Professional Documents

Culture Documents

4博物馆作为一种学习

4博物馆作为一种学习

Uploaded by

波唐Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

4博物馆作为一种学习

4博物馆作为一种学习

Uploaded by

波唐Copyright:

Available Formats

18 INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA IN AMERICAN MUSEUMS

twined, coupled with the heterogeneity of the museum audience, makes satisfying each

visitor a formidable task. Instead of attempting to meet the needs and wants of every visitor

in every exhibit, many designers agree that museums should try to identify the possible mo-

tives of the visitor and then do their best to design either separate or integrated exhibits

that satisfy each of those motives (Hudson, 1977; Miles et al., 1988; Interviews: The Austin

Children's Museum, 1992; The Exploratorium, 1992).

Two other important, fairly generic audience characteristics include the fact that most

visitors come to museums in groups or at least couples, and that the average time spent at

an exhibit ranges from 5 seconds to two minutes (Lee, 1968; Lewis, 1991; Melton, cited in

& m a l h m , 1987a; Interviews: Aborescence, 1992;The Exploratorium, 1992; Min-

neapolis Institute of Art, 1992). Since visiting museums tends to be a social experience,

several study participants felt that exhibits should attempt to accommodate more than one

person. And with an average attention span of 45 seconds to one minute per exhibit, the

design must be attractive and immediately intuitive to capture a passerby (Lee, 1968). Each

of these factors carry implications regarding the design of educational exhibits and the need

for an engaging presentation of the content.

The Museum as a Learning Environment

Understanding the educational approach used in museums requires an examination of

not only the visitor, but of the learning setting. Traditional learning environments, i.e.,

schools, are often contrasted to museums by describing the former as formal education, and

the latter as informal education (Bitgood, 1988; Gardner, 1991a; Shettel, 1991; Vance &

Schroeder, 1991). Lee (1968) describes the difference as "learning-from-the-environment"

versus the formal "teaching-learning" process used in schools (p. 373). Although both set-

tings are alike in that they aim to inform their audiences, the bottom line is that the

museum presents a completely different learning environment from the school. In

museums, visitors learn through direct interaction with objects and artifacts, and in the

schools, students are generally directed by teachers to absorb predetermined curricula from

textbooks. Understanding the similarities and differences between these two approaches to

learning helps to highlight the most effective ways to present information given the museum

environment.

A common goal of informal and formal educators is to communicate new information to

learners. It makes sense then, that exhibit designers often follow many of the information

presentation strategies and processes that have been proven by instructional design profes-

sionals in formal education contexts. For example, exhibit designers normally define objec-

tives, identify the target audience, identify program resources, design by the objectives,

implement, and revise exhibits as necessary - processes advocated by many instructional

designers (Dick & Carey, 1990; Mager, 1988; Miles et al., 1988). The success of systematic

instructional design processes in schools and corporate training departments has validated

their use as an instructional framework, and many museum professionals also recognize the

value of these techniques. Exhibit designers, however, tend to vary their "instructional

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

I. THE MUSEUM CONTEXT 19

design" practices to accommodate the informal learning characteristics of their environ-

ment by, for example, not mandating that the visitor practice or be tested on the informa-

tion communicated (Dick & Carey, 1990; Mager, 1988; Miles et al., 1988; Schneider, 1992;

Wilson, 1992a; Interview: The (Boston) Computer Museum, 1992).

Along with the similarities in goals and instructional design steps advocated come some

very significant differences which make the instructional design process used in schools in-

appropriate for museums. Brown, Screven, Koran, and Beer (cited in Bitgood, 1988) are a

few of the museum evaluators who have identified the key differences between informal

and formal learning. They recognize that informal learning practices do not presume to sys-

tematically teach the measurable knowledge that formal academic learning does, and in-

stead rely on a "discovery-based learning approach. Discovery-based or experiential

learning is a self-paced educational approach where the goal is to present the learner with a

body of information and then allow that person to explore and discover the information in

which he or she is interested.

