Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 viewsUntitled

Untitled

Uploaded by

Vasundhara RanaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- UNIT 1 Stress and Health PDFDocument43 pagesUNIT 1 Stress and Health PDFVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Institute of Management TechnologyDocument6 pagesInstitute of Management TechnologyVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Test Chapter 4,5,6.7Document2 pagesTest Chapter 4,5,6.7Vasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Clinical InterviewDocument29 pagesClinical InterviewVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Portfolio MIS Report - 3 - 20 - 2022Document10 pagesPortfolio MIS Report - 3 - 20 - 2022Vasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Olivia Mam Movie AnalysisDocument21 pagesOlivia Mam Movie AnalysisVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Promoting Independence For People With DisabilityDocument16 pagesPromoting Independence For People With DisabilityVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Practical Proposal Stress and Health - Huda Ma'amDocument3 pagesPractical Proposal Stress and Health - Huda Ma'amVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument2 pagesAbstractVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Page 1 of 4Document4 pagesPage 1 of 4Vasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- 0536657Document1 page0536657Vasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Confidentiality - General PrinciplesDocument2 pagesConfidentiality - General PrinciplesVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- 100003022Document4 pages100003022Vasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- ConfidentialityDocument10 pagesConfidentialityVasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 07-Feb-2023Document20 pagesAdobe Scan 07-Feb-2023Vasundhara RanaNo ratings yet

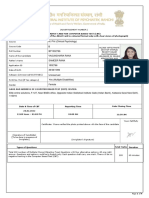

Untitled

Untitled

Uploaded by

Vasundhara Rana0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views143 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views143 pagesUntitled

Untitled

Uploaded by

Vasundhara RanaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 143

Neusoyo! Colaf oe |

@

BRIEE"

Behavior Rating

Inventory of, ,

Executive Function

PROFESSIONAL MANUAL

Gerard A. Gioia, PhD

Peter K. Isquith, PhD

Steven C. Guy, PhD

Lauren Kenworthy, PhD

R Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

TTT @e2000000

COOSOOHTSHHHOHHHOOOO

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgments ..

Chapter 1. Introduction

‘The Executive Functions.

Brain Basis of the Executive Functions.

Developmental Factors...

Clinical Assessment

Chapter 2, Administration and Scoring.

BRIEF Materials

‘Appropriate Populations

Professional Requirements ..

General Administration...

‘Administration of the Parent Form.

‘Administration of the Teacher Form...

‘Scoring and Profiling the Parent and Teacher Forms

Caleulating Seale Raw Scores...

Missing Responses.

Scoring the Negativity Scale...

Scoring the Inconsistency Scale...

Converting Raw Scores to T Scores...

Calculating Confidence Intervals.

Plotting the BRIEF Profile...

Chapter 3. Interpretation of the BRIEF Parent and Teacher Forms 13

‘Normative Comparisons.. u

‘Assessing Validity u

Other Indications of Compromised Validity. 15

Climical Scales...nenee Ww

Inhibit... : Ect

Shift... 18

Emotional Control 18

Initiate. 18

19

‘Working Memory

3

Plan/Organize....

Organization of Materials

Monitor... =

‘The Behavioral Regulation Index, the Metacogition Inder, and the Global Executive Composite

Behavioral Regulation Index.

Metacognition Index...

Global Executive Composite.

Individual Item Analysis..

Interpretive Case Illustrations...

Case Mustration 1. Bight-Year-Old Boy With ADHD, ‘Combined Type

Case Ilustration 2. Nine-Year-Old Girl With Nonverbal Learning isa and ADHD,

Predominantly Inattentive Type

Case Tlustration 3, Twelve-Year-Old Boy With Traumatic Brain Injury.

Case Ilustration 4. Eleven-Year-Old Boy With Asperger's Disorder

Case Illustration 5, Fiteen Year-Old Girl With BxecutivelOrganizatonal Dysfunction.

Case Illustration 6. Ten-Year-Old Boy With Reading Disorder...

Chapter 4, Development and Standardization of the BRIEF..........

Development

Item Content.

Item Development...

Item-Seale Membership.

Item Tryouts...

Final Seale Development.

Validity Seales...

Inconsistency Scale....

Negativity Scale..

Standardization ...

Demographic Characteristics.

Influence of Demographie Characteristic of Respondent and Child

Development of the Normative Groups.

Construction of Scale Norms...

Chapter 5. Reliability and Validity

Reliability cnn

Internal Consistency

Interrater Reliability.

Test-Retest Reliability

Validity

Content Validity.

Construct: Validity

Factor Analysis...

Epusaiary Fock Auge

Principal Factor Analysis of the BRIEF and Other Behavior Rating Scales.

vi

Fee Oe ete eet eoeoveou"

eee60

ee

eeeoceoe

e

e

e

References..

Appendix A: T-Score and Percentile Conversion Tables and 90% Confidence Interval Values

Appendix B: T-Score and Percentile Conversion Tables and 90% Confidence Interval Values

BRIEF Profiles of Diagnostic Groups.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder.

‘Traumatic Brain Injury...

‘Tourette's Disorder...

Reading Disorder

Low Birth Weight

Documented Brain Lesions .......

High Functioning Autism

Pervasive Developmental Disorders..

Early-Treated Phenylketonuria....

Mental Retardation.....

Clinical Uiity of the BRIEF for Diagnosis of ADHD

Predictive Validity.

Clinical Utility...

Summary oon

89

for BRIEF Parent Form: Boys by Age Group

for BRIEF Parent Form: Girls by Age Group.

‘Appendix C: T-Score and Percentile Conversion Tables and 90% Confidence Interval Values

for BRIEF Teacher Form: Boys by Age Group... seo

103

17

Appendix D: T-Score and Percentile Conversion Tables and 90% Confidence Interval Values

for BRIEF Teacher Form: Girls by Age Group... 131

1

RE

INTRODUCTION

The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive

Function (BRIEF) is a questionnaire for parents and

teachers of school age children that enables profes-

sionals to assess executive function behaviors in the

home and school environments; It is designed for

broad range of children, ages 5 to 18 years; including

those with learning disabilities and attentional dis-

orders, traumatic brain injuries, lead exposure, per-

vasive developmental disorders, depression, and

other developmental, neurological, psychiatric, and

medical conditions. The Parent and Teacher Forms of

the BRIEF each contain 86 items within eight theo-

retically and empirically derived clinical scales that

measure different aspects of executive functioning:

inhibit, Shift, Emotional Control, Initiate, Working

Memory, Plan/Organize, Organization of Materials,

and Monitor. Table 1 describes the clinical scales and

two validity scales (Inconsistency and Negativity).

