Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Axelsson 2012

Axelsson 2012

Uploaded by

happyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- CreativeWriting12 Q1 Module-1Document28 pagesCreativeWriting12 Q1 Module-1Burning Rose89% (140)

- Project Report in JSWDocument44 pagesProject Report in JSWmohd arif khan73% (15)

- O&S April 2009Document134 pagesO&S April 2009Didi Menendez100% (20)

- HHS Public AccessDocument17 pagesHHS Public AccessChika SabaNo ratings yet

- Grothe Et Al., 2013Document13 pagesGrothe Et Al., 2013mackenzie.lacey28No ratings yet

- 2017 Juliaom - PSC PDFDocument10 pages2017 Juliaom - PSC PDFIka Nur AnnisaNo ratings yet

- Dying Means Suffocating, Perceptions of People Living With COPD Facing End of LifeDocument8 pagesDying Means Suffocating, Perceptions of People Living With COPD Facing End of LifetourfrikiNo ratings yet

- Emotional Distress in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure: ReviewDocument11 pagesEmotional Distress in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure: ReviewCândida MineiroNo ratings yet

- Eilertsen BJRK Kirkevold 2010Document11 pagesEilertsen BJRK Kirkevold 2010Anh HuyNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Costs of Care For Patients With Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument11 pagesDeterminants of Costs of Care For Patients With Alzheimer's DiseaseBenny TjanNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 14 1281878Document10 pagesFpsyg 14 1281878dr.joneidiNo ratings yet

- Lived Through Past Experienced Present Anticipated Future Understanding Existential Loss in The Context of Life Limiting IllnessDocument16 pagesLived Through Past Experienced Present Anticipated Future Understanding Existential Loss in The Context of Life Limiting Illnessfrancheskaam27No ratings yet

- The Effect of Depression On The Quality 0f Life of Patient With Cervical Cancer at Dr. Moewardi Hospital in SurakartaDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Depression On The Quality 0f Life of Patient With Cervical Cancer at Dr. Moewardi Hospital in SurakartaEndahNo ratings yet

- Applied Nursing Research: Mi-Kyoung Cho, PHD, Apn, Gisoo Shin, PHD, RNDocument7 pagesApplied Nursing Research: Mi-Kyoung Cho, PHD, Apn, Gisoo Shin, PHD, RNJoecoNo ratings yet

- The Bodily Presence of Significant Others Intensive Care Patients Experiences in A Situation of Critical IllnessDocument9 pagesThe Bodily Presence of Significant Others Intensive Care Patients Experiences in A Situation of Critical IllnessSara Daniela Benalcazar JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Risks Associated With Incident and Prevalent Periodontal DiseaseDocument8 pagesCardiovascular Risks Associated With Incident and Prevalent Periodontal DiseaseAlyaefkageNo ratings yet

- 12 Ustundag Orignial 9 3Document8 pages12 Ustundag Orignial 9 3Sanjivi GovekarNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Effective Pain Management in Sickle Cell DiseaseDocument4 pagesBarriers To Effective Pain Management in Sickle Cell DiseaseDr. Smiley JadonandanNo ratings yet

- Pre-Dialysis Patients ' Perceived Autonomy, Self-Esteem and Labor Participation: Associations With Illness Perceptions and Treatment Perceptions. A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument10 pagesPre-Dialysis Patients ' Perceived Autonomy, Self-Esteem and Labor Participation: Associations With Illness Perceptions and Treatment Perceptions. A Cross-Sectional Studyandrada14No ratings yet

- Land Olt 2011Document13 pagesLand Olt 2011Windy TiandiniNo ratings yet

- A Review of EOLDocument33 pagesA Review of EOLinderaaputraaNo ratings yet

- Critical Reviews in Oncology / HematologyDocument18 pagesCritical Reviews in Oncology / HematologyLiterasi MedsosNo ratings yet

- Samson Et Al - Psychosocial Adaptation To Chronic IllnessDocument13 pagesSamson Et Al - Psychosocial Adaptation To Chronic IllnessRaquel PintoNo ratings yet

- Ten Minutes To Midnight: A Narrative Inquiry of People Living With Dying With Advanced Copd and Their Family MembersDocument11 pagesTen Minutes To Midnight: A Narrative Inquiry of People Living With Dying With Advanced Copd and Their Family MembersCeline WongNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Exercise Standards On The Quality of Life To People With Chronic DiseaseDocument18 pagesThe Effects of Exercise Standards On The Quality of Life To People With Chronic DiseaseMario LanzaNo ratings yet

- Mattsson 2011Document12 pagesMattsson 2011oh yuniNo ratings yet

- Concerns of Patients On Dialysis A Research Study PDFDocument15 pagesConcerns of Patients On Dialysis A Research Study PDFProdi S1- 1BNo ratings yet

- Depressive Symptoms and Dietary Adherence in Patients With End-Stage Renal DiseaseDocument10 pagesDepressive Symptoms and Dietary Adherence in Patients With End-Stage Renal Diseasebasti_aka_slimNo ratings yet

- Nurse and Social Worker Palliative Telecare Team and Quality of Life in Patients With COPD, Heart Failure, or Interstitial Lung DiseaseDocument12 pagesNurse and Social Worker Palliative Telecare Team and Quality of Life in Patients With COPD, Heart Failure, or Interstitial Lung DiseasejunhamanoNo ratings yet

- Personality Change Associated With Chronic Diseases: Pooled Analysis of Four Prospective Cohort StudiesDocument13 pagesPersonality Change Associated With Chronic Diseases: Pooled Analysis of Four Prospective Cohort StudiesDebora BergerNo ratings yet

- End of LifeDocument3 pagesEnd of LifeSiti Fatimahtusz07No ratings yet

- Multiple Sclerosis Lancet 2018Document15 pagesMultiple Sclerosis Lancet 2018Sarah Miryam CoffanoNo ratings yet

- Experiences of Psychological FlowerDocument8 pagesExperiences of Psychological Flowerlsj19950128No ratings yet

- Research Article: Turkish Journal of Psychiatry 2021 32 (4) :246-252Document8 pagesResearch Article: Turkish Journal of Psychiatry 2021 32 (4) :246-252Celine WongNo ratings yet

- Background of The Study and SOP - Quali Research2-1Document3 pagesBackground of The Study and SOP - Quali Research2-1Maricris I. AbuanNo ratings yet

- Ho 2013Document6 pagesHo 2013Vera El Sammah SiagianNo ratings yet

- Mia Pruefer - Health Literacy and Elhers-Danlos Syndrome Hypermobility TypeDocument14 pagesMia Pruefer - Health Literacy and Elhers-Danlos Syndrome Hypermobility TypeMia PrueferNo ratings yet

- Living With Advanced Parkinson's Disease: A Constant Struggle With UnpredictabilityDocument10 pagesLiving With Advanced Parkinson's Disease: A Constant Struggle With UnpredictabilityLorenaNo ratings yet

- ContentServer AspDocument8 pagesContentServer Aspstephanie eduarteNo ratings yet

- Birkefeld (2022)Document14 pagesBirkefeld (2022)Nerea AlvarezNo ratings yet

- 480 253 1057 1 10 20190424 PDFDocument8 pages480 253 1057 1 10 20190424 PDFdwiajaNo ratings yet

- Mazujnms v2n2p29 enDocument7 pagesMazujnms v2n2p29 enDoc RuthNo ratings yet

- Pain Neuroscience Education in Older Adults With Chronic Back and or Lower Extremity PainDocument12 pagesPain Neuroscience Education in Older Adults With Chronic Back and or Lower Extremity PainAriadna BarretoNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument4 pagesContent ServerEkaSaktiWahyuningtyasNo ratings yet

- End-Of-Life Care in The Icu: Supporting Nurses To Provide High-Quality CareDocument5 pagesEnd-Of-Life Care in The Icu: Supporting Nurses To Provide High-Quality CareSERGIO ANDRES CESPEDES GUERRERONo ratings yet

- Life Review Therapy For Older Adults With Moderate Depressive Symptomatology: A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled TrialDocument12 pagesLife Review Therapy For Older Adults With Moderate Depressive Symptomatology: A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled TrialAstridNo ratings yet

- PIIS1976131710600059Document11 pagesPIIS1976131710600059Marina UlfaNo ratings yet

- Losely Geriatric Paper 325Document7 pagesLosely Geriatric Paper 325api-532850773No ratings yet

- The Perception of Life and Death in Patients With End-Of-Life Stage Cancer: A Systematic Review of Qualitative ResearchDocument13 pagesThe Perception of Life and Death in Patients With End-Of-Life Stage Cancer: A Systematic Review of Qualitative ResearchPedro TavaresNo ratings yet

