Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Resrep 20200

Resrep 20200

Uploaded by

Như TrầnCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 2 - Liberty Karaoke - All Songs by ArtistDocument78 pages2 - Liberty Karaoke - All Songs by ArtistAlanFowlerNo ratings yet

- The Crisis of The Rohingya As A Muslim Minority in Myanmar and Bilateral Relations With BangladeshDocument18 pagesThe Crisis of The Rohingya As A Muslim Minority in Myanmar and Bilateral Relations With BangladeshNajmul Puda PappadamNo ratings yet

- Bodyweight Sports TrainingDocument56 pagesBodyweight Sports TrainingJoshp3c100% (18)

- LEIDER HistoryVictimhood 2018Document21 pagesLEIDER HistoryVictimhood 2018Suri Lebo PaulinusNo ratings yet

- Policy Paper FinalDocument9 pagesPolicy Paper FinalFuhad HasanNo ratings yet

- IR Alaytical PaperDocument6 pagesIR Alaytical PaperabhyuditmankeNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 52.66.103.4 On Tue, 09 Mar 2021 14:49:29 UTCDocument25 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 52.66.103.4 On Tue, 09 Mar 2021 14:49:29 UTCAstha KrishnaNo ratings yet

- New Political Space, Old Tensions: History, Identity and Violence in Rakhine State, MyanmarDocument27 pagesNew Political Space, Old Tensions: History, Identity and Violence in Rakhine State, MyanmarArafat jamilNo ratings yet

- CS8 Panteion II Rohingya The Invisible Minority of MyanmarDocument6 pagesCS8 Panteion II Rohingya The Invisible Minority of MyanmarDanai LamaNo ratings yet

- Arts and Social Sciences Journal: Systematic Ethnic Cleansing: The Case Study of RohingyaDocument7 pagesArts and Social Sciences Journal: Systematic Ethnic Cleansing: The Case Study of RohingyaArafat jamilNo ratings yet

- Lament of The Rohingya RevisedDocument6 pagesLament of The Rohingya Revisedapi-254814976No ratings yet

- Conflicting Coverage FinalwebDocument20 pagesConflicting Coverage FinalwebသိဒၶိNo ratings yet

- Myanmar Study Group Final ReportDocument64 pagesMyanmar Study Group Final ReportLại Thanh BìnhNo ratings yet

- The Disruptive Effects of Social Media in The Global South 2020Document21 pagesThe Disruptive Effects of Social Media in The Global South 2020jarufprNo ratings yet

- Welcom E: POL-104.5 PresentationDocument22 pagesWelcom E: POL-104.5 PresentationTasneva TasnevaNo ratings yet

- Conflicts and Regional Underdevelopment: A Review of Lake Chad Basin RegionDocument12 pagesConflicts and Regional Underdevelopment: A Review of Lake Chad Basin RegionOpen Access JournalNo ratings yet

- Pw140 Myanmars Armed Forces and The Rohingya CrisisDocument56 pagesPw140 Myanmars Armed Forces and The Rohingya CrisisInformer100% (1)

- Nexus Between Displacement and RadicalizationDocument33 pagesNexus Between Displacement and RadicalizationPrime SaarenasNo ratings yet

- Producing The News, Reporting On Myanmar's Rohingya CrisisDocument22 pagesProducing The News, Reporting On Myanmar's Rohingya CrisisVeraRenteroNo ratings yet

- Stabilizing Northeast Nigeria After Boko Haram: Saskia BrechenmacherDocument46 pagesStabilizing Northeast Nigeria After Boko Haram: Saskia BrechenmacherdanallexNo ratings yet

- ORF IssueBrief 247 Rohingya FinalForUploadDocument17 pagesORF IssueBrief 247 Rohingya FinalForUploadmohitpaliwalNo ratings yet

- OCHA Myanmar - Humanitarian Update No. 28 - FinalDocument13 pagesOCHA Myanmar - Humanitarian Update No. 28 - FinalHan Htoo AungNo ratings yet

- The Rohingyas of MyanmarDocument8 pagesThe Rohingyas of MyanmarMohd Mahathir SuguaNo ratings yet

- Myanmar 'S Worsening Rohingya Crisis: A Call For Responsibility To Protect and ASEAN 'S ResponseDocument14 pagesMyanmar 'S Worsening Rohingya Crisis: A Call For Responsibility To Protect and ASEAN 'S ResponseCiy EfijNo ratings yet

- ROHINGYADocument4 pagesROHINGYACahyaNo ratings yet

- Sayeda Akther and Ushan Ara BadalDocument3 pagesSayeda Akther and Ushan Ara BadalLogical MuhammadNo ratings yet

- SOCHUM Mitigating The Refugee Crisis Caused by The Rohingya Genocide in MyanmarDocument4 pagesSOCHUM Mitigating The Refugee Crisis Caused by The Rohingya Genocide in MyanmarRavaka RAJOBSONNo ratings yet

- International RelationsDocument8 pagesInternational Relationspoovizhikalyani.m2603No ratings yet

- Activity 1 F Journal Article ReviewDocument2 pagesActivity 1 F Journal Article ReviewAthy CloyanNo ratings yet

- Rohingya in Burma - October 2012Document4 pagesRohingya in Burma - October 2012Andre CarlsonNo ratings yet

