Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Where Is Here When Is Now

Where Is Here When Is Now

Uploaded by

Cristopher GuidoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Harold Searles The Nonhuman Environment in Normal Development and SchizophreniaDocument463 pagesHarold Searles The Nonhuman Environment in Normal Development and Schizophreniaadam100% (11)

- On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored - Psychoanalytic Essays On The Unexamined Life Adam PhillipsDocument148 pagesOn Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored - Psychoanalytic Essays On The Unexamined Life Adam PhillipsTanja Baudoin91% (11)

- Totem and Taboo: RESEMBLANCES BETWEEN THE PSYCHIC LIVES OF SAVAGES AND NEUROTICSFrom EverandTotem and Taboo: RESEMBLANCES BETWEEN THE PSYCHIC LIVES OF SAVAGES AND NEUROTICSNo ratings yet

- CP47 1 DimenDocument45 pagesCP47 1 DimennemismdNo ratings yet

- SIGMUND FREUD Ultimate Collection: Psychoanalytic Studies, Theoretical Essays & Articles: The Interpretation of Dreams, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Dream Psychology, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Totem and Taboo, Leonardo da Vinci…From EverandSIGMUND FREUD Ultimate Collection: Psychoanalytic Studies, Theoretical Essays & Articles: The Interpretation of Dreams, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Dream Psychology, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Totem and Taboo, Leonardo da Vinci…No ratings yet

- Totem and TabooDocument288 pagesTotem and TabooL.C100% (4)

- Connolly 2015Document20 pagesConnolly 2015Anonymous KgUtPlkj100% (1)

- Edward Whitmont in PerspectiveDocument6 pagesEdward Whitmont in PerspectiveCelia SteimanNo ratings yet

- Helen Morgan - Living in Two Worlds - How Jungian' Am IDocument9 pagesHelen Morgan - Living in Two Worlds - How Jungian' Am IguizenhoNo ratings yet

- The Analytic Third - OgdenDocument11 pagesThe Analytic Third - Ogdenfuckyouscribd2013041100% (5)

- Popular Training Systems Adapted To Neurotype - Part 1 - German Volume Training - ThibarmyDocument25 pagesPopular Training Systems Adapted To Neurotype - Part 1 - German Volume Training - ThibarmyKomkor Guy100% (1)

- M. Little - EngDocument31 pagesM. Little - EngGabriela TârziuNo ratings yet

- Bromberg Standing in The SpacesDocument24 pagesBromberg Standing in The SpacesTiberiuNo ratings yet

- Authenticity As An Aim of Psychoanalysis: Key Words: Liveliness, False and True Self, AlienatingDocument28 pagesAuthenticity As An Aim of Psychoanalysis: Key Words: Liveliness, False and True Self, AlienatingMaria Laura VillarrealNo ratings yet

- A Dialogue of Unconsciouses PDFDocument10 pagesA Dialogue of Unconsciouses PDFIosifIonelNo ratings yet

- Beyond OedipusDocument25 pagesBeyond OedipusNick JudsonNo ratings yet

- Alan Bass Interpretation and DifferenceDocument217 pagesAlan Bass Interpretation and DifferenceValeria Campos Salvaterra100% (1)

- 9 When Words Are Used To TouchDocument14 pages9 When Words Are Used To TouchDaysilirionNo ratings yet

- The Essence of Psycho-Analysis - SymingtonDocument16 pagesThe Essence of Psycho-Analysis - SymingtonanaNo ratings yet

- Birthing The TranspersonalDocument24 pagesBirthing The TranspersonalminosthemichiNo ratings yet

- Spirituality, Hypnosis and Psychotherapy: A New PerspectiveDocument17 pagesSpirituality, Hypnosis and Psychotherapy: A New PerspectiveTalismaniXNo ratings yet

- Attachment and SchizophreniaDocument5 pagesAttachment and SchizophreniaAntonio TariNo ratings yet

- SimeonrevDocument6 pagesSimeonrevRehan ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Ten Pillars of Jungian Approach To EducationDocument13 pagesTen Pillars of Jungian Approach To Educationalvarod100% (1)

- Wo JT KowskiDocument16 pagesWo JT KowskiAna Belén CardinaliNo ratings yet

- The Collected Works of Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytic Studies, Theoretical Essays & Articles: The Interpretation of Dreams, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Dream Psychology, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement, Leonardo da Vinci…From EverandThe Collected Works of Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytic Studies, Theoretical Essays & Articles: The Interpretation of Dreams, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Dream Psychology, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement, Leonardo da Vinci…Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Alan Sanderson 1 6 03 Spirit Release PDFDocument7 pagesAlan Sanderson 1 6 03 Spirit Release PDFJoannaLinNo ratings yet

- O'Shaughnessy, E., Harrison, A. and Alvarez, A. (1999) - Symposium On FrustrationDocument17 pagesO'Shaughnessy, E., Harrison, A. and Alvarez, A. (1999) - Symposium On FrustrationJulián Alberto Muñoz Figueroa100% (1)

- Space and Time in Psychoanalytic Listening: Rosine Jozef PerelbergDocument19 pagesSpace and Time in Psychoanalytic Listening: Rosine Jozef PerelbergnosoyninjaNo ratings yet

- Totem Taboo Resemb 00 FR EuDocument288 pagesTotem Taboo Resemb 00 FR EuΕιρηνηΝικολοπουλουNo ratings yet

- Summons to Berlin: Nazi Theft and A Daughter's Quest for JusticeFrom EverandSummons to Berlin: Nazi Theft and A Daughter's Quest for JusticeNo ratings yet

- Reverie and O - JemstedtDocument7 pagesReverie and O - JemstedtErin SaldiviaNo ratings yet

- Of .Jan IrwinDocument44 pagesOf .Jan IrwinVivek BhatNo ratings yet

- Concreteness, Dreams, and Metaphor: Their Import in A Somatizing PatientDocument19 pagesConcreteness, Dreams, and Metaphor: Their Import in A Somatizing Patientmiriamheso100% (1)

- Beyond Death Transition and The AfterlifeDocument11 pagesBeyond Death Transition and The Afterlifeproyecto_hispanayaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of S. Freud's "The Unconscious"Document3 pagesAnalysis of S. Freud's "The Unconscious"Alper MertNo ratings yet

- Psychology of the Unconscious (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study of the Transformations and Symbolisms of the LibidoFrom EverandPsychology of the Unconscious (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study of the Transformations and Symbolisms of the LibidoRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Narcissism: Is It Still A Useful Psychoanalytic Concept?: Eike HinzeDocument6 pagesNarcissism: Is It Still A Useful Psychoanalytic Concept?: Eike HinzetonkkooNo ratings yet

- True Detective, Pessimism BuddhismDocument21 pagesTrue Detective, Pessimism BuddhismLesco GriffeNo ratings yet

