Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Image

Image

Uploaded by

An LeCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Dental Starting A Practice WorkbookDocument41 pagesDental Starting A Practice WorkbookD.WorkuNo ratings yet

- Sample QuestionsDocument5 pagesSample QuestionsAkash BalgobinNo ratings yet

- Job Order Costing Difficult RoundDocument8 pagesJob Order Costing Difficult RoundsarahbeeNo ratings yet

- Some of The Key Reasons For The Emergence of WTODocument4 pagesSome of The Key Reasons For The Emergence of WTOShilpa ShreeNo ratings yet

- Pitrela Essay - Fresto - TriszkaDocument8 pagesPitrela Essay - Fresto - TriszkaTriszkaNo ratings yet

- Theory of Economic IntegrationDocument39 pagesTheory of Economic IntegrationJustin Lim100% (1)

- What Do Trade Agreements Really DoDocument5 pagesWhat Do Trade Agreements Really DoGagan AnandNo ratings yet

- Gatt, WTO and GlobalizationDocument29 pagesGatt, WTO and GlobalizationGaurav NavaleNo ratings yet

- Economic Integration TheoryDocument39 pagesEconomic Integration Theorycarlosp2015No ratings yet

- Narrative Report - Chapter 10Document4 pagesNarrative Report - Chapter 10Hazel BorboNo ratings yet

- PTA BuildingDocument4 pagesPTA BuildingAnne S. Yen100% (1)

- South Asian Free Trade AgreementDocument44 pagesSouth Asian Free Trade AgreementZeeshan Adeel100% (3)

- The Proliferation of RTA and India PositionDocument11 pagesThe Proliferation of RTA and India PositionDr. Babar Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- 1846 01 WCJ v12n1 AltemoellerDocument10 pages1846 01 WCJ v12n1 AltemoellerGrazelle DomanaisNo ratings yet

- Law and Economics Final DraftDocument10 pagesLaw and Economics Final Draftmayankjuly04No ratings yet

- Final Reaction Paper 1 MFNDocument11 pagesFinal Reaction Paper 1 MFNFazilda NabeelNo ratings yet

- International Trade Theory and Policy 11Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument31 pagesInternational Trade Theory and Policy 11Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFRobinCummingsfikg100% (12)

- REGIONAL TRADE BLOCS PPT IntroductionDocument14 pagesREGIONAL TRADE BLOCS PPT IntroductionAnwar Khan100% (1)

- M09 Krug8283 08 SG C09Document10 pagesM09 Krug8283 08 SG C09Andrés ChacónNo ratings yet

- International Political EconomyDocument8 pagesInternational Political EconomySajida RiazNo ratings yet

- Discuss Whether Regionalism (PTA) Is Helping or Hindering The Achievement of Global Free Trade. BuildingDocument3 pagesDiscuss Whether Regionalism (PTA) Is Helping or Hindering The Achievement of Global Free Trade. BuildingAnne S. YenNo ratings yet

- Gatt and WtoDocument2 pagesGatt and WtoSatya PanduNo ratings yet

- Regional Trade BlocsDocument15 pagesRegional Trade BlocsAnwar KhanNo ratings yet

- International Economics Theory and Policy 11Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument31 pagesInternational Economics Theory and Policy 11Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFPamelaHillqans100% (13)

- Youth in Policymaking and GovernanceDocument2 pagesYouth in Policymaking and GovernanceGodhuliNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1Document23 pagesLecture 1Sadia Islam MimNo ratings yet

- The Basics of Non-Discrimination Principle WTODocument5 pagesThe Basics of Non-Discrimination Principle WTOFirman HamdanNo ratings yet

- Making The Rules 05Document27 pagesMaking The Rules 05gonzalezgalarzaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Trade BlocsDocument5 pagesThe Effects of Trade BlocsKalpesh BhagneNo ratings yet

- Globalization, Trade and Business PDFDocument13 pagesGlobalization, Trade and Business PDFEconomics LabNo ratings yet

