Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Article - Syrien Und r2p

Article - Syrien Und r2p

Uploaded by

dianaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Article - Syrien Und r2p

Article - Syrien Und r2p

Uploaded by

dianaCopyright:

Available Formats

Was R2P a viable option for Syria?

Opinion content in the Globe and Mail and the

National Post, 2011–2013

Author(s): Tom Pierre Najem, Walter C. Soderlund, E. Donald Briggs and Sarah Cipkar

Source: International Journal , Vol. 71, No. 3 (SEPTEMBER 2016), pp. 433-449

Published by: Sage Publications, Ltd. on behalf of the Canadian International Council

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26414041

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26414041?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sage Publications, Ltd. and Canadian International Council are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Scholarly Essay

International Journal

2016, Vol. 71(3) 433–449

Was R2P a viable option ! The Author(s) 2016

Reprints and permissions:

for Syria? Opinion sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0020702016662796

content in the Globe and ijx.sagepub.com

Mail and the National

Post, 2011–2013

Tom Pierre Najem

University of Windsor, Canada

Walter C. Soderlund

University of Windsor, Canada

E. Donald Briggs

University of Windsor, Canada

Sarah Cipkar

University of Windsor, Canada

Abstract

In the spring of 2011 the Syrian civil war emerged as a late chapter of the ‘‘Arab Spring,’’

a chapter that in retrospect has turned out to be the most complex and potentially

most serious. How such crisis events are framed in press coverage has been identified

as important with respect to possible responses the international community makes

under the doctrine of Responsibility to Protect (R2P). By most indicators (number of

casualties, number of refugees, plus the use of chemical weapons against civilians), Syria

certainly qualified as a candidate for the application of a UN Security Council authorized

R2P reaction response; yet during the first two-and-a-half years of the war no such

action was forthcoming.

This research examines editorial and opinion pieces on Syria appearing in two leading

Canadian newspapers, the Globe and Mail and the National Post, from March 2011 to

September 2013 in terms of assessing how the civil war was framed regarding the

appropriateness of an R2P military response on the part of the international community.

The research has both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. The former examines

whether framing promoted or discouraged international involvement (i.e. a ‘‘will to

Corresponding author:

Tom Pierre Najem, University of Windsor, Political Science, 401 Sunset Avenue, Chrysler Hall North,

Windsor, ON N9B 3P4, Canada.

Email: tnajem@uwindsor.ca

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

434 International Journal 71(3)

intervene’’), as well as whether diplomatic and especially military actions such as a

‘‘no-fly zone’’ or more direct military attacks would be likely to result in success or

failure. Qualitatively, the major positions taken and arguments presented regarding R2P,

and whether it should be invoked for Syria, are reviewed.

Keywords

Canadian foreign policy, civil war, Globe and Mail, international intervention, Middle East,

National Post, R2P, Syria, UN, US foreign policy

The 2001 Report of the International Commission on Intervention and State

Sovereignty, ‘‘The Responsibility to Protect’’ (R2P), sought to redirect the

world’s attention from the traditional but increasingly problematic emphasis on

state sovereignty to the responsibilities of both nation states and the international

community to provide for the human security of states’ inhabitants.1 More specif-

ically, it sought to reduce the impediments to collective action when no other means

of protecting people from egregious violence were available. It laid on the inter-

national community the well-known three-fold responsibility to prevent such

occurrences, react to them when prevention failed, and rebuild after any reaction

that was necessary.

R2P did not seek to provide carte blanche for international military operations in

any and all instances of humanitarian crisis. It emphasized, in fact, that resorting to

a military reaction should only occur when all other methods of intervention had

been exhausted, and then only under strict conditions—such as confidence of suc-

cess and assurance that forceful methods would not worsen the situation. The form

ultimately endorsed by the United Nations in 2006 also made clear that the

Security Council would be the arbiter of if, when, and how R2P would be

operationalized.2

In a strict sense, therefore, R2P changed little. The same body as before

remained charged with dealing with challenges to the conscience of humanity

according to the same methods as existed prior to its appearance. This said,

R2P’s greatest virtue might be that it takes a fairly significant step in the direction

of human security. It may have altered little in a procedural or legal sense, but it

undoubtedly elevated the principle that the protection of human beings must

become a central focus of international efforts to create a better world. That in

itself increases the pressure on all governments to respond in a positive manner to

1. International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, ‘‘The Responsibility to Protect:

Report of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty,’’ International

Development Research Centre (IDRC), 2001, http://responsibilitytoprotect.org/ICISS%

20Report.pdf (accessed 28 July 2014).

2. See Theresa Reinold, ‘‘The responsibility to protect—much ado about nothing?’’ Review of

International Studies 36 (2010): 61; see also Aidan Hehir, The Responsibility to Protect: Rhetoric,

Reality and the Future of Humanitarian Intervention (New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2012).

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Najem et al. 435

obvious humanitarian needs wherever and whenever they appear. Moreover, it

underlines not only their right but also their duty to do so. R2P will not, and

should not, eliminate the need for each government to evaluate crisis situations

for itself and weigh what it might be able to contribute toward alleviating them, but

it should increase states’ willingness to at least consider that possibility. That may

be seen as scant progress by the impatient, but it’s a real advance over the thinking

prevalent at the time of the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

For R2P boosters, the task now is to convert a statement of moral principle into

an obligation for decisive action. In the view of Frank Chalk and associates, this

will necessitate creating a ‘‘will to intervene’’ by world states, and that in turn will

depend heavily on the performance of the mass media:

The ‘‘fourth estate’’—the news media—exerts a powerful influence on government.

The ‘‘CNN effect’’ is credited with persuading the U.S. and Canadian governments to

intervene in Somalia in 1992, Bosnia in 1995, and Eastern Zaire in 1996. Policy experts

argue that the process of ‘‘policy by media,’’ or formulating policy in response to

media coverage, is a contemporary phenomenon that arises from the government’s

sensitivity to media coverage. While news media reports influence policy, the inverse is

also true: an absence of reporting on mass atrocities in a particular country removes

the pressure on the American and Canadian governments to act on their ‘‘responsi-

bility to protect.’’3

Although few analysts today endorse the idea that government policy is literally

media/public opinion driven, they do accept that media coverage, or lack thereof, is

of major interest to democratic policymakers. Indeed, analysts generally recognize

that (a) how much a particular crisis is highlighted,4 and (b) how governments and

the international community are urged to respond to it are both important.

The latter is the focus of the reported research. Specifically, research on

‘‘framing effects’’ has established that the way in which news is presented (e.g.,

what is identified as the problem, who is responsible, and what are the acceptable

boundaries of remedial action) influences the way in which audiences evaluate

possible responses, and thus constitutes the basic input to public opinion, which

few governments deliberately choose to ignore. To our knowledge, no study

3. Frank Chalk, Roméo Dallaire, Kyle Matthews, Carla Barqueiro, and Simon Doyle, ‘‘Mobilizing

the will to intervene: Leadership and action to prevent mass atrocities,’’ Montreal Institute for

Genocide and Human Rights Studies, 2010, 48, http://www4.carleton.ca/cfp/app/serve.php/1244.

pdf (accessed 4 November 2012).

4. Media effects associated with volume of coverage have been studied under the concept of ‘‘agenda

setting.’’ See, for example, Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw, ‘‘The agenda-setting function of

mass media,’’ Public Opinion Quarterly 36, no. 3 (1972): 176–187; Everett Rogers and James

Dearing, ‘‘Agenda-setting research: Where has it been, where is it going?’’ in J. Anderson, ed.,

Communication Yearbook, vol. 11 (Beverley Hills, CA: SAGE Publications, 1988), 555–594;

Maxwell McCombs and Amy Reynolds, ‘‘News influence on our pictures of the world,’’ in J.

Bryant and D. Zillmann, eds., Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. 2nd ed.

(Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004), 1–18; Maxwell McCombs, ‘‘A look at

agenda-setting: Past, present and future,’’ Journalism Studies 6, no. 4 (2005): 543–557.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

436 International Journal 71(3)

dealing with the question of how international involvement in the Syrian conflict

was presented to Western mass publics has been carried out, either in Canada or

elsewhere.5

The Syrian civil war received abundant attention from its beginning, and the

attention only increased with the conflict’s growing severity—indeed, it became a

‘‘mega-story.’’6 How that ample coverage was framed, however, is less obvious.

This research accordingly focuses on how opinion-oriented materials in two leading

Canadian newspapers, both having an active interest in Canadian foreign policy,

appeared to promote or discourage resort to the more forceful components of the

R2P doctrine.

The Syrian civil war: Background and context

In March 2011 protests against the authoritarian regime of Bashar al-Assad broke

out in several parts of Syria. They varied in tactics and aims, but were at the outset

generally peaceful and non-sectarian calls for reform. They were quickly seen as an

extension of the Arab Spring that had already brought about the largely peaceful

end of the 22-year reign of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia, the

30-year presidency of Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, and the 33-year rule of Yemen’s

president Ali Abdullah Salah. More violent actions, including those of a

UN-authorized, NATO-led ‘‘no-fly zone,’’ led to the swift downfall of the

42-year reign of Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi. That international intervention was

widely seen as a direct response to R2P imperatives.

These events unquestionably created a contagion dynamic that exacerbated

deep-seated discontent with Assad’s rule, and when protests transformed into

5. See, for example, Thomas Nelson, Zoe Oxley and Rosalee Clawson, ‘‘Toward a psychology of

framing effects,’’ Political Behavior 19, no. 3 (1997): 221–246; Sean Aday, ‘‘The framesetting effects

of news: An experimental test of advocacy versus objectivist frames,’’ Journalism and Mass

Communications Quarterly 83, no. 4 (2006): 767–784; Adam Berinsky and Donald Kinder,

‘‘Making sense of issues through media frames: Understanding the Kosovo crisis,’’ The Journal

of Politics 68, no. 3 (2006): 640–656; Robert Entman, ‘‘Framing bias: Media in the distribution of

power,’’ Journal of Communication 57, no. 1 (2007): 163–173; Kimberly Gross, ‘‘Framing persuasive

appeals: Episodic and thematic framing, emotional responses, and public opinion,’’ Political

Psychology 29, no. 2 (2008): 169–192; Dietram Scheufele and Shanto Iyengar, ‘‘The state of framing

research: A call for new directions,’’ 2011, http://pcl.stanford.edu/research/2011/scheufele-framing/

pdf (accessed 20 July 2014); Adam Kramer, Jamie Guillory, and Jeffrey Hancock, ‘‘Experimental

evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks,’’ Proc Natl Acad Sci USA

[PNAS] 111, no. 24, 17 June 2014: 8788-8790, http://www.pnas.org/content/111/24/8788.full.pdf

(accessed 10 July 2014).

6. During January 2012, for example, the Factiva database reported a total of 25 ‘‘Syria’’ stories

(including news items, editorials, and opinion pieces) for the Globe and 44 for the Post; by

September of that year, 51 items were reported for the former and 47 for the latter newspaper.

For these randomly selected months, this represents an average of well over a story per day for each

newspaper. An Ipsos poll conducted between 4 September and 18 September and released on 9

October 2013 indicated that 91 percent of Canadians had ‘‘seen, heard or read about the current

situation in Syria.’’ For a succinct breakdown of the polling data, see Ipsos, ‘‘Taking sides on

Syria,’’ 9 October 2013, http://www.ipsos-na.com/news-polls/pressrelease.aspx?id¼6279 (accessed

22 August 2014).

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Najem et al. 437

civil war the humanitarian consequences quickly reached staggering proportions.7

In approximately three years, over 160,000 Syrians died; nearly 3 million became

refugees in neighbouring countries; and more than one-quarter of a population of

23 million became internally displaced. The UN predicted that by the end of 2014

the refugee problem would become the worst ‘‘since the Rwandan genocide 20

years ago.’’8

But these numbers tell only part of the story. When mass rapes, ethnic cleansing,

barbaric treatment of opponents, and especially the use of chemical weapons are

added to them, the case for international intervention on humanitarian grounds is

overwhelming. However, when non-military efforts to stem the carnage proved to

be unsuccessful, there was little inclination for decision makers in Washington,

Ottawa, or elsewhere, to escalate the response to more forceful methods.9

Two questions therefore arise. First, what role did Canada’s press play with

respect to a lack of ‘‘will to intervene’’ on the part of the international community?

And second, does the absence of a military response in Syria mean that R2P

‘‘failed’’ before escaping its infancy? We hope to shed light on both these questions

through an examination of the treatment of the crisis in opinion material appearing

in the National Post and the Globe and Mail.

Research methodology

Data for the research were accessed from the Factiva electronic database beginning

on 1 March 2011 and continuing to 30 September 2013. This period covers the

beginning of protests against the Assad government up to and including a UN

Security Council resolution endorsing the agreement to remove and destroy Syria’s

chemical weapons following their use on 21 August 2013.10 Editorials and opinion

articles were first read to ensure that there was sufficient material dealing with the

Syrian civil war to merit inclusion. Those that dealt with Syrian topics unrelated to

the war and those in which Syria was mentioned peripherally or as an example of

some larger phenomenon were excluded. For the Globe, this vetting process

resulted in 84 cases, while for the Post it yielded 83 cases. These items were then

7. See Marc Lynch, Deen Freelon, and Sean Aday, ‘‘Syria in the Arab Spring: The integration of

Syria’s conflict with the Arab uprisings, 2011–2013.’’ Research and Politics 1 (October-December

2014): 1–7.

8. Mercy Corps, ‘‘Quick facts, what you need to know about the Syria crisis,’’ 19 June 2014, http://

www.mercycorps.org/articles/iraq-jordan-lebanon-syria/quick-facts-what-you-need-know-about-

syria-crisis (accessed 20 August 2014).

9. In the case of Canada, a parliamentary debate on Syria in the spring of 2013 was inconclusive.

According to Globe and Mail reporter Campbell Clark, Canada emerged from the debate with a

policy that called for ‘‘Mr. al-Assad to go, but is so wary of jihadists among rebels it does not want

to tip the balance in their favour’’. Campbell Clark, ‘‘All urgency, no action in Syria debate,’’

Globe and Mail, 9 May 2013, A8.

10. The search term ‘‘Syria’’ was entered, along with the content filters ‘‘Commentaries/Opinion’’ and

‘‘Editorials.’’ The articles resulting from this search were catalogued into a database which was

then cross-referenced with two other electronic databases—Proquest and Canadian

Newsstand—to ensure completeness. Only articles that appeared in printed copies of the news-

papers were included.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

438 International Journal 71(3)

Table 1. Framing leading to a ‘‘will to intervene’’ by newspaper (percentage of total opinion

items).

Globe and Mail National Post Total

N ¼ 84 N ¼ 83 N ¼ 167

Pro Ambiguous Anti Pro Ambiguous Anti Pro Ambiguous Anti

14.3% 14.3% 21.4% 6.0% 18.1% 18.1% 10.2% 16.2% 19.8%

coded according to whether media framing specifically promoted or discouraged a

‘‘will to intervene,’’ as well as whether a stable democratic order was seen as likely

to emerge in Syria at the conflict’s end. In addition, suggested diplomatic and

military strategies were evaluated in terms of their perceived effectiveness in

ending the conflict. Using Ole Holsti’s percentage agreement method, inter-coder

reliability was established at 84.7 percent.11

Finally, in order to provide a greater understanding of what lay behind the

numbers presented in the quantitative analysis, the actual arguments and policy

positions offered in opinion material in the two newspapers dealing with the oper-

ationalization of the R2P doctrine during the first two-and-a-half years of the war

were reviewed.