Stephen Bitgood of the Center for Social Design (1988) suggests seven areas in which

formal and informal learning differ: instructional stimuli; characteristics of the environ-

ment; responses elicited from learners; social interactions; consequences of the learning ex-

perience; instructional objectives; and the target audience. Understanding the differences

between informal and formal education in these seven areas can not only help designers cre-

ate educational exhibits for the museum audience, but they can also help identify the uni-

que successes of well designed exhibits to reveal how learning can be made more effective

in any environment. Some of these differences within the seven areas defined by Bitgood

and supported by findings of other researchers include the following:

The first key difference Bitgood (1988) mentions is that formal

education generally uses verbal information to teach, while the informal museum setting

uses visual information and is increasingly moving toward multi-sensory stimuli. Formal

education typically provides abstract exposure to information, while informal education

provides direct and hands-on experiences (Bitgood, 1988; Harte, 1989). Formal education

requires extended exposure to information which leads to better retention, while informal

education normally consists of short exposures, although repeated visits can increase reten-

tion.

. - Another difference is that the environment of the classroom

is fairly unchanging, whereas that of the museum is more dynamic, possibly distracting. In-

terest level may remain high in the dynamic environment, but retention for the same

reasons is expected to be lower. Unfamiliarity with the informal environment requires the

learner to circulate to get exposure to the instructional stimuli in the exhibits. Classrooms,

in which students are generally seated and familiar with the surroundings do not encourage

this exploration.

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

20 INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA IN AMERICAN MUSEUMS

ed f r o m Behavior in formal education is largely teacher-paced

with great importance placed on achievement, whereas in museums the pace is normally

determined by the visitorllearner and achievement is personal and self-motivated. These

differences lead to intrinsic rewards in museums, while in schools, the rewards are more

public and contrived (Bitgood, 1988; Gardner, 1991a).

. .

SocialUnlike most formal environments, socializing is accepted and en-

couraged in informal museum settings. Since most visitors come to museums in groups,

learning is treated as a social or family event. Formal school settings on the other hand,

have hierarchical structures and educational content which often limit social interactions.

Conseauences Formal education practices use reward and punishment

strategies to motivate students (e.g., grades, teacher and parent approval/disapproval, accep-

tance to college). Informal environments do not threaten the visitor with negative conse-

quences. Instead, they encourage intrinsic rewards with fun and casual activities. The

attitude towards, and implications of learning are much more positive (Harte, 1989). How-

ever, a possible negative effect due to the lack of supervision and direction in museums may

be that the learner is misinformed (Bitgood, 1988).

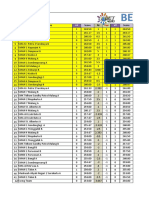

Exhibit 2

Summary of the Differences Between Informal

and Formal Learning Environments

Schools Museums

Instructional Stimuli verbal 8 visual; abstract; visual 8 multlsensory;

extended exposure direct exposurelhands-on;

short duration

Learning Environment unchanging; famlllar;

Responses Eliclted teacher-paced; performance- self-paced; self-motivated

based:

Social Interactions limited; individual focus acceptedlencouraged;

group focus

Learning Consequences reward or punishment Intrinsic rewards; low

supervision

Instructional Objectives quantitative; facts 8 knowledge; experiential; affective;

performance standards observation evaluations

Audience Characteristics categorized diverse

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

I. THE MUSEUM CONTEXT 21

. .

Instructional.Formal education demands learning specific concepts and facts,

which are mostly quantitative and cognitive activities. When textbook or course evaluations

are conducted in formal education, there is little leeway in what is considered appropriate

or adequate information and performance. The objectives of museum education are more

experiential and affective. In informal learning, evaluations tend to focus on the quality of

the experience, not on the quantity or retention of facts.

. .

Audience Finally, Bitgood notes the difference in the audiences: formal

learning categorizes learners, usually by age or aptitude, whereas informal learning is open

to any learner, potentially creating a much more diverse audience.

