Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Upload 3

Upload 3

Uploaded by

Naz Zeynep OrhanCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Introduction To Genetic Analysis 11th Edition Griffiths Solutions ManualDocument7 pagesIntroduction To Genetic Analysis 11th Edition Griffiths Solutions Manualdizewyzi0% (4)

- Elementary Statistics 2nd Edition Solutions Manual Navidi MonkDocument14 pagesElementary Statistics 2nd Edition Solutions Manual Navidi MonkxufaduxatoNo ratings yet

- Complaint For DefamationDocument17 pagesComplaint For DefamationjoshmclaurinNo ratings yet

- Miskito DictionaryDocument26 pagesMiskito DictionarycarlamadorNo ratings yet

- The 2016 Presidential Election-An Abundance of ControversiesDocument20 pagesThe 2016 Presidential Election-An Abundance of ControversiesHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- The 2016 Presidential Election-Identities, Class, and CultureDocument20 pagesThe 2016 Presidential Election-Identities, Class, and CultureHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- U.S. Congress, Presidency and The Courts The Presidential Election Process September 17, 2019Document37 pagesU.S. Congress, Presidency and The Courts The Presidential Election Process September 17, 2019Zachary WatsonNo ratings yet

- Summary of In Trump We Trust: by Ann Coulter | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of In Trump We Trust: by Ann Coulter | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Half-Time!: American public opinion midway through Trump's (first?) term – and the race to 2020From EverandHalf-Time!: American public opinion midway through Trump's (first?) term – and the race to 2020No ratings yet

- Προεδρικές 2024: Η προεγλογική εκστρατεία στις ΗΠΑDocument9 pagesΠροεδρικές 2024: Η προεγλογική εκστρατεία στις ΗΠΑARISTEIDIS VIKETOSNo ratings yet

- The 2016 US Presidential Campaign Political Communication and Practice by Robert E. Denton JR (Eds.)Document342 pagesThe 2016 US Presidential Campaign Political Communication and Practice by Robert E. Denton JR (Eds.)Eirini SotiropoulouNo ratings yet

- Reunited Nation?: American politics beyond the 2020 electionFrom EverandReunited Nation?: American politics beyond the 2020 electionNo ratings yet

- How to Beat Trump: America's Top Political Strategists on What It Will TakeFrom EverandHow to Beat Trump: America's Top Political Strategists on What It Will TakeNo ratings yet

- WWW Vox Com Policy and Politics 2017 10-5-16414338 Trump DemDocument12 pagesWWW Vox Com Policy and Politics 2017 10-5-16414338 Trump DemLeon BerishaNo ratings yet

- Why These Obama Voters Are Backing Donald Trump: Sizable Lead For TrumpDocument4 pagesWhy These Obama Voters Are Backing Donald Trump: Sizable Lead For TrumpBruno SilvaNo ratings yet

- Who Decides When The Party Doesn't? Authoritarian Voters and The Rise of Donald TrumpDocument6 pagesWho Decides When The Party Doesn't? Authoritarian Voters and The Rise of Donald TrumpRichNo ratings yet

- National Party Conventions in US PoliticsDocument4 pagesNational Party Conventions in US PoliticsGeorgia WowkNo ratings yet

- Business Statistics Canadian 3rd Edition Sharpe Solutions ManualDocument9 pagesBusiness Statistics Canadian 3rd Edition Sharpe Solutions ManuallelyhaNo ratings yet

- The Long Slog: A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The White HouseFrom EverandThe Long Slog: A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The White HouseNo ratings yet

- Concours Blanc Anglais VDSDocument2 pagesConcours Blanc Anglais VDSFrederique MenantNo ratings yet

- Kansas Thomas Snow Neg Emporia Round6Document41 pagesKansas Thomas Snow Neg Emporia Round6Sebastina GlosNo ratings yet

- 2016 Presidential ElectionDocument8 pages2016 Presidential ElectionKeegan HonasNo ratings yet

- Do We Have A Center?: 2016, 2020, and the Challenge of the Trump PresidencyFrom EverandDo We Have A Center?: 2016, 2020, and the Challenge of the Trump PresidencyNo ratings yet

- 5 With Debate Deal, Trump and Biden Sideline A Storied Campaign InstitutionDocument5 pages5 With Debate Deal, Trump and Biden Sideline A Storied Campaign InstitutionGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- USA 2025: How Republicans Could Take Over and Transform AmericaFrom EverandUSA 2025: How Republicans Could Take Over and Transform AmericaNo ratings yet

- Elections DA - 2016Document227 pagesElections DA - 2016Anonymous cGMk7iWNbNo ratings yet

- Charles E. Cook Jr. 2000. Polls and Models Which Numbers To Believe The Washington Quarterly (Autumn 2000) Volume 23 Number 4 Pp. 195-202Document8 pagesCharles E. Cook Jr. 2000. Polls and Models Which Numbers To Believe The Washington Quarterly (Autumn 2000) Volume 23 Number 4 Pp. 195-202Wu GuifengNo ratings yet

- Donald Trump and The Republican Party: The Making of A Faustian BargainDocument13 pagesDonald Trump and The Republican Party: The Making of A Faustian BargainKAMNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide To The Race For The White House - US News - The GuardianDocument7 pagesA Simple Guide To The Race For The White House - US News - The GuardianSeemantiniGuptaNo ratings yet

- ElectionnotebookDocument6 pagesElectionnotebookapi-329384437No ratings yet

- Annotated BibDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibapi-316486998No ratings yet

- Empire Strikes BackDocument6 pagesEmpire Strikes BackBanwa GrassNo ratings yet

- Presidential Elections in The USDocument2 pagesPresidential Elections in The USStefan RomanskiNo ratings yet

- Packer MemoDocument3 pagesPacker MemoElliotNo ratings yet

- 1 Donald Trump Coasts To Victory in The Iowa Republican CaucusesDocument2 pages1 Donald Trump Coasts To Victory in The Iowa Republican CaucusesGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- One Vote Away: How a Single Supreme Court Seat Can Change HistoryFrom EverandOne Vote Away: How a Single Supreme Court Seat Can Change HistoryRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (24)

- MAGA Inc Ad Verification 5/24/2023Document14 pagesMAGA Inc Ad Verification 5/24/2023Elias AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Current National Polling: October 4, 2016Document10 pagesCurrent National Polling: October 4, 2016NoFilter PoliticsNo ratings yet

- National Poll (October 4, 2016) v3Document10 pagesNational Poll (October 4, 2016) v3Breitbart NewsNo ratings yet

- Report On Donald TrumpDocument12 pagesReport On Donald TrumpAyaz Aslam100% (1)

- What Is Causing Donald Trumps Rise To Political Stardom - Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesWhat Is Causing Donald Trumps Rise To Political Stardom - Annotated BibliographySpencer Smith0% (1)

- Updates - 2020Document63 pagesUpdates - 2020vegSpamNo ratings yet

- 2016 Election and Beyond: What Did You Know? What You Need to Know: Educator’S PerspectiveFrom Everand2016 Election and Beyond: What Did You Know? What You Need to Know: Educator’S PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- Transition To: Trump Presidency BeginsDocument32 pagesTransition To: Trump Presidency BeginsThesouthasian TimesNo ratings yet

- History Says Bloomberg 2020 Would Be A Sure Loser - POLITICO MagazineDocument4 pagesHistory Says Bloomberg 2020 Would Be A Sure Loser - POLITICO MagazineifraNo ratings yet

- Transition Integrity Project: Background Concerns About The Legitimacy of The 2020 Presidential ElectionDocument7 pagesTransition Integrity Project: Background Concerns About The Legitimacy of The 2020 Presidential ElectionFred JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Hopes and Fears: Trump, Clinton, the voters and the futureFrom EverandHopes and Fears: Trump, Clinton, the voters and the futureNo ratings yet

- 149-Texto Do Artigo-335-1-10-20191210Document14 pages149-Texto Do Artigo-335-1-10-20191210Lorena RosaNo ratings yet

- US Presidential Election1Document4 pagesUS Presidential Election1Ziauddin ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Summary of Tired of Winning by Jonathan Karl: Donald Trump and the End of the Grand Old PartyFrom EverandSummary of Tired of Winning by Jonathan Karl: Donald Trump and the End of the Grand Old PartyNo ratings yet

