Professional Documents

Culture Documents

13-Article Text-458-1-10-20230307 PDF

13-Article Text-458-1-10-20230307 PDF

Uploaded by

Andreia SilvaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

13-Article Text-458-1-10-20230307 PDF

13-Article Text-458-1-10-20230307 PDF

Uploaded by

Andreia SilvaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology 166

2023, Vol 1, Issue 1, 166-174

https://doi.org/10.55913/joep.v1i1.13

Maintaining Well-Being During the COVID-19

Pandemic: A Network Analysis of Well-Being

Responses from British Youth

Alison F. W. Wu1, Deniz Konac1, Laura Riddleston1, Taryn Hutchinson1, Belinda Platt2,

Victoria Pile, Jennifer Y. F. Lau*3

1

Kings College London, 1Department of Psychology, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, UK

2

Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and

Psychotherapy, Germany

3

Queen Mary University of London, Centre of Primary Care and Mental Health, Institute of Population Health

Science, UK

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Abstract

COVID-19 has significant impacts on young peoples’ lives and emotions. Understanding how young people

maintain well-being in the face of challenges can inform future mental health intervention development. Here we

applied network analysis to well-being data gathered from 2532 young people (12-25 years) residing in the UK

during the COVID-19 pandemic to identify the structure across well-being and crucially, its central defining

features. Gender and age differences in networks were also investigated. Across all participants, items emerged

in two clusters: 1) optimism, positive self-perception, and social connectedness, and 2) processing problems and

ideas. The two central features of well-being were: “I’ve been dealing with problems well” and “I’ve been thinking

clearly”. There were minimal age and gender differences. Our findings suggest that the perception of being able

to process problems and ideas efficiently could be a hallmark of well-being, particularly in the face of challenging

circumstances. These findings contrast with pre-pandemic studies that point to positive affect as central aspects

of well-being networks. Future interventions that encourage problem-solving and mental flexibility could be

useful in helping young people maintain well-being during times of stress and uncertainty.

Keywords well-being; young people; COVID-19; network analysis; resilience; coping

__________________________________________________________________________________________

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to pose multiple academic achievement, positive interpersonal

challenges, adding to levels of stress globally (Serafini relationships) (Saxena et al., 2006). Identifying how

et al., 2020). Young people may be especially young people maintain well-being despite the

susceptible to the long-term impact of stress, given that challenges and stressors associated with the pandemic

youth reflects a period when many mental illnesses could inform the development of future universal

emerge, consolidate and become chronic (Paus et al., programs designed to promote positive mental health.

2008; Romeo, 2013). Identifying those reporting poor This information can be used to guide countries during

mental health and intervening early to attenuate this pandemic but can also be used more generally in

negative outcomes is a priority. However, from a population-based resilience programs post-pandemic.

public health preventative perspective it is also crucial Here, we used a network approach to identify the core

to promote positive outcomes at the population level, features of well-being in adolescents and young adults

such as good mental well-being. Mental well-being is (12-25 years) in the UK across various lockdown

the positive aspect of mental health (2001) and is phases of the pandemic.

known to protect against long-term mental health “Well-being” refers to the capacity to flourish

problems, for example, by reducing emotional distress under “normal” circumstances as well as the ability to

and increasing exposure to protective factors (e.g. be resilient and recover from challenging

__________________________________________________________________________________________

*Corresponding Author: Jennifer Y. F. Lau j.lau@qmul.ac.uk

Received: 14 Sep 2021 | Revision Received: 25 Jan 2022 | Accepted: 26 Jan 2022

Handling Editor: David A. Preece

Published by Black Swan Psychological Assessments Pty Ltd

ISSN 2653-7583 | www.emotionandpsychopathology.org

Wu et al. 167

circumstances (Galderisi et al., 2015). Well-being is being Scale (Bartram et al., 2013; Tennant et al., 2007),

often divided into two behavioural dimensions: we expected that items will cluster in terms of affective

affective (“feeling good”) and functional (“functioning and functioning dimensions of well-being. Tentatively,

well”) (Vittersø, 2013). Latent variable approaches to we hypothesised that positive affect would emerge as a

youth well-being have identified several higher-order central item, given pre-pandemic network findings.

(latent) factors e.g. positive affect and optimism, However, as the core features of well-being may vary

positive self-perceptions, the ability to process, engage during times of stress, other items may also emerge as

and persevere with tasks and problems, and social central features. We also compared whether centrality

connectedness (Arslan & Coşkun, 2020; Kern et al., and clustering parameters would vary across males and

2016). These distinct factors purportedly capture females and across adolescents (12-18 years) and

common variance across well-being items. However, young adults (19-25 years). Based on minimal gender

these approaches, while recognising that items form differences in the previous UK study (Stochl et al.,

clusters together, can be limited in their explanatory 2019), we expected no differences in findings between

power, by failing to capture all possible interactions or males and females. Although neither the UK (Stochl et

paths between items, missing out on quantifying any al., 2019) nor the China study (Zeng et al., 2019)

causal, mutually reinforcing effects. By specifying explicitly explored age differences, prior (non-

direct links (“edges”) between all items (“nodes”), network) studies suggest that there may be mean level

network analysis can also quantify how influential differences between adolescents’ and young adults’

(“central”) items are, by their capacity to activate or be deployment of specific coping strategies (Skinner &

activated by other items (Costantini et al., 2015). As Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007). How this translates to which

central items are more influential, it has been argued items are the most central feature of well-being is

that they reflect more optimal targets for intervention unknown.

(Fried et al., 2017).