- Frankl'd Logotherapy A New Orientation in CounselingDocument14 pagesFrankl'd Logotherapy A New Orientation in CounselingAlan Da Silva VerasNo ratings yet

- Character and the Unconscious - A Critical Exposition of the Psychology of Freud and of JungFrom EverandCharacter and the Unconscious - A Critical Exposition of the Psychology of Freud and of JungNo ratings yet

- Talking As Dreaming. OgdenDocument16 pagesTalking As Dreaming. OgdenMariane Noto0% (1)

- ComplexDocument5 pagesComplexsisiner09 DascăluNo ratings yet

- Who Am I? The Self/Subject According To Psychoanalytic TheoryDocument15 pagesWho Am I? The Self/Subject According To Psychoanalytic TheoryAna IrimiaNo ratings yet

- Synchronicity in A New LightDocument25 pagesSynchronicity in A New LightRobin RobertsonNo ratings yet

- Trastorno PersonalidadDocument14 pagesTrastorno PersonalidadAura LolaNo ratings yet

- How They Do It - Examination of Political PonerologyDocument43 pagesHow They Do It - Examination of Political PonerologyRobert Joseph100% (1)

- Capitulo 2 BebeeDocument23 pagesCapitulo 2 BebeeMauricio PonceNo ratings yet

- Carl Jung: Early Life and CareerDocument9 pagesCarl Jung: Early Life and CareerReinhärt DräkkNo ratings yet

- ABENDENGLISHDocument8 pagesABENDENGLISHibn.richard8774No ratings yet

- Uncanny Belonging: Schelling, Freud and The Vertigo of FreedomDocument252 pagesUncanny Belonging: Schelling, Freud and The Vertigo of FreedomȘtefania CiobanuNo ratings yet

- On EmpathyDocument11 pagesOn EmpathyPaulina EstradaNo ratings yet

- The Collected Works of Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytical Studies, Articles & Theoretical EssaysFrom EverandThe Collected Works of Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytical Studies, Articles & Theoretical EssaysNo ratings yet

- Totem and Taboo: Widely acknowledged to be one of Freud’s greatest worksFrom EverandTotem and Taboo: Widely acknowledged to be one of Freud’s greatest worksNo ratings yet

- Totem and Taboo: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodFrom EverandTotem and Taboo: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodNo ratings yet

- Tart 1978eDocument7 pagesTart 1978eIno MoxoNo ratings yet

- Iwr - Quarter 1 Exam (11-Hums-Als)Document3 pagesIwr - Quarter 1 Exam (11-Hums-Als)JerryNo ratings yet

- Cellular Automata Are GenericDocument16 pagesCellular Automata Are GenericgnugplNo ratings yet

- Dairy Management Dr.a.deyDocument45 pagesDairy Management Dr.a.deyavijitcirbNo ratings yet

- Announcement of Test Date, Time and VenueDocument240 pagesAnnouncement of Test Date, Time and VenueAriful IslamNo ratings yet

- Research Methods - SamplingDocument34 pagesResearch Methods - SamplingMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Final Exam Intro SociologyDocument13 pagesFinal Exam Intro SociologyJoseph CampbellNo ratings yet

- Motion To Discharge Accused Fro Inpatient Rehab - HernaneDocument3 pagesMotion To Discharge Accused Fro Inpatient Rehab - HernaneJeddox La ZagaNo ratings yet

- 118ConvoList 16.06.2021Document6,661 pages118ConvoList 16.06.2021Sandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Reviewer Finals Maternal and Child NursingDocument15 pagesReviewer Finals Maternal and Child NursingChristine Airah TanaligaNo ratings yet

- English: Quarter 1 - Module 7Document26 pagesEnglish: Quarter 1 - Module 7Jhing Loren86% (14)

- Task 1 (Primera Tarea) : ActualizaciónDocument3 pagesTask 1 (Primera Tarea) : ActualizaciónDiegoMartelVazquezNo ratings yet

- Exclusive Seller Representation Agreement Feb 4Document5 pagesExclusive Seller Representation Agreement Feb 4Md IslamNo ratings yet

- ASHA Statement On CASDocument3 pagesASHA Statement On CASAGSpeechLPNo ratings yet

- GC 121 Insulin Assays RB 20190501Document4 pagesGC 121 Insulin Assays RB 20190501Syed Gulshan NaqviNo ratings yet

- Jigsaw IIDocument1 pageJigsaw IIapi-239373469No ratings yet

- chp11 Leadership EnglishDocument5 pageschp11 Leadership EnglishcaraNo ratings yet

- Notes in Ancient Indian ArchitectureDocument13 pagesNotes in Ancient Indian ArchitecturejustineNo ratings yet

- Ecology of PA ReportDocument19 pagesEcology of PA ReportJulius Lacaba AstudilloNo ratings yet

- HRM Self StudyDocument19 pagesHRM Self StudyZiyovuddin AbduvalievNo ratings yet

- Feedback Mechanism InstrumentDocument2 pagesFeedback Mechanism InstrumentKing RickNo ratings yet

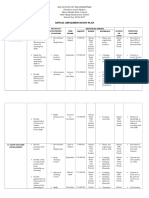

- Annual Implementation PlanDocument4 pagesAnnual Implementation PlanNeil Atanacio50% (2)

- Rismky-Korsakov - Scheherazade - Glenn Dicterow - Tonebase Violin WorkbookDocument12 pagesRismky-Korsakov - Scheherazade - Glenn Dicterow - Tonebase Violin WorkbookwilliamNo ratings yet

- Double Bar Graphs: Arithmetic Mean and RangeDocument4 pagesDouble Bar Graphs: Arithmetic Mean and RangeMidhun Bhuvanesh.B 7ANo ratings yet

- NDA PeroranganDocument2 pagesNDA PeroranganAdi SusenoNo ratings yet

- FS360 - Life Partner SelectionDocument71 pagesFS360 - Life Partner Selectioneliza.dias100% (17)

- Drugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravisDocument3 pagesDrugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravispapitomalosoNo ratings yet

- Admin STRMDocument442 pagesAdmin STRMjeromenlNo ratings yet

- Et 101 (B)Document5 pagesEt 101 (B)PUSHPA SAININo ratings yet

- Development of A Multi-Stage Choke Valve SizingDocument221 pagesDevelopment of A Multi-Stage Choke Valve SizingsekharsamyNo ratings yet

Where Is Here When Is Now

Where Is Here When Is Now

Uploaded by

Cristopher GuidoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Where Is Here When Is Now

Where Is Here When Is Now

Uploaded by

Cristopher GuidoCopyright:

Available Formats

The International Journal of

Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94:7–16 doi: 10.1111/1745-8315.12000

Where is here? When is now?1

Edna O’Shaughnessy

22 Heath Hurst Road, London NW3 2RX, UK – ednaos@btinternet.com

(Final version accepted 29 August 2012)

With a Kleinian perspective influenced by Betty Joseph, the author describes the

distinctive ‘here and now’ of a psychoanalysis as the place and the time of the

patient’s inner subjective world as it emerges in the work of patient and analyst.

