Professional Documents

Culture Documents

American Sociological Association

American Sociological Association

Uploaded by

Harry LoftusOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

American Sociological Association

American Sociological Association

Uploaded by

Harry LoftusCopyright:

Available Formats

Civic Associations and Authoritarian Regimes in Interwar Europe: Italy and Spain in

Comparative Perspective

Author(s): Dylan Riley

Source: American Sociological Review, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Apr., 2005), pp. 288-310

Published by: American Sociological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4145371 .

Accessed: 05/07/2014 16:52

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Sociological Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CivicAssociationsand AuthoritarianRegimes

in InterwarEurope:

Italyand Spainin ComparativePerspective

Dylan Riley

University of California, Berkeley

Whatis the relationship between civic associations and authoritarian regimes? While

Tocquevillian theories have concentrated mostly on the connection between civic

associationism and democracy, this article develops a Gramscian approach, suggesting

that a strong associational sphere can facilitate the development of authoritarian parties

and hegemonic authoritarian regimes. Twocountries are used for comparison, Italy from

1870 to 1926 and Spain from 1876 to 1926. The argument here is that the strength of the

associational sphere in north-central Italy provided organizational resources to the

fascist movement and then party. In turn, theformation of the party was a key reason

why the Italian regime developed as a hegemonic authoritarian regime. The absence of a

strong associational sphere in Spain explains why that regime developed as an economic

corporate dictatorship, despite many similarities between the two cases.

workon civic associationism regime and the Spanishdictatorshipof Miguel

Contemporary

focusesmostly on democracy(Arato1981; Primode Rivera(1870-1930). By hegemony I

Paxton 2002; Putnam 1993; Wuthnow 1991). meanthe extentto whicha regimepoliticizesthe

This analysis investigatesinsteadthe relation- associationalspherein accordancewith its offi-

cial ideology.A hegemonicauthoritarian regime

ship betweenassociationismandauthoritarian-

ism. I explore how the strength of the exists to the extent that official regime unions,

associational sphere influenced the degree of employers'organizations,andprofessionalasso-

ciations exist. In contrast,economic-corporate

regime hegemony in two cases of interwar dictatorshipsleave the preexistingassociation-

Europeanauthoritarianism:the Italian fascist al terrainintact. I treat Italian fascism and de

Rivera's Spain as instances, respectively, of

hegemonic authoritarianismand an economic

Direct all correspondence to Dylan Riley, corporate dictatorship, and I ask how the

Department of Sociology,Universityof California strengthof the associationalsphereshapedthese

Berkeley,410 BarrowsHall #1980, Berkeley,CA divergentoutcomes.

94720-1980(riley@berkeley.edu). Thisresearchwas Classic scholarshipin the Tocquevilliantra-

fundedby an IIEFulbrightgrant.Manythanksto dition suggests that a developed associational

PerryAnderson, VictoriaBonnell,MichaelBurawoy, sphereshouldpreserve a realm of privatenon-

RebeccaEmigh,CarloGinzburg,ChaseLangford regime-dominated social relations (Arendt

(whohelpedwiththemap),MichaelMann,Emanuela 1958:323; Friedrichand Brzezinksi 1966:279;

Tallo,andthestudentsattheCenterforComparative Kornhauser1959:30,76-90; Lerderer1940:72).

SocialAnalysisat UCLAfortheirhelpon thisarti-

Therefore,it should be difficult to establish a

cle. In addition,the authorthanksaudiencesat UC

andcolleaguesin hegemonic authoritarianregime in the context

Davis,JohnsHopkinsUniversity, of a strong associational sphere. I suggest, in

both the Departmentof Sociology and Social

Anthropologyand the Departmentof Political contrast, that relatively strong associational

ScienceattheCentral EuropeanUniversity,

Budapest. spheresin the preseizureof powerperiod have

Theauthor alsothankstheASReditorandanonymous sometimesrenderedauthoritarian regimesmore

reviewersforbeingbothextraordinarily helpfuland hegemonic than they would be had associa-

patient. tionismbeen weaker.To establishmy argument,

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL

REVIEW, 2005, VOL. 70 (April:288-31o)

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDAUTHORITARIAN

CIVICASSOCIATIONS IN EUROPE 289

REGIMES

I develop a historicaland comparativeanalysis and cooperatives, employers' organizations,

of Italian fascism and Spanish authoritarian- unions, chambersof labor,and democratically

ism in the early1920s.My mainargumentis that orientedpoliticalparties(Paxton2002; Schofer

the Italianfascistpartycouldemergeonly in the and Fourcade-Gourinchas 2001; Putnam

context of a relatively strong associational 2000:15-28; Skocpol and Fiorina 1999:2;

sphere,andthe Italianfascisthegemonicauthor- Wuthnow1991:7).

itarianregime could emergeonly becausethere I consider two theories of the relationship

was a strong fascist party.Radical right-wing between associationism and authoritarianism:

forces were unableto constitutethemselves as the Tocquevillianview andthe Gramscianalter-

a fascist party in the Spanishcase, where civic native for which I will argue. Tocquevillians

associationismwas relativelyweak. Thus, sig- argue that civic associationism protects the

nificant pockets of nonpoliticized social exis- sphereof privateexistence makinghegemonic

tence remained in Spain. The result was an authoritarianregime formation difficult. The

economic-corporatedictatorship. Tocquevillianapproachidentifies two specific

mechanisms:insulationandorganizationalbal-

THEORIZING CAPITALIST ancing. The insulation argumentsuggests that

AUTHORITARIANISM, CIVIC the more developedthe sphereof associations,

ASSOCIATIONISM, HEGEMONY

AND the more difficult it will be to establishauthor-

itarianpartyorganizationsbecause such organ-

Drawingon Gramsci(1971:259),I usetheterm izations appeal primarilyto persons who are

hegemony to referto the political organization socially atomized and, therefore, lack well-

of consent. Some regimes devote considerable structured interests (Arendt 1958:311;

effort to the political constitutionof their sup- Kornhauser1959:46,64; Tocqueville1988:523).

porting social interests, while others adopt a The organizationalbalancing argument sug-

morepragmaticbargainingorientationto these. gests thatassociationsprovidepeople the means

Hegemonic authoritarianregimes, as a conse- to act withoutinvokingthe stateand such asso-

quence of their concertedorganizationof con- ciationsalso balancestateauthorityby creating

sent, tend to eliminatethe distinctionbetween alternativepower centers (Putnam 2000:345;

public and private existence penetrating the Tocqueville1988:516).TheTocquevilliananaly-

associationalsphereand reducingthe realm of sis of authoritarianism and civic associationism

nonpolitically relevant activities. In contrast, follows logically from this view. Strong asso-

economic corporatedictatorshipstolerate and ciational spheres should presentan obstacle to

encouragenonpoliticalorganizations,general- the formationof authoritarian partiesand hege-

ly basing themselves on alliances with preex- monic authoritarian regimes(Arendt1958:323;

istinggroupsthatthey neithercreatenor greatly Gannett 2003:11-12; Goldberg 2001;

alter.Thus, the main theoreticalpuzzle here is Kornhauser 1959:76-90; Lerderer 1940:72;

"Why do authoritarianregimes with similar Tocqueville 1988:516).

bases of social supportdiffer in theirdegree of The Gramscianview rejectstheTocquevillian

hegemony?"I seek to relatethese differentout- claim of a zero sum relationshipbetween social

comes to differencesin the strengthof the asso-

self-organizationandpolitical power (Bellamy

ciationalspherepriorto the seizureof powerin and Schechter 1993:123; Gramsci 1971:160;

the cases of Spainand Italy in the earlytwenti- Laclau and Mouffe [1985] 2001:xvii). For

eth century(Gramsci1971:216,259).1The asso-

Gramsci,the sphereof associationsis important

ciationalsphererefersto a thirdsectorbetween because it produces technologies of political

states and marketscomprisedmostly of volun- rule thatpotentiallycan extendthe reach of the

tary associations, such as mutualaid societies state (Bellamy and Schecther 1993:122;

Gramsci1971:259).Morespecifically,Gramsci

rejects the two basic arguments of the

1Although generally notstatedinGramscianterms Tocquevillianposition.First,for Gramsci,asso-

thisdistinctionis quitecommonin theliteratureon ciations are not necessarilyopposed to author-

authoritarianism (De Felice [1981] 1996:10-11; itarianparties.Such partiesarebased precisely

Gentile2000:240-41;Linz 1970:262;2003:29-40, on an integration of local and sectoral inter-

68; Pavone 1998:75). ests, not on a socially atomizedmass (Anderson

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

29o SOCIOLOGICAL

AMERICAN REVIEW

1965:242;Gramsci1971:181).Second,although and Spain.Thus, in this study,the cases should

associationsmay startas opposed to the state, be understoodas members of the conceptual

they can be reabsorbed by it. Indeed, in class of sequences of "transitionsto authoritar-

