Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Symmetrical Alopecia

Symmetrical Alopecia

Uploaded by

darlyn hurtadoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Symmetrical Alopecia

Symmetrical Alopecia

Uploaded by

darlyn hurtadoCopyright:

Available Formats

Downloaded from http://inpractice.bmj.com/ on May 24, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.

com

Alopecia is, at first sight,

a difficult and confusing

problem to manage

Symmetrical alopecia

in the dog ROSARIO CERUNDOLO

ALOPECIA is characterised by the absence of hair or by its loss from areas where it is normally present.

It may be congenital or acquired and may reflect a cutaneous problem or may be the consequence of

underlying internal diseases, the recognition of which is fundamental for the health of an animal.

A variety of pruritic and non-pruritic diseases, such as those caused by ectoparasites (eg, scabies and

demodicosis), dermatophytes, bacterial or yeast infections, and hypersensitivities, may initially show

patterns of focal or multifocal alopecia which, if incorrectly managed, can progress to produce a more or

less symmetrical generalised alopecia. In this article, however, discussion is restricted to the approach to

the diagnosis of diseases causing symmetrical alopecia in dogs, including diseases of the endocrine glands

Rosario Cerundolo and of the hair follicle unit. These are usually characterised by a non-inflammatory, non-pruritic,

graduated from progressive alopecia affecting the head, neck, flanks, perineal area and/or thighs.

Naples in 1987. After

a period in small

animal practice, he

joined the medicine SIGNALMENT

unit of the University

of Veterinary

Medicine in Naples. Age

In 1995, he started a Congenital alopecia is likely to be caused by an ectoder-

residency in

dermatology at the mal defect. However, some breeds are genetically pre-

RVC and is currently disposed to alopecia and have been specifically selected

completing his

doctorate in for this feature on aesthetic grounds.

veterinary medicine Hair loss commencing during the first year of life

in Naples. His may be caused by hair follicle abnormalities such as

research interests

include canine black hair follicular dysplasia and colour dilution alope-

alopecia and cia (Roperto and others 1995). Alternatively, it may be

melanoma in pigs.

He holds the

certificate in

veterinary

dermatology and is

a diplomate of the

European College Yorkshire terrier with colour dilution alopecia. Hair loss has

of Veterinary occurred in areas of the body with diluted coat colour. The

Dermatology. head and the ventral body, which have a tan coat colour,

have normal hairs. Reproduced with permission from Roperto

and others (1995)

caused by late phase dermatomyositis (Ferguson and

others 1999).

Adult dogs developing alopecia may be suffering

from alopecia X (formerly called growth hormone

responsive dermatosis or congenital adrenal hyperplasia-

like syndrome) (Schmeitzel and others 1995), follicular

dysplasia (Miller and Scott 1995), pattern baldness, post-

Chinese crested dog with congenital alopecia. In this breed, clipping alopecia, sebaceous adenitis or endocrine abnor-

a variable amount of hair is usually present on the head and

limbs malities (see table on page 357).

350 In Practice * JULY/AUGUST 1999

Downloaded from http://inpractice.bmj.com/ on May 24, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Dachshund with pattern

baldness, showing alopecia

of the caudal aspect of the

hindlegs and the genital

area

Shetland sheepdog with dermatomyositis. Areas of scarring

alopecia with crusts are present on the face Yorkshire terrier

with pattern baldness.

Progressive alopecia and

Breed hyperpigmentation of the

ear pinnae has occurred

Certain breeds are predisposed to alopecic conditions since two years of age

such as alopecia X, dermatomyositis, follicular dyspla-

sia, pattern baldness, post-clipping alopecia, seasonal

flank alopecia (Curtis and others 1996) and sebaceous

adenitis (see table on page 352).

Coat colour

Coat colour may provide useful diagnostic information

in pigment-related alopecia such as black hair follicular

dysplasia and colour dilution alopecia. Careful evalua-

tion of the coat may be required, as some dilute colours

Crossbred with post-clipping

are subtle. alopecia. Four months after

clipping there was no sign

of hair regrowth

Sex

In males and females neutered early in life a progressive

alopecia may occur. Sertoli-cell tumours in dogs and

hyperoestrogenism in bitches may also lead to alopecia.

(above and below) Pomeranian with alopecia X, showing

progressive hair loss on the nodec and along the dorsum.

Cutaneous hyperpigmentation Is commonly present in the

affected areas

Standard poodle with sebaceous adenitis. There is

marked hair loss, which started on the dorsal midline and

is progressing on both sides. Follicular casts were evident

on plucked hairs. Hypothyroidism had previously been

suspected and trial therapy with L-thyroxine had been

undertaken for a few months before referral; this had

not produced any hair regrowth

In Practice * JULY/AUGUST 1999

351

Downloaded from http://inpractice.bmj.com/ on May 24, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Seasonal flank alopecia German shepherd

in an Airedale terrier dog with a Sertoli-

(top) and boxer cell tumour.

(bottom). In both cases, Alopecia is

progressive hair loss affecting the

and hyperpigmentation ventral tail, perineal

started on the flanks in area and hindlegs.