- The Religious Landscape in Myanmarz Rakhine State - US Institute of Peace - August 2019Document44 pagesThe Religious Landscape in Myanmarz Rakhine State - US Institute of Peace - August 2019Shahidul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Between Isolation and Inter Nationalization - The State of Burma-SIIA - Papers - 4Document177 pagesBetween Isolation and Inter Nationalization - The State of Burma-SIIA - Papers - 4Phone Hlaing100% (4)

- The Rohingya Crisis A Test For Bangladesh-Myanmar Relations: Has FacedDocument6 pagesThe Rohingya Crisis A Test For Bangladesh-Myanmar Relations: Has FacedMd Kawsarul IslamNo ratings yet

- ROHINGYADocument4 pagesROHINGYACahyaNo ratings yet

- Nigar Rahman2Document12 pagesNigar Rahman2Habibur RahmanNo ratings yet

- HDP NexusDocument7 pagesHDP NexusTabi EloraNo ratings yet

- Displacement of The Rohingyas in Southeast AsiaDocument20 pagesDisplacement of The Rohingyas in Southeast AsiatrinitaNo ratings yet

- 2013 07 03 Conflict in - Rakhine State in Myanmar - Rohingya Muslims Conundrum en RedDocument14 pages2013 07 03 Conflict in - Rakhine State in Myanmar - Rohingya Muslims Conundrum en Redakar phyoeNo ratings yet

- 2019 04 Abuse or Exile en RedDocument24 pages2019 04 Abuse or Exile en Redakar PhyoeNo ratings yet

- To Intervene or Not To Intervene: Ethics of Humanitarian Intervention in MyanmarDocument17 pagesTo Intervene or Not To Intervene: Ethics of Humanitarian Intervention in MyanmarKidsNo ratings yet

- Robayt Khondoker and Tanvir HabibDocument4 pagesRobayt Khondoker and Tanvir HabibAzizul Hakim B 540No ratings yet

- Ethnic Cleansing: A Case Study of Rohingya Conflict: Saima Bhutto 1517127Document17 pagesEthnic Cleansing: A Case Study of Rohingya Conflict: Saima Bhutto 1517127Saima BhuttoNo ratings yet

- Advance Edited Version: Situation of Human Rights of Rohingya Muslims and Other Minorities in MyanmarDocument19 pagesAdvance Edited Version: Situation of Human Rights of Rohingya Muslims and Other Minorities in MyanmarKushar Dev ChhibberNo ratings yet

- Impact of The Rohingya Refugee Crisis On The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)Document12 pagesImpact of The Rohingya Refugee Crisis On The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)akar phyoeNo ratings yet

- Global ConflictsDocument3 pagesGlobal ConflictsWaqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- International Crisis & Instant Coffee: The Bangladesh-Myanmar Border RegionDocument27 pagesInternational Crisis & Instant Coffee: The Bangladesh-Myanmar Border RegionKaung Myat HeinNo ratings yet

- No Where To Run EngDocument28 pagesNo Where To Run EngKim ErichNo ratings yet

- Elements of Pathos and Media Framing As Scientific DiscourseDocument11 pagesElements of Pathos and Media Framing As Scientific DiscourseNAEEM AFZALNo ratings yet

- Rakhine Rohingya Conflict AnalysisDocument22 pagesRakhine Rohingya Conflict AnalysisNyein Chanyamyay100% (1)

- Q 9 (B)Document3 pagesQ 9 (B)Himal SigdelNo ratings yet

- Security Council: United NationsDocument17 pagesSecurity Council: United NationsIlove PoornNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Humanitarian Aid On Post Conflict Development in Borno StateDocument16 pagesThe Impact of Humanitarian Aid On Post Conflict Development in Borno Stateyeabsera danielNo ratings yet

- Study Guide - Rohingya PeopleDocument17 pagesStudy Guide - Rohingya PeopleArishthaNo ratings yet

- A Research Paper On Do Refugees Create IDocument8 pagesA Research Paper On Do Refugees Create INipu TabasumNo ratings yet

- Rohingya Final Without AnalysisDocument40 pagesRohingya Final Without AnalysisGolam Samdanee TaneemNo ratings yet

- Conflict Analysis of Muslim Mindanao PDFDocument31 pagesConflict Analysis of Muslim Mindanao PDFClint RamosNo ratings yet

- Maung Z Arni Alice Cowley The SDocument73 pagesMaung Z Arni Alice Cowley The SDaksh MiddhaNo ratings yet

- Hybrid WarfareDocument11 pagesHybrid WarfareZarNo ratings yet

- ISFRPOL - Research PresentationDocument12 pagesISFRPOL - Research PresentationGAB GABRIELNo ratings yet

- Citizenship, Nationalism and Refugeehood of Rohingyas in Southern AsiaFrom EverandCitizenship, Nationalism and Refugeehood of Rohingyas in Southern AsiaNasreen ChowdhoryNo ratings yet

- Along the Integral Margin: Uneven Development in a Myanmar Squatter SettlementFrom EverandAlong the Integral Margin: Uneven Development in a Myanmar Squatter SettlementNo ratings yet

- Ngô Thị Mỹ Hoa - writingDocument2 pagesNgô Thị Mỹ Hoa - writingNhư TrầnNo ratings yet

- Ngô Thị Mỹ Hoa - 1757020017- ReadingDocument3 pagesNgô Thị Mỹ Hoa - 1757020017- ReadingNhư TrầnNo ratings yet

- Essay SleepDocument2 pagesEssay SleepNhư TrầnNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ THI HSG ANH 6 02Document6 pagesĐỀ THI HSG ANH 6 02Như TrầnNo ratings yet