Gramsci's view, strong associational spheres ian rule" (for this use of case language see

can enablehegemonic authoritarianregimes to Abbott 1983:137; Abbott 1992:53). My

the extent that associations provide a congen- approach is unusual because I synthesize a

ial environmentfor the constructionof author- Milliancomparativestrategy(for examples,see

itarianparties,which are both a key agent and Brenner 1985:252; Emigh 1997:651; Ertman

central institutional feature of hegemonic 1997; Gorski 1993; Skocpol 1979:37) with an

authoritarian regimes (Gramsci1971:221).The analysisof suppressedalternativesembeddedin

associationalsphere,in this scheme, is a poten- historical sequences (Moore 1978:385-91;

tial transmissionbelt ratherthana bulwarkpro- Weber 1949:172). I use Mill's comparative

tectingprivateexistence.It is worthemphasizing method to justify my focus on Italy and Spain.

thatthe Italianfasciststhemselveslargelyshared Specifically, I use the method of difference,

this Gramscianview of the associationalsphere which comparescases that are similar in theo-

(Bottai 1934:29; Panunzio 1987:272). Adrian reticallyrelevantrespectsbut thatdiffer in out-

Lyttelton(1987:205) neatly catches the point come (Mill 1971:211-19; Skocpol and Somers

when he contrasts de Tocqueville with the 1980:184).

nationalist and then fascist theorist Alfredo I do not, however,adopt a Millian approach

Rocco (1875-1925): to developingmy own explanation.The Millian

The'intermediateassociation',forDeTocqueville approachis particularlyinadequatefor socio-

a necessarycheckonthepowerof theState,which historical explanations, because it does not

wouldotherwiseoverwhelm theisolatedindivid- demanda specification of mechanisms, and it

ual, for Rocco was insteadto be a cog in the leads to misleading generalizationsparticular-

machinery whichwouldensurehis [sic]subordi- ly because the method obscuresthe possibility

nation. of divergent causal pathways to similar out-

This leads to a relativelyclear prediction.In comes (Burawoy1989:769-72;Lieberson1991,

historical contexts, where an authoritarian 1994; Steinmetz 1998:173). I push beyond a

seizure of power is likely, one may expect the conventionalMillian approach,because I show

associationalsphere to facilitate the construc- how the associationalsphere in Italy was con-

tion of a hegemonic authoritarianregime. The nectedto the formationof a fascist party,which

absenceof a strongassociationalsphereshould then became a centralactorin the construction

of a hegemonic authoritarianregime in the

place limits on authoritarianparty formation,

andthis shouldhave consequencesfor the kind Italian case. The existence of the fascist party

of authoritarianism thatemerges.Thus, in con- in Italy blocked the possibility of the more

trast to the Tocquevillian suggestion that the relaxed dictatorship that Benito Mussolini

associationalspherealwaysconstitutesa barri- (1883-1945) tried to institute.Conversely,the

er to hegemonic authoritarianregime forma- absence of a strong party actor in the Spanish

tion, the Gramscianview suggests thatit can be case explains why, despite the existence of

an enabling structurefor this type of authori- fascisticcurrentsin Spain,the regimedeveloped

tarianrule. as an economiccorporatedictatorship.Thus,my

methodemphasizeshow associationismshould

be understoodin terms of the specific histori-

AND METHOD

CASESELECTION cal trajectories through which authoritarian

This articledevelops a comparativeand histor- regimes consolidatedin Spain and Italy in the

ical approachto civic associationismandauthor- early 1920s. This methodologicalstrategyuses

itarianism. The relative strength of civic possibilitiesintrinsicto the historicalsequences

associationismin Italyandits relativeweakness themselves to establish the importanceof the

in Spainbecame causally relevantthroughthe conditions identified in the comparativesec-

activityof social agents,who attemptedto build tion of the essay (Desai 2002; Elster

radical right-wing political movements and 1978:175-232; Moore 1966:108-10; Moore

authoritarianregimes in the specific historical 1978:385-91; Weber 1949:172; Zeitlin

circumstancesof early twentiethcentury Italy 1984:18-20). This analysisproducesa different

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CIVICASSOCIATIONS

ANDAUTHORITARIAN

REGIMES

IN EUROPE 291

type of generalizationthan a standardMillian (Federico 1996:771-2; Zamagni 1993:89, 95,

theory of explanationwould demand.I do not 162).

aim to discovera coveringlaw,i.e., a statement Labor repressive large landlords in Spain

of the type, "Inall instanceswhere a relatively concentratedin the southand west of the coun-

strong associational sphere combines with a try (Simpson1992:108-9), anda huge latenine-

political crisishegemonicauthoritarianism will teenthcenturylandsell-off (10 millionhectares)

be the outcome"(for critiquesof covering law enlargedthis group(Simpson 1995:44;Tortella

models, see Bashkar 1998:41; Steinmetz 2000:56; Trebilcock 1981:327-8). As in Italy,

1998:176-7). Rather,I seek to show thatin the an allianceof industryandlaborrepressiveagri-

contextof post-WorldWarI Italy,a strongasso- culturepushedtariffprotectionin the late nine-

ciational sphere was a crucial mechanism in teenth century. Catalan textile producers and

the constructionof the fascist party,which was Castilianwheatgrowerspushed for a total pro-

tective tariff,which the governmentenacted in

equallya crucialmechanismleadingto a hege-

monic authoritarianregime. December of 1891 (Tortella2000:199).

The structureof my analysis is in terms of Thus, both Italy and Spainpossessed one of

the classic preconditionsof authoritarianism: a

backgroundconditionsandsequencesof events.

The trajectoriesthatI select areItalyfrom 1870 nascentstate-dependentgroupof industrialists,

to 1926, and Spain from 1876 to 1926. I estab- and a significant sector of large landholders

lish the roughcomparabilityof Spainand Italy socially dependenton the political subordina-

tion of the agrarianmasses. These key interests

in termsof theirclass structuresandstatesat the

coalescedaroundtariffprotectionin both cases.

beginning of the twentiethcentury.I then dis- In Italy,landedinterestsin the southandthe val-

cuss regionaland cross-nationaldifferencesin

associationalstrengthin the two cases. Finally, ley of the Po allied with the nascentsteel indus-

I show how these differences mattered for try to supporta state-ledindustrialdevelopment

underthe leadershipof PrimeMinisterAgostino

authoritarianmovements and regimes in the

two countries. Specifically, I trace the diver- Depretis (1813-1887) (Carocci 1975:74-5). A

similarindustrialandagrarianbloc, basedon an

gent forms of political organizationthat simi- allianceamongCatalantextiles,Basquemining

larly placed radicalright-wingforces hit upon and southernagriculturedeveloped in Spain in

in differentregionsof SpainandItalyandin the the latenineteenthcentury(Tusell1990:14-20).

two nationalcases. The political institutionsof the two regimes

also made the developmentof democracydif-

TWO PERIPHERALCAPITALISMS ficult. Neither the Italiannor the Spanishpar-

liament was based on an alternationbetween

An agro-industrialbloc closely connected to

the state, supportinghigh tariffs and political partiesthatwon competitiveelections. Rather,

governmentsemerged on the basis of gentle-

authoritarianism, beganto consolidatein Spain men's agreements among deputies. In liberal

and Italy by the late nineteenthcentury.Many

Italy, governmentswere based on big parlia-

scholarssuggest thatthis was majorreason for

mentarymajoritiesof the centerrallyingbehind

authoritarianismin both cases. Big holdings leaders of various political hues. Depretis ini-

and a politically dependent labor force were tiatedthis systemof politicalco-optation,called

commonin preunificationsouthernItaly,andthe

trasformismo(transformism),in the aftermath

problemwas exacerbatedin the late 1860swhen of the elections of 1882 when he invited mem-

the Italianstate sold off public lands mostly in bers of the oppositionto transformthemselves

the south (2.5 million hectaresout of a total of into members of the majority (Chabod

3 million hectares privatized) (Castronovo 1961:41-3; Salvemini [1945] 1960:xviii).

