlow S. Person, Mexican Oil: Symbol

of Recent Trends in International Relations (New York, 1942), 70-71; Smith, The United States

and Revolutionary Nationalism in Mexico, 256-59.

7 Meyer, Mexico and the United States, 170-7 1; Cronon, Josephus Daniels in Mexico, 122-29.

8 Meyer, Mexico and the United States, 149-72. Although the Mexican petroleum company El

Aguila, a part of the Royal Dutch Shell group, was the largest single interest expropriated, United

States firms took the lead in the crisis because of Washington's hemispheric dominance. Of these

firms Standard Oil of New Jersey (now Exxon) had the largest holdings-they accounted for more

than three-fourths of the eventual compensation agreement in 1942-and had the major voice in

the firms' negotiations. The Standard Oil of California group received about 15 percent of the total

compensation. The Consolidated Oil, Sabalo, and Seaboard groups divided the remainder. The

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

66 The Journal of American History

Significantly, the actions of the State Department before the nationalization

demonstrated that, despite the rhetoric of the Good Neighbor policy, defense

of private property interests abroad remained paramount. Access to Latin

American oil by United States firms was a given for the State Department.

Some things had changed, to be sure. Military intervention was remote. The

department had given up the brittle legalisms of the pre-Hoover period, and did

not involve itself in the negotiations between the firms and the Mexican

government, as it might have earlier. The diplomats tried nonetheless to

bolster the companies by establishing the boundaries of permissible discus-

sion. Secretary of State Cordell Hull disclaimed an intention to interfere in

Mexico's internal affairs, but he nevertheless insisted on measuring the rul-

ings of Mexican courts and administrative agencies with his yardstick of inter-

national law. (It was hard to imagine Hull impinging on the sovereignty of a

developed country in this way or a Western European country trying to block a

ruling by the National Labor Relations Board on such grounds.) Hull warned

the Mexicans against interfering with the Morrow-Calles agreement-which

was, of course, highly advantageous to the companies. During Mexico's finan-

cial crisis of 1937, the department tried to extract a settlement helpful to the

companies by imposing stiff terms on United States assistance; the Mexican

government protested the pressure tactics. In 1938 the firms appear to have

taken their defiant stance, rejecting a compromise offer their British counter-

parts wished to make, because they were confident of strong backing from

Washington. Indeed, the State Department appears to have contributed heav-

ily to the very outcome it wished to avoid-nationalization.9

The companies were not mistaken. They received strong governmental

backing, as they had before the nationalization. The leading interpreters of the

Good Neighbor policy-Hull and Sumner Welles-feared the consequences of

nationalization for United States capital abroad and tried to reverse Mexico's

action to the end of their terms. Since this interpretation runs counter to tradi-

tional accounts, a more detailed explanation is in order.

Understanding the oil controversy necessitates a conceptual shift. The issue

was not simply one of expropriation, as it is usually treated, but of nationaliza-

tion. This basic distinction made the petroleum issue different in kind from

the agricultural and railroad expropriations. First, the government took con-

trol of an entire sector of the economy; private capital was denied access to a

basic industry not normally considered a public utility. This separated it from

the agricultural expropriations, which affected only a portion of foreign-owned

land, a minuscule part of the national total, which the government intended to

redistribute to nongovernmental organizations. Second, the resource in ques-

Sinclair interests, the second largest group, reached a separate settlement in 1940. El Aguila

pumped about 60 percent of total production in Mexico at the time of expropriation, primarily

because it had brought in the rich Poza Rica field a few years ealier. El Aguila did not reach a com-

pensation settlement until 1948. Gulf Oil, which had good labor relations and small production in

Mexico, was not expropriated.

9 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1937 (5 vols., Washington, 1954), V, 657-58; Cronon,

Josephus Daniels in Mexico, 170-84.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Good Neighbor Policy and Mexican Oil 67

tion was an exportable commodity that was much in demand by developed

countries. This set it apart from the railroads, which had only internal

significance and which could be regarded as public utilities. Third, the state

petroleum monopoly, Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), would operate funda-

mentally as a socialized industry. While not oblivious of its balance sheet,

PEMEX would place social objectives before market considerations. One of its

major tasks was to stimulate national economic development. Its social goals

included such aspects as very low prices on lower-grade gasoline used by

poorer Mexicans, below-cost operations in isolated parts of the country, sub-

sidization of imports where its own production fell short, subsidized fuel

prices for nationalized transportation facilities, and a level of employment that

took account of social and political needs in addition to efficient production

standards. In short, the nationalization entailed Mexican control over a

resource; if private capital were allowed to participate at all, Mexico would set

