Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 188.26.148.163 On Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 188.26.148.163 On Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

Uploaded by

Alex RădulescuOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 188.26.148.163 On Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 188.26.148.163 On Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

Uploaded by

Alex RădulescuCopyright:

Available Formats

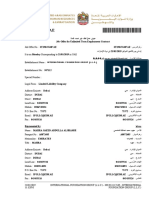

Federalist No.

10: Are Factions the Problem in Creating Democratic Accountability in

the Public Interest?

Author(s): Jack H. Knott

Source: Public Administration Review , December 2011, Vol. 71, Supplement to Volume

71: The Federalist Papers Revised for Twenty-First-Century Reality (December 2011),

pp. S29-S36

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Society for Public Administration

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41317414

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41317414?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wiley and American Society for Public Administration are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Public Administration Review

This content downloaded from

188.26.148.163 on Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Jack H. Knott

University of Southern California

Federalist No. 10: Are Factions the Problem in Creating

Democratic Accountability in the Public Interest?

Federalist No. 10 contains an optimistic view of the rights of minorities or that pass legislation that would Jack H. Knott is the Erwin and lone

Piper Dean Professor in the School of Policy,

national government's ability to fulfill its obligations not benefit the broadly defined public interest.

Planning, and Development at the Univer-

in the midst of what was, at the timey a small but sity of Southern California. His research

challenged nation. This essay Madison believed that the interests center on the impact of institutions

suggests that the founders did United States would have two and decision making processes on public

Madison believed that the policy, governmental and bureaucratic

not anticipate the pernicious interconnected advantages over

United States would have two other countries in control-

reform, and public management. He is a

effects of rent seeking corruption , fellow of the National Academy of Public

and repression of minorities, interconnected advantages over ling the potentially repressive

Administration.

E-mail: jhknott@usc.edu

and they failed to anticipate the other countries in controlling acts of majority factions. The

calamities associated with slavery. the potentially repressive acts first advantage is a republican

The essay asks about the role of form of government, in which

of majority factions. The first

government as a party machine, the legislative body consists

advantage is a republican of a small number of elected

a business , a policy process , and

a contractor and examines a form of government, in which representatives of the people.

variety of contemporary theories the legislative body consists The second advantage is that a

for explaining government of a small number of elected republican form of government

performance. representatives of the people. allows for a much larger size

country. Madison argues that

The second advantage is that a

elected representatives are more

republican form of government

the problem in public likely than the general popula-

Are the administration? political Inproblem

administration? Fed- factions in public In allows for a much larger size tion to include people who have

eralist No. 10, James Madison country. an interest in the public good.

addresses the issue of factions He also makes the case that

in a democratic republic. His the number of elected officials

argument consists of two parts: First, he argues that in a large country will be a smaller proportion of the

the causes of faction cannot be removed. Factions are population than in a small country, and hence each

rooted in the self-interests of individuals and groups. representative will represent a larger number of people

When self-interest is combined with the limited and and interests, giving each representative a broader

faulty rationality of human beings, political factions political perspective. But Madison thought that even

emerge that do not serve the broad public interest or if the representatives did not have the public inter-

that cause harm to the rights of other groups (Carey est in mind, the broad diversity of interests in a large

1995, 9-11; Epstein 2007, 64-66). Madison also country would make it difficult to aggregate interests

believed that the unequal distribution of property into a countrywide faction to repress minorities.

is the main source of factions, which, in turn, is a

major determinant of the political power structure of His analysis has two important limitations for answer-

a state (Ostrom 2008, 81). Madison argues, however, ing the question of this article. First, he could not

that the consequences of factions can be controlled. address the question of the importance of factions

In colonial America, he worried less about minority for public administration because, at the time of the

factions than majority ones. He reasoned that while a founding of the country, the federal government

minority faction might frustrate and delay the actions played a minor role in the economy and society, with

of the majority, it cannot prevent the majority from few public servants and a small bureaucracy. Sec-

working its political will. Consequently, his primary ond, while Madison's analysis profoundly predicted

concern focused on majority factions that repress the the potential success of a democratic republic in a

Are Factions the Problem? S29

This content downloaded from

188.26.148.163 on Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

very large country, it was overly optimistic about the potential for of the nineteenth century and extending in some measure into the

controlling the deleterious effects of factions on public policy. His twentieth century, public administration served as an arm of party

argument predicted accurately that America would avoid democratic patronage and public subsidy to political supporters.

dictatorship on a grand scale, such as a Napoleon Bonaparte, but

underestimated the variety and severity of rent seeking, corruption, The failure of the Constitution and the Federalists to address the is-

and repression of minorities perpetrated by majority and minority sue of slavery eventually led to the breakdown of the political system

political factions over the next two centuries. It also failed to foresee and civil war. Madison asserted that property is the primary cause

the calamitous impact of the system of slavery, which overwhelmed of the rise of factions that threaten the common good and violate

the plurality of other property interests and human rights (Epstein the rights of individuals and minority groups. Federalist No. 10

2007, 102-3). maintains that a republican form of representation and a large, di-

verse country would protect against these deleterious effects. Slavery,

The principles on which Madison based his thinking about de- however, represented a system of property rights that dramatically

mocracy and the public interest, however, offer a guide to how he reduced pluralism and diversity and divided the country into slave

would understand the role of public administration in a democratic and free states (Epstein 2007, 103-5). The attempt by the major-

republic, including the importance of political factions. His idea ity faction in the slave states to secede from the Union precipitated

that the countervailing interests in a large country could check each the Civil War. In the South, public administration served as the

other, especially in a republic with a separation of powers system, arm of repression of the enslaved minority, and during the war, the

is particularly relevant today. He also hinted that there could be a demands of the military dominated public administration. Despite

group of officials who have the public interest in mind more than these violent and calamitous events, in the immediate postwar pe-

the special interests or the general citizenry, thereby acting as a riod, public administration remained an arm of political patronage

counterweight to political faction (Epstein 2007, 87-88). and corruption by the political party in power.

How Important Are Factions to Public Administration? The Separation of Politics and Administration: Government as

Over the course of its history, the United States has had an uneasy Business

relationship between politics and public administration. Unlike By the 1 880s, public opposition to the extensive corruption, vio-

France and Germany, which were established with strong central lence, and inefficiencies of the political machines brought together a

bureaucracies and executive power, America began with a weak, coalition of political interests that advocated a separation of politics

decentralized government and a small bureaucracy. France and from administration. This coalition consisted of religious moralists,

Germany build their constitutions and state authority on public self-interested small business people, and Progressive Reformers

and administrative law, derived from the Napoleonic Code, which who wanted good, fair, and effective government (Knott and Miller

defines the public interest and public administrative practice. The 1987). From the 1880s to the 1940s, the Progressive and manage-

political philosophy of the Federalists, reflected in the U.S. Consti- rial movements in the United States and similar reform movements

tution, focused almost exclusively on the legislature and secondarily in Europe sought to drastically reform the party patronage system.

on the chief executive, with a particular interest in restricting execu- While Progressive reform focused on political processes such as the

tive authority. In addition, the United States adopted the British secret ballot and at-large electoral districts, it also sought to reform

common law legal system, which contains little formal guidance for public administration. Indeed, it saw the removal of the influence

public administrative practice. As a consequence, the relationship of political factions on public administration as central to its reform

between politics and public administration evolved politically over goals. The Progressives established the Civil Service Commission,

time, often in different directions, depending on the political coali- which introduced rules for merit hiring, promotion, and review. It

tion in power, or the dominant political movement in the country argued for neutral competence and the separation of politics and

able to exercise influence over institutional choices (Knott and administration (Wilson 1887). At the local level, city councils estab-

Miller 1987). lished independent commissions to oversee local economic develop-

ment, and the city councils hired professional city managers.