This psychoanalytic ‘here’ and ‘now’ is examined with clinical material from the

analysis of Mr X; first, with an account of the way his analysis begins and then

through a detailed session five years later.

The author identifies Mr X’s problems with place and time, and how these change

over the course of the analysis. He moves from sequestered dyadic relationships

towards an Oedipal and family space, and from disconnection and timelessness to

acquiring a sense of duration, of being in the present with a past and a future –

all of which, the paper aims to show, has implications for technique.

If I say, like many diverse colleagues, that I try to work in the ‘‘here and

now’’, I may conjure up some contemporary disputes and some bits of his-

tory about place and time in psychoanalysis. As early as Freud’s Project

(Freud, 1897) in relation to problems in his seduction theory, Freud discov-

ered that the place with the more determining role in the patient’s illness

was not external reality but psychic reality with its unconscious phantasies.

Freud developed his psychoanalytic method through changes he made with

regard to time. His earlier techniques aimed to bring ‘‘directly into focus the

moment at which the symptom was formed’’ (Freud 1911, p. 147). The ana-

lyst tried to help the patient fill the gaps in his memory – to remember how

it happened ‘‘there and then’’. Later, with the discovery of transference and

the compulsion to repeat, Freud found different relations to time in ‘‘there

and then’’ and ‘‘here and now’’. Through the phenomenon of transference,

the past repeats itself in the present and in a psychoanalysis it becomes ‘‘a

piece of real life’’ (p. 152); that is, ‘‘at every point accessible to our interven-

tion’’ (p. 154), Freud tells us, ‘‘we must treat [the patient’s] illness, not as an

event of the past, but as a present-day force’’ (Freud 1914, p. 151). All this

has implications for analytic technique: the analyst’s evenly suspended atten-

tion, as I understand it, hovers over and focuses on illuminating psychic

reality, while material reality is kept in relative darkness (not darkness, mark

you, but relative darkness).

This shifting of analytic focus from external reality (‘‘practical’’ or ‘‘mate-

rial reality’’, as Freud also sometimes called it) to psychic reality was later

1

Editor’s note: These two papers, Edna O’Shaughnessy, ‘‘Where is here? When is now?’’, and Betty

Joseph, ‘‘Here and now: My perspective’’, were invited papers for the UCL Psychoanalysis Unit Annual

December Conference (12th December 2008–14th December 2008). The papers are part of a series

entitled ‘‘Here and Now’’ (Aguayo, 2011; Blass, 2011; Busch, 2011).

Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis

Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA on behalf of the Institute of Psychoanalysis

8 E. O’Shaughnessy

deepened and extended by Klein’s discovery of a whole inner realm of objects,

an unconscious world within that is in interplay with external reality (Klein,

1946). And later still, the Kleinian understanding of the role of projective

identification between patient and analyst threw further light on the process

of ‘‘transferring’’ between patient and analyst, showing how it is not only the

psychic reality of the patient that is involved but also, in an importantly dif-

ferent way, the psychic reality of the analyst (Klein, 1952); for both patient

and analyst the transference is, in Freud’s phrase, ‘‘a piece of real life’’.

This bit of history I give by way of introduction is to remind us that place

and time have distinctive natures in a psychoanalysis: they are ‘‘the here’’

and ‘‘the now’’ of psychic reality. In this paper I shall illustrate and try to

explore this psychoanalytic ‘‘here’’ and ‘‘now’’ with clinical material from

the analysis of Mr X; first, with an account of the way his analysis began,

and then with a detailed session from five years later.

Clinical Presentation

Mr X, an anxious, disconnected and young looking man in his mid-thirties,

worked for an international corporation. The youngest of three brothers, he

presented himself as ‘‘the little weak one who doesn’t know what to do’’,

which seems to have been a lifelong role. He said he wanted an analysis

because he experienced loneliness and unsettledness; he had few friends and

was unsure of his sexual orientation. In the preliminary interview he

described one or two homosexual affairs that were intense sexually but

which had interfered with his studies and his work, and also some brief rela-

tionships with girls who had chosen him rather than him having chosen

them – except for one, a secretary at work. She fell pregnant, had wanted to

have their baby and stay with him. But his parents and brothers told Mr X

she was tricking him into a marriage and persuaded him to give her money

for an abortion; Mr X had feelings of guilt and loss about this. He said his

mother was frightening and disinterested in him, although his father was a

sensitive man and more human.

More immediately, Mr X sought analysis because of a crisis at work: he

had become very involved with a male colleague who had then treated him

with public contempt, a man who, in Mr X’s words ‘‘had messed things up

at the firm for him’’, and then to his distress a senior management had

bypassed him for promotion. He also told me that he had what he called ‘‘a

sort of a girlfriend’’ to whom he gave money to buy food for meals and for

shopping. She cooked supper for him; they had infrequent sex. Usually he

returned to his own flat for the night, sometimes drinking and watching

porn on the internet.

Mr X started analysis ‘‘being the new little one who doesn’t know what

to do’’: a complex presentation meant to draw me into making a special,

gentle pair with him. I would voice his fears and hopes and tell him what to

do. But I came to realise that the fears and hopes I was being invited to say

were ones he already knew about. It was a way of getting us close and, at

the same time, keeping us away from what was new or disturbing. Mr X

really was ‘‘a new little one’’, an anxious new patient, afraid of the impact

Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94 Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis

Where is here? When is now? 9

of analysis and the nature of his analyst; he was also anxious because he felt

he had little to give in the way of communication and he struggled with the

forces within himself. However, at the same time, if I listened carefully, I

could hear how he was sending me up as well as himself by acting like ‘‘the

little weak one’’, with an air of not knowing he was doing so and as if he

was speaking to an analyst so cut off that she wouldn’t notice but would

find him little and gentle and pleasing. This whole mixture had its pathos,

but it was also irritating, confusing and disabling. Often I didn’t know how

to think about or what to select from the many aspects involved. Did my

irritation come from his projection into me of an inner hostile and false

maternal figure? Or was I irritated by his acting which, even as he commu-

nicated something, mocked it and spoilt it? Or was it his debasement of me?

Or perhaps all three? Yet I was also aware of his felt need for something

and at the same time how anxious and inaccessible he was, and that what

he said lacked resonance – it was concretely just itself with no undertones

or overtones of meaning (Joseph, 1993). Often everything I contemplated

saying would seem wrong in some way and I felt I became like him: I too

didn’t know what to do. I worried about Mr X getting from me merely ‘‘a

sort of analysis’’, our relations being rather like Mr X’s relations with his

‘‘sort of a girlfriend’’.