- PresidentialqualitiesDocument5 pagesPresidentialqualitiesapi-313523039No ratings yet

- Democrats Will Hold On To The Senate-Money, History, and Voter Targeting and Turnout Favor The Democrat IncumbentsDocument5 pagesDemocrats Will Hold On To The Senate-Money, History, and Voter Targeting and Turnout Favor The Democrat Incumbentskellybye10No ratings yet

- How The News Media Helped To Nominate TrumpDocument5 pagesHow The News Media Helped To Nominate TrumpMariane NavaNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument5 pagesReportapi-312104079No ratings yet

- Jour 3796 PaperDocument9 pagesJour 3796 Paperapi-314087580No ratings yet

- Current Oregon Polling: October 7, 2016Document8 pagesCurrent Oregon Polling: October 7, 2016NoFilter PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Upload 1Document10 pagesUpload 1Naz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Trump vs. Hillary: What Went Viral During The 2016 US Presidential ElectionDocument19 pagesTrump vs. Hillary: What Went Viral During The 2016 US Presidential ElectionNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Changing Norms Following The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election: The Trump Effect On PrejudiceDocument7 pagesChanging Norms Following The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election: The Trump Effect On PrejudiceNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Media in Election ProcessesDocument4 pagesMedia in Election ProcessesNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Social Media For Political Campaigns: An Examination of Trump's and Clinton's Frame Building and Its Effect On Audience EngagementDocument13 pagesSocial Media For Political Campaigns: An Examination of Trump's and Clinton's Frame Building and Its Effect On Audience EngagementNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Winning On Social Media: Candidate Social-Mediated Communication and Voting During The 2016 US Presidential ElectionDocument10 pagesWinning On Social Media: Candidate Social-Mediated Communication and Voting During The 2016 US Presidential ElectionNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Allen Hulton - Sworn Affidavit - Ayers Family and Obama The Foreign Student - Sheriff Joe Investigation - 2012Document7 pagesAllen Hulton - Sworn Affidavit - Ayers Family and Obama The Foreign Student - Sheriff Joe Investigation - 2012ObamaRelease YourRecordsNo ratings yet

- Cassie Docksey TranscriptDocument48 pagesCassie Docksey TranscriptDaily KosNo ratings yet

- NIE Hyderabad 10-10-2023Document16 pagesNIE Hyderabad 10-10-2023Y Srinivasa RaoNo ratings yet

- 1 - FPJ V Arroyo. P.E.T. CASE No. 002Document5 pages1 - FPJ V Arroyo. P.E.T. CASE No. 002KhiarraNo ratings yet

- Constitution GroupDocument12 pagesConstitution GroupJoesh ChaulahNo ratings yet

- General Elections - 2004Document551 pagesGeneral Elections - 2004bharatNo ratings yet

- U.S. Senate Candidate Ruling - Shawnee District Court, KansasDocument22 pagesU.S. Senate Candidate Ruling - Shawnee District Court, KansasFindLawNo ratings yet

- Micopanetology 2Document56 pagesMicopanetology 2kcayceeNo ratings yet

- 2012 Journal of African Elections v11n1 Gender Politics 2011 Elections EisaDocument26 pages2012 Journal of African Elections v11n1 Gender Politics 2011 Elections EisannubiaNo ratings yet

- CISFDocument17 pagesCISFDarshan CrNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Nie BDocument14 pagesNie Badvancedgroup02No ratings yet

- Taking Sides Gilded Age PoliticsDocument11 pagesTaking Sides Gilded Age PoliticsRyan GibsonNo ratings yet

- 9QDEHY - 2019 Tesla Inc Press Release Annual Report - JGVR0PDocument232 pages9QDEHY - 2019 Tesla Inc Press Release Annual Report - JGVR0PHarshNo ratings yet

- 2015 Unofficial Clark County Primary CandidatesDocument9 pages2015 Unofficial Clark County Primary CandidatesCharlieWhite0% (1)

- Chris Barrow Late Show Writers PacketDocument6 pagesChris Barrow Late Show Writers PacketAnonymous 95gKovJKdONo ratings yet

- Corazon Aquinos SpeechDocument32 pagesCorazon Aquinos SpeechJan JanNo ratings yet

- 07-17-2013 EditionDocument28 pages07-17-2013 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Michigan State Democracy MVP ToolkitDocument16 pagesMichigan State Democracy MVP ToolkitWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitNo ratings yet

- National Liga NG Mga Barangay vs. Paredes Class NotesDocument6 pagesNational Liga NG Mga Barangay vs. Paredes Class NotesOnnie LeeNo ratings yet

- Finance Chapter 17Document30 pagesFinance Chapter 17courtdubs75% (4)

- Political Parties: Rationalised 2023-24Document17 pagesPolitical Parties: Rationalised 2023-24NEETU GOYALNo ratings yet

- Catanduanes - ProvDocument2 pagesCatanduanes - ProvireneNo ratings yet

- Case Digests: Topic Author Case Title GR No Tickler Date DoctrineDocument2 pagesCase Digests: Topic Author Case Title GR No Tickler Date Doctrinemichelle zatarain50% (2)

- Position PaperDocument2 pagesPosition PaperMaria Leanne A. Pancito100% (1)

- Electoral Commission LetterDocument6 pagesElectoral Commission LetterFred DzakpataNo ratings yet

- Term of OfficeDocument170 pagesTerm of OfficeFrederick IcaroNo ratings yet

Upload 3

Upload 3

Uploaded by

Naz Zeynep OrhanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Upload 3

Upload 3

Uploaded by

Naz Zeynep OrhanCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S.

Presidential Election

Author(s): Daron Shaw

Source: Zeitschrift für Politikberatung (ZPB) / Policy Advice and Political Consulting ,

Vol. 8, No. 1 (2016), pp. 15-23

Published by: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26427264

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Zeitschrift für Politikberatung (ZPB) / Policy Advice and Political Consulting

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election – Shaw | Aufsatz

Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S.

Presidential Election

Daron Shaw

Abstract formance in states that have not gone Republican in many

elections, I assume that 2016 was a different kind of elec-

Questions about the impact of U.S. presidential campai- tion. But it is unclear how much it differed from the Bush or

gning only grow more interesting after Donald Trump’s Obama races. Next, I am interested in the extent to which

surprising victory over Hillary Clinton in 2016. This traditional modes of campaigning were (or were not) effect-

paper assesses the claim that the election was, in fact, sur- ive in 2016. Like many in political science, I am skeptical

prising, as well as the effect of traditional modes of cam- about the efficacy of many sorts of campaign outreach, but

paigning—television advertising and candidate appearan- acknowledge the need to put this skepticism to the empirical

ces—in this race. The data show that although Trump’s test. To assess the nature of Trump’s election and the role of

pathway to victory was unusual, the election was not as the campaign, I focus on unique state-level data from the

much of an outlier as some might think. 2016 contest.

Context and Theory

Introduction The Path to the White House, circa 2016

In the wake of Republican Donald Trump’s victory over

On November 8, 2016, Republican presidential nominee

Democrat Hillary Clinton in the 2016 U.S. presidential elec-

Donald J. Trump won states worth 306 electoral votes,

tion, perhaps the most common response was surprise. More

defeating Democratic nominee Hillary R. Clinton, who won

specifically, journalists, pundits, and practitioners were

states worth 232 electoral votes.2 The election capped an

shocked that Trump had managed to win the Electoral Col-

extraordinary year featuring an open-contest to succeed the

lege despite trailing in most polls, despite being significantly

two-term Democratic incumbent president, Barack Obama.

out-spent, and despite several seemingly devastating scandals

The Republican nomination process drew 17 candidates,

and gaffes. A CNN.com article, entitled “Five Surprising

including several high-profile U.S. Senators (Ted Cruz,

Lessons from Trump’s Astonishing Win,” captured the

Marco Rubio, Rand Paul, Lindsay Graham, Rick Santo-

essence of this reaction:

rum), several governors (Jeb Bush, John Kasich, Scott

“The polls were wrong. Projection models were wrong. Walker, Chris Christie, Bobby Jindal, Rick Perry, George

Veterans of previous presidential campaigns were wrong. Pataki, Mike Huckabee, Jim Gilmore), prominent business

Trump's victory is one of the most stunning upsets in Ameri- executives (including Trump and Carly Fiorina), and even a

can political history. American voters swept Republicans well-known brain surgeon (Ben Carson). After the March 15

into power, handing the GOP the White House, the Senate primaries, only Trump, Cruz, and Kasich were left standing.

and the House in a wave that no one saw coming. Political Indeed, after months of talk about a contentious nomination

professionals will now spend the coming weeks and months fight and a “brokered” or “multi-ballot” convention, Trump

studying just how and why everyone missed it.”1 gained the majority of delegates he needed to win the

Republican nomination on May 19 with his win in North

A key component of this shock is that Trump’s campaign

Dakota, and was formally nominated at the party’s national

seemed to violate some (most?) of the basic rules with

convention on July 19 in Cleveland, Ohio.

respect to how an effective presidential campaign is run.