Public Administration and the Political Party: Government as

Party Machine Intellectually, during this period, public administration emerged

The election of President Andrew Jackson in 1 829 began the perva- as a profession and academic discipline (Kaufman 1967; Mosher

sive influence of political factions on public administration in the 1982), with the watershed establishment of the Bureau of Municipal

United States. While access to federal employment expanded to a Research in New York City in 1905. This was also the period of the

much broader class of citizens, beginning in this period and contin- development of masters degrees in public administration at major

uing into the post-Civil War era, party factions dominated public universities, starting with the University of Southern California in

administration through the patronage system, which affected public 1928, followed by Syracuse University and then Harvard University

administration in significant ways. Congress and state legislatures shortly thereafter. Parallel with the emergence of public admin-

ostensibly established public agencies to serve the public good, but istration, the scientific management movement in business and

in practice, administrative agencies often served party loyalists much engineering contributed to the growth in managerial studies and

better than the general citizenry. Public goods were private benefits operations research (Willoughby 1927). During the presidency of

for party members, groups, and businesses that supported the party. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the postwar era, several administrations

Even basic services at the local level, such as fire and police, were worked to establish unitary lines of command, greater managerial

readily available for party-dominated areas of the city but underpro- coordination, and organization of departments by function (Gulick

vided to those areas held by the party out of power. During much and Urwick 1937). Through the Office of Management and Budget,

S30 Public Administration Review • December 2011 • Special Issue

This content downloaded from

188.26.148.163 on Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the president sought to integrate management, planning, and number of political appointees, leading to politically top-heavy

budget processes (Schick 1966). departments, which, when combined with extensive contracting, led

to demoralization and decline in the federal service (Light 2008).

The Politics of Bureaucracy: Government as Policy Process

In the postwar period, several developments, both intellectually At the same time, while labor unions have declined precipitously

and in practice, produced a strong reaction against the separation in the private sector, public sector unions have grown and strength-

of administration from politics. Politically, the parties came to view ened. In many states, they represent a powerful political faction of

public administration differently based on two separate political their own that influences local political races for election to school

coalitions that sharply disagreed over the role of government and boards, city councils, and state legislatures (Moe 2005). In this

public administration in society. The dramatic expansion of public sense, public administration in the twenty-first century has evolved

agencies under Democratic administrations during the Great De- into the inverse of public administration as the arm of the political

pression and World War II, followed in the 1960s by the Great Soci- machine in the nineteenth century. Today, the political party is, in

ety expansion of the domestic role of the government, from health part, an arm of public administration.

care to social security to welfare, thrust public agencies and officials

into the center of the political debate over "big government." Re- Despite the tremendous growth in public administrative agencies

publican administrations under Presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald and the huge intellectual interest in government and bureaucracy in

Ford, and Ronald Reagan sought to increase the control by political the twentieth century, there has been a weakening of public admin-

appointees of public agencies and reduce the federal government s istration as a profession and an academic discipline (Kelman 2007).

domestic public bureaucracy, viewing federal public administrators As the understanding of public administration encompassed policy

as advocates for big government. The growth in public administra- process and cross-sector governance rather than public government,

tors and public agencies shifted to state and local government, while public administration programs faced growing competition from

the federal government concentrated on regulation, benefits pay- the fields of business administration, political science, law, econom-

ments, tax collection, macroeconomic policy, and the military. ics, public policy, and urban planning.

Intellectually, the behavioral movement in the social sciences at- How Important Are Factions Today?

tacked the mechanistic, structural, and legally based theories of pub- Today, the most powerful theories on political factions and repre-

lic administration (Simon 1947). Academics and practitioners came sentative government are found in political science and economics.

to recognize that public administration helped both to formulate This research has provided a convincing theoretical basis for criticiz-

as well as to implement policy and budgets and that these processes ing the representation function of the Congress as an effective way

inevitably involved political factions and coalitions (Allison, 1971; to control factions. These political economy studies do not focus

Pressman and Wildavsky 1973; Rourke 1984, 1992; Wildavsky specifically on public administration but on interest groups, political

1964). While illegal forms of corruption and patronage diminished parties, Congress, and the presidency, congruent with the focus of

and violence subsided as a result of Progressive reform, the practice the Federalist Papers. However, the implications of these theories

of public administration incorporated political goals and imple- for achieving an efficient and effective public administration are

mentation as before (Seidman 1970; Warwick 1979), illustrated significant.

dramatically by the account of the administrative leadership of Rob-

ert Moses in the development of New York City (Caro 1975). Yet Majority Rule Incoherence: The Arrow Paradox

the focus remained on the role of expertise and professionalism in The work of Arrow (1963) demonstrates that it is impossible to

the political process (as opposed to separate from it). The significant aggregate the disparate interests of a population in a way that satis-

role of the bureaucracy became a topic for extensive research and fies basic coherence and efficiency criteria. Different aggregation

academic discussion, with tensions shifting between agency capture or voting rules will present different problems. Policy deliberations

by interest groups (Bernstein 1955; Stigler 1971), the importance in Congress are accomplished by variations of majority rule, which

of bureaucratic routines (Downs 1967; Wilson 1989), bureaucratic introduces the problem of intransitivity in policy choice - there nor-

domination in the budget process (Niskanen 1971), bureaucratic mally will be a majority in Congress that prefers some other policy

representation (Meier 1975), bureaucratic leadership (Lewis 1980), to any policy actually selected by Congress.

and the impact and performance of public management (Meier and

OToole 1999). Intransitive choice is most inevitable in high-dimensioned policy

spaces. Distributional issues such as pork barrel spending, tariff

The Hollow State: Government as Contracting policy, weapons acquisition policy, military base closing, and taxa-

Eventually, both parties came to an anti-big government stance in tion are examples: each member of Congress may evaluate any given

varying degrees, with Republicans and Democrats supporting de- proposal on the basis of its distributional impact in his or her own

regulation, welfare reform, and efforts to "reinvent government" in district. This means that the House of Representatives will have

a less bureaucratic, more "market-like" form (Milward and Provan 435 dimensions of policy evaluation - and inevitable cycling. Every

2000). Administrations of both parties expanded the contracting of policy worked out by a given coalition can be attacked by a differ-

services to nonprofit and for-profit organizations for broad areas of ent coalition that can woo pivotal members of Congress to the new

government, from mental health services to military construction. coalition by more generous offers. What is more, this structure is so

As a consequence, the distinction between the public and private transparent that every member of Congress is aware that any coali-

sectors blurred considerably, with all three sectors involved in many tion is vulnerable. The implication, of course, is that the legislation

areas of societal problem solving. Both parties also expanded the that is produced in distributional cases, and sent to the bureaucracy

Are Factions the Problem? S31

This content downloaded from

188.26.148.163 on Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

for implementation, is the more or less arbitrary result of an inco- Moral hazard refers to the incentives that individuals have to engage

herent process. in actions that reduce the overall efficiency of the organization.

