Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Leadership Impact On Home Learning Environment

Leadership Impact On Home Learning Environment

Uploaded by

Duncan RoseOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Leadership Impact On Home Learning Environment

Leadership Impact On Home Learning Environment

Uploaded by

Duncan RoseCopyright:

Available Formats

Inspiring leaders to

improve children’s lives

Schools and academies

Research Associate Report

Cath Yeneralski, Assistant Head, Thomas Hickman School, Aylesbury

Resource

Leadership strategies that impact positively

on the home learning environment for

families new to English

Summer 2012

Contents

Contents .............................................................................................................................................2

Abstract . ............................................................................................................................................3

Introduction .......................................................................................................................................4

Literature review ..............................................................................................................................5

Methodology ....................................................................................................................................8

Findings . ............................................................................................................................................9

Conclusions .....................................................................................................................................17

References .......................................................................................................................................20

Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................22

Disclaimer

In publishing Research Associate reports, the National College is offering a voice to practitioner leaders to

communicate with their colleagues. Individual reports reflect personal views based on evidence-based

research and as such are not statements of the National College’s policy.

2 © National College for School Leadership

Abstract

This study aims to provide school and leaders of Foundation Stage settings1 with an insight into the

leadership strategies used to support the home learning environment with a focus on families new to

English.

Recent reviews undertaken on behalf of the government (Allen, 2011; Field, 2010; Tickell, 2011) have

highlighted the importance of the Foundation Stage in a child’s life (0‑5 years) and the important role

parents and carers have to play in this. These early years are recognised to have a significant impact as

children grow up and it is important for parents and schools to work together to support a child in achieving

his or her potential in life.

This research concludes that there is a range of strategies schools and Foundation Stage settings can

implement that help parents support their children within their home learning environment. In this study

these were adapted to meet the needs of the individuals. The study also found that there were particular

leadership characteristics that contribute to such successful partnerships.

1 The research was carried out in schools with a Foundatiion Stage or an attached nursery. Its finding are therefore targeted at leaders of similar institutions.

3 © National College for School Leadership

Introduction

This study focuses primarily on how schools work with parents new to English, within the early stages of

education, to build a link that can positively impact upon the children’s home learning environment.

The key research questions were:

1. What do schools see as the relevance of the home learning environment?

2. What do schools do to encourage parents new to English to support their children’s learning at home?

3. What barriers have schools experienced when working with parents with limited English and how have

these been addressed?

4. What leadership skills are needed to work with parents new to English to support their children’s

learning?

As highlighted by recent reviews undertaken on behalf of the government (Allen, 2011; Field, 2010; Tickell,

2011), the Foundation Stage in a child’s life (0‑5 years) and the important role parents and carers have to

play in their children’s learning is very important. These early years are recognised to have a significant

impact as children grow up and it is important for parents and schools to work together to support a child in

achieving his or her potential in life.

This report is relevant to leaders of schools and Foundation Stage settings as it looks at how links with

parents can be built and sustained to support and positively impact upon the home learning environment.

4 © National College for School Leadership

Literature review

A child’s experiences during their early years provide the essential foundations for life.

Tickell, 2011:4

Field (2010) recognises that parents play a significant role in influencing their children’s futures, and this is

generally accepted (Desforges & Abouchaar, 2003). The review continues to acknowledge there is a weight

of evidence which shows that a combination of positive parenting, a good home learning environment and

parents’ qualifications can transform children’s life chances, and are more important to outcomes than class

background and parental income.

Waldman et al (2008) further recognise that the earlier the intervention, the better the outcome for the

child, though later is better than none. Later interventions to help poorly performing children can be effective

but, in general, the most effective and cost-effective way to help and support young families is in the

earliest years of a child’s life (Field, 2010). Waldman et al (2008) state further that a small investment in

the early years can make a significant impact later on. Allen (2011) adds to this emphasis in stating that the

Foundation Stage (0‑5 years) should have the same status as other key stages.

School leaders report that the most positive results occur when parents are on board in the

early stages of their child’s education.

Campbell, 2011:11

Activities such as sports day, nativity play or school fêtes, which encourage parents to enter the school

setting, are recognised as important, to help build good partnerships from which parents can engage with

their children’s learning, though as Harris and Goodall (2007) state, activities not directly related to learning

will have little impact on pupil achievement.

The Effective Pre-school and Primary Education Project (EPPE) is Europe’s largest longitudinal investigation

into the effects of pre-school education and care (Sylva et al, 2010). The research examines a group of

3,000 children; 2,800 drawn from randomly selected pre-school settings in England and a group of 200

children who had no pre-school experience. The research was concerned primarily with questions about

how the individual characteristics of children are shaped by the environments in which they develop. Sylva

et al (2010) recognise that children’s outcomes are the joint product of home and pre-school and that any

research on early education will have to take into account influences from the home.

EPPE investigated factors that might influence children’s development and identified their effects, for

example gender, birthweight, parental qualifications, employment, home learning environment, and

the educational context of children’s pre-school or primary school. They found that the home learning

environment remained a powerful predictor of better cognitive attainment at age 11 even after 6 years in

school (Melhuish, 2010). The relevance of the EPPE findings is recognised by recent government reviews by

Allen (2011) and Tickell (2011).

Home learning environment

Hunt et al (2011) recognise that parents, staff and managers have different definitions of early home

learning, though all practitioners did share a basic definition of the home learning environment (HLE) as

interaction between parent and child in a way that enables the child to learn.

As Melhuish (2010) acknowledges, the HLE is significant in supporting children’s potential to achieve. The

brain of a baby or young child who gets the interaction and stimulation needed for healthy development

is literally larger and more completely formed by the age of three than the brain of a child who has

experienced neglect (Allen, 2011; Roberts, 2009).

5 © National College for School Leadership

Research has highlighted the home learning environment as the single most important

behavioural factor influencing children’s outcomes at age three and five.

Field, 2010:42

The EPPE project looked at different home activity items and tested them individually to see if they predicted

over- or underachievement. Activities such as being read to, playing with numbers, painting and drawing, or

using songs, poems and rhymes, all had significant positive effects on boosting cognitive development and

achievement beyond that expected. Melhuish (2010) continues to state that family factors such as parents’

education, socio-economic status of the highest social class of occupation and income are also important;

however the HLE exerts a greater and independent influence on educational attainment.

Johnson et al (2008) cited in Field (2010) consider that evidence from EPPE suggests that children from

disadvantaged Indian and Bangladeshi families have better HLEs than comparable White British families and

that analysis has shown that the aspirations parents have for their children to continue in full-time education

is significantly higher among all minority groups than White British parents. Field recommends that further

research in this area would be informative to discover more about the diversity of parenting and HLEs that

promote high attainment.