Often I focused on the overall atmosphere of ‘‘not knowing what to do’’:

how he wanted something from me and at the same time he was hostile and

mocked himself and me. He was afraid and didn’t know what to do and he

felt anxious that I too didn’t know what to do for him, and so we would do

nothing. During this opening phase Mr X told no dreams, but one day,

unusually, he brought an image. He described how on the way to his session

he had noticed a house and its garden outside. It was a tidy garden that had

been swept bare, except that in a corner there was a plant with two blue,

delicate flowers. What seemed to me foremost and new was that Mr X had

noticed the house and how the garden was, and he had been able to bring

what he had seen to his session and tell it as a communication. It was a sig-

nificant movement away from his usual concrete way of ‘‘acting in’’ with me

towards awareness (Segal, 2008, p. 65) and the gaining of some insight, to a

degree, of symbolic representation. I spoke to him about how I thought the

house and its garden outside expressed his new awareness of himself, the

sessions and me. I said that we were like the two blue flowers in a corner,

close and delicate with each other, while the session was swept bare of dis-

turbing things, like his hostility or his fear that I get irritated and restive

and might not want to be a delicate blue flower with him.

Mr X’s communication of the image of the two blue flowers in a garden

outside the house and my interpretations of it are examples of the patient

and the analyst trying to throw light on the ‘‘here and now’’ of the psychic

reality of an analysis. But where is ‘‘here’’? In material reality, Mr X was in

analysis: he came for sessions and in a corner of my consulting room I sat

in my chair and he lay on my couch. However, in psychic reality I think he

was in a corner of a garden outside the house of analysis. I also spoke to

him about how he tried to get me to join him outside the ordinary frame of

analysis and be with him in a special tender way that was perhaps a little

Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94

10 E. O’Shaughnessy

blue too – seduced and sexualised together. I think Mr X really understood

this. From accounts he gave at this time, this was also the way he tried to

manage psychic pressures in his place of work. He paired closely with some-

one in the firm, and tried to feel that they were in a place apart from the

ordinary workplace, free from the anxieties of rivalry, difference, hostility,

competence, etc. Mr X’s ‘‘here’’ can be anywhere and in this sense is unre-

stricted by the particularities of reality. It is how he is everywhere. Bion has

often illuminated the difference between space and time in psychic and in

external reality; for example, he describes the vast distances in mental space

and time of the psychotic patient (Bion, 1957). Indeed, there were times in

the analysis and elsewhere when Mr X believed he really was in a ‘‘special’’

place with a special relationship; he had what Britton calls a ‘‘counter-

belief’’: a belief of psychic reality that cancels and replaces external reality

(Britton, 1995).

Mr X and I struggled on and slowly he became more able to allow the

return of some of the things he had swept out of the sessions. Of particular

importance were his fears and doubts about me, his anxious and resentful

suspicion that I had no genuine place for him, did not want or accept him,

and that I was hostile and devaluing. In the preliminary interview Mr X

had described his mother as frightening and with no interest in him; my

sense was that this might really have been so and Mr X had internalised a

female figure, which was ‘‘a house’’ that did not let him in but kept him on

the outside.

If the ‘‘here’’ where patient and analyst were changing and becoming a lit-

tle less bare, what of the ‘‘now’’? Mr X had little of the ordinary feeling of

the duration of his life. He brought no memories, screen or otherwise, from

childhood or later; almost all the facts I mentioned at the start of this paper

I knew from the preliminary interview. In this first period, recollections did

not return to him, nor did he experience what Klein calls ‘‘memories in feel-

ings’’ (Klein, 1957). He spoke only of current things in a way, as I remarked

above, that had no resonance. And when I interpreted myself as a house, a

female figure that did not let him in, I made no attempt at a construction

of the past because at this stage Mr X was cut off from his past. In ‘‘The

Schizoid Mode of Being and the Space-Time Continuum’’ Henri Rey (Rey,

1994) vividly describes patients like Mr X whose illness, in part, is their loss

of connectedness. They have broken the thread of life and, as Wolheim

(1984) has shown, the thread of a life is at the core of the inner unity of per-

sons and at the centre of personal identity (Flynn, 2008).

I shall now leave the first phase of Mr X’s analysis and present a session

from five years later when Mr X had succeeded in obtaining his much

longed for senior appointment. On the day before the session I will report,

Mr X had attended his first Senior Managers’ meeting in preparation for

the new post he would start a few weeks later.

Session

Mr X arrived looking happy. After lying down, he spoke animatedly about

the meeting of the day before, telling me about the various people present,

Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94 Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis

Where is here? When is now? 11

the topics discussed and his participation. His voluble account, which made

me pleased, was so different from his often cautious presentation of himself,

so that when he paused I remarked that today he was able to let me know

he was happy: he had joined in and enjoyed being in the Senior Managers

meeting. This remark changed his mood. With anger and contempt, he said,

‘‘It was just childish to be interested in a meeting like that’’. And then

angrier still, he said, ‘‘You said they were the Seniors, not me.’’ He repeated,

‘‘You said it!’’, now nearly shouting. I remarked on his sudden change from

happiness with me to contempt for himself and fury with me. He lay silent.

Then, after a while, I said that he had heard me in his mind’s ear saying he

was not a Senior but in reality I had not said that. Even as I said this,

though, it felt strange to be saying to my patient that I had not actually

said, ‘‘They were the Seniors not him’’, and only after the session, as I dis-

cuss below, could I begin to understand something about this. In the session

itself, in response to my denial, Mr X persisted and he repeated, ‘‘You said

it’’. I responded by suggesting that he had been so alarmed by the sudden

eruption of his anger and contempt when he called the meeting childish that

he had pushed these out of himself and into me, and then he heard me as

like a hostile mother, disparaging him. Mr X said nothing.

After a long while, making a noticeable effort, he said he’d had a dream

the night before. In his dream Mr X was already working in the section of

the firm of his new job. He was not dressed properly. He was wearing casual

clothes, old jeans and a T-shirt. A secretary came and said, ‘‘Don’t you

know you shouldn’t be dressed like that, you should wear a jacket and tie

like Senior Managers do.’’ She had a jacket, a shirt and a tie ready for him.

He took them from her and put them on. Suddenly, there was a baby sitting

on his shoulder and then the baby sucked him all over and made a huge

wet mess of his clothes. He realised he couldn’t wear them. It was hopeless

and he took them off.