- Neurobiology of Resilience in Depression Immune and Vascular InsightDocument78 pagesNeurobiology of Resilience in Depression Immune and Vascular InsightMaria BelénNo ratings yet

- CHF 5Document8 pagesCHF 5Prameswari ZahidaNo ratings yet

- Tan Burden Distress Qol Informal Caregivers Lung CancerDocument11 pagesTan Burden Distress Qol Informal Caregivers Lung CancerRubí Corona TápiaNo ratings yet

- UncertaintyDocument16 pagesUncertaintymaya permata sariNo ratings yet

- Kaptein-Common-Sense Model-OsteoarthritisDocument9 pagesKaptein-Common-Sense Model-OsteoarthritisZyania MelchyNo ratings yet

- Shao2020 PDFDocument7 pagesShao2020 PDFAndrea ZambranoNo ratings yet

- EUTHADocument10 pagesEUTHAJena WoodsNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CKDDocument8 pagesJurnal CKDRatna Dewi CahyaniNo ratings yet

- Clarifying Dementia Risk Factors: Treading in Murky Waters: CommentaryDocument3 pagesClarifying Dementia Risk Factors: Treading in Murky Waters: CommentaryVazia Rahma HandikaNo ratings yet

- Chochinov - Dignity Therapy - A Feasibility Study of EldersDocument13 pagesChochinov - Dignity Therapy - A Feasibility Study of Eldersjuarezcastellar268No ratings yet

- Acarturk Et Al 2016Document11 pagesAcarturk Et Al 2016290971No ratings yet

- Kart Tune N 2010Document10 pagesKart Tune N 2010AndreiaNo ratings yet

- Orofacial Pain: From Basic Science to Clinical Management, Second EditionFrom EverandOrofacial Pain: From Basic Science to Clinical Management, Second EditionNo ratings yet

- Experiences of Adolescents Living with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus whilst Negotiating with the Society: Submitted as part of the MSc degree in diabetes University of Surrey, Roehampton, 2003From EverandExperiences of Adolescents Living with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus whilst Negotiating with the Society: Submitted as part of the MSc degree in diabetes University of Surrey, Roehampton, 2003No ratings yet

- RETREAT Framework Et Al. 2018Document12 pagesRETREAT Framework Et Al. 2018happyNo ratings yet

- Hudson 2005Document13 pagesHudson 2005happyNo ratings yet

- Hendrix 2011Document21 pagesHendrix 2011happyNo ratings yet

- ChecklistDocument2 pagesChecklisthappyNo ratings yet

- Hendrix 2006Document6 pagesHendrix 2006happyNo ratings yet

- He Demand 2011Document9 pagesHe Demand 2011happyNo ratings yet

- Davison Et Al 2006Document5 pagesDavison Et Al 2006happyNo ratings yet

- Leadership Joyce 2016Document7 pagesLeadership Joyce 2016happyNo ratings yet

- Big DataDocument20 pagesBig DataBhavnita NareshNo ratings yet

- Essential Kitchen Bathroom Bedroom - September 2014 UKDocument164 pagesEssential Kitchen Bathroom Bedroom - September 2014 UKfishermantoys100% (1)

- Logic Gate Investigatory PDFDocument12 pagesLogic Gate Investigatory PDFGaurang MathurNo ratings yet

- UNICEF's Work in Public Finance For ChildrenDocument2 pagesUNICEF's Work in Public Finance For ChildrenCr CryptoNo ratings yet

- Bibliografía RazaDocument3 pagesBibliografía RazaJorge Vallejo KazacosNo ratings yet

- Plural of NounsDocument1 pagePlural of NounsStrafalogea Serban100% (2)

- 365DayPan DailyEnglishLessonPlanUPDATED2022Document379 pages365DayPan DailyEnglishLessonPlanUPDATED2022KATIUSCA EVELYN GONZALES RIVERANo ratings yet

- Workshop Living in The Czech Republic: WWW - Expatlegal.czDocument22 pagesWorkshop Living in The Czech Republic: WWW - Expatlegal.czImran ShaNo ratings yet

- Brand Engagement With Brand ExpressionDocument27 pagesBrand Engagement With Brand ExpressionArun KCNo ratings yet

- Le Conditionnel Présent: The Conditional PresentDocument8 pagesLe Conditionnel Présent: The Conditional PresentDeepika DevarajNo ratings yet

- Remunerasi RSDocument39 pagesRemunerasi RSalfanNo ratings yet

- Gate Induced Drain Leakage For Ultra Thin MOSFET Devices Using SilvacoDocument2 pagesGate Induced Drain Leakage For Ultra Thin MOSFET Devices Using Silvacosiddhant gangwalNo ratings yet

- NOTICEDocument126 pagesNOTICEowsaf2No ratings yet

- Count and Non-Count Nous (Plural Form of Nous)Document9 pagesCount and Non-Count Nous (Plural Form of Nous)Kathe TafurNo ratings yet

- 11.29.12 Post Standard, The Word Is Out New Law Protects Overdose Victims and HelpersDocument2 pages11.29.12 Post Standard, The Word Is Out New Law Protects Overdose Victims and Helperswebmaster@drugpolicy.orgNo ratings yet

- QTS AplicationDocument8 pagesQTS Aplicationandreuta23No ratings yet

- Reza Sitinjak CJR COLSDocument5 pagesReza Sitinjak CJR COLSReza Enjelika SitinjakNo ratings yet

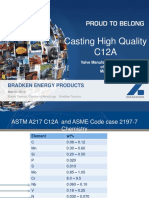

- Casting High Quality C12A: Bradken Energy ProductsDocument37 pagesCasting High Quality C12A: Bradken Energy Productsdelta lab sangliNo ratings yet

- World War IDocument7 pagesWorld War IhzbetulkunNo ratings yet

- English Test-SMA-Kelas-XII-Semester-IDocument4 pagesEnglish Test-SMA-Kelas-XII-Semester-IAru HernalantoNo ratings yet

- Personality and Work Behaviour Exploring The 1996 PDFDocument18 pagesPersonality and Work Behaviour Exploring The 1996 PDFAtif BasaniNo ratings yet

- EstimationDocument106 pagesEstimationasdasdas asdasdasdsadsasddssa0% (1)

- Final For ReviewDocument39 pagesFinal For ReviewMichay CloradoNo ratings yet

- Catholic Ghost Stories of Western PennsylvaniaDocument5 pagesCatholic Ghost Stories of Western PennsylvaniaeclarexeNo ratings yet

- Marketing Research ProcessDocument3 pagesMarketing Research Processadnan saifNo ratings yet

- Novo Nordisk AR 2011 enDocument116 pagesNovo Nordisk AR 2011 enINVESTORNEWNo ratings yet

- Stanford CS193p Developing Applications For iOS Fall 2013-14Document66 pagesStanford CS193p Developing Applications For iOS Fall 2013-14AbstractSoft100% (1)

Axelsson 2012

Axelsson 2012

Uploaded by

happyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Axelsson 2012

Axelsson 2012

Uploaded by

happyCopyright:

Available Formats

E N D O F LI F E A N D P A L L I A T I V E C A R E

Thoughts on death and dying when living with haemodialysis

approaching end of life

Lena Axelsson, Ingrid Randers, Carina Lundh Hagelin, Stefan H Jacobson and Birgitta Klang

Aims and objectives. To describe inner thoughts and feelings relating to death and dying when living with haemodialysis

approaching end of life.

Background. Patients who undergo maintenance haemodialysis suffer a significant symptom burden and an impaired quality of

life. The high mortality rate in these patients indicates that about one-fourth of them are in their last year of life, suggesting the

presence of death and dying in the haemodialysis unit.

Design. A qualitative descriptive design was used.

Methods. A total of 31 qualitative interviews were conducted with eight patients (aged 66–87) over a period of 12 months.

Qualitative content analysis was used to analyse data.

Results. The analysis revealed 10 subthemes that were sorted into three main themes. Being aware that death may be near

comprises being reminded of death and dying by the deteriorating body, by the worsening conditions and deaths of fellow

patients, and by knowing haemodialysis treatment as a border to death. Adapting to approaching death comprises looking upon

death as natural, preparing to face death, hoping for a quick death and repressing thoughts of death and dying. Being alone with

existential thoughts comprises a wish to avoid burdening family, lack of communication with healthcare professionals and

reflections on haemodialysis withdrawal as an hypothetic option.

Conclusions. Living with haemodialysis approaching, the end of life involves significant and complex existential issues and

suffering, and patients are often alone with their existential thoughts.

Relevance to clinical practice. Nurses and other healthcare professionals in haemodialysis settings need to combine technical

and medical abilities with committed listening and communication skills and be open to talking about death and dying, with

sensitivity to individual and changeable needs.

Key words: death, dying, end of life, end-stage renal disease, haemodialysis, qualitative content analysis, qualitative interviews,

serial interviews

Accepted for publication: 26 February 2012

renal transplantation, is increasing worldwide (Eggers 2011).