- Seattle and Beyond: A WTO Agenda For The New Millennium, Cato Trade Policy Analysis No. 8Document45 pagesSeattle and Beyond: A WTO Agenda For The New Millennium, Cato Trade Policy Analysis No. 8Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Role of WtoDocument7 pagesRole of Wtomuna1990No ratings yet

- Preferential Trade Agreements, Investment Disciplines and Investment FlowsDocument21 pagesPreferential Trade Agreements, Investment Disciplines and Investment FlowsMihaela NicoaraNo ratings yet

- 5article Review Trade - Liberalization - and - GlobalizationDocument10 pages5article Review Trade - Liberalization - and - GlobalizationJamal YusufiNo ratings yet

- What Is Globalisation: Globalisation - Its Benefits and DrawbacksDocument9 pagesWhat Is Globalisation: Globalisation - Its Benefits and Drawbacksbruhaspati1210No ratings yet

- Regional Trade AgreementsDocument4 pagesRegional Trade AgreementsNazsh AnwarNo ratings yet

- GTA Policy BriefDocument8 pagesGTA Policy BriefUdit NarangNo ratings yet

- Internationaltrade 11Document5 pagesInternationaltrade 11Bisrat MekonenNo ratings yet

- Customs Unions and Free Trade AreasDocument6 pagesCustoms Unions and Free Trade AreasÖzer AksoyNo ratings yet

- Multi Layer Regional PactsDocument3 pagesMulti Layer Regional PactsHussain Mohi-ud-Din QadriNo ratings yet

- Wto and Devloping CountriesDocument24 pagesWto and Devloping Countrieskj201992No ratings yet

- Economics Stimulus EssayDocument4 pagesEconomics Stimulus Essaytimberap 27No ratings yet

- Principles of The Trading System: Trade Without DiscriminationDocument5 pagesPrinciples of The Trading System: Trade Without DiscriminationVIJAYADARSHINI VIDJEANNo ratings yet

- Comilla University: Department of MarketingDocument17 pagesComilla University: Department of MarketingMurshid IqbalNo ratings yet

- 2022 How Does Import Market Power Matter For Trade AgreementsDocument20 pages2022 How Does Import Market Power Matter For Trade AgreementsShourya MarwahaNo ratings yet

- Purposes of Regional Trade BlocksDocument7 pagesPurposes of Regional Trade BlocksSukumar ThamilmaniNo ratings yet

- World Trade Organization ProjectDocument42 pagesWorld Trade Organization ProjectNiket Dattani100% (1)

- ECOMACDocument3 pagesECOMACquennieguanco22No ratings yet

- Assignment FinalDocument34 pagesAssignment FinalSaina KennethNo ratings yet

- Understanding The WtoDocument7 pagesUnderstanding The WtoNabinSundar NayakNo ratings yet

- International Trade Polic2 - GATTDocument5 pagesInternational Trade Polic2 - GATTEmmanuel BongayNo ratings yet

- (Cobibcl) Long Quiz 2Document5 pages(Cobibcl) Long Quiz 2Courtney TulioNo ratings yet

- Competition Law and International TradeDocument17 pagesCompetition Law and International Tradevainygoel100% (2)

- 01 Iie 3616Document33 pages01 Iie 3616PaolaNo ratings yet

- ITL Important TopicsDocument11 pagesITL Important TopicsTushar GuptaNo ratings yet

- Dispute Settlement Mechanism and Developing NationsDocument5 pagesDispute Settlement Mechanism and Developing Nationshaseeb ahmedNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of The Levels of Economic IntegrationDocument3 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of The Levels of Economic IntegrationMartha L Pv RNo ratings yet

- Final Copy of Econghghomic ItegrationDocument20 pagesFinal Copy of Econghghomic ItegrationSneha BandarkarNo ratings yet

- An Economic Theory of GATTDocument56 pagesAn Economic Theory of GATTgargargarfieldNo ratings yet

