Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Basho 2

Basho 2

Uploaded by

coilCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Answe Key Fall of The House of UsherDocument6 pagesAnswe Key Fall of The House of UsherGhena HamwiNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Poetry of Matsuo BashoDocument7 pagesAnalysis of The Poetry of Matsuo BashoMervyn Larrier100% (11)

- Harold Bloom (Editor) - Tony Kushner (Blooms Modern Critical Views) - Chelsea House Publishers (2005)Document206 pagesHarold Bloom (Editor) - Tony Kushner (Blooms Modern Critical Views) - Chelsea House Publishers (2005)Ana Maria Andronache100% (1)

- Cats in Spring Rain: A Celebration of Feline Charm in Japanese Art and HaikuFrom EverandCats in Spring Rain: A Celebration of Feline Charm in Japanese Art and HaikuNo ratings yet

- 12 8 Poem SpacecatDocument4 pages12 8 Poem Spacecatapi-571883491No ratings yet

- None Is Travelling-Basho MatsuoDocument11 pagesNone Is Travelling-Basho MatsuoRidhwan 'ewan' RoslanNo ratings yet

- Sastra Bandingan 2Document11 pagesSastra Bandingan 2Vhiiettd_aciuhmaNo ratings yet

- Women and The Rise of The Novel, 1405-1726: Josephine DonovanDocument191 pagesWomen and The Rise of The Novel, 1405-1726: Josephine DonovanHaneen Al IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Literature of JapanDocument6 pagesLiterature of Japanmaria yvonne camilotesNo ratings yet

- The Main Theme of BashoDocument4 pagesThe Main Theme of BashoANGELA V. BALELANo ratings yet

- Basho The Complete Haiku IntegralaDocument492 pagesBasho The Complete Haiku IntegralaShubhadip AichNo ratings yet

- Classic Haiku: An Anthology of Poems by Basho and His FollowersFrom EverandClassic Haiku: An Anthology of Poems by Basho and His FollowersRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Matsuo BashoDocument5 pagesMatsuo BashoMaria Angela ViceralNo ratings yet

- Matsuo Basho COMPLETE NOTESDocument3 pagesMatsuo Basho COMPLETE NOTESshanid.saudiaNo ratings yet

- Basho's Narrow Road: Spring and Autumn PassagesFrom EverandBasho's Narrow Road: Spring and Autumn PassagesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (18)

- HAIKU BASHO AND BUSON - DesalizaDocument16 pagesHAIKU BASHO AND BUSON - DesalizaJoshua Lander Soquita Cadayona100% (1)

- DGL, LunberryCMS2019LDocument14 pagesDGL, LunberryCMS2019LcoilNo ratings yet

- Beginner's Guide to Japanese Haiku: Major Works by Japan's Best-Loved Poets - From Basho and Issa to Ryokan and Santoka, with Works by Six Women Poets (Free Online Audio)From EverandBeginner's Guide to Japanese Haiku: Major Works by Japan's Best-Loved Poets - From Basho and Issa to Ryokan and Santoka, with Works by Six Women Poets (Free Online Audio)Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- OkayDocument3 pagesOkayashley cagadasNo ratings yet

- Basho's HokkuDocument4 pagesBasho's HokkuxibmabNo ratings yet

- HaikuDocument12 pagesHaikuAlphanso BarnesNo ratings yet

- Blyth On BashoDocument189 pagesBlyth On BashoMarko Mlinaric100% (1)

- On Love and Barley Haiku of Basho Matsuo - BashōStryk LucienDocument81 pagesOn Love and Barley Haiku of Basho Matsuo - BashōStryk Luciencalisto.aravena.zNo ratings yet

- Haiku: History of The Haiku FormDocument8 pagesHaiku: History of The Haiku FormKim HyunaNo ratings yet

- Blyth On BashoDocument189 pagesBlyth On BashojohNo ratings yet

- Matsuo Basho 2004 9Document121 pagesMatsuo Basho 2004 9arpitaNo ratings yet

- The Poet Vanishes Haiku by Chiyo Basho ADocument4 pagesThe Poet Vanishes Haiku by Chiyo Basho AwilliamcoymNo ratings yet

- (Japan) BashoDocument4 pages(Japan) BashoEhrykuh MaeNo ratings yet

- Matsuo Bashō - WikipediaDocument38 pagesMatsuo Bashō - Wikipediagolden wingsNo ratings yet

- HaikuDocument25 pagesHaikuKim HyunaNo ratings yet

- Basho HaikuDocument3 pagesBasho HaikusatoriasNo ratings yet

- Peipei Qiu - Celebrating Kyo: The Eccentricity of Basho and NampoDocument8 pagesPeipei Qiu - Celebrating Kyo: The Eccentricity of Basho and NampoHaiku NewsNo ratings yet

- ShiraneDocument16 pagesShiraneAlina Diana Bratosin100% (1)

- UntitledDocument6 pagesUntitledBill BensonNo ratings yet

- Haiku: Japanese LiteratureDocument14 pagesHaiku: Japanese LiteratureNestle Anne Tampos - TorresNo ratings yet

- Haiku Poem: Basho MatsuoDocument2 pagesHaiku Poem: Basho MatsuoMitchel BibarNo ratings yet

- Final Draft - Alexis LapidDocument5 pagesFinal Draft - Alexis Lapidapi-225280405No ratings yet

- Bashu Haiku PDFDocument44 pagesBashu Haiku PDFDavid Jaramillo KlinkertNo ratings yet

- Japane 351 PaperDocument8 pagesJapane 351 PaperAnthony M. WoodNo ratings yet

- Bashō, in Full Matsuo Bashō, Pseudonym of Matsuo Munefusa, (Born 1644, Ueno, Iga ProvinceDocument1 pageBashō, in Full Matsuo Bashō, Pseudonym of Matsuo Munefusa, (Born 1644, Ueno, Iga ProvinceAraNo ratings yet

- HaikuDocument1 pageHaiku서재배No ratings yet

- Haiku and Noh: Journeys To The Spirit World: Between Two WorldsDocument10 pagesHaiku and Noh: Journeys To The Spirit World: Between Two WorldsTsutsumi ChunagonNo ratings yet

- HAIKUDocument24 pagesHAIKUAllan Joy H. CaoileNo ratings yet

- 176 The Making of Modern JapanDocument1 page176 The Making of Modern JapanCharles MasonNo ratings yet

- On The Road AgainDocument3 pagesOn The Road Againfcrocco100% (2)

- A Definition of HaikuDocument13 pagesA Definition of HaikuKent DorseyNo ratings yet

- Finalreadingjournal 4Document4 pagesFinalreadingjournal 4api-518643296No ratings yet

- Haiku PoemsDocument4 pagesHaiku PoemsRebecca HayesNo ratings yet

- Basho's HaikusDocument5 pagesBasho's HaikusSaluibTanMelNo ratings yet

- The Old Pond by Matsuo BashoDocument8 pagesThe Old Pond by Matsuo Bashoemerine casonNo ratings yet

