Professional Documents

Culture Documents

RSV Is Surging Among Kids - Here's What You Need To Know

RSV Is Surging Among Kids - Here's What You Need To Know

Uploaded by

Abdo Mohamed0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views5 pages- RSV cases are surging among children in the US, overwhelming hospitals, as the virus is a leading cause of childhood death worldwide.

- New monoclonal antibody treatments and vaccine candidates offer hope to prevent RSV infections, with a monoclonal antibody treatment possibly being approved by the end of 2022 and a maternal RSV vaccine filing for approval and potentially being available in 2023.

- RSV infects 64 million people annually and poses high risks for young children and older adults, but decades of attempts to develop a vaccine were unsuccessful until a recent breakthrough in stabilizing the viral fusion protein utilized by current leading vaccine candidates.

Original Description:

Original Title

Untitled

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document- RSV cases are surging among children in the US, overwhelming hospitals, as the virus is a leading cause of childhood death worldwide.

- New monoclonal antibody treatments and vaccine candidates offer hope to prevent RSV infections, with a monoclonal antibody treatment possibly being approved by the end of 2022 and a maternal RSV vaccine filing for approval and potentially being available in 2023.

- RSV infects 64 million people annually and poses high risks for young children and older adults, but decades of attempts to develop a vaccine were unsuccessful until a recent breakthrough in stabilizing the viral fusion protein utilized by current leading vaccine candidates.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views5 pagesRSV Is Surging Among Kids - Here's What You Need To Know

RSV Is Surging Among Kids - Here's What You Need To Know

Uploaded by

Abdo Mohamed- RSV cases are surging among children in the US, overwhelming hospitals, as the virus is a leading cause of childhood death worldwide.

- New monoclonal antibody treatments and vaccine candidates offer hope to prevent RSV infections, with a monoclonal antibody treatment possibly being approved by the end of 2022 and a maternal RSV vaccine filing for approval and potentially being available in 2023.

- RSV infects 64 million people annually and poses high risks for young children and older adults, but decades of attempts to develop a vaccine were unsuccessful until a recent breakthrough in stabilizing the viral fusion protein utilized by current leading vaccine candidates.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 5

RSV is surging among kids—

here's what you need to know

New antibody treatments and vaccine candidates promise long-

awaited relief from the respiratory virus that’s a leading cause

of childhood death worldwide.

In recent weeks, children’s hospitals across the United

States have raised the alarm that their beds have filled up

with young patients struggling to breathe and in dire need

of oxygen. This year, the culprit is not coronavirus but

respiratory syncytial virus—more commonly known as

RSV.

RSV is not a new pathogen. The virus infects some 64

million people a year worldwide. But it poses a

particularly high risk to adults over 65 and to children,

who are more likely to require hospitalization. Globally,

RSV causes about 160,000 deaths a year—including more

than 100,000 children under the age of five. Still, there

isn’t a vaccine for the disease or any treatments available

for general use.

But solutions are on the way. Experts say that

a monoclonal antibody treatment for RSV could be

approved by the end of the year, and a vaccine could be

rolled out in time for the 2023 RSV season. Pfizer said on

November 1 that its vaccine is 81 percent effective in an

infant's first 90 days of life and 69 percent effective

through the first six months of life. The company plans to

file for approval of its RSV vaccine candidate by the end

of 2022. (Why vaccines are critical to keeping diseases at

bay.)

“This could be a huge game changer globally,” says Keith

Klugman, director of the pneumonia program at the Bill &

Melinda Gates Foundation, which is funding Pfizer’s

maternal vaccine candidate.

Here’s what you need to know about RSV, why cases are

so high right now in the U.S., and why experts say these

new developments are so promising.

What is RSV?

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, RSV is a respiratory virus that primarily

spreads through coughing, sneezing, and other forms of

close contact. It’s also seasonal: In the U.S., RSV is at its

worst in the winter months. Anyone can catch or spread

RSV, but people with healthy immune systems tend to

suffer only mild cold-like symptoms.

Older adults with weakened immune systems have a

harder time staving off the virus—as do young children,

whose still-developing immune systems have never been

exposed to the pathogen. They are more likely to have

severe RSV infections, which can include symptoms such

as dehydration and difficulty breathing.

“RSV was unequivocally the most important cause of

serious respiratory disease in infants and young children”

before COVID-19 came along, says Kathleen Neuzil,

director of the University of Maryland School of

Medicine’s Center for Vaccine Development and Global

Health. Young children are also especially vulnerable

because their airways are narrow: Among children

younger than one, RSV is the leading cause of

bronchiolitis, the inflammation of airways in the lung.