- Verbal Communic-WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesVerbal Communic-WPS Officechandy RendajeNo ratings yet

- Del Rosario-Igtiben V RepublicDocument1 pageDel Rosario-Igtiben V RepublicGel TolentinoNo ratings yet

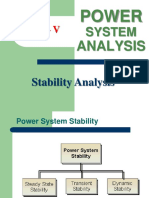

- Unit - V: PowerDocument32 pagesUnit - V: PowerVaira PerumalNo ratings yet

- Controller Job DescriptionDocument3 pagesController Job DescriptionEkka PrasetiaNo ratings yet

- FCE Exam 3 ListeningDocument6 pagesFCE Exam 3 ListeningSaul MendozaNo ratings yet

- OSI Layer & TCP Protocols - PostQuiz - Attempt ReviewDocument4 pagesOSI Layer & TCP Protocols - PostQuiz - Attempt Reviewvinay Murakambattu100% (1)

- GraduatingresumeDocument3 pagesGraduatingresumeapi-277434369No ratings yet

- Microbes in Ferment@3Document13 pagesMicrobes in Ferment@3T Vinit ReddyNo ratings yet

- Jara, John Leoj I. Prof - Dioshua Sapla Plate 1: Ground Floor Plan Second Floor PlanDocument1 pageJara, John Leoj I. Prof - Dioshua Sapla Plate 1: Ground Floor Plan Second Floor PlanWynne TillasNo ratings yet

- IBM UML 2.0 Advanced NotationsDocument21 pagesIBM UML 2.0 Advanced NotationsKeerthana SubramanianNo ratings yet

- 245-Article Text-493-1-10-20220221Document8 pages245-Article Text-493-1-10-20220221Mr DNo ratings yet

- Hill, Therapist Techniques, Client Involvement, and The Therapeutic Relationship, (Hill, 2005)Document12 pagesHill, Therapist Techniques, Client Involvement, and The Therapeutic Relationship, (Hill, 2005)Osman CastroNo ratings yet

- Time QuotesDocument6 pagesTime Quoteschristophdollis100% (6)

- 126 1043 8 PB 1Document12 pages126 1043 8 PB 1MussyNo ratings yet

- FBS IntroductionDocument50 pagesFBS IntroductionPerly Algabre PantojanNo ratings yet

- History of Children LiteratureDocument3 pagesHistory of Children Literatureemil_masagca1467No ratings yet

- Vijaya Bank ChanchalDocument2 pagesVijaya Bank ChanchalShubham sharmaNo ratings yet

- Dip One GoroDocument8 pagesDip One GoroanakayamNo ratings yet

- Vitamin B2Document10 pagesVitamin B2Rida IshaqNo ratings yet

- Keerthi Question BankDocument65 pagesKeerthi Question BankKeerthanaNo ratings yet

- Flue & Chimney BrochureDocument15 pagesFlue & Chimney BrochureAirtherm Engineering LtdNo ratings yet

- R. Kelly Fan Letter To CourtDocument4 pagesR. Kelly Fan Letter To Court5sos DiscoNo ratings yet

- A La Nanita NanaDocument1 pageA La Nanita Nanabill desaillyNo ratings yet

- Reading in Philippines HistoryDocument7 pagesReading in Philippines Historyrafaelalmazar416No ratings yet

- Impact of Work Life Balance On Women Employees (1) PsDocument13 pagesImpact of Work Life Balance On Women Employees (1) PsPunnya SelvarajNo ratings yet

- Fortinet OT - PublishedDocument59 pagesFortinet OT - PublishedCryptonesia IndonesiaNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Spoilage, Defective Units and Scrap: 1. TerminologyDocument13 pagesAccounting For Spoilage, Defective Units and Scrap: 1. TerminologyWegene Benti UmaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Individual AssignmentDocument13 pagesAssignment 3 Individual AssignmentThư Phan MinhNo ratings yet

Resrep 20200

Resrep 20200

Uploaded by

Như TrầnOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Resrep 20200

Resrep 20200

Uploaded by

Như TrầnCopyright:

Available Formats

US Institute of Peace

Reframing the Crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine State

Author(s): Gabrielle Aron

US Institute of Peace (2018)

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep20200

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

US Institute of Peace is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to this

content.

This content downloaded from

14.161.38.166 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 07:32:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

U N I T E D S TAT E S I N S T I T U T E O F P E A C E

PEACEBRIEF242

United States Institute of Peace • www.usip.org • Tel. 202.457.1700 • @usip January 2018

Gabrielle Aron Reframing the Crisis in

Email: gabriellearon.consulting

@gmail.com Myanmar’s Rakhine State

Summary

• Attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army on Myanmar military and police posts and

an intensive security-sector response in northern Rakhine State have resulted in widespread

displacement, allegations of severe human rights abuses, and the evolution of a new humani-

tarian crisis.

• The current crisis and the broader Rakhine conflict are interpreted and represented distinctly

by different ethnic and political groups, both within Myanmar and on the international stage.

This narrative divergence has had tangible negative impacts on prospects for peace.

• The space for constructive international engagement with Myanmar authorities has greatly

diminished in recent months, at a time when the need for inroads into collaborative conflict

prevention is critical.

• The diverse positions and grievances of communities affected by the conflict have not been

“

adequately represented in national and international media and strategy; correcting this is a

The conflict in Rakhine

prerequisite to positive change.