the terms. 10

At bottom the oil controversy was an issue, not of ownership or expropria-

tion, but of the right to participation in a sector of the Mexican economy-in

other words, of nationalization. Had ownership been the question, it would

have been a simple matter to determine how much oil remained in the com-

panies' possession and compensate them for it. In effect this is what the

Cooke-Zevada commission did. But its decision could be only a partial settle-

ment, for it did not deal with the companies' future interest in the fields. " l

The companies were not primarily interested in compensation for their re-

maining assets. Since petroleum is a nonrenewable resource, its production is

a process of liquidation. The companies needed to reverse the nationalization

so that they could continue to explore and exploit the fields. As W. S. Farish,

Jersey Standard's president, said: "the right to extract oil is the very essence of

the value of an oil property. " Control of the resource was the whole point, for

the companies and for Mexico. Nationalization, by moving beyond the owner-

ship questions in expropriation cases, foreclosed future access to the resource

for private foreign capital. They particularly feared the precedent Mexico's ac-

tion might set for other Latin American countries. The companies did not in-

sist on ownership. They were willing to enter into other arrangements, such as

long-term operating contracts, so long as they retained access to the oil. 12

The Mexican nationalization posed a sharp and instructive contrast with the

United States. North of the border nationalization was shunned in favor of the

10 In using the term "socialized" I am adopting a more general meaning than the formal one of

control of the means of production by the workers. On the social objectives of Petr6leos Mex-

icanos (PEMEX), see Antonio J. Bermuidez, The Mexican National Petroleum Industry: A Case

Study in Nationalization (Stanford, Calif., 1963), 129, and Edward J. Williams, The Rebirth of the

Mexican Petroleum Industry: Developmental Directions and Policy Implications (Lexington,

Mass., 1979), 151-56. Meyer notes that the expropriation should really be considered a na-

tionalization but does not draw the resulting conceptual distinctions. See Meyer, Mexico and the

United States, 169.

" On the oil remaining that was available to the firms, see Morris Cooke to Sumner Welles,

May 13, 1942, file 812.6363/7704, Records of the Department of State, RG 59 (National Ar-

chives).

12 W. S. Farish to Hull, Oct. 8, 1941, file 812.6363/7353, Records of the Department of State.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

68 The Journal of American History

halfway house of the public-utility concept. Most monopolies and oligopolies

remained in private hands and were subject at most to government regulation,

which often served the industries' interests. Government operation was

limited mainly to "gas and water socialism" at the municipal and state level

and, chiefly since 1933, to federal generation and sometimes distribution of

electricity in a region. These "socialized" activities were usually established

through the construction of increased capacity, not through expropriation. To

take another example, the federal government relied on private enterprise for

development and exploitation of the public lands. Most of the continent, of

course, including mineral rights, had long since been conveyed into private

hands. When the federal government retained control of a resource, as in the

national forests or the public lands, it did not carry out production itself; in-

stead, for usually nominal fees, it allowed private enterprise to exploit the

resource for profit. Even in the case of the naval oil reserves at Elk Hills and

Teapot Dome, schemes for government production got nowhere. 13

If the issue is interpreted as one of control of the resource, it is clear that the

most influential foreign-policy makers supported the essentials of the oil com-

panies' position. United States officials could accept expropriation, though

with reluctance, but not nationalization. They conceived of expropriation as

analogous to eminent domain proceedings-a one-time condemnation of

private property for a narrowly defined public purpose. Franklin D. Roosevelt

drew the eminent domain and public utility strands together in 1939 when he

compared the Mexican action to "property taken by this Government for flood

control and power and navigation purposes during the past six years." These

actions, of course, did not entail state take-over of an entire area of economic

activity. 14

The mode of compensation was also critical. The State Department insisted

that payment had to be full and simultaneous with the taking; Roosevelt

softened that to "prompt."''5 The department also accepted uncritically the

firms' claim that their properties were worth $200 million-a figure Mexico

bitterly disputed. In any event, Mexico could not possibly raise that amount

instantly; it could finance the nationalization only through long-term opera-

tion of the industry. Had the United States been able to make these compensa-

tion demands stick, it would have effectively removed nationalization as an

instrument of Third World policy. By insisting on a narrow definition of

public purpose and on immediate compensation, Washington sought to limit

the nationalization to an expropriation.

From 1938 through October 1941 the State Department, which held the

reins of Mexican policy, supported the key points of the oil companies' posi-

13 On federal development of the public lands, see John Ise, The United States Oil Policy (New

Haven, 1926), 343-45; on the naval reserves issue, J. Leonard Bates, The Origins of Teapot Dome:

Progressives, Parties, and Petroleum, 1909-1921 (Urbana, Ill., 1963), 206-07, 221-22.

14 See draft of proposed letter in Welles to Roosevelt, Feb. 13, 1939, "Mexico" folder, official file

146, Roosevelt Papers; Roosevelt's changes in his own hand, in Roosevelt to Daniels, Feb. 15,

1939, ibid.; George Messersmith memoirs, part 17, Special Collections (University of Delaware

Library, Newark).