December and Palpation of the

spontaneous hair scrotum revealed

regrowth and that one testicle

resolution of the was abnormal in

hyperpigmentation shape and size.

was evident the Histopathology

following spring confirmed

the suspected

diagnosis. Picture,

Dr Fabia Scarampella,

Italy

ical events, such as pregnancy and lactation, or patholog-

ical events, such as severe systemic disease, shock or

surgery (eg, telogen effluvium). Alopecia may also occur

a few days after the administration of cytotoxic agents,

such as methotrexate and cyclophosphamide, or toxic

substances, such as selenium, thallium and arsenic (eg,

anagen defluxion), although this is quite rare. Failure of

hair regrowth after clipping is suggestive of either

hypothyroidism or post-clipping alopecia. In dogs of any

age, there may be concurrent demodicosis contributing

to the hair loss.

HISTORY

Seasonal pattern

Consideration of the dog's age at the time of onset of Alopecia with a cyclical pattern related to the time of

alopecia, its rate of onset, its resolution or progression, year is seen in Portuguese water dogs with follicular dys-

and the presence of a cyclical pattern relating to the time plasia, and in dogs with seasonal flank alopecia.

of year, will help in compiling a list of differential

diagnoses. Location and progression of alopecia

Progressive alopecia in areas of the body with black or

Age and time of onset diluted hair colour is suggestive of black hair follicular

The onset of alopecia should always be related to the dysplasia or colour dilution alopecia. In adult dogs with

dog's age, and any physiological and/or pathological endocrine abnormalities, progressive hair loss usually

event, management change or therapeutic treatment. affects the trunk and tail and then extends over the body.

Alopecia sometimes occurs a few weeks after physiolog- The presence of alopecia with cutaneous hyperpigmenta-

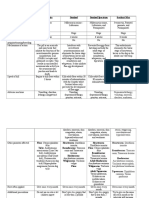

Black hair Colour dilution Dermatomyositis Follicular Pattern Post-clipping Sebaceous Seasonal flank

Alopecia X adenitis alopecia

follicular alopecia dysplasia baldness alopecia

ayspiasia

,r4ICn la cia

Bernese mountain Beauceron Alaskan Boston terrier Alaskan Akita inu Airedale terrier

Chow chow Basset hound Border collie

Beagle dog Chow chow malamute Boxer malamute Border collie

Keeshond Chow chow English springer Bouvier des Flandres

Pomeranian Bearded collie Chihuahua German shepherd Curly-coated Chihuahua

Poodle Border collie Chow chow dog retriever Dachshund German spaniel Boxer

Crossbred* Kuvasz Irish water Greyhound shepherd dog German Dachshund

Samoyed Cavalier King shepherd dog Dobermann

Charles spaniel Dachshund Lakeland terrier spaniel Pinscher Keeshond

Welsh corgi

Dobermann Rough collie Portuguese Weimaraner Samoyed Samoyed English bulldog

Crossbred* Standard French bulldog

Gordon setter Great Dane Shetland sheepdog water dog Whippet Siberian husky

Welsh corgi Siberian husky poodle Golden or labrador

Jack Russell Greyhound Vizsla retriever

terrier Irish setter Poodle

Pointer Newfoundland Rhodesian ridgeback

Saluki Pinscher Schnauzer

Poodle Scottish terrier

Saluki

Schipperke

Shetland

sheepdog

Silky terrier

Staffordshire bull

terrier

Whippet

Yorkshire terrier

* Any crossbred with two or three coat colours

352 In Practice * JULY/AUGUST 1999

Downloaded from http://inpractice.bmj.com/ on May 24, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

tion confined to the flanks is suggestive of seasonal flank

alopecia or a Sertoli-cell tumour. Seasonal flank alopecia

resolves spontaneously with the change of the season

while Sertoli-cell tumours usually progress to the caudal

thighs, perineal, genital and ventral abdominal areas; in

addition, cutaneous thickening may be seen. In hypo-

estrogenism and hyperoestrogenism, the alopecia usually

occurs first in the genital and perineal areas and then

progresses to involve the ventral abdomen, caudal and

medial thighs, and the neck. Telogen effluvium and ana-

gen defluxion are characterised by sudden-onset alope-

cia, which occurs a few months or a few days/weeks,

respectively, after an insult to the hair follicle. Slow-

onset alopecia is typical of endocrinopathies, follicular

dysplasia, pattern baldness or sebaceous adenitis. The

Irish water spaniel with follicular dysplasia. Progressive

progression of alopecia may also be related to other. hair loss has affected the dorsum, rump and subsequently

concurrent conditions such as demodicosis or hypersen- the lateral trunk. Concurrent hypothyroidism had been

sitivity disorders. diagnosed and treated with L-thyroxine but no hair

regrowth occurred over a one-year follow-up period

Concurrent cutaneous lesions

* The presence of papules and pustules in alopecic Miniature poodle with

areas may suggest pyoderma, which commonly occurs hyperadrenocorticism.