To our knowledge, there have been two studies that Method

have analysed the network structure of well-being

items, both conducted before the pandemic. The first Participants and Procedure

study included data across 4 large population-based The study was approved by the Psychiatry, Nursing

cohorts (Stochl et al., 2019). Of these, one cohort and Midwifery Research Ethics Committee at Kings

comprised adolescents and young adults (14-25 year College London (ref: HR-19/20-18868). Anyone aged

olds) and one involved adolescents only (12-16 year between 12 and 25 residing in the UK at the time of

olds). On the whole, findings across all 4 cohorts were data collection in the UK was eligible to take part.

similar, suggesting minimal age differences. There Participants were recruited via several methods:

were also minimal gender differences. Across all advertising within UK schools, colleges and

participants, positive self-perception and positive Universities, research advertisement websites, social

affect emerged as the key features (central items) of media and charities. All participants aged 16 or over

well-being. The second study was conducted only in provided informed consent. For participants under 16,

children and young people from China (aged 6-18 informed assent/consent was provided by participants

years) (Zeng et al., 2019); a partial replication of the and their parent/guardian respectively. The study was

earlier UK findings by Stochl et al. was reported. set up in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic,

Although positive affect and optimism emerged as utilising an online survey to understand and monitor

being central to youth well-being, engagement was also the emotional impact of the pandemic in young people.

a key feature. While informative regarding well-being Data collection began on 12th May 2020 and ended on

in general, neither datasets inform a second aspect of 2nd December 2020. The study, which consisted of a

well-being: the ability to be resilient and recover from battery of measures including well-being, negative

more challenging circumstances. affect, anhedonia, loneliness, boredom, worries, and

In the present study, we applied network analysis to coping strategies was administered through the online

well-being data collected from young people (12-25 platform, Qualtrics. Participants were offered vouchers

years) during the COVID-19 pandemic from May to for their time spent taking part in this and subsequent

December 2020. Our primary interest was to inform follow-up surveys. 4872 respondents clicked on the

interventions to mitigate the damaging emotional survey link. Respondents were removed from the data

impact of COVID-19 on young peoples’ mental health if they: 1) did not complete any survey measures other

but these data are also crucial to post-pandemic than initial demographic information (n=1932); 2)

positive mental health or resilience interventions too. were duplicate responses (n=33); 3) did not meet age

We investigated how well-being items clustered and criteria (n=13); 4) had a survey completion time <5

which items were most central in all participants. Given minutes (n=41); 5) were not in the UK (n=48); 5)

we used the (short) Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well- showed other evidence of careless /inauthentic

Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology

Wu et al. 168

responding (n=245); or 6) had missing data on key Second, centrality indices representing the degree to

variables for this analysis (n=28). This allowed which a node influences or can be influenced by other

N=2532 for the final analysis. nodes were estimated for each item. We focused on two

centrality indices: strength and closeness (Newman,

Measures 2010) as these were stable in the present analysis.

Demographic Information. We measured Strength suggests how strongly and frequently a node

participants’ age, gender, ethnicity (using response is directly associated (has edges) with other nodes.

options that corresponded to ONS-recommended Closeness is indexed by the lengths of paths from any

harmonised country-specific questions for England, one node in the network to itself and calculated by the

Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland), educational inverse sum of distances of the focal node to all other

level, socioeconomic status (SES; indexed by highest nodes based on their shortest paths (Costantini et al.,

qualification obtained by either parent), and country of 2015). Betweenness is the number of shortest paths

current residence. passing through a specific node (Costantini et al.,

Warwick – Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale 2015), but as the index was not reliably estimated from

(WEMWBS). Given practical considerations of the current dataset, it was not presented here. Third, the

administering several online measures to young communities within the networks were detected using

people, the short-version of the WEMWBS was used. the Louvain algorithm (Rubinov & Sporns, 2011) on

Consisting of 7 items, this scale captures the concept of edge weights, which identifies nodes that cluster

well-being as reflecting functional and affective together. The Louvain algorithm optimises modularity,

aspects (although more items relate to functioning) and defined as the comparison between the edges’ density

is robust and valid in community youth settings of a community/cluster and edges’ density outside this

(Bartram et al., 2013; Tennant et al., 2007). Each item community/cluster, through moving each node to

is rated between 1 (none of the time) and 5 (all of the different communities/clusters (Blondel et al., 2008).

time). This algorithm has been used in previous studies and

shown good performance (Miers et al., 2020). Finally,

Analysis to explore gender and age group differences, network

Network analysis quantifies links (“edges”) between comparisons across genders and age groups (12-18 and

observed items (“nodes”) of a measure; thus it informs 19-25) were conducted. 18 years was selected as the

the overall structure of items, clusters (“communities”) cut-off because it reflected the median value within our

of items, and items that are more connected (“central”) age range. Network comparison analyses with

(Costantini et al., 2015). All analyses were performed Bonferroni correction were conducted on the global

by various packages within the statistical software, R, strength of the networks, which is the total sum of all

version 1.2.5033-1(Team, 2013): “qgraph version edge weights (partial Spearman correlations) and

1.6.5” (Epskamp et al., 2012), “bootnet version 1.4.3” reflects how tightly linked the entire network is, and on

(Epskamp et al., 2018)“NetworkComparisonTest the centrality indices, across the different groupings

version 2.2.1” (van Borkulo et al., 2016) and with 5000 iterations.

“NetworkToolbox version 1.4.0” (Christensen, 2018). To mitigate against any potential sample size

The Gaussian graphical model (GGM, (Costantini et limitations, we applied bootstrapping procedures to

al., 2015)), an undirected weighted network, was enhance the reliability of network parameters

estimated based on partial Spearman correlations (Epskamp et al., 2018). 95% confidence intervals (CI)

between observed variables. To infer the of edge weights were obtained through a bootstrapping

characteristics of interest (i.e. relationships between method, involving repeatedly estimating a model under

nodes, clusters among nodes, the most central items), sampled data and the statistic of interest (Team, 2013).

we evaluated the network structure using measures To investigate the stability of centrality indices,

taken from graph theory (Müller et al., 2012). When correlation stability (CS) coefficients were calculated

estimating the GGM, we employed GLASSO by case dropping bootstrap methods. Here, the

regularisation (“graphical least absolute shrinkage and centrality measures are recalculated for different sub-

selection operator”, (Tibshirani, 1996) to ensure the portions of the data after dropping a random percentage

sparsity (fewer edges) of the model with the Extended of cases. The CS coefficient is defined as the amount

Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC, (Chen & Chen, of cases that can be dropped while still maintaining a

2008)) to select the best-fitting model. high correlation (higher than .7) with the original

These analyses yielded 4 sets of information. First, centrality estimate (Epskamp et al., 2018). This

while GGMs were estimated and plotted for all coefficient should not drop below 0.25 and ideally be

participants (and for each subgroup), the accuracy of above 0.5 to justify robust interpretation of centrality

edge weights was also evaluated. This step allowed for indices.

the assessment of the overall network structures.

Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology

Wu et al. 169

Results Of note, additional analyses on age-matched groups

were similar to the unmatched groups with no gender

Participant Characteristics differences in overall global strength, clusters and

The mean age of participants was 18.4 (SD 3.6), and centrality analysis.

there were more females (70.1%) than males (29.9%).

Proportions of individuals in different ethnic groups Age Differences of Well-Being Networks

was as follows: 62.6% White/Caucasian, 8.2% The network comparison test showed no significant

Mixed/multiple ethnic groups, 20.6% Asian/Asian global network strength difference between groups, p

British, 4.1% Black/African/Caribbean, 2.4% other = .3. Both age groups showed the same two clusters as

ethnicities, and 2.1% prefer not to say. In terms of those of the whole group network (Figure 1c).

parental educational level, 2.9% reported parents with Centrality indices (i.e. strength and closeness) were

primary level qualifications, 13.4% with GCSE or stable in both age groups (Table 1). Items 4 and 5 had

equivalent, 18.7% with A level or equivalent, 39.5% the highest strength in both groups. In terms of

with Higher level degree or equivalent, 19% with closeness, item 5 (“I’ve been thinking clearly”) had the

Masters and 6.4% with PhD. highest closeness in the adolescent group (12-18 years)

The female group was older than the male group whereas in young adults (19-25 years), item 4 (“I’ve

(Mean(SD)male = 17.6 (3.6), Mean(SD)female = 18.7 been dealing with problems well”) had the highest

(3.6), t(2531) = 7.21, p < .001, d = .31, CI [0.81, 1.41]). closeness.

There were also more males in the adolescent age Of note, due to differences in the proportion of

group compared to the young adult age group (male males to females across age groups, we repeated

ratioadolescence = 35.1%, male ratioadult = 22.1%, c2 analyses with gender-matched groups, which yielded

=48.91, p < .001). similar results to unmatched groups.

Network Structure Across all Participants Discussion

The estimated network of 7 items represented as nodes

is presented in Figure 1a, where thicker lines reflect The outbreak of COVID19 and government measures

stronger partial correlations between items and all to mitigate infection rates have meant new daily

items are positively correlated. Two clusters were routines for many young people (changes in

identified. The first cluster comprised 3 items: item 1 educational, occupational, social and recreational

(“I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future”), item 2 activities), uncertainties over the physical health and

(“I’ve been feeling useful”) and item 6 (“I’ve been morbidity of themselves, family

feeling close to other people”). The second cluster members/friends/acquaintances, and wider society, and

consisted of the remaining items: item 3 (“I’ve been an exacerbation over any existing stressors (e.g. family

feeling relaxed”), item 4 (“I’ve been dealing with dynamics, over-crowded housing) (Janssen et al.,

problems well”), item 5 (“I’ve been thinking clearly”) 2020). As well-being can protect against future distress

and item 7 (“I’ve been able to make up my own mind and mental health problems (Saxena et al., 2006),

about things”). The centrality analysis showed items 4 understanding how individuals maintain well-being in

and 5 had the highest standardised strength and the face of these challenges at a developmental juncture

closeness, each estimated with high stability (CS- typically associated with the emergence of persistent

coefficient values for strength and closeness were both lifelong psychiatric symptoms (Paus et al., 2008) is

0.75, see Table 1). important for prevention. Although sparse, pre-

pandemic data (Stochl et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2019)

Gender Differences of Well-Being Networks are consistent in showing that experiences of positive

There were no significant differences in overall global affect (e.g. feeling cheerful) are at the centre of well-

strength in the networks of males and females, p = .48. being networks, and that this is true across genders and

Both male and female group networks clustered in the across ages (children, young people, adults). Our

same way as those of the whole sample (Figure 1b). findings taken during the pandemic revealed a different

Centrality analyses (i.e. strength and closeness) set of key features, which related to functional aspects

showed that items 4 and 5 had the highest strength and of well-being, notably, processing problems and ideas

closeness across both males and females, resembling (i.e. “I’ve been dealing with problems well” and “I’ve

that across all participants. Strength indices were been thinking clearly”). Well-being items could be

mostly stable in both gender groups (see Table 1) but differentiated into two distinct clusters. The first

the CS-coefficients for closeness in males showed only included items about optimism, positive self-

acceptable stability (CS-coefficient = .44), suggesting perception, and social connectedness, while the second

caution when interpreting male-only results. broadly related to processing problems/ideas.

Consistent with a previous UK study, we found no

Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology

Wu et al. 170

Table 1. Correlation stability coefficients of networks for all participants, each gender group and each age

group.

n Strength Closeness

All 2532 0.75 0.75

Gender

male 757 0.75 0.44

female 1775 0.75 0.67

Age

Adolescents 1517 0.75 0.67

Young adults 1015 0.75 0.36

gender differences in global network strength, clusters specifically to stress and uncertainty by thinking

and central items but subtle age differences on central clearly and problem-solving appear to be important.

items only were found. There were no age differences Future studies may wish to differentiate whether it is

in items reflecting the highest strength; that is, both objective abilities or simply the perception of being

clear thinking and problem-solving were equally able to think clearly and problem-solve that is

strongly associated with other items across adolescents important to resilience.

and young adults. In terms of closeness (how quickly Nonetheless, these findings suggest that therapeutic

an item can affect other items or be affected by other techniques encouraging problem-solving and thinking

items), clear thinking had the highest closeness index more clearly (or nurturing the perception of these

in adolescents (12-18 years) but problem-solving cognitive capacities) could nurture resilient outcomes

emerged as being closest to other items in young adults to challenging situations. These findings are useful for

(19-25 years). Each of these findings are discussed. dealing with stressful life events more generally.