Introduction

The number of patients with ESRD on maintenance hae-

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) (stage 5 chronic kidney modialysis treatment (MHD) is growing in western society.

disease), which requires treatment with lifelong dialysis or Annual mortality rates in these patients are about 20–25%

Authors: Lena Axelsson, RN, Doctoral Student, Sophiahemmet Institutet; Stefan H Jacobson, MD, Professor, Department of

University College and Division of Nursing, Department of Nephrology, Karolinska Institutet and Danderyd University

Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institutet; Hospital; Birgitta Klang, RNT, Associate Professor, Division of

Ingrid Randers, RNT, PhD, Senior Lecturer, Sophiahemmet Nursing, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society,

University College and Division of Nursing, Department of Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Karolinska Institutet; Correspondence: Lena Axelsson, Doctoral Student, Sophiahemmet

Carina Lundh Hagelin, RN, PhD, Senior Lecturer, Sophiahemmet University College, Box 5605, Stockholm 11486, Sweden.

University College and Department of Learning, Informatics, Telephone: +46 70 848 93 08.

Management and Ethics, Medical Management Center, Karolinska E-mail: lena.axelsson@shh.se

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04156.x 2149

L Axelsson et al.

(SNR 2010, USRD 2010), indicating that about one-fourth whole person care in their hovering between living in the

of patients on MHD are in their last year of life. This present and worrying about the future, that is facing death

enlightens the presence of death and dying in the haemo- (Axelsson et al. 2012).

dialysis unit. Existential issues have also been described in other studies

of patients’ experiences of MHD. It has been interpreted as a

continuous struggle to maintain hope of a normal life while

Background

dealing with an uncertain future, with questions of meaning

Earlier studies stress the impaired quality of life (Kimmel & and how much time there is left (Gregory et al. 1998). MHD,

Patel 2006, Davison & Jhangri 2010) and significant symp- as a deficient lifeline, has also shown to be a persistent

tom burden (Davison et al. 2006, Saini et al. 2006, Murtagh reminder of a limited lifetime (Hagren et al. 2001). The

et al. 2007) that patients undergoing MHD suffer because of changed life situation experienced by patients undergoing

uraemia and the effects of dialysis. Frequently described MHD, in the dimensions of time and space, has also been

symptoms are lack of energy, decreased appetite, nausea, described as an existential struggle (Hagren et al. 2005), and

pain, pruritus, shortness of breath, sleep disturbances, anx- patients on MHD have been found to fight for personal

iety, muscular cramp and dizziness (Weisbord et al. 2004, preservation while acknowledging the nearness of and

2005). Comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiac disease, awaiting a certain death (Calvin 2004).

cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease add In the dialysis unit, the nurse cares for patients who have

to the symptom burden and the complexity of the suffering several chronic progressive and life-threatening illnesses and

(Weisbord et al. 2003, 2005). Mortality rates are due largely they suffer from a high symptom burden. Furthermore, these

to comorbidities, with cardiovascular disease causing about severely ill patients maintain life by advanced medical

45% of deaths in patients on MHD (SNR 2010). The mean technology that also raises existential issues. The presence

age of patients undergoing MHD is rising (SNR 2010, USRD of death in the dialysis unit has come forth, and to better

2010), which further decreases life expectancy in this understand and improve care for severely ill patients treated

population. Withdrawal of dialysis treatment precedes about with MHD, we need more knowledge about their experiences

13% (SNR 2010) to 25% (Germain & Cohen 2008) of and increase our understanding of their thoughts and feelings

deaths in patients with MHD and results in an average relating to death and dying when they are approaching end of

remaining survival time of eight days (Cohen et al. 2000a,b). life.

Withholding or initiating withdrawal from dialysis (Cohen

et al. 2000a, Cohen & Germain 2005) has been the focus of

Methods

palliative care for patients with ESRD. However, the ageing

patient population with their complex symptoms and com-

Aim

orbidities has raised awareness of the need to integrate

palliative care approach earlier in nephrology care and for a The aim of this study was to describe inner thoughts and

longer time (Young 2009, Kurella Tamura & Cohen 2010, feelings relating to death and dying when living with

Harrison & Watson 2011). Implementation of the philoso- haemodialysis approaching end of life.

phy of palliative care in the haemodialysis unit, with active

care for the whole person, has also been put forward as many

Design

patients suffer from continuous deterioration (Madar et al.

2007). A qualitative descriptive design with an inductive approach

An earlier study (Axelsson et al. 2012) on the meanings of was used.

being severely ill living with MHD at the approach of end of

life elucidates complexities and intertwined meanings when

Participants and setting

the deteriorating body influences life more and more, and

patients are enduring a restricted and heavy life for the This study is part of an ongoing study intending to increase

possibility of living a bit longer. Being severely ill living with the understanding and knowledge of end-of-life issues in

MHD means facing progressive losses and threats, and severely ill patients living with MHD. In a first study

findings elucidate suffering in physical, psychosocial, emo- (Axelsson et al. 2012), the meanings of being severely ill

tional and existential dimensions. Findings showed the living with haemodialysis were described, while the present

importance of knowing the patients’ own understanding of study seeks for a deeper understanding of thoughts and

their illness and situation and underpin the importance of feelings relating to death and dying.

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

2150 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159

End of life and palliative care Thoughts on death and dying

Eight severely ill adults with ESRD, five men and three tell me your experiences of living with illness and haemod-

women, participated (previously described in Axelsson et al. ialysis’. Open and clarifying questions invited participants to

2012). They were selected with purposive sampling for talk about different dimensions and thereby their thoughts

variation in comorbidities, sex and family situation. The and feelings relating to death and dying. The first author

participants were recruited from four dialysis clinics, two in conducted all 31 interviews on days when the participant was

university hospitals and two smaller dialysis satellites in an free from dialysis. Most interviews (26) took place, according

urban area of Sweden. Participants were clinically assessed as to the participants’ wishes, in the participants’ homes, but

severely ill and therefore possibly in their last year of life, by five were conducted at a nursing home or on a hospital ward.

the nephrology physician and the registered dialysis nurse The interviews (33 hours in total) were audiotaped and

responsible for their dialysis treatments. For this study, we transcribed verbatim.

define this as approaching death. The assessment was based on

the presence of comorbidities, malnutrition and other com-

Data analysis

plications. Inclusion criteria were also to have been treated

with haemodialysis for at least three months, not to be listed Qualitative content analysis was applied when analysing the

for kidney transplantation, and to be able to read, write and data (Graneheim & Lundman 2004). The interview texts

speak Swedish. In addition to kidney disease, the participants were read several times to grasp the overall content.

had a multiplicity of comorbidities, including cardiac disease, ‘Meaning units’ (i.e. parts of sentences, sentences or para-

peripheral vascular disease, previous stroke, diabetes and graphs each containing a meaning) corresponding to the aim

cancer. Most participants had several comorbidities. of the present study were then identified, and the extracted

At the time of inclusion, five participants lived with a text (i.e. meaning units relating to death and dying) was then

spouse and three lived alone. All lived at home and received condensed and coded. The coded units were re-read,

haemodialysis as outpatients. Their ages ranged from compared, interpreted and when appropriate re-combined.

66–87 years (mean = 78). They had received MHD from Thereafter, they were abstracted and sorted into subthemes

15 months to just over seven years. and themes of underlying meaning (Graneheim & Lundman

2004). To gain a deeper understanding during the analysis,

meaning units of all interviews of each participant were both

Ethical considerations

compared over time and analysed as a whole. The analysis

Dialysis nurses gave selected patients a letter about the study process is described as linear, but there was a movement,

including an offer to meet the researcher for additional back and forth, between the described steps of the analysis.

information. Before giving written consent to participation, The software Open Code (2007) was used in the process of

all participants received further information, both written coding to more easily gain an overview of the data through

and verbal, describing the aim of the study, the voluntary printing lists of the coded units.

nature of their participation, their right to discontinue at any

time and the confidential treatment of data. These severely ill

Results

participants narrated their thoughts and feelings, which

required the researcher to be thoughtful and sensitive during When living with MHD and approaching the end of life, the

interviews. The study was approved by the Ethical Review presence of death was multifaceted. Patients’ thoughts and

Board Stockholm, Sweden. feelings about death and dying were complex, and they

fluctuated, both during and between interviews, as existential

issues and needs are intertwined with experiences in physical,

Data collection

social and psychological dimensions.

