Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

34 viewsEnvironmental Reportin1

Environmental Reportin1

Uploaded by

A KyariEnvironmental reporting refers to how organizations communicate information about their interactions with the natural environment. It most commonly involves large companies voluntarily publishing standalone environmental reports or including environmental data in annual reports. While environmental reporting began in the 1990s, it remains mostly voluntary and uneven in quality. For reporting to be truly useful, reports would need to provide a full ecological footprint and eco-balance of the organization's impacts. In the future, environmental reporting may need to focus more on assessing organizations' contributions to sustainability and become a legal requirement.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Netflix PPT - DigitalDocument82 pagesNetflix PPT - DigitalPuneeth Shastry80% (5)

- Environmental Reporting: January 2005Document3 pagesEnvironmental Reporting: January 2005AnandNo ratings yet

- Green Accounting - A Proposition For EA/ER Conceptual Implementation MethodologyDocument22 pagesGreen Accounting - A Proposition For EA/ER Conceptual Implementation Methodologyaisyah nabilaNo ratings yet

- GreenAcc PDFDocument18 pagesGreenAcc PDFMadalina BogdanNo ratings yet

- Environmental Accounting and ReportingDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Accounting and ReportingPeter ChuaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management Accounting Thesis PDFDocument10 pagesEnvironmental Management Accounting Thesis PDFbrendatorresalbuquerque100% (2)

- Environmental Accounting and ReportingDocument10 pagesEnvironmental Accounting and ReportingnamicheriyanNo ratings yet

- Fujitsu Environmental ActgDocument16 pagesFujitsu Environmental ActgArlene QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management Accounting: IntroductionDocument8 pagesEnvironmental Management Accounting: Introductionchin_lord8943No ratings yet

- Sustainability ReportingDocument22 pagesSustainability ReportingGusNo ratings yet

- 11.vol 0005www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper - No 1-2 - Pp. 106-123Document19 pages11.vol 0005www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper - No 1-2 - Pp. 106-123Alexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Environmental Information Disclosure On The Quality of Financial ReportsDocument67 pagesImpacts of Environmental Information Disclosure On The Quality of Financial ReportsEsther OyewumiNo ratings yet

- Environment Management and Disclosure Practices of Indian CompaniesDocument6 pagesEnvironment Management and Disclosure Practices of Indian CompaniesmonaruNo ratings yet

- LectureDocument36 pagesLectureCristina Andreea MNo ratings yet

- Green Marketing ManagementDocument35 pagesGreen Marketing Managementgurvinder12No ratings yet

- An Empirical Investigation of U.K. Environmental Targets Disclosure The Role of Environmental Governance and PerformanceDocument36 pagesAn Empirical Investigation of U.K. Environmental Targets Disclosure The Role of Environmental Governance and Performanceakuaamissah87No ratings yet

- Introduction To Sustainability ReportingDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Sustainability Reportingadilla ikhsaniiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Environmental Impact AssessmentDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Environmental Impact Assessmentsabanylonyz2No ratings yet

- Environmental Protection: Is It Bad For The Economy? A Non-Technical Summary of The LiteratureDocument13 pagesEnvironmental Protection: Is It Bad For The Economy? A Non-Technical Summary of The LiteratureNayeem SazzadNo ratings yet

- Defining Environmental Performance IndicatorsDocument12 pagesDefining Environmental Performance IndicatorsNicholas Lim Ca TouNo ratings yet

- Yeunyong, W. (2014) .Document5 pagesYeunyong, W. (2014) .Daniela MuñozNo ratings yet

- Rao Et Al. 2012 Corporate Governance and Environmental Reporting An Australian StudyDocument21 pagesRao Et Al. 2012 Corporate Governance and Environmental Reporting An Australian StudyHientnNo ratings yet

- Corporate Disclosures: Competitive Disclosure Hypothesis Using 1991 Annual Report DataDocument21 pagesCorporate Disclosures: Competitive Disclosure Hypothesis Using 1991 Annual Report Datarealgirl14No ratings yet

- FINAL Summary Sustainability Reporting-11-03-11 PDFDocument7 pagesFINAL Summary Sustainability Reporting-11-03-11 PDFAlina ComanescuNo ratings yet

- Corporate Sustainability Reporting OpporDocument16 pagesCorporate Sustainability Reporting OpporOkonkwo VictorNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document7 pagesArticle 2Chetan BagriNo ratings yet

- Adams 2004 The Ethical, Social and Environmental Reporting GapDocument27 pagesAdams 2004 The Ethical, Social and Environmental Reporting GapTandiweKathrinNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis On Environmental AccountingDocument6 pagesPHD Thesis On Environmental Accountingkimstephenswashington100% (2)

- Climate Solutions Investments: Alexander Cheema-Fox George Serafeim Hui (Stacie) WangDocument40 pagesClimate Solutions Investments: Alexander Cheema-Fox George Serafeim Hui (Stacie) WangAmirulamin Mat YunusNo ratings yet

- Final FAMADocument14 pagesFinal FAMAChiristinaw WongNo ratings yet

- MWM Water Discussion PaperDocument17 pagesMWM Water Discussion PaperGreen Economy CoalitionNo ratings yet

- Cowan 2005Document16 pagesCowan 2005Amry RayendraNo ratings yet

- Corporate Environmental ReportingDocument19 pagesCorporate Environmental ReportingJovelle LigsayNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management AccountingDocument7 pagesEnvironmental Management AccountingrzhrsNo ratings yet