Quantitative findings

Table 1 indicates that there was nearly twice as much opposition to forceful inter-

national intervention in Syria as support for it; neither paper came even close to

assuming the positive advocacy role hoped for by Chalk and colleagues. Negative

assessments of intervention were somewhat higher in the Globe than in the Post,

although the Globe also ran considerably more pro-intervention pieces than

appeared in the Post. On balance, anti-intervention exceeded pro-intervention

items by 7 percent in the Globe and by 12 percent in the Post.

As seen in Table 2, on neither paper’s opinion pages was hope expressed that the

political situation in Syria would end well. This negative assessment of Syria’s

political future (outstripping even ambiguous ones) clearly bolstered the anti-inter-

vention frame evident in the previous table.

Table 3 addresses the question of which conflict-ending R2P strategies were

evaluated as promising. The dominant finding is that neither diplomacy nor

an ascending range of military strategies was regarded as very promising, although

the Globe expressed more optimism for diplomacy and the Post narrowly endorsed

the idea of a no-fly zone, largely on the basis of arguments imported from the US.

11. Ole Holsti, Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities (Reading, MA: Addison

Wesley, 1969), 140.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Najem et al. 439

Table 2. Assessments of positive or negative outcomes for democracy by newspaper

(percentage of total opinion items).

Globe and Mail National Post Total

N ¼ 84 N ¼ 83 N ¼ 167

Positive Ambiguous Negative Positive Ambiguous Negative Positive Ambiguous Negative

1.2% 13.1% 21.4% 0% 12.0% 22.4% 0.05% 12.6% 22.2%

These differences aside, there is little to suggest that there was much optimism

about finding any successful approach to end the conflict.

Qualitative findings

While numbers are useful in summarizing how R2P was evaluated by the news-

papers, in order to produce a fuller picture of how R2P was seen as impacting the

international reaction to the crisis it is necessary to address some of the arguments

and positions opinion writers in the two papers adopted on the issue.

The first year: 2011

During the first year of the war, the Post’s opinion commentary centred on the

relevance of R2P and the Arab Spring. Concern was expressed about what a post-

Assad Syria might look like, as well as what the likely outcome of the Arab Spring

in general might be. Initially, the paper’s position with respect to the role of the

international community in the conflict was ambiguous. On the one hand, George

Jonas specifically warned against a ‘‘Libyan-style’’ intervention,12 while on the

other, an editorial praised international support for the rebel cause against the

Libyan dictator.13 The one editorial that dealt directly with the UN conveyed

the strong impression that nothing useful could be expected from the

organization.14

Globe opinion writers focused on the connections between NATO’s Libyan

operation and the possibility of a replication of it in Syria. On this the dominant

theme was that the application of the R2P doctrine was unlikely and probably

unwise for two reasons: the perceived mandate excesses in Libya, and the fact that

a variety of factors made the Syrian situation far more difficult than the Libyan

one.

With respect to the first of these, a June editorial argued that NATO’s ‘‘over-

stretched interpretation—and application’’ of the Security Council’s mandate in

12. George Jonas, ‘‘The spring of my Arab discontent,’’ National Post, 30 March 2011, A14.

13. Editorial, ‘‘Shades of Versailles,’’ National Post, 31 August 2011, A12.

14. Editorial, ‘‘Honouring Syria’s butchers,’’ National Post, 28 April 2011, A16.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

440 International Journal 71(3)

Table 3. Optimism vs. pessimism regarding possible R2P responses, by newspaper (percent-

age of total opinion items; ambiguous items omitted).

Globe and Mail National Post Total

N ¼ 84 N ¼ 83 N ¼ 167

Optimistic Pessimistic Optimistic Pessimistic Optimistic Pessimistic

Responses

Diplomacy 19.0% 21.4% 3.6% 20.5% 11.4% 21.0%

Arming the opposition 2.4% 10.7% 2.4% 4.8% 2.4% 7.8%

No-fly zone 6.0% 10.7% 6.0% 3.6% 6.0% 7.2%

Military action 7.1% 22.6% 4.8% 15.7% 6.0% 19.2%

Libya ‘‘undermin[ed] . . . the international community’s attempts to respond to the

bloodshed and repression in Syria.’’ Russia, among others, felt betrayed by

NATO’s ‘‘mission-creep’’ operations.15 Moreover, as an August editorial added,

‘‘the NATO nations that took part in the Libyan intervention . . . have no appetite

for another such mission so soon.’’16

The differences between Syria and Libya and the near impossibility of a

successful military intervention in the former were explained in detail by professors

Heather Roff and Bessma Momani. Syria was, for instance, more densely popu-

lated than Libya; its territory was mountainous rather than desert; and it possessed

a much stronger military. It was also further away from NATO’s bases in Europe.

Finally, in Syria there was ‘‘no identifiable rebel group occupying and controlling

territory.’’ Roff and Momani concluded that ‘‘unless Western powers . . . are pre-

pared for an on-the-ground invasion, we will continue to merely deplore what the

Syrian regime is doing against its own people.’’17

The second year: 2012

Early in 2012, the Post reprinted an editorial from the Wall Street Journal that

pushed for greater US action. Claiming that the US had provided most of the

‘‘firepower’’ seen as critical to the removal of Qaddafi in Libya, the editorial

proposed ‘‘another coalition of the willing’’ and pointed to the ‘‘American

folly . . . in giving the UN any ability to stop an anti-Assad coalition that includes

the Turks, all of non-Russian Europe, the U.S. and the Arab world.’’ It added that

‘‘a no-fly zone above Syria also shouldn’t be ruled out.’’18

15. Editorial, ‘‘Too little and too much,’’ Globe and Mail, 21 June 2011, A16.

16. Editorial, ‘‘No easy exit,’’ Globe and Mail, 29 August 2011, A10.

17. Heather Roff and Bessma Momani, ‘‘The tactics of intervention: Why Syria will never be Libya,’’

Globe and Mail, 25 October 2011, A17.

18. Wall Street Journal, ‘‘Another coalition of the willing, anyone?’’ National Post, 7 February 2012,

A12.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Najem et al. 441

In addition, based on new arguments, the Post continued to develop its position

that international intervention in Syria was a mistake. First, the nature of the anti-

government forces came under greater scrutiny and comparisons with the Assad

regime were offered. In this context, Marni Soupcoff observed that ‘‘the rebels’

supporters, which include al-Qaeda and Hamas, are potentially just as threatening

to human rights and stability as Assad himself—perhaps even more so.’’ Brutal and

unappetizing as Assad was, she wondered if the best alternative for the world might

not be ‘‘standing by and not doing very much.’’19 The Post also endorsed this

position editorially on 26 July: ‘‘It is not entirely clear that, overall, it is in

Western interests for Mr. Assad to go.’’ One of the reasons for that was the pres-

ence of ‘‘foreign terrorists, Islamic extremists and al-Qaeda zealots’’ in the rebel

ranks, and the other was the likelihood of full-scale civil war if he were to be forced

from office.20

Second, the issue of Syria’s chemical weapons enhanced doubts concerning the

desirability of the anti-government groups. As one editorial asked, ‘‘would we

prefer that these weapons fall into the hands of an ill-defined agglomeration of

armed insurgents, whose only shared interest is in seizing Assad’s power for them-

selves?’’21 George Jonas described this as the worst possible scenario.22 Other argu-

ments were also advanced editorially in support of the ‘‘hands off’’ position. Syria,

it was asserted, was going to fall apart ‘‘no matter what the rest of the world does,’’

and who wanted to be left trying to put the pieces together again? Moreover, half-

hearted interventions like the imposition of a so-called no-fly zone were dangerous

and had to be avoided because they inevitably led to deeper involvement.23 Lastly,

the discouraging example of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was

raised. If the rebels won, there would be long-term, continued chaos and violence in

Syria just as was still occurring in the DRC, and if Canada were to help the rebels

oust Assad, it would be tarnished by the ‘‘resultant butchery.’’ The editorial con-

cluded that ‘‘overall, the humanitarian arithmetic just doesn’t favour

intervention.’’24

Opinion writers in the Globe also developed new themes in 2012, mostly along

the same lines as their counterparts at the Post. There was a similar recognition

that a victory by the rebels was possibly a worse outcome than the continuation of

the Assad regime, and that, whatever the outcome, Syria was likely to remain

chaotic for the foreseeable future. The only hope for dealing with the situation

(albeit a faint and unclear one) lay with diplomacy, and any chance of that being

19. Marni Soupcoff, ‘‘UN impotence may be a blessing in Syria,’’ National Post, 12 June 2012, A8; see

also George Jonas, ‘‘From Suez to Syria: A half century of self-destructive Western foreign

policy,’’ National Post, 12 June 2012, A13; Jonathan Kay, ‘‘How we won in Syria: Barack

Obama played his cards exactly right—by doing virtually nothing,’’ National Post, 20 July 2012,

A12.