Progressive alopecia has

secondarily to follicular dysplasia or endocrinopathies. affected the trunk, neck

* Cutaneous hyperpigmentation and thickening may and limbs

occur in cases of Sertoli-cell tumour, seasonal flank

alopecia, hypothyroidism or hyperoestrogenism.

* Scales and follicular casts are seen in dogs with

endocrine disorders and in sebaceous adenitis.

* Ulceration with scales and crusts and subsequent

scarring alopecia is common in dermatomyositis.

* Comedones and secondary pyoderma present in some

endocrinopathies may also be a sign of a concurrent

demodicosis.

Concurrent pruritus

In many dogs, alopecia is the result of pruritus. The pres-

ence or absence of pruritus is an important factor to be

considered in the investigation of the alopecia. CLINICAL APPROACH

Ectoparasites and secondary bacterial infections are

common causes of pruritus and may complicate any of General physical examination

the conditions discussed in this article. Therefore, A general physical examination should always be

antiparasitic or antibiotic therapy should be instituted as conducted in order to detect any abnormality present in

part of the initial approach, where appropriate. other organs which may be related to the alopecia or

which may influence further tests to be carried out

Previous diseases or therapies (eg, care should be taken when carrying out a skin biop-

A history of previous dermatological or other non- sy under general anaesthesia in dogs with cardiac, hepat-

dermatological diseases and information regarding ic and/or renal failure). Examination of the genitals

previous or current medications, such as antitumour might help to rule out the presence of a testicular mass

antimitotics (eg, doxorubicin), may help to explain the such as a Sertoli-cell tumour or identify abnormal vulval

hair loss. Prolonged therapy with glucocorticoids may enlargement in cases of hyperoestrogenism.

lead to iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism.

A lack of response following trial therapies, such as Dermatological examination

hormonal supplementation (eg, L-thyroxine), may indi- A careful dermatological examination should be under-

cate that the diagnosis needs to be reconsidered. taken to evaluate the distribution of the alopecia. The

condition of the hair- for instance, whether it is easily

Other clinical signs epilated or broken - in non-affected areas and at the

Concurrent clinical signs may suggest internal diseases. edge of the lesions should be assessed. The presence of

Polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia and a pendulous concurrent primary or secondary cutaneous lesions may

abdomen indicate possible hyperadrenocorticism, while give useful clues as to the cause of the alopecia. The

lethargy and obesity may suggest hypothyroidism. thickness of the skin is decreased in hyperadrenocorti-

Abnormalities of the oestrous cycle may point to cism, but increased in hypothyroidism.

hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism or hyperoestro-

genism. In hyperoestrogenism, gynaecomastia and Differential diagnosis

vulval enlargement may also occur. Lack of hair A list of differential diagnoses should be compiled so

regrowth in previously clipped areas may indicate an that dermatological investigations can be selected on a

underlying endocrinopathy. rational basis.

In Practice * JULY/AUGUST 1999 355

Downloaded from http://inpractice.bmj.com/ on May 24, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

Initial investigations

Coat brushing, cytology, skin scrapings, tape strips and a

Wood's lamp examination should always be carried out.

Plucked hairs should be examined both macroscopi-

cally for the presence of follicular casts, such as those

seen in sebaceous adenitis, and microscopically (tri-

chogram) to identify the hair cycle stage, the presence of

ectoparasites (eg, Demodex species) or fungal spores. A

trichogram is also a useful tool to evaluate the hair

structure; for example, hair abnormality may lead to

fragility as seen in colour dilution alopecia. Examination Hair plucked from an area of diluted coat colour of the

of epilated hair from the edge of the alopecic areas will Yorkshire terrier pictured on page 350. There is an abnormal

amount of melanin in the hair medulla and cortex.

allow the hair cycle stage to be identified (eg, telogen or Magnification x 560

anagen) and may help to detect the possible cause of

alopecia. A predominance of telogen hairs may suggest, plasma concentration of endogenous thyroid stimulating

for example, telogen effluvium or endocrinopathies. Hair hormone (TSH) and total thyroxine (T4) give a good indi-

shafts which are damaged or distorted, or reduced in size cation of thyroid function, although a TSH stimulation

usually indicate anagen defluxion. test remains the best test to check thyroid function.

Determination of endogenous adrenocorticotropic hor-

Further investigations mone (ACTH) level, as well as ACTH stimulation and

If the results of the above tests have failed to produce a low-dose dexamethasone suppression tests, can be used

definitive diagnosis, albeit having allowed the list of sus- to diagnose hyperadrenocorticism. A sex hormone profile

pected diseases to be narrowed, further investigations are may be carried out to confirm a suspected Sertoli-cell

necessary. These should be selected according to the tumour, hyperoestrogenism or alopecia X. An abnormally

index of suspicion. Bacterial culture should be carried out high level of 17-hydroxyprogesterone (1 7-OHP) pre- and

in cases where recurrent pyoderma has already been treat- post-ACTH stimulation is commonly found in alopecia

ed with several antibiotics. Haematology, biochemistry X, but the correlation of this increase with the presence of

and urine analysis may be useful to evaluate the general alopecia is still unclear. Radiographs and ultrasound

health status of adult dogs with a permanent or recurrent investigations are useful to assess internal organs (eg,

alopecic condition or if a systemic disease, which may adrenal andlor testicular mass, and the presence of metas-

lead to alopecia, is suspected. Hormonal tests should be tases). Skin biopsy is usually necessary when the previ-

carried out if the clinical signs and results of blood and ous investigations have not led to a definitive diagnosis.