As Mr X finished telling me his dream he sounded despairing and again

he fell into a long silence. I reflected on how complicated it all was. His

silence now in the session seemed to match his hopelessness in the dream,

his giving up when the baby messed his clothes. Yet he had started the ses-

sion so differently, engaged and happy to talk to me, the very way he had

been in the real Senior Managers meeting the day before where, unlike his

subsequent dream, he had not needed a secretary to tell him how to present

himself properly. As now, I thought, he waits for me to tell him what to do

– ask for associations, encourage him to talk, and so on – something of a

return to our old ‘‘two blue flowers’’ place, where I do for him what he

knows how to do for himself. Yet he had managed to tell me his dream.

And then I wondered – who was the spoiling baby that made the wet mess

in the dream?

As Mr X still lay silent I asked him about the child in the dream. He

answered at once that he knew who the child was: it was his brother’s child.

In reality, his brother’s child formed part of everything his eldest brother

had that Mr X, who had no son and had his one baby aborted, felt pain-

fully and enviously deprived of. In his dream, his brother’s child who made

Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94

12 E. O’Shaughnessy

a wet mess of him (who was then in reality 10 or 11-years-old) was a baby

from the past. The dream was set in the future when Mr X would be work-

ing in the new Senior section; it destroyed his pleasurable anticipation that

he would do well at his new job. In the session it was Mr X himself who,

with angry contempt, spoiled his and my pleasure in the Senior Managers

meeting of the day before by saying, ‘‘It was just childish to be interested in

a meeting like that.’’ I offered my interpretation that when he’d arrived

happy and told me about the interesting meeting he had felt that he was my

child, not his brother’s child, but his parents’ child. He was speaking to me,

his analyst, as a parent who would be pleased at his success.

After a long pause Mr X said ‘Maybe’.

I went on to say that we had seen a side of him that was made angry and

envious by the Managers meeting that went well and by his pleased regard

for me and my perceived pleasure in his achievement. That side of him

hated and spoiled these good relations and miscalled them ‘‘childish’’. In his

dream, however, he recognised that the hostile side was the baby, the burden

he carried on his shoulder.

Mr X replied guardedly, ‘‘It could be so.’’

Our time was up and there the session ended.

Discussion of Clinical Material

I hope it can be seen that over several years Mr X had changed, progressing

at his workplace and in some ways developing internally. In the reported ses-

sion he was not, as he was five years earlier, either in or aiming to construct a

‘‘blue-flower’’ dyad. To continue with his telling image of a garden and a

house, he had moved from pairing in an outside garden to being in the ana-

lytic house with me and against me. In this space, some of the things that he

had swept out earlier were beginning to return. His ego had strengthened; he

sustained some measure of contact under pressure, for example he managed

to tell me his dream even after I failed him. That is, Mr X was in a different

place. Moreover, the events of the session had gained some (though still few)

connections with the past and with his future: ‘‘now’’ was no longer a schi-

zoid instant but had regained something of its natural condition which, as

B. J. O’Shaughnessy puts it, ‘‘is internally…from–towards…the life of the self-

conscious being [has]…one end stretching back to the womb, the other end

moving into the unrealised future’’ (O’Shaughnessy, 1980, vol. 2, p. 312).

When the session started Mr X was in an Oedipal space, voluble and

happy after his successful Managers meeting of the day before, speaking in

a way that gave me pleasure. As his analyst I was the ‘‘they’’ of his parents

and he was my patient in the sense of being his parents’ child, happy to be

doing well and to tell me so. It was when I said this out loud that the

abrupt changes occurred that formed the emotional crux of the session.

With sudden anger and contempt Mr X said, ‘‘It was just childish to be

interested in a meeting like that’’ and more furious still, ‘‘You said they were

the Seniors, not me’’. And he repeated, ‘‘You said it!’’, almost shouting.

After his outburst I did something peculiar. I told him I didn’t say it, focus-

ing on external reality only and not paying enough attention to trying to

Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94 Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis

Where is here? When is now? 13

understand his experience; this was an enactment on my part, ‘‘acting in’’,

as we say. I am not sure whether it was from my own defensiveness or from

his projections or both, but at that moment I actually became his interna-

lised mother, who refused him the space to house his central, emotional pre-

dicament. Mr X was confusingly conflicted: he wanted real human relations

and almost simultaneously interfered with these. He became big and supe-

rior to real human relations, which – in a reversal of reality – he called

‘‘childish’’. When I spoke about him being with me and enjoying being his

parents’ child, I roused his hatred. Furthermore, I robbed his hostile side of

its bigness, which indeed he had already done in his dream where he had

exposed his hostility as a spoiling baby. His destructiveness was thus threa-

tened from within and without. It was revealed as an infantile burden that

Mr X carried on his shoulder, which made him feel big through a toxic mix

of sexualised destruction: his destructiveness sucked him all over, making a

huge wet mess, a big spoiling phallus. All this is to say that in his new and

forward moving Oedipal situation, Mr X’s experience was incoherent. His

enjoyment of success, along with his feelings of being his parents’ son,

afflicted him with the persecution of exposure and belittlement.

In the session I understood only partially what was happening. I recognised

that he was in an Oedipal place and that he had to instantly disown and pro-

ject his spoiling hatred of it into me so that he ‘‘heard’’ me saying, ‘‘They were

the Seniors not him’’. But I did not recognise the terrible incoherence of his

experience: how when he succeeds he is also undone. In the session I think

that Mr X kept some sense of himself as his parents’ child and so he managed

to keep some link with me. He made an effort – you will remember – and told

me his dream, although he was cautious about what I said to him, replying

‘‘Maybe’’ and ‘‘It could be so’’. I suspect I was then not a totally bad figure

for him, but a disturbing mixture that made him anxious and guarded.

However, I had lost an opportunity to understand and to speak to Mr X

about the eruption of his unsettled sexual orientation in the session: how we

saw it arise in an Oedipal situation in which he identified with his parents

and related his enjoyment to them. Consequently, a sexualised hatred

erupted in him – the baby on his shoulder which sucked him all over – that

turned him into a big phallus. Conceptualised in terms introduced by Dana

Birksted-Breen (Birksted-Breen, 1996), Mr X could neither settle into a tri-

angular Oedipal mental space with a penis-as-link nor settle into in a psy-

chic reality of phallic dyads. And indeed, unusually, the next day Mr X

returned, worried and depressed, and said he had been thinking a lot about

getting so angry with me and also about his dream. He knew it was all very

important and he wanted to talk more about it. It was important that he

did so, even if it was a little distant and tentative and I was a very uncertain

figure for him. His hostility stayed quiescent, although I think we both

knew that it would, and of course it did, soon erupt again.

If this was ‘‘where’’ we were, what about ‘‘the now’’ of the session? It was

very much of the present, and as opposed to before, it had various connec-

tions with the past. In Mr X’s dream there was his brother’s child, who was

in reality a twelve-year-old; but in the dream he was a baby Mr X knew in

his past, which represented his immature hostile side as it was when he was

Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94

14 E. O’Shaughnessy

a baby and which still was a baby: in other words it had not developed.