20. Editorial, ‘‘Careful what you wish for,’’ National Post, 26 July 2012, A16.

21. Ibid.

22. George Jonas, ‘‘Coming off our high horses,’’ National Post, 8 December 2012, A27.

23. Editorial, ‘‘Let Syria fall apart on its own,’’ National Post, 2 February 2012, A14.

24. Editorial, ‘‘Staying out of Syria,’’ National Post, 29 September 2012, A26.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

442 International Journal 71(3)

successful depended on regional players like Turkey and Iran, but most of

all Russia. Retired Canadian General Lewis MacKenzie argued that ‘‘the only

solution to the Syrian conflict goes through Moscow,’’ and he urged Canada to

‘‘convince Vladimir Putin to visit Damascus.’’ He was also cautious about vilifying

one side in the struggle while canonizing the other, claiming that ‘‘55 per cent of

Syrians support Assad.’’25 A Globe editorial supported the notion that Russia was

of crucial importance in bringing the killing to an end.26

The Globe also presented two opinion pieces in favour of Western intervention.

Senator Hugh Segal, invoking the pre-Second World War analogy of

Czechoslovakia, argued that ‘‘the price we pay for not acting is often far greater

than the actual price of deciding to act in the name of humanity.’’ He considered

Syria a test case for R2P and advocated the mounting of a Libyan-style no-fly zone,

despite the fact that this would be ‘‘hard, complex and messy.’’ Standing by and

watching, however, was ‘‘simply criminal.’’27 Professor Wesley Wark, by contrast,

was less concerned with humanitarian considerations than with realpolitik. He

maintained that if the West wished to be able to influence post-Assad Syria, it

had to become engaged in the conflict now; and that since ‘‘we have to accept

the fact that diplomacy has failed,’’ the only way this could be accomplished was

militarily.28

The third year: 2013

The final year of the study witnessed both continuity and change in the Post’s

opinion positions. The change involved some softening of the previously unflinch-

ing opposition to involvement in the Syrian tragedy, brought about primarily by

the issue of chemical weapons and what should be done about them.

In January 2013, Middle East Forum analyst Gary Gambill offered a spirited

rebuttal to pro-interventionists’ frequent tendency to attribute the deterioration of

the Syrian situation to American failure to intervene militarily on the side of the

rebels at an early stage. He maintained that ‘‘whatever America’s failings . . . they

cannot be shown to have decisively impacted the trajectory of the conflict once it

started.’’29 Senator Segal, however, reiterated the pro-intervention case, arguing

that ‘‘the absence of meaningful Western intervention early on in the conflict

made . . . [the deterioration of the situation] . . . practically inevitable.’’ Moreover,

he claimed, ‘‘a coalition composed of Arab and NATO countries could still inter-

vene decisively with a targeted air campaign,’’ augmented by the deployment

of ‘‘Western special forces units.’’ He saw the issue as a moral one à la R2P,

but also, given the threat of chemical weapons use, a practical national

25. Lewis MacKenzie, ‘‘The road to Damascus goes through Moscow,’’ Globe and Mail, 22 February

2012, A17.

26. Editorial, ‘‘Syrian peace begins in Moscow,’’ Globe and Mail, 29 May 2012, A14.

27. Hugh Segal, ‘‘We must act now in Syria or pay later,’’ Globe and Mail, 22 June 2012, A13.

28. Wesley Wark, ‘‘How to end the fighting in Syria,’’ Globe and Mail, 19 July 2012, A13.

29. Gary Gambill, ‘‘Don’t blame the U.S. for Syrian strife,’’ National Post, 14 January 2013, A8.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Najem et al. 443

interest matter: ‘‘This is no longer about our moral responsibility to protect Syria’s

helpless citizens. It’s about protecting our allies, and ultimately, ourselves.’’30

Segal was neither the first nor the last to focus on the chemical weapons issue,

even before they were actually used. In August 2012 US President Obama had

drawn a ‘‘red line,’’ warning that their use would trigger unspecified US responses.

David Frum interpreted this as an indication that the president ‘‘clearly wanted to

avoid intervening in Syria’’ and hinted that Assad probably saw it the same way.31

Editorially, the Post was critical of Obama’s red line on the basis that it increased

the possibility of an undesirable intervention: ‘‘it would be a mistake for Mr.

Obama to now send U.S. warplanes simply for the sake of superpower pride.’’32

An editorial in mid-June included pro-intervention quotes from US Senator John

McCain: ‘‘For us to sit by, and watch these people being massacred, raped and

tortured in the most terrible fashion, meanwhile, the Russians are all in, Hezbollah

is all in, and we’re talking about giving them more light weapons? It’s insane.’’33

This represents clear pro-intervention framing and, in that it appeared in an edi-

torial, certainly implies a rethinking of the paper’s earlier position. McCain went

on to propose a ‘‘no-fly zone’’ which he believed could be established and main-

tained ‘‘without risking a single American airplane.’’ While not actually endorsing

McCain’s position, the editorial pointed out that with respect to Western foreign

policy ‘‘there is a great distance between its actions and rhetoric,’’ and one can

assume the paper was looking for a change in the former rather than the latter.34

The actual use of chemical weapons on a civilian neighbourhood of Damascus

on 21 August changed significantly the direction of the debate. Given the Obama

red line, commentary quickly focused on whether and how the US should respond

to this serious development. Post columnist Matt Gurney led off by arguing that

Syria’s chemical weapons should have been destroyed nine months previously, as

soon as their likely deployment had been detected, because that would have wea-

kened whoever won the civil war by denying the victor their use. Gurney further

argued that indeed, they should still be destroyed.35 Even as staunch an anti-

interventionist as George Jonas left a small window open for an international

military response. While repeating his disdain for R2P (placed ‘‘in a class with

the ‘White Man’s Burden’’’) he observed, ‘‘when tyrants get too murderous,

when they start gassing their own citizens, we may get disgusted, as nations and

individuals. Tyrants should be careful not to make us lose our temper.’’36

Other commentators reprised arguments both for and against intervention.

Irwin Cotler presented the classic pro-intervention case based on R2P: ‘‘We must

30. Hugh Segal, ‘‘Intervene in Syria to protect ourselves,’’ National Post, 13 March 2013, A16.

31. David Frum, ‘‘Testing President Obama’s red lines on Syria,’’ National Post, 19 January 2013,

A24.