- Masako K. Hiraga, Eternal StillnesDocument15 pagesMasako K. Hiraga, Eternal StillnesparadoyleytraNo ratings yet

- MatsuoipediaDocument21 pagesMatsuoipediaBalayya PattapuNo ratings yet

- Poems - HaikuDocument2 pagesPoems - HaikuMabel BaybayonNo ratings yet

- HaikuDocument16 pagesHaikuMaria Kristina EvoraNo ratings yet

- Haiku SamplesDocument2 pagesHaiku SamplesKamoKamoNo ratings yet

- LevelUP Ready - Values Affirmation ActivityDocument5 pagesLevelUP Ready - Values Affirmation ActivitycoilNo ratings yet

- Rough (Final) Draft Junior Research PaperDocument8 pagesRough (Final) Draft Junior Research PapercoilNo ratings yet

- Scientific Reasoning AssignmentDocument2 pagesScientific Reasoning AssignmentcoilNo ratings yet

- Dataslate ImperialisDocument26 pagesDataslate ImperialiscoilNo ratings yet

- Calc+Unit+Organizer+-+7 1-7 2Document2 pagesCalc+Unit+Organizer+-+7 1-7 2coilNo ratings yet

- 7 2+Notes+-+Disk+MethodDocument2 pages7 2+Notes+-+Disk+MethodcoilNo ratings yet

- DGL, LunberryCMS2019LDocument14 pagesDGL, LunberryCMS2019LcoilNo ratings yet

- SigvaldAereus 58802402Document4 pagesSigvaldAereus 58802402coilNo ratings yet

- 7 2+Notes+-+Washer+MethodDocument2 pages7 2+Notes+-+Washer+MethodcoilNo ratings yet

- Volume: Disk Method WKSHTDocument2 pagesVolume: Disk Method WKSHTcoilNo ratings yet

- 7 1+7 2+Area+and+Volume+ (Disk) +practice+answersDocument2 pages7 1+7 2+Area+and+Volume+ (Disk) +practice+answerscoilNo ratings yet

- Act 4 QuestionsDocument1 pageAct 4 QuestionscoilNo ratings yet

- 5.5 NotesDocument2 pages5.5 NotescoilNo ratings yet

- Japanese Vs Chinese Characters SourcdDocument24 pagesJapanese Vs Chinese Characters SourcdcoilNo ratings yet

- Peer Review FormDocument2 pagesPeer Review FormcoilNo ratings yet

- CH 6 Notes 1 - Solving DEDocument2 pagesCH 6 Notes 1 - Solving DEcoilNo ratings yet

- Holy OrdersDocument2 pagesHoly OrderscoilNo ratings yet

- Outline For Jane Eyre EssayDocument2 pagesOutline For Jane Eyre EssaycoilNo ratings yet

- Bashō As BatDocument18 pagesBashō As BatcoilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Review AnswersDocument4 pagesChapter 5 Review AnswerscoilNo ratings yet

- Elie Wiesel Quote ActivityDocument2 pagesElie Wiesel Quote ActivitycoilNo ratings yet

- John Marshall - The ManDocument6 pagesJohn Marshall - The MancoilNo ratings yet

- AP Song ActivityDocument4 pagesAP Song ActivitycoilNo ratings yet

- Brave New World Chapters 13Document2 pagesBrave New World Chapters 13coilNo ratings yet

- Slides 2022Document18 pagesSlides 2022coilNo ratings yet

- Brave New World Paired PoemsDocument5 pagesBrave New World Paired PoemscoilNo ratings yet

- MS Chapter 5 Notes LOOPDocument9 pagesMS Chapter 5 Notes LOOPcoilNo ratings yet

- Brave New World Chapters 7:8Document2 pagesBrave New World Chapters 7:8coilNo ratings yet

- Phylum Ctenophora and Simple WormsDocument4 pagesPhylum Ctenophora and Simple WormscoilNo ratings yet

- Phylum Echinodermata Notes and ChartDocument5 pagesPhylum Echinodermata Notes and ChartcoilNo ratings yet

- Rizal Midterm ReviewerDocument16 pagesRizal Midterm Reviewerblahblahblacksheep76No ratings yet

- Revision For Unit 1,2,3Document9 pagesRevision For Unit 1,2,3Pham ThuhienNo ratings yet

- العلاقات السياسية بين إيالة الجزائر العثمانية وإنجلترا قراءة من خلال الكتابات الفرنسية في المجلة الإفريقيةDocument22 pagesالعلاقات السياسية بين إيالة الجزائر العثمانية وإنجلترا قراءة من خلال الكتابات الفرنسية في المجلة الإفريقيةonlymen0001No ratings yet

- Samuel Beckett, Repetition and Modern Music - John McGrath - 2017 - Anna's ArchiveDocument191 pagesSamuel Beckett, Repetition and Modern Music - John McGrath - 2017 - Anna's ArchiveDavide PentassugliaNo ratings yet

- Brush Up Your Poetry!Document259 pagesBrush Up Your Poetry!Aditya AmatyaNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Romeo and Juliet PDFDocument174 pagesShakespeare Romeo and Juliet PDFgoranstojanovicscribNo ratings yet

- Living in Subalterinity: The Voiceless Others in Nadine Gordimer's Selected Short StoriesDocument7 pagesLiving in Subalterinity: The Voiceless Others in Nadine Gordimer's Selected Short StoriesIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Maitreya in MrichchhakatikaDocument2 pagesMaitreya in Mrichchhakatikaxoh23028No ratings yet

- Glyn's Haunted House Halloween Crossword: Across DownDocument2 pagesGlyn's Haunted House Halloween Crossword: Across DownAna SilvaNo ratings yet

- Alice in WonderlandDocument65 pagesAlice in WonderlandshiyizhuNo ratings yet

- Estelle de Koning - Female Agency in The NibelungenliedDocument51 pagesEstelle de Koning - Female Agency in The NibelungenliedKarina AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Anapa Ne: Anwumme-S3ReDocument91 pagesAnapa Ne: Anwumme-S3ReBangmeyiri VitalisNo ratings yet

- SS23 Catalog Copper Canyon PressDocument12 pagesSS23 Catalog Copper Canyon PresshoneromarNo ratings yet

- Bonku Babu NotesDocument15 pagesBonku Babu NotesThe Two side ShowNo ratings yet

- Biomedical Engineering Society, BangladeshDocument1 pageBiomedical Engineering Society, BangladeshDr. Mohammad Nazrul IslamNo ratings yet

- La Biblia de KolbrinDocument599 pagesLa Biblia de KolbrinAngel Marín VargasNo ratings yet

- ReflectionDocument5 pagesReflectionTesalonicaNo ratings yet

- Excursion Proposal FormDocument1 pageExcursion Proposal Formapi-397550031No ratings yet

