Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 viewsMasteral Report

Masteral Report

Uploaded by

Cathlyn MerinoThis document discusses how to develop a researchable topic from a personal interest. It explains that a research topic must be precisely defined, focused on a specific subject, and approached from the perspective of an academic discipline. A researchable topic answers not just the researcher's own questions, but addresses what the broader academic community needs to know. Developing a solid research topic is key to accessing literature relevant to the topic of study.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Semi-Detailed LP ScienceDocument3 pagesSemi-Detailed LP ScienceCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge English - Advanced Practice Test ADocument21 pagesCambridge English - Advanced Practice Test ANoel Kl100% (1)

- Grammar of Poetry Sample Student TextDocument25 pagesGrammar of Poetry Sample Student TextcompasscinemaNo ratings yet

- Speakout Grammar Extra Upper Intermediate Unit 9Document2 pagesSpeakout Grammar Extra Upper Intermediate Unit 9xacobeo100% (2)

- BMW Inpa English User Guide PDFDocument74 pagesBMW Inpa English User Guide PDFTimSmithNo ratings yet

- Claudius of TurinDocument11 pagesClaudius of Turinrobin_gui94No ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 Week 4Document19 pagesPractical Research 2 Week 4Jackqueline FernandoNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument20 pagesResearch Methodologymahamed said HoggaamoNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Good ResearchDocument72 pagesCharacteristics of Good ResearchNanette A. Marañon-SansanoNo ratings yet

- Pr2 Module 5 ReflectionDocument1 pagePr2 Module 5 ReflectionFrancine Arielle BernalesNo ratings yet

- Writing The First ChapterDocument23 pagesWriting The First ChapterJasmineNo ratings yet

- Shank y Brown - Cap2Document8 pagesShank y Brown - Cap2buhlteufelNo ratings yet

- What Is A Research ProblemDocument5 pagesWhat Is A Research ProblemArsyilia NabilaNo ratings yet

- Rift Valley University: Individual AssignmentDocument4 pagesRift Valley University: Individual AssignmentAbdela Aman MtechNo ratings yet

- Rift Valley University: Individual AssignmentDocument4 pagesRift Valley University: Individual AssignmentAbdela Aman MtechNo ratings yet

- English q1 by EhtishamDocument7 pagesEnglish q1 by EhtishamSana KhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2, The Research ProcessDocument32 pagesChapter 2, The Research Processshayma shymazNo ratings yet

- Research ConceptDocument4 pagesResearch ConceptCath BabaylanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2Document9 pagesLecture 2ClarkJimrex AlejoNo ratings yet

- Orca Share Media1678427750928 7039836229431171401 PDFDocument16 pagesOrca Share Media1678427750928 7039836229431171401 PDFZarylle De AsasNo ratings yet

- Organizing Academic Research PapersDocument4 pagesOrganizing Academic Research PapersAloc MavicNo ratings yet

- Crafting Research QuestionsDocument4 pagesCrafting Research QuestionsrovingarcherNo ratings yet

- Module II in IC FR 200Document20 pagesModule II in IC FR 200Jonalyn RogandoNo ratings yet

- Reserch Problem FormulationDocument3 pagesReserch Problem Formulationamul65No ratings yet

- Researchchap 2Document10 pagesResearchchap 2NATHANIEL VILLAMORNo ratings yet

- Identifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemDocument38 pagesIdentifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemRitchie Jane Brion100% (1)

- Defining Research Problem and Hypothesis FormulationDocument31 pagesDefining Research Problem and Hypothesis FormulationBrook AddisuNo ratings yet

- Las Pr1 11 Melc 4 Week 2Document16 pagesLas Pr1 11 Melc 4 Week 2Roland Andrey TeñosoNo ratings yet

- 3IS Q3 Modules 2 - 0228Document18 pages3IS Q3 Modules 2 - 0228Joanna Marielle DaderoNo ratings yet

- The Research ProblemDocument6 pagesThe Research ProblemJanina Kirsten DevezaNo ratings yet