- Sustainbility StrategyDocument6 pagesSustainbility StrategymasNo ratings yet

- AMR Nine Sustainability TrendsDocument3 pagesAMR Nine Sustainability TrendsSondhaya SudhamasapaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Sustainability Reporting On Financial Performance An Empirical Study Using Listed CompaniesDocument24 pagesThe Effect of Sustainability Reporting On Financial Performance An Empirical Study Using Listed CompaniesAprilian TsalatsaNo ratings yet

- Braam 2016Document11 pagesBraam 2016Suwarno suwarnoNo ratings yet

- Unit 10Document13 pagesUnit 10ammar mughalNo ratings yet

- TRIPLE BOTTOM LINE-analysis of Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesTRIPLE BOTTOM LINE-analysis of Literature ReviewKazi Sajharul Islam 1410028630No ratings yet

- The Impact of Environmental Accounting and Reporting On Sustainable Development in NigeriaDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Environmental Accounting and Reporting On Sustainable Development in NigeriaSunny_BeredugoNo ratings yet

- New Perspectives On Corporate Reporting: Social-Economic and Environmental InformationDocument6 pagesNew Perspectives On Corporate Reporting: Social-Economic and Environmental InformationManiruzzaman ShesherNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument20 pagesRetrieveNada KhaledNo ratings yet

- Ecological FootprintDocument6 pagesEcological FootprintHope Gal0% (1)

- A Decade of Sustainability Reporting: Developments and SignificanceDocument14 pagesA Decade of Sustainability Reporting: Developments and SignificanceTawsif HasanNo ratings yet

- 11.vol 0003www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper No 2 PP 100-116Document18 pages11.vol 0003www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper No 2 PP 100-116Alexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Green Information Technology: A Strategy To Become Socially Responsible Software OrganizationDocument17 pagesGreen Information Technology: A Strategy To Become Socially Responsible Software Organizationadmin2146No ratings yet

- SSRN-IfRS and SustainabilityDocument34 pagesSSRN-IfRS and SustainabilityVineet ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Carbon Accounting A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesCarbon Accounting A Systematic Literature Reviewc5e4jfpnNo ratings yet

- The Environmental Reporting Expectations Gap: Australian EvidenceDocument34 pagesThe Environmental Reporting Expectations Gap: Australian Evidencepepin fachrizaNo ratings yet

- 18Document6 pages18Tekaling NegashNo ratings yet

- Dua PDFDocument10 pagesDua PDFEwin KaroyaniNo ratings yet

- 13P PDFDocument25 pages13P PDFSagar Hossain SrabonNo ratings yet

- Addressing A Broad Scope SEA Research Agenda: Editorial NotesDocument4 pagesAddressing A Broad Scope SEA Research Agenda: Editorial NotesAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Azapagic and Perdan, 2000 - Indicators For SDDocument19 pagesAzapagic and Perdan, 2000 - Indicators For SDAdrian OblenaNo ratings yet

- NZMAC Full Paper PubDocument27 pagesNZMAC Full Paper PubEromina LilyNo ratings yet

- Event Study PaperDocument42 pagesEvent Study PaperRiazboniNo ratings yet

- Sustainability AccountingDocument13 pagesSustainability Accountingunitv onlineNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Environmental Disclosure: Department of Accounting, University of Benin, Nigeria. +234-8065074504Document10 pagesDeterminants of Environmental Disclosure: Department of Accounting, University of Benin, Nigeria. +234-8065074504Hasan BasriNo ratings yet

- Predominant Factors for Firms to Reduce Carbon EmissionsFrom EverandPredominant Factors for Firms to Reduce Carbon EmissionsNo ratings yet

- Empowering Green Initiatives with IT: A Strategy and Implementation GuideFrom EverandEmpowering Green Initiatives with IT: A Strategy and Implementation GuideNo ratings yet

- Table of Contents9jeyptunvj 1Document5 pagesTable of Contents9jeyptunvj 1A KyariNo ratings yet

- Godwin Okpe Technical Report Siwes-5: September 2022Document44 pagesGodwin Okpe Technical Report Siwes-5: September 2022A KyariNo ratings yet

- Yusuf Yarima 2Document11 pagesYusuf Yarima 2A KyariNo ratings yet

- ASLM-WPS OfficeDocument1 pageASLM-WPS OfficeA KyariNo ratings yet

- Chapter Thre To FiveDocument7 pagesChapter Thre To FiveA KyariNo ratings yet

- National Identity Management System: Federal Republic of NigeriaDocument1 pageNational Identity Management System: Federal Republic of NigeriaA Kyari100% (1)

- Special 2023Document1 pageSpecial 2023A KyariNo ratings yet

- Proposal SQDocument3 pagesProposal SQA KyariNo ratings yet

- Academic Calender-1Document1 pageAcademic Calender-1A KyariNo ratings yet

- 2021-2022 2&4 Sem Result C.E PDFDocument7 pages2021-2022 2&4 Sem Result C.E PDFA KyariNo ratings yet

- # NPC Id Full Name Date Creat Email Nin Phone Numlga QualificatiDocument20 pages# NPC Id Full Name Date Creat Email Nin Phone Numlga QualificatiA KyariNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTIONDocument19 pagesINTRODUCTIONA KyariNo ratings yet

- Transaction ReceiptDocument1 pageTransaction ReceiptA KyariNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument5 pagesUntitledA KyariNo ratings yet

