Professional Documents

Culture Documents

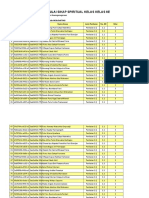

PG 4

PG 4

Uploaded by

Erdinç Kuşçu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views1 pageThe document discusses the title and nature of Marcus Aurelius' work known as Meditations. It was likely not given a title by Marcus himself since it was not written for publication, but rather as private notes. While later known as Meditations, this title does not accurately capture its informal nature as a collection of haphazard notes. The entries also include cryptic references that would only be understandable to Marcus, showing they were intended solely for his own reflection on his role as emperor. Scholars debate how to categorize the work, as it does not neatly fit classifications like a diary, philosophical treatise, or philosopher's working notes, though it shares some qualities with each.

Original Description:

Original Title

pg4

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses the title and nature of Marcus Aurelius' work known as Meditations. It was likely not given a title by Marcus himself since it was not written for publication, but rather as private notes. While later known as Meditations, this title does not accurately capture its informal nature as a collection of haphazard notes. The entries also include cryptic references that would only be understandable to Marcus, showing they were intended solely for his own reflection on his role as emperor. Scholars debate how to categorize the work, as it does not neatly fit classifications like a diary, philosophical treatise, or philosopher's working notes, though it shares some qualities with each.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views1 pagePG 4

PG 4

Uploaded by

Erdinç KuşçuThe document discusses the title and nature of Marcus Aurelius' work known as Meditations. It was likely not given a title by Marcus himself since it was not written for publication, but rather as private notes. While later known as Meditations, this title does not accurately capture its informal nature as a collection of haphazard notes. The entries also include cryptic references that would only be understandable to Marcus, showing they were intended solely for his own reflection on his role as emperor. Scholars debate how to categorize the work, as it does not neatly fit classifications like a diary, philosophical treatise, or philosopher's working notes, though it shares some qualities with each.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 1

Best Books.

He would have been surprised, to begin with, by the title of the

work ascribed to him. The long-established English title Meditations is not

only not original, but positively misleading, lending a spurious air of

resonance and authority quite alien to the haphazard set of notes that

constitute the book. In the lost Greek manuscript used for the first printed

edition—itself many generations removed from Marcus’s original—the

work was entitled “To Himself” (Eis heauton). This is no more likely than

Meditations to be the original title, though it is at least a somewhat more

accurate description of the work.6

In fact, it seems unlikely that Marcus himself gave the work any title at

all, for the simple reason that he did not think of it as an organic whole in

the first place. Not only was it not written for publication, but Marcus

clearly had no expectation that anyone but himself would ever read it. The

entries include a number of cryptic references to persons or events that an

ancient reader would have found as unintelligible as we do. While a

contemporary might have recognized some of the figures mentioned in

Meditations 8.25 or 12.27, for example, no ancient reader could have

known what was in the letter that Rusticus wrote from Sinuessa (1.7), what

Antoninus said to the customs agent at Tusculum (1.16), or what happened

to Marcus at Caieta (1.17). Elsewhere Marcus reflects directly on his role as

emperor, in terms that would be quite irrelevant to anyone else. We find him

worrying about the dangers of becoming “imperialized” (6.30), reminding

himself to speak simply in the Senate (8.30), and reflecting on the unique

position he occupies (11.7). From these entries and others it seems clear that

the “you” of the text is not a generic “you,” but the emperor himself.

“When you look at yourself, see any of the emperors” (10.31).

How are we to categorize the Meditations? It is not a diary, at least in

the conventional sense. The entries contain little or nothing related to

Marcus’s day-to-day life: few names, no dates and, with two exceptions, no

places. It also lacks the sense of audience—the reader over one’s shoulder

—that tends to characterize even the most secretive diarist. Some scholars

have seen it as the basis for an unwritten larger treatise, like Pascal’s

Pensées or the notebooks of Joseph Joubert. Yet the notes are too repetitive

and, in a philosophical sense, too elementary for that. The entries perhaps

bear a somewhat closer resemblance to the working notes of a practicing

philosopher: Wittgenstein’s Zettel, say, or the Cahiers of Simone Weil. Yet

here, too, there is a significant difference. The Meditations is not tentative

You might also like

- SEMRA NÜFUS KAYIT ÖRNEĞİ-EnglıshDocument5 pagesSEMRA NÜFUS KAYIT ÖRNEĞİ-EnglıshErdinç Kuşçu100% (1)

- The Key of SolomonDocument142 pagesThe Key of Solomonnorriott100% (7)

- The Greater Key of Solomon in Five Books - Peterson Edition - 2010Document292 pagesThe Greater Key of Solomon in Five Books - Peterson Edition - 2010Kahel_Seraph100% (11)