urine analysis suggest an endocrinopathy. The serum or Histopathology may show evidence of the cause of alope-

Suggested approach to the diagnosis of symmetrical alopecia

- O-3

I

I I II

i

Congenital Juvenile onset Adult onset

Black hair follicular I

dysplasia Non-endocrine

Colour dilution Endocrine

alopecia

Dermatomyositis

Thyroid Gonads Adrenals Alopecia areata

IT, Alopecia X Anagen defluxion

Hyperadrenocorticism Black hair follicular

dysplasia

Colour dilution

alopecia

Follicular dysplasia

Pattern baldness

Male Female Post-clipping alopecia

Hypogonadism Hypoestrogenism Sebaceous adenitis

Sertoli-cell tumour Hyperoestrogenism Telogen effluvium

356 In Practice o JULY/AUGUST 1999

Downloaded from http://inpractice.bmj.com/ on May 24, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Plucked normal hair base, showing the Plucked normal hair in the

typical appearance of an anagen hair. telogen phase. Magnification x 560

Magnification x 560

lin1=1VI ISEIaI-11cl z :XUl I mizl-

M ;{TO S 9 71 I40l1 IIDIIS :^t

,lS S - 0

Aetiology Location of alopecia Concurrent cutaneous Concurrent clinical signs Specific diagnostic tests Treatment

lesions

Anagen defluxion Systemic diseases, Diffuse NP Depends on underlying Trichogram Treatment of underlying

chemotherapy cause disease, withdrawal of

chemotherapy if possible

Black hair follicular Abnormal Areas of black coat Secondary pyoderma NP Trichogram, skin biopsy None

dysplasia distribution of colour

melanin

Colour dilution Abnormal Areas of diluted coat Secondary pyoderma NP Trichogram, skin biopsy None

alopecia distribution of colour

melanin

Dermatomyositis Immune mediated? Face, limbs, tail Erythema, scales, Myositis Skin biopsy, Pentoxifylline

crusts, scarring neurological tests

Follicular dysplasia Abnormality of hair Neck, trunk, hindlegs Secondary pyoderma, NP Skin biopsy None

follicle function comedones

Pattern baldness Unknown Pinnae, neck, hindlegs, Hyperpigmentation NP Skin biopsy None

inguinal area

Post-clipping Abnormality of hair Clipped areas Hyperpigmentation NP History of previous None

alopecia follicle function clipping

Sebaceous adenitis Unknown Head, trunk Scales, follicular casts NP Trichogram, skin biopsy Retinoids, essential

fatty acids

Telogen effluvium Stressful events Diffuse NP Depends on underlying Trichogram Spontaneous resolution,

(parturition, cause treatment of underlying

surgery, systemic disease

disease)

Alopecia X Unknown Neck, trunk, tail, Hyperpigmentation NP Blood tests (ACTH None

hindlegs stimulation test to

measure 17-OHP)

Hyperadreno- Pituitary or adrenal Trunk, tail Secondary pyoderma, Polyuria, polydipsia, Blood test (ACTH Mitotane,

corticism tumour, iatrogenic calcinosis cutis, polyphagia, pot-belly stimulation test, low

comedones

adrenalectomy

dose dexamethasone

suppression test), urine

analysis, ultrasound

Hypotnyroudism Primary, secondary Trunk, tail ..

Secondary pyoderma, Various (eg, lethargy, Blood tests (T4 and

comedones

T4 supplementation

obesity, neuromuscular, TSH determination,

cardiovascular, TSH stimulation test)

reproductive and

gastrointestinal disorders)

Seasonal flank Unknown Flanks Hyperpigmentation NP Skin biopsy

alopecia Spontaneous resolution,

melatonin

Sertoli-cell tumour Tumour of the Neck, rump, perineal Hyperpigmentation, Cryptorchidism, Blood test (oestrogens),

Sertoli cells Castration

and genital area linear preputial gynaecomastia, ultrasound

dermatosis pendulous prepuce,

attraction of

other males

Hypoestrogenism Spayed bitches Perineal and genital Hyperpigmentation NP None

area, neck, trunk, thighs Oestrogen

Hyperoestrogenism Cyst or tumour of Perineal and inguinal Hyperpigmentation, Oestrous cycle Blood test (oestrogen),

the ovary area, flanks comedones abnormalities ultrasound

Ovariectomy

NP Not present, ACTH Adrenocorticotropic hormone, 17-OHP 17-Hydroxyprogesterone, T4 Total thyroxine, TSH Thyroid stimulating hormone

In Practice * JULY/AUGUST 1999 357

Downloaded from http://inpractice.bmj.com/ on May 24, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

cia and will also provide information about the piload- Same standard poodle as

pictured on page 351,

nexal unit, cycle of the hair follicle and its integrity. In showing hair regrowth

most cases, histopathology is not diagnostic; however, if following essential fatty

the pathologist's report is evaluated together with the acid supplementation and

topical application of

dog's history, clinical signs and the results of the blood propylene glycol

tests, it may help to achieve a diagnosis.