- Brown Scrapbook Art and History Museum Presentation - 20230928 - 125458 - 0000Document15 pagesBrown Scrapbook Art and History Museum Presentation - 20230928 - 125458 - 0000yusra.ocheaNo ratings yet

- Liboon, John Rey ADocument3 pagesLiboon, John Rey AJohn Rey LiboonNo ratings yet

- A Reflection: What Makes A Good Research Question?Document3 pagesA Reflection: What Makes A Good Research Question?Franz Wendell BalagbisNo ratings yet

- What Is Research GAPDocument5 pagesWhat Is Research GAPAdeel Manzar100% (1)

- Sources of Problems For Investigation: What Makes A Good Research Statement?Document3 pagesSources of Problems For Investigation: What Makes A Good Research Statement?Darlen Daileg SantianezNo ratings yet

- Unit Four An Overview of The Research Process Unit ContentsDocument30 pagesUnit Four An Overview of The Research Process Unit ContentsbashaNo ratings yet

- Rift Valley University: Individual AssignmentDocument4 pagesRift Valley University: Individual AssignmentAbdela Aman MtechNo ratings yet

- I. Be Ready To Elucidate Different Concepts: 1. From Research Problem To Relationships To Research DesignsDocument7 pagesI. Be Ready To Elucidate Different Concepts: 1. From Research Problem To Relationships To Research DesignsCharlie Maine TorresNo ratings yet

- PR1 - Mod1 Week 18Document4 pagesPR1 - Mod1 Week 18Antonette CastilloNo ratings yet

- PR1 Chapter 3Document55 pagesPR1 Chapter 3Harry Lord M. BolinaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework EditorialDocument5 pagesTheoretical Framework EditorialNoman ShahzadNo ratings yet

- Nota Kepentingan EQDocument6 pagesNota Kepentingan EQJennifer CaseyNo ratings yet

- WA0004.encDocument15 pagesWA0004.encBest HappyNo ratings yet

- Method of Research (Lecture)Document11 pagesMethod of Research (Lecture)John Russell MoralesNo ratings yet

- Research Questions For Literature Reviews: Why A Literature Review?Document4 pagesResearch Questions For Literature Reviews: Why A Literature Review?Heidi OhNo ratings yet

- Educ 113 Lesson 4Document32 pagesEduc 113 Lesson 4John Mark LazaroNo ratings yet

- Developing Research QuestionsDocument13 pagesDeveloping Research QuestionsHayes Vivar100% (1)

- Topic 3 Research QuestionDocument4 pagesTopic 3 Research QuestionKris IgnacioNo ratings yet

- The Research ProblemDocument12 pagesThe Research ProblemhithereNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Identify Research Gaps and Generate Research QuestionsDocument4 pagesApproaches To Identify Research Gaps and Generate Research QuestionsFritz RemigioNo ratings yet

- Week 5 - Chapter 1Document67 pagesWeek 5 - Chapter 1Maria Laarnie D. MoriNo ratings yet

- Module 2 1Document36 pagesModule 2 1Cielo DiosanaNo ratings yet

- Week 28 Practical Research 1 G11Document6 pagesWeek 28 Practical Research 1 G11Jac Polido100% (2)

- Research ProblemDocument7 pagesResearch ProblemNehaNo ratings yet

- Background of Research: LessonDocument8 pagesBackground of Research: LessonSher-Anne Fernandez - BelmoroNo ratings yet

- 88-Article Text-159-1-10-20210603Document27 pages88-Article Text-159-1-10-20210603Arif AhmadNo ratings yet

- Research HypothesisDocument7 pagesResearch HypothesisSherwin Jay BentazarNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Research Proposal Contents of Research Proposal Styles of Referencing and ParaphrasingDocument44 pagesMeaning of Research Proposal Contents of Research Proposal Styles of Referencing and ParaphrasingbashaNo ratings yet

- Week 3 and 4 Topic, Research Problems, RQ and Types of ResearchDocument46 pagesWeek 3 and 4 Topic, Research Problems, RQ and Types of ResearchharyaniNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Pol ResearcDocument31 pagesIntroduction To Pol Researcf.kpobi1473No ratings yet