- Most Favoured NationDocument17 pagesMost Favoured Nationrishabhsingh261No ratings yet

- International Trade Subsidy Rules and Tax and Financial Export Incentives: From Limitations on Fiscal Sovereignty to Development-Inducing MechanismsFrom EverandInternational Trade Subsidy Rules and Tax and Financial Export Incentives: From Limitations on Fiscal Sovereignty to Development-Inducing MechanismsNo ratings yet

- ImageDocument1 pageImageAn LeNo ratings yet

- ImageDocument1 pageImageAn LeNo ratings yet

- IRDocument1 pageIRAn LeNo ratings yet

- International RelationsDocument1 pageInternational RelationsAn LeNo ratings yet

- ImageDocument1 pageImageAn LeNo ratings yet

- International EconomicsDocument1 pageInternational EconomicsAn LeNo ratings yet

- PS Enterprise Payroll For North America 9.1Document1,358 pagesPS Enterprise Payroll For North America 9.1ronaldcgreyNo ratings yet

- International Trade and Business ExamDocument2 pagesInternational Trade and Business ExamKristina Jane De CastroNo ratings yet

- Leadership Case: Cool ProductsDocument2 pagesLeadership Case: Cool ProductsRushabh ShahNo ratings yet

- Potato Industry Report 2014 - 2015 Zambia AfricaDocument122 pagesPotato Industry Report 2014 - 2015 Zambia AfricaGRAMYA Pvt Ltd.No ratings yet

- Zakat Self-Assessment: Section 1 - Do You Have To Pay Zakat This Year ?Document3 pagesZakat Self-Assessment: Section 1 - Do You Have To Pay Zakat This Year ?Hasan Irfan SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- The Logistics MarketplaceDocument19 pagesThe Logistics MarketplacePablo UgaldeNo ratings yet

- Askari Bank Schedule of Charges PDFDocument20 pagesAskari Bank Schedule of Charges PDFJHKJHKJHKHJHKNo ratings yet

- Chap 6 HomeworkDocument2 pagesChap 6 HomeworkTaghi MammadovNo ratings yet

- Revealed Preference TheoryDocument5 pagesRevealed Preference TheoryRitu SundraniNo ratings yet

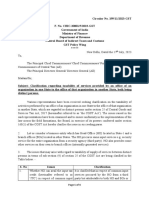

- Circular CGST 199Document4 pagesCircular CGST 199Jaipur-B Gr-2No ratings yet

- الشركات متعددة الجنسيات InaDocument23 pagesالشركات متعددة الجنسيات InamouradNo ratings yet

- Impact of Rightsizing On Shareholders Value in Micro Finance Banks in Lagos State, NigeriaDocument10 pagesImpact of Rightsizing On Shareholders Value in Micro Finance Banks in Lagos State, NigeriaIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document6 pagesChapter 8Mark Dave SambranoNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Consumer Protection ActDocument2 pagesCase Study On Consumer Protection ActNeha Chugh100% (4)

- Social Inclusion FrameworkDocument10 pagesSocial Inclusion FrameworkAda C.No ratings yet

- Unit 4 Industrial RelationDocument36 pagesUnit 4 Industrial Relationmd shoaib100% (1)

- A Comparative Study of Online and OfflinDocument6 pagesA Comparative Study of Online and OfflinMelody BautistaNo ratings yet

- Strength Behind Shaan'S Success: Company ProfileDocument12 pagesStrength Behind Shaan'S Success: Company Profilesarin_ckNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of CryptocurrencyDocument5 pagesAn Analysis of CryptocurrencyJAVED PATELNo ratings yet

- Contract Management in Construction IndustryDocument3 pagesContract Management in Construction IndustryShubham KesarwaniNo ratings yet

- DPR For Konark Coir ClusterDocument252 pagesDPR For Konark Coir ClusterAvijitSinharoyNo ratings yet