And in the transference of the session I became an early hostile maternal

figure who had no place for him. That is, the early difficult relations with

parents and brothers of the past were there in the ‘‘now’’ of the session.

And, as well as his past there was now also his future. His dream expressed

his foreboding that in the future, when he would be actually working in the

managerial section, the baby on his shoulder, which was the burden he car-

ried of unmitigated envy and destruction, would spoil it.

All this is to say that unlike before, when he existed in a kind of cut-off

instant, duration had entered Mr X’s psychic reality. There was now some-

thing of a connecting thread to his life. To express this in another way:

before there was timelessness, but now he lived in time.

Closing Comments

In their ‘‘General Introduction’’ to a selection of Betty Joseph’s papers enti-

tled Psychic Equilibrium and Psychic Change, Michael Feldman and Eliza-

beth Spillius give an excellent account of Joseph’s understanding of, and

the need in our technique for, psychic immediacy (Feldman, Spillius, 1989).

In my paper, which deploys a Kleinian approach that’s influenced by Betty

Joseph, I have presented some psychoanalytic work in ‘‘the here and now’’.

In the contemporary plural scene analysing in ‘‘the here and now’’ takes

diverse forms in clinical practice, as is shown in the variety of papers in

Time and Memory (Perelberg, 2007). But misgivings continue to be

expressed about this way of working. Analysing in ‘‘the here and now’’ has

been called ‘‘thin’’; it has been seen as an impoverishment of psychoanaly-

sis. Some have expressed anxiety that analysing in ‘‘the here and now’’ will

lead to a neglect of the patient’s past and his world of unconscious phan-

tasy; this would be especially terrible, for if Freud taught us anything it is

the force of the past and the power of unconscious phantasy. Of course,

analytic work may be thin or impoverished, but such poor work does not

come from working in the ‘‘here and now’’, on the contrary, it comes from

the very opposite. It is due either to some misconception about the ‘‘here’’

and ‘‘now’’, for example mistaking the material realities between patient

and analyst as being all there is and thus neglecting psychic reality. Or it is

due to neglect of what is really present in the ‘‘here and now’’ of a psycho-

analysis where there is always more going on than we could ever know or

interpret.

In the clinical situations described above, I think we can see the variation

in Mr X’s ‘‘here’’ and his ‘‘now’’. He started analysis in an anxious schizoid

state, disconnected from memories of his past, merely repeating his past

with me in a concrete way that was devoid of phantasy. He was threatened

by unmanageable persecutory anxieties and struggled to protect himself by

means of continuous splitting and an appeasing presentation of himself as

‘‘the little weak one who doesn’t know what to do’’; he aimed to restrict

and control me into making a gentle dyad with him. On rare occasions, for

example when he saw the two blue flowers in a garden outside a house, Mr

X was able to find the beginnings of symbolisation in concrete material

Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94 Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis

Where is here? When is now? 15

equivalent to his psychic situation. Later, as we saw in the detailed session,

his phantasy life came more alive: his dream expressed the phantasy of his

whole self becoming a big phallus, and the mental connection with his past

began to be restored along with anticipations of his future. Furthermore,

there was an important interplay between external and psychic reality: when

Mr X finally obtained his Senior appointment in external reality it affected

him internally, which in turn also affected his immediate relations with the

analyst. Rather than being thin or impoverished, I suggest that the nature

of and changes in ‘‘the here and now’’ of Mr X turned out to be complex

and crucial to the analytic process.

Moreover, I think that a guideline emerged with regard to technique. For

the analyst, the nature of the patient’s ‘‘here’’ and ‘‘now’’ proved a valuable

indicator for making or not making links with the patient’s history, or for

speaking or not speaking about phantasy. We have surely to wait until these

are there in the patient’s psychic reality.

To conclude, this paper is about place and time in psychic reality. I have

hoped to show something of the nature of Mr X’s problems with place and

time. As the analysis progressed, I hope to have shown some of the changes

in Mr X’s places and in his disconnections and reconnections with time, as

he moved from a dyadic towards an Oedipal and family space, which was,

however, a disturbing and possibly irresolubly difficult and contradictory

place for him. There is a human need for a place, a habitat in material and

also in psychic reality. There is also a natural need for awareness of duration

through memories and anticipations. In this paper, at the time I leave Mr X,

it was painfully uncertain for both patient and analyst where – in what

place and in which kind of time in psychic and external reality – Mr X

would be able to settle or whether perhaps he would remain unsettled.

References

Aguayo J (2011). The role of the patient’s remembered history and unconscious past in the evolution

of Betty Joseph’s ‘here and now’ clinical technique (1959–1989). Int J Psychoanal, 92:1117–1136.

Bion WR (1957). The differentiation of the psychotic from the non-psychotic personalities. Int J

Psychoanal 38:266–275. [Reprinted in: (1967). Second Thoughts: Selected papers on psycho-

analysis. London: Heinemann Medical Books.]

Birksted-Breen D (1996). Phallus, penis and mental space. Int J Psychoanal 77:649–657.

Blass RB (2011). On the immediacy of unconscious truth: understanding Betty Joseph’s ‘here and

now’ through comparison with alternative views of it outside of and within Kleinian thinking. Int J

Psychoanal, 92:1137–1157.

Britton R (1995). Psychic reality and unconscious belief. Int J Psychoanal 76:19–23.

Busch F (2011). The workable here and now and the why of there and then. Int J Psychoanal,

92:1159–1181.

Flynn D (2008). Exile: loss of connectedness. Bulletin of BPAS, 44: 8.

Feldman M, Spillius B (1989). General introduction to Psychic Equilibrium and Psychic Change. In:

Feldman M, Spillius B, editors. Selected Papers of Betty Joseph. London: Routledge.

Freud S (1914). Remembering, repeating and working-through. In: Strachey S, editor. The standard

edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud S (1911–1913). The case of Schreber, papers on technique and other works. In: Strachey S,

editor. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. London:

Hogarth Press.

Joseph B (1993). No resonance. In: Horowitz MJ, Kernberg OF, Weinshel EM, editors. Psychic struc-

ture and psychic change: Essays in honour of Robert S Wallerstein. Madison: International Univer-

sity Press.

Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94

16 E. O’Shaughnessy

Klein M (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanism. In: (1975). Envy and gratitude and other works

1946–1963. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis.

Klein M (1952). The origins of transference. In: (1975). Envy and gratitude and other works 1946–

1963. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis.

Klein M (1957) Envy and gratitude. In: (1975). Envy and gratitude and other works 1946–1963.

London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis.

O’Shaughnessy BJ (1980). The Will. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Perelberg RJ, editor (2007). Time and Memory. Psychoanalytic ideas series. London: Karnac.