- Lesson 5 Stating Research QuestionsDocument20 pagesLesson 5 Stating Research QuestionsChelsea FloresNo ratings yet

- MahaDocument5 pagesMahaHoorain MahamNo ratings yet

- Research 2: First Quarter - Week 5 and 6Document20 pagesResearch 2: First Quarter - Week 5 and 6Rutchel100% (2)

- Research Main Aspects: Usama Bin Iqbal Lecture # 4 Qualitative Research TechniquesDocument41 pagesResearch Main Aspects: Usama Bin Iqbal Lecture # 4 Qualitative Research TechniquesFaisal RazaNo ratings yet

- Machi The Literature Review 2e ch1Document23 pagesMachi The Literature Review 2e ch1heddadi.nourelhoudaNo ratings yet

- Kra Cover 2Document18 pagesKra Cover 2Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- MANCOM AttendanceDocument1 pageMANCOM AttendanceCathlyn Merino100% (1)

- Numeracy Test Key Stage 2Document1 pageNumeracy Test Key Stage 2Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Kra CoverDocument7 pagesKra CoverCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Explicit LP ScienceDocument6 pagesExplicit LP ScienceCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Plans and Goals 2022: Generation UprisingDocument4 pagesPlans and Goals 2022: Generation UprisingCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

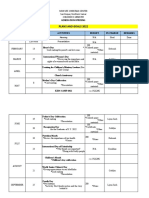

- CM Teaching LoadDocument3 pagesCM Teaching LoadCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Assessment Results TemplateDocument2 pagesAssessment Results TemplateCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Answer Sheets CheclistDocument2 pagesAnswer Sheets CheclistCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Environmental QuizDocument11 pagesEnvironmental QuizCathlyn Merino100% (1)

- Application LetterDocument1 pageApplication LetterCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Recognition: Juan Dela CruzDocument1 pageCertificate of Recognition: Juan Dela CruzCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Techo QuizDocument2 pagesTecho QuizCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- 4Document13 pages4Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Format of The Case Analysis IDocument1 pageFormat of The Case Analysis ICathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- 2 BBDocument8 pages2 BBCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Phil. PresidentsDocument19 pagesPhil. PresidentsCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Seminar MasteralDocument9 pagesSeminar MasteralCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- 3Document7 pages3Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- English 5Document2 pagesEnglish 5Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- NECRODocument3 pagesNECROCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument23 pagesResearch ProposalCathlyn Merino100% (1)

- Research ActivityDocument6 pagesResearch ActivityCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Exercitii Recapitulative Present PerfectDocument2 pagesExercitii Recapitulative Present PerfectCami CerneanuNo ratings yet

- Aditya Ajit Patil 42: III Ai&DsDocument38 pagesAditya Ajit Patil 42: III Ai&DsMaithili PatilNo ratings yet

- ESL Lesson - How + Adjectives/adverbsDocument10 pagesESL Lesson - How + Adjectives/adverbsferlgoulartNo ratings yet

- Statistics For Economics Formula Sheet.Document38 pagesStatistics For Economics Formula Sheet.VivekNo ratings yet

- Timun MasDocument2 pagesTimun Masyayatkentucky12345No ratings yet

- English Syllabus JNTU H & K & ADocument12 pagesEnglish Syllabus JNTU H & K & AD. Krishna MohanNo ratings yet

- Joshi C M, Vyas Y - Extensions of Certain Classical Integrals of Erdélyi For Gauss Hypergeometric Functions - J. Comput. and Appl. Mat. 160 (2003) 125-138Document14 pagesJoshi C M, Vyas Y - Extensions of Certain Classical Integrals of Erdélyi For Gauss Hypergeometric Functions - J. Comput. and Appl. Mat. 160 (2003) 125-138Renee BravoNo ratings yet

- Ceviche en InglesDocument3 pagesCeviche en InglesNAYC100% (1)

- Test Headway Upperinter Unit2-3Document3 pagesTest Headway Upperinter Unit2-3saktyviesNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Manopavicāra in Vasubandhu's Exposition of Pratītyasamutpāda in Chapter Three of The Abhidharmakośabhā YaDocument19 pagesThe Concept of Manopavicāra in Vasubandhu's Exposition of Pratītyasamutpāda in Chapter Three of The Abhidharmakośabhā Ya张晓亮No ratings yet