- Shabbir Dhondhte Rahe Pyare Gaye KahaDocument4 pagesShabbir Dhondhte Rahe Pyare Gaye Kahammmurtaza100% (1)

- Instructions: Recall What You Learned About Poetry. Read and Answer TheDocument4 pagesInstructions: Recall What You Learned About Poetry. Read and Answer Thesonny mark cabangNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnDocument3 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry FinnCrina Mitran100% (1)

- 3RD Quiz in CNFDocument5 pages3RD Quiz in CNFRica Mel MaalaNo ratings yet

- T. S. Eliot-DanteDocument17 pagesT. S. Eliot-DanteПавле ЛучићNo ratings yet

- Course Outline (English 10 S.Y. 2021-2022)Document6 pagesCourse Outline (English 10 S.Y. 2021-2022)Tracia Mae Santos BolarioNo ratings yet

- What Made The Masses Revolutionary Ignorance Character and CLDocument24 pagesWhat Made The Masses Revolutionary Ignorance Character and CLJEN CANTOMAYORNo ratings yet

- Persusaive EssayDocument5 pagesPersusaive Essayb72hvt2d100% (2)

Basho 2

Basho 2

Uploaded by

coilOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Basho 2

Basho 2

Uploaded by

coilCopyright:

Available Formats

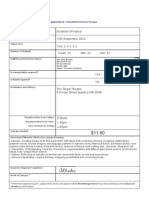

Chapter Title: Matsuo Bashō

Chapter Author(s): Donald Keene

Book Title: Finding Wisdom in East Asian Classics

Book Editor(s): Wm. Theodore de Bary

Published by: Columbia University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/deba15396.28

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Columbia University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Finding Wisdom in East Asian Classics

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

21(b)

Matsuo Bashō

Donald Keene

B ashō is the best-known Japanese poet not only in his own country

but throughout the world. About a thousand of his haiku survive, a

relatively scant output for someone who spent most of his life as a haiku

poet; a professional Japanese haiku poet today would not fi nd it diffi cult

to turn out that many poems in a single year. Haiku, at fi rst glance, seems

extremely easy to compose—all one has to do is arrange a bare seventeen

syllables into three lines of five, seven, and five syllables. The ease of compo-

sition att racts many Japanese today. It is estimated that a million amateurs

belong to haiku groups, each headed by a recognized master. They regularly

meet, and the haiku they compose are published in the group’s magazine.

Yet of the many tens of thousands of haiku composed by such groups each

year, probably not more than a handful will be remembered the following

year. It is tempting to say that composing a successful haiku, far from being

easy, is unusually difficult. Not a word—not even a syllable—can be wasted,

and, while obeying certain conventions, it must seem refreshingly new.

The restriction on the number of syllables tends to make a haiku difficult

to understand, because words necessary for ready comprehension have

been omitted. The poet, whatever he wishes to communicate, must depend

on the reader to intuit and complete what he has not overtly expressed.

Sometimes a haiku is prefaced by a title or by a brief statement of the cir-

cumstances of the composition that makes it easier to comprehend. For

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

288 Matsuo Bashō

example, the travel diary Exposed in the Fields (Nozarashi Kikō), written by

Bashō in 1684, contains this haiku:

te ni toraba kien Taken in my hand it would melt

namida zo atsuki My tears are so hot—

aki ni shimo Th is autumnal frost.

One notes fi rst of all that the initial line is in eight instead of the pre-

scribed five syllables. Bashō rarely violated the syllable count unless

something in a poem was of such importance to him that he simply had to

break the rules. Th is haiku, then, probably had a special meaning for

Bashō. But why, we may wonder, should he have taken frost into his hand,

and why did it make him weep? Without help from the poet, the reader is

likely to be puzzled, though he may be moved even by the literal sense of

the words—the poet takes in his hand a very easily perished substance,

and its disappearance makes him weep. But if one knows the circum-

stances that inspired Bashō to write the haiku, it becomes far more affect-

ing. Just before he wrote the haiku in his diary, Bashō related that he had

returned to his home in Iga after spending ten years in Edo: “At the begin-

ning of the ninth month I returned to my old home. The day lilies in the

northern hall had been withered by the frost, and there was no trace of

them now. My brother’s hair was white at the temples and his brow was

wrinkled. ‘We are still alive,’ he said. ‘Pay your respects to Mother’s white

hairs!’ ”

It is clear from this passage that the “autumnal frost” was a lock of the

white hair of Bashō’s mother, who had died the previous year. That is why

his tears were so hot. But why did he mention the day lilies that had with-

ered in the northern hall? Commentators inform us that it was customary

for an aged mother to live in the northern wing of a house, and that such

women, relieved of household duties, frequently cultivated plants such as

day lilies. Bashō’s reference to the day lilies also alluded to Chinese poems

that mentioned them in the same connection. Such an allusion was not an

affectation; Bashō, by linking his grief to the grief expressed by poets in

China on losing their mother, deepened his own experience.

If one is unfamiliar with the Chinese and Japanese writings to which

Bashō at times alluded, some haiku will seem obscure, but the use of allu-

sions was one way of surmounting the limitations of seventeen syllables. A

few key words, borrowed from a poem of the past, could expand a haiku by

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Matsuo Bashō 289

reference to the content of a predecessor’s work. It is possible to enjoy even

such haiku without knowledge of the allusions, but if they are understood

we can appreciate the additional richness that has been obtained.

Bashō’s haiku may be ambiguous even when the surface presents no ap-

parent problem of interpretation. His most famous haiku seems absolutely

clear:

furuike ya The old pond

kawazu tobikomu A frog jumps in

mizu no oto The sound of water.

Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902), the celebrated poet and critic of haiku, in-

sisted that “the meaning of the haiku about the old pond is nothing more

than what appears on the surface; there is no other meaning.” Shiki’s pre-

ferred stance when composing haiku was to describe as objectively as pos-

sible what he observed or felt without borrowing overtones from the litera-

ture of the past. Th is accounts for his belief that Bashō’s haiku on the frog, a

poem he admired, contained no more than what appears on the surface.

But this haiku lends itself to other interpretations. The first line, for example,

is perfectly clear but if carefully considered is rather puzzling. Why should

Bashō have felt it necessary to stipulate that the pond was old? Is not every

pond old? Why should he have wasted two precious syllables on the adjec-

tive furu (“old”)? It may be because Bashō wanted to emphasize the unchang-

ing nature of the pond, which gives the haiku its quiet, horizontal base.

Suddenly a frog jumps into the pond, a vertical intersection of the unchang-

ing by the momentary, marked by the splash of the water that defi nes both.

Is that what Bashō actually had in mind? If so, did he hope that we would

share with him the epiphany brought on by the sound of the water? Shiki

declared that “the special feature of this haiku is that it hides nothing, does

not use the slightest artifice, has not one word that is broken or twisted.”

We may disagree.