While many of the differences mentioned are broad generalizations, and while some of

these differences are decreasing as schools initiate changes to improve learning and

museums offer more classes and workshops, several researchers would probably still agree

with the characteristics listed by Bitgood (Chenoweth, 1990; Gardner, 1991a; Harte, 1989;

McCarthy, 1989; Wilson, 1987 & 1987). Maton-Howarth (1990) adds that secondary educa-

tion is not primarily concerned with, nor designed to develop life skills and values (e.g., in-

dividuality, creativity, sensitivity, perception), but does efficiently impart factual knowledge

that meets the needs of society (pp. 183-184). Museums, on the other hand, are equipped

to offer meaningful, life-oriented education through interactive and experiential learning,

and therefore, can potentially provide more effective learning experiences that better equip

individuals for everyday life (pp. 182-185).

Although the differences listed above may appear to praise informal education at the ex-

pense of formal education, Bitgood (1988) readily states that informal learning institutions

are not without their adverse consequences, namely the possibility of misinformation, the

boring quality of numerous similar objects in some exhibitions, long hours walking, and the

possibility of ill-designed instructional aids (e.g., tiny or poorly worded labels). Bitgood's

conclusion is not that informal institutions can replace formal institutions for learning, but

that the two should learn from each other and cooperate to accomplish their goals in har-

mony.

While most academic educators and museum exhibitors would agree that informal educa-

tion will never substitute for formal education, Gardner, a Harvard University researcher,

feels that schools should be made more like museums in order to foster true understanding

of concepts in the world around us (Gardner, 1991a). At least one example of a formal

educational program that is taking steps to combine the best of the classroom with the

science museum approach to presenting information is Project Science 2000 ("Science

2000," 1992). Science 2000 classrooms use teachers to lead discussions, and then move to

hands-on experiments and activities so that students can play the role of scientist, using real

scientific instruments to forecast the weather, for example. Gardner's hope is that more

schools will seriously study the strengths of museum programs that incorporate activity- and

discovery-based learning of valuable life issues, and determine how to incorporate those

qualities into traditional teaching methods (Gardner, 1991a).

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

22 INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA IN AMERICAN MUSEUMS

Zeller also feels museums offer significantly different learning from schools: "trying to

make the museum experience an extension of the classroom...over-shadows the unique

learning opportunities of the museum ...and makes the museum into a school rather than

emphasizing the characteristics that makes it a different and unique learning environment"

(Zeller, cited in Maton-Howarth, 1990, p. 187). Zeller, Gardner (1991a) and Bitgood

(1988) pose ideas that are on the minds of many educators and museum professionals.

Given the existing infrastructure and capabilities of museums, it seems only logical that

museums play a significant role in the effort to educate the public by expanding and

strengthening their informal educative role, and by working with formal education systems

,-( 1992; Gardner, 1991a; Harte, 1989; Healy, 1992; Shettel, 1991).

The NSF funding for science museum teacher training programs mentioned earlier is an ex-

ample of how a more closely woven relationship between museums and traditional educa-

tional channels can exist (Chenoweth, 1990).

A large part of the action taken in response to the issues of improving school and

museum education has been to increase the use of hands-on and participatory learning, and

to incorporate interactive technologies (e.g., videodiscs and computers) in both formal

education and museum exhibits (Abbe, 1992; Gable, 1992; Information T e c m , 1987;

Palmer, 1992; S p k U w u s , 1991; Interviews: International Business Machines, 1992;

California Museum of Science and Industry, 1992). Multimedia in particular, is having a sig-

nificant impact on the education and training communities because of its new and dynamic

approach to communicating information (Ambron & Hooper, 1990; Eiser, 1992; Helsel,

1990; Jostens.,1992; McCarthy, 1989; Perry, 1990; SDeclal F o c u s : ,

. 1991).

1991;v , With respect to learning, multimedia provides the op-

portunity to absorb information communicated through a number of media, where each

stimulus can act as a reinforcement of the same message. Cognitive research has shown

that presenting an image accompanied by text or sounds reinforces learning (McCarthy,

1989, p. 27). Perhaps most importantly, the multimedia experience can address different

learning styles - those who are more visual can access or concentrate on video or animations

as their source of information, those who are more comfortable understanding ideas

presented through text can choose to read, and so on.