- 2210 Y15 SP 1Document14 pages2210 Y15 SP 1Rana Hassan TariqNo ratings yet

- Cannibalistic PerspectivesDocument13 pagesCannibalistic PerspectivesSandra ManuelsdóttirNo ratings yet

- Bacon Prose Style by Tahoor AbidDocument4 pagesBacon Prose Style by Tahoor AbidRaheela Khan100% (1)

- ST0602 5Document7 pagesST0602 5gigajohnNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 - Hermeneutical PhenomenologyDocument2 pagesLesson 6 - Hermeneutical PhenomenologyAgatha Guevan PunzalNo ratings yet

- June Jane Placides Lesson 19Document13 pagesJune Jane Placides Lesson 19June Jane Placides100% (1)

- Synectics SeligmannDocument19 pagesSynectics SeligmannCroco latoz100% (1)

- Azure Application GatewayDocument574 pagesAzure Application GatewayJonnathan De La Barra100% (1)

- AIX Intro To System Administration Course OutlineDocument5 pagesAIX Intro To System Administration Course OutlineMangesh AbnaveNo ratings yet

- The Origin of Surabaya: East JavaDocument4 pagesThe Origin of Surabaya: East JavaIndah Resty AgustyaNo ratings yet

- Syntax Head Movement SlidesDocument49 pagesSyntax Head Movement Slideszainaemad32No ratings yet

- PragmaticsDocument7 pagesPragmaticsLakanak BungulNo ratings yet

- Poetry Essays With PoemsDocument50 pagesPoetry Essays With PoemsLynn Hollenbeck BreindelNo ratings yet

- List of MS-DOS CommandsDocument48 pagesList of MS-DOS CommandskarthikNo ratings yet

- MIT6 006F11 Lec08 PDFDocument7 pagesMIT6 006F11 Lec08 PDFwhatthefuNo ratings yet

Masteral Report

Masteral Report

Uploaded by

Cathlyn Merino0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views2 pagesThis document discusses how to develop a researchable topic from a personal interest. It explains that a research topic must be precisely defined, focused on a specific subject, and approached from the perspective of an academic discipline. A researchable topic answers not just the researcher's own questions, but addresses what the broader academic community needs to know. Developing a solid research topic is key to accessing literature relevant to the topic of study.

Original Description:

masteral report

Original Title

masteral report

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses how to develop a researchable topic from a personal interest. It explains that a research topic must be precisely defined, focused on a specific subject, and approached from the perspective of an academic discipline. A researchable topic answers not just the researcher's own questions, but addresses what the broader academic community needs to know. Developing a solid research topic is key to accessing literature relevant to the topic of study.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views2 pagesMasteral Report

Masteral Report

Uploaded by

Cathlyn MerinoThis document discusses how to develop a researchable topic from a personal interest. It explains that a research topic must be precisely defined, focused on a specific subject, and approached from the perspective of an academic discipline. A researchable topic answers not just the researcher's own questions, but addresses what the broader academic community needs to know. Developing a solid research topic is key to accessing literature relevant to the topic of study.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 2

Curiosity is the heart of all research.

The origin of most research interests stems from the conflicts,

issues, concerns, or beliefs encountered in daily work. We question, why specific facets of work succeed

while others fail, why some strategies or tactics succeed more than others, or why people think, learn, and

act in certain ways. Examples from the workplace that can stimulate research are: What causes the conflict

among members of committee work groups? How accurate are standardized test scores in measuring

individual student achievement?

Leaders trying to improve organizations seek ways to develop better programs, to improve working

relationships, and to motivate people to complete specific tasks. They might ask, for example, what is the

recipe for creating successful change? Is having a forceful leader a precondition for a successful group?

How does the principal guide the teaching staff to improve student performance? Does success come from

“telling it like it is”? Each of these questions can initiate the need to seek answers from others, to do

research or study.