15 Welles to Roosevelt, Feb. 13, 1939, Roosevelt Papers; Roosevelt to Daniels, Feb. 15, 1939,

ibid.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Good Neighbor Policy and Mexican Oil 69

tion. During the first phase of the crisis, from March 1938 through year's end,

the department tried to nullify the expropriation. Secretary of State Hull, who

privately referred to the Cairdenistas as "those Communists," took a strict

legalist position. Law tends to reflect power relationships as much as abstract

principles of justice, and international law thus in large measure served the

desires of the advanced capitalist countries, to the disadvantage of the Third

World. Hull started from the premise that Mexico did not intend to make

"reasonable payment." Cardenas, however, had repeatedly pledged to com-

pensate the companies, although not immediately and not in the amount the

United States demanded. Undeterred, Hull went on to charge that Mexico

would "inevitably" seize all foreign-owned property. "In eight cases out of

ten," he continued, the country that confiscated property became "a decadent

nation soon thereafter and in its most vital processes of progress and civiliza-

tion ... steadily moved backward and downward. "' 16

These arguments, so reminiscent of turn-of-the-century imperial rhetoric,

were not just the limited images of a hill-country judge. They probably enjoyed

a congenial response among most Foreign Service officers, who were largely

Republican and opposed the New Deal and the Good Neighbor policy, to say

nothing of nationalization. The sophisticated under secretary of state, Welles,

echoed them. He underscored Hull's point that Mexico would not get the

private foreign capital it needed. Welles scolded the Mexican ambassador

sharply: the nationalization was "absolutely suicidal"; only someone in a

"lunatic asylum" would invest in Mexico. Since the country could not make

full and immediate compensation, they argued, the nationalization must be

revoked. 17

The department backed its protests with economic and diplomatic pressure.

Ambassador Daniels feared the department intended to create such financial

stress that Cardenas would be driven from power and his successor would

reinstate the firms. The most serious strain came from the department's co-

operation with the oil companies' boycott of PEMEX exports. In the first year

of nationalized operations, the amount of Mexican oil sold abroad dropped by

more than 50 percent; sales to the United States fell by 61 percent; to Latin

America, by 75 percent. In desperation Mexico signed sale and barter deals

with Germany, Italy, and Japan-an arrangement that neither reflected credit

on Mexico, which had been staunchly antifascist, nor served the interests of

the United States. (The German and Italian deals lapsed after the outbreak of

war. Mexico suspended the Japanese business in August 1940, almost a year

before the United States got around to its own embargo of oil to the empire.)

The State Department redlined Mexican loan applications until 1941; it dis-

couraged most private lenders, although a few, mostly armaments dealers,

received its blessing. The diplomats also attempted to curtail United States

purchases of Mexican silver. This tactic was thwarted, however, by Secretary

16 Foreign Relations of the United States: 1938 (5 vols., Washington, 1954-1956), V, 741-43;

Wood, Making of the Good Neighbor Policy, 217.

17 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1938, V, 731, 738. On the Foreign Service, see

Gellman, Good Neighbor Diplomacy, 71, 72, and Cronon, Josephus Daniels in Mexico, 64-65.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

70 The Journal of American History

of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau and his aide Harry Dexter White, who

believed that a sound Mexican economy benefited the United States. 18

Washington's actions have been contrasted with the cruder methods of

earlier administrations. Wood has termed the tactics "pacific protection. " To

be sure, the United States apparently did not seriously entertain military inter-

vention and did not use all the nonmilitary means at its disposal. Washington

policy makers felt constrained by the recognition that stronger action would

produce economic chaos and political instability in Mexico that would harm

United States interests at a critical time. But the most important point is that

the United States had not accepted Mexico's assertion that the oil nationaliza-

tion was an internal Mexican matter. If policy is measured not by its forms but

by its intended results, United States policy in the oil crisis involved substan-

tial interference in Mexico's internal affairs. '9

Indeed, the crisis was serious enough to carry the two countries to the brink

of diplomatic rupture in late March 1938. A severance of relations was averted

only by Daniels's extraordinary insubordination. The seventy-year-old Raleigh

newspaper publisher seemed an anachronistic choice when Roosevelt ap-

pointed him ambassador in 1933. Daniels had been secretary of the navy when

the marines landed at Veracruz in 1914; he spoke no Spanish; his Bryanesque

morality banned alcoholic beverages at the embassy. And yet this self-styled

"shirt-sleeve diplomat" mixed easily with all classes of Mexicans, displayed

an instinctive hill-country sympathy for the downtrodden masses, and came to

defend Cardenas's radical social program as a part of a transnational struggle

between "privilege" and "democracy. " Daniels was "universally loved," said

Vice-President Henry A. Wallace after a visit in 1941, and he advised Roosevelt

to be sure the next ambassador was equally simpadtico. Daniels sympathized

with the Mexicans' "super nationalism." They did not want "Uncle Sam,

John Bull, Hitler, Stalin, or anybody, good or bad," meddling in their internal

affairs. The United States should practice "Patience and the policy of Put-

Yourself-in-His-Place. "a20

With his empathy for the Mexicans, Daniels realized that Hull's sharp note

of March 26, 1938, which seemed to impugn Cardenas's promise of compensa-

tion, threatened to wreck diplomatic relations. The ambassador then took the

extraordinary liberty of suggesting to the Mexicans that the note might be con-

sidered as "not received," even though they already had it in their possession.