Why are cases surging?

It’s not unusual for the U.S. to see this many cases in an

RSV season, but it is a bit unusual to see RSV surging so

early in the year. Neuzil suspects that COVID-19 is to

blame: “COVID-19 has really wreaked havoc on the

seasonality of our respiratory viruses,” she says. Now that

many people are no longer regularly wearing

masks, experts hypothesize that the viruses have begun

circulating out of season simply because people are more

vulnerable to infection after two years of not getting sick.

Neuzil says that it’s unclear whether this change is

permanent or whether RSV will ultimately revert to

its normal seasonal pattern, which begins as early as mid-

September but peaks from late December to mid-

February. It also remains to be seen whether the current

surge represents the peak of this year’s RSV season—or

whether the worst is yet to come.

Why don’t we already have an RSV vaccine?

Researchers have spent decades attempting to prevent

RSV deaths. But an effort to develop a vaccine in the

1960s was a colossal failure—sickening children rather

than protecting them.

Bill Gruber, senior vice president of vaccine clinical

research and development at Pfizer, says it was clear then

that the goal was to “attack the business end of the virus,”

or the protein that allows the virus to fuse with the

membrane of a human lung cell.

But the fundamental breakthrough came in 2013, Gruber

says, when scientists discovered they needed to stabilize

the viral protein used in the vaccine to keep it in its pre-

fusion form. That’s the idea behind most of the

treatments currently under development.

What new RSV treatments are in development?

The RSV treatment that’s furthest along in the pipeline

is Nirsevimab, a monoclonal antibody developed by

AstraZeneca. Given to infants by injection at birth or soon

after, Nirsevimab directly delivers RSV antibodies directly

to their bloodstreams, allowing their immune systems to

neutralize the virus and keep it from replicating.

In March, a study of the phase 3 clinical trial showed a 75

percent efficacy in protecting infants from lower

respiratory tract infections severe enough to require

medical care. In early October, the World Health

Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on

Immunization (SAGE) reviewed clinical trial data

and reported that regulatory authorization is “imminent.”

Neuzil—a member of SAGE and its RSV vaccine technical

advisory group—says it’s possible the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration could authorize the treatment by the end

of 2022.

How about RSV vaccines?

There’s a robust pipeline of RSV vaccine candidates in

development, Neuzil says. But the first that’s likely to

cross the finish line is Pfizer’s maternal vaccine, which is

designed for pregnant people. The idea behind this

vaccine is to protect babies before they’re even born by

vaccinating the mother who makes antibodies which then

pass to the fetus through the blood.

In April, a study of phase 2b clinical trials showed that

Pfizer’s vaccine produced a high level of

antibodies, earning it a Breakthrough Therapy

Designation from the FDA, meaning that the agency plans

to expedite the development and review of the vaccine.

On November 1, Pfizer said that the positive results of its

phase three trials mean that the company can now wrap

up the trials and file for regulatory approval. Klugman of

the Gates Foundation says that FDA approval could come

in 2023.

“This is something I’ve been looking forward to my whole

professional life,” Gruber says. “We are making the right

sort of antibody, so I think we are in a very good position

to be successful.”

Meanwhile top-line results from Pfizer’s phase three trials

among older adults showed an 85 percent efficacy. And a

slew of other RSV vaccine candidates are not far

behind. Some of these candidates contain adjuvants, or

substances that increase the immune response, which

Neuzil says are not ideal for use during pregnancy.

That’s great, but how can you protect people

now?

“It’s so exciting what we’re seeing with the new RSV

vaccines and the antibodies, but it’s not going to help the

babies this winter,” Neuzil says. She recommends that

people continue to take precautions like masking,

particularly if they spend time around newborns or older

people who are especially vulnerable to severe RSV.

“We’re getting close, but we won’t be there this year,” she

says. “So it’s really, really important to be very careful.”