Examine this idea called research interest. Notice in the preceding examples that the interest is

framed in two ways. First, it names a curiosity or a concern about some subject, and second, it identifies the

subject itself. Curiosity provides the “why” for the work being considered. The topic provides the “what” of

the research, the subject to be studied. Defining and clarifying this “what” of the research allows the

researcher to identify it in the literature. Curiosity provides the personal energy necessary to pursue the

interest.

Three transformations must take place before a personal everyday interest can evolve into a

researchable topic for formal study. The first transformation creates specificity of topic. When asked to

select a research interest, most beginning researchers will answer with a global response, such as, “I am

interested in why students are not achieving.” The problem with this response lies in its lack of specificity.

Given this statement as presented, could a researcher see and measure the concern? Of course not. The

interest, as expressed, is too broad. A more detailed definition of the subject under study is needed. A

researchable interest must be precisely stated. An example of a personal interest is, “How does the weather

change from season to season?” A researchable interest might be, “To what degree is March weather in

coastal northern California influenced by an Arctic airflow?” Which of these two interests would be easier to

research—the general or the specific?

The second transformation must focus the topic. Is the interest chosen too broad, or does this interest

contain multiple subjects for study? By focusing on precision and clarity, you focus the interest. You must

choose one subject to study, one that can be examined clearly. You must set clear boundaries. Consider this

example of focusing a topic. Instead of “I am interested in why students are not achieving,” try, “What effect

does understand specific academic language have on achievement in the natural sciences for third-grade

Hispanic second-language learners?”

The third transformation is one of perspective. The personal interest comes from an individual’s need

to know more about a specific subject. A researchable interest emerges from the vantage point of an

academic discipline. The interest is no longer a question of “what I need to know,” but transforms into a

question of, “What do those in this academic field know about the subject, and what do they need to know?”

The research comes from that academic field’s scholarly writings and the questions posed in academic

conversation and debate about that subject. Formal research must be approached using the vantage point of a

specific discipline such as sociology or psychology. Selecting an academic discipline provides a direct

avenue to the specific knowledge about the topic.

A personal concern must also be a concern for the larger academic community. A viable research

interest must address the academic field’s need to know and must be a question for the entire academic

community to consider. Does your curiosity, your need to know about something, mean that the academic

community has that same need? Framing a solid research interest is key to accessing a topic that is

researchable in the literature.

A research topic is more than simply the main idea of a paper. The topic provides the entry point to

the literature, decides the boundary of the literature review, identifies the subject of research, and determines

the strategy necessary to answer the research question.

These transformations require three tasks: (1) choosing a personal interest, (2) refining that interest,

and (3) using the research interest to identify a specific research preliminary topic.

You might also like

- Semi-Detailed LP ScienceDocument3 pagesSemi-Detailed LP ScienceCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge English - Advanced Practice Test ADocument21 pagesCambridge English - Advanced Practice Test ANoel Kl100% (1)

- Grammar of Poetry Sample Student TextDocument25 pagesGrammar of Poetry Sample Student TextcompasscinemaNo ratings yet

- Speakout Grammar Extra Upper Intermediate Unit 9Document2 pagesSpeakout Grammar Extra Upper Intermediate Unit 9xacobeo100% (2)

- BMW Inpa English User Guide PDFDocument74 pagesBMW Inpa English User Guide PDFTimSmithNo ratings yet

- Claudius of TurinDocument11 pagesClaudius of Turinrobin_gui94No ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 Week 4Document19 pagesPractical Research 2 Week 4Jackqueline FernandoNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument20 pagesResearch Methodologymahamed said HoggaamoNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Good ResearchDocument72 pagesCharacteristics of Good ResearchNanette A. Marañon-SansanoNo ratings yet

- Pr2 Module 5 ReflectionDocument1 pagePr2 Module 5 ReflectionFrancine Arielle BernalesNo ratings yet

- Writing The First ChapterDocument23 pagesWriting The First ChapterJasmineNo ratings yet

- Shank y Brown - Cap2Document8 pagesShank y Brown - Cap2buhlteufelNo ratings yet

- What Is A Research ProblemDocument5 pagesWhat Is A Research ProblemArsyilia NabilaNo ratings yet