Daniels did not ask Hull's permission nor did he inform the secretary until

several months later. The ambassador dared take such a step only because of

his personal relationship with Roosevelt. The young Roosevelt had been his

assistant secretary of the navy, and in the 1930s Daniels still addressed him as

"Dear Franklin" while the president reciprocated with "Dear Chief." In 1938

18 Wood, Making of the Good Neighbor Policy, 224-33; Meyer, Mexico and the United States,

201-04, 207-13; Powell, Mexican Petroleum Industry, 112-15; Ruth Sheldon, "Marketing

Harasses Mexican Oil Industry Officials," Oil and Gas Journal, 38 (June 1, 1939), 18.

19 Wood, Making of the Good Neighbor Policy, 343-48.

20 Daniels to Hull, July 5, 1940, "Mexico" folder, official file 146, Roosevelt Papers; Wallace to

Roosevelt, Jan. 9, 1941, ibid. See also Cronon, Josephus Daniels in Mexico; and Josephus Daniels,

Shirt-Sleeve Diplomat (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1947).

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Good Neighbor Policy and Mexican Oil 71

relations with Mexico hung by the thread of a unique presidential-ambassador-

ial connection which defied the canons of sound institutional practice. With-

out the Roosevelt-Daniels tie, diplomatic relations might well have been

severed, with incalculable consequences.21

The president kept his distance during the early phase of the oil crisis. He

ruled out military intervention over the nationalization. In his first public

statement on compensation he disputed the companies' argument that they

should be reimbursed for prospective profits. Roosevelt was engaged in a

ticklish balancing act. On the one hand, he wanted to insure United States ac-

cess to Mexican oil and to uphold the companies, if possible. On the other, he

sought to keep Mexico friendly. For the most part he waited to see what results

the State Department's hard line would produce. By the end of 1938 the pic-

ture was coming into focus. Despite the short-term economic dislocation

caused by the nationalization and the boycott, Mexico would not recede from

the expropriation.22

Faced with this stalemate, the firms and the government tried a new strat-

egem in the second phase of the crisis, from late 1938 through January 1940.

Roosevelt, Hull, and Welles enthusiastically backed the new proposal by the

companies' attorney, Donald Richberg, former Bull Mooser and early New Deal

official. Richberg suggested that Mexico allow the companies to return with a

fifty-year operating contract, a virtually free hand in managerial decisions, and

only a small cut of the profits for the Mexican government. The Richberg pro-

posal was very significant, for it indicated that the companies might surrender

formal ownership in return for a secure long-term operating contract, which

guaranteed continued access to the resource. But the idea stood no chance of

acceptance. Mexican opinion denounced the notion as a transparent device to

return control to the companies; Cardenas insisted on Mexican control. When

Richberg's negotiations collapsed, Washington proposed arbitration. Mexico

rejected that mechanism, however, on the grounds that the nationalization

was a domestic matter. In short, whatever the tactical differences between the

oilmen and the government officials, they stood shoulder to shoulder on the

fundamental issue of control.23

The resulting stalemate was not broken until the fall of 1941, when the

government's position temporarily diverged from that of the companies. Over

the firms' objections, the State Department reached an accord with Mexico on

November 18, 1941, to set up the Cooke-Zevada commission to evaluate the

properties and reach a compensation figure. Morris L. Cooke, a distinguished

liberal engineer who ran the Rural Electrification Administration from 1935 to

1937, headed the United States section and engineer Manuel J. Zevada the

Mexican contingent. In June 1942 they brought in a recommendation that

Mexico pay the companies $23,995,991 plus slightly more than $5 million in-

terest over four years. The compensation figure was adequate, even generous.