They did not raise very much money (in relative terms), and By contrast, Hillary Clinton—the heir-apparent given her

they did not spend on those aspects of the campaign that national standing and runner-up finish to Obama in the

most practitioners—and more than a few academics—think 2008 nominating contest—led a sparse Democratic field of

are vital to success: extensive television advertising and face- contenders. After easily dispatching Martin O’Malley and

to-face contacting. James Webb, she was left alone with Vermont Democratic-

But shock and surprise are emotional reactions, and can Socialist Bernie Sanders. Sanders, however, proved a

be rooted in an array of biased readings of data and events.

Now that the cold facts of the election are available, it is 1 Brader, Eric, “Five Surprising Lessons from Trump’s Astonishing Win”

(Nov. 9, 2016): http://www.cnn.com/2016/11/09/politics/donald-

useful to systematically examine our assumptions about the trump-wins-biggest-surprises/.

2016 contest. To begin with, I am interested in documenting 2 These totals also include split votes from Maine, which allocates elec-

the extent to which Trump’s election is, in fact, different tors through district-wide elections as well as the statewide vote. The

actual electoral vote was recorded as 304 for Trump to 227 for Clin-

from recent presidential contests in the United States. Based ton, with seven electors registering “protest” votes for other candi-

on Trump’s apparently unique coalition and his strong per- dates.

ZPB 1/2016 15

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Aufsatz | Shaw – Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election

formidable and stubborn foe. Sanders drew support from a strong leader, but without the requisite temperament, knowl-

coalition of younger, whiter, and more educated Democratic edge, and honesty to be president. Conversely, Clinton’s

voters, and scored a number of impressive victories over problem was more localized and perhaps more acute: she

Clinton, including upset wins in Michigan and Wisconsin. was viewed as insufficiently honest and trustworthy.

Clinton did not win the nomination until the June 7 Califor- To make their respective cases to voters, the campaigns

nia primary, and even then her margin was padded by dis- pursued divergent paths. Trump’s campaign lacked the

proportionate support from Democratic Party office-holders infrastructure and available cash (Trump loaned approxi-

and officials who serve as “unpledged delegates” to the mately $60 million to his campaign during 2016, but

national convention. She became the Democratic standard- refrained from a larger commitment) of Clinton’s, and they

bearer and the first major party female presidential nominee emphasized (1) earned media, (2) personal appearances, and

on July 24 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (3) digital targeting and outreach.3 To be sure, Trump’s cam-

With the major party conventions both concluded by paign was hardly invisible on the network and cable air-

August 1, the general election and its campaign began in waves. But they did not approach Clinton’s presence, nor

earnest. Except that both campaigns spent the late summer that for Obama or Romney in 2012. Clinton, on the other

raising money and laying the groundwork for the fall cam- side of the ledger, emphasized a combination of what was

paign. The Trump campaign used July and August to build a effective in her husband’s presidential campaigns (massive

digital infrastructure that was the focal point of its fundrais- television ad buys) and what was effective in Obama’s cam-

ing effort. While active on the airwaves (the campaign aired paigns (extensive, targeted, on-the-ground outreach). Both

TV ads on host network NBC during the Summer Olympics) candidates prepared extensively for the three debates, but

and in the field, the Clinton campaign also spent the late Clinton took considerable time off the trail to do so while

summer replenishing its coffers, which had been somewhat Trump continued to make appearances as he prepared.

depleted in wrestling control of the nomination from By the eve of the election, the consensus was that Clinton

Sanders. By Labor Day (September 5), however, both cam- was close to a sure-bet. The national and state-by-state polls

paigns had purchased much of their TV advertising for the mostly told a consistent story: Clinton was up by a few

fall campaign and were visiting multiple battleground states points nationally and held a slight edge in most of the battle-

on an almost daily basis. ground states. Of the eleven national polls published as part

Despite some outward similarities with previous cam- of the “Real Clear Politics” average on November 8, the day

paigns, the 2016 election featured a distinct context and two of the election, ten had Clinton ahead.4 The average was

unique candidates. The distinctiveness of the context resided Clinton +3.3 points. The statewide polling averages showed

in the fact that the out-going president was personally popu- Clinton with a lead in enough states to win 272 electoral

lar (with favorability ratings near 60%), but advanced pol- votes, while Trump had 266 electoral votes. Other “polling

icies that were not especially liked. Specifically, Obama’s sig- aggregators” showed a larger Clinton lead in the Electoral

nature legislative achievement—the Affordable Care Act of College. More complex analyses read these data and con-

2010—never had more than 50 percent support in public cluded that the Democrats were very likely to win the White

opinion polls, while his stimulus package—the Investment House. As shown in Table 1, the popular election forecast-

and Recovery Act of 2009—was widely panned by both ing site fivethirtyeight.com pegged Clinton’s chances for vic-

Republicans and liberal Democrats. Similarly, his executive tory at a 0.71 probability, while The New York Times’ “The

action granting legal status to nearly 11 million undocu- Upshot” had it at 0.87, and Huffington Post and the Prince-

mented workers was unpopular with a large segment of the ton Election Consortium had it over 0.99.

American population, as were his agreements with Iran and

(to a lesser degree) Cuba. Table 1. Media and Market Models of the 2016 Presidential

The economy, meanwhile, also produced a puzzling con- Election and the Actual Result

textual situation. While job growth had been consistent and

sizable since the end of the economic downturn of 2008-09, Model Description Probability

economic growth was anemic and income inequality Nate Silver (fiev- Polls plus historical tendencies and 0.71 for Clinton

increased substantially. In short, it wasn’t clear heading into thirtyeight.com) current conditions

the election whether things were getting better, getting The Upshot State and national polls 0.85 for Clinton

(New York

worse, or whether we were simply treading water. To be Times)

clear, polls indicated that Americans wanted a “change”; but

it was much less clear that this desire was linked to a rejec-

3 In the end, according to Brad Pascale (Trump’s Digital Director),

tion of the incumbent president or a desire to change econo- Trump ended up spending as much on digital outreach as on TV ads

mic policy. (about $100 million). Clinton campaign officials spent at least this

amount, but the ratio of digital to television was much more lop-

What was clear by Labor Day was that the major party sided in favor of TV (based on comments from “Roundtable Discus-

candidates were not viewed favorably by the American pub- sion: The General Election,” at Harvard University’s “Campaign for

lic. Trump’s favorability rating hovered around 30 percent, President: The Managers Look at 2016”).

4 All polls were four-way ballots with Johnson and Stein included. The

while Clinton’s tended to be about 5 points higher (occa- sole “pro-Trump” outlier was Investors’ Business Daily/TIPP Daily

sionally touching 40 percent). Americans viewed Trump as a Tracking, which had Trump ahead by two points.

16 ZPB 1/2016

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election – Shaw | Aufsatz

Model Description Probability dictable given their predispositions (partisan attachments)

Princeton Elec- State and national polls >0.99 for Clinton and objective circumstances (the state of the economy, and

tion Consortium the existence of war or peace) unless there are asymmetries

Huffington Post State-by-state averages and likely 0.98 for Clinton in either the volume or the quality of the campaigns. It is

vote counts

these campaign asymmetries that produce campaign effects;

Predictwise Prediction markets >0.99 for Clinton

(betting mar-

otherwise elections “merely” get people to where they

kets) “should” be by Election Day. Put another way, they do not

have independent effects on either voters or election out-

comes. This is why 2016 is so intriguing: If there were major

Why 2016 Might Have Been Unique

discrepancies in what Trump and Clinton did, and where

In some ways, the 2016 contest does not look all that dis- they did it, the campaign might have been a larger part of

tinct from recent presidential elections. As mentioned earlier, the explanation for 2016 than it typically is for presidential

it was an open contest with a somewhat popular (if polariz- elections.

ing) incumbent finishing his term and not up for re-election.