THERAPEUTIC APPROACH

The therapeutic approach should be directed at both the

primary cause and the concurrent secondary disease, if

present. Some examples of therapeutic approaches are

given below, although these are not exhaustive.

* Initial treatment of PYODERMA may resolve the con-

current pruritus, ruling out causes of pruritic alopecia.

However, if there is no hair regrowth during or soon

after a course of antibiotics, further diagnostic tests are presence of alopecia. Scientific studies are currently

required before attempting any therapy. being carried out to identify the underlying pathology of

* ANAGEN DEFLUXION and TELOGEN EFFLUVIUM do not alopecia X. Development of a specific treatment for this

usually require any therapy. In anagen defluxion, with- condition will be dependent on a full understanding of

drawing the offending drug, if possible, or resolution of the underlying pathogenesis.

the underlying disease will result in hair regrowth. In * SEASONAL FLANK ALOPECIA is only an aesthetic prob-

telogen effluvium, hair will regrow as the dog recovers lem as dogs are otherwise healthy and no hormonal

from the stressful event(s) which led to the hair loss. abnormalities have been detected in affected dogs. Hair

* In BLACK HAIR FOLLICULAR DYSPLASIA and COLOUR regrowth usually occurs spontaneously at the end of

DILUTION ALOPECIA, hair loss is permanent. Essential spring or the beginning of summer. Anecdotal reports of

fatty acids or retinoids, and antibiotics, if necessary, may therapeutic trials using melatonin have suggested that

help to reduce the presence of concurrent skin lesions. this hormone may prevent hair loss, but further studies

* In DERMATOMYOSITIS, alopecia is permanent. are necessary to confirm this finding or to identify alter-

Pentoxifylline and vitamin E may help to reduce the native therapies.

severity and progression of the cutaneous lesions. * Alopecia associated with SEXUAL HORMONE IMBAL-

* In dogs with FOLLICULAR DYSPLASIAS, no specific ANCE (eg, Sertoli-cell tumour, hyperoestrogenism,

therapy has been reported although essential fatty acid hypoestrogenism) is easily treated by surgical removal of

supplementation may help the follicular function. the abnormal gonad or by hormone supplementation.

Antibiotic courses may also be necessary to control

secondary bacterial infections.

* No specific therapy has been reported for PATTERN SUMMARY

BALDNESS. Trial therapy using melatonin has been anec-

dotally reported. Alopecia can be caused by a wide variety of conditions

* POST-CLIPPING ALOPECIA does not require any therapy and is, at first sight, a difficult and confusing problem to

as the hair will grow back after a few weeks or months. manage. A methodical approach, involving consideration

* In SEBACEOUS ADENrrIS, the hair cycle is not affected of the dog's signalment, thorough history taking, a com-

and hair regrowth may occur. Essential fatty acids, plete clinical examination and appropriate selection of

retinoids and/or topical therapies, such as propylene gly- diagnostic investigations is essential for achieving an

col, reduce the severity of the cutaneous lesions caused accurate diagnosis and, thus, for both treatment and

by the destruction of the sebaceous glands. prognosis. The diagnosis is sometimes complicated by

the presence of concurrent diseases which may, or may

Endocrinopathies not, contribute to hair loss. It is important to remember

Most of the endocrinopathies can be easily treated as that hair loss per se is not life threatening. Where the

they respond either to hormonal supplementation, surgi- problem is only aesthetic, treatment of the alopecia may

cal removal of the tissue responsible for the altered hor- not be necessary.

mone production, medical therapy to diminish hormone

production, or withdrawal of the hormonal treatment. References

The institution of therapeutic trials without first carrying CURTIS, C. F., EVANS, H. & LLOYD, D. H. (1996) Investigation of the

out specific hormonal tests is to be discouraged, as they reproductive and growth hormone status of dogs affected by

idiopathic recurrent flank alopecia. Journal of Small Animal Practice

may produce no hair regrowth and sometimes cause side 37, 417-422 Further reading

effects. FERGUSON, E., CERUNDOLO, R., LLOYD, D. H., REST, J. & CAPPELLO, MORIELLO, K. (1995) Alopecia.