1975:58; Zamagni 1993:21-2, 56, 175). Spanishliberalismwas based insteadon a sys-

Southernagrariansgenerallypushed for tariff tem of partyalternationbetween the conserva-

protections,ratherthan cost-cuttingto support tive liberalsandthe liberalscalled el turno(the

their economic position. Key sectors of Italian turn) (Lyttelton 1973:98; G6mez-Navarro

industry(railroads,steel, shipbuilding,cotton 1991:60). When a turn was exhausted, the

cloth manufacturing,and sugar refining) also monarch(1875-1885, Alfonso XII; 1886-1902,

demandedandreceivedsubstantialstatesupport Maria Cristina the Queen regent; and

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

292 AMERICAN REVIEW

SOCIOLOGICAL

1902-1923, Alfonso XII's posthumous son tury, driven by early industrializationand the

Alfonso XIII)wouldappointa new government development of capitalist agriculture. This

from the loyal opposition. This government regional variation shaped radical right-wing

would then fix the elections, with the complic- movements in the post-World WarI period in

ity of the outgoing party, giving retroactive bothcountries.HoweverSpainandItalydiffered

legitimacyto the alternation(Boyd 1979:4;Carr at the national level. Associationism in Spain

1982:356-7). In both cases, however,therewas was generally weaker, and specifically more

little relationshipbetween elections and gov- regionally fragmented,than in Italy.

ernments. Fromthe 1890s, two kinds of associationsin

Both liberalismsalso had imperfectsuffrage. Italywere particularlyimportantat the popular

In Italy,suffragewas limited to abouttwo per- level: cooperatives and mutual aid societies

centof the populationuntil 1882,whenDepretis (Bonfante 1981:203-5; Carocci 1971:13-4,

expanded it to seven percent. Prime Minister 18-9). By encouraging their development,

GiovanniGiolitti (1842-1928) introduceduni- Italianliberal 61itesaimed to give the working

versalsuffragein 1912, anda proportionalelec- class andpeasantrya stakein the liberalsystem

toralsystem was establishedin 1919. Electoral while stimulatingownersto fend forthemselves

corruption,confinedmostlyto the south,played (Degl'Innocenti 1981:36; Fornasari and

a key role in maintainingliberaldominance.In Zamagni 1997:79). Most cooperatives were

Spain, the liberal parliamentarianPrixedes either consumer cooperatives providing low

Mateo Sagasta (1825-1903) introduced uni- cost goods, or producers'cooperativesdistrib-

versal suffrage in 1890 (Carr 1982:359; Linz uting jobs among their members

1967:202). Laws in the late 1880s and 1890s (Degl'Innocenti 1981:28-9; Fornasari and

also guaranteedfreedomof associationandthe Zamagni1997:83).Using cooperatives,Giolitti

rightto strike(Payne1973:475;Tusell1990:26). wanted to relieve unemployment especially

But these precocious laws were largely violat- among the agriculturalproletariatandto weak-

ed in practice by local political bosses who en the socialists (Bonfante 1981:205).The pol-

coerced and manipulatedthe population into icy encouragedthe developmentof associations.

voting for official candidates. According to the Lega nazionale delle cooper-

The two countries,then, startedthe twentieth ative italiane (National League of Italian

centuryin a similarposition as peripheralcap- Cooperative Societies), the number of Italian

italist societies with large regional disparities cooperativesincreased from 2,199 in 1902 to

and powerfulagrarianel1ites.In both cases the 7,429 in 1914 while the number of members

landedaristocracyand industrialinterestsfused expandedfromabout0.5 million to 1.5 million

intoa statedependentagro-industrial bloc in the (FornasariandZamagni1997:81).Cooperatives

late nineteenth century. Both countries were were regionally concentratedin the north and

also ruledby oligarchicliberalstates.It should center of Italy in the three provinces of the

come as no surprise then that scholars have Emilia Romagna, Tuscany, and Lombardy

oftenstressedthe similaritiesbetweenthe Italian (Fornasariand Zamagni 1997:83).

and Spanish cases in terms of their political The early part of the twentiethcentury was

institutions and class structures (Stephens a period of associationaldevelopmentin Spain

1989:1060-61). Since these two factors were as well. As in Italy,this developmentwas region-

quite similarin the Italianand Spanishcases, it ally uneven.In north-centralSpain,wheresmall

is unlikely that they can explain the divergent propertyholders predominated,agrariansyn-

regimes that emergedin the 1920s. dicates presided over by clergy and providing

credit for seeds, machinery, and equipment,

established a strong base of operations. For

CIVICASSOCIATIONISM

IN ITALYAND SPAIN example, the CatholicAgro-Social of Navarre

includeda vast networkof cooperatives,leisure

On the basis of these relatively similar class centers, small rural mutual aid and insurance

and state structures,Italy and Spaindeveloped funds, and youth organizations (Mufioz

differentlystructuredassociationalspheres.In 1992:77).Therewerealso Catholicmixedowner

bothcases associationismincreasedin a region- andworkersyndicatesandnumerousruralbanks

ally uneven patternin the late nineteenthcen- and farmers'circles (Perez-Diaz 1991:7).

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDAUTHORITARIAN

CIVICASSOCIATIONS IN EUROPE 293

REGIMES

In Spain, lay popularassociationismtook a tionism that followed the same municipalpat-

variety of forms, from cooperatives,to mutual tern.In 1903, a federationof white-collarwork-

aid societies, to Casas del Pueblo (people's ers was established.Theseprocessesintensified

houses) (Carr 1982:454-55; Vives 1959: in the immediatepostwarperiod as the organi-

211-32). Alejandro Lerroux (1864-1949), a zationalmodel of the tradeunionextendedinto

Republicanpolitician,broughtthe model of the the ranks of white-collarworkers.In the peri-

Casas del Puebloto SpainfromBelgium,where od immediately before the rise of fascism, a

the socialists lattercopied it. These were part- new roundof associationaldevelopmentamong

ly political and partlyculturalinstitutionswith white-collarworkerstook place. In 1919, new

committeerooms andlendinglibraries(Brenan associationsof lawyersandprosecutors,doctors

2000:219). An associationalcensus conducted and engineers formed (Turi 1994:20). From

by the Institutode reformassociales (Institute 1906 to 1910 northernindustrialistsestablished

of Social Reforms)demonstratesthe explosion the Confederazione italiana dell'industria

of popular associationism at the turn of the (Italian Confederation of Industry) (Banti

nineteenthcentury.The survey included asso- 1996:300).

ciations that were founded between 1884 and Upperclass associationismin Spainwas driv-

1904, and it showedthat78 percentof all work- en partlyby protectionistsentimentin Catalonia

ers' associations were founded in the years and partlyby disgust over the consequencesof

between 1899 and 1904 (Institutode reformas the loss of Cuba in 1898 (Balfour 1997:80-3;

sociales 1907:286). Associationism in Spain Tusell 1990:47; Vilar 1987:71). As was also

was regionally uneven as in Italy. Most evi- true of Italy,one of the most active periods of

dence suggeststhatpopularassociationismwas upperclass associationismwas duringthe tar-

most developed in Old Castile, Navarre, the iff struggles of the 1880s (Vilar 1987:77-8).

Basquecountry,andCatalonia.In the firstthree Upper class associationism in Spain tended,

provincesin north-centralSpain,Catholicasso- however,to be fragmentedby regionalnation-

ciations of very small proprietorsdominated. alist sentiment. This was particularlytrue in

Associationismwas restrictedto workersand Catalonia and the Basque countries where it

smallpropertyholdersin neithercase.As indus- developed in close relationshipwith regional

try developed in northernItaly,the industrial- separatism(Payne1971:35-6; Payne1973:579;

ists formed a syndicate called the Lega Vilar 1987:76-7). Employers' organizations

industrialedi Torino(TurinIndustrialLeague) were also qualitativelyweakerin Spainthanin

in 1906 (Adler 1995:75).Associationspursuing Italy.As Payne(1970:38) says in the following:

various industrial and professional interests Spanishentrepreneurs were not accustomedto

appearedalso duringthe tariff struggles of the spendingtimeandmoneyon cooperative profes-

1880s (Banti 1996:162).Agrarianassociations sionalendeavorsunlessfacedby direnecessity.

were quite important.Many of these grew out Employers' thustendedtobelocaland

associations

of older agrarianacademiesestablishedfor the limited,for thesegroupslackedthe moneyand

influenceof theirAmerican,German,or even

purpose of protecting the economic interests FrenchandItaliancounterparts.

of their members and spreading technical

knowledge(Ridolfi 1999:130).By the latenine- The role of the CatholicChurchin the asso-

teenth century,they had developedinto agrari- ciationalspherealso differedin SpainandItaly.

an committees (Ridolfi 1999:131-2). In the The church in Spain was a highly privileged

earlytwentiethcentury,these becamemoremil- official institutionandtendedthusto be less pro-

itant. After a series of bitter strikes led by the ductive of associationismthan in Italy (Payne

revolutionary syndicalists, a form of radical 1973:603). Duringthe late nineteenthcentury,

precommunist socialism, in 1907 and 1908, Catholicreligiousordersproliferated(Callahan

landowners began to organize self-defense 2000:52; Carr2000:232). However,these, espe-

leagues. In 1910, these mergedinto the agrari- cially the Jesuits,werewealthyandclosely con-

an confederation,which controlled 10 subas- nected to political power (Brenan 2000:47).