‘The clinical scales form two broader Indexes,

Behavioral Regulation and Metacognition, and an

overall score, the Global Executive Composite. Two of

the scales, Working Memory and Inhibit, are clini-

cally useful in differentiating the diagnostic subtypes

of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

This manual provides information about the

BRIEF materials, administration and scoring proce-

dures, and normative data, as well as guidelines for

clinical interpretation and a variety of case studies to

assist you in understanding the results obtained on

the BRIEF. The manual also describes the develop-

ment of the instrument and results of studies that

establish the reliability, validity, and diagnostic

utility of the BRIEF as a measure of executive fune-

tion in children,

THE EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS

‘The executive functions are a collection of

processes that are responsible for guiding, directing,

and managing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral

functions, particularly during active, novel problem

solving, The term executive function represents an

umbrella construct that includes a collection of inter-

related functions that are responsible for purposeful,

goal-directed, problem-solving behavior. Welsh and

Pennington (1988) characterized the early develop-

ment of the executive functions in terms of “the abi

for attainment of a future goal” (p. 201). Stuss and

Benson's (1986) classic work describes a set of

related capacities for intentional problem_solving

that

. Their hierarchical

cts of the executive

functions that relate to the highest levels of cogni-

tion: anticipation, judgment, self-awareness, and

decision making. Their model distinguishes “execu-

tive,” or directive, cognitive control functions from

more “basic” cognitive functions (e.g., language,

visual-spatial, memory abilities)

(Specific subdomains that make up this collection

of regulatory or management functions include the

ability to initiate behavior, inhibit competing actions

or stimuli, select relevant task goals, plan and organ-

i ex problems, shift

Table 1

Description of the Clinical and Validity Scales on the BRIEF Parent and Teacher Forms

Number of items

Scale Parent Teacher Behavioral description

Clinical scale

Inhibit 10 10 Control impulses; appropriately stop own behavior at the proper time

Shift 8 10 “Move freely from one situation, activity, or aspect of a problem to

another as the situation demands; transition; solve problems flexibly

Emotional Control 10 ‘Modulate emotional responses appropriately.

Initiate 8 Begin a task or activity; independently generate ideas.

Working Memory 10 10 “Hold information in mind for the purpose of completing a task; stay

with, or stick to, an activity.

Plan/Organize 2 10 ‘Anticipate future events; set goals; develop appropriate steps ahead of

time to carry out an associated task or action; carry out tasks in a

systematic manner; understand and communicate main ideas or key

concepts.

Organization of Materials 1 Keep workspace, play areas, and materials in an orderly manner.

Monitor 10 Check work; assess performance during or after finishing a task to

ensure attainment of goal; keep track of the effect of own behavior on

others.

Validity scales

Inconsistency 19 1 Bxtent to which the respondent answers similar BRIEF items in an

inconsistent manner.

Negativity 9 9 Extent to which the respondent answers selected BRIEF items in an

unusually negative manner.

solving, is also deseribed as a key aspect of executive

fanction (Pennington, Bennetto, McAleer, & Roberts,

1996). Finally, the executive functions are not exclu-

sive to cognitive control; regulatory control of emo-

tional response and behavioral action also falls under

the umbrella of the executive functions.

Brain BASIS OF THE

EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS

‘The developmental course of the executive func-

tions parallels the protracted course of neurological

development, particularly with respect to the pre-

frontal regions of the bram. One common view of the

neuroanatomic organization of the executive func-

tions, however, is that they are seated solely in the

prefrontal region. This is an oversimplification of the

complex organization of the brain. Although damage

to the frontal lobes can result in significant dysfune-

tion of various executive subdomains (Anderson,

1998; Asarnow, Satz, Light, Lewis, & Neumann, 1991;

Eslinger & Grattan, 1991; Fletcher, Ewing-Cobbs,

2

Miner, Levin, & Bisenberg, 1990), these functions di

not simply reside in the frontal lobes. An under-

standing of the frontal region of the brain is, how-

ever, important in any discussion of the executiv

functions. The neuroanatomical essence of the

frontal lobes is their dense connectivity with other

cortical and subcortical regions of the brain, The

prefrontal system is highly and reciprocally intercon

nected through bidirectional connections ‘with the

jimbic (motivational) system, the reticular activating@es

(arousal) system, the posterior. association cortex@jms

(perceptual/eognitive processes and knowledge base), as

and the motor (action) regions of the frontal lobes@jum

(e.g, Johnson, Rosvold, & Mishkin, 1968; Porrino Sux

Goldman-Rakic, 1982). Such a central meuro-@s

anatomic position underlies the regulatory control qx

that the frontal brain systems exert over the poste-q@ux

rior cortical and subcortical systems (Welsh &@us

Pennington, 1988). e

‘The concept of frontal system (as opposed to lobe)

explicitly acknowledges and directly incorporates

the interconnections of the frontal region with the@

e

e

cortical and subcortical regions of the brain.

Importantly, a disorder within any component of the

frontal system network can result in executive dys-

function (Mesulam, 1981). Conditions that render

the frontal systems vulnerable to dysfunction include

the following: disorders affecting the connectivity. of

the brain such as cranial radiation and white matter

development (Brouwers, Riccardi, Poplack, & Fedio,

i984), ead poi g_affecting synaptogenesis

Goldstein, 1992),

regions in traumatic brain injury a

dopamine in” Tourette's Disorder

Rogeness, Javors, & Pliska, 1992; Singer & Walkuy

1991), disorders involving aspects of the posterior

cortex such as learning disabilities,

the arousal mechanism such as those seen in brain

njury and severe depression. Thus, executive dys-

fanction can arise ‘from damage to the primary pre-

frontal regions as well as damage to the densely

intereonnected posterior or subcortical areas.

DEVELOPMENTAL FACTORS

A.unique feature of the executive functions is their

prolonged developmental course (eg, Levin et al.,

1991; Passler, Issac, & Hynd, 1985; Welsh &

Pennington, 1988) in comparison with other cogni-

tive functions, paralleling the prolonged pattern of

neurodevelopment of the prefrontal regions of the

brain. The development of attentional. control,

future-oriented intentional problem solving, and self-

regulation of emotion and behavior ean be observed

beginning in infaney and continuing through the pre-

school- and school-age years (Welsh & Pennington).

The development of goal-directed, planful problem-

solving behaviors has 10

ung as 12 months of age using an object perma-

nence and object retrieval paradigm (Diamond &

Goldman-Rakic, 1989). Bighteen-month-old children

xchibit specific self-control abilities to maintain an

nntional action and inhibit behavior incompatible

ith attaining a goal (Vaughn, Kopp, & Krakow,

1984). Thus, early intentional self-control behaviors

tin infants and toddlers for the purpose of

ed problem solving. Hxecutive self-control

t these early ages 18, however, variable, fragile, and

bound to the external stimulus situation; stability

ee studies througt

strate a time-related course of development for

specific subdomains of executive function, including

inhibitory control (Passler et al.), flexible problem

solving (Chelune & Baer, 1986; Levin et al.; Welsh,

Pennington, & Grossier, 1991), and planning (Klahr

& Robinson, 1981; Levin et al.; Welsh et al.). As is the

case with most dimensions of psychological and neu-

ropsychological development, the emergence of exec-

utive control functions varies across individuals in

terms of both the timing of specific subdomains and

the final endpoint. maaan

Executive functions of self-awareness and control

develop in parallel with the domain-specific content

area or functional areas as described by Stuss and

Benson (1986). For example, as basic memory skills,

develop (e.g., immediate memory span, encoding, or

retrieval), “metamemory” (i.c., knowledge about how

to strategically use and control these memory abili-

ties for particular tasks or situations) develops con-

currently (Brown, 1975). An important corollary to

consider is that if the basic ability does not deve

then the associated metacognitive knowledge

“as fully. This point relates directly to the

iRGwGu TE imetacognition in learning disabilities

(Pressley & Levin, 1987; Siegel & Ryan, 1989;

Swanson, Cochran, & Ewers, 1990; Wong, 1991) and

the development of self-control strategies within the

context of specific processes (e.g., reading disorder,

writing process), Assessment and intervention in

learning disabilities must, therefore, include the con-

trol strategies (e.g., recognizing the critical “problem”

situation, planning and evaluating the use of specific

learning strategies), in addition to the primary

domain-specific processing disorder (e.g., decoding

words, extracting meaning from sentences).

