Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Social Histories of Old Age and Aging

Social Histories of Old Age and Aging

Uploaded by

Alexis Flores CórdovaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Histories of Old Age and Aging

Social Histories of Old Age and Aging

Uploaded by

Alexis Flores CórdovaCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Histories of Old Age and Aging

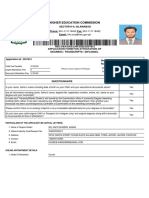

Author(s): Pat Thane

Source: Journal of Social History, Vol. 37, No. 1, Special Issue (Autumn, 2003), pp. 93-111

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3790315 .

Accessed: 18/09/2013 02:40

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of

Social History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING1

By Pat Thane University of London

One of the many important changes in approaches to social history in many

countries in recent decades has been increasing awareness of the multiple forms

of social diversity within all societies and, in consequence, the need for greater

complexity of analysis. Whereas in the nineteen sixties and early seventies so?

cial historians perceived class as the primary social division, increasingly the

importance of gender, ethnicity and, more recently religious belief, region and

age have been recognized, and historians have learned to seek to understand

and relate these multiple diversities to one another. Much of my recent work

has been engaged with the history of and social meanings of aging and old age,

an important phase of life throughout history but one which, with a cluster of

rare exceptions written in the nineteen seventies,2 was hardly at all studied by

historians until comparatively recently. It is field of study which has engaged

closely with work in other disciplines in the Humanities and Social Sciences,

and which requires, if all of its dimensions are to be understood, engagement

with a wide range of qualitative and quantitative methods. Like many areas of

social history it has gained from the insights of the 'cultural turn' whilst contin?

uing to benefit from and to develop older approaches drawn from demographic,

economic and political history. Ideally, it fuses all of these approaches. I hope

that a brief survey of recent work in this field will contribute to discussion about

the current state and, I believe, the continuing strength, of social history.

The skepticism of historians about simplified grand narratives, combined with

the use of a greater variety of sources to explore the past (literary, visual and

personal for example, as well as statistical and official sources) has, in recent years,

moved us towards a more complex understanding of the historical experience of

old age. This is appropriate for the stage of life which encompasses greater variety

than any other. It can be seen, in any time period, as including people aged from

their fifties to past one hundred; those possessing the greatest wealth and power,

and the least; those at a peak of physical fitness and the most frail. In consequence

of this variety many different histories and fragments of histories of old age are

emerging. This does not imply that there are no overarching narratives, that

the history of old age is no more than an accumulation of small stories; rather

it suggests that we are at an exciting, if incomplete, stage of assembling both

small and large stories about different times and places in the search for a more

complete history of old age.

This process encompasses the different preoccupations of historians of dif?

ferent national and cultural backgrounds. Histories of old age in Britain have

been centrally preoccupied with demography and material concerns: the num?

bers of old people, their geographical distribution, their living arrangements;

with household structures and family relationships; with welfare arrangements,

medical provision, property transactions, work and retirement. Studies in France

have not neglected these obviously important matters, especially demographic

studies, which in their modern form were invented in France, or the history of

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

94 journal of social history fall 2003

medicine; but more attention has been paid to representations of old age, to

how the idea of old age has been constructed in the past3. The relatively sparse,

but fine, work on old age in Germany4 provides examples of both approaches,

as do the more extensive studies of the United States and the growing body

of work from, and about, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. This essay fo?

cuses, regrettably, upon studies of Europe, North America and other societies

strongly influenced historically by White, European culture. There is a need for

more studies of old age in other cultures and for comparisons across cultures

which transcend a common and misleading trope of popular and social science

discourse which compares a 'western' experience of ageing with a romanticized

other, where older people are respected and cared for, as they are said no longer

to be in 'our' culture. There are important discursive and structural differences

in inter-generational relationships across different cultures but they have them?

selves changed over time and are less fixed and simple than is sometimes thought.

Even within the cultures of Europe/North America/Australasia it is difficult

to examine similarities and differences in the experience and treatment of old

age and aging between different countries and regions as systematically as is,

in principle, desirable. There have been important gaps in historical writing in

all countries and for many places and times. New approaches are being drawn

upon in the study of old age, though sometimes extremely slowly. For example,

awareness of gender is hardly a novelty in historical scholarship, but it has been

surprisingly slow to enter studies of old age, in view of the predominance of

women among older people in many times and places.5 This is perhaps because

historians share the, mistaken, view of Georges Minois that until the relatively

recent past, the history of old age is largely a history of men, because few women

survived the rigours of childbirth to reach old age6; or that ofthe medievalist,

Joel Rosenthal that "Matriarchy and the culture of old women, whether on their

own or in extended family households, is mostly a lost topic, worth investigation,

but hard to treat other than anecdotally."7 Historians have recently proved them

both wrong, through the imaginative use of a wide range of sources.8

A full history of old age must unite all of the approaches currently available

to historians, and no doubt others of which we are not yet aware. We need to

draw together historical knowledge of the demographic and material experience

of old age in different times and places with cultural histories of representation

and self-representation and of the varieties of experience of older people, since

these approaches to history can never be wholly separate from one another. Im?

age is not distinct from experience, nor cultural history from economic, social

and political history. Cultural representations of old age, whether drawn from

philosophical or medical texts, literature, paintings, film, recorded expressions

of everyday opinion or any other source, shape individual imaginings of the

life course and hence individual and collective action. If people are culturally

conditioned to expect to be dependent and helpless past a certain age, they are

more likely to become so, with consequences for their own lives and those of

others, which may include provision of formal or informal welfare services. Re-

ciprocally, what takes place in the political and economic spheres?for example

the provision of retirement pensions?helps shape private experiences and per?

ceptions. Official sources such as those of poor relief administration or debates

about pensions policy in representative assemblies tell us much about political

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING 95

and administrative history, but they are also texts which can reveal a great deal

about the cultural construction of old age in past societies.

How far have we come in integrating these various approaches? To begin with

the demographic picture. Did people in 'the past' grow old? Clearly they did,

and in larger numbers than is often thought. However the numbers surviving to

what was defined as 'old age' varied across time and place. English population

figures have been studied over a long time period. Life expectancy at birth in

England averaged around thirty-five years between the 1540s and 18009 and is

unlikely to have been higher at any earlier time. But the high infant mortality

rates at all times before the mid-nineteenth century drasticaily pulled down such

averages. Those who survived the hazardous first years of life had, even in the

sixteenth century, a respectable chance of living at least into what would now be

defined as middle age, and often longer.10 It is estimated that the proportion of

the English population aged over sixty fluctuated between six and eight per cent

through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. But the numbers varied from

place to place. In the rapidly growing town of Manchester, full of young migrants

at the end of the eighteenth century, during the industrial revolution, only 3.4

per cent of the population was over the age of sixty, 1.9 per cent over seventy.

In depressed rural Sussex, which young people were fleeing in search of work in

the towns, nineteen per cent were over sixty, seven per cent over seventy. The

national average fell to six per cent in the nineteenth century, when high birth

rates raised the percentage of the very young. Then from the late nineteenth

century through to the late twentieth, as birth rates dropped and death rates in

childhood, youth and middle age fell, came the long climb in the proportion

of the population living past sixty: six per cent in 1911, fourteen per cent in

1951, eighteen per cent in 1991. Most developed countries have experienced

this climb in the twentieth century.11

France, by contrast, experienced falling rather than rising birth-rates in the

nineteenth century, which influenced the overall age structure. In the mid eigh?

teenth century seven to eight per cent of the population were aged sixty or

above. By 1860 the proportion was ten per cent; by the early twentieth century

twelve per cent, by 1946 fourteen per cent.12

In Britain, women were a clear majority among those aged 60 and above from

the time that vital statistics began to be officially and comprehensively recorded,

in 1837; and women appear to have had a longer life expectancy, on average, in

Britain and elsewhere in Europe for long before. Medieval commentators noted

that women seemed to have the longer life expectancy and wondered how that

could be when it seemed natural that men were stronger and should live longer.13

Physicians in eighteenth century France were still puzzled by the consistency with

which females 'went against nature' and outlived men. It is sometimes thought

that before at least the nineteenth century female life expectancy must have

been sharply reduced by the ravages of death in childbirth.14 But though such

deaths undoubtedly, tragically, occurred more frequently than in the twentieth

century, childbirth was never a mass killer of women in western societies.15 It

was not comparable with the ravages of work, war and everyday violence on the

lives of men.16 In France in the mid-nineteenth century there were more old

men than old women, but by the time ofthe First World War women had gained

the advantage in life expectancy, which they have never since relinquished.17

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

96 journal of social history fall 2003

If there were divergent demographic experiences within the 'old world' of

Europe, the 'new world' of outposts of European culture far from Europe, was

different again. Migrant countries disproportionately imported males. Hence in

Australia and New Zealand by the later nineteenth century, most older people

were male. In Ontario, Canada, the balance shift ed from a majority of older

men in 1851, to a female majority in 1901.18 In the United States the picture

varied from place to place, according to length of settlement. Women in the

US are estimated, on average, to have had a lower life expectancy than men

from the mid-seventeenth century to the eighteen nineties.19 The proportion of

the US white population aged sixty and above rose steadily from four per cent

in 1830 to 6.4 per cent in 1900 to 12.2 per cent in 1950. The survival rates of

black Americans were somewhat lower;20 and those of native Americans (as of

Australian aboriginal people) one assumes, considerably so. Another absence in

historical work on age ing concerns such excluded and persecuted groups. The

population of Ontario aged as the colony made the transition from migration

to long-established settlement. Three per cent of the population was aged over

sixty in 1851, 4.6 per cent in 1871, 8.4 per cent in 1901.21 Different 'western'

societies indeed 'aged' at different paces and with different gender balances. It

took France 140 years to double its population of people over aged 60 from

nine per cent to eighteen per cent (from 1836-1976), Sweden, 86 years (1876?

1962), the United Kingdom 45 years (1920-65); the proportion over 60 had

not reached eighteen per cent in the USA by the end of the twentieth century.

Such varying paces of demographic change had probable, broad cultural effects

on the societies in which they occurred, but these have barely been explored.22

The growing proportions of older people in western societies over the twenti?

eth century have, periodically, caused panics which are revealing about attitudes

to old age, and of much else, in those societies. This panic first became acute

in the nineteen twenties, at least in France and Britain, the only countries

for which it has been studied.23 The combination of rapidly falling birth-rates

and lengthening life-expectancy in a period when there was a perceived mil?

itary threat from apparently 'younger' countries, in particular Germany, and a

perceived cultural threat from the growth of non-white populations in other

continents, produced in France and Britain doom-laden predictions from de-

mographers and social scientists about the social conservatism and economic,

imperial and military decline which was anticipated, as these nations lost their

youthful vitality. In France, according to Bourdelais, such fears reinforced nega?

tive views of old age. In Britain, however, the initial negative assessment of an

'ageing society' led to demonstrations ofthe positive capabilities of older people

(at work, for example) and to government-led attempts to improve both their

social conditions and their cultural value, though with only partial success.24

The panic about ageing in the mid-twentieth century, which was replicated

in the nineteen eighties and nineties, suggests a close link between demographic

change and cultural change: that changing proportions of old people in a society

may influence attitudes towards them and affect their own behaviour. But the

different responses in Britain and France to similar demographic situations in

the twentieth century suggests that the relationship between demography and

culture is complex, variable and, as yet, little understood. A similar contrast

can be found in interpretations of the eighteenth century, for much of which

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING 97

both the proportions of older people and the average expectancy of living to

later ages in the two countries was comparable, in both cases rising. In France

this has been seen?by means of the use of a great variety of sources?as a

period in which older people came into favour and acquired a positive image,

in contrast to previous denigration.25 One sign of this increased social esteem

was the establishment of pensions for public servants for the first time. No

parallel change in esteem has been detected in Britain. Rather, by the end

of the century impoverished old people were less rather than more likely to

receive poor relief. The eighteenth century in Britain also saw the introduction

of systematic pensions for public servants, but, rather than signs of esteem, these

were outcomes of the professionalization of government: pensions explicitly

provided an acceptable means to rid the public service of those thought to have

aged past their usefulness.26 Similar demographic regimes may have different

cultural outcomes in different social, economic and political contexts.

But how much can age-based statistics tell us about any society? Convention-

ally gerontologists and demographers choose sixty or sixty-five as the lower limit

of'old age'. It is essential to choose a fixed age threshold if statistical comparisons

of age structure are to be made over time. But have these ages always had the

same cultural meanings? Sixty and sixty-five are the ages at which state or private

pensions are most frequently paid in present-day societies and they have become

common ages of retirement from paid work. These ages were generally fixed early

in the twentieth century when both pensions and retirement gradually became

normal features of ageing in most developed countries (nowhere were they uni?

versal before the nineteen forties). At that time they were thought?probably

accurately?to approximate the ages at which most people were no longer fit for

full-time work. Standards of physical fitness of people in their sixties rose in most

western countries over the twentieth century. In some countries, ages of retire?

ment were raised or abolished at the end ofthe century, though in others they fell

for reasons connected with the state of the national and international economy,

or with personal preference, rather than with physical aptitude.27 Increasingly,

physical condition was detached from social and bureaucratic markers of 'old

age' and established age boundaries were destabilized. Were they more stable

in the more distant past? Did people become 'old' at earlier ages in previous

centuries when living standards were lower for most people?

The concept of old age was firmly present in all known past cultures and it

had multiple meanings and uses. Significantly, the ages of sixty and seventy have

been used to signify the onset of old age in formal institutions in Europe at least

since medieval times. Sixty was long the age at which law or custom permitted

withdrawal from public activities on grounds of old age.28 Even in ancient Greece

the formal obligation to military service did not end until age sixty and men in

their fifties were indeed conscripted.29 In ancient Roman writings people were

defined as old at ages varying from the early forties to seventy.30 In medieval

England, in a succession of enactments from the Ordinance of Labourers of 1349

onwards, men and women ceased at sixty to be liable for compulsory service

under the labour laws, for prosecution for vagrancy or for performing military

service. From the thirteenth century, seventy was set as the upper limit for jury

service.31 Similar regulations held elsewhere in Europe. It can be argued that

governments generally had an incentive to set such age boundaries as high as

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

98 journal of social history fall 2003

possible, especially when they might exact taxation in lieu of service. However,

it is unlikely that such age-limits could have been set at levels far removed from

popular perceptions of the threshold of old age.32 Furthermore, there was in

medieval and early modern Europe (and this remains so in many societies in the

early twenty-first century) no fixed retirement age for many elite positions, and

appointments could be made at advanced ages.

On the other hand, it was long assumed that most manual workers could not

remain fully active at their trades much past age fifty, especially when perfor?

mance depended upon such physical attributes as good eyesight. Literary evi?

dence from the sixteenth century suggests that the fifties were regarded as the

declining side of working maturity, the beginning of old age, as is still popularly

assumed. For women old age was often thought to start earlier, in the late forties

or around fifty, when the physical concomitants of menopause became visible;33

for men the defining characteristic was capacity for full-time work. For both men

and women in pre-industrial Europe old age was defined by appearance and by

capacities rather than by age-defined rules about pensions and retirement, hence

people could be defined as 'old' at variable ages. English poor relief records of

the eighteenth century first describe some people as 'old' in their fifties, others

not until their seventies. Supplicants for public service pensions in eighteenth

century France ranged in age from 54 to 80 years.34

This suggests that over many centuries 'old age' has been defined in differ?

ent ways in different contexts and for different social groups. Old age is defined

chronologically, functionally or culturally. A fixed threshold of 'chronological'

old age has long been a bureaucratic convenience, suitabie for establishing age

limits to rights and duties, such as access to pensions or eligibility for public

service. It became more pervasive in the twentieth century, when societies be?

came more rigidly stratified by chronology, especially earlier and later in life,

as ages were fixed for attending and leaving school, for retirement and receipt

of pensions. 'FunctionaP old age is reached when an individual cannot perform

the tasks expected of him or her, such as paid work. 'Cultural' old age occurs

when an individual 'looks old', according to the norms of the community, and

is treated as 'old'. This combines aspects of the other modes of definition; it is

an expression of the value system of the community and may define individuals

as old according to codes of dress or other commonly accepted signifiers. Un-

doubtedly a high proportion of survivors in medieval and early modern society

felt and looked 'old' at earlier ages than has become the norm in the second half

of the twentieth century. In consequence the numbers of people who appeared

to be 'old' in past communities might have been greater, and consequently they

would have been a more visible cultural presence than is revealed simply by

calculation of the numbers past age sixty.

Also, it has long been recognized that there is immense variety in the pace

and timing of human ageing, that people do not all age at the same rate or in the

same ways. In consequence, since antiquity35 old age has long been divided into

stages. Some of these were elaborate, such as medieval 'ages of man' schema,

which divided life into three, four, seven or twelve ages.36 These stylized age

divisions often had didactic or metaphorical purposes. More commonly, in ev?

eryday descriptive discourse, old age has been divided into what in early modern

England was called 'green' old age, a time of fitness and activity, with perhaps

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING 99

some failing powers, and the later, last, phase of decrepitude; a division which

in the twentieth century is less imaginatively labeled 'young' and 'old' old age,

or, in France, the Third and Fourth ages. Texts referring to the decrepit final age

cannot be taken to express attitudes to old age in general. The sad decline with

which some, but not all, older lives end has never been represented positively,

in any age or culture, with good reason.37

Historians have also discovered more about the ways in which older peo?

ple supported themselves and were supported in different times and places and

consequently about how they lived and perceived their own lives. Such pub?

lic documents as wills, legal documents, inventories, poor relief records, census

statistics, records of pension funds and such private ones as diaries, letters, biogra-

phies and autobiographies can be combined to provide a greater understanding

of these processes. Again the picture is one of variety, among social groups and

across space and time.38

Some older people, of course, have always possessed property, often in sub-

stantial amounts,39 with which they could support themselves to the end of life,

employing others to care for them, if necessary, either in institutions or in their

own households. From at least medieval times in most west European countries

ageing individuals could legally assign property to relatives or non-relatives in

return for guaranteed support until death, and they could invoke the protection

of the law if the agreement was not honored. Old people determinedly sought

to control their own lives and to retain their independence throughout Europe,

North America and Australasia through time. For the propertyless and impov-

erished there was, through most of time, little choice but to work for pay for

as long as possible, whereas the propertied minority could in all times afford to

retire from work when they chose.40 As states, and later business enterprises, be?

gan to bureaucratize on modern lines, from the eighteenth century, and became

concerned to maintain the efficiency of their officials, pensions were introduced

to encourage retirement when ageing was thought to impair performance.41

The poorest people expected, and were expected to, work to late ages. In

a census of the poor taken in Norwich, England in 1570, three widows, aged

74, 79 and 82 were described only as 'almost past work' and they were still

earning small sums at spinning.42 This remained so in most western countries

until the twentieth century. Poor relief systems encouraged older people to work,

supplementing but not replacing meagre incomes for both men and women. In

early modern Europe, most communities provided specified tasks for older people.

Such activities as road mending, caring for the churchyard, fetching, carrying or

caring for horses on market days were tasks for old men. It was often easier for

women to support themselves at later ages. They could care for children, engage

in casual domestic labour, such as cleaning or washing; commonly they earned

an income by taking in lodgers, running small shops or alehouses.43

This unremitting lifetime toil was relieved for the poorest people with the

emergence of retirement as a normal phase of life only in the mid twentieth cen?

tury. Census data can give the impression that mass retirement first emerged in

the later nineteenth century, but deconstruction of the US and British censuses

(there appear to be no equivalent studies of other countries) demonstrates that

most of the apparent nineteenth century decline in employment at older ages

was due to the decline of agriculture. Retirement from white-collar occupations,

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

100 journal of social history fall 2003

combined with improved occupational pensions was visible through the first

half of the twentieth century. Retirement from blue-collar occupations did not

increase significantly until the nineteen forties and beyond.44

Why did retirement become a mass phenomenon at this time? Attempts to

explain it as a feature of capitalist manipulation ofa reserve army of labour45 are

unconvincing, since the most rapid spread of retirement coincided with the post

second world war labour shortage in most developed countries, when older people

were needed in the labour force rather than in reserve. Rather, retirement became

a social norm along with the introduction of improved pensions, provided by

the state, which promised at least tolerable incomes in later life. This coincided

with increased capacity of relatives to help in a period of generally rising living

standards and full employment. Individuals chose at the end of life the leisure

always previously denied them, though by the end of the twentieth century

increasing numbers of people retired in their fifties, sometimes willingly, often

under pressure from management engaged in 'downsizing' their operations.46 As

retirement became a norm it perhaps reinforced the prevailing view of business

management that older people were marginal workers, and popular views of

older people as redundant and dependant. Once again, cultural and material

phenomena were mutually retnforcing.

Older people who had little or no savings or property, and who could not earn a

living from a single source of employment throughout time have been locked into

what early modern historians term an 'economy of makeshifts', and twentieth

century economists less picturesquely label 'income packaging': pulling together

a shifting variety of resources for survival. There has been much debate among

historians about the role of family support in these individual economies.

It has long been clear that as far back in time as can be traced, it has not

been the norm in all 'western' societies for older people to share households

with their married children. To do so was conventional in Mediterranean so?

cieties and in some north European peasant cultures, such as Ireland and parts

of France, where land was the family's only asset and the heir shared land and

household with the elders until their death.47 In much of north-western Europe,

however, elders retained control of their own households for as long as they were

able, rarely sharing them with adult married children, though they might move

to the home of a relative when they were no longer capable of independence,

perhaps for a short time before death. North European folklore, even in me?

dieval times, expressed few illusions about inter-generational support, but long

conveyed wamings ofthe danger to older people of placing themselves and their

possessions under the control of their children. Such stories achieved their most

sublime expression in William Shakespeare's King Lear, itself a re-working of a

number of medieval folktales. In the eighteenth century the gates of some towns

in Brandenburg were hung with large clubs bearing the inscription:

He who made himself dependent on his children for bread and suffers from want,

he shall be knocked dead by this club.48

Most countries incorporated into law some obligation upon adult children

and sometimes other close relatives to support their elders.49 How frequently

such practices were implemented was variable, not least because the kin of

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING 101

the aged poor were often very poor themselves and could not realistically be

expected to give support from already inadequate resources.50 The customs and

practices ofthe Old World were transported to the New, with adaptations to new

circumstances. Settler societies gave even greater salience to the independence

and self-help which were necessities for survival in the early years, and such

societies necessarily took time to build the communal, often religious based,

institutions which supplemented self- and family support in much of Europe.51

But the fact that older people did not conventionally share a home with close

relatives, and determinedly retained their independence, does not mean that

there were not close emotional ties and exchanges of support between the gen?

erations. Before his death Peter Laslett softened his belief in the universality of

the nuclear family in pre-industrial Europe and the slight obligations of younger

to older generations, and recognized the variability of family forms and relation?

ships in European history,52 though this is not to question the importance of his

original challenge to the sociological orthodoxy that the extended family was

the norm in 'pre-industrial' societies.53 Parents and adult offspring might not

share a household, but they often lived in close proximity. Generally in west?

ern societies 'kinship did not stop at the front door'.54 The Austrian sociologist

Leopold Rosenmayr has described the north European family as characterized

by 'intimacy at a distance',55 the intimacy being as important as the distance.

Family members at all social levels have been found to have exchanged support

and services from a mixture of material, calculative and emotional motives.56

That it was often an exchange relationship should be emphasized. Older people in

the past, as now, were rarely simply dependent upon others, unless they were in

severe physical decline. They cared for grandchildren, for sick people, supported

younger people financially when they could afford it and performed myriad other

services for others. With lengthening life expectancy, over time the co-existence

of three or more generations and hence the opportunity for exchange became

more frequent.57 Although over the twentieth century increasing numbers of

old people have lived alone, they are relatively rarely isolated or neglected by

younger relatives. Rather, greater numbers are able to seize the opportunity pro?

vided by greater affluence to preserve the independent control of their own lives

for which older people have long aspired.58

The importance of such intergenerational exchange has been underestimated

by historians because it often took the form of services or gifts in kind which are

difficult to trace historically because there was no reason for systematic records

of such private, non-monetary, transactions to be taken or to survive. It was a

taken-for-granted activity of everyday life of the kind that is most difficult to

reconstruct in the distant past. Even the participants might so take for granted

such transfers that they denied their significance, as when a 67 year old retired

market gardener gave evidence to a British Royal Commission of Enquiry into

the Condition of the Aged Poor in 1895. He lived alone in a country village.

He had a cottage and garden, rented an allotment and kept a pig or two; both

were useful sources of food and of earnings and/or exchange. He had occasional

earnings from road mending. When asked if his five surviving children gave

him help, he replied: "No, I have had to help them when I can. They have got

large families most of them. I do what I can in that sense. I do not get anything

from them in any way. The daughter that I have lives the length of this room

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

102 journal of social history fall 2003

perhaps from me and she looks after my house." His daughter's housework was a

service which must have contributed greatly to his comfort and to his capacity

for independent living, but he so took it for granted that he did not define

it as 'help'. In other respects this man's story exemplifies family relations and

the survival strategies of older people, which were not peculiar to England or

to the later nineteenth century. His children were too poor and too burdened

with children to given him financial support; instead he gave support to them

when he could. He was no longer in regular paid work but packaged together

a living from the produce of his garden and from occasional earnings. It would

be surprising if he did not sometimes share meals with his daughter's family and

give them some produce from his garden, both common forms of intra-familial

exchange among those too poor to offer cash, part of the network of exchange

which held together poor communities through the ages, enabling survival in

conditions of poverty.59

Not all older people had families to support them through the centuries when

high death rates meant that parents might outlive children. It has been es?

timated that up to one-third of women who lived to the age of sixty-five in

seventeenth and eighteenth century England had no surviving children. By the

mid-nineteenth century perhaps two-thirds of sixty-five year olds had surviv?

ing children. In eighteenth century France the average age at which a person

became both fatherless and motherless was 29.5; in the nineteen seventies it

was fifty-five.60 Geographical mobility in centuries when transport was slow and

many people were illiterate might break contacts even with survivors. Migrants

to faraway, 'new' countries often lacked older relatives around them, though

they strove to keep in touch with them at a distance.

Through the twentieth century birth-rates fell in all developed and many less

developed countries, but so did death rates, and both marriage rates and levels

of fertility rose. In consequence more people had children and they survived.

In the later twentieth century, most older people with surviving children were

in close contact with some or all of them.61 At all times, recipients of welfare

relief have been more likely to be people without surviving children, which

further suggests the historical importance of family support.62 Modern forms of

communication facilitate contact even over long distances. Far from 'crowding

out' family support, as social scientists once feared, modern European welfare

states facilitate it, enabling intergenerational relationships to be easier and less

tension-ridden by removing some of the emotional and material costs from the

family. The relationships between older people and their close relatives show

striking long-run continuity and closeness in 'western' culture, even when they

do not share a household.

Even those who had no conventional families could create them. Older men

would marry younger women able to look after them; rich older women married

younger men; widowers with children married older women able to care for

them. Orphan children were adopted by older people, gaining a home in return

for giving service. Unrelated people shared households for mutual financial and

emotional support. Gay people created 'families of choice'. Examples can be

found as far apart as Norwich, England in the sixteenth century and Ontario,

Canada in the mid nineteenth century and throughout early modern and modern

continental Europe, North America and Australasia.63

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING 103

But when families have not been able, willing or available to help, many older

people have needed the support of publicly financed welfare. Not all older people

are, or ever have been, poor but in most past, and present, societies they have

been more likely than younger people to be very poor, especially if they were

female. In consequence, the study of poor relief systems and welfare states can tell

us much about the histories of the older people with whom they so often dealt.

Such studies are numerous, but they cannot tell us everything and we should be

cautious about giving this theme too much weight. A focus on the relief of the

aged poor runs the risk of conveying the message that most old people in the

past were dependent as well as poor, when very many were not, and it diverts

attention from the remainder, who were independent and sometimes wealthy.

Also there is a danger of over-estimating the importance of poor relief in the

lives of older pople because poor relief systems leave records behind whereas

other, perhaps equally important, sources of support, such as that within families

do not.

Nevertheless, poor relief and welfare have been important in the lives of many

impoverished old people and many old people have been impoverished. All

modern states have to some degree become 'welfare states', though the meaning

of this term varies from place to place and over time. In Europe modem welfare

states are profoundly marked by each country's long and varying traditions of

poor relief. These traditions were transported and transformed by migrants to

'new' countries. All European countries for many centuries had some system

of provision for the aged, and other poor, who could not help themselves and

had no family or other source of support. This was financed to varying degrees

through public taxation (probably most extensively in England, through the

mechanism of the national Poor Law which was in place from 1597 to 1948,

though it had still earlier antecedents64 ) or by philanthropy, often religious in

motivation, and institutionalization; most often by a combination of the two.

'Relief could take the form of payments in cash or kind (food, clothing, medical

care) or shelter in a hospital or workhouse. Provision was of variable quality,

within each country as well as over time, and it was guided by varied principles:

supportive, rehabilitative or punitive. Everywhere old people were numerous

among recipients of relief, along with widows and children, but nowhere did

reaching a defined age automatically qualify anyone for relief. The essential

qualification was destitution, access to insufficient resources for survival.65 Even

where the poor relief system was relatively generous66 relief could be refused

even to the very old if they were judged capable of earning some income. This

is an important contrast with modern pensions systems, which, whatever their

inadequacies, normally provide for most ofthe population on attaining a certain

age.

Countries ofthe 'new' world tended to reject publicly funded welfare systems

because initially they lacked both an established, substantial wealthy class ca?

pable of funding them and the mass of miserable poverty which required them.

Also nineteenth century migrants were often fleeing from punitive relief systems

in Europe and had no desire to replicate them. Ideologically, too, they placed a

premium upon independence and self-help. Australia and New Zealand never

introduced publicly funded poor relief systems, relying instead upon voluntary

charity, sometimes (and increasingly over time) subsidized from public funds.

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

104 journal of social history fall 2003

The picture was similar in nineteenth century Canada.68 In parts of the United

States the extent of unmet need necessitated the introduction of poor relief,

but 'welfare' early acquired and retained more stigmatizing associations than in

Europe. Most nation-states at least by the eighteenth century and commonly

in the nineteenth and twentieth, provided publicly funded pensions for public

servants and for the disabled veterans of war and sometimes for their families.

Old people were in most countries the first to benefit from the transition

from residual and often punitive poor relief systems to theoretically, and gen?

erally actually, more comprehensive and generous state welfare systems. This

was because, being mostly marginal to the labour and capital markets, they were

generally the last substantial social group to gain from the general improve-

ment in living standards which took place in the west over the course of the

nineteenth century. Also the 'deservingness' and respectability of older people

were more readily apparent to reluctant taxpayers than was the case with other

impoverished groups such as the unemployed.

Old age pensions have been introduced in all developed countries since the

eighteen eighties, but according to different principles and for different reasons

in the various countries. Where the motivation was mass deprivation among

older people due to the absence or the deterrent and stigmatizing effects of a

poor relief system, pensions were non-contributory and targeted upon the very

poor, often especially providing for women, as in Denmark in 1891, New Zealand

in 1898, most ofthe Australian states by the time of Federation in 1910 and in

Britain in 1908. Where the main motivation was pressure from, and or the de?

sire of politicians to undermine, a growing labour movement, as in Germany in

1889, they tended to be insurance based and to target primarily the securely em?

ployed, generally male worker.69 Again, different cultural and political contexts

produced different outcomes in both the origins and subsequent development

of pensions systems through the twentieth century.70

Old people have also gained from increasing medical knowledge over time.

Knowledge of the history of geriatric medicine is sparse but growing. Interest in

the physical condition of ageing people has been continuously present among

medical specialists since ancient times, though always as a minority interest. It

was for centuries uncertain whether old age should itself be defined as a disease

and for centuries little could be done to alleviate the diseases accompanying

old, or indeed younger, age other than to enjoin (as specialists still do) temper?

ance, good diet, exercise. Investigation and understanding of the pathology of

physical deterioration with ageing developed especially in nineteenth century

France, spurred partly by the increasing numbers of older people in the French

population. Only in the twentieth century did medicine acquire the capacity

to diagnose and cure extensively, and only in the mid twentieth century were

medical services sufficiently democratized in most developed countries to allow

most old people access to medical treatment. Even so, they tended to stand at

the back of the queue for such treatment, their lives deemed less valuable than

those of younger people. The specialty of geriatrics developed from the early

twentieth century, though most strongly from the nineteen-thirties, primarily

to protect older people against such discrimination and also to maintain and

enhance the physical fitness of the ageing populations of most western coun?

tries. It had only partial success. Older people have gained most from medical

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING 105

techniques designed for all age groups, such as coronary by-pass surgery, joint,

especially hip, replacements, but geriatrics remains in most countries a low status

medical specialty and older people without personal power still suffer from ex?

clusion from treatment in favour of the young, though not to any greater degree

than in the past.

Social scientists have sometimes argued that their marginalization by medical

systems, together with the spread of pensions and retirement in the twentieth

century, has increased the dependence of older people and that they have become

less valued in modern society than in some unspecified 'past'. The belief that the

status of older people is always declining has a very long history. It is discussed, and

dismissed, even in the opening pages of Plato's Republic and in a long succession

of texts through the centuries. The longevity of this narrative trope in the

discussion of old age suggests that it expresses persistent cultural fears of ageing

and neglect, and real divergences in experience in most times and places, rather

than representing transparent, dominant, reality.

Early historical enquiry into old age tended to echo this narrative of decline.

George Minois' history of old age in Western culture from antiquity to the Renais?

sance acknowledged variations and complexities in experiences and perceptions

of old age over this long time-span, but he concluded that "the general tendency

however is towards degradation." And he had no doubt that the degradation was

still greater in modern society.71 An extensive body of work on old age in the

United States since the eighteenth century finds the status old people to be in

decline over a variety of time-scales: from the late eighteenth century to the early

nineteenth,72 in the mid-nineteenth,73 between the late nineteenth and twen?

tieth centuries.74 Historians have reconstructed the different experiences ofthe

political elite ofNew England in the late eighteenth century,75 attitudes to East

Coast Protestant clergy in the late eighteenth century,76 along with studies of

labour force participation and the antecedents of social security legislation,77 or

of the emergence of geriatrics and the attitudes of social welfare professionals in

the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.78 These are mostly studies of white

males. They have tended to represent the (scrupulously researched) experience

of specific groups as representative of broader, even hegemonic values, rather

than serving as micro-studies, valuable in themselves, contributing part, rather

than representing the whole, ofa complex total picture. The fact that some older

men exerted power at a particular time is important, but it does not necessarily

suggest that all old people at that time and place were highly regarded. In all

times older people (female and male) who retained economic or any other form

of power, along with their faculties, could command, or enforce, respect. At all

times also poor and powerless older people have been, though not universally,

marginalized and denigrated.79

More recent studies of old age in ancient80 and medieval81 Europe and of

France,82 Germany83 and the United States84 in more modern times, acknowl-

edge the variety of experience in old age and abandon the pessimistic framework.

In consequence a richly textured history is emerging which is making clearer the

differences between social groups, and between times and places. For example,

Troyansky describes the new confidence with which public servants requested

pensions from the state in post-revolutionary France, asserting a sense of right

to such a reward and in the process coming self-consciously to review their lives

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

106 journal of social history fall 2003

and to imagine a model of the life-course which incorporated a period of retire?

ment at its end. All of this appears to have been new in early nineteenth century

France. In England, by contrast, ageing small landowners, male and female, can

be found in the law-courts, even in medieval times, vigorously ensuring for them?

selves a period of retirement on their own preferred terms, as they negotiated

and defended contracts in which they transferred their lands to others in return

for care and material support.85 English men and women at all social levels from

an early date wheedled pensions from monarchs, bishops and other influential

patrons, stressing the characteristics of their past lives that merited support for a

dignified old age. Even poor old people, in the nineteenth century and long be?

fore, asserted their right to poor relief in similar terms.86 The difference between

the two countries may lie in the fact that formal equality before the law was very

long-established in England, carrying with it a sense of equal rights which was

strongly held even among poor people, however imperfect the reality; whereas

in France such equality was the outcome, indeed the central objective, of the

great Revolution. Such profound legal and political differences shaped different

cultural experiences of old age. Such experiences produced texts from which

these differences can be reconstructed.

The greatly enriched histories of old age of recent years have alerted us to

the complexity of attitudes to and experiences of older age in all times and over

time, and the rich range of sources and methods through which historians can

seek to reconstruct them. It can be tempting for example to conclude, as Minois

does, that Shakespeare's dismal conclusion to the 'seven ages of man' described

by Jaques in As You Like lt: "second childishness and mere oblivion; sans teeth,

sans eyes, sans taste, sans every thing," is representative of 16th century English

perceptions of old age. If, that is, you fail to note that Jaques is a relatively

young man, but is given the conventional literary attributes of an old man,

such as melancholy; and that the dismal description of the 'seventh age' is

immediately followed by the entrance on stage of the octogenarian Adam, who

has earlier represented himself and been represented as 'strong and lusty' and

who visibly subverts Jaques' story.87 The pervasiveness in English popular drama

and literature (for example in the work of Chaucer) of such dialogue between

conflict ing representations of old age, and its evident familiarity to medieval and

early modern audiences, suggests its deep roots in English culture and perhaps

in that of other countries.

Emerging out of the social and cultural history of old age at the beginning

of the millennium is a strong awareness of the plurality of representations and

experiences of old age over time and in any one time and place. It is more

difficult to assess whether certain values concerning old age are more dominant

at certain times and places than others, though we know enough to be wary of

over-arching schema of cultural decline.

The history of old age reminds us how vital social history is in providing

perspective, and a sense of ongoing issues and trajectories, on our own society.

Previous work on the subject has generated a number of important findings. But

it has not met, or at least has not fully met, some of the ongoing challenges

of social history to come: widening the geographical network and introducing

more formal comparison, and dealing explicitly with the relationship between

cultural and material factors. In this sense, old age history remains a new topic

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING 107

area, inviting further attention and more refined analysis even as we return to

issues of social structure in which age grading receives renewed attention.

Institute of Historical Research

Senate House

London WC1 E7H4

ENDNOTES

1. This is a revised version of an essay, addressed to social scientists, 'The History of

Aging in the West' published in Thas R. Coie, Robert Kastenbaum & Ruth E. Kay, eds.,

Handbook ofthe Humanities and Aging Second Edition (New York, 2000).

2. P. Stearns, Old Age in European Society (London, 1977); Keith Thomas "Age and

Authority in Early Modern England," Proceedings of the British Academy, 62, 1976, pp.

205-248; Peter Laslett, "Societal development and aging" in R. Binstock & E. Shanas,

eds., Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences (New York, 1976), pp. 87-116; D. Hackett

Fischer, Growing Old in America (New York, 1978).

3. R Bourdelais, Le nouvel age de la vieillesse: histoire du viellissement de la population

(Paris, 1993); D. Troyansky, Old Age in the Old Regime: Image and Experience in 18th and

19th century France (Ithaca, 1989); "Old age, retirement and the social contract in 18th

and 19th century France" in C. Conrad & H. J. Von Kondratowicz, Zur Kulturgeschichte

des Alterns (Berlin, 1993), pp. 77-95; "Balancing social and cultural approaches to the

history of old age and aging in Europe: a review and an example from post-revolutionary

France" in P. Johnson & P. Thane, Old Age from Antiquity to Post-Modernnity (London,

1998), pp. 96-109.

4. P.Borscheid, Geschichte des Alters 16-18. Jahrhundert (Munster, 1987); C. Conrad,

Vom Greis zum Rentner: Der Strukturwandeldes Alters in Deutschland zwischen 1830 und

1930 (Gottingen, 1994); H. J. Von Kondratowicz, "The medicalization of old age: con?

tinuity and change in Germany from the 18th to the 19th century" in M. Pelling and

R. M. Smith, eds., Life, Death and the Elderly: Historical Perspectives on Ageing (London,

1991), pp. 143-164.

5. Pat Thane, Old Age in EnglishHistory. Past Experiences, Present Issues (Oxford, 2000),

pp. 21-4.

6. G.Minois, History of Old Age: from antiquity to the renaissance. Trans. S. Hanbury-

Tenison (Oxford, 1989).

7. J.T. Rosenthal, Old Age in Late Medieval England (Philadelphia, 1996).

8. T. Premo, Winter Friends (Urbana, 1990); M.Stavenuiter, K. Bjisterfeld & S. Jansens,

Lange Levens, stilU getuigen. Oudere Vrowen in het verladen (Zutpen, 1996); L. Botelho &

R Thane, Women and Ageing in Britain since 1500 (London, 1999); Thane, Old Age; C.

Haber & B. Gratton, Old Age and the Search for Security: An American Social History

(Bloomington, 1994).

9. E. A. Wrigley and R. S. Schofield, The Population History of England 1541-1871. A

Reconstruction (Cambridge, 1989), p. 528.

10. E. A. Wrigley, R. S. Davies, J.E.Oeppen and R. S. Schofield, English Population History

from Family Reconstitution 1580-1837 (Cambridge, 1997), pp. 280-293.

11. Thane, Old Age, pp. 475-493.

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

108 journal of social history fall 2003

12. Patrice Bourdelais "The ageing of the population. Relevant question or obsolete

notion?" in Johnson & Thane, Antiquity to Post-Modernity 110-131.

13. Shulamith Shahar, Growing Old in the Middle Ages (London, 1997), pp. 33-5.

14. Ibid; Minois, History, pp. 79, 130, 180, 222, 224, 290, 292.

15. R. Schofield, "Did the Mothers Really Die? Three Centuries of Maternal Mortality

in 'The World we have Lost'," in L. Bonfield, et al., eds., The World We Have Gained

(Oxford, 1986), pp. 231-260.

16. Shahar, Growing Old, pp. 3 2-3.

17. Bourdelais, "The ageing," p. 110.

18. Edgar-Andre Montigny, Foisted upon the Government. State Responsibilities, Family

Obligations and the care o/the Dependent Aged in Late Nineteenth Century Ontario (Montreal,

1997), 33-41.

19. Haber & Gratton, Old Age and the Search for Security, p. 23.

20. W. Andrew Achenbaum, Old Age in the New Land. The American Experience since

1790 (Baltimore, 1976), 60-1.

21. Montigny, Foisted, p. 34.

22. Thane, Old Age, pp. 475-80.

23. Bourdelais, "The ageing," pp. 112-116. Pat Thane, "The debate on the declining

birthrate in Britain: the 'menace' of an ageing population, 1920s-1950s," Continuity and

Change, 5, (2), 1990, pp. 283-305.

24. Ibid.

25. Bourdelais, "The ageing," p. 111.

26. M. Raphael, Pensions and Public Servants: a study of the origins of the British system

(Paris, 1964).

27. Martin Kohli, M. Rein, A. Guillemard, H. van Gunsteren, eds., Time for Retirement.

Comparative Studies of Early Exitfrom the Labour Force (Cambridge, 1991).

28. Shahar, Growing Old, pp. 24ff.

29. M. Finley, "Old Age in Ancient Rome," Ageing and Society, 3,1983, pp. 391-408.

30. T. Parkin, "Ageing in antiquity: status and participation" in Johnson & Thane,

Antiquity to Postmodernity, p. 9.

31. Shahar, Growing Old, pp. 12-30; J.T. Rosenthal "Retirement and the Life-cycle in

Fifteenth Century England" in M.M. Sheehan, ed., Aging and the Aged in Medieval Europe

(Toronto, 1990), p. 179.

3 2. Shahar, Growing Old.

33. Lynn Botelho, "Old age and menopause in rural women in early modern Suffolk" in

Boteiho & Thane, Women and Ageing, pp. 43-65.

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING 109

34. Troyansky, "Old Age. Retirement and the social contract," p. 86.

35. Parkin, "Ageing in Antiquity".

36. J. A. Burrow, The Ages ofMan (Oxford, 1986); Mary Dove, The Perfect Age of Man's

Life (Cambridge, 1986); E. Sears, Ages ofMan: Medieval Interpretations of the Life-CycU

(Princeton, 1986).

37. P. Amoss & S. Harrell, Other Ways of Growing Old:Anthropohgical Perspectives (Stan?

ford, 1981).

38. Claire S. Schen, "Strategies of poor aged women and widows in sixteenth century

London" in Botelho & Thane, Women and Ageing, pp. 13-30; Montigny, Foisted; Elles

Bulder, The Social Economics of Old Age. Strategies to maintain income in later life in the

Netherlands, 1880-1940 (Tmbergen, 1993); Thane, Old Age, pp. 73-160, 273-286.

39. Montigny, Foisted, pp. 53-56.

40. Shahar, Growing old, pp. 13-14, 171-2 and passim; B. Harvey, Living and Dying in

England, 110-1540 (Oxford, 1993), pp. 179-209; R. M. Smith, "The Manorial Court and

the Elderly Tenant in Late Medieval England" in Margaret Pelling and R. M. Smith, eds.,

Life, Death and the Elderly. Historical Perspectives (London, 1991), pp. 39-61. P. J. Greven,

Four Generations (Ithaca, NY and London, 1970). C. Haber, "Historians' Approach to

Aging in America" in Cole, Kastenbaum, Ray, Handbook, pp. 28-30.

41. Troyansky, "Old Age, Retirement". Raphael, Pensions and Public Servants. G.Thuil-

lier, Les pensions de retraite des fonctionnaires au XlXeme siecU (Paris, 1994). Thane, Old

Age, pp. 236-256.

42. M. Pelling, "Old Age, Poverty and Disability in Norwich" in Pelling and Smith,

Life, Death and the Elderly, p. 82.

43. R. Jutte, Poverty and Deviance in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, 1994), pp. 86-90.

44. P Johnson, "The employment and retirement of older men in England and Wales,

1881-1981," Economic History Review, 47, 1994, 106-128; R. L. Ransom & R. Sutch,

"The labor of older Americans: retirement of men on and off the job, 1870-1937," Journal

of Economic History, 46, 1986, 1-30. B. Gratton, "The labor force participation of older

men," Journal of Social History, 20, 1987, 689-710; J. Moen, "The labor of older men,"

Journal of Economic History, 47 (3), 1987, 761-767. Thane, Old Age, pp. 273-286, 385-

406.

45. John Macnicol, The Politics of Retirement in Britain, 1878-1948 (Cambridge, 1998);

C. Phillipson, Capitalism and the Construction ofOld Age (London, 1982).

46. M. Kohli et al., eds., Time for Retirement.

47. Troyansky, "Old Age, Retirement"; Liam Kennedy, "Farm succession in modern

Ireland; elements ofa theory of inheritance," Economic History Review, 3,1991, pp. 478-

496; Montigny, Foisted.

48. D. Gaunt, "The property and kin relationships of retired farmers in northern and

central Europe" in R. Wall et al, eds., Family Forms in Historic Europe (Cambridge, 1983),

pp. 259.

49. Jutte, Poverty and Deviance, pp. 88-9.

50. ibid. p. 83 ff.

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

110 journal of social history fall 2003

51. David Thomson, "Old Age in the New World: New Zealand's Colonial Welfare

Experiment" in Johnson &t Thane, Antiquity to Postmodernity, pp. 146-179; Montigny,

Foisted; Haber, "Historians' Approach," pp. 28-29; Premo, Winter Friends, p. 36; C. Haber

and B. Gratton, Old Age and the Search for Security (Bloomington, 1993).

52. P. Laslett, "Necessary knowledge: age and aging in the societies of the past" in D.

Kertzner & P. Laslett, eds., Aging in the Past: Demography, Sockty and Old Age (Berkeley

& London, 1995); R Laslett & R.Wall, Household and Family in Past Time (Cambridge,

1972).

53. Laslett and Wall, Household and Family.

54. Jutte, Poverty and Deviance, p. 90.

55. L. Rosenmayr and E. Kockeis, "Proposition for a sociological theory of aging and the

family," International Social Science Journal, 3, 1963, pp. 418-9.

56. Jutte, Poverty and Deviance, p. 85.

57. Bourdelais, "The ageing," p. 116.

58. Thane, Old Age, pp. 407-435.

59. Montigny describes similar relationships in 19th century Canada. Montigny, Foisted,

pp. 33-49.

60. Bourdelais, "The ageing," p. 116.

61. Thane, Old Age, pp. 428-435.

62. Jutte, Poverty and Deviance.

63. Bourdelais, "The ageing," p. 116. Jutte, Poverty and Deviance. M. Pelling, "Old Age,

Poverty," pp. 85-90. Montigny, Foisted 40-48. Jeffrey Weeks, Brian Heaphy, Catherine

Donovan, "Families of choice: autonomy and mutuality in non-heterosexual relation?

ships" in Susan McRae, ed., ChangingBritain. Familiesand Households in the 1990s (Oxford,

1999), pp. 297-316.

64. Paul Slack, The English Poor Law, 1531-1782 (London, 1990).

65. Jutte, Poverty and Deviance, p. 54.

66. Slack, English Poor Law, pp. 39-45.

67. David Thomson, "Old Age in the New World: New Zealand's Colonial Welfare

Experiment" Ch. 8. in P. Johnson and Pat Thane, eds., Old Age from Antiquity to Post?

modernity (London, 1999); Brian Dickey, No Charity There. A Short History of Social

Welfare in Australia (Meibourne, 1980).

68. Montigny, Foisted, pp. 82-107.

69. P. Baldwin, The Politics of Social Solidarity. Class Bases ofthe European Welfare States,

1875-1975 (Cambridge, 1990).

70. World Bank, Averting the Old Age Crisis (Washington, 1994).

71. Minois, History, pp. 6-7.

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIAL HISTORIES OF OLD AGE AND AGING 111

72. D. H. Fischer, Growing Old.

73. Thomas R. Cole, The Journey ofLife. A cultural historyof aging in America (Cambridge,

1992).

74. Achenbaum, New Land; Haber, Beyond Sixty-Five (New York, 1983).

75. Fischer, Growing Old.

16. Cole, Journey.

77. Achenbaum, New Land.

78. Haber, Beyond Sixty-Five.

79. Haber, "Historians"; Thane, Old Age, pp. 1-16.

80. Parkin, "Ageing in antiquity".

81. Shahar, Growing Old; Rosenthal, Old Age.

82. Troyansky, Old Age in the Old Regime; "Socialand cultural approaches"; Bourdelais, Le

nouvel age; "The ageing".

83. Borscheid, Geschichte des Alters; Conrad, Vom Greis, zum Rentner; Von Kondratow-

icz, "medicalization."

84. Haber & Gratton, The search for security.

85. E. Clark, "The quest for security in medieval England" in M. M. Sheehan, ed., Aging

and the aged in medieval Europe (Toronto, 1990); R. M. Smith, "The manorial court and

the elderly tenant in late medieval England" in Pelling & Smith, Life, Death, pp. 39-61.

86. T. Sokoll, "Old age in poverty: the record of Essex pauper letters, 1780-1834" in

T. Hitchcock, et al, eds., Chronicling Poverty: The voices and strategies of the English poor,

1640-1840 (London, 1993), pp. 127-154.

87. William Shakespeare, As You Like lt Act 2 Scene 7.

This content downloaded from 128.118.88.48 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 02:40:31 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Adams - Experiencing World History (NYU, 2000)Document507 pagesAdams - Experiencing World History (NYU, 2000)Sammy Thomas Whyte100% (18)

- Eu Private International Law PDFDocument2 pagesEu Private International Law PDFRojo0% (1)

- Werner Conze Social HistoryDocument11 pagesWerner Conze Social HistoryFábio CostaNo ratings yet

- The Nature of HistoryDocument3 pagesThe Nature of HistoryRomelyn Angadol67% (3)

- Oxford University Press American Historical AssociationDocument25 pagesOxford University Press American Historical AssociationalexNo ratings yet

- Paul Thompson: The Voice of The Past OralDocument7 pagesPaul Thompson: The Voice of The Past OralDg HasmahNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapter1Document48 pages10 Chapter1zroro8803No ratings yet

- Social History and World HistoryDocument31 pagesSocial History and World HistoryU chI chengNo ratings yet

- History Notes PDFDocument73 pagesHistory Notes PDFNestor MassaweNo ratings yet

- Social History: Predicaments and Possibilities by Sumit SarkarDocument9 pagesSocial History: Predicaments and Possibilities by Sumit SarkarSpencer A. LeonardNo ratings yet

- BastaDocument4 pagesBastaMIÑOZO, REGINALDONo ratings yet

- Understanding HistoryDocument24 pagesUnderstanding HistorySamantha SimbayanNo ratings yet

- RIPHDocument14 pagesRIPHApril Pearl BrillantesNo ratings yet

- What Is History?: Why Do You Study History?Document4 pagesWhat Is History?: Why Do You Study History?Jesse AdamsNo ratings yet

- Common HIHMDocument74 pagesCommon HIHMYoni GechNo ratings yet

- Scotland's Future Culture: Recalibrating a Nation's IdentityFrom EverandScotland's Future Culture: Recalibrating a Nation's IdentityNo ratings yet

- Meaning and Relevance of HistoryDocument14 pagesMeaning and Relevance of HistoryDELEN Markian L.No ratings yet

- History AssignmentDocument7 pagesHistory AssignmentRoselle AbuelNo ratings yet

- WHATISHISTORYDocument3 pagesWHATISHISTORYjohn marlo andradeNo ratings yet

- History: Fernand BraudelDocument17 pagesHistory: Fernand BraudelGiorgos BabalisNo ratings yet

- Introduction of The EditorsDocument23 pagesIntroduction of The Editorscalibann100% (2)

- Reliving the Past: The Worlds of Social HistoryFrom EverandReliving the Past: The Worlds of Social HistoryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- Aging in The PastDocument43 pagesAging in The PastAlexis Flores CórdovaNo ratings yet

- RPH 1Document9 pagesRPH 1nikki abalosNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 5 Ge2Document40 pagesLesson 1 5 Ge2Ella Jordan LoterteNo ratings yet

- 1.1 History As A DisciplineDocument7 pages1.1 History As A DisciplineAlok shahNo ratings yet

- Handout of HistoryDocument21 pagesHandout of Historylamesawako65No ratings yet

- HistoryDocument7 pagesHistorySittie Najifa Amal AmpalNo ratings yet

- WHY WE STUDY HISTORY North South Lec.1Document22 pagesWHY WE STUDY HISTORY North South Lec.1Inzamul Islam IstiNo ratings yet

- Revised History Common Course Final Handout 1012Document51 pagesRevised History Common Course Final Handout 1012Hindeya AbadiNo ratings yet

- History For SEPDocument110 pagesHistory For SEPTofik AsmamawNo ratings yet

- Why Study HistoryDocument34 pagesWhy Study HistorynanadadaNo ratings yet

- History Assignment 1Document11 pagesHistory Assignment 1mthimkhulu zanemvulaNo ratings yet

- Past & Present Volume Issue 24 1963 (Doi 10.2307/649839) Keith Thomas - History and AnthropologyDocument23 pagesPast & Present Volume Issue 24 1963 (Doi 10.2307/649839) Keith Thomas - History and AnthropologyMartin CortesNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago Press The Journal of ReligionDocument18 pagesThe University of Chicago Press The Journal of ReligionShivatva BeniwalNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 History of Ethiopia and The HornDocument35 pagesUnit 1 History of Ethiopia and The Hornnatnael asmamawNo ratings yet

- GE2 Lesson Proper For Week 1 To 5Document35 pagesGE2 Lesson Proper For Week 1 To 5Alejandro Francisco Jr.No ratings yet

- GoodyDocument43 pagesGoodyGerman BurgosNo ratings yet

- Lesson Proper For Week 1: Historiography and Its ImportanceDocument22 pagesLesson Proper For Week 1: Historiography and Its ImportanceFrahncine CatanghalNo ratings yet

- History Common Course Final 1012Document57 pagesHistory Common Course Final 1012yonastakele745No ratings yet

- Timeline ReflectionDocument2 pagesTimeline Reflectionapi-643841412No ratings yet

- Youth and Cultural Practice - Mary Bucholtz - Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 31 (2002), Pp. 525-552Document29 pagesYouth and Cultural Practice - Mary Bucholtz - Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 31 (2002), Pp. 525-552Michael RogersNo ratings yet

- The Return of Universal HistoryDocument4 pagesThe Return of Universal HistoryJulie BlackettNo ratings yet

- Past & Present Volume Issue 27 1964 (Doi 10.2307/649764) - History, Sociology and Social AnthropologyDocument8 pagesPast & Present Volume Issue 27 1964 (Doi 10.2307/649764) - History, Sociology and Social AnthropologyMartin CortesNo ratings yet

- Why We Study History North South Lec.1Document22 pagesWhy We Study History North South Lec.1rahul.roy01No ratings yet

- Common Course FinalDocument62 pagesCommon Course FinalLetaNo ratings yet

- Joshua's GroupDocument19 pagesJoshua's GroupJoshua Nathaniel J. NegridoNo ratings yet

- Why Study History? (1998) : by Peter N. StearnsDocument4 pagesWhy Study History? (1998) : by Peter N. StearnsGiang DoNo ratings yet

- Scope of Sociology OptionalDocument16 pagesScope of Sociology OptionalMONIKA VERMANo ratings yet

- Trinashin U. Larosa Midterm Reflection PaperDocument10 pagesTrinashin U. Larosa Midterm Reflection PaperTrinashin Umapas LarosaNo ratings yet

- Brodie Waddell History From Below Today and TomorrowDocument7 pagesBrodie Waddell History From Below Today and TomorrowJORGE CONDE CALDERONNo ratings yet

- Firth - 1954 - Social Organization and Social ChangeDocument21 pagesFirth - 1954 - Social Organization and Social ChangeLidia BradymirNo ratings yet

- Ficha 02 - Folklore and Anthropology (William Bascom) PDFDocument9 pagesFicha 02 - Folklore and Anthropology (William Bascom) PDFobladi05No ratings yet

- Document GE 2 1Document5 pagesDocument GE 2 1Doronila Mark JosephNo ratings yet

- Hadout ComecourseDocument138 pagesHadout ComecoursenatyNo ratings yet

- Rowles - 1983 - Place and Personal Identity in Old Age ObservatioDocument15 pagesRowles - 1983 - Place and Personal Identity in Old Age ObservatioRicardoLanaNo ratings yet

- Why Study HistoryDocument5 pagesWhy Study HistoryJacob HolderNo ratings yet

- Family in History - History, An Introduction To Theory, Method and PracticeDocument5 pagesFamily in History - History, An Introduction To Theory, Method and PracticeM. Aryo BimoNo ratings yet

- Goody - The Consequences of Literacy - HDocument43 pagesGoody - The Consequences of Literacy - HzonenorNo ratings yet