R. (1999) Dermatomyositis in the UK: five cases in the Shetland In Handbook of Small Animal

* ALOPECIA X has been reported to respond to growth sheepdog. Veterinary Record (In press) Dermatology. Eds K. A. Moriello

hormone supplementation, castration, or adrenolytic MILLER, W. H. & SCOTT, D. W. (1995) Follicular dysplasia of the and 1. S. Mason. Oxford,

Portuguese water dog. Veterinary Dermatology 6, 67-74 Pergamon. pp 75-91

drugs. However, in the author's opinion this condition ROPERTO, F., CERUNDOLO, R., RESTUCCI, B., VINCENSI, M. R., DE SCOTT, D. W., MILLER, W. H. &

should not be treated in any of these ways, as the alope- CAPRARIIS, D., DE VICO, G. & MAIOLINO, P. (1995) Colour dilution GRIFFIN, G. E. (1995) Endocrine

cia is only an aesthetic problem and the animals are alopecia (CDA) in ten Yorkshire terriers. Veterinary Dermatology 6, and metabolic diseases.

171-178 Congenital and hereditary

otherwise healthy. Trial therapy is not recommended but, SCHMEITZEL, L. P., LOTHROP, C. D. & ROSENKRANTZ, W. S. (1995) defects. In Muller & Kirk's Small

if used, owners should be informed of the possible side Congenital adrenal hyperplasia-like syndrome. In Kirk's Current Animal Dermatology, 5th edn.

Veterinary Therapy XII. Small Animal Practice. Ed J. D. Bonagura. Philadelphia, W. B. Saunders.

effects which may be more serious than the simple Philadelphia, W. B. Saunders. pp 600-604 pp 627-719, 736-805

In Practice * JULY/AUGUST 1999 359

Downloaded from http://inpractice.bmj.com/ on May 24, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Symmetrical alopecia in the dog

Rosario Cerundolo

In Practice 1999 21: 350-359

doi: 10.1136/inpract.21.7.350

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://inpractice.bmj.com/content/21/7/350

These include:

Email alerting Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the

service box at the top right corner of the online article.

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

You might also like

- Vete 4305 WK Group Case Study 10-12-15Document31 pagesVete 4305 WK Group Case Study 10-12-15api-278500650100% (1)

- Cat PresentationDocument33 pagesCat PresentationNadia Rahma NoviyantiNo ratings yet

- ALOPECIADocument90 pagesALOPECIAluckyswiss7776848No ratings yet

- Veterinary Drug FormularyDocument87 pagesVeterinary Drug FormularyAklilu AsmelashNo ratings yet

- Abdul Sami Presentation On Panamin G UpdateDocument22 pagesAbdul Sami Presentation On Panamin G UpdateNOMAN ALAMNo ratings yet

- Medical, Genetic and Behavioral Risk Factors of Purebred Dogs and Cats: a Quick Reference GuideFrom EverandMedical, Genetic and Behavioral Risk Factors of Purebred Dogs and Cats: a Quick Reference GuideNo ratings yet

- Dermatology For The Small Animal PractitionerDocument9 pagesDermatology For The Small Animal PractitionerDenisa VescanNo ratings yet

- Dog Coat Colour Genetics - A Review, Saif Et Al. 2020Document11 pagesDog Coat Colour Genetics - A Review, Saif Et Al. 2020Emmanuel A. Sessarego Dávila100% (1)

- Feline Vocalization - Excessive: Why Is My Cat Persistently Crying?Document4 pagesFeline Vocalization - Excessive: Why Is My Cat Persistently Crying?Brook Farm Veterinary CenterNo ratings yet

- FIP Cat TreatmentDocument14 pagesFIP Cat TreatmentRaihanNo ratings yet

- Phytotherapy in Veterinary PracticeDocument8 pagesPhytotherapy in Veterinary PracticesuniveuNo ratings yet

- Canine CastrationDocument6 pagesCanine CastrationAnonymous c215Fq6No ratings yet

- Horse BreedsDocument19 pagesHorse Breedssapu-98No ratings yet

- Neutering in CatsDocument10 pagesNeutering in CatsFatin Amirah RamliNo ratings yet

- CANINE-Medical Management of Chronic Otitis in DogsDocument11 pagesCANINE-Medical Management of Chronic Otitis in Dogstaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Hip Dysplasia in Dogs: A Guide For Dog OwnersDocument6 pagesHip Dysplasia in Dogs: A Guide For Dog Ownerstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- 2022 Aaha Canine Vaccinations GuidelinesDocument18 pages2022 Aaha Canine Vaccinations Guidelinesarumugamks7628No ratings yet

- Colic in HorsesDocument2 pagesColic in HorsesRamos SHNo ratings yet

- Feline Urologic Syndrome enDocument2 pagesFeline Urologic Syndrome enSitiNurjannahNo ratings yet

- In Practice Blood Transfusion in Dogs and Cats1Document7 pagesIn Practice Blood Transfusion in Dogs and Cats1何元No ratings yet

- Everything About DogsDocument326 pagesEverything About Dogstobiasaxo5653100% (2)

- Neonatalresuscitation: Improving The OutcomeDocument14 pagesNeonatalresuscitation: Improving The OutcomeManuela LopezNo ratings yet

- 1-Equine Digestion PowerPointDocument15 pages1-Equine Digestion PowerPointMazhar FaridNo ratings yet

- Diseases Common in Beef CattleDocument6 pagesDiseases Common in Beef Cattlejohn pierreNo ratings yet