Although the sitting vice-president was not running, there Analyzing the 2016 Presidential Election

was a clear “heir to the throne” in the race. The economy

My focus in this article is on the question of predictability.

was viewed as improved but fragile. Since 1950, the only

To what degree was Trump’s vote different than what we

presidential elections that might be considered relevant com-

might have expected given recent presidential elections and

parisons are 1960 (Kennedy challenges Nixon, with con-

given the particular (non-campaign) conditions of 2016? To

cerns about recession in the air), 1968 (Nixon challenges

the extent that his vote was different than expected, how

Humphrey, with the economy strong but dragged down by

much did the campaign matter? In Table 2, we see that of

the Vietnam War), 1988 (Dukakis challenges G.H.W. Bush,

seven well-known political science models, four predicted a

with the economy showing some signs of slowing), and 2000

popular vote victory for Hillary Clinton and three predicted

(G.W. Bush challenges Gore, with the economy just begin-

a popular vote victory for Donald Trump. Furthermore, a

ning to slip into recession). Consistent with this interpreta-

couple of the models accurately predicted the final popular

tion, both political science forecasts and the polls offered a

vote. But it is consequential that none predicted a popular

similar expectation: a close election with perhaps a slight

vote victory for Clinton and an Electoral College victory for

edge to the “change” candidate.

Trump; we wish to know how predictable or unique the

In other ways, however, 2016 does not look at all like 2016 presidential election results were in the fifty states.

your typical presidential election. Most notably, electioneer-

ing scholars would readily point to the candidates and their

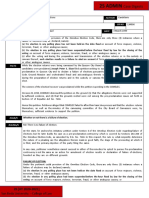

Table 2. Political Science Models of the 2016 Presidential Elec-

campaigns. The candidates were historically disliked. Much tion and the Actual Result

more so than the 1980 Reagan-Carter election, the only race

for which we have polls showing the candidates with rela-

Model Description Prediction Difference Probability

tively high “unfavorable” ratings. And the campaigns appar- (Clinton

ently pursued very different paths, both with respect to their 51.1%)

preferred modes of outreach as well as with respect to their Abramo- Presidential Trump 51.4% Trump over- 0.66 for

minimum winning coalitions. To be sure, this claim has little witz approval, GDP stated by Trump

growth, incum- +2.5

solid empirical backing at this point, but it certainly com- bency

ports with an anecdotal review of the journalistic accounts Lewis-Beck President’s Clinton 51.1% Exactly cor- 0.83 for Clin-

of the election. & Tien popularity, eco- rect ton

nomic growth,

Thus, 2016 offers us an interesting case. Contrary to job creation,

studies of local (Gerber and Green 2004), gubernatorial incumbency

(Carsey 2000, Leal 2006), and congressional elections Fair Per capita GDP, Trump 56.0% Trump over- No probabi-

(Jacobson 1978), many studies of presidential elections show incumbency, stated by lity offered

party’s time in +7.1

that campaigns are epiphenomenal. Most academics believe office, and infla-

that campaigns have only minor effects on the outcome of tion.

presidential elections, particularly compared to circumstan- Lockerbie Polling asking Clinton 50.4% Trump over- 0.62 for Clin-

people if they stated by ton

tial factors such as the economy or whether or not the coun-

expect to be bet- +0.7

try is at war (see, for example, Campbell 2001, Holbrook ter off financially

1996, Sides and Vavreck 2013). But this perspective is in a year or not,

as well as the

premised on the fact that presidential campaigns tend to party’s length of

“cancel each other out” by campaigning in the same way, at time in the

the same level, in the same places (Gelman and King 1993). White House.

This is the critical theoretical point for the larger debate on

campaign effects: voters can be moved—either to vote or to

vote a certain way—but this movement is entirely pre-

ZPB 1/2016 17

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Aufsatz | Shaw – Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election

Model Description Prediction Difference Probability appearances (fundraising events are excluded from the

(Clinton

count), so that a candidate could be credited with multiple

51.1%)

visits in a single state on a particular day. Data are presented

Wlezien & National horse Clinton 52.0% Clinton over- 0.75 for Clin-

Erikson race polling but stated by ton for both presidential and vice-presidential candidates.

also an index +0.9 For the ground game, I rely on the number of field offices in

measuring "lea-

ding economic each state.8 Data reflect offices open as of Oct. 4, 2016. Offices

indicators." are included only if they had verifiable addresses: I do not rely

Norpoth & New Hampshire Trump 52.5% Trump over- 0.87 for on the aggregate numbers claimed by either campaign. As

Bed- primary results stated by Trump such, these totals may undercount offices. Republican

narczuk as a gauge of +3.6

party unity, National Committee offices, “Victory” or “Victory 365”

along with the offices run through the coordinated campaign, or locatable

party’s perfor-

mance in the

county offices in battleground states were considered Trump

past two elec- offices. Trump’s website listed office locations in only six

tions. states. Information on other states was gathered from those

Campbell Clinton 51.5% Clinton over- No probabi- state party websites, county party Facebook pages, and the

stated by lity offered

+0.4

website p2016.org. Office openings mentioned in news reports

were included when addresses could be located, and state

Analytically, then, the unit of analysis I am interested is the party headquarters were excluded unless specifically listed as a

state. Statewide results determine electors to the Electoral Trump office. To locate Clinton’s offices, we used the “Find

College, and are therefore the most fundamental unit of ana- your closest field office” feature on her campaign website.

lysis. But how can I best gauge the uniqueness of 2016? My In addition to these campaign variables, I include mea-

method is simple: I calculate the average Republican share of sures capturing several other factors that might have pro-

the two-party presidential vote for the four elections from duced a unique result in 2016. Perhaps most importantly, I

2000 to 2012; I then calculate the average; and I then sub- employ a measure of the percent of “white” voters in a state.

tract this from Trump’s share of the two-party presidential The underlying idea is that Trump may have done better

vote in 2016. This produces an estimate of how the 2016 than the average Republican candidate by crafting an appeal

vote differed from the “average” recent vote in the state. I that was particularly resonant with white (and even more

use averages because a given election—for example, 2012— particularly, lower status white) voters. Given the impor-

might produce outlying results for specific states. Further- tance of the economy in voters’ political evaluations, I also

more, these four elections—one solid Democratic win rely on a measure of per capita change in gross domestic

(2008), one close Republican win (2004), one close Demo- product (GDP) from 2010 to 2013 (the most recent period

cratic win (2012), and one “tie” (2000)—nicely represent for which statewide data are available) for each state.9 My

the range of possible results given the contemporary party expectation is that states with poorer economies are more

system.5 likely to move away from the incumbent party. Finally, I rely

With this estimate of deviation from average as the main on a measure of percentage point change in the state popula-

descriptive/dependent variable, I can turn to developing a tion. Presumably, states with dynamic populations are more

model of this deviation (“uniqueness”). I am, of course, likely to exhibit dynamic voting patterns.

interested in assessing the degree to which the campaign

explains uniqueness, so I need measures of distinct forms of Results

campaigning at the state-level. Three forms of campaigning

are most prominent in the literature: (1) television advertis- Figure 1A displays the difference between the average

ing, (2) candidate appearances, and (3) the ground game. Republican presidential share of the two-party vote and

For television advertising, I rely on estimates of dollars spent

by the campaigns and party committees over the course of 5 Including the Clinton elections of 1992 and/or 1996 not only stretches

the time-frame backwards quite a bit, but also introduces the com-

the general election campaign in each state.6 These rely on plexity of a southern Democrat running in elections with a strong

Bloomberg News’s analysis of Kantar Media/CMAG data.7 third party candidate.