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Historically, clinical assessment of the executive

functions has been challenging given their dynamic

essence (Denckla, 1994). Fluid strategic, goal-

oriented problem solving is not as amenable to a

paper-and-pencil assessment model as are the more

domain-specific functions of language, motor, and

visuospatial or visual/nonverbal abilities. Further-

more, the structured nature of the typical assessment

situation often does not place a high demand on the

executive functions, reducing the opportunity for

observing this important domain (Bernstein & Waber,

1990). We believe the child’s everyday environments

3

at home and at school serve as important venues for

observing the essence of the ‘executive functions.

Parents and teachers possess a wealth of information

about the child's behavior in these settings that is

directly relevant to an understanding of the child's

executive function. Arich tradition exists in utilizing

structured behavior rating systems to assess psy-

chological and neuropsychological constructs

(Achenbach, 1991a; Conners, 1989; Reynolds &

Kamphaus, 1992). The use of rating scale systems,

completed by parents and teachers, measuring overt

behavior is an often-used and well-proven method

for assessing various domains of social, emotional,

and behavioral functioning. Additionally, behavioral

inventories completed by caregivers are widely

employed in the assessment of adaptive behavior

(eg. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales; Sparrow,

Balla, & Cicchetti, 1984) and personality develop,

ment (Personality Inventory for Children; Lacha:

1982). The authors believe there is a need for a rat

ing scale to assess the range of behavioral manifé

tations of executive functions in children. A reliabl

and valid behavior rating system can serve as =

important adjunct to the clinical evaluation an

treatment of problems that involve the executiv’

control functions.

‘The BRIEF is a reliable and valid behavior ratin

scale of executive functions in children and adoles

cents that can (a) become an integral part of the clin

ical and school assessment of children ani

adolescents and (b) assist with focused treatmenj

and educational planning for children with disorder

of executive function.

2

aE

ADMINISTRATION AND SCORING

BRIEF MATERIALS

‘The BRIEF materials consist of the Professional

anual, the Parent Form, the Teacher Form, and the

so-sided Scoring Summary/Profile Form. The cover

lage of each rating form (Parent and Teacher)

eludes instructions for completing the form and

xamples for marking responses directly in the book-

et. The remaining two pages of each form contain

he BRIEF items and an area for recording demo-

rraphic information about the child and information

ibout the respondent's relationship to the child. The

arbonless rating booklet is designed to be hand-

scored by the examiner.

One side of each Scoring Summary/Profile Form

Parent and Teacher) provides instructions for hand-

scoring the BRIEF clinical and validity scales and

ndexes, as well as summary tables for recording raw

scores, T scores, and percentiles for scales and

ndexes. Conversion of raw scale scores to T scores

-an be accomplished using the normative tables

jocated in the appendixes at the end of this manual.

The reverse side of the Scoring Summary/Profile

Form provides a graph for plotting T scores to visu-

ally portray the respondent's clinical scale, index,

and GEC scores relative to those of the normative

sample.

APPROPRIATE POPULATIONS

The BRIEF was standardized and validated for

use with boys and girls, ages 5 through 18 years. The

tative sample included children from a range of

racial and socioeconomic backgrounds and geo-

graphic locations, including inner city, urban, subur-

ban, and rural environments. As a result, the BRIEF

is appropriate for school-age children in a wide range

of social and demographic contexts.

PROFESSIONAL REQUIREMENTS

‘The BRIEF can be administered and scored by

individuals who do not have formal training in neu-

ropsychology; clinical psychology, school psychology,

counseling psychology, or related fields. The exam-

iner should carefully study the administration and

scoring procedures presented in this manual. In

keeping with the Standards for Educational and

Psychological Testing of the American Education

Research Association, American Psychological Associa-

tion, and National Council on Measurements in

Education (1985), interpretation of the BRIEF scores

and profiles requires graduate training in neuropsy-

chology, clinical psychology, school psychology, counsel-

ing psychology, neuropsychiatry, behavioral neurology,

developmentaVbehavioral pediatrics, general pedi-

atries, or a closely related field, as well as relevant

training or coursework in the interpretation of psycho-

logical tests at an accredited college or university.

GENERAL ADMINISTRATION

Materials required for administration are the

BRIEF Parent Form and/or Teacher Form booklets, a

hard-point pen or a pencil, and a flat writing surface.

Because instructions for administering the Parent

and Teacher Forms of the BRIEF differ slightly, they

are discussed separately in the following sections.

Administration of the Parent Form

Selecting Raters

‘The BRIEF Parent Form is designed to be com:

pleted by the child's parent or guardian. It is desi

able to obtain ratings from both parents, if possible.

‘This provides more information on the child's behav-

ior and can reveal areas of disagreement that may be

important to the assessment and identification of

5

intervention strategies. When a choice is necessary,

it is preferable to obtain the rating from the person

with the most recent and most extensive contaet with

the child.

Establishing Rapport and

Giving Instructions

It is essential to establish good rapport with the

person completing the form. Instructions to the par-

ent should emphasize the importance of responding

to all items on the form. The following instructions

may be used as a guide:

Parents observe a lot about their children’s

problem solving and behavioral functioning

that cannot be measured in an office visit. Your

help is essential to me as I attempt to under-

stand your child. This questionnaire allows you

to document your observations of your child’s

functioning at home. Please read the instruc-

tions and respond to all of the items, even if

some are difficult or do not seem to apply. As

you will see, the instructions ask you to read a

list of statements that describe children’s

behavior and indicate whether your child has

had any problems with these behaviors in the

past 6 months. If the specific behavior has never

been a problem in the last 6 months, circle the

letter “N”; if the behavior has sometimes been a

problem, circle the letter “S”; if the behavior

has often been a problem, cirele the letter “O.” If

you have any questions or concerns, please

don’t hesitate to ask for my help.

Completing and Checking the Record Form

‘The BRIEF Parent Form will take approximately

10 to 15 minutes to complete. Ideally, the parent or

guardian should complete the form in a quiet setting

and in one sitting. Once the form has been com-

pleted, review it for blanks or multiple responses. If

any are found, ask the parent to go back and

respond to the skipped items or to clarify any

ambiguous responses. If this is not practical, or if

the parent refuses to answer certain items, proceed

with scoring,

Administration of the Teacher Form

Selecting Raters

‘The BRIEF Teacher Form is designed to be com-

pleted by any adult who has had extended contact

with the child in an academic setting. Typically this

will be a teacher, but a teacher's aide or other knowl-

edgeable person can be used as an informant when

necessary. To provide valid ratings, the respondent

6

should have had a considerable amount of contagaJ

with the child. For example, 1 month of daily contagh J

should be sufficient. Multiple ratings from teache}

who observe the child in different classes can be

ful in showing how the youth responds to varieg sy

teaching styles, academic demands, and curriculugy

content areas.

Establishing Rapport and

Giving Instructions,

It is important to establish good rapport with t)

person completing the form. Instructions to #

teacher should emphasize the importance of respo1

ing to all items on the form. The following inst

tions may be used as a guide:

Iam evaluating a child in your class. I need

your help to fully understand his/her learning

and behavior in school. This form takes 10 to 15'

minutes to complete. Please read the instruc-

tions and respond to all of the items, even ift

some are difficult or do not seem to apply. As

you will see, the instructions ask you to read a

list of statements that describe children’s

behavior and indicate whether this student has

had any problems with these behaviors in the

past 6 months. If the specific behavior has never

been a problem in the last 6 months, circle the

letter “N”; if the behavior has sometimes been a

problem, cirele the letter “S”; if the behavior

has often been a problem, circle the letter “O.” If'

you have known the student for less than 6

months, you may still respond to the question-

naire based on your experience. If you have any

questions or concerns, please don’t hesitate to

ask for my help.