The home learning environment is not bound by parental occupation, education or income, rather, as

Waldman et al (2008) suggest, it is about what parents do with their children, rather than who they are.

Different families may have different barriers to creating an effective HLE, however, Melhuish (2010) found

that parents can provide a high-scoring HLE irrespective of their own qualification level.

Barriers to effective partnerships with parents

When parents do not share the language or culture of the school staff the obstacles in the

way of home‑school staff are considerable.

Blackledge & Aljazir, 1996:87

Roberts (2010) observes that most parents want to do the best for their children, but some struggle to do

so, often because they don’t understand the important role they can play or know how best to support their

children’s development. Parents’ own backgrounds and experiences have an impact on how they engage

with their children’s Early Years experiences and later schooling (Ward, 2009). Hunt et al (2011) identified the

following as significant barriers to engaging parents:

—— parents’ lack of time

—— dislike of educational environment based on parents’ own school experiences

—— lack of confidence among some parents

—— parents having English as an additional language

These key barriers are also acknowledged by other research (Harris & Goodall, 2007; Ward, 2009) with

the former stating that parents who are viewed as ‘hard to reach’ often see the school itself as hard

to reach. Hunt et al (2011) reflect that the biggest barrier appears to be parents’ lack of time followed

by communication difficulties for parents who do not speak English. Hunt also considers that levels of

confidence were lowest among parents who did not speak English as their first language.

Coelho (1994) suggests that the main barriers to building links with parents new to English include:

—— parents working and having little time to help their children

—— parents feeling limited by their lack of fluency in English or the educational system

—— parents’ prior experience, in that in many countries the involvement of parents in their children’s

schooling is neither expected nor desired

6 © National College for School Leadership

Campbell (2011) identifies that where schools have made concerted efforts to engage hard-to-reach parents,

the evidence shows that the effect on pupil learning and behaviour is positive. Ward (2009) acknowledges

that rather than drawing unfavourable conclusions for the child when parents do not engage with Early

Years practitioners, questions should be asked as to why parents do not get involved and how they can be

supported to participate. This proactive response is highlighted by Roberts (2009) in stating that vulnerable

families need to be targeted and supported before children start to fall behind, while Hunt et al (2011)

comment that 52 per cent of Early Years settings that participated in their study offered targeted support to

parents where English was not the first language.

Engaging with parents

Hunt et al (2011) report that managers of settings involved in the study thought that inviting parents into

the setting was the most effective way of involving parents in home learning. Field (2010) acknowledges the

importance of using resources within the community and observes that informal networks can be important

sources of support and strongly influence the way they parent.

Schools that successfully engage parents in learning consistently reinforce the fact that

‘parents matter’. They develop a two-way relationship with parents based on mutual trust,

respect and a commitment to improving learning outcomes.

Harris & Goodall, 2007:5

The open-door policies operated by best-practice settings in the study conducted by Hunt et al (2011)

enabled many of the barriers to be overcome gradually. Campbell (2011) reflects that communication

strategies need to be personalised to fit the context while Ward (2009) also considers that employing

different means of communication is essential to ensure full coverage of a range of communication

styles. For example some parents may prefer spoken information, while others respond better to written

information. It is the way in which different forms of communication are used, combined and embedded

in a culture of co-operation and trusting relationships between Early Years practitioners and parents that

leads to effective partnerships (Glenn et al, 2006). In addition, Melhuish (2010) acknowledges that where

opportunities are provided for mixing with other parents who are better educated, some benefits for

parenting may exist as peer group learning is a possibility.

With reference to parents who have English as an additional language, Virani-Roper (2000) comments that

some parents do not like schools to encourage home language support because they want their children

to learn English as soon as possible. This highlights an area where parents may need support to recognise

the importance of valuing the child’s home language and particularly at Early Years encouraging children to

develop comprehension in their first language as this can aid their ability to communicate in English.

In their study, Hunt et al (2011) state that 41 per cent of parents reported that staff had offered help or given

information or support that had changed how they have helped their child at home and that 97 per cent of

parents who attended events held by settings had tried the HLE activities suggested. As Hunt et al (2011)

suggest, attending an event for parents at an Early Years setting is very effective in influencing the HLE.

Ward (2009) suggests that staff members need to be able to adjust their communication skills quickly and

diplomatically to a range of different partners and contexts. Working with parents requires getting their

views heard so parents and staff can work together. Ward (2009) also suggests that it will take time and

perseverance to find the right approach that will help individual parents, since they come from different

backgrounds and have different life experiences and values. As Roberts (2010) highlights, it is important to

take time to get to know parents so that information and ideas can be shared that are appropriate to their

level of confidence as well as relevant to their interests, culture and family life.

Having identified the importance of the HLE, its promotion with parents and the removal of barriers

associated with its development, this report focuses on the strategies used by a sample of schools and the

leadership implications of these.

7 © National College for School Leadership

Methodology

The views of a range of staff in school were used to investigate the four research questions. Interviews were

carried out in a small sample of four schools – two primary and two first schools ‑ to identify what strategies

they use to engage parents, how these impact on the HLE of children within their Foundation Stage setting

and what the leadership implications are.

All schools were recently graded outstanding or good by Ofsted and were recognised as having a high

number of children speaking English as an additional language (EAL), including some at an early stage of

learning English. It is recognised that this is a small sample of schools and the findings and conclusions

reflect this and limit their generalisation.

The schools studied have different dominant languages spoken by EAL children; for example one Catholic

school has recently adjusted provision to cater for a high number of Polish-speaking families new to England,

whereas another has had a high Pakistani population for many years.

The headteacher of each school was interviewed, and a further one or two interviews were carried out in

order to triangulate results. These additional interviews were carried out with a range of staff drawn from

assistant head, deputy head, Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) co-ordinator, special educational needs co-

ordinator (SENCO) and the Reception teacher or nursery manager.

8 © National College for School Leadership

Findings

How is HLE understood and valued by schools?

Many of the respondents found it difficult to give a clear statement to define the home learning

environment. This reflected the difficulties in obtaining a clear, consistent definition also recognised by the

study undertaken by Hunt et al (2011). Comments were made by respondents in this study relating to how

much children access literacy in their home environment, including whether the children are exposed to

books, whether they have stories read to them, are exposed to good models of language, talk about things

they have done, shop with parents, visit places of interest and use educational toys:

“It’s anything the children learn outside school.”

Deputy, first school

“It’s really about children engaging with their carers in terms of their learning.”

Headteacher, first school

The majority of interviewees commented on some EAL children as having a limited home learning

environment, for example they had not learned colours or numbers or might not have a written language at

home and therefore no access to books within the home environment. However, it was recognised that they

may have been taught other things and that, whatever their HLE experience, children:

“... don’t come as empty vessels... they come with lots of information and knowledge ... it’s

really about what they bring from home to school.”