Gardner (1991b) has identified seven human intelligences, that is, seven different modes

that all individuals use in varying degrees to understand the world. The tenets of multiple

intelligence (MI) theory are that individuals can use language, logical mathematical

analysis, spatial representation, musical thinking, and the use of the body to solve problems

and make meaning (p. 12). Gardner's conclusion is that some individuals learn more easily

through linguistic methods, others through spatial or mathematical means. This being the

case, multimedia technologies afford personalized learning systems that can work for

anyone. And being able to accommodate these different learner preferences and abilities

provides a very rich and thorough educational interaction (McCarthy, 1989; Mintz, 1992;

Foe-, 1991; @xdFocus: Trainmg,1991; Wilson, 1987).

Another benefit of interactive multimedia relevant to the museum context is that learn-

ing is transformed from a passive, read the book or listen to the lecture approach, to a much

more active, learner-paced and discovery-based educational experience (Miles et al., 1988,

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

I. THE MUSEUM CONTEXT 23

p. 95; McCarthy, 1989; Interviews: Merrill-SALT, 1992; IBM, 1992). Not only does multi-

media empower individuals by giving them greater control over their learning, but the

development of easy to use programming tools have made it possible for the learner to cre-

ate his or her own multimedia presentations. This potential has already begun to revamp

the idea behind a "term paper," as shown in schools which are allowing kids to create and

deliver multimedia presentations on computers instead of paper (McCarthy, 1989; Wilson,

1991). Students are also developing higher-order problem solving skills, cooperation, and

group communication skills; the latter two representing interesting side affects from the in-

ability to fund more than one computer per three to four students (McCarthy, 1989; Wilson,

1991). Other benefits include the ability to customize programs for different grades and

achievement levels, to record and store multiple languages in a single program, and to track

student progress. In training, interactive technologies have been praised for reducing costs

and improving retention (Guglielmo, 1992; SDecial Focus: w, 1991, p. 80). Finally,

the technological capabilities of the magnetic and optical media in these systems provide

reliable, high quality storage of massive amounts of information.

Many schools which have implemented multimedia technology have seen extremely posi-

tive results in the form of improved motivation, retention, learning speed, self-esteem, and

interest in learning - some of the most common and devastating reasons why education

seems to be failing today (Davey, 1991; McCarthy, 1989; Perry, 1990;

m, 1991; Wilson, 1987; Interviews: Bank Street College of Education, 1992; Texas Learn-

ing Technology Group, 1992). Given the fact that people generally remember 25 percent of

what they see, 40 percent of what they see and hear, and 75 percent of what they hear, see,

and do, the logic of involving students in interactive multisensory learning opportunities is

clear (Multimedia : UD close, 1991, p. 10). Two specific examples of successful educational

multimedia projects include the Texas Learning Technology Group (TLTG) and Bank

Street College initiatives, which have very successfully focused on using multimedia technol-

ogy with a discovery-based learning approach in an effort to make school learning more en-

gaging and relevant to students.

TLTG is a partnership of 13 Texas school districts, the National Science Foundation, and

the Texas Association of School Boards, formed to develop high school applications in

science and math using advanced technologies. TLTG's first project, a complete physical

science curriculum built around 460 hours of instruction on 15 videodiscs and accompany-

ing resource guides, has proven to be a great success. The seventeen states now using the

"Introduction to Physical Science" program have reported failure rates in physical science at

under 5%, a figure that becomes astonishing when made aware of the nationwide 50%

failure rate for physical science courses not using this program (Interviews: TLTG, 1992;

Society for Applied Learning Technology [SALT], Bozman, MD, 1992).

Similarly impressive results have been found through research done by the Center for

Technology in Education at the Bank Street College of Education. Interactive Nova:

Animal Pathfinders, a prototype program using Hypercard to control a videodisc player was

used along with two other prototype videodiscs, National Geographic's Whales and Bank

Street College's The Voyage of the Mimi, to study the nature and value of using interactive

multimedia in the classroom. After six weeks in a fifth-grade classroom, these multimedia

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

24 INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA IN AMERICAN MUSEUMS

tools were being used by the children for games, research, and most significantly, for the

creation of individual and collaborative presentations and interactive multimedia reports

(Wilson, 1991).