Members of a production team work together to produce a surplus.

Committee Influence: The Sen Paradox For example, the different branches of the military and its numerous

contractors mutually determine the level of benefits from the provi-

One implication of intransitive choice is that the agenda is extreme-

sion of the public good of defense. Holmstrom asks whether there

ly influential in determining the outcome. The fundamental agenda

control mechanism in Congress is the committee system, whichis any way to distribute the benefits from public good production

so that the benefits are exactly allocated among the team members

gives subgroups of Congress extraordinary ability to block or enact

legislation in particular domains of policy. This latter feature is a(budget balancing), and so that each team member finds that its

self-interest leads to a Pareto-optimal Nash equilibrium. Holmstrom

manifestation of decentralized decision making that makes it impos-

demonstrates that budget balancing is inconsistent with a Pareto-

sible to guarantee Pareto optimality in choice. Sen (1970) argues

optimal Nash equilibrium. The only way to eliminate moral hazard

that when aggregating individual preferences to the organizational

level, a decentralized organization must give up either coherenceamong

or team members is to pay the productive members of the team

and then allocate the residuals to passive actors outside the produc-

efficiency. The aggregation of decentralized power sometimes must

be an outcome that everyone agrees is inferior to one that couldtive process. This solution is institutionalized in the firm in the

be achieved by a more global administrative perspective (Ham-separation of productive members of the firm from owners (stock-

holders and members of the board of directors, who receive the

mond and Miller 1985, 8). A persistent example of inefficiencies

surplus in the form of profits). It is institutionalized in democratic

generated by decentralized agenda control is the agriculture price

forms of government in the separation of productive members of

support logroll, in which a variety of constituencies share benefits

the bureaucracy from the general citizenry, who receive the residual

that, unfortunately, do not exceed the costs imposed on a diffuse

and passive public. There can be little doubt that the system of benefits

farm of public good production.

price support programs has benefited from a decentralized system of

agenda control in which the self-interest of a variety of actors isEswaran

at and Kotwal (1984) show, however, that while this separa-

odds with the general welfare. tion of ownership makes efficiency possible, it does not eliminate

moral hazard altogether. The obstacle is now moral hazard in the

Biases in Representation form of rent seeking by subgroups of owners (in the case of firms)

Societal interests are not equally represented in the legislature. or citizens and interest groups (in the case of democracies). There

will be inevitably collusive arrangements between residual owners

Individual members of large group interests also cannot be excluded

(say legislators and particular interest group constituencies) and

from the benefits of the public good once it is provided by the legis-

productive members of the defense production system (say, contrac-

lature, which creates an incentive for free-riding (Olson 1977, 13).

Consequently, large, diffuse interests have a much more difficulttors) that will allow them to distribute more residual rents among

themselves at the expense of overall efficiency (Arnold 1979, 96). A

time organizing for political action than smaller, concentrated inter-

variety of actors are made better off by this rent-seeking behavior -

ests. This difficulty of organizing for political action can be over-

but the public benefits of military defense are diminished. There is

come in smaller groups by a privileged cluster of members whose

no natural alignment of interest between the residual owners and

gains from the good exceed the total cost (Olson 1977, 28). Large,

overall efficiency. It will always be possible to earn more rents from

diffuse groups also can overcome this collective action problem by

creating organizations that provide "by-products" to members in an the

inefficient scheme than from an efficient incentive scheme.

form of private goods (Olson 1977, 132).

Members of the legislature engage in this kind of political moral

Legislatures thus are more responsive to lobbying groups that (1) hazard when they allocate rents to firms or groups in their districts

that provide campaign funds and other assurances of reelection

further the interests of relatively small groups (e.g., auto producers),

(2) represent the interests of concentrated groups (e.g., farmers or

orthe potential for monetary reward upon leaving office. Interest

labor unions), and (3) provide "by-products" to its members ingroups

or- recognize the potential for receiving rents from the legis-

lature, and both sides succumb to this moral hazard by seeking to

der to channel pressure on particular issues (e.g., the National Rifle

maximize rents at the expense of social efficiency. There always will

Association). As a result, we cannot presume that elected officials

legislate in a way that best serves the public interest as a whole; be

ona private demand for government rent seeking: the short-term

the contrary, legislative outputs will systematically tend toward rent from government officials selling monopolies, licenses, access

gains

extraction by the most organized interests at the expense of the to public goods, and favorable regulation to private market actors

less

organized. are immense and benefit both public officials and private market

forces. In this sense, rent seeking in fact cannot be thought of as

Rent Seeking: The Political Moral Hazard Problem public or private - it is a transaction between public and private

actors.

While Olsen focuses on the incentives that private actors have to

lobby and seek benefits from government, Holmstrom (1982) and

Eswaran and Kotwal (1984) provide us with a way of thinking Holmstrom (1982) and Eswaran and Kotwal (1984) thus pr

about the mutual interaction between private interests and public an answer to the question posed at the beginning of this art

officials. The impossibility result by Holmstrom (1982) in "Moral Why are political factions an important problem for public a

Hazard in Teams" is an analysis of team production in firms; it can istration? The answer: political moral hazard inevitably accom

be applied broadly to any interactive social production, including the ability to extract rents from public goods production. D

public good decision making (Miller 2000). fair and open electoral system, political elites do not find it i

S32 Public Administration Review • December 2011 • Special Issue

This content downloaded from

188.26.148.163 on Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

interest to do what is efficient for producing public goods in the of President Reagan as increasing accountability of the bureaucracy

political system that they manage. to the public.