Only TV advertising is examined here: broadcast, cable, and 6 For all analyses, the general election is defined as Labor Day (Septem-

ber 5, 2016) through Election Day (November 8, 2016). The use of dol-

satellite. Moreover, only spending by the two major party lars spent instead of total airings is debatable. I have run the data

campaigns was included. Since media markets often overlap using each of these measures and find no substantive differences.

more than one state, it is important to observe that each 7 Estimates from Oct. 21-Nov. 7 are from Ad Age's analysis of Kantar

Media/CMAG data.

media market where the campaigns are advertising was 8 I do not include measures of digital outreach as part of my ground

assigned to the battleground state it’s being used to target. game measure. This is mostly a practical decision, as I do not have

relevant data on digital spending at the state-level for 2016 (or any

For candidate appearances, I rely on data from “Travel other election, for that matter). Because of this, I may underestimate

Tracker,” a data analytic tool on the website of The the effects of GOTV efforts, especially for Trump, who invested heav-

National Journal. These estimates were verified by inspec- ily in digital mobilization efforts.

9 The Census Bureau has preliminary data on per capita income for

tions of the daily offerings of The New York Times and the 2016; running these data as the main economic variable does not

campaigns’ websites. “Appearances” are defined as public change the main findings.

18 ZPB 1/2016

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election – Shaw | Aufsatz

Trump’s vote for each of the fifty states plus the District of

Columbia. Bars below the center line indicate that Trump

“under-achieved,” while bars above the line indicate that

Trump “over-achieved. As one can see, Trump over-achieved

in a majority of states (32, to be exact), occasionally doing

so spectacularly. In West Virginia, for example, his share of

the two-party vote was +0.15 over the average, which means

his margin over Clinton was almost 30 points greater than

“expected” in a typical race! Conversely, Trump under-

achieves most dramatically in three states: Utah (where mul-

tiple independent candidacies undoubtedly hurt him), Cali-

fornia, and Texas. Much has been written about Clinton

“running up the score” in California, which helped her win Notes: Calculations are based on the Republican share of the two-party

vote. Thus, for 2016 Trump's share of the two-party vote is divided by

the national vote but did little to further her prospects of

Trump's + Clinton's share of the two-party vote. The same is done for

winning the Electoral College. Relatively little has been said, 2000 through 2012, with the average result serving as the comparison

however, about how Trump’s poor showing in Texas under- point. Negative numbers therefore represent Trump "under-achieving"

cut his popular vote total. compared to Bush, McCain, and Romney, while positive numbers repre-

sent Trump "over-achieving."

The GOP-standard bearer was not well-received in all swing

states. There were four battleground states where he under-

achieved, Virginia, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico.

The last three of these are in the Rocky Mountain west,

where growing millennial and Latino populations were

undoubtedly a factor. Fortunately for Trump, while his

losses in Virginia and Colorado took traditional battle-

ground states out of play, he was able to hold onto Arizona.

There is, in short, considerable evidence that Trump

changed the electoral map: he ceded some ground, especially

in the Rocky Mountain west, in exchange for gaining

ground in the upper Midwest and Mid-Atlantic states. The

exchange was extremely beneficial to the Republican Party,

however, as it cost Trump only Colorado and Virginia (no

sure bet for any Republican candidate these days), while

Figure 1B presents the same measure but only for the battle- securing him Ohio and Iowa and gaining him Michigan,

ground states of 2016. This gives us a better sense of how Pennsylvania, and Michigan. In this sense, 2016 was quite

Trump was able to garner more electoral votes than Bush, different from the preceding four (or even six) presidential

McCain, or Romney. Trump bests the average Republican elections. But how can we best explain these changes?

share of the presidential vote in Iowa by almost 0.07 points, A number of journalists and practitioners credited

which translates into a 14-point improvement in his margin. Trump’s performance in states such as Wisconsin and Michi-

This turned a swing state into a slam-dunk for the Republi- gan to his campaign choices. More to the point, they

can nominee. In Ohio, Michigan, and Maine, Trump beat believed that Trump spent time and money in these states

the average by 0.05 points; again, this translates into a 10- whereas Clinton took them for granted. In this way, the

point improvement in the margin, which was enough to turn results reflected unbalanced or asymmetrical campaigning.

a swing state (Ohio) into a run-away, enough to turn a state In Figures 2A-C, I show the relative campaign made by

Obama carried by double-digits (Michigan) into a GOP win, Trump and Clinton across three forms of outreach: televi-

and enough carry away one electoral vote from a state sion advertising, candidate appearances, and field offices.

(Maine) that hadn’t yielded anything to the Republicans The data are in some ways supportive—but in other ways at

since 1988. In the critical states of Pennsylvania and Wis- odds—with the conventional wisdom about the campaign.

consin, Trump improved upon the Republican average by In Figure 2A, we see that news media reports about Clin-

approximately 3 points (6 points in the margin), which ton’s substantial advantage were mostly justified. Between

flipped states the Democrats had carried six straight times September 5 and November 7, Clinton outspent Trump on

into the GOP column. Trump also scored better than aver- broadcast and cable television advertising by $148 million to

age in Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Nevada (where he $93 million, a ratio of better than 3:2. This advantage varied

lost narrowly), as well as Florida (where he won). considerably state-by-state, though, and in many states

Trump had a substantial commercial presence despite being

significantly outspent by Clinton (see Florida, North Car-

olina, Ohio, Nevada, and Pennsylvania). Despite Clinton’s

ZPB 1/2016 19

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Aufsatz | Shaw – Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election

general dominance, Trump did spent more heavily in three

states: Colorado, Virginia, and Wisconsin. He also had a

slight advantage in Michigan, where his small TV ad buy

totals eclipsed Clinton’s. Still, the distribution of TV ad

spending across the states suggests that Clinton ought to

have done better than predicted and that other factors were

probably more central to explaining Trump’s success.

Beyond TV ads and candidate appearances, presidential

campaigns are also about the ground game. There are, of

course, many ways to conceptualize the ground game but

the most obvious is to simply tally the field offices main-

tained by the respective campaigns. Figure 2C displays the

field offices established in each state by the Trump and Clin-

ton campaigns. Here, as with TV ad spending, we see a sig-

nificant edge for Clinton. Overall, as of October 4, 2016,

Another aspect of the campaign is personal appearances. Clinton had 489 field offices compared to 207 for Trump. In

There is an old saying amongst consultants that says the two Ohio, he had 75 to his 22; in Pennsylvania, she had 57 to his

most valuable resources in any campaign are the candidate’s 42; in Florida, she had 68 to his 29. Even in Wisconsin and

time and the candidate’s money. If TV advertising is the best Michigan, she had field office advantages of +7 and +21,

functional expression of a campaign’s money, then candidate respectively.

appearances are the best functional expression of the candi-

date’s time. Figure 2B shows where the presidential and vice-

presidential candidates allocated their visits between Septem-

ber 5 and Election Day. Whereas Clinton and the Democrats

dominated with respect to TV ads, Trump and the Republicans

dominated with respect to candidate appearances. Trump

racked up 109 public appearances over this nine week period,

compared to 65 for Clinton. Pence also managed slightly more

visits than Kaine, 70 to 64. Perhaps more tellingly, Trump was

much more active than Clinton in Florida, North Carolina,

Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. But Clinton did

make multiple appearances in each of those states, except for

Wisconsin. Furthermore, Trump also made many more

appearances than Clinton in New Hampshire, Colorado, and

Virginia but lost all three of those states, receiving below aver-

age vote percentages in the latter two.

Interestingly, the popular notion that the Democrats

Notes: Data reflect offices open as of Oct. 4, 2016. Offices are included

ignored the “blue wall” states of the upper Midwest is not

only if they had verifiable addresses: I do not rely on the aggregate num-

entirely corroborated by these data. When it comes to hit- bers claimed by either campaign. As such, these totals may undercount

ting the campaign trail, Clinton was extremely active in offices. Republican National Committee offices, “Victory” or “Victory 365”

Pennsylvania and somewhat active in Michigan. The more offices run through the coordinated campaign, or locatable county offices

in battleground states were considered Trump offices. Trump’s website lis-

accurate interpretation is that the vice-presidential nominee

ted office locations in only six states. Information on other states was

and surrogates were the primary weapon of choice for states gathered from those state party websites, county party Facebook pages,

that were seen as needing only a little bit of maintenance. and the website p2016.org. Office openings mentioned in news reports

Kaine made appearances in Minnesota and Wisconsin, while were included when addresses could be located, and state party head-

quarters were excluded unless specifically listed as a Trump office. To

the Obamas were dispatched to Michigan a couple of days

locate Clinton’s offices, we used the “Find your closest field office” feature

before the election. on her campaign website.