Although direct comparisons between our study However, these skills need to be directed at problems

findings and the two previous studies are somewhat that are carefully selected, not just for personal salience

constrained by the use of different well-being but are also within control and achievable. While our

measures, developmental differences (with the UK findings suggest that such interventions may be

study, (Stochl et al., 2019)) and cultural differences applicable to males and females, somewhat different

(with the Chinese study, (Zeng et al., 2019)), intervention targets could benefit adolescents and

nonetheless, the broad pattern of findings around young adults. Adolescents who are struggling may

central items is different between those collected pre- benefit more from instruction around thinking clearly

pandemic and ours collected during lockdown – a time (sustained, flexibly, being able to ignore distractors),

of stress and uncertainty. While both pre-pandemic while struggling young adults could be more receptive

studies identified positive mood as a key feature of to guidance over solving the problems that they are

well-being, pandemic data indicated that a functional facing.

aspect of well-being, notably processing problems and Beyond findings on the centrality of items, our data

ideas, became more prominent. In network analyses, also shed light on the network structure of items during

being prominent means that these items have more the pandemic. In network analysis, clusters within

strong connections with other items. Once activated, networks may not necessarily suggest that these items

these items may also be likely to quickly influence have conceptual equivalence, as they perhaps do in

other items and be quickly influenced in turn. Within factor analysis. Instead, clusters point to more dense

the concept of well-being, this suggests that under patterns of inter-connection or co-activation within a

conditions of stress and uncertainty, being able to subset of items. We identified two clusters. The first

problem-solve and think clearly could impact other pertained to items mapping onto the affective aspects

affective aspects of well-being including optimism, of well-being: optimism, positive self-perception and

positive self-perception and feeling connected to connectedness with others while the second cluster

others. That these findings differ from pre-pandemic mapped more onto functional aspects of well-being,

findings suggests that the emotional challenges posed specifically, cognitive-processing of problems, ideas

by the pandemic requires more than the experience of and decisions. At first glance, the items of the first

positive affect to maintain well-being. Indeed, being cluster appear more heterogeneous, but given the

able to manage and control feelings that emerge restrictions, changes and uncertainty of the pandemic,

Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology

Wu et al. 171

Figure 1. Network clusters of well-being items for: a) all participants; b) two gender groups,

and c) two age groups.

Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology

Wu et al. 172

may have been re-defined together because they are all sample had higher SES, contained a lower proportion

more difficult to achieve. Yet, their differentiation of participants describing themselves as belonging to a

from processing problems and ideas are also somewhat White ethnic group, and a higher proportion belonging

consistent with previous research. For example, Stohl to a minority ethnic group (Office for National

and colleagues reported that items around processing Statistics, 2018).

problems and ideas were highly related but distinct In closing, our findings suggest that the perception

from items of self-perception (which were themselves of being able to process problems and ideas efficiently

highly related), and from items of relationships with could be a hallmark of well-being, particularly in the

others (again highly related to each other). Although face of challenging circumstances. Tentatively,

feeling relaxed also feels more “affective” in nature developing interventions that encourage (perceptions

compared to the more “cognitive” aspects of the second of or actual) problem-solving and mental flexibility

cluster, it may be that it co-activates with these items could be useful in helping young people maintain well-

more because feeling relaxed is important for cognitive being during times of stress and uncertainty, either

processing such as thinking clearly, decision-making during later phases of the pandemic or even post-

and problem-solving, an association that is especially pandemic.

evident during mindfulness meditation (Jay Lynn et al.,

2006; Tarrasch, 2015). Additional Information

There are some study limitations. First, as we used

a different measure to previous studies, our findings are

Supplementary Materials

not directly comparable. Specifically, we used the 7- Supporting information includes network analysis

item Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale

results (centrality graphs and bootstrapping results for

(WEMWBS), whereas the previous study of British all participants, see FigS1, gender groups, see FigS2,

sample used the 14-item version and the study and age groups, see FigS3) and R code for network

involving Chinese adolescents used the 20-item

analysis and comparison, see SRcode.docx.

Chinese version of Engagement, Perseverance, Supplementary materials for this article can be viewed

Optimism, Connectedness, and Happiness scale

here: https://osf.io/4s76g/

(EPOCH). The 7-item scale we used contains fewer

affective well-being items compared to the 14-item Funding

scale, and the WEMWBS considers two behavioural This work was supported by the Rosetrees Trust

dimensions of well-being rather than the more in-depth (M949).

EPOCH, which measures five clusters of well-being.

Differences between these measures (and their Conflict of Interest

underlying constructs) means it is difficult to attribute

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors

discrepancies between findings to differences in alone are responsible for the content and writing of the

environmental circumstances (pre and during the paper.

pandemic). Another concern about measurement is our

reliance on self-reported items only; this means that for Ethical Approval

some of the key features of well-being reflect

This study was approved by the research ethics

perceptions rather than objective capacity to use these committee of King’s College London (reference: HR-

skills. Second, because it is challenging to incorporate 19/20-18250)

continuous age differences as a moderator into network

analysis, to assess age differences we divided the Data Availability

sample into those above and below the median value.

Data and study materials are available upon request.

18 years was the median in our sample, however, it is

also a transitional juncture where some 18 year olds Copyright

have begun University and others are still in secondary The authors licence this article under the terms of the

school, adding to the heterogeneity of the adolescent Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence.

sample. Third, not all young people experienced the

© 2023

COVID-lockdown to the same degree of impact; some

may have experienced greater bereavements, different

levels of restrictions with varied lockdown rules and References

tiers occurring in different geographic locations.

Finally, our sample may not be representative of the Arslan, G., & Coşkun, M. (2020). Student subjective

UK population in terms of SES (based on parental wellbeing, school functioning, and psychological

educational qualifications) and ethnicity. Compared to adjustment in high school adolescents: A latent

reports from the Office for National Statistics, our variable analysis. Journal of Positive School

Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology

Wu et al. 173

Psychology, 4(2), 153-164. Jay Lynn, S., Surya Das, L., Hallquist, M. N., &

doi:https://doi.org/10.47602/jpsp.v4i2.231 Williams, J. C. (2006). Mindfulness, acceptance,

Bartram, D. J., Sinclair, J. M., & Baldwin, D. S. and hypnosis: Cognitive and clinical perspectives.