- RTP Dec 18 AnsDocument36 pagesRTP Dec 18 AnsbinuNo ratings yet

- GPL NotesDocument11 pagesGPL NotesRyDNo ratings yet

- Strategy SsDocument8 pagesStrategy SsKaran HingmireNo ratings yet

- Math SBADocument28 pagesMath SBATiana ThomasNo ratings yet

- Munir Industry Exemption 2021 FBRDocument2 pagesMunir Industry Exemption 2021 FBRAqeel ZahidNo ratings yet

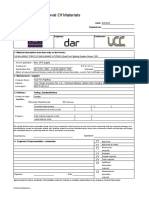

- Submittal For Approval of Materials Section 13967 - Clean-Agent Fire Extinguishing SystemsDocument1 pageSubmittal For Approval of Materials Section 13967 - Clean-Agent Fire Extinguishing SystemsFaruh IsmatovNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Chapter 2Document7 pagesTutorial Chapter 2ammar naimNo ratings yet

- Mayuri Bhogle - Black BookDocument44 pagesMayuri Bhogle - Black BookPooja AdhikariNo ratings yet

- History of Swot AnalysisDocument4 pagesHistory of Swot AnalysisAzeem Ali Shah100% (1)

- Nasscom Technology and Leadership Forum 2024 - ScheduleDocument4 pagesNasscom Technology and Leadership Forum 2024 - ScheduleRakesh ArukapalliNo ratings yet

- 5 - Sales and Service Cloud DatasheetDocument2 pages5 - Sales and Service Cloud Datasheetitsme.mahe263No ratings yet

- Siddu PDFDocument2 pagesSiddu PDFNikhil MohaneNo ratings yet

- @ Reading Comprehension Workshop On Technical Terms On Supply and Technical Terms On Supply and DemandDocument5 pages@ Reading Comprehension Workshop On Technical Terms On Supply and Technical Terms On Supply and Demandrafael santosNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1 Genpact Services LLC: FactsDocument10 pagesCase Study 1 Genpact Services LLC: FactsAmit GroverNo ratings yet

- Bio-Chemical Data of DR - Vijayan Gurumurthy Iyer - 21 ST December 2021Document176 pagesBio-Chemical Data of DR - Vijayan Gurumurthy Iyer - 21 ST December 2021Dr.Vijayan Gurumurthy IyerNo ratings yet

- How To Approach Reading Test Part OneDocument3 pagesHow To Approach Reading Test Part OneA DiomaNo ratings yet

- Costs - Concepts and ClassificationsDocument5 pagesCosts - Concepts and ClassificationsCarlo B CagampangNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Sustainability ReportingDocument25 pagesAn Introduction To Sustainability Reportingawe gyiNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: 1 Running Head: VRIO AnalysisDocument5 pagesThis Study Resource Was: 1 Running Head: VRIO AnalysisMustika ZakiahNo ratings yet

- Infiniti BenefitsDocument11 pagesInfiniti Benefitssu maiyahNo ratings yet

- End Term Question Paper - FDM - Term V Batch 2020-22Document2 pagesEnd Term Question Paper - FDM - Term V Batch 2020-22sumit rajNo ratings yet

- Kotler Pom17e PPT 19Document39 pagesKotler Pom17e PPT 19Hà Lê100% (1)

- Sample Cash Flow Projection TemplateDocument1 pageSample Cash Flow Projection TemplateAndraya BarthoNo ratings yet

- 1) Circulytics - Brochure ENGDocument5 pages1) Circulytics - Brochure ENGTeja Harjaya SamadhiNo ratings yet

- TFT Palm Oil Paper Number TwoDocument13 pagesTFT Palm Oil Paper Number TworachmathellyantoNo ratings yet

- SCA-528 - Iscala SSRS ReportsDocument42 pagesSCA-528 - Iscala SSRS ReportsIvan FaneiteNo ratings yet

- Peranggaran - #8 Anggaran OverHeadDocument40 pagesPeranggaran - #8 Anggaran OverHeadcitra kurniaNo ratings yet

- Court of Tax Appeals: VENUE: Second Division Courtroom, 3Document4 pagesCourt of Tax Appeals: VENUE: Second Division Courtroom, 304 pandaNo ratings yet

- Invoice 1Document1 pageInvoice 1zagher23No ratings yet

Environmental Reportin1

Environmental Reportin1

Uploaded by

A Kyari0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

34 views10 pagesEnvironmental reporting refers to how organizations communicate information about their interactions with the natural environment. It most commonly involves large companies voluntarily publishing standalone environmental reports or including environmental data in annual reports. While environmental reporting began in the 1990s, it remains mostly voluntary and uneven in quality. For reporting to be truly useful, reports would need to provide a full ecological footprint and eco-balance of the organization's impacts. In the future, environmental reporting may need to focus more on assessing organizations' contributions to sustainability and become a legal requirement.

Original Description:

Environment

Original Title

ENVIRONMENTAL REPORTIN1

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentEnvironmental reporting refers to how organizations communicate information about their interactions with the natural environment. It most commonly involves large companies voluntarily publishing standalone environmental reports or including environmental data in annual reports. While environmental reporting began in the 1990s, it remains mostly voluntary and uneven in quality. For reporting to be truly useful, reports would need to provide a full ecological footprint and eco-balance of the organization's impacts. In the future, environmental reporting may need to focus more on assessing organizations' contributions to sustainability and become a legal requirement.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

34 views10 pagesEnvironmental Reportin1

Environmental Reportin1

Uploaded by

A KyariEnvironmental reporting refers to how organizations communicate information about their interactions with the natural environment. It most commonly involves large companies voluntarily publishing standalone environmental reports or including environmental data in annual reports. While environmental reporting began in the 1990s, it remains mostly voluntary and uneven in quality. For reporting to be truly useful, reports would need to provide a full ecological footprint and eco-balance of the organization's impacts. In the future, environmental reporting may need to focus more on assessing organizations' contributions to sustainability and become a legal requirement.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 10

ENVIRONMENTAL REPORTING

Definition and Introduction

“Environmental reporting” refers to the preparation, presentation and

communication of information relating to an organization’s interactions with the

natural environment. Such reporting can relate to all organizations but is most

usually associated with (typically large) companies. Equally, environmental

reporting is most commonly associated with self-reporting by organizations

although reporting about other organizations by government agencies and other

independent bodies and pressure groups remains an important pressure for

environmental accountability.