Completing and Checking the Record Form

‘The BRIEF Teacher Form will take approximate |

10 to 15 minutes to complete. Ideally, the teach

should complete the form in a quiet setting and

one sitting. Once the form has been completet |

review it for blanks or multiple responses. If any ate

found, ask the teacher to go back and respond |

skipped items or to clarify any ambiguous responses

If this is not practical, or if the teacher refuses J

answer certain items, proceed with scoring.

SCORING AND PROFILING THE

PARENT AND TEACHER FORMS

Tear off the perforated strips along the sides of t

completed rating booklet and peel away the top shet

(answer sheet) to reveal the scoring sheet beneath. Missing Responses

Demographic information and the rater’s responses Examine the scoring sheet for unanswered items.

are reproduced on the carbonless scoring sheet. The If the total number of unanswered items that con-

'scoring sheet is used to calculate the raw scale sores tribute to the calculation of scale raw scores is

jfor each of the eight clinical scales. greater than 14, then the BRIEF protocol cannot be

[Calculating Seale Raw Scores appropriately scored. In such eases, the respondent

The rater’s responses are reproduced as circled Should be asked to complete the missing items if pos-

n scores on the scoring sheet, with 1 correspon- _—‘“ible. Similarly, if more than two items that con-

z to Never (N), 2 corresponding to Sometimes (S), _tTibute to the calculation of a scale raw score have

land 3 corresponding to Often (O), Transfer the circled _‘™issing responses, then a scale raw score should not

gore for each item to the box provided in that item be calculated for that scale. Otherwise, missing

ow. Sum the item scores in each column and enter _-Tesponses for 2a mes

subtotal in the box at the bottom of the column, Seale raw seore sho ae i

the first page ofitems, transfer the subtotal sore _falculating the Scale raw sore: erase Teems 73

‘each scale to the appropriate box in the row for {~ ‘hrougl on ‘arent Form: ant 8 7

otals at the bottom of the facing page. Sum the | through 86 on the Teacher Form are not included in

subtotals foreach scale and enter the total inthe | ‘he caleulation of Total seale raw senros, missing

scale raw seores box atthe bottom of the appro- | responses {oF these particular items wil not aff

e column, Transfer each Total scale raw score to he calculation of raw scores for the cl scales.

Figure 2 presents a completed scoring sheet for an 8-

aw score column in the Scoring Summary Table Z ;

Scoring Summary/Profile Form (see Figure 1), | _ Y°*r-0ld boy with ADHD, Combined Type.

that the last 14 items on the Parent Form scor- Scoring the Negativity Scale

heet and the last 13 items on the Teacher Form Negativity scale items are indicated by an “N”

ng sheet do not have boxes for transcribing item enclosed in a box in the margins on the scoring sheet

. These items are not used in calculating Total of the rating form. Examine the scoring sheet to

raw scores; several of the items (.e., those determine which, if any, of these items were scored

dN in the margins on the scoring sheets) are ag 3 (i.e., endorsed as “Often” by the respondent).

calculate a score on the Negativity scale. Locate the Negativity scale area on the Scoring

Summary page of the Scoring Summary/Profile

Beraviomar aT Form. Circle each item number in the boxed column

Parent Foray that received an item score of 3, and then enter the

Scoring Summary Table

a number of circled items at the bottom of the column

aa en eeceet [Eva to obtain the Negativity score (see Figure 3).

26 | 735| 97 Scoring the Inconsistency Scale

13 | 53 | 74 ‘The Scoring Summary/Profile Form provides an

area for calculating the Inconsistency Scale score.

‘This calculation is somewhat complex and must be

done carefully to ensure accuracy. Inconsistency

scale items are indicated by a circled “I” ((D) in the

margins on the scoring sheet of the rating form.

‘Transfer the item scores for the 10 item pairs from

the scoring sheet to the appropriate boxed columns

(labeled Score) at the bottom right of the Scoring

‘Summary page.

For each item pair, calculate the absolute value of

umple of Scoring Summary Table: Parent the difference in item scores for the two items. For

example, if the item score for the first item is 1 and

27 | 73 | 98

COGL TION

= 64501 EX UINE COMPOOTE |

GenderMalecrade Std age @ Birth Date 11 / / 5 / 90

Child's Name

Your Name Relationship to Child_ Mother Today's Date, /

Eton Working

nit | “Contot_| inte Lo Monitor_|

t 3 ie

2. 3 1 2

3 3 + e

4, ] 1 oO

5. = 1

6 1 @ 2

th 3s © 2

8. 1 2

®. 2 ti

10. 3 ea

tt, 3 ue

12, 1

18. Zz t

14. 3 1 2

15. = 1 =

16. 3 Tee

1. ee

18. 3 en

19, 3 cove

20. 3 1 2

at, 2 Tee

2, C3 1 2

Ba 1 a

2 T_] 2 3

25, 2 t oO

2. 2) 1 3

2. S (VID

28, (ES teu @ee 8

2. ED

30. 2: 1 @ [3_N],

3. &. + ap

92. 3 1 2 Y@®

8 2 CORO

wu. 3 oe

%. 3 ty

3. 3 ae

w. a 1a

[2 1 3 @

38. 2 1 a

40. 3 ‘aaa 8

a. ToD @

2 2 1 @ 3@

a [3 Sey

“41 2 1 @ 3®

to | 13 | 13 9 | 25 | 25 [ 6 | 13 | ssttan(nmerg

Figure 2. Completed BRIEF Scoring Sheet.

Eotinal Working

vow | sun | “Contot | ite | Memory

= * “

4.

@

48

oY

50,

51,

2.

53, ef

|S

soa:

#.[ 2 |

sr. 5

58

(ae

60.

61. 2

62. 2

= =a

6

eae fp

66.

or.

83

6, 2

70 3

1. 7a

2

eee

14,

%.

8.

7.

7.

78,

80.

81.

2

83:

%,

&.

8,

Emotional Working Pla Org. of

tone __shit__“Conral"__inlato__Memory__Orgeize Mates Montor

16 14 12 3 12 12 | 8 _| Subtotals (items 45-86)

to | 13 | 15 9 [| 23 | 23 | G6 | 15 _| suttotas (tems 1-44)

I 26 13. 27 21 26 | 35 18 21 _| Total scale raw scores

Figure 2. (continued)

eeecod

Negativity Scale

+1. Locate the frst Negativity item (indicated with a boxed N- | Item

(rar aagharte Seng Sih Porcat Nepacy. | No.

fuuhiecedsdctaemnmbsnts a

counts ae

2. Count the number of circled items to determine the 8.

Negativity score. 23.

‘3. Circle the appropriate Protocol classification based on 30.

havo ®

Wogetity Cumulative Protea

‘score percentile classification nm.

a x @

ss ot-98 Ente 2

aT 798 Highly elevated |@|

Negativity score |" >

(Range = 0 to 8) |

Figure 3. Sample of Negativity scale score

calculations: Parent Form.

the item score for the second item is 3, subtract the

lesser number (1) from the greater number (3) to

obtain the absolute difference value of 2. Sum the dif-

ference values for the 10 item pairs to obtain the

Inconsistency score (see Figure 4).