(2013). Further validation of the Warwick- International Journal of Clinical and

Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) Experimental Hypnosis, 54(2), 143-166.

in the UK veterinary profession: Rasch analysis. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00207140500528240

Quality of Life Research, 22(2), 379-391. Kern, M. L., Benson, L., Steinberg, E. A., &

doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0144-4 Steinberg, L. (2016). The EPOCH measure of

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & adolescent well-being. Psychological assessment,

Lefebvre, E. (2008). Fast unfolding of 28(5), 586.

communities in large networks. Journal of doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000201

statistical mechanics: theory and experiment, Miers, A. C., Weeda, W. D., Blöte, A. W., Cramer, A.

2008(10), P10008. doi:10.1088/1742- O., Borsboom, D., & Westenberg, P. M. (2020). A

5468/2008/10/P10008 cross-sectional and longitudinal network analysis

Chen, J., & Chen, Z. (2008). Extended Bayesian approach to understanding connections among

information criteria for model selection with large social anxiety components in youth. Journal of

model spaces. Biometrika, 95(3), 759-771. Abnormal Psychology, 129(1), 82.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/asn034 doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000484

Christensen, A. P. (2018). NetworkToolbox: Methods Müller, B., Reinhardt, J., & Strickland, M. T. (2012).

and Measures for Brain, Cognitive, and Neural networks: an introduction. Springer

Psychometric Network Analysis in R. R J., 10(2), Science & Business Media.

422. Newman, M. (2010). Networks: An Introduction.

Costantini, G., Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., Perugini, Oxford University Press.

M., Mõttus, R., Waldorp, L. J., & Cramer, A. O. Office for National Statistics. (2018). Young people

(2015). State of the aRt personality research: A by ethnicity in England and UK. Retrieved

tutorial on network analysis of personality data in February 8, 2021, from

R. Journal of Research in Personality, 54, 13-29. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcom

doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.07.003 munity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/adhocs/008436yo

Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). ungpeoplebyethnicityinenglandanduk

Estimating psychological networks and their Paus, T., Keshavan, M., & Giedd, J. N. (2008). Why

accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research do many psychiatric disorders emerge during

Methods, 50(1), 195-212. doi:10.3758/s13428- adolescence? Nature reviews neuroscience, 9(12),

017-0862-1 947-957. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2513

Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O., Waldorp, L. J., Romeo, R. D. (2013). The teenage brain: The stress

Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). response and the adolescent brain. Current

qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in directions in psychological science, 22(2), 140-

psychometric data. Journal of statistical software, 145. doi:10.1177/0963721413475445

48(4), 1-18. Rubinov, M., & Sporns, O. (2011). Weight-

doi:https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i04 conserving characterization of complex functional

Fried, E. I., van Borkulo, C. D., Cramer, A. O., brain networks. Neuroimage, 56(4), 2068-2079.

Boschloo, L., Schoevers, R. A., & Borsboom, D. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.

(2017). Mental disorders as networks of problems: 069

a review of recent insights. Social Psychiatry and Saxena, S., Jané-Llopis, E., & Hosman, C. (2006).

Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(1), 1-10. Prevention of mental and behavioural disorders:

doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z implications for policy and practice. World

Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J., & Psychiatry, 5(1), 5.

Sartorius, N. (2015). Toward a new definition of Serafini, G., Parmigiani, B., Amerio, A., Aguglia, A.,

mental health. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 231. Sher, L., & Amore, M. (2020). The psychological

doi:10.1002/wps.20231 impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the

Janssen, L. H., Kullberg, M.-L. J., Verkuil, B., van general population. QJM: An International

Zwieten, N., Wever, M. C., van Houtum, L. A., Journal of Medicine, 113(8), 531-537.

Wentholt, W. G., & Elzinga, B. M. (2020). Does doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201

the COVID-19 pandemic impact parents’ and Skinner, E. A., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007).

adolescents’ well-being? An EMA-study on daily The development of coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol.,

affect and parenting. PloS one, 15(10), e0240962. 58, 119-144.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240962

Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology

Wu et al. 174

doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.1104

05.085705

Stochl, J., Soneson, E., Wagner, A., Khandaker, G.,

Goodyer, I., & Jones, P. (2019). Identifying key

targets for interventions to improve psychological

wellbeing: replicable results from four UK

cohorts. Psychological medicine, 49(14), 2389-

2396. doi:10.1017/S0033291718003288

Tarrasch, R. (2015). Mindfulness meditation training

for graduate students in educational counseling

and special education: A qualitative analysis.

Journal of Child and family Studies, 24(5), 1322-

1333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-

9939-y

Team, R. C. (2013). R: A language and environment

for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria.

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph,

S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-

Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh

mental well-being scale (WEMWBS):

development and UK validation. Health and

Quality of life Outcomes, 5(1), 63.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression shrinkage and

selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal

Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological),

58(1), 267-288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-

6161.1996.tb02080.x

World Health Organisation (2001). The World Health

Report 2001: Mental health: New understanding,

new hope.

van Borkulo, C., Boschloo, L., Borsboom, D.,

Penninx, B., Waldorp, L., & Schoevers, R. (2016).

Package ‘NetworkComparisonTest’.

Vittersø, J. (2013). Feelings, meanings, and optimal

functioning: Some distinctions between hedonic

and eudaimonic well-being. In A. S. Waterman

(Ed.), The best within us: Positive psychology

perspectives on eudaimonia (pp. 39–55).

American Psychological Association.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/14092-003

Zeng, G., Peng, K., & Hu, C.-P. (2019). The Network

Structure of Adolescent Well-Being Traits:

Results From a Large-Scale Chinese Sample.