Public Administration and Democratic Accountability Flawed Agents and Conflicting Principals

In the process of studying biases in congressional representation that While principal-agent theory has advanced the study of Con-

lead to factions, the obvious but less familiar deduction from these gress and the bureaucracy in significant ways (Bendor, Glazer, and

theories - that public agencies may serve as an Hammond, 2001; Epstein and O'Halloran

alternative form of representation, and a check 1999), it unfortunately ignores the decades

In the process of studying

on imperfections in the legislative process - is of administrative reform from the Progres-

examined infrequently. Yet this role for public

biases in congressional sives through the mid-twentieth century, in

agencies is central to the understanding of the representation that lead to which a professional public bureaucracy was

historical relationship between factions and factions, the obvious but less viewed as a partial solution to the problem

public administration in the United States familiar deduction from these of social inefficiency caused by rent seeking

and the role of public agencies today. and corrupt politicians. The extent to which

theories - that public agencies

Congress fails to represent the public per-

may serve as an alternative

Principal-Agent Theory fectly, or has its own agenda of rent seeking,

The dominant political economy model is form of representation, and a increasing bureaucratic accountability to

derived from principal-agent theory, in which check on imperfections in the Congress exacerbates rather than mitigates

public administrators are the agents of legisla- legislative process - is examined the problem. Principal-agency theory thereby

tors and the president, who act as principals infrequently. Yet this role for is also inconsistent with the spirit of the Feder-

on behalf of the citizenry. The highly signifi- alist Papers , which went out of their way to

public agencies is central to the

cant work of McCubbins, Noll, and Wein- explain how majoritarian, national legislatures

understanding of the historical

gast (1987) and of Weingast (1984) defines were unstable and dangerous and should be

principal-agent relationships in government

relationship between factions checked by other branches of government and

in terms of the responsiveness of the bureauc- and public administration in federalism.

racy to elected officials. Bureaucracy is viewed the United States and the role

as an obstacle to democratic accountability, of public agencies today. Conflict between Congress, the president, and

which occurs primarily through elected leg- the courts can make delegation to professional

islators but also through the president. They bureaucracies more credible. Once in place,

see elected legislators as the legitimate agents of the public and the professional bureaucracies can serve as a semiautonomous check

controlling determinants of bureaucratic behavior. Elected officials on other institutional actors in the Madisonian system of divided

play this central role because the U.S. Constitution has imposed government and leverage the capacity of legal-constitutional govern-

"institutional safeguards and incentive structures" that "make ment to constrain rent seeking and corruption. Political economy,

elected representatives responsive to citizens" (McCubbins, Noll, and principal-agency theory in particular, implicitly dismisses the

and Weingast 1987, 243). possibility that a bureaucrat could serve the public by defying Con-

gress or the president. But rent seeking and corruption were most

Principal-agency theory thus equates accountability to Congress rampant in the eighteenth century, when administrative agencies

with accountability to the public. Elected officials are assumed to were highly responsive to congressional and state legislative parties

act in the public interest, which makes the power of public admin- and interest group constituencies.

istrators the fundamental threat in the system. McCubbins, Noll,

and Weingast write that the central problem of democratic respon- Trustee Theory and Public Agency Discretion

siveness is "how - or indeed, whether - elected political officials In several areas of economic policy, Congress has established

can reasonably effectively assure that their policy intentions will be independent commissions and regulatory agencies that act more

carried out" (1987, 243; emphasis added). And as McCubbins and like "trustees" of the public interest than as agents of congressional

Schwartz add, "Whatever the original intent, it is no longer plausi- principals. The difference is that trustee agencies are expected to

ble in most cases to suppose that the public interest is best served by protect the public interest, even in opposition to the wishes of

a bureaucracy unaccountable to Congress and, therefore , unaccount- specific congressional committees or majorities. Their mandate is

able to the electorate" (1984, 169; emphasis added). similar to the legal basis for setting up trustees and trusts for minor

children until they reach adulthood or for heirs in estate planning.

Works by Moe (1985) and Wood and Waterman (1991) discuss In the area of trade, for example, the widespread public disgust of

multiple principals, including the president and the Congress, but Congress's tariff policies resulted in a movement toward agency

tend to view the president as the primary principal for the bu- delegation. The Tariff Commission was created so that something

reaucracy. This literature is similar to congressional principal-agent other than the vagaries of an unstable coalition process in service of

studies in viewing accountability as flowing from the public to the narrow legislative reelection interests could be injected into trade

president (Golden 2000, 3-9). The main object of study is how to negotiations (Goldstein 1989, 64). Other major agencies that Con-

tighten presidential control over bureaucracy, what tools are used to gress has established with "trustee" authority include the National

control the bureaucracy, and what conditions make political control Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the Federal Reserve Board (Fed),

more likely to occur (Gormley 1989). Principal-agent studies of the and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), among other

presidency have looked favorably on the "administrative presidency" regulatory agencies. In each case, the agency heads and commission

Are Factions the Problem? S33

This content downloaded from

188.26.148.163 on Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14: Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

members enjoy fixed terms in office and greater discretion in policy in power but hurt the country as a whole. An example is the nation-

and rulemaking than mainline departments. The agencies are de- alization of many industries in the United Kingdom by the Labour

signed to employ professional expertise in problem solving as a way government after World War II.

to establish a greater "credible commitment" to sound economic

policies (Knott and Miller 2008). It also begs the question of the enormously important role of public

administration and the dramatic growth of federal, state, and local

Conclusion public agencies. The development of professional public administra-

tion,

The Federalists supported a republican form of government with a the civil service, and administrative laws and procedures played

a significant role historically in reducing corruption and political

system of checks and balances. They sought to make it more diffi-

moral hazard. Similarly, semi-independent regulatory agencies and

cult to put together a winning (more than simple majority) coalition

commissions played an important role in providing problem-solving

and easier to block simple majority coalitions. They believed that

this form of government in a large, complex expertise and credible commitment in many

country would curb the power of majority areas of economic policy making. Even the

coalitions to repress minorities and enact European Union, with its dominance of

The question is whether the

legislation that did not benefit the country as parliamentary regimes, has witnessed a strong

Federalists were right: does a

a whole. The question is whether the Federal- growth in the development of regulatory

republican system of checks agencies, independent commissions, and non-

ists were right: does a republican system of

checks and balances give better results for the and balances give better results governmental organizations to deal with the

public interest than a democracy by majority for the public interest than a problem of credible commitment in economic

rule? The history of the United States as well democracy by majority rule? regulation (Majone 1997).

as theoretical analyses of American politics The history of the United States

support normative arguments on both sides of Thus, there is an inevitable trade-off between

this issue.

as well as theoretical analyses

the benefits (and costs) of majority rule

of American politics support against the benefits (and costs) of constraints

One argument is that the Federalists under- normative arguments on both on majority rule. The challenge, then, is to

estimated the enormous costs of a checks and sides of this issue. adopt the right mix of constraints on and sup-

balances system. Each check, or veto point, in ports for majority rule decision making. With

the system has the potential to block positive regard to public administration, the bureau-

legislation for the country and to promote special legislation for its cratic politics of separation of powers in the United States creates

own interests. This veto power leads to reciprocal agreements among multiple authority structures that yield some degree of bureaucratic

participants to support the demands of other veto players in return independence (Moe 1985; Hammond and Knott 1996). In practice,

for one s own favored legislation. Such reciprocity produces subop- this means delegation to professionals and experts in administra-

timal results for the country, including larger overall budgets than tive agencies. In areas of policy concerned with economic efficiency,

individual legislators prefer. It also involves a complicated system of Congress also has delegated a greater role for semi-independent

accountability, with unclear lines of authority for public administra- regulatory agencies to help government establish credible commit-

tors and the potential for public agencies to form political alliances ment to sound economic and financial policies.