Cooke estimated that the companies had already recovered 90 percent of the

21 Cronon, Josephus Daniels in Mexico, 195-219.

22 Meyer, Mexico and the United States, 187; Cronon, Josephus Daniels in Mexico, 201.

- 23 Roosevelt to Daniels, Feb. 15, 1939, "Mexico" folder, official file 146, Roosevelt Papers;

Cronon, Josephus Daniels in Mexico, 238-46; Gellman, Good Neighbor Diplomacy, 53.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

72 The Journal of American History

oil available to them. In the areas where development had been pursued, the

fields were all but depleted. Under standard accounting practices, only 10 per-

cent, or $20 million, of the alleged investment of $200 million remained to be

written off. With allowance for intangible factors also included, the commis-

sion actually went beyond what would have been acceptable in a strict ac-

counting. In that sense the companies did not suffer any actual property loss.24

What the firms feared losing most, however, were their prospective profits

from long-term access to Mexican oil. They therefore remained adamant and

did not accept the settlement until October 1, 1943. To a large extent the com-

panies were hoist by their own petard. By failing to develop their concessions,

they forfeited a tangible present claim. The firms and the State Department

thus parted company not over present property interests but over the best way

to protect future access.

Historians have attempted to explain the divergence between the oilmen

and the diplomats-the chief interpretative problem for the Good Neighbor

policy and Mexican oil-as a result of the changing security situation. This

analysis has problems even on its own terms, however. Policy makers, par-

ticularly Welles, have been praised for realizing that "narrow property in-

terests" should yield to high national policy. It should be noted, however, that

their conversion came rather late in the day-the German army straddled

Europe from Brittany to Stalingrad, and a crisis loomed in the Pacific. They

also faced substantial pressure from within the national security establish-

ment. Hemispheric solidarity was a cornerstone of Roosevelt's global strategy.

The military, supported by the president, was seeking air and naval bases in

Mexico, but little progress could occur until the oil logjam was broken. Eager

for Mexican friendship, Roosevelt dispatched Vice-President-elect Wallace to

Mexico City for the inauguration of the new president, Avila Camacho, in late

1940. During this unprecedented visit Wallace, at Roosevelt's suggestion, laid

a wreath on the monument to the young cadets who died defending Mexico

City against United States troops in 1847. Wallace reported that settlement of

all the outstanding issues between the two countries was possible with

24 Cronon, Josephus Daniels in Mexico, 268-70. Harlow Person, who was one of C

assistants, explained the work of the commission as follows. The experts apparently agreed that

Mexican law governed subsoil rights and that "indemnification cannot be claimed for loss of ex-

clusive opportunity to capture them at some future time." Person, Mexican Oil, 73. However,

token payments were made to "reflect some of the imponderables involved. " The settlement thus

consisted of: (1) conventional valuation of depreciated surface properties; (2) value of oil in tanks

and pipe lines at the time of expropriation; (3) value of oil "in process of capture, i.e., oil within

immediate reach of a live well or within an area delimited by a group of live wells," the oil being

"partially captured by the positive act of construction of the wells"; (4) a component for "good

will" or "going concern value," or, oil present in certain localities where drilling was underway;

(5) "an additional token item" for oil in areas only partially proved; and (6) a segment for capital

outlays in areas that were not yet exploited. Cooke made the significant observation that at least

90 percent of the oil "originally available to the American companies" had already been recovered

by March 18, 1938. "Following the universal practice of well-managed oil companies, by 1938 that

investment [the firms' alleged $200 millioni, should have been written off in proportion to the

depletion of the oil reserves for which the investments were originally made." Therefore, except

for highly speculative, unproved wildcat areas, the firms' values "could neither logically or fairly

be in excess of 10% of the maximum claimed investment or $20,000,000." Cooke to Welles, May

13, 1942, file 812.6363/7704, Records of the Department of State.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Good Neighbor Policy and Mexican Oil 73

Camacho, a more conservative figure than Cardenas. Faced with the

deteriorating security situation and these cues from the president, it would

have been irresponsible for the State Department to persist in backing private

interests in contravention of larger foreign policy. What appears remarkable is

not that Welles and his colleagues modified their support of the companies,

but that they stalled until the fall of 1941.25

But the oil controversy itself and the nature of the agreement reached in

1941-1942 provided the most important evidence. Historians have interpreted

the split between the department and the oilmen as an example of the govern-

ment curbing finance capital, accepting the nationalization, and winning a

happy resolution of the petroleum controversy. This may be doubted. Histori-

ans have magnified the divisions between the parties, and in so doing miscon-

strued the nature of the Cooke-Zevada settlement.

In the first place, the department had grown uneasy about the firms' claims.

Their united front had been breached in 1940 when the Sinclair Oil Company,

realizing that Mexico would not return the properties, concluded a separate

deal. Represented by Patrick Hurley, Herbert Hoover's secretary of war,

Sinclair accepted compensation of $14 million in cash and oil-one third the

$42 million it had claimed. The Sinclair deal demonstrated both that Mexico

was sincere about compensation and that the firms' valuation was probably

grossly inflated. Then a report done by the Geological Survey at the State

Department's request placed the value of the assets of the remaining firms at

about $10 million-not far from the Mexican estimate. State Department of-

ficials were shocked. Although the survey's report had its flaws, it turned out

to be much closer to the eventual settlement reached by the Cooke-Zevada

commission than the astronomical claims the diplomats had accepted on

faith. Everett DeGolyer, who was perhaps the most eminent petroleum geol-

ogist in the world, reinforced skepticism concerning the companies when he

told the State Department that Jersey Standard's holdings were worth at most

$20 million and possibly much less.26

More importantly, the department's willingness to settle the valuation, or

expropriation, question did not signify an acceptance of the nationalization.