Converting Raw Scores to T Scores

‘To obtain a T score and percentile for each scale

raw score, locate the normative table for the appro-

priate gender and age range in the Appendixes at the

end of this manual. Enter the T' score and percentile

for each scale in the spaces provided in the Scoring

Summary Table (see Figure 1)

To calculate the Behavioral Regulation Index

(BRD raw score, sum the scale raw scores obtained

for Inhibit, Shift, and Emotional Control; enter this,

value in the space provided in the Scoring Summary

‘Table on the Scoring Summary/Profile Form. Locate

the BRI raw score in the appropriate Appendix table

and read across the table to obtain the correspon-

ding T score and percentile; enter these values in the

spaces provided in the Scoring Summary Table.

Similarly, calculate the Metacognition Index (MI)

raw score by summing the raw scale scores obtained

for Initiate, Working Memory, Plan/Organize,

Organization of Materials, and Monitor; enter this

value in the space provided. Locate the MI raw score

in the Appendix table for the appropriate gender and

age group and read across the table to obtain the cor-

responding T score and percentile; enter these values

in the spaces provided. Finally, to calculate the

10

Inconsistency Scale

Ttemno.| Score | [item no. Score

roa |p 25. i

1 |-s_-|2 | 3 | >

7 | 3 cre ESF FS) 2

33 | 2 ale ills:

2 el 2 | >

i 6 | 3 | >

2 [2 | 2i)>

> [a2 a | 3 | >

| 3 o | 3 | >

5 | 3 a | 2) >

Inconsistency score

{Range = 01020)

Figure 4. Sample of Inconsistency scale score

caleulations: Parent Form.

Global Executive Composite (GEC) raw score,

the raw scores for BRI and MI; enter this value i

space provided in the Scoring Summary Table.

the GEC raw score in the Appendix table fo

appropriate gender and age group and read acros

table to obtain the corresponding 7 score and,

centile; enter these values in the spaces providi

the Scoring Summary Table.

Calculating Confidence Intervals =

Confidence intervals provide the band of mea‘

ment error that is associated with a clinical

index, or GEC T' score, The 90% confidence inte

(CI) was chosen because it is commonly used for St

ical interpretation. The bottom of each column itl

Appendix tables shows the CI values needed to

culate the 90% confidence interval for that set

index, or the GEC. These values were calculateS*t

multiplying the standard error of measurerfe:

(SEM) for each clinical scale/indew/GEC by ©

( score for the 90th percentile). To obtain"

90% confidence interval for a given scale, int

or GEC T score, add the CI value from the bof!

row of the appropriate column to the T score. EM

this number as the high end of the interval. TH

subtract the CI value from the T' score and

this number as the low end of the interval. -

Plotting the BRIEF Profile

‘Transcribe the T scores for each of the ea

clinical scales, the two indexes, and the GEC

the Scoring Summary Table to the correspont

i

paces along the bottom of the Profile Form (located

n the reverse side of the Scoring Summary page).

‘lot the T score obtained for each scale, index, and

he GEC by first locating the T score within either

he far left or the far right column on the Profile

‘orm and then carefully marking an X on the corre-

ponding tick mark in the appropriate scale column.

\fter all the T scores have been plotted, connect the

‘without crossing the vertical lines) to provide a

rrofile of the BRIEF scores (see Figure 5).

‘To assist in interpretation of the clinical scales, the

horizontal rule located on the Profile Form at a

T score of 50 represents the mean of the T score dis-

tribution. The horizontal rule at aT’ score of 65 rep-

resents the point 1.5 standard deviations above the

mean, which is the recommended threshold for inter-

pretation of a score as abnormally elevated (see chap-

ter 3); this area of potential clinical significance is

indicated by light shading on the Profile Form.

uu

BRIEF

Child's Name

Tscore

aice-f

wf

wo}

4

4

wd

notional

Control

=]

4

un

Tscore_73.

tick mark coresponding fo each T's

Emotional

oni

73 _75

Instructions: Tanslr tie Scale dex and GEO T cores tom the Scorig Sumary Table onthe side Of this form. Mark an X on the

Spe raladl wretidied al Sein eblbeneg a

Figure 5. Completed BRIEF Profile Form.

Organize Materials Montor

3

sg

INTERPRETATION OF THE

BRIEF PARENT AND TEACHER FORMS

This chapter describes the proper method for

sterpreting BRIEF Parent and Teacher Form scores

explaining how to (a) make normative compar-

(b) assess the validity of the BRIEF results,

p interpret domain-specific clinical scale scores, (d)

pret the Index scores and the Global Executive

Smposite score, and (e) review individual items.

though 18 of the items on the Parent and Teacher

orms of the BRIEF differ in order to appropriately

pflect the different settings in which they measure

vior, the interpretation of the clinical scale and

dex scores derived from the Parent and Teacher

rms is identical, Therefore, the following discus-

en applies to both Parent and Teacher Forms.

‘The first step in the competent clinical interpreta-

pn of the BRIEF is a solid, working understanding

the concepts, clinical manifestations, and assess-

ent of the executive functions. This manual only

fly addresses the conceptual and clinical assess-

issues regarding executive function. The

/examiner is referred to more comprehensive

scussions of conceptual issues (Krasnegor, Lyon, &

dman-Rakic, 1997; Lyon & Krasnegor, 1996;

h & Pennington, 1988) and assessment issues

Boia, Isquith, & Guy, in press; Lezak, 1995).

condly, a thorough understanding of the BRIEF,

suding its psychometric development and proper-

. is a prerequisite to interpretation. (See chapters

snd 5 for an in-depth discussion of these issues.) As

any clinical method or procedure, appropriate

ning and clinical supervision is necessary to

competent use of the BRIEF.

essment of the executive functions is a complex

with unique features. Given that the executive

tions are “meta” level in nature, their elucida-

in a clinical testing protocol can present signifi-

challenges. Furthermore, there is no singular

disorder of executive function, but rather a variety of

presentations involving one or more aspects of of exec

So umber of common Sy

ect_different_ pai

dysfunction. ‘These syndromes may be developmental

in ( pervasive developmental disorders,

learning disabilities, ADHD) or acquired (e.g., as a

result of traumatic brain injury or cranial radiation

as treatment for brain tumors and leukemia).

‘A clear understanding of the differences between

assessment of the “basic” domain-specific content

areas of cognition (e.g., memory, language, visuospa-

tial) and the domain-general or “control” aspects of

cognition and behavior is essential. For example,

what may appear as a problem with language

expression may be due less (or not at all) to the basic

aspects of linguistic functioning (e.g., vocabulary,

syntax, semantics) than to poor “metalinguistic”

functions (e.g., formulating and maintaining an

organized, planful approach to the topic of conversa

tion). There is no test or assessment battery that

gularly assesses executive function. By necessity,

both elements, the domain-specific content area and

its regulatory executive control processes, are always

present in any test. Thus, part of the challenge of

assessing executive functions is separating cognitive

and behavioral control functions from domain-

specific functions. Frequently, the more novel and/or

complex the task or situation, the greater is the

demand for the executive functions. The more famil-

iar, automatic, and simple the task, the less the child

needs to recruit his or her executive functions. What

/ may be a complex, novel task for one child may be a

| relatively familiar and automatic task for another,

thus, different children may need to recruit vastly

different degrees of executive control functions to

\ solve a particular problem.

13

The BRIEF was developed to provide a window

into the everyday behavior associated with specific

domains of self-regulated problem solving and social

functioning. Given the multiple determinants of any

particular behavior, it is important to consider the

full range of factors, including the executive func-

tions that might play a role in the child's functioning.

As such, the executive or regulatory aspects of behav-

ior have a unique, complex, and at times hidden; role

in cognition and behavior. Gathering reliable ratings

of behavior associated with executive function via

the BRIEF can add important information to the

overall assessment of a child's strengths and weake

nesses. Although the BRIEF can appropriately serve

as a screening tool for possible executive dysfunction,

the clinical information gathered from an in-depth

profile analysis is best understood within the context

of a full assessment that includes a detailed history

of the child and family, performance-based testing,

and observations of the child’s behavior.