Frontiers in psychology, 10, 2783.

doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02783

Journal of Emotion and Psychopathology

You might also like

- Massage Therapy and MedicationsOxfordDocument232 pagesMassage Therapy and MedicationsOxfordboutique.chersNo ratings yet

- Influence of Social Media UseDocument11 pagesInfluence of Social Media UseNusrah AdibNo ratings yet

- Group 1 RRLDocument21 pagesGroup 1 RRLRyan Aggasid100% (5)

- Free Preview - The Stall Slayer PDFDocument9 pagesFree Preview - The Stall Slayer PDFRohit RumadeNo ratings yet

- Know Your Soil PDFDocument20 pagesKnow Your Soil PDFbpcdivNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Post Covid 19 On Youth's Mental IllnessDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Post Covid 19 On Youth's Mental Illness23005583No ratings yet

- McPherson2014 Article TheAssociationBetweenSocialCapDocument16 pagesMcPherson2014 Article TheAssociationBetweenSocialCapMalaika Khan 009No ratings yet

- Debate Recognising and Responding To The Mental Health Needs of Young People in The Era of COVID-19Document2 pagesDebate Recognising and Responding To The Mental Health Needs of Young People in The Era of COVID-19CECILIA BELEN FIERRO ALVAREZNo ratings yet

- The Students' Experiences of Mental Health CrisisDocument8 pagesThe Students' Experiences of Mental Health CrisisInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Mental Health of Adolescents During Lockdown Period of Covid 19Document10 pagesMental Health of Adolescents During Lockdown Period of Covid 19nikhil yadavNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1, 2, 3 (Lovely)Document14 pagesChapter 1, 2, 3 (Lovely)Early Joy BorjaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Social Support On Mental Health in Chinese Adolescents During The Outbreak of COVID-19Document5 pagesThe Effect of Social Support On Mental Health in Chinese Adolescents During The Outbreak of COVID-19Nurul HayatiNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of Music-Based Interventions To Improve Treatment Engagement and Mental Health Outcomes For Adolescents and Young AdultsDocument30 pagesSystematic Review of Music-Based Interventions To Improve Treatment Engagement and Mental Health Outcomes For Adolescents and Young Adultsamycecile.musicNo ratings yet

- Ramírez Et Al (2022) ACES: Mental Health Consequences and Risk Behaviors in Women and Men in ChileDocument16 pagesRamírez Et Al (2022) ACES: Mental Health Consequences and Risk Behaviors in Women and Men in ChileKaren CárcamoNo ratings yet

- Young People's Mental Health Is Finally Getting The Attention It NeedsDocument7 pagesYoung People's Mental Health Is Finally Getting The Attention It NeedsJet Lauros CacalNo ratings yet

- JAdoHealth - Measurement of Mental Health Problems - 092021Document2 pagesJAdoHealth - Measurement of Mental Health Problems - 092021cherry blossomNo ratings yet

- Ageism, Healthy Life Expectancy and Population Ageing: How Are They Related?Document11 pagesAgeism, Healthy Life Expectancy and Population Ageing: How Are They Related?Betsabé CastroNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Pandemic: Age-Related Di in Measures of Stress, Anxiety and Depression in CanadaDocument10 pagesCOVID-19 Pandemic: Age-Related Di in Measures of Stress, Anxiety and Depression in CanadaCornelia AdeolaNo ratings yet

- Studies - INTERNET ADDICTION AND MENTAL HEALTH STATUSDocument9 pagesStudies - INTERNET ADDICTION AND MENTAL HEALTH STATUSRio Manuel ValenteNo ratings yet

- Avedissian, Alayan - 2021 - Adolescent Well-Being A Concept AnalysisDocument11 pagesAvedissian, Alayan - 2021 - Adolescent Well-Being A Concept Analysisisidora2003No ratings yet

- Effects of Parental Favoritism in Childhood On Depression Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Evidence From ChinaDocument15 pagesEffects of Parental Favoritism in Childhood On Depression Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Evidence From Chinayow kiNo ratings yet

- Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness On The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in The Context of COVID-19 (2020)Document26 pagesRapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness On The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in The Context of COVID-19 (2020)Alberto Martínez GNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review: The Influence of Social Media On Depression, Anxiety and Psychological Distress in AdolescentsDocument6 pagesA Systematic Review: The Influence of Social Media On Depression, Anxiety and Psychological Distress in AdolescentsShivani NeroyNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Effect To The FamilyDocument10 pagesMental Health Effect To The FamilyJamie CalaguasNo ratings yet

- Kousoulis Et Al 2020Document17 pagesKousoulis Et Al 2020falrofiaiNo ratings yet

- Intro (Cheryl Joy Agsaoay)Document8 pagesIntro (Cheryl Joy Agsaoay)Ryza UriceNo ratings yet

- Neill2021 Article MediaConsumptionAndMentalHealtDocument9 pagesNeill2021 Article MediaConsumptionAndMentalHealtKhadijaNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument12 pagesArticles: BackgroundputputNo ratings yet

- CAPE CDev SI Manuscript RevisionDocument39 pagesCAPE CDev SI Manuscript RevisionNyoba DoangNo ratings yet

- Group 1 - GESTSResearchPaperDocument35 pagesGroup 1 - GESTSResearchPaperJames Ryan AlzonaNo ratings yet

- The Bucharest Early Intervention Project - Adolescent Mental Health and Adaptation Following Early DeprivationDocument8 pagesThe Bucharest Early Intervention Project - Adolescent Mental Health and Adaptation Following Early DeprivationMerly JHNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s11136 019 02309 3Document9 pages10.1007@s11136 019 02309 3Mundo Tan PareiraNo ratings yet

- Shared Goals For Mental Health Research What Why and When For The 2020sDocument10 pagesShared Goals For Mental Health Research What Why and When For The 2020saimeejacobs370No ratings yet

- 34921076_Published_articleDocument16 pages34921076_Published_articleFeelin Fatwa TitiharjaNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review The Influence of Social Media On Depression Anxiety and Psychological Distress in AdolescentsDocument16 pagesA Systematic Review The Influence of Social Media On Depression Anxiety and Psychological Distress in Adolescentsjerimaeminiosa396No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 ResearchDocument8 pagesChapter 1 Researchlea jumawanNo ratings yet

- Jamapediatrics Moreno 2023 Ed 220035 1673637425.56866Document2 pagesJamapediatrics Moreno 2023 Ed 220035 1673637425.56866Lili CarrizalesNo ratings yet