Headteacher, first school

All respondents observed that the HLE was very important, hugely relevant to schools and an area that can

make a big impact on children’s learning if a strong partnership is achieved where parents are working

with schools. One headteacher reflected on her school’s changing pupil base with a growing number of

Polish immigrants choosing a Catholic school for their children as they enter the area. This highlighted the

importance of knowing children’s cultural background when they come into school:

“... so we can adapt our resources and our teaching to suit the children that we have.”

Headteacher, first school

With reference particularly to children with EAL, the importance of families valuing their home language was

identified:

“If they can’t talk then they are not going to be able to do anything. [They] need to be

fluent in their first language.”

EYFS co-ordinator, primary school

Having recognised the importance of the HLE for children, how were schools working with parents and

providing them with the skills to support this?

How schools work successfully with parents

“Hopefully we are providing a similar home learning environment in our classrooms as well.”

Reception teacher, first school

9 © National College for School Leadership

Schools used a wide range of resources and strategies to assist parents new to English engage in their

children’s learning and as a result support the HLE. The initiatives included curriculum workshops, pre-nursery

sessions, stay and play sessions and links with adult education to run courses for parents. However, in one

case, this was not viewed as a separate set of strategies to meet parents’ particular needs but one that was

equally applicable to all parents:

“In terms of parents who’ve got children who speak English as a second language we don’t

actually draw a distinction because to us they are all children and if it’s truly personalised

learning then you have to take each child from where their starting point is.”

Headteacher, first school

Most schools spoke of the importance of informal, non-threatening ways to get parents involved such as

inviting them to watch their children’s performances and attending summer fairs or helping with school

visits. Although as previously identified in the literature review, these activities may not impact on children’s

development directly (Harris & Goodall, 2007), there was a view that these activities were important for a

number of reasons:

“It’s non-confrontational for parents to watch their children perform, I think anything that

brings parents into school has to be a good thing.”

EYFS co-ordinator, primary school

Staff commented on having opportunities to build relationships with parents in an informal setting leading

to parents subsequently becoming more confident to join other more formal activities such as curriculum

workshops. Parents had the opportunity to meet other parents and build up a support network. This was

seen to be particularly important for families new to English as parents could support each other with

translation:

“It’s important for [the parents] to mix and share as it can be a bit isolating at times.”

SENCO, primary school

A further challenge highlighted was the difficulty in engaging with parents who work, although this could be

said of many parents who do speak English as a first language. In one school many of the Eastern European

parents are economic migrants and have entered the country to work and therefore:

“Getting hold of people and explaining how things work in school is probably the most

difficult thing.”

Headteacher, first school

Focusing particularly on Early Years and the families’ first experience of working with their child’s school,

those interviewed all described a range of strategies used to build links, such as home visits, workshops for

new starters in the summer term before school starts in the September, parent interviews and visiting pre-

schools.

One headteacher commented on her attendance at a Catholic mass in Polish and the Saturday Polish school

on occasion. She saw this as an important and valuable way of establishing the link between school and the

Polish community. It also gave parents a familiar face and someone to approach with questions. In the same

school, part of the bursar’s job has become helping people complete the admission forms online, particularly

for parents who need support in understanding the forms or have no access to the internet at home.

It was highlighted that all staff have a part to play in these initiatives and this is reflected in one

interviewee’s statement that:

“It’s led by everybody and it starts before the children even come in.”

Assistant head, first school

10 © National College for School Leadership

Once links had been built up and the children settled, school leaders commented that they then introduce

curriculum sessions with the aim of supporting parents to help their children at home. These were led by

curriculum co-ordinators and release time was organised within the schools for them to plan and deliver

the sessions. One head stated that the school builds in time at the end of the curriculum workshops, when

it is more informal, to aid dialogue with parents and build up relationships so parents feel confident to take

part in the sessions. This was seen as having a significant impact and reflects a point highlighted by Roberts

(2010).

“It’s more informal, you can get a cup of tea, walk around and talk to people one at a time

and I’ve had quite a few, and I would say they were mostly EAL parents, who have waited

because they didn’t want to put their hand up in the meeting and ask the question, but they

just sort of cornered someone after the meeting.”

Deputy, first school

School leaders made use of external agencies where they could, such as a children’s centre on site,

adult education services and English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) facilities. These links have

been particularly positive where leaders have identified the best use of the resources matched to the

school’s cohort and its needs. Analysis of need was therefore a leadership activity that informed this. One

interviewee commented that the school received funding to run an ESOL course. They valued this service

contribution and made the decision to subsequently employ the teacher for one day a week to work with

particular families. For example, the teacher introduced the parents to lots of different activities in the local

community that parents could adopt with their children.

Another school engaged adult education services to run literacy and numeracy courses to support a growing

number of parents who were new to English. This did not cost the school beyond providing a space for the

course to run.

All the schools had programmes that relied on staffing and time rather than cost. Leaders gave a high

priority to working with parents to help them support their children’s learning with associated initiatives built

into the yearly plan:

“Time is obviously very precious but if you plan for it beforehand you can build it into your

school year.”

Headteacher, first school

In addition to inviting parents into school, one school sent home the children’s books for a weekend at the

end of each term for children to share with their parents and for the parents to make comments on. This was

recognised as a way of getting the children to talk to their parents about what they had learned at school,

hence consolidating their learning at home and enabling shared understanding of both what had been

learnt and the language associated with it. In addition to this the school used parents’ comments to target

their understanding and answer their questions. This further impacted on the HLE as parents were more

empowered to support their children’s learning at home:

“We want the parents to look at it and the children to talk to their parents about their

learning, to explain what they have done in their books and I always say to parents, if your

child can’t do this then we have failed... all parents write comments including the ones who

don’t have very good English but they make their points [come] across.”

Headteacher, first school

Overcoming barriers when working with parents new to English

Barriers identified by those interviewed came under two main headings, language and cultural. In looking

at these two issues it is important to recognise that some did not identify a separate set of barriers when

working with this group of parents:

11 © National College for School Leadership

“I don’t see a different set of barriers working with parents new to English... there’s a raft of

barriers and we just have to, as a team, look at what we can do to overcome those.”

Headteacher, primary school

Another school leader made the following observation:

“We don’t have barriers... if there was an issue... we don’t see it as a barrier we see it as an

opportunity of engaging with the parents at a deeper level.”

Headteacher, first school

Language barriers

All the schools used members of staff to support parents as translators. Comments were made about having

to work harder to ensure that parents’ perspectives and contributions were elicited when they did not speak

English, and finding ways to communicate effectively with them:

“... to ensure they are achieving the same communication links as other parents”

Assistant head, first school

School leaders needed to find ways to build on parents’ confidence as some could be reluctant to come into

school because they were learning the language themselves and could feel shy and/or under confident.