Welles and his colleagues had not given up their goal of reinstatement of the

companies. But after three years of frustration and bitterness, it appeared that

nothing short of military intervention, which was unthinkable, would ac-

complish their aim. They then began to hope that the compensation and na-

tionalization issues might be separable. They could not be certain that agree-

ment on compensation would induce Mexico to allow United States firms

back in. But they knew that a return was impossible until the valuation ques-

tion was laid to rest. Accordingly, the Cooke-Zevada agreement was limited to

settlement of the expropriation question. Nothing was said about the con-

25 Wood, Making of the Good Neighbor Policy, 332, 344-45; Cronon, Josephus Daniels in M

ico, 257-58; Wallace to Roosevelt, Jan. 9, 1941, "Mexico" folder, official file 146, Roosevelt

Papers.

26 Russell D. Buhite, Patrick j. Hurley and American Foreign Policy (Ithaca, N.Y., 1973), 82-99;

Geological Survey report [n.d.i, file 812.6363/7301-1/2, Records of the Department of State;

Everett DeGolyer to Hull, Aug. 14, 1941, file 812.6363/7534-5/1 1, ibid.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

74 The Journal of American History

tinuation of nationalized operations or of the companies' reentry. In other

words, not only for security reasons but because of the failure of tactics in the

petroleum negotiations, the State Department decided on a partial agreement

that left the basic issue for later resolution.27

An important clue to United States tactics surfaced during a discussion be-

tween Welles and the British ambassador, Viscount Halifax, in October 1942.

If the firms accepted the Cooke-Zevada agreement, the under secretary said, "I

believed that ways and means would be found whereby the companies might

continue activities in Mexico. " Welles elaborated on the relationship between

the compensation agreement and what he termed "the more basic question of

the terms and conditions under which United States interests would be per-

mitted to participate" in Mexico. Reentry had been "totally impossible" so

long as the expropriation issue remained open. However, "just as soon as I

thought there was the slightest hope of the Mexican Government's being will-

ing to discuss this thorny matter, Ambassador Messersmith [Daniels's suc-

cessor] was instructed to take it up with the Mexican Government.... I have

instructed Mr. Messersmith that above all other duties he should give first

place to endeavoring to work out a plan satisfactory to all under which United

States interests could again participate in the Mexican oil industry." Welles

cautioned against pressuring Mexico City before "it can control its own public

opinion," for that could result in the exclusion of United States firms "for

many years to come when such participation will be more than ever necessary

for our own national interest." In short, Welles and his colleagues, having

cleaned up the expropriation tangle, could now go on with the more essential

business: the reversal of the nationalization to insure private access to Mex-

ican petroleum in the presumed national interest of the United States.28

The instructions spelled out a plan to employ United States government

financial power to bring about the companies' access to Mexican oil for export

purposes. "The interests of this nation in petroleum supply are closely and in-

herently linked with those of Mexico," they said. Nothing except the war

should "interfere with the sound and orderly reestablishment of the oil in-

dustry in Mexico. " A major goal was to develop "the full export possibilities of

the industry," in other words, to insure United States access to Mexican oil.

The instructions disclaimed an intention to dictate Mexico's internal policies.

But they added pointedly: "When this Government is called upon to consider

questions involving financial or other substantial assistance . . . it must be in

[a] position to judge the long range consequences of its own actions." In other

words, if a loan would solidify the nationalization, to the detriment of United

States capitalists, the department probably would disapprove. Lest there be

any doubt about the meaning of this language, Max Thornburg, the depazt-

27 Meyer's contention that by mid-1941 the United States had accepted the idea that the com

panies would not return lacks substantiation at the time and in view of later developments.

Meyer, Mexico and the United States, 222.

28 Welles memorandum of conversation with Viscount Halifax, Oct. 2, 1942, file

812.6363/7767, Records of the Department of State; Welles to Roosevelt, Feb. 17, 1943, Confiden-

tial file 12, "Petroleum Coordinator" folder, President's Secretary's file, Roosevelt Papers. See also