- Everett Et Al 2020 Moral Messaging COVID19 PsyArXiv V3 PDFDocument23 pagesEverett Et Al 2020 Moral Messaging COVID19 PsyArXiv V3 PDF19193655No ratings yet

- Child Adoles Ment Health - 2022 - Ma - Review School‐Based Interventions to Improve Mental Health Literacy and ReduceDocument11 pagesChild Adoles Ment Health - 2022 - Ma - Review School‐Based Interventions to Improve Mental Health Literacy and ReducepalomaNo ratings yet

- Ciocanel2017 Article EffectivenessOfPositiveYouthDeDocument22 pagesCiocanel2017 Article EffectivenessOfPositiveYouthDeumairzulkefliNo ratings yet

- Social Media and Adolescent Mental Health: The Good, The Bad and The UglyDocument8 pagesSocial Media and Adolescent Mental Health: The Good, The Bad and The UglyGlory Rebecca SRNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j CHB 2019 106160Document37 pages10 1016@j CHB 2019 106160soartasoNo ratings yet

- Impact of CovidDocument36 pagesImpact of CovidLuis FonbuenaNo ratings yet

- Fear of LonelinessDocument25 pagesFear of LonelinessHà Anh Lê VũNo ratings yet

- Jin PaperDocument24 pagesJin Paperlucypurr.the.catNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Internasional - Angelia Reza D - 6411420035Document11 pagesJurnal Internasional - Angelia Reza D - 6411420035Angelia Reza DevantyNo ratings yet

- Day 056Document11 pagesDay 056Angelia Reza DevantyNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Healthcare For College Students and Young Adults Final AgDocument14 pagesPortfolio Healthcare For College Students and Young Adults Final Agapi-319589093No ratings yet

- Preprint - Exploring The Associations Between Resilience, Dispositional Hope, Well-Being, and Psychological Health AmongDocument27 pagesPreprint - Exploring The Associations Between Resilience, Dispositional Hope, Well-Being, and Psychological Health Amongparvathy bNo ratings yet

- Covid-19. Is Teenagers Healt in Crisis PDFDocument15 pagesCovid-19. Is Teenagers Healt in Crisis PDFR JackNo ratings yet

- Coping With Covid-19: Resilience and Psychological Well-Being in The Midst of A PandemicDocument11 pagesCoping With Covid-19: Resilience and Psychological Well-Being in The Midst of A PandemicMáthé AdriennNo ratings yet

- Young People's Understanding of Mental Illness: J. Secker, C. Armstrong and M. HillDocument11 pagesYoung People's Understanding of Mental Illness: J. Secker, C. Armstrong and M. HillFAYANo ratings yet

- Can Ikigai Predict Anxiety Depression and WellbeingDocument13 pagesCan Ikigai Predict Anxiety Depression and WellbeingAqidatul IzzaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0165178122004073 MainDocument16 pages1 s2.0 S0165178122004073 MainEgy Sunanda Putra Direktorat Poltekkes JambiNo ratings yet

- Gender Difference in The Change of Adolescents' Mental Health and Subjective Wellbeing TrajectoriesDocument10 pagesGender Difference in The Change of Adolescents' Mental Health and Subjective Wellbeing Trajectoriesnindi jemmyNo ratings yet

- s11205 020 02515 4Document32 pagess11205 020 02515 4rifka yoesoefNo ratings yet

- Changes in Young Adults' Mental Well-Being Before and During The Early Stage of The COVID-19 Pandemic: Disparities Between Ethnic Groups in GermanyDocument14 pagesChanges in Young Adults' Mental Well-Being Before and During The Early Stage of The COVID-19 Pandemic: Disparities Between Ethnic Groups in GermanyRaniaNo ratings yet

- 2 LIFE SATISFACTION, YouthDocument8 pages2 LIFE SATISFACTION, Youthszeling5032No ratings yet

- "A Study On Mental Health Problems of Adolescent" With Special Reference To Coimbatore DistrictsDocument4 pages"A Study On Mental Health Problems of Adolescent" With Special Reference To Coimbatore DistrictsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- A Study of Mental Health of Teenagers - Google FormsDocument10 pagesA Study of Mental Health of Teenagers - Google FormsIťs Śtylìsh RøckÿNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument10 pagesResearch PaperVishalNo ratings yet

- Büttner Ma BmsDocument27 pagesBüttner Ma BmsVon Gabriel GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019: a psychological perspectiveFrom EverandThe Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019: a psychological perspectiveNo ratings yet