- Nüfus Kayıt Örneği 1Document1 pageNüfus Kayıt Örneği 1Erdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Exercise 3. Reaction Paper: Development and Martin Heidegger's The Question Concerning Technology. ThenDocument1 pageExercise 3. Reaction Paper: Development and Martin Heidegger's The Question Concerning Technology. Thenrjay manalo100% (2)

- Logotherapy and Existential AnalysisDocument15 pagesLogotherapy and Existential Analysisedson miazatoNo ratings yet

- Poor Widow in MarkDocument17 pagesPoor Widow in Mark31songofjoyNo ratings yet

- Sol: The Sun in The Art and Religions of Rome. Link To The Full Text and Introductory RemarksDocument5 pagesSol: The Sun in The Art and Religions of Rome. Link To The Full Text and Introductory Remarkss_hijmans0% (1)

- Flowers Stephen Red RunaDocument53 pagesFlowers Stephen Red RunaJoCxxxygenNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument10 pagesEssaySqueak DollphinNo ratings yet

- Yerleşim Yeri - İNGİLİZCEDocument5 pagesYerleşim Yeri - İNGİLİZCEErdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Paul Anthony Samuelson-Foundations of Economic Analysis-Cambridge, Harvard University Press, (1947)Document447 pagesPaul Anthony Samuelson-Foundations of Economic Analysis-Cambridge, Harvard University Press, (1947)OmarAndredelaSota100% (2)

- Marcus Aurelius in His MeditationsDocument21 pagesMarcus Aurelius in His Meditations0177986No ratings yet

- Reader's Guide: The Mind of The South - W. J.Document40 pagesReader's Guide: The Mind of The South - W. J.CocceiusNo ratings yet

- Helena Blavatsky Collected Writings Volume VIII 1887Document347 pagesHelena Blavatsky Collected Writings Volume VIII 1887Thuan Do100% (1)

- Complete Works of Marcus Aurelius (Illustrated)From EverandComplete Works of Marcus Aurelius (Illustrated)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Ptebt 703 and The Genre of 1 TimothyDocument28 pagesPtebt 703 and The Genre of 1 TimothyAhmed EmamNo ratings yet

- Review. Etymologicum Genuinum. Les Citations de Poètes Lyriques by Claude CalameDocument3 pagesReview. Etymologicum Genuinum. Les Citations de Poètes Lyriques by Claude CalameTiago da Costa GuterresNo ratings yet

- J. Ramsey Michael's 'Revelation'Document2 pagesJ. Ramsey Michael's 'Revelation'Jim WestNo ratings yet

- Niccolò MachiavelliDocument7 pagesNiccolò MachiavellianisNo ratings yet

- Neither Acts or MonumentsDocument28 pagesNeither Acts or MonumentsAnjar RahmanNo ratings yet

- Apocalypsis and EmpireDocument3 pagesApocalypsis and Empirealcides lauraNo ratings yet

- Mazes and Labyrinths: A General Account of Their History and DevelopmentFrom EverandMazes and Labyrinths: A General Account of Their History and DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Palaeography, Codicology, Diplomatics, and The Editing of Texts: An Elementary Vocabulary"Document19 pagesPalaeography, Codicology, Diplomatics, and The Editing of Texts: An Elementary Vocabulary"abgarosNo ratings yet

- 1 3 HammondDocument4 pages1 3 Hammondnahla_staroNo ratings yet

- Brown, Marshall. Periods and ResistancesDocument8 pagesBrown, Marshall. Periods and ResistancesgobomaleNo ratings yet

- Chaldæan Oracles (Westcott Edition)Document38 pagesChaldæan Oracles (Westcott Edition)Celephaïs Press / Unspeakable Press (Leng)100% (6)

- Hidden Moses Ebook-2019Document27 pagesHidden Moses Ebook-2019Abdallah Mohamed AboelftouhNo ratings yet

- MeditationsDocument307 pagesMeditationsleo saini100% (6)

- UntitledDocument10 pagesUntitledrendy anggaraNo ratings yet

- Rikk Watts - Why The Gospel-Narratives Are ImportantDocument11 pagesRikk Watts - Why The Gospel-Narratives Are ImportantDaniel MartinezNo ratings yet

- The Letters of Cassiodorus Being A Condensed Translation Of The Variae Epistolae Of Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus SenatorFrom EverandThe Letters of Cassiodorus Being A Condensed Translation Of The Variae Epistolae Of Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus SenatorNo ratings yet

- Views On The Ending of The Gospel of MarkDocument7 pagesViews On The Ending of The Gospel of MarkPaul BurkhartNo ratings yet

- 3 The Meaning of The Monas Hieroglyphica With Regards To Geometry PDFDocument208 pages3 The Meaning of The Monas Hieroglyphica With Regards To Geometry PDFnirguna100% (1)