- Mortgage Math 1050Document5 pagesMortgage Math 1050api-248061121No ratings yet

- Economic PolicyDocument2 pagesEconomic PolicypodderNo ratings yet

- Ansoff MatrixDocument3 pagesAnsoff MatrixJatin AhujaNo ratings yet

- Ratio Analysis of BGPPLDocument53 pagesRatio Analysis of BGPPLmayurNo ratings yet

- Quantifying The Effects of Financial Conditions On US Activity OECDDocument20 pagesQuantifying The Effects of Financial Conditions On US Activity OECDjibay206No ratings yet

- Role of Government in Financial MarketDocument28 pagesRole of Government in Financial MarketHaji Suleman Ali0% (1)

- Corporate FinanceDocument4 pagesCorporate FinancejosemusiNo ratings yet

Image

Image

Uploaded by

An LeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Image

Image

Uploaded by

An LeCopyright:

Available Formats

36 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE WORLD TRADING SYSTEM

The imbalance in the strength of political forces favouring and opposing liber-

alization provides a possible rationale for the pursuit of reciprocal trade negoti-

ations. Rather trivially, although a (small) country will benefit from liberalizing

its

trade, it is even better if trading partners do the same. More important from a

political economy perspective is that by making liberalization conditional on

greater access to foreign markets, the total gains of liberalization increase and

in

the process liberalization becomes more feasible politically. Being able to point

to

reciprocal, sector-specific export gains may be critical in mobilizing domestic

political support for liberalization at home. By obtaining a reduction in foreign

import barriers as a quid pro quo for a reduction in domestic trade restrictions,

specific export-oriented domestic interests that will gain from liberalization have

an incentive to support it in domestic political markets. This political economy

rationale for reciprocal negotiations is now generally accepted as a basic explan-

ation for the existence of trade agreements and the WTO.

Economists often stress the importance of the terms of trade in providing a

theoretically consistent rationale for the formation of trade agreements. The

argument is that countries negotiate away the negative terms-of-trade external-

ities that would be created by the imposition of trade restrictions in partner

countries (Bagwell and Staiger, 2002). Questions can be raised regarding the

empirical relevance of this explanation for small countries that cannot affect

world prices (in the terms of trade sense). Part of the answer may be that most

products that are traded are differentiated, potentially giving small countries

some market power (as what matters is not the size of the country, but the degree

to which the product(s) of the country are substitutable and the number and cost

of alternative suppliers of substitutes). However, for low-income countries that

export mostly commodities the empirical relevance of such product differentiation-

based market power is likely to be very limited. More important, governments of a

small country may want to be a member of the WTO because its exporters will

benefit from the low tariffs that large WTO member countries negotiate recipro-

cally with one another but must then extend to all other members under the

MEN rule.

This explanation can only be partial, however, because it does not explain why

large countries want small countries to join the WTO. It may be that in practice

large countries simply do not care, as small countries cannot affect the terms of

trade. An implication is that trade agreements will tend to reflect the concerns of

large countries, and that reciprocal exchanges of trade policy commitments will be

concentrated among large countries. To a significant extent this is indeed what

occurs. However, at the same time large countries have supported expansion of the

membership of the WTO, and negotiated bilateral trade treaties and preferential

access arrangements with small countries. This is difficult to square with the

terms-

of-trade explanation for trade agreements, suggesting other motivations must be

relevant as well.

You might also like

- Dental Starting A Practice WorkbookDocument41 pagesDental Starting A Practice WorkbookD.WorkuNo ratings yet

- Sample QuestionsDocument5 pagesSample QuestionsAkash BalgobinNo ratings yet

- Job Order Costing Difficult RoundDocument8 pagesJob Order Costing Difficult RoundsarahbeeNo ratings yet

- Some of The Key Reasons For The Emergence of WTODocument4 pagesSome of The Key Reasons For The Emergence of WTOShilpa ShreeNo ratings yet