32. Editorial, ‘‘The West’s humanitarian mission in Syria,’’ National Post, 14 May 2013, A12.

33. As quoted in Editorial, ‘‘The West’s non-existent Syria policy,’’ National Post, 18 June 2013, A12.

34. Ibid., A12.

35. Matt Gurney, ‘‘Destroy Syria’s chemical weapons,’’ National Post, 23 August 2013, A14.

36. George Jonas, ‘‘White man’s burden 2.0: Why is it the West’s job to help Syrians from different

sects share the same country?’’ National Post, 31 August 2013, 21.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

444 International Journal 71(3)

reaffirm and reassert the moral and juridical imperative of the Responsibility to

Protect (R2P) doctrine.’’ Citing a UN report in June indicating that ‘‘war crimes

and crimes against humanity have become a daily reality,’’ he argued that ‘‘if mass

atrocities in Syria are not a case for R2P, then there is no R2P.’’37 Jonathan Kay

responded directly to Cotler by maintaining that ‘‘R2P has been dead for a while,’’

and that ‘‘ordinary voters do not want to see their sons’ blood spilled, or even their

tax dollars spent, to protect the dignity of an acronym.’’38

An opinion article by Bill Keller of the New York Times urged the Obama

administration ‘‘to persuade Congress, and the American public, that the U.S.

still has an important role to play in the world, and that sometimes you have to

put some spine in your diplomacy.’’ He favoured ‘‘calibrated intervention to shift

the balance in Syria’s civil war,’’ but given the ‘‘deep isolationist mood’’ into which

the country had fallen (comparable, he thought, to that faced by Franklin

Roosevelt during the early stages of the Second World War), he was not optimistic

that it would be undertaken.39

The Globe’s opinion material during 2013 can be characterized by two trends.

On the one hand, the paper’s editorial position early in the year came down more

firmly in favour of some sort of Western intervention, calling first for arming of the

opposition forces. This continued over the summer with support for a no-fly zone

and finally ended up deeply suspicious of the chemical weapons agreement that

took US air strikes (which the paper supported) off the table. On the other hand,

the Globe continued to present a range of opinion pieces which revealed no con-

sistent line with respect to whether the use of force by the international community

would be beneficial or harmful.

The first 2013 Globe editorial conveyed a sense of urgency not seen earlier:

‘‘The Syrian civil war has reached a point at which the international

community—that is to say the world’s responsible powers—needs to take a more

active hand, still with caution, favouring carefully selected insurgent groups that are

not Salafist, and have no affinities to al-Qaeda.’’ Such an ‘‘active hand’’ included

arming the anti-government forces by ‘‘supplying equipment, such as surface-to-air

missiles, to certain opposition groups.’’ The motivation for such a policy was that

the Assad regime was likely to fall and that in the resulting chaos ‘‘a group such as

Jabhat al-Nusra, a Syrian group affiliated to the Iraqi factions that are in turn

aligned with al-Qaeda, could well find and keep a foothold.’’ Even more critical

was the judgment that if Assad resorted to the use of chemical weapons, ‘‘foreign

intervention would become almost inevitable and indeed morally desirable.’’40

A mid–March opinion article by Paul Heinbecker endorsed the use of military

force, albeit very circumspectly. He suggested that an intervention could be accom-

plished by establishing ‘‘safe havens and no-fly zones,’’ described as ‘‘limited but

viable alternatives.’’ However, keeping ‘‘Western boots’’ out of Syria was a priority

37. Irwin Cotler, ‘‘Syrians are dying while the world dithers,’’ National Post, 31 August 2013.

38. Jonathan Kay, ‘‘R2P is no basis for bombing Syria,’’ National Post, 3 September 2012, A12.

39. Bill Keller, ‘‘America’s new isolationism,’’ National Post, 17 September 2013, A13.

40. Editorial, ‘‘Pitfalls, chaos and terrorism,’’ Globe and Mail, 2 January 2013, A12 (italics added).

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Najem et al. 445

because ‘‘intervention fatigue’’ was widespread in ‘‘financially strapped and dis-

tracted Washington and Europe.’’ In such circumstances Canada was urged ‘‘to

accept a greater share of the lead.’’41

A Globe editorial toward the end of April opened commentary on the issue of

Syria’s chemical weapons in the context of the Obama-declared red line. It cited US

evidence, confirmed by British and French intelligence, that ‘‘Syria is probably

using nerve gas on a small scale.’’ Obama was urged to give ‘‘some practical sub-

stance to his words, in such a way as to protect Syrian citizens while not putting

Islamic extremists in power.’’42

Globe foreign affairs reporter Campbell Clark assessed the May House of

Commons emergency debate on Syria and concluded that there wasn’t much to

show for it: ‘‘no vote on what steps to take, no call to back military intervention or

a no-fly zone or to arm rebels.’’ While Ottawa’s reluctance to back the rebels

stemmed from the presence of ‘‘extremists in their midst,’’ Clark pointed out

that in reality ‘‘there is no prospective military mission to join.’’43

In an opinion article toward the end of May, Anne-Marie Slaughter, former

director of policy planning for the US State Department, criticized President

Obama for timidity in not pursuing a military option, and argued the case for

intervention. She claimed that at least a credible threat of military force on the

part of US was required to get Assad to negotiate a settlement.44

While conceding that ‘‘reasons for not intervening militarily are not trivial,’’

Paul Heinbecker pointed out that ‘‘not acting in Syria is far from cost-free.’’ Chief

among these costs were the strengthening of Iran and Hezbollah and the weakening

of the United States. Heinbecker proposed the creation of no-fly zones, a solution

that would not stop the killing and was not without risks, but one that ‘‘would

diminish Mr. al-Assad’s capability to visit vast destruction on his citizens by air.’’ It

was noted that ‘‘Canada has the capability to contribute . . . [but]. . . if it doesn’t

want to do so, it should not impede others who do.’’45

Former diplomat Derek Burney and academic Fen Osler Hampson took the

opposite view, advancing ‘‘five reasons to stay out of Syria’’: an untrustworthy

opposition, a possibility of conflict escalation, a worsening of relations with Russia,

no end to the conflict with the removal of Assad, and Western democracies’ simply

not having ‘‘the stomach for protracted, inconclusive military gambits.’’ Canada

was not seen to ‘‘have a dog in this fight . . . [and] . . . should not be stoking its fires

or trying to pick winners.’’46

Lewis MacKenzie was unimpressed with no-fly zones, a concept that emerged

following the first Gulf War with the simple warning to Iraqi pilots: ‘‘Don’t fly or

41. Paul Heinbecker, ‘‘Heed the lessons of Iraq,’’ Globe and Mail, 15 March 2013, A15.

42. Editorial, ‘‘The reddening line,’’ Globe and Mail, 26 April 2013, A14.

43. Clark Campbell, ‘‘All urgency, no action in Syria debate,’’ Globe and Mail, A8.

44. Anne-Marie Slaughter, ‘‘Going to school in Syria,’’ Globe and Mail, 29 May 2013, A15.

45. Paul Heinbecker, ‘‘Every day, the cost of inaction grows,’’ Globe and Mail, 18 June 2013, A15.

46. Derek Burney and Fen Hampson, ‘‘Five reasons to stay out of Syria,’’ Globe and Mail, 19 June

2013, A15.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

446 International Journal 71(3)

you’re going to die.’’ By 1999, in the Serbia–Kosovo conflict no-fly zones took on a

different meaning. Although the Security Council had not authorized the use of

force, NATO used the no-fly zone concept to launch ‘‘an all-out bombing cam-

paign against the infrastructure of the former Yugoslavia.’’ In Libya, a no-fly zone

had been authorized by the Security Council and MacKenzie argued that Russia

and China were ‘‘truly duped’’ into thinking they were approving something along

the lines of the limited application seen in Iraq. Instead, NATO was as aggressive

as it had been in Kosovo, commencing ‘‘all-out attacks on Libya’s aircraft on the

ground, airfields, command-and-control centres, supply depots, military units and

so on.’’ As for Syria, MacKenzie saw no way Russia and China would again be

fooled. Furthermore, while NATO might be able to mount a successful no-fly zone,

he argued that it ‘‘would not be wise’’ for Canada to sign on.47

As with the Post, the supposed use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime

in August opened a new chapter in the debate regarding what the inter-

national community should do, and occasioned an immediate Globe editorial

that argued strongly for a military response that went well beyond the creation

of a no-fly zone: ‘‘The message needs to be made clear that the world will not

tolerate the use of chemical weapons.’’ It was argued that ‘‘Syria must pay a

price.’’48

Former Canadian cabinet ministers Lloyd Axworthy and Allan Rock cham-

pioned the 1999 NATO mission in Kosovo ‘‘as an appropriate precedent . . . [with

R2P] . . . to be used as the basis for action in Syria.’’ In that Russia would veto any