Data were collected for the study using qualitative serial The findings were formulated as 10 subthemes and three

interviews during 2007–2008. Six of the participants were themes, which are presented in Table 1 and illustrated in the

followed according to the plan with four interviews over text with representative quotations from the interviews. To

12 months. One participant was interviewed five times, communicate and illuminate the participants’ inner thoughts

because one interview was interrupted. Owing to family and feelings, quotations are presented as poems. The

matters, one participant was interviewed twice. The partic- technique we used means that the words are still presented

ipants were encouraged to talk freely about their experiences verbatim, but the text is divided into lines when semantic

of being ill and living with MHD. The interviews began with features as pauses and hesitation appear (cf. Edvardsson et al.

the open-ended question (Kvale & Brinkmann 2009): ‘Please 2003, Öhlén 2003, Lindqvist et al. 2006, Schuster 2006).

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159 2151

L Axelsson et al.

Table 1 Subthemes and themes you think

what will happen to me

Subthemes Themes

what will the end be like

Being reminded of death and dying Being aware that that’s on your mind

by the deteriorating body death may be near

Being reminded of death and dying by the The state of very ill fellow patients had different meanings

worsening conditions and deaths depending on the participant’s own condition. One partici-

of fellow patients

pant described that in comparison with some other patients,

Knowing dialysis treatment as a

border to death

he thought that he himself had managed well, which made

Looking upon death as natural Adapting to him feel stronger. However, later, when he was more ill, he

Preparing to face death approaching death expressed distress about seeing others’ worsening conditions.

Hoping for a quick death The number of deaths among fellow patients raised internal

Repressing thoughts of death and dying questions about what was happening and whose turn would

Wish to avoid burdening family Being alone with

be next. This also contributed to fears about going to hospital

Lack of communication with existential thoughts

healthcare professionals because of an acute condition. One participant described his

Haemodialysis withdrawal as a feelings when a fellow patient had died:

hypothetical option

Death came closer

you know

Being aware that death may be near since I’d come to the dialysis ward two had died

and this was the third one

Being aware that death may be near involved being reminded

so then

of death and dying by the deteriorating body, by the

it sort of reminds you of approaching something

worsening conditions or deaths of fellow patients, and by

I don’t usually think of it

knowing MHD as a border to death.

but when you get this kind of reminder

The participants were aware that death might come soon.

how fast it may go

Their progressively deteriorating bodies reminded them of

then you think it over

their approaching death, and some types of pain seemed

and wonder how long you will last

especially to involve a threat of imminent death. Relief of

pain and other symptoms was comforting and allowed some The closeness of death was also expressed by descriptions of

distance from death, although they were aware that manag- MHD as a border between life and death, sometimes

ing symptoms did not necessarily imply a longer lifetime. Old apparent in the body between dialysis treatments. Some

age in itself also raised awareness of approaching death. participants said that death had become a threat already

when informed of the necessity of MHD, and they had not

Sometimes I think

expected to live as long as they had.

well

is this the so-called final journey

Adapting to approaching death

if I travel by ambulance to the hospital

Adapting to approaching death involved looking upon death

or

as natural and preparing to face it, but also hoping for a

how will it feel

quick death and repressing thoughts of death and dying.

I am also so old

The older participants looked upon death as something

that I know

natural for the old and ill. Thus, death was described as an

that there are many who can’t make it this far

inevitable part of everybody’s life, and that they had lived

The participants described how the worsening conditions and their lives.

deaths of fellow patients at the dialysis clinic reminded them

It is not that strange

of their own vulnerable situation and caused them to wonder

actually

about the end of life and death.

that a person passes away

You see other patients on the dialysis ward who have problems who is ill

you notice how they deteriorate

Feelings of living too long and living a prolonged life were

and

also described, but at the same time, participants wanted to

you hope that it won’t last long

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

2152 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159

End of life and palliative care Thoughts on death and dying

live longer, and thinking of death as normal still involved Moreover, all their children had been present when they

sadness. woke up from unconsciousness, which was also reassuring.

Participants used different ways to prepare to face death.

I have experienced it so I know it

Reading the obituary notices to compare ages emerged as a

what it is like to pass away

way of handling uncertainty through looking for clues, but

so I am not afraid of dying

was also part of reconciling with approaching end of life.

you just fall asleep

Participants reflected on what the cause of death would be

considering all their comorbidities, when and how death Repressing thoughts of death and dying was another way to

would come, and what dying would be like. On the other handle distress and sorrow when approaching the end of life.

hand, participants also said that there was no meaning in Living was easier without the burden of thinking of death,

trying to figure out death. even if death was considered as natural.

Well it isn’t this week anyway No

I think one definitely must not think about it

but that one will die

but sometimes I have to no

I realize that one definitely should not do that

that it will happen one day

I: What is your thinking?

and then I wonder which day

will be the one No

when I can’t walk if I were to go around and think of dying

when I get an infection they can’t find then

when the medicine has no effect then it would be terrible

and then maybe they will lose interest in doing anything no

and I don’t do that

well

Repressing thoughts of dying emerged as a way to distance

I can’t do much about it

and postpone death, not as denial, but as a way to focus on

I hope it won’t be too drawn out

living. Instead, participants turned their thoughts towards the

Participants appeared to fear the end of life more than death good things in life.

itself. Their hopes for a quick death seemed to be connected

to their uncertainty about end of life and dying. They feared a Being alone with existential thoughts

drawn-out end of life totally incapacitated and dependent on Being alone with existential thoughts involved to avoid bur-

others. There was also a sincere wish to live at home until dening family, lack of communication with healthcare pro-

they died a sudden death. fessionals and reflections on MHD withdrawal as a

hypothetical option. Participants found it difficult to talk

That is what I fear the most

about their thoughts and feelings concerning death and dying.

becoming totally dependent on others

They did not want to burden their family additionally with

that is the worst

their existential thoughts. They thought their family did not

yes the best would be to drop dead

want to talk of death, and some described their family as

I think

afraid. Some participants had tried to talk about end of life

A sudden death was acknowledged as more difficult for the and death, but felt that their concerns were pushed away.

family, but one participant reflected that death now would Therefore, they kept existential thoughts to themselves, and

not be sudden in the meaning of unexpected because the everyday life was carried on trying to be as usual. Participants

family must have noticed his weakening condition. Although also described not knowing how to deal with this complex

they hoped for a quick death, the chance of it happening was situation.

also a threat, as hoping for a quick death was not the same as

Well I don’t know if

wanting to die soon.

if maybe one should prepare oneself for

Two participants thought they had already experienced

for the future

what death is like. Therefore, they did not fear the moment of

and perhaps prepare others as well

death, because they now thought of death as falling asleep.

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159 2153

L Axelsson et al.

I don’t know because ‘physicians are not allowed to put somebody to

I am not quite sure about how to deal with it death’.

sometimes I think to myself about it Death by MHD withdrawal did not emerge as a real

but alternative for the participants. Some had reflected on the

I probably can’t speak to anyone else about it possibility, as a hypothetical option in a different family

situation or if they became totally dependent on care.

Participants’ need to talk about existential issues, fears and

uncertainties varied over time with complications or critical Sometimes I can reason that if I did not have a wife who is strong and

events. They also described hesitation and uncertainty about able

talking to healthcare professionals about death and dying and and children and grandchildren

found it difficult to bring up existential topics. The impor- if I did not have family and all

tance of trust and continuity was described. The significance then maybe I would have discontinued dialysis

of talking to the right person and of healthcare professionals simply ended

showing interest was emphasised. One participant described

not knowing whether the care professionals were cowards or You want to go to the toilet, take a shower, wash yourself, brush

considerate when they avoided talking of his vulnerable your teeth

illness situation. Participants also thought that the care and all those sorts of things you always do

professionals had other things to attend to. Another reason and if I couldn’t do those things

not to open up was a fear that care professionals would be then that would

careless with thoughts and sentiments revealed in confidence. that would probably be the end

Participants described not having anyone to talk to about and then I could imagine

existential thoughts. Having to manage those thoughts alone I could imagine to discontinue dialysis

was attributed partly to the feeling that nobody would because I don’t want to

understand. I don’t want to be totally dependent on care

When a fellow patient had died, the atmosphere in the

The hypothetical criteria for MHD withdrawal as an option

haemodialysis unit was described as silent. Usually the nurses

changed over time. Also views of withdrawal could change.

answered the direct question of whether a patient had died,

One participant did not consider MHD withdrawal an

but they were reluctant to talk further. The participants said

alternative, as he wanted to hold on as long as possible.

that they understood that the nurses were not allowed to tell

Yet later, as he lost more and more control over his

them about their fellow patients, but still, when they thought

deteriorating body, he reflected on dialysis withdrawal as a

of the dead patient as a friend with whom they had talked

possibility one day. Another participant, who in the first

and laughed during dialysis, it was hard.