As recognised by Hunt et al (2011), levels of confidence are lowest in parents who speak English as an

additional language.

It would be very difficult to provide an interpreter on every occasion for all the different languages in a

school so it was essential to find different ways to support parents on a daily basis. Schools stated that they

introduce parents to members of staff that speak or understand their language. This, alongside building

relationships among parents themselves, was seen to support parents new to English and provide a more

sustainable and manageable system to support communication than contracting interpreters.

“I looked in the classroom and I saw a note pinned to the wall and it was about why a

little boy had been away the day before and it was all in Polish... I thought that was really

quite nice that they feel they can do that or they can ring up and ask to speak to the Polish

teacher if they are worried or anxious about something.”

Headteacher, first school

When using parents as interpreters, school leaders considered that it was important to find an appropriate

parent to translate as there may be sensitive areas to talk about. In terms of supporting the HLE, this was

particularly relevant when working with parents to support a child with special needs. One SENCO highlighted

the importance of linking up with local resources, for example by making the most of the local cultural centre

to find a translator who could support parents new to English in understanding what their child’s difficulties

were and what support the child needed.

Concerns were highlighted in relation to parents trying to support their child in learning English, rather

than speaking to them in their home language. This, it was considered, might lead to a child developing

limited language skills. As Blackledge & Aljazir (1996) recognise, the better developed children’s conceptual

foundation in their first language, the more likely they are to develop high levels of conceptual abilities in

the language of the school. This point was also identified by school leaders interviewed for this study.

The importance of making supporting resources available was identified by school leaders. These included

home language newsletters, multilingual posters, resources that reflect diversity and dual language books.

The impact of using dual language books to impact upon the HLE was advocated by one school leader

particularly as she saw that using these books gave parents the school’s seal of approval to support their

children in their home language.

12 © National College for School Leadership

“Dual language books made the parents feel more confident, because it’s something from

the school and they are doing it in their own language, it’s made them feel confident they’re

helping the child in the right way.”

Deputy head, first school

Cultural barriers

Each of the schools had initiatives to meet the needs of their particular parents, for example, one school ran

an Asian ladies group. The need emerged for this group because a lot of the Asian women did not socialise

in the community and so the school took a lead in providing a base for this:

“Many of our Asian parents are very nervous and insecure about health matters... cold

weather, when we had the snow they thought it was dangerous that I had let the school

open... there is a lot of misrepresentation really about ideas.”

Headteacher, primary school

Support sessions were also offered by schools and these, at times, bridged health and learning and broached

cultural aspects, for example the appropriate food to include in a packed lunch, why your child needs to

come to school and the detrimental effect of extended holidays. Not only were these supporting the child’s

HLE but they also helped build links with health needs, an aspect highlighted as important by the recent

Allen review (2011).

School leaders mentioned the importance of ensuring the school’s offer, including a broad curriculum, was

one in which all children and parents could see themselves as part of the school:

“Our school should be a mirror of the children who are here... so when they come into our

school they should be able to see themselves either in other people or in the resources that

we offer them... they should never feel that they are the only child.”

Headteacher, first school

Again, investment in a range of multicultural resources and considering how the curriculum might be

adapted to reflect children’s varied backgrounds, for example learning about different countries, were

suggested as ways to support the HLE. Also, interviewees commented on the importance of providing

opportunities for parents to contribute in the school, for example in widening children’s experiences:

“Mostly we’ve built links through the creative curriculum, inviting parents to read stories in

different languages... cooking demonstrations for the class... someone coming in playing the

guitar. “

Deputy, first school

This adaptation of the curriculum was seen to help build these cultural links and help parents feel more

confident to work with the school to enhance children’s experiences. One example of this was related to

children learning about Eid:

“Things like celebrating Eid has put parents’ minds at rest, that we’re thinking about their

religion and their celebrations.”

Nursery manager, primary school

In this particular school, parents offered to bring in Eid clothes and other resources for the children to use

and learn about in the setting. This promoted a strong home‑school link and the school recognised that

encouraging parents to support the school in an area they were familiar with could lead to them to feel more

confident about attending other activities at school such as reading or maths workshops. As Hunt et al (2011)

recognise, this is important as parents new to English generally have low confidence compared with other

groups.

13 © National College for School Leadership

Another cultural barrier was the disparity between the school system previously experienced by either the

children and/or their parents (where this was in another country) and the school system which they now

found themselves part of. The differences could be marked and parents brought thoughts about their own

schooling with them.

Allied to this, school leaders recognised that in some cases, parents may have had a bad experience of

school and be concerned that their children might have a similar experience, or they may have had a more

formal experience of gaining early knowledge and skills either in this country or another. The introduction

of the EYFS and the focus on play was, it was viewed, likely to be very different from the parents’ own

experiences of school. Schools therefore needed to help parents understand, through the sessions held, the

teaching and learning strategies used. These provided opportunities to show what and how their children

were learning at school. This, it was considered, aided their confidence and ability to support their children in

the same way at home.

Workshops where parents learned alongside their children were found to be a powerful way of supporting

the parents:

“... sitting down with the parent and child saying ’Let’s show mummy how we do your

sounds, let’s show her how we do the book’, because then they watch you, what you do

with the child, and then that can help them support the child’s learning at home.”

Deputy head, first school

Sustainability

School leaders said they thought their programme for working with parents new to English was sustainable

though without exception they would like to do more. Establishing an environment where parents felt

included cost time and a shared vision, rather than money. To be effective it was recognised that this vision

needs to filter down from the headteacher and senior leaders, for example through training opportunities,

staff meetings and modelling interactions with parents.

“Engaging parents is so important that if it’s dependent on money it’s not going to work so

it’s got to be sustainable.”

Headteacher, first school

Those that referred to cost recognised that it is important to build in an amount each year to refresh the

diversity resources and plan for the parent workshops and home visits for example. All schools made

effective use of their diverse staff to translate for parents as necessary, though as identified, it was reliant on

current staffing and their language skills.

Different initiatives were identified as being led by different staff, for example home visits and pre-nursery

workshops were led by the Early Years co-ordinator while curriculum workshops may be led by literacy and

numeracy co-ordinators. It was recognised that all staff leading initiatives need to be supported by the

headteacher and senior leadership team in order for sessions to be planned into the school diary for the year

to manage how staff are released. Some schools had used external agencies such as local authority advisers

to support the development of diversity resources.

Effective leadership characteristics

“I don’t know if it’s leadership qualities or if it’s professional characteristics.”

Headteacher, first school

Many of the respondents provided a list of leadership characteristics that they saw as important in engaging

with parents to impact positively on the HLE. School leaders recognised that they needed to have certain

personal qualities that influenced their professional characteristics, for example those mentioned included

honest, calm, patient, empathetic and reassuring.