sociations, had over 6,000 members, and GrassrootsCatholicorganizationsin Spainwere

controlled the Bolognese newspaperII Resto confined mostly to the north and the east, and

del Carlino (Banti 1996:294-5). White-collar they were associatedwith Basque nationalism

professionals produced a version of associa- andCarlism.Attemptsto breakout of the north-

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

294 AMERICAN REVIEW

SOCIOLOGICAL

eastern strongholdwere largely unsuccessful, quence, Catholicismin Italytendedto be much

partlybecause of the powerof the churchhier- less of a state-centered61itephenomenonthan

archy (Carr 2000:232; Tusell 1974:88-7). in Spain, and it tendedto have a strongergrass

Catholic workers'circles, originallypromoted roots organization. The Catholic reformers

by the CatalanindustrialistClaudioL6pez Bru, Romolo Murri(1870-1944) and Luigi Sturzo

marques de Comillas (1853-1925), and the (1871-1959) imitated the methods of the

JesuitfatherAntonioVincent(1837-1912) were reformist socialists and established coopera-

generallyunsuccessful(Tussell1974:40,87-8). tives, unions, mutualaid societies, andpopular

The church in Spain thus tended to be much libraries especially in north-central Italy

morean organizationof the statethanan organ- (Webster1960:9).Ragionieri(1972:294) writes

ization of society. The following are Brenan's the following:

(2000:52) scathingwords: The 'white'[Catholic]workersleaguesflanked

Insteadof meetingtheSocialistsandtheAnarchists mutualisticand cooperativeinstitutionsin the

on theirown groundwith labororganizations, urbancentersand in the countryside,diffusing

friendlysocietiesandprojectsfor socialreform, mostlyinnorthern Italy,butalsoin somezonesof

[the church]... concentratedits efforts upon the centralItalyand in Sicily.

searchfor a government thatwouldsuppressits because of its difficult rela-

Thus, precisely

enemiesby force.

tionship with the Italian state, the churchtend-

The position of the churchin Italy differed. ed to producemore associationsin Italythanin

Relations between church and state were Spain.The similaritiesandcontrastsbetweenthe

strainedfromthe unificationof Italyto at least two cases can be brieflysummarizedwith quan-

1909. Indeed, the papal injunction known as titativeevidence.

the non expedit(meaning"it is not expedient") Table 1 shows five indicators of regional

formally banned Catholicsfrom participation in variation in the strengthof civic associationism

nationallevel Italianpolitical life. As a conse- in prefascistItaly,and it suggests a fairly clear

Table1. RegionalVariationin CivicAssociationismin Italy

Membersof LiteratePersons

Cooperatives Leagues Leagues (%) Periodicals

Region 1915 1912 1912 1911 1905

Basilicata 36 0 0 35 2

AbruzzoandMolise 68 0 0 42 5

Sardinia 64 1 321 42 3

Calabria 117 1 102 30 4

Campania 231 4 613 46 10

Sicily 374 6 1,087 42 5

Marche 225 5 496 49 8

Apulia 263 5 2,104 41 5

Umbria 104 5 646 51 11

Veneto 669 5 664 75 6

Piedmont 620 8 930 89 12

Lazio 447 9 1,002 67 26

Tuscany 770 12 1,116 63 13

Lombardy 1477 15 1,316 87 12

Emilia-Romagna 1575 100 7,886 67 8

Liguria 389 16 1,873 83 12

Note: Datashownas numberper 100,000inhabitants,exceptwhereindicated.

Sources:Capecchi,VittorioandMarinoLivolsi. 1971.La stampaquotidianain Italia. Milan,Italy;Bompiani;

Degl'Innocenti,Maurizio.1977.Storiadella cooperazionein Italia: 1886-1925.Rome,Italy:Riuniti;Forgacs,

David. 1990.ItalianCulturein theIndustrialEra: 1880-1980. ManchesterandNew York:St. Martin'sPress;

Ministerodi agricoltura,industriae commercio.1913.Statisticadelle organizzazionidi lavoratori.Rome,Italy:

Officinapoligrafica.

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CIVICASSOCIATIONS

ANDAUTHORITARIAN IN EUROPE 295

REGIMES

Table2. RegionalVariationin CivicAssociationismin Spain

Workers' Workers' Bosses' Mixed Nonprofessional

Associations Associations Associations Associations Associations Associations

Region 1928 1904 1913 1913 1913 1913

Galicia 8 4 34 17 1 5

Leon 9 6 18 25 1 21

Aragon 10 4 15 46 2 18

Andalusia 10 8 26 13 1 5

Asturias 10 7 41 34 2 3

Murcia 11 4 29 21 1 11

Estremadura 12 8 11 19 1 10

New Castile 16 11 28 22 2 13

Catalonia 25 23 49 45 3 96

Valencia 26 13 44 40 5 21

BasqueCountry 28 20 82 47 4 33

OldCastile 29 10 30 52 4 13

Navarre 44 7 16 64 4 9

Note:Datashownas numberof associationsper 100,000inhabitants.Numbersin italic representthe top five

regionswithineachof theseassociationalindicators.

Sources:Institutode ReformasSociales. 1915.Avanceal censo de asociaciones.Madrid:Imprentade la

Sucesorade M. Minuesa.Institutode ReformasSociales. 1907.Estadisticade la asociaci6nobrera.Madrid:

Imprentade la SucesoraM. Minuesa.Ministeriode Trabajoy Previsi6n.1930. Censocorporativoelectoral.

Madrid:Imprentade los hijosde M. G. Hernindez.

north-south split. Veneto, Piedmont, Lazio, regions on each one of these associationalindi-

Tuscany, Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, and cators. Cataloniaand the Basque countries in

Liguriahad amongthe highestnumberof coop- everysurvey,for everyindicatorwereamongthe

erativesper 100,000 inhabitantsin 1915, high- top five regions in associationaldensity.This is

est densitiesof leagues,andhighestdensitiesof particularlyimportantbecause these were pre-

membersof leaguesperpopulation.All of these cisely the areas with the strongest regional

provincesalso had literacyratesof well over50 nationalistmovements.Valenciafollowedthese

percent(rangingfrom 51 percentin Umbriato regions.It was in the top five on five of the indi-

89 percent in Piedmont) and relatively high cators,andscoredsixthin the densityof employ-

densities of periodicals when controlled for ers' associations. Old Castile was in the top

population. five on fourindicators;Navarrethreeindicators;

Three associational censuses redacted in Aragon two indicators;and Galicia, Leon, and

1904, 1913, and 1928 give a similarpicturefor Asturias one each. Andalusia, Murcia, and

Spain.The Institutode reformassociales gath- Extramadurawere not in the top five on any of

eredthe informationfor the first two censuses. these indices. Even in its areas of greatest

The informationfor the thirdcensus was gath- strengththe Spanish associational sphere was

ered in preparationfor elections to de Rivera's probablyweakerthan its Italiancounterpart.

nationalassembly (Table2). Table 3 compares the two associational

This evidence, like the Italian evidence, spheres in terms of five indicators.In Italy by

shows sharpregionalimbalancesin the Spanish 1915, there were about 21 cooperatives per

associational sphere. The de Rivera survey 100,000inhabitants.In Spain,the corresponding

includes information on three main kinds of figure was about 3. In Italy,the socialist party

association:associationsof riches and produc- had entered parliament already by 1900 and

tion, workers'associations, and culturalasso- playedan importantrole in the strugglesaround

ciations.The othersurveysincludeinformation the turn of the century.In Spain, the socialist

on workers',employers',nonprofessionalasso- party did not enter parliamentuntil 1910, and

ciations(like choralgroups), and mixed work- it did not play an importantpolitical role until

ers and employers' associations. The bolded 1931 with the rise of the secondrepublic.By the

figures in each column representthe top five post-WorldWarI period,approximately5 per-

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

296 AMERICAN

SOCIOLOGICAL

REVIEW

Table3. CivicAssociationismin ItalyandSpainCompared

Indicators Italy Spain

Cooperativesper 100,000inhabitantsin 1915 21 3

Dateof the entranceof the SocialistPartyinto Parliament 1900 1910

Percentageof the PopulationEnrolledin SocialistUnionsin the post WWIperiod 5% 1%

Percentageof the Populationenrolledin a politicalpartyin the postWWIperiod 1.0% 0.2%

Numberof LiteratePersonspercopy of the majordailyaround1914 60 143

Percentof the Populationwho couldsign theirnamesin 1910 62 50

Sources:Forgacs,David. 1990. Italian culturein the industrialera 1880-1980: Cultureindustries,politics

and thepublic. Manchesterand London:St. Martin'sPress;Desvois, JeanMichel. 1978. "Lastrasforma-

ciones de la prensade la oligarquiaa principiosdel siglo."La crisis del estado espahiol:1898-1936, edited

by M. Tufionde Lara.Madrid:EditorialCuadernosparael DiAlogo;Degl'Innocenti,Maurizio. 1977. Storia

della cooperazionein Italia 1886-1925. Rome, Italy:Riuniti;Istitutode reformassociales. 1915. Avanceal

censo de asociaciones. Madrid:Imprentade la sucesorade M. Minuesade los Rios; Linz, Juan. 1967. "Five:

The PartySystem of Spain:Past and Future."PartySystemsand VoterAligments:CrossNational

Perspectives,edited by SeymourM. Lipset and Stein Rokkan.New York:Free Press; Seton-Watson,Hugh.