State since 2012 is informed

by historical tensions and

contemporary disputes

over political power-sharing

Introduction

between the ethnic Rakhine

The Rakhine State conflict has shifted fundamentally since the emergence of a new armed actor,

and Rohingya. ” the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA). The group staged two rounds of attacks on military

and police posts in northern Rakhine, first in October 2016 and again in August 2017. These attacks

and the ensuing military clearance operations have resulted in tragic loss of life, destruction of

property, and internal displacement of civilians, among other consequences.

The recent violence is a culmination of decades of structural discrimination by the central

government and military. These actors have dispossessed the Rohingya and ethnic Rakhine

minority groups in distinct ways and increased competition and grievances. Following outbreaks

of intercommunal violence in 2012, political and human rights have been further circumscribed.

How the crisis is understood varies, however, sometimes starkly. Misinformation has been

circulated by all sides, and binary views quickly constructed despite the considerable complexity

of the situation. The urgency of recent developments has largely eclipsed consideration of the

© USIP 2018 • All rights reserved.

This content downloaded from

14.161.38.166 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 07:32:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Reframing the Crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine State

Page 2 • PB 242 • January 2018

broader conflict, conditioning both domestic and international responses that may be more reac-

tive to popular pressures than conducive to durable solutions. Narratives have therefore played a

meaningful role in shaping conflict dynamics.

A War of Perception

Two often conflicting narratives have emerged since October 2016. One, to which the civilian

government, military, and many non-Muslim constituents across Myanmar subscribe, frames

ARSA’s attacks as a critical threat to national security and the cultural-religious status quo. The

government has branded ARSA a terrorist organization, fanning fears that the group has an

Islamist or jihadist agenda.1 Buddhist nationalism has also been increasingly invoked since 2010 by

actors seeking to reap influence from a disordered democratic transition, leading to a rise

in Islamophobia. The population sees the government and military as defenders of public interest

and security; allegations of abuses leveled against these institutions by Rohingya refugees and

international human rights groups are thus met with skepticism. Much of Myanmar’s population

view international condemnations as not only unfair but also adversarial to the national interest—

generating little institutional incentive for military operations centered around civilian protection.

The second narrative, to which many in the international community as well as local and

diaspora Rohingya subscribe, has focused on Rohingya suffering. The military is framed as a

purveyor of atrocity, Aung San Suu Kyi’s civilian government as pandering and hypocritical, and

the ethnic Rakhine, when discussed, as uniformly racist. Government arguments about domestic

security are seen by international actors as manipulative and as evidence that domestic actors are

not genuinely committed to mitigating conflict.

A key barrier to conflict mitigation has been the international community’s “naming and

shaming” approach in responding to recent events. Reputation is central in Myanmar culture, and

officials are reluctant to act in any way appearing to validate public criticism, rendering such efforts

often counterproductive. International influence with Myanmar’s decision makers has consequen-

tially diminished. Furthermore, Myanmar is undergoing a tenuous democratic transition, in which

relationships between the civilian and military branches of government are still being negotiated.

The civilian government has thus found itself having to choose between prioritizing international

relations or domestic.

At the same time, pressure has mounted on overseas policymakers, particularly from Western

and Muslim-majority countries, to speak out in defense of the Rohingya. These individuals face a

critical dilemma: to take a public moral stand condemning atrocity, and in doing so risk sealing off

critical political inroads to preventing further abuses, or to maintain measured public messaging

and a productive relationship with Myanmar authorities, risking accusations of inaction and com-

plicity at home. In this zero-sum game between principles and practicality, principles have largely

won out, albeit at times to the detriment of the goal to prevent further atrocity. Anti-international

sentiment derived from heavy international criticism has coalesced within Myanmar, increasing

blanket support for the civilian government and military and diminishing the likelihood that claims

of abuse will be taken seriously—or acted upon.

Another key driver of the controversy is ARSA itself. ARSA’s strategic communications have

sought to portray it as a group of freedom fighters; however, brutal methods to silence dissent

from moderate Rohingya and to forcibly increase the size of ARSA fighting forces have been

reported.2 Allegations have also circulated that the group has targeted civilians from other

ethnic groups. Although violence perpetrated by ARSA is the focus of national discourse within

the country, it has featured relatively little in the international space. To date no comprehensive

© USIP 2018 • All rights reserved.

This content downloaded from

14.161.38.166 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 07:32:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Reframing the Crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine State

Page 3 • PB 242 • January 2018

documentation of abuses by ARSA has been published by an international human rights agency,

further discrediting the international community in the eyes of Myanmar’s decision makers.

Furthermore, the crisis has now increased the interest of transnational extremist groups, which

may seek to leverage the crisis to achieve broader regional and institutional objectives. Several

groups have already expressed support for ARSA or have sought to recruit transnational fighters.3

ARSA’s leadership is thought to be wary of support from outside groups, but should they fail to build

consensus on next steps it is highly possible that the group would factionalize. It is thus imperative

that ARSA is discussed and addressed by all actors in line with the threat to regional stability that

it represents. The Myanmar government-military narrative that the crisis is a domestic affair is now

beyond tenability, and a coordinated political and humanitarian response is imperative. A deepened

international-Myanmar divide will continue to impede necessary course corrections.

A Web of Grievance

The conflict in Rakhine State since 2012 is informed by long-standing historical tensions and

contemporary disputes over political power-sharing between the ethnic Rakhine and Rohingya.

Effective coverage of and responses to the crisis must reflect the broader conflict context.