with a subset of veto players against the majority. The long, arduous

road to civil rights legislation, the byzantine system of health care Public agency accountability to the public rests on a checks and bal-

reforms, and "pork barrel" overspending on inefficient projects all ances system. The check on public agencies derives fundamentally

reflect the high costs of a checks and balances system. from their creation by democratic legal statute, the appointment

of public administrators by elected officials, and congressionally

Given this set of real costs, the argument can be made that it would established committees to oversee specific areas of the bureaucracy.

be better to adopt a parliamentary form of government with no Accountability also includes an important role for the courts and

separation of powers, with public administrators accountable to the judiciary through legal suites, regulations, and legal procedures

majority coalitions. Simple majority rule is the goal, and the rest of embodied in the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 and com-

government should be organized to make simple majority rule deci- mon law practices. In addition, accountability depends on statutes

sive and to guarantee that all of government is responsive to simple and rules seeking to guarantee transparency for operations and data

majorities. The unitary and centralized parliamentary system in the collection and storage, through the Freedom of Information Act of

United Kingdom represents this majority rule form of constitu- 1966, and very significantly, the related independent role of inves-

tional democracy. Until recently, all authority resided in the House tigative reporting by the news media and through the Internet. Fi-

of Commons, with no independent judiciary or executive branch nally, accountability is dependent on merit hiring, professionalism,

and no federal system of checks and balances. The parliamentary the civil services, and an ethical commitment to promote the public

principle is that, in a democracy, the only legitimate rule is by the good (Bertelli and Lynn 2006; Knott and Miller 1987), which was

majority. initially introduced during the Progressive Movement at the end of

the nineteenth century.

The problem is that this normative position ignores majority rule

instability and democratic representation biases in favor of organ- Two new developments in the second half of the twentieth century

ized interests, even with fair and open elections. Majority rule gov- pose challenges to this constitutional basis of democratic account-

ernments also can pass inefficient policies that benefit the majority ability. One development is the extensive system of contracting out

S34 Public Administration Review • December 2011 • Special Issue

This content downloaded from

188.26.148.163 on Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

and privatization of many public agency functions to private and public administrators are likely to be blamed for poor policy outcomes by

nonprofit agencies, from garbage collection to national defense. In conscientiously following the preferences of congressional overseers.

this process of privatizing public goods production and delivery, seri-

ous issues of democratic accountability arise outside the system set Fortuitously, a separation of power system creates multiple overseers for

up over years to regulate public agencies. Of particular concern is the bureaucratic agencies, giving them a degree of discretionary power not

ability of private contractors and service providers to engage in politi- easily attained in a unitary system. If this discretion is checked by legal

cal lobby activities that seek to influence congressional and legislative due process, public transparency requirements, and professional norms,

decisions in their favor. This blurring of the differences between the these executive agencies can better carry out the state's activities and

public and private sectors raises serious questions of democratic ac- policies in the public interest and join the overall system of checks and

countability and the constitutional role for public administration. balances as a protection against the undue influence of political factions.

A second challenge is the strong growth in public employee unions In economic policy this professional discretionary power is particularly

at all levels of government. In some states, public unions influ- important. Government needs to be strong enough to intervene to

ence the outcomes of local and state elections because of low voter protect property rights and enforce contracts, but any government strong

turnout among the general population in primaries. Unions also enough to do so also is strong enough to confiscate property and violate

spend millions of dollars on lobbying activities through the news contracts to the benefit of factions with political power or to form coali-

media and other avenues in support of additional spending on tions with economic interests that might benefit from cartels or other

pensions and budget support for teachers, prison guards, and public forms of corruption. Hence, for government to pursue sound money,

safety agencies and employees. In addition, public employee unions banking, and economic regulatory policies, it must establish a credible

through seniority protections and other practices breach the norm commitment to protect the money supply and regulate the economy in

of hiring, promotion, and compensation based on merit. the public interest. Such credibility requires professional public agencies

that operate within the broad framework of democratic accountability

While there are better and worse ways to make the trade-off between but with a degree of discretionary power to base decisions on economic,

the costs and benefits of majority rule, it is likely that Madison and banking and financial expertise in order to sustain the trust of the

the Federalists would support the delegation of authority to public Congress and the people.

administrative agencies. They would view public administration as

one of several imperfect agents of the public, best able to serve the Consequently, the public is better served by a checks and balances system

public by being capable of serving as a viable professional check and of competing flawed institutions, including the bureaucracy. Such com-

balance to the ambitions of an imperfect legislature and executive. petition is superior to a system in which any one of those institutions,

And, at this period of history, the nation will not return to a public such as the Congress, would possess monopoly control over and access to

administration without private contractors, government-sponsored the bureaucracy. A checks and balances system that includes a role for a

enterprises, or public employee unions. It is essential, therefore, that professional bureaucracy would help to mitigate the undue influence of

these new entities also become better integrated into the constitu- political factions and their deleterious effects.

tional system of checks and balances that regulates the interplay of

political factions and public institutions in government. -PUBLIUS

Federalist No. 10 Appended Acknowledgments

This essay suggests the following appendix to Federalist No. 10: The author would like to thank Jennifer M. Connolly, a Ph

student in public policy and administration in the School of

It is argued that in a decentralized ' pluralistic American system , public Planning, and Development at the University of Southern C

agencies face incentives to become active partners in political corruption for her excellent research assistance in preparing this article.

and inefficient behavior through the formation of political alliances

with interest groups and congressional committees. In these arguments, References

public administrators gain constituency and interest group support as Allison, Graham T. 1971. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis.

well as increased budgets and authority from congressional committees. Boston: Little, Brown.

But are these alliances between agencies , Congress , and interest groups Arnold, R. Douglas. 1979. Congress and the Bureaucracy: A Theory of Influence. New

social costs attributable to pluralism and the separation of powers? Con- Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

sider farm price supports , which are common in European centralized Arrow, Kenneth. 1963. Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care.

parliamentary systems. Farm price supports as well as other inefficient American Economic Review 53(5): 941-73.

policies in all these countries derive from legislative logrolling and Bendor, Jonathan, Amihai Glazer, and Thomas Hammond. 2001. Theories of Del-

representation biases in favor of organized interests. These inefficient egation. Annual Review of Political Science 4: 235-69.

policies illustrate the costs of majority rule rather than the role of public Bernstein, Marver H. 1955. Regulating Business by Independent Commission. Prince-

administration in a decentralized, separation of powers system. ton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bertelli, Anthony M., and Laurence E. Lynn, Jr. 2006. Madison's Managers: Public

If public agencies responsively carry out congressional policy in these ar- Administration and the Constitution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

eas, they become the reliable implementers of socially inefficient policies. Carey, George W. 1995. The Federalist: Design for a Constitutional Republic. Urbana:

Members of Congress, when criticized for failed policies, are quick to lay University of Illinois Press.

blame on public administrators as the cause of the policy failure, and Caro, Robert. 1975. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York . New

quickly distance themselves from the issue. In numerous policy areas, York: Random House.

Are Factions the Problem? S35

This content downloaded from

188.26.148.163 on Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Downs, Anthony. 1967. Inside Bureaucracy. Boston: Little, Brown.