NORMATIVE COMPARISONS

T scores are used to interpret the child's level of

executive functioning as reported by parents and/or

teachers on the BRIEF rating form. These scores are

linear transformations of the raw scale scores (M =

50, SD = 10). T scores provide information about an

individual’s scores relative to the scores of respon-

dents in the standardization sample. For example, a

T score of 70 would indicate that the respondent's

score is 2 standard deviations above the standardi-

zation sample mean and equals or exceeds the scores

of approximately 90% of the respondents in the stan-

dardization sample. The exact ‘percentile for each

raw score varies slightly for each scale, as the scores

are not normally distributed. Thus, a T' score of 70

may exceed 90% of the normal population for one

scale and 93% for another scale. It is often helpful to

‘examine both T scores and accompanying percentiles

when interpreting the BRIEF. Higher raw scores,

percentiles, and T scores indicate greater degrees of

executive dysfunction. For all the BRIEF clinical

scales and indexes, T' scores at or above 65 should be

considered as having potential clinical significance.

Assessing Validity

Before interpreting BRIEF parent or teacher

scores, it is essential to carefully consider the validity

of the data provided. The inherent nature of rating

scales (ie. relying upon a third party for ratings of a

4

child’s behavior) brings potential bias to the

(EF contains, two. scales that provide

‘on validity: the Inconsistency and Neg

Inconsistency Scale

Scores on this scale indicate the extent to $

the respondent answers similar BRIEF items

inconsistent manner relative to the clinical sa

For example, a high Inconsistency score for a

might be associated with marking Never in re

to Item 44 (Gets out of control more than frientisg

the same time as marking Often in response tf

54 (Acts too wild or “out of control”). Item pairsc]

prising the Inconsistency seale, along with intetsjl

correlations, and cumulative percentiles for abS

difference scores are shown in Tables 2 and 3 {9

Parent and Teacher Forms, respectively. T' scores

not generated for the Inconsistency scale. Inst}

the raw difference scores between 10 paired tu

(see chapter 2) are summed and the protocol ie

sified as either “Acceptable,” “Questionabl&

“Inconsistent.”

The examiner must carefully review pra

classified as “Questionable” or “Inconsistent.” I

minor content differences between paired Inq

teney items, one should consider the possibility

there is a reasonable explanation for the Ini

teney score other than response inconsistency @

part of the respondent. If the respondent can e:

most Inconsistency responses logically, the prg

should be considered valid. Because the in:

tency threshold on this scale is quite high,

adjustments should be rare.

Negativity Scale

‘The Negativity scale measures the extent to

the respondent answers selected BRIEF items

unusually negative manner relative to the cl

samples. Items comprising the Negativity &

along with cumulative percentiles from the cl

sample for the Parent and Teacher Forms are oS

in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. A higher raw scd

this scale indicates a greater degree of nega®

with less than 3% of respondents in the clinical

ple scoring above 7 on the Parent and ‘Te!

Forms. As with the Inconsistency scale, 7’ scor®

not generated for this scale. Scores of 5 or

should be considered elevated and a cause for o£

review of the protocol. Scores at or above 7

reflect either an excessively negative percepti

. Table 2

ltem Pair Correlations and Cumulative Percentiles for Absolute Difference Scores

on the Inconsistency Scale of the BRIEF Parent Form

Description Item Description t

M7. Has explosive, angry outbursts 25, Has outbursts for little reason 73

Does not bring home homework, 22, Forgets to hand in homework, even when

© assignment sheets, materials, etc. completed 64

1. Needs help from adult to stay on task 17. Has trouble concentrating on chores,

j schoolwork, ete 66

When sent to get something, forgets what 82, Forgets what he/she was doing 66

he/she is supposed to get

Acts wilder or sillier than others in groups 59. Becomes too silly 66

Interrupts others 65. Talks at the wrong time 70

Does not notice when his/her behavior causes 63. Does not realize that certain actions

negative reactions bother others 76

. Gets out of control more than friends y 54, Acts too wild or “out of control” 76

63. Written work is poorly organized 60. Work is sloppy 67

5. Has trouble putting the brakes on his/her actions 44, Gets out of control more than friends ry

Inconsistency Cumulative Protocol

score percentile classification

<6 ‘Acceptable

7to8 Questionable

2 Tneonsistent,

Based on total clinical sample (n = 852).

he child or that the child may have substantial

F executive dysfunction,

If the Negativity scale score is high, then the

examiner should consider the possibility that the

respondent had an unusually negative response style

that skewed the BRIEF results. It is also possible,

® however, that the BRIEF results represent accurate

reporting on a child with severe executive dysfunc-

tion. An elevated Negativity scale score should

prompt the examiner to” carefully review BRIEF’

results in the context ol FSU RRA aE Te

child, including BRIEF respons

ants, other test perfor

observations of the child. On the Parent Form, four”

of the nine items comprising the Negativity scale are

from the Shift scale. The possibility of significant

cognitive rigidity in the child should be considered as

scale score, particularly if the child has a diagnosis of

Pervasive Developmerital Disorder (PDD) or another

tirbttttittibttitbdbitithtchdtttitttt-tttt teeter er TE TTLTIT LLL ELL LLL ri

ai alternative explanation fora high. Negativity —

ote. r = correlation between the two items comprising each item pair.

neurological disorder where inflexibility is a promi-

nent symptom (e.g., severe traumatic brain injury).

Other Indications of Compromised Validity

As with any other assessment tool, it is essential

that the examiner consider the BRIEF results in the

context of other information about the child being

evaluated. Examiner observations of the child, his-

tory obtained from the parent, teacher reports, other

test results, and relevant medical and therapeutic

history are among the other sources of data that pro-

vide vital contextual information. Significant incon-

sistencies between the BRIEF results and any other

sources of information about the child are cause for

careful review, whereas corroborating evidence,

whether gathered in different modalities or from dif-

ferent respondents, increases confidence that the

findings are genuine.

It is also essential to carefully review information

relevant to the ability of the parent or teacher to

15

SOSH HHOHHEDIGOHOFOSO®

@eeeevoeoods

SOHOHOHOHHSHOHTSEHOBOOSS

Table 3

Item Pair Correlations and Cumulative Percentiles for Absolute Difference Scores

‘on the Inconsistency Scale of the BRIEF Teacher Form

tem Description Item Description

27. Mood changes frequently 26, Has outbursts for little reason

36, Leaves work incomplete 39, Has trouble finishing tasks (chores, homework)

42, Interrupts others 43, Is impulsive

45. Gets out of seat at the wrong times 9. Needs to be told “no” or “stop that”

46, Is unaware of own behavior when in a group 65. Does not realize that certain actions bother

others

47. — Gets out of control more than friends 58, Has trouble putting the brakes on his/her

actions

48. Reacts more strongly to situations than other children 66. Small events trigger big reactions

55. Talks or plays too loudly 57. Acts too wild or “out of control”

57. Acts too wild or “out of control” 46. _ Is unaware of own behavior when in a group

69. Does not think of consequences before acting 65. Does not realize that certain actions bother

others

ears ates nee ea nel ewe Sete Cotes

Inconsistency Cumulative Protocol

score percentile classification

a <98 ‘Acceptable

8 99 Questionable

29 299 Inconsistent

‘Note. r = correlation between the two items comprising each item pair.