Philip Bonsal to George Messersmith, Nov. 24, 1942, file 812.6363/7814, Records of the Depart-

ment of State.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Good Neighbor Policy and Mexican Oil 75

ment's petroleum advisor, explained in an internal memorandum: "What ... I

meant, was that until we know whether or not Mexico would permit Amer-

ican participation in some way, we were not ready to say how much help we

would be willing to give Mexico. "129

The negotiations were entrusted to the new ambassador to Mexico City,

George Messersmith. A carnation in the lapel of his elegantly tailored suit, the

punctilious Messersmith was virtually Daniels's opposite. An erstwhile high

school civics teacher and principal, Messersmith had married well and then

entered the consular and diplomatic service. He served as assistant secretary of

state for administration from 1937 to 1940, becoming a confidant of Hull, and

then went to Cuba as ambassador from 1940 to 1942. Where Daniels mixed

with a cross section of Mexicans, Messersmith socialized almost solely with

conservative members of the upper class. Messersmith believed the answer to

Mexico's economic woes lay in replication of a conservative version of north-

of-the-border capitalism. "We are still attached to private enterprise in the

United States," he said, "for without it we would be lost." The ambassador's

rambling dispatches-which won him the derisive nickname "Forty Page

George" among some State Department hands-preached the incompetence of

PEMEX to eager ears in Washington. Officials less sanguine about the oil com-

panies despaired when they dealt with Messersmith. Ickes described the am-

bassador as "slow and ponderous and repetitious and about as animated" as

the cigar-store wooden Indian. (Messersmith retaliated with equally disparag-

ing opinions about the "old curmudgeon's" psychological makeup in his un-

published memoirs.) In Messersmith the State Department enjoyed an am-

bassador who would eagerly carry out its policies.30

The ink was scarcely dry on the Cooke-Zevada agreement when the State

Department judged the time "singularly propitious" for Messersmith to begin

29 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1942 (7 vols., Washington, 1960-1963), VI, 528-33;

Max Thornburg to Laurence Duggan, Nov. 17, 1942, file 812.6363/7800, Records of the Depart-

ment of State. These were not the only ideas Thornburg had in mind. He thought the expropriated

companies should have preference over other United States companies if a return to Mexico took

place. He also concocted a plan by which the companies might return as "ostensibly Mexican"

firms in other than "popularly recognizable form." When Harold L. Ickes got hold of Thornburg's

plan, he forwarded it to Roosevelt with the suggestion that it be titled "An Indiscreet Memoran-

dum from the State Department." The president passed the document on to Welles with the note

that "I know you will recognize that there is much suspicion that he is representing the oil people

as well as the State Department!" Roosevelt added cheerfully: "I send this merely to keep you up-

to-date!" Thornburg's superiors eventually concluded that he had tangled allegiances between

Jersey Standard and the department, and they let him go. But he had already played a key role in

the formulation of the American drive for oil abroad. In the best tradition of the Open Door policy,

the problem Thornburg's actions posed for the State Department was not that he represented oil

companies but that he favored one firm over others. See Ickes to Roosevelt, April 20, 1943,

"Ickes" folder, box 75, President's'Secretary's file, Roosevelt Papers; Roosevelt to Welles, June 30,

1943, enclosing Thornburg to Welles, Feb. 8, 1943, "State Dept." folder, ibid. See also Stoff, Oil,

War, and American Security, 65; and Irvine H. Anderson, Aramco, the United States and Saudi

Arabia: A Study of the Dynamics of Foreign Oil Policy, 1933-1950 (Princeton, N.J., 1981), 44.

30 Messersmith to Hull, July 24, 1944, "Mexico" folder, box 18, Petroleum Divison, Records of

the Department of State; Ickes manuscript diary, Jan. 23, 1944, p. 8574, Harold L. Ickes Papers

(Manuscript Division, Library of Congress); Spruille Braden, Diplomats and Demagogues: The

Memoirs of Spruille Braden (New Rochelle, N.Y., 1971), 370; "Career Man's Mission," Time, 48

(Dec. 2, 1946), 22-24.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

76 The Journal of American History

exploratory talks with the Mexican government about the return of foreign

petroleum private enterprise. The department plan suggested that PEMEX

should sign contracts with United States firms to carry out exploration and

development over a period of perhaps thirty years. During that time the com-

panies would recoup their expenses through the oil produced; thereafter the

companies and PEMEX would divide the oil according to an agreed-upon for-

mula. Messersmith believed that Camacho was about to accept the proposal in

mid-1943, only to pull back under pressure from CQrdenas. The Cairdenistas

were opposed, to be sure, but it seems unlikely that an agreement was immi-

nent. Washington's proposal severely compromised the nationalization, as it

was designed to do. Hindered by his ideological blinkers, Messersmith con-

sistently overestimated Mexican desire for foreign private capital. A proposal,

such as the State Department's, that so compromised the nationalization

would have called into question the very foundation of the Mexican revolu-

tionary tradition.3'