Epstein, David F. 2007. The Political Theory of the Federalists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Epstein, David, and Sharyn O'Halloran. 1999. Delegating Powers: A Transaction Cost Politics Approach to Policy Making Under Separate Powers. New York: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

Eswaran, Mukesh, and Ashok Kotwal. 1984. On the Moral Hazard of Budget-Breaking. RAND Journal of Economics 15(4): 578-81.

Golden, Marissa Martino. 2000. What Motivates Bureaucrats? Politics and Administration during the Reagan Years. New York: Columbia University Press.

Goldstein, Judith. 1989. The Impact of Ideas on Trade Policy: A Comparative Study of the Origins of American Agriculture and Manufacturing Policies. International Organi-

zation 43: 31-71.

Gormley, William T., Jr. 1989. Taming the Bureaucracy: Muscles, Prayers , and Other Strategies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gulick, Luther, and Lyndall Urwick, eds. 1937. Papers on the Science of Administration. New York: Institute of Public Administration.

Hammond, Thomas H., and Jack H. Knott. 1996. Who Controls the Bureaucracy? Presidential Power, Congressional Dominance, Legal Constraints, and Bureaucratic Au-

tonomy in a Model of Multi-Institutional Policymaking. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 12(1): 121-68.

Hammond, Thomas H., and Gary J. Miller. 1985. A Social Choice Perspective on Expertise and Authority in Bureaucracy. American Journal of Political Science 29(1): 1-28.

Holmstrom, Bengt. 1982. Moral Hazard in Teams. Bell Journal of Economics 13(2): 324-40.

Kaufman, Herbert. 1967. The Forest Ranger: A Study in Administrative Behavior. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kelman, Steve. 2007. Public Administration and Organization Studies. Academy of Management Annals 1: 225-67.

Knott, Jack H., and Gary J. Miller. 1987. Reforming Bureaucracy: The Politics of Institutional Choice. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lewis, Eugene. 1980. Public Entrepreneurship: Toward a Theory of Bureaucratic Political Power. Bloomington: Indiana Unive

Light, Paul C. 2008. A Government III Executed: The Decline of the Federal Service and How to Reverse It. Cambridge, MA: H

Majone, Giandomenico. 1997. From the Positive to the Regulatory State: Causes and Consequences of Changes in the M

139-67.

McCubbins, Matthew D., Roger G. Noll, and Barry R. Weingast. 1987. Administrative Procedures as Instruments of Political Control. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organi-

zation 3(2): 243-77.

McCubbins, Matthew D., and Thomas Schwartz. 1984. Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols versus Fire Alarms. American Journal of Political Science 28(1):

165-79.

Meier, Kenneth R. 1975. Representative Bureaucracy: An Empirical Analysis. American Political Science Review 69(2): 526-42.

Meier, Kenneth R., and Laurence J. O'Toole, Jr. 1999. Modeling the Impact of Public Management: Implications of Structural Context. Journal of Public Administration

Research and Theory 9(4): 505-26.

Milward, H. Brinton, and Keith G. Provan. 2000. Governing the Hollow State. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10(2): 359-80.

Miller, Gary J. 2000. Above Politics: Credible Commitment and Efficiency in the Design of Public Agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10(2):

289-328.

Moe, Terry M. 1985. The Politicized Presidency. In The New Direction in American Politics, edited by John E. Chubb and Paul E. Peterson, 23 5-71. Washington, DC:

ings Institution.

Mosher, Frederick C. 1982. Democracy and the Public Service. In Representative Bureaucracy: Classic Readings and Continu

H. Rosenbloom, 19-22. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Niskanen, William A., Jr. 1971. Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Chicago: Aldine, Atherton.

Olson, Mancur. 1971. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni

Ostrom, Vincent. 2008. The Political Theory of a Compound Republic: Designing the American Experiment. 3rd ed. Lan

Pressman, Jeffrey L., and Aaron B. Wildavsky. 1973. Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed

Rourke, Francis E. 1984. Bureaucracy, Politics, and Public Policy. 3rd ed. Boston: Little, Brown.

Schick, Allen. 1966. The Road to PPB: The Stages of Budget Reform. Public Administration Review 2 6(4): 243-58.

Seidman, Harold. 1970. Politics, Position, and Power: The Dynamics of Federal Organization. New York: Oxford Universit

Sen, Amartya K. 1970. Collective Choice and Social Welfare. San Francisco: Holden-Day.

Simon, Herbert A. 1947. Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organization

Stigler, George W. 1971. The Theory of Economic Regulation. Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 2

Warwick, Donald P. 1979. A Theory of Public Bureaucracy: Politics, Personality, and Organization in the State Departme

Weingast, Barry R. 1984. The Congressional-Bureaucratic System: A Principal-Agent perspective (with Applicatio

Wildavsky, Aaron B. 1964. The Politics of the Budgetary Process. Boston: Little, Brown.

Willoughby, William F. 1927. Principles of Public Administration. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wilson, James Q. 1989. Bureaucracy: What Government Agencies Do and Why They Do It. New York: Basic Books.

Wilson, Woodrow. 1887. The Study of Administration. Political Science Quarterly 2(2): 197-222.

Wood, Dan, and Richard Waterman. 1991. The Dynamics of Political Control of the Bureaucracy. American Politica

S36 Public Administration Review • December 2011 • Special Issue

This content downloaded from

188.26.148.163 on Tue, 28 Feb 2023 14:40:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Financial Policy at AppleDocument9 pagesFinancial Policy at AppleVamsiKrishnaKondapuram25% (4)

- Lottery Scam EmailDocument6 pagesLottery Scam EmailMushtaq M.Chinoy90% (41)

- Admin Law by DR Yashomati GhoshDocument245 pagesAdmin Law by DR Yashomati GhoshSanika GadgilNo ratings yet

- Fung, A. (2006) Varieties of Participation in Complex GovernanceDocument11 pagesFung, A. (2006) Varieties of Participation in Complex GovernanceNatalie D.No ratings yet

- Gerry Stokers 5 PropositionsDocument15 pagesGerry Stokers 5 PropositionsPooja Ashar100% (1)

- Activities and Assessment . . ..6-7: Democratic InterventionDocument20 pagesActivities and Assessment . . ..6-7: Democratic InterventionCarmelo Justin Bagunu Allauigan100% (1)

- Hamilton Police Services Awards Night ProgramDocument8 pagesHamilton Police Services Awards Night Programthe_specNo ratings yet

- Federalist 10 QuestionsDocument3 pagesFederalist 10 QuestionsWesley MajorNo ratings yet

- Wilson - Bureaucracy Problem PDFDocument7 pagesWilson - Bureaucracy Problem PDFGuilherme LissoneNo ratings yet

- 2006 - A - Mccormick - Contain The Wealthy and Patrol The Magistrates Restoring Elite Accountability To PopularDocument18 pages2006 - A - Mccormick - Contain The Wealthy and Patrol The Magistrates Restoring Elite Accountability To PopularJulian RM100% (1)