- Rabbit BehaviorDocument7 pagesRabbit BehaviorJohn Mathew PakinganNo ratings yet

- Pregnant Dog - Pregnancy Signs in Dogs - Dog Article On Pets - Ca What To Expect When Your Dog Is ExpectingDocument3 pagesPregnant Dog - Pregnancy Signs in Dogs - Dog Article On Pets - Ca What To Expect When Your Dog Is Expectingmale nurseNo ratings yet

- Behavior Feline Ov RsDocument13 pagesBehavior Feline Ov RsjoanalucasNo ratings yet

- Wildlife NoteDocument14 pagesWildlife NoteDeep PatelNo ratings yet

- Canine Atopic DermatitisDocument16 pagesCanine Atopic Dermatitisserbanbogdans536667% (3)

- Merck Veterinary Manual Online Edition: ReferencesDocument3 pagesMerck Veterinary Manual Online Edition: Referenceslecol351100% (2)

- Chronic Otitis in Cats - Clinical Management of Primary, Predisposing and Perpetuating FactorsDocument14 pagesChronic Otitis in Cats - Clinical Management of Primary, Predisposing and Perpetuating FactorsThalita AraújoNo ratings yet

- 2011 Reproductive Cycles of The Domestic BitchDocument11 pages2011 Reproductive Cycles of The Domestic BitchMariaCamilaLeonPerezNo ratings yet

- Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease - 2018 Update: Zurich Open Repository and ArchiveDocument4 pagesFeline Lower Urinary Tract Disease - 2018 Update: Zurich Open Repository and ArchiveFran RetruzNo ratings yet

- Veterinary MedicineDocument2 pagesVeterinary MedicineAmir 1No ratings yet

- The Increasingly Complicated Story of EhrlichiaDocument13 pagesThe Increasingly Complicated Story of EhrlichiaMarisol AsakuraNo ratings yet

- Alopecia AreataDocument4 pagesAlopecia AreataMellisa Aslamia AslimNo ratings yet

- 01 Body Conformation of HorseDocument32 pages01 Body Conformation of HorseDrSagar Mahesh Sonwane100% (3)

- Hatching and Brooding Your Own Chicks - SustainabilityDocument4 pagesHatching and Brooding Your Own Chicks - SustainabilityzyhezomeNo ratings yet

- Saunders Solutions in Veterinary Practice, Small Animal Ophthalmology (VetBooks - Ir)Document382 pagesSaunders Solutions in Veterinary Practice, Small Animal Ophthalmology (VetBooks - Ir)Charlie PeckNo ratings yet

- How To Raise PigsDocument17 pagesHow To Raise PigsSherryNo ratings yet

- Hair Fall TreatmentDocument11 pagesHair Fall TreatmentpankajkhakareNo ratings yet

- FEDIAF Nutritional Guidelines For Complete and Complementary Pet Food For Cats and DogsDocument96 pagesFEDIAF Nutritional Guidelines For Complete and Complementary Pet Food For Cats and Dogsjlee_296737No ratings yet

- Medical, Genetic & Behavioral Risk Factors of Scottish TerriersFrom EverandMedical, Genetic & Behavioral Risk Factors of Scottish TerriersNo ratings yet

- Physiological Peculiarities of Horse, Common Vices, Senses, Behaviour of HorseDocument13 pagesPhysiological Peculiarities of Horse, Common Vices, Senses, Behaviour of HorseSantosh RajaNo ratings yet

- SaravanaDocument21 pagesSaravanaRasu Kutty100% (1)

- Cytologic Patterns - Eclinpath PDFDocument5 pagesCytologic Patterns - Eclinpath PDFJD46No ratings yet

- Feline Oral DiseasesDocument6 pagesFeline Oral DiseasesBogdan PopaNo ratings yet

- PDF Small Animal Medical Differential Diagnosis A Book of Lists Mark S Thompson Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Small Animal Medical Differential Diagnosis A Book of Lists Mark S Thompson Ebook Full Chapterelaine.dawson903100% (1)

- Hand Book of Veterinary Internal Medicine (VetBooks - Ir)Document88 pagesHand Book of Veterinary Internal Medicine (VetBooks - Ir)Shakil MahmodNo ratings yet

- Pyoderma in Dogs - VCA Animal HospitalDocument4 pagesPyoderma in Dogs - VCA Animal HospitalDulNo ratings yet

- Birds and Exotics - MCannon PDFDocument42 pagesBirds and Exotics - MCannon PDFAl OyNo ratings yet

- Flea Tick HeartwormDocument13 pagesFlea Tick Heartwormapi-324380555No ratings yet

- Degnala DiseaseDocument12 pagesDegnala DiseaseSantosh Bhandari100% (1)

- Canine and Feline Skin Cytology-1Document10 pagesCanine and Feline Skin Cytology-1Hernany BezerraNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 Equine DentistryDocument38 pagesLecture 5 Equine Dentistryannelle0219No ratings yet

- Ocular Issues and Endocrine Diseases in Small Animal Practice (Canine Eye Disease)Document11 pagesOcular Issues and Endocrine Diseases in Small Animal Practice (Canine Eye Disease)maddierogersNo ratings yet