Rey H (1994) The schizoid mode of being and the space–time continuum. In: Universals of psycho-

analysis in the treatment of psychotic and borderline states. London: Free Association Books.

Segal H (2008). In: Quinodoz JM, Listening to Hanna Segal. London: Routledge.

Wollheim R (1984). The thread of life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Int J Psychoanal (2013) 94 Copyright ª 2013 Institute of Psychoanalysis

You might also like

- Harold Searles The Nonhuman Environment in Normal Development and SchizophreniaDocument463 pagesHarold Searles The Nonhuman Environment in Normal Development and Schizophreniaadam100% (11)

- On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored - Psychoanalytic Essays On The Unexamined Life Adam PhillipsDocument148 pagesOn Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored - Psychoanalytic Essays On The Unexamined Life Adam PhillipsTanja Baudoin91% (11)

- Totem and Taboo: RESEMBLANCES BETWEEN THE PSYCHIC LIVES OF SAVAGES AND NEUROTICSFrom EverandTotem and Taboo: RESEMBLANCES BETWEEN THE PSYCHIC LIVES OF SAVAGES AND NEUROTICSNo ratings yet

- CP47 1 DimenDocument45 pagesCP47 1 DimennemismdNo ratings yet

- SIGMUND FREUD Ultimate Collection: Psychoanalytic Studies, Theoretical Essays & Articles: The Interpretation of Dreams, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Dream Psychology, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Totem and Taboo, Leonardo da Vinci…From EverandSIGMUND FREUD Ultimate Collection: Psychoanalytic Studies, Theoretical Essays & Articles: The Interpretation of Dreams, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Dream Psychology, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Totem and Taboo, Leonardo da Vinci…No ratings yet

- Totem and TabooDocument288 pagesTotem and TabooL.C100% (4)

- Connolly 2015Document20 pagesConnolly 2015Anonymous KgUtPlkj100% (1)

- Edward Whitmont in PerspectiveDocument6 pagesEdward Whitmont in PerspectiveCelia SteimanNo ratings yet

- Helen Morgan - Living in Two Worlds - How Jungian' Am IDocument9 pagesHelen Morgan - Living in Two Worlds - How Jungian' Am IguizenhoNo ratings yet

- The Analytic Third - OgdenDocument11 pagesThe Analytic Third - Ogdenfuckyouscribd2013041100% (5)

- Popular Training Systems Adapted To Neurotype - Part 1 - German Volume Training - ThibarmyDocument25 pagesPopular Training Systems Adapted To Neurotype - Part 1 - German Volume Training - ThibarmyKomkor Guy100% (1)

- M. Little - EngDocument31 pagesM. Little - EngGabriela TârziuNo ratings yet

- Bromberg Standing in The SpacesDocument24 pagesBromberg Standing in The SpacesTiberiuNo ratings yet

- Authenticity As An Aim of Psychoanalysis: Key Words: Liveliness, False and True Self, AlienatingDocument28 pagesAuthenticity As An Aim of Psychoanalysis: Key Words: Liveliness, False and True Self, AlienatingMaria Laura VillarrealNo ratings yet

- A Dialogue of Unconsciouses PDFDocument10 pagesA Dialogue of Unconsciouses PDFIosifIonelNo ratings yet

- Beyond OedipusDocument25 pagesBeyond OedipusNick JudsonNo ratings yet

- Alan Bass Interpretation and DifferenceDocument217 pagesAlan Bass Interpretation and DifferenceValeria Campos Salvaterra100% (1)

- 9 When Words Are Used To TouchDocument14 pages9 When Words Are Used To TouchDaysilirionNo ratings yet

- The Essence of Psycho-Analysis - SymingtonDocument16 pagesThe Essence of Psycho-Analysis - SymingtonanaNo ratings yet

- Birthing The TranspersonalDocument24 pagesBirthing The TranspersonalminosthemichiNo ratings yet

- Spirituality, Hypnosis and Psychotherapy: A New PerspectiveDocument17 pagesSpirituality, Hypnosis and Psychotherapy: A New PerspectiveTalismaniXNo ratings yet

- Attachment and SchizophreniaDocument5 pagesAttachment and SchizophreniaAntonio TariNo ratings yet

- SimeonrevDocument6 pagesSimeonrevRehan ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Ten Pillars of Jungian Approach To EducationDocument13 pagesTen Pillars of Jungian Approach To Educationalvarod100% (1)

- Wo JT KowskiDocument16 pagesWo JT KowskiAna Belén CardinaliNo ratings yet

- The Collected Works of Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytic Studies, Theoretical Essays & Articles: The Interpretation of Dreams, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Dream Psychology, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement, Leonardo da Vinci…From EverandThe Collected Works of Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytic Studies, Theoretical Essays & Articles: The Interpretation of Dreams, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Dream Psychology, Three Contributions to the Theory of Sex, The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement, Leonardo da Vinci…Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Alan Sanderson 1 6 03 Spirit Release PDFDocument7 pagesAlan Sanderson 1 6 03 Spirit Release PDFJoannaLinNo ratings yet

- O'Shaughnessy, E., Harrison, A. and Alvarez, A. (1999) - Symposium On FrustrationDocument17 pagesO'Shaughnessy, E., Harrison, A. and Alvarez, A. (1999) - Symposium On FrustrationJulián Alberto Muñoz Figueroa100% (1)

- Space and Time in Psychoanalytic Listening: Rosine Jozef PerelbergDocument19 pagesSpace and Time in Psychoanalytic Listening: Rosine Jozef PerelbergnosoyninjaNo ratings yet

- Totem Taboo Resemb 00 FR EuDocument288 pagesTotem Taboo Resemb 00 FR EuΕιρηνηΝικολοπουλουNo ratings yet

- Summons to Berlin: Nazi Theft and A Daughter's Quest for JusticeFrom EverandSummons to Berlin: Nazi Theft and A Daughter's Quest for JusticeNo ratings yet

- Reverie and O - JemstedtDocument7 pagesReverie and O - JemstedtErin SaldiviaNo ratings yet

- Of .Jan IrwinDocument44 pagesOf .Jan IrwinVivek BhatNo ratings yet

- Concreteness, Dreams, and Metaphor: Their Import in A Somatizing PatientDocument19 pagesConcreteness, Dreams, and Metaphor: Their Import in A Somatizing Patientmiriamheso100% (1)

- Beyond Death Transition and The AfterlifeDocument11 pagesBeyond Death Transition and The Afterlifeproyecto_hispanayaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of S. Freud's "The Unconscious"Document3 pagesAnalysis of S. Freud's "The Unconscious"Alper MertNo ratings yet