- Michael Murphy James Clawson, Companion To Medieval English LiteratureDocument146 pagesMichael Murphy James Clawson, Companion To Medieval English LiteratureValeriu GherghelNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument10 pagesUntitledrendy anggaraNo ratings yet

- The Tin Drum by Günter Grass - Discussion QuestionsDocument11 pagesThe Tin Drum by Günter Grass - Discussion QuestionsHoughton Mifflin HarcourtNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Russell HWPDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Russell HWPsatalexaNo ratings yet

- David Roochnik Epoche Aristotles Dialogu PDFDocument19 pagesDavid Roochnik Epoche Aristotles Dialogu PDFShahzad KhanNo ratings yet

- A Testament Is BornDocument6 pagesA Testament Is BornnalisheboNo ratings yet

- Paul and The Popular Philosophers (Review) - Abraham J. Malherbe.Document2 pagesPaul and The Popular Philosophers (Review) - Abraham J. Malherbe.Josue Pantoja BarretoNo ratings yet

- Jasonis Et Papisti, A Dialogue Between A Jewish Christian (Jason) and AnDocument8 pagesJasonis Et Papisti, A Dialogue Between A Jewish Christian (Jason) and AnderfghNo ratings yet

- Elisabetta Sciarra, La Tradizione Degli Scholia Iliadici in Terra D'otranto BZ 100 - 1 2007Document3 pagesElisabetta Sciarra, La Tradizione Degli Scholia Iliadici in Terra D'otranto BZ 100 - 1 2007Federica GrassoNo ratings yet

- The English Essay and Essayists (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandThe English Essay and Essayists (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- Inventing The Human: Brontosaurus Bloom and The Shakespeare in Us'Document26 pagesInventing The Human: Brontosaurus Bloom and The Shakespeare in Us'PedroB24No ratings yet

- Marius: On The Elements: A Critical Edition and TranslationFrom EverandMarius: On The Elements: A Critical Edition and TranslationNo ratings yet

- Exposito Rs Greek T 02 NicoDocument970 pagesExposito Rs Greek T 02 NicodavidhankoNo ratings yet

- A Prosopography To Martials Epigrams 9783110624755 9783110621358Document714 pagesA Prosopography To Martials Epigrams 9783110624755 9783110621358Trent HardestyNo ratings yet

- To Shatter All The Classical Theories oDocument24 pagesTo Shatter All The Classical Theories oCarlos Augusto AfonsoNo ratings yet

- Malbon Review of Broadhead - Mark CommentaryDocument4 pagesMalbon Review of Broadhead - Mark CommentaryMike WhitentonNo ratings yet

- Review of Cultural Amnesia by Clive JamesDocument4 pagesReview of Cultural Amnesia by Clive JamesCerita Loteng BukuNo ratings yet

- Review de Walter CahnDocument2 pagesReview de Walter CahnfrancisbhNo ratings yet

- Marcus Aurelius, Robin Waterfield (Editor) - Meditations - The Annotated Edition (2021, Basic Books) - Libgen - LiDocument289 pagesMarcus Aurelius, Robin Waterfield (Editor) - Meditations - The Annotated Edition (2021, Basic Books) - Libgen - LiMOTIINo ratings yet

- Lane Cooper Resenha John Burnet. Aristotle (The British Academy, Annual Lecture On A Master-Mind, Henriette Hertz Trust)Document5 pagesLane Cooper Resenha John Burnet. Aristotle (The British Academy, Annual Lecture On A Master-Mind, Henriette Hertz Trust)Carlos PachecoNo ratings yet

- AQUINAS'S NOTION OF PURE NATURE AND THE CHRISTIAN INTEGRALISM OF HENRI DE LUBAC. NOT EVERYTHING IS GRACE by Bernard MulcahyDocument17 pagesAQUINAS'S NOTION OF PURE NATURE AND THE CHRISTIAN INTEGRALISM OF HENRI DE LUBAC. NOT EVERYTHING IS GRACE by Bernard Mulcahypishowi1No ratings yet

- PG 3Document1 pagePG 3Erdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- PG 5Document1 pagePG 5Erdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Quality Management Procedure: 1 PurposeDocument5 pagesQuality Management Procedure: 1 PurposeErdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Pge 2Document1 pagePge 2Erdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- 2Document1 page2Erdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Change Log From Heavy Gear Blitz 3.0 To 3.1Document1 pageChange Log From Heavy Gear Blitz 3.0 To 3.1Erdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- 3-KP 17 Önleyici Faaliyet-EnDocument5 pages3-KP 17 Önleyici Faaliyet-EnErdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Quality Management Procedure: 1 PurposeDocument5 pagesQuality Management Procedure: 1 PurposeErdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Bodrum Genel Bilgi-EnDocument2 pagesBodrum Genel Bilgi-EnErdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Extract of Civil Registry Record Province Town District/Village Volume No. Section NoDocument1 pageExtract of Civil Registry Record Province Town District/Village Volume No. Section NoErdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Faaliyet Belgesi - İNGİLİZCEDocument1 pageFaaliyet Belgesi - İNGİLİZCEErdinç KuşçuNo ratings yet