Security Council authorization for the use of force, the mission would of necessity

fall to ‘‘a coalition of countries prepared to take action,’’ and President Obama was

reportedly ‘‘looking to Kosovo as a model in Syria.’’ Axworthy and Rock called

upon ‘‘friends, allies, all those who seek a world of justice to urge him on, and offer

their support.’’49

A second editorial following the 21 August attack appeared to be not quite as

enthusiastic in its endorsement of military action. First it noted that ‘‘the consensus

is that this monstrous act must not go unanswered,’’ but what was missing was a

parliamentary debate to consider ‘‘the full range of options available to Canada

and its allies, not to mention the degree of Canada’s participation in what now

appears to be an inevitability.’’50 In early September, Jeffrey Simpson joined the

debate on the side of caution. He questioned why the US in particular would want

to be drawn into ‘‘a civil conflict of almost unfathomable complexity,’’ and whether

there was any possibility that air strikes could be effective when the Syrian gov-

ernment ‘‘had plenty of warning to disperse its assets.’’ He also questioned whether

there was in fact ‘‘another coalition of the willing’’ ready to step up; and if

there were, it certainly would not be NATO. Most notably, he dismissed the

47. Lewis MacKenzie, ‘‘Why this strategy won’t fly in Syria,’’ Globe and Mail, 25 June 2013, A13.

48. Editorial, ‘‘Red line crossed,’’ Globe and Mail, 23 August 2013, A10 (italics added).

49. Lloyd Axworthy and Allan Rock, ‘‘Intervene in Syria? Look to the ‘Kosovo model,’’’ Globe and

Mail, 27 August 2013, A13.

50. Editorial, ‘‘Parliament needs to debate war,’’ Globe and Mail, 29 August 2013, A12.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Najem et al. 447

Kosovo analogy: ‘‘by bombs alone Syria’s hellish war will not end.’’51 In a second

piece three days later, Simpson again called for restraint, maintaining that ‘‘the

United States, with support from Canada, is about to enter [the civil war] with only

the vaguest ideas of what intervention will or should bring.’’52

Another opinion article by Axworthy and Rock appeared between Obama’s

decision to seek congressional approval for military action and Putin’s proposal

for destroying Syria’s chemical weapons. It referred to ‘‘‘our’ collective failure,’’

and, with the exception of Canada, no one escaped scathing condemnation. The

UN led the list, and its Secretary-General in particular was criticized because ‘‘his

recent statements fail to reflect the underlying principle of R2P’’; and he had

chosen ‘‘to wring his hands and leave the immense moral authority of his office

untapped.’’53

The Globe’s final editorial in our study expressed skepticism about whether the

agreement to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons ‘‘will prove effective.’’ In any event

it argued that ‘‘Western powers must remain tenacious in pressing Russia and the

Syrian government to fulfill their end of the chemical-weapons bargain,’’ and if

there were signs of ‘‘bad faith’’ in carrying out the agreement, the use of force in the

form of ‘‘limited military air strikes should be revisited.’’54

Conclusions

What is perhaps most notable about the dominant orientation of the Globe and the

Post with regard to the Syrian crisis down to August 2013 is that both arrived at

roughly the same position despite radically different evaluations of R2P. The Post

was more adamantly negative about physical involvement in the conflict than the

Globe, but neither could be characterized as promoting a ‘‘will to intervene’’ by

either Canada or the international community. For the Post’s editorial board and

the majority of its opinion writers, R2P was more than irrelevant; it was a flawed

concept that should never have seen the light of day. In contrast, a majority of

Globe opinion supported the doctrine in principle but argued that its effectiveness

had been seriously compromised by misuse by NATO in Libya; hence it could not

be applied in Syria for political reasons. However, following the use of chemical

weapons in August 2013, the Globe supported a military response while avoiding

the problem of obtaining UN Security Council authorization.

As for the future of R2P, the debate continues. Aidan Hehir and Robert Murray

concluded that ‘‘R2P has demonstrably failed’’ and claimed that the doctrine

should be replaced by ‘‘a new legal architecture’’ to do what R2P failed to do.55

51. Jeffrey Simpson, ‘‘Syria is not a test of U.S. leadership,’’ Globe and Mail, 4 September 2013, A13.

52. Jeffrey Simpson, ‘‘Intervention is easier said than done,’’ Globe and Mail, 7 September 2013, F2.

53. Lloyd Axworthy and Allan Rock, ‘‘Syrians suffer ‘our’ failure,’’ Globe and Mail, 10 September

2013, A13.

54. Editorial, ‘‘Chemical weapons and hard diplomacy,’’ Globe and Mail, 17 September 2013, A12.

55. Aidan Hehir and Robert Murray, ‘‘The need for post-R2P humanitarianism,’’

OpenCanada.ORG., 17 March 2015, http://opencanada.org/features/the-need-for-post-r2p-huma

nitarianism/ (accessed 20 April 2015).

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

448 International Journal 71(3)

To this Evan Cinq-Mars responded that ‘‘boiling R2P down to the use and poten-

tial abuse of military force in ‘hard cases’ is as inaccurate as it is self-

serving, . . . [and] . . . while there is much to be done to make R2P implementation

more effective and consistent . . . [it is] . . . far from dead.’’56 We side with the latter

position. Unfortunately, the sort of ‘‘boiling down’’ cited by Cinq-Mars tends to

characterize much analysis and criticism of R2P and overlooks the reality that the

doctrine was never intended for blanket application. That such mischaracterization

of R2P persists stands in the way of a reasoned evaluation of its effectiveness.

However that may be, since the end of the period focused on here, the Syrian

civil war has morphed into the regional conflict that many feared, thanks to the

brutal interventions of the radical terrorist group(s) known as the Islamic State of

Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which appears to have wide-spread Islamist territorial ambi-

tions. Various Western powers are, as of this publication, engaged in what are so

far limited forms of military confrontation with ISIS in both Syria and Iraq.57

While it is likely that ISIS began with more limited objectives focused on the

ousting of the Assad government, the current conflict is more than an extension

of that campaign; thus, Western military intervention is different from an effort to

protect the innocent from tyrannical brutality. Russia’s military intervention in

Syria in the fall of 2015 was also aimed at, purportedly, fighting ISIS. What is

going on in Syria and Iraq now is not, therefore, an affirmation of R2P, nor is it a

denial. R2P is simply not applicable to a barbaric, chaotic, multisided, and multi-

issue mélange. If the ISIS situation proves to be at all typical of what the future

holds, further debate on R2P’s life or death may itself be irrelevant.

Acknowledgement

The research reported in this article is part of a book-length, three-nation study of

press framing of the Syrian civil war: No Good Options: Syria, Press Framing and

the Responsibility to Protect is under contract for publication with Wilfrid Laurier

University Press.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or

publication of this article.

56. Evan Cinq-Mars, ‘‘In support of R2P: No need to reinvent the wheel,’’ OpenCanada.ORG., 18

March 2015, http://opencanada.org/features/in-support-of-r2p-no-need-to-reinvent-the-wheel/

(accessed 20 April 2015].