The Society for Applied Learning Technology (SALT) has tracked over a hundred other

schools and training centers that have implemented multimedia technology and reported

higher grade point averages, faster and greater retention of content, and other improve-

ments that speak in terms of advancing grade-levels, increased attendance and decreased

drop-out rates. Merrill(1992) has also tracked corporate training departments which have

reported similarly positive results from the use of interactive multimedia programs, includ-

ing reductions in training time of over 40% (Interview: SALT, Bozman, MD, 1992).

So how do all these benefits translate to the museum environment? Granted, the in-

depth educational applications developed for schools and other training programs would

hardly be necessary or appropriate in the generally short-lived and informal museum visit.

Nonetheless, interactive multimedia technology offers the opportunity to present a large

amount of information in a small space, and can make use of our instinctively powerful sen-

ses of sight, hearing, and touch. Two experts and an independent exhibit designer inter-

viewed for this study stated that they felt the positive results of multimedia in education

could transfer to the museum environment, that is, museums could use the successes of in-

teractive multimedia in education as an important corollary and reason to use multimedia

in museums. Unfortunately, these experts also agreed that the majority of museums do not

know about the research that has been conducted on multimedia in education, just as many

museums apparently do not conduct enough of their own research into the costs, into what

technology is available, and into the experiences of other museums with technology in ex-

hibits.

The unique characteristics of an informal learning environment both place and alleviate

burdens on the museum exhibit designer who wishes to educate. Because visitors are more

likely to be distracted by competing exhibits and the social interactions allowed in

museums, exhibits need to be much more attractive and engaging than a textbook. The dif-

ferences in the skills and knowledge levels of the audience also make the design process

much more complicated. On the other hand, because the objectives of museum education

are often not to impart concrete educational content, but are often qualitative and at-

titudinal in nature, the attention to the rigors of presenting objectives, practice and testing

are not necessary. Consequently, except for some museums that present the objectives up

front, the instructional design principles of presenting objectives, practice, and testing are

generally not used in museum exhibits (Bitgood, 1988; Miles et al., 1988; Interview: The

Austin Children's Museum, 1992). Instead, edutainment strategies which combine atten-

tion grabbing techniques with opportunities to learn based on individual motives and inter-

ests, dominate exhibit designs.

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

You might also like

- Cgfns-Profile Entry Instructions PDFDocument11 pagesCgfns-Profile Entry Instructions PDFMosab AfanahNo ratings yet

- Key Theories of Educational Psychology-Cristine AbudeDocument10 pagesKey Theories of Educational Psychology-Cristine AbudeRoessi Mae Abude AratNo ratings yet

- Integrative Teaching StrategiesDocument21 pagesIntegrative Teaching StrategiesGan Zi Xi64% (14)

- Task 3 Part D - Evaluation CriteriaDocument6 pagesTask 3 Part D - Evaluation Criteriaapi-2422915320% (1)

- VRLab 2-Balancing Act - Remote LabDocument9 pagesVRLab 2-Balancing Act - Remote LabMaria Cortes0% (1)

- 5.1-Env Psych ChapDocument25 pages5.1-Env Psych ChapLawrence Stephen Troy FangoniloNo ratings yet

- Module 4 FLCTDocument6 pagesModule 4 FLCTJerico VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Authentic Learning For The 21st Century An OverviewDocument13 pagesAuthentic Learning For The 21st Century An OverviewMarcela GhiglioneNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis 2 Museum Trip To Enrich Environmental Awareness and EducationDocument3 pagesCase Analysis 2 Museum Trip To Enrich Environmental Awareness and EducationCharisma PastorNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Innovations in School Educat PDFDocument18 pagesPedagogical Innovations in School Educat PDFTaniyaNo ratings yet

- Constructivism and Constructivist in ICTDocument5 pagesConstructivism and Constructivist in ICTNurdianaNo ratings yet

- Reporter 3 Cpe104Document42 pagesReporter 3 Cpe104Cicilian GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Reviewer Ed7Document8 pagesReviewer Ed7Arlene BendañaNo ratings yet

- The Science Curriculum Framework: An Enrichment Activity: #What'Sexpectedofyou?Document6 pagesThe Science Curriculum Framework: An Enrichment Activity: #What'Sexpectedofyou?Justine Jerk BadanaNo ratings yet