- Pitrela Essay - Fresto - TriszkaDocument8 pagesPitrela Essay - Fresto - TriszkaTriszkaNo ratings yet

- Theory of Economic IntegrationDocument39 pagesTheory of Economic IntegrationJustin Lim100% (1)

- What Do Trade Agreements Really DoDocument5 pagesWhat Do Trade Agreements Really DoGagan AnandNo ratings yet

- Gatt, WTO and GlobalizationDocument29 pagesGatt, WTO and GlobalizationGaurav NavaleNo ratings yet

- Economic Integration TheoryDocument39 pagesEconomic Integration Theorycarlosp2015No ratings yet

- Narrative Report - Chapter 10Document4 pagesNarrative Report - Chapter 10Hazel BorboNo ratings yet

- PTA BuildingDocument4 pagesPTA BuildingAnne S. Yen100% (1)

- South Asian Free Trade AgreementDocument44 pagesSouth Asian Free Trade AgreementZeeshan Adeel100% (3)

- The Proliferation of RTA and India PositionDocument11 pagesThe Proliferation of RTA and India PositionDr. Babar Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- 1846 01 WCJ v12n1 AltemoellerDocument10 pages1846 01 WCJ v12n1 AltemoellerGrazelle DomanaisNo ratings yet

- Law and Economics Final DraftDocument10 pagesLaw and Economics Final Draftmayankjuly04No ratings yet

- Final Reaction Paper 1 MFNDocument11 pagesFinal Reaction Paper 1 MFNFazilda NabeelNo ratings yet

- International Trade Theory and Policy 11Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument31 pagesInternational Trade Theory and Policy 11Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFRobinCummingsfikg100% (12)

- REGIONAL TRADE BLOCS PPT IntroductionDocument14 pagesREGIONAL TRADE BLOCS PPT IntroductionAnwar Khan100% (1)

- M09 Krug8283 08 SG C09Document10 pagesM09 Krug8283 08 SG C09Andrés ChacónNo ratings yet

- International Political EconomyDocument8 pagesInternational Political EconomySajida RiazNo ratings yet

- Discuss Whether Regionalism (PTA) Is Helping or Hindering The Achievement of Global Free Trade. BuildingDocument3 pagesDiscuss Whether Regionalism (PTA) Is Helping or Hindering The Achievement of Global Free Trade. BuildingAnne S. YenNo ratings yet

- Gatt and WtoDocument2 pagesGatt and WtoSatya PanduNo ratings yet

- Regional Trade BlocsDocument15 pagesRegional Trade BlocsAnwar KhanNo ratings yet

- International Economics Theory and Policy 11Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument31 pagesInternational Economics Theory and Policy 11Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFPamelaHillqans100% (13)

- Youth in Policymaking and GovernanceDocument2 pagesYouth in Policymaking and GovernanceGodhuliNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1Document23 pagesLecture 1Sadia Islam MimNo ratings yet

- The Basics of Non-Discrimination Principle WTODocument5 pagesThe Basics of Non-Discrimination Principle WTOFirman HamdanNo ratings yet

- Making The Rules 05Document27 pagesMaking The Rules 05gonzalezgalarzaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Trade BlocsDocument5 pagesThe Effects of Trade BlocsKalpesh BhagneNo ratings yet

- Globalization, Trade and Business PDFDocument13 pagesGlobalization, Trade and Business PDFEconomics LabNo ratings yet

- Seattle and Beyond: A WTO Agenda For The New Millennium, Cato Trade Policy Analysis No. 8Document45 pagesSeattle and Beyond: A WTO Agenda For The New Millennium, Cato Trade Policy Analysis No. 8Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Role of WtoDocument7 pagesRole of Wtomuna1990No ratings yet

- Preferential Trade Agreements, Investment Disciplines and Investment FlowsDocument21 pagesPreferential Trade Agreements, Investment Disciplines and Investment FlowsMihaela NicoaraNo ratings yet