Kagami Shikō, one of Bashō’s disciples, related how Bashō happened to

compose this haiku: “It was just the kind of day when one most regrets the

passing of spring. The sound of frogs leaping into the water could frequently

be heard, and the Master, moved by the remarkable beauty of the scene,

wrote the second and third lines of a haiku describing it. . . . Kikaku, who

was with him, suggested as a fi rst line ‘The yellow roses,’ but the Master

sett led on ‘The old pond.’ ” If this account is to be trusted, not one but many

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

290 Matsuo Bashō

frogs jumped in, repeated violations of the peacefulness of the sett ing. We

will never know Bashō’s intention, but such ambiguity is part of the appeal

of his poetry.

A line in a haiku by Bashō can be often be interpreted in different ways:

kareeda ni On the withered branch

karasu no tomarikeri A crow has alighted—

aki no kure Nightfall in autumn.

Does the last line mean “nightfall in autumn” or “the last [days] of autumn”?

Either or both are possible. The crow that has alighted on the withered

branch is the “now” of the poem, and its dark presence is equated with the

coming of night in autumn. But surely it is not a twilight in early or mid-

autumn, when the bright red leaves always associated with this season in

Japanese poetry were at their height. The season is the end of autumn, when

the red leaves have scattered, leaving bare branches. The scene is in mono-

chrome: a black crow has perched on a whitened branch at the time of day

and in the season of year when colors disappear. The long middle line sug-

gests that Bashō suddenly realized that the moment the crow alighted on

the withered branch a day and a season had ended.

Even in translation many of Bashō’s haiku can be enjoyed, but the loss of

the original sounds deprives the reader of a part of the meaning. The sounds

of the previous haiku, especially the k-r consonants in the words kareeda,

karasu, and kure, add to the darkness of the mood.

A celebrated haiku makes use of the special, mournful sound of the

vowel o, rather in the manner of Edgar Allen Poe:

natsukusa ya The summer grasses—

tsuwamonodomo ga For many brave warriors

yume no ato The aftermath of dreams.

Here the repeated o sounds (six of the seventeen syllables) create a solem-

nity that underlines the sadness of the death of brave warriors.1 Another

haiku describes silence in sound:

shizukesa ya How still it is!

iwa ni shimiiru Stinging into the stones,

semi no koe The locusts’ trill.

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Matsuo Bashō 291

Only through sound can silence be known. The stillness of the mountains

is interrupted by the prolonged din of the cicadas, but when they stop, the

silence is overpowering. In this haiku, the vowel i occurs seven times out of

seventeen in the poem. The i is the sound of the cicadas.

Four stages of this haiku have been preserved. They suggest Bashō’s dis-

satisfaction even with versions that other poets would be delighted to have

composed.2 The fi rst was:

yamadera ya Mountain temple—

ishi ni shimitsuku Seeping into the stones

semi no koe Cicada voices.

Yamadera, the popular name of the Risshakuji, is a temple in Yamagata that

Bashō visited, but yamadera otherwise means “mountain temple,” the scene

of the haiku. The term shimitsuku is used to describe a liquid seeping into

another substance. The haiku says that the cries of the cicada permeate the

stones. The second version is stronger:

sabishisa ya What loneliness—

iwa ni shimikomu Penetrating the rocks

semi no koe Cicada voices.

Loneliness was akin to the medieval concept of sabi. It was not necessarily

disagreeable; the Buddhist monk found peace in solitude. The verb shimikomu

is more intense than shimitsuku, penetrating rather seeping into the boulders.

The rocks are also more impressive than the stones of the first version. But

Bashō was still not satisfied. The third version was:

sabishisa no Into the loneliness

iwa ni shimikomu Of the rocks penetrate

semi no koe Cicada voices.

Here the loneliness is not the general atmosphere of the landscape but a

condition fostered by the rocks. Bashō’s fourth and fi nal version reads:

shizukesa ya How still it is!

iwa ni shimiiru Into the rocks stab

semi no koe Cicada voices.

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

292 Matsuo Bashō

The substitution of shizukesa ya for sabishisa ya was crucial. Loneliness was

a conventional topic of poetry, but mentioning silence, despite the din of

the cicadas, was a masterstroke. The verb shimiiru is the strongest of all. It

suggests that the cries of the cicada do not merely penetrate the rocks but

stab deep into them.

Bashō’s haiku include various examples of synesthesia, the transference

of an impression from one sense to another:

Kiku no ka ya Chrysanthemum scent—

Nara ni wa furuki And in Nara all the old

hotoke tachi Statues of Buddha.

The musty scent of chrysanthemums is equated with the dusty, peeling

statues in the old temples but also with Nara, a city living in its past. Scent

and sight are interchanged. Bashō composed this haiku at the time of the

chrysanthemum festival in the ninth month. It thus evokes both the time of

composition and the musty past.

The senses of sight and hearing are joined in another haiku:

Umi kurete The sea darkens—

kamo no koe The voices of the seagulls

honoka ni shiroshi Are faintly white.

Here, the cries of the seagulls against the black sky seem like flashes of light.

To create such poems was not easy, even for Bashō. In his Sarashina

Diary, he related how, as he lay one night in his room at an inn, he attempted

to beat into shape the poetic materials he had garnered during the day, groan-

ing and knocking his head in the effort. A priest, imagining that Bashō was

suffering from a fit of depression, tried to comfort him with stories about

the miracles of Amida Buddha, who had vowed to save all men, but he only

succeeded in blocking Bashō’s flow of inspiration. Groaning and knocking

probably accompanied the creation of many of his haiku. The successive

revisions he made to the wording and even the underlying meaning of a haiku

enable us to trace his efforts to reach the exact center of the perception he

described.

Not all of Bashō’s haiku were polished and revised. If, during his travels,

he was a guest at someone’s house or at a temple, he felt obliged to compose

a haiku of salutation and thanks, rather like signing a guest book. Such

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Matsuo Bashō 293

haiku were dashed off easily and seldom revised, but they too have charm.

At the house of a rich man, his host in Obanasawa, Bashō wrote:

suzushisa wo Making the coolness

wa ga yado ni shite My abode, here I lie

nemaru nari Completely at ease.

Bashō mentioned coolness as a compliment to a host whose house was

pleasantly cool in the summer. He and the host had not previously met, but

he felt completely at home, as he conveyed by using the word nemaru, from

the local dialect, meaning to rest comfortably. The use of this word may

have indicated his hope he might converse with the host as intimately as

someone who spoke the same dialect.

During his Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to Oku) journey, Bashō

composed poems at almost every place he stopped, but not at Matsushima,

the place he most wanted to see. He related at the outset, while making

preparations for travel: “To strengthen my legs for the journey I had moxa

burned on my shins. By then I could think of nothing but the moon at Mat-

sushima.” On arrival, however, Bashō seems to have been stunned into

silence by its beauty. Th is was not his only such experience. During his trav-

els he passed Fuji many times, but his only haiku on the mountain was:

kiri shigure Fog and rain showers:

Fuji wo minu hi zo A day one can’t see Fuji

omoshiroki Is interesting.