interview, reflected on withdrawal as a hypothetical option,

Being alone with existential thoughts also involved reflec-

when more ill and closer to death, then instead thought of

tions on MHD withdrawal. Some participants appeared to

MHD withdrawal as suicide. Length of life seemed to have

want to know more about death by withdrawal but feared

more value when he was closer to death, in spite of the

that bringing up the topic might be understood as wanting to

increased dependence he had earlier feared. He did not want

discontinue dialysis treatment. Withdrawal was also de-

to leave this life or his family. On the other hand, even if

scribed as a delicate matter that could be provocative if raised

withdrawal was not considered an option, some participants

by healthcare professionals. One participant described when

reflected on the value of prolonging life vs. maintaining well-

he had tried to talk to a nurse about dialysis withdrawal:

being at the end of life, and postponing death was not always

I asked what will happen if I quit this regarded as crucial. One participant described her agony

he just looked at me when she suffered from restrictions:

you’ll die

The question is whether I draw out a few months more or less

he said and left

of the time that I have left

well that I knew

that is in my condition

I thought to myself

see

Participants had various conceptions about MHD with- I don’t know how to express it but

drawal, including that it involved a death in agony. One but for me it is almost better to die

participant thought that withdrawal was not permitted than to be suffering this way

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

2154 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159

End of life and palliative care Thoughts on death and dying

Narratives revealed ambivalent thoughts and feelings about they were unable to talk about it. Still, even when partici-

life and death in patients suffering from illness and a pants focused on living, death was always nearby. This may

deteriorating body in pain. be interpreted as patients maintain a subtle balance between

recognising approaching death and recognising remaining life

In a way I don’t want to live any longer see

(Hallberg 2004).

with this that I know

The participants’ wish to focus on living was also shown by

that I will not get well again

their reflections on withdrawal of MHD as a hypothetical

but on the other hand

option, but not as a real alternative. Findings indicate that

one doesn’t exactly want to die either

attitudes towards withdrawal and circumstances for consid-

ering it may change over time. This changeability, along with

Discussion

participants’ lack of knowledge and fears of being misread if

This qualitative study focused on the inner thoughts and they ask about withdrawal, highlights the importance and

feelings about death and dying in severely ill patients living challenges of attentive listening and communication with

with MHD approaching end of life. Participants were aware patients.

of their approaching death, but lived with the uncertainty of Participants in the present study did not want to burden

how and when it would happen. While they focused on their family additionally with their existential concerns. Their

living, their narratives reveal that thoughts of death and desire to protect their family by not speaking of their worries

dying were never far away. The presence of death is and fears, however, left them facing the existential loneliness

multifaceted and intertwined with other dimensions of life, also described in patients with other diseases approaching the

and existential thoughts and feelings may fluctuate or change end of life (Sand & Strang 2006, Ek & Ternestedt 2008).

over time. Moreover, the individual perspective, depending Being alone with existential thoughts involved lack of

on experiences, values and age, is vital. communication with healthcare professionals and difficulties

Older participants thought of death as natural and that raising existential topics. Participants’ hesitation is in line

life had to end at some point. Participants feared the with other studies showing that patients often wait for care

uncertain end of life more than death itself. Their evident professionals to initiate talks about death and dying (Davison

fear of a prolonged end of life when being totally dependent 2006, Davison & Simpson 2006). Our findings indicate that

on others agrees with results of other studies of older patients want more communication concerning end of life, as

peoples’ views of death (Hallberg 2004, Ternestedt & shown also by Berzoff et al. (2008).

Franklin 2006, Gott et al. 2008). Participants in the present Unrecognised existential needs have earlier also been

study expressed hopes for a sudden or quick death. This reported in patients with cancer and heart failure (Adelbratt

may be interpreted as a wish to escape progressive losses & Strang 2000, Murray et al. 2004). Obstacles to existential

and suffering as they are facing threats of complications, support were described as healthcare professionals’ stress,

and of losing control, sense of self and dignity (Axelsson fear and lack of knowledge (Strang et al. 2001). This is in line

et al. 2012). Our data indicate that also a worsening with the present findings where participants described care

condition and dying process of fellow patients caused fears professionals’ lack of interest, avoidance and attention to

about the participant’s own end of life. A preference for other priorities in relation to communicating about existen-

sudden death in older people with heart failure was tial issues. Participants also said that it was difficult for others

discussed in terms of maintaining personhood until death to understand their situation, which may be another reason

and avoiding the process of dying, which coincides with not to talk of existential matters.

present findings (Gott et al. 2008). Participants’ thoughts on death show that they lived with

Our findings indicate that adapting to approaching death awareness of that death may be near. Their awareness seemed

and thinking of death as natural also involved repressing to be based on signs and inferences rather than on open

thoughts of death. This seemed a way to distance sorrow and communication with healthcare professionals. Findings illu-

death, to focus on living and to enjoy life, as also described by minate that awareness may be consistent with repressing

Calvin (2004) in a theory of personal preservation in patients thoughts on death to focus on living. Thoughts were also

on MHD treatment. Repressing thoughts of death shows a repressed of consideration to family members or because of

will to live (Gadamer 2003). On the other hand, Hallberg healthcare professionals’ behaviour, which may also obstruct

(2004), in a study of older people, discusses pushing away communication on existential issues and add to patients’

death in relation to a taboo of talking about it. In the present existential loneliness. The significance of the interaction

study, participants also pushed away thoughts of death when between the person approaching end of life and those around

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159 2155

L Axelsson et al.

him, both family and professionals, is illuminated by Glaser future is one way to open a conversation that might include

and Strauss (1965) in the theory on awareness of dying. Their existential topics, and it allows the patient to decide the

theory on communication on death and dying, still of clinical appropriate timing. It is also important to create a

relevance (Andrews & Nathaniel 2009), describes the signif- supportive relationship of safety and trust with patients

icance of behaviour and communication for the experience of and to take an interest in their subjective perspective and

end of life (Glaser & Strauss 1965). their whole person. Maintaining life with haemodialysis

The unpredictable course of dying in patients with heart treatment involves a responsibility to aim for the patient’s

failure made nurses in palliative care consider it difficult to well-being when approaching end of life. Thus present

talk about death (Brännström et al. 2005). This may also be findings forward that an integration of the palliative care

an impediment in haemodialysis care as death is often philosophy in haemodialysis units could assist in improving

unpredictable and uncertain. However, this could be a care of these severely ill patients, as the philosophy

challenge rather than an obstacle to nurses in haemodialysis acknowledges death as part of life, while still recognising

units as the individual need of the patient, living with a life and aiming for well-being until life has ended (Saun-

multifaceted presence of death, should direct communication, ders1978, WHO 2002).

and nurses should be attentive to fluctuating needs in their

unpredictable and uncertain course of dying. Findings indi-

Methodological considerations

cate that living with a deteriorating body, a high symptom

burden and dependence on advanced medical technology A weakness of the study may be that participants were

involves existential issues and suffering, and patients are included according to clinical assessments of severe illness,

often alone with their existential thoughts. Difficulties but on the other hand, clinical assessment of patients will also

expressing and sharing their suffering indicate increasing be used to implement the findings in clinical practice. In a

vulnerability in patients with life-threatening illness (Öhlén chronic progressive disease, it may be difficult to know when

2000) whose existential suffering could be alleviated if it were end of life begins but participants’ narratives show that they

acknowledged (Öhlén 2000). thought of life as closing down and of approaching death,

which adds to credibility. The purposive sampling, that is

choosing participants of various gender, family situation and

Conclusion

comorbidities from four different dialysis clinics thus with

Thoughts and feelings relating to death and dying are various experiences, also contributes to credibility. Interviews

significant and complex for persons living with MHD (31) over time yielded richness of data. As the participants

approaching the end of life. Participants lived with the were severely ill with progressive chronic diseases, the

awareness of approaching death but in uncertainty of how longitudinal approach also increased the possibility of iden-

and when. Adapting to approaching death included tifying changes and variations and thus increased the under-

repressing thoughts of death to focus on living the time standing. This strengthens the findings in relation to the

left. Participants were alone with existential issues, which number of participants. Repeated encounters in interviews

varied in intensity as they are intertwined and fluctuate over time facilitated conversations on existential issues,

with other dimensions of life. Findings indicate that it is which also contributed to richness and credibility. Three of

important for these patients to be able to talk about the authors read the interviews, and after open and reflective

existential issues to someone who will listen and that this discussions, we agreed upon subthemes and themes. The

need may vary both with the individual and with circum- authors’ different preunderstandings of the phenomenon

stances over time. under study contributed to critical reflections and analysis,

which add to credibility and thus trustworthiness (Graneheim

& Lundman 2004). The methodological analysis together

Relevance to clinical practice

with representative quotations further contributes to trust-

Healthcare professionals in haemodialysis settings need to worthiness. Presenting the quotations as poems (i.e. we

combine technical and medical abilities with committed divided the verbatim text into lines) (i.e. Edvardsson et al.

listening and communication skills. They need to address 2003, Öhlén 2003, Lindqvist et al. 2006, Schuster 2006) is a

existential thoughts and feelings, as well as physical and method to communicate and read participants’ quotations

psychosocial issues, and offer opportunities to talk about more slowly and thereby more deeply and thus being more

death and dying, with sensitivity to individual and change- sensitive to participants and their narratives as how it is

able needs. Asking patients about their thoughts for the spoken contributes to understanding.