Based on total clinical sample (

16

415),

Table 4

Negativity Scale Items and Cumulative Percentiles for

Clinical and Normative Respondents on the BRIEF Parent Form

item Description

8. Tries same approach to a problem over and over even when it does not work

13. Is disturbed by change of teacher or class

23. Resists change of routine, food, places, ete.

30, Has trouble getting used to new situations (classes, groups, friends)

62, Angry or tearful outbursts are intense but end suddenly

‘11. ‘Lies around the house a lot (“couch potato”)

80. ‘Has trouble moving from one activity to another

83. Cannot stay on the same topic when talking

85, Says the same things over and over

Total

Negativity Cumulative Protocol

score® percentile” classification

A $90 Acceptable

5 to6 91-98 Elevated

27 298 Highly elevated

Total number of items endorsed as “Often.” Based on total clinical sample (n = 852).

Table 5

Negativity Scale Items and Cumulative Percentiles for

Clinical and Normative Respondents on the BRIEF Teacher Form

Description

13. Acts upset by a change in plans

14, Is disturbed by change of teacher or class

24, Resists change of routine, food, places, ete.

Item

e 32, When sent to get something, forgets what he/she is supposed to get

a 64, Angry or tearful outbursts are intense but end suddenly

Fr 68. ‘Leaves a trail of belongings wherever he/she goes

a Tl. Leaves messes that others have to clean up

iz 82, Cannot stay on the same topic when talking

L— 84, Says the same things over and over

Ec Total

, Negativity Clinical Protocol

seore® sample? classification

<4 594 Acceptable

506 95 - 98 Elevated

2T 298 Highly elevated

END SC SE ch ee

Total number of items endorsed as “Often.” Based on total clinical sample (n = 475).

t the demands of completing the BRIEF rating

rm. The presence of a severe attention disorder,

ading skills below a fifth-grade level, and lack of

jency in English are among the factors that can

.promise BRIEF results. Direct observation of the

sspondent, review of his or her (i.e., parental) edu-

ition and employment, and review of the completed

RIEF rating form are useful in assessing respon-

dent competency.

‘Omission of Items

When reviewing the completed rating form, look

or omissions in ratings. Two or more omissions on a

ale invalidates the derivation of a T score for that

ale. Missing responses for one or two items that

‘eontribute to a scale raw score should be assigned a

; score of 1 when calculating scale raw scores.

Unusual Patterns of Responses

‘The examiner should also scan the test form for

‘unusual patterns of responses, such as marking only

cone response (e.g., Never or Often) for all items, or

systematically alternating responses between Never,

® Sometimes, and Often. Further investigation of such

y potential response biases is warranted.

CLINICAL SCALES

The BRIEF clinical scales measure the extent to

which the respondent reports problems with differ-

ent types of behavior related to the eight domains of

executive functioning. The following sections describe

the content and interpretation of the clinical scales.

(See Table 1 for brief descriptions of the clinical

scales.)

Ainninit

‘The Inhibit scale assesses inhibitory control (i.e.,

the ability to inhibit, resist, or not act on an impulse)

and the ability to stop one’s own behavior at the

appropriate time,’ This is a well-studied behavioral

regulation function that is described by Barkley (1990)

and many others as constituting the core deficit in

ADHD, Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Type,

as described in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV; American Psychia-

tric Association, 1994), Barkley (1996, 1997), Burgess

(1997), and Pennington (1997) have also argued that

poor inhibition is more generally an underlying

deficit in executive dysfunction. Children who have

sustained a traumatic brain injury. frequently also

aw

SOBVVTV9VV0N

@2Veeed0e000

°

®

e

a

°

®

@

e

@

9

®

e

ee

eeooecene

exhibit disinhibited or impulsive behavior.

Caregivers and teachers often are particularly con-

cerned about the intrusiveness and lack of personal

safety observed with children wl

impulses well. Sich children may display high levels,

of physical activity, inappropriate physical responses

to others, a tendency to interrupt and disrupt group

activities, and a general failure to “look before leap-

ing” Evaluators observe the same problems, which

are often particularly evident on tasks requiring a

delayed response. BRIEF items related to inhibition

include: “Blurts things out” and “Acts too wild or out

of control.” Case Illustration 1 describes a child with

severe inhibition problems and ADHD, although sev-

eral other cases also relate weaknesses in this pri-

mary function.

The Inhibit scale can be useful as a diagnostic

indicator of ADHD, Combined Type (ADHD-C).

Given the relationships between the neuropsycholog-

ical construct of inhibition and the behaviors that

characterize ADHD-C, it is reasonable to expect the

BRIEF Inhibit scale to capture many of the everyday

behaviors that might suggest a diagnosis of ADHD-

C. Further in-depth discussion about the diagnostic

utility of the Inhibit scale can be found in chapter 5.

@Shitt

‘The Shift scale assesses the ability to move freely

from one situation, activity, or aspect of a problem to

another as the circumstances demand. Key aspects of

shifting include the ability to make transitions, prob-

Iem-solve flexibly, switch or alternate attention, and

change focus from one mindset or topic to another.

Mild deficits in the ability to shift compromise the

efficiency of problem solving, whereas more. severe

difficulties are reflected in perseverative behaviors.

Caregivers often describe children who have diffi-

culty with shifting as rigid or inflexible, Such child-

Ten often require consistent routines. In some cases,

children are described as being unable to drop cer-

tain topics of interest or unable to move beyond a

specific disappointment or unmet need. Confronting

a change in normal routine may elicit repetitive

inquiries about what is going to happen next or when

an expected but postponed event will occur. Other

children may have specific repetitive or stereotypic

behaviors that they are unable to stop. Clinical

evaluators may observe a lack of flexibility or cre-

ativity in problem solving and a tendency to try the

same wrong approach repeatedly despite negative

18

feedback about its efficacy. BRIEF items rela

shifting include: “Acts upset by a change in |

and “Thinks too much about the same t

Difficulty with shifting and susceptibility to

veration are described in a variety of clinical

involving brain damage and are also obsers

developmental disorders. The DSM-IV diagnos:

teria for the Pervasive Developmental Dis

(PDD) include poor shifting ability. Case Illust

4 (presented later in this chapter) involves 2

with a PDD who had a particular weakness in

ing, among other domains.

(QF motional Control

‘The Emotional Control seale addresses the

festation of executive functions within the em¢

realm and assesses a child’s ability to modulat

tional responses. Poor emotional control ¢

expressed as emotional lability or emotional)

siveness. Children with difficulties in this d

may have overblown emotional reactions to

ingly minor events. Caregivers, teachers, and

ators of such children may observe a child wh

easily or laughs hysterically swith small provo

ora child who has temper tantrums with fre

or sévérity that is not age appropriate. Exam

BRIEF items related to emotional control i

“Mood changes frequently” and “Has exp

angry outbursts.” Case Illustration 3 descr

child with poor emotional control

Qruitiate

‘The Initiate scale contains items relating to

ning a task or activity, as well as independent

erating ideas, responses, or problem-s

strategiesPoor initiation typically does not

noncompliance or disinterest. in a~specific

Children with initiation problems typically v

succeed at a task, but they. cannot..get.s

Caregivers of such children frequently repo:

culties with getting started on homework or

along with a need for extensive prompts or

order to begin a task or activity. In the context

chological assessment, initiation difficulties a1

demonstrated in the form of difficulty with w«

design fluency tasks, as well as a need for adc

cues from the examiner in order to begin ti

general. Initiation is often a significant prob

individuals with severe frontal lobe brain inju

Case Illustration 3) and children who have r

cranial radiation for the treatment of cancer.