The Ethnic Rakhine

Descendants of the Arakan Empire, the ethnic Rakhine today remain one of Myanmar’s most

cohesive ethnonational minority groups. Rakhine State is among the poorest and most politically

marginalized ethnic states in Myanmar, having been historically repressed by the central Bamar

government. There is a widespread ethnic Rakhine fear that, if unable to assert greater control

over the political affairs of the state, Rakhine society will disintegrate in the culmination of a long,

regressive path since the fall of the Arakan Empire.

In this context, changing demographics have given rise to substantial alarm among the ethnic

Rakhine and are at the root of the controversy around the term Rohingya. If recognized as one of

Myanmar’s official ethnic groups, the Rohingya could gain political and representational rights

currently denied them, and could then constitute a strong minority bloc with meaningful influence

over local policies, resources, and culture. The ethnic Rakhine perspective is that the Rohingya are

simply the latest in a long line of “outsiders” threatening dominion over Rakhine State.

Since 2012, the ethnic Rakhine have also developed substantial grievances toward the interna-

tional community, both because humanitarian relief has largely targeted the internally displaced,

the majority of whom are Muslim, and because ethnic Rakhine grievances have been under-

represented in international coverage of the conflict. In the absence of external engagement and

trust comes defensiveness and insularity. Since 2012, nationalism has coalesced, and hard-liners

have had an opening to spread fear and manipulate public sentiment. This dynamic has severely

hindered inclusive solutions to the crisis and has attenuated humanitarian space.

The Rohingya

The Rohingya—a largely stateless people—have long faced systemic discrimination and rights

abuses in Rakhine State, a situation worsened in the aftermath of the 2012 conflict. State-

enforced segregation in many parts of central Rakhine has continually increased intercommunal

fear and a tendency toward dehumanization. Heavy militarization of northern Rakhine has

resulted in consistent violation of rights and rule of law, the consequences of which have been

borne primarily by the Rohingya.

© USIP 2018 • All rights reserved.

This content downloaded from

14.161.38.166 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 07:32:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Reframing the Crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine State

Page 4 • PB 242 • January 2018

When the National League for Democracy came to power after the 2015 elections, hope resur-

faced among the Rohingya. Because Daw Aung San Suu Kyi too was a victim of political persecution,

many Rohingya expected her to address such abuses. That no gains were realized quickly consti-

tuted a significant disappointment, and may have contributed to conditions in northern Rakhine

that were ripe for radicalization. Government efforts to conduct citizenship verification exercises

for stateless Rohingya did not align with community concerns or recognize the diversity of local

perspectives. Given Myanmar’s largely ethnicity-based citizenship system, there is a debate among

Rohingya in Rakhine State on whether to prioritize advocacy for recognition as ethnic Rohingya or

to prioritize gaining citizenship at any cost, even if it means accepting an alternate ethnic categoriza-

tion. While all Rohingya hope for improved human rights, there is no consensus on the most feasible

path to achieve them. This debate is rarely acknowledged in discourse, rendering “one size fits all”

policy and advocacy design ineffectual—both in Myanmar and overseas.

Nonetheless, the predominant attitude of Rohingya in Rakhine State has traditionally been that

violent methods are futile. It is notable that members of the Rohingya diaspora have played a lead-

ing role in ARSA’s founding, management, and public relations. Populations that are both vulnerable

and desperate are easily manipulated, however; in northern Rakhine, persuasion and intimidation

appear to have played a role in boosting cooperation with ARSA among a population with little

history of radicalization. There remains intense frustration among many Rohingya that the actions of

a few have resulted in such irrevocable damage.4

Rohingya voices in Rakhine State often go unheard, both domestically and overseas. More

accessible Rohingya from Yangon and from the overseas diaspora have largely been accepted as the

mouthpieces of the Rohingya community writ large. However, these actors are often disconnected

from the everyday experience and perspectives of Rohingya in Rakhine State, often aligning advo-

cacy with distinct—or at best, only partially representative—political agendas. This gap between

decision makers and the Rohingya directly affected by the conflict has been a further obstacle to

formulating feasible solutions.

Recommendations

Building mutual understanding on the causes and potential solutions to the crisis among actors

with distinct but legitimate priorities and grievances is now critical. With this in mind, international

and domestic actors must assess and mitigate the negative relational impacts of advocacy and other

interventions in order to avoid unintended and divisive consequences that miss opportunities for

positive change.

• International and domestic media outlets should refrain from disseminating unverified

information, including on social media, and should avoid making generalizations (whether

implicit or explicit) about any ethnoreligious group. This approach would be facilitated by

unfettered media access to northern Rakhine State.

• International diplomats, media outlets, and human rights agencies should consistently high-

light the plight of all ethnic communities in Rakhine State affected by the crisis.

• Overseas governments should seek to rebuild constructive relations with the Myanmar

government and security sector to promote collaboration and course redirection.

• The government, military, and all civilians should pursue nonviolent approaches to stabilization

and peacebuilding moving forward. International agencies operating in Rakhine State should

urgently initiate public information campaigns, to raise awareness of existing international

assistance that supports ethnic Rakhine and other minority communities. The government of

© USIP 2018 • All rights reserved.

This content downloaded from

14.161.38.166 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 07:32:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Reframing the Crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine State

Page 5 • PB 242 • January 2018

About This Brief Myanmar should support and participate in this campaign and in agencies’ efforts to obtain

humanitarian access.

This Peace Brief highlights the

• The government of Myanmar should advocate tolerance to the Myanmar public consistently,

ways in which national and inter-

national narratives surrounding highlighting the role of inclusion and diversity as key pillars of democracy.

the recent Rakhine State crisis in • The government of Myanmar should work with Buddhist and Muslim religious leaders across

Myanmar have shaped political Rakhine State to prepare and publicize signed commitments to nonviolence.

dynamics and how the situation

has evolved. Derived from

extensive consultations in Rakhine Notes

State, the Brief is supported by

1. To date, evidence to suggest that ARSA pursues a jihadist or Islamist agenda is scant. Such a

the Asia Center at the United

States Institute of Peace. Gabrielle dynamic could develop in the future, however, should the group splinter into factions or ally

Aron is an independent analyst itself with transnational terror organizations.

and conflict adviser who special- 2. “Myanmar: A New Muslim Insurgency in Rakhine State,” Asia Report no. 283 (Brussels: Interna-

izes in Rakhine State.

tional Crisis Group, December 2016).

3. Such as al-Qaeda, FPI (Islamic Defenders Front) in Indonesia, and mujahideen groups in Malaysia,

among others.

4. Interviews with Rohingya community members in northern and central Rakhine State, 2014–17.

2301 Constitution Ave.

2301 Constitution

2301 ConstitutionAve.

Ave., NW

Washington,

Washington, DC

DC 20037

20037

Washington,

202.457.1700 D.C. 20037

202.457.1700

eISBN: 978-1-60127-698-8

USIP provides the analysis, training, and

tools that prevent and end conflicts,

promotes stability, and professionalizes

the field of peacebuilding.

The views expressed in this report do

not necessarily reflect the views of the

United States Institute of Peace, which

does not advocate specific policy

positions.

For media inquiries, contact the office

of Public Affairs and Communications,

202.429.4725.

© USIP 2018 • All rights reserved.

This content downloaded from

14.161.38.166 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 07:32:48 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- 2 - Liberty Karaoke - All Songs by ArtistDocument78 pages2 - Liberty Karaoke - All Songs by ArtistAlanFowlerNo ratings yet

- The Crisis of The Rohingya As A Muslim Minority in Myanmar and Bilateral Relations With BangladeshDocument18 pagesThe Crisis of The Rohingya As A Muslim Minority in Myanmar and Bilateral Relations With BangladeshNajmul Puda PappadamNo ratings yet

- Bodyweight Sports TrainingDocument56 pagesBodyweight Sports TrainingJoshp3c100% (18)

- LEIDER HistoryVictimhood 2018Document21 pagesLEIDER HistoryVictimhood 2018Suri Lebo PaulinusNo ratings yet

- Policy Paper FinalDocument9 pagesPolicy Paper FinalFuhad HasanNo ratings yet

- IR Alaytical PaperDocument6 pagesIR Alaytical PaperabhyuditmankeNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 52.66.103.4 On Tue, 09 Mar 2021 14:49:29 UTCDocument25 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 52.66.103.4 On Tue, 09 Mar 2021 14:49:29 UTCAstha KrishnaNo ratings yet

- New Political Space, Old Tensions: History, Identity and Violence in Rakhine State, MyanmarDocument27 pagesNew Political Space, Old Tensions: History, Identity and Violence in Rakhine State, MyanmarArafat jamilNo ratings yet

- CS8 Panteion II Rohingya The Invisible Minority of MyanmarDocument6 pagesCS8 Panteion II Rohingya The Invisible Minority of MyanmarDanai LamaNo ratings yet

- Arts and Social Sciences Journal: Systematic Ethnic Cleansing: The Case Study of RohingyaDocument7 pagesArts and Social Sciences Journal: Systematic Ethnic Cleansing: The Case Study of RohingyaArafat jamilNo ratings yet

- Lament of The Rohingya RevisedDocument6 pagesLament of The Rohingya Revisedapi-254814976No ratings yet

- Conflicting Coverage FinalwebDocument20 pagesConflicting Coverage FinalwebသိဒၶိNo ratings yet

- Myanmar Study Group Final ReportDocument64 pagesMyanmar Study Group Final ReportLại Thanh BìnhNo ratings yet

- The Disruptive Effects of Social Media in The Global South 2020Document21 pagesThe Disruptive Effects of Social Media in The Global South 2020jarufprNo ratings yet

- Welcom E: POL-104.5 PresentationDocument22 pagesWelcom E: POL-104.5 PresentationTasneva TasnevaNo ratings yet

- Conflicts and Regional Underdevelopment: A Review of Lake Chad Basin RegionDocument12 pagesConflicts and Regional Underdevelopment: A Review of Lake Chad Basin RegionOpen Access JournalNo ratings yet

- Pw140 Myanmars Armed Forces and The Rohingya CrisisDocument56 pagesPw140 Myanmars Armed Forces and The Rohingya CrisisInformer100% (1)

- Nexus Between Displacement and RadicalizationDocument33 pagesNexus Between Displacement and RadicalizationPrime SaarenasNo ratings yet

- Producing The News, Reporting On Myanmar's Rohingya CrisisDocument22 pagesProducing The News, Reporting On Myanmar's Rohingya CrisisVeraRenteroNo ratings yet

- Stabilizing Northeast Nigeria After Boko Haram: Saskia BrechenmacherDocument46 pagesStabilizing Northeast Nigeria After Boko Haram: Saskia BrechenmacherdanallexNo ratings yet

- ORF IssueBrief 247 Rohingya FinalForUploadDocument17 pagesORF IssueBrief 247 Rohingya FinalForUploadmohitpaliwalNo ratings yet