57. The Canadian government under Stephen Harper joined Western efforts against ISIS, but

Canadian participation was withdrawn by the Liberal government of Justin Trudeau. It is too

early to tell whether the new government will treat the Syrian conflict within the context of liberal

internationalism.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Najem et al. 449

Author Biographies

Tom Pierre Najem is associate professor of political science at the University of

Windsor, where he served as department head from to 2002 to 2012. His latest

publications include Track Two Diplomacy and Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Old City

Initiative (co-editor, 2016), and Africa’s Deadliest Conflict: Media Coverage of the

Humanitarian Disaster in the Congo and the United Nation’s Response, 1997–2008

(with Walter Soderlund, Don Briggs, and Blake Roberts, 2012).

Walter C. Soderlund is professor emeritus in the Department of Political Science at

the University of Windsor. He has a longstanding interest in intervention and

international communications and is the author of Media Definitions of Cold

War Reality (2001) and Mass Media and Foreign Policy (2003) and co-author of

several other books.

E. Donald Briggs is professor emeritus of political science at the University of

Windsor specializing in international relations and African politics. Among his

publications are Africa’s Deadliest Conflict: Media Coverage of the Humanitarian

Disaster in the Congo and the United Nations Response, 1997–2008 (with Walter

Soderlund, Tom Najem, and Blake Roberts, 2012) and, with Walter Soderlund,

The Independence of South Sudan: The Role of Mass Media in the Responsibility to

Protect (2014). For many years he was the coordinator of the World University

Service Canada program at the University of Windsor, which sponsored 15 refugee

students from conflict-ridden countries in Africa to Canada.

Sarah Cipkar recently completed graduate work at the University of Windsor. She

worked as a research assistant to the book-length study on media coverage of

international intervention in the Syrian conflict. Sarah was instrumental in finding,

retrieving, cataloguing, and organizing the material that forms the data on which

the quantitative and qualitative research of the book is based.

This content downloaded from

194.95.59.195 on Wed, 04 May 2022 19:38:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Practical Wisdom - The Right Way To Do The Right Thing - PDFDocument5 pagesPractical Wisdom - The Right Way To Do The Right Thing - PDFChauhan RadhaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Christian UniversityDocument41 pagesPhilippine Christian UniversityJustine IraNo ratings yet

- Was R2P A Viable Option For Syria? Opinion Content in The Globe and Mail and The National Post, 2011-2013Document17 pagesWas R2P A Viable Option For Syria? Opinion Content in The Globe and Mail and The National Post, 2011-2013intanNo ratings yet

- The Responsibility To Protect Doctrine Expectations and RealityDocument3 pagesThe Responsibility To Protect Doctrine Expectations and RealityEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- The Future of Global Affairs Managing Discontinuity Disruption and Destruction 1St Ed Edition Christopher Ankersen Full ChapterDocument68 pagesThe Future of Global Affairs Managing Discontinuity Disruption and Destruction 1St Ed Edition Christopher Ankersen Full Chapterisaac.flores643100% (6)

- The Future of Global Affairs Managing Discontinuity, Disruption and DestructionDocument346 pagesThe Future of Global Affairs Managing Discontinuity, Disruption and DestructionMuhammad ShahzaibNo ratings yet

- Geography Case StudyDocument7 pagesGeography Case StudyZara AhmedNo ratings yet

- Applying A Disarmament Lens To Gender, Human Rights, Development, Security, Education and Communication: Six EssaysDocument75 pagesApplying A Disarmament Lens To Gender, Human Rights, Development, Security, Education and Communication: Six Essaysdamp1rNo ratings yet

- Coping With Crisis: Nuclear Weapons: The Challenges AheadDocument23 pagesCoping With Crisis: Nuclear Weapons: The Challenges AheadLaurentiu PavelescuNo ratings yet

- In Support of R2P - No Need To Reinvent The Wheel - CINQ-MARS, EvanDocument3 pagesIn Support of R2P - No Need To Reinvent The Wheel - CINQ-MARS, EvanLucasbelmontNo ratings yet

- In Whose Name?Document68 pagesIn Whose Name?Jeff PragerNo ratings yet

- Kimber Feminist AdvocacyDocument11 pagesKimber Feminist AdvocacypaulNo ratings yet

- The Interplay Between Terrorism NonstateDocument38 pagesThe Interplay Between Terrorism NonstateCaio CesarNo ratings yet

- Understanding Social MediaDocument6 pagesUnderstanding Social MediaGulka TandonNo ratings yet

- Multilateralism and Public Support For Drone StrikesDocument9 pagesMultilateralism and Public Support For Drone StrikesOrvilleNo ratings yet

- Discontinuities and Distractions-Rethinking Security For The Year 2040Document39 pagesDiscontinuities and Distractions-Rethinking Security For The Year 2040Felipe Serrano ArdilaNo ratings yet

- NAVIGATING COMPLEXITY: Climate, Migration, and Conflict in A Changing WorldDocument44 pagesNAVIGATING COMPLEXITY: Climate, Migration, and Conflict in A Changing WorldThe Wilson Center100% (1)

- Exhausted by Resilience: Response To The CommentariesDocument8 pagesExhausted by Resilience: Response To The CommentariesopondosNo ratings yet

- The Independence of South Sudan: The Role of Mass Media in the Responsibility to PreventFrom EverandThe Independence of South Sudan: The Role of Mass Media in the Responsibility to PreventNo ratings yet

- Journal of Conflict Resolution 1972 Azar 183 201Document20 pagesJournal of Conflict Resolution 1972 Azar 183 201Kingsley ONo ratings yet

- Africa’s Deadliest Conflict: Media Coverage of the Humanitarian Disaster in the Congo and the United Nations Response, 1997–2008From EverandAfrica’s Deadliest Conflict: Media Coverage of the Humanitarian Disaster in the Congo and the United Nations Response, 1997–2008No ratings yet

- 1.5 A More Secure WorldDocument9 pages1.5 A More Secure WorldMahfus EcoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Un PeacekeepingDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Un Peacekeepinghnpawevkg100% (1)

- Post-War Reconstruction: Concerns, Models and Approaches: Docs@RwuDocument59 pagesPost-War Reconstruction: Concerns, Models and Approaches: Docs@RwuIlda DobrinjicNo ratings yet

- Human Security Concept and MeasurementDocument64 pagesHuman Security Concept and MeasurementStuntman Mike100% (1)

- Report Programma Di Sviluppo Delle Nazioni Unite (UNDP)Document320 pagesReport Programma Di Sviluppo Delle Nazioni Unite (UNDP)Davide FalcioniNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Security EssayDocument11 pagesGlobalization and Security EssayLiza VeysikhNo ratings yet

- International Relations Term Paper IdeasDocument7 pagesInternational Relations Term Paper Ideasc5rggj4c100% (1)

- Humanitarian Intervention - Is It An Emerging ResponsibilityDocument42 pagesHumanitarian Intervention - Is It An Emerging ResponsibilitymofocaNo ratings yet

- World PoliticsDocument37 pagesWorld PoliticsAnonymous GKPCQIcmXSNo ratings yet

- Un Negocio Arriesgado The Lancet Planetary Health 02 2024Document1 pageUn Negocio Arriesgado The Lancet Planetary Health 02 2024Fernando Franco VargasNo ratings yet

- Wiley The International Studies AssociationDocument39 pagesWiley The International Studies AssociationIonela BroascaNo ratings yet

- IR Notes-Final 3Document283 pagesIR Notes-Final 3iusamashaiq10No ratings yet

- The Origins and Evolution of Responsibility To Protect at The UNDocument20 pagesThe Origins and Evolution of Responsibility To Protect at The UNsalimaNo ratings yet

- Fake News On COVID-19 in Indonesia: Valerii Muzykant Munadhil Abdul MuqsithDocument17 pagesFake News On COVID-19 in Indonesia: Valerii Muzykant Munadhil Abdul Muqsithferdyanta_sitepuNo ratings yet