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

2156 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159

End of life and palliative care Thoughts on death and dying

We consider findings to be transferable to similar contexts

Contributions

and of value also in the care of other groups of patients in the

haemodialysis unit, and the detailed description of partici- Study design: LA, IR, SHJ, BK; data collection: LA; data

pants and context facilitates judgements of transferability. analysis: LA, IR, BK and manuscript preparation: LA, IR,

CLH, SHJ, BK.

Acknowledgement

Conflict of interest

This research was supported by Sophiahemmet Foundation,

Stockholm. The authors declare to have no conflict of interests.

References

Adelbratt S & Strang P (2000) Death anxiety stage renal disease: the patient tion. Advances in Chronic Kidney Dis-

in brain tumour patients and their perspective. Clinical Journal of the ease 15, 133–139.

spouses. Palliative Medicine 14, 499– American Society of Nephrology 1, Glaser BG & Strauss AL (1965) Awareness

507. 1023–1028. of Dying. Aldine, Chicago, IL.

Andrews T & Nathaniel AK (2009) Davison SN & Jhangri GS (2010) Impact of Gott M, Small N, Barnes S, Payne S &

Awareness of dying revisited. Journal of pain and symptom burden on the Seamark D (2008) Older people’s views

Nursing Care Quality 24, 189–193. health-related quality of life of hemod- of a good death in heart failure: impli-

Axelsson L, Randers I, Jacobson SH & ialysis patients. Journal of Pain and cations for palliative care provision.

Klang B (2012) Living with haemodia- Symptom Management 39, 477–485. Social Science & Medicine 67, 1113–

lysis when nearing end of life. Scandi- Davison SN & Simpson C (2006) Hope and 1121.

navian Journal of Caring Sciences 26, advance care planning in patients with Graneheim UH & Lundman B (2004)

45–52. end stage renal disease: qualitative Qualitative content analysis in nursing

Berzoff J, Swantkowski J & Cohen LM interview study. British Medical Jour- research: concepts, procedures and

(2008) Developing a renal supportive nal 333, 886. measures to achieve trustworthiness.

care team from the voices of patients, Davison SN, Jhangri GS & Johnson JA Nurse Education Today 24, 105–112.

families, and palliative care staff. (2006) Cross-sectional validity of a Gregory DM, Way CY, Hutchinson TA,

Palliative and Supportive Care 6, 133– modified Edmonton symptom assess- Barrett BJ & Parfrey PS (1998) Patients’

139. ment system in dialysis patients: a perceptions of their experiences with

Brännström M, Brulin C, Norberg A, simple assessment of symptom bur- ESRD and hemodialysis treatment.

Boman K & Strandberg G (2005) Being den. Kidney International 69, 1621– Qualitative Health Research 8, 764–

a palliative nurse for persons with 1625. 783.

severe congestive heart failure in Edvardsson D, Rasmussen BH & Riessman Hagren B, Pettersen IM, Severinsson E,

advanced home care. European Journal CK (2003) Ward atmospheres of horror Lutzen K & Clyne N (2001) The hae-

of Cardiovascular Nursing 4, 314–323. and healing: a comparative analysis of modialysis machine as a lifeline: expe-

Calvin AO (2004) Haemodialysis patients narrative. Health: An Interdisciplinary riences of suffering from end-stage

and end-of-life decisions: a theory of Journal for the Social Study of Health, renal disease. Journal of Advanced

personal preservation. Journal of Ad- Illness and Medicine 7, 377–396. Nursing 34, 196–202.

vanced Nursing 46, 558–566. Eggers PW (2011) Has the incidence of end- Hagren B, Pettersen IM, Severinsson E,

Cohen LM & Germain MJ (2005) The stage renal disease in the USA and other Lutzen K & Clyne N (2005) Mainte-

psychiatric landscape of withdrawal. countries stabilized? Current Opinion nance haemodialysis: patients’ experi-

Seminars in Dialysis 18, 147–153. in Nephrology and Hypertension 20, ences of their life situation. Journal of

Cohen LM, Germain M, Poppel DM, 241–245. Clinical Nursing 14, 294–300.

Woods A & Kjellstrand CM (2000a) Ek K & Ternestedt BM (2008) Living with Hallberg IR (2004) Death and dying from

Dialysis discontinuation and palliative chronic obstructive pulmonary disease old people’s point of view. A literature

care. American Journal of Kidney Dis- at the end of life: a phenomenological review. Aging Clinical and Experimen-

eases 36, 140–144. study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62, tal Research 16, 87–103.

Cohen LM, Germain MJ, Poppel DM, 470–478. Harrison K & Watson S (2011) Palliative

Woods AL, Pekow PS & Kjellstrand Gadamer H-G (2003) Den gåtfulla hälsan: care in advanced kidney disease: a

CM (2000b) Dying well after discon- essäer och föredrag (On the Mystery of nurse-led joint renal and specialist pal-

tinuing the life-support treatment of Health: Essays and Lectures). Dualis liative care clinic. International Journal

dialysis. Archives of Internal Medicine Förlag, Ludvika, Sweden. of Palliative Nursing 17, 42–46.

160, 2513–2518. Germain MJ & Cohen LM (2008) Main- Kimmel PL & Patel SS (2006) Quality of

Davison SN (2006) Facilitating advance taining quality of life at the end of life life in patients with chronic kidney dis-

care planning for patients with end- in the end-stage renal disease popula- ease: focus on end-stage renal disease

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159 2157

L Axelsson et al.

treated with hemodialysis. Seminars in ratives in empirical phenomenological Disease in the United States. National

Nephrology 26, 68–79. inquiry into human suffering. Quali- Institutes of Health, National Institute

Kurella Tamura M & Cohen LM (2010) tative Health Research 13, 557–566. of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney

Should there be an expanded role for Open Code (2007) UMDAC and Epidemi- Diseases, Bethesda, MD.

palliative care in end-stage renal dis- ology, Version 3.4. Department of Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, Rot-

ease? Current Opinion in Nephrology Public Health and Clinical Medicine, ondi AJ, Cohen LM, Zeidel ML &

and Hypertension 19, 556–560. University of Umeå, Umeå. Arnold RM (2003) Symptom burden,

Kvale S & Brinkmann S (2009) Interviews: Saini T, Murtagh FE, Dupont PJ, McKin- quality of life, advance care planning

Learning the Craft of Qualitative Re- non PM, Hatfield P & Saunders Y and the potential value of palliative care

search Interviewing. Sage Publications, (2006) Comparative pilot study of in severely ill haemodialysis patients.

Thousand Oaks, CA. symptoms and quality of life in cancer Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation

Lindqvist O, Widmark A & Rasmussen BH patients and patients with end stage 18, 1345–1352.

(2006) Reclaiming wellness – living renal disease. Palliative Medicine 20, Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Rot-

with bodily problems, as narrated by 631–636. ondi AJ, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ &

men with advanced prostate cancer. Sand L & Strang P (2006) Existential lone- Switzer GE (2004) Development of a

Cancer Nursing 29, 327–337. liness in a palliative home care setting. symptom assessment instrument for

Madar H, Gilad G, Elenhoren E & Sch- Journal of Palliative Medicine 9, 1376– chronic hemodialysis patients: the

warz L (2007) Dialysis nurses for pal- 1387. Dialysis Symptom Index. Journal of

liative care. Journal of Renal Care 33, Saunders C (1978) The philosophy of ter- Pain and Symptom Management 27,

35–38. minal care. In The Management of 226–240.