Although Bashō did not compose a haiku at Matsushima, his prose de-

scription is a highlight of the diary:

No matter how often it has been said, it is nonetheless true that the

scenery of Matsushima is the fi nest in Japan, in no way inferior to

Tung-ting or the West Lake in China. The sea flows in from the south-

east forming a bay seven miles across, and the incoming tide surges in

massively, just as in Zhe-zhiang. There are countless islands. Some

rise up and point at the sky; the low-lying ones crawl into the waves.

There are islands piled double or even stacked three high. To the left

the islands stand apart; to the right they are linked together. Some

look as if they carried litt le islands on their backs, others as if they

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 Matsuo Bashō

held the islands in their arms, evoking a mother’s love of her children.

The green of the pines is of a wonderful darkness, and their branches

are constantly bent by winds from the sea, so that their crookedness

seems to belong to the nature of the trees. . . . What man could capture

in a painting or a poem the wonder of this masterpiece of nature?

Somewhat later in the journey, Bashō visited Kisagata, a place of great

scenic beauty where, recalling Matsushima, a great number of islands were

scattered in the sea. Here he composed this haiku:

Kisagata ya Kisagata—

ame ni Seishi ga Seishi sleeping in the rain,

nebu no hana Mimosa blossoms.

Th is haiku, in the manner of older schools, has a pun at its core. The word

nebu (or nemu) means “to sleep” and is used in this sense with what pre-

cedes—Seishi is sleeping. But its homonym means “mimosa,” and that goes

with what follows—mimosa blossoms. The pun was not intended to be hu-

morous but to add to the complexity. Bashō had been dazzled at Matsu-

shima by its unclouded beauty. Now he is at Kisagata. It is an equally lovely

place, but seen in the rain it is somehow melancholy. The sight recalls Seishi

(Xi Shi), a pensive Chinese lady who was famous for her seductive frowns.

Mimosa, a delicate summer flower, recalls the delicate Seishi.

Some haiku are openly funny:

natsugoromo My summer clothes—

imada shirami wo I still haven’t quite fi nished

toritsukusazu Picking out the lice.

There are probably no hidden meanings behind this haiku!

Toward the end of his life, Bashō insisted on the importance of “light-

ness” (karumi). The term seems to have meant simplicity, as opposed to the

complexity of the haiku like the one about Seishi. His last few haiku, com-

posed shortly before his death, are plainly expressed and almost unbearably

moving.

kono michi wa Along this road

yuku hito nashi ni There are no travelers—

aki no kure Nightfall in autumn.

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Matsuo Bashō 295

kono aki wa Th is autumn

nan de toshi yoru Why do I feel so old?

kumo no tori A bird in the clouds.

aki fukaki Autumn has deepened:

tonari wa nani wo I wonder what the man next door

suru hito zo Does for a living.

tabi ni yande Stricken on a journey

yume wa kareno wo My dreams go wandering about

kakemeguru Desolate fields.

These haiku are almost entirely in the colloquial language. Bashō, at the

very end of his life, seems to have rejected the literary language of his ear-

lier poems. These are so direct and unadorned as to be almost painfully

beautiful.

Bashō is celebrated not only for his haiku but for his poetic prose. In-

deed, the fi ft h of his travel diaries, Oku no hosomichi (The Narrow Road to

Oku), is probably the most widely read work of Japanese classical literature,

although all five diaries rank as masterpieces of “diary literature,” a pecu-

liarly Japanese genre. In no other country has the diary played so important

a part, from the fi rst examples in the ninth century to the present. In Bashō’s

third travel diary, Oi no Kobumi (Manuscript in My Knapsack), written in

about 1690, he acknowledged his debt to his predecessors, the diary writers

of the past:

Nobody has succeeded in making any improvements in travel diaries

since Ki no Tsurayuki, Chōmei, and the nun Abutsu wielded their

brushes to describe their emotions to the full; the rest have merely

imitated. How much less likely it is that anyone of my shallow knowl-

edge and inadequate talent could do better. Of course, anyone can

write in a diary, “On that day it rained . . . it cleared in the afternoon . . .

there is a pine at that place . . . the such-and-such river flows through

this place,” and the like, but unless a sight is truly remarkable one

shouldn’t mention it at all. Nevertheless, the scenery of different places

lingers in my mind, and even my unpleasant experiences at huts in the

mountains and fields can become subjects of conversation or material

for poetry. With this in mind I have scribbled down, without any sem-

blance of order, the unforgettable moments of the journey, and gathered

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

296 Matsuo Bashō

them together in one work. Let the reader listen without paying too

much attention, as to the ramblings of a drunkard or the mutterings of

a man in his sleep.

Bashō’s fi rst four travel diaries, though defi nitely not the ramblings of a

drunkard, may seem unfi nished despite their beauty, because the prose and

the haiku have not been well blended. Bashō had yet to acquire his mastery

of the art of combining in a seamless manner events of a journey with the

haiku composed on the way. The Narrow Road to Oku, his account of a jour-

ney to the northern provinces in 1689, took him four years to write, even

though in a modern edition it runs to perhaps twenty-five pages. Undoubt-

edly Bashō revised the text many times before he was willing to let it out of

his hands.

The work opens with a celebrated passage:

The months and days are the travelers of eternity. The years that come

and go are also voyagers. Those who float away their lives on ships

or who grow old leading horses are forever journeying, and their

homes are wherever their travels take them. Many of the men of old

died on the road, and I too for years past have been stirred by the sight

of a solitary cloud drift ing with the wind to ceaseless thoughts of

roaming.

The opening words were adapted from a work by Li Bo, but nobody con-

sidered this plagiarism. On the contrary, such borrowing was not only tol-

erated but deemed essential; a literary work without allusions seemed light-

weight. But The Narrow Road to Oku is not a pastiche assembled from the

writings of the great poets of the past; it is the record of an actual journey,

and people today still follow Bashō’s footsteps along his course, though

the passage of three hundred years has obliterated or coarsened most of the

sights he described.

The haiku in The Narrow Road to Oku include some of his most famous.

The fi rst, written just before he started on his journey, is the most difficult

to understand without a commentary:

kusa no to mo Even a thatched hut

sumikawaru yo zo May change with the dweller

hina no ie Into a doll’s house.

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Matsuo Bashō 297

Th is translation is approximate. The background of the haiku was appar-

ently Bashō’s sale of his house to a man with small daughters. At the time of

the annual Feast of Peach Blossoms, dolls would be displayed in the house

now that girls lived there, but Bashō was a bachelor and as long as he had

lived in the house dolls had never been displayed. The thatched hut will

change into a doll’s house.

The next poem, the fi rst of the journey, is much easier:

yuku haru ya Spring is passing by!

tori naki uo no Birds are weeping and the eyes

me wa namida Of fish fi ll with tears.

Grief over the passage of spring was, of course, often expressed in poetry.

Bashō could not have been wholly serious in declaring that there are tears

in the eyes of fi sh, though he may have felt such empathy for other crea-

tures that he felt they shared his grief. The fi rst line of this haiku would be

echoed in the last line of the fi nal haiku of the journey, yuku aki zo (“au-

tumn is passing by”).

The Narrow Road to Oku consists of prose passages describing places

Bashō visited, together with poems inspired by each. Because most of

Bashō’s journey took place during the summer, the haiku naturally have

summer as their season, though summer haiku had been composed rela-

tively seldom. A curious result of the popularity of The Narrow Road of

Oku is that today more summer haiku are composed than for any other

season.

The haiku, good at the beginning of this diary, get even better as the

journey proceeds. The prose is marvelous from the start. Perhaps the most

affecting section of the entire diary occurs about halfway through. Bashō

visits a monument that survives from the eighth century. The text inscribed

on the stone relates the circumstances of the building and repairing of a

castle that had stood nearby. It is not in the least of literary interest, but it

moves Bashō profoundly:

Many are the names that have been preserved for us in poetry from

ancient times, but mountains crumble and rivers disappear, new roads

replace the old, stones are buried and vanish in the earth, trees grow

old and are replaced by saplings. Time passes and the world changes.

The remains of the past are shrouded in uncertainty. And yet, here

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

298 Matsuo Bashō

before my eyes was a monument that none would deny had lasted a

thousand years. I felt as if I were looking into the minds of the men of

old. “Th is,” I thought, “is one of the pleasures of travel and of living to

be old.” I forgot the weariness of my journey and was moved to tears

of joy.

Wherever Bashō went on his travels, he searched for places mentioned

in the poetry of the past. Often nothing remained, but this monument was

proof that even if mountains crumble and rivers dry up, written words will

survive. Later on in the journey, at Hiraizumi, he recalled lines by Du Fu

that insist that nature is hardier than any work of man:

It was at Palace-on-the-Heights that Yoshitsune and his picked retain-

ers fortified themselves, but his glory turned in a moment into this

wilderness of grass. “Countries may fall, but their rivers and moun-

tains remain; when spring comes to the ruined castle, the grass is

green again.” These lines went through my head as I sat on the ground,

my bamboo hat spread under me. There I sat weeping, unaware of the

passage of time /

natsukusa ya The summer grasses

tsuwamonodomo ga For many brave soldiers

yume ni ato The aftermath of dreams

Bashō was moved to tears by Tu Fu’s poem, but perhaps more important

was his earlier discovery that the written word lasts even longer than moun-

tains and rivers.

The Narrow Road to Oku has inspired many poets. Bashō was acclaimed

by his successors as the “saint of haiku,” and he was revered not only for his

haiku and his diaries but as a man of great goodness who lived in near pov-

erty and inspired the love of many disciples. It may be imagined what con-

sternation was caused when in 1943 the diary of Sora, Bashō’s companion

on The Narrow Road to Oku journey, was discovered and published, reveal-

ing serious discrepancies between the accounts of Bashō and Sora describ-

ing the same sights. Worshippers of Bashō refused to believe he could have

told a lie, but Sora’s diary is so devoid of literary pretense that one can only

suppose it is true.

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Matsuo Bashō 299

For example, when the two men arrived at Nikkō, Bashō was so moved

by the name of the place (nikkō means sunlight) and by its associations

with the Tokugawa shoguns who have their mausoleum there that he

wrote:

ara tōto How inspiring,

aoba wakaba ni On the green leaves, the young leaves

hi ni hikari The light of the sun.

But Sora’s diary stated that it rained on the day that they visited Nikkō. Bashō

evidently sacrificed truth to beauty. Again, Bashō described with wonder

the marvelous interior of the Konjikidō (Golden Hall) of the Chūsonji, but

Sora prosaically related that they could not fi nd anyone to open the hall and

therefore had to leave without seeing the famous sculptures.

The believers in the “saint of haiku” in desperation insisted that Sora had

either lied or was forgetful. Only after years had passed did they and other

scholars decide that The Narrow Road to Oku actually was enhanced by Bashō’s

departures from the facts. Th is proved that he was more concerned with the

artistic effect of the diary than with mere accuracy.

Although Bashō is without doubt the greatest haiku poet, at times he

has been criticized. In 1893, Masaoka Shiki, aged twenty-six, wrote a se-

ries of short essays on Bashō, which included these remarks: “Let me state

at the outset my conclusion: the majority of Bashō’s haiku consists of bad

verses and doggerel; those that might be termed superior amount to no

more than one out of dozens. No, even if one searches for barely accept-

able haiku, they are as rare as morning stars.” Shiki, about to start a school

of haiku on his own, seems to have felt that the best way to establish his

credentials as the champion of a new kind of haiku was to att ack the repu-

tation of the master. Of course, he hoped that his intemperate comments

would startle people, but his real enemy, as he later disclosed, was not

Bashō but his numerous followers, whom Shiki blamed for the decline in

the vital importance of the haiku. The followers of Bashō showed no

awareness of the changes that had occurred in Japan during the past three

hundred years, and their incompetent guidance of amateur poets had

reduced haiku composition to being nothing more than a means of earn-

ing a profitable income. Shiki successfully established his school, and

many other schools proliferated, but the reputation of Bashō remained

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

300 Matsuo Bashō

untarnished. His poetry will surely last as long as there are people who

can read Japanese.

Notes

1. If the second line were heitai tachi ga, an expression of identical meaning, the

poem would be destroyed by the unsuitably cheerful sounds.

2. I have tried to make the translations as literal as possible.

This content downloaded from

129.74.250.206 on Mon, 13 Feb 2023 18:53:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Answe Key Fall of The House of UsherDocument6 pagesAnswe Key Fall of The House of UsherGhena HamwiNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Poetry of Matsuo BashoDocument7 pagesAnalysis of The Poetry of Matsuo BashoMervyn Larrier100% (11)

- Harold Bloom (Editor) - Tony Kushner (Blooms Modern Critical Views) - Chelsea House Publishers (2005)Document206 pagesHarold Bloom (Editor) - Tony Kushner (Blooms Modern Critical Views) - Chelsea House Publishers (2005)Ana Maria Andronache100% (1)

- Cats in Spring Rain: A Celebration of Feline Charm in Japanese Art and HaikuFrom EverandCats in Spring Rain: A Celebration of Feline Charm in Japanese Art and HaikuNo ratings yet

- 12 8 Poem SpacecatDocument4 pages12 8 Poem Spacecatapi-571883491No ratings yet

- None Is Travelling-Basho MatsuoDocument11 pagesNone Is Travelling-Basho MatsuoRidhwan 'ewan' RoslanNo ratings yet

- Sastra Bandingan 2Document11 pagesSastra Bandingan 2Vhiiettd_aciuhmaNo ratings yet