- Organizing The Future of HumanityDocument20 pagesOrganizing The Future of HumanityAnthony JudgeNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal and Business Plan: 2016-19Document38 pagesProject Proposal and Business Plan: 2016-19Open Briefing100% (1)

- Reporte Mundial de Riesgos - 2019Document71 pagesReporte Mundial de Riesgos - 2019Daniel Esteban MuñozNo ratings yet

- Framing Social Conflicts in News Coverage and Social MediaDocument26 pagesFraming Social Conflicts in News Coverage and Social MediaIvanNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Media and TerrorismDocument9 pagesDissertation Media and TerrorismInstantPaperWriterSingapore100% (1)

- American J Political Sci - 2021 - Blair - When Do UN Peacekeeping Operations Implement Their MandatesDocument17 pagesAmerican J Political Sci - 2021 - Blair - When Do UN Peacekeeping Operations Implement Their MandatesJu MaNo ratings yet

- 605 Pil SM0121032Document21 pages605 Pil SM0121032KunalNo ratings yet

- Building a New World Order: Sustainable Policies for the FutureFrom EverandBuilding a New World Order: Sustainable Policies for the FutureNo ratings yet

- GG Article p121 - 6Document33 pagesGG Article p121 - 6Akram IrmanNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Human Rights: The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries March 2018Document5 pagesGlobalization and Human Rights: The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries March 2018Ofarouk7No ratings yet

- HybridwarfareDocument23 pagesHybridwarfaremartin.prietoNo ratings yet

- Ihls Article p331 - 331Document17 pagesIhls Article p331 - 331Chinmay HarshNo ratings yet

- Sickness or Silence - Social Movement Adaptation To Covid-19Document23 pagesSickness or Silence - Social Movement Adaptation To Covid-19Jessica ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- ICRC CommunicationsDocument13 pagesICRC CommunicationsAsif Masood Raja100% (2)

- ACC416 - Case Study - Answer SheetDocument6 pagesACC416 - Case Study - Answer SheethamzaNo ratings yet

- 3924 HW Emerging Research TopicsDocument12 pages3924 HW Emerging Research TopicsДмитрий ДемидовNo ratings yet

- Global Catastrophic Risk Annual Report 2016 FINALDocument108 pagesGlobal Catastrophic Risk Annual Report 2016 FINALJayesh MulchandaniNo ratings yet

- Rand Mg304.SumDocument28 pagesRand Mg304.Sumirawan saptonoNo ratings yet

- Collective Foresight and Intelligence For SustainaDocument15 pagesCollective Foresight and Intelligence For SustainaBagas MuhammadNo ratings yet

- hdr2021 22overviewenpdf 2Document44 pageshdr2021 22overviewenpdf 2SamanDehnaviNo ratings yet

- Three Tweets to Midnight: Effects of the Global Information Ecosystem on the Risk of Nuclear ConflictFrom EverandThree Tweets to Midnight: Effects of the Global Information Ecosystem on the Risk of Nuclear ConflictNo ratings yet

- Meierandpuig FinalDocument28 pagesMeierandpuig FinalBianca BonnelameNo ratings yet

- COVID-19: Cosmopolitanism's Criticism and Proposals: Mahbi Maulaya and Nanda Blestri JasumaDocument21 pagesCOVID-19: Cosmopolitanism's Criticism and Proposals: Mahbi Maulaya and Nanda Blestri Jasumafaizalgamar99No ratings yet

- Science Disinformation in A Time of Pandemic: Christopher DornanDocument38 pagesScience Disinformation in A Time of Pandemic: Christopher DornanVictor StefanNo ratings yet

- Organic Solvent Solubility DataBookDocument130 pagesOrganic Solvent Solubility DataBookXimena RuizNo ratings yet

- Hand Book of Transport Mode Lling - : Kenneth J. ButtonDocument8 pagesHand Book of Transport Mode Lling - : Kenneth J. ButtonSamuel ValentineNo ratings yet

- Suraj Estate Developers Limited RHPDocument532 pagesSuraj Estate Developers Limited RHPJerry SinghNo ratings yet

- Applied Economics Module 3 Q1Document21 pagesApplied Economics Module 3 Q1Jefferson Del Rosario100% (1)

- 5 Leadership LessonsDocument2 pages5 Leadership LessonsnyniccNo ratings yet

- Lean Six Sigma Black Belt - BrochureDocument3 pagesLean Six Sigma Black Belt - BrochureDevraj NagarajraoNo ratings yet

- RMO 2016 Detailed AnalysisDocument6 pagesRMO 2016 Detailed AnalysisSaksham HoodaNo ratings yet

- Exercises No 1: Exercise 1Document6 pagesExercises No 1: Exercise 1M ILHAM HATTANo ratings yet

- Data Visualization With Power Bi - Tech LeapDocument63 pagesData Visualization With Power Bi - Tech LeapDurga PrasadNo ratings yet

- GSM System Fundamental TrainingDocument144 pagesGSM System Fundamental Trainingmansonbazzokka100% (2)

- CE230207 Copia WC Presentation FINALDocument47 pagesCE230207 Copia WC Presentation FINALIdir MahroucheNo ratings yet

- DixonbergDocument2 pagesDixonbergLuis OvallesNo ratings yet

- Revised 04/01/2021Document33 pagesRevised 04/01/2021Kim PowellNo ratings yet

- PFW - Vol. 23, Issue 08 (August 18, 2008) Escape To New YorkDocument0 pagesPFW - Vol. 23, Issue 08 (August 18, 2008) Escape To New YorkskanzeniNo ratings yet

- Diy Direct Drive WheelDocument10 pagesDiy Direct Drive WheelBrad PortelliNo ratings yet

- Samsung GT E1195Document50 pagesSamsung GT E1195RyanNo ratings yet

- WH2009 WaterHorseCatalogDocument132 pagesWH2009 WaterHorseCatalogAiko FeroNo ratings yet

- CityTouch Connect ApplicationDocument13 pagesCityTouch Connect ApplicationYerko Navarro FloresNo ratings yet

- Character Analysis of Lyubov Andreyevna RanevskayaDocument4 pagesCharacter Analysis of Lyubov Andreyevna RanevskayaAnnapurna V GNo ratings yet

- JD - Part Time Online ESL Teacher - Daylight PDFDocument2 pagesJD - Part Time Online ESL Teacher - Daylight PDFCIO White PapersNo ratings yet

- Basic Bible SeminarDocument45 pagesBasic Bible SeminarjovinerNo ratings yet

- Heat, Temperature, and Heat Transfer: Cornell Doodle Notes FREE SAMPLERDocument13 pagesHeat, Temperature, and Heat Transfer: Cornell Doodle Notes FREE SAMPLERShraddha PatelNo ratings yet

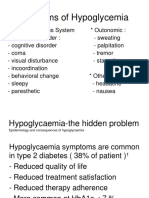

- Symptoms of HypoglycemiaDocument20 pagesSymptoms of Hypoglycemiakenny StefNo ratings yet

- Hydrogen EconomyDocument19 pagesHydrogen EconomyEdgar Gabriel Sanchez DominguezNo ratings yet

- A Burdizzo Is Used For: A. Branding B. Dehorning C. Castration D. All of The AboveDocument54 pagesA Burdizzo Is Used For: A. Branding B. Dehorning C. Castration D. All of The AboveMac Dwayne CarpesoNo ratings yet

- Common Service Data Model (CSDM) 3.0 White PaperDocument31 pagesCommon Service Data Model (CSDM) 3.0 White PaperЕвгения МазинаNo ratings yet

- F.Y.B.Sc. CS Syllabus - 2021 - 22Document47 pagesF.Y.B.Sc. CS Syllabus - 2021 - 22D91Soham ChavanNo ratings yet

- Runner of Francis Turbine:) Cot Cot (Document5 pagesRunner of Francis Turbine:) Cot Cot (Arun Kumar SinghNo ratings yet