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Worth A & Terminal Disease (Saunders C ed.). Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Fine

Benton TF (2004) Exploring the spiritual Edward Arnold, London, pp. 193–202. MJ, Levenson DJ, Peterson RA &

needs of people dying of lung cancer or Schuster M (2006) Profession och existens Switzer GE (2005) Prevalence, severity,

heart failure: a prospective qualitative (Profession and Existence). Daidalos, and importance of physical and

interview study of patients and their ca- Gothenburg (In Swedish). emotional symptoms in chronic he-

rers. Palliative Medicine 18, 39–45. SNR (2010) Svenskt njurregister (Swedish modialysis patients. Journal of the

Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J & Higginson Renal Registry) Annual Data Report, American Society of Nephrology 16,

IJ (2007) The prevalence of symptoms Jönköping. 2487–2494.

in end-stage renal disease: a systematic Strang S, Strang P & Ternestedt BM (2001) WHO (2002) World Health Organization

review. Advances in Chronic Kidney Existential support in brain tumour DefinitionofPalliativeCare.Availableat:

Disease 14, 82–99. patients and their spouses. Supportive http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/

Öhlén J (2000) Att vara i en fristad, berät- Care in Cancer 9, 625–633. definition/en/ (accessed 12 May 2011).

telser om lindrat lidande inom palliativ Ternestedt BM & Franklin LL (2006) Ways Young S (2009) Rethinking and integrating

vård (Being in a Lived Retreat: Narra- of relating to death: views of older nephrology palliative care: a nephrol-

tives of Alleviated Suffering Within people resident in nursing homes. ogy nursing perspective. Journal of the

Palliative Care). University of Gothen- International Journal of Palliative Canadian Association of Nephrology

burg, Gothenburg (In Swedish) (Sum- Nursing 12, 334–340. Nurses and Technicians 19, 36–44.

mary in English). USRD (2010) US Renal Data System

Öhlén J (2003) Evocation of meaning Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic

through poetic condensation of nar- Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

2158 Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159

End of life and palliative care Thoughts on death and dying

The Journal of Clinical Nursing (JCN) is an international, peer reviewed journal that aims to promote a high standard of

clinically related scholarship which supports the practice and discipline of nursing.

For further information and full author guidelines, please visit JCN on the Wiley Online Library website: http://

wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jocn

Reasons to submit your paper to JCN:

High-impact forum: one of the world’s most cited nursing journals and with an impact factor of 1Æ228 – ranked 23 of 85

within Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Report (Social Science – Nursing) in 2009.

One of the most read nursing journals in the world: over 1 million articles downloaded online per year and accessible in over

7000 libraries worldwide (including over 4000 in developing countries with free or low cost access).

Fast and easy online submission: online submission at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jcnur.

Early View: rapid online publication (with doi for referencing) for accepted articles in final form, and fully citable.

Positive publishing experience: rapid double-blind peer review with constructive feedback.

Online Open: the option to make your article freely and openly accessible to non-subscribers upon publication in Wiley

Online Library, as well as the option to deposit the article in your preferred archive.

Ó 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21, 2149–2159 2159

You might also like

- CreativeWriting12 Q1 Module-1Document28 pagesCreativeWriting12 Q1 Module-1Burning Rose89% (140)

- Project Report in JSWDocument44 pagesProject Report in JSWmohd arif khan73% (15)

- O&S April 2009Document134 pagesO&S April 2009Didi Menendez100% (20)

- HHS Public AccessDocument17 pagesHHS Public AccessChika SabaNo ratings yet

- Grothe Et Al., 2013Document13 pagesGrothe Et Al., 2013mackenzie.lacey28No ratings yet

- 2017 Juliaom - PSC PDFDocument10 pages2017 Juliaom - PSC PDFIka Nur AnnisaNo ratings yet

- Dying Means Suffocating, Perceptions of People Living With COPD Facing End of LifeDocument8 pagesDying Means Suffocating, Perceptions of People Living With COPD Facing End of LifetourfrikiNo ratings yet

- Emotional Distress in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure: ReviewDocument11 pagesEmotional Distress in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure: ReviewCândida MineiroNo ratings yet

- Eilertsen BJRK Kirkevold 2010Document11 pagesEilertsen BJRK Kirkevold 2010Anh HuyNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Costs of Care For Patients With Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument11 pagesDeterminants of Costs of Care For Patients With Alzheimer's DiseaseBenny TjanNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 14 1281878Document10 pagesFpsyg 14 1281878dr.joneidiNo ratings yet

- Lived Through Past Experienced Present Anticipated Future Understanding Existential Loss in The Context of Life Limiting IllnessDocument16 pagesLived Through Past Experienced Present Anticipated Future Understanding Existential Loss in The Context of Life Limiting Illnessfrancheskaam27No ratings yet

- The Effect of Depression On The Quality 0f Life of Patient With Cervical Cancer at Dr. Moewardi Hospital in SurakartaDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Depression On The Quality 0f Life of Patient With Cervical Cancer at Dr. Moewardi Hospital in SurakartaEndahNo ratings yet

- Applied Nursing Research: Mi-Kyoung Cho, PHD, Apn, Gisoo Shin, PHD, RNDocument7 pagesApplied Nursing Research: Mi-Kyoung Cho, PHD, Apn, Gisoo Shin, PHD, RNJoecoNo ratings yet

- The Bodily Presence of Significant Others Intensive Care Patients Experiences in A Situation of Critical IllnessDocument9 pagesThe Bodily Presence of Significant Others Intensive Care Patients Experiences in A Situation of Critical IllnessSara Daniela Benalcazar JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Risks Associated With Incident and Prevalent Periodontal DiseaseDocument8 pagesCardiovascular Risks Associated With Incident and Prevalent Periodontal DiseaseAlyaefkageNo ratings yet

- 12 Ustundag Orignial 9 3Document8 pages12 Ustundag Orignial 9 3Sanjivi GovekarNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Effective Pain Management in Sickle Cell DiseaseDocument4 pagesBarriers To Effective Pain Management in Sickle Cell DiseaseDr. Smiley JadonandanNo ratings yet

- Pre-Dialysis Patients ' Perceived Autonomy, Self-Esteem and Labor Participation: Associations With Illness Perceptions and Treatment Perceptions. A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument10 pagesPre-Dialysis Patients ' Perceived Autonomy, Self-Esteem and Labor Participation: Associations With Illness Perceptions and Treatment Perceptions. A Cross-Sectional Studyandrada14No ratings yet

- Land Olt 2011Document13 pagesLand Olt 2011Windy TiandiniNo ratings yet

- A Review of EOLDocument33 pagesA Review of EOLinderaaputraaNo ratings yet

- Critical Reviews in Oncology / HematologyDocument18 pagesCritical Reviews in Oncology / HematologyLiterasi MedsosNo ratings yet

- Samson Et Al - Psychosocial Adaptation To Chronic IllnessDocument13 pagesSamson Et Al - Psychosocial Adaptation To Chronic IllnessRaquel PintoNo ratings yet

- Ten Minutes To Midnight: A Narrative Inquiry of People Living With Dying With Advanced Copd and Their Family MembersDocument11 pagesTen Minutes To Midnight: A Narrative Inquiry of People Living With Dying With Advanced Copd and Their Family MembersCeline WongNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Exercise Standards On The Quality of Life To People With Chronic DiseaseDocument18 pagesThe Effects of Exercise Standards On The Quality of Life To People With Chronic DiseaseMario LanzaNo ratings yet

- Mattsson 2011Document12 pagesMattsson 2011oh yuniNo ratings yet

- Concerns of Patients On Dialysis A Research Study PDFDocument15 pagesConcerns of Patients On Dialysis A Research Study PDFProdi S1- 1BNo ratings yet

- Depressive Symptoms and Dietary Adherence in Patients With End-Stage Renal DiseaseDocument10 pagesDepressive Symptoms and Dietary Adherence in Patients With End-Stage Renal Diseasebasti_aka_slimNo ratings yet

- Nurse and Social Worker Palliative Telecare Team and Quality of Life in Patients With COPD, Heart Failure, or Interstitial Lung DiseaseDocument12 pagesNurse and Social Worker Palliative Telecare Team and Quality of Life in Patients With COPD, Heart Failure, or Interstitial Lung DiseasejunhamanoNo ratings yet

- Personality Change Associated With Chronic Diseases: Pooled Analysis of Four Prospective Cohort StudiesDocument13 pagesPersonality Change Associated With Chronic Diseases: Pooled Analysis of Four Prospective Cohort StudiesDebora BergerNo ratings yet

- End of LifeDocument3 pagesEnd of LifeSiti Fatimahtusz07No ratings yet

- Multiple Sclerosis Lancet 2018Document15 pagesMultiple Sclerosis Lancet 2018Sarah Miryam CoffanoNo ratings yet

- Experiences of Psychological FlowerDocument8 pagesExperiences of Psychological Flowerlsj19950128No ratings yet

- Research Article: Turkish Journal of Psychiatry 2021 32 (4) :246-252Document8 pagesResearch Article: Turkish Journal of Psychiatry 2021 32 (4) :246-252Celine WongNo ratings yet

- Background of The Study and SOP - Quali Research2-1Document3 pagesBackground of The Study and SOP - Quali Research2-1Maricris I. AbuanNo ratings yet

- Ho 2013Document6 pagesHo 2013Vera El Sammah SiagianNo ratings yet

- Mia Pruefer - Health Literacy and Elhers-Danlos Syndrome Hypermobility TypeDocument14 pagesMia Pruefer - Health Literacy and Elhers-Danlos Syndrome Hypermobility TypeMia PrueferNo ratings yet