14 © National College for School Leadership

Leaders also mentioned characteristics that related primarily to ethos and communication as set out below.

These characteristics underpinned the work they did in this area.

Ethos

—— Being respectful of families and their cultures, showing that they were valued.

“Although it’s different, it’s equally valuable.”

Headteacher, primary school

Leaders at different levels recognised the importance of valuing links with parents and taking the time to

build events that demonstrated this into the school diary.

—— Being proactive and motivated to reach out for opportunities that demonstrated to parents that they

were doing something extra and had a passion for their child to achieve their best.

It was recognised that it was not easy to achieve an effective partnership with parents that impacts

on the HLE, though all schools in this project were committed to trying to achieve the reality. They

recognised the need to commit time and energy and to continue providing opportunities for parents to

engage in their children’s learning even when initially they had a small number of attendees at sessions.

Some schools found strategies that helped increase the number, for example by texting reminders or

making personal contact by phone.

—— Being child and family-centred.

This included not making assumptions about parents’ prior knowledge but working from parents’ and

children’s starting points. Being flexible and responsive in adapting provision was viewed as important as

all parents had different needs.

—— Able to create inclusive, welcoming, friendly, open Foundation Stage settings which parents felt confident

to enter.

“In our Ofsted report, one of the parents said, the school’s like their family... and it’s that

relationship you build with parents that they trust you, feel part of the school and that the

atmosphere in the school is one that encourages them to step in.”

Headteacher, primary school

Communication

“We have a lot of training focused on communication and working with parents. I think that

gives the school a real community feeling, a real cohesion.”

SENCO, primary school

—— Being good listeners and communicators, who were accessible and made time to talk.

Modelling these behaviours and skills was also seen as important so that it gave clear messages to staff

and helped embed these qualities. Modelling interactions with parents took place at different levels of

leadership and this was felt to be filtering down to all staff to help provide a consistent school approach.

Leaders needed effective listening skills in order to identify and address any issues and start from where

the parents were to find the best way to build links and support them in helping their children at home.

“It’s not about them listening to us, it’s about us listening to them.”

Assistant head, first school

15 © National College for School Leadership

“[The head]... is very open to new things, new cultures, and that’s [why] when I was

applying for this job I felt comfortable and valued and I think that’s what she conveys

in terms of when she’s speaking to parents, that she shows she’s interested, no matter

who the person is or where they came from and I think that’s a great asset to have as a

manager.”

Reception teacher, first school

“Always being able to talk... ‘Don’t leave your child at the door, if you have a problem please

come in’. ... even if it’s a smile, I think if a leader can do that the parents feel more at ease

because they don’t feel intimidated.”

Nursery manager, primary school

16 © National College for School Leadership

Conclusions

In summary, schools involved in this research have valued and prioritised building links with parents which

support children’s learning and have the potential to impact positively upon the child’s home learning

environment.

It was recognised that there are challenges facing schools working with parents new to English, for example

overcoming language barriers and cultural differences. However the initiatives used to engage parents

in their children’s learning were largely the same as those used for other parents. It was highlighted that

parents new to English may need additional support such as interpreters to access these initiatives and

understand the education system, as well as support to see the value of using their first language at home

to help their child’s learning in school. School leaders in this research made the most of available resources

and planned initiatives into the school year so that resources such as time and budget were managed

effectively in order to achieve a sustainable programme for parents.

Based on the findings, it could be proposed that there are three phases that encourage successful

partnerships with parents and that impact on the HLE, particularly for families new to English:

—— Phase 1 begins before the children start school. As Drake (2009) recognises, mothers and fathers are

normally open to new learning during transition stages in their lives (in this case their child starting

nursery or pre-school), and practitioners should consider how they can best use this short window of

opportunity. By working closely with parents before their child starts nursery, moves to Key Stage 1, Key

Stage 2 or secondary school, effective partnerships could be created that subsequently impact positively

on the HLE.

—— Phase 2 centres on using a range of informal strategies to encourage parents and help them feel

confident in coming into school. Attendance of informal activities not focused on learning, such as

watching children’s performances, was shown to have a valuable purpose. Parents who are particularly

anxious about attending formal school events can be encouraged through informal activities which allow

staff to build positive relationships with parents and increase their confidence to attend, for example,

curriculum workshops.

“It’s about being tuned into what parents might be feeling or thinking, the ability to

empathise and it’s about intuition and getting your timing right.”

Headteacher, first school

—— Phase 3 concentrates on activities that assist parents in supporting their children’s learning at home. It

should be acknowledged that comments made by school leaders involved in this research suggest that

without phase 2, it would be very difficult for schools to work with parents to support the HLE effectively.

If parents do not feel confident to enter school and discuss their concerns or views with teachers,

they are unlikely to attend sessions focused on supporting their children’s learning. Working with

parents new to English brings with it a greater challenge of finding ways of listening to their views and

communicating concepts in an accessible way.

As Hunt et al (2011) acknowledge, 97 per cent of parents who were present at events tried activities at

home, suggesting that attending an event is very effective in influencing the HLE. Therefore it is important

to find ways of successfully encouraging parents to attend sessions focused on supporting children with their

learning.

All these initiatives take time and energy and without perseverance may not find the same success. The

ethos of the school and leadership skills of the headteacher, leadership team and other staff are vital.

Personal characteristics were considered to be the key to developing a successful working relationship with

parents allied to identification of their needs and feelings to establish the best way to work with them and

their children.

17 © National College for School Leadership

Roberts (2010) acknowledges that when parents are treated as partners and feel respected and valued,

they are more likely to listen to the information and advice they are given. A school environment where

parents are valued and their views are heard has been shown to build a strong link with parents and in turn

influence the HLE as parents take ideas home to support their children’s learning.

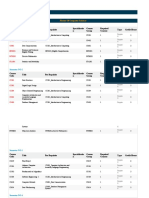

It is hoped that this study offers school leaders engaged in promoting and developing the HLE of parents

new to English strategies they might use and reflection points on which they might draw to consider their

own practice. To aid this, a flowchart of key considerations is offered in Figure 1. This might be used by a

senior leadership team to consider current practice and further development opportunities.

18 © National College for School Leadership

Phase 1: Pre admission to school

EAL support

Pre-nursery sessions EAL support

Home visits

Parent visit round Visiting in summer term Induction Translator

Support in

school Parent pre-school before starting in meeting support -

completing

interviews September other parents,

admissions pack

member of staff

Phase 2: Getting parents in - informal activities

EAL support

Welcoming

school / Stay and play Parents bringing EAL support

Parent visitors

Being able to sessions Watching Parent in resources

Trips Fetes eg demonstrate Access to

listen / performances volunteers from their

Coffee morning guitar translators

Contact with

culture for

key worker

display

Phase 3: Initiatives focused on children’s learning = impact on HLE

Children taking Parents attend

EAL support

Informal chat books home to adult education

Parents attend EAL support

at the end of show parents courses Diversity EAL support

curriculum resources Access to

workshop Parents Children’s ESOL courses

workshops including dual translators

sessions commenting on centre

language books

children’s work activities

19 © National College for School Leadership

References

Allen, G, 2011, Early Intervention: The next steps – An Independent Report to Her Majesty’s Government,

London, Cabinet Office. Available at: www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/early-intevention-next-steps.pdf [Accessed 28

December 2011]

Blackledge, A & Aljazir, J, 1996, Developing home-school literacy partnerships in minority language families.