related to initiation include: “Lies around the

ea lot (couch potato),” “Is not a self-starter,” and

to be told to begin a task even when willing.”

is important to rule out primary oppositional

favior as the likely factor when considering initia-

function may experience problems with initiation

secondary consequence. For example, children

are very poorly organized can become over-

elmed with large assignments or tasks; conse-

pntly they may have great difficulty beginning the

tems from this scale measure the capacity to hold

mation in mind for the purpose of completing a

Working memory is essential to carry out mul-

p activities, complete mental arithmetic, or fol-

complex instructions. Caregivers describe

ildren with weak working memory as having trou-

remembering things (e.g., phone numbers or

ections) even for a few seconds, losing track of

hat they are doing as they work, or forgetting what

ley are supposed to retrieve when sent on an

rand, Clinical evaluators may observe that a child

nnot remember the rules governing a specific task

en as he or she works on that task, rehearses infor-

nation repeatedly, loses track of what responses he

she has already given on a task which requires

pultiple answers, and struggles with mental manip-

ation tasks (e.g., repeating digits in reverse order)

r solving orally presented arithmetic problems with-

‘out writing figures down. Working memory weak-

esses are observed in a variety of clinical

populations with executive function deficits, and

they have been posited as a core or necessary compo-

“nent of executive dysfunction by Pennington (1997).

IRIEF items related to working memory include:

Forgets what he/she was doing” and “Has trouble

emembering things, even for a few minutes.” Case

Illustrations 5 and 6, among others, describe child-

ren with working memory weaknesses.

Integral to working memory is the ability to

» sustain performance and attention. Parents of child-

ren with difficulties in this domain report that the

children cannot, ‘stick to” an activity for_an age:

appropriate am amount it

tasks or. fail, to.complete tasks. Although the working

‘memory and ability to sustain have been conceptual

ized as distinct entities, behavioral outcomes of

these two domains are often difficult to distinguish.

Furthermore, based on the empirically driven scale

construction of the BRIEF, these two domains com-

prise one unified scale (see chapter 4).

Given the posited relationship between working

memory as an executive function and the diagnostic

criteria for ADHD, Predominantly Inattentive Type

(ADHD-D, the BRIEF Working Memory scale can be

clinically useful in assessing the presence or absence

of ADHD-I, Further in-depth discussion about the

diagnostic utility of the Working Memory scale can

be found in chapter 5.

(©Plan/Organize

‘The Plan/Organize scale measures the child’s abil-

ity to manage current and future-oriented task

demands. The plan component of this scale relates to

the ability to anticipate future events, set goals, and

lop appropriate steps ahead of t carry a

‘a-goAl.or end state and then, and then iatogially

‘or steps to

stringing an ae a series of steps. Caregivers and

teachers often describe planning in terms of a child’s

{ ability to start large assignments in a timely fashion

or ability to obtain in advance the correct tools or

materials for carrying out a project. Evaluators can

observe planning when a child is given a problem

requiring multiple steps (e.g., assembling a puzzle or

completing a maze). BRIEF items related to plan-

ning include: “Underestimates time needed to finish

tasks” and “Has trouble carrying out the actions

needed to reach goals (saving money for special item,

studying to get a good grade).”

‘The organizing component of this scale relates to

the ability to bring order to information and to appre-

ciate main ideas or key concepts when learning or

or written material. Organization also has a clerical

component that is expressed, for example, in the abil-

ity to efficiently scan a visual array or to keep track of

a homework assignment. Caregivers often describe

children with organizational. weakmesses as approach-

ing tasks in-a’Haphazard fashion, iain the forest

for-the trees,” having excellent ideas that they fail to

‘express on tests and written assignments, and being

easily overwhelmed by large amounts of information,

19

00 0000000000000 0008008800990 8000.9:0:9%:

SeCHCOHOOGSHOE OHSS

‘The way in which information is strategically organ-

ized can play a crucial role in how it is learned,

remembered, and retrieved. This is often observed in

the context of an evaluation that reviews learning

and memory abilities. Poor organization of newly

learned material can result in difficulty with retriev-

ing that material in free recall conditions, but much

better performance with recognition (multiple

choice) formats, BRIEF items related to organiza-

tion include: “Gets caught up in details and misses

the big picture” and “Becomes overwhelmed by large

assignments.”

The Plan/Organize scale was originally two sepa-

rate scales, based on their conceptualization as theo-

retically distinct entities in the literature. Again,

however, the empirical analysis of the item-scale

structure of the BRIEF, as derived from the norma-

tive and clinical data, indicated that the two scales

should be collapsed into one (see chapter 4). The

interrelationship of planning and organizing is clear;

thus, the derivation of one unified scale is reason-

able. Difficulty with organization and planning is

integral to many cases of executive dysfunction. Case

Tilustrations 2 and 5, among others, describe child-

ren with severe organizational deficits.

(SPreanization of Materials

The Organization of Materials scale measures

orderliness of work, play, and storage spaces (e.g.,

such as desks, lockers, backpacks, and bedrooms).

Although evaluators may not have an opportunity to

observe this problem directly, caregivers and teach-

ers typically can provide an abundance of examples

describing the difficulty children with executive dys-

function experience in organizing, keeping track of,

and/or cleaning up their possessions. The Organi-

zation of Materials scale assesses the manner in

which children order or organize their world and

belongings. Children who have difficulties in this

area often cannot function efficiently in school or at

home because they do not have their belongings

readily available for their use. Pragmatically, teach-

ing a child to organize his or her belongings can be

a useful, concrete tool for teaching greater task

organization. BRIEF items related to organization of

materials include “Has a messy closet” and “Leaves a

trail of belongings wherever he/she goes.” Case

Illustrations 2 and 5 describe children with deficits

in this area.

20

(@Monitor

‘The Monitor scale assesses work-checking

(ie., whether a child assesses his or her own,

formance during or shortly after finishing @ 4

ensure appropriate attainment of a goal). This, ?

also evaluates a personal monitoring ed

4

4

4

4

whether a child keeps track of the effect his

behavior has on others). Caregivers often di

problems with self-monitoring in children who,

low on the Monitor scale in terms of rushing tht

work, making careless mistakes, and failing to

work. Clinical evaluators can observe the same

of behavior during the assessment of such chil

BRIEF items related to self-monitoring in

“Does not realize that certain actions bother ot

and “Does not check work for mistakes.”

Illustrations 4 and 5 describe children with

monitoring difficulties.

Tue BEHAVIORAL REGULATION INI

THE METACOGNITION INDEX, AND '

GosaL Executive ComPosiT:

Based on theoretical and empirical factor at

findings (reviewed in chapter 5), the clinical

combine to form two Indexes, Behavioral Regu

and Metacognition, and one composite sun

score, the Global Executive Composite. The ¢

and interpretation of the two indexes and thi

posite summary score are discussed in the fol!

sections.

Behavioral Regulation Index

‘The Behavioral Regulation Index (BRD) repr

a child’s ability to shift, cognitive set and mo

emotions and behavior via appropriate inh

control. It is comprised of the Inbibit, Shit

Emotional Control scales. Appropriate beh:

regulation is likely to be a precursor to appr

metacognitive problem solving. Behavioral ;

tion enables the metacognitive processes to 8

fully guide active, systematic problem solvin

more generally, supports appropriate self-regv

Metacognition Index

‘The Metacognition Index (MI) represer

child’s ability to initiate, plan, organize, and :

future-oriented problem solving in working

‘This index is interpreted as the ability to cog:

dif manage tasks and reflects the child’s ability to

Monitor his or her performance. The MI relates