- Living With Advanced Parkinson's Disease: A Constant Struggle With UnpredictabilityDocument10 pagesLiving With Advanced Parkinson's Disease: A Constant Struggle With UnpredictabilityLorenaNo ratings yet

- ContentServer AspDocument8 pagesContentServer Aspstephanie eduarteNo ratings yet

- Birkefeld (2022)Document14 pagesBirkefeld (2022)Nerea AlvarezNo ratings yet

- 480 253 1057 1 10 20190424 PDFDocument8 pages480 253 1057 1 10 20190424 PDFdwiajaNo ratings yet

- Mazujnms v2n2p29 enDocument7 pagesMazujnms v2n2p29 enDoc RuthNo ratings yet

- Pain Neuroscience Education in Older Adults With Chronic Back and or Lower Extremity PainDocument12 pagesPain Neuroscience Education in Older Adults With Chronic Back and or Lower Extremity PainAriadna BarretoNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument4 pagesContent ServerEkaSaktiWahyuningtyasNo ratings yet

- End-Of-Life Care in The Icu: Supporting Nurses To Provide High-Quality CareDocument5 pagesEnd-Of-Life Care in The Icu: Supporting Nurses To Provide High-Quality CareSERGIO ANDRES CESPEDES GUERRERONo ratings yet

- Life Review Therapy For Older Adults With Moderate Depressive Symptomatology: A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled TrialDocument12 pagesLife Review Therapy For Older Adults With Moderate Depressive Symptomatology: A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled TrialAstridNo ratings yet

- PIIS1976131710600059Document11 pagesPIIS1976131710600059Marina UlfaNo ratings yet

- Losely Geriatric Paper 325Document7 pagesLosely Geriatric Paper 325api-532850773No ratings yet

- The Perception of Life and Death in Patients With End-Of-Life Stage Cancer: A Systematic Review of Qualitative ResearchDocument13 pagesThe Perception of Life and Death in Patients With End-Of-Life Stage Cancer: A Systematic Review of Qualitative ResearchPedro TavaresNo ratings yet

- Neurobiology of Resilience in Depression Immune and Vascular InsightDocument78 pagesNeurobiology of Resilience in Depression Immune and Vascular InsightMaria BelénNo ratings yet

- CHF 5Document8 pagesCHF 5Prameswari ZahidaNo ratings yet

- Tan Burden Distress Qol Informal Caregivers Lung CancerDocument11 pagesTan Burden Distress Qol Informal Caregivers Lung CancerRubí Corona TápiaNo ratings yet

- UncertaintyDocument16 pagesUncertaintymaya permata sariNo ratings yet

- Kaptein-Common-Sense Model-OsteoarthritisDocument9 pagesKaptein-Common-Sense Model-OsteoarthritisZyania MelchyNo ratings yet

- Shao2020 PDFDocument7 pagesShao2020 PDFAndrea ZambranoNo ratings yet

- EUTHADocument10 pagesEUTHAJena WoodsNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CKDDocument8 pagesJurnal CKDRatna Dewi CahyaniNo ratings yet

- Clarifying Dementia Risk Factors: Treading in Murky Waters: CommentaryDocument3 pagesClarifying Dementia Risk Factors: Treading in Murky Waters: CommentaryVazia Rahma HandikaNo ratings yet

- Chochinov - Dignity Therapy - A Feasibility Study of EldersDocument13 pagesChochinov - Dignity Therapy - A Feasibility Study of Eldersjuarezcastellar268No ratings yet

- Acarturk Et Al 2016Document11 pagesAcarturk Et Al 2016290971No ratings yet

- Kart Tune N 2010Document10 pagesKart Tune N 2010AndreiaNo ratings yet

- Orofacial Pain: From Basic Science to Clinical Management, Second EditionFrom EverandOrofacial Pain: From Basic Science to Clinical Management, Second EditionNo ratings yet

- Experiences of Adolescents Living with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus whilst Negotiating with the Society: Submitted as part of the MSc degree in diabetes University of Surrey, Roehampton, 2003From EverandExperiences of Adolescents Living with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus whilst Negotiating with the Society: Submitted as part of the MSc degree in diabetes University of Surrey, Roehampton, 2003No ratings yet

- RETREAT Framework Et Al. 2018Document12 pagesRETREAT Framework Et Al. 2018happyNo ratings yet

- Hudson 2005Document13 pagesHudson 2005happyNo ratings yet

- Hendrix 2011Document21 pagesHendrix 2011happyNo ratings yet

- ChecklistDocument2 pagesChecklisthappyNo ratings yet

- Hendrix 2006Document6 pagesHendrix 2006happyNo ratings yet

- He Demand 2011Document9 pagesHe Demand 2011happyNo ratings yet

- Davison Et Al 2006Document5 pagesDavison Et Al 2006happyNo ratings yet

- Leadership Joyce 2016Document7 pagesLeadership Joyce 2016happyNo ratings yet

- Big DataDocument20 pagesBig DataBhavnita NareshNo ratings yet

- Essential Kitchen Bathroom Bedroom - September 2014 UKDocument164 pagesEssential Kitchen Bathroom Bedroom - September 2014 UKfishermantoys100% (1)

- Logic Gate Investigatory PDFDocument12 pagesLogic Gate Investigatory PDFGaurang MathurNo ratings yet

- UNICEF's Work in Public Finance For ChildrenDocument2 pagesUNICEF's Work in Public Finance For ChildrenCr CryptoNo ratings yet

- Bibliografía RazaDocument3 pagesBibliografía RazaJorge Vallejo KazacosNo ratings yet

- Plural of NounsDocument1 pagePlural of NounsStrafalogea Serban100% (2)

- 365DayPan DailyEnglishLessonPlanUPDATED2022Document379 pages365DayPan DailyEnglishLessonPlanUPDATED2022KATIUSCA EVELYN GONZALES RIVERANo ratings yet

- Workshop Living in The Czech Republic: WWW - Expatlegal.czDocument22 pagesWorkshop Living in The Czech Republic: WWW - Expatlegal.czImran ShaNo ratings yet

- Brand Engagement With Brand ExpressionDocument27 pagesBrand Engagement With Brand ExpressionArun KCNo ratings yet

- Le Conditionnel Présent: The Conditional PresentDocument8 pagesLe Conditionnel Présent: The Conditional PresentDeepika DevarajNo ratings yet

- Remunerasi RSDocument39 pagesRemunerasi RSalfanNo ratings yet

- Gate Induced Drain Leakage For Ultra Thin MOSFET Devices Using SilvacoDocument2 pagesGate Induced Drain Leakage For Ultra Thin MOSFET Devices Using Silvacosiddhant gangwalNo ratings yet

- NOTICEDocument126 pagesNOTICEowsaf2No ratings yet

- Count and Non-Count Nous (Plural Form of Nous)Document9 pagesCount and Non-Count Nous (Plural Form of Nous)Kathe TafurNo ratings yet

- 11.29.12 Post Standard, The Word Is Out New Law Protects Overdose Victims and HelpersDocument2 pages11.29.12 Post Standard, The Word Is Out New Law Protects Overdose Victims and Helperswebmaster@drugpolicy.orgNo ratings yet

- QTS AplicationDocument8 pagesQTS Aplicationandreuta23No ratings yet

- Reza Sitinjak CJR COLSDocument5 pagesReza Sitinjak CJR COLSReza Enjelika SitinjakNo ratings yet

- Casting High Quality C12A: Bradken Energy ProductsDocument37 pagesCasting High Quality C12A: Bradken Energy Productsdelta lab sangliNo ratings yet

- World War IDocument7 pagesWorld War IhzbetulkunNo ratings yet

- English Test-SMA-Kelas-XII-Semester-IDocument4 pagesEnglish Test-SMA-Kelas-XII-Semester-IAru HernalantoNo ratings yet

- Personality and Work Behaviour Exploring The 1996 PDFDocument18 pagesPersonality and Work Behaviour Exploring The 1996 PDFAtif BasaniNo ratings yet

- EstimationDocument106 pagesEstimationasdasdas asdasdasdsadsasddssa0% (1)

- Final For ReviewDocument39 pagesFinal For ReviewMichay CloradoNo ratings yet

- Catholic Ghost Stories of Western PennsylvaniaDocument5 pagesCatholic Ghost Stories of Western PennsylvaniaeclarexeNo ratings yet

- Marketing Research ProcessDocument3 pagesMarketing Research Processadnan saifNo ratings yet

- Novo Nordisk AR 2011 enDocument116 pagesNovo Nordisk AR 2011 enINVESTORNEWNo ratings yet

- Stanford CS193p Developing Applications For iOS Fall 2013-14Document66 pagesStanford CS193p Developing Applications For iOS Fall 2013-14AbstractSoft100% (1)