- 5article Review Trade - Liberalization - and - GlobalizationDocument10 pages5article Review Trade - Liberalization - and - GlobalizationJamal YusufiNo ratings yet

- What Is Globalisation: Globalisation - Its Benefits and DrawbacksDocument9 pagesWhat Is Globalisation: Globalisation - Its Benefits and Drawbacksbruhaspati1210No ratings yet

- Regional Trade AgreementsDocument4 pagesRegional Trade AgreementsNazsh AnwarNo ratings yet

- GTA Policy BriefDocument8 pagesGTA Policy BriefUdit NarangNo ratings yet

- Internationaltrade 11Document5 pagesInternationaltrade 11Bisrat MekonenNo ratings yet

- Customs Unions and Free Trade AreasDocument6 pagesCustoms Unions and Free Trade AreasÖzer AksoyNo ratings yet

- Multi Layer Regional PactsDocument3 pagesMulti Layer Regional PactsHussain Mohi-ud-Din QadriNo ratings yet

- Wto and Devloping CountriesDocument24 pagesWto and Devloping Countrieskj201992No ratings yet

- Economics Stimulus EssayDocument4 pagesEconomics Stimulus Essaytimberap 27No ratings yet

- Principles of The Trading System: Trade Without DiscriminationDocument5 pagesPrinciples of The Trading System: Trade Without DiscriminationVIJAYADARSHINI VIDJEANNo ratings yet

- Comilla University: Department of MarketingDocument17 pagesComilla University: Department of MarketingMurshid IqbalNo ratings yet

- 2022 How Does Import Market Power Matter For Trade AgreementsDocument20 pages2022 How Does Import Market Power Matter For Trade AgreementsShourya MarwahaNo ratings yet

- Purposes of Regional Trade BlocksDocument7 pagesPurposes of Regional Trade BlocksSukumar ThamilmaniNo ratings yet

- World Trade Organization ProjectDocument42 pagesWorld Trade Organization ProjectNiket Dattani100% (1)

- ECOMACDocument3 pagesECOMACquennieguanco22No ratings yet

- Assignment FinalDocument34 pagesAssignment FinalSaina KennethNo ratings yet

- Understanding The WtoDocument7 pagesUnderstanding The WtoNabinSundar NayakNo ratings yet

- International Trade Polic2 - GATTDocument5 pagesInternational Trade Polic2 - GATTEmmanuel BongayNo ratings yet

- (Cobibcl) Long Quiz 2Document5 pages(Cobibcl) Long Quiz 2Courtney TulioNo ratings yet

- Competition Law and International TradeDocument17 pagesCompetition Law and International Tradevainygoel100% (2)

- 01 Iie 3616Document33 pages01 Iie 3616PaolaNo ratings yet

- ITL Important TopicsDocument11 pagesITL Important TopicsTushar GuptaNo ratings yet

- Dispute Settlement Mechanism and Developing NationsDocument5 pagesDispute Settlement Mechanism and Developing Nationshaseeb ahmedNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of The Levels of Economic IntegrationDocument3 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of The Levels of Economic IntegrationMartha L Pv RNo ratings yet

- Final Copy of Econghghomic ItegrationDocument20 pagesFinal Copy of Econghghomic ItegrationSneha BandarkarNo ratings yet

- An Economic Theory of GATTDocument56 pagesAn Economic Theory of GATTgargargarfieldNo ratings yet

- Most Favoured NationDocument17 pagesMost Favoured Nationrishabhsingh261No ratings yet

- International Trade Subsidy Rules and Tax and Financial Export Incentives: From Limitations on Fiscal Sovereignty to Development-Inducing MechanismsFrom EverandInternational Trade Subsidy Rules and Tax and Financial Export Incentives: From Limitations on Fiscal Sovereignty to Development-Inducing MechanismsNo ratings yet

- ImageDocument1 pageImageAn LeNo ratings yet

- ImageDocument1 pageImageAn LeNo ratings yet

- IRDocument1 pageIRAn LeNo ratings yet

- International RelationsDocument1 pageInternational RelationsAn LeNo ratings yet