Reporting about environmental interactions may occur within the financial

statements. Typically, such reporting would be related to liabilities, commitments

and contingencies for such matters as the remediation of contaminated land or

other financial concerns arising from pollution. (The USA’s `Superfund’

legislation and reporting is perhaps the best known and developed reporting in this

area). However, such financial reporting is really not about environmental issues as

such but about financial issues which, in this case, arise from environmental

legislation. Environmental reporting is much more typically associated with the

reporting of quantitative and detailed environmental data within the non-financial

sections of the annual report or in stand-alone (including website-based)

Environmental Reports. Such reports might include pollution emissions to land, air

or water, resources used, or wildlife habitat damaged or re-established.

History and Regulation

Although environmental reporting has occurred for some time, modern

environmental reporting tends to be dated from 1990 when the first substantive

stand-alone environmental reports from companies such as Norsk Hydro (Norway

and the UK), British Airways (UK), BSO/Origin (Netherlands) and Noranda

(Canada) set the pace in a new wave of voluntary environmental reporting. The

vast majority of current environmental reporting is voluntary. It has grown slowly

but steadily and become much more widespread throughout the last 10 years or so.

It remains, however, dominated by the big, corporations. These businesses have

expended great effort to persuade the public and governments that environmental

reporting can remain a voluntary activity but, unfortunately, as long as it remains

voluntary the majority of the world’s companies will continue to ignore it.

The United Nations has been at the forefront of attempts to make environmental

reporting compulsory. Countries as diverse as Denmark, Netherlands, Australia

and Korea have all introduced some form of compulsory reporting and despite

business efforts (most obviously in New Zealand and the UK), the trend is now one

of slow but inexorable progress towards much-needed compulsory environmental

reporting.

Why environmental reporting?

The historical reasons for undertaking environmental reporting vary from region to

region. Studies indicate that the main drivers in Europe included duty to the

environment, public relations, gaining a competitive advantage, and legal

compliance. In North America shareholder pressure seemed to be more significant

than legal compliance. In Japan consumer and shareholder pressure, campaign

interest groups, environmental duty and public relations all scored higher than

legal compliance as reasons for undertaking environmental reporting (Wheeler and

Elkington, 2001).

The use of environmental reports depends very much upon the target audience of

the report. Corporate environmental reports are used by investors to check whether

there are environmental liabilities which if not properly managed could cost them

heavy losses in dividends and returns on their investments. There are indications

that the contents of environmental reports are being used more extensively by

NGOs and pressure groups to encourage greater responsibility towards the

environment. In some cases, there is opposition to certain types of environmental

reports because it is believed that they release information which could be used by

other parties for their own gain. For example, companies, by analysing the

environmental statistics of their competitors, could gain valuable insights into their

technology being used and gain competitive advantage. There are also calls from

some quarters for more information in environmental reports to enable a better

picture to be built of environmental performance. As with any form of reporting,

the cost of generating the information and producing the reports must be carefully

weighed against the benefits gained from the reports.

Some of the benefits of corporate environmental reporting include:

* Improved organisational reputation;

* Enhanced transparency, accountability and responsible governance;

* Enhanced communication with stakeholders;

* Contribution to wider education of the public;

* Improved risk management;

* Identification of potential opportunities for the reduction of resource use and

operating costs;

* Improved customer confidence and exposure; and

* Improved competitive advantage (DEFRA, 2001; Merrick and Crookshanks,

2001, Australian Government, 2004).

Format and Quality

The quality of voluntary environmental reporting is very diverse despite stimuli for

increased quality from ethical investment funds, environmental campaigners and a

range of Environmental Reporting Award Schemes, which were first developed by

the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) in Britain. It is

common practice for an environmental report to include information on the

company’s policies and procedures, its environmental management systems and

data relating to its pollution and trends in emissions. Indeed, most reports tend to

emphasize eco-efficiency – which refers to the reduction of resource and energy

use and waste production per unit of product or service. Very few reports,

however, deal with the organization’s complete environmental interactions. For

this, reports must include eco-balances – which identify all inputs, outputs and

wastes of the organization – plus an ecological footprint – which estimates the

total environmental impact of the organization. Whilst companies can demonstrate

great success in Eco-efficiency, most companies’ ecological footprint continues to

rise. Companies, naturally, do not want to make such data public.

Sustainability and the Future

Our present systems of economic and business organization are simply not

sustainable. Environmental (and, increasingly, social responsibility) reporting is

beginning to address the extent to which a company is (or is not) contributing to

sustainable development. Most companies are currently profoundly un-sustainable

and do not, of course, wish to formally disclose this in an annual environmental

report. The Global Reporting Initiative is a voluntary process which is slowly

developing increasingly tough guidelines that, eventually, will encourage

companies to report on their (lack of) contribution to sustainability.

Environmental reporting is here to stay and, eventually will become a legal

requirement. Whether serious and substantive sustainable development reporting

(something which is still fairly trivial and under-developed) can be adopted quickly

enough to help prevent the further spread of irreversible global environmental and

social desecration seems, unfortunately, very unlikely.

Presentation of a corporate environmental report

The presentation format of environmental reports is very important in ensuring that

the target audience can assimilate the information in the report. There are many

different factors that can influence successful acceptance of an environmental

report. A few of these are discussed below.

Hard Copy versus Internet

There is a growing movement to report on the internet instead of producing hard

copy reports. This is being prompted by claims that it makes the reports more

accessible and it also reduces costs. Both arguments are correct but they need to be

seen in the context of stakeholders. If the stakeholders are located in rural Africa

with limited access to electricity and the Internet, then on-line reporting is

inappropriate.

Sometimes electronic reporting can benefit specific target groups such as

employees who make extensive use of an Intranet system. In such a case, a web

based system would be ideal. There are a number of models and templates

available but the best known is the template developed by Martin Charter

(Charter,1998). Charter’s template is a web-based report framework into which

data can be easily and quickly loaded. The template is inexpensive compared to

paper based reports and enables easy access. It is important to consult with

stakeholders who will be using the reports to understand what their needs are and

what reporting modes best suit their circumstances.

Language

Another issue is the question of reporting in different languages. There are many

companies whose working language is not English but they produce English

language versions (on-line and in hard copy) because English is perceived as the

leading international “business” language. Some international companies produce

summary reports of their environmental or sustainability reports in the local

language of their subsidiaries as a means of making information more readily

available to local stakeholders.

“Glossy” versus “Plain”

Glossy reports that are in full colour, and printed on high quality paper may be

considered by some readers as “greenwash”. A reverse line of thinking is to spend

equally large sums of money on using high quality expensive, recycled paper and

presenting an “environmentally friendly” image. Once again, this kind of approach

needs to be tested against the views and perspectives of the target audience of the

report. For example, activists are less likely to be motivated by glossy reports

whereas some shareholders might see this reflecting a prosperous image and in

keeping with their desires to see regular and healthy dividends being distributed.

Remember your Target Groups (Stakeholders)

Target groups for reports consist of a range of stakeholders. It is often possible to

prepare a report which can cater for the full range of stakeholders. However, it

should be borne in mind that there may be occasions where specialized reports are

needed for specific stakeholder groups. For example, it may be necessary to

prepare a special report for the regulatory authorities because they require specific

data in a particular format or they may require detail which would not be helpful or

clear to the general public. Trying to make a report say too many things in too

many different ways can be confusing to some stakeholders and can also create the

wrong impression. Consultation with stakeholders is an important stage in the

reporting process.

Examples of Stakeholders (also known as interested and affected parties)

• Employees

• Trade Unions and Staff Associations

• Investors and potential investors

• Investment analysts and advisors

• Customers and suppliers

• Competitors

• Contractors

• Banks, Finance Houses, Lending Institutions, Insurers

• Regulatory and legislative bodies (local, provincial, national)

• Neighbouring and regional communities

• Press and media (hard copy and electronic)

• Business, administrative, academic and research institutions (national &

international)

• Chambers of Commerce and Industry and other business associations

• Environmental groups

• Other Non-Governmental Organisations

• Consumer interest groups

• Civil Society groups and associations

• General Public

Use of environmental reports

Environmental reports can be most useful when communicating with stakeholders

on issues such as business development, investment, capital development funding,

corporate responsibility, expansion, community impacts, and recruitment. They

provide a public face for the organisation and can add credibility to, and

acceptance of, the activities carried out by the organisation. Obviously, if the

information is incorrect or if the organisation does not meet the targets it sets or

does not keep commitments made in reports, the result can be embarrassing and

have a significant impact upon the organisation’s reputation and, in some

circumstances, the share price. It is for this reason that the whole organisation must

be aware of the commitment made within the report and be willing to accept and

achieve the targets and commitments made.

Legal aspects associated with environmental reporting

The legal aspects of environmental reporting reflect the differing perspectives that

might be taken by stakeholders with various agendas. Some stakeholders argue that

by providing wide ranging environmental information the company or organisation

is more exposed to legal action from aggrieved parties. The counter argument is

that if the data are freely available, they are unlikely to be of a nature where it

could provide motivation for legal action. If companies cooperate with the

authorities on compliance issues, as frequently occurs in South Africa, the data

appearing in environmental reports are probably already in the public domain. In

contrast, the US approach of “command and control” has created an environment

whereby companies only provide such information to the authorities as is required

by law and audits are conducted through legal advisers to ensure that the data are

protected by legal privilege.

Psychological perspectives in reporting

Environmental issues tend to evoke emotions in many people and thus the

environmental report can have both a positive and negative psychological impact.

That impact should not be underestimated and if carefully managed, can have

positive benefits for the organisation and its reputation. If stakeholders are

consulted and participate in the planning, development and content of the report,

the organisation could more readily find itself accepted as a part of the community

within which it operates. The benefits of friendly and supportive neighbours can

never be underestimated and also result in business benefits in the long term.

Stakeholder inputs and feedback

The ideal situation is to establish clear two-way communication with stakeholders

on the content of environmental reports. Wherever possible, consultation with

stakeholders before the reporting process starts will assist in understanding what

priorities are important to stakeholders. The report is one of the mechanisms that

provides credibility, confidence and trust in the organisation. By providing

information which increases confidence, in a format that is easily and readily

understood, stakeholders are more likely to invest, support, accept and

accommodate the organisation, whether they are shareholders, NGOs or

neighbours.

Commercial benefits of environmental reporting

There are mixed views on whether environmental reporting has direct financial

benefits. A study on the role of environmental reporting in supporting share values

in FTSE 100 companies, (FTSE is the name of an index company) is an index

containing the largest 100 companies (by market capitalisation) listed on the

London Stock Exchange (Walmsley & Bond 2003) concluded that, on average,

reporting companies did not perform better than their non-reporting counterparts.

However, a broad-based review of the energy and utilities and financial services

sectors suggested that companies producing the best reports saw this contributing

to improved share prices and enhancement of their reputation as good companies

to invest in. The study also indicated that those companies that reported,

experienced reduced share price volatility and probably showed steadier growth.

Environmental or sustainability reporting provides added information to investors

to identify eco-efficient sources of investment and thus reinforces the value

(financial and non-financial) of sound environmental management practices, which

include environmental reporting.

Quality Control

The reporting process must be supported by a system of checks and quality

controls to ensure that the data used and presented are as accurate as possible.

Internal checks

need to be carried out before external verification is undertaken. Whilst many

organisations will have internal auditors to check the financial data, the extension

of this checking process to non-financial data is often not undertaken. The

motivation to provide the resources to carry out the internal checking and quality

control is based upon the organisation’s management of risk. Risk is usually seen

primarily from the perspective of financial risk and sometimes the financial costs

of, say, health and safety risks. Non-financial data such as safety, health and

environmental statistics forms the base for calculating the risks and financial

liabilities associated with such possibilities as occupational health compensation

claims, groundwater pollution, contamination of sites, air emission releases, and

long-term exposure of neighbours to pollutants. Furthermore, it’s the accuracy and

presence of safety, health and environmental statistics that forms a part of the audit

document trail, should an organization ever need to defend itself from legal actions

associated with health exposures, pollution and contamination.

You might also like

- Netflix PPT - DigitalDocument82 pagesNetflix PPT - DigitalPuneeth Shastry80% (5)

- Environmental Reporting: January 2005Document3 pagesEnvironmental Reporting: January 2005AnandNo ratings yet

- Green Accounting - A Proposition For EA/ER Conceptual Implementation MethodologyDocument22 pagesGreen Accounting - A Proposition For EA/ER Conceptual Implementation Methodologyaisyah nabilaNo ratings yet

- GreenAcc PDFDocument18 pagesGreenAcc PDFMadalina BogdanNo ratings yet

- Environmental Accounting and ReportingDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Accounting and ReportingPeter ChuaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management Accounting Thesis PDFDocument10 pagesEnvironmental Management Accounting Thesis PDFbrendatorresalbuquerque100% (2)

- Environmental Accounting and ReportingDocument10 pagesEnvironmental Accounting and ReportingnamicheriyanNo ratings yet

- Fujitsu Environmental ActgDocument16 pagesFujitsu Environmental ActgArlene QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management Accounting: IntroductionDocument8 pagesEnvironmental Management Accounting: Introductionchin_lord8943No ratings yet

- Sustainability ReportingDocument22 pagesSustainability ReportingGusNo ratings yet

- 11.vol 0005www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper - No 1-2 - Pp. 106-123Document19 pages11.vol 0005www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper - No 1-2 - Pp. 106-123Alexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Environmental Information Disclosure On The Quality of Financial ReportsDocument67 pagesImpacts of Environmental Information Disclosure On The Quality of Financial ReportsEsther OyewumiNo ratings yet

- Environment Management and Disclosure Practices of Indian CompaniesDocument6 pagesEnvironment Management and Disclosure Practices of Indian CompaniesmonaruNo ratings yet

- LectureDocument36 pagesLectureCristina Andreea MNo ratings yet

- Green Marketing ManagementDocument35 pagesGreen Marketing Managementgurvinder12No ratings yet

- An Empirical Investigation of U.K. Environmental Targets Disclosure The Role of Environmental Governance and PerformanceDocument36 pagesAn Empirical Investigation of U.K. Environmental Targets Disclosure The Role of Environmental Governance and Performanceakuaamissah87No ratings yet

- Introduction To Sustainability ReportingDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Sustainability Reportingadilla ikhsaniiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Environmental Impact AssessmentDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Environmental Impact Assessmentsabanylonyz2No ratings yet

- Environmental Protection: Is It Bad For The Economy? A Non-Technical Summary of The LiteratureDocument13 pagesEnvironmental Protection: Is It Bad For The Economy? A Non-Technical Summary of The LiteratureNayeem SazzadNo ratings yet

- Defining Environmental Performance IndicatorsDocument12 pagesDefining Environmental Performance IndicatorsNicholas Lim Ca TouNo ratings yet

- Yeunyong, W. (2014) .Document5 pagesYeunyong, W. (2014) .Daniela MuñozNo ratings yet

- Rao Et Al. 2012 Corporate Governance and Environmental Reporting An Australian StudyDocument21 pagesRao Et Al. 2012 Corporate Governance and Environmental Reporting An Australian StudyHientnNo ratings yet

- Corporate Disclosures: Competitive Disclosure Hypothesis Using 1991 Annual Report DataDocument21 pagesCorporate Disclosures: Competitive Disclosure Hypothesis Using 1991 Annual Report Datarealgirl14No ratings yet

- FINAL Summary Sustainability Reporting-11-03-11 PDFDocument7 pagesFINAL Summary Sustainability Reporting-11-03-11 PDFAlina ComanescuNo ratings yet

- Corporate Sustainability Reporting OpporDocument16 pagesCorporate Sustainability Reporting OpporOkonkwo VictorNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document7 pagesArticle 2Chetan BagriNo ratings yet

- Adams 2004 The Ethical, Social and Environmental Reporting GapDocument27 pagesAdams 2004 The Ethical, Social and Environmental Reporting GapTandiweKathrinNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis On Environmental AccountingDocument6 pagesPHD Thesis On Environmental Accountingkimstephenswashington100% (2)

- Climate Solutions Investments: Alexander Cheema-Fox George Serafeim Hui (Stacie) WangDocument40 pagesClimate Solutions Investments: Alexander Cheema-Fox George Serafeim Hui (Stacie) WangAmirulamin Mat YunusNo ratings yet

- Final FAMADocument14 pagesFinal FAMAChiristinaw WongNo ratings yet

- MWM Water Discussion PaperDocument17 pagesMWM Water Discussion PaperGreen Economy CoalitionNo ratings yet

- Cowan 2005Document16 pagesCowan 2005Amry RayendraNo ratings yet

- Corporate Environmental ReportingDocument19 pagesCorporate Environmental ReportingJovelle LigsayNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management AccountingDocument7 pagesEnvironmental Management AccountingrzhrsNo ratings yet

- Sustainbility StrategyDocument6 pagesSustainbility StrategymasNo ratings yet

- AMR Nine Sustainability TrendsDocument3 pagesAMR Nine Sustainability TrendsSondhaya SudhamasapaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Sustainability Reporting On Financial Performance An Empirical Study Using Listed CompaniesDocument24 pagesThe Effect of Sustainability Reporting On Financial Performance An Empirical Study Using Listed CompaniesAprilian TsalatsaNo ratings yet

- Braam 2016Document11 pagesBraam 2016Suwarno suwarnoNo ratings yet

- Unit 10Document13 pagesUnit 10ammar mughalNo ratings yet

- TRIPLE BOTTOM LINE-analysis of Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesTRIPLE BOTTOM LINE-analysis of Literature ReviewKazi Sajharul Islam 1410028630No ratings yet

- The Impact of Environmental Accounting and Reporting On Sustainable Development in NigeriaDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Environmental Accounting and Reporting On Sustainable Development in NigeriaSunny_BeredugoNo ratings yet

- New Perspectives On Corporate Reporting: Social-Economic and Environmental InformationDocument6 pagesNew Perspectives On Corporate Reporting: Social-Economic and Environmental InformationManiruzzaman ShesherNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument20 pagesRetrieveNada KhaledNo ratings yet

- Ecological FootprintDocument6 pagesEcological FootprintHope Gal0% (1)

- A Decade of Sustainability Reporting: Developments and SignificanceDocument14 pagesA Decade of Sustainability Reporting: Developments and SignificanceTawsif HasanNo ratings yet

- 11.vol 0003www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper No 2 PP 100-116Document18 pages11.vol 0003www - Iiste.org Call - For - Paper No 2 PP 100-116Alexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Green Information Technology: A Strategy To Become Socially Responsible Software OrganizationDocument17 pagesGreen Information Technology: A Strategy To Become Socially Responsible Software Organizationadmin2146No ratings yet

- SSRN-IfRS and SustainabilityDocument34 pagesSSRN-IfRS and SustainabilityVineet ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Carbon Accounting A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesCarbon Accounting A Systematic Literature Reviewc5e4jfpnNo ratings yet

- The Environmental Reporting Expectations Gap: Australian EvidenceDocument34 pagesThe Environmental Reporting Expectations Gap: Australian Evidencepepin fachrizaNo ratings yet

- 18Document6 pages18Tekaling NegashNo ratings yet

- Dua PDFDocument10 pagesDua PDFEwin KaroyaniNo ratings yet

- 13P PDFDocument25 pages13P PDFSagar Hossain SrabonNo ratings yet

- Addressing A Broad Scope SEA Research Agenda: Editorial NotesDocument4 pagesAddressing A Broad Scope SEA Research Agenda: Editorial NotesAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Azapagic and Perdan, 2000 - Indicators For SDDocument19 pagesAzapagic and Perdan, 2000 - Indicators For SDAdrian OblenaNo ratings yet

- NZMAC Full Paper PubDocument27 pagesNZMAC Full Paper PubEromina LilyNo ratings yet

- Event Study PaperDocument42 pagesEvent Study PaperRiazboniNo ratings yet

- Sustainability AccountingDocument13 pagesSustainability Accountingunitv onlineNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Environmental Disclosure: Department of Accounting, University of Benin, Nigeria. +234-8065074504Document10 pagesDeterminants of Environmental Disclosure: Department of Accounting, University of Benin, Nigeria. +234-8065074504Hasan BasriNo ratings yet

- Predominant Factors for Firms to Reduce Carbon EmissionsFrom EverandPredominant Factors for Firms to Reduce Carbon EmissionsNo ratings yet

- Empowering Green Initiatives with IT: A Strategy and Implementation GuideFrom EverandEmpowering Green Initiatives with IT: A Strategy and Implementation GuideNo ratings yet

- Table of Contents9jeyptunvj 1Document5 pagesTable of Contents9jeyptunvj 1A KyariNo ratings yet

- Godwin Okpe Technical Report Siwes-5: September 2022Document44 pagesGodwin Okpe Technical Report Siwes-5: September 2022A KyariNo ratings yet

- Yusuf Yarima 2Document11 pagesYusuf Yarima 2A KyariNo ratings yet

- ASLM-WPS OfficeDocument1 pageASLM-WPS OfficeA KyariNo ratings yet

- Chapter Thre To FiveDocument7 pagesChapter Thre To FiveA KyariNo ratings yet

- National Identity Management System: Federal Republic of NigeriaDocument1 pageNational Identity Management System: Federal Republic of NigeriaA Kyari100% (1)

- Special 2023Document1 pageSpecial 2023A KyariNo ratings yet

- Proposal SQDocument3 pagesProposal SQA KyariNo ratings yet

- Academic Calender-1Document1 pageAcademic Calender-1A KyariNo ratings yet

- 2021-2022 2&4 Sem Result C.E PDFDocument7 pages2021-2022 2&4 Sem Result C.E PDFA KyariNo ratings yet

- # NPC Id Full Name Date Creat Email Nin Phone Numlga QualificatiDocument20 pages# NPC Id Full Name Date Creat Email Nin Phone Numlga QualificatiA KyariNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTIONDocument19 pagesINTRODUCTIONA KyariNo ratings yet

- Transaction ReceiptDocument1 pageTransaction ReceiptA KyariNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument5 pagesUntitledA KyariNo ratings yet

- RTP Dec 18 AnsDocument36 pagesRTP Dec 18 AnsbinuNo ratings yet

- GPL NotesDocument11 pagesGPL NotesRyDNo ratings yet

- Strategy SsDocument8 pagesStrategy SsKaran HingmireNo ratings yet

- Math SBADocument28 pagesMath SBATiana ThomasNo ratings yet

- Munir Industry Exemption 2021 FBRDocument2 pagesMunir Industry Exemption 2021 FBRAqeel ZahidNo ratings yet

- Submittal For Approval of Materials Section 13967 - Clean-Agent Fire Extinguishing SystemsDocument1 pageSubmittal For Approval of Materials Section 13967 - Clean-Agent Fire Extinguishing SystemsFaruh IsmatovNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Chapter 2Document7 pagesTutorial Chapter 2ammar naimNo ratings yet

- Mayuri Bhogle - Black BookDocument44 pagesMayuri Bhogle - Black BookPooja AdhikariNo ratings yet

- History of Swot AnalysisDocument4 pagesHistory of Swot AnalysisAzeem Ali Shah100% (1)

- Nasscom Technology and Leadership Forum 2024 - ScheduleDocument4 pagesNasscom Technology and Leadership Forum 2024 - ScheduleRakesh ArukapalliNo ratings yet

- 5 - Sales and Service Cloud DatasheetDocument2 pages5 - Sales and Service Cloud Datasheetitsme.mahe263No ratings yet

- Siddu PDFDocument2 pagesSiddu PDFNikhil MohaneNo ratings yet

- @ Reading Comprehension Workshop On Technical Terms On Supply and Technical Terms On Supply and DemandDocument5 pages@ Reading Comprehension Workshop On Technical Terms On Supply and Technical Terms On Supply and Demandrafael santosNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1 Genpact Services LLC: FactsDocument10 pagesCase Study 1 Genpact Services LLC: FactsAmit GroverNo ratings yet

- Bio-Chemical Data of DR - Vijayan Gurumurthy Iyer - 21 ST December 2021Document176 pagesBio-Chemical Data of DR - Vijayan Gurumurthy Iyer - 21 ST December 2021Dr.Vijayan Gurumurthy IyerNo ratings yet

- How To Approach Reading Test Part OneDocument3 pagesHow To Approach Reading Test Part OneA DiomaNo ratings yet

- Costs - Concepts and ClassificationsDocument5 pagesCosts - Concepts and ClassificationsCarlo B CagampangNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Sustainability ReportingDocument25 pagesAn Introduction To Sustainability Reportingawe gyiNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: 1 Running Head: VRIO AnalysisDocument5 pagesThis Study Resource Was: 1 Running Head: VRIO AnalysisMustika ZakiahNo ratings yet

- Infiniti BenefitsDocument11 pagesInfiniti Benefitssu maiyahNo ratings yet

- End Term Question Paper - FDM - Term V Batch 2020-22Document2 pagesEnd Term Question Paper - FDM - Term V Batch 2020-22sumit rajNo ratings yet

- Kotler Pom17e PPT 19Document39 pagesKotler Pom17e PPT 19Hà Lê100% (1)

- Sample Cash Flow Projection TemplateDocument1 pageSample Cash Flow Projection TemplateAndraya BarthoNo ratings yet

- 1) Circulytics - Brochure ENGDocument5 pages1) Circulytics - Brochure ENGTeja Harjaya SamadhiNo ratings yet

- TFT Palm Oil Paper Number TwoDocument13 pagesTFT Palm Oil Paper Number TworachmathellyantoNo ratings yet

- SCA-528 - Iscala SSRS ReportsDocument42 pagesSCA-528 - Iscala SSRS ReportsIvan FaneiteNo ratings yet

- Peranggaran - #8 Anggaran OverHeadDocument40 pagesPeranggaran - #8 Anggaran OverHeadcitra kurniaNo ratings yet

- Court of Tax Appeals: VENUE: Second Division Courtroom, 3Document4 pagesCourt of Tax Appeals: VENUE: Second Division Courtroom, 304 pandaNo ratings yet

- Invoice 1Document1 pageInvoice 1zagher23No ratings yet