20 ZPB 1/2016

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election – Shaw | Aufsatz

Officials from the Trump campaign have argued that field forms reasonably well, registering well above conventional

offices do not accurately reflect their activity on the ground. levels of statistical significance (the F-Statistic is significant at

They emphasize that the “bricks and mortar” offices are the 0.001 level) and correctly predicting about 13 percent of

expensive and unnecessary in an age of digital communica- the total variance in Trump’s performance across the 51 rele-

tion and outreach. Brad Parscale, Digital Communications vant jurisdictions.

Director for Trump, stated Trump spent over $100 million

on his digital campaign, achieving a 1:1 ratio with TV ad Table 3. Modeling the 2016 Presidential Vote

spending.10 He also stated that the campaign spent $5 mil-

lion on digital efforts to “get-out-the-vote” in Florida,

Predicting Trump performance compa- Regression Stan- Signifi-

Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin over the final few red to 2000-16 Rep. presidential aver- Coefficient dard cance

days.11 News media estimates based on Federal Election age Error

(share of the two-party vote)

Commission reports back the notion that Trump invested

TV dollars spent by Clinton-Kaine -0.010 (0.007) 0.175

more than Clinton on digital outreach, pegging Trump’s dig-

(in millions)

ital spending during the final nine weeks of the general elec-

TV dollars spend by Trump-Pence 0.010 (0.009) 0.286

tion campaign at $29 million, compared to $16 million for (in millions)

Clinton.12 Clinton appearances 0.030 (0.014) 0.041

But a closer look at Trump’s digital spending indicates Trump appearances -0.011 (0.008) 0.167

that some appreciable portion of his overall spending on dig- Kaine appearances 0.008 (0.009) 0.389

ital campaigning was dedicated to fundraising rather than Pence appearances -0.013 (0.007) 0.081

GOTV. Moreover, even conceding that Trump engaged in Trump-Pence/RNC field offices -0.002 (0.002) 0.394

more digitally-based outreach—a major and contentious

Clinton-Kaine/DNC office 0.000 (0.001) 0.742

concession—it seems unlikely that his ground game was

% white in state 0.001 (0.001) 0.010

markedly better than Clinton in many states. Indeed, while

Population change -0.023 (0.015) 0.117

we are now skeptical of the conventional wisdom that Clin-

Per capita GDP change 0.006 (0.005) 0.195

ton had a massive edge with respect to the ground game

given the election itself and the arguments of insiders like Constant -0.088 (0.043) 0.047

Parscale, it is difficult to reject the prevailing assumption of N 51

Clinton’s superiority (given the data at hand). Adjusted R-Square 0.128

The distributions of different types of campaigning are Standard Error of Estimate 0.042

instructive, of course, but only to a point. Election scholars

The campaign variables produce mixed results. The regres-

correctly observe that campaigns tend to concentrate their

sion coefficients associated with television ad spending, for

efforts on voters and in locations where they think they can

example, are correctly signed (additional Trump spending

be effective, creating a “chicken-and-egg” dilemma: did vot-

increases his performance compared to average, while addi-

ers move in response to the campaign or would they have

tional Clinton spending decreases it). But the substantive

moved on their own anyway, as they became more engaged

effects are somewhat pedestrian; holding all other factors

with the race and connected the choice at hand with what is

constant, a $1 million increase in Trump’s TV ad spending

going on in the country and in their own lives? Then there is

improves his showing compared to average by about 1

also the difficulty of teasing out the effects of different types

point. Moreover, one cannot really rule out the possibility

of campaigning that are aimed at the same voters and states.

that this effect is a function of statistical noise. The same is

Was it TV advertising or the candidates’ appearances that

true—in the opposite direction—for Clinton’s TV spending,

was most directly connected with shifts in preferences? Table

although we are slightly more confident that the influence of

3 offers a model of the uniqueness of Trump’s vote across

Clinton’s TV is not due to statistical noise.

the states while controlling for different campaign efforts as

The story is different (and fascinating) for candidate

well as a set of objective circumstances and conditions.

appearances. Notice that the sign for the candidate travel

The simple model I am testing uses a least squares esti- coefficients are all in the opposite direction from what one

mator to ascertain the independent effects of TV advertising would expect. In other words, Trump’s and Pence’s appear-

(measured in millions of dollars), presidential and vice-presi- ances were associated with a decrease in Republican perfor-

dential candidate appearances, and field offices. The control mance compared to average, whereas Clinton’s and Kaine’s

variables include (1) percent white in the state, (2) 2010-13

percent population change within the state, and (3) 2010-13 10 “Campaign for President: The Managers Look at 2016,” Harvard Uni-

change in per capita GDP. Again, the dependent variable is versity Conference, November 30-December 1, 2016.

the difference between Trump’s 2016 share of the two-party 11 “Trump spent almost $40 million less than Clinton in Campaign’s

Final Weeks,” Associated Press, December 9, 2016. http://

vote and the average share of the two-party vote won by www.foxnews.com/politics/2016/12/09/trump-spent-almost-40-

Republican candidates in elections from 2000-12. This num- million-less-than-clinton-in-campaigns-final-weeks.html.

ber varies between +1.0 and -1.0, with positive numbers 12 “Trump spent almost $40 million less than Clinton in Campaign’s

Final Weeks,” Associated Press, December 9, 2016. http://

(and coefficients) indicating a “better” performance for www.foxnews.com/politics/2016/12/09/trump-spent-almost-40-

Trump compared to “expected.” Overall, the model per- million-less-than-clinton-in-campaigns-final-weeks.html.

ZPB 1/2016 21

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Aufsatz | Shaw – Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election

appearances were associated with an increase. For Clinton’s of 11.9 percent between 2010 and 13 due to the energy

appearances, the effect was substantial: each additional Clin- boom and was also quite friendly towards Trump, who had

ton appearance boosted Trump’s performance versus aver- pledged to un-do President Obama’s restrictions and regula-

age by 3 points. There is only a four in one hundred chance tions on fracking and other natural gas exploration tech-

that the estimated effect is due to statistical noise. The niques. If I omit South Dakota from the analysis, the sign on

remaining candidates produced a smaller effect—about a the economic variable reverses (conforming to my original

one-point shift in the wrong direction. expectations) but is insignificant statistically.

Despite the fact that these travel effects are statistically

marginal, it is tempting to take them at face value. The pres- Conclusion

idential candidates were the least well-liked in recent Ameri-

can history, and it is not implausible that they would pro- An exploration of state-level data from the 2016 presidential

duce a backlash when they stumped in a given state. Backing election provides solid empirical support for the argument

this interpretation is that neither candidate received favor- that Donald Trump’s vote represents an important departure

able new media coverage during the campaign, such that from the previous four elections. While the 2000-12 elec-

local scrutiny might have actually highlighted the fact that tions produced only ten states13 with a split voting record, in

the candidates were (at least in the minds of voters) flawed. 2016 we saw three states (Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wis-

Our final measure of the campaign—field offices—had consin) representing 46 electoral votes flip for the first time

almost no explanatory power with respect to Trump’s per- since 1988. We also saw Trump nearly carry reliably-Demo-

formance compared to average. Indeed, the relevant coeffi- cratic Minnesota and Maine, while the Democrats had near

cients for Trump’s and Clinton’s field offices are essentially misses in Arizona and Georgia. The coalitional basis for this

zero; as in, opening an additional field office in a state does shift has become a staple of journalistic explanations for

nothing to increase (for Trump) or decrease (for Clinton) 2016—white, lower socio-economic status voters defected

Trump’s vote. Given the plethora of recent research demon- from the Democrats, while younger, more racially diverse

strating the positive effects of face-to-face outreach in a wide voters continued (albeit it at sluggish rates) to favor the

range of campaigns, I am even more open than I usually Democrats over the Republicans. Prior to November 8,

would be to the argument that field offices are too blunt a 2016, almost all of the conversation about party system

measure to get at the impact of this form of outreach. Per- dynamics focused on the rise of Democratic fortunes due to

haps volunteers or contacts, which may become available in the mobilization of ascendant elements of the country; after

the aftermath of 2016, will provide a more instructive mea- the 2016 election, it has become clear that this ascendance

sure. Or perhaps it is the case that the fundamentals are may be problematic if the Democrats lose their traditional

driving voters in a presidential race in a way that they do white, working class edge.