- Fist Palm Test (Fipat) : A Bedside Motor Tool To Screen For Global Cognitive StatusDocument8 pagesFist Palm Test (Fipat) : A Bedside Motor Tool To Screen For Global Cognitive StatusAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Tourette Lancet 2002Document10 pagesTourette Lancet 2002Andreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Kostas 2Document11 pagesKostas 2Andreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- 312 FullDocument11 pages312 FullAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Tic Disorder LeafletDocument2 pagesTic Disorder LeafletAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Progress in Research On Tourette SyndromeDocument18 pagesProgress in Research On Tourette SyndromeAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Training in Children With Tic DisordersDocument8 pagesTraining in Children With Tic DisordersAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Fnins 15 647579Document13 pagesFnins 15 647579Andreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Neurobiology of Tourette SyndromeDocument9 pagesNeurobiology of Tourette SyndromeAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Tic Disorders in ChildrenDocument3 pagesTic Disorders in ChildrenAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- European Clinical Guidelines For Tourette Syndrome and Other Tic DisordersDocument24 pagesEuropean Clinical Guidelines For Tourette Syndrome and Other Tic DisordersAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- ABCS Scale - Instructions 11.18 PDFDocument2 pagesABCS Scale - Instructions 11.18 PDFAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Tic Disorders ChildhoodDocument4 pagesTic Disorders ChildhoodAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Kok - Emotion Regulation - Encyclopedia of Personality and Indiv Differences - DEF PDFDocument24 pagesKok - Emotion Regulation - Encyclopedia of Personality and Indiv Differences - DEF PDFAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Tic Disorders Some Key Issues For DSM-VDocument11 pagesTic Disorders Some Key Issues For DSM-VAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Bergey Dissertation AbstractDocument2 pagesBergey Dissertation AbstractAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Coaching and Mentoring Toolkit v2 Final 26.3.2021 1 PDFDocument32 pagesCoaching and Mentoring Toolkit v2 Final 26.3.2021 1 PDFAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Social Behaviour Mapping - Expected PDFDocument1 pageSocial Behaviour Mapping - Expected PDFAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Being Flexibleand Adjusting ExpectationsDocument14 pagesBeing Flexibleand Adjusting ExpectationsAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- 3.1 BeingFlexibleAndShiftingExpectations LP-1Document5 pages3.1 BeingFlexibleAndShiftingExpectations LP-1Andreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Flexible Thinking Through TheaterDocument5 pagesTeaching Flexible Thinking Through TheaterAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Flexible Thinking SituationsDocument1 pageFlexible Thinking SituationsAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- 37 2021 HotandcoldexecutivefunctionsinthebrainAprefrontal Cingularnetwork PDFDocument19 pages37 2021 HotandcoldexecutivefunctionsinthebrainAprefrontal Cingularnetwork PDFAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Flexible Thinking - How To Deal With ChangeDocument9 pagesFlexible Thinking - How To Deal With ChangeAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Flexible Thinking ActivityDocument2 pagesFlexible Thinking ActivityAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Research - Symposium - Abstracts - PostersDocument32 pages2017 - Research - Symposium - Abstracts - PostersAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Feduc 07 751801Document12 pagesFeduc 07 751801Andreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- FlexibleDocument1 pageFlexibleAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Brandemotionalconnectionbm20123a PDFDocument16 pagesBrandemotionalconnectionbm20123a PDFAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Childrens Social-Emotional Wellbeing Paper PDFDocument46 pagesChildrens Social-Emotional Wellbeing Paper PDFAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Analisis Penerapan Metode Activity Based Costing (ABC) Dalam Menentukan Tarif Jasa Rawat Inap Di RSUD Kota PrabumulihDocument12 pagesAnalisis Penerapan Metode Activity Based Costing (ABC) Dalam Menentukan Tarif Jasa Rawat Inap Di RSUD Kota PrabumulihAffira AfriNo ratings yet

- Soal Inggris - 2Document6 pagesSoal Inggris - 2vivitrisami05No ratings yet

- Synthesis of The Work of Enderlein, Etc PDFDocument3 pagesSynthesis of The Work of Enderlein, Etc PDFpaulxe100% (1)

- Purine Rich FoodDocument3 pagesPurine Rich Foodttstanescu4506No ratings yet

- 10besar Kode PenyakitDocument5 pages10besar Kode PenyakitDEWINo ratings yet

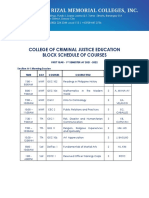

- College of Criminal Justice Education Block Schedule of CoursesDocument12 pagesCollege of Criminal Justice Education Block Schedule of CoursesKristel Ann ManlangitNo ratings yet

- Qdoc - Tips - Prometric Practice Exam For Nurses Test 1Document6 pagesQdoc - Tips - Prometric Practice Exam For Nurses Test 1Ponnudev100% (1)

- Chris Hemsworth's God-Like Thor WorkoutDocument8 pagesChris Hemsworth's God-Like Thor WorkoutmarticarrerasNo ratings yet

- CraniectomyDocument5 pagesCraniectomytabanaoNo ratings yet

- Kohler Students Scores Tops in The State Again For ACT ScoresDocument20 pagesKohler Students Scores Tops in The State Again For ACT ScoresThe Kohler VillagerNo ratings yet

- How To Prevent BullyingDocument4 pagesHow To Prevent BullyingLiezel-jheng Apostol LozadaNo ratings yet

- 21 2023 ICTP QA ProgrammeDocument54 pages21 2023 ICTP QA ProgrammeBui Duy LinhNo ratings yet

- Activity #1: ETHICAL CASE Name: Date: Year/Section: Grade/scoreDocument4 pagesActivity #1: ETHICAL CASE Name: Date: Year/Section: Grade/scoreJovie FabrosNo ratings yet

- Jsa For Radiography WorkDocument2 pagesJsa For Radiography WorkVipul ShankarNo ratings yet

- Annual Barangay Youth Investment Program (Abyip)Document4 pagesAnnual Barangay Youth Investment Program (Abyip)Nhelyn Manuel0% (1)

- Technical Datasheet DHFFMDocument2 pagesTechnical Datasheet DHFFMSamerNo ratings yet

- Humanitarians in The Face of Atrocities: Case Studies: Syria and CARDocument19 pagesHumanitarians in The Face of Atrocities: Case Studies: Syria and CARMigs MontrealNo ratings yet

- Pga 2014 ProspectusDocument31 pagesPga 2014 ProspectusKaranGargNo ratings yet

- Substance AbuseDocument54 pagesSubstance AbuseCharles CastilloNo ratings yet

- Punctate: NumberDocument6 pagesPunctate: NumberMuhamad Chairul SyahNo ratings yet

- Tratament Diuretic in Insuficienta CardiacaDocument19 pagesTratament Diuretic in Insuficienta CardiacaOlga HMNo ratings yet

- Mini HabitsDocument33 pagesMini HabitsNeven Ilak100% (2)

- Case Study 8 Construction SafetyDocument2 pagesCase Study 8 Construction SafetyJerome BricenioNo ratings yet

- National Program For Rehabilitation of Polluted Site - A Case StudyDocument4 pagesNational Program For Rehabilitation of Polluted Site - A Case StudyijeteeditorNo ratings yet

- Construction Site Management ChecklistDocument6 pagesConstruction Site Management ChecklistAbdulaziz IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Trojan Battery Company Valve Regulated Lead Acid Battery Safety Data SheetDocument12 pagesTrojan Battery Company Valve Regulated Lead Acid Battery Safety Data SheetNels OdrajafNo ratings yet

- Passenger Locator Form: Non-Red ListDocument4 pagesPassenger Locator Form: Non-Red ListSamadrukNo ratings yet