- Durant Burns Repositioning Public AdministrationDocument12 pagesDurant Burns Repositioning Public AdministrationHERNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Federalist PapersDocument2 pagesAssignment 1 Federalist PapersYash AjaniNo ratings yet

- Devolution PDFDocument12 pagesDevolution PDFTaruna Kumar MohantyNo ratings yet

- Adm Week 7 - Q4 - UcspDocument5 pagesAdm Week 7 - Q4 - UcspCathleenbeth MorialNo ratings yet

- Midterms - Official Civil Welfare Training Service ReviewerDocument31 pagesMidterms - Official Civil Welfare Training Service ReviewerNiña Ricci MtflcoNo ratings yet

- PS103N ReviewerDocument23 pagesPS103N ReviewerPrecious Anne ManlongatNo ratings yet

- Confederalism, Cetralism, Federalism TableDocument3 pagesConfederalism, Cetralism, Federalism TableAlejandra SigüenzaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Cornell Notes Lined TemplateDocument4 pagesChapter 8 Cornell Notes Lined TemplateArturo MontemayorNo ratings yet

- CH 3 Principles of DemocracyDocument25 pagesCH 3 Principles of DemocracyRama Raman SinghNo ratings yet

- Winter2020 Supplement Ganz Civil SocietyDocument5 pagesWinter2020 Supplement Ganz Civil SocietyAndrea BonadonnaNo ratings yet

- Government FinalDocument6 pagesGovernment FinalEvelyn ArjonaNo ratings yet

- Milward, H. B., & Provan, K. G. (2000) - Governing The Hollow StateDocument22 pagesMilward, H. B., & Provan, K. G. (2000) - Governing The Hollow StateLuis Alberto Rocha MartinezNo ratings yet

- Appendix 1 - Needs Based Approach Vs Rights Based ApproachDocument3 pagesAppendix 1 - Needs Based Approach Vs Rights Based ApproachRaven Nicole MoralesNo ratings yet

- Corruption Need Civil-2013Document7 pagesCorruption Need Civil-2013samimakhtargain2002No ratings yet

- Punchhi Commission Report Volume 4 On Centre State Relaitons.Document182 pagesPunchhi Commission Report Volume 4 On Centre State Relaitons.Abhishek SharmaNo ratings yet

- Mil Ward and Pro Van Hollow StateDocument23 pagesMil Ward and Pro Van Hollow StateportellamarcusNo ratings yet

- Q4 W2 Trends, Networks - KSA-LeaPDocument3 pagesQ4 W2 Trends, Networks - KSA-LeaPMary Jane CalandriaNo ratings yet

- Considine - Policy InterventionsDocument12 pagesConsidine - Policy InterventionsMaryNo ratings yet

- POLSC112-Referene-List-RAMOS. NEIL-4APLDocument11 pagesPOLSC112-Referene-List-RAMOS. NEIL-4APLNeil Bryan C RamosNo ratings yet

- Why The Government Should Not Regulate Content Moderation of Social MediaDocument32 pagesWhy The Government Should Not Regulate Content Moderation of Social MediaCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- CH 2.3 Bold Powers and Sharp Limits AssignmentDocument1 pageCH 2.3 Bold Powers and Sharp Limits Assignmentkurmapu2006No ratings yet

- Why The Government Should Not Regulate Content Moderation of Social Media (John Samples, CATO)Document32 pagesWhy The Government Should Not Regulate Content Moderation of Social Media (John Samples, CATO)A MNo ratings yet

- State and Society in The Process of DemocratizationDocument32 pagesState and Society in The Process of DemocratizationJohn Paul75% (12)

- Caiden, G., The Study of Public AdministrationDocument24 pagesCaiden, G., The Study of Public AdministrationJa Luo100% (3)

- Group 5 Global Media and Culture 1Document27 pagesGroup 5 Global Media and Culture 1Mary Grace GalangNo ratings yet

- Federalist Papers 10 51 ExcerptsDocument2 pagesFederalist Papers 10 51 Excerptsapi-292351355No ratings yet

- Insight CSM22 Test 41Document24 pagesInsight CSM22 Test 41Akash NawinNo ratings yet

- Goldfrank (2007) The Politics of Deepening Local DemocracyDocument23 pagesGoldfrank (2007) The Politics of Deepening Local DemocracyThelma CayeNo ratings yet

- Di Pa TaposDocument3 pagesDi Pa TaposCarlos SantosNo ratings yet

- SWP 1 Topic7 BSSW1B 2Document7 pagesSWP 1 Topic7 BSSW1B 2carlabelgica379No ratings yet

- Citizen Governance - As Image Management in Postmodern Context (Administrative Theory & Praxis, Vol. 21, Issue 3) (1999)Document8 pagesCitizen Governance - As Image Management in Postmodern Context (Administrative Theory & Praxis, Vol. 21, Issue 3) (1999)MaadhavaAnusuyaaNo ratings yet

- Justice and The Law ReportDocument38 pagesJustice and The Law ReportsundafundaNo ratings yet

- Myth of DichotomyDocument9 pagesMyth of DichotomymahadiNo ratings yet

- Politics Governance and Citizenship NotesDocument4 pagesPolitics Governance and Citizenship NotestupigwaterNo ratings yet

- Charles Beitz - Human Rights As A Common ConcernDocument15 pagesCharles Beitz - Human Rights As A Common ConcerncinfangerNo ratings yet

- What Is Good GovernanceDocument3 pagesWhat Is Good Governanceshella.msemNo ratings yet

- Federalist 51 Primary DocumentDocument4 pagesFederalist 51 Primary Documentapi-327032256No ratings yet

- Quarter 2 1ST Semester UcspDocument16 pagesQuarter 2 1ST Semester Ucspschool.eunicepaculbaNo ratings yet

- DELOS REYES, Steve - PolGov - Module 3Document6 pagesDELOS REYES, Steve - PolGov - Module 3Fanboy KimNo ratings yet

- Tools of GovernmentDocument141 pagesTools of GovernmentK58 VU HA ANHNo ratings yet

- GovernanceDocument35 pagesGovernanceStudent Use100% (1)

- Wise - Society - 2020 - Organizations of The Future Greater Hybridization Coming Author (S) Charles R - Wise Source Public Administration RDocument4 pagesWise - Society - 2020 - Organizations of The Future Greater Hybridization Coming Author (S) Charles R - Wise Source Public Administration RputriNo ratings yet

- Federalist PapersDocument9 pagesFederalist PapersThet Htar ZawNo ratings yet

- CH 9FederalBureaucracyQuestionsDocument3 pagesCH 9FederalBureaucracyQuestionsDylanNo ratings yet

- CST Principles Dangers or Threats of Globalization Promises or Possibilities of Globalization What Must Be Done?Document3 pagesCST Principles Dangers or Threats of Globalization Promises or Possibilities of Globalization What Must Be Done?mark perezNo ratings yet

- Newweave Chapter3Document20 pagesNewweave Chapter3MayaNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Monopolies & Corporate Public CorruptionDocument17 pagesThe Problem of Monopolies & Corporate Public CorruptionAndres PalaciosNo ratings yet