- OCHA Myanmar - Humanitarian Update No. 28 - FinalDocument13 pagesOCHA Myanmar - Humanitarian Update No. 28 - FinalHan Htoo AungNo ratings yet

- The Rohingyas of MyanmarDocument8 pagesThe Rohingyas of MyanmarMohd Mahathir SuguaNo ratings yet

- Myanmar 'S Worsening Rohingya Crisis: A Call For Responsibility To Protect and ASEAN 'S ResponseDocument14 pagesMyanmar 'S Worsening Rohingya Crisis: A Call For Responsibility To Protect and ASEAN 'S ResponseCiy EfijNo ratings yet

- ROHINGYADocument4 pagesROHINGYACahyaNo ratings yet

- Sayeda Akther and Ushan Ara BadalDocument3 pagesSayeda Akther and Ushan Ara BadalLogical MuhammadNo ratings yet

- SOCHUM Mitigating The Refugee Crisis Caused by The Rohingya Genocide in MyanmarDocument4 pagesSOCHUM Mitigating The Refugee Crisis Caused by The Rohingya Genocide in MyanmarRavaka RAJOBSONNo ratings yet

- International RelationsDocument8 pagesInternational Relationspoovizhikalyani.m2603No ratings yet

- Activity 1 F Journal Article ReviewDocument2 pagesActivity 1 F Journal Article ReviewAthy CloyanNo ratings yet

- Rohingya in Burma - October 2012Document4 pagesRohingya in Burma - October 2012Andre CarlsonNo ratings yet

- The Religious Landscape in Myanmarz Rakhine State - US Institute of Peace - August 2019Document44 pagesThe Religious Landscape in Myanmarz Rakhine State - US Institute of Peace - August 2019Shahidul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Between Isolation and Inter Nationalization - The State of Burma-SIIA - Papers - 4Document177 pagesBetween Isolation and Inter Nationalization - The State of Burma-SIIA - Papers - 4Phone Hlaing100% (4)

- The Rohingya Crisis A Test For Bangladesh-Myanmar Relations: Has FacedDocument6 pagesThe Rohingya Crisis A Test For Bangladesh-Myanmar Relations: Has FacedMd Kawsarul IslamNo ratings yet

- ROHINGYADocument4 pagesROHINGYACahyaNo ratings yet

- Nigar Rahman2Document12 pagesNigar Rahman2Habibur RahmanNo ratings yet

- HDP NexusDocument7 pagesHDP NexusTabi EloraNo ratings yet

- Displacement of The Rohingyas in Southeast AsiaDocument20 pagesDisplacement of The Rohingyas in Southeast AsiatrinitaNo ratings yet

- 2013 07 03 Conflict in - Rakhine State in Myanmar - Rohingya Muslims Conundrum en RedDocument14 pages2013 07 03 Conflict in - Rakhine State in Myanmar - Rohingya Muslims Conundrum en Redakar phyoeNo ratings yet

- 2019 04 Abuse or Exile en RedDocument24 pages2019 04 Abuse or Exile en Redakar PhyoeNo ratings yet

- To Intervene or Not To Intervene: Ethics of Humanitarian Intervention in MyanmarDocument17 pagesTo Intervene or Not To Intervene: Ethics of Humanitarian Intervention in MyanmarKidsNo ratings yet

- Robayt Khondoker and Tanvir HabibDocument4 pagesRobayt Khondoker and Tanvir HabibAzizul Hakim B 540No ratings yet

- Ethnic Cleansing: A Case Study of Rohingya Conflict: Saima Bhutto 1517127Document17 pagesEthnic Cleansing: A Case Study of Rohingya Conflict: Saima Bhutto 1517127Saima BhuttoNo ratings yet

- Advance Edited Version: Situation of Human Rights of Rohingya Muslims and Other Minorities in MyanmarDocument19 pagesAdvance Edited Version: Situation of Human Rights of Rohingya Muslims and Other Minorities in MyanmarKushar Dev ChhibberNo ratings yet

- Impact of The Rohingya Refugee Crisis On The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)Document12 pagesImpact of The Rohingya Refugee Crisis On The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)akar phyoeNo ratings yet

- Global ConflictsDocument3 pagesGlobal ConflictsWaqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- International Crisis & Instant Coffee: The Bangladesh-Myanmar Border RegionDocument27 pagesInternational Crisis & Instant Coffee: The Bangladesh-Myanmar Border RegionKaung Myat HeinNo ratings yet

- No Where To Run EngDocument28 pagesNo Where To Run EngKim ErichNo ratings yet

- Elements of Pathos and Media Framing As Scientific DiscourseDocument11 pagesElements of Pathos and Media Framing As Scientific DiscourseNAEEM AFZALNo ratings yet

- Rakhine Rohingya Conflict AnalysisDocument22 pagesRakhine Rohingya Conflict AnalysisNyein Chanyamyay100% (1)

- Q 9 (B)Document3 pagesQ 9 (B)Himal SigdelNo ratings yet

- Security Council: United NationsDocument17 pagesSecurity Council: United NationsIlove PoornNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Humanitarian Aid On Post Conflict Development in Borno StateDocument16 pagesThe Impact of Humanitarian Aid On Post Conflict Development in Borno Stateyeabsera danielNo ratings yet

- Study Guide - Rohingya PeopleDocument17 pagesStudy Guide - Rohingya PeopleArishthaNo ratings yet