- Action Research A Learning Tool That Engages ComplexityDocument10 pagesAction Research A Learning Tool That Engages Complexitylev69No ratings yet

- Psychologists Behind Educational Theories in K To 12 Science TeachingDocument9 pagesPsychologists Behind Educational Theories in K To 12 Science TeachingRenalyn ArgawanonNo ratings yet

- Socio CulturalDocument5 pagesSocio CulturalFretche MiñozaNo ratings yet

- Imagination and Authentic LearningDocument5 pagesImagination and Authentic LearningTimofte PetrutaNo ratings yet

- How Student Learn 4Document8 pagesHow Student Learn 4Ainun BadriahNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument10 pages1 PBÖzlem OktayNo ratings yet

- Group 2 - Dimension of Learner - Centered LearningDocument4 pagesGroup 2 - Dimension of Learner - Centered LearningGlecy CapinaNo ratings yet

- Ed 82-Facilitating Learning Midterm ExaminationDocument3 pagesEd 82-Facilitating Learning Midterm ExaminationMarc Augustine Bello SunicoNo ratings yet

- Constructivism As A Theory For Teaching and Learning: What Are The Principles of Constructivism?Document14 pagesConstructivism As A Theory For Teaching and Learning: What Are The Principles of Constructivism?Patrizzia Ann Rose OcbinaNo ratings yet

- Mascolo Beyond Teacher Centered and Student Centered LearningDocument25 pagesMascolo Beyond Teacher Centered and Student Centered LearningVioleta HanganNo ratings yet

- Integrating Constructivist PrinciplesDocument4 pagesIntegrating Constructivist PrinciplesSheila ShamuganathanNo ratings yet

- Edci 531 Final Paper - KorichDocument6 pagesEdci 531 Final Paper - Korichapi-297040270No ratings yet

- LEARNER-CENTERED THEORIES OF LEARNING by Trisha and RosaDocument29 pagesLEARNER-CENTERED THEORIES OF LEARNING by Trisha and RosaCARLO CORNEJO100% (1)

- Manginyog Thesis Manuscript 2024Document63 pagesManginyog Thesis Manuscript 2024Norhamin MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Barboza Bryan m5 Activity 1 2ced 3Document20 pagesBarboza Bryan m5 Activity 1 2ced 3Trisha Anne BataraNo ratings yet

- Lect3 (The Learning Process)Document8 pagesLect3 (The Learning Process)LUEL JAY VALMORESNo ratings yet

- Video BasedDocument36 pagesVideo BasedRhodz Rhodulf CapangpanganNo ratings yet

- Sir Augustine ReviewerDocument7 pagesSir Augustine Reviewerashlynkate.parrenasNo ratings yet

- Constructivism 1Document15 pagesConstructivism 1api-487087119No ratings yet

- Constructivism As A Theory For Teaching and LearningDocument6 pagesConstructivism As A Theory For Teaching and LearningYonael TesfayeNo ratings yet

- Blamires 1999Document6 pagesBlamires 1999junkblickNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Student Learning: A Comparison of Classroom and Accountability AssessmentDocument21 pagesFacilitating Student Learning: A Comparison of Classroom and Accountability AssessmentdannamelissaNo ratings yet

- Educational Technology in The Constructivist Learning EnvironmentDocument27 pagesEducational Technology in The Constructivist Learning EnvironmentLeila Janezza ParanaqueNo ratings yet

- Save Odysseus: An Escape Room As A Content Gamification Activity For Enhancing Collaboration and Resilience in The School ContextDocument16 pagesSave Odysseus: An Escape Room As A Content Gamification Activity For Enhancing Collaboration and Resilience in The School ContextKonstantinos MalafantisNo ratings yet

- Report - Unit 1 Topic 2Document6 pagesReport - Unit 1 Topic 2LanieNo ratings yet

- CrispaDocument30 pagesCrispaapi-2606703620% (1)

- Educ 4 ReviewerDocument11 pagesEduc 4 Reviewermariza.barbaNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Constructivist TheoriesDocument15 pagesModule 6 Constructivist TheoriesChristian Emil ReyesNo ratings yet

- Listening To The Crystal BallDocument23 pagesListening To The Crystal Ballapi-227888640No ratings yet