- Local Governance: Second Administrative Reforms CommissionDocument8 pagesLocal Governance: Second Administrative Reforms CommissionpeeyushNo ratings yet

- The Theory and Reality of Administration: E8: Contemporary Administrative SystemsDocument25 pagesThe Theory and Reality of Administration: E8: Contemporary Administrative SystemsprabodhNo ratings yet

- Public AdministrationDocument32 pagesPublic AdministrationAli SultanNo ratings yet

- NSTP Module 2 Lesson 1Document13 pagesNSTP Module 2 Lesson 1Andrea WaganNo ratings yet

- Horsley 2010Document32 pagesHorsley 2010Nicolas Diaz-CruzNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument19 pagesUntitledAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Browne - Multiple SponsorshipDocument7 pagesBrowne - Multiple SponsorshipAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Gray & Lowery - The Institutionalization of State Communities of Organized InterestsDocument21 pagesGray & Lowery - The Institutionalization of State Communities of Organized InterestsAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Cadot - Lobbying For Tariffs Against NonmembersDocument24 pagesCadot - Lobbying For Tariffs Against NonmembersAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Bachrach & Baratz - Decisions and Nondecisions (Analytical Framework)Document12 pagesBachrach & Baratz - Decisions and Nondecisions (Analytical Framework)Alex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Austeen-Smith & Wright - Counteractive LobbyingDocument21 pagesAusteen-Smith & Wright - Counteractive LobbyingAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Austeen-Smith & Wright - Theory and Evidence For Counteractive LobbyingDocument23 pagesAusteen-Smith & Wright - Theory and Evidence For Counteractive LobbyingAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Deakin - Rational Economic Behaviour and Lobbying On Accountig IssuesDocument16 pagesDeakin - Rational Economic Behaviour and Lobbying On Accountig IssuesAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Austeen-Smith - Strategic Transmission of Costly InformationDocument10 pagesAusteen-Smith - Strategic Transmission of Costly InformationAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument34 pagesUntitledAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Austeen-Smith - Voluntary Pressure GroupsDocument12 pagesAusteen-Smith - Voluntary Pressure GroupsAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Zeigler - The Effects of LobbyingDocument20 pagesZeigler - The Effects of LobbyingAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Wright - The Contest Between Organized Labor and Organized BusinessDocument28 pagesWright - The Contest Between Organized Labor and Organized BusinessAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Wright - Risk and Uncertainty As Factors in The Durability of Political CoalitionsDocument16 pagesWright - Risk and Uncertainty As Factors in The Durability of Political CoalitionsAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Yeung - Rent SeekingDocument13 pagesYeung - Rent SeekingAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Davis - Some Neglected Aspects of British Pressure GroupsDocument13 pagesDavis - Some Neglected Aspects of British Pressure GroupsAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Costain - Women Lobby Organizing A Diffuse InterestDocument17 pagesCostain - Women Lobby Organizing A Diffuse InterestAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Costain - Representing Women (Interst Group)Document15 pagesCostain - Representing Women (Interst Group)Alex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Calkins - A Victorian Free Trade LobbyDocument16 pagesCalkins - A Victorian Free Trade LobbyAlex RădulescuNo ratings yet

- Admin BriefDocument3 pagesAdmin BriefSrirajVoraNo ratings yet

- Pay SlipDocument1 pagePay SlipMukesh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Kushal Pal - DYNAMICS OF PARTY SYSTEM AND FORMATION OF COALITION GOVERNMENTDocument13 pagesKushal Pal - DYNAMICS OF PARTY SYSTEM AND FORMATION OF COALITION GOVERNMENTKhushboo SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Peoria County Booking Sheet 06/16/14Document7 pagesPeoria County Booking Sheet 06/16/14Journal Star police documentsNo ratings yet

- Nominating Agency Declaration - Required For Public Sector Applicants OnlyDocument1 pageNominating Agency Declaration - Required For Public Sector Applicants OnlyFeri Rahmat Chandra PiliangNo ratings yet

- Law QuizDocument7 pagesLaw QuizPrince Jherald MagtotoNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics A Contemporary Approach 10th Edition Mceachern Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument67 pagesMacroeconomics A Contemporary Approach 10th Edition Mceachern Test Bank Full Chapter PDFtimothycuongo6n100% (16)

- Cross Sectional Area of Reinforcement (MM /M) at Given Bar SpacingDocument1 pageCross Sectional Area of Reinforcement (MM /M) at Given Bar SpacingLynx101No ratings yet

- Davao Light V CADocument7 pagesDavao Light V CAyasuren2No ratings yet

- People of The Phil. vs. Lyndon M. FloresDocument9 pagesPeople of The Phil. vs. Lyndon M. FloresAnonymous dtceNuyIFINo ratings yet

- 4 Marks Question History PDFDocument2 pages4 Marks Question History PDFAteeq ZahidNo ratings yet

- Income ExemptDocument25 pagesIncome Exemptapi-3832224No ratings yet

- Leaf Obd Readthedocs Io en LatestDocument29 pagesLeaf Obd Readthedocs Io en LatestodipasNo ratings yet

- David Hume My Own LifeDocument8 pagesDavid Hume My Own Lifeoolong9No ratings yet

- Manual N5180-90002 InstallationDocument40 pagesManual N5180-90002 InstallationAna Safranec VasicNo ratings yet

- E TicketDocument2 pagesE TicketRoselle WuNo ratings yet

- AZURE ACCESS AND SecurityDocument20 pagesAZURE ACCESS AND Securityamit kaishverNo ratings yet

- 27 PPT SocialismDocument14 pages27 PPT SocialismTeja TheegalaNo ratings yet

- 19206b Warn 200511 MGM Resorts IntDocument2 pages19206b Warn 200511 MGM Resorts IntReno Gazette Journal100% (1)

- Evolution of Taxation in The Philippines Hernandez 2.0 Bsais 1Document1 pageEvolution of Taxation in The Philippines Hernandez 2.0 Bsais 1Zeny HernandezNo ratings yet

- Traffic Incident Management PPT 1Document32 pagesTraffic Incident Management PPT 1Isshan DulayNo ratings yet

- Mohammed Muneer Ali Mohammed MahboobDocument5 pagesMohammed Muneer Ali Mohammed MahboobMuneer MoonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Corporate GovernanceDocument9 pagesChapter 5 - Corporate GovernanceThanh PhươngNo ratings yet

- CMSS GRADE 7.xlsx 2023Document6 pagesCMSS GRADE 7.xlsx 2023Charrynell DignaranNo ratings yet

- Behn Meyer V YangcoDocument2 pagesBehn Meyer V Yangcoevgciik100% (1)

- Sbca Advance Tax Rev SyllabusDocument20 pagesSbca Advance Tax Rev SyllabusChey DumlaoNo ratings yet

- Godiva South Korea PDFDocument65 pagesGodiva South Korea PDFBuğra BakanNo ratings yet