President Camacho did not rule out participation by private capital. He

made clear, however, that it would be subordinated to Mexican control. Nego-

tiations between the two countries would founder repeatedly on that issue,

which was crucial to nationalization. The Mexicans laid down two absolutes

which remained intact through 1950: the nation must retain ownership of the

subsoil rights; and PEMEX would continue its domestic monopoly. The State

Department accepted those boundaries. The actual ownership of the subsoil

made little difference if the companies could secure a long-term operating

agreement; seeking oil for export, they had little interest in Mexico's internal

market. But the new subordination of capital become clear in the Mexican pro-

posal. It stipulated that the country would provide the property and the com-

panies the financing, labor, and skill; the firms would share in the profits but

have no evidence of ownership or creditorship. The proposal entailed con-

siderable risk for private capital, with little real control and an uncertain

payoff; most important of all, the resource remained under Mexican jurisdic-

tion. Perhaps not surprisingly, the State Department and the companies,

which it carefully consulted, rejected the ideas. By mid-1944 the opponents of

nationalization appeared to have run into a cul-de-sac.32

Indeed, they nearly lost control of Mexican oil policy to a rival agency,

Ickes's Petroleum Administration for War (PAW), which took a more favora

view of the nationalization. Foreign oil policy had been running on two tracks

since 1941 and generated frequent struggles between PAW and the State De-

partment. PAW awakened to the possibility of a shortage of domestic

petroleum and the resulting threat to national security well before the State

Department did. Ickes's strategists reasoned that Europe could rely on the

Middle Eastern pools while the United States could draw on hemispheric

sources. Ralph K. Davies, deputy administrator of PAW and a former Standard

of California vice-president, suggested the embryo of the plan in October 1941,

31 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1942, VI, 529; Foreign Relations of the United States,

1943 (6vols., Washington, 1963-1965), VI, 474-75; Foreign Relations of the United States, 1944 (7

vols., Washington, 1965-1968), VII, 1340.

32 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1944, VII, 1341.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Good Neighbor Policy and Mexican Oil 77

even before the creation of the Cooke-Zevada commission: "The United States

must have extra-territorial petroleum reserves to guard against the day when

our steadily increasing demand can no longer be met by our domestic supply.

. . . Looking ahead-and not so very far ahead-the petroleum resources of

Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, and other Caribbean countries must be con-

sidered to be reserves for the United States. They are, in fact, more important

to the United States than to the countries that have them, because they are

more vital to the life of the consumer than the producer. "33

Ickes was more flexible in trying to attain his imperial goals than was the

State Department. He wanted the government to buy controlling interest in

the Middle Eastern holdings of California-Arabian Standard Oil Company.

When that failed, he proposed that the government build a pipeline from Saudi

Arabia to the Mediterranean. Both the State Department and the oil companies

vigorously opposed his adventures, for they feared this government encroach-

ment on their traditional domains. Ickes tried to assure them that he was not

putting the government in the oil business. But he was a Bull Moose Pro-

gressive who was deeply suspicious of monopolies and made extension of

federal control of natural resources one of the hallmarks of his secretaryship.

He had toyed with the idea of having the domestic oil industry declared a

public utility. And he confided to his intimates that he would like to na-

tionalize the oil industry. This may have been nothing more than a cry of

frustration in the face of opposition. But nevertheless it was clear that the

Ickes/PAW group, although just as thirsty for foreign oil as the State Depart-

ment and the companies, did not feel obliged to obtain the resource through

capitalist means.34

The dichotomy between public and private ventures brought PAW and the

State Department into conflict from the start. Ickes thought Mexico was well

rid of the oil companies. They had worked against the interests of the host

countries, "suborned" officials, and caused revolutions. Mexico should never

let them return. Ickes naively proposed that the United States government buy

the assets of the companies that Mexico had nationalized. Roosevelt gently

punctured this bizarre trial balloon with the observation that the Mexicans

would scarcely accept such an offer.35

Ickes's other ideas about Mexican oil were more realistic and showed a gen-

uine willingness to bolster the nationalization. In 1942 a PAW technical mis-

sion, headed by DeGolyer, conducted a study of PEMEX. The report, which

was a good deal more favorable to the state firm's operations than the State

Department, recommended that the United States extend financial and tech-

nical assistance to PEMEX. The State Department dragged its feet; it first

wanted a signal from Mexico that it would accept private capital again. But

33 Ralph K. Davies to Ickes, Oct. 15, 1941, in Ickes to Roosevelt, Oct. 18, 1941, "Petroleum

Coordinator" folder, confidential file 12, Roosevelt Papers.

34 Stoff, Oil, War, and American Security, 75-87; Davies notes on discussion with Ickes and

others about Anglo-American oil agreement, July 1944, Ralph K. Davies Papers (Harry S. Truman

Library, Independence, Mo.).

35 Messersmith to Hull, July 21, 1944, "Mexico" folder, box 18, Petroleum Division, Records o

the Department of State; Ickes to Roosevelt, Feb. 20, 1942, official file 56, Roosevelt Papers;

Roosevelt to Ickes, Feb. 28, 1942, ibid.

This content downloaded from

187.217.54.7 on Wed, 01 Mar 2023 17:06:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms