Professional Documents

Culture Documents

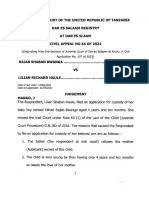

Jpdeg 76

Jpdeg 76

Uploaded by

Krisztina DávidOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jpdeg 76

Jpdeg 76

Uploaded by

Krisztina DávidCopyright:

Available Formats

Communication Theory ISSN 1050-3293

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism

Divide to Relationalism: Explicating Cultural

Assumptions in the Concept of

“Relationships”

R. S. Zaharna

School of Communication, American University, Washington, DC, USA

While the basic concept of “relationship” is pivotal to research and theory across a spec-

trum of communication studies, cultural assumptions about this basic concept may vary

significantly, and yet escape scholars’ awareness. This study exposes assumptions buried in

foundational U.S.-based Organization-Public Relationship (OPR) scholarship to illustrate

how differing assumptions about “relationships” correspond to understandings of commu-

nication processes and goals. “Relationalism” is introduced as an analytical lens to provide

insights beyond the dichotomous relational patterns of individualism-collectivism, explore

global perspectives, and help explicate a graduated range of relational assumptions that

challenge OPR theoretical premises. Relational assumptions identified in OPR scholarship

have heuristic value for communication areas that have “relationships” as a pivotal concept.

Keywords: Relationalism, Culture and Communication, Public Relations, Intercultural

Communication, Organization–Public Relations, Relationships.

doi:10.1111/comt.12058

The basic concept of “relationship” is pivotal to research and theory across a spectrum

of communication studies. For the field of public relations, “relations” is literally the

latter half of its name. In recent decades, scholarly attention has shifted from crafting

messaging to building relationships, specifically Organization–Public Relationships

(OPR). During the 1990s, OPR emerged as “a magic elixir for improving public rela-

tions theory and practice” (Heath, 2013, p. 246). Relationships have become the most

researched topic (Grunig, 2006), while relationship management is the prominent

research paradigm (Brown & White, 2011).

Public relations is not alone in the increased focus on the interactive, co-creational

significance of relations (Botan & Taylor, 2004; Jahansoozi, 2006). Communication

studies have witnessed an intensified research focus on relational processes (e.g.,

Corresponding author: R. S. Zaharna; e-mail: zaharna@american.edu

190 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

dialogue, Ganesh & Zoller, 2012), relational structures (e.g., networks, Castells, 2012),

and relational concepts (e.g., social capital, Kikuchi & Coleman, 2012). Curiously,

coinciding with this relational turn is not only the proliferation of global commu-

nication tools, but also the globalization of communication scholarship. Again, this

phenomenon has occurred in public relations (L’Etang, 2009; Sriramesh, 2012) and

across communication studies (Calhoun, 2011).

The growing globalization of communication research raises the question of cul-

tural assumptions that scholars may inadvertently fuse into their research. The sub-

tlety of cultural assumptions in research can shape what questions scholars ask, and

equally important, the ones scholars fail to ask. To illustrate how assumptions tied to

basic concepts can reverberate to the theoretical level and shape overarching com-

munication goals and strategies, this study explicates cultural assumptions tied to

“relationships” in OPR scholarship. Reviews of OPR scholarship reveal predominance

of U.S. scholars in laying the foundation of OPR theory (Ki & Shin, 2006; Meng,

2007). This early dominance may have acted to establish a normative perspective (Dis-

sanayake, 2009; Sriramesh, 1992, 2012). The predominance of U.S. scholarship in the

study of “relationships” is further noteworthy given the dominant U.S. cultural ideal of

the “autonomous individual” and individualism (Condon & Yousef, 1975; Stewart &

Bennett, 1991). Individualism, with its premise of autonomy, is inherently a relational

construct.

OPR scholarship may be a particularly apt illustration, given that it is informed by

and informs other communication areas. An extensive review by Jahansoozi (2006)

maps the wide expanse from interpersonal communication, to organizational theory,

to marketing to conflict resolution literature that informs OPR scholarship. In turn,

applications of OPR scholarship span from highly localized settings in communica-

tion management studies (Jo, Hon, & Brunner, 2004) to global public diplomacy stud-

ies concerned with relations between nations and global publics (Fitzpatrick, 2007).

Noteworthy, these subfields share with public relations a predominance of founda-

tional U.S. scholarship (Monge, 1997; Schramm, 1997).

The question of culture in OPR scholarship has been examined (Hung, 2004;

Hung & Chen, 2009; Ni & Wang, 2011). However, similar to other communication

fields, studies focus on cultural comparisons using the individualism–collectivism

(IND/COL) model (Hofstede, 1980). While the IND/COL model is one of the most

popular cultural tools in communication studies, researchers are finding troubling

inconsistencies (Taras et al., 2014). Important to the current study, the model is also

of Western origin and both “individualism” and “collectivism” are relations-based

concepts. Thus, the model may reinforce rather than expose cultural assumptions of

“relationships.”

This study adopts a critical, interpretative approach using methodological rela-

tionalism as an analytical lens to explicate assumptions about “relationships” from

various intellectual heritages. A series of 10 graduated assumptions is presented that

spans from communication and relations to communication-as-relations. The study

seeks to open conceptual space between the IND/COL divide and serve as a catalyst to

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 191

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

explore further assumptions in other areas of contemporary communication studies

that hold “relationship” as a central concept.

The long shadow of individualism

As intercultural scholars have long noted, what culture hides, it hides best from its

own members (Hall, 1976). The search for buried cultural assumptions in founda-

tional U.S.-based OPR scholarship begins with premises tied to U.S. cultural ideals.

Scholars have identified the primacy of the individual and individualism as the most

prominent features observed in the dominant U.S. culture (Bellah, 1987; Condon &

Yousef, 1975; Stewart & Bennett, 1991). The ideal of individualism is notable by not

only its prevalence but also its durability and resilience. Individualism was linked to

survival in the founding and settling of the United States (Samovar, Porter, & Jain,

1981). Alexis de Tocqueville first coined the term during his visit to America in the

1830s. Nearly two centuries later, individualism continues to distinguish Americans

in global attitude surveys (Kohut & Stokes, 2007).

As a core American value, individualism carries with it several corollary ideals

that influence perceptions of relations and communication. Condon and Yousef high-

lighted the “fusion of individualism and equality,” symbolized by the individual stars

on the U.S. flag, “each star independent but equal” (1975, p. 64). The ideal of equal-

ity may yield the corresponding preference for horizontal, peer-to-peer relations

(Triandis, Brislin, & Hui, 1988). The normative assumption of “relations among

equals” makes relational inequities and asymmetries suspect. Inherent in indi-

vidualism is autonomy and independence. Scholars have highlighted tensions

between the desire for freedom and choice of the individual versus the commitments

and obligations of social groups (Markus & Kitayama, 1994; Stewart & Bennett,

1991).

The cultural ideal of individualism in contemporary communication scholarship

has long been noted by intercultural communication scholars (Ishii, 2006; Kim,

2002; Miike, 2003). Min-Sun Kim (2002) identified the autonomous individual as the

underlying premise of major Western theories used to explain and prescribe commu-

nication behaviors. These theories span from cognitive dissonance (that rests on indi-

vidual consistency rather than social conformity) to speech apprehension (that values

self-assertion over silence). As Kim stated about the assumption of individualism:

“One does not question a fact that appears to be self-evident or natural” (2002, p. 4).

The assumption of the autonomous individual has several inter-related relational

implications for communication. First, as scholars have noted, the individual is the

primary level of analysis (Kim, 2002; Miike, 2006). The importance of a communi-

cator’s style and delivery as focal points heralds back to Aristotle’s Rhetoric. Second,

by definition of being autonomous and separate, no prior relation or social connec-

tion is presumed. In fact, communication is the process by which the autonomous

individual forms relations. Noteworthy, relationships are created through individual

agency. The idea of “individual agency,” which dates back to ancient Greece (Nisbett,

192 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001), remains a critical assumption of contemporary

communication. Interpersonal communication scholarship suggests a correlation

between the quality of one’s communication and one’s relations with others (Wood,

1995). Conceptually, communication (process or tool) is distinct from relations

(product).

Third, because the autonomous individual is separate, communication would by

necessity be what Carey (1989) described as “transmission process” of sending some-

thing from one entity to another. The communication weight falls on the message.

Studies on ways to enhance message design (e.g., framing) and delivery (e.g., medium)

as well as message impact (effect) have been key areas of communication research.

These communication assumptions associated with the autonomous individual

surface in public relations as well. OPR’s contribution was in challenging some of these

assumptions. Ferguson (1984) highlighted the oversight of relations in public rela-

tions scholarship and questioned the primacy of messages. Subsequent scholars advo-

cated a shift in focus from messages to relationships (Bruning & Ledingham, 2000;

Grunig, 1993).

Following initial arguments for greater attention on relationships, two strands

of foundational OPR theory emerged. One strand focused on defining and measur-

ing the qualities of an OPR (e.g. Bruning & Ledingham, 1999; Grunig, Grunig, &

Ehling, 1992; Hon & Grunig, 1999). Many of the OPR qualities echo those found

in interpersonal relationships (e.g., Wood, 1995). For example, Hon and Grunig’s

(1999) scale included trust, control mutuality, commitment, and satisfaction. Sim-

ilarly, Kent and Taylor’s (2002) widely cited that dialogical theory contains features

such as empathy and risk. A second strand studied the cultivation, monitoring, and

maintenance of relationships (e.g., Broom, Casey, & Ritchey, 1997; Hon & Grunig,

1999; Ledingham & Bruning, 1998). Broom et al.’s (1997) early model spanned

relational antecedents, properties, and consequences. Subsequent models detailed

specific actions and their sequence that organizations can take to cultivate, maintain,

and end relations. Ledingham (2000) spoke of a relationship cycle, borrowed from

interpersonal communication.

The relational foci and approach in early theory building were replicated in

subsequent OPR scholarship. Recent reviews found that the majority of the studies

construct OPR as antecedents or outcomes of relationships rather than processes

or properties (Huang & Zhang, 2012; Ki & Shin, 2006; Meng, 2007). The most

frequently cited outcome variable was satisfaction, followed by commitment, trust,

mutual understanding, control mutuality, and benefit. As Huang and Zhang (2012)

observed, while earlier OPR scholarship focused on scale development, subsequent

research has emphasized application of those scales.

Scholars have begun to expand foundational OPR scholarship by exploring

relational forces, such as power (Holtzhausen & Voto, 2002), which may affect OPR.

Recent scholarship has also highlighted different OPR applications such as crisis

(Jahansoozi, 2007) and public diplomacy (Fitzpatrick, 2007; Vanc, 2010). One also

finds scholars questioning the predominance of quantitative approaches and calling

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 193

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

for more qualitative studies to explore relational dynamics (Chia, 2006; Hung, 2005;

Jahansoozi, 2006).

As mentioned earlier, scholars have also probed cultural dimensions of OPR

(Hung & Chen, 2009; Ni & Wang, 2011) using the popular IND/COL model

(Hofstede, 1980). The model offers a simple and powerful explanatory tool for behav-

ior differences (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002). However, it has long been

controversial (Earley & Gibson, 1998; Schwartz, 1994; Voronov & Singer, 2002). The

dichotomous nature of IND/COL, for example, suggests a reductionist, binary view of

relations (Brewer & Chen, 2007; Oyserman et al., 2002). Individualism at one end of

the spectrum privileges the individual perspective, actions, and goals. Collectivism, at

the opposite end, privileges the group perspective, actions, and goals. The deperson-

alized “collective” fails to capture personal nature of relations (Brewer & Chen, 2007;

Kashima & Hardie, 2000). The model often prompts scholars to contrast relational

extremes (Taras et al., 2014) and discount the possibility that individualistic societies

may have collectivist traits (Triandis, Bontempo, Villareal, Asai, & Lucca, 1988) or,

that both dimensions may exist simultaneously (Sinha, Sinha, Verma, & Sinha, 2001).

For example, the in-group/out-group distinction often associated with collectivist

societies has been found to be equally, if not more pronounced in individualist soci-

eties (Brewer & Chen, 2007). A recent meta-analysis of decades of IND/COL research

revealed so many inconsistent findings that the researchers suggested the model was a

“naked emperor” (Taras et al., 2014). Rather than being mutually exclusive, IND/COL

may be mutually compatible, and even desirable: “In every society people must be

able to satisfy both individual and collective needs, that is, no culture, group or society

is per se ‘individualistic’ or collective” (Kreuzbauer, Lin, & Chiu, 2009, p. 742).

If the means for exploring cultural assumptions is in doubt, the necessity of explor-

ing cultural assumptions has gained urgency as scholars from different cultural her-

itages join the dialogue on OPR. An important reminder about individualism is that

it is not only a defining and enduring U.S. cultural ideal but also, as Kohut and Stokes

(2007) noted, a distinguishing one. In other words, the ideal of individualism and

the associated assumptions may not be shared by other societies. If individualism is

not universal, how do unshared assumptions about individualism intervene in basic

understandings about “relationships” and “communication” in OPR? In addition, just

as U.S. scholars may have inadvertently infused the OPR scholarship with cultural

assumptions, one could ask what assumptions might scholars from different cultural

heritages bring to OPR research? Again, given that OPR is informed by and informs

other communication areas, addressing these questions has implications beyond OPR

in public communication theory.

Methodological relationalism

While the realization of the need to explore assumptions related to “relation-

ships” may be growing, the means to explicate cultural assumptions requires a new

approach. This study adopted a critical, interpretive approach using the analytical

194 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

lens of relationalism. While relationalism appears relatively new to communication

studies, it has appeared with growing frequency across the social sciences. In Western

scholarship, relationalism originated in social psychology (Brewer & Chen, 2007;

Kashima & Hardie, 2000; Ritzer & Gindoff, 1992) and sociology (Emirbayer, 1997).

Relationalism is not confined to Western scholarship. Asians scholars have also

spoken of an Asian and specifically Chinese theory of relationalism (Ho, Peng, Lai, &

Chan, 2001; Huang, 2003; Hwang, 2000; Miike, 2006), stemming from the Confucian

emphasis on relationships.

Ritzer and Gindoff (1992) proposed methodological relationalism as a metathe-

oretical lens parallel to methodological individualism and methodological holism.

Methodological individualism focuses on the individual as the unit of analysis and

privileges the individual perspective, while methodological holism focuses on the

society or group as the unit of analysis and privileges the macrolevel perspective. The

third dimension, methodological relationalism, focuses on relationships and privi-

leges the relational perspective. Most importantly for this study to understand cultural

assumptions associated with “relationships,” the nuanced relational lens opens up a

conceptual space between individualism and collectivism.

Relationalism provides an analytical lens for what Krog described in lay terms in

the African context as learning “to read interconnectedness” (2008, p. 212). Studies

employing relationalism offer a nuanced view of relations, including the multiple

dimensions and types of relational ties, relational contexts, processes, and structures.

A critical aspect of relationalism is its distinction from collectivism. Collectivism,

as portrayed in the literature, suggests a “depersonalized,” (Kashima & Hardie,

2000) or “generalized other” (Triandis, Bontempo, et al., 1988; Triandis, Brislin,

et al., 1988). Relationalism focuses on the personalized, specific relations (Brewer &

Chen, 2007; Kashima & Hardie, 2000). While collectivism may focus on the level

of group categories, such as in-group/out-group or demographics, relationalism

focuses on the actual relations between the persons within the collective. Ho (1998),

for example, used relationalism to distinguish between “person-in-relationS” and

“personS-in-relation.”

Huang (2003) used Chinese relationalism to construct an indigenous Chinese

view of relationships in OPR, which she described as relational fatalism, relational

determinism, relational role assumption, relational interdependence (reciprocity),

and relational harmony (pp. 257–258). However, Huang may have forfeited the

nuanced view accorded by relationalism by contrasting the Chinese and American

relational perspectives using the dichotomous individualism/collectivism lens. The

current analysis follows Huang’s (2003) lead in adopting the heuristic value of rela-

tionalism as an analytical lens, but broadens its vision and application to other cultural

contexts and focuses on the nuanced graduations in assumptions about relations.

The research began with a review of U.S.-based foundational OPR schol-

arship cited in the literature surveys (Huang & Zhang, 2012; Ki & Shin, 2006;

Meng, 2007). Research then expanded to an interdisciplinary exploration of public

relations-related fields such as intercultural communication, international marketing,

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 195

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

and international advertising with a goal of compiling discussion of “relations,”

“relationship,” and communication from different intellectual heritages around the

globe. Culturally, research began with broad “Western” and “non-Western” cultural

categories, and progressed to specific geographic regions and prominent cultural

heritages (e.g., African, Asian, Arab, European, and Latin).

At each cultural location, an intellectual immersion in the literature (similar to

a physical emersion in the region) was performed in an effort to identify terms and

concepts tying relations and communication. The goal was to identify, as Pedersen

advised, “culturally biased assumptions and their reasonable opposites” (1988, p. 39).

By developing lists of distinctive terms, prominent features, and recurring themes at

various cultural venues, relational themes began to emerge. As the body of literature

grew, observations were sorted first by cultural heritage, then by emerging relational

themes. As the various relational themes emerged with greater clarity, the assumptions

about relationships in foundational OPR also gained saliency.

Exploring relational assumptions

The following analysis proceeds from observations of cultural perspectives closest

to the cultural heritage of U.S.-based foundational OPR scholarship, such as West-

ern Europe, to those more culturally distant in East Asia. Rather than posing stark

contrasts of individualism/collectivism, relationalism allows a view of nuanced and

graduated differences in assumptions about relations.

Assumption #1: Communication–relationship link

The first nuanced difference in assumptions surfaced in the link between relationships

and communication. Foundational U.S.-based OPR scholarship suggests a separation

between the two concepts. Ledingham, for example, described “relationships—not

communication—as the domain of public relations,” and communication acts “as a

tool in the initiation, nurturing, and maintenance of organization-public relation-

ships” (2006, p. 466). In scholarship originating from Europe, communication and

relationship are conceptually linked. Verčič and van Ruler (2004) found in their study

of public communication in 25 European countries that practitioners tended not to

distinguish between communication and relationships and instead used the terms

interchangeably. As the scholars note, “From our research it is clear that—in Europe

at least—even public relations researchers find it difficult to distinguish communica-

tion and relationships. What one researcher considers ‘communication’ may be called

‘relationships’ by another” (pp. 3–4).

The significance of the link between communication and relationships raises ques-

tions about OPR’s assumed instrumental view of communication as a tool for building

relations. The interchangeability between communication and relationships may sug-

gest a parity between the two or that the two are inseparable. These observations

warrant caution in assuming cultural congruence in U.S. and European scholarship.

Subsuming both under the cultural label of “Western” may obscure subtle but critical

196 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

relational assumptions. In other cultural heritages, as shown later, communication

and relations fuse still tighter.

Assumption #2: Sociocultural context of relations

A second observation is the assumption of a social context of relations. Founda-

tional OPR scholarship focuses exclusively on the dyadic relationship between the

organization and public (Heath, 2013). There is no mention of context. In European

scholarship, the social context emerges quite prominently (Bentele & Nothhaft; 2010;

Valentini & Nesti, 2010). The contextual assumption may stem from the German

sociologist Jürgen Habermas’ (1962/1991) writings on the “public sphere.” Relations,

and presumably OPR, do not occur in a social vacuum, but within the “public

sphere.” Verčič, van Ruler, Butschi and Flodin (2001) suggested that concern with the

“public sphere” distinguishes European public communication from the American

focus on “publics.”

In turning to Asian scholarship, Indian scholars highlight the assumption of the

cultural context of relationships. “The culture remains for the Indian all pervasive, a

kind of ruling principle, an intangible order of values and relationships,” notes Reddi

(1985, p. 6). The importance of culture relates to the great diversity found in India’s

public sphere, which as Reddi describes, is “a highly complex jigsaw puzzle of four-

teen major languages, at least five major religions and races, different music and dance

forms” (1985, p. 6). The absence of culture in early OPR literature may suggest a cul-

tural homogeneity between the organization and the public. A notable exception of

cultural texture in OPR scholarship is Huang’s (2001) scale, which incorporated the

Asian concepts of “face and favor.”

Assumption #3: Relational spheres

A third observation refines the assumptions of context from the general public

sphere to specific “relational spheres.” Foundational OPR’s focus on the dyadic rela-

tion between the organization and public implicitly excludes other relations. Latin

American scholarship’s relational emphasis on the family as the center of social

gravity and communication (Korzenny & Korzenny, 2005) introduces the idea that

relationships do not occur in a social vacuum or form independent of other relation-

ships. Instead, relations are part of a circle of other relations, or “relational spheres.”

The idea of relational spheres is also found in Asian scholarship. Chinese social

anthropologist Fei Xioatong (1941/1992) proposed the idea of “differential mode of

association” to describe the concentric circles of interpersonal and social relation-

ships that radiate out from each individual entity and overlap with the concentric

circles of others. This image puts individuals at the center of an ever-expanding circle

of relationships that moves from close, strong relations to more distant and weaker

ones (Chang & Holt, 1991). Noteworthy, the assumption of relational “distance,”

in Asian literature (e.g., Chang, 2007; Fei, 1941/1992), is not physical or cognitive,

but emotional.

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 197

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

More recently, scholars have drawn attention to the need to look at the OPR

as multidimensional relations (Heath, 2013). The idea of relational spheres further

challenges OPR research to expand research concerns from measuring relational

qualities to identifying external relational forces. Relational spheres also diffuse the

binary assumption of individual-or-collective relational pattern. A single, significant

relation may outweigh the entirety of “the collective.” Understanding where, how,

or why relational spheres overlap may hold fruitful avenues of inquiry in initiat-

ing dialogue or mediating relational conflict. Relational spheres also surface the

emotional dimension of relationships. While emotions are an intuitively important

relational determinant, they have been understudied in OPR and public relations

(Muskat, 2014).

Assumption #4: Relationality and identity

An assumption that follows from the relational sphere is that an individual is

embedded in relations and that these relational ties (relationality) can be an impor-

tant anchor of an individual’s identity. The early Arab sociologist Ibn Khaldun

(1332–1406) suggested the concept of “asabiyah,” or “group feeling” and “group

consciousness.” This strong group bond is often the defining feature that scholars use

to categorize Arab societies as “collectivist” (Hofstede, 1980). However, to look inside

the Arab society, one finds that aspects of individualism are equally pronounced

(Ayish, 2003).

Condon and Yousef (1975) help bridge this apparent paradox of individualism

coexisting with collectivism by highlighting the idea of “individuality.” While indi-

vidualism may suggest independence from the social group, far more common, say

the scholars, is “individuality,” which “refers to the person’s freedom to act differently

within the limits set by the social structure” (1975, p. 65). Individuality provides con-

ceptual space for individual self-definition for being a part or member of a collective

without necessarily being apart or separate from the group. Individuality may enrich

OPR scholarship, and other individual-group relational dialectics (Baxter, 2004;

Hung, 2006). Individuality also raises the importance of identity. Identity negotiation

is fundamental to relational dynamics, yet the cocreative process of identity for an

organization or public has been understudied in OPR scholarship (Theunissen, 2014).

Assumption #5: Relational commitment

Another evolution in assumptions is the shift in the strength of relational ties from

temporary and utilitarian connections created by individuals to enduring relational

commitments beyond the volition of individuals. In OPR scholarship, commitment is

often linked to perceptions of trust, reciprocity, and equity of exchanges (Jahansoozi,

2006). In African scholarship, the primacy of relational commitment is inherent in

the idea of “communalism” (Asante, 1998; Hecht, Jackson, & Ribeau, 2003). Commu-

nalism, as Nwosu explains, “represents commitment to interdependence, community

affiliation, others and the idea of we” (2009, p. 169). Scholars tie communalism to the

Zulu word, ubuntu, which suggests “the inter-connected humanness,” and the idiom,

198 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu, which suggests a person is a person through other per-

sons (Nwosu, 2009). As Antjie Krog explains not only is “one human by being in

relationship,” but being severed from important relationships can be equated with

death (2008, p. 207). The Igbo people of Eastern Nigeria would say, “A person who

is not with his or her extended family must bury himself ” (Nwosu, 2009, p. 169).

The expression again underscores the link again between identity and relations. More

poignantly, the importance of communal membership suggests that attempts to sever

a relationship may be socially costly, if even an option.

From the perspective of the autonomous individual, who by definition is not con-

nected to others, it is possible to speak of individual choice as well as agency in creat-

ing, building, and ending relationships. Foundational OPR theory similarly conveys a

relatively casual view of initiating and ending relations. OPR, including “relationship

management,” is predicated on the assumption that the organization, as the commu-

nicator, selects and manages the relationship with publics. Broom et al. (1997) spoke

of relationship “antecedents” in building relations. Ledingham (2000), drawing from

interpersonal communication, incorporated the idea of “relationship cycle” into his

OPR model that spanned from the start to end of a relationship. “Cycle” suggests that

ending relationships is not only inevitable but a natural process. This assumption may

not be shared globally by publics in OPR.

Assumption #6: Relational role responsibility

A sixth graduation in relational assumptions moves from commitment to role

responsibilities in relationships. The African assumption of communal membership

carries with it expectations of fulfilling obligations to the rest of the community.

The intent of shared relational responsibility is reflected in the saying, “It takes a

village.” The idea that each member has a specific, socially defined responsibility

is captured in the expression: “A child’s hands are too short to reach a high shelf,

but the elder’s hands are too big to enter into a narrow gourd.” This expression also

illustrates the idea that relational obligations to others are not inherently oppositional,

but aligned, shared, and expected. The assumption of “Self” as oppositional to the

“Other” or “Others” (collective) is absent. Instead, the Other implies fellowship and

responsibility.

The differing assumptions about individual choice in creating relations and

responding to relational expectations from others has cascading implications for

relational concepts such as trust, mutuality, and satisfaction in OPR research. For

example, satisfaction was the most frequently cited OPR dimension (Ki & Shin, 2006).

Because relations are primarily the prerogative of the individual, a lack of satisfaction

may be sufficient cause to break the relationship. The African perspective suggests

relational commitments may supersede relationship satisfaction and that relations

would be maintained despite dissatisfaction. Moreover, because relational duties are

tied to social roles rather than individuals, the rationale for responding to relational

responsibilities may be based solely on a desire to meet socially defined norms.

The idea of fulfilling social expectations of relational responsibility as an aspect of

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 199

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

“rational behavior” may help expand understandings of communal and exchange

relations in OPR (Hon & Grunig, 1999) as well as social capital in community

cooperation (Willis, 2011) and collective action (Kikuchi & Coleman, 2012).

Assumption #7: Relational complexity and hierarchy

A distinctive assumption that emerged in Asian scholarship is the complexity of

relationships, including the assumption of relational differentiation and hierarchy.

Relational complexity permeates Confucius discussions on relations (Yum, 2007).

For example, the five cardinal relations—parent/child; elder sibling/younger sibling;

husband/wife; friend/friend; ruler/subjects—like the fingers on one’s hand, are

different. Each relation has its different degrees of intimacy and obligation (Chang &

Holt, 1991). Huang summarized these differences: “closeness between father and son,

righteousness between superior and subordinate, differentiation between husband

and wife, hierarchy between elder and younger, and trustworthiness between friends”

(2003, p. 262).

Relational complexity challenges the equity assumption in foundational OPR,

which favors equitable, symmetrical relations despite obvious differences in power,

status, and resources between organizations and publics. Adherence to the ideal of

relational equality may cause scholars to focus on positive aspects (i.e., satisfaction

and trust) in OPR and overlook negative relational dynamics (Ganesh & Zoller,

2012) as well as negative types of OPR relations, such as exploitive and manipulative

relationships (Hung, 2005).

Assumption #8: Relational constellation and relational strategies

The assumption of relational spheres and complexity in the varying types, roles, and

responsibilities of relations suggests a predefined relational structure or relational

constellation. This assumption would imply that relationships precede communi-

cation. Because relations precede communication and because of the complexity

of relations, individuals must know the nature of a relationship and its position

within the relational constellation in order to communicate. In other words, relations

define communication. The relational primacy of communication puts a premium

on relational strategies over messaging or media strategies. Individuals use their

knowledge of relational structures, dynamics, and strategies to achieve their goals

through relationships (Chiao, 1989; Chung, 2011). Individuals use their relational

acumen to navigate through relation spheres to obtain individual advantage (Chang

& Holt, 1991; Hwang, 1987). Because relational strategies rely on the stability of the

relational structure and a degree of predictability in relational roles, one might expect

a shared need for order and balance of the relational constellation rather than a desire

to change it.

The assumption of a relational constellation challenges OPR theory to expand

its vision from identifying the features and strategies of individual dyadic relations

and individual agency to mapping the larger relational constellations, identifying

advantageous relational positions, and developing strategies for navigating relational

200 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

constellations. Meeting this challenge suggests integrating network studies into OPR

so that researchers can envision relational structures and strategies beyond the dyad

(Yang, Klyueva, & Taylor, 2012). Also, because relations carry the communication

weight in a predefined relational structure, a greater understanding of relational

strategies (e.g., Chung, 2011) that do not rely on messaging and media components

is needed.

Assumption #9: Holistic, mutually influencing relations

Another prominent feature found in Asian scholarship is the assumption of holis-

tic relations. A holistic perspective suggests an ever-expanding, comprehensive uni-

verse of relations (Gunaratne, 2010). Such a view would envelop the coexistence of

opposites as natural (Fang & Faure, 2011). A holistic perspective also extends inward

to view relations as “inter-locking, inter-connected and inter-penetrating” (Shi-xu,

2009). Part of the difficulty in “breaking” relations mentioned earlier is that the rela-

tions are intertwined. The premise of relations as mutually influencing suggests a rela-

tional dynamic of constant change as each party encounters differences in the other(s)

and seeks to learn and adapt to those differences. The coexistence of opposites and the

need for continuous change and adaptation are symbolized by the flowing, wavy line

(as opposed to static straight line) in the yin-yang symbol. As such, the yin-yang is

not a division of two opposites, but a holistic vision: one circle. Sinha reflected on

Western notions of “human and society,” and “human in society,” as distinct and sep-

arate entities, and the Indian view of “human-society,” as an inseparable, symbiotic

relationship (1998, p. 19). The holistic “human-society” perspective underscores the

appeal and recurring theme of harmony that permeates Asian literature. Assump-

tions of mutually influencing relations would promote, as Shi-xu (2009) noted, the

desire for cooperation, coordination, and harmony. G.-M. Chen (2001) identified har-

mony as a cardinal value in Chinese philosophy and proposed a “harmony theory” of

Chinese communication. Harmony does not imply absence of conflict but does neces-

sitate relational strategies for mediating conflict in ways that preserve the relational

structure (Chang, 2007; Chiao, 1989).

The mutually influencing assumption of holistic relations raises questions for

foundational OPR scholarship about who manages who in OPR, the organization

or the public? The assumption of mutual influence makes the idea of one-way

influence suspect. This is a point underscored in recent studies of relations between

organizations and activist publics (Uysal & Yang, 2013). The interconnectedness of

holistic relations also raises questions related to conflict and crisis. Assumptions

of the autonomous individual may spawn the idea that “conflict is natural,” as well

as the need for explicit conflict management through tactics such as transparency

and openness (Jahansoozi, 2006). Assumptions of holistic, interrelated relations may

minimize expectations of conflict as well as the need for communication openness.

Given the assumption of coexisting opposites as natural, one might expect advanced

relational strategies to focus on monitoring other/s, self-adaptation, and realignment

as strategic approaches for dealing with differences found in others.

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 201

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

Assumption #10: Relational being

Perhaps the most pronounced relational assumption that emerged in Asian litera-

ture is the idea of “relational being” (Ho et al., 2001; Huang, 2003). The perspective of

human-society or “relational being” deflates the necessity of human agency in creating

or controlling relations. Jo and Kim (2004), for example, discuss the Korean concept

of yon in communication: “Yon is related to the belief that relationships are formed,

maintained, and terminated by uncontrollable external forces, not by an individual’s

conscious efforts” (p. 294). As Miyahara (2006) pointed out, the English-language lit-

eratures use words such as “create,” “build,” “manage,” or “end” when speaking about

relations with others. From the perspective of “relational being,” such vocabulary may

not only appear alien but redundant: How can one “create” what already exists?

The idea of “relational being” goes to the core of OPR scholarship predicated on

the assumption of the separate, autonomous individual and corollary assumed need

to study individual agency or attributes to “build relationships.” The assumption of

“relational being” represents a paradigm shift from “building” to “being” in relation-

ships. This altered perspective raises questions about the role of micro-, meso-, and

macrolevel attributes and agency in communication based on the presumption of

pre-existing relational structures, rather than created ones. For OPR research, if one

holds the assumption of “relational being,” focus shifts from creating relationships

to conceptualizing one’s sense of being within the constellation of relations. Because

of relational mutuality, relational being is not a static feature but dynamic interplay of

influences. Advancing theory would mean identifying an array of relational strategies,

positive as well as negative, for navigating the relational dynamics while preserving the

integrity of the relational constellation.

Theoretical and research implications

This analysis of assumptions about “relationships” found in OPR scholarship has the-

oretical and research implications for public relations, as well as broader implications

for communication areas in which “relationships” are pivotal. Specifically for OPR,

the analysis extends Heath’s (2013) vision of the need to explore assumptions of “re-

lationships.” He questioned the idea of singled “OPR,” suggesting multiple public

and organizational relations, including the possibility of “OPsRs” and “OsSsRs.” The

present analysis illustrates how hidden cultural assumptions can constrict as well as

expand conceptual boundaries of relations.

Second, the analysis highlights the need to expand the typology of relations.

Assumptions of building and ending relationships may have accentuated a focus on

the positive (i.e., trust, mutuality, satisfaction) in OPR. However, if relationships are

not an individual prerogative but rather a given social condition, then research needs

to expand to identifying the range of relations, including negative ones. More work is

needed on deeply connected, yet adversarial public relations. Hung (2005) provides

an example in her continuum that spans from exploitive relations to communal

relations.

202 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

Third, there is a need to explore a wider range of relational strategies. The accent

on the positive extends to strategies. OPR literature suggests finding mutual interests

or cultivating trust as prerequisites for building relationships. However, such assump-

tions may be rooted in the transactional or exchange view of relationships. Asian

scholars suggest an inverse relational strategy that begins by creating bonds and using

reciprocity to cultivate trust (Yau, Lee, Chow, Sin, & Tse, 2000). The analysis also

exposed a gap in relational strategies for dealing with long-term negative relations

as well as rigid complex relational structures. Current OPR research appears limited

to ending negative relations or trying to alter the larger relational structure (i.e.,

“change the system”). The analysis also exposed a lingering gap in the develop-

ment of non-message-based relational strategies such as Chung’s (2011) chi-based

(energy-flow) strategies or Sriramesh’s (1992) personal influence model.

These insights about differing views of “relationships” and lessons drawn from

the OPR analysis have implications beyond public relations and extend to commu-

nication studies. First, as the different heritages illustrate, the concept of “relation-

ship” is infinitely complex and part of that complexity appears culturally mediated.

OPR struggled over definitions even within the confines of the cultural boundaries

of U.S.-based scholars (Broom et al., 1997). The realization that even basic concepts

contain cultural assumptions suggests that finding conceptual and theoretical con-

vergence across cultural boundaries may grow more challenging as communication

research globalizes.

Second, the assumption of an autonomous individual separate from other indi-

viduals and society (human and society) appears to be a uniquely U.S. view. This

distinctive premise immediately raises questions about the universality of theories

that emanate from this view. Different foundational premises would suggest different

theoretical constructs. Questions of applicability of Western theory to non-Western

societies is neither new (Kim, 2002), nor are culturally informed or culture-centric

perspectives. The different intellectual heritages, many of which existed long before

the rise of contemporary communication study, are rich in relational insights,

relations-based models and theoretical constructs. This analysis underscores Miike’s

(2006) call for moving beyond learning about to learning from other cultural

perspectives.

Third, different relational premises suggest different views of communication

goals and processes. For the autonomous individual, who is inherently separate,

communication is an instrumental process that relies on the individual’s attributes

and agency to create, build, and manage relations. Messaging remains so central to

the idea of “communication-as-transmission,” because the individual is autonomous,

that it is perhaps challenging to envision communication study without considering

message content or delivery even in the relational process. Yet, from the perspective

of the human in society and human-society, relations appear to define communi-

cation. The blurring of communication relations, first noted in assumptions in the

European literature, extends the observations of intercultural scholars about the

primacy of relations to suggest a distinctive view of “communication-as-relations.”

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 203

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

Relations-based understandings of “communication,” such as Chen’s (2001) harmony

model, would warrant greater exploration.

Fourth, as the OPR analysis illustrates, explicating these relational insights

requires moving beyond the IND/COL model. Although IND/COL is often described

as a continuum, it is often used to contrast rather than explore relational phenomena.

As such, it becomes a blunt analytical tool that misses the nuanced graduations about

“relationships” and their implications for communication. The model may also reveal

why researchers are stuck at the “data collection level” (Wang, 2011); researchers

may be limited to asking the same questions and documenting only variations in the

answers. While IND/COL may be losing its usefulness, “relationalism,”—which is

informed by scholars globally—remains a largely untapped tool for exploring the

conceptual space between the autonomous individual and the generalized collective.

Finally, this exploration of assumptions about “relationships” in public relations

suggests the possibility that other areas of communication studies may benefit from a

similar self-reflection. For instance, what assumptions might be hidden in theoretical

constructs of employee “relations” in organizational communication, or press-public

“relations” in media studies, or online “relations” in digital media scholarship? Alter-

ing research premises may also suggest new research agendas. For example, what

might the premise of holistic relations suggest for “relationship” cycles? What would

the assumption of relational spheres mean for message strategies? How might conflict

be explained if one assumes the entities are and will remain connected? What if, rather

than autonomy, one assumes inseparability? Or, how might the absence of agency and

the assumption of “relational being” shape understandings of interpersonal commu-

nication? By assuming different premises, researchers can ask the questions needed

to advance to a theoretical level.

Conclusion

This study has sought to explicate buried cultural assumptions associated with the

basic concept of “relationship” in public relations theory to illustrate how assumptions

at the basic level can reverberate to the theoretical level. Cultural assumptions may not

determine the direction of research, but they can inadvertently focus attention on cer-

tain aspects and create gaps and blind spots. While exposing the cultural assumptions

of “relationships” may be an imperative, doing so may not be easy. Because of the U.S.

dominance in laying a foundation across the breadth contemporary communication

studies, scholars may find themselves encased in a theoretical cocoon of reinforcing

assumptions about relationships. Yet persistence in explicating assumptions may have

a cascading effect on expanding directions of inquiry.

U.S.-based scholars are not the only ones vulnerable to buried cultural assump-

tions about relationships. The focus on relations resonates strongly with Confucius

philosophy (Huang, 2003; Yum, 2007). In scholarship by Asian-based scholars, one

finds subtle assumptions of contextual dynamics. Huang’s (2001) OPR scale that intro-

duced the dimension of “face” is a ready example. The concept of face is inherently a

204 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

relational phenomenon in that it implies a relational other who sees the face. Similar

to their U.S. counterparts, Asian scholars may need to be particularly alert to cul-

tural assumptions about “relationships.” Asian scholars who can articulate relational

assumptions and translate their conceptual application to other cultural contexts may

extend their global reach and value in communication studies.

In looking ahead, it may be time to explore other basic concepts and assumptions

in communication studies tied to the autonomous individual. This includes assump-

tions of the Self as inherently separate and even oppositional to the Other/s, the rel-

ative weight of individual agency and attributes, or the centrality of power, messages,

and media. As this study illustrates, the shadow cast by the autonomous individual

may obscure other perspectives, and with those perspectives, other vantage points for

explaining not just “relationships” but perhaps “communication” as well.

As Calhoun (2011) recently observed, “much of the [communication] field’s

future lies in research in and on the rest of the World—and in building international

connections” (pp. 1492–1493). In this era of globalization and shared scholarship

from different intellectual heritages, there is a need for greater awareness of cul-

tural assumptions by all scholars. The most basic concepts may be the ones most

vulnerable to cultural assumptions, yet these are the ones that warrant the most

attention and scrutiny because of their potential impact. Interrogating the cultural

assumptions associated with such basic concepts can help illuminate blind spots, and

more importantly opens up vistas of communication research that will thrive on the

diversity of intellectual heritages.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the journal editors and anonymous reviewers as well as Maureen

Taylor, Damion Waymer, and Bonita Neff for their helpful comments.

References

Asante, M. (1998). Afrocentric idea revised. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Ayish, M. I. (2003). Beyond Western-oriented communication theories: A normative

Arab-Islamic perspective. The Public, 10, 79–92. doi:10.4135/9781452243542.

Baxter, L. A. (2004). A tale of two voices: Relational dialectics theory. Journal of Family

Communication, 4(3&4), 181–192. doi:10.1080/15267431.2004.9670130.

Bellah, R. N. (1987). Habits of the heart. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bentele, G., & Nothhaft, H. (2010). Strategic communication and public sphere from a

European perspective. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 4, 93–116.

doi:10.1080/15531181003701954.

Botan, C., & Taylor, M. (2004). Public relations: State of the field. Journal of Communication,

54, 645–661. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02649.x.

Brewer, M. B., & Chen, Y. R. (2007). Where (who) are collectives in collectivism? Toward

conceptual clarification of individualism and collectivism. Psychological Review, 114,

133–151. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.114.1.133.

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 205

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

Broom, G. M., Casey, S., & Ritchey, J. (1997). Toward a concept and theory of

organization-public relationships. Journal of Public Relations Research, 9, 83–98.

doi:10.1207/s1532754xjprr0902_01.

Brown, K. A., & White, C. L. (2011). Organization-public relationships and crisis response

strategies: Impact on attribution of responsibility. Journal of Public Relations Research, 23,

75–92. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2010.504792.

Bruning, S. D., & Ledingham, J. A. (1999). Relationships between organizations and publics:

Development of a multi-dimensional organization-public relationship scale. Public

Relations Review, 25, 157–170. doi:10.1016/S0363-8111(99)80160-X.

Bruning, S. D., & Ledingham, J. A. (2000). Perceptions of relationships and evaluations of

satisfaction: An exploration of interaction. Public Relations Review, 26, 85–95.

doi:10.1016/S0363-8111(00)00032-1.

Calhoun, C. (2011). Communication as a social science (and more). International Journal of

Communication, 5, 1479–1496.

Carey, J. (1989). Communication as culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Castells, M. (2012). Networks of outrage and hope. New York, NY: Polity.

Chang, H. C. (2007). Interface between Chinese relational domains and language issues. In

S. J. Kulich & M. H. Prosser (Eds.), Intercultural perspectives on Chinese communication

(pp. 104–128). Shanghai, China: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

Chang, H. C., & Holt, G. R. (1991). More than relationship: Chinese interaction and the

principle of kuan-hsi. Communication Quarterly, 39, 251–271.

doi:10.1080/01463379109369802.

Chen, G.-M. (2001). A harmony theory of Chinese communication. In V. Milhouse,

M. Asante & P. Nwosu (Eds.), Transcultural realities (pp. 55–70). Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Chia, J. (2006). Measuring the immeasurable. Prism Online PR Journal, 4, 1–16.

Chiao, C. (1989). Chinese strategic behavior: Some general principles. In R. Bolton (Ed.), The

content of culture: Constants and variants, studies in honor of John M. Roberts

(pp. 525–537). New Haven, CT: HRAF.

Chung, J. (2011). Chi-based strategies for public relations in a globalizing world. In

N. Bardhan & C. K. Weaver (Eds.), Public relations in global contexts (pp. 226–249). New

York, NY: Routledge.

Condon, J. C., & Yousef, F. (1975). An introduction to intercultural communication.

Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill.

Dissanayake, W. (2009). The desire to excavate Asian theories of communication: One strand

of the history. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 4, 7–27.

doi:10.1080/17447140802651629.

Earley, C. P., & Gibson, C. B. (1998). Taking stock in our progress on individualism-

collectivism: 100 years of solidarity and community. Journal of Management, 24,

265–304. doi:10.1016/s0149-2063(99)80063-4.

Emirbayer, M. (1997). Manifesto for a relational sociology. American Journal of Sociology,

103, 281–317. doi:10.1086/231209.

Fang, T., & Faure, G. O. (2011). Chinese communication characteristics: A yin yang

perspective. International Journal of Intercultural Relations., 35, 320–333.

doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.06.005.

Fei, X. (1941/1992). From the soil. Berkeley: University of California Press.

206 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

Ferguson, M. A. (1984). Building theory in public relations: Interorganizational relationships.

Paper presented to the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass

Communication, Gainesville, FL.

Fitzpatrick, K. R. (2007). Advancing the new public diplomacy: A public relations

perspective. Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 2, 187–211. doi:10.1163/187119007X240497.

Ganesh, S., & Zoller, H. M. (2012). Dialogue, activism, and democratic social change.

Communication Theory, 22, 66–91. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2011.01396.x.

Grunig, J. E. (1993). Image and substance: From symbolic to behavioral relationships. Public

Relations Review, 19, 121–139. doi:10.036381119390003U.

Grunig, J. E. (2006). Furnishing the edifice: Ongoing research on public relations as a

strategic management function. Journal of Public Relations Research, 18, 151–176.

doi:10.1207/s1532754xjprr1802_5.

Grunig, L., Grunig, J., & Ehling, W. (1992). What is an effective organization?. In J. E. Grunig,

D. M. Dozier, W. P. Ehling, L. A. Grunig, F. C. Repper & J. White (Eds.), Excellence in

public relations and communication management (pp. 65–90). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

Gunaratne, S. A. (2010). De-Westernizing communication/social science research:

Opportunities and limitations. Media, Culture & Society, 32, 473–500.

doi:10.1177/01634433709351159.

Habermas, J. (1962/1991). The structural transformation of the public sphere. Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Heath, R. L. (2013). The journey to understand and champion OPR takes many roads, some

not yet well traveled. Public Relations Review, 39(5), 426–431. doi:10.1016/j.

pubrev.2013.05.002.

Hecht, M. L., Jackson, R. L., & Ribeau, S. A. (2003). African American communication. New

York, NY: Routledge.

Ho, D. Y. (1998). Interpersonal relationships and relationship dominance: An analysis based

on methodological relationism. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 1–16.

doi:10.1111/1467-839X.00002.

Ho, D. Y., Peng, S.-Q., Lai, A. C., & Chan, S.-F. (2001). Indigenization and beyond:

Methodological relationalism in the study of personality across cultural traditions.

Journal of Personality, 69, 925–953. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.696170.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Holtzhausen, D. R., & Voto, R. (2002). Resistance from the margins: The postmodern public

relations practitioner as organizational activist. Journal of Public Relations Research, 14,

57–84. doi:10.1207/S1532754XJPRR1401_3.

Hon, L., & Grunig, J. E. (1999). Guidelines for measuring relationships in public relations.

Gainesville, FL: The Institute for Public Relations.

Huang, Y.-H. (2001). OPRA: A cross-cultural, multiple-item scale for measuring

organization-public relationships. Journal of Public Relations Research, 13, 61–90.

doi:10.1207/S1532754XJPRR1301_4.

Huang, Y.-H. (2003). A Chinese perspective of intercultural organization-public relationship.

Intercultural Communication Studies, 12, 25–276.

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 207

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

Huang, Y.-H., & Zhang, Y. (2012). Revisiting organization-public relations over the past

decade: Theories, measures, methodologies and challenges. Public Relations Review, 39,

85–87. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.10.001.

Hung, F. C. (2004). Cultural influence on relationship cultivation strategies: Multinational

companies in China. Journal of Communication Management, 8, 264–281.

doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.10.001.

Hung, F. C. (2005). Exploring types of organization–public relationships and their

implications for relationship management in public relations. Journal of Public Relations

Research, 17, 393–426. doi:10.1207/s1532754xjprr1704_4.

Hung, F. C. (2006). Toward the theory of relationship management in public relations: How

to cultivate quality in relationships?. In E. L. Toth (Ed.), The future of excellence in public

relations and communication management (pp. 443–476). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Hung, F. C., & Chen, Y.-R. R. (2009). Types and dimensions of organization-public

relationships in Greater China. Public Relations Review, 35, 181–186.

doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.04.001.

Hwang, K.-K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of

Sociology, 92, 944–974. doi:10.1086/228588.

Hwang, K.-K. (2000). Chinese relationalism: Theoretical construction and methodological

considerations. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30, 155–178.

doi:10.1111/1468-5914.00124.

Ishii, S. (2006). Complementing contemporary intercultural communication research with

East Asian sociocultural perspectives and practices. China Media Research, 2, 13–20.

Jahansoozi, J. (2006). Relationships, transparency, and evaluation: The implications for public

relations. In J. L’Etang & M. Piezcka (Eds.), Public relations: Critical debates and

contemporary practice (pp. 61–91). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Jahansoozi, J. (2007). Organization–public relationships: An exploration of the Sundre

Petroleum Operators Group. Public Relations Review, 33, 398–406.

doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2007.08.006.

Jo, S., Hon, L. C., & Brunner, B. R. (2004). Organisation-public relationships: Measurement

validation in a university setting. Journal of Communication Management, 9, 14–27.

Jo, S., & Kim, Y. (2004). Media or personal relations? Exploring media relations dimensions

in South Korea. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 81, 292–306.

doi:10.1177/10776990048100205.

Kashima, E. S., & Hardie, E. A. (2000). The development and validation of the relational,

individual, and collective self-aspects (RIC) scale. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3,

19–48. doi:10.1111/1467-839x.00053.

Kent, M. L., & Taylor, M. (2002). Toward a dialogic theory of public relations. Public Relations

Review, 28, 21–37. doi:10.1016/20363-8111(02)00108-x.

Ki, E.-J., & Shin, J.-H. (2006). Status of organization-public research from an analysis of

published articles, 1985–2004. Public Relations Review, 32, 194–195.

doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2006.02.019.

Kikuchi, M., & Coleman, C. (2012). Explicating and measuring social relationships in social

capital research. Communication Theory, 22, 187–203.

Kim, M.-S. (2002). Non-Western perspectives on human communication: Implications for

theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

208 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

Kohut, A., & Stokes, B. (2007). America against the world: How we are different and why we

are disliked. New York, NY: Times Books.

Korzenny, F., & Korzenny, B. A. (2005). Hispanic marketing: A cultural perspective. St. Louis,

MO: Elsevier.

Kreuzbauer, R., Lin, S., & Chiu, C.-Y. (2009). Relational versus group collectivism and

optimal distinctiveness in a consumption context. Advances in Consumer Research, 36,

742.

Krog, A. (2008). ‘ … if it means he gets his humanity back … ’: The worldview underpinning

the South African truth and reconciliation commission. Journal of Multicultural

Discourses, 3, 204–220. doi:10.1080/17447140802406891.

L’Etang, J. (2009). Public relations and diplomacy in a globalized world: An issue of public

communication. American Behavioral Scientist, 53, 607–626. doi:

10.1177/0002764209347633.

Ledingham, J. A. (2000). Guidelines to building and maintaining strong organization-public

relationships. Public Relations Quarterly, 45, 44–46. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.06.006.

Ledingham, J. A. (2006). Relationship management: A general theory of public relations. In

C. Botan & V. Hazelton (Eds.), Public relations theory II (pp. 465–483). Mahawah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ledingham, J. A., & Bruning, S. D. (1998). Relationship management in public relations:

Dimensions of an organization-public relationship. Public Relations Review, 24, 55–67.

doi:10.1016/s0363-8111(98)80020-9.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1994). A collective fear of the collective: Implications for

selves and theories of selves. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 568–579.

doi:10.1177/0146167294205013.

Meng, J. (2007, November). How far can we go in organization-public relationships research? A

descriptive content analysis of the status of the research trends in OPR research. Paper

presented at the 93rd annual convention of National Communication Association,

Chicago, IL.

Miike, Y. (2003). Beyond Eurocentrism in the intercultural field: Searching for an Asiacentric

paradigm. In W. J. Starosta & G.-M. Chen (Eds.), Ferment in the intercultural field:

Axiology/value/praxis (pp. 243–276). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Miike, Y. (2006). Non-Western theory in Western research? An Asiacentric agenda for Asian

communication studies. Review of Communication, 6, 4–31. doi:10.1080/15358

590600763243.

Miyahara, A. (2006). Toward theorizing Japanese interpersonal communication competence

from a non-Western perspective. American Communication Journal, 3, 1–16.

Monge, P. R. (1997). Communication theory for a globalizing world. In J. S. Trent (Ed.),

Communication: Views from the helm for the 21st century (pp. 3–7). Boston, MA: Allyn &

Bacon.

Muskat, B. (2014). Emotions in organization-public relations: Proposing a new determinant.

Public Relations Review. 40, 832–834. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.06.004.

Ni, L., & Wang, Q. (2011). Anxiety and uncertainty management in an intercultural setting:

The impact on organization–public relationships. Journal of Public Relations Research, 23,

269–301. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2011.582205.

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought:

Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108, 291–310.

doi:10.1037/0033-295x.108.2.291.

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 209

Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism R. S. Zaharna

Nwosu, P. O. (2009). Understanding Africans’ conceptualizations of intercultural

competence. In D. Deardorff (Ed.), The Sage handbook of intercultural competence

(pp. 158–178). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and

collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological

Bulletin, 128, 3–72. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3.

Pedersen, P. B. (1988). A handbook for development multicultural awareness. Alexandria, VA:

American Association for Counseling and Development.

Reddi, U. V. (1985). Communication theory: An Indian perspective. AMIC-Thammasat

University symposium on Mass Communication Theory: The Asian Perspective,

Bangkok, Thailand.

Ritzer, G., & Gindoff, P. (1992). Methodological relationism: Lessons for and from social

psychology. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55, 128–140. doi:10.2307/2786942.

Samovar, L., Porter, R., & Jain, N. (1981). Understanding intercultural communication.

Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Schramm, W. (1997). Beginnings of communication study in America. Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Beyond individualism–collectivism: New cultural dimensions of

values. In U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S.-C. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.),

Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications (pp. 85–119). Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shi-xu (2009). Reconstructing Eastern paradigms of discourse studies. Journal of

Multicultural Discourses, 4, 29–48. doi:10.1080/17447140802651637.

Sinha, D. (1998). Changing perspectives in social psychology in India: A journey towards

indigenization. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 17–31. doi:10.1111/1467-839x.

00003.

Sinha, J. B. P., Sinha, T. N., Verma, J., & Sinha, R. B. N. (2001). Collectivism coexisting with

individualism: An Indian scenario. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 4, 133–145.

doi:10.1111/j.1467-839x.2001.00081.x.

Sriramesh, K. (1992). Societal culture and public relations: Ethnographic evidence from

India. Public Relations Review, 18(2), 201–211. doi:10.1016/0363-8111(92)90010-v.

Sriramesh, K. (2012). Culture and public relations: Formulating the relationship and its

relevance to the practice. In K. Sriramesh & D. Verčič (Eds.), Culture and public relations:

Links and implications (pp. 9–24). London, England: Routledge.

Stewart, E. C., & Bennett, M. J. (1991). American cultural patterns: A cross-cultural

perspective. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Taras, V., Sarala, R., Muchinsky, P., Kemmelmeier, M., Singelis, T. M., Avsec, A., …

Probst, T. M. (2014). Opposite ends of the same stick? Multi-method test of the

dimensionality of individualism and collectivism. Journal Of Cross-Cultural Psychology,

45(2), 213–245. doi:10.1177/0022022113509132.

Theunissen, P. (2014). Co-creating corporate identity through dialogue: A pilot study. Public

Relations Review, 40(3), 612–614. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.02.026.

Triandis, H., Brislin, R., & Hui, C. (1988). Cross-cultural training across the

individualism-collectivism divide. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 12,

269–289. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(88)90019-3.

210 Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association

R. S. Zaharna Beyond the Individualism–Collectivism Divide to Relationalism

Triandis, H. C., Bontempo, R., Villareal, M., Asai, M., & Lucca, N. (1988). Individualism and

collectivism: Cross-cultural perspectives in self-ingroup relationships. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 323–338. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.2.323.

Uysal, N., & Yang, A. (2013). The power of activist networks in the mass self-communication

era: A triangulation study of the impact of WikiLeaks on the stock value of Bank of

America. Public Relations Review, 39, 459–469. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.09.007.

Valentini, C., & Nesti, G. (2010). Public communication in the European Union: History,

perspectives and challenges. Newcastle Upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars

Publishing.

Vanc, A. (2010). The relationship management process of public diplomacy: U.S. public

diplomacy in Romania. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Tennessee,

Knoxville.

Verčič, D., & Van Ruler, B. (2004). Overview of public relations and communication

management in Europe. In B. Van Ruler & D. Verčič (Eds.), Public relations and

communication management in Europe (pp. 1–17). Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

Verčič, D., Van Ruler, B., Butschi, G., & Flodin, B. (2001). On the definition of public

relations: A European view. Public Relations Review, 27(4), 373–387.

doi:10.1016/s0363-8111(01)00095-9.

Voronov, M., & Singer, J. A. (2002). The myth of individualism-collectivism: A critical

review. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142, 461–480. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603912.

Wang, G. (2011). Paradigm shift and the centrality of communication discipline.

International Journal of Communication, 5, 1458–1466.

Willis, P. (2011). Engaging communities : Ostrom’s economic commons, social capital and

public relations. Public Relations Review, 38, 116–122. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.08.016.

Wood, J. T. (1995). Relational communication. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Yang, A., Klyueva, A., & Taylor, M. (2012). Beyond a dyadic approach to public diplomacy:

Understanding relationships in multipolar world. Public Relations Review, 38(5),

652–664. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.07.005.

Yau, O. H., Lee, J. S., Chow, R. P., Sin, L. Y., & Tse, A. C. (2000). Relationship marketing the

Chinese way. Business Horizons, 43(1), 16–24. doi:10.1016/s0007-6813(00)87383-8.

Yum, J. O. (2007). Confucianism and communication: Jen, li, and ubuntu. China Media

Research, 3, 15–22.

Communication Theory 26 (2016) 190–211 © 2015 International Communication Association 211

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)