not in down-ballot races. If 2016 thus represents a path-breaking election for stu-

dents of voting and party systems, it is no less challenging

Meanwhile, Table 3 suggests that the fundamentals were,

for students of campaigns. The data on traditional modes of

in fact, an important part of the story for 2016. Most

campaigning suggest that Hillary Clinton had the edge. She

notably, the percent of white voters in a state is a statistically

certainly did more on television and with field offices.

significant predictor of Trump’s relative performance. To

Trump and Pence were more active on the campaign trail

cast the effect in more interpretable terms, for every ten per-

than Clinton and Kaine, but the data indicate that this might

cent increase in the white population Trump gets an addi-

not have necessarily been a good thing, given how unpopu-

tional percentage point compared to the average Republican

lar the candidates were and how negative the news media

presidential candidate. Put another way, all other things held

were in covering them. At any rate, there is scant evidence

constant Trump would do 3 points better than Bush/

that Trump’s over-performance was the result of an espe-

McCain/Romney in a state like Iowa (93% white) compared

cially effective campaign.

to a state like Georgia (63% white). The model also shows

that states with more dynamic populations were less gener- This result is disappointing in some regards. As men-

ous to Trump than towards the average GOP candidate, tioned earlier, studies of presidential campaigns are usually

although the effect isn’t very large and is only marginally limited because both sides target the same states with maxi-

significant statistically. mal resources, such that neither side is likely to gain an

advantage. But in 2016, there were several states where one

What about the economy? I use change in per capita

side or the other had a substantial edge on at least one form

state GDP to measure the effect of the economy on Trump’s

of campaigning. Partly, this reflected an asymmetry in

showing, and the data are positive if not overwhelming. A 5-

resources, with Clinton having much more money and labor

point increase in per capita GDP increases Trump’s voter

than Trump. Partly, it reflected a difference in views of the

compared to average by about 3 points. This is inconsistent

battlefield. Trump saw the “blue wall” states of Wisconsin,

with my expectation that states that are experiencing more

Michigan, and Pennsylvania as true battleground states,

difficult economic times would be more likely to throw their

support to Trump. But a closer examination of the data

13 Nevada, Colorado, Iowa, Ohio, Florida, Virginia, New Hampshire, and

reveals the cause of this anomaly: South Dakota. The Mount North Carolina, and as well as New Mexico and Indiana (which were

Rushmore State experienced an increase in per capita GDP widely regarded as single election flukes).

22 ZPB 1/2016

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Assessing the Impact of Campaigning in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election – Shaw | Aufsatz

whereas (with the exception of Pennsylvania) Clinton saw Holbrook, Thomas. 1996. Do Campaigns Matter? Beverley Hills, CA:

Sage Publishing.

them as leaning strongly to her side. Conversely, Trump saw

Jacobson, Gary C. 1978. “The Effects of Campaign Spending in Con-

reliably Republican states such as Arizona, Georgia, Utah,

gressional Elections.” American Political Science Review, Vol. 72, Issue

and Texas as strongly leaning to him, while Clinton saw Ari- 4: 469-491.

zona (at least) as a true battleground. At any rate, I had pre- Leal, David. 2006. Electing America’s Governors: The Politics of Execu-

sumed that these strategic differences and the resource asym- tive Elections. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

metries would combine to produce the potential for substan- Sides, John and Lynn Vavreck, 2013. The Gamble: Choice and Chance

tive campaign effects. Those did not materialize, not in these in the 2012 Presidential Election. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

data at least.

Two take-away points are worth offering. First, I am Professor Daron Shaw received his

prone to believe that TV advertising simply does not move B.A. and Ph.D. degrees from the

voters much in presidential elections anymore. Early adver- University of California, Los Ange-

tising, in a race where the candidates are not as well-known, les before joining the faculty at the

might well produce effects. But by the fall of an election University of Texas at Austin in the

between two well-known candidates? Not so much. In the fall of 1994. In addition to his work

future, it seems likely that candidates will lay down a mod- at UT, he worked as a survey

est layer of television advertising, just to shore up their research analyst and targeting con-

images and prevent negative media coverage, and then spend sultant in the presidential cam-

their money on personalized and digitally-based outreach. paigns of 1992, 2000, and 2004. He

Second, I suspect that the measures of campaigning I am is currently a member of the Fox

employing here are too blunt to show the fine-grained effects News Decision Team, the National

more likely to be associated with modern presidential cam- Election Study’s board of overseers,

paigning. If I could isolate campaigning by the media market and the Annette Strauss Institute’s

or zip code, my guess is that there are pockets of the country advisory board. Professor Shaw is

where campaigning mattered. Or if my measures of cam- the co-director of the Fox News

paigning—especially digital contacting and face-to-face out- Poll, director of the Texas Lyceum

reach—were more specific, I suspect the results might also be Poll, and co-director of the Univer-

different. These sorts of data will likely be available in the sity of Texas Government Depart-

future and certainly merit exploration. ment-Texas Tribune Poll. He has

I should also point out that campaigning here is defined also been a research fellow for the

as the strategic choices and dispensation of resources associ- Hoover Institution, a presidential

ated with the 2016 presidential contest. While debates, scan- appointee to the National Histori-

dals, and gaffes absolutely fall under any reasonable defini- cal Publications and Records Com-

tion of the campaign, I do not consider them here and any mission, a research consultant for

conclusions about the campaign exclude these events. the Presidential Committee on

But the bottom-line is still unavoidable: 2016 was a dif- Election Administration, a board

ferent election than we might have expected given its prede- member for the Pew Elections Ini-

cessors, and this was almost certainly due to the combina- tiative, and a consultant for the

tion of shifts in the mood of the electorate along with the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute.

presence of two candidates with formidable skills and an

array of baggage. Throw in the always difficult to measure

variable of news media coverage, and you have the recipe

for 2016. The campaigns, which might have been a critical

variable in such a circumstance, were ultimately over-

whelmed by candidate, voter, and media dynamics.

References

Campbell, James. 2008. The American Campaign: U.S. Presidential

Campaigns and the National Vote (2nd edition). College Station, TX:

Texas A & M Press).

Carsey, Thomas M. 2000. Campaign Dynamics: The Race for Gover-

nor. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Gelman, Andrew and Gary King. 1993. “Why are American Presiden-

tial Election Campaigns so Variable when Votes are so Predictable?”

British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 23, Issue 4: 409-451.

Gerber, Alan S. and Donald P. Green. 2004. Get Out the Vote! How to

Increase Voter Turnout. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

ZPB 1/2016 23

This content downloaded from

88.230.101.210 on Thu, 06 Apr 2023 23:48:12 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Introduction To Genetic Analysis 11th Edition Griffiths Solutions ManualDocument7 pagesIntroduction To Genetic Analysis 11th Edition Griffiths Solutions Manualdizewyzi0% (4)

- Elementary Statistics 2nd Edition Solutions Manual Navidi MonkDocument14 pagesElementary Statistics 2nd Edition Solutions Manual Navidi MonkxufaduxatoNo ratings yet

- Complaint For DefamationDocument17 pagesComplaint For DefamationjoshmclaurinNo ratings yet

- Miskito DictionaryDocument26 pagesMiskito DictionarycarlamadorNo ratings yet

- The 2016 Presidential Election-An Abundance of ControversiesDocument20 pagesThe 2016 Presidential Election-An Abundance of ControversiesHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- The 2016 Presidential Election-Identities, Class, and CultureDocument20 pagesThe 2016 Presidential Election-Identities, Class, and CultureHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- U.S. Congress, Presidency and The Courts The Presidential Election Process September 17, 2019Document37 pagesU.S. Congress, Presidency and The Courts The Presidential Election Process September 17, 2019Zachary WatsonNo ratings yet

- Summary of In Trump We Trust: by Ann Coulter | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of In Trump We Trust: by Ann Coulter | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Half-Time!: American public opinion midway through Trump's (first?) term – and the race to 2020From EverandHalf-Time!: American public opinion midway through Trump's (first?) term – and the race to 2020No ratings yet

- Προεδρικές 2024: Η προεγλογική εκστρατεία στις ΗΠΑDocument9 pagesΠροεδρικές 2024: Η προεγλογική εκστρατεία στις ΗΠΑARISTEIDIS VIKETOSNo ratings yet