1967. Italy FromLiberalismto Fascism: 1870-1925. London,England:Methuen;Tortella,Gabriel.2000.

TheDevelopmentof ModernSpain. Cambridge,MA: HarvardUniversityPress.

centof thepopulationwas enrolledin the social- nificantly extend political and civil rights. In

ist unions in Italy,and only about 1 percent in both cases, conflicts pitting an alliance of rad-

Spain. In postwarItaly,about 1 percent of the icalizedurbanandruralworkersagainsta coali-

populationwas enrolledin one of the two mass tion of powerful industrialand agrarianruling

parties(the socialists or the popolari),while in classes and small landowners undermined a

Spainthe correspondingfigure was .2 percent. postwardemocratictrend.A countermovement,

In Italy,1 copy of the majordaily newspaperIl which emerged after the defeat of the revolu-

corrieredella sera circulateda day for every 60 tionarythreatbut presenteditself as a defense

Italians who could read, whereas in Spain 1 against revolution, formed the basis for an

copy of El debate circulated for every 143 authoritarianseizure of power in each country.

Spaniards.Finally,literacywas about12 percent But differences in the strengthof the associa-

higher in Italy than in Spain in 1910. tionalsphereaffectedthe organizationof author-

The evidencethen suggeststwo conclusions. itarianismwithinandbetweenthe two countries.

Associationism was regionallyuneven in both In Italy,where associationismwas well devel-

countries.In Italy,associationsconcentratedin oped, fascists developed a mass party organi-

Lombardy, Veneto, Emilia Romagna, and zation. In Spain, associationism had similar

Tuscany.In Spain,associationsconcentratedin effects, but since the associational sphere was

Cataloniaand the Basque countries.However, less developed, only regionally bound proto-

in Spain,the associationalspherewas general- fascist movementswere possible.

ly weaker and split by regional nationalism, ItalyemergedfromWorldWarI with a deeply

while this was not the case in Italy. shakenconservativegovernmentfacing a broad

democratic coalition based on demobilized

THEPOSTWARPOLITICAL

CRISES recruits (Tasca 1950:20). Most historical evi-

ANDAUTHORITARIANISM dence indicatesthatthe majorityof the warvet-

eranswere interestedin an expansionof Italian

IN SPAINAND ITALY

democracy, and the establishment of a con-

Spain and Italy entered into similar political stituentassembly.This political mood grew out

crises in the postwarperiod.The biennio rosso of democraticinterventionism,the movement

(red two years) in Italy, from 1918 to 1920, thathad pushedItalyto join the war on the side

resemble the trienio bolchevista (Bolshevik of the allies againstthe reactionarycentralpow-

three years) in Spain. Both were periods of ers. De Felice ([1965] 1995:469) writes, "the

social unrestfollowing a failed attemptto sig- idea [of a Constituentassembly]circulateda lit-

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDAUTHORITARIAN

CIVICASSOCIATIONS REGIMES

IN EUROPE 297

tie in all quarters of democratic and revolu- 1990:169). The agrarianunrestwas as threat-

tionary interventionism,and was not lacking ening as the anarchistagitationin Barcelona.

supporters even among the non-maximalist Esdaile (2000:241) writes, "Andalusiaexperi-

socialists." For example, the main veterans' enced a wave of strikesthatbroughtan increase

organization, the Associazione nazionale di in wages, a reduction in working hours, the

combattenti (The National Association of recognitionof anarchistunionsas defacto labor

Combatants)made this a central plank of its exchanges,andthe abolitionof piece works."In

program(Tasca 1950:20). some places, the strikeswere so successful that

The immediatepostwarperiodin Spain,and even the servants and the wet nurses of the

particularlyin Catalonia,bears many similari- landownersjoined forces with the day laborers,

ties to the Italian case. Here the conservative and men of property fled their estates to the

Lliga Catalanspearheadedan assemblymove- cities (Esdaile 2000:245). The monarchycame

ment that linked socialists, Catalan regional- to terms with the armyorganizedas the Juntas

ists and army reformers in a coalition that de defesa, an organizationformed in 1916 to

pushed for a constitutional convention. The protect the interests of junior officers whose

Lliga Catalandominatedthe movement,which salarieshad been underminedby postwarinfla-

also included political representatives of tion and who resented"specialpromotionsfor

Asturianand Basque heavy industry(Harrison africanista officers" (Payne 1967:184; Boyd

1976:912). As Boyd (1979:78) remarks, this 1979:76). The Spanishking Alfonso XIII met

was an "attemptat bourgeois revolution."In the demands of the military reformers and

both cases, however,an in partreal and in part immediatelyused the armyto crushthe social-

perceivedred threatscuttled the possibility of ist-anarchistalliance(Boyd 1979:82-5; Brenan

a gradualextension of democraticrights. Men 2000:65-9; Tusell 1990:159-60).

of propertyin both cases perceivedthis mobi-

lization as especially threatening because it THECRISES

COMPARED

includedboth agrarianand industrialworkers,

andbecause it came on the heels of the Russian Thus, in Spain and Italy,the basic social con-

revolution. ditions for right-wing mass mobilization were

Italyseemed on the brinkof social revolution present (Ben-Ami 1983:33-48). Preston

between 1918 and 1920. A mass socialistparty, (1990:13)writes,"Inmanyrespects,the Spanish

which had rejectedcollaborationin WorldWar crisis of 1917-23 is analogous to the Italian

I andwas explicitly committedto socialist rev- crisis of 1917-22." The combined effects of

olution, seemed poised to win parliamentary WorldWarI and the Bolshevik revolutionrad-

power. Strike activity increased dramatically icalized the industrialand agrarianproletariat

from 1918 to 1920 in both industryand agri- in bothcases (Carr1982:509).In differentways,

culture(Elazar1993:189).The old liberal61ites the political systems of both cases faced what

were withoutpolitical instrumentsto deal with were apparentlyinsurmountablecrises (Carr

these pressures. Trasformismohad basically 1982:489-97; Tusell 1990:94-8).

ceased to operate by 1913, but a truly bour- There was, however, a crucial difference

geois party had not yet developed (Chabod between the biennio rosso and the tri'enio

1961:41-2). bolchevista. In Italy, the crisis was intimately

The situation in Spain was similar. Since linked to the country'sparticipationin World

1917, strikes shook both Barcelona and the WarI. Spain, as a neutralcountry,did not face

Andalusiancountryside.The high point of this this problem.Given that fascism initially arose

strikewave in Barcelonawas the strikeagainst precisely as a war veterans' organization,this

an electrical firm called La Canadiense (The difference is crucial. One of the main conse-

Canadian),which shut down 70 percent of the quences of Italy'sparticipationin WorldWarI

power to the city for over a month (Tusell was precisely to exaggerate the differences

1990:167).Duringthe so-calledBolshevikthree between Italian and Spanish associational

years from 1918 to 1920, massive strikesbroke spheres already present in the prewarperiod.

out acrossAndalusia;andin Catalonia,the anar- Especiallyafterthe defeatat Caporetto,in which

chists, socialists, and right-wingorganizations the Austrianspushedthe Italianarmydeep into

fought one another in the street (Tusell its own territory,the war set offa wave ofasso-

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

298 AMERICANSOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

ciationismthatcontinuedinto the postwarperi- between fascist cell organizations and the

od (De Felice [1965] 1995:388-9; Gentile strengthof civic associationismprovidesstrong

1989:70-1). Italy'spostwarexperiencewas thus evidence for my argument(for a similar argu-

an instance of the broader phenomenon that ment, see Kwon 2004). Whatexplainsthis sur-

participationin mass mobilizing warfaretends prising relationship between the strength of

to be civic association building (Skocpol civic associationismand fascism?This section

1999:54-60). identifies two mechanisms. First, a relatively

In part,as a resultof this developmentin the strong associational sphere facilitated recruit-

associational sphere, the Italian state faced a ment. In this context, fascists could expandby

challenge of a different magnitude from its forminga federationof allied organizationsand

Spanishcounterpart.In Italy,the strikewave of penetratingenemy organizations.Second a rel-

1918-1920 combined with a serious electoral atively strong associational sphere provided

challenge by the socialist party,and to a lesser organizationaltechniquesthatthe fascist move-

extent the Catholics. In Spain, no such direct ment and partyadopted.

political challenge to the Restorationsystem

emerged.At no point in postwarSpaindid any

Thestrategyforfascistexpan-

RECRUITMENT.

political force challenge the monopoly of the

two dynasticparties (Linz 1967:212).The two sion, establishedby Umberto Pasella, the first

crises were thus socially similar,but political- general secretary of the fascist party, was to

ly different. multiplythe numberof cell organizations(fasci)

as rapidlyas possible. Pasella would contact a

local sympathizerwho would then organize a

CIVICASSOCIATIONISMAND

RADICAL PARTIES

RIGHTPOLITICAL foundingmeeting.The movementat the begin-

IN SPAINAND ITALY ning was internally highly democratic. Each

organizationwas autonomous in its policies,

How,then,did differencesin the strengthof and there was little formal doctrineconstrain-

the associationalsphereat both the regional ing the members (Gentile 1989:40-1). Emilio

and cross-nationallevels relateto differencesin Gentile (1984:253) writes the following:

the development of fascist movements and

movement,theFasci

As a self-styled'libertarian'

regimes in the two cases? A relatively strong di combattimento hadno statuteordetailedregu-

associationalsphereprovidedthe indispensable lations:organizationsand methodsof struggle

organizational environment for the develop- were dictatedby circumstances. Therewere no

ment of radicalright-wingmovementsin both ties of leadershipand memberscould also join

Italyand Spain.But the relativeweakness,and otherpartiesso longastheywerepatriotic andanti-

especially regional fragmentation, of the Bolshevik.Duringthis period[1919-1920],the

Spanish associational sphere meant that only ideologyandorganization of fascismwereformed

regionallyboundprotofascismscouldemergein spontaneously orby imitation,thanksto localini-

this case. tiatives,oftenonthepartof individualsandwhich

frequently provedephemeral.

ITALY Fascism in Italy thus became a mass move-

ment precisely by providingan alliance frame-

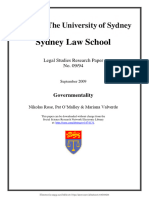

Figure 1 is an overlay of fascist cell organiza- work for variouspreexistingassociations.Two

tions per 100,000 people in 1921 on a map of these were especially important:patriotic

adapted from Robert Putnam's indicators of associationsandagrarianassociations.Patriotic

civic associationism from 1861-1920.2 Since associationshada prominentplace in the north-

Putnam's approach is explicitly neo- centralItalyfromthe 1860s (Ridolfi 1999:156).

Tocquevillian, the striking correspondence

They undertookvariouskindsof activities,such

as dedicatingmonumentsandconductingfuner-

al services. Wartime mobilization, basically

2 An earlierdraftof this in addi-

paperpresented, from 1915, gave a massive push to this form of

tionto thePutnammap,a mapusingtheindicators associationism. These organizations were

inTable1.Pleasecontacttheauthorforfurther infor- already in place well before the emergence of

mation. the fascist party in 1921.

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CIVICASSOCIATIONS

ANDAUTHORITARIAN

REGIMES

IN EUROPE 299

Most Civic

I..O V

I ~IE-R

T A

Least Civic

~LLA

..........

................

I..........

Most

Fascist

Cellsjijiiiiijii

SI

O

O

LeastFascist

Cells

Figure 1. Fascismandthe Strengthof CivicAssociationism

Note: Regionnameshavebeen abbreviatedas follows:AB = Abruzzi;AP = Apulia;B = Basilicata;CA =

Campania; CL = Calabria; E-R = Emilia-Romagna; LA = Lazio; LI = Liguria; LO = Lombardia; MA = Marche;

MO = Molise; P = Piemonte; SA = Sardinia; SI = Sicily; T = Tuscany; V = Veneto. Sources: Adapted from the

following:Putnam,RobertD. 1993.MakingDemocracyWork.Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress.

Reprintedby permissionof PrincetonUniversityPress.The informationon fascistcell organizationsis fromthe

following:Gentile,Emilio.2000. Fascismoe antifascismo.Ipartiti italianifrale dueguerre.Florence,Italy:Le

Monnier.

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

3oo AMERICAN REVIEW

SOCIOLOGICAL

Archival documentsprovide some sense of But fascism did not arisejust as an alliance

the Italian world of patriotic associationism, of patrioticassociations.The decisiveexpansion

among which the fascists first expanded. of the movementoccurredin the firstsix months

Consider a political meeting that Mussolini of 1921 as a result of its alliance with agrarian

attendedin Januaryof 1919 two monthsbefore organizations.These organizations,as I indi-

he decidedto foundhis own organization.This cated previously, emerged in response to day

was a meeting of various Milanese patriotic laborerand sharecroppingorganizationsin the

associationsto constitutea Milaneseassociation earlytwentiethcentury.They organizedstrike-

for the League of Nations.The ItalianNational breaking funds, financed local newspapers,

League and the Wilsonian Propagandagroup establishedbanksthatfunneledmoney to small

called the meeting, to which they invited the holders(in an attemptto alterthe agrarianclass

heads of 24 patrioticorganizations(ACS; MI; structure),and financedcooperativesand insur-

DGPS; 1919; Milano; Document 564). The ance for "freelaborers"who agreednot to join

meetingresolvedto founda new associationand the socialist leagues (Ministerodi Agricoltura

entrusteda committeeto drawup a statuteand Industriae Commercio 1912:13). The fascist

provide for financing. In April 1919, the movementgrafteditself on to this association-

Committee for the Defense of the Rights of al terrain.This gave it an anarchicand decen-

Italy met to decide what kind of relationshipit tralized character.Despite the efforts of the

should have to Mussolini's newly formedfas- urbanleadershipto control the financial basis

cio di combattimento.Approximately200 peo- of the movement, agrarianfascism was self-

ple were at the meeting, and there was lively financing.The fascists set up informaltaxation

debatein whichthe committeedecidedto coop- at the local level, and did not transferfunds to

erate with Mussolini's organization to form centralcommitteein Milan.The agrarifinanced

propagandasquads (ACS; MI; DGPS; 1919; local fascist organizationsandnewspapers,not

Milano; Document 2523). In May 1919, the Milanese leadership (De Felice [1966]

Mussolini'sorganizationwas cooperatingwith 1995:45; Gentile 1989:166-8). In that sense,

a larger umbrella group called the fascio of agrarianfascism was simply a re-editionof the

patrioticassociations(ACS; MI; DGPS; 1919; agrarianorganizationsof the prefascistperiod

Document 15933). Across northern Italy, (Gentile1989:166).Fascismin the firstinstance

numeroussuch associationsformedin the peri- was a broadalliance of two mainkinds of asso-

od from 1915 to 1919. At Cremona,Venice, ciations: veterans' associations and agrarian

Milan,Turin,and Modena, groupswith names associations.

like the League for Civil Defense, the Patriotic In addition to providing an alliance frame-

League, Social Renovation,the New Contract, work for the agrariansand the patrioticassoci-

and The Italian League for the Protection of ations, fascism penetrated the preexisting

National Interests formed the core of subse- structureof working class associationism.For

quent fascist cell organizations (Gentile example, RobertoFarinacci(1892-1945), sec-

1989:70-4). ond only in importance to Mussolini among

Thefascistmovement by

precisely

expanded fascist leaders,used his contactsin the railroad

providing a loose umbrella organizationthat unions, which he had establishedas a socialist,

welded these groups together. Indeed to build up a powerful local organization

Mussolini's initial aim in founding what he (Cordova 1990:45-53; De Felice [1966]

calledthefascio di combattimentowas "tounite 1995:506; Lyttelton 1987:171). Further,many

in a singlefascio with a single will all the inter- of the ruralleagues and chambersof labor,gen-

ventionistsand the combatants,to direct them erally underthe pressurefrom the fascist mili-

towarda precise aim, and to valorizethe victo- tia, passed over in their entiretyto the fascists

ry"(Chiurco1929:98-9). In line with this strat- in the early 1920s. This providedfascism with

egy, the fascist movement first burst onto the an immediate mass organizationin precisely

nationalpoliticalscene as an electoralbloc, and those areas where socialist associationismhad

then as a federationof local militia organiza- been most developed in the prefascist period

tions. Fascism formed as a political party only (Ridolfi 1997:340-2; Tasca 1950:164).

in November1921 (Gentile1989:316-84;Milza Regardingthe case of Ravenna,Italianhistori-

and Berstein 1980:113). an MaurizioRidolfi (1996:262)writesthatthere

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDAUTHORITARIAN

CIVICASSOCIATIONS IN EUROPE 3ox

REGIMES

"were several examples of self-dissolution [of ities of all fascist federations.In additionto the

agrarianleagues],oftenpassingdirectlyoverthe big national fascist papers, such as II Popolo

fascist syndicateorganizations." FromFebruary d'Italia, each federationhad its regionalpubli-

to April 1921, masses of peasant leagues and cation.Finally,the fascistfederationsdistributed

union organizationsshifted as a bloc to the fas- considerablesocial assistanceboth in the form

cists (Cordova 1990:42-3). The fascists also of small loans and in kind (this informationis

took over the entire structureof cooperative based on budgets containedin ACS; AF; PNF;

societies, erectingin 1926 the Entenazionaledi

DN; Servizi; Series I; boxes, 708, 714, 827,

cooperazione(NationalInstituteof Cooperation)

829, 1123, 1128 and Series II; boxes 1091,

(Degl'Innocenti1981:51).Fascistspurgedthese

1181, 1584).

organizationsof their previous leadershipand

then converted them to institutions linked to Further,the fascist partyused specific polit-

the party (Degl'Innocenti 1981:53). In 1928, ical techniques, especially drawn from the

after the operationof purging,there were still sphere of socialist associationism,to establish

over 3,000 cooperative societies in Italy with control over the working class. The clearest

over 800,000 members (Degl'Innocenti example of such a technique was the labor

1981:56). The fascists did not dismantle the quota. One of the key achievementsof social-

socialist organizations;they penetratedthem ist organizationsin the Po Valleywas the impo-

and used them to build their own mass organi- sition of a laborquotaon employersthatwould

zations. ease cyclical unemploymentamong day labor-

ers. Fascist unions generallykept labor quotas

ORGANIZATIONALTECHNIQUES.The Italian as a means of threateningagrarianemployers

associationalsphere, in additionto facilitating and winning some mass support (Lyttelton

recruitment,provided specific organizational 1987:223).

techniquesthatthe fascistsused in constructing Given the continuitiesbetween fascism and

theirown partyorganization.Manyof the asso- the prefascist associational sphere in terms of

ciations discussed previously undertookthree recruitmentmechanismsand organization,it is

maintypes of activity:resourcecollection, cul- not surprisingthat, where civic associationism

tural activities and social assistance. Fascist was less developed, especially in the south of

party federationsconducted all three of these

activitiesin ways thatwere strikinglysimilarto Italy,the fascist partyhad enormousdifficulty

consolidating.SouthernItalianfascism tended

prefascistassociations. to be one of three things: a criminalorganiza-

The agrarianorganizationsdiscussed in the

tion tied to the agrarians,a superficialpolitical

precedingsection dependedupon contributions

from local owners. Specifically, these usually cover for personalisticclienteles, or an apoliti-

took the formof "ordinarycontributions" based cal reform movement based on the military.

on the area of land held and income, and The weakness of southern fascism was

"extraordinary contributions"collected at fixed expressedin the greaterpowerthatprefectshad

rates for all the members (Ministero di in relation to the federal secretaries in these

AgricolturaIndustriae Commercio 1912:13). regions.Fascismas an autonomouspartyorgan-

This was exactly the principle method of ization remaineda phenomenonof north-cen-

resourcecollection used by the fascist federa- tral Italy (Colarizi 1977:156-63; Corvaglia

tions.The fascistpartysecretaryAchille Starace

1989:822; Lyttelton 1987:189-90). The rela-

(1889-1945) codified the distinctionbetween tively strong associational sphere in northern

ordinarycontributionsbased on ability to pay

and extraordinarycontributionsin an adminis- Italy, then, provided key organizational

resources for the development of the fascist

trative act in 1935 (PNF 1935:191-7).

Administrativedocumentsfromthe federations movement, and then party.Thus, in the Italian

themselvesshow thatthis distinctionwas wide- case, a relativelystrongassociationalsphere,far

ly used fromthe early 1930s. Further,prefascist from constituting a barrieragainst the devel-

Italian associations (both elite and nonelite) opment of an authoritarianparty,providedthe

were often linked to a newspaper.Funding a materials out of which the fascist party was

newspaperwas also one of the principleactiv- constructed.

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

302 AMERICAN REVIEW

SOCIOLOGICAL

SPAIN ecumenicalincludingeveryonefromthe fascists

to the old dynasticliberals(Ben-Ami 1983:131;

The same general relationshipholds for Spain

G6mez-Navarro1991:255-60). The UP had no

with the fundamentaldifferencethatde Rivera

affiliatedprofessionalorganizations,little doc-

did not come to power on the basis of a party

trinalbase, and an extremelyweak partypress.

movement, but ratherhe created a state party

afterthe seizure of power.To the limitedextent To join the party one had simply to be recom-

thatfascist-likemovementsemergedin Spainin mendedby a memberand pay an annualfee of

the early 1920s, they were located in the areas a single peseta (an incredibly small amount

of the countrywith dense associationalspheres. considering that the wages of a day laborerin

De Rivera's state party the Union Patri6tica the late 1920s were betweenthreeto five pese-

(UP) developed in part as an attemptto copy tas a day) (G6mez-Navarro1991:231-3). The

Italianfascism, and in part as a union of vari- UP was basically a new organizationfor the

ous spontaneous efforts to supportthe dicta- old politicalbosses or caciques.This was clear-

torship.Spontaneoussupportfor the de Rivera ly not an organizationthatprovidedthe regime

coup concentrated in Catalonia and the with structured support. One of the most

provincesof Old Castile. In Cataloniathe mili- remarkablefeaturesof the de Riveraregime is

tia organizationsreorganizedthemselvesintothe thatthe dictatordid not appealto supportfor the

Federacidn Civico-Somatenista. A group of UP when his othersources of supportbegan to

Catholic conservatives in Valladolid in Old decline in the late 1920s (Ben-Ami 1983:388).

Castileformedthe UnionPatrirticaCastellana

in November 1923. When de Rivera formally

THE REGIMESCOMPARED

launchedthe statepartyin April 1924, a "pow-

erful networkof Catholic syndicates,newspa- The existence of a strongauthoritarianpartyin

pers,andecclesiasticallay associations"formed Italy and the absence of such a political force

the initial basis of many party cells (Ben-Ami in Spain in part determined the differences

1983:130). The relationshipbetween Catholic between the two regimes. In both Spain and

associationismandthe UP is particularlystrik-

Italy, authoritarianregimes consolidated only

ing. As the researchof G6mez-Navarroshows, several years afterthe seizure of power.By the

two different types of UP cell organization mid 1920s, both had brokenwith even formal

emergedafter 1926. In the southin the areasof constitutionallegality(De Felice [1968] 1995:3;

large landholdingthe old political bosses from G6mez-Navarro1991:264).Butthe two regimes

the liberalperiodpenetratedthe UP.In the cen-

assumed an opposite stance towardtheir soci-

terandnorth,however,it was men coming from

social Catholicism,eitheras unionorganizersor eties. Italianlaborunions,professionals'groups,

leadersof local Catholicpolitical organizations and industrialists'groupswere forced eitherto

such as the Partido Social Popular (PSP) who dissolve or to become fascist organizations.

dominatedthe UP (G6mez-Navarro1991:255). This entailedformalpoliticizationof a rangeof

But these pockets of authoritarianmobiliza- previouslynonpoliticalorganizations.Thus,the

tionwereisolatedandthey couldnot supportthe Italianregime tended to become a hegemonic

developmentof a mass nationalpartyas in the authoritarianregime because it expanded the

Italiancase. The UP was nevera dynamicparty realm of politically relevant activity (Milza

organization.Its centraloffice was runout of the 2000:800). The Spanish regime, by contrast,

Ministry of the Interior.Furthermoremany of tendedto depoliticize the associationalsphere.

its memberswere stateemployeeswho hadbeen G6mez-Navarro(1991:394) writes the follow-

forced to join in order to keep their jobs. In ing:

additionformerpolitical bosses of the el turno

The regimeof Primode Riverasoughtandpro-

system flocked into the partyin ordergainjobs motedworkingclass and professionalassocia-

and patronage (Ben-Ami 1983:140). Thus tionismwhilerepressingandcurtailingpolitical

regionaldifferencesaffectedthe UP as much as associationism.

theyhadthe partiesof the el turno.TheCastilian

andCatalangroupscompetedto gain controlof One key reasonfor these differentoutcomes

the new state party.The dictator'sapproachto was the strengthof thepartyorganizationin Italy

these conflicts was to make the UP politically comparedto Spain.

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ANDAUTHORITARIAN

CIVICASSOCIATIONS IN EUROPE 303

REGIMES

FROM'LIBERAL

FASCISM'

T FASCISM

AS his own partyhad only 35 of the more than400

REGIME seats (De Felice [1966] 1995:479). His entire

policy from 1923 to 1924 was devotedto estab-

It was only fromJanuary1925 (threeyearsafter

the seizure of power in October 1922) that lishing a Giolittianstyle big majorityand then

Mussolini'sgovernmentbegansystematicallyto passingan electorallaw thatwouldfurthersolid-

eliminatelegal oppositionandsubordinateasso- ify this majority.In orderto govern, Mussolini

used exactly the same techniques that Giolitti

ciations to the fascist party (De Felice [1968] had perfectedduringthe previoustwo decades.