- Rift Valley University: Individual AssignmentDocument4 pagesRift Valley University: Individual AssignmentAbdela Aman MtechNo ratings yet

- Rift Valley University: Individual AssignmentDocument4 pagesRift Valley University: Individual AssignmentAbdela Aman MtechNo ratings yet

- English q1 by EhtishamDocument7 pagesEnglish q1 by EhtishamSana KhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2, The Research ProcessDocument32 pagesChapter 2, The Research Processshayma shymazNo ratings yet

- Research ConceptDocument4 pagesResearch ConceptCath BabaylanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2Document9 pagesLecture 2ClarkJimrex AlejoNo ratings yet

- Orca Share Media1678427750928 7039836229431171401 PDFDocument16 pagesOrca Share Media1678427750928 7039836229431171401 PDFZarylle De AsasNo ratings yet

- Organizing Academic Research PapersDocument4 pagesOrganizing Academic Research PapersAloc MavicNo ratings yet

- Crafting Research QuestionsDocument4 pagesCrafting Research QuestionsrovingarcherNo ratings yet

- Module II in IC FR 200Document20 pagesModule II in IC FR 200Jonalyn RogandoNo ratings yet

- Reserch Problem FormulationDocument3 pagesReserch Problem Formulationamul65No ratings yet

- Researchchap 2Document10 pagesResearchchap 2NATHANIEL VILLAMORNo ratings yet

- Identifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemDocument38 pagesIdentifying The Inquiry and Stating The ProblemRitchie Jane Brion100% (1)

- Defining Research Problem and Hypothesis FormulationDocument31 pagesDefining Research Problem and Hypothesis FormulationBrook AddisuNo ratings yet

- Las Pr1 11 Melc 4 Week 2Document16 pagesLas Pr1 11 Melc 4 Week 2Roland Andrey TeñosoNo ratings yet

- 3IS Q3 Modules 2 - 0228Document18 pages3IS Q3 Modules 2 - 0228Joanna Marielle DaderoNo ratings yet

- The Research ProblemDocument6 pagesThe Research ProblemJanina Kirsten DevezaNo ratings yet

- Brown Scrapbook Art and History Museum Presentation - 20230928 - 125458 - 0000Document15 pagesBrown Scrapbook Art and History Museum Presentation - 20230928 - 125458 - 0000yusra.ocheaNo ratings yet

- Liboon, John Rey ADocument3 pagesLiboon, John Rey AJohn Rey LiboonNo ratings yet

- A Reflection: What Makes A Good Research Question?Document3 pagesA Reflection: What Makes A Good Research Question?Franz Wendell BalagbisNo ratings yet

- What Is Research GAPDocument5 pagesWhat Is Research GAPAdeel Manzar100% (1)

- Sources of Problems For Investigation: What Makes A Good Research Statement?Document3 pagesSources of Problems For Investigation: What Makes A Good Research Statement?Darlen Daileg SantianezNo ratings yet

- Unit Four An Overview of The Research Process Unit ContentsDocument30 pagesUnit Four An Overview of The Research Process Unit ContentsbashaNo ratings yet

- Rift Valley University: Individual AssignmentDocument4 pagesRift Valley University: Individual AssignmentAbdela Aman MtechNo ratings yet

- I. Be Ready To Elucidate Different Concepts: 1. From Research Problem To Relationships To Research DesignsDocument7 pagesI. Be Ready To Elucidate Different Concepts: 1. From Research Problem To Relationships To Research DesignsCharlie Maine TorresNo ratings yet

- PR1 - Mod1 Week 18Document4 pagesPR1 - Mod1 Week 18Antonette CastilloNo ratings yet

- PR1 Chapter 3Document55 pagesPR1 Chapter 3Harry Lord M. BolinaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework EditorialDocument5 pagesTheoretical Framework EditorialNoman ShahzadNo ratings yet

- Nota Kepentingan EQDocument6 pagesNota Kepentingan EQJennifer CaseyNo ratings yet

- WA0004.encDocument15 pagesWA0004.encBest HappyNo ratings yet

- Method of Research (Lecture)Document11 pagesMethod of Research (Lecture)John Russell MoralesNo ratings yet