- Women and The Rise of The Novel, 1405-1726: Josephine DonovanDocument191 pagesWomen and The Rise of The Novel, 1405-1726: Josephine DonovanHaneen Al IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Literature of JapanDocument6 pagesLiterature of Japanmaria yvonne camilotesNo ratings yet

- The Main Theme of BashoDocument4 pagesThe Main Theme of BashoANGELA V. BALELANo ratings yet

- Basho The Complete Haiku IntegralaDocument492 pagesBasho The Complete Haiku IntegralaShubhadip AichNo ratings yet

- Classic Haiku: An Anthology of Poems by Basho and His FollowersFrom EverandClassic Haiku: An Anthology of Poems by Basho and His FollowersRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Matsuo BashoDocument5 pagesMatsuo BashoMaria Angela ViceralNo ratings yet

- Matsuo Basho COMPLETE NOTESDocument3 pagesMatsuo Basho COMPLETE NOTESshanid.saudiaNo ratings yet

- Basho's Narrow Road: Spring and Autumn PassagesFrom EverandBasho's Narrow Road: Spring and Autumn PassagesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (18)

- HAIKU BASHO AND BUSON - DesalizaDocument16 pagesHAIKU BASHO AND BUSON - DesalizaJoshua Lander Soquita Cadayona100% (1)

- DGL, LunberryCMS2019LDocument14 pagesDGL, LunberryCMS2019LcoilNo ratings yet

- Beginner's Guide to Japanese Haiku: Major Works by Japan's Best-Loved Poets - From Basho and Issa to Ryokan and Santoka, with Works by Six Women Poets (Free Online Audio)From EverandBeginner's Guide to Japanese Haiku: Major Works by Japan's Best-Loved Poets - From Basho and Issa to Ryokan and Santoka, with Works by Six Women Poets (Free Online Audio)Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- OkayDocument3 pagesOkayashley cagadasNo ratings yet

- Basho's HokkuDocument4 pagesBasho's HokkuxibmabNo ratings yet

- HaikuDocument12 pagesHaikuAlphanso BarnesNo ratings yet

- Blyth On BashoDocument189 pagesBlyth On BashoMarko Mlinaric100% (1)

- On Love and Barley Haiku of Basho Matsuo - BashōStryk LucienDocument81 pagesOn Love and Barley Haiku of Basho Matsuo - BashōStryk Luciencalisto.aravena.zNo ratings yet

- Haiku: History of The Haiku FormDocument8 pagesHaiku: History of The Haiku FormKim HyunaNo ratings yet

- Blyth On BashoDocument189 pagesBlyth On BashojohNo ratings yet

- Matsuo Basho 2004 9Document121 pagesMatsuo Basho 2004 9arpitaNo ratings yet

- The Poet Vanishes Haiku by Chiyo Basho ADocument4 pagesThe Poet Vanishes Haiku by Chiyo Basho AwilliamcoymNo ratings yet

- (Japan) BashoDocument4 pages(Japan) BashoEhrykuh MaeNo ratings yet

- Matsuo Bashō - WikipediaDocument38 pagesMatsuo Bashō - Wikipediagolden wingsNo ratings yet

- HaikuDocument25 pagesHaikuKim HyunaNo ratings yet

- Basho HaikuDocument3 pagesBasho HaikusatoriasNo ratings yet

- Peipei Qiu - Celebrating Kyo: The Eccentricity of Basho and NampoDocument8 pagesPeipei Qiu - Celebrating Kyo: The Eccentricity of Basho and NampoHaiku NewsNo ratings yet

- ShiraneDocument16 pagesShiraneAlina Diana Bratosin100% (1)

- UntitledDocument6 pagesUntitledBill BensonNo ratings yet

- Haiku: Japanese LiteratureDocument14 pagesHaiku: Japanese LiteratureNestle Anne Tampos - TorresNo ratings yet

- Haiku Poem: Basho MatsuoDocument2 pagesHaiku Poem: Basho MatsuoMitchel BibarNo ratings yet

- Final Draft - Alexis LapidDocument5 pagesFinal Draft - Alexis Lapidapi-225280405No ratings yet

- Bashu Haiku PDFDocument44 pagesBashu Haiku PDFDavid Jaramillo KlinkertNo ratings yet

- Japane 351 PaperDocument8 pagesJapane 351 PaperAnthony M. WoodNo ratings yet

- Bashō, in Full Matsuo Bashō, Pseudonym of Matsuo Munefusa, (Born 1644, Ueno, Iga ProvinceDocument1 pageBashō, in Full Matsuo Bashō, Pseudonym of Matsuo Munefusa, (Born 1644, Ueno, Iga ProvinceAraNo ratings yet

- HaikuDocument1 pageHaiku서재배No ratings yet

- Haiku and Noh: Journeys To The Spirit World: Between Two WorldsDocument10 pagesHaiku and Noh: Journeys To The Spirit World: Between Two WorldsTsutsumi ChunagonNo ratings yet

- HAIKUDocument24 pagesHAIKUAllan Joy H. CaoileNo ratings yet

- 176 The Making of Modern JapanDocument1 page176 The Making of Modern JapanCharles MasonNo ratings yet

- On The Road AgainDocument3 pagesOn The Road Againfcrocco100% (2)

- A Definition of HaikuDocument13 pagesA Definition of HaikuKent DorseyNo ratings yet

- Finalreadingjournal 4Document4 pagesFinalreadingjournal 4api-518643296No ratings yet

- Haiku PoemsDocument4 pagesHaiku PoemsRebecca HayesNo ratings yet

- Basho's HaikusDocument5 pagesBasho's HaikusSaluibTanMelNo ratings yet

- The Old Pond by Matsuo BashoDocument8 pagesThe Old Pond by Matsuo Bashoemerine casonNo ratings yet

- Masako K. Hiraga, Eternal StillnesDocument15 pagesMasako K. Hiraga, Eternal StillnesparadoyleytraNo ratings yet

- MatsuoipediaDocument21 pagesMatsuoipediaBalayya PattapuNo ratings yet

- Poems - HaikuDocument2 pagesPoems - HaikuMabel BaybayonNo ratings yet

- HaikuDocument16 pagesHaikuMaria Kristina EvoraNo ratings yet

- Haiku SamplesDocument2 pagesHaiku SamplesKamoKamoNo ratings yet

- LevelUP Ready - Values Affirmation ActivityDocument5 pagesLevelUP Ready - Values Affirmation ActivitycoilNo ratings yet

- Rough (Final) Draft Junior Research PaperDocument8 pagesRough (Final) Draft Junior Research PapercoilNo ratings yet

- Scientific Reasoning AssignmentDocument2 pagesScientific Reasoning AssignmentcoilNo ratings yet

- Dataslate ImperialisDocument26 pagesDataslate ImperialiscoilNo ratings yet

- Calc+Unit+Organizer+-+7 1-7 2Document2 pagesCalc+Unit+Organizer+-+7 1-7 2coilNo ratings yet