- The 2016 US Presidential Campaign Political Communication and Practice by Robert E. Denton JR (Eds.)Document342 pagesThe 2016 US Presidential Campaign Political Communication and Practice by Robert E. Denton JR (Eds.)Eirini SotiropoulouNo ratings yet

- Reunited Nation?: American politics beyond the 2020 electionFrom EverandReunited Nation?: American politics beyond the 2020 electionNo ratings yet

- How to Beat Trump: America's Top Political Strategists on What It Will TakeFrom EverandHow to Beat Trump: America's Top Political Strategists on What It Will TakeNo ratings yet

- WWW Vox Com Policy and Politics 2017 10-5-16414338 Trump DemDocument12 pagesWWW Vox Com Policy and Politics 2017 10-5-16414338 Trump DemLeon BerishaNo ratings yet

- Why These Obama Voters Are Backing Donald Trump: Sizable Lead For TrumpDocument4 pagesWhy These Obama Voters Are Backing Donald Trump: Sizable Lead For TrumpBruno SilvaNo ratings yet

- Who Decides When The Party Doesn't? Authoritarian Voters and The Rise of Donald TrumpDocument6 pagesWho Decides When The Party Doesn't? Authoritarian Voters and The Rise of Donald TrumpRichNo ratings yet

- National Party Conventions in US PoliticsDocument4 pagesNational Party Conventions in US PoliticsGeorgia WowkNo ratings yet

- Business Statistics Canadian 3rd Edition Sharpe Solutions ManualDocument9 pagesBusiness Statistics Canadian 3rd Edition Sharpe Solutions ManuallelyhaNo ratings yet

- The Long Slog: A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The White HouseFrom EverandThe Long Slog: A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The White HouseNo ratings yet

- Concours Blanc Anglais VDSDocument2 pagesConcours Blanc Anglais VDSFrederique MenantNo ratings yet

- Kansas Thomas Snow Neg Emporia Round6Document41 pagesKansas Thomas Snow Neg Emporia Round6Sebastina GlosNo ratings yet

- 2016 Presidential ElectionDocument8 pages2016 Presidential ElectionKeegan HonasNo ratings yet

- Do We Have A Center?: 2016, 2020, and the Challenge of the Trump PresidencyFrom EverandDo We Have A Center?: 2016, 2020, and the Challenge of the Trump PresidencyNo ratings yet

- 5 With Debate Deal, Trump and Biden Sideline A Storied Campaign InstitutionDocument5 pages5 With Debate Deal, Trump and Biden Sideline A Storied Campaign InstitutionGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- USA 2025: How Republicans Could Take Over and Transform AmericaFrom EverandUSA 2025: How Republicans Could Take Over and Transform AmericaNo ratings yet

- Elections DA - 2016Document227 pagesElections DA - 2016Anonymous cGMk7iWNbNo ratings yet

- Charles E. Cook Jr. 2000. Polls and Models Which Numbers To Believe The Washington Quarterly (Autumn 2000) Volume 23 Number 4 Pp. 195-202Document8 pagesCharles E. Cook Jr. 2000. Polls and Models Which Numbers To Believe The Washington Quarterly (Autumn 2000) Volume 23 Number 4 Pp. 195-202Wu GuifengNo ratings yet

- Donald Trump and The Republican Party: The Making of A Faustian BargainDocument13 pagesDonald Trump and The Republican Party: The Making of A Faustian BargainKAMNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide To The Race For The White House - US News - The GuardianDocument7 pagesA Simple Guide To The Race For The White House - US News - The GuardianSeemantiniGuptaNo ratings yet

- ElectionnotebookDocument6 pagesElectionnotebookapi-329384437No ratings yet

- Annotated BibDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibapi-316486998No ratings yet

- Empire Strikes BackDocument6 pagesEmpire Strikes BackBanwa GrassNo ratings yet

- Presidential Elections in The USDocument2 pagesPresidential Elections in The USStefan RomanskiNo ratings yet

- Packer MemoDocument3 pagesPacker MemoElliotNo ratings yet

- 1 Donald Trump Coasts To Victory in The Iowa Republican CaucusesDocument2 pages1 Donald Trump Coasts To Victory in The Iowa Republican CaucusesGistha WicitaNo ratings yet

- One Vote Away: How a Single Supreme Court Seat Can Change HistoryFrom EverandOne Vote Away: How a Single Supreme Court Seat Can Change HistoryRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (24)

- MAGA Inc Ad Verification 5/24/2023Document14 pagesMAGA Inc Ad Verification 5/24/2023Elias AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Current National Polling: October 4, 2016Document10 pagesCurrent National Polling: October 4, 2016NoFilter PoliticsNo ratings yet

- National Poll (October 4, 2016) v3Document10 pagesNational Poll (October 4, 2016) v3Breitbart NewsNo ratings yet

- Report On Donald TrumpDocument12 pagesReport On Donald TrumpAyaz Aslam100% (1)

- What Is Causing Donald Trumps Rise To Political Stardom - Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesWhat Is Causing Donald Trumps Rise To Political Stardom - Annotated BibliographySpencer Smith0% (1)

- Updates - 2020Document63 pagesUpdates - 2020vegSpamNo ratings yet

- 2016 Election and Beyond: What Did You Know? What You Need to Know: Educator’S PerspectiveFrom Everand2016 Election and Beyond: What Did You Know? What You Need to Know: Educator’S PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- Transition To: Trump Presidency BeginsDocument32 pagesTransition To: Trump Presidency BeginsThesouthasian TimesNo ratings yet

- History Says Bloomberg 2020 Would Be A Sure Loser - POLITICO MagazineDocument4 pagesHistory Says Bloomberg 2020 Would Be A Sure Loser - POLITICO MagazineifraNo ratings yet

- Transition Integrity Project: Background Concerns About The Legitimacy of The 2020 Presidential ElectionDocument7 pagesTransition Integrity Project: Background Concerns About The Legitimacy of The 2020 Presidential ElectionFred JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Hopes and Fears: Trump, Clinton, the voters and the futureFrom EverandHopes and Fears: Trump, Clinton, the voters and the futureNo ratings yet

- 149-Texto Do Artigo-335-1-10-20191210Document14 pages149-Texto Do Artigo-335-1-10-20191210Lorena RosaNo ratings yet

- US Presidential Election1Document4 pagesUS Presidential Election1Ziauddin ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Summary of Tired of Winning by Jonathan Karl: Donald Trump and the End of the Grand Old PartyFrom EverandSummary of Tired of Winning by Jonathan Karl: Donald Trump and the End of the Grand Old PartyNo ratings yet

- PresidentialqualitiesDocument5 pagesPresidentialqualitiesapi-313523039No ratings yet

- Democrats Will Hold On To The Senate-Money, History, and Voter Targeting and Turnout Favor The Democrat IncumbentsDocument5 pagesDemocrats Will Hold On To The Senate-Money, History, and Voter Targeting and Turnout Favor The Democrat Incumbentskellybye10No ratings yet

- How The News Media Helped To Nominate TrumpDocument5 pagesHow The News Media Helped To Nominate TrumpMariane NavaNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument5 pagesReportapi-312104079No ratings yet

- Jour 3796 PaperDocument9 pagesJour 3796 Paperapi-314087580No ratings yet

- Current Oregon Polling: October 7, 2016Document8 pagesCurrent Oregon Polling: October 7, 2016NoFilter PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Upload 1Document10 pagesUpload 1Naz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Trump vs. Hillary: What Went Viral During The 2016 US Presidential ElectionDocument19 pagesTrump vs. Hillary: What Went Viral During The 2016 US Presidential ElectionNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Changing Norms Following The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election: The Trump Effect On PrejudiceDocument7 pagesChanging Norms Following The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election: The Trump Effect On PrejudiceNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Media in Election ProcessesDocument4 pagesMedia in Election ProcessesNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Social Media For Political Campaigns: An Examination of Trump's and Clinton's Frame Building and Its Effect On Audience EngagementDocument13 pagesSocial Media For Political Campaigns: An Examination of Trump's and Clinton's Frame Building and Its Effect On Audience EngagementNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet

- Winning On Social Media: Candidate Social-Mediated Communication and Voting During The 2016 US Presidential ElectionDocument10 pagesWinning On Social Media: Candidate Social-Mediated Communication and Voting During The 2016 US Presidential ElectionNaz Zeynep OrhanNo ratings yet