- Research Questions For Literature Reviews: Why A Literature Review?Document4 pagesResearch Questions For Literature Reviews: Why A Literature Review?Heidi OhNo ratings yet

- Educ 113 Lesson 4Document32 pagesEduc 113 Lesson 4John Mark LazaroNo ratings yet

- Developing Research QuestionsDocument13 pagesDeveloping Research QuestionsHayes Vivar100% (1)

- Topic 3 Research QuestionDocument4 pagesTopic 3 Research QuestionKris IgnacioNo ratings yet

- The Research ProblemDocument12 pagesThe Research ProblemhithereNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Identify Research Gaps and Generate Research QuestionsDocument4 pagesApproaches To Identify Research Gaps and Generate Research QuestionsFritz RemigioNo ratings yet

- Week 5 - Chapter 1Document67 pagesWeek 5 - Chapter 1Maria Laarnie D. MoriNo ratings yet

- Module 2 1Document36 pagesModule 2 1Cielo DiosanaNo ratings yet

- Week 28 Practical Research 1 G11Document6 pagesWeek 28 Practical Research 1 G11Jac Polido100% (2)

- Research ProblemDocument7 pagesResearch ProblemNehaNo ratings yet

- Background of Research: LessonDocument8 pagesBackground of Research: LessonSher-Anne Fernandez - BelmoroNo ratings yet

- 88-Article Text-159-1-10-20210603Document27 pages88-Article Text-159-1-10-20210603Arif AhmadNo ratings yet

- Research HypothesisDocument7 pagesResearch HypothesisSherwin Jay BentazarNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Research Proposal Contents of Research Proposal Styles of Referencing and ParaphrasingDocument44 pagesMeaning of Research Proposal Contents of Research Proposal Styles of Referencing and ParaphrasingbashaNo ratings yet

- Week 3 and 4 Topic, Research Problems, RQ and Types of ResearchDocument46 pagesWeek 3 and 4 Topic, Research Problems, RQ and Types of ResearchharyaniNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Pol ResearcDocument31 pagesIntroduction To Pol Researcf.kpobi1473No ratings yet

- Lesson 5 Stating Research QuestionsDocument20 pagesLesson 5 Stating Research QuestionsChelsea FloresNo ratings yet

- MahaDocument5 pagesMahaHoorain MahamNo ratings yet

- Research 2: First Quarter - Week 5 and 6Document20 pagesResearch 2: First Quarter - Week 5 and 6Rutchel100% (2)

- Research Main Aspects: Usama Bin Iqbal Lecture # 4 Qualitative Research TechniquesDocument41 pagesResearch Main Aspects: Usama Bin Iqbal Lecture # 4 Qualitative Research TechniquesFaisal RazaNo ratings yet

- Machi The Literature Review 2e ch1Document23 pagesMachi The Literature Review 2e ch1heddadi.nourelhoudaNo ratings yet

- Kra Cover 2Document18 pagesKra Cover 2Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- MANCOM AttendanceDocument1 pageMANCOM AttendanceCathlyn Merino100% (1)

- Numeracy Test Key Stage 2Document1 pageNumeracy Test Key Stage 2Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Kra CoverDocument7 pagesKra CoverCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Explicit LP ScienceDocument6 pagesExplicit LP ScienceCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Plans and Goals 2022: Generation UprisingDocument4 pagesPlans and Goals 2022: Generation UprisingCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- CM Teaching LoadDocument3 pagesCM Teaching LoadCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Assessment Results TemplateDocument2 pagesAssessment Results TemplateCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Answer Sheets CheclistDocument2 pagesAnswer Sheets CheclistCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Environmental QuizDocument11 pagesEnvironmental QuizCathlyn Merino100% (1)

- Application LetterDocument1 pageApplication LetterCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Recognition: Juan Dela CruzDocument1 pageCertificate of Recognition: Juan Dela CruzCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Techo QuizDocument2 pagesTecho QuizCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- 4Document13 pages4Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Format of The Case Analysis IDocument1 pageFormat of The Case Analysis ICathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- 2 BBDocument8 pages2 BBCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Phil. PresidentsDocument19 pagesPhil. PresidentsCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Seminar MasteralDocument9 pagesSeminar MasteralCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- 3Document7 pages3Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- English 5Document2 pagesEnglish 5Cathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- NECRODocument3 pagesNECROCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument23 pagesResearch ProposalCathlyn Merino100% (1)