In J Mills (ed), Partnership in the Primary School. Working in Collaboration, London, Routledge

Campbell, C, 2011, How to involve hard-to-reach parents: encouraging meaningful parental involvement

with school, Nottingham, National College for School Leadership. Available at: www.nationalcollege.org.uk/

docinfo?id=156367&filename=how-to-involve-hard-to-reach-parents-full-report.pdf [Accessed 7 December

2011]

Coelho, E, 1994, Social integration of immigrant and refugee children. In F Genesee (ed), Educating Second

Language Children: the whole child, the whole curriculum, the whole community, pp301-327, Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press

Desforges, C & Abouchaar, A, 2003, The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family

Education on Pupil Achievement and Adjustment: A Literature Review, London, Department for Education and

Skills

Drake, J, 2009, Planning for Children’s Play and Learning: Meeting children’s needs in the later stages of the

EYFS, (3rd ed), London, Routledge

Field, F, 2010, The Foundation Years: Preventing poor children becoming poor adults – The report of the

Independent Review on Poverty and Life Chances, London, Cabinet Office. Available at: http://webarchive.

nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110120090128/http://povertyreview.independent.gov.uk/media/20254/poverty-

report.pdf [Accessed 28 December 2011]

Glenn, A, Cousins, J & Helps, A, 2006, Tried and Tested Strategies: Ready to Read and Write in the Early Years,

London, David Fulton Publishers

Harris, A, & Goodall, J, 2007, Engaging Parents in Raising Achievement: Do parents know they matter? A

research project commissioned by the Specialist Schools and Academies Trust, London, Department for

Children, Schools and Families. Available at: www.education.gov.uk/publications/standard/publicationDetail/

Page1/DCSF-RBW004 [Accessed 3 April 2012]

Hunt, S, Virgo, S, Klett-Davies, M, Page, A & Apps, J, 2011, Provider influence on the home learning

environment, London, Department for Education. Available at: www.education.gov.uk/publications/standard/

publicationDetail/Page1/DFE-RR142 [Accessed 19 January 2012]

Melhuish, E, 2010, Why children, parents and home learning are important. In K Sylva et al (eds), Early

Childhood Matters: Evidence from the Effective Pre-school and Primary Education Project, pp44‑69, Abingdon,

Routledge

Roberts, K, 2009, Early Home Learning Matters: A brief guide for practitioners, London, Family and Parenting

Institute

Roberts, K, 2010, Supporting parents in helping their children learn at home: Some tips for childcare

providers, London, Day Care Trust. Available at: www.daycaretrust.org.uk/data/files/Projects/London_project/

Home_learning_web_content_-_FINAL_RH_v2_formatted_9.9.10.pdf [Accessed 22 January 2012]

Sylva, K, Melhuish, E, Sammons, P, Siraj-Blatchford, I & Taggart, B (eds), 2010, Early Childhood Matters:

Evidence from the Effective Pre-school and Primary Education Project, Abingdon, Routledge

20 © National College for School Leadership

Tickell, C, 2011, The Early Years: Foundations for life, health and learning, np, np. Available at: http://media.

education.gov.uk/MediaFiles/B/1/5/%7BB15EFF0D-A4DF-4294-93A1-1E1B88C13F68%7DTickell%20review.

pdf [Accessed 28 December 2011]

Virani-Roper, Z, 2000, Bilingual learners and numeracy. In M Gravelle (ed), Planning for bilingual learners,

pp65‑78, Stoke-on-Trent, Trentham Books

Waldman, J, Bergeron, C, Morris, M, O’Donnell, L, Benefield, P, Harper, A & Sharp, C, 2008, Improving

children’s attainment through a better quality of family-based support for early learning. London, Centre for

Excellence and Outcomes in Children and Young People’s Services (C4EO). Available at: www.c4eo.org.uk/

themes/earlyyears/familybasedsupport/files/c4eo_family_based_support_scoping_study.pdf [Accessed 3

April 2012]

Ward, U, 2009, Working with Parents in Early Years Settings, Exeter, Learning Matters Ltd

21 © National College for School Leadership

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the schools who took part in this research, with particular recognition to the headteachers and

other staff who gave up their valuable time to be interviewed.

Visit www.nationalcollege.org.uk/publications to access other full research and summary reports.

22 © National College for School Leadership

The National College exists to develop ©2012 National College for School Leadership –

and support great leaders of schools All rights reserved. No part of this document may

be reproduced without prior permission from the

and children’s centres – whatever their National College. To reuse this material, please contact

context or phase. the Membership Team at the National College or

email college.publications@nationalcollege.gsi.gov.uk.

• Enabling leaders to work together

to lead improvement

• Helping to identify and develop

the next generation of leaders

• Improving the quality of leadership

so that every child has the best

opportunity to succeed

Membership of the National College

gives access to unrivalled development

and networking opportunities, professional

support and leadership resources.

Triumph Road

Nottingham NG8 1DH

T 0845 609 0009

F 0115 872 2001

E college.enquiries@nationalcollege.gsi.gov.uk We care about the environment

www.education.gov.uk/nationalcollege We are always looking for ways to minimise

our environmental impact. We only print where

necessary, which is why you will find most

An executive agency of the

PB1018

of our materials online. When we do print

Department for Education we use environmentally friendly paper.