1995:220-1; Lyttelton 1987:269). The driving He workedto establisha big majorityof the cen-

forceof this processwas the fascistparty,which

ter by appealing to individualdeputies to join

mobilizedagainst Mussolini'sattemptto estab- his projectfor a big nationallist which most of

lish a personalisticregime closely resembling

the liberal deputies joined (De Felice [1966]

the parliamentarydictatorships of prefascist

1995:575; Sabbatucci2003:66-7). The regime

Italy.Thepartythusconstitutesthe linkbetween thatwould have emergedfrom such an alliance

associationism and hegemonic authoritarian-

would clearly have been much less hegemonic

ism in the Italian context. By the end of the

thanthe fascistregimeactuallywas, andit prob-

1920s the partyestablishedcontrolover Italian

ablywouldhaveclosely resembledthe de Rivera

society.Only approvedfascist unions, employ-

ers' organizations,and professional organiza- regime in Spain, as Lyttelton(1987:236) sug-

tions remained in effective existence gests.

That Mussolini was unable to establish a

(Rosenstock-Frank 1934:80-1). Oppositionpar-

ties were outlawed.Citizenshipwas now con- regime of this type is closely linked to the fact

sidereda privilege reservedonly to those who that it ran contraryto the basic interestsof the

demonstratedpolitical loyalty to the regime. fascist party.The formationof the party creat-

Like all hegemonic authoritarianregimes, it ed a social agent whose vital interestsconsist-

ed in politicallyincorporatingever-largerchunks

required citizens "to participate, and special

of Italiansociety.The moreunions,professional

rights and privileges [were] reserved to those

who demonstrate[d]theiractivecommitmentby organizations,andculturalactivitiescame with-

in orbitof the fascist partythe more posts there

joining the party" (Lyttelton 1987:149). The

fascistregimethus demandedactiveratherthan were for party members, and the more dues

would flow into the organization (Lyttelton

passive consent.

This outcome was in part the result of the 1987:236; Pombeni 1984:487). Even relative-

defeatof Mussolini'sinitialpostseizureof power ly limited political pluralismthreatenedthese

interests. Mussolini's maneuvering in 1922

strategyof establishinga personaldictatorship,

whichresembledin manyways the transformist through1924 had the predictablepolitical con-

governments of Giolitti. After the March on sequence of creating an intransigent fascist

Rome, Mussolinimovedto eliminatethe fascist alliance made of up the militia organizations

party as a major player by establishing an headed primarilyby Farinacci,and the union

alliance with the bureaucracy, the General organizations led by Edmondo Rossoni

Confederationof Labor(CGL),the confedera- (1884-1965).

tion of Industry,and a numberof majorpoliti- From 1923 to 1925, the Farinacci-Rossoni

cal leadersof liberalItaly(Cordova1990:177). axis organized a second wave of mass mobi-

The effort came close to succeeding.The CGL lization along two parallel lines: militia squad

initiallyseemed open to collaboration.In early mobilization and a union offensive. Squadrist

October 1922, the reformistunions renounced mobilization throughoutthe summer,fall, and

their alliance with the socialist party (Milza winter 1924 combined with a series of delega-

and Berstein 1980:180). Forthe next two years tions to Mussolini demandinga radicalization

an alliance between Mussolini and a depoliti- of the regime, constitutethe immediate back-

cized labormovement,seemed not only possi- ground for Mussolini's speech on January3,

ble butlikely (Cordova1990:168-78; De Felice 1925. This indicatedthe end of the parliamen-

[1966] 1995:617). Many of the leaders of lib- tary regime in Italy.From 1924 to 1926 a par-

eral Italy also seemed willing to cooperate. allel mobilizationof the fascistunions achieved

Mussolini's first government was a formally a fascist monopoly on labor representationin

constitutionalcoalition governmentin which April 1926 (De Felice [1966] 1995:453, 457;

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

304 AMERICAN REVIEW

SOCIOLOGICAL

Gentile 1984:259-60; Lyttelton1987:245-67; state,those of the provinces,those on theirown

Milza and Berstein 1980:180-7; Uva account, and those of "activities."All of these

1970:1031, 1052-3). representativeswere selected from these four

This analysis suggests then that the party groups,andstateemployeesandUP partymem-

was the key agent establishing a hegemonic bersmadeup a substantialpartof the assembly.

authoritarianregime in the Italian case. As However,highly specific interests, such as the

shownin the previoussection,the party'sdevel- Basque and Catalanbourgeoisies, the orange

opment in the Italiancase dependedupon the growersofValencia, andolive andwheat grow-

existenceof a strongassociationalsphere.Thus, ers, all had men in the Assembly without hav-

this institutionconstitutesthe key link between ing any formal relationship to the UP

associationism and hegemonic authoritarian- (G6mez-Navarro1991:277). The point of this

ism in the Italiancontext. assembly was largely to represent important

economic interests socially, but not politically

FRoMTHEMLITARY (G6mez-Navarro1991:282).

DIRECroRATE The de Rivera Spanishregime set up a sys-

TOTHECVIL DIRECTORATE

tem of labor relations that was modeled on

As in the Italiancase, it was initially unclearif Italian fascism. But there was a huge differ-

de Riveraintendedto breakwith the constitu- ence between them. The fascists established

tional set up of 1876 andthe old two-partysys- regime organizations for all interest groups.

tem associatedwith it. Thetransitionto a regime The de Riveraregime pursueda differentstrat-

in the Spanishcase occurredbetweenDecember egy.The regimerepressedcommunistandanar-

1925 and September1926 (Ben-Ami 1983:57; chist organizations and compromised with

G6mez-Navarro1991:265).Thereis little doubt socialist and Catholic ones. The split between

thatItalianfascism constituteda model for the these two strategies is apparentfrom the dif-

Spanish. De Rivera and the Spanish king ferentway that strikeswere handledaccording

Alfonso XIII traveledto Italy in November of to who led them. If the striking organizations

1923 (twomonthsafterthepronunciamento). To were affiliated with the communists or anar-

VictorEmmanuelIII (1869-1947), the king of chists, then they were turned over to general

Italy,Alfonso reportedlyintroducedde Rivera SeverianoMartinezAnido (1862-1938) at the

as "his Mussolini," and both stated that they Ministryof the Interiorandthereforedealtwith

hoped to "follow the path of fascist Italy" as a police matter.If the strikingorganizations

(G6mez-Navarro1991:129-30). The historical were affiliatedwith the socialists,andthus con-

connection between the two regimes makes sidered politically safe, EduardoAun6s Perez

theircomparisonespeciallyinteresting,because (1894-1967) at the Ministryof Labordealtwith

it demonstrateshow similar political projects the strikeas a matterof social policy (G6mez-

produceddifferentregimes, in differenthistor- Navarro 1991:412-3). Thus, the de Rivera

ical contexts. regime institutionalizedthe division between

The establishmentof the civil directorateand political and apolitical activity, a distinction

a nationalconsultativeassembly were the key thatthe Italianfascistregimedeliberatelysought

momentsin the turntowarda regime in Spain. to erase.Thus,while the Mussoliniregime after

The UP playedno role in this turn.The driving 1926, drilledworkers,professionals,and own-

force was de Rivera'sdesire to establishstruc- ers into organizationscontrolledby the politi-

tured civilian support (G6mez-Navarro cal organization of the fascist party, in de

1991:267). The lack of a strong authoritarian Rivera's regime the workers could belong to

partymeantthatlargeareasof societyremained any organizationthey liked, and owners inter-

outside any regime organizations.For exam- actedwith the regimelargelythroughtheirown

ple, the corporativistorganizationsof the de organizations (Ben-Ami 1983:292). Further,

Riveraregime in contrastto fascist Italyleft an unlikein fascistItaly,in de Rivera'sSpainwork-

only marginalrole for the stateparty.The basic ers could strike,as long as they made no polit-

principleof de Rivera'sconsultativeassembly ical demands(Ben-Ami 1983:309).

was representationon the basis of "interests" The Italianregime by 1926 consolidated as

ratherthanindividualrepresentation. Therewere a hegemonic authoritarianregime. In contrast,

four groups of representatives: those of the the de Rivera regime consolidated as an eco-

This content downloaded from 128.135.12.127 on Sat, 5 Jul 2014 16:52:19 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CIVICASSOCIATIONS REGIMES

ANDAUTHORITARIAN IN EUROPE 305

nomic-corporatedictatorshiprelyingon the tra- employees and small peasants,had among the

ditionalinstrumentsof the police andthe army, strongest intermediate associations in the