- Research ActivityDocument6 pagesResearch ActivityCathlyn MerinoNo ratings yet

- Exercitii Recapitulative Present PerfectDocument2 pagesExercitii Recapitulative Present PerfectCami CerneanuNo ratings yet

- Aditya Ajit Patil 42: III Ai&DsDocument38 pagesAditya Ajit Patil 42: III Ai&DsMaithili PatilNo ratings yet

- ESL Lesson - How + Adjectives/adverbsDocument10 pagesESL Lesson - How + Adjectives/adverbsferlgoulartNo ratings yet

- Statistics For Economics Formula Sheet.Document38 pagesStatistics For Economics Formula Sheet.VivekNo ratings yet

- Timun MasDocument2 pagesTimun Masyayatkentucky12345No ratings yet

- English Syllabus JNTU H & K & ADocument12 pagesEnglish Syllabus JNTU H & K & AD. Krishna MohanNo ratings yet

- Joshi C M, Vyas Y - Extensions of Certain Classical Integrals of Erdélyi For Gauss Hypergeometric Functions - J. Comput. and Appl. Mat. 160 (2003) 125-138Document14 pagesJoshi C M, Vyas Y - Extensions of Certain Classical Integrals of Erdélyi For Gauss Hypergeometric Functions - J. Comput. and Appl. Mat. 160 (2003) 125-138Renee BravoNo ratings yet

- Ceviche en InglesDocument3 pagesCeviche en InglesNAYC100% (1)

- Test Headway Upperinter Unit2-3Document3 pagesTest Headway Upperinter Unit2-3saktyviesNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Manopavicāra in Vasubandhu's Exposition of Pratītyasamutpāda in Chapter Three of The Abhidharmakośabhā YaDocument19 pagesThe Concept of Manopavicāra in Vasubandhu's Exposition of Pratītyasamutpāda in Chapter Three of The Abhidharmakośabhā Ya张晓亮No ratings yet

- 2210 Y15 SP 1Document14 pages2210 Y15 SP 1Rana Hassan TariqNo ratings yet

- Cannibalistic PerspectivesDocument13 pagesCannibalistic PerspectivesSandra ManuelsdóttirNo ratings yet

- Bacon Prose Style by Tahoor AbidDocument4 pagesBacon Prose Style by Tahoor AbidRaheela Khan100% (1)

- ST0602 5Document7 pagesST0602 5gigajohnNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 - Hermeneutical PhenomenologyDocument2 pagesLesson 6 - Hermeneutical PhenomenologyAgatha Guevan PunzalNo ratings yet

- June Jane Placides Lesson 19Document13 pagesJune Jane Placides Lesson 19June Jane Placides100% (1)

- Synectics SeligmannDocument19 pagesSynectics SeligmannCroco latoz100% (1)

- Azure Application GatewayDocument574 pagesAzure Application GatewayJonnathan De La Barra100% (1)

- AIX Intro To System Administration Course OutlineDocument5 pagesAIX Intro To System Administration Course OutlineMangesh AbnaveNo ratings yet

- The Origin of Surabaya: East JavaDocument4 pagesThe Origin of Surabaya: East JavaIndah Resty AgustyaNo ratings yet

- Syntax Head Movement SlidesDocument49 pagesSyntax Head Movement Slideszainaemad32No ratings yet

- PragmaticsDocument7 pagesPragmaticsLakanak BungulNo ratings yet

- Poetry Essays With PoemsDocument50 pagesPoetry Essays With PoemsLynn Hollenbeck BreindelNo ratings yet

- List of MS-DOS CommandsDocument48 pagesList of MS-DOS CommandskarthikNo ratings yet

- MIT6 006F11 Lec08 PDFDocument7 pagesMIT6 006F11 Lec08 PDFwhatthefuNo ratings yet