You might also like

- Ninja Nerd AnemiaDocument13 pagesNinja Nerd AnemiaAndra Bauer100% (4)

- Concept Map Finished 2Document6 pagesConcept Map Finished 2api-352785497100% (1)

- Shots For This Fall and WinterDocument7 pagesShots For This Fall and WinterRosario Ordoñez NavaNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection and Bronchiolitis: Practice GapsDocument14 pagesRespiratory Syncytial Virus Infection and Bronchiolitis: Practice GapsAnge CerónNo ratings yet

- Should You Get The RSV VaccineDocument3 pagesShould You Get The RSV VaccineJaveriaNo ratings yet

- The Full Value of Immunisation Against Respiratory Syncytial Virus For Infants Younger Tha 1 YearDocument10 pagesThe Full Value of Immunisation Against Respiratory Syncytial Virus For Infants Younger Tha 1 Yearluis sanchezNo ratings yet

- Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics: News: Two Studies On Optimal Timing For Measles VaccinationDocument4 pagesHuman Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics: News: Two Studies On Optimal Timing For Measles VaccinationTri RachmadijantoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On RSVDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On RSVegtwfsaf100% (1)

- JNB 2 222Document13 pagesJNB 2 222Lars JayhawkNo ratings yet

- Delta VariantDocument4 pagesDelta VariantTAMILNo ratings yet

- A Hard Look at Mandatory Vaccines!!Document18 pagesA Hard Look at Mandatory Vaccines!!Guy Razer100% (3)

- P Zer Says It Needs To Study A Third Dose For Toddlers: Analysis byDocument9 pagesP Zer Says It Needs To Study A Third Dose For Toddlers: Analysis byAzv AzvNo ratings yet

- First Nasal Vaccine For COVID-19 (Coronavirus) and It Is Better Than Intramuscular Injection VaccineDocument3 pagesFirst Nasal Vaccine For COVID-19 (Coronavirus) and It Is Better Than Intramuscular Injection VaccinePrashant KumarNo ratings yet

- Accepted ManuscriptDocument19 pagesAccepted Manuscripthilman lesmanaNo ratings yet

- FDA's Contributions To Advancing New Technologies For Developing Safe and Effective Influenza VaccinesDocument9 pagesFDA's Contributions To Advancing New Technologies For Developing Safe and Effective Influenza VaccinessinhlyhocbiologyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Childhood VaccinesDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Childhood Vaccinesafnkjdhxlewftq100% (1)

- Zika y Embarazo 2016Document6 pagesZika y Embarazo 2016David VargasNo ratings yet

- ECPE-03-SI-0012 Covid 19Document3 pagesECPE-03-SI-0012 Covid 19ijklmnopqurstNo ratings yet

- Hiv in Pregnancy Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesHiv in Pregnancy Literature Reviewafmztwoalwbteq100% (1)

- The Educational Level and Vaccination Knowledge Among Parents in Dawadmi-Saudi Arabia, 2014Document10 pagesThe Educational Level and Vaccination Knowledge Among Parents in Dawadmi-Saudi Arabia, 2014ijasrjournalNo ratings yet

- Practical Research... Grounded TheoryDocument3 pagesPractical Research... Grounded TheoryParon MarNo ratings yet

- NCfIH Fast Facts Respiratory Syncytial VirusDocument6 pagesNCfIH Fast Facts Respiratory Syncytial VirusIndiana Family to FamilyNo ratings yet

- Ongoing National Dengue EpidemicDocument3 pagesOngoing National Dengue EpidemicEvan Siano BautistaNo ratings yet

- Health Science Reports - 2023 - Abbasi - Revitalizing Hope For Older Adults The Use of The Novel Arexvy For ImmunizationDocument3 pagesHealth Science Reports - 2023 - Abbasi - Revitalizing Hope For Older Adults The Use of The Novel Arexvy For Immunizationhalfani.solihNo ratings yet

- BronquiolitisDocument6 pagesBronquiolitisIliana GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Vaksin VarelaDocument8 pagesVaksin VarelaPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- Breakinglink 1Document3 pagesBreakinglink 1api-309603546No ratings yet

- Why Do Some People Not Get Covid - They May Hold Key To Beating The Virus - BloombergDocument4 pagesWhy Do Some People Not Get Covid - They May Hold Key To Beating The Virus - BloombergHansley Templeton CookNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay VaccineDocument2 pagesArgumentative Essay VaccineivyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Childhood VaccinationsDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Childhood Vaccinationsefjr9yx3100% (1)

- Examen Reading 1 - JunioDocument13 pagesExamen Reading 1 - JunioJuan MontufarNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Acceptance of Covid 19 Vaccine Among Nursing Students in Riverside CollegeDocument2 pagesKnowledge and Acceptance of Covid 19 Vaccine Among Nursing Students in Riverside CollegeGLORYLYN ECHOGANo ratings yet

- Part II - The Myth That Vaccination Equals ImmunizationDocument18 pagesPart II - The Myth That Vaccination Equals ImmunizationGary Null100% (4)