You might also like

- Families and Educators Together: Building Great Relationships that Support Young ChildrenFrom EverandFamilies and Educators Together: Building Great Relationships that Support Young ChildrenNo ratings yet

- The African Imagination in Music. by Kofi AgawuDocument6 pagesThe African Imagination in Music. by Kofi AgawuchicodosaxNo ratings yet

- Security Studies A ReaderDocument462 pagesSecurity Studies A ReaderAtha Fawwaz100% (4)

- Chapter IiDocument9 pagesChapter IiKimberly LactaotaoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document5 pagesChapter 6Aeron Rai Roque100% (5)

- Parental Involvement - Final (Repaired)Document24 pagesParental Involvement - Final (Repaired)Jonel Mark Manlangit Rabe100% (2)

- Bob Proctor The StickpersonDocument9 pagesBob Proctor The Stickpersondanadamsfx100% (9)

- Technology Innovation As A Conversion ProcessDocument16 pagesTechnology Innovation As A Conversion ProcessNagendra GadamSetty Venkata100% (1)

- 2018 FinnishDocument17 pages2018 FinnishGrace ChowNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Effects of Family Involvement On ChildrensDocument91 pagesA Study On The Effects of Family Involvement On ChildrensvudgufugNo ratings yet

- Parents' Involvement in Children'S English Language LearningDocument21 pagesParents' Involvement in Children'S English Language LearningAchaDiyahNo ratings yet

- Parental Care and Academic PerformanceDocument75 pagesParental Care and Academic PerformanceGaniyu MosesNo ratings yet

- Parental Involvement Exploring Its InfluenceDocument14 pagesParental Involvement Exploring Its InfluenceJericho MartinezNo ratings yet

- Parental Involvement and Their Impact On Reading English of Students Among The Rural School in MalaysiaDocument8 pagesParental Involvement and Their Impact On Reading English of Students Among The Rural School in MalaysiaM-Hazmir HamzahNo ratings yet

- Situation Analysis "When Parents Become Involved, Children Do Better in School, and They Go ToDocument30 pagesSituation Analysis "When Parents Become Involved, Children Do Better in School, and They Go ToSylvia EstoestaNo ratings yet

- Seminar On The Role of Parental StatusDocument35 pagesSeminar On The Role of Parental StatusMentorNo ratings yet

- Degree of Parental Involvement in ChildrenDocument13 pagesDegree of Parental Involvement in ChildrenKen Mitchell MoralesNo ratings yet

- The Home Learning Environment and Its Role in Shaping Children's Educational DevelopmentDocument7 pagesThe Home Learning Environment and Its Role in Shaping Children's Educational DevelopmentdhfNo ratings yet

- Definition of Parental InvolvementDocument12 pagesDefinition of Parental InvolvementJeng Arao Bauson100% (1)

- KABUHIDocument39 pagesKABUHIJhoi Enriquez Colas PalomoNo ratings yet

- 2021 Compare Finland and Turkey - TeacherDocument32 pages2021 Compare Finland and Turkey - TeacherGrace ChowNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Lit - Innovation ProposalDocument7 pagesReview of Related Lit - Innovation ProposalEthyl Mae Alagos-VillamorNo ratings yet

- Maryhope Proposal NewDocument32 pagesMaryhope Proposal Newmaryhope williamNo ratings yet

- Kadewole G&C Parental Involvement On Child Behaviour ProjDocument35 pagesKadewole G&C Parental Involvement On Child Behaviour ProjOmobomi SmartNo ratings yet

- Homework in Primary School: Could It Be Made More Child-Friendly?Document22 pagesHomework in Primary School: Could It Be Made More Child-Friendly?lingleyNo ratings yet

- Thesis Final Jai Jen 2Document23 pagesThesis Final Jai Jen 2kris dotillosNo ratings yet

- THESIS-final-JAI-JEN 2Document25 pagesTHESIS-final-JAI-JEN 2Krizna Dingding DotillosNo ratings yet

- KABUHIDocument27 pagesKABUHIJhoi Enriquez Colas PalomoNo ratings yet

- What Are The Ways That Social Class Structure in Jamaica May Influence A Child's Learning Capabilities and Academic Experience?Document4 pagesWhat Are The Ways That Social Class Structure in Jamaica May Influence A Child's Learning Capabilities and Academic Experience?Nicole FarquharsonNo ratings yet

- Parent PresentationDocument16 pagesParent Presentationapi-268213710No ratings yet

- Guada Chap 2Document10 pagesGuada Chap 2Jasper Kurt Albuya VirginiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter II - RRLDocument4 pagesChapter II - RRLCassandra LucheNo ratings yet

- Action ResearchDocument20 pagesAction ResearchANALIZA MAGMANLACNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework SamnordanjoshDocument9 pagesTheoretical Framework SamnordanjoshSerLem WellNo ratings yet

- Inquiry Brief FinalDocument2 pagesInquiry Brief Finalapi-242817193No ratings yet

- Dissertation ParentsDocument98 pagesDissertation ParentsTealongoNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument12 pagesResearchanime.kyokaNo ratings yet

- Renan ThesisDocument13 pagesRenan ThesisNico AbenojaNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesLiterature ReviewCeilo AttongNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Family Involvement To Students: Balanza, M. N., & Dadal, E. MDocument6 pagesThe Impact of Family Involvement To Students: Balanza, M. N., & Dadal, E. MVeronica DadalNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument7 pagesArticleDorinaLorenaNo ratings yet

- Family Background As A Predictor of Lagos State Students Chap1-3 CorrectionDocument35 pagesFamily Background As A Predictor of Lagos State Students Chap1-3 CorrectionotenaikeNo ratings yet

- Thesis ProposalDocument12 pagesThesis ProposalMarjorie Grace AlfanteNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Research 2 HUMSS-3Document6 pagesQuantitative Research 2 HUMSS-3Sensu MiriamNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Parental Involvement in Education and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis StudyDocument17 pagesThe Relationship Between Parental Involvement in Education and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis StudyChauncey Mae Tan AcsonNo ratings yet

- Research ManuscriptDocument15 pagesResearch Manuscriptjohncuyas5No ratings yet

- EJ1268016Document6 pagesEJ1268016Jamer PelotinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document15 pagesChapter 1Denmark Simbajon MacalisangNo ratings yet

- Group 3 CH.1 5 1Document43 pagesGroup 3 CH.1 5 1Jasey Jeian CompocNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document5 pagesChapter 2Abigail SopenaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1-Background of The StudyDocument2 pagesCHAPTER 1-Background of The StudylynkimjoanNo ratings yet

- Childrens Early Home Learning Environment and Learning Outcomes in The Early Years of SchoolDocument19 pagesChildrens Early Home Learning Environment and Learning Outcomes in The Early Years of SchoolAngela WeaslyNo ratings yet

- Done With Project11Document87 pagesDone With Project11joysteven88No ratings yet

- The Effects of Parental Education and Family IncomeDocument13 pagesThe Effects of Parental Education and Family IncomeChris JavierNo ratings yet

- 2022 Under 4yrs Malaysian (Lousy Journal)Document8 pages2022 Under 4yrs Malaysian (Lousy Journal)Grace ChowNo ratings yet

- Group 7 Revised Chapter 1 2Document30 pagesGroup 7 Revised Chapter 1 2Maria lourdes romaNo ratings yet

- Research'19 Grade 12Document31 pagesResearch'19 Grade 12Nica BASANALNo ratings yet

- God Bless ThesisDocument34 pagesGod Bless ThesisjinecaNo ratings yet

- Educação FísicaDocument16 pagesEducação FísicaFilipeNo ratings yet

- Influence of Learning Environmmenton Student'S Academic Performance in Rombo DistrictDocument10 pagesInfluence of Learning Environmmenton Student'S Academic Performance in Rombo DistrictHilary MmangaNo ratings yet