- A Research Paper On Do Refugees Create IDocument8 pagesA Research Paper On Do Refugees Create INipu TabasumNo ratings yet

- Rohingya Final Without AnalysisDocument40 pagesRohingya Final Without AnalysisGolam Samdanee TaneemNo ratings yet

- Conflict Analysis of Muslim Mindanao PDFDocument31 pagesConflict Analysis of Muslim Mindanao PDFClint RamosNo ratings yet

- Maung Z Arni Alice Cowley The SDocument73 pagesMaung Z Arni Alice Cowley The SDaksh MiddhaNo ratings yet

- Hybrid WarfareDocument11 pagesHybrid WarfareZarNo ratings yet

- ISFRPOL - Research PresentationDocument12 pagesISFRPOL - Research PresentationGAB GABRIELNo ratings yet

- Citizenship, Nationalism and Refugeehood of Rohingyas in Southern AsiaFrom EverandCitizenship, Nationalism and Refugeehood of Rohingyas in Southern AsiaNasreen ChowdhoryNo ratings yet

- Along the Integral Margin: Uneven Development in a Myanmar Squatter SettlementFrom EverandAlong the Integral Margin: Uneven Development in a Myanmar Squatter SettlementNo ratings yet

- Ngô Thị Mỹ Hoa - writingDocument2 pagesNgô Thị Mỹ Hoa - writingNhư TrầnNo ratings yet

- Ngô Thị Mỹ Hoa - 1757020017- ReadingDocument3 pagesNgô Thị Mỹ Hoa - 1757020017- ReadingNhư TrầnNo ratings yet

- Essay SleepDocument2 pagesEssay SleepNhư TrầnNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ THI HSG ANH 6 02Document6 pagesĐỀ THI HSG ANH 6 02Như TrầnNo ratings yet

- Verbal Communic-WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesVerbal Communic-WPS Officechandy RendajeNo ratings yet

- Del Rosario-Igtiben V RepublicDocument1 pageDel Rosario-Igtiben V RepublicGel TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Unit - V: PowerDocument32 pagesUnit - V: PowerVaira PerumalNo ratings yet

- Controller Job DescriptionDocument3 pagesController Job DescriptionEkka PrasetiaNo ratings yet

- FCE Exam 3 ListeningDocument6 pagesFCE Exam 3 ListeningSaul MendozaNo ratings yet

- OSI Layer & TCP Protocols - PostQuiz - Attempt ReviewDocument4 pagesOSI Layer & TCP Protocols - PostQuiz - Attempt Reviewvinay Murakambattu100% (1)

- GraduatingresumeDocument3 pagesGraduatingresumeapi-277434369No ratings yet

- Microbes in Ferment@3Document13 pagesMicrobes in Ferment@3T Vinit ReddyNo ratings yet

- Jara, John Leoj I. Prof - Dioshua Sapla Plate 1: Ground Floor Plan Second Floor PlanDocument1 pageJara, John Leoj I. Prof - Dioshua Sapla Plate 1: Ground Floor Plan Second Floor PlanWynne TillasNo ratings yet

- IBM UML 2.0 Advanced NotationsDocument21 pagesIBM UML 2.0 Advanced NotationsKeerthana SubramanianNo ratings yet

- 245-Article Text-493-1-10-20220221Document8 pages245-Article Text-493-1-10-20220221Mr DNo ratings yet

- Hill, Therapist Techniques, Client Involvement, and The Therapeutic Relationship, (Hill, 2005)Document12 pagesHill, Therapist Techniques, Client Involvement, and The Therapeutic Relationship, (Hill, 2005)Osman CastroNo ratings yet

- Time QuotesDocument6 pagesTime Quoteschristophdollis100% (6)

- 126 1043 8 PB 1Document12 pages126 1043 8 PB 1MussyNo ratings yet

- FBS IntroductionDocument50 pagesFBS IntroductionPerly Algabre PantojanNo ratings yet

- History of Children LiteratureDocument3 pagesHistory of Children Literatureemil_masagca1467No ratings yet

- Vijaya Bank ChanchalDocument2 pagesVijaya Bank ChanchalShubham sharmaNo ratings yet

- Dip One GoroDocument8 pagesDip One GoroanakayamNo ratings yet

- Vitamin B2Document10 pagesVitamin B2Rida IshaqNo ratings yet

- Keerthi Question BankDocument65 pagesKeerthi Question BankKeerthanaNo ratings yet

- Flue & Chimney BrochureDocument15 pagesFlue & Chimney BrochureAirtherm Engineering LtdNo ratings yet

- R. Kelly Fan Letter To CourtDocument4 pagesR. Kelly Fan Letter To Court5sos DiscoNo ratings yet

- A La Nanita NanaDocument1 pageA La Nanita Nanabill desaillyNo ratings yet

- Reading in Philippines HistoryDocument7 pagesReading in Philippines Historyrafaelalmazar416No ratings yet

- Impact of Work Life Balance On Women Employees (1) PsDocument13 pagesImpact of Work Life Balance On Women Employees (1) PsPunnya SelvarajNo ratings yet

- Fortinet OT - PublishedDocument59 pagesFortinet OT - PublishedCryptonesia IndonesiaNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Spoilage, Defective Units and Scrap: 1. TerminologyDocument13 pagesAccounting For Spoilage, Defective Units and Scrap: 1. TerminologyWegene Benti UmaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Individual AssignmentDocument13 pagesAssignment 3 Individual AssignmentThư Phan MinhNo ratings yet