- ImageDocument1 pageImageAn LeNo ratings yet

- International EconomicsDocument1 pageInternational EconomicsAn LeNo ratings yet

- PS Enterprise Payroll For North America 9.1Document1,358 pagesPS Enterprise Payroll For North America 9.1ronaldcgreyNo ratings yet

- International Trade and Business ExamDocument2 pagesInternational Trade and Business ExamKristina Jane De CastroNo ratings yet

- Leadership Case: Cool ProductsDocument2 pagesLeadership Case: Cool ProductsRushabh ShahNo ratings yet

- Potato Industry Report 2014 - 2015 Zambia AfricaDocument122 pagesPotato Industry Report 2014 - 2015 Zambia AfricaGRAMYA Pvt Ltd.No ratings yet

- Zakat Self-Assessment: Section 1 - Do You Have To Pay Zakat This Year ?Document3 pagesZakat Self-Assessment: Section 1 - Do You Have To Pay Zakat This Year ?Hasan Irfan SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- The Logistics MarketplaceDocument19 pagesThe Logistics MarketplacePablo UgaldeNo ratings yet

- Askari Bank Schedule of Charges PDFDocument20 pagesAskari Bank Schedule of Charges PDFJHKJHKJHKHJHKNo ratings yet

- Chap 6 HomeworkDocument2 pagesChap 6 HomeworkTaghi MammadovNo ratings yet

- Revealed Preference TheoryDocument5 pagesRevealed Preference TheoryRitu SundraniNo ratings yet

- Circular CGST 199Document4 pagesCircular CGST 199Jaipur-B Gr-2No ratings yet

- الشركات متعددة الجنسيات InaDocument23 pagesالشركات متعددة الجنسيات InamouradNo ratings yet

- Impact of Rightsizing On Shareholders Value in Micro Finance Banks in Lagos State, NigeriaDocument10 pagesImpact of Rightsizing On Shareholders Value in Micro Finance Banks in Lagos State, NigeriaIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document6 pagesChapter 8Mark Dave SambranoNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Consumer Protection ActDocument2 pagesCase Study On Consumer Protection ActNeha Chugh100% (4)

- Social Inclusion FrameworkDocument10 pagesSocial Inclusion FrameworkAda C.No ratings yet

- Unit 4 Industrial RelationDocument36 pagesUnit 4 Industrial Relationmd shoaib100% (1)

- A Comparative Study of Online and OfflinDocument6 pagesA Comparative Study of Online and OfflinMelody BautistaNo ratings yet

- Strength Behind Shaan'S Success: Company ProfileDocument12 pagesStrength Behind Shaan'S Success: Company Profilesarin_ckNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of CryptocurrencyDocument5 pagesAn Analysis of CryptocurrencyJAVED PATELNo ratings yet

- Contract Management in Construction IndustryDocument3 pagesContract Management in Construction IndustryShubham KesarwaniNo ratings yet

- DPR For Konark Coir ClusterDocument252 pagesDPR For Konark Coir ClusterAvijitSinharoyNo ratings yet

- Mortgage Math 1050Document5 pagesMortgage Math 1050api-248061121No ratings yet

- Economic PolicyDocument2 pagesEconomic PolicypodderNo ratings yet

- Ansoff MatrixDocument3 pagesAnsoff MatrixJatin AhujaNo ratings yet

- Ratio Analysis of BGPPLDocument53 pagesRatio Analysis of BGPPLmayurNo ratings yet

- Quantifying The Effects of Financial Conditions On US Activity OECDDocument20 pagesQuantifying The Effects of Financial Conditions On US Activity OECDjibay206No ratings yet

- Role of Government in Financial MarketDocument28 pagesRole of Government in Financial MarketHaji Suleman Ali0% (1)

- Corporate FinanceDocument4 pagesCorporate FinancejosemusiNo ratings yet