- Improving Low Retention Skills Through Play-Based Teaching ApproachDocument12 pagesImproving Low Retention Skills Through Play-Based Teaching ApproachBrianNo ratings yet

- From Andragogy To HeutagogyDocument8 pagesFrom Andragogy To HeutagogyNil FrançaNo ratings yet

- Exit Tickets Revised Cbar Proposal Ed 74a - Somido Taub VillarosaDocument20 pagesExit Tickets Revised Cbar Proposal Ed 74a - Somido Taub Villarosaapi-534778534No ratings yet

- Module in 105 Lesson 4Document12 pagesModule in 105 Lesson 4johnleorosas03No ratings yet

- An Approach of Constructivist Learning in Instructional PracticeDocument5 pagesAn Approach of Constructivist Learning in Instructional PracticeDiana DengNo ratings yet

- Gee - 36 Learning PrinciplesDocument4 pagesGee - 36 Learning PrinciplesPatrícia MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Module - Review - Advanced Principles Methods of TeachingDocument5 pagesModule - Review - Advanced Principles Methods of TeachingJerric AbreraNo ratings yet

- Learning Pedagogy: Facilitator Dr. Munish KhannaDocument16 pagesLearning Pedagogy: Facilitator Dr. Munish KhannaParul KhannaNo ratings yet

- Final Theories of LearningDocument25 pagesFinal Theories of LearningFonzy GarciaNo ratings yet

- Answer For Foundation of EducationDocument4 pagesAnswer For Foundation of EducationvnintraNo ratings yet

- RRL 50Document7 pagesRRL 50Flint Zaki FloresNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument17 pagesChapter IIArief KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Authentic Learning For The 21st CenturyDocument12 pagesAuthentic Learning For The 21st Centuryapi-316827848No ratings yet

- Ofelia M. Guarin Assignment 101: Learning Knowledge Skills Values Beliefs HabitsDocument10 pagesOfelia M. Guarin Assignment 101: Learning Knowledge Skills Values Beliefs HabitsOfelia MecateNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Constructivist Learning & TeachingDocument5 pagesCharacteristics of Constructivist Learning & TeachingTiong Ing KingNo ratings yet

- BTE ASSIGNMENT 2 NOTESDocument3 pagesBTE ASSIGNMENT 2 NOTESmabusela2000rNo ratings yet

- Eced 15 LP 1 2Document60 pagesEced 15 LP 1 2Aniway Rose Nicole BaelNo ratings yet

- Adventures in Integrative Education: Multimedia Tools for Success in the Primary GradesFrom EverandAdventures in Integrative Education: Multimedia Tools for Success in the Primary GradesNo ratings yet

- 5optimization of Microstructure and Properties of As-Cast Various Si Containing Cu-Cr-Zr Alloy by Experiments and First-Principles CalculationDocument10 pages5optimization of Microstructure and Properties of As-Cast Various Si Containing Cu-Cr-Zr Alloy by Experiments and First-Principles Calculation波唐No ratings yet

- JGR Solid Earth - 2013 - Qiu - in Situ Calibration of and Algorithm For Strain Monitoring Using Four Gauge BoreholeDocument10 pagesJGR Solid Earth - 2013 - Qiu - in Situ Calibration of and Algorithm For Strain Monitoring Using Four Gauge Borehole波唐No ratings yet

- Failure Pressure in Corroded Pipelines Based On Equivalent Solutions For Undamaged PipeDocument8 pagesFailure Pressure in Corroded Pipelines Based On Equivalent Solutions For Undamaged Pipe波唐No ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction Theory in Public Administration Education Revisiting Student Evaluation of Teaching PDFDocument8 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Theory in Public Administration Education Revisiting Student Evaluation of Teaching PDF波唐No ratings yet

- BR J Haematol - 2023 - Hokland - Thalassaemia A Global View PDFDocument16 pagesBR J Haematol - 2023 - Hokland - Thalassaemia A Global View PDF波唐No ratings yet