- Involving Parents in the Common Core State Standards: Through a Family School Partnership ProgramFrom EverandInvolving Parents in the Common Core State Standards: Through a Family School Partnership ProgramNo ratings yet

- Effective Homework Strategies: Instruction, Just Do It, #2From EverandEffective Homework Strategies: Instruction, Just Do It, #2No ratings yet

- The Early Years Communication Handbook: A practical guide to creating a communication friendly settingFrom EverandThe Early Years Communication Handbook: A practical guide to creating a communication friendly settingNo ratings yet

- What Does it Mean to be One?: A Practical Guide to Child Development in the Early Years Foundation StageFrom EverandWhat Does it Mean to be One?: A Practical Guide to Child Development in the Early Years Foundation StageRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Become An IB Accredited SchoolDocument12 pagesBecome An IB Accredited SchoolDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- 2looking After Teacher WellbeingDocument7 pages2looking After Teacher WellbeingDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Self Evaluation Background Principles Key LearningDocument56 pagesSelf Evaluation Background Principles Key LearningDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Self Evaluation A Reflection and Planning GuideDocument32 pagesSelf Evaluation A Reflection and Planning GuideDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Intro - Excellent Education - 12 Simple StepsDocument36 pagesIntro - Excellent Education - 12 Simple StepsDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Creating A Culture of Coaching Summary ReportDocument5 pagesCreating A Culture of Coaching Summary ReportDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Self Evaluation Models Tools PracticeDocument40 pagesSelf Evaluation Models Tools PracticeDuncan Rose0% (1)

- Teacher Development and ESL in The ClassroomDocument4 pagesTeacher Development and ESL in The ClassroomDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Measurement Driven InstructionDocument5 pagesMeasurement Driven InstructionDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Middle Leadership Roles in Secondary Schools SummaryDocument6 pagesRethinking Middle Leadership Roles in Secondary Schools SummaryDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Performance-Based Pedagogy Assessment of Teacher CandidatesDocument58 pagesPerformance-Based Pedagogy Assessment of Teacher CandidatesDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- NAISCOASchoolsDocument60 pagesNAISCOASchoolsDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Preparing Mainstream Teachers To Support English Language LearnersDocument54 pagesPreparing Mainstream Teachers To Support English Language LearnersDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- 003 Positive Behaviour Support Planning Part 3Document20 pages003 Positive Behaviour Support Planning Part 3Duncan Rose100% (1)

- 12 Ways To Support English Learners in The Mainstream Classroom - Cult of PedagogyDocument11 pages12 Ways To Support English Learners in The Mainstream Classroom - Cult of PedagogyDuncan RoseNo ratings yet

- EAL Toolkit V1Document54 pagesEAL Toolkit V1Duncan RoseNo ratings yet

- Snapshot Chapter 5 Mother's DayDocument7 pagesSnapshot Chapter 5 Mother's Dayprateekm698No ratings yet

- M3-Lecture 20211212-MCI - SOKODocument24 pagesM3-Lecture 20211212-MCI - SOKOJohnny VuNo ratings yet

- ISO9001 21001 Correlation MatricesDocument3 pagesISO9001 21001 Correlation MatricesSerenada MardelinaNo ratings yet

- 1 Personality Disorder Seminar CGRDocument61 pages1 Personality Disorder Seminar CGRgautambobNo ratings yet

- Section 1: Questions 1-10Document7 pagesSection 1: Questions 1-10Phone Myat Pyaye SoneNo ratings yet

- ReceiptDocument1 pageReceiptRajat YewaleNo ratings yet

- Stroop Effect TestDocument8 pagesStroop Effect TestSehaj BediNo ratings yet

- Use of English 01ADocument2 pagesUse of English 01AТетяна СтрашноваNo ratings yet

- Study SchemeDocument3 pagesStudy SchemeMuhammad AzamNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer Aiml ProjectDocument25 pagesBreast Cancer Aiml Project2203a52222No ratings yet

- Directorate of Technical Education, Maharashtra State, MumbaiDocument73 pagesDirectorate of Technical Education, Maharashtra State, MumbaiAvinash JadhavNo ratings yet

- Conversation Are You Good atDocument11 pagesConversation Are You Good atAleksandra DjokicNo ratings yet

- IdiomaticityDocument85 pagesIdiomaticityIrina Bicescu100% (1)

- A 7-Level Single DC Source Cascaded H-Bridge Multilevel Inverter Control Using Hibrid ModulationDocument6 pagesA 7-Level Single DC Source Cascaded H-Bridge Multilevel Inverter Control Using Hibrid ModulationYeisson MuñozNo ratings yet

- Alternative Assessment Show and TellDocument5 pagesAlternative Assessment Show and Tellapi-360932035No ratings yet

- Ramanathan, N The Concept of Śrutijāti-S, Journal of The Music Academy, Madras 1980. Vol - LI, No.1, pp.99-112Document10 pagesRamanathan, N The Concept of Śrutijāti-S, Journal of The Music Academy, Madras 1980. Vol - LI, No.1, pp.99-112telugutalliNo ratings yet

- 7 11 Year Old ObservationDocument4 pages7 11 Year Old Observationbrobro1212100% (1)

- Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivational Orientations and The Volunteer ProcessDocument6 pagesIntrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivational Orientations and The Volunteer ProcessClaudia BNo ratings yet

- Final Exam Exemption PolicyDocument11 pagesFinal Exam Exemption Policyapi-296374857No ratings yet

- Proverbs PDFDocument41 pagesProverbs PDFGiyatmi Jimmy100% (1)

- Chapter 4 and 5 TomecwaDocument19 pagesChapter 4 and 5 TomecwaDick Jefferson Ocampo PatingNo ratings yet

- 2013 PHD Webster Thomas PDFDocument229 pages2013 PHD Webster Thomas PDFLiudmyla HarmashNo ratings yet

- Tugas MPI Randy PrayudaDocument28 pagesTugas MPI Randy PrayudaK'putra RachmadNo ratings yet

- Research On The Article "DOLE Urged To Address Job-Skills Mismatch" by Vanne Ellaine Terrazola and Answer These QuestionsDocument2 pagesResearch On The Article "DOLE Urged To Address Job-Skills Mismatch" by Vanne Ellaine Terrazola and Answer These QuestionsMarouf TugaNo ratings yet

- An Integrated Rectangular Dielectric Resonator AntennaDocument4 pagesAn Integrated Rectangular Dielectric Resonator AntennaThiripurasundari DNo ratings yet

- Professional Management ResumeDocument8 pagesProfessional Management Resumee7dhewgp100% (1)