Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Inflammation Chronic Stress and Depression: Inflammation As A Mechanism Linking Chronic Stress, Depression, and Heart Disease

Inflammation Chronic Stress and Depression: Inflammation As A Mechanism Linking Chronic Stress, Depression, and Heart Disease

Uploaded by

antonioOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Inflammation Chronic Stress and Depression: Inflammation As A Mechanism Linking Chronic Stress, Depression, and Heart Disease

Inflammation Chronic Stress and Depression: Inflammation As A Mechanism Linking Chronic Stress, Depression, and Heart Disease

Uploaded by

antonioCopyright:

Available Formats

CU R RE N T DI R E CT I O NS IN P SYC H OL OGI C AL SC I EN C E

Turning Up the Heat

Inflammation as a Mechanism Linking Chronic Stress,

Depression, and Heart Disease

Gregory E. Miller and Ekin Blackwell

Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia

ABSTRACT—Mounting evidence indicates that chronic common is the tendency to be appraised as threatening and

stressors and depressive symptoms contribute to morbidi- unmanageable. They can involve situations in which the

ty and mortality from cardiac disease. However, little is troubling stimulus persists over a long time (an abusive boss), as

known about the underlying mechanisms responsible for well as situations in which the event is brief but the threat per-

these effects or about why depressive symptoms and car- sists longer (a sexual assault). Research indicates that exposure

diac disease co-occur so frequently. In this article we out- to chronic stress generally increases vulnerability to CHD. In a

line a novel model that seeks to address these issues. It study of 12,000 healthy males followed over 9 years, those facing

asserts that chronic stressors activate the immune system chronic difficulties at work or home were 30% more likely to die

in a way that leads to persistent inflammation. With long- of CHD (Matthews & Gump, 2002). Another project measured

term exposure to the products of inflammation, people adverse childhood experiences in 17,000 adults and found a

develop symptoms of depression and experience progres- dose–response relationship with CHD incidence. Those who

sion of atherosclerosis, the pathologic condition that reported a variety of adverse experiences such as neglect, do-

underlies cardiac disease. mestic violence, and parental criminal behavior were 3.1 times

more likely to develop CHD (Dong et al., 2004).

KEYWORDS—stress; depression; inflammation; atheroscle-

Depression can take the form of a low mood or a clinical syn-

rosis

drome. In both cases it typically involves sadness and anhedonia,

which may be accompanied by disturbances in eating, sleeping,

Though people have long believed that certain thoughts and and cognition. Depression is common in CHD. About 20% of

feelings are toxic for their health, only in the past 30 years has patients meet criteria for a clinical diagnosis, and even more have

convincing evidence accumulated to support this view. This symptoms below the diagnostic threshold. These symptoms di-

research indicates that while not all negative thoughts and minish quality of life and contribute to poorer medical outcomes.

feelings are bad for health, specific cognitive and emotional For example, in a study of 900 patients interviewed in the hos-

processes do contribute to the development and progression of pital following a heart attack, high levels of depressive symptoms

medical illness. In this article we focus on two of the best-studied were associated with a threefold increase in cardiac mortality

culprits, chronic stressors and depressive symptoms, and how over 5 years (Lesperance, Frasure-Smith, Talajic, & Bourassa,

they ‘‘get under the skin’’ to influence disease. We focus on 2002). There is also evidence that in healthy young adults, de-

coronary heart disease (CHD), the leading cause of mortality in pressive symptoms can accelerate the development of CHD. For

developed countries and the context in which mind–body con- example, in a 27-year study of middle-aged adults, those with

nections are best documented. high levels of depressive symptoms at baseline were 1.7 times

more likely to have a fatal heart attack (Barefoot & Schroll, 1996).

Although these findings provide compelling evidence of

STRESSORS, DEPRESSION, AND CHD RISK

mind–body connections in CHD, they also raise challenging

questions that researchers are just starting to address. One has to

Chronic stressors come in different packages, ranging from

do with the underlying mechanisms linking mind and body. How

troubled marriages to difficult workplaces. What they have in

can nebulous patterns of thinking and feeling ‘‘get inside the

body’’ in a way that alters disease trajectories? A second ques-

Address correspondence to Dr. Gregory Miller, Department of Psy-

chology, University of British Columbia, 2136 West Mall Avenue, tion has to do with the high rate of comorbidity between

Vancouver BC V6T 1Z4 Canada; e-mail: gemiller@psych.ubc.ca. depression and CHD. There are other serious medical condi-

Volume 15—Number 6 Copyright r 2006 Association for Psychological Science 269

Inflammation as a Mechanism Linking Chronic Stress, Depression, and Heart Disease

tions, such as cancer, for which the rates of depression are much that the excessive inflammation is responsible for bidirectional

lower (Dew, 1998). Why is it especially common in cardiac pa- connections between depression and atherosclerosis. That is,

tients? Another question researchers struggle with concerns cytokines are viewed as a mechanism through which depression

theoretical integration. Though most studies have focused on fosters CHD progression, and at the same time as the reason

chronic stress or depressive symptoms, these states are likely to cardiac patients experience high rates of affective difficulties. It

be closely related and to influence disease through similar should be noted that although chronic stress is depicted as the

pathways. So an important challenge involves conceptually in- model’s starting point, a person could enter the cascade as a result

tegrating literatures that have evolved separately and deter- of depressive symptoms or coronary disease; chronic stress is

mining where the ‘‘action’’ really is. sufficient, but not necessary, to initiate the model’s processes.

WHAT IS INFLAMMATION?

AN INTEGRATIVE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

When the immune system detects invading microbes like viruses

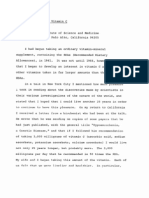

We have developed a conceptual framework to begin answering or bacteria, it launches an inflammatory response, which causes

these questions (Fig. 1). It begins with the notion that chronic white blood cells to accumulate at the site of infection. These

stressors activate the immune system in a way that leads to cells attempt to eliminate the pathogen, rid the body of cells that

persistent inflammation. This refers to a molecular and cellular have been infected with it, and repair any tissue damage that it

cascade the body uses to eliminate infections and resolve inju- has caused. This entire process is orchestrated by inflammatory

ries. The model suggests that with long-term exposure to the cytokines, which are signaling molecules secreted by white

products of inflammation, people develop symptoms of depres- blood cells. The most critical cytokines are interleukin-1b, in-

sion and experience accelerated CHD progression. This occurs terleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-a, and they have

because the signaling molecules deployed to orchestrate in- wide-ranging functions that include directing cells toward in-

flammation—pro-inflammatory cytokines—elicit adaptations in fections, signaling them to divide, and activating their killing

the brain that are manifested as symptoms of depression. These mechanisms. Because these molecules are released when the

molecules also promote growth of plaques in blood vessels and immune system is active, researchers use their presence as a

stimulate processes that lead those plaques to rupture. In doing rough index of the magnitude of inflammation in the body. This is

so, they bring about heart attacks. The model goes on to assert also done by measuring C-reactive protein (CRP), a molecule

produced by the liver in response to IL-6.

DOES CHRONIC STRESS TRIGGER INFLAMMATION?

What evidence is there to support the idea that chronic stressors

activate the immune system in a way that promotes inflamma-

tion? Over the past few years a number of studies have found that

among persons facing serious chronic stressors, concentrations

of inflammatory molecules such as IL-6 and CRP are signifi-

cantly elevated (Segerstrom & Miller, 2004). One project fol-

lowed older adults caring for a relative with dementia.

Caregiving is a potent chronic stressor that presents challenges

in nearly every domain of life, and it does so at a time of life when

coping resources are often waning. Over a 6-year follow-up,

caregivers displayed marked increases in IL-6 and did so at a

rate that was four times more rapid than controls (Kiecolt-Glaser

et al., 2003). This pattern of findings was initially puzzling to

researchers, because chronic stressors were believed to sup-

Fig. 1. Model of how inflammatory processes mediate the relations among press immune functions. But it is now clear that the immune

chronic stressors, depressive symptoms, and cardiac disease. Stressors system responds to any given stressor in a complex fashion; some

activate the immune system in a way that leads to persistent inflammation. of its functions are activated at the same time as others are

With long-term exposure to the molecular products of inflammation,

people are expected develop symptoms of depression and experience disabled (Segerstrom & Miller, 2004).

progression of cardiac disease. Excessive inflammation is also viewed as Researchers are now seeking to understand the mechanisms

responsible for the bidirectional relationship between depression and through which chronic stressors bring about inflammation. Some

atherosclerosis. (Some pathways in the model are excluded for the sake of

brevity and simplicity—for example, the likely bidirectional relationship evidence indicates that chronic stressors ‘‘prime’’ the immune

between chronic stressors and depressive symptoms. system to respond to challenges in an especially aggressive

270 Volume 15—Number 6

Gregory E. Miller and Ekin Blackwell

fashion. Another hypothesis is that chronic stressors interfere significant metabolic demands. By spending more time sleeping

with the immune system’s capacity to shut down after a challenge and withdrawing from activities, the organism conserves energy

has been minimized. One signal the body uses to do this is and avoids contact with pathogens and predators. When viewed

cortisol; at high levels, this hormone dampens the release of from this perspective, the ‘‘depressive’’ symptoms that arise

cytokines. However, chronic stressors interfere with this pro- following inflammation are behavioral adaptations that evolved

cess. In parents whose children were being treated for cancer, to maximize the chances of survival during infection.

for example, cortisol’s ability to suppress IL-6 production was And can depression provoke inflammation? Cross-sectional

markedly diminished (Miller, Cohen, & Ritchey, 2002). This studies indicate that among patients suffering from clinical de-

suggests that chronic stressors ‘‘take the brakes off’’ inflamma- pression, concentrations of CRP and IL-6 are increased by 40%

tion. Another intriguing possibility derives from animal research to 50% (Miller, Stetler, Carney, Freedland, & Banks, 2002).

showing that stressors like social isolation can bring about in- These effects do not seem to be limited to clinical depression;

flammation in the brain (Maier, Watkins, & Nance, 2001). This similar patterns are found in patients with depressive symptoms,

process has been shown, in turn, to activate inflammation in the even when they are not severe enough to warrant a diagnosis. But

periphery. So, in humans, chronic stressors may trigger a cyto- it is difficult to rigorously evaluate whether depression provokes

kine cascade that starts in the brain and then makes its way to inflammation, because humans cannot be randomly assigned to

other areas of the body. experience affective difficulties. To overcome this difficulty, re-

searchers have studied patients before and after treatment and

DEPRESSION AND INFLAMMATION have shown that cytokine volumes decrease after depressive

symptoms have been ameliorated. These findings suggest that

Can inflammation bring about depression? To answer this ques- depression operates causally. How it does so remains unclear.

tion, researchers have exposed rodents to bacterial products that Depressive symptoms could prime the immune system to respond

trigger inflammation and shown that the animals develop symp- aggressively to challenges; alternatively, they could initiate a

toms resembling depression—symptoms known as ‘‘sickness cytokine cascade in the brain that spreads elsewhere. They also

behaviors.’’ These include declines in food intake, motor activity, could foster maladaptive behaviors that themselves activate in-

grooming behavior, and social exploration, as well as a lack of flammatory processes. The best data to date are consistent with

interest in hedonic activities such as sex (Yirmiya, 1996). It has the latter hypothesis; much of the inflammation in depression is

been difficult to examine this process directly in humans, be- attributable to excess weight and sleeping disturbances (Miller,

cause they cannot safely be exposed to inflammatory substances. Stetler, et al., 2002; Motivala & Irwin, in press).

However, researchers have been able to address this question

indirectly in cancer patients, who are administered cytokines INFLAMMATION CONTRIBUTES TO CHD

with the hope that they will boost immune functions. About 50%

of patients treated with cytokines develop symptoms, such as CHD begins when infections and injuries damage the arteries

dysphoria, anhedonia, fatigue, anorexia, and cognitive impair- supplying the heart, causing an influx of white blood cells that

ment, that are consistent with a diagnosis of major depression are seeking to repair the lesion. These cells accumulate in the

(Musselman et al., 2001). The extent of these symptoms is di- vessel wall, where they become engorged with cholesterol, and

rectly related to the dose of cytokine therapy, and prophylactic eventually contribute to formation of plaque. Much later in the

treatment with antidepressant medications can often prevent disease process, these cells help to destabilize the plaque. When

them from arising. Although these findings suggest that inflam- this occurs, the plaque can rupture, and its remnants can block

mation brings about adaptations that resemble depression, fur- blood flow in the vessel. This process deprives the heart of nu-

ther research is necessary to determine whether these conditions trients, and results in death of cardiac tissues, an outcome known

are one and the same or merely ‘‘look-alikes.’’ It may also be the as myocardial infarction, or heart attack. Because inflammation

case that sickness behavior underlies some cases of depression— is centrally involved in the progression of CHD, studies have

like those that arise in CHD and other inflammatory conditions— examined whether the presence of inflammatory molecules

but is not responsible for affective difficulties more generally. forecasts disease. This work shows that high levels of such

Researchers are still attempting to understand how and why molecules, particularly CRP and IL-6, confer risk for later CHD

sickness behaviors emerge. They may be an evolved strategy to morbidity and mortality (Libby, 2002).

maximize the chances of survival after infection (Maier & Wat-

kins, 1998). When infected, an organism’s survival depends on WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

its capacity to mount a vigorous defense and to avoid contact

with pathogens and predators that might capitalize on its vul- While several of the model’s basic predictions have been con-

nerability. Organisms must initiate a febrile response, which firmed, more work needs to be done before its overall utility can be

interferes with pathogens’ capacity to reproduce, and mobilize evaluated. The first step in the process should entail testing the

their immune systems to fight. These responses, however, pose model’s mediational hypotheses. Do stressful experiences foster

Volume 15—Number 6 271

Inflammation as a Mechanism Linking Chronic Stress, Depression, and Heart Disease

depressive symptoms and cardiac disease by triggering inflam- Dew, M.A. (1998). Psychiatric disorder in the context of physical ill-

mation? Does inflammation operate as a bidirectional pathway ness. In B.P. Dohrenwend (Ed.), Adversity, stress, and psycho-

linking depression and atherosclerosis? To answer these ques- pathology (pp. 177–218). New York: Oxford University Press.

tions, researchers will need to conduct multiwave prospective Dickerson, S.S., Gruenewald, T.L., & Kemeny, M.E. (2004). When the

social self is threatened: Shame, physiology, and health. Journal

investigations assessing constructs frequently. If the model’s of Personality, 72, 1191–1216.

predictions turn out to be accurate, it will become important to Dong, M., Giles, W.H., Felitti, V.J., Dube, S.R., Williams, J.E., Chap-

further differentiate its constructs so that their most toxic ele- man, D.P., & Anda, R.F. (2004). Insights into causal pathways for

ments are revealed. Must stressors be severe, like caregiving, to ischemic heart disease: Adverse childhood experiences study.

bring about inflammation? Or can more day-to-day concerns such Circulation, 110, 1761–1766.

as deadlines and traffic elicit the same processes? There are also Kendler, K.S., Hettema, J.M., Butera, F., Gardner, C.O., & Prescott, C.A.

nagging questions about the depression construct. Do the symp- (2003). Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and

danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and gener-

toms of depression have a unique capacity to initiate the cascades

alized anxiety. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 789–796.

depicted in the model, or is their effect attributable to a broader Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K., Preacher, K.J., MacCallum, R.C., Atkinson, C.,

cluster of negative emotions that also includes anger and anxiety Malarkey, W.B., & Glaser, R. (2003). Chronic stress and age-re-

(Suls & Bunde, 2005)? For the model to be maximally valuable as lated increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proceedings

a research tool, the next wave of studies will have to distill these of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A., 100, 9090–9095.

constructs. Fortunately, there are some good leads to guide this Lesperance, F., Frasure-Smith, N., Talajic, M., & Bourassa, M.G.

work. For example, an intriguing program of research indicates (2002). Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial

severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after

that when stressors elicit feelings of shame, they are especially

myocardial infarction. Circulation, 105, 1049–1053.

potent triggers of inflammation and have a special capacity to

Libby, P. (2002). Atherosclerosis: The new view. Scientific American,

bring about depressive episodes (Dickerson, Gruenewald, & Ke- 286, 46–55.

meny, 2004; Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner, & Prescott, Maier, S.F., & Watkins, L.R. (1998). Cytokines for psychologists: Im-

2003). As time goes on it will also become important to incorporate plications of bidirectional immune-to-brain communication for

additional mechanisms linking the model’s constructs. Research understanding behavior, mood, and cognition. Psychological Re-

has already identified a number of candidate pathways. In fo- view, 105, 83–107.

cusing our discussion on inflammation, we do not mean to imply Maier, S.F., Watkins, L.R., & Nance, D.M. (2001). Multiple routes of

action of IL-1 on the nervous system. In R. Ader, D. Felten, & N.

that these pathways are unimportant; we simply view inflammation

Cohen (Eds.), Psychoneuroimmunology (3rd ed., pp. 563–579).

as the best candidate for pulling together the disparate literatures New York: Academic Press.

we have discussed. Of course, for the model to be complete, these Matthews, K., & Gump, B.B. (2002). Chronic work stress and marital

other pathways must be integrated. To the extent that the next wave dissolution increase risk of posttrial mortality in men from the

of studies can meet these challenges, researchers will be able to Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Archives of Internal

develop convincing mechanistic explanations for the age-old be- Medicine, 162, 309–315.

lief that the mind and body are connected. Miller, G.E., Cohen, S., & Ritchey, A.K. (2002). Chronic psychological

stress and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines: A gluco-

corticoid resistance model. Health Psychology, 21, 531–541.

Miller, G.E., Stetler, C.A., Carney, R.M., Freedland, K.E., & Banks,

Recommended Reading W.A. (2002). Clinical depression and inflammatory risk markers

Irwin, M.R. (2002). Psychoneuroimmunology of depression: Clinical

for coronary heart disease. The American Journal of Cardiology,

implications. Brain, Behavior and Immunity, 16, 1–16.

90, 1279–1283.

Kop, W.J. (1999). Chronic and acute psychological risk factors for

Motivala, S.J., & Irwin, M.R. (in press). Sleep and immunity: Cytokine

clinical manifestations of coronary artery disease. Psychosomatic

pathways linking sleep and health outcomes. Current Directions in

Medicine, 61, 476–487.

Psychological Science.

Maier, S.F., & Watkins, L.R. (1998). (See References)

Musselman, D.L., Lawson, D.H., Gumnick, J.F., Manatunga, A.K.,

Penna, S., Goodkin, R.S., Greiner, K., Nemeroff, C.B., & Miller,

A.H. (2001). Paroxetine for the prevention of depression induced

by high-dose interferon alfa. New England Journal of Medicine,

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Dr. Edith Chen for 344, 961–966.

helpful feedback on this manuscript, and the Michael Smith Segerstrom, S.C., & Miller, G.E. (2004). Psychological stress and the

Foundation for Health Research and the Heart and Stroke immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry.

Foundation of Canada for supporting this work. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 601–630.

Suls, J., & Bunde, J. (2005). Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk

REFERENCES factors for cardiovascular disease: The problems and implications

of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychological Bulletin, 131,

Barefoot, J.C., & Schroll, M. (1996). Symptoms of depression, acute 260–300.

myocardial infarction, and total mortality in a community sample. Yirmiya, R. (1996). Endotoxin produces a depressive-like episode in

Circulation, 93, 1976–1980. rats. Brain Research, 711, 163–174.

272 Volume 15—Number 6

You might also like

- IAS Biology Student Book 1 (2018) AnswersDocument74 pagesIAS Biology Student Book 1 (2018) AnswersGazar76% (33)

- MD Michael Cutler ChelationDocument98 pagesMD Michael Cutler Chelationabazan100% (5)

- Katy Bowman - Don't Just Sit There-Propriometrics Press (2015)Document78 pagesKaty Bowman - Don't Just Sit There-Propriometrics Press (2015)Jana Henri100% (2)

- DocxDocument4 pagesDocxJessica nonyeNo ratings yet

- Stress Pshycology - B InggrisDocument4 pagesStress Pshycology - B Inggrisalfian khoirun nizamNo ratings yet

- Cohen 2007 Stress and DiseaseDocument3 pagesCohen 2007 Stress and DiseaseBilly CooperNo ratings yet

- Does Stroke Cause Depression?: Neuropsychiatric Practice and OpinionDocument5 pagesDoes Stroke Cause Depression?: Neuropsychiatric Practice and OpinionkennydimitraNo ratings yet

- Life Event, Stress and IllnessDocument10 pagesLife Event, Stress and IllnessMira TulusNo ratings yet

- Depressive SintomysDocument6 pagesDepressive SintomysBráulio LimaNo ratings yet

- Task Resume Article - B InggrisDocument3 pagesTask Resume Article - B Inggrisalfian khoirun nizamNo ratings yet

- DepressionDocument9 pagesDepressionErica100% (4)

- Cardiac RehabilitationDocument7 pagesCardiac RehabilitationBAJA DE PESO SIN REBOTENo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Support ofDocument13 pagesPsychosocial Support ofJEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- Dont Stress About ItDocument3 pagesDont Stress About ItHan YiNo ratings yet

- Impacts of StressDocument7 pagesImpacts of StressMovie CentralNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology Perspectives Canadian 6th Edition Dozois Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument33 pagesAbnormal Psychology Perspectives Canadian 6th Edition Dozois Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFannerobinsonebnxfojmza100% (16)

- Inflammation: The Common Pathway of Stress-Related Diseases: Yun-Zi Liu Yun-Xia Wang Chun-Lei JiangDocument11 pagesInflammation: The Common Pathway of Stress-Related Diseases: Yun-Zi Liu Yun-Xia Wang Chun-Lei JiangFebyan AbotNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Solutions To DepressionDocument178 pages21st Century Solutions To DepressionGustavo Silva0% (1)

- Cuarta Revolucion en PsiquiatriaDocument8 pagesCuarta Revolucion en PsiquiatriaJahiberAlférezNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Treatment of Major Depression in Older AdultsDocument7 pagesAssessment and Treatment of Major Depression in Older AdultsNelson GuerraNo ratings yet

- Morbid Anxiety As A Risk Factor in Patients With Somatic Diseases A Review of Recent FindingsDocument9 pagesMorbid Anxiety As A Risk Factor in Patients With Somatic Diseases A Review of Recent FindingsAdelina AndritoiNo ratings yet

- Orion 2013Document5 pagesOrion 2013Elaine MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Post-Stroke Depression - A ReviewDocument20 pagesPost-Stroke Depression - A Reviewkenth nathanNo ratings yet

- Salivary Biomarkers of Stress, Anxiety and DepressionDocument12 pagesSalivary Biomarkers of Stress, Anxiety and DepressionJuan Camilo Benitez AgudeloNo ratings yet

- PsychoneuroimmunologyDocument23 pagesPsychoneuroimmunologyMohmmadRjab SederNo ratings yet

- Estres y AlergiasDocument8 pagesEstres y AlergiasjorgesantiaNo ratings yet

- Etiología Comorbilidad Depresión y ECVDocument26 pagesEtiología Comorbilidad Depresión y ECVLaura VargasNo ratings yet

- Emotional Rescue - The Heart-Brain ConnectionDocument9 pagesEmotional Rescue - The Heart-Brain ConnectionMatt AldridgeNo ratings yet

- Medical Hypotheses 9: 331-335, 1982Document5 pagesMedical Hypotheses 9: 331-335, 1982Omar DaherNo ratings yet

- Shulman 2015Document16 pagesShulman 2015Deniz SinanoğluNo ratings yet

- Stress and The Immune SystemDocument4 pagesStress and The Immune SystemFutuwwah AlFata100% (1)

- Effects of Stress and Psychological Disorders On The Immune SystemDocument7 pagesEffects of Stress and Psychological Disorders On The Immune SystemTravis BarkerNo ratings yet

- 11 Ch14 Stress F1Document2 pages11 Ch14 Stress F1MelindaNo ratings yet

- 1993 Wheatley Et Al Stress and IllnessDocument7 pages1993 Wheatley Et Al Stress and Illnessandy19791No ratings yet

- (2008) Adapted Cold Shower As A Potential Treatment For DepressionDocument7 pages(2008) Adapted Cold Shower As A Potential Treatment For DepressionPetite PoubelleNo ratings yet

- Cure Therapeutics and Strategic Prevention: Raising The Bar For Mental Health ResearchDocument7 pagesCure Therapeutics and Strategic Prevention: Raising The Bar For Mental Health ResearchShivaniDewanNo ratings yet

- 2020 Nemeroff - DeP ReviewDocument15 pages2020 Nemeroff - DeP Reviewnermal93No ratings yet

- Defining Stress: Leading Causes of StressDocument8 pagesDefining Stress: Leading Causes of StressAdrian MazilNo ratings yet

- The Healthy LifeDocument24 pagesThe Healthy LifeCristy PestilosNo ratings yet

- Polsky 2005Document7 pagesPolsky 2005Tatiana FlorianNo ratings yet

- Depression Inflammed Multidimensional ModelDocument9 pagesDepression Inflammed Multidimensional ModelantonioNo ratings yet

- Palazidou 2012Document19 pagesPalazidou 2012gharrisanNo ratings yet

- Chapter14stressandhealth 150214191358 Conversion Gate02Document60 pagesChapter14stressandhealth 150214191358 Conversion Gate02John Carlo Fariñas SuyuNo ratings yet

- Depression and ObesityDocument7 pagesDepression and Obesityetherealflames5228No ratings yet

- Immune Dysregulation Among Students Exposed To Exam Stress and Its Mitigation by Mindfulness Training - Findings From An Exploratory Randomised TrialDocument11 pagesImmune Dysregulation Among Students Exposed To Exam Stress and Its Mitigation by Mindfulness Training - Findings From An Exploratory Randomised TrialPatricia Elena ManaliliNo ratings yet

- Research Ann MurphyDocument12 pagesResearch Ann Murphyapi-583757945No ratings yet

- Allostasis and Allostatic Load: Implications For NeuropsychopharmacologyDocument17 pagesAllostasis and Allostatic Load: Implications For NeuropsychopharmacologytmaillistNo ratings yet

- Written Report Abnormal PsychologyDocument23 pagesWritten Report Abnormal PsychologyCy Esquibel LingaNo ratings yet

- Inflammatory Biomarkers Predict DepressiDocument10 pagesInflammatory Biomarkers Predict DepressiFelia AlyciaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Depression, AnxietyDocument14 pagesThe Relationship Between Depression, Anxietygerard sansNo ratings yet

- J Jocn 2017 09 022Document5 pagesJ Jocn 2017 09 022ÁngelesNo ratings yet

- Impulsivity and Its Relationship With Anxiety, Depression and StressDocument23 pagesImpulsivity and Its Relationship With Anxiety, Depression and Stressmel. tedNo ratings yet

- Association Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and MSDocument13 pagesAssociation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and MSKatherineNo ratings yet

- Appreciation of PhilosophyDocument6 pagesAppreciation of PhilosophyShan ElahiNo ratings yet

- Stress: and The IndividualDocument9 pagesStress: and The Individualsamon sumulongNo ratings yet

- Celhar and Fairhurst - 2017 - Modelling Clinical Systemic Lupus Erythematosus SDocument13 pagesCelhar and Fairhurst - 2017 - Modelling Clinical Systemic Lupus Erythematosus SGabriela MilitaruNo ratings yet

- Problem With DSM-5Document2 pagesProblem With DSM-5Carlos LizarragaNo ratings yet

- Background - : Original ResearchDocument21 pagesBackground - : Original ResearchDiane Troncoso AlegriaNo ratings yet

- Bystritsky Anxiety Treatment Overview Pharm Therap 2013Document14 pagesBystritsky Anxiety Treatment Overview Pharm Therap 2013Amanuel MaruNo ratings yet

- Metilcobalamina No Ritimo Circadiano Artigo CientíficoDocument27 pagesMetilcobalamina No Ritimo Circadiano Artigo CientíficoRenata LippiNo ratings yet

- Psych 101 Chapt 12 Spring FallupdatedDocument73 pagesPsych 101 Chapt 12 Spring FallupdatedEJ GaringNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Depression in Primary CareDocument8 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Depression in Primary CareMaria Jose OcNo ratings yet

- Depression Inflammed Multidimensional ModelDocument9 pagesDepression Inflammed Multidimensional ModelantonioNo ratings yet

- Neurobiology of Hedonic Tone: The Relationship Between Treatment-Resistant Depression, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, and Substance AbuseDocument17 pagesNeurobiology of Hedonic Tone: The Relationship Between Treatment-Resistant Depression, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, and Substance AbuseantonioNo ratings yet

- Depresion Citokinas SuicidioDocument1 pageDepresion Citokinas SuicidioantonioNo ratings yet

- Botanical PsychopharmacologyDocument21 pagesBotanical PsychopharmacologyantonioNo ratings yet

- Psicobiologia de La DepresionDocument22 pagesPsicobiologia de La DepresionantonioNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Neuro-Immune Mechanisms Regulating Social Behavior: Dopamine As Mediator?Document18 pagesHHS Public Access: Neuro-Immune Mechanisms Regulating Social Behavior: Dopamine As Mediator?antonioNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Perforatum For Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder inDocument17 pagesNIH Public Access: Perforatum For Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder inantonioNo ratings yet

- Inflamation DepressionDocument12 pagesInflamation DepressionantonioNo ratings yet

- HSJ Gaba Sindrome Metab VidDocument80 pagesHSJ Gaba Sindrome Metab VidantonioNo ratings yet

- Radiographic Pathology For Technologists 7th EditionDocument68 pagesRadiographic Pathology For Technologists 7th Editionmilkah mwauraNo ratings yet

- Case Study3Document13 pagesCase Study3Nadine FormaranNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology and Risk Factors of Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument55 pagesPathophysiology and Risk Factors of Coronary Artery DiseaseShirinNo ratings yet

- Global Atlas About CV Disease by WHODocument164 pagesGlobal Atlas About CV Disease by WHOLouisette AgapeNo ratings yet

- Artículo Dislipemia ESCDocument12 pagesArtículo Dislipemia ESCSMIBA MedicinaNo ratings yet

- Apollo Hospitals DhakaDocument143 pagesApollo Hospitals DhakamunaNo ratings yet

- Aam 5Document65 pagesAam 5iosifpaulNo ratings yet

- Linus Pauling - My Love Affair Vitamin CDocument11 pagesLinus Pauling - My Love Affair Vitamin CEbook PDF100% (1)

- Pathology Course Audit-3Document26 pagesPathology Course Audit-3Joana Marie PalatanNo ratings yet

- Cripto Stroke PDFDocument19 pagesCripto Stroke PDFDimas PrajagoptaNo ratings yet

- CASEOFAFZONDocument6 pagesCASEOFAFZONMark Francis BalatayNo ratings yet

- Written Report Coronary Heart DiseaseDocument5 pagesWritten Report Coronary Heart DiseaseJade WushuNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis A Review: Imedpub JournalsDocument6 pagesPathogenesis of Atherosclerosis A Review: Imedpub JournalsHaydee RocaNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular DisordersDocument4 pagesCardiovascular DisordersJA BerzabalNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Diagnosis and Management of Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia PDFDocument14 pagesGuidelines For The Diagnosis and Management of Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia PDFai_tNo ratings yet

- CVS 1 PDFDocument24 pagesCVS 1 PDFafaq alismailiNo ratings yet

- Rina AmeliaDocument12 pagesRina AmeliaDerison MarsinovaNo ratings yet

- Coronary Artery Disease CAD PathophysiologyDocument5 pagesCoronary Artery Disease CAD PathophysiologyKusum RoyNo ratings yet

- ArteriosclerosisDocument8 pagesArteriosclerosisRhea Liza Comendador-TjernmoenNo ratings yet

- CHW TrainingDocument490 pagesCHW TrainingsereneshNo ratings yet

- WBI01 01 Rms 20180308 PDFDocument21 pagesWBI01 01 Rms 20180308 PDFxinyu wuNo ratings yet

- Atherosclerosis: Jason Ryan, MD, MPHDocument23 pagesAtherosclerosis: Jason Ryan, MD, MPHasdNo ratings yet

- Coronary Microvascular Obstruction in Acute Myocardial InfarctionDocument14 pagesCoronary Microvascular Obstruction in Acute Myocardial InfarctionGerry ValdyNo ratings yet

- PHYS 3616E Chap91Document15 pagesPHYS 3616E Chap91johnNo ratings yet

- Coronary Artery Heart Disease CDDocument28 pagesCoronary Artery Heart Disease CDchristinaNo ratings yet

- Benefits of SmokingDocument3 pagesBenefits of SmokingZainab Abizer MerchantNo ratings yet

- Heart Disease Diagnosis and Prediction Using Machine Learning and Data Mining Techniques: A ReviewDocument25 pagesHeart Disease Diagnosis and Prediction Using Machine Learning and Data Mining Techniques: A ReviewJhon tNo ratings yet