- Psychology of the Unconscious (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study of the Transformations and Symbolisms of the LibidoFrom EverandPsychology of the Unconscious (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): A Study of the Transformations and Symbolisms of the LibidoRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Narcissism: Is It Still A Useful Psychoanalytic Concept?: Eike HinzeDocument6 pagesNarcissism: Is It Still A Useful Psychoanalytic Concept?: Eike HinzetonkkooNo ratings yet

- True Detective, Pessimism BuddhismDocument21 pagesTrue Detective, Pessimism BuddhismLesco GriffeNo ratings yet

- Frankl'd Logotherapy A New Orientation in CounselingDocument14 pagesFrankl'd Logotherapy A New Orientation in CounselingAlan Da Silva VerasNo ratings yet

- Character and the Unconscious - A Critical Exposition of the Psychology of Freud and of JungFrom EverandCharacter and the Unconscious - A Critical Exposition of the Psychology of Freud and of JungNo ratings yet

- Talking As Dreaming. OgdenDocument16 pagesTalking As Dreaming. OgdenMariane Noto0% (1)

- ComplexDocument5 pagesComplexsisiner09 DascăluNo ratings yet

- Who Am I? The Self/Subject According To Psychoanalytic TheoryDocument15 pagesWho Am I? The Self/Subject According To Psychoanalytic TheoryAna IrimiaNo ratings yet

- Synchronicity in A New LightDocument25 pagesSynchronicity in A New LightRobin RobertsonNo ratings yet

- Trastorno PersonalidadDocument14 pagesTrastorno PersonalidadAura LolaNo ratings yet

- How They Do It - Examination of Political PonerologyDocument43 pagesHow They Do It - Examination of Political PonerologyRobert Joseph100% (1)

- Capitulo 2 BebeeDocument23 pagesCapitulo 2 BebeeMauricio PonceNo ratings yet

- Carl Jung: Early Life and CareerDocument9 pagesCarl Jung: Early Life and CareerReinhärt DräkkNo ratings yet

- ABENDENGLISHDocument8 pagesABENDENGLISHibn.richard8774No ratings yet

- Uncanny Belonging: Schelling, Freud and The Vertigo of FreedomDocument252 pagesUncanny Belonging: Schelling, Freud and The Vertigo of FreedomȘtefania CiobanuNo ratings yet

- On EmpathyDocument11 pagesOn EmpathyPaulina EstradaNo ratings yet

- The Collected Works of Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytical Studies, Articles & Theoretical EssaysFrom EverandThe Collected Works of Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytical Studies, Articles & Theoretical EssaysNo ratings yet

- Totem and Taboo: Widely acknowledged to be one of Freud’s greatest worksFrom EverandTotem and Taboo: Widely acknowledged to be one of Freud’s greatest worksNo ratings yet

- Totem and Taboo: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodFrom EverandTotem and Taboo: The Horror of Incest, Taboo and Emotional Ambivalence, Animism, Magic and the Omnipotence of Thoughts & The Return of Totemism in ChildhoodNo ratings yet

- Tart 1978eDocument7 pagesTart 1978eIno MoxoNo ratings yet

- Iwr - Quarter 1 Exam (11-Hums-Als)Document3 pagesIwr - Quarter 1 Exam (11-Hums-Als)JerryNo ratings yet

- Cellular Automata Are GenericDocument16 pagesCellular Automata Are GenericgnugplNo ratings yet

- Dairy Management Dr.a.deyDocument45 pagesDairy Management Dr.a.deyavijitcirbNo ratings yet

- Announcement of Test Date, Time and VenueDocument240 pagesAnnouncement of Test Date, Time and VenueAriful IslamNo ratings yet

- Research Methods - SamplingDocument34 pagesResearch Methods - SamplingMohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Final Exam Intro SociologyDocument13 pagesFinal Exam Intro SociologyJoseph CampbellNo ratings yet

- Motion To Discharge Accused Fro Inpatient Rehab - HernaneDocument3 pagesMotion To Discharge Accused Fro Inpatient Rehab - HernaneJeddox La ZagaNo ratings yet

- 118ConvoList 16.06.2021Document6,661 pages118ConvoList 16.06.2021Sandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Reviewer Finals Maternal and Child NursingDocument15 pagesReviewer Finals Maternal and Child NursingChristine Airah TanaligaNo ratings yet

- English: Quarter 1 - Module 7Document26 pagesEnglish: Quarter 1 - Module 7Jhing Loren86% (14)

- Task 1 (Primera Tarea) : ActualizaciónDocument3 pagesTask 1 (Primera Tarea) : ActualizaciónDiegoMartelVazquezNo ratings yet

- Exclusive Seller Representation Agreement Feb 4Document5 pagesExclusive Seller Representation Agreement Feb 4Md IslamNo ratings yet

- ASHA Statement On CASDocument3 pagesASHA Statement On CASAGSpeechLPNo ratings yet

- GC 121 Insulin Assays RB 20190501Document4 pagesGC 121 Insulin Assays RB 20190501Syed Gulshan NaqviNo ratings yet

- Jigsaw IIDocument1 pageJigsaw IIapi-239373469No ratings yet

- chp11 Leadership EnglishDocument5 pageschp11 Leadership EnglishcaraNo ratings yet

- Notes in Ancient Indian ArchitectureDocument13 pagesNotes in Ancient Indian ArchitecturejustineNo ratings yet

- Ecology of PA ReportDocument19 pagesEcology of PA ReportJulius Lacaba AstudilloNo ratings yet

- HRM Self StudyDocument19 pagesHRM Self StudyZiyovuddin AbduvalievNo ratings yet

- Feedback Mechanism InstrumentDocument2 pagesFeedback Mechanism InstrumentKing RickNo ratings yet

- Annual Implementation PlanDocument4 pagesAnnual Implementation PlanNeil Atanacio50% (2)

- Rismky-Korsakov - Scheherazade - Glenn Dicterow - Tonebase Violin WorkbookDocument12 pagesRismky-Korsakov - Scheherazade - Glenn Dicterow - Tonebase Violin WorkbookwilliamNo ratings yet

- Double Bar Graphs: Arithmetic Mean and RangeDocument4 pagesDouble Bar Graphs: Arithmetic Mean and RangeMidhun Bhuvanesh.B 7ANo ratings yet

- NDA PeroranganDocument2 pagesNDA PeroranganAdi SusenoNo ratings yet

- FS360 - Life Partner SelectionDocument71 pagesFS360 - Life Partner Selectioneliza.dias100% (17)

- Drugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravisDocument3 pagesDrugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravispapitomalosoNo ratings yet

- Admin STRMDocument442 pagesAdmin STRMjeromenlNo ratings yet

- Et 101 (B)Document5 pagesEt 101 (B)PUSHPA SAININo ratings yet

- Development of A Multi-Stage Choke Valve SizingDocument221 pagesDevelopment of A Multi-Stage Choke Valve SizingsekharsamyNo ratings yet