- Regression PDFDocument33 pagesRegression PDF波唐No ratings yet

- 5研究中的博物馆概况Document6 pages5研究中的博物馆概况波唐No ratings yet

- 2博物馆互动多媒体的历史Document7 pages2博物馆互动多媒体的历史波唐No ratings yet

- 3博物馆参观者Document3 pages3博物馆参观者波唐No ratings yet

- TPL 6 Listening 1 WorksheetDocument2 pagesTPL 6 Listening 1 WorksheetRandyNguyenNo ratings yet

- DLL Week 5-Q3-D3Document2 pagesDLL Week 5-Q3-D3Ma. Jhysavil ArcenaNo ratings yet

- Language and Spelling and Reading and PhonicsDocument10 pagesLanguage and Spelling and Reading and PhonicsCho Madronero LagrosaNo ratings yet

- Lomce in EnglishDocument5 pagesLomce in EnglishTeresaNo ratings yet

- File 20220104060244Document2 pagesFile 20220104060244RAsha AtefNo ratings yet

- Grade 3 - All Subjects - WHLP - Q1 - W7Document6 pagesGrade 3 - All Subjects - WHLP - Q1 - W7Gladys QuiloNo ratings yet

- Storybook: The Little Red Hen: Lesson PlansDocument14 pagesStorybook: The Little Red Hen: Lesson PlansHeizyl ann VelascoNo ratings yet

- No. Team Name Score M Score: VP VPDocument30 pagesNo. Team Name Score M Score: VP VPNabilah AlhadadNo ratings yet

- Interview Project - FormsDocument12 pagesInterview Project - Forms6xqsdcbfwgNo ratings yet

- 2 JC2 H1 GP Prelim Hwa Chong Institution AnswerDocument15 pages2 JC2 H1 GP Prelim Hwa Chong Institution AnswerruoyingshuiyueNo ratings yet

- Higher 6-Week Revision ScheduleDocument2 pagesHigher 6-Week Revision ScheduleDan OlukwaNo ratings yet

- Final Module Activities 4 Peace Ed EU PDFDocument9 pagesFinal Module Activities 4 Peace Ed EU PDFChacha CawiliNo ratings yet

- Bai Tap Unit 5-8Document17 pagesBai Tap Unit 5-8Linh Chi Ngô PhạmNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Teacher Education: Bodine R. Romijn, Pauline L. Slot, Paul P.M. LesemanDocument15 pagesTeaching and Teacher Education: Bodine R. Romijn, Pauline L. Slot, Paul P.M. LesemanIoana BiticaNo ratings yet

- Spring 2024 - ENG526 - 1Document2 pagesSpring 2024 - ENG526 - 1Qurat Ul AinNo ratings yet

- Punjab Public Service CommissionDocument2 pagesPunjab Public Service Commissionabdul rehman0% (1)

- Moa BJMPDocument5 pagesMoa BJMPJordine UmayamNo ratings yet

- Choosing A College Major ArticleDocument4 pagesChoosing A College Major ArticlexyzNo ratings yet

- FOCUSING-TEACHING-AND-LEARNING-Grade-3-Ilang - IlangDocument15 pagesFOCUSING-TEACHING-AND-LEARNING-Grade-3-Ilang - IlangVG QuinceNo ratings yet

- Revised B.tech I Year 2022 2023Document1 pageRevised B.tech I Year 2022 2023harishjoshi aimlNo ratings yet

- Myongji University: Guideline For 2022 Fall Exchange ProgramDocument5 pagesMyongji University: Guideline For 2022 Fall Exchange ProgramThái Thị Kim Hà HQ1902 - 06 -No ratings yet

- MKCL Form MithibaiDocument2 pagesMKCL Form MithibaiAnosh AibaraNo ratings yet

- Alternative Learning System (ALS) For IndigenousDocument12 pagesAlternative Learning System (ALS) For IndigenousFLORENCE DE LEONNo ratings yet

- Mil Las 7Document6 pagesMil Las 7wimper 1195No ratings yet

- AicteDocument26 pagesAictewildlifephotographer1067No ratings yet

- Guaranteed Success ProgramDocument4 pagesGuaranteed Success ProgramKv kNo ratings yet

- Action Research ProDocument6 pagesAction Research ProRhea PeñarandaNo ratings yet