- Environmental PhilosophyDocument17 pagesEnvironmental PhilosophyAngelyn Lingatong100% (1)

- INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY Module 2Document15 pagesINTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY Module 2Erwin AllijohNo ratings yet

- What Is CommunicationDocument2 pagesWhat Is Communicationariel agosNo ratings yet

- Stem Cell Research DebatesDocument2 pagesStem Cell Research Debatesapi-485110415No ratings yet

- Agung Prasetya - TenseDocument15 pagesAgung Prasetya - TenseSri Ayu UtamiNo ratings yet

- Anti-Natalism:: Response: NODocument2 pagesAnti-Natalism:: Response: NODee RazzNo ratings yet

- Lialy Sarti - 17029064 - Task XIIDocument15 pagesLialy Sarti - 17029064 - Task XIIlialy sartiNo ratings yet

- ﺔﻔﺴﻠﻓ ﻲﻓ ةرﺎﻤﻌﻟا Architecture According To Philosophy Of Crossing رﻮﺒﻌﻟاDocument16 pagesﺔﻔﺴﻠﻓ ﻲﻓ ةرﺎﻤﻌﻟا Architecture According To Philosophy Of Crossing رﻮﺒﻌﻟاأحمد العراقيNo ratings yet

- Jose Rizal and His Times (19 Century) Objectives: at The End of This Topic, The Students Are Expected ToDocument12 pagesJose Rizal and His Times (19 Century) Objectives: at The End of This Topic, The Students Are Expected ToMy HomeNo ratings yet

- The Parable of The Rainbow ColorsDocument73 pagesThe Parable of The Rainbow ColorsMisty Mountain100% (1)

- Osho On SymbolsDocument4 pagesOsho On SymbolsDhyan TarpanNo ratings yet

- Love Made in The First Age PrecisDocument2 pagesLove Made in The First Age PrecisJ. Andrew MillerNo ratings yet

- To Which Philosophy/ies Each Theory of Man Belong? Write Your Answer On The Second Column of Each StatementDocument2 pagesTo Which Philosophy/ies Each Theory of Man Belong? Write Your Answer On The Second Column of Each StatementMhark ValdezNo ratings yet

- Motivation Letter of IfwarisanDocument2 pagesMotivation Letter of IfwarisanIrnin M Airyq d'LscNo ratings yet

- Philosophy Infographics by SlidesgoDocument28 pagesPhilosophy Infographics by Slidesgomarcel pranotoNo ratings yet

- The Death of Ivan Ilych (Litcharts)Document53 pagesThe Death of Ivan Ilych (Litcharts)neel_103No ratings yet

- To Be or Not To Be SoliloquyDocument1 pageTo Be or Not To Be SoliloquySarah ChoiNo ratings yet

- Proper Language Use: Reading and Thinking Strategies Across Text TypesDocument14 pagesProper Language Use: Reading and Thinking Strategies Across Text TypesAmihan Comendador GrandeNo ratings yet

- Anthropometry and Its Role in Different Architectural SceneDocument5 pagesAnthropometry and Its Role in Different Architectural SceneJOHN PATRICK BULALACAO0% (1)

- Fundamental Concepts of Morality OverviewDocument19 pagesFundamental Concepts of Morality OverviewGladyz AlbiosNo ratings yet

- F - Spiritual - Pendidikan Pancasila Dan Kewarganegaraan - KELAS 8EDocument9 pagesF - Spiritual - Pendidikan Pancasila Dan Kewarganegaraan - KELAS 8EEka PutraNo ratings yet

- Goal Setting ToolkitDocument10 pagesGoal Setting ToolkitElianaReyssNo ratings yet

- 1001 Lecture 1 Slides 2023 For StudentsDocument32 pages1001 Lecture 1 Slides 2023 For StudentsjohnsoneianNo ratings yet

- Lesser Gifts: Space Scalpel On TurnDocument7 pagesLesser Gifts: Space Scalpel On TurnfenrisNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Management 12th Edition by Schermerhorn Sample ChapterDocument26 pagesTest Bank For Management 12th Edition by Schermerhorn Sample ChapterAndrea NovillasNo ratings yet

- Friedman & CarrollDocument18 pagesFriedman & CarrollNguyen T Phuong88% (8)

- Padilla Activity 1Document2 pagesPadilla Activity 1Sison, Mikyle M.100% (1)