- 7 2+Notes+-+Disk+MethodDocument2 pages7 2+Notes+-+Disk+MethodcoilNo ratings yet

- DGL, LunberryCMS2019LDocument14 pagesDGL, LunberryCMS2019LcoilNo ratings yet

- SigvaldAereus 58802402Document4 pagesSigvaldAereus 58802402coilNo ratings yet

- 7 2+Notes+-+Washer+MethodDocument2 pages7 2+Notes+-+Washer+MethodcoilNo ratings yet

- Volume: Disk Method WKSHTDocument2 pagesVolume: Disk Method WKSHTcoilNo ratings yet

- 7 1+7 2+Area+and+Volume+ (Disk) +practice+answersDocument2 pages7 1+7 2+Area+and+Volume+ (Disk) +practice+answerscoilNo ratings yet

- Act 4 QuestionsDocument1 pageAct 4 QuestionscoilNo ratings yet

- 5.5 NotesDocument2 pages5.5 NotescoilNo ratings yet

- Japanese Vs Chinese Characters SourcdDocument24 pagesJapanese Vs Chinese Characters SourcdcoilNo ratings yet

- Peer Review FormDocument2 pagesPeer Review FormcoilNo ratings yet

- CH 6 Notes 1 - Solving DEDocument2 pagesCH 6 Notes 1 - Solving DEcoilNo ratings yet

- Holy OrdersDocument2 pagesHoly OrderscoilNo ratings yet

- Outline For Jane Eyre EssayDocument2 pagesOutline For Jane Eyre EssaycoilNo ratings yet

- Bashō As BatDocument18 pagesBashō As BatcoilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Review AnswersDocument4 pagesChapter 5 Review AnswerscoilNo ratings yet

- Elie Wiesel Quote ActivityDocument2 pagesElie Wiesel Quote ActivitycoilNo ratings yet

- John Marshall - The ManDocument6 pagesJohn Marshall - The MancoilNo ratings yet

- AP Song ActivityDocument4 pagesAP Song ActivitycoilNo ratings yet

- Brave New World Chapters 13Document2 pagesBrave New World Chapters 13coilNo ratings yet

- Slides 2022Document18 pagesSlides 2022coilNo ratings yet

- Brave New World Paired PoemsDocument5 pagesBrave New World Paired PoemscoilNo ratings yet

- MS Chapter 5 Notes LOOPDocument9 pagesMS Chapter 5 Notes LOOPcoilNo ratings yet

- Brave New World Chapters 7:8Document2 pagesBrave New World Chapters 7:8coilNo ratings yet

- Phylum Ctenophora and Simple WormsDocument4 pagesPhylum Ctenophora and Simple WormscoilNo ratings yet

- Phylum Echinodermata Notes and ChartDocument5 pagesPhylum Echinodermata Notes and ChartcoilNo ratings yet

- Rizal Midterm ReviewerDocument16 pagesRizal Midterm Reviewerblahblahblacksheep76No ratings yet

- Revision For Unit 1,2,3Document9 pagesRevision For Unit 1,2,3Pham ThuhienNo ratings yet

- العلاقات السياسية بين إيالة الجزائر العثمانية وإنجلترا قراءة من خلال الكتابات الفرنسية في المجلة الإفريقيةDocument22 pagesالعلاقات السياسية بين إيالة الجزائر العثمانية وإنجلترا قراءة من خلال الكتابات الفرنسية في المجلة الإفريقيةonlymen0001No ratings yet

- Samuel Beckett, Repetition and Modern Music - John McGrath - 2017 - Anna's ArchiveDocument191 pagesSamuel Beckett, Repetition and Modern Music - John McGrath - 2017 - Anna's ArchiveDavide PentassugliaNo ratings yet

- Brush Up Your Poetry!Document259 pagesBrush Up Your Poetry!Aditya AmatyaNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Romeo and Juliet PDFDocument174 pagesShakespeare Romeo and Juliet PDFgoranstojanovicscribNo ratings yet

- Living in Subalterinity: The Voiceless Others in Nadine Gordimer's Selected Short StoriesDocument7 pagesLiving in Subalterinity: The Voiceless Others in Nadine Gordimer's Selected Short StoriesIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Maitreya in MrichchhakatikaDocument2 pagesMaitreya in Mrichchhakatikaxoh23028No ratings yet

- Glyn's Haunted House Halloween Crossword: Across DownDocument2 pagesGlyn's Haunted House Halloween Crossword: Across DownAna SilvaNo ratings yet

- Alice in WonderlandDocument65 pagesAlice in WonderlandshiyizhuNo ratings yet

- Estelle de Koning - Female Agency in The NibelungenliedDocument51 pagesEstelle de Koning - Female Agency in The NibelungenliedKarina AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Anapa Ne: Anwumme-S3ReDocument91 pagesAnapa Ne: Anwumme-S3ReBangmeyiri VitalisNo ratings yet

- SS23 Catalog Copper Canyon PressDocument12 pagesSS23 Catalog Copper Canyon PresshoneromarNo ratings yet

- Bonku Babu NotesDocument15 pagesBonku Babu NotesThe Two side ShowNo ratings yet

- Biomedical Engineering Society, BangladeshDocument1 pageBiomedical Engineering Society, BangladeshDr. Mohammad Nazrul IslamNo ratings yet

- La Biblia de KolbrinDocument599 pagesLa Biblia de KolbrinAngel Marín VargasNo ratings yet

- ReflectionDocument5 pagesReflectionTesalonicaNo ratings yet

- Excursion Proposal FormDocument1 pageExcursion Proposal Formapi-397550031No ratings yet

- Shabbir Dhondhte Rahe Pyare Gaye KahaDocument4 pagesShabbir Dhondhte Rahe Pyare Gaye Kahammmurtaza100% (1)

- Instructions: Recall What You Learned About Poetry. Read and Answer TheDocument4 pagesInstructions: Recall What You Learned About Poetry. Read and Answer Thesonny mark cabangNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Huckleberry FinnDocument3 pagesThe Adventures of Huckleberry FinnCrina Mitran100% (1)

- 3RD Quiz in CNFDocument5 pages3RD Quiz in CNFRica Mel MaalaNo ratings yet

- T. S. Eliot-DanteDocument17 pagesT. S. Eliot-DanteПавле ЛучићNo ratings yet

- Course Outline (English 10 S.Y. 2021-2022)Document6 pagesCourse Outline (English 10 S.Y. 2021-2022)Tracia Mae Santos BolarioNo ratings yet

- What Made The Masses Revolutionary Ignorance Character and CLDocument24 pagesWhat Made The Masses Revolutionary Ignorance Character and CLJEN CANTOMAYORNo ratings yet

- Persusaive EssayDocument5 pagesPersusaive Essayb72hvt2d100% (2)