- Dog Food Standards by The AAFCODocument3 pagesDog Food Standards by The AAFCOOmar ChadoNo ratings yet

- Current Diagnostic Techniques in Veterinary Surgery PDFDocument2 pagesCurrent Diagnostic Techniques in Veterinary Surgery PDFKirti JamwalNo ratings yet

- The Equine IntegumentDocument4 pagesThe Equine IntegumentSavannah Simone PetrachenkoNo ratings yet

- Horse HerniaDocument2 pagesHorse HerniaHadi Putra RihansyahNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy-: Buerger ExercisesDocument3 pagesPhysiotherapy-: Buerger ExercisesAkther HossainNo ratings yet

- CME Quiz 2020 August Issue 3Document3 pagesCME Quiz 2020 August Issue 3Basil al-hashaikehNo ratings yet

- Valvular Heart Disease: Mitral RegurgitationDocument33 pagesValvular Heart Disease: Mitral RegurgitationjihyooniNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan: Valiente, Ana Ambianca S. Maristela, Aony Jamaine Y. Tabora, Elyza M. Quitlong, Jennifer N. BSN 2BDocument6 pagesNursing Care Plan: Valiente, Ana Ambianca S. Maristela, Aony Jamaine Y. Tabora, Elyza M. Quitlong, Jennifer N. BSN 2BAmbianca ValienteNo ratings yet

- Fungal Infections Mycotic Infections MycosesDocument12 pagesFungal Infections Mycotic Infections MycosesHussein QasimNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Jigsaw ActivitiesDocument11 pagesDiabetes Jigsaw ActivitiesJacqueline CullieNo ratings yet

- 2.diseases of GroundnutDocument17 pages2.diseases of GroundnutAtharvaJadhav AMPU-20-2098No ratings yet

- AOS Injury Classification Systems Poster 20200327 THORACOLUMBARDocument1 pageAOS Injury Classification Systems Poster 20200327 THORACOLUMBARRakhmat RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- CausalityDocument47 pagesCausalityyeabsraNo ratings yet

- 10 1182@asheducation-2012 1 7Document6 pages10 1182@asheducation-2012 1 7nurdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Inflammatory DiseaseDocument18 pagesPelvic Inflammatory DiseaseVictorNo ratings yet

- CCA Final Exam Review 06 - 02Document4 pagesCCA Final Exam Review 06 - 02Stephen_haslundNo ratings yet

- Contract - Master Copy New Version MLHP TOR Revised 18-8-2020Document9 pagesContract - Master Copy New Version MLHP TOR Revised 18-8-2020SudhakshiNo ratings yet

- A Subdural HematomaDocument12 pagesA Subdural HematomaGina Irene IshakNo ratings yet

- Neck Masses and FistulasDocument55 pagesNeck Masses and FistulasWorku KifleNo ratings yet

- CNS Stimulants and Depressants PDFDocument5 pagesCNS Stimulants and Depressants PDFRizMarie100% (1)

- 21 Health Benefits of Bitter KolaDocument4 pages21 Health Benefits of Bitter Kolaserjio47No ratings yet

- NCP (Hip)Document13 pagesNCP (Hip)Ma.Je-Ann CatedralNo ratings yet

- Uk007 2223 006609Document3 pagesUk007 2223 006609Arpit KumarNo ratings yet

- NTP Annual Report 2021 v082221Document140 pagesNTP Annual Report 2021 v082221ChrisNo ratings yet

- GI Answer Key Part 1Document5 pagesGI Answer Key Part 1Nom NomNo ratings yet

- Ceftriaxone-Induced Fatal Anaphylaxis Shock at An Emergency Department: A Case ReportDocument3 pagesCeftriaxone-Induced Fatal Anaphylaxis Shock at An Emergency Department: A Case ReportHeLena NukaNo ratings yet

- Kaoshiki BenefitsDocument1 pageKaoshiki BenefitsABRACADABRA_1234No ratings yet

- PIT IKA XI Jakarta 2022 FlyerDocument2 pagesPIT IKA XI Jakarta 2022 FlyerAsviandri IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Chronic PyelonephritisDocument5 pagesChronic PyelonephritisIsak ShatikaNo ratings yet

- Program Hepato 24 03 2023Document20 pagesProgram Hepato 24 03 2023Loredana BoghezNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Pharmacokinetics of Intravenous Vancomycin For Pharmacists and Other Healthcare ProfessionalsDocument3 pagesTherapeutic Drug Monitoring and Pharmacokinetics of Intravenous Vancomycin For Pharmacists and Other Healthcare Professionalsminhmap90_635122804No ratings yet

- Affective Bipolar Disorder Episodes Kini ManiaDocument16 pagesAffective Bipolar Disorder Episodes Kini ManiaDeasy Arindi PutriNo ratings yet

- Dissociative DisordersDocument27 pagesDissociative DisordersShielamae PalalayNo ratings yet

- Keeling 2019Document8 pagesKeeling 2019senkonenNo ratings yet