- Vacunas C-19Document4 pagesVacunas C-19Annuated DémodéNo ratings yet

- SRH Case Study 1 - RSVDocument7 pagesSRH Case Study 1 - RSVapi-721737872No ratings yet

- Local Studies and LiteratureDocument9 pagesLocal Studies and LiteratureKarl GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Flu Vaccine-Related Miscarriages May Outnumber Swin Flu Deaths by Gary Null, Ph.D.Document4 pagesFlu Vaccine-Related Miscarriages May Outnumber Swin Flu Deaths by Gary Null, Ph.D.Gary Null100% (1)

- Influenza vaccination: What does the scientific proof say?: Could it be more harmful than useful to vaccinate indiscriminately elderly people, pregnant women, children and health workers?From EverandInfluenza vaccination: What does the scientific proof say?: Could it be more harmful than useful to vaccinate indiscriminately elderly people, pregnant women, children and health workers?No ratings yet

- It Feels Yucky Pediatricians Say Theyre Discarding Vaccine Doses For The Youngest Amid Lack of DemandDocument4 pagesIt Feels Yucky Pediatricians Say Theyre Discarding Vaccine Doses For The Youngest Amid Lack of DemandJohn SmithNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pediatric Research Ijpr 9 112Document12 pagesInternational Journal of Pediatric Research Ijpr 9 112VsbshNo ratings yet

- The Safety of Influenza Vaccines in Children An Institute For Vaccine Safety White PaperDocument67 pagesThe Safety of Influenza Vaccines in Children An Institute For Vaccine Safety White Papermaheshmuralinair6No ratings yet

- CDC 57181 DS1Document17 pagesCDC 57181 DS1She KNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of ChickenpoxDocument8 pagesLiterature Review of Chickenpoxfv55wmg4100% (1)

- Proposal For Long Term COVID 19 Control - v1.0Document16 pagesProposal For Long Term COVID 19 Control - v1.0bathmayentoopagenNo ratings yet

- A Vaccine For MalariaDocument2 pagesA Vaccine For MalariaArcciPradessatamaNo ratings yet

- 2010 31 129 Jan E. Drutz: Pediatrics in ReviewDocument4 pages2010 31 129 Jan E. Drutz: Pediatrics in Reviewsayoku tenshiNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Preference of Philippines Position PaperDocument3 pagesVaccination Preference of Philippines Position PaperJuan Leandro MaglonzoNo ratings yet

- Jama Scruggswodkowski 2024 It 240013 1716391958.78925Document2 pagesJama Scruggswodkowski 2024 It 240013 1716391958.78925ANDREA CABRERA de MARTINEZNo ratings yet

- (R) Varicella VirusDocument8 pages(R) Varicella VirusEkkim Al KindiNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Pulmonology - 2023 - 58 - 631-1639.Document9 pagesPediatric Pulmonology - 2023 - 58 - 631-1639.HemerobibliotecaHospitalNo ratings yet

- Influenza A H1N1 Press Transcript 01 05 2009Document2 pagesInfluenza A H1N1 Press Transcript 01 05 2009Juergen BirkinNo ratings yet

- Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Effectiveness by Age at Vaccination A Systematic ReviewDocument20 pagesHuman Papillomavirus Vaccine Effectiveness by Age at Vaccination A Systematic ReviewdeasyarchikaalvaresNo ratings yet

- Herpes Virus Research PaperDocument6 pagesHerpes Virus Research Papergpwrbbbkf100% (1)

- First Line FluDocument6 pagesFirst Line Flu419022 MELA ANANDA PUTRIANANo ratings yet

- 1603938926TOEFL Ibt Full Length Test 2Document27 pages1603938926TOEFL Ibt Full Length Test 2Hà NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Incidence of Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus.14Document5 pagesIncidence of Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus.14henkNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Childhood ImmunizationDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Childhood Immunizationc5e4jfpn100% (1)

- Nejm VaricellaDocument9 pagesNejm VaricellaadityailhamNo ratings yet

- Are Vaccines SafeDocument3 pagesAre Vaccines SafeJun Kai Ong100% (1)

- Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Children: Myths and FactsDocument4 pagesCommunity-Acquired Pneumonia in Children: Myths and FactsFranciscoDelgadoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal InfeksiDocument10 pagesJurnal InfeksiIkhsan AliNo ratings yet

- Translation 6Document7 pagesTranslation 6Abdo MohamedNo ratings yet

- Here Are The Countries That Have Bans On TiktokDocument5 pagesHere Are The Countries That Have Bans On TiktokAbdo MohamedNo ratings yet

- FiscalDocument15 pagesFiscalAbdo MohamedNo ratings yet

- Terminology Part 1Document3 pagesTerminology Part 1Abdo MohamedNo ratings yet

- Election Platform/manifesto/programmeDocument1 pageElection Platform/manifesto/programmeAbdo MohamedNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument15 pagesUntitledAbdo MohamedNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledAbdo MohamedNo ratings yet

- Dealing With Postpartum DepressionDocument5 pagesDealing With Postpartum DepressionAngela SimbulanNo ratings yet

- Jcem 0709Document20 pagesJcem 0709Rao Rizwan ShakoorNo ratings yet

- Gestational Hypertension - UpToDateDocument16 pagesGestational Hypertension - UpToDateNestor FloresNo ratings yet

- "Iligtas Sa Tigdas Ang Pinas ": Guide For Vaccination TeamDocument24 pages"Iligtas Sa Tigdas Ang Pinas ": Guide For Vaccination Teamkbl27No ratings yet

- Nejme 2400102Document3 pagesNejme 2400102linjingwang912No ratings yet

- ManiaDocument10 pagesManiaaashvi dalalNo ratings yet

- Kuliah Pakar Anemia in Pregnancy Dr. Ima IndirayaniDocument74 pagesKuliah Pakar Anemia in Pregnancy Dr. Ima IndirayaniHamba AllahNo ratings yet

- Dog and Cat Health SecretsDocument70 pagesDog and Cat Health SecretsIvana Dasović100% (1)

- Complete ROS and PEDocument6 pagesComplete ROS and PEJulienneNo ratings yet

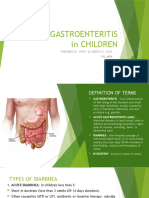

- Acute Gastroenteritis in Children: Prepared By: Prof. Elizabeth D. Cruz RN, ManDocument12 pagesAcute Gastroenteritis in Children: Prepared By: Prof. Elizabeth D. Cruz RN, ManChaii De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Newborn ReflexesDocument7 pagesNewborn ReflexesAngel Mae Alsua100% (1)

- Disease Diagnosis System: Software Requirement Specification (SRS)Document11 pagesDisease Diagnosis System: Software Requirement Specification (SRS)Shubham BhadauriaNo ratings yet

- Primary and Secondary LesionsDocument2 pagesPrimary and Secondary LesionsGaram Esther GohNo ratings yet

- Granuloma AnnulareDocument6 pagesGranuloma AnnulareGitarefinaNo ratings yet

- CDC Org ChartDocument1 pageCDC Org Chartwelcome martinNo ratings yet

- Eficácia Das Lactonas Macrocíclicas Sistêmicas (Ivermectina e Moxidectina) Na Terapia Da Demodicidose Canina GeneralizadaDocument8 pagesEficácia Das Lactonas Macrocíclicas Sistêmicas (Ivermectina e Moxidectina) Na Terapia Da Demodicidose Canina GeneralizadaStéfano Celis ConsiglieriNo ratings yet

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) : Gözde İnan, MD Kutluk Pampal, MDDocument60 pagesCardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) : Gözde İnan, MD Kutluk Pampal, MDSarper Hikmet TAZENo ratings yet

- Gram Negative RodsDocument8 pagesGram Negative RodsRuel Maddawin100% (1)

- Lippincotts Antiarrhythmics 5Document1 pageLippincotts Antiarrhythmics 5Wijdan HatemNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Exemption Pursuant To Wisconsin Statute 252.04Document2 pagesVaccination Exemption Pursuant To Wisconsin Statute 252.04DonnaNo ratings yet

- Throat Pharynx Palatine Tonsils ENT LecturesDocument45 pagesThroat Pharynx Palatine Tonsils ENT Lecturessankarsuper83No ratings yet

- ALU 101 Sample QuestionsDocument4 pagesALU 101 Sample Questionsartlover30No ratings yet

- PNEUMONIADocument13 pagesPNEUMONIAshenecajean carajay100% (1)

- Degenerate FibroidDocument3 pagesDegenerate FibroidYuuki Chitose (tai-kun)No ratings yet

- Bactrim AdverseDocument5 pagesBactrim Adversevictoriab5No ratings yet

- Oak Tree Union Colored Cemetery of TaylorvilleDocument14 pagesOak Tree Union Colored Cemetery of TaylorvilleWFTVNo ratings yet

- Medical CertificateDocument1 pageMedical CertificateAyesha WasimNo ratings yet

- UtiDocument28 pagesUtiDrShweta SainiNo ratings yet